1. The Origin of the Long-Skulled Germanic Race

The early 1840s were a decisive period in the rise of the concept of a Germanic race. During that decade, Swedish anatomist Anders Retzius launched the cephalic index, a new method for identifying races. On the basis of differences in head measurements, he split humankind into two basic categories: the short-skulled brachycephalics and the long-skulled dolichocephalics. By combining these two categories with a set of anatomical and geographical criteria, he developed a system of racial classification that made it possible to divide Europeans into a number of racial types and to establish the scientific concept of a long-skulled, blond Germanic race. Retzius’ system became an important starting point for decades of research and debate on the racial divisions of Europe. However, Retzius’ work was based on already existing scholarly traditions; he was not the first person in the history of science to create a racial classification system, and he invented neither the idea of the Germanics nor the concept of race itself. Thus, in order to understand the background to Retzius’ innovations, we first need to take a brief look at the rise of racial science in the eighteenth century.

The rise of racial science

Scientific notions of race arose in parallel with European colonial expansion, encounters with non-European peoples and the emergence of the transatlantic slave trade. These encounters with other peoples and other continents provoked Enlightenment scholars’ interest in the origins and causes of human variation, and sparked the drive to classify humankind into different racial groups. This scientific enterprise was woven into ongoing controversies regarding the legitimacy of slavery and into theological debates over the creation of man.

One of the most influential works from this period was De generis humani varietate native, published in the late eighteenth century by the German anatomist and natural historian Johan Friedrich Blumenbach, who believed that racial differences had arisen through adaptation to different environments. Blumenbach argued that the human species had originated in the Caucasus region and was perfectly adapted to the Caucasian climate. Accordingly, the so-called Caucasian race (which included people from Europe, the Middle East and North Africa) was the original, and therefore superior, type of man. The inferior races—the American, Mongolian, Malayan and Ethiopian—had emerged through adaptation to less favourable environments.8 By asserting humanity’s common origin, Blumenbach’s scientific view accorded with traditional interpretations of the biblical account of creation and the descent of all humankind from Adam and Eve. The idea that all races belong to one species has been labelled ‘monogenism’, and has its counterpart in ‘polygenism’, the idea that God created a number of fixed human species. Monogenists and polygenists agreed that the Europeans were more civilised and had a greater moral worth than other races, but disagreed on the significance of the differences between the various races. Polygenists argued that Africans were inherently inferior, a view that often led to the conclusion that they were natural-born slaves. Monogenists, on the other hand, maintained that racial inferiority was caused by poor cultural or environmental conditions, climate or food, and often claimed this effect could be reversed if Africans were exposed to a more stimulating environment. Educate the slaves and set them free, argued the abolitionists, and their descendants will become like us.9

Racial ethnology

Debates over monogenism and polygenism continued into the nineteenth century. However, while monogenism had been the dominant theory in the eighteenth century, by the 1840s the idea of fixed, unchangeable racial differences was gaining currency. Furthermore, while the Enlightenment discourse on race had been intertwined with controversies around slavery and colonialism, and had focused on the racial distinctions between Europeans and the rest of mankind, it was now increasingly being argued that race was relevant to national differences within Europe. The rising interest in the racial classification of Europeans was fuelled by an upsurge of nationalism in the 1830s and 1840s. Following the Napoleonic Wars, Europe was comprised of a number of multi-ethnic states (e.g. Russia, Austria and the Ottoman Empire) and various ethnic groups divided into small states (e.g. what would later become Italy and Germany). All over Europe, there was a growing political impetus to adjust state borders in accordance with national boundaries and the demands of national minorities. States competed for power and national honour, and there was a great deal of interest in cultural identity and roots. This in turn led to rising scientific interest in the origins and ancient history of the European nations.

From the early decades of the nineteenth century, linguists took the lead in exploring these issues. Around 1800, they recognised the existence of a historical connection between Sanskrit and modern European languages, and they developed the theory of an extinct Indo-European language. This led to the evolution of comparative Indo-European linguistics as a prestigious scientific discipline that aimed to trace the lineages of the European languages back to their common origin. It was commonly assumed that the various Indo-European languages had spread through human migration and that successive waves of migration to Europe had given rise to the European peoples. By the 1840s, the new linguistic theories were complemented by anatomically-based concepts of race, resulting in a new type of racial science and in attempts to establish a new academic discipline under the name of ethnology.

In 1843 the Ethnological Society of London was founded under the leadership of physician and linguist James Cowles Prichard, a Christian humanist and monogenist, who based his research on the biblical account of creation. Employing linguistic methods, and, to a lesser degree, anatomical comparison, Prichard classified humans into groups, mapped their relatedness and tried to trace them back to a common origin. He ranked people according to a hierarchy of intellectual and moral progress, but believed these differences were the product of variations in culture, environment and way of life. He rejected the existence of insurmountable barriers to the improvement of the so-called inferior races and used this as an argument against slavery. Prichard advocated a humanist and paternalist colonial policy aimed at spreading ‘civilisation’ and the Christian gospel to the world. Internationally recognised, Prichard’s school of ethnology was widely supported in Britain but met with challenges from advocates of polygenism, both in his home country and abroad.10 One major challenge came from the U.S., where physician Samuel J. Morton pioneered a polygenic strand of ethnology in the 1830s. Morton collected a huge number of crania which he subjected to anatomical comparison in order to classify races, explore the history of humankind and study correlations between brain size and racial superiority. He subsequently founded an American school of ethnology, which his followers developed into a tool for the legitimisation of slavery and racial segregation.11

The founder of the Société Ethnologique de Paris (1839), British-French physiologist William Edwards, was also opposed to monogenism. Edwards believed that the main aim of ethnology was to explore the origin and identity of the European nations. He proposed that humankind consisted of a number of largely immutable racial types, each equipped with certain innate mental properties, and that the uneven distribution of these racial types could explain national and regional differences in traditions, behaviour and levels of civilisation. Edwards was mainly interested in the origin and history of the French. Many historians saw the French as a mix of ethnic elements with different historical and social roles. While the French commoners were thought to have their roots in an indigenous Celtic population, the aristocracy stemmed from Frankish warriors who had established themselves as a ruling caste during the Migration Period. Edwards set out to prove that these different ethnic and social groups were in fact biologically distinct races with inborn psychological and intellectual differences.12

Craniology and the three-age system

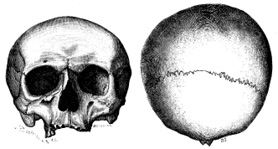

The most influential individual involved in the division of Europeans into races was the Swedish anatomist Anders Retzius. Around 1840, he put forward a method of racial classification that divided humans into two basic categories: the dolichocephalics, with long skulls, as measured from the forehead to the occiput, and the brachycephalics, who had shorter, rounder skulls (see Fig. 1). By combining these two categories with other anatomic and geographic criteria, Retzius created a system of racial types that coincided with linguistically defined peoples, such as the Celts, the Slavs and the Germanics, which he then ranked in terms of superiority with the Germanics at the top. The key idea in Retzius’ system was the cephalic index, which referred to the ratio of the breadth to the length of the skull and would become a widely used criterion for racial classification in the decades that followed.

Fig. 1 Brachycephalic or short skull (top), dolichocephalic or long skull (bottom).

Although Retzius was a comparative anatomist, his research questions came from archaeology and comparative linguistics, and the method he launched became an important tool for combining archaeological and linguistic knowledge. By comparing skulls from present-day populations with skulls found at archaeological excavation sites, Retzius claimed he could demonstrate racial continuity or discontinuity between past and present populations. Moreover, he hypothesised that he could clarify the ethnic identity of the inhabitants of the prehistoric settlements and link archaeological evidence to linguistic theories about past migrations and settlements of ethnic groups. It is no coincidence that it was a Scandinavian scholar who devised this technique. Retzius developed his method in order to solve archaeological and linguistic questions about Scandinavian prehistory, and at that time Scandinavian scholars were at the forefront of research in both archaeology and linguistics.

The Dane Rasmus Rask was one of the most influential linguists of his time. Along with his German colleague Jacob Grimm, he helped to establish what later came to be known as ‘sound laws’: fixed ‘rules’ that regulate the historical transformation of a language’s sound system. The discovery of such law-like regularities made it possible to study the development of languages in times pre-dating all written sources, which was to prove important for the rise of comparative Indo-European linguistics. An important breakthrough in this context was ‘Grimm’s Law’—also called ‘Rask’s Rule’ or the ‘First Germanic Sound Shift’—which described a series of consonant changes that in the distant past had helped to split the proto-Germanic language from the other Indo-European languages.13

Scandinavians played an even more crucial role in the field of archaeology. Indeed, it was Danish archaeologist Christian Jürgensen Thomsen who developed the ground-breaking three-age system that divided prehistory into the Stone Age, the Bronze Age and the Iron Age. Prior to this other scholars had proposed that prehistoric cultures had advanced from an age of stone tools to ages of bronze and iron tools. However, when Thomsen began organising the display of antiquities at the new National Museum of Denmark in the early 1820s, no methods existed for dating artefacts according to such a scheme. Thomsen began to group all artefacts that were found together at the same excavation site and which could be assumed to stem from the same period. On the basis of this, he developed a comparative typology that made it possible to also date artefacts that were not part of such closed finds. This new method opened up opportunities for exploring the time period that lay beyond the advent of writing—an important prerequisite for the rise of a concept of ‘prehistory’ and of archaeology as an autonomous scientific discipline.14

Even if the three-age system implies that all human societies evolved along a common trajectory, Danish archaeologists did not believe that the development from the Stone Age to the Iron Age had taken place within one and the same Scandinavian population. Instead, they assumed that each ‘age’ was introduced through the immigration of a new group of people and sought to prove this by making their interpretations of the archaeological evidence fit already-existing linguistic and historical accounts of the settling of Scandinavia. One such account had already been put forward in the eighteenth century by Peter Fredrik Suhm and Gerhard Schøning, who were, respectively, the leading historians in Denmark and Norway. Their account was based on the then commonly-held view that the main human groupings stemmed from Noah’s sons Shem, Ham and Japheth, each of whose descendants had peopled their own continents, and that the linguistic division of humankind had arisen when God confused the languages in order to prevent the completion of the Tower of Babel. Basing themselves on the Bible, logical reasoning, linguistic arguments and interpretations of classical literature and Norse mythology, Suhm and Schøning tried to reconstruct the route that the forefathers of the Scandinavians and Germans had followed into Scandinavia from their assumed place of origin somewhere north of the Black Sea.15

In 1818, this theory was further elaborated by Rasmus Rask, who dismissed its biblical underpinning but claimed to have detected a series of Scandinavian-related languages along the route that the Scandinavian and German forefathers were assumed to have followed. From the Black Sea region, these groups were thought to have wandered northwards into present-day Russia. There, the Scandinavians had split off from the Germans before moving further north of the Gulf of Bothnia and into the Scandinavian Peninsula, where they encountered an indigenous population of Finno-Ugrians, the forefathers of the Sami, the indigenous people of northern Scandinavia. The three-age theory was initially invented in an attempt to fit Danish archaeological findings into this account, the idea being that the three archaeological ages corresponded to the periods in which three linguistically different peoples settled in Scandinavia.16

Rask, Schöning and Suhm’s migration theory met with increasing criticism in the 1830s, and the subsequent debate provided an important background for the introduction of craniology as a method for determining the ethnic identity of the peoples that had inhabited Stone Age, Bronze Age and Iron Age settlements. The publication in 1838-1843 of a two-volume work by Swedish zoologist and ethnographer Sven Nilsson was a seminal event. Nilsson compared finds from the Scandinavian Stone Age and Bronze Age with ethnographic observations on the tools and habits of contemporary ‘savages’ and ‘nomads’, and pointed out that the culture of the ‘primitive’ inhabitants of ancient Scandinavia resembled the culture of contemporary ‘primitive’ tribes. He proposed that the cultural and social development of all peoples pass through the same three stages of savages, nomads and agriculturalists, and that these stages concurred with the three archaeological ages. Somewhat paradoxically, however, Nilsson also argued that cultural progress in Scandinavian prehistory had been driven by the successive immigrations of increasingly more civilised peoples: Finno-Ugrian savages in the Stone Age, Celtic nomads in the Bronze Age and Germanic farmers in the Iron Age.17 As evidence for this interconnection between human migrations, the advent of archaeological ages and stages of socio-economic development, Nilsson pointed to anatomical similarities and differences between human skulls. He compared skulls from three Danish Stone Age finds with the skulls of two recently deceased Sami and argued that they all had a typically round shape. To assign the Bronze Age to the Celts, Nilsson compared a drawing of a Danish Bronze Age skull with a drawing of the skull of a Scottish Highlander and a plaster cast of a supposedly Celtic skull kept at St. Thomas’ Hospital in London. He concluded that both the Sami and the Celtic skulls were different from the typical Iron Age Germanic skull.18

To explore the racial connection between the assumed Germanic Iron Age population and the contemporary Swedish population, Nilsson asked his friend Anders Retzius for help. At that time Retzius held a leading position at the Carolinska Institutet in Stockholm, a key institution for medical education and research, and he was able to compare 200-300 skulls of recently deceased Swedes. After submitting these to several rounds of examinations and selection, he selected the five crania that he deemed most representative, and, based on this sample, provided a detailed description of the typical Swedish skull, concluding that it was identical to Nilsson’s Iron Age skull.19

Craniology and the brain

Retzius and fellow ethnologists such as Edwards and Morton took it as their task not only to identify races but also to rank these races in a hierarchy of intellectual ability and moral worth. They did so mainly by comparing skulls, as they believed that intellectual capacity was correlated to the size and shape of the skull. This assumption was based on contemporary theories of brain anatomy, and can partly be attributed to the theories of the mind and the brain that the Austrian physician and comparative anatomist Franz Joseph Gall put forward around 1800. Gall proposed that all animal species could be ranked in a hierarchy according to the complexity of their nervous systems. At the bottom of the hierarchy were the simplest animals (like jellyfish) that were only equipped with scattered nerves. In more advanced animals, all nerves were linked through the spinal cord, and among the most advanced animals, the end of the spinal cord was converted into a brain. Gall therefore saw the spinal cord as the core element of the nervous system, from which the brain had emerged.20

These observations provided the basis for a theory of the brain as a set of mental faculties. From the simplest organisms up to man, there is a steady increase in the number of mental faculties, from the most basic functions that are common to all species (such as the sex drive) up to the highest faculties (such as wisdom and compassion), which man alone possessed. According to Gall, each mental function was localised in a certain organ in the brain. Therefore, the relative strength of different mental faculties was related to the shape of the brain, and indirectly to the shape of the skull.21 From this starting point, Gall and his followers developed a science of the relationship between psychological characteristics and the shape of the skull which eventually became relatively well-known to the educated public as phrenology.

At the same time as phrenology evolved into a popular movement, particularly in England and the U.S., it also met with increasing opposition from scientists. By the 1840s it was to a large extent scientifically discredited, but, despite this, Gall’s basic approach to brain anatomy had a lasting scientific impact. Both the notion of a hierarchy of cerebral development and the idea that the shapes of the brain and the skull are correlated with intellectual ability proved fundamental to the rise of a craniological approach to race typology.

In an 1848 lecture, Retzius praised Gall’s basic approach to brain anatomy and hailed him as the first to ascertain that the brain was a transformed part of the spinal cord. However, Retzius also criticised Gall for having misunderstood how this transformation took place. Gall had proposed that the frontal lobes were the final stage in the development of the central nervous system and thus the seat of the higher mental faculties. According to Retzius, the situation was the other way around: during the growth of the human embryo, the frontal brain lobes developed first, then came the parietal lobes and finally the occipital. This matched the hierarchy of the nervous system in vertebrates, from the simplest to the most complex forms: fishes, birds and amphibians only have frontal lobes, whereas mammals have both frontal and parietal lobes, and only human beings and a few other mammals have frontal, parietal and occipital lobes. The posterior part of the brain should therefore be considered the final stage in the development of the brain, the seat of the superior mental faculties.22

According to Retzius, not only the different mammal species but also the various human races represented different levels of cerebral development and could be ranked according to the relative development of the posterior part of their brains. When launching his racial classification system in 1843, Retzius proposed that the typically long-skulled Swedish brain was characterised by a significant elongation of the occipital lobe of the cerebrum, which extended well beyond the cerebellum. This was in contrast to the more round-headed Slavic peoples and particularly the even more round-headed Lapps, whose occipital lobes were so small that they could hardly cover the cerebellum. It goes without saying that while Retzius located the most superior intellectual faculties in the occipital lobe, he saw the cerebellum as the seat of most basic mental functions.23 According to Retzius, it was a ‘universally acknowledged fact’ that Celtic and Germanic peoples possess the strongest intellectual faculties. This corresponded to their low, narrow and long skulls, with their strongly protruding occipital, and was in contrast to the inferior Slavs and Lapps with their broad skulls and weakly developed occiput.24

Retzius’ hierarchical classification was based on the assumption that there was a correlation between race, language, intellectual ability, brain anatomy and cultural development. He claimed that his comparative-anatomical theory of the development of the central nervous system was confirmed by the distribution of skull shapes between ethnic groups. Short-skulled peoples had more primitive brains and more primitive cultures than long-skulled peoples. This notion fit Nilsson’s theory of cultural development from savage via nomad to farmer. It also fit the archaeological theory of the three ages and the linguistic theory of Finno-Ugrian Stone Age aborigines being replaced by more advanced Indo-European invaders.

The success of the Germanic dolichocephalics

The Scandinavian migration theories were not developed in a vacuum, and it is important to understand the interconnections and patterns of influence between the Scandinavian theories and those developed abroad. Suhm, Schøning, Rask, Nilsson and Retzius participated in transnational debates and tried to gain acceptance for their theories from the international scholarly community. Their ideas on the origins of the Scandinavian nations formed part of more general accounts of the origin and development of humankind and the history of the European nations.

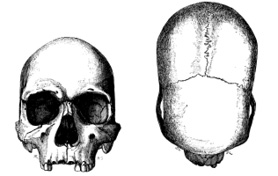

Retzius and Nilsson’s migration theory was not only an account of the origin of the Swedes, it was also a grand theory about the rise of European civilisation. They proposed that the Sami and the Basques were the descendants of inferior Stone Age peoples that had originally inhabited all of Europe. These short-skulled autochthones had later been overrun by successive waves of Indo-European invaders who brought increased levels of civilisation to Europe: the Celts introduced the Bronze Age, and the Germanics the Iron Age. Thus, the growth of European civilisation was explained by the successive invasion of races with increasingly advanced brains.25 Retzius’ views were extraordinarily influential (see Fig. 2). The racial-succession scheme shaped linguistic, archaeological and ethnological debates on European prehistory from the 1840s to the 1860s,26 and the system of classifying skulls and human races into dolichocephalics and brachycephalics had an even greater and more long-lasting impact. Indeed, the cephalic index became a key factor in most of the numerous racial typologies that were put forward by European scientists over the next 100 years.

Fig. 2 William Z. Ripley’s racial classification scheme in The Races of Europe (1899). Ripley was influenced by Retzius’ work; his blue-eyed, blond and tall ‘Teutonic race’ mirrors Retzius’ notion of the Germanic race.

There are many explanations for this success. Retzius’ simple craniological method was an easy and convenient way of comparing skulls and classifying races, and his settlement theory fit neatly into already established narratives of national origin. Various nations claimed Celtic, Slavic and Germanic origins, and Retzius’ method seemed to be a highly applicable scientific tool for exploring these racial roots. Furthermore, Retzius’ racial-succession scheme assigned the European races different roles in the rise of European civilisation and arranged them in a hierarchy that mirrored the existing power relations and differences in technological and economic development in Europe. Historian Richard McMahon has proposed that nineteenth-century racial classifications of Europeans were shaped by the continuous competition between scholars who wanted to demonstrate the racial superiority and historical virtues of their own national groups. Since the northern European countries were ahead of the rest of Europe in terms of industrial progress and colonial expansion, their narratives of Germanic superiority achieved a dominant international currency.27

Notions of Germanic national roots had been around since at least the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and were initially based on the descriptions of ancient peoples in classical literature. Germania by the Roman historian Tacitus was a principal source of these ideas. In this text, the virtuous, free and unspoiled ‘Germans’ were held up in contrast to the decadent Romans. Tacitus’ descriptions influenced national narratives in Scandinavia, the Netherlands, Germany and England, where the birth of the nation became associated with the Germanic past and the idea of ‘freedom’ as a specifically Germanic virtue.

The birth of German nationhood was often seen as the outcome of the epic Germanic victory over the Romans in the Teutoburger Forest in 9 AD that put an end to Roman expansion into Germanic lands. This narrative became a key element in the rising German nationalism after the end of the Napoleonic Wars: the idea of a common ‘Germanic’ past helped legitimise efforts to unify Germany and, following unification in 1871, highlighted the German Empire at the expense of its neighbouring rivals, ‘Celtic’ France and the ‘Slavic’ Russian Empire. The idea of the Germanic race even legitimised Pan-Germanism, which arose in response to its ideological twin sister Pan-Slavism and aimed to unify all of German-speaking Europe. The valorisation of a Germanic past often went hand in hand with a condescending attitude towards the Slavic and Celtic races.

An English penchant for the Germanics dates back to the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. English national roots were sought in the Anglo-Saxons, a group of Germanic tribes that settled in England when the Roman Empire collapsed and established a kingdom characterised by ‘free’ governmental institutions. American colonists also inherited the myth of a golden Anglo-Saxon past, and the notion of a Germanic sense of freedom was even used to justify the American War of Independence. According to the historian Reginald Horsman, however, the 1840s saw the breakthrough of a new type of Anglo-Saxon ideology, combining those well-established ideas of Anglo-Saxon freedom with new concepts of racial superiority. The Anglo-Saxons were now portrayed as a particularly superior branch of the Germanic race and were often contrasted with their inferior counterparts, the Celts, and especially the Irish Celts.28

Even in France, the Germanic peoples played an important role in traditional accounts of national origin, as the roots of royal dynasties were traced back to the invasion of Germanic warriors in the Age of Migration. In French historiography, it was conventional to describe French commoners as descendants of an indigenous Gallic (Celtic) population, while the aristocracy were seen as descendants of the Frankish (i.e. Germanic) warriors who had invaded the country in the fifth century. In the 1820s and 1830s, the influential historians Amédée and Augustin Thierry transformed this idea into a theory of two hostile nations, of which one (the descendants of Frankish conquerors) exerted an illegitimate dominance over the other (the Celtic Gauls). The Thierry brothers, however, viewed the Celtic race, not the Germanic Franks, as the true core of the French people. This idea became dominant from the 1830s onwards, leading to a tradition of veneration of the Celts among the French and providing an important vantage point for William Edwards’ attempts to establish a scientific ‘ethnology’ in the 1840s. Edwards’ theory of stable and unchanging races offered a biological explanation for the Thierry brothers’ doctrine: the Celtic people and the Frankish aristocracy belonged to different races with different inborn characteristics undiluted by centuries of cohabitation.29

According to McMahon, scholars from non-Germanic nations tended not to question the prevailing account of Germanic virtues, nor did they develop completely alternative narratives. Instead, the Slavic, Celtic or Latin races were defined in opposition to the Germanics, and the disparaging stereotypes of these races were given new interpretations. Rather than heroic, freedom-loving and aristocratic warriors, the Germanics could be portrayed as brutal tyrants and oppressors. Polish scholars, for instance, preferred to portray the Slavs as a peace-loving, hard-working and rooted people who had survived Germanic plunder and violence. Similar stereotypes of peaceful, artistic, humble and oppressed Celts existed in Ireland and France, and were contrasted with the image of brutal warrior-like Germanics.30

We have thus seen that the 1830s and 1840s witnessed the breakthrough of a scientific concept of ‘the Germanic race’, and that the idea of Germanic racial superiority was intertwined with a number of national ideologies, including those of the most powerful nations in the world. But what of Norway, we might ask, one of the smallest and least powerful of the Germanic-speaking nations? What impact did the idea of a superior Germanic race have on the national identity of Norwegians? We will now turn our attention to Norway and attempt to answer these questions.

8 See, for example, Timothy Lenoir, ‘Kant, Blumenbach, and Vital Materialism in German Biology’, Isis, Vol. 71, no. 1 (1980), pp. 77-108. Blumenbach’s book was published in a number of different editions between 1775 and 1795. This account refers to the last edition.

9 See, for example, Nicholas Hudson, ‘From “Nation” to “Race”: The Origin of Racial Classification in Eighteenth-Century Thought’, Eighteenth-Century Studies, Vol. 29, no. 3 (1996), pp. 247-64; Snait B. Gissis, ‘Visualizing “Race” in the Eighteenth Century’, Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences, Vol. 41, no. 1 (2011), pp. 41-103; Ann Thomsen, ‘Issues at Stake in Eighteenth-Century Racial Classification’, Cromohs, no. 8 (2003), pp. 1-20, http://www.cromohs.unifi.it

10 H. F. Augstein, ‘Aspects of Philology and Racial Theory in Nineteenth-Century Celticism: The Case of James Cowles Prichard’, Journal of European Studies, Vol. 28, no. 4 (1998), pp. 355-71; James Cowles Prichard, Researches into the Physical History of Mankind, Vol. 2 (London: Sherwood, Gilbert, and Piper, 1837).

11 C. Loring Brace, Race Is a Four-Letter Word: The Genesis of the Concept (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 85ff; Ann Fabian, The Skull Collectors. Race, Science and America’s Unburied Dead (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2010).

12 Claude Blanckaert, ‘On the Origins of French Ethnology: William Edwards and the Doctrine of Race’, in George W. Stocking, Jr., ed., Bones, Bodies, Behavior: Essays on Biological Anthropology (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1988), pp. 18-50.

13 Even Hovdhaugen et al., The History of Linguistics in the Nordic Countries (Helsinki: Societas Scientiarum Fennica, 2000), pp. 159-72.

14 Peter Rowley-Conwy, From Genesis to Prehistory: The Archaeological Three Age System and its Contested Reception in Denmark, Britain, and Ireland (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007); Bruce Trigger, A History of Archaeological Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), pp. 73-87.

15 Stian Larsen, Med dragning mot nord. Gerhard Schøning som historiker (Master’s thesis, University of Tromsø, 1999); Rowley-Conwy, From Genesis to Prehistory, pp. 22-29.

16 Rowley-Conwy, From Genesis to Prehistory, pp. 37-42.

17 Sven Nilsson, Skandinaviska Nordens Ur-Invånare. Ett försök i komparativa Ethnografien och ett Bidrag til Menniskoslägtets utvecklings historia (Lund: Berlingska Boktryckeriet, 1838-1843). Nilsson had a forerunner. In 1837, Danish physiologist Daniel Esricht published the work Om Hovedskallerne. Beenradene i vore gamle Gravhöie (Copenhagen: [n. pub.], 1837), in which he argued that skulls from three Stone Age finds belonged to ‘a noble tribe of the Caucasian race’.

18 Nilsson, Skandinaviska Nordens Ur-Invånare, ett forsök i komparativa Ethnografien och ett bidrag til menniskoslägtets utvecklings historia, Vol. 1 (Stockholm: P. A. Norstedt & Söner, 1866), pp. 100-06.

19 Anders Retzius, Om formen af nordboernes cranier. Aftryckt ur Förhandl. vid Naturforskarnes Möte i Stockholm år 1842 (Stockholm: P. A. Norstedt, 1843).

20 Christian Heinrich Ernst Bischoff and Christoph Wilhelm Hufeland, Some Account of Dr. Gall’s New Theory of Physiognomy Founded upon the Anatomy and Physiology of the Brain (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, 1807), pp. 15-16, http://bit.ly/1HSosvI; S. Zola-Morgan, ‘Localization of Brain Function: The Legacy of Franz Joseph Gall (1758-1828)’, Annual Review of Neuroscience, Vol. 18, no. 1 (1995), pp. 359-83 (pp. 376ff.); Donald Simpson, ‘Phrenology and the Neurosciences: Contributions of F. J. Gall and J. G. Spurzheim’, ANZ Journal of Surgery, Vol. 75, no. 6 (2005), pp. 475-82.

21 Bischoff and Hufeland, Some Account of Dr Gall’s New Theory, pp. 1-16; Simpson, ‘Phrenology and the Neurosciences’; Zola-Morgan, 'Localization of Brain Function', pp. 376ff.

22 Anders Retzius, Phrénologien bedömd från en anatomisk ståndpunkt. Föredrag hållet vid Skandinaviska Naturforskare-Sällskapets möte i Köpenhamn i Juli 1847 (Copenhagen: Trier, 1848), p. 187.

23 Anders Retzius, Om formen af nordboernes cranier, p. 2.

24 Retzius, Phrénologien, p. 187ff. Idem, Om formen af nordboernes cranier, p. 2.

25 Anders Retzius, Ethnologische Schriften von Anders Retzius. Nach dem Tode des Verfassers gesammelt (Stockholm: P. A. Norstedt & Soner, 1864).

26 See, for example, Richard McMahon, The Races of Europe: Anthropological Race Classification of Europeans 1839-1939 (Ph.D. thesis, European University Institute, 2007).

27 Richard McMahon, ‘Anthropological Race Psychology 1820-1945: A Common European System of Ethnic Identity Narratives’, Nations and Nationalism, Vol. 15, no. 4 (2009), pp. 575-96.

28 Reginald Horsman, ‘Origins of Racial Anglo-Saxonism in Great Britain before 1850’, Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 37, no. 3 (1976), pp. 387-410. See also idem, Race and Manifest Destiny: The Origins of American Racial Anglo-Saxonism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981), p. 81.

29 Blanckaert, ‘On the Origins of French Ethnology’, pp. 21-22.

30 McMahon, ‘Anthropological Race Psychology’, p. 587.