9. Science and Ideology, 1925-1945

The rising tensions between Alette and Kristian Emil Schreiner and Halfdan Bryn were related to changes in their political and scientific surroundings. From the end of the 1920s, the idea of the superior blond race became the object of an increasingly polarised debate in the international scientific world. Dogmatic racial ideas gained support within German anthropology, and advocates of racial inequality and the fear of ‘bastardisation’ began to dominate the International Federation of Eugenics Organizations (IFEO). Meanwhile, a growing number of geneticists, physical anthropologists, social scientists and humanities scholars in the English-speaking world and in Scandinavia began to question the scientific legitimacy of such ideas. During the 1930s, these tensions were reinforced by the reactions to Nazi-German racism. This chapter shows how the rising conflict between Bryn and the Schreiners was intertwined with the increasingly divisive and politicised debate on race within the scientific world, the racial hygiene movement and society at large.

As we have seen, there is nothing to suggest that the Schreiners actively supported or distanced themselves from the idea of the superior Nordic race in the early 1920s. By the end of the decade, however, they took a clear stance against it and began to brand it as unscientific. Their altered attitude was probably symptomatic of a general change of mood in the Norwegian academic community. The kind of racial thinking that Bryn represented did not encounter very strong opposition in the early 1920s, but it became far more controversial in the early 1930s. Accordingly, Bryn suffered a loss of scientific prestige in his home country. In Germany, on the other hand, he was more in tune with the prevailing political and academic trends, and there his academic status rose markedly during the same period. The reason was the same in both cases: Bryn’s career as a scientist was closely linked to the shifting fortunes of the idea of the Nordic master race. This had a major impact on his relationships with his German and Scandinavian colleagues, as well as on his connection to the international eugenics movement.

Bryn and the conflict over Mjøen’s racial hygiene

As we saw in chapter 5, there was no unified eugenics movement in Norway. Jon Alfred Mjøen was in conflict with the University-based experts in genetics and anthropology. Schreiner, Mohr, Vogt and Bonnevie considered Mjøen to be an amateur, and his leading position in the international eugenic movement caused them to abstain from entering the IFEO. Although he shared many of Mjøen’s ideas, Halfdan Bryn, unlike Mjøen, was an acknowledged member of the Norwegian academic establishment. Four years after the ‘attack’ on Mjøen’s book on Racial Hygiene, Bryn received the University’s gold medal for his first anthropological treatise, and, in 1919, he was asked to join the newly founded Norwegian Association for Genetics, an organisation to which Mjøen was denied access.401 Around the time Bryn accepted this invitation, he also visited Mjøen’s private ‘laboratory’ and broached the subject of collaboration. Mjøen reacted positively and made sure that his friends Alfred Ploetz and Fritz Lenz were aware of Bryn’s research.402 Nevertheless, he also made it clear that Bryn would have to distance himself from Otto Lous Mohr and the two Schreiners before any professional cooperation could begin.

Kristian Emil Schreiner had been involved in the ‘attack’ on Mjøen’s book in 1915. In a newspaper article, he had described Mjøen as a pseudo-scientist who claimed scientific authority to which he was not entitled.403 In a letter to Bryn, Mjøen bemoaned this critique which, in his view, was not scientifically motivated: ‘the attack was characteristic of the personalities of those who planned, organised, and carried it out [and] if anything can be characterised as malice and callousness, it is these people’s attempt at ruining my life’.404 Mjøen was convinced that Alette Schreiner was still ‘spreading lies’ behind his back, and he did not feel able to enter into a trusting relationship with Bryn if he was also collaborating with the Schreiners.405

Bryn received two more letters from Mjøen in 1920.406 Then the correspondence appears to have dried up for many years, which may suggest that Bryn felt pressured into choosing the Schreiners’ side in the conflict and dropping his proposed collaboration with Mjøen. If so, this was a strategically wise decision, as working with Mjøen could have disrupted a relationship with the Schreiners that was fundamental to Bryn’s professional success; Kristian Emil Schreiner used both his contacts and his prestige to help Bryn with funding and publication.407

Rising tensions beneath the surface

In the mid-1920s, it had become clear that Bryn and Kristian Emil were in disagreement on a number of questions related to the great racial survey, but this did not for the moment lead to deeper conflict or open argument. In late August 1925, a conference was arranged in Uppsala and Stockholm with the aim of strengthening Nordic cooperation on racial research. In addition to Halfdan Bryn and the Schreiners, Jon Alfred Mjøen and his wife were invited from Norway. The Schreiners declined to attend, in their own words, due to the heavy workload at the anatomy department. By not attending the conference, however, they also kept their distance from an academic setting in which Mjøen was accepted as a legitimate participant. They furthermore avoided discussions on topics about which they would probably have had fundamentally different opinions to those of Bryn and Lundborg.

Two of the thirteen presentations made at the conference were given by Halfdan Bryn. One was on the inheritance of eye colour, a topic that was a source of disagreement between Bryn and Kristian Emil. The other was about the anthropology of eastern Norway and was probably based on Antropologia Norvegica I, published that same year. Bryn’s papers won great acclaim from Lundborg, who was particularly intrigued by Bryn’s analysis of the data from Oslo, an analysis which, as previously noted, would later be criticised by Kristian Emil.

Two items on the programme were aimed at bringing about closer Nordic cooperation. One was a preliminary discussion regarding a proposed organisation of Nordic racial researchers. The other was a speech by the Icelandic professor Gustaf Hannesson, on ‘Nordic Measuring Techniques and Nomenclature for Anthropologists’. Hannesson was making anthropological studies of the Icelandic population and had cooperated with Bryn and Lundborg since the early 1920s. He spoke strongly in favour of establishing a common Nordic standard for anthropological measurement and of introducing a shared Nordic terminology.

Hannesson was highly sceptical of Kristian Emil’s approach to anthropology, which he found excessively empirical and descriptive. In 1922, he wrote to Bryn that he preferred Bryn’s modus operandi to ‘Schreiner’s method’, which was like ‘driving out one devil, and letting seven others in’.408 In a letter written five years later, Hannesson once again expressed doubts about the usefulness of Schreiner’s ‘meticulous survey of bones’. ‘Anthropology must aim at living human beings and their future’, he claimed. The discipline should not remain content with measuring only outward physical characteristics; one way or another, psychological properties had to be considered.409

The year after the Scandinavian race conference, Mjøen resumed his correspondence with Bryn and informed him that he had been ‘attacked’ by the American academic William Castle, author of a paper strongly criticising Mjøen’s theories on racial mixing (see Fig. 25). Mjøen believed that this incident would usher in a ‘permanent’ struggle over the issue. Professor Charles Davenport had told Mjøen that ‘professor Castle is pugnacious’ and that ‘he had also attacked Davenport’.410 Mjøen contacted Bryn because he wanted to refer to Bryn’s research in his reply to Castle.

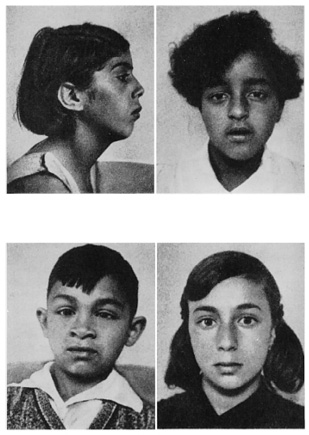

Fig. 25 Racial mixing. Photo from the 1938 edition of Mjøen’s book Racial Hygiene. The subject is supposed to exemplify a ‘Nordic-Lapp mixed type’ possessing typical ‘bastard’ features, such as ‘a discordant mentality’ and ‘poorly developed mental faculties’.

Mjøen’s prediction proved to be correct and the struggle became protracted. His adversary had an influential position in American genetics. In 1916, Castle had written the book Genetics and Eugenics, which was the most commonly used textbook on the topic at American colleges in the 1920s. He had been one of Davenport’s students, but became by the mid-1920s an engaged and profiled critic of the orthodox type of eugenics that Davenport represented. Castle's critique along with those of certain other prominent scientists helped to set the agenda for intensive debates about psychological differences between races and the degenerative effects of racial mixing (see Fig. 26).411

In autumn 1927, the IFEO arranged an international congress in Amsterdam at which Davenport was elected president. Under his leadership, racial mixing and psychological differences between races became prioritised fields of study. At the same time, other topics in the field of human genetics and anthropology, which until then had been discussed under the auspices of the IFEO, were taken up by competing institutions. In subsequent years, therefore, the IFEO became increasingly dominated by an explicitly racist style of eugenics.412

25 countries were represented at the Amsterdam congress. Kristine Bonnevie, Kristian Emil Schreiner, Jon Alfred Mjøen and his wife came from Norway. This time Bryn cancelled his participation, despite the fact that he was supposed to make a presentation. After the congress, Schreiner reported to Bryn that Mjøen had given a ‘terrible’ speech on racial mixing. It had been strongly criticised by everyone with whom Schreiner had spoken. Mjøen had invoked Bryn’s support and Schreiner thought it was unfortunate the Bryn had not been there to denounce him.413 However, there is nothing in the letters between Mjøen and Bryn to suggest that Mjøen would have met with any criticism from Bryn if he had indeed attended the congress. Quite the opposite, for Mjøen had the backing he wanted from Bryn in his polemics against Castle.414

Fig. 26 Racial mixing. The children of German women and the African soldiers who participated in the French occupation of the Rhineland in 1923. Mjøen used them as examples of ‘bastards’ in his book Race Hygiene.415 At that point, in 1938, the so-called ‘Rhineland bastards’ had already been sterilised through a campaign led by Eugen Fischer, Hans Günther, Fritz Lenz and Wolfgang Abel.

Tensions reach the surface

Only a few months after the Amsterdam congress the tensions between Bryn and Schreiner moved into open conflict, and soon after Bryn became a public ally of Mjøen. February 1928 saw the total collapse of cooperation on the analysis of the data from the great Norwegian racial survey. Five months later Bryn accepted Mjøen's nomination to become a member of the IFEO,416 and he was soon a member both of the IFEO and of Mjøen’s Consultative Eugenics Commission of Norway.417 Formally, Bryn entered the IFEO as a representative of the Royal Society of Science in Trondheim. In reality, he was never a particularly active member, and Mjøen paid his membership fees. Bryne nevertheless received a number of requests from the IFEO. Among other things, the organisation tried to establish a worldwide overview of ongoing processes of racial mixing, and asked for an account of Bryn’s research on the northern Norwegian ‘bastards’. Bryn’s response to these inquiries was rather lukewarm.418

Mjøen had the largest interest in bringing Bryn into the IFEO. The IFEO was supposed to be a coalition of the foremost organisations and institutions relevant to the field of eugenics. Its leaders saw Mjøen’s membership as the most important factor preventing key Norwegian scientists from joining. In this situation, it must have been an advantage for Mjøen to recruit a recognised scientist such as Bryn to the organisation, even though Bryn was a poor substitute for Kristine Bonnevie, who had already turned down a series of offers. The irony is that, by all accounts, Bryn’s entry into the IFEO and the Consultative Eugenics Commission of Norway weakened his academic prestige in Norway and made him a less valuable asset for Mjøen.

Kristian Emil Schreiner was also invited to collaborate with the IFEO under Davenport’s leadership. In 1930, he received an invitation to an IFEO conference which aimed at establishing a better methodology for research on racial differences in intelligence. At the conference, a committee of psychiatrists and psychologists tried to establish an international standard for the measurement of intelligence, while a committee of physical anthropologists suggested a set of international standards for anthropometric measurements that could then be proposed at an international anthropology conference in Lisbon the same year. In contrast to Lundborg, who was involved in this undertaking, Schreiner refused to participate.419

Around the same time as the IFEO conference, Lundborg attempted to persuade Schreiner to organise the planned second Scandinavian conference on racial science in Oslo, but Schreiner had by then lost all interest in efforts at Scandinavian cooperation. One of the reasons was that ‘Lundborg’s studies and interests’, as Schreiner saw them, had become ‘more and more distanced from what we normally think of as anthropology’.420 The Oslo conference was never held, and permanent Nordic cooperation on racial science ended before it began. At this point, Lundborg's academic prestige began to decline in Sweden. His activities received negative reviews in Swedish newspapers. He was about to reach the age of retirement and the struggle over who was to succeed him at the Institute for Racial Biology had started. In 1936 the social democrat, geneticist and anti-racist Gunnar Dahlberg assumed the position, signalling the end of the Nordic race's heyday at the Institute.421

Nazism and the Nordic idea

The increasingly polarised scientific debate on race was partly a response to the rise of the Nazi movement in Germany. However, the relationship between National Socialism, racial hygiene, anthropology and ‘the Nordic idea’ was complex. The critique against dogmatic racism was already on the rise before Nazism became a powerful movement, and ideas that resemble Nazi racial ideology gained a strong foothold in German anthropology well before the Nazi takeover of 1933.

The reorientation of German anthropology wasthe work of a new generation of scholars who brought new ideas into the discipline. A key representative of this generation was Hans Günther. He had a background as a völkish writer. During the 1920s, he became the chief ideologue of the Nordic movement, which combined racial science with right-wing romantic nationalism and the idolisation of the Nordic race. In the 1930s, he became a professor of anthropology, a member of the Nazi Party and an influential race ideologue of the Third Reich.422 Günther had strong ties to Scandinavia, and in the early 1920s he cooperated with Bryn, Kristian Emil Schreiner and Lundborg. A closer look at Günther’s activities as an ideologue and populariser of science may illuminate the relationship between the Nazi movement, the Nordic idea and physical anthropology in Germany and Scandinavia.

In the 1920s, Günther became well known among the German public for his popular-scientific writings. In 1922, he published the book Racial Science of the German People (Rassenkunde des deutschen Volkes), which soon became a best-seller. It was followed by a series of similar books, such as Racial Science of the Jewish People (Rassenkunde des judischen Volkes) and Racial Science in Europe (Rassenkunde Europas). Before 1930, Racial Science of the German People had been reprinted in its tenth edition and Günther was so well-known to the German public that the publisher could, in an advertisement from 1929, describe the abridged version of his book as ‘Der billige Volks-Günther (The Affordable Günther For All)’. During the Third Reich, Günther’s books on Rassenkunde became even more popular.423

Publisher J. F. Lehmann had taken the initiative for Racial Science of the German People. Allied to Adolf Hitler from the early 1920s, and specialising in popular-scientific literature on race,424 Lehmann had first tried to persuade Rudolf Martin to write the book, but Martin rejected the proposal because he thought that anthropology was too young and immature a science and the data too insufficient for such a book.425 Günther did not have a professional background in anthropology when Lehmann approached him. He was a young humanist scholar, a völkisch nationalist and author. When he accepted the assignment, Günther began travelling to European anthropological institutions to do research for the book. He thus established an extensive network of anthropologists, and even if Günther’s books on Rassenkunde were written by an outsider and meant for the general public, they were also read by professionals. This was the first systematic attempt at giving an overview of the races of Europe since the publication of Denniker’s and Ripley’s books at the turn of the century.426

Scandinavia held a key position in Günther’s worldview: he believed the peninsula to be inhabited by the purest Nordic population in world. Günther had strong personal ties to Scandinavia as well. In 1923, he married a Norwegian woman, Magda (‘Maggen’) Blom, and settled with her in Norway for a couple of years. In 1925, he moved to Sweden where he worked for Herman Lundborg at the State Institute for Racial Biology and as a freelance researcher and author, before returning to Germany in 1929.427

In 1923, the year after the publication of Racial Science of the German People, Günther asked Kristian Emil Schreiner for access to research data from Norway. According to letters from Günther to Bryn, Schreiner had given him this data. Günther also claimed that Schreiner, when sending the material, had taken the opportunity to praise Günther’s book.428

Fig. 27 The Nordic race. When after their survey of recruits, Günther requested a portrait of a purebred Nordic man, neither Schreiner nor Bryn could help him. In 1929, however, Alette Schreiner described this man from the Setesdal valley as a prototypical ‘Viking’.

On a later occasion, Günther visited the anatomy department in search for photos of racially pure members of the Nordic race, images he wanted to use in his book (see Fig. 27). After the visit, he commented in a letter to Bryn that he was very pleased to have become acquainted with Schreiner, who had welcomed him at a ‘very gracious manner’. The next year, Günther met Bryn in person for the first time, and this was the beginning of a lasting personal friendship.429 That same year Bryn wrote a positive review of Racial Science of the German People.430

There is much to suggest that Günther got along well with both Schreiner and Bryn when he met them for the first time in 1923-1924. This changed, however. Early in the 1930s, Mjøen wrote to Bryn that the same people who had once ‘organised the attack on me and my laboratory’ had now attempted to prevent the publication of a Norwegian version of Günther’s book. Mjøen warned Bryn that he should expect opposition from similar quarters.431 Judging from the context, it is likely that Mjøen believed that Alette and Kristian Emil Schreiner were among those who had obstructed the publication of Günther’s book. At the time when Mjøen wrote this letter, Günther was receiving a lot of public attention because of his relationship with the Nazis. In 1931, he accepted a professorship at the University of Jena. His opponents considered this to be a political appointment engineered by the Nazis, winners of the recent local elections. Günther thus became the object of a heated debate in Germany questioning his scientific credentials. This conflict was also reported in the Norwegian newspapers and must have been noted by the Schreiners and the others who had ‘organised the attack’ on Mjøen. The year after his appointment, in 1932, Günther joined the Nazi Party.432

Bryn’s German friends

Bryn and Günther, who met often during their summer holidays by the Oslo Fjord, developed a long-lasting, mutually-beneficial friendship. Since Bryn was already a recognised scientist in the early 1920s, his friendship was an asset to Günther in his attempts to gain academic credibility upon first venturing into the field of racial science. Later on, Günther opened doors for Bryn, providing him with access to the Nordic movement in Germany and even to the German anthropological community.

Günther furthermore saw Bryn as a key collaborator in the quest to spread the gospel of the Nordic race throughout Scandinavia. Günther was a leading member of the Nordischer Ring, which was founded in 1926 and which soon became the most important umbrella organisation for the Nordic movement. The organisation had many scientists among its members and was inspired by authors such as the founders of anthroposociology Vacher de Lapouge and Otto Ammon, the völkisch racial philosophers Ludwig Schemann and Ludwig Woltmann, the American race thinkers Madison Grant and Lothrop Stoddard, as well as Hans Günther and not least Walter Darré, whose völkisch ideas about Blut und Boden and Nordic racial purity had a great impact on the Nazis and were instrumental in winning for Darré the post of Minister of Agriculture after Hitler’s seizure of power.433

The Nordischer Ring was part of the völkisch movement but had no particular relationship with the Nazis before 1930; at that point, the leaders of the organisation acknowledged that the Nazi Party had become so powerful that any future attempt at propagating the Nordic idea would have to be made in alliance with them. In the following years, Günther, like many other leading members, joined the Party. After 1933, the organisation was incorporated into the Nazi movement, and many of its leading members gained prominent positions in the new regime.434 Scandinavia, as a place of Nordic racial origin and purity, played an important part in the organisation’s ideology, and an effort was made to recruit Scandinavian allies. Günther was the main point of contact with Scandinavia, and his alliance with Bryn was an important asset. Bryn joined the Nordischer Ring in 1926 and soon developed an extensive social network of likeminded Germans.435

Many of Bryn’s German acquaintances belonged to the new generation of anthropologists who took the lead in redefining the discipline from ‘Anthropologie’ to ‘Rassenkunde’. One of them was the young anthropologist Egon Freiherr von Eickstedt, a friend of Günther's. In 1925, he began publishing the journal Archiv für Rassenbilder with Bryn as one of his contributors. Later von Eickstedt was appointed to a professorship in anthropology in Breslau and became a leading figure in the discipline.436 Another friend of Bryn's was Bruno Kurt Schultz, an anthropologist, editor at J. F. Lehmann’s publishing house and also editor of Volk und Rasse, a popular-scientific journal established by Lehmann in 1925 and later incorporated into the Nazi-German propaganda machine. At the end of the Weimar period, Bruno Kurt Schultz was also editing the journals Verhandlungen der Gesellschaft für physische Anthropologie and Anthropologischer Anzeiger. The year before Hitler’s takeover, Schultz became a member of the Nazi Party. During the Third Reich he worked for the Rassenamt der SS—the SS Race Office—and was involved in formulating the so-called ‘settlement policy’ in occupied Eastern Europe, which entailed the ethnic cleansing of local Slavic populations and the settlement of members of the Germanic race.437

The rise of Nazism and the destiny of the Nordic idea in Norway

Bruno Kurt Schultz’s career is typical of how the relationship between the Nordic idea, German physical anthropology and the Nazi regime developed. The destiny of the scientific idea of the Nordic race became strongly intertwined with its success as a political idea. After the Nazi takeover, völkisch and right-wing journals and organisations were integrated into the Nazi movement, and the superior Nordic/Germanic/Aryan master race became a key element of the ideology of the new regime. The Germanics were seen as the origin and the core of the German nation. This nation had to be purged of all contamination from alien races, and it had a right and a duty to expand, settle new territories and subdue or displace other races. This ideology was combined with an intense hatred of the Jews, the alleged eternal enemy of the Germanics.

Nazi ideology was strongly inspired by Pan-Germanism, by Gustaf Kossinna’s archaeological theories, by the idea of the Germanic Aryans, by a racist style of eugenics and by Günther’s Rassenkunde. Leading Nazis wanted to establish a Great Germania, which was to include all peoples of Germanic origin. This Germanic empire was meant to expand at the expense of inferior peoples, primarily the Jews and Slavic peoples of Eastern Europe. During World War II, these ideas were applied with brutal consistency. The extermination of the Jews was construed as a war against an internal enemy and an effort to preserve the racial purity of the nation. The war on the Eastern Front was framed as a racial war to ensure ‘Lebensraum’ for the Germanics by killing, displacing or enslaving the native population.

Scandinavia played an important part in the Nazi worldview. Scandinavian peoples were assigned a specific place in the Great Germanic Empire along with other Germanic peoples, such as the Dutch, the Flemish and the Germans themselves. The Scandinavians even had a special position in the historical myths of the Nazis, as the Nordic/Aryan/Germanic race was thought to have its historical roots in northern Germany and southern Scandinavia, and since it was believed that the Scandinavians had maintained an especially high degree of racial purity. Leading Nazis, such as Heinrich Himmler and Walter Darré, held that the Norwegian allodial freeholders, the ‘Odal’ peasants, had kept their race particularly pure and maintained that traditional Norwegian rural culture embodied the racial psychology of the Nordic race.438

Even Scandinavia saw the rise of right-wing organisations inspired by German völkish nationalism, by the Nazis and by the idea of the Nordic race. In 1932, the Norwegian National-Socialist Labour Party (NNSAP) was established. It was based on the blueprint of the German National-Socialist Party (NSDAP), and its members had organisational and personal connections to the NSDAP and the SS. It was, however, a tiny party that never had more than a thousand members and never had any political impact on the national scene.439 The nationalist and fascist party National Gathering (Nasjonal samling, NS), established in 1933, was of greater significance. Its main goal was to overcome class tensions and unite the nation around a set of values and symbols, to establish a corporatist system of governance and to combat Bolshevism. The idea of a superior Nordic race played an important role in the ideology of the NS. It is likely that their racial ideas were partly inspired by Hans Günther; the party leader Vidkun Quisling was a close friend of Günther’s Norwegian sister-in-law, Cecilie Blom.440

Although more influential than NNSAP, even Vidkun Quisling’s NS was rather marginal in the Norwegian political landscape prior to World War II. The party was not even represented in the Norwegian Parliament. However, on 1 February 1942, less than a year after the German invasion of Norway, Vidkun Quisling established a puppet government that ruled the country until the end of the German occupation on 9 May 1945. During these years, when NS membership peaked at 43,000, the party was more unambiguously inspired by Nazi-German role models and tried to reorganise the country according to National-Socialist principles. This effort included participation in the deportation of Norwegian Jews to death camps on the continent.

National Socialism did not become a topic in the correspondence between Bryn and Günther until January 1932, when Günther urged Bryn to contact the Norwegian Nazis. He mentioned Adolf Egeberg Jr., the leader of the NNSAP, and a group of Nazi-sympathising military officers in Oslo; he also referred to Vidkun Quisling and the organisation Nordic Uprising in Norway (Nordisk Folkereisning i Norge). This organisation had been founded the year before and was incorporated into the establishment of the NS in 1933. Günther, however, was particularly concerned with a man called Carl Lie. Lie was the editor of the newspaper Ekstrabladet, which for a couple of years in the early 1930s existed as the Norwegian mouthpiece for German-inspired National Socialism. Günther suggested that Bryn begin writing for Ekstrabladet,441 though Bryn does not seem to have followed up on the proposal. After receiving Günther’s letter, he contributed no signed articles to Ekstrabladet, and there is nothing in the style and content of the unsigned articles to suggest that Bryn was their author.442

Bryn’s racial ideas were similar to, and had the same origin as, the racial ideology of the Nazis, and it is clear that Bryn, through his scientific activities in the 1920s, was involved in developing the conceptual foundation and academic legitimacy of racial ideas that later became key elements of that ideology. There is nothing in the letters between Günther and Bryn to suggest that Bryn was actively opposed to his friend’s political views. Many of the Germans and non-Germans who shared Bryn’s racial ideas ended up supporting the Nazi movement. These included Mjøen and Lundborg: both were members of the Nordischer Ring and both became Nazi sympathisers. However, I have not found any evidence to show that Bryn actively supported the National Socialist movement. Bryn died in 1933, the same year that Hitler seized power in Germany and the NS was established in Norway. After Bryn’s death, Günther put his trust in Quisling as the Nordischer Ring’s main Norwegian contact. While it is unclear to what extent Quisling allied himself with the Nordischer Ring, it is a fact that Günther was convinced he had found in Quisling a prominent Norwegian advocate of the Nordic spirit.443

Sinking scientific credibility in Norway, rising scientific star in Germany

In 1929, Bryn received a letter from Günther, who had read Die Somatologie der Norweger, noted Kristian Emil Schreiner’s criticism and claimed that Bryn had good reason to be upset by the Schreiner couple's ambush.444 Günther praised Bryn for having finally decided to choose Mjøen’s side and join the IFEO, but he pointed out that, a conflict with someone of Schreiner’s high academic standing was likely to weaken Bryn’s scientific prestige.445 Günther’s judgment appears to have been correct: the break with Schreiner and the collaboration with Mjøen were both bad for Bryn’s academic standing in Norway. On the other hand, Günther noted that Bryn still enjoyed a high reputation outside Norway, especially in Germany where his name was acknowledged beyond the small realm of specialists.

There is much to suggest that Günther’s assessment of the situation was correct. During the first years of Bryn’s career as an anthropologist, Kristian Emil Schreiner acted as his advocate and helped to get his works published by the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters in Oslo. Until 1926, most of Bryn’s larger works were published by the Oslo Academy; none were published in Trondheim. After 1926, however, only Die Somatologie der Norweger among his works was published by the Oslo Academy. The three substantial works that he published between 1926 and his death in 1933 were issued by the less prestigious Royal Society of Science in Trondheim, where Bryn himself was highly influential by virtue of his position as president of the Society.

Bryn’s reception in Germany was very different. Prior to 1926, Bryn had not published anything in Germany. In 1926 he published two titles there; in 1929 and 1930, he published eight. Most of them were printed in anthropological journals like Anthropologischer Anzeiger and Verhandlungen der Gesellschaft für physische Anthropologie in Stuttgart, Mitteilungen die Anthropopologische Gesellschaft in Vienna, Archiv für Rassenbilder and the ethnographic journal Anthropos, as well as in the völkisch, popular-scientific journal Volk und Rasse in Munich.446 With the exception of Anthropos, all these publications were edited by Bryn’s friends Bruno Kurt Schultz and Egon Freiherr von Eickstedt, both of whom were rising stars in German anthropology in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

According to Günther, it was the book Der nordische Mensch that made Bryn’s name well-known to Germans interested in the issue of race. This was the first general account in German of Bryn’s research, and it was Günther himself who had initiated the project. It was first titled Kleine Rassenkunde Norwegens and was thus supposed to offer a parallel to Günther’s bestselling books on Rassenkunde, a standard, popular-scientific account of the racial composition of the Norwegian population—the heartland of the Nordic race—written by a leading authority on the subject.

The quality of the final manuscript fell below the publisher’s expectations, as Bryn took the opportunity to put forward his unorthodox theory about the two variants of the Nordic race. In spite of this, the Der nordische Mensch received positive reviews. Journals like Volk und Rasse and Die Sonne, a journal propagating the ‘nordische Weltanschauung’, were laudatory. Even the American scientific journal The Quarterly Review of Biology praised it as an ‘excellent treatise’ and hailed Bryn as ‘one of the most distinguished Norwegian anthropologists’.447

During the summer of 1929, Bryn received a letter from von Eickstedt, who had just become a professor at the University of Breslau and was developing a new department of anthropology and ethnography there.448 He wanted to hang portraits of the discipline's leading figures on the wall of the department’s reading room, and he asked Bryn to send him a signed portrait. A couple of months later he wrote that the picture was now in place and had begun to interest students in Bryn’s publications.449 In other words, von Eickstedt considered Bryn to be a key contributor to the anthropological research tradition, and the letters between them reveal that this was largely due to Bryn’s theory about the two variants of the Nordic race. Von Eickstedt informed Bryn that he had produced slides based on Der nordische Mensch and was using them in lectures.450 In addition, the anthropologist Josef Weininger assured Bryn that the book was eagerly studied in his department, the reason being that the question of the Nordic race was at the core of all debates on the issue of race.451

Thus the interest in Bryn’s book arose mainly its relevance to the ongoing debate about the existence of the Nordic race,452 for some influential German anthropologists argued that the Nordic race was a theoretical construction based on a weak empirical foundation.453 These anthropologists took as their starting point a theory which was commonly held among German anthropologists, namely that the Nordic race descended from the prehistoric Cro-Magnon's. The craniological difference between the Nordic and the Cro-Magnon races, however, was so great that some archaeologists and prehistoric anthropologists held that the two races could not be related. They had the same cephalic index, but differing facial indices. The Nordic race had a long face (it was ‘leptoprosopic’), while the Cro-Magnon race had a broad face (it was ‘hypereuryprosopic’).454

The critics held that these anatomical differences meant that ‘the Nordic race’ should be split into two different taxonomic categories, and that only one of these could be related to the Cro-Magnon race. This biological argument was also underpinned by archaeological studies connecting the two races to two different prehistoric cultures.455

The anthropologist Karl Saller was among those who wanted to abolish the concept of the Nordic race. Many of Saller’s critics belonged to Bryn’s circle of friends, and when they discussed the question in letters to Bryn in the early 1930s, they made no secret of their belief that Saller was politically motivated. After 1933, Saller was among the very few anthropologists who distanced themselves from the racial policy of the new German regime.456 In addition to Saller, Walter Scheidt was singled out as one of the architects behind attempts to deny the existence of the Nordic race.457 Scheidt was a leading racial hygienist and anthropologist. He did not deny that a ‘Nordic race’ might be a useful scientific concept to describe and explore the racial character history of northern European populations, but he dismissed the established delineation and definition of the race, suggesting it could be split into two sub-races.458 Karl Saller took a more radical stance. According to him, ‘the Nordic race’ was a theoretical construct based on a dubious scientific foundation. He used skull measurements and archaeological theories to justify this claim. He even pointed out that the craniologists of the nineteenth century had had different perceptions of the typical Nordic/Germanic skull-shape, and he claimed that evidence casting doubt on the idea of a uniform Nordic/Germanic race had been illegitimately barred from the discipline.459

On this issue, much weight was given to Scandinavian racial anthropology, and the data from Die Somatologie der Norweger were drawn into the debate as soon as they were published.460 Saller’s theory did have some similarities to Halfdan Bryn’s notion of the two types of the Nordic race. Nevertheless, there was one crucial difference. Bryn did not argue for the existence of two races, but for two branches of the same race. According to Bryn, the Nordic race had its roots in Asia, and the two branches had arisen because the Nordics had migrated to Europe in two separate groups. The two groups were slightly different in their genetic composition, and through genetic drift they had developed in distinct directions. This meant that Bryn agreed with the criticism of a Nordic ideal type; the established notion of a Nordic race was not scientifically well-founded. Like Saller and Scheidt, he criticised the way Lundborg, Günther and Fischer characterised the Nordic race.461 But Bryn’s conclusion was different from Saller’s: by defining the characteristics of the Nordic race in a new way, he thought he could prove not only its existence, but also that it was actually more widespread than commonly assumed.

The decline of the idea of the superior Nordic race

The idea of a blond, long-skulled elite race had been part of Norwegian anthropology since Arbo began his research in the late nineteenth century. There is a direct line from Arbo’s assessments of the psychological character of the short skulls and long skulls, via Hansen’s folkepsykologi, to Halfdan Bryn’s racial ideas. Bryn appears extreme, but it can be claimed that he only drew logical conclusions from ideas that had had scientific legitimacy within the Norwegian academic community for several decades.

Bryn died in 1933, and he was the last Norwegian anthropologist to embrace the idea of the blond master race. After his death, there was widespread public criticism of the ideas he represented. Because of political developments in Germany, such notions had become strongly associated with the Nazi movement. In contrast to Germany, this movement had limited political success in Norway. While 37 per cent of German voters supported Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in the election of 1932, their Norwegian counterpart (NNSAP) remained completely marginal, and even Quisling and the NS never got more than 2 per cent of the vote in any election.

1933 saw the establishment of Nazi rule in Germany, but the same year marked the breakthrough of the Labour movement as the dominant political force in Norway. The 1933 election was a landslide victory for the Labour Party, which had recently disavowed its revolutionary past and embraced more pragmatic policies. In 1935, it entered into an agreement with the Farmers’ Party (Bondepartiet), which until then had been the most vociferously anti-socialist party and more open to right-wing ideas than had any other large party in Norway. The agreement between Labour and the Farmers’ Party was aimed at counteracting the economic crisis. It led to a less polarised political landscape and ushered in a long period of Labour Party dominance. From 1935 to 1963, Norway had an uninterrupted series of Labour majority governments. This political development did not provide a fertile climate in Norway for racial ideas now strongly associated with Nazi Germany.

In October 1940, the Norwegian Nazi writer Sigurd Saxlund complained about the political climate that had characterised Norway in the years before the war. In 1919, he had published a series of articles on race in The Norwegian Journal of Pedagogy (Norsk pedagogisk tidsskrift), but when he reworked those articles into a book manuscript in 1933, it was no longer possible to get them published because—according to the author—they were not politically correct in the new environment. Saxlund claimed that Norway was backward in racial science, and that Marxists and liberals dominated the Norwegian University. It was only after the German invasion and the installation of Quisling’s puppet government that Saxlund was able to publish his Race and Culture: The Results of Racial Mixing (Rase og kultur: Raseblandingens følger).462 Saxlund pointed to Halfdan Bryn as a lonely prophet in the Norwegian desert, one who had not received the attention he deserved until he was introduced to a German audience through the publication of Der nordische Mensch.463

The notion of a Nordic race refuses to die

Even if Bryn was the last Norwegian anthropologist to advocate the superiority of the Nordic race, the concept of a Nordic race did not disappear from Norwegian science with his death. Although Alette and Kristian Emil Schreiner rejected racial ideology in the spirit of Ammon, Lapouge and Günther, they continued to believe in the existence of a Nordic race. Thus ‘the Nordic race’ even survived the war, albeit in a somewhat reduced version. No longer a master race, it became a purely descriptive category.

Volume I of Kristian Emil Schreiner’s great work Crania norvegica was published in 1939. It was a study of the more than 2,000 medieval skulls deposited in the Department of Anatomy. The study showed that in the Middle Ages, the eastern Norwegian population was already more long skulled than the western Norwegian population. However, Schreiner also pointed out that there were huge local differences among the eastern Norwegian long skulls. Most local types belonged to the Nordic long-skulls, but there were also some that could be characterised as Cro-Magnon skulls. Between these, moreover, there were a number of transitional types. Schreiner concluded that a comprehensive discussion of the causes behind his findings could not be undertaken before he had also analysed the small amount of Norwegian prehistoric bones. This task would be addressed in Volume II, which was in progress.464

Then the war broke out. The German occupation of Norway had major consequences for Schreiner and his workplace, the University of Oslo. At the outbreak of war, only three professors were members of the NS or had publicly voiced support for the party. Both the Norwegian NS regime and the German occupation authorities, however, wanted to make the University a tool for their political agenda. This policy aroused opposition from the vast majority of professors and students, and turned the university into an ideological war zone. A large number of lecturers were arrested, and the University was finally closed in 1943; 644 students were deported to prison camps in Germany, where an unsuccessful attempt was made to raise their racial consciousness and mould them into SS men.

In 1942, as part of its Nazification campaign, the NS government established a new University Institute of Racial Biology under the leadership of the geneticist Tordar Quelprud. This institute was given the task of conducting research, providing the government with advice on population and teaching racial biology. The subject was given high priority in the NS’s plans for the University. It was part of the planned curricula for medicine, law and theology and other disciplines. If Quelprud had fulfilled his mission, the idea of a Nordic master race would likely have made a strong comeback in Norwegian academia, but after a year as director he resigned his position, citing a less than hospitable social environment.

Quelprud’s closest neighbour at the University was the already extant Institute of Genetics, which happened to be the workplace of Kristine Bonnevie, Quelprud’s former supervisor who was now involved in the resistance movement. The Institute of Genetics was also the workplace of the outspoken anti-Nazi Otto Lous Mohr; just across the yard was the Department of Anatomy, led by Kristian Emil Schreiner, who, along with Mohr, was among the professors imprisoned for their resistance to the Nazification of the University.465

The second volume of Crania norvegica was published right after the war. While Volume 1 had been written in German, the second volume was in English. In the first part of the book, Schreiner compared the small number of Norwegian Stone Age skeletal remains with similar material from other parts of northern and central Europe. The physical anthropological evidence was analysed in light of archaeological theories about cultural areas and cultural diffusion. He found that the Nordic skull shape that was typical of the Iron Age and later medieval findings was prevalent in the Stone Age material as well. When discussing this discovery, Schreiner began by dismissing a theory that had been considered scientifically valid within ‘certain circles’ in ‘recent years’, namely that a ‘pure’ Nordic race existed and had its origins in the north of Europe. It had then wandered southward and along the way had become ‘contaminated’ through intermixing with inferior short-skulled peoples, or so the theory went. Schreiner argued instead for the opposite view: that the Nordic skull type had been from the beginning a product of racial mixing. There were so many causal factors involved in the shaping of these skulls that they could ‘by no means be regarded as a genetic entity’.466 ‘It seems obvious’, he claimed, ‘that the term ˝Nordic race˝ designates only a particular phenotype within the populations which have developed in the north [of Europe] during and after the Neolithic’.467 This means that in his magnum opus on ancient Norwegian skulls, Schreiner established a purely descriptive definition of the Nordic ‘type’ and implied that craniology was not a very useful tool for the investigation of the biological origins and migrations of northern European populations.

In a lecture the same year, he summarised his view in the following way: the ‘Nordic race’ is the name for a certain body type which occurred with relative frequency among a bastard population in which, for thousands of years, mixing had taken place between different lineages, and in which the mechanisms of isolation and selection had produced a number of more or less distinctive types.468 Furthermore, according to Schreiner, the experts could only agree on one thing concerning the typical Nordic skull shape—its low cephalic index. However, it can be argued that had Kristian Emil taken his wife’s previous research seriously, he would have dismissed even the cephalic index as a relevant classification tool. The conclusion of her 1923 work on the inheritance of skull shapes was that the shape of the head, as measured by the cephalic index, was not a genetic entity but rather the product of a huge number of genetic and environmental factors.469

Despite this, neither Schreiner nor his successor at the Department of Anatomy stopped using the category ‘Nordic’ for the classification of skeletal remains from archaeological findings. When Schreiner withdrew from his position after the war, the golden age of Norwegian physical anthropology came to a close. His successor, Johan Torgersen, continued the tradition of physical anthropological research, but on a very modest scale. The department no longer initiated its own excavations and anthropology was mainly reduced to an ancillary role, subordinate to archaeology. There was a dwindling interest in general theories about the racial composition of the Norwegian people, but there was still an interest in issues relating to the Sami or Norwegian identity of archaeological findings.470 To answer such questions, ancient bones continued to be classified according to established racial categories.

Internationally, the aftermath of World War II saw a decline in scientific racism and the growth of a prevailingly anti-racist attitude within the scientific world. Two UNESCO-initiated declarations on race in the early 1950s constituted an important turning point. Leading psychologists, sociologists, and cultural and physical anthropologists were deeply involved in drafting these statements, which dismissed the idea of large, inborn psychological inequality between races and claimed that it was scientifically unsound to explain cultural differences as the product of unequal racial endowments. After an intense international debate, especially among anthropologists and geneticists, it was agreed that the concept of race should not be abandoned. Instead, race was defined as the equivalent of biological populations or ‘isolates’ that were genetically different due to two kinds of processes. On the one hand, the genetic composition of isolated populations is constantly being altered by natural selection and mutation, by fortuitous changes in gene frequency and by marriage customs. On the other hand, crossings are constantly breaking down these differentiations. The new mixed populations are in turn subjected to the same processes. Existing races are merely the result, considered at a particular moment in time, of the total effect of such processes.471

The UNESCO declarations became important reference points for the scientific debates on race in Scandinavia. When Johan Torgersen discussed race in a popular-science book in 1956, his conceptualisation seemed to echo the UNESCO declarations. He thought that race was a matter of the different frequency of genes in populations. He maintained that there were no clear boundaries between races, that race was a statistical abstraction, that intermixing between populations was common and that the racial history of humankind was characterised by changing periods of isolation and gene flow between populations, by population boundaries that were constantly coming into being and disappearing.472 In a similar vein, in an article written in 1968 on ‘The Origin of the Lapps’, Torgersen criticised the idea of a primordial Sami type. He argued that the range of variability among Sami both past and present indicated that Sami culture had arisen within biologically heterogeneous populations, and that the concept of race was problematic due to the complex relations and histories of the biological populations.

Despite these views, however, Torgersen continued to base his own anthropological investigations on established racial typologies. In a 1972 article on prehistoric races in northern Norway, he used terms such as East Baltic, Nordic and Sami, but argued that these were purely descriptive designations for skull types which could not be related to particular ethnic groups.473 It can still be asked whether these ethnically-coloured categories had an impact upon Torgersen’s historical interpretation of skeletal remains. The archaeologist Audhild Schanche has pointed out that when Torgersen classified bones into categories such as Nordic and Sami, he did not usually make it explicit that these were purely descriptive categories with no relevance to ethnicity.474 Thus, even though racial anthropology was marginalised after the war, and pre-war concepts of race were criticised, racial classifications based on pre-war typologies continued at least until the 1970s. Notwithstanding the loss of scientific credibility for the notion of a superior blond race, the Nordic type survived as a scientific concept into the post-war era.

401 Bryn’s archive: letter from the secretary of the Association, Aslaug Sverdrup, to Bryn, 1 December 1919 (letterhead of the University’s Zoological Laboratory).

402 Bryn’s archive: Mjøen to Bryn, 5 December 1920 and 29 December 1920.

403 Gunnar Broberg and Nils Roll-Hansen (eds.), Eugenics and the Welfare State (East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 1996), p. 156.

404 Bryn’s archive: Mjøen to Bryn, 10 April 1920.

405 Ibid.

406 Bryn’s archive: Mjøen to Bryn, 5 December 1920 and 29 December 1920.

407 See chapter 6.

408 Bryn’s archive: Hannesson to Bryn, 15 February 1922.

409 Bryn’s archive: Hannesson to Bryn, 4 December 1927.

410 Bryn’s archive: Mjøen to Bryn, 1926 [partly undated].

411 Stefan Kühl, Die Internationale der Rassisten (Frankfurt am Main: Campus, 1997), p. 75, Daniel J. Kevles, In the Name of Eugenics (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1986), p. 68; Elazar Barkan, The Retreat of Scientific Racism: Changing Concepts of Race in Britain and the United States between the World Wars (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), pp. 143-46, 166, 204.

412 Kühl, Die Internationale der Rassisten, pp. 76f., 103-20.

413 Bryn’s archive: K. E. Schreiner to Bryn, 7 October 1927.

414 Bryn’s archive: Mjøen to Bryn, undated letter, written after 1930.

415 Jon Alfred Mjøen, Racehygiene (Oslo: Dybwad, 1914; 2nd ed. 1938).

416 Bryn’s archive: Mjøen to Bryn, 7 July 1928 and 30 July 1928; a copy of a letter from Mjøen to C. B. Hodson, 11 July 1929.

417 Bryn’s archive: Mjøen to Bryn, 7 July 1928, 30 July 1928 and 24 December 1928.

418 Bryn’s archive: IFEO-file: a number of letters in which the organisation’s secretary complains about Bryn's failure to follow up on the IFEO's initiatives. See: 1 October 1929 and 16 June 1930. Davenport-file: Davenport to Bryn, 28 March 1930 and 26 February 1929. American Philosophical Society Library, B D27 Charles Davenport Papers: IFEO’s adm. secr. C. B. S. Hodson to Mjøen, 9 July 1931 and 22 July 1931; Hodson to Bryn, 23 July 1931; Hodson to Davenport, 26 February 1931.

419 American Philosophical Library, B D27 Charles Davenport Papers: Davenport to the General Secretaries, the International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences, 22 March 1934; Davenport to K. E. Schreiner, 4 June 1930, 26 June 1930 and 14 July 1930. The IFEO conference was held in Farnham, UK.

420 C. M. Fürst’s archive: Schreiner to Fürst, 13 February 1931.

421 Broberg and Roll-Hansen (eds.), Eugenics, pp. 91-95.

422 George L. Mosse, The Crisis of German Ideology: Intellectual Origins of the Third Reich (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1964), pp. 302ff.

423 Proctor, Robert, ‘From Anthropologie to Rassenkunde in the German Anthropological Tradition’, in George W. Stocking, Jr. (ed.), Bones, Bodies, Behavior (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1988), pp. 149; Hans F. K. Günther, Rassenkunde Europas (München: Lehmanns Verlag, 1929), pp. 344. Mosse, The Crisis of German Ideology, pp. 302ff.

424 Mosse, p. 224.

425 Robert Proctor, ‘From Anthropologie to Rassenkunde’, p. 149.

426 Ibid.; Mosse, The Crisis of German ideology, p. 224.

427 Hans Fredrik Dahl, En fører blir til (Oslo: Aschehoug, 1991), pp. 156-57.

428 Bryn’s archive: Günther to Bryn, 2 December 1923: ‘[...] der mir bei Übersendung sehr gütig über mein Buch geschrieben hat [...] den er nach Weihnachten besprechen will’. Günther’s Racial Science of the German People was published in 1922 and was his first book on anthropology. He was, therefore, most likely referring to this work.

429 Bryn’s archive: Günther to Bryn, 11 February 1924. Günther describes a visit to Schreiner in Kristiania: ‘Der uns sehr liebenswürdig aufgenimen hat und mir sehr Wichtige Dinge geseigt und berichttet hat, Ich freue mich sehr ihn kennen gelernt zu haben’; Günther to Bryn: postcards, 1924.

430 Bryn’s archive: Bryn’s review of Günther’s Racial Science of the German People; newspaper clippings of Trondhjems adresseavis, 22 March 1924.

431 Bryn’s archive: Mjøen to Bryn, undated letter, written after 1930.

432 Bryn’s archive: Günther to Bryn, 16 January 1932.

433 Nicola Karcher, 'Schirmorganisation der Nordischen Bewegung: Der Nordische Ring und seine Repräsentanten in Norwegen', NORDEUROPAforum, Vol. 19, no. 1 (2009), p. 15.

434 Ibid., pp. 19-21.

435 Bryn’s archive: Konopacki-Konopath to Bryn, 22 December 1926. This was a standard letter from Hanno Konopacki-Konopath urging the recipient to join the newly-established Nordischer Ring. In Bryn’s archive there is also a confidential circular to members, from which one can assume that he most likely became a member. See also Karcher, 'Schirmorganisation der Nordischen Bewegung'.

436 Wilhelm E. Mühlmann, Geschichte der Anthropologie (Frankfurt am Main: Athenäum Verlag, 1968), p. 189.

437 Proctor, ‘From Anthropologie to Rassenkunde’, pp. 149, 158-61.

438 Terje Emberland and Matthew Kott, Himmlers Norge. Nordmenn i det storgermanske prosjekt (Oslo: Aschehoug, 2012), pp. 56-90.

439 Terje Emberland, Religion og rase, Nyhedenskap og nazisme i Norge 1933-1945 (Oslo: Humanist, 2003), pp. 122-33.

440 Hans Fredrik Dahl, En fører blir til (Oslo: Aschehoug, 1991), p. 156.

441 Bryn’s archive: Günther to Bryn, 16 January 1932.

442 The Ekstrabladet of 3 November 1931 contained an editorial entitled 'Ekstrabladet Will from Now on Be an Organ for Norsk Folkereisning (Ekstrabladet vil nu bli organ for Norsk Folkereisning)'. The statute of the organisation was published in the same issue. The newspaper came out once a week and printed, among other things, a number of articles signed by Adolf Hitler.

443 Karcher, 'Schirmorganisation der Nordischen Bewegung‘, pp. 15, 28.

444 Bryn’s archive: Günther to Bryn, 24 October 1929. Günther commented on Kristian Emil Schreiner’s behaviour towards Bryn: ‘Dass doch so oft die Universitätsmenschen sich so hinterhältig benehmen’.

445 Bryn’s archive: Günther to Bryn, 24 October 1929.

446 Per Holck, Den fysiske antropologi i Norge. Fra anatomisk institutts historie 1815-1990 (Oslo: Anatomisk institutt, University of Oslo, 1990), p. 95ff.: ‘Bibliography of the Works of Norwegian Physical Anthropologists’.

447 Bryn’s archive: clipping from The Quarterly Review of Biology [n. d.].

448 Bryn’s archive: Egon von Eickstedt to Bryn, 25 June 1929.

449 Bryn’s archive: Egon von Eickstedt to Bryn, 24 September 1929.

450 Bryn’s archive: Egon von Eickstedt til Bryn, 25 December 1929.

451 Bryn’s archive: Josef Weininger to Bryn, 16 February 1931.

452 The debate led to an extensive correspondence between Bryn and his adversaries and allies. Bryn’s archive: Günther to Bryn, 1 October 1929, 16 March 1931, 3 January 1932, 16 Janaury 1932; K. Saller to Bryn, 27 October 1930; Bryn to W. Scheidt, 28 February 1931; W. Scheidt to Bryn, 5 March 1931, 19 November 1931; H. K. Konnopath to Bryn, 3 March 1932; B. K. Schultz to Bryn, 1 January 1932, etc.

453 Karl Saller, ‘Die entstehung der "nordischen Rasse"', Zeitschrift für die gesamte anatomie/Zeitschrift für anatomie und entwicklungsgeschichte, Vol. 83, no. 4 (1927), pp. 411-590. Bryn’s archive: Prof. Schroller (editor of Antropos) to Halfdan Bryn, 20 January 1926.

454 Bryn’s archive: Prof. Schroller to Bryn, 20 January 1926.

455 Ibid.

456 Proctor, ‘From Anthropologie to Rassenkunde’, p. 165.

457 Bryn’s archive: Ministerialrat Hanno Konopacki-Konopath to Bryn, 3 March 1932; Bruno Kurt Schultz to Bryn, 29 January 1932; Günther to Bryn, 3 January 1932, 16 January 1932, 16 March 1931, 1 October 1929.

458 Walter Scheidt, ‘Die rassischen Verhältnisse in Nordeuropa nach dem gegenwärtigen Stand der Forschung‘, Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie, Vol. 28, nos. 1/2 (1930), pp. 1-197.

459 Saller, ‘Die Entstehung der “nordischen Rasse”’.

460 The data were published in Walter Scheidt's Die rassischen verhältnisse in Nordeuropa (Stuttgart: Schweizerbart, 1930) to support his argument against the existing notion of the Nordic race. The book is referred to extensively in the correspondance between Bryn and Günther, and between Bryn and Scheidt. Bryn’s archive: Bryn to Scheidt 28 February 1932, 5 March 1931, 19 November 1931; Günther to Bryn, 3 January 1932, 16 January 1932, 16 March 1931, 1 October 1929. My account is based on these letters.

461 Halfdan Bryn, Norske folketyper, Det kgl.n.Vid.selsk. Skr. 1933 (Trondheim: Brun, 1934).

462 Bryn’s archive: Saxlund to Bryn, 3 December 1925 and 5 January 1926.

463 Sigurd Saxlund, Rase og kultur. Raseblandingens følger (Oslo: Stenersen, 1940).

464 K. E. Schreiner, Crania norvegica I (Oslo: ISKF/Aschehoug, 1939), pp. 1, 196-97.

465 Jorunn Sem Fure, Universitetet i kamp: 1940-1945 (Oslo: Vidarforlaget, 2007), pp. 151f. and 176f.

466 K. E. Schreiner, Crania norvegica II (Oslo: ISKF/Aschehoug 1946), p. 63.

467 Ibid., p. 169.

468 K. E. Schreiner, ‘Hva er nordisk rase?’, Forhandlinger, Det norske vitenskapsakademi (Oslo: [n. pub.], 1946), and Crania norvegica II.

469 Alette Schreiner, ‘Zur erblichkeit der Kopfform’, Genetica, Vol. 5, nos. 5-6 (1923), p. 445.

470 Audhild Schancke, ‘Samiske hodeskaller og den antropologiske raseforskningen i Norge’, appendix to I. Lønnig, M. Guttor, J. Holme, et al. (eds.), Innstilling fra Utvalg for vurdering av retningslinjer for bruk og forvalting av skjelettmateriale ved Anatomisk institutt (Oslo: University of Oslo, 1998), p. 6.

471 UNESCO, Statement on the Nature of Race and Race Differences (Paris: UNESCO, 1951), http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0015/001577/157730eb.pdf

472 Johan Torgersen, Mennesket. Vidunder og problembarn i livets historie (Oslo: Aschehoug, 1956), pp. 130-36.

473 Schancke, ‘Samiske hodeskaller’, p. 7.

474 Ibid., p. 8.