FOR NEARLY HALF a century, readers of Allan Wade’s edition of Yeats’s Letters have thought of Thoor Ballylee as a structure that ‘Raftery built and Scott designed’. ‘Raftery’ was Wade’s transcription of the name of the builder in the early version of ‘To Be Carved On A Stone At Thoor Ballylee’ that Yeats sent to John Quinn on July 23, 1918. According to Wade, Yeats told Quinn that, ‘[o]n a great stone beside the front door will be inscribed these lines’:

I, the poet, William Yeats,

With common sedge and broken slates

And smithy work from the Gort forge

Restored this tower for my wife George;

And on my heirs I lay a curse

If they should alter for the worse,

From fashion or an empty mind,

What Raftery built and Scott designed. (L 651; cf., VP 406)

Readers of Wade’s Letters have thus associated the builder of Yeats’s restored tower with Antoine Raftery, the nineteenth century poet whose lyrics in Irish were translated into English by both Douglas Hyde and Lady Gregory, and whose ‘Mise Raifteri An File’ was long a staple of the Irish school curriculum.1

The association seems apt because the vitality of Raftery’s lyrics in the memories of the people near Ballylee was part of the tower’s initial attraction to Yeats. In ‘Dust Hath Closed Helen’s Eye’, first published in the Dome in 1899, and later included in the revised edition of The Celtic Twilight, Yeats tells of having ‘been lately to a little group of houses, not many enough to be called a village, in the barony of Kiltartan’ named Ballylee, where he heard Raftery’s poem in praise of Mary Hynes from an old woman who remembered both Raftery and Mary Hynes (Myth 2005, 18). This link to the last of the great wandering bards so impressed itself on Yeats’s imagination that it was still vivid when he recounted it in his lecture to the Royal Academy of Sweden upon receiving the Nobel Prize (Au 561).

On that memorable early visit to Ballylee, the old miller expanded on the assertion in Raftery’s poem in praise of Mary Hynes that ‘there’s a strong cellar in Ballylee’. The miller at Ballylee explained that the cellar was a hole where the river that ran beside Ballylee Castle sank underground, whence it flowed until it emerged in Coole Lake. ‘Coole Park and Ballylee, 1931’ tells the story:

Under my window-ledge the waters race,

Otters below and moor-hens on the top,

Run for a mile undimmed in Heaven’s face

Then darkening through ‘dark’ Raftery’s ‘cellar’ drop,

Run underground, rise in a rocky place

In Coole demesne, and there to finish up

Spread to a lake and drop into a hole,

What’s water but the generated soul? (VP 490)

Despite the richness of these associations with Raftery the poet, an examination of Yeats’s manuscript letter in the New York Public Library reveals that the letter referred to Rafferty—not Raftery. In fact, the builder who restored Yeats’s tower was Michael Rafferty of nearby Glenbrack, whose extensive correspondence with both W. B. and George Yeats is preserved in the National Library of Ireland (NLI MS 30,663.)

Wade was not the first to confuse the two names. Indeed, the nineteenth century Galway historian, James Hardiman, referred to Raftery as Rafferty on one of the manuscripts he deposited in the collection of the Royal Irish Academy in Dublin.2 Although the two names are ‘sometimes confused,’ Raftery is ‘quite a different name’ from Rafferty in Irish.3 Given Raftery’s allure for Yeats, it is not surprising that Yeats himself was susceptible to the tendency to confuse Raftery with Rafferty. In a series of five letters to Lady Gregory in 1917 and 1918 in which Michael Rafferty uncannily appears in the midst of Yeatsian emotional crises, Yeats mis-identified Rafferty as Raftery in four of the five letters. On 12 August 1917, for example, Yeats, writing to Lady Gregory from Maud Gonne’s home in France, reports on the status of his extraordinary wooing of Iseult Gonne: ‘Iseult and I are on our old intimate terms but I don’t think she will accept. She “has not the impulse.”’ Finding himself in this state of equilibrium, Yeats quickly concludes that ‘[w]hatever happens there will be no immediate need of money, so please see that Raftery goes to work at Ballylee. I told him to put ‘shop shutters’ on cottage but now I do not want him to put any kind of shutter without Scott’s directions’.4

Nine days later, Yeats reports to Lady Gregory from Paris: ‘No change here’ respecting Iseult, but this news is relegated to a position of secondary importance to thanks ‘for Raftery’s estimate’, and word that Yeats was deferring final decisions on ‘doors, etc.’ until he heard from Scott, and thus ‘[i]f Raftery has got to wait he will have plenty to do on roof, walls, etc., so Scott’s advice will not be late’ (L 630; CL InteLex 3312). In three letters in mid-September, Yeats reports to Lady Gregory that Iseult has declined his offer of marriage, but that he has ‘decided to be what some Indian calls ‘true of voice’ and go ‘to Mrs. Tucker’s in the country on Saturday or Monday at latest and I will ask her daughter [Georgie Hyde-Lees] to marry me’’ (L 633). It is no understatement for Yeats to say that ‘life is a good deal at white heat’ (L 632-33; CL InteLex 3325, 3322).

Nonetheless, Rafferty is not far from centre-stage. He reappears in Yeats’s letter to Lady Gregory of 29 October, 1917, which recounts the incredible early days of his marriage, during which the ‘great gloom’ occasioned by his belief that he had ‘betrayed three people’—presumably George, whom he married, and Maud and Iseult Gonne, whom he did not—was displaced by advice conveyed through George’s automatic writing, ‘something very like a miraculous intervention’. Miracle or no, however, before the letter closes, Yeats has time to inquire ‘is Raftery at work on Ballylee?—if he is I will write to Gogorty [sic] and ask him to stir up Scott’ (L 633-34; CL InteLex 3350).

On 4 January 1918 Yeats reported further on the miracle of George’s automatic writing, telling Lady Gregory that ‘a very profound, very exciting mystical philosophy … is coming in strange ways to George and myself’ (L 643; CL InteLex 3384). The mystical philosophy, however, is not discussed until Yeats has first made clear that ‘there are various things Raftery can do at Ballylee’.

Yeats had barely settled into marriage when he shared a new crisis with Lady Gregory. Her son Robert was killed in action over Italy on 23 January 1918. Yeats wrote Lady Gregory on 22 February 1918 that he was ‘trying to write something in verse about Robert’, then quickly returned to the living with the news that ‘Raferty gets on slowly but fairly steadily with his work at Ballylee, and has just written that the rats are eating the thatch’ L 646-7; CL InteLex 3410). In this, the last of the series of five letters to Lady Gregory mentioning Michael Rafferty, Yeats nearly gets the spelling right, writing Raferty for Rafferty (Berg).

Like the knocking at the gate in Macbeth, which, according to De Quincey, reestablishes ‘the goings-on of the world in which we live,’5 Rafferty’s recurring presence in the midst of Yeatsian emotional turmoil seems to anchor the agitated poet to reality. Perhaps Yeats saw Rafferty as an anchor because of the builder’s association with the tower, which Yeats regarded as a ‘rooting of mythology in the earth’ (TSMC 114). Whatever the cause, Rafferty’s extensive correspondence, written in exceptionally beautiful penmanship, shows that, in fact, he was a strong and steady presence—a worthy anchor to reality. For example, Rafferty’s letter of 20 January [1918] to Mrs. Yeats with respect to his hauling stone and slates from the old mill at Kenischa—which sheds light on the source of the ‘old mill boards’ and ‘sea-green slates’ referred to in the final poem (VP 406) —shows Rafferty’s practicality and reliability. He advises that he will defer hauling the stone for the present because ‘I don’t like to start drawing them until the days get longer,’ explaining ‘I don’t wish to be paying horse hire if I can help it till we have a longer day.’ In the same letter, he expresses his satisfaction at the Yeatses having heeded his earlier advice to have the buildings insured. Moreover, he goes on to advise them ‘to insure two workmen which would be a safety in case of accident, as the Workmens Compensation Act enable a workman to sue for damages if hurt while working.’

Rafferty’s good sense sufficiently impressed Lady Gregory that she had cited him the previous summer in support of her advice to Yeats that he defer making decisions about remodeling the cottage at Thoor Ballylee until he resolved which of three possible candidates might be his wife. With characteristic tact, Lady Gregory had suggested ‘that, with the prospect of your marriage questions being settled within the next few months, it seems a pity not to consult your ‘comrade’s’ inclinations before finally plumping into expense on the cottage work.’6 Yeats’s ensuing marriage to George Hyde-Lees in October 1917 had a practical effect on the working arrangements with Rafferty. Lady Gregory—who had saluted Yeats’s wedding by observing that his ‘going into good hands’ was ‘really an ease to my mind’ because she had ‘often felt remorseful at being able to do so little for you’7—reported to Yeats shortly after his wedding that she had paid ‘Raftery’ on his account and suggested that ‘I think it would be better for you to make payment directly to Raftery—having Georgie to write & do accounts for you.8 This suggestion, and the assurance that she and Margaret believed Raftery ‘to be quite honest’ (id.), set in motion the extensive correspondence between Rafferty and George Yeats respecting the work at Thoor Ballylee.

Yeats himself was not exempt from the need to focus on the details of the work. For example, in a letter dated 15 November [19__], Rafferty sent Yeats a drawing of how he intended to use one of the two mill stones, and sought Yeats’s views.

I have the millstone set in hearth as shown by design. I think if the other one was put exactly in centre of castle floor with hole at centre of room, it would look well. Kindly give me your view on the matter.

Rafferty concludes by reporting that he ‘had two horses one day drawing stone from Kenischa Mill,’ promising to ‘write again before the end of the coming week and let you know how the work is getting on,’ and expressing his hope to hear of Mrs. Yeats’s ‘complete recovery by next letter’. All in all, Rafferty measures up to the standard he set for himself in a 24 November [1918] letter to Yeats, in which he notes the reason for his delay, but ‘hope[s] however to give you satisfaction if I can do it by hard work.’

Throughout the extensive correspondence, there is no hint of anything that would support Yeats’s comment, in his letter to Quinn, that Rafferty was ‘a morbid man who cries when anything goes wrong.’9 To the contrary, Yeats’s letter to George on 1 May, 1923 shows that Rafferty’s wit soothed the agitated Yeats by explaining that an intruder at the vacant Thoor Ballylee was probably ‘somebody who wants a job as caretaker.’10 Moreover, Rafferty’s side of the correspondence shows a steady temper in the midst of an apparent dispute over the cost of the work. He advises that the high price of labour and materials is beyond his control, offers to work at a fixed price if the Yeatses supply the material, and establishes the upper hand in the negotiation by suggesting that Yeats might want to get ‘prices from other builders for the work’.11

Rafferty retained Yeats as a client, but lost his place in the final text of the poem. He survived, with his name spelled correctly, through various drafts of the poem, only to be excised from the final draft and the text of the poem as eventually printed in Michael Robartes And The Dancer. One of the drafts, preserved inside the plastic cover of a Cuala Press volume in the possession of Michael Yeats,12 differs significantly from the final poem in that it speaks of a joint restoration of the tower by ‘William Yeats & his wife George.’ Although true to the facts that Mrs. Yeats paid for the work of restoration (see L 647; CL InteLex 3410, and her cheques in the NLI) and engaged in much of the correspondence with Rafferty respecting the particulars of the work, this draft lacks the dramatic effect of the direct, first person assertion by Yeats in the final poem:

William Yeats & his wife George

With smithy work from the Gort forge

And wood from Coole & good brown sedge

Restored this Tower. They call a curse

On him who alters for the worst [alt worse]

From fashion or a vulgar mind

What Rafferty built & Scott designed.

The ‘joint restoration’ version also differs from the poem as sent to John Quinn in that it speculates about a generalized ‘him’ who might alter the tower for the worse, whereas the version sent to Quinn specifically contemplates that it might be ‘my heirs’ who would ‘alter for the worse.’13 Both Rafferty and the heirs appear in a handwritten text by a writer (other than Yeats) who counted the number of letters in each line, apparently with a view toward the carving of the lines on a stone.14 Perhaps driven by a need to shorten the poem to an appropriate size for carving on stone, Yeats’s final version omits any reference to the possibility of alteration of the tower, and focuses—more cleanly and simply—on the wish that ‘these characters remain |When all is ruin once again.’ (VP 406; Plate 7). The focus on the persistence of ‘these characters’ after the inevitable ruin of the tower made for a better poem, but had the effect of excising both Rafferty and Scott from the text.

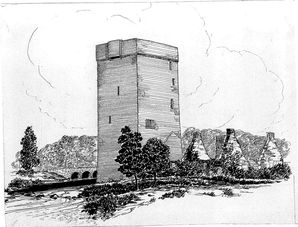

Plate 7. Thoor Ballylee, a pen and ink drawing by A. Norman Jeffares, 17 x 22.5 cm, private collection. This drawing was the basis of a chapter tailpiece vignette in W. B. Yeats: Man and Poet (London: Routledge, 1949).

Rafferty does not reappear in the Yeats letters published by Wade. He does appear in nine additional letters contained in the Berg Collection, with his name spelled Raftery six times, Raferty four times and Rafferty three times. ‘Raftery’ makes a dramatic appearance in Lady Gregory’s published journals, where she reports on 26 October 1922 that he ‘had been shot in the shoulder’ by one of two men whom he had knocked to the ground when he discovered them cutting ‘four trees in the field just sold to Raftery, but that they thought was still ours.’ A subsequent journal entry relates that ‘Raftery … asked me to write a letter about his purchase of the field.’15 Interestingly, when Lady Gregory set out to write a formal letter with legal significance, she correctly identified her neighbour as Michael Rafferty.16 Rafferty quickly recovered. Lady Gregory’s journal for 3 December recounts that:

Raftery walked here this evening from his house. He had got leave to come back with his wife for Sunday, but has to go back tomorrow. He was afraid his youngest child would have forgotten him, but she held out her hands to him when he went in at the door and he is very happy. (Journals 419)

As fate would have it, Rafferty was drawn back to the stage of Yeats’s published writings at another emotional juncture in Yeats’s life—Lady Gregory’s death in 1932. The occasion had a profound impact on Yeats. When Lady Gregory had had a near brush with death in 1909, Yeats told his journal that ‘all day, the thought of losing her is like a conflagration in the rafters. Friendship is all the house I have.’ (Mem 161) Yeats clearly saw the day of her death as a signal event, and wrote an essay on ‘The Death of Lady Gregory’ in which he recounted in careful detail all the events surrounding the death of the woman who had been so dominant a presence in his life.17 Once again, anchoring Yeats to the world of the living, there appeared at Coole, on the morning after Augusta Gregory’s death, her friend and neighbour, the builder of Thoor Ballylee, Michael Rafferty. Spelling his name ‘Raferty,’ and identifying him as ‘the builder & working mason—it was he who repaired Ballylee Castle for me,’ Yeats recounts how he, Rafferty and sculptor Albert Power paid their respects by ‘look[ing] at Lady Gregory’ and going round ‘the principal rooms.’18

An era had ended. Yeats’s relationship to the vicinity of Coole was severed. Michael Rafferty died in 1933 and is buried in the hauntingly beautiful cemetery at Kilmacduagh in the shadow, as fate would have it, of another tower, the round tower that Robinson Jeffers called ‘the great cyclopean-stoned spire | That leans toward its fall.’19 While peripatetic Yeats’s final resting place is uncertain, steady Michael Rafferty, anchor to reality, rests firmly in the earth near the two towers that defined his neighbourhood.

Footnotes

1 Scott was William A. Scott (1871-1918), a prominent architect and Professor of Architecture in the National University of Ireland.

2 Criostoir O’Flynn, Blind Raftery (Indreabhan: An Chead Chlo, 1998), 25-26.

3 Edward MacLysaght, Irish Families (Dublin: Hodges Figgis & Co. Ltd., 1957), 252-53.

4 L 628; CL InteLex 3300. Rafferty’s ensuing bill shows that, like many before and after him, Yeats paid a price for his change in building plans. Rafferty’s bill showed that he had proposed to supply and fix four new frames for the shutters ‘but Mr. Yeats considered it best to have designs from the architect which changed the design and price from six pounds to 24 pounds, five shillings’ (NLI).

5 Thomas De Quincey, ‘The Knocking on the Gate in Macbeth’ (London Magazine, October 1823) in Bonamy Dobrée, ed., Thomas De Quincey (London: B. T. Batsford Ltd., 1965), 83.

6 ALS from AG to WBY, 13 June [1917] (Berg).

7 ALS from AG to WBY, Sunday 14th [October 1917?] (Berg).

8 ALS from AG to WBY, 22 Nov. [1917] (Berg).

9 L 651; CL InteLex 34650. Wade transcribes the portion of the letter identifying Rafferty as “the local builder” but omits, with an ellipsis, the comment quoted in the text. Wade also omits—apparently inadvertently, and without ellipsis—Yeats’s comment on James Joyce that “I think him a most remarkable man.”

10 ALS from WBY to GY, 11 May 1 [1924] (CL InteLex 4539). This and two other letters from WBY to GY refer to Rafferty as Raftery (CL InteLex 4517, 4539). Others spell his name correctly.

11 ALS from Michael Rafferty to GY, n.d. (NLI).

12 Thomas Parkinson and Anne Brannen, Michael Robartes and the Dancer Manuscript Materials (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994), xiii; 200, hereafter Parkinson.

13 The early draft also identifies “wood from Coole” and “good brown sedge” as ingredients in the restoration, rather than the “old mill boards and sea-green slates” of the final poem.

14 Parkinson, 198.

15 Daniel J. Murphy, ed., Lady Gregory’s Journals (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), I, 405, 418.

16 ALS from Lady Gregory to Michael Rafferty, 2 December, 1922 (Berg).

17 W. B. Yeats, ‘The Death of Lady Gregory,’ in Lady Gregory’s Journals, II, 633.

18 Ibid., 635. The text refers to “Arther Power the sculptor,” but Albert Power, who sculpted a bust of Yeats (see L 627; CL InteLex 3284), is apparently intended.

19 Robinson Jeffers, ‘Delusion of Saints,’ in Jeffers, Descent to the Dead (New York: Random House, 1931), 19.