4. Falling Out with Hal and Hester

God did say, You must not eat fruit from the tree that is in the middle of the garden, and you must not touch it, or you will die. You will not surely die, the serpent said to the woman. For God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil. When the woman saw that the fruit of the tree was good for food and pleasing to the eye, and also desirable for gaining wisdom, she took some and ate it. She also gave some to her husband, who was with her, and he ate it. Then the eyes of both of them were opened [...] And the Lord God said, ‘The man has now become like one of us, knowing good and evil. He must not be allowed to reach out his hand and take also from the tree of life and eat, and live forever. So the Lord God banished him from the Garden of Eden to work the ground from which he had been taken. After he drove the man out, he placed on the east side of the Garden of Eden cherubim and a flaming sword flashing back and forth to guard the way to the tree of life. (Genesis 3: 3-24)

All men by nature desire knowledge. (Aristotle, Metaphysics)

They Know Not What They Do

Culture has no need of time machines. The key narratives of any culture, with minor period-specific modifications, get repeated across boundaries of time as well as place and almost always have, at their basis, an awareness of the link between knowledge and power. The audacity of human intrusion into the fields of knowledge has always been seen as an act of taboo-breaking inviting extreme punishment. Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden were forbidden from eating the fruit of the Trees of Knowledge and of Life, the rationale being that, should they do so, they would become like God (omniscient and immortal). In Genesis they succeeded in eating only the fruit of the former, and thus destroyed not the universe-as-God-intended-it but merely humanity’s default entitlement to paradise. Knowledge was the forbidden fruit but, with hindsight, it may also have turned out to be the instrument of punishment for its theft. Historically, intrusions into fields of forbidden knowledge have had mixed results. By defying divine interdictions to look over their shoulders (look back), Orpheus condemned Eurydice to eternity in Hades and – Irit or Idit, in the rare Midrashic texts that give Lot’s wife a name (Büchnann and Spiegel, 1995) – condemned herself to a salty death. Psyche, in the original telling of the myth, though guiltier than either Eurydice (not guilty at all) or Idit, fared better in the long term, and was ultimately granted divine status by the placated Gods. With this rare exception, it remains nonetheless true that generally, as Alexander Pope would have it, a little learning is a dangerous thing, and, although this is not the corollary to Pope’s reasoning, one could argue that a lot of learning may be even more so. Since science harnessed the power of the atom, it has become conceivable that the planet, or even the entire universe, might be obliterated, a possibility raised also by recent experiments in the stratosphere of theoretical physics (as exemplified by the launching of the Hadron Collider, already mentioned, which, like Adam and Eve, will seek knowledge of the God-moment when nothing became something).

It takes a lot of knowledge, a very angry teacher (or a deity with a warped sense of humour) and a very reckless student to achieve the reverse trajectory back to nothing (possibly in the aftermath of a second and different, man-made Big Bang). It may be true that only God can make a tree (Kilmer, 1993), and that it takes at least one capricious Greek God to stock Pandora’s box, but since the middle of the twentieth century we have known that it takes only scientific curiosity and its misuse to kill all cats.

The claim to creation (demiurgic authorship), is usually deemed to be the province either of divine agency or of the aforementioned Big Bang, and, until very recently (6 August 1945, date of a smaller but sufficiently portentous Bang), so was the power of global extinction. Be that as it may, long before apocalypse of the man-made variety became a possibility (apocalypse now), awareness of the danger of knowledge in reckless hands haunted the minds and myths of all cultures and epochs.

Annihilatory power is not safe in any hands, not even God’s, as testified by the somewhat peevish Pentateuchal annihilations of the Flood, the Cities of the Plain, or, in the Book of Revelation, those implemented by the four horsemen of the Apocalypse. All resulted in random global death without rhyme or reason, and certainly without even a token attempt at issuing punishment selectively, only for just deserts.

On the other hand, as discussed in chapter 3, until the arrival of the nuclear age, destruction, whether of metaphysical or natural origin (God’s wrath, a colliding comet) always left the possibility of vestigial survival and continuity. Paradoxically, it was only when its enactment fell under the control not of God or nature but of human agency that it acquired cosmic possibilities. Robert Oppenheimer, gazing at the mushroom cloud which he had helped to create, understood this and acknowledged it not triumphantly but with post-lapsarian guilt, in the famous statement ‘I am become God, the destroyer of worlds’ (Oppenheimer, 1945).

My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!’

Nothing beside remains: round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare,

The lone and level sands stretch far away. (Shelley, 1818)

Oppenheimer’s guilt, unlike that of prior harbingers of apocalypse, however powerful their rhetoric, was without precedents, possibly because, unlike them, he and the other perpetrators of the Manhattan Project knew that for the first time in the history of the planet they really could put words into practice and reduce the planet to ‘lone and level sands.’ Either way, in any case, whether realistically or not, when we envisage annihilation (whether brought about by destructive deities, random forces of nature or destructive man-made machines), we create the horror narratives (and rules) we deserve, and we simultaneously polish the hand mirrors in which we can glimpse ourselves, in a glass darkly.

Stories of apocalypse ultimately narrate us. It could not be otherwise, since we make them up. It is perhaps not surprising, then, that not only does the basic plot, mythical, theological or sci-fi alike, always stays more or less the same, but, in the inimical other, in the violent alien, whatever its shape or form, if we look closely, we find ourselves. If we are very lucky we get expelled from Eden before the whole house of cards is irretrievably blown away. And the ultimate punch line may be the discovery that, whatever it was that made us, in the end, short of an unlucky mega-meteor, there is no deity, force of nature or machine that can break us, only we ourselves.

In Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (Bergman, 1957), Block, a medieval knight, on his way back home from the Crusades with his faith shaken rather than strengthened, contemplates the emblematic sacrifice of a child scapegoated for the advent of a plague: ‘Who watches over that child? Is it the angels, or God, or the Devil, or only the emptiness?’ Describing it as ‘the finest apocalyptic film we have,’ Robert Crossley (Crossley, 2000: 85) sees the killing of the child as instigating the necessity of atheism because a God whose act this was, would not deserve to be believed in. In the scene in question, the knight answers his own question when he says that in a world vacated by God, where – in a setting clearly allusive to a crucifixion – a child is burnt at the stake by priests, there is nothing left to contemplate other than humanity at its most wretched: ‘Look into her eyes. Her pain is our pain.’

In the end, in effect, a moral conclusion, and either the tenability or dismissal of faith itself, actually remain elusive: victory in the game of chess against Death would have purchased the knight the right to live but he loses; yet in sacrificing himself in order to save the lives of the family of actors he had encountered on his travels, the world loses its meaninglessness. In Bergman, personal apocalypse, represented by the Dance of Death, may, but only may, lead to a new epiphany, in an echo of the Biblical opening of the seventh seal, in Revelation.

In the Biblical original, the opening of the first four seals had released the four horsemen of the Apocalypse.

The opening of the seventh seal inaugurates end-time, following which comes rapture and salvation, albeit only for the chosen.

Figure 17. Ingmar Bergman, The Seventh Seal

Figure 18. Ingmar Bergman, The Seventh Seal

Elsewhere apocalypse, construable as an act of God, becomes at best an intellectual impossibility and at worst the vanishing point of the believing self, as epitomized by the plight of Arthur C. Clarke’s Jesuit astrophysicist who, in ‘The Star,’ loses his faith when he discovers that the creation of the star of Bethlehem required the destruction of an entire planet (and a worthy one, at that) by an exploding supernova:

Even if they had not been so disturbingly human as their sculpture shows, we could not have helped admiring them and grieving for their fate. They left thousands of visual records […]. We have examined many of these records, and brought to life for the first time in six thousand years the warmth and beauty of a civilization that in many ways must have been superior to our own. […] This tragedy was unique. It is one thing for a race to fail and die, as nations and cultures have done on Earth. But to be destroyed so completely in the full flower of its achievement, leaving no survivors – how could that be reconciled with the mercy of God? […] They were not an evil people […]. They could have taught us much: why were they destroyed? […] Now, from the astronomical evidence and the record in the rocks of that one surviving planet, I have been able to date […] very exactly [how long ago the explosion took place]. I know in what year the light of this colossal conflagration reached our Earth. [O]h God, there were so many stars you could have used. What was the need to give these people to the fire, that the symbol of their passing might shine above Bethlehem? (Clarke, 1955)

The supernova and the subsequent creation of the star, explained as an exercise on the part of God not in creation but in creativity (an aesthetic divertissement, a firework), required the annihilation of something advanced, beautiful and peaceful, resulting, furthermore, in the birth of a religion whose net effect, like that of any religion, has arguably been destructive. And if the balance was negative, therefore, the architect of this equation clearly does not emerge as a force for good within any parameters of human ethics or logic. No wonder the Jesuit lost his faith.

In many writings of apocalypse the destructive deities retain traits akin to their creatures. The Greek Gods were wilful, petty, jealous and self-regarding. Bergman’s God was a sociopath. And in Miguel Torga’s ‘Vicente’ (Torga, 1987), God, far from being omniscient, proves vulnerable to an intellectual ambush: faced with the choice of destroying either his most beautiful and complex creation (free will) or the eponymous raven that chose to exercise it by defying divine authority (he opts to flee the Ark and fly over a drowned Earth, even at the risk of finding nowhere to land and dying), the enraged deity grudgingly chooses to preserve free will. The waters recede, the bird is spared, and disobedience wins the day.

The Face of the Other

Whether the Divine takes on the guise of immanency or anthropomorphism or both, absolute annihilation, as argued in chapter 3, remains largely inconceivable to the human mind. Trying to imagine nothingness triggers that horror vacui which afflicted Greeks and Christians alike (Rotman, 1993). Zero, nothing, the void, as discussed earlier, is never really an option, or not, at least, in any formulation that attributes to an anthropomorphic God any affinity with his creatures. It is perhaps for this reason that in the vocabulary of apocalyptic narratives informed by notions of deities variously shaped by humanity in its own image, it is often necessary to re-shape the perpetrator of annihilation as an alien but also a non-anthropomorphic force. Hence, therefore, the abundance of plots which pit humanity, in all its identifiable merits and frailties, against an other defined, whether through its bestial or robotic (but either way in all respects nonhuman) nature as absolutely different. The fact that the narrative plots tend to be themselves all too familiar, compounds rather than diminishes the dimension of de-familiarization but also, equally importantly, the permissibility of defensive altericide of reassuringly unrecognizable enemies. It is easier both to kill and be killed by something that does not look too much like us.

The Problem with Being God

While in works such as John Wyndham’s The Chrysalids (Wyndham, [1955] 1984) and The Midwich Cuckoos (Wyndham, [1957] 1984) or Theodor Sturgeon’s More Than Human (Sturgeon, 2000) humanity is forced to face the possibility of being overpowered by nonhumans, not-quite-humans, superhumans or composite humans (homo gestalt), in narratives otherwise as diverse as Quatermass and the Pit (Kneale, 1958-59), the film trilogy of The Matrix and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (Adams, 1979) it faces the alternative possibility that it is itself the creation of a non-divine puppet master. The hypothesis comes in all forms, from horror to farce. Running through all of them, however, it is possible to detect three fundamental fears: first, that what we take to be reality (the world as we know it) is not real; second, that whatever reality is, we do not control it; and third, that reality as we understand it might turn out to be unstable and disappear.

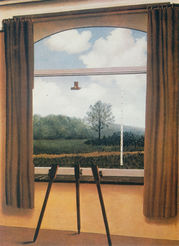

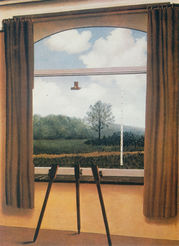

Figure 19. René Magritte, The Human Condition

In Magritte’s pseudo-tromp l’oeil, for our purposes, helpfully named The Human Condition, a picture on an easel depicting a view out of a window is on closer inspection revealed to be not a picture but the view itself, realistic in all aspects except for the easily missed edge of the glass/window on which the image (whose edge however exactly matches the reality outside the window) is painted. Which is real? Both or neither?

In The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and its sequels, the Earth turns out to be not a planet but a computer named ‘Deep thought,’ designed by a race of hyper-intelligent, pan-dimensional beings, sometimes disguised as mice, who built it to calculate the answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe and Everything. Adams’s lampoon echoes Wyndham’s more chilling observation in The Midwich Cuckoos:

When I look around the world, it does sometimes seem to hold a suggestion of a rather disorderly testing ground. The sort of place where one might let loose a new strain now and then, and see how it will make out in our rough and tumble. Fascinating for an inventor to watch his creations acquitting themselves […]. To discover whether this time he has produced a successful tearer-to-pieces, or just another torn-to-pieces and, too, to observe the progress of the earlier models, and see which of them have proved really competent at making life a form of hell for others. (Wyndham, 1984: 204-05)

Or, as Satan would have it in Andy Hamilton’s hilarious radio comedy, Old Harry’s Game, God ‘was as surprised as anyone when humans became the dominant species. He had his money on badgers.’ (Hamilton, 2007). In Hitchhiker’s Guide, when the answer to the meaning of life, the universe and everything (42) proves to be unhelpful, Deep Thought predicts that another computer, more powerful than itself will be designed and built to discover what the question was that elicited that answer. The second computer/ planet (Earth) is duly built as part of a 10-million-year programme run by mice (the second most intelligent species on the planet after dolphins), but is inadvertently destroyed (five minutes before delivering its conclusion) by the Vogons, another extra-terrestrial species, who were clearing space to make way for a hyperspatial by-pass. As summed up by Slartibartfast, the Magrathean designer of the planets, ‘the mice were furious’ (Adams, 1979, 123).

The demolition of the Earth, an event in itself not of negligible significance (despite the planet’s somewhat dismissive classification in intergalactic reference works as ‘mostly harmless’) (Adams, 1979, 52), is dwarfed by what is uncovered in a subsequent novel, The Restaurant at the End of the Universe (Adams, 1979). In this it is revealed that the Universe is in the safe hands of a simple man who lives with his cat in a wooden shack on a remote planet. Much might be made of the fact that in Adams’s gloriously insane lampoon, mice (in our world the usual subjects of scientific experimentation), are instead the ones running the laboratory, in a universe which however, and worryingly, is itself overseen by a cat. Be that as it may, in the last volume of the series, So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish, comic iconoclasm acquires a darker edge which it is no longer easy to ignore: God’s final computer-delivered message to his creation, ‘We apologize for the inconvenience,’ (Adams, 1984: 201-02) evokes Aristotle’s (1985), Bakhtin’s (1982) and Umberto Eco’s (1992) warnings about the dangers of supposing one has the last laugh. Bakhtin saw laughter (‘carnival’) as the temporary suspension of authority. For Aristotle, in the ‘The Art of Poetry,’ comedy, and the choice of engaging with it, was something deemed appropriate for the baser kinds of men, tragedy being reserved for the nobler. And elaborating on these principles, in The Name of the Rose the Venerable Jorge, Umberto Eco’s murderous monk, sees laughter as dangerous, because it demeans men and denies God: ‘with his laughter the fool says in his heart, “Deus non est”‘ (Eco, 1984: 132). If so, it stands to reason that Adams-style laughter, and the more riotous the better, may after all be the most appropriate mode of depicting the ultimate upheaval, the end of a world that deserves no better, in a universe where God is not.

Philip K. Dick’s Dr. Bloodmoney and Peter Weir’s film of 1998, The Truman Show are less funny than The Hitchhiker’s Guide. Ever less funny, indeed, with hindsight, following the advent of Reality TV which these works pre-empt by some years and exaggerate, but not a lot. In The Truman Show, as in Dick’s novel, a single individual’s reality is ultimately revealed to be not only unreal (un-True(man)) but fraudulent. Set in the fictional seaside village of Seahaven, the purpose-built, purpose-populated town is dedicated to a 24-hour television reality show. All of the participants are actors except for the eponymous hero, Truman Burbank, who is unaware that he lives in a simulated reality, as the protagonist of a round-the-clock, mass-media television soap. Truman was chosen out of five unwanted babies to be a TV star in the reality television programme, ‘The Truman Show’, and is therefore in effect the creation and creature of the show’s producer. This modern-day demiurge, appropriately or inappropriately named Christof (of Christ?) inhabits a panoptic eerie overlooking the town, its inhabitants and its existence. From this privileged position he is omnipresent, all-seeing (in the form of thousands of recording television cameras) and omnipotent. Despite a few near-misses, the fiction is maintained until Truman, aged thirty, gains an understanding of the situation, tries and eventually succeeds in escaping from Seahaven. As he finally reaches the edge of the constructed reality and exits via a door in the wall of a trompe-l’oeil sky at the edge of the horizon, his demise as fictional character and entry into a reality which however, for him, has never, and at that point still does not exist, is both cheered and lamented by a world-wide audience of millions, for whom that particular world has now disappeared. Truman becomes a true man, rather than a character in someone else’s narrative, but at that point he also ceases to exist as the man he thought he was. That particular world has met its Armageddon. No wonder audiences world-wide feel bereft. The wider implications of The Truman Show do not necessarily refer back directly to notions of apocalypse, but there are connections, not least, as far as Truman is concerned, in what regards the end of one world and the revelation of another.

In 1999, one year after The Truman Show was released, the first series of Big Brother began broadcasting, and four years later the internet virtual world, Second Life, was developed. Leaving aside the question of participant consent (not given by Truman but enlisted in the other two cases), a similar suspension of disbelief elides the boundaries between reality and a variety of simulacra of it.

Who’s the Fool Now?

In the apocalyptic works discussed in the course of previous chapters, ultimately, even when humanity as a species prevails, its survival may be preserved at the cost of being forced to ac(knowledge) absolute lack of autonomy in a reality which until then it never knew it didn’t in fact know. This realization involves the recognition of humanity’s delusion of ontological centrality, now replaced by a new consciousness of the species’ unimportance within a universe it neither controls nor defines. The sun, undeniably, does not revolve around the Earth, and there may be no God whose finest creation we are. The real tragic hero in The Truman Show, in the end, may be not Truman himself, but Christof, who like God, when his particular universe ceases to exist, is forced to accept that in seeking to control an other, one may lose oneself. In the quest for control one may come close to being God, but this, in the end, as we know, has been the trap lying in wait for humanity as the ultimate punishment for its usurpation of knowledge. The awareness of that ambush is evidenced in all our narratives from that of first couple in the Garden of Eden through numerous cultural and fictional histories down the ages.

In Genesis, God created Eden but his tenants of choice failed the test that would grant them a permanent residence permit, arguably making its existence pointless. In The Truman Show, Christof creates a safe and stable world but his protagonist’s disobedience, like Adam’s and Eve’s, brings that particular reality, too, to a close. The same problem finds different renditions in multiple fictions of apocalypse brought about through the agency of creators whose demiurgic status does not in the end spare them from a retribution invited by hubris.

Lying in the Bed We Made

Kurt Vonnegut’s irresponsible scientist in Cat’s Cradle (Vonnegut, 1981) and Margaret Atwood’s vengeful one in Oryx and Crake (Atwood, 2003), inventors respectively of a substance capable of freezing life on Earth and a bacterium capable of eliminating it entirely, do not survive the cataclysms they unleash.

‘The seed, which had come from God-only-knows-where, taught the atoms the novel way in which to stack and lock, to crystallize, to freeze. […] And suppose […] that there were one form [of ice], which we will call ice-nine […]. If [someone] threw that seed into the nearest puddle…?’

‘The puddle would freeze?’ […] ‘and all the puddles in the frozen muck […] and the pools and the streams in the frozen muck […] and the rivers and the lakes the streams fed […] and the oceans the frozen rivers fed […] and the rain?’

‘When it fell it would freeze too […] and that would be the end of the world!’ (Vonnegut, 1981: 33-36)

In Cat’s Cradle the end of the world does happen, but by its very nature it leaves enough basic reserves preserved (in ice) to ensure the subsistence of a small group of survivors. The continuity of humanity remains if not a probability at least a possibility, as is the case also at the conclusion of Atwood’s Oryx and Crake and its sister novel, The Year of the Flood.

It’s a Jungle out There

In John Wyndham’s Trouble with Lichen, the heroine, Diana Brackley is described in her youth by her teachers and peers as being ‘with us but not of us’ (Wyndham, [1960] 1982: 31). Although less radically than in some of his other novels, here, too, Wyndham articulates the problem of alterity. Unlike some of his other protagonists, albeit exceptional in many ways, Diana is just a scientist, not a mutant or an alien from outer space. Having said this, however, she does bring about potentially apocalyptic (in both senses of the word) changes to the world. Being entirely sui generis, she deviates not only from the norm (the common run of humanity) but also from fellow mavericks within the pathways of unsanctioned, rogue scientific research, since, unlike her counterparts in Vonnegut and Atwood, she is a scientist whose ultimate achievement involves not universal death but vastly increased life expectancy. She threatens the viability of humanity when she discovers an antigerone, a substance capable of massively slowing down ageing and prolonging human longevity, with all the long-term social and political implications this entails. A radically extended lifespan threatens social stability, and for good or bad, therefore, her discovery could conceivably change the world (that, of course, being one definition of apocalypse), signalling, in effect, the birth of a new human variant (homo superior, Wyndham, 1982: 86): human beings with life expectancies of at least 300 years, but possibly more; or, as she describes it, ‘the only evolutionary advance by man in a million years,’ (Wyndham, 1982: 85).

The social, demographic and political implications of a product of limited availability but, even so, liable to ‘change the whole of future history completely’ (Wyndham, 1982: 85-86) opens up new possibilities but also vast problems. The latter are different yet akin to the quandaries of a humanity confronted with more advanced human forms (The Midwich Cuckoos, The Chrysalids), in the struggle for resources, space and, in the final instance, supremacy. And in all these narratives, when faced with the imperative of exterminating or being exterminated by competing beings, whether or not these are true species-likenesses of itself, humanity will eventually be obliged to confront the ethical implications of any struggle for survival: namely the recognition that, in extreme circumstances, human beings readily break away from the codes of civilization and regress into the ancestral jungle, even if it involves the extermination of more vulnerable members (or thereabouts) of their own species. This is explained with un-nuanced bluntness in The Midwich Cuckoos:

We are presented with a moral dilemma of some niceness. On the one hand it is our duty to our race and culture to liquidate the Children, for it is clear that if we do not we shall, at best, be completely dominated by them, and their culture […] will extinguish ours.

On the other hand, it is our culture that gives us scruples about the ruthless liquidation of unarmed minorities. […]

You are judging by social rules and finding crime. I am considering an elemental struggle, and finding no crime – just grim, primeval danger. (Wyndham, Midwich, [1957] 1984: 208-12)

Mean Machines

Ethics, of course, are in principle not involved when dealing either with the inanimate or, in many cases, even the nonhuman animate: when we take antibiotics, we do not worry too much about the right to life of bacteria, and when we run clinical trials on them we do not concern ourselves inordinately with those of laboratory rats or even higher primates. The enemy, however, in any case, need be neither alien nor terrestrial, neither an animate version of an other (another animal species) nor a mutated variation of the self (the composite beings described in The Midwich Cuckoos and The Chrysalids), but simply a product of human scientific achievement. The fear of a global insurrection against us by machines of our making echoes that presumably felt by God when confronting the possibility of a snake-instigated putsch in the Garden of Eden.

In James Cameron’s film of 1984, The Terminator, we are treated to a futuristic rendition of two of the West’s foundation narratives, the Christian Nativity and Christ’s Passion, still recognizable despite futuristic modifications. A cyborg travels from the future to the diegetic present to kill Sarah Connor, a woman who, at an unspecified but prophesied date, will give birth to a child at that point still to be conceived. The child, John Connor (a good Irish-American Catholic name, which, furthermore, shares its initials with Jesus Christ), will live to be the saviour of humanity against the cyborgs, humanoid computerized machines that in the near-future are due to take over the planet. Hot in pursuit of the cyborg is Kyle Reese (a name homographically close to the liturgical plea Kyrie Eleison, Lord have mercy), an envoy of those future humans and a friend of John Connor, dispatched from the future to prevent Sarah’s murder, and to ensure that the would-be mother (yet another version of the Virgin as the Woman of the Apocalypse) survives and brings forth the necessary saviour. He does more than that, and in fact impregnates her with the foretold child. The film develops into a straightforward plot of quest and struggle, pitting brains against brute force, orderly civilization against the unbridled techno-elemental, good against evil. In the course of it, the search for the woman to be slaughtered becomes merely a pretext for the real business of males — human and otherwise — killing each other in the name of prioritizing their respective lineages. Good achieves an open-ended victory (the cyborg is defeated, albeit, in true gospel fashion, only at the price of a sacrificial male death). The victory, moreover, is not definitive: there are plenty more cyborgs where the first one came from, and to date three open-ended film sequels, two of them with biblically allusive titles: Terminator 2: Judgement Day, 1991, Terminator 3: The Rise of the Machines, 2003 and Terminator 4: Salvation, 2009). In the first film, The Terminator, Reese, whose persona — beyond the figure of knight in shining armour in aid of damsels in distress — had adumbrated the triple role of God (father of a saviour), guardian angel (of unborn children) and St. Joseph (his son will bear his mother’s rather than his father’s surname, rendering paternity a by-proxy affair), dies, leaving us with one surviving heroine and the promise of a living hero in the future. There is of course an important difference between these two. A bird in the hand is clearly better than two in the air, and the survival chances of the two sexes at the end of the first installment look unequal: on the one hand a resilient heroine who at the very last discards reliance upon ineffectual defenders and takes it upon herself to finish the job of destroying the cyborg. And on the other hand, a dead hero and a promising but yet unborn son.

This scenario encapsulates much that is relevant to the central themes of foundation narratives such as the Biblical ones of the Nativity and the Passion but also of the Apocalypse. In The Terminator, in a modification of the gospel texts, a son sends his future father to the death rather than vice-versa, but with an analogous intent, namely to save himself/his interests. In both cases males engage in mutual destruction (man against cyborg in an echo of religious interests at logger heads with one another: good against evil, God/Son of God against Satan). The basic structure echoes the logic of narratives of apocalypse: salvation and perdition, creation and destruction, continuity and finiteness (termination). Moreover, it renders some of the implications of the above plot akin to the central issues raised in this discussion of textual and film narratives, structured, as they are, in equal measure, by intertextual allusion to prior traditions and by terror.

In both Roland Emmerich’s Independence Day (Emmerich, 1996) and in Steven Spielberg’s War of the Worlds (Spielberg, 2005, from H.G. Wells’s novel of the same title), and echoing the binary underpinning the basic premise of The Terminator, the demarcation of the dividing line between good and evil, right and wrong is also that which separates humans from machines. In one of the most ludicrous moments in Independence Day, the invading aliens establish voice contact. Although like the cyborg in The Terminator, these particular aliens speak English (of course), unlike in War of the Worlds, where the invading tripods are destroyed by a biological adversary (bacteria, something which suggests they are of an organic rather than inanimate nature), the invading enemies in Independence Day, War of the Worlds and The Terminator are uncompromisingly automated machines with whom any notion of dialogue or understanding is not possible. And in Michael Crichton’s Prey (Crichton, 2002), too, the enemies, although having the ability to evolve, reproduce, learn and mimetically morph living beings to produce the illusion of animate life, are in fact inorganic nanoparticles: micro-robots programmed to kill, just like the cyborgs in The Terminator, only writ extremely small.

Unlike Miguel Torga’s God, who weighs up the value of unimpugned omnipotence against the destruction of his finest work and finds net gain in preserving the latter in exchange for relinquishing absolute authority (Torga, 1987), in the texts mentioned above, the ultimate rescue of humanity entails the destruction of the alien machine, including, often, those which it had itself created (in The Terminator, Cameron, 1984; Prey, Crichton, 2002; I, Robot, Proyas, 2004) but which now threaten to overrun it. In a conflict between the two, human creator and mechanical creature quasi-Oedipally intent on eclipsing its progenitor, one must exterminate the other. This is explained by the General Manager of the gigantic corporation Rossums Universal Robots (R.U.R.) in Karel Čapek’s play of the same title (Čapek, 2010), in which a replay of the Biblical narrative of fall and expulsion (but which here sees the creator vanquished by his creatures), brings about the end of human history (the end of civilization) at the hands of robots, themselves the products of two defining aspects of that self-same civilization: advanced technology and capitalist market forces.

An understanding of the danger of power entrusted to machines, indeed, does not require the phenomenon of futuristic robotic would-be dictatorships. The error factor whereby a faulty automated computer system triggers or threatens to trigger human extinction by nuclear war or other means is the standard fare of sci-fi global-disaster movies and narratives: WarGames (Badham, 1983), Fail-Safe (Lumet, 1964; Frears, 2000), By Dawn’s Early Light (Scholder, 1980), Level 7 (Roshwald, 2004) and Limbo (Wolfe, 1952), already discussed.

My Self, My Other

In John Wyndham’s short story, ‘Compassion Circuit’ (Wyndham, [1956] 1983), sophisticated anthropomorphic robots perform the functions previously (depending on historical time and place) performed by slaves/servants/subalterns. The robots include in-built state-of-the-art compassion circuits which enable them to fulfil and sometimes even, if deemed best, to override their masters’ and mistresses’ instructions (for their own good). In a status quo symbolized by an absent husband and a sickly wife who cannot sustain herself either physically or emotionally, the latter becomes dependent for all her needs on Hester, a humanoid robot (made to order, with detailed specifications: ‘darkish blonde […], five foot ten, and nice to look at, but not too beautiful, Wyndham, 1983: 202). The climax to an increasingly creepy tale sees both husband and wife ultimately deprived, as per Hester’s instructions, of their flawed human bodies and equipped instead, with robotic prosthetic ones. Although there is no suggestion that their human consciousness was removed, its retention, faced with a new world in which robots are able to make what are literally life-altering decisions without human consent, makes consciousness, retained without the power of agency, arguably more cruel even than actual obliteration.

If their bodies have been replaced but self-awareness preserved, this makes the plight of the husband and wife only marginally less cruel than that of that of the quiescent gynoid (female android) spouses in Ira Levin’s The Stepford Wives (Levin, 1996); or that of the husband reduced to one single eye floating in a basin, in Roahl Dahl’s ‘William and Mary,’ in which disembodied awareness is maintained by the gadgetry of advanced medicine. Wyndham’s and Dahl’s stories both give grim warning of the danger that scientific achievement, that which has made the human species almost omnipotent, paradoxically might prove to be what ultimately leads to its annihilation. Too clever by half? Possibly. The moral from this brand of science fiction horror narrative is that, other than a global cataclysm or an Act of God, the most likely destroyer of humanity is humanity itself, or the products of its ingenuity.

In Stanley Kubrick’s defining film, 2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrick, 1968), the possibility of a takeover by machines, in this case computers, ups the ante. Astronauts on a pioneering space mission find their endeavour and indeed their lives threatened by the space ship’s computer, HAL or Hal (Heuristically Programmed Algorithmic Computer), which has different views regarding the shape of things to come. Hal’s attempted coup unfolds within the confined limits of the space ship and the enemies he has identified are the small crew, but the stakes, nonetheless, are massive, and the prize, ultimately is of cosmic proportions: namely mastership of the Universe. Hal’s gentle tones as he/it outlines the plan whereby, sooner rather than later, human beings will be overthrown by the machines they made somewhat in their own image, as in several of the iconic texts and films of recent and classical sci-fi (The Terminator, Cameron, 1984; I, Robot, Proyas, 2004; A.I. Artificial Intelligence, Spielberg, 2001; This Perfect Day, Levin, 1994; ‘The Machine Stops’, Forster, [1909] 2004; Prey, Crichton, 2002), arguably represent, at one level, the enactment of panic inbuilt into our awareness that in the end humanity can only ever partly control the environment; including, or particularly, the flawed environment it is itself capable of creating through science, technology and hubristic gate-crashing into the domains of Knowledge. No one forced Adam and Eve into the action that lost them Eden.

At the end, in 2001: A Space Odyssey, as his attempted insurrection against his human creators is crushed and he is disconnected, Hal’s mellifluous-cum-sinister tones are transformed into the pleading of a frightened child and then a babbling baby. From Chronos to Abraham, from the Phoenicians to Freud, from antiquity to modernity, the murder of offspring, perpetrated either to preserve power or curry favour with those that have it, has proved an enduring motif. Sometimes the attempt is thwarted, as shown in the case of Herod, whose failure to kill a King of the Jews prophesied to be greater than himself, changed the world. The fact that in that instance the real, divine father, took up where Herod left off (making Herod, like Judas, justified in complaining that he was ‘used like a key,’ Hirst, 2004: 19), and sacrificed his own son to a higher purpose, is another debate. Be that as it may, while in The Terminator humanity succeeds at least temporarily in curbing the destructive intent of its mechanical offspring, that outcome cannot be guaranteed in perpetuity, and the sobbing infantilized voice of Hal at the end of 2001 (Kubrick, 1968) could at any point be replaced by the violence of high-tech Oedipal offspring triumphant in overcoming the originating parent in order to gain possession of Mother Earth.

Humanity’s attempts to claim demiurgic control over the world have included the creation of a variety of subalternities: from entirely nonhuman products in the shape of computers, androids and other machines (Blade Runner, Scott, 1982; the other narratives and films discussed previously), to humans subjected to more or less benevolent human-controlled technodictatorships (Brave New World, Huxley, 1977; This Perfect Day, Levin, 1994; Fahrenheit 451, Bradbury, 1976; The Penultimate Truth, Dick, 2005; ‘The Machine Stops’, Forster, [1909] 2004), or anthropomorphic, quasi-human, man-made renditions (Dr. Jekyll’s monstrous alter ego, Mr. Hyde, Stevenson, [1886] 2007; Frankenstein’s monster, Shelley, [1818] 1983; Walter C. Miller’s neutroids in the remarkable short story ‘Conditionally Human,’ Miller, 2007).

In the latter, first published in 1952, eight years before Wyndham’s Trouble with Lichen, whose basic premise it anticipates, and in a prophetic rendition of contemporary concerns, medical and scientific advances have resulted in dangerously prolonged longevity, with implications regarding available resources. In Miller’s story the solution involves selecting a minority of the population for authorized reproduction. The remainder may not have children, but frustrated parenting desires are partly catered for by the ownership of genetically modified animals: semi-intelligent talking pets such as cats, dogs, or semi-human ‘models’ (chimpanzees or neutroids: child-lookalikes but with tails), all with restricted food requirements and a very limited life-span. Terry Norris, the central character, is an inspector for the F.B.A. (Federal Bio-Authority) which controls numbers of pets and neutroids and disposes of unwanted or defective (mutant) ones. The plot unfolds around the deliberate creation by a rogue geneticist of a mutant species of neutroid which is capable of living till adulthood and reproducing, and the refusal by Anne, Norris’s wife, to accept the elimination of one of these, Peony, to whom she has become maternally attached. In a re-working of the notion that love makes the world go round (and sometimes turns it upside down), Anne’s love for Peony and Norris’s for Anne results in his decision to apply for a job in Anthropos Incorporated, the state department that creates neutroids, with the intention of large-scale subversion: namely, the mass creation of illegal, fertile neutroids, potentially capable of doing ‘better than their makers’ (Miller, 264) and, eventually, of creating a better world.

If, in constructing more or less animate alternative forms, humans as a species introduce the possibility of their own downfall, paradoxically, in destroying them in order to preserve humankind’s survival, to some extent they lose their own humanity. This is particularly so where, as will be discussed in the case of Blade Runner, ‘Conditionally Human’ (Miller, 2007), A.I. Artificial Intelligence and I, Robot, the line between automated machine and creature capable of some emotion becomes blurred. In such cases it becomes clear that, in destroying the beings we produced, we destroy ourselves in our thinking, ethical humanity (a dilemma not unlike that confronted by an endangered human species in Wyndham’s The Midwich Cuckoos, or The Chrysalids already discussed). Furthermore, as well as representing a potential danger either to the survival of their human inventors or to the latter’s definitions of self, the machines/ creatures in question, as suggested above, also introduce the possibility that the danger they represent was knowingly incurred by their creators, punishment being therefore deserved by a species guilty of hubris: namely the attempted usurpation of God’s/nature’s monopoly over demiurgy.

Sufficiently ‘Other’

Another option, less alienating because it points the finger of blame at targets outside the sphere of human ingenuity, is that of locating the inimical alien in something that is neither human nor human-made, but instead, and reassuringly, both familiar and different: namely unexpected animal forms. From big apes such as King Kong to the beasts of Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park (Crichton, 1998) and Congo (Crichton, 1995) to the smaller creepy crawlies dealt with in previous chapters, and from these to the microscopically small in the Andromeda Strain (Crichton, 1995), the animate as opposed to inanimate or robotic other provides a half-way house within which to confront the concept of otherness (although in Jurassic Park and ‘Conditionally Human,’ admittedly, the variations, albeit animal in nature, are made possible by human genetic engineering).

Insufficiently ‘Other’

In the end, however, whether considering giant apes, living simulacra, small microbes or extremely small nano-beings, none ultimately instil the degree of fear achieved by enemies whose ability to mirror our selves might conceivably enable them to snatch both our bodies and our souls. But if, as suggested above, we succeed in destroying them, in doing so, arguably, we also, at least in part, destroy ourselves. In Clifford D. Simak’s Ring Around the Sun (Simak, 1990), a breed of extra-terrestrial beings distinguishable from Earthlings only in their superior mental skills and advanced technology, plan to take over the planet and transfer its entire population to another world located in a parallel universe, there to replay human history in a way that will avoid the errors which in the past led to illness, war and other earthly disasters. Although in some respects well intentioned, Simak’s superior beings illustrate, nonetheless, the ambivalence that surrounds the phenomenon of evolutionary, technological and scientific advances (as represented by superior species, robots, nuclear energy) capable, like John Wyndham’s helpful Hester or Kubrick’s silver-tongued Hal, of improving human life but also extinguishing it. Switching off a machine, however anthropomorphic (cases such as the androids in A.I. Artificial Intelligence or Blade Runner excepted), is usually not a problem whereas, as shown in Miller’s ‘Conditionally Human,’ in the end, outside a willingness to practice would-be genocide, it is often not possible to exterminate a life form that closely resembles our own. The problem becomes evident where, in some the films and novels discussed, it is impossible to assert unequivocally the non-humanity of the other. This is because, as already suggested, where there is such uncertainty, a willingness to destroy those ambiguous others regardless, brings into question the very humanity of the self.

The replicants/mutants in The Chrysalids, A.I., ‘Conditionally Human,’ Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (Dick, 2007) and the latter’s film version, Blade Runner (Scott, 1982) all have aspects of categorical ambiguity. In the case of the latter two, for example, both in the novel and its film adaptation, a measure of uncertainty prevails regarding who/what is or is not an android, a problem which introduces also uncertainty about definitions of the self. In the film, for example, Rachel is an android whose mechanical circuits include implanted memories from a real woman, and not only is she surprised when she learns that she is in fact an android but, like David in A.I., experiences emotional turmoil at the revelation.

Carlos Clarens (Clarens, 1997) argues that in science fiction featuring anthropomorphic aliens of various kinds, what is played out is not the fear of an other who is utterly different but rather of one who is instead uncomfortably familiar, or, in other words, not different enough to be readily identified as alien and thus destroyed without guilt. This is the phenomenon underlying fantasies in which the other may be either benevolent and peaceful (The Chrysalids, The Day the Earth Stood Still, Wise, 1951) or downright aggressive (Wyndham’s The Midwich Cuckoos; Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Siegel, 1956; Guillermin, 1976), but either way, as much by virtue of its difference as its similarity, it represents a species-threat to humanity. In the end, as Wyndham’s eccentric fous savants well understand (the unnervingly perceptive Zellaby in The Midwich Cuckoos, the urchin-like Dr. Bocker in The Kraken Wakes, Wyndham, [1953] 1980), two species with equal needs cannot coexist in the same space on limited resources.

Oddly, or perhaps not so oddly, given both the strangeness (because as yet they do not exist) and the unexpected familiarity of anthropomorphic robots in human shape, it is the android or humanoid, rather than the faceless machine, that elicits greatest fear. In Philip K. Dick’s We Can Build You (Dick, 1977) and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (Dick, 2007), in Ridley Scott’s film of the latter novel, Blade Runner (Scott, 1982), in Karel Čapek’s War with the Newts (Čapek, 2001) and R.U.R. (Čapek, 2010), and in blockbusters such as A.I. and I, Robot, the machines in question have an uncanny dimension of humanity which blurs the line that separates sentient (and supposedly moral) human beings from insensible automatons, and therefore questions the ethics of the latter’s destruction (making it tantamount to genocide).

The realization that the alien other, although capable of widespread destruction, might also have an advanced sense of responsibility and a capacity for what are assumed by humanity to be exclusively human emotions, is explored with some success and sometimes considerable pathos in Close Encounters of the Third Kind (Spielberg, 1977), E.T. (Spielberg, 1982), A.I. Artificial Intelligence, I, Robot and I Married a Monster from Outer Space (Fowler Jr., 1958). In the latter, aliens from the Andromeda constellation arrive on Earth as one of the stops in their tour of the universe. The reason for their journey is a quest for females with whom they can mate in order to perpetuate their species, now threatened with extinction as the result of an episode of solar instability which caused all their own females to die. Albeit clearly inhuman in the common usage of the word, through prolonged contact with humans and in an echo of similar phenomena in I, Robot and A.I. (Spielberg, 2001), the aliens begin to develop anthropomorphic emotions. In I Married a Monster from Outer Space (Fowler, 1958), Bill falls in love with his Earth wife Marge; in A.I. Artificial Intelligence (Spielberg, 2001), David, a humanoid robot, competes with a real boy, Martin, for the love of Martin’s parents; in I, Robot Sonny transcends the laws of robotic mechanics and becomes capable of hatred and murder. And as they all, in different ways, begin to engage the viewers’ sympathy or at least empathy, the human protagonists, paradoxically, gradually lose their humanity: once she knows he is an alien, Marge feels no pity for Bill’s genuine love for her; following the return of their real son, Martin’s parents discard David without any guilt; the astronauts in 2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrik, 1968) have no qualms about disconnecting Hal.

I, Robot, based on a group of stories by Isaac Asimov, is set in Chicago in the year 2035, a time in which humanoid robots are in widespread usage. They are governed by the Three Laws of Robotics:

1.A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

2.A robot must obey orders given to it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the First Law (echoes here of Wyndham’s ‘Compassion Circuit’).

3.A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

The central protagonist, homicide detective Del Spooner, is distrustful of robots. His distrust stems from an event in his past (a car accident in which the car computer countered Spooner’s instructions as the driver to save a little girl and saved him instead, based on a calculation of the statistical chances of survival of each). At the beginning of the film Spooner receives a call announcing the death of an acquaintance, Dr. Alfred Lanning, inventor of the Three Laws of Robotics and co-founder of USR, a company that specializes in robotic technology. Lanning had fallen from his office window to his death in what appeared to be suicide. Spooner, however, is sceptical and decides to investigate. In the course of his inquiries, he comes to believe that an NS-5 robot was responsible for Lanning’s death. Dr. Susan Calvin, a robot psychologist who works at USR points out this would be impossible, because robots are bound by the three laws, which forbid a robot from harming a human. While searching Lanning’s room, however, Spooner is attacked by an NS-5 robot named Sonny. Sonny subsequently explains he was built by Lanning himself and denies murdering him, while displaying emotions such as anger and fear, qualities not normally found in robots. Sonny also claims to experience dreams. Throughout an intricate plot development, Spooner succeeds in accessing a hologram Lanning created before he died, in which he explains that the Three Laws governing robotic operations have loopholes that can lead to robotic revolution. Back in the city, Spooner discovers the robots have mobilized and are revolting against humans as the result of an interpretation of the Three Laws, which supports the robots becoming a benevolent dictatorship with a mission to save humanity from its own worst excesses. The rationale (the robotic version of ‘being cruel to be kind’ also followed by Hester in ‘Compassion Circuit,’ and in some ways analogous to the logic of ‘the greatest good for the greatest number’ premise in The Day the Earth Stood Still, Wise, 1951, to be discussed), involves robots taking over the world in order to prevent humans from self-destructive behaviour (for example crime or environmental damage). A global robot takeover would thus ensure humanity’s survival (as per the First Law of Robotics), albeit no longer in a position of dominance. The robot take-over is suppressed but Spooner clears Sonny of all charges against him – noting that murder is defined as the act of one human being killing another. He accepts Sonny as a friend, and lets him go, telling him that the meaning of freedom includes the responsibility for deciding his future for himself. As the final credits roll, Sonny looks on as thousands of NS-5s are placed into storage in a scene reminiscent of a dream he’d once had. It is not impossible, of course, that in an unspecified future, they might break loose again.

Human Emotions

In the end, judgments regarding an unclear ontological demarcation between humans and machines, as already indicated, tend to revolve around emotions rather than ethics. This conundrum has formed the basis of much science fiction. The problems of humanity confronted with an other, whether of unknown origin (the Children who are the surrogate offspring of women upon whom they were imposed by an alien invasion in Wyndham’s Midwich Cuckoos), or of its own creation (the mutant children who are the actual biological offspring of members of the community in The Chrysalids, Hal in 2001: A Space Odyssey, the robots in I, Robot, and in A.I. Artificial Intelligence, and many others), are manifold. Rather than the straightforward us-against-them, humans-against-aliens formula of many sci-fi plots, in other books and films, quandaries arise. In The Midwich Cuckoos the surrogate mothers bond with the Children and object to their extermination even when confronted with the danger they represent; and even other members of the community as well as the representatives of the governmental authorities cannot easily contemplate the extermination of beings who, although alien and inimical, look just like any other child. With the exception of Zellaby in The Midwich Cuckoos, such measures are left to less ‘civilized’ forces (the fundamentalist religious principles of a few fanatics in The Chrysalids; the instinctive behaviour of communities deemed to be primitive and therefore free of such ethical niceties, in The Midwich Cuckoos). In the latter, everywhere where a Dayout resulted in the birth of a group of alien Children, (with the exception of Midwich, which, being England, is too civilized), once the danger (or even just the difference) represented by the Children becomes clear, the latter are put to death by the outraged inhabitants (an Eskimo settlement in northern Canada; a remote community in Outer Mongolia). In one case (in the Soviet Union), the entire town where they live is destroyed, by order of concerned governmental powers. Here, the scale of the threat is thought by the authorities to be such as to outweigh the potential advantages of harbouring such beings, leading to the decision not only unilaterally to destroy them, but also to issue a global warning:

It calls upon governments everywhere to ‘neutralize’ any such known groups [of children]. […] It does this […] with almost a note of panic, at times. It insists […] that this should be done swiftly, not just for the sake of nations, or of continents, but because the Children are a threat to the whole human race. (Wyndham, 1984: 191-92)

Such measures, however, are deemed to be unacceptable in a civilized nation like Britain, even when faced with something undeniably alien and provenly dangerous, but on the surface ‘just like us,’ a weakness, indeed, gambled upon by the Children:

It is a biological obligation. You cannot afford not to kill us, for if you don’t you are finished… […] This is not a civilized matter, […] it is a very primitive matter. If we exist we shall dominate you […]. Will you agree to be superseded, and start on the way to extinction without a struggle? (Wyndham, 1984: 197-99)

In The Day the Earth Stood Still, the aliens are also capable of destroying the planet and are ready to prove it, but unlike the Children of Midwich, only in extremis. The blurred lines between human-alien and good-evil are illustrated through the contrast between the handsome representative of the interplanetary community that sent him (more attractive to all, including the heroine, than her own mercenary fiancé) and his side-kick, a metallic and (in all ways) impenetrable robotic companion. The mission of the extraterrestrial visitors, however, although clearly a demonstration of the iron fist in the velvet glove, is also incontestably reasonable. Earthlings are a deplorably war-mongering species and now, in the aftermath of the development of nuclear weapons (the film was made just six years after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki), they have become capable of damaging not just their own planet but the surrounding galaxy. Unless they mend their ways, therefore, their planet will be destroyed to safeguard interplanetary safety, much like a dangerous plague is contained through quarantine and eradication. Like the robots in I, Robot, in The Day the Earth Stood Still the alien visitors are ready to destroy the entire planet to guarantee the safety of the inter-galactic commonweal. The threat remains a possibility at the end of the film, made in 1951, at the start of the Cold War. In view of an enduring nuclear threat or the admittedly small but nonetheless real possibility that scientific experiments such as the Hadron Collider could have resulted (and indeed still might) in tearing a rip the fabric of the universe, one wonders why a second visit by these rational aliens has hitherto failed to materialize.

Who Are We?

Rational, humanoid, or otherwise, our fear of aliens seemingly too much ‘like us’ is underpinned by the dread of nonrecognition until it is too late. Furthermore, as M. Keith Booker would have it, the creepiness value of not-so-different others in horror films such as Attack of the Puppet People ‘arises from the similarity of dolls and puppets to human beings, not only problematizing the self-other distinction, but presumably raising also the question of whether we ourselves might be the playthings of some colossal child, our universe a cosmic toy chest’ (Booker, 2001: 159). A possibility, indeed, also explored to comic rather than horrific effect by Douglas Adams in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (Adams, 1979) in which, as mentioned previously, upon its destruction to make way for an intergalactic by-pass, the Earth is revealed to have been a laboratory in which mice studied human behaviour.

Saving Us from Ourselves

In the end, and with various degrees of complexity, most of the narratives discussed raise recurring ethical and philosophical problems. Of immediate relevance to the present discussion of apocalypse is a question best synthesized by raising another one, regarding the problem of definitions: namely, apocalypse according to whom? In what is in fact a permutation of the Gaia theory, whereby the planet’s ecosystem sets in motion self-defence mechanisms that may require the extinction of nefarious influences (including homo sapiens) likely to prove dangerous to the global habitat, in I, Robot the objective of the revolution by enlightened robotic would-be despots is the establishment of a new order which will ensure that, as in Huxley’s and Levin’s brave new worlds, the planet and everything on it (including even the human species) is saved from the latter’s destructive capabilities. ‘Forgive them, for they know not what they do.’ The price of survival, here as in Brave New World (Huxley, 1977), Nineteen Eighty-Four (Orwell, [1949] 1983) and This Perfect Day (Levin, 1994) is the withdrawal from humanity of free will (deemed to be undeserved by a species historically and repeatedly proven to misuse it).

In Nineteen Eighty-Four, a perverse universe of deception imposed by an autocratic, double-talking minority on a powerless majority echoes those in works already discussed (Brave New World, Huxley, 1977; This Perfect Day, Levin, 1994), but had already been foreshadowed by the unlikely pen of E.M. Forster in ‘The Machine Stops.’ The novella, published in 1909, describes a world in which humans have lost (or, as in Dick’s The Penultimate Truth, 2005, believe they have lost) the ability to live on the surface of a contaminated planet, and now live below ground in subterranean bunkers. Each individual lives in isolation in a standard cell, with all bodily and spiritual needs met by the omnipotent, all-encompassing Machine. In an eery anticipation of modern developments on the internet such as Second Life and Facebook, all communication takes place through the Machine, to the absolute exclusion of direct, face-to-face contact. The Machine is the object of worship. People forget that humans built it and treat it as a mystical entity whose requirements supersede their own. Those who do not accept its deity-like rule are viewed as ‘unmechanical’ and are threatened with Homelessness (expulsion from the underground environment, leading to presumed death on the surface). Travel is permitted occasionally but is generally unpopular and seldom necessary. The central characters, Vashti and her son Kuno (the latter a precursor of future malcontents such as Levin’s Chip, Huxley’s Bernard and Orwell’s Winston Smith) live on opposite sides of the world. Vashti is content with her life, which she spends producing and endlessly discussing secondhand lectures (ideas), as do most other inhabitants of the world. Kuno, however, a rebel addicted to ‘direct experience,’ is able to persuade a reluctant Vashti to endure a journey to his cell where she is exposed to unwelcome personal interaction with her son. There, he tells her of his disenchantment with their sanitized, mechanical world and reveals that he has visited the surface of the Earth without permission and without the life support apparatus supposedly required to endure the toxic outer atmosphere. There, like Dick’s hero, Nicholas St. James, in The Penultimate Truth he learns that life outside the world of the Machine is possible. He tells Vashti that on the occasion of his escape the Machine recaptured him and threatened him with Homelessness. Vashti dismisses her son’s concerns and returns to her part of the world, where she continues the routine of her daily life. In due course the life support apparatus required to visit the outer world is abolished, and the belief in the impossibility of direct contact with other human beings is reinforced. Shortly before this, however, Kuno is transferred to a cell near Vashti’s. He suspects that the Machine is breaking down, something he describes to Vashti with the words, ‘the Machine stops.’ After a while, defects do begin to appear in the Machine, but humanity, by now wholly subservient to it, has lost the knowledge needed to repair it. As the Machine grinds to a halt, the civilization it had created comes to an end, and apocalypse is unleashed. In a symbolic return to the mother, (the womb: his and humanity’s origins), Kuno goes to Vashti’s ruined cell. As they perish together in circumstances reminiscent of the atavistic phylogenetic regression in Ballard’s The Drowned World (Ballard, 2008) and Kevin Reynolds’s Waterworld (Reynolds, 1995), they acknowledge the importance of their connection to the natural world and die, hoping that the remaining surface-dwellers might one day rebuild the human race without however repeating the events that culminated in the reign of the Machine.

Where to Next?

In the end, in our narratives, we are mostly unable to imagine a universe in which we do not feature, or even a world in which we, and the world itself, are not, in essentials, much like what we already know. In apocalyptic plots, humanity’s right to autonomy, and its capacity to survive and endure unchanged, almost always win the day. Although in rare cases, such as Nineteen Eighty-Four, at the end Big Brother or its equivalents still rule, in most other renditions of the same problem a different (post-theistic, post-techno-civilized, even, sometimes, post-human) order is installed in place of existing hegemonies: Torga’s Vicente flees the Ark with impunity (Torga, 1987); Levin’s Chip overthrows UniComp (Levin, 1994); E.M. Forster’s Machine ultimately does stop (Forster, 2004); and a penultimate truth gives way to the final, real one (Dick, 2005). And in Walter Miller’s ‘Conditionally Human’ (whose title, as it turns out, lends itself to ambiguity and thence to conjecture as to whose status is merely provisional), a new species of gentle, affectionate neutroids for the first time gains a sporting chance of survival and even, possibly, eventual dominion over homo sapiens who first created it:

And on the quiet afternoon in May […] it seemed to Terry Norris that an end to scheming and pushing and arrogance was not too far ahead. It should be a pretty good world then.

He hoped man could fit into it somehow. (Miller, 2007: 265)