8. From Collaboration to Conflict: The Racial Survey of 1923-1929

In 1920, Halfdan Bryn and the Schreiners began to collaborate on a large, state-funded anthropological survey of the Norwegian population. The project highlighted many of the scientific and ideological differences between them, and after an initial period of amicable cooperation, their joint undertaking ended in deep and insoluble conflict. This chapter charts the path their relationship took from collaboration to conflict: their initial accord, the causes of their disagreements and the factors that led to the eventual breakdown in their working partnership.

Launching the project

As mentioned in chapter 3, Guldberg had already floated the idea of a national racial survey in 1904. Kristian Emil Schreiner and Bryn, together with the head of the Army Medical Service, General Hans Daae, took up the idea again during World War I. On 17 May 1919, Bryn received a letter from Herman Lundborg suggesting that a joint Scandinavian survey be launched. Bryn seized this opportunity to finally bring the Norwegian plans to fruition and contacted Kristian Emil, who welcomed the idea and convinced the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters to help with organisation and funding.334

In his application to the Academy, Schreiner argued that the project was important ‘by virtue of its significance and Scandinavian nature’,335 and he used the opportunity to give an account of Bryn’s recent anthropological investigations. Schreiner later reported to Bryn that this report had aroused positive interest at the meeting.336 Beyond this, there is nothing in the minutes of the Academy or in the correspondence between Bryn and Schreiner to suggest that the project provoked much discussion at the Academy meeting. It is likely that the Academy’s unanimous decision to support it was taken without any questioning of the project’s legitimacy or fruitfulness. The racial survey was added to the Academy’s budget for the next year and was later approved by the Norwegian Parliament without discussion.337 Judging from Schreiner’s and Bryn’s arguments, and the response from the Academy and Parliament, we may conclude that a significant amount of money was granted to this ambituous and costly project because of its ‘Scandinavian character’ and ‘its significance’. There is no precise explanation, however, of why the project was considered significant.

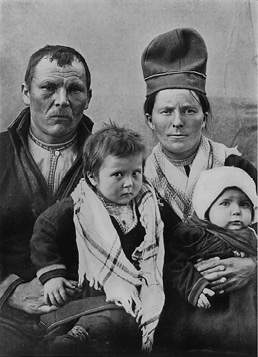

By the time the funds were made available, everything was in place to begin the collection of data. The plans had been approved by the Defence Department, measuring tools had been purchased and data sheets had been printed. Dr Johan Brun and the Anatomy Demonstrator Georg Wåler had been trained in anthropometric techniques so that they could assist Bryn and Schreiner. The measurements were conducted during the summers of 1920 and 1921, and those surveyed included all Norwegian recruits turning 21 in the designated year. The data were organised geographically according to where the recruits’ parents were born. Thus, according to Schreiner, the survey showed the distribution of the population in the year 1869, not 1920, and permitted extrapolation to the population distribution before industrialisation and mass migration had disrupted the traditional patterns of settlement. In addition to the survey of army recruits, more detailed studies were carried out in selected districts. The populations of Hålandsdal and Eidfjord in Hordaland, as well as Valle in Setesdal were surveyed, as these places were thought to be the ancestral homelands of the long-skulled blond race. Likewise, Luster and Hafslo in Sogn were studied since they were considered to be the core areas of inhabitation by the dark short skulls.338 Lastly, the Sea Sami population of Hellemo in the community of Tysfjord in Nordland was investigated (see Figs. 17 and 18). These regional studies were meant to supplement the data from the survey of the recruits, for they also recorded family relationships and included children, youths and women.339

The collection of data seems to have unfolded according to plan, and collaboration on the analysis of the data worked well until the middle of the decade. Although disagreements arose during the project on a number of methodological and theoretical questions, both Halfdan Bryn and the Schreiners recognised the need to respect each other’s professional position. They regarded each other’s points of view as scientifically valid and agreed that potential areas of conflict could be resolved through scientific research.

Towards the end of the 1920s, however, it became clear that research alone would not suffice to resolve their disagreements. Professional and political debates on the question of race had become progressively more polarised, and it was increasingly evident that methodological and theoretical divisions were tied to ideological oppositions. The final result was the breakdown of collaboration between the Norwegian anthropologists; a conflict over scientific legitimacy replaced their scholarly conversation.

Fig. 17 A family from the Sami community of Tysfjord. Both the survey of recruits and the studies of localities made use of portraits and anthropological measurements.

Fig. 18 ‘East Baltic’ women from Norway. Although the community of Valle was studied extensively because it was regarded as the untouched heartland of the Nordic race, it turned out that a large number of its women displayed anthropological traits characteristic of the so-called East Baltic race.

Descriptive anthropometry?

Before the survey began, Halfdan Bryn raised the issue of mapping psychological characteristics. He discussed the issue with Lundborg, who had previously dealt with the heritability of traits such as ‘endowment, temperament and character’ in his research. Lundborg replied that he would not advise the recording of psychological traits, as such data would be unreliable unless long-term observations could be carried out. If one was to collect information on psychological characteristics, he argued, one should limit it to clear cases of psychological superiority or inferiority.340 Bryn also brought the idea to Kristian Emil Schreiner, who categorically refused to consider it. According to Schreiner, Lundborg’s use of concepts such as ‘endowment’ was a scam; such descriptions of psychological characteristics were only of interest to the researcher himself.341 Schreiner got his way: the survey was restricted to the measurement of somatic characteristics.

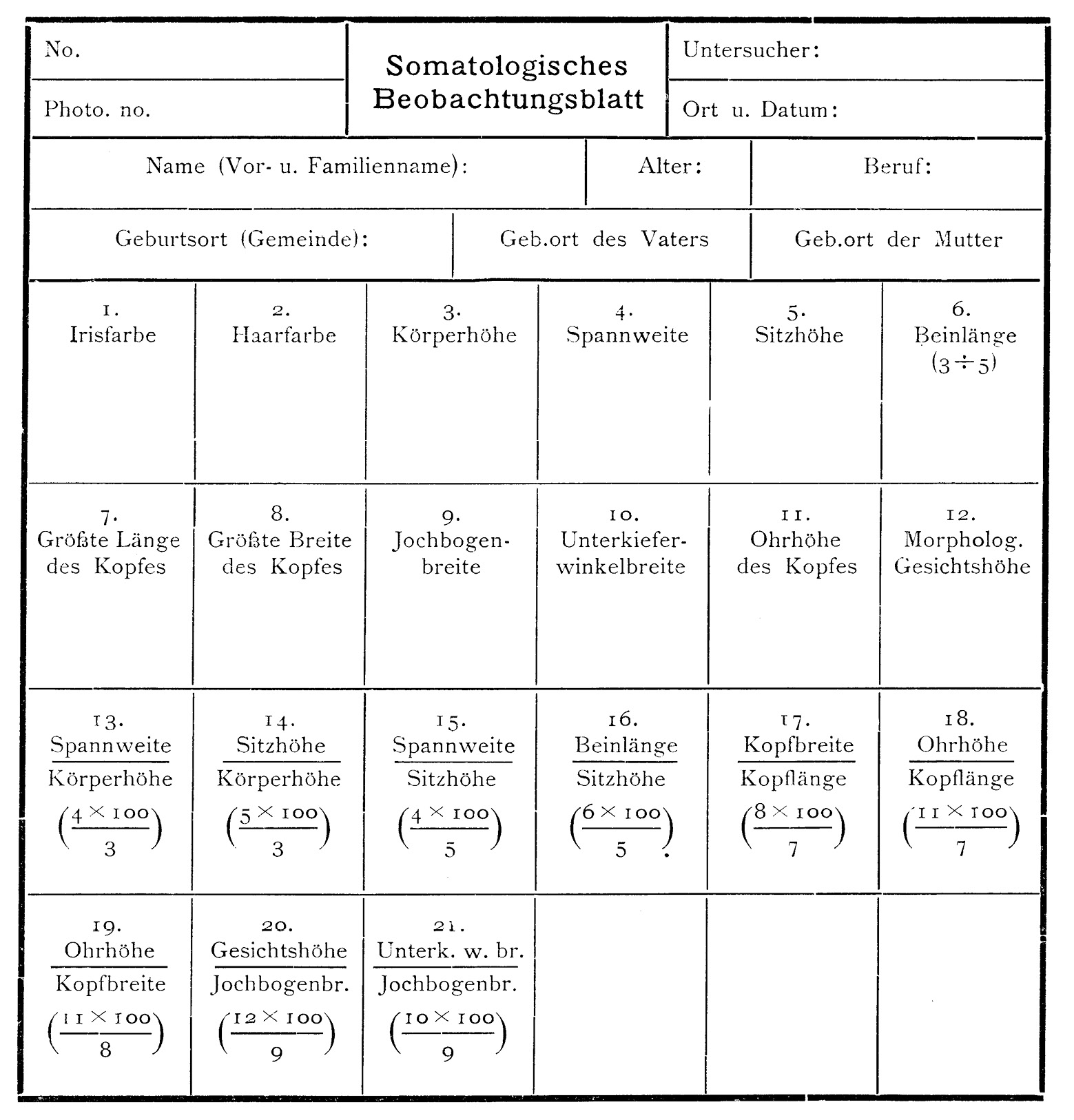

Following the model applied by Gustav Retzius and Carl Fürst in their Anthropologia suecica,342 the scientists prepared a printed form for recording each recruit's somatic data (see Fig. 20). Their discussion of which elements to include in the form and how to make the measurements mainly revolved around the practical feasibility of the undertaking. In addition, they agreed upon the importance of sticking to international standards that would render the data compatible with, and therefore comparable to, data from similar studies elsewhere. The anthropological ‘relevance’ of certain traits was repeatedly discussed, but the premises of such ‘relevance’ were never explicitly formulated. It seems that Bryn and the Schreiners designed the project without explicitly considering the underlying theories upon which it was to be based.343

Fig. 19 The form used to survey recruits.

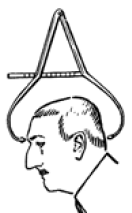

The final list of characteristics to be covered in the survey included body height, arm span, leg length, angle of the lower jaw, length and width of the head, face length, eye colour, hair colour and ear position (see Fig. 19). These measurements would then be used to calculate size ratios; for example, the length and width of the head was used to calculate the cephalic index, according to which the material was classified into seven further categories ranging from ultrabrachycephalic (extremely short skull) to ultradolichocephalic (extremely long skull). The length of the face and the width of the chin would be employed to calculate the so-called morphologic face index. This, in turn, formed the basis of five groups in a scale from hyperuryprosopy (extremely short face) to hyperleptoprosopy (extremely long face).344

Rudolf Martin’s Lehrbuch der Anthropologie was the main point of reference for the discussion of which traits to include in the study.345 In his textbook, Martin emphasised that the classificatory relevance of the various traits was unknown and that the collection of data should have a purely descriptive aim. It is reasonable to argue, however, that the apparatus of measuring techniques that Martin prescribed in his Lehrbuch was mainly defined by the anthropological research tradition, and was thus the product of the theoretical debates and assumptions that had influenced the discipline throughout its history. A key example is the cephalic index. Invented by Anders Retzius in the 1840s and grounded in specific theories of brain anatomy, it later became a standard tool in the anthropometric toolbox of anthropologists, although the rationale for using it shifted over the years and remained a controversial topic.

The ‘traits’ that Bryn and the Schreiners chose to scrutinise in their survey were largely determined by the anthropological research tradition as it was expounded in Martin’s textbook. A long history of theoretical reasoning and debate lay behind the use of these traits as racial markers, but Kristian Emil and Bryn did not initially discuss the implications: data gathering was considered a simple descriptive undertaking. However, when the statistical processing of the data began, theoretical and methodological problems arose that gave rise to heated discussions.

Fig. 20 Various kinds of calipers for the measurement of various parts of the body.

A scholarly debate on the hereditability of the cephalic index

The debate had already begun by the end of the first summer of fieldwork. In 1920-1921, Bryn performed a Mendelian analysis of the heritability of skull shape and eye colour based on data collected from the local communities of Selbu and Tydalen, in the southeastern region of Trøndelag. He concluded that these peoples consisted of three original racial types, each characterised by a typical skull shape: the Alpine were dolichocephalic, the Nordic mesodolichocephalic and the Cro-Magnon brachycephalic. According to Bryn, each skull shape was inherited in Mendelian fashion. It was not the cephalic indices themselves that were inherited, however, but rather their tendency to vary around a central value. Therefore, one of the key premises of Bryn’s analysis was that there was a great degree of variability within each inheritable skull form.346

In a letter to Bryn dated 2nd December 1920, Alette Schreiner praised his study as the best that had ever been conducted on the inheritability of skull shapes. However, she also pointed out that certain questions remained unanswered, and she doubted the existence of three inheritable skull shapes with such high variability as proposed by Bryn. She suggested that the relationship between inherited Mendelian traits and measurable characteristics was more complex than Bryn had shown: what appeared to be a simple morphological trait might derive from a complicated interaction of numerous Mendelian factors.347 In a letter to Bryn two weeks later, she wrote that it was not only likely that head shape was ‘controlled by several wholly or partly independent [Mendelian] factors’, but that it could be influenced by environmental and cultural conditions as well. She argued that the shape of the skull could be related to a number of factors including body height, sex, the overall size of the brain, the relative size of the different parts of the brain, intellectual capacity and individual psychological development in childhood and youth.348

Alette’s arguments touched on the basic premise of Halfdan Bryn’s research. He believed he had demonstrated that certain racial characteristics, say dolicocephaly and height, tended to coincide among present-day Norwegians. Bryn took this observation as proof of the past existence of a race of tall, long-skulled inhabitants in the country. Such a conclusion was predicated on the independent heritability of specific racial characteristics. However, if traits such as dolichocephaly were genetically or physiologically related to tallness, Bryn’s conclusions would be invalidated. This was precisely what Alette hinted at in her letter.

She went a step further and suggested that perhaps the individual’s psychological development in childhood might also affect the size of the brain and thus, indirectly, the shape of the skull. Alette concluded her letter with a postscript asking Bryn to imagine the possibility that a cultured environment and education could affect the brain’s development and lead to a more brachycephalic skull shape.349 Thus, her letter criticised not only Bryn’s genetic study of the shape of the head, but the very foundation upon which his anthropological investigations were based. Her concluding remark turned the entire theory of a superior, long-skulled race on its head. Could it be possible that the short-skulled, and not the long-skulled, peoples represented the high point of evolution?

In 1923, the first publication based on the national survey appeared in the Dutch journal Genetica. It was a study, by Alette Schreiner, of the heritability of skull shapes and was based on the local case studies that had been carried out as supplements to the survey of conscripts. In the article Alette systematically criticised the use of the cephalic index as a genetic marker. She reviewed the few existing studies on the subject, including the one by Halfdan Bryn, and launched a devastating attack against Bryn’s conclusion that brachycephaly, mesocephaly and dolichocephaly were simple traits inherited in a Mendelian fashion.350 Alette argued that Bryn had oversimplified the issue by attributing a range of variability to the three heritable head types so wide as to make it impossible to distinguish between extreme variants of each type. Bryn’s data, she continued, instead pointed to the same conclusion as hers, namely that head shape was controlled by a larger number of Mendelian factors. In addition, she suggested that these factors should not be considered as absolutely determinative, but rather as inherited tendencies that were modified by external and internal conditions during the bodily development of the individual.

In Alette Schreiner’s opinion, Broca and other nineteenth-century anthropologists had overestimated the importance of living conditions and lifestyle on skull development. Contemporary anthropology, however, had gone too far in the opposite direction, and a thorough analysis of skull-shape heritability could not be made until all the complex issues concerning the ontogenesis of the brain and skull had been explored.351 Furthermore, she claimed that the causes of skull length and width were so complex that the cephalic index, the most important trait studied by anthropologists, was useless as a tool to explore the issues of heritability and race. The popularity of the cephalic index was due not to its scientific value, but to the fact that it had engendered a classification system of seductive simplicity. People had forgotten that it was actually an artificially constructed concept.352

At the end of the article, she raised the question of why the European population had become increasingly short-skulled since the Iron Age. This question had first been asked and discussed in the latter part of the nineteenth century, when anthropologists became aware of a discrepancy between the overwhelmingly dolichocephalic skulls from South-German Iron Age burial mounds and the overwhelmingly brachycephalic character of the present-day South-German population. There were two main and competing explanations for the phenomenon. Some argued that Central Europe had been the home of an original, short-skulled Slavic population that had survived when the Germanics invaded. They had adopted a Germanic language and mixed with the invaders. Over the centuries, the brachycephalic part of the population had procreated at a higher rate than the dolichocephalics and ended up as the dominant element. Lapouge was among those who advocated this view. The other explanation was that the cephalic index of the original dolichocephalic population had changed as the populaton became more civilised. The growth of the brain led to a more globular skull shape, and thus to a higher cephalic index.353 It may not be surprising that Bryn was in favour of the former explanation, while Alette supported the latter. Cultural development had led to a rounder skull shape, she argued, adding that there was certainly no reason to interpret this trend towards brachycephalisation as a sign of ‘degeneration’.354

Alette disagreed with Bryn on key scientific questions and criticised his methodology, but this does not mean she questioned his scientific credentials or regarded him as a pseudo-scientist. In the letter of 1921 in which she suggested that brachycephaly could be sign of intellectual superiority, she also wrote that Norwegian anthropology would benefit if Bryn moved to the capital. ‘We are getting nothing done, and Kristian is sick and tired at the moment. It would be helpful for us to talk to you in peace sometime'. Elsewhere in the same letter she wrote in general terms about the need for scientists to work together and talk with each other: ‘[...] one should make use of each other as much as possible; that is what can help us reach the truth’.355

She went on to write of their common acquaintance Andreas Hansen, about whom she had ambivalent feelings. ‘Though he may be the most gifted of all of us’, she still considered him to be ‘rather superficial and dogmatic’. She admitted to being somewhat impressed by him, but she also referred to Ole Solberg's criticism of Hansen for holding ‘muddled ideas’, for lacking ‘thorough expertise and education’ and for having no respect for educated experts. The message of Alette’s letter seems to be that scientific progress depends upon collaboration and open debate based on mutual respect between people with the proper ‘expertise and education’. Her confident and friendly tone suggests that despite their differences, she considered Bryn among those with ‘knowledge and education’. On the other hand, her sceptical attitude to Hansen’s scientific credibility could be taken as an indirect critique of Bryn, since Hansen was Bryn’s collaborator and the original source of many of Bryn’s scientific ideas.

The relationship between Kristian Emil Schreiner and Halfdan Bryn seems to have been good until the mid-1920s. All evidence suggests that the Kristiania professor considered the Trondheim army doctor a valuable colleague. Following World War I, Schreiner used his academic network and influence in the capital to provide research funding for the provincial Bryn, helping him to obtain a grant from the Nansen Foundation and supporting the publication of his articles in the journal of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters. He even let Bryn use the Department of Anatomy’s anthropometric measuring tools. As late as 1924, Bryn still received letters signed, ‘your devoted Kristian Emil Schreiner, with best regards from my wife’.356

From collaboration to conflict

The clear scientific and ideological differences between Bryn and the two Schreiners had direct implications for their project. Alette Schreiner used data from the studies to support her critique of Bryn’s ideas on the heritability of skull shapes and to refute key elements of the theory upon which Bryn based both his research methods and his racial ideology. Nevertheless, these differences do not appear to have been an obstacle to fruitful collaboration until the mid-1920s. Both parties considered their disagreements to be scientific matters that could and should be solved with the help of scientific research and scholarly debate. The project was severely delayed, however, and only completed in 1929. By then, their scholarly communication had come to a halt, and the efforts to analyse and publish the data of the conscript survey had led to an intense quarrel, both professional and personal, in which the scientific credibility of the participants was at stake.

During the 1920s, the Department of Anatomy was reorganised and the number of students increased. Kristian Emil Schreiner began to feel burdened by his duties as head of the department. In 1921 he suffered a bout of depression that required hospitalisation, and in 1924 Georg Wåler, Schreiner’s co-worker at the department, fell ill as well. This meant that their analysis of the survey data had to be temporarily abandoned.357 Not only was Schreiner’s research set back, he was also slow to respond to letters from Bryn, who was in Trondheim working on his part of the project. Despite this, Bryn managed to complete the analysis of data from eastern Norway and to publish it in 1925 as part of the proceedings of the Norwegian Academy of Sciences and Letters in a volume entitled Antropologia Norvegica I. Moreover, the Swedish survey was also completed long before Schreiner had finished his part of the project. Bryn was in fact hired by the Institute for Racial Biology in Uppsala to help conclude The Racial Character of the Swedish Nation, which was published in 1926.358 This work received international attention as one of the most comprehensive studies of its kind and was published a year later in German as well as in a Swedish-language short version.359

Following the Swedish publication, Schreiner wrote to his Swedish friend and colleague Carl M. Fürst: ‘Hopefully it will not be long before our survey will see the light of day. It will not be anything as grand as Lundborg’s, but just a modest affair that can provide a basis for further research’.360 Schreiner had toned down his expectations because the data analysis had run into a number of time-consuming problems. Additional money had to be requested from a government research fund to complete the statistical analyses.361 The technical problems that caused the delay resulted partly from Halfdan Bryn’s sloppy work and partly from scientific disagreements between Schreiner and Bryn. This finally resulted in open conflict. Early in 1928, Schreiner wrote a letter to Bryn arguing that the figures on arm span had to be omitted from the final publication as he had discovered systematic differences between the figures from the regions surveyed by Bryn and the rest of the study. He pointed out further technical errors in Bryn’s work, including trivial mathematical errors in several tables. The errors had multiplied throughout the analyses and led to a lot of extra work. Schreiner suggested that the scope of the project should be reduced, but he still hoped that ‘despite all its imperfections,’ it would present an interesting overview and stimulate further research. He also suggested replacing the planned concluding chapter with a summary written by himself.362

Bryn was highly provoked by Schreiner’s proposal and drafted two replies. In one of them, he wrote: ‘To be honest, I find it hard to reply to your last letter, as I believe you deliberately tried to offend me’. In the second, he wrote: ‘When we started this huge undertaking at my suggestion in 1919, it was on the explicit assumption that we would stand on an equal footing. There would not be a superior and a subordinate’.363 Schreiner replied that he had not intended to deprive Bryn of any credit, and said he would withdraw the suggestion if Bryn felt that he was being bullied. He wrote that he had made the suggestion because he ‘considered collaboration—in the full sense of the word—as not practicable, both because we lack the opportunity to meet to talk things over, and because we have very different views on many issues’.364

The dispute ended with the work being published with neither a summary nor a conclusion as a final chapter, and with a title altered from Antropologia Norvegica to the less ambitious Die Somatologie der Norweger (see Figs. 21 and 22). The additional work had overrun the budget, which meant that Bryn and Schreiner had to exclude some of the data as well as cover some of the additional costs out of their own pockets.

Bryn and Schreiner assessed the conflict quite differently. Bryn, who had already published his conclusions in Antropologia Norvegica I, was both aggrieved and angered by his colleague's criticism. A barrage of letters followed in which Schreiner—in polite terms—accused Bryn of negligence and professional incompetence, while Bryn—in less diplomatic terms—accused Schreiner of bullying him and of trying to take control of the project and steal credit for the work. Both interpretations of the dispute seem reasonable, but the fundamental explaination for the breakdown of their cooperation was that, technical errors apart, they did not agree on the interpretation of the data and the conclusion of the study.

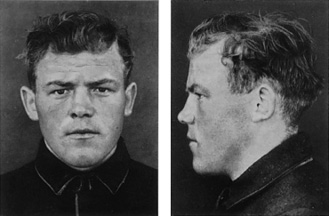

Fig. 21 Alpine racial type depicted in Kristian Emil Schreiner, Bidrag til Rogalands Antropologi (1941). According to Schreiner, this man from Ryfylke was a textbook example of a dark short skull belonging to the Alpine race.

Fig. 22 A pure or mixed racial type? According to Kristian Emil Schreiner, this recruit was a typical representative of the blond brachycephalic population of southwestern Norway. Schreiner dismissed Hansen’s description of these people as mixed-race, proposing instead that they represented a local instance of the ‘East Baltic race’, an ethnicity otherwise dominant in Russia and Finland.

A dispute over the classification of eye colour and hair colour

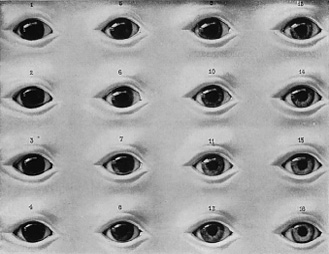

During the years of collaboration, two themes increasingly marked the correspondence between Bryn and Schreiner: the question of the classification of eye colour and hair colour, and the applicability of arm span as a criterion for classification. Hair colour was recorded by comparing the recruit’s hair with a set of hair samples that had been developed by Eugen Fischer and were referred to as the ‘Fischer Haarfarbentafel’. This tool consisted of 26 bundles of cellulose fibres that had been coated with non-fading colours and fitted together like a handy little ‘palette’ (see Fig. 23b). The colours were supposed to be representative of every hair colour that existed within humankind. In Fischer’s system, each of the 26 colours had a number, the light colours taking high numbers and the dark low ones. The hair colour of the recruit was classified by correspondence with the different hair samples, and the numbers were noted on the registration form. Eye colour was classified in a similar way using a similar tool developed by Rudolf Martin, a ‘palette’ consisting of sixteen glass eyes (see Fig. 23a).

Fig. 23a Martin’s eye colour chart.

Fig. 23b Fischer’s hair colour palette.

But when the data were collected and ready to be analysed, it proved impossible to use the large number of categories that Martin and Fischer’s systems encompassed. The question was which categories should be merged. Eye colour was a major topic. Where was the boundary between brown and mottled eyes? In 1923 Schreiner wrote to Bryn: ‘I am not very fond of placing the distinction between 5 and 6, because many 6-eyes in my material from northern Norway undoubtedly contain more pigment than many 5-eyes from the west coast; it is only the concentration of the pupil in 6-eyes that gives them a lighter colour. For these reasons, I would prefer to set the limit for brown eyes at 6 (like Martin does)’.365

A similar problem appeared when the hair colours were to be grouped. The question was where the boundary should be drawn between brown and blond. According to Fischer, 7 was ‘light brown’ and 8 ‘dark blond’,366 and Schreiner argued in favour of this measurement. Bryn wanted to set the border between 6 and 7, however, defining ‘blond’ more broadly and brown more narrowly than Schreiner.367

This discussion continued until the book went to press. While preparations for printing were in full swing, Schreiner wrote to Bryn: ‘I am very surprised to see that you denote Martin 13 and 14 as dark blue. Martin himself describes 13 as light grey, which it actually is. Both Wåler and I have in our records classified the dark blue colour as 15’.368 The matter ended, however, with the adoption of Bryn’s definition of blue eyes.369

Bryn was internationally acknowledged for his research on the classification and inheritance of Norwegian eye types. By 1920, he had already published his first work on the topic in the journal of the Norwegian Medical Association and in the Swedish-based international journal Hereditas.370 Between 1923 and 1925 he did further research in this field, resulting in the extensive treatise On eye types in Norway and their heredity (Über die Augentypen in Norwegen und ihre Vererbungsverhältnisse). This was published by the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters in Oslo in 1926 and extensively cited in the second edition of Rudolf Martin’s textbook on anthropology, issued the same year.371

Why was Bryn so passionate about this subject? In his 1930 thesis Homo cæsius, he showed that the type of eyes which Martin had identified as nos. 13-14 appeared with particularly high frequency in the central Norwegian counties of Møre and Trøndelag, whereas there was a higher frequency of Martin-type nos. 15-16 in the southern Telemark and Agder counties. He also claimed that there was a strong correlation between Martin-type nos. 13-14 eye colour and Fischer-type nos. 6-19 hair colour, on the one hand, and between Martin-type nos. 15-16 eye colour and Fischer-type nos. 20-24 hair colour on the other.372 He argued that these correlations, taken together with some other evidence, indicated the existence of two variants of the Nordic race.

Bryn’s theory was based on Carl F. Larsen’s old claim that the typical inhabitants of Trøndelag had a slightly shorter skull shape and face than was typical for the Nordic race. Bryn had previously explained away Larsen’s Trønder type as the product of racial admixture. Now Bryn reinvented the Trønder type, not as a separate race, but as a variety of the Nordic race which he named Homo cæsius nidarosiensis, after Nidaros, the old Norse name for Trondheim. In light of this theory, Trøndelag no longer appeared to be the homeland of a ‘bastard population’, as Bryn had deemed it in his first anthropological thesis, but rather the centre of a separate branch of the Nordic race.

In the book Der nordische Mensch (The Nordic Man) and in articles in the German and Swedish journals Volk und Rasse (People and Race) and Ymer, Bryn described the presumed mental characteristics of the two variants of the Nordic race.373 This was based on input from people with local knowledge who had been asked to submit their descriptions of the mentality of people in the North-Trøndelag communities.

He compared their statements with Arbo’s descriptions of the typical mindset of the population in those eastern Norwegian districts dominated by the Nordic race. Bryn stressed that this survey was not scientific, but rather a representation of subjective assessments. He concluded nevertheless that the Trøndelag variety was just as intelligent as the eastern Norwegian variety, though they had a different temperament. The Trøndelag type, Homo cæsius nidarosiensis, might be a little bit slow, but he was also independent, upright and stubborn, as well as frugal, enlightened, politically interested, righteous, honest, sturdy and steady.374

Kristian Emil and Alette Schreiner put forward a different interpretation of the distinctive Trøndelag combination of racial traits. In her analysis of the data from northern Norway, Alette Schreiner maintained that the population in northern Trøndelag and the three northernmost counties was dominated by a specific phenotype, one characterised by a more spherically-shaped head and a longer body than those of the ordinary Nordic race.375 Alette Schreiner explained this deviation from the Nordic norm as the result both of racial mixing and of the influence of the environment, living conditions and cultural development: the more globular shape of the skull had to do with increased brain size. The base of the skull had not been able to expand to accommodate the growing brain, but the more flexible top of the skull could. Therefore, the classic Nordic long skull had over time developed a rounder shape, thereby altering the cephalic index. This process of change was partly due to the large body size of the population in northern Trøndelag, which called for a greater brain capacity. However, Alette also suggested that it was due to extensive brain growth during adolescence, which was stimulated by a high level of civilisation among the farmers around Trondheimsfjord, possessors of a high social standing since ancient times.376

Alette and Kristian Emil Schreiner also reintroduced the blond brachycephal in order to explain the ‘somatological’ peculiarity of the population of Trøndelag. In his contribution to Die Somatologie der Norweger, Kristian Emil described a blond, mesocephalic Trøndelag type with a high, vaulted cranium. He claimed that this combination of traits could not be explained as a mixture of dark, short-skulled and blond, long-skulled races. There also had to be an element of the blond, short-skulled East Baltic race in the population of Trøndelag.377

Race or environment?

When discussing the material from Trøndelag, Alette Schreiner and Halfdan Bryn drew on different sets of theories. Both partners based their reasoning on theoretical assumptions that were considered scientifically sound within their discipline. Nevertheless, it is clear that the different choices they made when attempting to explain the bodily characteristics of the Trønder population coincided with differences in their professional and ideological attitudes. Something similar was revealed in the discussions between Bryn and Kristian Emil about urban populations. When planning their survey of recruits, they saw the big towns differently than the rural districts. Since the main goal of the survey was to map a traditional settlement pattern, Bryn suggested that they concentrate on the countryside and let the populations of Oslo and Bergen be represented by a small sample of individuals with deep historical roots in the towns. Schreiner agreed that it was most important to study the rural areas, but maintained that contemporary data from Oslo and Bergen would be useful, since ongoing processes could be elucidated by comparing immigrants with native townspeople.378

Kristian Emil Schreiner's idea may have originated less from his interest in racial classification than from his interest in how the social and material environment affected physical growth. During World War I, he and Alette cooperated with the municipal medical officer Carl Schiøtz on an extensive survey of height and weight among schoolchildren in Oslo.379 The goal was to study how nutrition and living conditions influenced their physical development. Schreiner’s survey resembles similar German projects led by Rudolf Martin to study the effect of wartime food shortages on the physical development of children. Schreiner’s idea of comparing immigrants with established townspeople may have had to do with his interest in the health effects of differences in living conditions and lifestyles between urban and rural areas. If so, he shared this interest with Halfdan Bryn, who, as already noted, had a very pessimistic view of the effects of urban living.

Concern about the deteriorating effects of city life was widespread among contemporaries of Bryn and the Schreiners. This was rooted in an often harsh reality: overcrowding, disease and malnutrition among the urban poor were major problems. In public debates, however, these problems were often related to a general criticism of ‘modern’ society and a fear of cultural and biological degeneration. Conservative nationalism was frequently coupled with anti-urbanism. In addition, many eugenicists saw the city as an arena of racial decline. Eugen Fischer’s previously-quoted speech on anthropology and eugenics exemplifies this view. He maintained that the city tore apart families and social ties and led to racial mixing and degeneration. This type of thinking is an important background factor in the dispute that arose between Bryn and Kristian Emil Schreiner when they began analysing the data from Bergen and Oslo.

In both Antropologia Norvegica I and Die Somatologie der Norweger, Bryn claimed that the distribution of racial traits in the population of Oslo confirmed Otto Ammon’s law stating that the dynamic Nordic race had a nature-given tendency to migrate to the city.380 Bryn once again based his arguments on an analysis of the distribution of eye and hair colour, in addition to arm span, and on the assumed existence of a Homo cæsius nidarosiensis. Bryn’s theory of a Trøndelag variety of the Nordic race implied a correlation between dark blue eyes and short arm span. This combination of traits had its centre of radiation in Trøndelag, he maintained, and it could be followed like a broad stream through the eastern Norwegian valley of Gudbrandsdalen and all the way down to Oslo. Dark blue eyes and short arm span were also more common in Oslo than among the average national population, a fact Bryn explained by pointing to a great influx of Nordic racial elements into Oslo. The migration to the capital was a process of social selection, according to Bryn.381

Bryn ran into a major problem, however. The survey showed that the population of Oslo had a shorter average body height than the total national population. This did not fit well with the notion of Oslo as a stronghold of the tall Nordic race. Bryn resolved the difficulty by claiming that the high frequency of short-statured people was the product of bad living conditions in the capital, conditions which prevented inhabitants from fulfilling their racial potential. He pointed to the fact that newly-settled residents were taller than the native city-dwellers, and to a strong statistical relationship between social status and body length. Members of the higher social strata were in general taller than average, both because the Nordic race was overrepresented due to social selection and because good living conditions had allowed them to develop their full potential for bodily growth. Short body height among the lower strata, on the other hand, was due to bad living conditions.382 Bryn’s analysis implied that Oslo attracted the best racial elements, but offered unfavourable living conditions for its immigrants.

In his treatment of the data from Bergen, Kristian Emil argued against Bryn’s hypothesis. He asserted that the claim of a correlation between short arm span and dark blue eyes was unfounded, and pointed to the fact that the Bergen population also had a short average arm span, despite its racial composition being very different to Oslo's. Therefore, he reasoned, racial composition could not explain low average arm span. The explanation had to lie in the influence of the urban environment. An urban lifestyle led to weakened growth in muscles of the back and shoulders. Urban dwellers had narrow shoulders and therefore relatively short arm spans.383 Thus, while Bryn interpreted short arm span as indicative of short arms and as a characteristic racial trait of the Nordic race, Schreiner saw short arm span as indicative of narrow shoulders resulting from an urban lifestyle. Both these interpretations were based on data from the same survey, and they were published in different chapters of the same book. It is not surprising, then, that their authors had difficulty agreeing on the content of the concluding chapter.

Was Bryn an imposter?

Bryn’s interpretations of the data from the survey confirmed many of his preconceived ideas. Both his theory of Homo cæsius nidarosiensis and his analysis of the racial composition of the population of Oslo seem to have strengthened his growing faith in the gospel of the Nordic race. Moreover, Kristian Emil Schreiner was correct in accusing Bryn of inconsistency, calculation errors, inaccuracies and weak reasoning.384 Does this mean that Bryn consciously manipulated the figures in order to confirm his ideological convictions?

It is easy to find examples of sloppiness in Bryn’s work, both in his overall analysis and in its particulars. His lack of attention to detail may partly explain the impressive rate at which he published scientific results. The treatise The Anthropology of Troms County (Troms fylkes antropologi) demonstrates his carelessness. Some of the correlations he claimed to have discovered between racial traits were simply wrong, and his graphical representations of the findings did not always match the figures that they were supposed to represent, though they often fit Bryn’s theories well.385 This does not necessarily mean that Bryn deliberately manipulated his data. The errors in the diagrams on bastard types in The Anthropology of Troms County served to confirm Bryn’s preconceived ideas. On the other hand, the overall analysis in the same thesis was fundamentally flawed in a way that served to undermine Bryn's own arguments. As was explained in chapter 6, Bryn claimed that the population of the county was comprised of three parental races: the Alpine, the Nordic and the Paleoarctic/Lapp. He assembled a series of ‘bastard types’ which he claimed to have identified in the contemporary population. Then he attempted to estimate the contribution of each of the three original races to the current populace. By calculating the relative frequency of the racial traits of the parental races within the present population, Bryn thought he could reconstruct a prehistoric situation of racially pure populations and estimate their relative size.386

He did not stop there, however. Having calculated the contribution from each primordial race to the original population of the country, he also tried to go from the past to the present and recalculate the size of each racial element in the contemporary population. Then, however, he took as his premise the notion that racial traits were inherited according to Mendelian mechanisms. He assumed that certain traits were dominant and others recessive. The results of Bryn's calculation did not match the findings in his survey of the contemporary population. Without being aware of it, Bryn had made a circular argument, though he changed its terms along the way. When moving from the contemporary mixed population back to the pure ancient races, he had not questioned the assumption that some traits were inherited recessively and others dominantly.

The reasoning was flawed, but instead of discovering and correcting his mistakes, Bryn constructed a variety of ad hoc hypotheses to explain the discrepancies he thought he had identified. Among other things, he dismissed the conclusions in his own previous studies of the inheritance of eye colour and skull shape.387 In The Anthropology of Troms County, Bryn criticised himself when making new (erroneous) findings that contradicted his own previous findings.388 The same torturous reasoning was used to reconcile the calculation errors he made when analysing the figures from the great conscript survey. In Antropologia Norvegica I, Bryn himself claimed that it was difficult to explain some of his figures, which Schreiner later regonised as errors.389 If Bryn had not made the mistakes, it would have been easier for him to interpret the data. The flaws and errors in Bryn’s works should primarily be seen as indicative of inaccuracy, sloppiness and hastiness. His rough working methods, combined with an inclination for high-flown hypothesising and a strong faith in the Nordic dogma, led to the strong one-sidedness in his research. Nevertheless, this does not imply that Bryn was consciously disseminating fraudulent findings.

Dismissing the Nordic idea

In 1929, the year Die Somatologie der Norweger was published, Alette Schreiner gave a speech on ‘The Philosophy of Life and the Development of Life’ (‘Livssyn og livsutvikling’). This is the earliest source I have found in which she or her husband explicitly discussed the idea of the superiority of the Nordic race.390 In the speech, she advocated the same kind of evolutionary ideas that had previously been outlined in her popular scientific works. For the first time, however, Alette portrayed Nordicism as a prime example of the kind of evolutionary thinking she dismissed. According to Alette, the essential driving force of evolution was not self-preservation and the struggle for survival, but the drive towards self-realisation (selvutfoldelsesdrift): there is a general tendency in all biological development, she claimed, towards the emergence of the civilised human being with its ‘beautifully vaulted cranium’. If the struggle for life becomes too brutal, the development of life forms lead to evolutionary dead ends; the selective pressure produces species that are increasingly specialised and inflexible and that finally become incapable of adapting to environmental changes. She pointed to the dinosaurs as a prime example; their success in the struggle for survival had turned them into ‘monsters of technical perfection’, but they had also developed low and narrow braincases that hindered the evolution of their brains. That is why these ‘wonderful […] war machines’ finally became extinct.391

Alette summed up her line of reasoning by comparing those extinct ‘master animals’ with the contemporary master race of man:

And we should erect a monument to them [the dinosaurs], we the Nordic peoples, who are imbued with so much of their spirit. Maybe it is the Nordic race—the master race of the blue Viking and of warrior blood, praised by poets and others as the most glorious product of the struggle against a harsh environment and the proof of this struggle as the only fruitful means of development—who will be the next to run our head against the wall! 392

Instead of attacking the notion of a warrior-like Nordic race, Alette Schreiner criticised the very idea of a biological and cultural evolution driven by the struggle for survival and favouring the kinds of human abilities that the Nordic race embodied. She compared the Nordic warrior race to the dinosaurs: perfectly equipped for the struggle for life, but still an evolutionary dead end. In short, she portrayed the idea of the Nordic master race as the very negation of the teleological evolutionism upon which she based her ‘philosophy of life’. Three years later, in the popular-scientific radio-lecture The Races of Europe, Kristian Emil Schreiner dismissed the idea of ‘the Nordic man as the sole creator of the highest intellectual culture’. He also criticised the ‘many so-called racial hygienists’ who held that ‘the real task of racial hygiene’ was to ‘cultivate and favour the Nordic race at the expense of all other types of human beings’. He declared that from a ‘scientific viewpoint’, the Nordic race clearly belonged among the superior races, but that its ‘superiority over all other races’ had not been ‘historically proven’. The Nordic race was a ‘race of warriors and explorers, hardy, enterprising, independent and adventurous men’, but as creators of culture, they lacked persistence. With regard to such properties, ‘the Mediterranean race and the Oriental races were clearly equivalent to the Nordic’. The ‘stabilising and unifying element’ in Western Europe, however, was not these but ‘the often belittled Alpine race’, whose strengths were ‘unwavering stamina’, ’love of the earth’ and ‘austerity’.393

Nevertheless, according to Kristian Emil, Europe’s leadership in the world was not the product of the mental characteristics of a single race, but of the ‘happy interaction of races that had complemented and mutually stimulated each other. To glorify one race at the expense of others must therefore be regarded as unscientific’. A scientifically-based racial hygiene should not be associated with ‘one or the other anthropological race, but with more or less superior and inferior genetic properties that are present in all races’.394

Anti-racists?

There is nothing to suggest that in the early 1920s Alette and Kristian Emil Schreiner took a clear stance against the notion of the Nordic master race, nor is there any evidence that they supported the idea. It is more likely that they thought of the racial ideology that Halfdan Bryn advocated as a set of theories and hypotheses that could and should be proved or disproved with the help of science. It is certain, however, that from the late 1920s they took a clear stance against Bryn’s racial worldview, which they now regarded and rebutted as unscientific.

It is nevertheless important to note that their position did not amount to a general rejection of the idea of racial hierarchies. In her speech on ‘The Philosophy of Life’, Alette used arguments predicated upon a hierarchy of races. She claimed that there was a gradual transition between animals and humans with regard to intellectual qualities, and that the brains of white men were more advanced than the brains of ‘inferior’ human types.395 In her husband’s radio lecture there was also no rejection of the notion of superior and inferior races. Kristian Emil simply said that the Nordic race had to share the top of the racial hierarchy with other equally superior European races.

Alette and Kristian Emil Schreiner were opposed to an ideology that saw racial difference as the central driving force of human history. They also rejected the notion that European races could be placed in a hierarchy. However, neither of them rejected the basic idea of superior and inferior races, and this basic idea continued to influence their research even after their dismissal of Nordicism. Zur Osteologie der Lappen was published in the 1930s and, as we saw in the previous chapter, this work was influenced by the idea of Sami racial inferiority. In accepting racial hierarchy as an unproblematic presupposition for their own scientific research, the Schreiners also contributed to its reproduction and legitimisation.

Kristian Emil Schreiner delivered the traditional eulogy in the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters after Halfdan Bryn’s death in 1933. In his address Schreiner praised Bryn for his enthusiasm and energy, but noted that his work was not free from the weaknesses of a self-taught man and spoke ironically about Bryn’s ‘research’ on the mental characteristics of the races. Still, there was no great principal difference between their attitudes on this question. Schreiner, like Bryn, referred to traditional assumptions about the mental properties of the races, and even though he often emphasised that these beliefs had not been scientifically tested, he nevertheless implied, on other occasions, that there was scientific evidence for his conception of equally valuable, but still mentally distinct European races.396

Like Bryn, both Alette and Kristian Emil accepted the idea of psychological differences between races, and they maintained a set of traditionally-established ideas about the mental characteristics of the various ranked races. It can also be argued that even if they did not support an all-embracing racial ideology based upon the notion of racial inequality, their notions of racial superiority had a real impact on their view of humankind and on their way of acting towards their fellow human beings.

In the preface to the local study undertaken in Tysfjord in Nordland as part of the great racial survey, Alette Schreiner commented on practical problems in the study of the local Sami population (see Fig. 24). She wrote: ‘As is often the case with primitive people, most of our Lapps, despite their childlike curiosity and friendliness, were reluctant to submit themselves to an accurate examination, especially when it came to undressing the body’.397 The problem was mainly that they did not understand the purpose of the survey and therefore did not consider it worthwhile. She continues: ‘Using small gifts, it was possible to get most of them to submit themselves to a more or less thorough examination; not infrequently, it was necessary to resort to mild force’.398 It was probably her notion of the primitiveness of the Sami that made her think it was legitimate to use ‘mild force’ when conducting her investigations. It is difficult to imagine that she would have found it equally legitimate to use ‘small gifts’ or ‘mild force’ when she measured nursing students in Oslo for her anthropological thesis on Norwegian women.399

Fig. 24 According to Alette Schreiner it was uncommon for the Sami to regard themselves as ‘Norwegians’. She maintained that the intellectually superior among them had the most developed Sami ethnic identity. For example, she claimed that the man on the right in this picture (from the Sami community of Tysfjord) ‘undoubtedly’ had huge amounts of ‘Nordic’ blood in his veins and that he also had a strong sense of Sami national consciousness. This implies that Alette Schreiner considered ethnic consciousness to be a sign of intellectual superiority, which was in turn associated with racial superiority.

Notions of Sami primitiveness also influenced the way the anatomical institute responded to local protests against the excavations of Sami burial sites. After having excavated the churchyard at Angsnes in Varanger, the excavator, a student named Bjarne Skogsholm, wrote to Schreiner that the Sami were ‘ridiculously superstitious’ and very dissatisfied with the disturbance of their ancestors’ graves. Still, the excavations went ahead.400

It is clear that Alette and Kristian Emil Schreiner were not what we would today call ‘anti-racists’. Nevertheless, they were opposed to a certain racist ideology which drew its legitimacy from science and which, from the end of the 1920s, became increasingly important politically, first and foremost because of the affinity between the Nordic idea and Nazism.

The breakdown of communication

When the great racial survey was initiated in the early 1920s, Bryn and the two Schreiners had differing views on a number of scientific and ideological questions. Nevertheless, all three seem to have agreed that these types of questions could and should be solved through scientific research. However, when the ‘descriptive’ data from the survey was about to be analysed, their interpretations were revealed to be in conflict. Contradictory views of the racial composition of the Norwegian people were justified using the same empirical material; their different scientific perspectives were based on, and helped to legitimise, different evolutionary beliefs and worldviews. This does not mean that either Bryn or the Schreiners were consciously manipulating the data to fit their preconceived ideas. The fact is rather that the research they undertook could not provide unambiguous answers to the questions which increasingly divided them. When Bryn and Kristian Emil Schreiner interpreted their data, they chose to draw on different aspects of the range of established theories and knowledge within the physical anthropological tradition of research. The choices they made were influenced by the ideological and cultural implications of the various possible explanatory strategies. Therefore, both parties could use the same ‘raw data’ to produce dissimilar and internally contradictory scientific knowledge, and they could use this knowledge to legitimise significantly different worldviews.

Despite analysing the same empirical reality using theories, methods and concepts developed within the same physical anthropological tradition, they still reached contradictory conclusions. The tensions that had existed in the discipline of physical anthropology since the nineteenth century had not subsided, and they continued to exist within the framework of Martin’s ‘descriptive’ anthropology. The great racial survey rekindled many of these divisions. When Bryn and Schreiner began to analyse the collected data, they could draw on different strands of the research tradition. Each could defend his viewpoint using arguments taken from the physical anthropological armoury of methods, theories and already established scientific ‘facts’. Thus, both parties confirmed their own worldview using the same empirical material and the same scientific method.

334 Vitak (Vitak: The National Archives in Oslo/Riksarkivet): Protokoll, 1 October 1919.

335 Vitak, no. 218, 27 October 1919. Letter from K. E. Schreiner to the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters.

336 Bryn’s archive: Schreiner to Bryn, 4 October 1919.

337 St forh. 6A: Indst. S. XXVI, 1920 and Inst. S. XXVI, 1921.

338 The data from Sogn was not published in a monograph, but was used in Alette Schreiner’s genetic study ‘Zur erblichkeit der Kopfform’, Genetica, Vol. 5, nos. 5-6 (1923), pp. 385-454, and in K. E. Schreiner, Anthropological Studies in Sogn, Skr. D. n. Vidensk. Akad. MN kl. 19 (Oslo: I kommisjon hos Jacob Dybwad, 1951). K. E. Schreiner, Anthropological Studies in Sogn, pp. 6, 9.

339 Alette Schreiner, Anthropologische Lokaluntersuchungen in Norge. Valle, Hålandsdal und Eidfjord, Skr. D. n. Vidensk. Akad. MN kl. 1929 (Oslo : I kommisjon hos Dybwad, 1930), p. 7; idem, Anthropologische Lokaluntersuchungen in Norge, Hellemo (Tysfjordlappen), Skr. D. n. Vidensk. Akad. MN kl. Oslo 1932 (Oslo: I kommisjon hos Dybwad, 1932).

340 Bryn’s archive: Lundborg to Bryn, 25 May 1918.

341 Bryn’s archive: K. E. Schreiner to Bryn, 6 March 1918.

342 Gustav Retzius and Carl M. Fürst, Anthropologia suecica: beiträge zur Anthropologie der Schweden nach den auf Veranstaltung der schwedischen Gesellschaft für Anthropologie und Geographie in den Jahren 1897 und 1898 ausgeführten Erhebungen (Stockholm: [n. pub.], 1902).

343 Bryn’s archive: K. E. Schreiner to Bryn, 29 February 1920, 23 March 1920, 10 April 1920, 17 April 1920, 6 May 1920.

344 Halfdan Bryn and Kristian E. Schreiner, Die Somatologie der Norweger, Skr. D. n. Vidensk. Akad. MN kl (Oslo: I kommisjon hos Dybwad, 1929), pp. 2-6.

345 Rudolf Martin, Lehrbuch der Anthropologie in systematischer Darstellung mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der anthropologischen Methoden (Jena: Gustav Fischer, 1914).

346 Halfdan Bryn, ‘Researches into Anthropological Heredity’, Hereditas, 1 (1920), pp. 186-212; idem, ‘Arvelighetsundersøkelser vedrørende index cephalicus’, Tidsskrift for den Norske Lægeforening, Vol. 41, no. 10 (1921), pp. 431-52.

347 Bryn’s archive: A. Schreiner to H. Bryn, 2 December 1920.

348 Bryn’s archive: A. Schreiner to H. Bryn, 19 December 1920.

349 Bryn’s archive: A. Schreiner to H. Bryn, 19 December 1920.

350 Alette Schreiner, ‘Zur erblichkeit’, pp. 411-13.

351 Schreiner, ‘Zur erblichkeit’, p. 449 and passim.

352 Ibid., pp. 444-45.

353 There are many references to this debate in Norwegian anthropological literature. My account is mainly based on Gustav Retzius, ‘Blick på den fysiska antropologiens historia’, Ymer, Vol. 16, no. 4 (1896), pp. 240-41; Gaston Backman, ‘Den Europeiska rasfrågen ur antropologisk och sociala synspunkter’, Ymer, Vol. 35, no. 4 (1915), p. 345.

354 Schreiner, ‘Zur erblichkeit’, p. 449.

355 Bryn’s archive: Alette Schreiner to Bryn, 19 December 1920.

356 Bryn’s archive: Schreiner to Bryn, 11 December 1917, 6 February 1917, 6 March 1918, 25 September 1918, 4 October 1919, 10 October 1920, 12 April 1920, 5 April 1922, 15 October 1922 and 31 March 1924. Quotation from Schreiner’s letter to Bryn, 18 January 1924.

357 C.M. Fürst‘s archive: K. E. Schreiner to Fürst, 13 June 21; Bryn’s archive: Alette Schreiner to Bryn, 1 February 1921; K. E. Schreiner to Bryn, 31 January 1923, 18 January 1924, letter no. 43, 1924 [partly undated].

358 Among the letters from Schreiner there is also a list of questions concerning the project that Bryn had sent to Schreiner in the period 1923-1925; he received no reply. C. M. Fürst’s archive: Schreiner to Fürst, 20 December 1926; Bryn’s archive: sections of The Racial Character of the Swedish Nation with a note by Bryn indicating that he is the author of part of the manuscript.

359 Gunnar Broberg and Mattias Tydèn, Oönskade i folkhemmet. Rashygien och Steriliseringar i Sverige (Stockholm: Gidlund, 1991), p. 42.

360 C. M. Fürst’s archive: Schreiner to Fürst, 4 April 1927.

361 Bryn’s archive: K. E. Schreiner to Bryn, 11 September 1925, 14 September 1926 and 21 September 1926.

362 Bryn’s archive: K. E. Schreiner to Bryn, 2 January 1928 and 2 February 1928.

363 Bryn’s archive: Bryn’s drafts of two replies, 6 February 1928 and 11 February 1928.

364 Bryn’s archive: Schreiner to Bryn, 19 February 1928.

365 Bryn’s archive: Schreiner to Bryn, 9 March 1923.

366 Rudolf Martin, Lehrbuch der Anthropologie, p. 212.

367 Bryn’s archive: Schreiner to Bryn, 17 May 22.

368 Bryn’s archive: Schreiner to Bryn, 26 February 1929: ‘Jeg har med den største overraskelse sett at De betegner Martin 13 og 14 som dunkelblau. Martin selv betegner 13 som hellgrau, hvilket den jo også er. Både Wåler og jeg har i våre bestemmelser angitt den mørkeblå farge som 15’.

369 Bryn and Schreiner, Die Somatologie der Norweger, p. 6.

370 Halfdan Bryn, ‘Arvelighetsundersøkelser. Om arv av øienfarven hos mennesker’, Tidsskrift for den Norske Lægeforening, Vol. 40, no. 10 (1920), pp. 329-42; idem, ‘Researches into Anthropological Heredity. On the Inheritance of Eye Colour in Man. II. The Genetic of Index Cephalicus’, Hereditas, Vol. 1, no. 2 (1920), pp. 186-212.

371 Halfdan Bryn, Über die Augentypen in Norwegen und ihre Vererbungsverhältnisse, Skr. D. n. Vidensk. Akad. MN kl. 1926, no. 9 (Oslo: I kommisjon hos Dybwad, 1926); Rudolf Martin, Lehrbuch der Anthropologie, pp. 511-12.

372 Halfdan Bryn, Homo cæsius, Skr. D. Kgl. no. Vid. Selsk. (Nidaros: F. Brun 1930), p. 110.

373 Halfdan Bryn, ‘Den Nordiske rases sjelelige trekk’, Ymer, Vol. 49, no. 4 (1929), pp. 340-50; idem, ‘Seelische Unterschiede zweier Spielformen der nordischen Rasse’, Volk und Rasse, Vol. 4 (1929), pp. 158-64.

374 Halfdan Bryn, ’Den nordiske rases sjelelige’, p. 348.

375 Alette Schreiner, Die Nord-norweger, Skr. D. n. Vidensk. Akad. MN kl. (Oslo: i kommisjon hos Dybwad, 1929), pp. 172-74.

376 Ibid.

377 Bryn and Schreiner, Die somatologie, pp. 551, 561.

378 Bryn’s archive: K. E. Schreiner to Bryn, 17 April 1920.

379 Ola T. Alsvik, ‘Friskere, sterkere, større, renere’: Om Carl Schiøtz og helsearbeidet for norske skolebarn (Master's thesis, University of Oslo, 1991).

380 Halfdan Bryn and Kristian E. Schreiner, Die Somatologie der Norweger, Skr. D. n. Vidensk. Akad. MN kl (Oslo: I kommisjon hos Dybwad, 1929), p. 334: ‘[…] und diese psychischen Eigentûmlichheiten äussern sich bald in Zufriedenheit mit den bestehenden Lebensbedingungen, bald in unzufriedenheit mit ihnen, und dies führt dann das Bedürfnis mit sich, sich anderswo zu versuchen’.

381 Bryn and Schreiner, Die Somatologie der Norweger, p. 342.

382 Ibid., pp. 337-38.

383 Ibid., pp. 478-84.

384 An example of Schreiner’s critique: on p. 521 in Die Somatologie der Norweger, Kristian Emil Schreiner dismisses Bryn’s description and analysis of the racial composition of the population of Møre county, claiming that Bryn’s previous research on the distribution of eye and hair colour deviates significantly from the findings in the conscript survey.

385 Bryn, Troms fylkes antropologi, p. 75, table 44: compare 'bastards' nos. 7-10 with nos. 17-18.

386 This is a somewhat simplified account of Bryn’s method; see Bryn, Troms fylkes antropologi, chapters 9 and 10.

387 Halfdan Bryn, Troms fylkes antropologi, pp. 97-116.

388 Ibid., p. 107.

389 Bryns archive: Schreiner to Bryn, 2 February 1928. Schreiner remarks that Bryn himself on page 6 of his book noted that the average figures seemed suspiciously low.

390 Alette Schreiner, ‘Livsutvikling og livsanskuelse’, Kirke og kultur (1929).

391 Ibid., pp. 460-61.

392 A. Schreiner, ’Livsutvikling og livsanskuelse’, p. 461.

393 Kristian Emil Schreiner, ’Europas menneskeraser’, Universitetets radioforedrag. Mennesket som ledd i naturen (Oslo: [n. pub.], 1932), pp. 143-45.

394 Ibid., pp. 143-45.

395 A. Schreiner, ‘Livsutvikling og livsanskuelse’, p. 469.

396 K. E. Schreiner, ‘Minnetale over divisjonslæge Halfdan Bryn’, Avhandlinger, Det Norske videnskaps-akademi. I MN kl. 1933; idem, ‘Europas menneskeraser’, pp. 143-45.

397 Alette Schreiner, Anthropologische Lokaluntersuchungen in Norge, Hellemo (Tysfjordlappen), Skr. D. n. Vidensk. Akad. MN kl. 1932 (Oslo: I kommisjon hos Dybwad, 1932), p. 13: ‘Wie es wohl im allgemeinen mit primitiven Menchen der Falle ist, waren unsere Lappen, trotz ihrer kindlichen Neugierde und Freundlichkeit, meistens recht unwillig, sich einer kindlichen Neugierde und Freundlichkeit, meistens recht unwillig, sich einer genauen Untersuchung zu unterwerfen, vor allem insofern dieselbe eine Entblössung des Körpers’.

398 Alette Schreiner, Anthropologische Lokaluntersuchungen, p. 13: ‘[...] nicht selten war es notwendig, zu sanfter Gewalt zu greifen’. Concerning the Tysfjord survey and Schreiner’s attitudes to the Sami, see also Bjørg Evjen, ‘Measuring Heads: Physical Anthropological Research in North Norway’, in Acta Borealia (1997), pp. 3-30.

399 Alette Schreiner, Anthropologische studien an Norwegische Frauen, Skr D. n. Vidensk. Selsk. MN kl 1924 (Kristiania: I Kommission bei Jacob Dybwad, 1924).

400 Skogsholm’s letter cited in Audhild Schanche, Graver i Ur og Berg: Samisk gravskikk og religion fra forhistorisk til nyere tid (Karasjok: Davvi Girji, 2001), p. 50.