2. Dabbawala Ethics in Transition

Varkari Sampradaya: faith and work

They may be old or great, rich or poor, but they’re all human beings. We have compassion for all human beings, we regard them with love. We distribute food to everyone we meet. We must help everyone. We protect our neighbours. If you have much, then give to the poor. God also gave life to the poor. Do not set them aside. God will give them something good. Everyone has feelings in their minds. Everyone should earn together and share. Eat together, putting things together, living together.

— Raghunath Medge

The tiffin delivery network is not only supported by a complex logistics system (that will be explored further in the next chapter), but also by a special moral code. This code is the expression of the interrelationship between a specific manifestation of the Hindu faith—which can be traced back to the Varkari Sampradaya sect—and India’s unique cultural philosophy. This sect places food at the centre of its philosophy, considering it to be a metaphor for life and its primary, material impulses and spiritual aspirations.

The Varkari Sampradaya (“the tradition of the masters”) sect evolved in the wake of a drive for the renewal of the Hindu religious movement known as Bhakti, which preached pure devotion towards God as the way to salvation.1 These movements developed from the fifth to the sixth century AD in Tamil Nadu, a state in the far south of India. Bhakti means “devoted love” or “loving union”, and indicates a devotional practice not new to Hindu spirituality since it can be traced back through Vedic chants. In the tenth century AD, Bhakti became a more widespread popular movement. Its main attraction and its revolutionary drive within the Hindu tradition came from the idea of a spiritual path open to all, without distinction of gender or caste. It ensured the believer would come into direct contact with God without the need for a go-between.2 These movements clashed with Hindu orthodoxy, which decreed that the Brahmin castes were the masters of rites and go-betweens in the relationship between worshippers and God, ideas that consequently gave Brahmins an overwhelming social status and power.

Varkari Sampradaya is traditionally thought to have emerged around 1100–1120 AD, although this specific Bhakti movement was consolidated by Jnanadeva, whose work Jnaneshvari was actually written in about 1290.3 This is a Marathi commentary on the Bhagavad Gita and is considered the Varkari bible. The text praises devotion to God and to gurus, whom the author says saved him from the corruption of worldly existence. It also celebrates the liberation obtained as a result of attaining mystical union with God; this union is the believer’s ultimate aspiration, although it always remains outside of their grasp, given the immensity of the divine.4 Jnanadeva was the first sant5 of Varkari tradition which also includes Namadeva (c. 1270–1350), Tukarama (1568–1650), Ekanath (c. 1533–1599), as well as several women like Muktabai and Janabai.6

All these figures still inspire the spiritual beliefs of the Mumbai dabbawalas. This religious current in the Nutan Mumbai Tiffin Box Suppliers Charity Trust (NMTBSCT) is manifested in a strong sense of egalitarianism among its members, who come mostly from subordinate castes or are even Outcastes or Dalits.7 Namadeva, for instance, was a tailor, and Tukarama was of the Shudra caste. Recently however, several scholars have argued that in failing to make open criticism of the caste system, the Bhakti movement has involuntarily strengthened it. Furthermore, the disciples of the various Bhakti sects refused to marry in compliance with the membership rules of their own varna and were thus forced to marry amongst themselves. Inevitably this attitude actually created new castes.8

Sants preached not only on social and political issues, but also a doctrine of salvation that included devotion to the name of God, devotion to their own guru, and the importance of religious communion, of coming together in what is called literally “true community” (satsang).9 The devotee must always be committed to the high moral values that are pivotal to the sant’s teachings because these values are not only a source of personal dignity, but also allow devotees to develop mutual respect. Even if a person leads a modest life or lives in outright poverty, their conduct must always be upright and pay service to God, expressing their Bhakti by serving other human beings. Helping others is the equivalent of an act of devotion to God.

Another unique aspect of Varkari Sampradaya is the importance attached to two female figures: in particular the mystical poet Muktabai, who was the sister and co-disciple of Jnanadeva; and Janabai, a servant of Namadeva who devoted verses to Vithoba, addressing the God as a female being named Vithabai. In Janabai’s poetry, as in other works in this tradition, God can be both male and female, and may be addressed in the feminine, as one may address a mother. If the masculine is used, Vithoba is generally linked to Vishnu or the latter’s avatar Krishna, and sometimes it is even linked to Shiva. Vithoba’s cult defies sectarian division, as each year more than 6,000 Vishnu and Shiva devotees go on a pilgrimage to the Vithoba Temple in Pandharpur.10

In 1940, sociologist Irawati Karve took part in a Varkari pilgrimage to Pandharpur, writing a personal description of the experiences of the devout. At the time, the Samyukta Maharashtra movement was promoting the creation of a “united Maharashtra”, whose political materialisation did not come about until two decades later.11 The political commitment to this movement was alive during the pilgrimage and the great flux of Marathi speakers were united by an increasing recognition of their own regional identity.12 For Karve, the pilgrimage was therefore not just a religious event but also represented a metaphor of Maharashtra, a way of giving it a collective definition.13 This political dimension is echoed in the historical moment when the Varkari heritage meshed with that of the great Maratha leader Shivaji, who lived between 1627 and 1680. In the seventeenth century, the Varkari sect was the most important in Maharashtra and the sant Tukarama had a close relationship with Shivaji, archenemy of the Emperor Aurangzeb. It is very likely that in the struggle against the Mughal Empire many Varkaris fought in the ranks of its armies.

Varkari Sampradaya beliefs focus in no small way on the role that food plays in spiritual life. In the poems of the Maratha sants Tukarama, Ekanatha, Namadeva and Jnanadeva, food is present as a metaphor of the encounter with the divine. The worldly or spiritual meal has the task of teaching the eternal values of egalitarianism and brotherhood among the masses. The spiritual practice implies a collective experience of the divine banquet where all are welcome, no food is impure, everyone sits in a circle, nobody is untouchable and all are fed to satiety. The sants may have chosen the food metaphor because it is more understandable to devotees who cannot read or write.14 Although the link between the ethics of the dabbawala association and the Marathi sant message is not always clear, it does seem that the food delivery work of the dabbawalas is inspired at least in part by traditional Varkari Sampradaya ideals.

Talking about himself, Raghunath Medge, president of the NMTBSCT, says:

When I arrived, I was the only dabbawala with a degree and no one else had much of an education. Some had managed fourth year, some sixth, some first, some eighth. Then I understood that providing food really is the best gift of all. Giving food to someone is like serving God. Serving humanity is to serve God [it is serving God indirectly because God is in every person]. The personal intention is the supreme intention, which means that serving food will also bring earnings and receives God’s blessings. Money is needed to keep your family. So serving food is the best gift. Serving people is like serving God. So the soul is satisfied. […] I earn 6,000 or 8,000 rupees per month, so I’m satisfied. I earn what I need to keep my family. We’re happy with this because in our heart of hearts there is the best peace achieved by those who provide this service. So God will give me something in life. My soul is satisfied. Serving people is like serving God. Providing food is the greatest gift there is and it is an important aspect of Varkari Sampradaya. Everyone believes this so they work well. Work as a team, earn money, build your life: this is my idea. Work is worship. If I do my work well it’s like practising puja [worship] of God.

It is difficult to say whether Medge’s sentiment is shared by all the dabbawalas. Certainly the fact of forming a culturally homogeneous group allows members to identify with a shared religious and historical tradition. For example, the entire service takes a four-day break for pilgrimage to Pandharpur.15

Figure 5. Mumbai. This flyer informs customers that the service will be suspended for four days for the annual festival of the dabbawala villages of origin and one day for the national Mahavir Jayanti holiday, which falls between late March and early April of the Gregorian calendar and celebrates the birth of Mahavira, the spiritual teacher of Jainism. By kind permission of Raghunath Medge.

A tangible sign of the shared religious faith of the dabbawalas can also be seen in the dharamshalas, which are stopovers close to temples where pilgrims can stop to rest. Dharamshalas were erected in Bhimashankar in 1930, in Alandi in 1950, in Jejori in 1984, and in Pandharpur in 2000, complying with the wishes of Madhu Havji Bacche, founder of the NMTBSCT. He had initiated construction of the first two dharamshalas and over the years various dabbawala groups contributed to the completion of others via a voluntary donation system. Medge tells the story:

Mr Bacche was Varkari and before coming to Bombay he arranged for dharamshalas to be built. The first was built in 1930 in Bhimashankar, our home village. There is the Jyotilinga Shankarji of Bhagavan, which we call Jyotilinga. We call his Shankarji temple Jyotilinga. But the dabbawalas have built four dharamshalas. One is Bhimashankar, the second is Alandi, the third is Jejori, and the fourth is Pandharpur. Tukaram, Jnaneshvar and Ekanath have written about Rambal Krishna [stories related to Krishna’s childhood], as well as several poems about food. Also more generally about life, about samskar [the religious ritual that marks the main moments of Hindu life], about responsibilities people have. How to be devoted to God. How to respect izzat [family honour and prestige], the elders in the family. How to provide for your parents, worship God. Everything has been written in them. Nivritti is master of Jnanadeva, Mukta which is the abbreviation of Muktabai, Sopa who is the brother of Jnanadeva and Muktabai.16

A Short Story: The Dharamshala Caretaker

I was born in Bombay and I started as a dabbawala when I was twelve. My dad was a dabbawala and he worked with Medge’s father. I never met Bacche, I only knew that he was an important person. He was the one who organised the dabbawala association, turned it into a working group. When they were in Bombay, Bacche, Medge’s father, and my dad stayed together. Living on the street. Bacche also had the idea of building the first dharamshala at Bhimashank. They asked for donations, one rupee, two rupees, five rupees. You can still see all the names. The money was collected over a couple of years: the mukadams gave most money because they ran the line and the dabbawala were employees. After he had collected donations, Bacche bought land and built the dharamshala. Over the years, we built the shops alongside. Here at Alandi there are lots of dharamshalas: the immigrants pay for them to be built, for example the fishmongers have one and so do the greengrocers. But we were the first. When I couldn’t work as a dabbawala anymore, after I had three bicycle accidents, Medge asked me to come and be the caretaker here, at the Alandi dharamshala. I live here, where I have a room with my wife.

Another aspect of dabbawalas’ work that seems to be in line with the Varkari Sampradaya worship ethic is a belief that the human being is a go-between with God. There is a perception that food delivery constitutes an act of religious devotion that reveals the absence of discrimination toward others. Just as the Varkari Sampradaya devotees consider life to be a pilgrimage, the dabbawalas are constantly on the move for their work and for their faith. As one NMTBTC dabbawalas describes:

Our tradition is really to see work as puja. First of all, in our work there’s no discrimination. All of us are Hindus but we bring tiffin to Muslims, Christians, Gujaratis, and any strangers. But we don’t discriminate a Hindu or a Muslim, or any other caste. We certainly don’t. In the same way we lovingly serve food to a Hindu, we also serve others, like Muslims or Christians […] This aspect of our work has never changed and there has never been a reaction like: “Don’t touch a Muslim’s dabba because he’s not vegetarian”. If we deliver food to a Hindu, we also deliver to Muslims. Our distribution network is still the same and doesn’t change. Pick up tiffin, deliver tiffin: if we make a mistake and the customer gets angry, we accept it. We never say: “Brother, that’s another jati’s!” Anyone can do a job for money, but tiffin work is different. You can’t discriminate or make caste and religious distinctions. Do your job, that’s it. For example, at Marine Line there’s a Muslim area and anyone who goes there is afraid and removes their topi [the cap worn by Hindus]. Hindu workers take off their hats when they go to a Muslim area. But we’re not worried because we’re doing our job and not discriminating anyone. Anyone who discriminates is afraid. We’re not frightened. Dabbawalas work there every day because we have to earn money, but earning can be in different ways. This way, there is hard work. In human relationships, delivering food to another is a kind of job that means you cannot discriminate.

The origins of a lineage

The warrior prince Shivaji is our ancestor, the father of the father of our paternal grandfather; the whole family descends from him. Chattrapati Shivaji was king; Chattrapati Shivaji was an emperor. We were first his soldiers but that is now in the past. Now we don’t have soldiers any more. Now there is the government. We have to earn money and to do that we have to work. Now we pay service to sadhus [ascetics] and sants. […] This is strength. This is devotion. Strength is needed for all work. We learned this from him. To do business, kindness is required. We learned that from them. We learned kindness from the sants and courage from the emperor. We believe in the same Sampradaya as the pilgrims. Our families believe that providing food is punya, a worthy action that brings religious virtue: work is worship. Serving food is considered a worthy action.

—Raghunath Medge

The dabbawalas define themselves as descendants of the warrior prince Shivaji Bhonsle. He is considered by his followers to be the founder of the Maratha nation because of his relentless struggle against the hegemony of the Mughal Empire. The Emperor Aurangzeb, who contemptuously called him the “Deccan mountain rat” never managed to defeat the tireless rebel. The Emperor’s objective was the gradual transformation of the Empire into a Muslim State, which was implemented—although never completely and never successfully—through the introduction of Islamic law and the elimination of a series of symbols that supported a secular state. The response was a Maratha battle against Muslims. Through guerrilla warfare Marathas avoided fighting out in the open, but destroyed enemy lines of communication and assaulted isolated detachments. This approach required a large number of soldiers, many of whom were recruited amongst Maharashtra farmers, who are probably the ancestors of today’s dabbawalas. Shivaji’s profound knowledge of the territory allowed him to achieve military success, which brought him a reputation as one of the fathers of modern guerrilla warfare. In 1674, during a traditional Hindu ceremony, he was crowned Chattrapati or “Lord of the Universe” by Ramdas, a sant of the Varkari tradition. Contemporary Indians consider Shivaji important for his contribution to the forging of a proud Hindu nationalist spirit in his people.17 The dabbawalas see themselves as bonded to Shivaji by a shared Hindu faith, a fierce sense of independence from any domination, and patriotism towards the State of Maharashtra.

Shivaji is a pivotal figure in Maharashtrian beliefs, fundamental to the understanding of events that developed the political and social scene of recent decades. The mythology of Shivaji is crucial to understand the symbolic reconstruction that underpins Indian systems of political rhetoric, in particular those of the Marathas. Sometimes the interpretations of Shivaji’s contribution differ between Western and Indian scholars. Without detracting from the importance of the Indian studies, they are often ideologically oriented within the Hindu nationalist movement, which reconstructs Shivaji’s heroics and the Maratha movement using not entirely reliable historical sources. For example, in a work by the judge and reformer Mahadev Govind Ranade, Maharashtra’s cultural unity already had its own common language with an important literary tradition, which then evolved into modern Marathi. According to Ranade, this process of linguistic and symbolic amalgamation may also have led to the development of shared social structures and moral codes.

In this perspective, Shivaji’s role was similar to an enzyme in a catalytic process that has already started, bringing together all Marathi-speaking people under one banner and instilling in them a stronger sense of cohesion and community. Ranade also attaches great importance to the Maharashtrian Bhakti movement, which is to say the Varkari Sampradaya that promoted a society without castes.18 This, as well as other historical theories that emphasise Shivaji’s non-Brahmin dimension, highlight how Maharashtra’s political and religious history comprises a complex set of icons, symbols, and proto-ideological ideas which twentieth-century local Indian politics drew upon to develop an independent ideological scheme.

Evidence that the anti-caste drive and religious renewal that had crossed the region from at least the twelfth century became more powerful under Shivaji is also found in the reconstruction of a dispute between Shivaji and local Brahmins, who had denied Kshatriya status to the Kunbi farming caste that later evolved into the Maratha warrior caste.19 Shivaji opposed this decision by handing out privileges and powers to Kunbis who distinguished themselves by their service (mostly military) to the monarch. This challenge to the Brahmin establishment is always an inspirational presence in the Bhakti movement. The story also gives a new symbolic significance to the pre-Aryan divinities: for instance, legend has it that the goddess Bhavani gave Shivaji her invincible sword.20 Further proof of Shivaji’s revolutionary potential can also be found in the post-Independence appearance of readings inspired by Ghandian and Marxist thought, celebrating Shivaji as the enlightened ruler who abolished forced labour and became the symbol of the battle to end the caste system.21

Notwithstanding the merits of their sources, these various historiographical interpretations stress that Shivaji is generally considered to be the father of Maharashtrian nationalism, a powerful archetype who can bring new life to Hindu identity. Shivaji’s appeal was an important factor in the political debate surrounding the formation of the State of Maharashtra and the development of post-colonial Mumbai’s urban culture. It appears that the ethical canons chosen by the dabbawalas are also taken from this legendary ancestor, including gender equality, non-discrimination, Hindu religious beliefs, and the idea of work as a source of strength and liberation from poverty. A retired dabbawala and son of the NMTBSCT founder says:

At the beginning there was only one group of dabbawalas, then other groups formed. Then the groups joined together to create the association. That’s the thing about dabbawala work: we can get jobs for everyone if we’re a group, and that allows us to deliver tiffin. If I work alone, I won’t manage. If you serve people, God blesses you, and serving people is like serving God. The spirit is content if a job is done well, if it is performed properly. This is the Varkari Sampradaya way: live correctly, earn correctly, work correctly. Do not take work from others. Do not earn illegally. This is our Varkari Sampradaya law. We Varkaris do not see any differences to do with jati.

Caste and descent

Caste is a complex concept and should always be approached with caution and sensitivity given its social, economic, ethnic and religious implications. Many Indian intellectuals are uneasy when they see their society constantly described and interpreted through caste. There are primarily two reasons for this: the first is linked to the awareness that the analysis of India’s caste system is largely a product of western Orientalism;22 the other lies in the fact that this analysis seems to reduce the complexity of India’s (and its diaspora’s) social and economic development to archaic, unchanging categories, without adequate consideration of the massive transformations that modernisation processes and migration dynamics have triggered in India. Rules regarding contamination caused by contact with individuals considered inferior by birth or for frequenting specific places (like hospitals) are being increasingly ignored. The connection between caste and professional specialisations, especially in urban contexts, has also lessened considerably.23

According to Ronald Inden, for far too long western scholars have described Indian society as essentially condemned to backwardness for a number of reasons, with a strong emphasis on the caste system.24 The formal codifications of the system are proposed as a tool for interpreting the present without verifying what the reality has actually become. For Inden, this ahistorical and ingrained approach to Indian civilisation and society constitutes the main weakness of many Indological perspectives of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. More recently in India, and particularly in the state of Maharashtra, caste rhetoric has been put to controversial political use, especially by the neo-Hindu movement of which the Bharatiya Janata Party is the leading political player. Looking for an alleged racial authenticity, the party used Mumbai as its stage for economic and social demands increasingly and explicitly based on linguistic and caste affiliation.25

To avoid these methodological and ideological pitfalls, it would seem best to introduce a historical perspective for analysing the relevance of caste in relation to the social organisation of the dabbawalas.26 The main stages of this interpretive path are based on an introduction to the concept of caste, an analysis of the bond that links the formation of the Maratha caste with the historical figure of the warrior Shivaji and, lastly, the contextualisation of the development of caste dynamics in Bombay’s industrial and commercial history. A detailed discussion of the political and social life of the city in recent decades does not fall within the remit of this book but, in order to understand the collective dabbawala experience, it is necessary to give a brief overview of the particular cultural-political sphere of which it is part.

A brief introduction to the caste concept

The main traditional sources of Hindu doctrine, the Purusha-sukta hymn in the Rigveda (late second and early first millennium BC) and the Manu Smrti (the Laws of Manu, first millennium BC), indicate that in the caste system the social order is governed by a hierarchy evolved on the basis of ritual purity. The constituent elements of this social order are the categories (identified by means of their varna, or symbolic “colour”) attributed with the three fundamental functions of Indo-Aryan society from the time of its origins. The Brahmins, or priests, have the colour white; the Kshatriya or princes and noble warriors are designated with the colour red; the vaishya or the people (farmers and traders) are symbolically yellow. These three categories (called varna arya or “noble colours”), found in all the different populations that speak Indo-European languages, then became four, with the addition of the shudra, given the symbolic colour black and representing the mass of non-nobles (varna an-arya) referred to by the generic name of dasa (“servants”).

The Laws of Manu entrust the dasa with the task of “serving” the three noble categories also called dvija (which means regenerated or born twice, as their official entrance into society occurs through a rite of initiation that marks a second birth, conferring them with a further positive quality). The different groups of people and, in the broadest sense, the different forms of existence acquired at birth within the varna, are called jati (a word derived from the Sanskrit root jan, meaning “to generate”, a term that incorporates functional and hereditary caste aspects). The actual word “caste” is a Portuguese translation of the term jati, which missionaries rendered with a term that meant “pure” in their language.27 The first three varnas, those of the dvijas, at least theoretically constitute an equal number of jati whose internal subdivisions are usually regarded as subcastes or upajatis, and differ amongst themselves in accordance with family, type of employment, or origin, while a huge number of jatis converge in the shudra varnas, distinguished mainly on the basis of employment or service rendered to the dominant caste.28

Critical interpretations of Hindu ideology and the caste system tend to fall into two different, but in some respects complementary, approaches. The first, preferred above all by Max Weber, fuses the institutionalisation of inequality with the concepts of dharma, samsara and karma.29 Dharma, which is “moral order”, is the ethical imperative that urges the individual to comply with the divine laws of conduct associated with each caste. If the person performs this task adequately, their karma, or “a present action able to influence their rebirth positively or negatively”, will be positive and after their death will allow their spirit to flow back into the samsara, or “the eternal cycle of births and deaths”, with the prospect of reincarnation in a higher caste. Otherwise, they will be reborn into a lower caste or even inferior life forms like animals, plants, etc. The relationship that links the various castes is thus arranged to comply with principles of complementarity and consequently everyone should be eager to maintain a social order that conforms to a moral order (dharma).30 The second approach is that proposed by Louis Dumont, which places the emphasis on the concepts of purity and contamination, as well as on the strict separation of religion from politics and economics.31 Priests are afforded a higher status, beyond considerations of economic or political power, and the caste system should respect compliance of the human sphere with dharma laws, therefore contributing to balance and harmony.

Both approaches have generated extensive criticisms and theoretical developments, and debate continues on the ideological, ethical-religious, political, economic, social and cultural foundations of the caste system.32 Stefano Piano writes that historically the Indian caste system has assumed the characteristics of a closed social group, defined almost exclusively by birth. It includes a number of families and is often, but not always, associated with employment. It is quite significantly characterised by ethnicity and religious or geographical origin and intermarriage. The behaviour of its members is influenced by precise dietary and shared eating rules.33 In more general sociological terms, a caste can be defined as an ascriptive aggregation by right of birth, rigidly superordinated or subordinated to other aggregations of the same type, within a social stratification system in which individuals are not permitted any vertical mobility. David Mamo writes that this interpretation of castes indicates they are distinct social and cultural entities. As such, they tend to create internal subcultures as a consequence of the intensity and quality of communication within the group, compared to that of the group with others. In fact, such communication is fostered and preferred as it is functional to the strengthening of a sense of caste identity.34

Caste and industrialisation in Bombay

As discussed in Chapter One, caste, kinship, and rural-urban relations or rural connections were fundamental to Bombay’s social organisation, so much so that some historians and anthropologists have defined Indian cities as “an urban landscape composed of rural institutions”.35 It is difficult to estimate the exact weight of the caste system either in old Bombay or in modern-day Mumbai, because there has been a significant propensity to believe that castes are not an appropriate social organisation for an industrial urban context.

Davis Kingsley put forward the hypothesis that, with the rapid increase of industrialisation, the caste system would disappear.36 On the other hand, historian Rajnarayan Chandavarkar posited that the current notion of caste would be reformulated incrementally to reflect the growing importance of cities in Indian society. Morris D. Morris, however, argues that the alleged disappearance of castes in the cities is mainly due to the difficulty of finding reliable historical sources to document their existence, and that the role of caste dynamics in Bombay’s early industrial labour market has been underplayed.37 Some scholars have also suggested that caste dynamics exist mainly within the private social sphere and are actually disappearing from the public world.

Bombay’s industrial and social history has shown, instead, that it has two contexts: one public and one private. They are always closely interconnected and interdependent because the social organisation of urban workplaces is linked to neighbourhood and family relationships, as well as regional origins.38 There is little data on the caste composition of Bombay workers, but according to a 1940s survey commissioned by the Bombay Mill Owners Association (BMOA), which referred to the workforce in nineteen factories, most seemed to be Marathas and Kunbi Hindus (approximately 51.8%); Bhayas make up 13.8%; Untouchables accounted for 11.9% and the remaining 5.2% were Muslims.39

The difficulty in defining a worker caste profile lies in the fact that factory register entries are generic, and indicate only religion, jati and place of origin; moreover they lack uniform and mutually exclusive criteria.40 The survey mentioned by Morris noted a relatively low percentage of Untouchables, but that seems to have grown subsequently.41 It is likely that during the launch of the first cotton mills there were few Untouchables in the city since other workers were reluctant to be in the vicinity of Dalits. A document issued by a United Spinning and Weaving Mills manager in 1874 prohibited Untouchables from working in these factories. In the early twentieth century, the number of Untouchables rose significantly and stabilised in the 1920s and 1930s, during industrial strikes. The Dalits’ greater vulnerability meant they could be blackmailed and were often recruited as strike-breakers. During the 1929 general strike, for example, the prominent political Dalit leader Ambedkar strove to provide the workforce needed to continue cotton production.42 Ambedkar became an icon of the Dalit struggle for emancipation and he used this to consolidate the presence of the Untouchables in the industrial workforce, convinced that this might help to reinforce their political capacity and social position.

Importantly, the urban context has partly changed the caste concept by breaking down distinctions based on intermarriage, eating habits, and shared linguistic, regional or religious traits. Bombay’s biggest caste, the Marathas, is actually deemed to be the expression of broader caste units, allied to improve their chances on the city’s labour market.43 Uniting in associations governed by the most influential members, the so-called dadas,44 these groups of people of disparate caste origin are nonetheless able to identify with a wider Maratha denomination. These multi-caste conglomerates often organised whip-rounds to raise funds, and set up a subscription system to ensure welfare and job mediation services for their affiliates.45 Maharashtra society, which is characterised by a certain linguistic and cultural homogeneity that probably facilitated this process, saw numerous jati farmers join the Maratha caste. Through these new affiliations, Rajnarayan Chandavarkar suggests that “caste identities came to be expressed in caste associations which could operate throughout the city”.46 Although they could all be traced back to the same Maratha designation, these “caste associations” allow their members to express their experience of the city on the basis of the various affiliations that made most sense: the village of origin: a shared language (dialect), the district of residence in Bombay, level of education, etc. All of these are transversal affiliations connected to the person’s past that allow them to transcend their jati or upajati origins.

The NMTBSCT has all the features of these caste associations. In addition to the prominence given by the internal hierarchies to the Maratha identity and its most important icons (starting with Chattrapati Shivaji), there were also the common rural origins of many affiliates and a shared language base. Gangaram Talekar, the NMTBSCT secretary, describes the dabbawala affiliation:

I’m from the Pune district and I came to Mumbai to do tiffin work. The name of my village is Rajgurunagar and it’s near Pune. We’re from there […] Rajgurunagar, Ambegaon, Maval, Munshi, Akola, Sangamner. All of us dabbawalas come from there and we’ve been doing this work for a few years. I’m the third generation of tiffin workers: at the beginning my father did it, and his brother-in-law worked with him. Then in 1956 I started too. My family and Medge’s worked together, the two families are like one family. We’re very close… like brothers.47 We’re all one family [points to a boy who works as a dabbawala] and it’s as if he was the son of an uncle or brother. That’s how it is with dabbawalas, everyone is related to someone else.

One thing that seems to reinforce the association’s identity matrix (although it should be put into the context of a relational mode that is common and widespread throughout India, and which is part of a consolidated code of conduct) is the habit of calling their colleagues with nicknames that refer to the family, and which are assigned according to the age of the person in question. Dabbawalas will call an older person dada (paternal grandfather) or kaka (younger paternal uncle, in other words the father’s younger brother). Peers may call each other bhai, bhau, bhaiya or “brother”. One of four female dabbawalas in the association is called mami or “aunt” (mother’s brother’s wife). Medge explains:

There are also women dabbawalas who do light work. For example, if the husband is ill, the woman goes to work in the fields. If someone is injured, is in hospital, isn’t feeling well, the woman has to help out. Women are given light tasks in the work group. Take Lakshmibai: she works in the Santacruz station and lives in Kandivali. We dabbawalas call her ‘mami’. We often call each other with the names of family members… dada, bhai, bhau. For instance, in his group Choudhary is known as Mukadam, Dada Mukadam, Choudhary Mukadam. As happens in a family.

Just as labour recruitment in Bombay’s large cotton mills during the first decades of the twentieth century occurred through complex interwoven links among castes, family, and neighbourhood, today’s channelling of the labour force in Mumbai’s tertiary economy occurs in the same way, especially in contexts where informal economy is prevalent. If the caste associations, of which the NMTBSCT is an example, have been able to act as engines of empowerment for their members, enhancing their contractual position (and, of course, that of the associations themselves), it is largely due to the strong symbolic and affective intensity of the relationships among their members.

The key to the transmission and promotion of these interdependencies has always been the family, which continues to act as a mediator between the private and the public spheres, even in the metropolis. On one hand, the family maintains its significance as the matrix for organising migration plans, marriages between the same jatis, or professional careers. On the other, it stands as a relationship model in an urban context of social relations shaped by supra-urban and supra-national economic, social and political forces. The metropolitan arena is a place where various caste associations live in close contact and never achieve cultural equality, but simply create a dense fabric of transversal relations that find their identity in the interrelation within these associations.

The question of the dabbawala “caste”

Our caste is Maratha, from Maharashtra. It’s Hindu. Shivaji was a Maratha Hindu.

—Raghunath Medge

In this composite cultural and social order, the dabbawalas see themselves as a “Maratha caste”, part of the Kshatriya varna of warriors and fighters. As already seen, however, most of the dabbawalas originate from the western part of the state of Maharashtra, from small rural villages. Although they are not so far away from the city, their areas of origin have a completely different landscape to that of the city, dominated by cultivated fields and hills covered with sparse bushes. The economy of the home villages is predominantly agricultural and most work derives from this sector: agriculture and dairy farming, with a modest amount of secondary businesses. Medge says: “My wife and my daughter live in Mumbai, my mum lives in the village of Vajori in Rajgurunagar, which is in the Pune district, so she can tend the fields. There’s also my uncle, who was my father’s brother, and his son. Those who are able to work can also live in Bombay, while those who can’t work stay in the village”.

Mukadam, one of the NMTBSCT dabbawalas, explains his family’s geographical situation:

I live in Goregaon with my family, with the brothers who live here. Two are dabbawalas, one is a BST [local Bombay bus service] bus driver. He used to be a dabbawala, but now he drives buses. I have two daughters and a son, but my son is seventeen and studies. My other brother and his family stayed in the village because there’s nobody else to tend the fields, so he’s there with my mother who is alone since my father died.

Work in the fields does not ensure a steady income, hence the desire to migrate to a big city and guarantee the family additional earnings. Most dabbawala families do not move to the city as a group. Family members stay in the village, where they continue to farm small plots of land that they own or rent. This migration from the countryside to the city developed with the same dynamics described by cumulative causation theories of contemporary migrations, particularly “chain migration”.48 Sporadic chances to cope with the increased family risks which arise from the effects that metropolitan development triggers on the outskirts will gradually consolidate into a chain migration phenomena facilitated by strengthened family networks and shared geographical origin. The consolidation of migratory movements contributes to the stabilisation of flows because the families of the migrants eventually enjoy an enhanced income and elevation of their social status. Conversely, the families of those who cannot or will not emigrate are the victims of increasing relative poverty.49

In the case of the Mumbai dabbawalas the existence of a migration chain with a considerable history has actually helped build a culture of migration into urban areas with unique features—for instance, the conservation of an ethic founded in rural virtues combined with the encouragement of new migration from villages around Pune towards the metropolis. One NMTBSCT dabbawala describes his employment history and patterns of migration:

I’ve been a dabbawala for 25 or 30 years. I come from the village and before I was a dabbawala I worked in a paper factory there: Auto Plane Paper. I also worked in the fields: I’ve done everything. But there wasn’t enough to live on, so I came here. Sometimes there’s rain in the village, sometimes there’s none, and sometimes there’s too much. That’s how farm work is. But I’m not the only one—lots of people from my village have left the fields and gone to do other work. At home now there are one or two men for the fields. The others all do other work. There’s no money. What can we do? We go to the city to do other work. I like working in the fields but you can’t fill a whole family’s stomachs with it. It’s a bad business but it’s the same for everyone.

Another tells a similar story, in which his family’s income is at the mercy of unpredictable farming conditions and increasingly stretched resources:

I have two sons. One is studying and he’s just finished class twelve. He’s working in a clothing store at the moment. The other one works in an airline ticket office. When I retire, I’m going back to the village. There’s no pension here so you have to work to get the money you need for the future. The association doesn’t give you anything. You just work while you can and then you go back to the village. There’s no support. Back at the village I’ve a home and fields. The reason we’re here is because we don’t get rain on time now. Before the fields gave crops, but not anymore. The new generation has increased. A village used to have two men, now there are two hundred, but the fields haven’t increased, they’re still the same. Land ownership doesn’t increase: the population grows but an acre of land is just an acre of land. A man has two sons, two sons have four sons, then they have to move away to work, otherwise who would leave their villages and their ways! Now, if you’re working in an office, they tell you ‘You have to dress this way!’, but our tiffin work is not like that. Our customs are the same as back in the village. We work in the same way. That’s why I like it.

The heavy exploitation of the territory, including excessive deforestation in recent years, has significantly deteriorated the conditions of agricultural work. Drought and torrential rain have eroded arable land, rendering it infertile and difficult to work. All this has contributed to increasing emigration towards Mumbai.

A number of testimonies indicate that some dabbawalas identify themselves with the Kunbi jati, a caste found in Pune who work the land (Kunbis and Marathas are closely approximated, and in the 1931 census they were classified as one category).50 There is a possibility that before enlisting in Shivaji’s army the ancestors of the dabbawalas were Vaishya varna and that at the time the term “Maratha” was simply an ethno-linguistic designation identifying Marathi-speaking people. It seems that the intense relationship between Shivaji and the Varkari movement allowed the Kunbis to join its ranks and undertake a “varna leap”. In this way, they were admitted to the Vaishya varna, and this was when the term Maratha began referring to a caste.51 Thus, the term Maratha identified first the people recruited as warriors and then became an explicit caste indicator, subsequently reproduced and reinforced through intermarriage. Medge explains:

We dabbawalas are farmers from the same rural area and we’re all part of Varkari Sampradaya. We have great consideration of God and the sadhus. We’re illiterate, we don’t know how to read and write, so we’re not able to do office work. We don’t speak English and we have to learn Hindi when we get to Bombay. We have to study it because it’s our national language, so we can communicate with customers. In our Sampradaya we consider food to be like a divinity, we wear God’s garland. Serving human beings, serving is like rendering service to God, like meeting God. Sampradaya people are all vegetarian and we even take food to young children, to primary and secondary schools, because their parents work in offices and they order food for their children from the dabbawalas. “Hindu Kshatriya”—Shivaji is a soldier! To do hard work, you have to be Kshatriya. In our Sampradaya we revere sadhus deeply, so that our work goes well. Customer satisfaction, good service, are what a Varkari Sampradaya offers. You need a Kshatriya for hard work.

This brief review of how the Maratha caste developed is just the tip of the iceberg: it is in no way a complete picture of dabbawala caste organisation, because some workers have different origins from the Pune area. It is significant, however, that most of the dabbawalas come from the same territorial and cultural backgrounds as did most of the Bombay cotton mill workers, which facilitated the development and success of their delivery service. In the same way as other caste associations, the dabbawalas have built their business on the basis of existing linguistic, regional and caste ties, using these common factors as a resource that would generate capital. In Mumbai today, those who are collectively known and recognised as “Marathas” cannot actually be traced precisely to a specific jati. The reason is the gradual erosion of the kinship system organised according to the traditional tenets of intermarriage and shared eating habits that underpin the caste concept, following increased rural migration to the city.

Historically, caste identity was reinforced by conflict and antagonism between Brahmins and Kshatriyas in nineteenth- and twentieth-century public Hindu debates. Brahmins were progressively seen as educated but arrogant, and came to be represented as an effeminate, decadent expression of urban culture. In this way they were a total contrast to the basic Maratha Kshatriya varna values of warfare, rural virtues (honesty, frugality, humility, decorum, etc), devotion to the Bhakti movement and emphasis on a regional, suburban background.52 In Mumbai the significance of belonging to a caste increased insofar as it gave access to overlapping networks. These networks were made acceptable and expendable because of shared ideals of rural virtues, economic opportunities, local alliances, and group affinities that emerge on each occasion thanks to common interests and migration processes.53

Food as a cosmic principle

Dabbawalas consider their work as performing puja. I’m very devout: I have a lot of faith in God. Serving food [the speaker used the Sanskrit word anna] is a very important thing. The fact is, if you don’t bring the food on time, if the dabba is late for lunchtime, it’s a sad moment for the person who doesn’t get the food they’re waiting for. When it’s lunchtime, the customer will be hungry. So our job is to deliver the dabba and if you arrive at lunchtime, the customer is satisfied; they get their food and they’re happy. That’s the work, you deliver food to others, so it’s good work.

—Director at the NMTBSTC

The NMTBSCT meal delivery service is founded on the unique role that food plays in Indian culture. The concept of “gastrosemantics” is used to define this value that, according to Indian anthropologist Ravindra S. Khare, indicates “a culture’s distinct capacity to signify, experience, systematise, philosophise, and communicate with food and food practices by pressing appropriate linguistic and cultural devices”.54 Khare’s definition points to the pivotal role played by food in India, and is useful for delineating the ritual practices, social behaviour and theological speculations linked to it. Food in India expresses a multitude of classifications—from satisfying daily biological needs to defining social and family relationships, economic transactions, hierarchical boundaries, and ethical and legal systems.55 Food may be approximated to linguistics, aesthetics and grammar for its abstract language; on the other hand, it is a tangible, physical, material substance. This turns it into a cluster of moral meanings and expressions that reflect the needs of the body and its aspiration to spiritual liberation.56

This section does not claim to give a detailed picture of all the different meanings that food acquires in India and its many different cultures. Rather it attempts to define the essence and cultural experience that food evokes among Indians. Referring back to the work by Khare, the term Hindu is used to indicate various traditions that share a common historical civilisation path, so even talking about “Hindu food” becomes infinitely complicated.57 There is no attempt here to standardise the various cultural, ethnic, religious and linguistic currents present in India, only the desire to find a common denominator. Although Hindus, Buddhists and Jains (to name but a few of the many beliefs found in India) share similar food practices, each group has its own gastrosemantics: food and the act of eating it are a multiple but uniform Hindu “Ultimate Reality”; the Jains are subject to strict austerity and denial; Buddhists follow a principle of moderation.58

Although it can be asserted that every community in India has different food ethics, it is still possible to trace a common origin when investigating ancient beliefs and the practices of the various groups speaking Aryan languages. The Aryan peoples settled on the northern Indian plain in about 1500 BC, arriving from central Asia, and their beliefs spread mostly in that part of India.59 Their food model was based on sheep rearing and agriculture, and was underpinned by a philosophical consideration of eating. Food was not only a form of subsistence but also a fundamental part of the great Aryan cosmic moral circle where those who eat—and the food they eat—must be in harmony with the Universe. The food ingested, in relation to this harmony, gives rise to three major transformations: faeces, meat and manas or thought, which is the most precious transformation.60 In Sylvain Lévi’s opinion, Aryan or Vedic culture was characterised by a strong element of violence generated by the frequent use of meat in individual sustenance. Lévi defines the culture as “brutal” and “materialistic”, and its most becoming expression was in the leitmotif of the food and the eaters.61

Wendy Doniger has suggested that the nutritional chain describes the order of the species: “what might appear as a culinary metaphor was really meant as a descriptive account of the natural and social world as organised in a hierarchically ordered food chain”.62 In other words, each species eats in proportion to its strength: from big to small, from strong to weak. The linear sequence described delimits a social space, which is reflected in natural space and in ritual sacrifice, whose expression renews the scale of values. Vedic norms were overturned with the spread of the figure of the renouncer in about the sixth century BC, and were conveyed by religious currents within the Hindus, like the Bhakti, who placed emphasis on service and love.

Great spiritual masters like Buddha and Mahavira (the highest authority of Jainism) promoted a purely vegetarian diet in the fifth century BC.63 Vegetarianism (as well as non-violence), now considered to be the utmost expression of spirituality, was a revolution in Indian society because abstaining from consumption of meat became synonymous with purity and the marker of a true reversal of social values.64 The new diet was not only an expression of a different cuisine, but a new cultural model and worldview.65 Paradoxically, however, the vegetarian choice promoted by Jains and Buddhists strengthened open discrimination against the Aboriginal peoples who lived by hunting and gathering. Through an act of political opportunism they were relegated to the margins of society, deemed as impure and classified as Untouchables of the Dalit caste.

Sanskrit literature also addresses considerations regarding food and sees the placid, generous cow as the quintessential symbol of restraint in the consumption of meat.66 Athraveda, for example, emphasises how the cow should be sacrificed only if sterile. The Brahmins and subsequent Upanishads raise doubts as to the use of ritual sacrifices with animal victims.67 The new spiritual orientation maps out the production and circulation of food applying cosmic logic. The Upanishads affirm that food is a manifestation of Brahma, the Ultimate Reality, and that it influences a Hindu’s interior life to the point of controlling development from one birth to another. For this reason there are multiple food classification charts to establish appropriate roles for nutrition practices. It is essential to specify the contexts, conditions, and quality of the food to be consumed or avoided, because the inner state of the being in this world and beyond is intimately connected to what a person eats.68 This is dharma, the cosmic moral order that regulates food availability for all creatures and at the same time is also expressed through complex social distinctions and rituals.69 This “talking food”, to use Khare’s phrase,70 culminates in the production of a non-dichotomised bond between the creator, the body, and the “I”, evolving from a need rooted in materiality into an expression of the person’s interior life: from generative commodity to cosmic ideal.

This complex universe is seen in the daily lives of people at home and at work, in various ways, since ethical and religious principles are still very much alive in earthly life. In the pragmatic social dimension there is constant interaction between the human and the divine, and it is not limited to the places set aside for worship.71 Gavin Flood makes an interesting distinction between public and soteriological religion: if the latter addresses the individual and their salvation, the former is “the regulation of communities, the ritual structuring of a person’s passage through life and the successful transition, at death, to another world” and “concerned with legitimising hierarchical social relationships and propitiating deities”.72 For the devotee, food is a comprehensive, delicate language marked by a broad spectrum of cosmic, social, karmic, spiritual and emotional messages: a language that speaks both through the choice of ingredients and beyond the boundaries of materiality.

Food-related holy practices

Eaten or even just handled, food is known to have a dual action. First, it provides biological support for the body’s vital processes; secondly, it acts to achieve experiences of “a more subtle nature” because it allows for the amplification of spiritual perceptions by linking belly, mind and soul.73 Foods, especially those considered “good” or “pure”, allow humans to renew primeval harmony among all nature’s creatures. The act of eating actually implies the destruction of a being and awareness of this violence, directly linked to death. This means that the act in itself is problematic, especially with regard to the consumption of meat, which requires the eater to perform a purification ritual to expiate the guilt linked to violence and restore the bond that has been broken by the killing. In turn, the ritual legitimises the eternal nutrition cycle sequence.

Moreover, Nature—perceived as a deity—suffers predatory human actions: agriculture and the gathering of wild berries are part of an exploitation system that causes humanity to seek a justification for its acts. This occurs through rituals celebrating the perpetuation of life by a sacrifice that appears in different forms and may involve people, animals, nature and divinities. The sacrifice generates a pact between living beings, linking them in an ongoing sequence of life and death. The banquet, which everyone attends although in different ways (there are those who eat and those who are eaten), becomes the privileged channel for achieving an inner opening towards the hallowed and greater communion with the divine. Notions underlying the classification of foods thus assume primary importance, since the level of purity brings spiritual elevation of different intensities. This classification differs depending on the various cultures that developed in India.

The spiritual rules connected to nutrition are extensively articulated in the practice of Ayurveda, a term of Sanskrit origin meaning knowledge of life, composed of the word ayus (life) and veda (knowledge).74 Ayurvedic medicine does not separate the health of the body from that of the mind and aims to restore the balance among all the components that reflect an individual’s health: care of organs, psyche and soul; and even the relationship the person has with the environment, relations with the family and with the world at large. For a healthy person, the purpose of Ayurvedic science is to pursue and achieve four objectives in their existence:

• dharma (achieving wellness through decorous living, including respect for justice and morality);

• artha (achieving a good standard of living, while respecting the rules of dharma);

• kama (the satisfaction of worldly desires, passion and love); and

• moksha (attainment of salvation and liberation from the cycle of birth and death acquired through consciousness of the existence of God).75

These objectives allow equilibrium to be found both for the inner self and with the environment, or better still, a balance between the macrocosm and the microcosm (the body), the latter reflected in the former. Disease is thought to be the result of a breach of this balance and Ayurveda, as a therapeutic science, recommends proper nutrition and yoga as supports to maintaining good health through inner peace, transcending the senses and releasing the bonds with matter.76

Human well-being relies on food and its digestion because the body grows and develops depending on how it is fed. Ayurveda places ample attention on food quality, properties of raw materials, and the processing triggered by agni, the body’s digestive fire. Foods, like everything existing in nature, have three qualities or gunas: sattvic (pure), rajasic (overexcited) and tamasic (rotten). Sattvic or pure foods are the best for eating correctly and they include fresh vegetables, fresh fruit, cereals, natural sweeteners, mother’s milk, butter, ghee, cold pressed oil and shoots. The Bhagavad Gita states that “those foods that enhance life, purity, strength, health, joy and happiness, which are tasty and oily, nutritious and pleasing, are dear to sattvic people” (XVII, 8). Only moderate use should be made of rajasic foods, which often have a spicy taste and include fermented foods, garlic, cheese, sugar, salt, coffee, chocolate, and very strong spices and herbs. The Bhagavad Gita also states that “bitter, acidic, salty, overly hot, pungent, dry or spicy foods are preferred by rajasic persons and generate pain, distress and sickness” (XVII, 9). Finally there is tamasic: damaged or improperly cooked foods, such as fried and frozen foods, and those treated with preservatives or microwaved. Tamasic foods also include mushrooms, meat, fish, onions, garlic and substances like alcohol and tobacco, all of which should be avoided.77 The Bhagavad Gita reads: “the tamasic will prefer food that is tasteless and rotten, which is unclean waste” (XVII, 10).

It is also important to appraise the taste of foods, namely their rasa, because different flavour nuances have different effects on the human body and, not least of all, on the mood of those who consume them.78 Ayurveda recommends taking care of the body by eating regularly and taking daily exercise. It is important to wake up early, to thank the Lord, empty the bowels so as to start a new day without the debris of the day before. Equally it is necessary to clean all parts of the body properly, with particular attention to the “nine gates”. The body is seen as a temple with nine entrances to the outside world: eyes (netra), nose (neti), ears (karna), mouth (mansuya), vagina (yoni), penis (lingam), anus (mula), navel (nabi) and the top of the head (brahmarandra). Massage and meditation are integral to this care as these practices help ward off negative moods so as to avoid anger, envy, greed, jealousy and harming oneself and others.79

What seem to be just rules for proper nutrition and lifestyle actually have a close bearing on the sphere of the sacred. Food is anna, the first Sanskrit word to designate a Brahmin. Everything in the universe is food and interior growth depends on the ability to eat and digest the food that is our lives.80 In particular, the choice of foods to combine tends to avoid the juxtaposition of principles that lack equilibrium and so would lead to inner disharmony if consumed.81 Those who want to keep good karma will avoid combining animal food (obtained by the act of violence intrinsic to slaughter) with vegetables (a spontaneous gift of nature).82 The rule of food harmony tries to achieve an inner balance intended to come close to the harmony of the universe. So, the purer the food is, the more the body acquires its characteristics, enhancing spiritual elevation. This is because foods are not a simple matter: they are a vehicle of subtle information, energies, manifestations of the primordial vibrating energy called Prana.83 Thus, when people eat, they take the Prana contained in the food and circulate it around the body through seven energy centres called chakras (specifically: muladhara, swadhisthana, manipura, anahata, visshuddhi, ajna and sahasrara), which govern various functions and organs. When Prana enters a chakra through food, organs come into contact with it and it takes a specific name, becoming apana at the level of the first chakra, controlling excreta; at the second chakra it is viana, which regulates blood circulation; as samana at the third chakra it regulates the digestive process; prana (without a capital) at the level of the heart chakra, controls the respiratory process; lastly there is the fifth chakra, udana, which controls the diaphragm.84

Action (or non-action) that arises from the fermentation of pure foods within the human belly is thought to bring vital thought processes closer to the cosmos and to the divine. In this way, foods become mediators that can absorb and convey the subtle energies that connect human beings. As mediators they permit the transfer and the “initiatory succession” of energies that offer the eater the possibility of being grafted, the Vedas say, into “cosmic light”. Consequently, the meal is a rite, a moment of exploration, of learning, but also of intense rapport with the other, the Absolute, an act that allows their “realisation in existing and in strength”.85 But there is no dichotomy between what is eaten and the eater because, as Mario Bacchiega says, “everything has been eaten” and “the eater and the eaten are the same thing […] really there is neither eaten nor eater”.86 The extraordinary mystical chant: “I am food, I am food, I who am food, I eat the eater of the food!” expresses the overcoming of the tension between knowledge and love in the symbol of food, because here human and divine action need each other. In this cosmic metabolism, profound unity is achieved: eat the other and be food for the other.87

Food is not only limited to the sphere of the sacred, however: it has an aesthetic, popular aspect that reflects daily life. Indians generally do not possess an in-depth knowledge of all expressions and characteristics that food plays in the culture and spirituality of India, but they internalise the guidelines of nutrition (including the beliefs, functions and traditions related to it) from the families in which they are raised. Often this is represented by the daily rapport that women have with the handling of food and with children. So even if haute cuisine in traditional patriarchal society is the expression of a public and ritual act and the domain of male Brahmins, it is usually the woman who is the leading player in cooking and preparing meals.88

Food in women’s everyday lives

Any discussion involving food must take into account the role of women in the preparation of meals and the close bond between women and the act of cooking. Indian women today enjoy a wide scope of action, but traditionally their place has always been in the home, particularly in the kitchen, where the family shrine was, and still is, placed. The kitchen is the heart of the Hindu home, which is kept as far as possible from sources of contamination such as sleeping quarters or the room where visitors are received. Before entering the kitchen, the cook must clean herself of any contamination that may come from the outside and change clothes, because the purpose of the food preparation process is not only to produce foods that keep the body alive, but to merge the cultural properties of the food transformed by the cooking process itself with those of the people who eat it.89

The woman plays a vital role in cooking for the family and providing food for the gods. This act requires knowledge of the preferences of the deities and those preferences, with relevant recipes, are handed down from mother to daughter. Usually, however, the offering to the gods, called prasad, includes rice boiled in milk, small cakes, a stick of incense and a garland of flowers. After the god has been fed, the leftovers are redistributed among family members. As mentioned previously, the cow, and cattle in general, have a crucial importance in the Hindu religion and in Indian culture. Women are often privileged custodians who wash cows and decorate them for religious ceremonies and festivals. Fresh cow’s milk is used to wash the statues in family temples, while dry dung is used as fuel for cooking (especially in the villages) and to clean the floors of the house and the kitchen. The kitchen floor is used as a table to be set before sitting down for meals. It is always the women who bring the meal to their families and while serving they “give”. Even in modern times, women–especially the older generation–in the villages do not eat with the family, but only after everyone else has finished.

Cooking is not limited to the scope of the food but expresses a wider range of meanings: a woman’s inner heat (a force known as shakti) is said to be ten times higher than that of a man. David Smith writes “it is this force that enables them to give birth, to as it were cook the foetus in the same way as they cook the food that maintains the life of the family they have given birth to. The husband is born again in the son that originates from his wife’s womb. Husband and children are all given life and physical sustenance by the wife”.90 The birth of a child, in particular a son, confirms the woman in her role within the family and through generational continuity she saves her husband from the condition of being a man without descendants. The son will ensure nourishment to his father’s spirit after his death. The woman also renews the act of cooking in every act of sexual intercourse because through her heat she “cooks” the male member.

This symbolism, related to women’s bodies, is not immune to the pure/impure distinction that regulates certain times.91 During the menstrual cycle, for example, women—especially of the higher castes—do not cook or enter the temple.92 The mother’s preference for pure foods ensures her offspring remain healthy in line with the dietary requirements laid down by dharma. Those individuals who are fed pure foods (mainly vegetables) are reborn in a high social status; conversely, those who have eaten animal flesh or pursued less discriminating eating habits, will be reborn in a lower varna.93

This is in no way an exhaustive description of the relationship between the female body and cooking in the broadest sense, but it is useful for understanding the context in which women once operated, and still do, although they now enjoy a freedom that releases them from some traditional domestic constraints, especially if they live in large cities and are relatively wealthy. These constraints do, however, fall upon the work of women of more humble extraction, who perform domestic services in middle-class houses (from cleaning to managing the kitchen). Sociologist Barbara Ehrenreich and anthropologist Arlie Russell Hochschild have shown how, in the battle for equality and the right to self-determination, feminism often hides a form of exploitation carried out by richer, perhaps career-oriented women, towards less-educated or poorer women. Rather than men taking on traditional female tasks as more women head to the workplace, domestic duties are offloaded onto other women.94

The caste hierarchy of food

Food transactions are not only relevant in gender differences; McKim Marriott believes that they could be a primary device for explaining caste organisation.95 The food reflects caste differences through a series of rules with which diners must comply scrupulously to avoid contacts that could render both the food and people who are eating impure. Written rules list the different types of impurities (for example, the moment of birth and death, or the performance of certain manual tasks that involve contact with unclean elements), but generally the act of eating is a far more vulnerable time than others and should be approached with great care. Food rules that affect ordinary meal consumption presume an attention to ingredients (vegetable foods are preferable to animal products); to cooking (preferring food fried in ghee or clarified butter to boiling); place (the eating place should be as far away as possible from possible sources of contamination); cookware (preferring the use of copper or aluminium pans to terracotta because they can be washed with greater ease and do not accumulate residues in porous cavities). Every gesture during the meal must be controlled to avoid making the food inedible. For example, vicinity to lower caste individuals should be avoided, as should the presence of animals or contact with human saliva. Despite being produced by the body, saliva is regarded as “alien” to it because it is a vehicle of potentially harmful substances, even though it is also synonymous with deep acceptance and belonging to the family group.

By tradition, and especially in the first phase of the marriage, a wife eats her husband’s and in-laws’ leftovers so as to be integrated into the family. A parent may consume their child’s leftovers. Sharing a meal is a family action, because the family eats “from the same hearth”.96 If a member breaks a caste rule (for example, by offending a family member), they will not be accepted at family lunches and reintegration is symbolised by a party in which the offended person offers food to the offending person. This gesture allows all other members to reintegrate the offender into the eating circle.97

The rules are stricter for the high castes, in particular for the Brahmins, and impose a series of precautions that do not leave much room for individual freedom.98 For Brahmins in particular, a vegetarian diet is strictly necessary to maintain caste purity and foods should always be placed safely in sealed containers to avoid being contaminated by an outsider’s impure hands. This code of conduct was already noted in the eleventh century by the Arab intellectual Al-Biruni. He describes relations between Hindus and Muslims:

all their fanaticism is directed against those who do not belong to them—against all foreigners. They call them mleccha, i.e. impure, and forbid having any connection with them, by intermarriage or by any other kind of relationship, or by sitting, eating and drinking with them, because thereby, they think they would be polluted. They consider as impure anything that touches the fire and the water of a foreigner; and no household can exist without these two elements. Besides, they never desire that a thing which once has been polluted should be purified and thus recovered […].99

The excerpt highlights how the concept of purity was an element of identification by foreign observers. Food preparation and habits were signals that revealed caste hierarchy and Hindu culture more broadly.

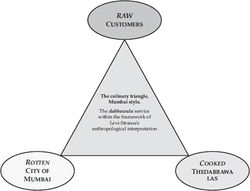

A 1970s study led by Stanley Freed in Shanti Nagar, a village in northern India, showed how the caste hierarchy was based on an asymmetric exchange of food and water. Caste classification is apparent in understanding from whom food can and cannot be accepted. The giver is in a hierarchically superior position to the receiver. The asymmetry of the exchange makes use of cooking techniques. For example a pakka food, cooked in clarified butter, can be taken by members of higher castes; conversely a kaccha food cannot.100 Kaccha and pakka mean literally “raw” and “cooked” but the derived sense has a very extensive application and indicates, on one hand, insecurity and imperfection, and on the other soundness and perfection (a notion that contains a hierarchical nuance). The distinction between these two stages is achieved by the use of ghee. In Brahmanic India, sacrificial food is counterpoised to non-sacrificial food, and the former is always cooked, pakka, protected and sanctified by the ghee used for frying it. Pakka food is less exposed to contamination while kaccha food is more fragile and corruptible.

Modern meaning intends both as cooked food but using different techniques: Kaccha foods are cooked in water while pakka food is essentially fried in ghee and prepared to be consumed outside the home. The cooking sequence is critical in designating one or other type of food. The same principle can be found for water, which retains its purity when kept in a brass jug and can be accepted by members of higher castes when offered by members of lower castes; when it comes from earthenware jugs this is not possible.101 Food thus becomes the expression of a refined taxonomy, functional in a classification of the universe that reflects natural elements and social orders consistent with the construction of a collective sense. Chaos is opposed by a system of linkages between nature and society, abstractions or cultures, in which humans and worldly objects belong to each other according to a logic of obedience to certain criteria.102

Food and the metropolis

In recent years there have been significant transformations in food culture. In the big cities and in diasporic contexts, the caste system softens into a more fluid stratification where surviving inequalities and differences are based on property, power and prestige. Food also reflects these transformations and, indeed, the current scenario of a metropolis like Mumbai is characterised by a public space dominated by an impressive variety of food, including restaurants that serve any type of food and street vendors offering cheap lunches from their stalls, to eat while standing.103 The food sold reflects Mumbai’s cultural habits and traditions, for instance distinguishing between “hot” and “cold” food, depending on the season it is offered. The distinction does not refer to the temperature of the food or its spiciness, but to the effects the foods have on the body. During the main festivities the dishes offered by street vendors are appropriate to the circumstances and are a good alternative to eating lunch out. Vendors often use ghee instead of water to make food pakka (safer). According to Mina Thakur’s research on street food in the city of Guwahati, many customers seek Brahmin vendors to be sure they are buying unpolluted food, or they look for vendors of their own caste offering traditional dishes.104

In Mumbai, the debate about the regulation of street vendors can get very heated. A recent investigation by Jonathan Shapiro Anjaria noted complaints from city associations about vendors selling street food. These vendors are seen as the symbol of a metropolitan space that escapes the control of the authorities and of the flow of migrants arriving in Mumbai. Often the protests are based on two main elements—language and religion—that reflect the offer of non-vegetarian foods from non-Hindu sellers. In deciding who can sell food on Mumbai territory, the city pursues a nativist policy and distinguishes foods that may or may not be cooked on public land.105 Often the younger generation call this “junk food”, using a common English expression that denotes readily available, cheap food of poor quality. It refers to what students eat for lunch at street stalls, like bara pav (a type of bun, cut in half and stuffed with a red or green chilli sauce, potatoes and spices), or pav bhaji (a sandwich accompanied by a mixture of vegetables).

The diversified food on offer reflects the demands of a city where new social classes are stratifying and seeking a variety of choices that were unknown a few years ago. Mumbai has undergone a transformation in recent years that entails the growing presence of middle-class people used to eating out in the evening. It is a relatively recent phenomenon, for previously only people with a relatively low income were in the habit of eating outside their homes. The indoor restaurant, different from street food vendors, reflects and promotes a series of changes in public and private contemporary Indian life induced by increased wages and the entry of middle-class women into the working world. These changes were followed by new experiences of conviviality and socialisation, with the consequent modification to spaces, places, and relationships inside the kitchen.

While there are increasing numbers of trendy new restaurants around the city (with many Italian newcomers), multicultural food is not a recent phenomenon in India. There has been a continuous rotation of renewed migratory waves that bring disparate influences to the city’s flavours: there is a mix of large colonial Bombay hotels used by the British; the already mentioned khanawals; Irani cafés, an important Bombay institution now facing extinction; Western or European-inspired restaurants; and dhabas (eateries offering traditional food). These venues offer cuisine typical of the various regions of northern India: Kashmiri; Punjabi; Pahari; Marwari; Rajastani; Lucknawi.