3. The Germanic Race and Norwegian Anthropology, 1880-1910

The Parisian Society of Anthropology was founded in 1859, which was also the year that Darwin published On the Origin of Species. Soon after, similar institutions were established all over Europe. These institutions became important arenas for research and debate on the origin and evolution of the human species and gave rise to the new discipline of anthropology, which replaced ‘ethnology’ as the most important academic discipline for research on race and human variation.

The main founding father of anthropology was the French anatomist Paul Broca, who initiated the establishment of a number of anthropological institutions and helped turn Paris into an international centre for anthropological research and education. Anthropology, as promoted by Broca, bore many similarities to the ethnology of the mid-nineteenth century. The anthropologists generally assumed that there was a relationship between intellectual ability and the size and shape of the brain and skull. Craniology was the preferred method for classifying and ranking inferior and superior races, and the cephalic index was retained and elaborated upon as an important criterion for classification. The Germanic race was still blond and long-skulled, and debates on racial types and European prehistory were still interwoven with struggles surrounding national narratives and national identities.64

However, there were also some important differences between the ethnology of the 1840s and the anthropology of the 1860s and later decades. Broca and his French colleagues took the lead in developing craniology and racial typology into a quantitative science. They launched new and more rigorous measuring techniques and instruments, undertook increasingly comprehensive studies of living populations and skeletal remains, and adopted increasingly advanced statistical methods to analyse the ever-expanding volume of data on anatomical variation between human groups. In addition, Retzius’ scheme of racial succession, which had held a dominant position since the 1840s, was debunked in the 1860s. Employing a range of quantitative methods, Broca proved that the aboriginal Basque population, which had been assumed to have short skulls, was in fact overwhelmingly long-skulled, whilst the Celts were in fact short-skulled, not long-skulled as had been previously assumed.65

With the advent of anthropology, racial science became a better organised, comprehensive and institutionalised activity. Given that anthropology’s principal aim was to explore the evolutionary history of humankind and to establish a natural system of classification of human races, it was by its very nature a transnational discipline, aimed at the worldwide mapping and numerical description of human anatomical variation. However, anthropology was also strongly linked to the nation-state: it was usually financed and organised on a national level, with national or colonial populations as its preferred research subjects, and various nations fostered different and often competing schools of research.66

Norway was a latecomer. It was only in the 1880s, and particularly in the 1890s, that anthropology became established as a field of research in Norway. From the beginning, Norwegian anthropology was inspired by foreign models, but its rise was also entwined with domestic cultural, social and political processes. Anthropological research was mainly funded by the Norwegian government and organised by national institutions. The primary aim of Norwegian anthropology was to study the racial composition and biological history of the Norwegian people, and the discipline arose within the confines of two national institutions that were particularly well placed to facilitate this task: the Norwegian Army and the University of Kristiania. While military recruits served as research objects for studies of the racial composition of the living Norwegian population, the University’s Department of Anatomy took responsibility for anthropological research on the skeletal remains of the national past. This meant that racial theories about the Germanic origin of the nation were once again a topic for discussion among Norwegian academics.

The rise of anthropology at the Department of Anatomy

Since its establishment in 1815, the University of Kristiania’s Department of Anatomy had, first and foremost, been an educational institution giving basic preclinical instruction to medical students. But from the 1870s onwards, successive heads of department tried to expand its scope and turn it into a key site for biomedical science. These efforts had limited success, however, and it was only after a major revamping in 1915 that the department really became properly equipped for research. More than 300 square metres of the department’s premises were then earmarked for physical anthropology, which became a key field of research during the interwar period. Thus, decades of efforts aimed at turning the Department of Anatomy into a leading biomedical research institution ended in a major investment in racial anthropology.67

This turn towards anthropology was the culmination of a development that had been ongoing for a couple of decades and must be understood partly against the background of the notions of ‘anatomy’, ‘biology’ and ‘science’ that underpinned the institutional strategy of the department in the late nineteenth century. Jacob Heiberg, head of the department from 1877 to 1887, and Gustav Adolph Guldberg, his successor from 1888 to 1908, advocated a modern ‘biological’ approach to anatomy at the expense of what they both saw as outdated descriptive anatomy. In his programmatic inaugural lecture, Guldberg claimed that biology consisted of two main branches: physiology, which was an autonomous discipline, and morphology, which belonged within the confines of anatomy. Morphology aimed at detecting the natural laws that govern the life-cycles of individual organisms and the overall evolution of life-forms, and it was only by engaging in such research that an anatomy department could earn the right to be regarded as a truly scientific institution.68

Guldberg was the first Norwegian professor of anatomy with an extensive scientific education, and he was well versed in morphology. Before assuming the professorship, he had studied with anatomists and zoologists who were at the forefront of morphological research, such as Eduard Van Beneden, Oscar Hertwig, Albert von Koellicker and Ernst Haeckel.69 In his inaugural lecture, Guldberg divided morphology into two main fields: ontogeny and phylogeny. These fields were interconnected owing to the law of recapitulation, which declared that ontogeny (an organism’s life-cycle from the fertilised egg to the fully-developed individual) recapitulates phylogeny (the evolutionary history of the species to which the organism belongs). Morphological research into the life-cycles of individual organisms, as well as comparative studies of anatomical likeness and difference between animal species, could therefore give insight into the evolutionary history and basic causes of the formation of the human body. Furthermore, according to Guldberg, anthropology was, in fact, a branch of morphology as it dealt with the comparative study of ‘man’s relationship to the anthropoid apes’, ‘man under diverse conditions of life’ and mankind’s division into ‘human races’.70 This meant that anthropology naturally belonged within the working field of a modern, research-oriented anatomy department.

Morphology had become a highly important research field following the breakthrough of evolutionary biology, and, like many of his German colleagues,71 Guldberg’s predecessor Jacob Heiberg campaigned intensely to turn the University of Kristiania’s Department of Anatomy into a leading institution for morphological research. He tried to obtain public funding for the construction of a new anatomy building that could house laboratories for experimental embryology and microscopy studies of tissues and cells, and which would allow for the expansion and modernisation of the Museum of Comparative Anatomy, and its systematic collection of embryos and organs from various animal species.72 Such collections were important tools for morphological research, and it was at this museum that Gustav Guldberg began his career in the late 1870s. During his time there, Guldberg managed the collection, undertook embryological and comparative anatomical research on whales, and established a huge collection of whale skeletons.73

By the time Heiberg died in 1887, it was becoming increasingly clear that neither the Norwegian political authorities nor the national medical profession favoured the idea of a research-oriented anatomy department. Instead, they wanted the Department of Anatomy to leave morphology and comparative anatomy to the zoologists and to concentrate on practical anatomical training for medical students.74 Thus, when Guldberg took over as head of the department, it was apparent that Heiberg’s grand plan would have to be abandoned. It is probably no coincidence that the Department of Anatomy then began to pursue anthropological research systematically. This was a part of morphology that did not naturally belong within zoology, and at the same time, there was a growing demand for research on the biological history of the nation which the university’s Department of Anatomy was able to meet.

Following Heiberg’s death, Guldberg went abroad to study anthropology. Although most of the contacts in his network were part of the German-speaking world, as was the case for Norwegian medical practitioners in general, he went to Paris, where he studied anthropology under Léonce Manouvrier and Paul Topinard, the leading figures in French anthropology after the death of their tutor Paul Broca in 1880. Among the first tasks Guldberg undertook after he returned to Kristiania to resume his professorship in anatomy was to improve the department’s facilities for physical anthropological research.75 According to Guldberg, a comprehensive collection of ancient crania was a basic prerequisite for the study of a nation’s ‘anthropological physiognomy’.76

The anatomical collection and the rise of anthropology

The Department of Anatomy had maintained an anatomical collection since its establishment in 1815. This was basically meant for medical instruction, but by the 1880s it also contained objects considered to be of anthropological interest, such as Sami skulls, skulls from non-European peoples (which Guldberg referred to as racekranier) and plaster casts of racekranier that the department had received from Anders Retzius in the 1850s. However, the most important items were a growing collection of ancient skulls from southern Norway that derived from archaeological excavations.77 Thus, the growth of anthropology at the university was to some extent a side effect of the growth of archaeology from the 1860s onwards. The archaeologists were more or less exclusively interested in the history of the Norwegians, and this also became the favourite research topic of physical anthropology.

When Guldberg assumed the professorial chair, he sorted out the anthropologically interesting objects and created a separate anthropological collection. He also purchased a number of anthropological measuring instruments and began to systematically supplement the collection with anthropological specimens that he had acquired from collectors, scholars and missionaries.78 In the mid-1890s, the department even began to carry out excavations on its own in order to fill in geographical gaps in the Norwegian material that had been obtained from the archaeologists.79 Guldberg evidently saw it as his task both to build up a collection of racekranier from all over the world and, more importantly, to establish a representative collection of ancient Norwegian skulls in order to facilitate research on the racial history of the Norwegian people.

The first major anthropological work undertaken at the university was the doctoral thesis Norønnaskaller (1896), written by Justus Barth, a member of staff in the Department of Anatomy. The research for Barth’s thesis involved extensive measurements and comparisons of the ancient Norwegian skulls in the collection at that time, most of which came from medieval sites in Kristiania and its vicinity (see Fig. 3). Barth claimed to have identified three racial types among the skulls: two short-skulled types and one long-skulled type. He proposed that the latter was typical for the medieval population of southeast Norway and named it the Viking type (Vikingtypen), arguing that it resembled skulls from Viking burial mounds. He also argued that the Viking type coincided with the long-skulled race that Anders Retzius had identified in Sweden in the 1840s, as well as with the so-called Reihengräbertypus that German anthropologist Alexander Ecker had detected in South German Iron Age graves in the 1860s.80

Fig. 3 Craniometrics: a ‘diptograph’ (top) and a ‘craniophor’ (bottom) used by Justus Barth for his drawings of skulls. The diptograph is covered by a glass plate on which a diopter sight is placed and then connected in turn to a pencil.

During the years that followed, the collection at the University of Kristiania was further supplemented with a number of skulls from other parts of southern Norway, and in 1901 the army doctor Carl F. Larsen published a new study based on this expanded collection entitled Norwegian Cranial Types. In contrast to Barth, Larsen argued in favour of no fewer than seven different skull types. However, he did agree with Barth on the existence of a blond, long-skulled type that he labelled the ‘Norse-Germanic dolichocephalic type’, identical to Barth’s Viking type.81

Army anthropology

In parallel with the growth of skeletal anthropology at the Department of Anatomy, army doctors began to study the racial composition of contemporary Norwegians. As a result of the military conscription system, they had easy access to a presumably representative sample of the population and could draw inspiration from countries like France, Germany and Italy, where large-scale racial surveys of conscripts had been undertaken since the 1860s.82 Racial anthropology was even considered relevant to the medical assessment of conscripts. In the Norwegian Journal of Military Medicine, army doctors discussed whether geographical variations in the supply of serviceable recruits were caused by differences in racial quality or by the impact of varying local environments.83

In a thesis published in 1875, the army doctor Carl Oscar Eugen Arbo proposed that the scope of the routine medical examinations of new conscripts should be expanded so that they might not only fulfil narrow military aims but also serve broader state interests by functioning as instruments for the collection of medical, statistical, ethnological and anthropological research data. The aim was to assess and explain variations in bodily quality within the national population and between nations, and thus to measure the physical well-being of the people and the strength of the nation.84 Arbo’s enterprise was partly inspired by the work of the leading German medical professor and anthropologist Rudolf Virchow, who, in 1863, had argued in favour of turning the assessments of conscripts into an internationally coordinated system for medical surveys of national populations. Arbo was also influenced by the French state and French military doctors, who since the end of the Napoleonic Wars had been producing national health statistics based on conscript examinations. And last but not least, he took inspiration from French anthropologists, who, under the leadership of Paul Broca, tried to explain regional variations in health and physical strength with the help of anthropological theories. Arbo analysed data from Sweden, Denmark and Norway and found that they concurred with Broca’s findings in France: inborn racial differences were more important explanatory factors for regional variations in physical health and bodily strength than differences in natural environment, climate, economic prosperity or livelihood.85

Four years after the publication of his thesis, Arbo received an overseas scholarship from the Norwegian government and went to Berlin and Paris to study anthropology. He visited, among others, Broca at the Ecole d’Anthropologie,86 where it is likely that he was confirmed in his deterministic notions of race. Broca was a neo-Lamarckian who believed that the evolution of species was driven by the inheritance of acquired characteristics. He claimed, for instance, to have proved that the average brain size of Parisians (and thus their average mental capacity) had increased since the Middle Ages because of cultural and social improvement. However, the improvement of the human brain was a slow process that spanned many generations, and Broca held that the mental abilities of individual human beings were strongly determined by their class, gender and race. All these differences could be assessed with the help of anthropometrical investigations.87

During the two decades that followed his visits to Berlin and Paris, Arbo travelled to various military camps in southern Norway, gathering data on the distribution of bodily traits such as facial length, jaw angle, body height, eye colour, hair colour and, most importantly, the breadth and length of the head. His results were published in a series of Contributions to the Physical Anthropology of the Norwegians in the 1880s and 1890s, earning him membership of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters, winning him international acclaim and turning him into the foremost Norwegian pioneer of anthropological research.88

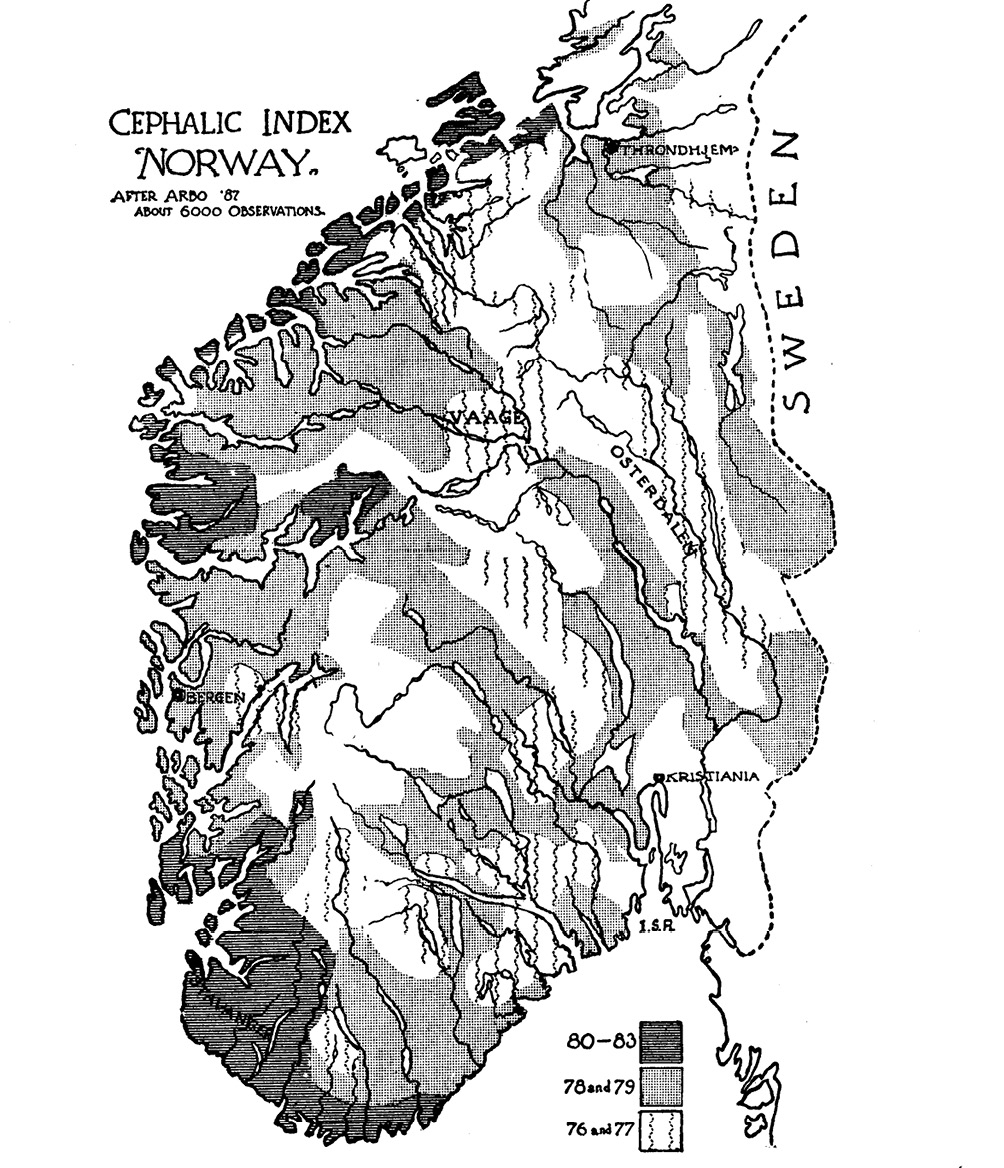

According to Arbo, the geographical distribution of short skulls and long skulls coincided with variations in dialects and with the ancient political division of Norway into counties (see Fig. 4). Arbo’s main explanation for the uneven distribution of skull shapes was that the counties had originally been settled by different peoples with diverse racial origins. A predominantly dark-haired and brown-eyed short-skulled type had a radiation centre in southwest Norway and was strongly represented in the western coastal regions. Blond and blue-eyed long skulls had their radiation centre in eastern Norway, out of which they had pushed westward to settle the inner fjord and mountain areas.89

Fig. 4 Map showing the distribution of skull types in Norway based on Arbo’s research, as presented in Ripley’s The Races of Europe (1899).

Arbo supplemented this claim with references to mechanisms of natural and social selection that had taken place after the original settlement of the territory. In a monograph from 1897, he argued that the predominantly dark, short-skulled population along the southern coast of Norway was ‘psychologically crippled’ and weak. However, the short-skulled majority was intermixed with some long-skulled individuals distinguished by their courage. Arbo suggested that the population of the coastal districts had originally included a larger proportion of long-skulled inhabitants, but that most of them had left or died since the area’s harsh living conditions did not suit their restless, adventurous and warrior-like nature. Only the calmer, more peaceful and rooted inhabitants—the short skulls—had remained.90

Arbo’s psychological assessment of local populations was based on other authors’ descriptions, on hearsay and commonly-held views, and on his own observations. Referring to the works of historians like Munch and Sars, he put forward detailed accounts of the historical events that had led the adventurous dolichocephalics to leave the coastal districts. He also compared the Norwegian case with examples from abroad. German anthropologists agreed that the average cephalic index of southern Germany had changed from dolichocephalic to brachycephalic since the Iron Age. Some anthropologists saw this as a result of superior Germanics being increasingly intermixed with inferior Slavic elements, whilst others proposed that cultural growth had produced larger brains and that over the centuries this had led to the development of a more spherical skull. Thus, what some saw as the progress of civilisation was considered by others to be a troubling example of racial degeneration. Arbo sided with the theory of detrimental racial mixing.91

Arbo compared the distribution of short skulls and long skulls with the relative number of serviceable recruits and with assumed local differences in behaviour and lifestyle. On the basis of this comparison, he argued that racial difference in the Norwegian population could explain regional variations in health, military capability, personality/character, intelligence and behaviour. Whereas people from the typically brachycephalic populations along the coast stood out as weak, nervous, worried, petty and narrow-minded, he argued the overwhelmingly dolichocephalic rural inhabitants of the inland were brave, handsome, resilient, bold and open-minded.92

Arbo obviously saw the blond long-skulled race as constituting the core of the Norwegian nation. These people were the present-day equivalent of Barth’s Viking type and embodied the nation’s most superior mental and physical abilities. Thus, Arbo’s work can be seen as a revival of the basic ideas of Munch and Keyser’s national narrative, but with one crucial difference: according to Arbo, the Norwegian people were not exclusively drawn from the Germanic race, since the superior long-skulled type was intermixed with an inferior, short-skulled kind. This idea would become a major topic in Norwegian debates on race and nationhood around the turn of the century.

The rise of anthroposociology

Arbo’s portrayal of the Norwegian population as made up of a mix of dark short skulls and blond long skulls echoed ideas that had been commonly held by European anthropologists since the heyday of Anders Retzius. Broca, for instance, believed that the French population was a racial mixture dominated by tall, fair and long-headed Kymrics and short, dark and broad-headed Gauls (the true Celtic race), and he claimed that this could explain French regional variations in military ability. Since the Gauls were smaller and weaker, they were more frequently rejected from military service than were the Kymrics. When Arbo discussed the usefulness of military medicine in his 1875 thesis, he referred extensively to this theory, and it is most likely that it was an important source of inspiration for his approach to the study of Norwegian recruits.93

There was another author, however, to whom Arbo referred more frequently in his anthropological works in the 1890s, namely Otto Ammon.94 Ammon was a leading figure in anthroposociology, a school of research within which the dichotomy between inferior short skulls and superior long skulls was a key element. Ammon seems to have been an important source of inspiration for Arbo. In order to understand the societal context and ideological implications of Arbo’s research, therefore, we need to know more about anthroposociology, its relationship to mainstream anthropology and its impact on Norwegian debates concerning racial identity and origin.

The anthroposociologists were strongly inspired by the French writer Joseph Arthur de Gobineau and his infamous Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races (1853-1855). Gobineau was a conservative who lamented the French Revolution and the fall of the ancien régime. He saw the aristocracy as the descendants of a warrior caste that had once been the bearers of European high culture, and held that the Revolution had ushered in an epoch of social and geographic mobility that led to racial mixing, threatened the racial purity of the upper class and would ultimately lead to the downfall of Europe.

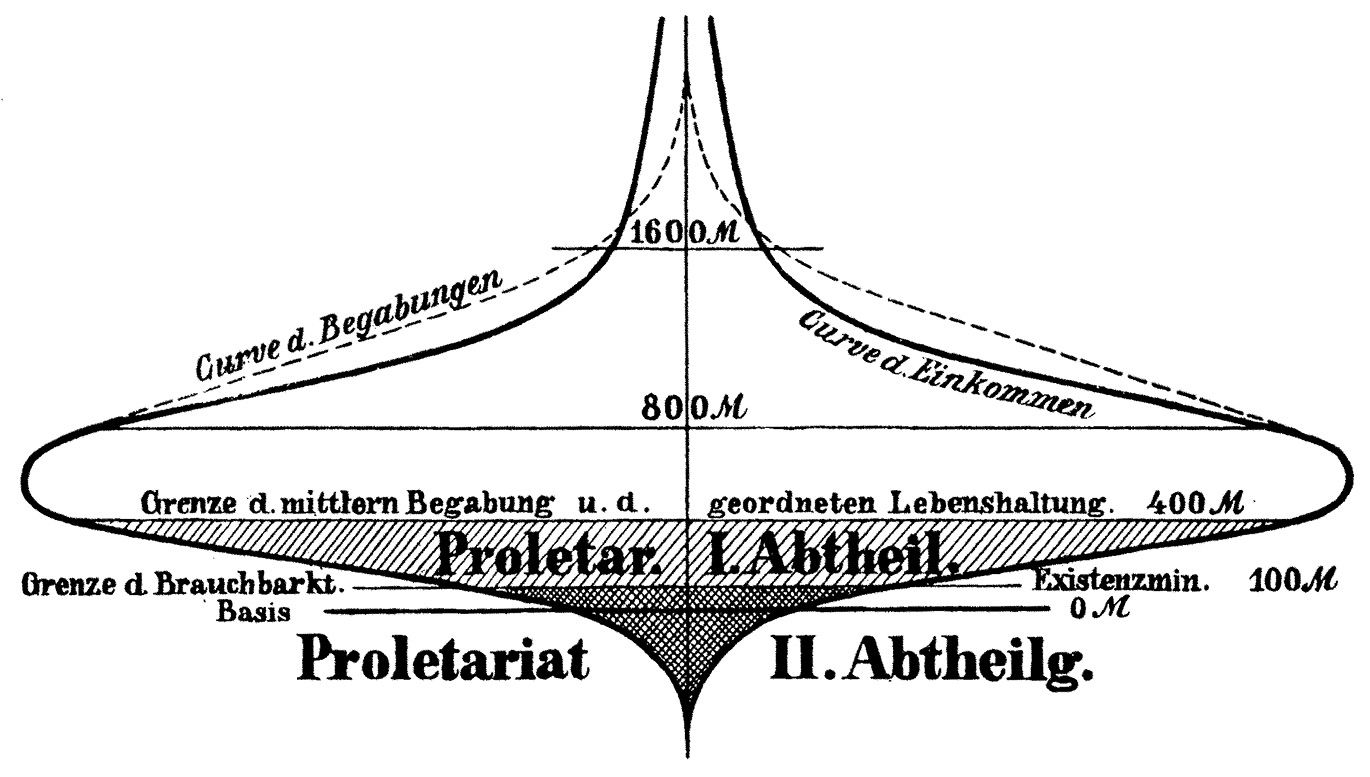

Gobineau’s ideas did not win much acclaim initially, but towards the end of the century, his Essay became a rallying point for racial ideologues, and anthroposociology arose as an attempt to establish a quantitative science based on his ideas. The anthroposociologists held that the blond, blue-eyed and long-skulled northern Europeans were descendants of a warrior race that had founded European civilisation and had been the aristocratic rulers over the inferior short-skulled races. They studied the geographical and social distribution of bodily traits such as skull shape and hair colour, and claimed to have quantitative evidence that proved that the stratification of European society mirrored the distribution of racial qualities (see Fig. 5). The anthroposociologists believed that industrialisation and urbanisation stimulated geographical and social mobility, which were over time erasing the natural distinction between classes, leading to racial mixing and biological degeneration. This was a threat to the future of Western civilisation, they argued, and should be counteracted by state intervention in the biological reproduction of citizens.95

Fig. 5 Ammon’s outlook on society: the curve on the right shows the population distributed by income; the curve on the left shows the population distributed according to intellectual endowment. The lower horizontal line indicates the threshold for ‘useable’ endowment, and this coincides with the line showing the minimum income needed for subsistence.

Anthroposociology represented an attempt to establish a new scientific discipline on the boundary between physical anthropology and the social sciences. This enterprise won different degrees of academic acclaim in France and Germany. In France, Georges Vacher de Lapouge, the chief figure of French anthroposociology, led a comprehensive research programme in the 1890s, gaining sympathisers all over the Western world and some degree of academic legitimacy in his home country.96 His German colleague Otto Ammon, in contrast, met with strong opposition from the German anthropological establishment when he began putting forward his ideas in the late 1880s and 1890s. After the turn of the century, however, the roles were reversed, with Ammon winning increasing scientific acclaim in Germany and Lapouge being ostracised from the French scientific community.

The different destinies of anthroposociology in France and Germany were symptomatic of the general development of anthropology and racial science in the two countries. Even though Paul Broca had been strongly opposed to Gobineau’s theories, anthroposociology had some important characteristics in common with Broca’s school of anthropology: a strong belief in biological determinism and in the use of anthropometry to order human beings into a hierarchy of inferior and superior biological groups. After Broca’s death, French anthropology split into competing schools, some of which began to distance themselves from Broca’s approach. This is particularly true in the case of Léonce Manouvrier, Lapouge’s most outspoken and powerful enemy within the French anthropological community. Manouvrier’s attack on Lapouge was coupled with a general criticism of racial determinism and hierarchical thinking. This criticism had a significant impact and helped to marginalise French physical anthropology around the turn of the century.97

German anthropology, in contrast, had from the beginning been characterised by a much more liberal attitude to race. The principal figure was the famous anatomist Rudolf Virchow, who, besides having a key position within German science, was a leading liberal-democratic politician. Virchow opposed militaristic nationalism, imperialism and anti-semitism, and he used his scientific knowledge and prestige to criticise the idea of pure, static and ancient races, to argue against racial superiority and to counteract the adulation of the Germanic race.98

From the 1890s, however, racial thought gained an increasingly strong foothold in German culture and public discourse, and, among radical nationalists, the nation became increasingly associated with the idea of a Germanic master race. The national-conservative völkisch movement, which advocated a romantic and racialised style of nationalism, achieved increasing popular support. While Virchow and other leading anthropologists tried to counter this wave of racial romanticism by the use of arguments from their strongly quantitative and positivist science, Otto Ammon and the anthroposociologists tried to bridge the gap between völkisch racial philosophy and scientific anthropology.99

In the 1880s, Ammon was funded by the German Anthropological Society to carry out a conscript survey in Baden. He found a high frequency of dolichocephalics in the cities, which he explained as the product of social selection: the dynamic and adventurous dolichocephalics were drawn to the city, while the more down-to-earth brachycephalics stayed in rural areas. This theory, which was later termed ‘Ammon’s Law’, met with strong opposition in the German Anthropological Society. In 1889, Ammon was refused additional funding for his project, and during the 1890s his work was rejected by the leading anthropological journals. After the turn of the century, however, his ideas began to win growing support, reflecting a more general shift in German anthropology from ‘racial liberalism’ in the nineteenth century to racial determinism after the turn of the century.100

Anthroposociology and Scandinavia

A key building block in the theoretical edifice constructed by the anthroposociologists was the notion of a convergence between the Aryan and the Germanic races. In contrast to Anders Retzius and his generation, the anthroposociologists did not believe that the original speakers of the Aryan or Indo-European language had wandered into Europe from somewhere in Central Asia. Instead, they held that the original Indo-Europeans were an indigenous European race that had arisen in northern Germany and southern Scandinavia during the Stone Age, and that the Germanic peoples were their true descendants. Thus, the Aryans were identical to the Germanics, and it was this Aryan-Germanic race that was responsible for European civilisation.

This theory was launched in the 1880s by freelance writers who stood outside or on the margins of the academic world, but who based their views upon selective reading of mainstream archaeological, linguistic and anthropological research. Since this group of writers saw Scandinavia as the cradle of the master race and the home of a particularly pure Aryan-Germanic population, they were greatly interested in research on the prehistory and racial composition of the Scandinavian populations. An important prerequisite for the rise of the Aryan-Germanic theory was the rejection of Retzius and Nilsson’s racial succession scheme in the 1860s, and the establishment of scientific consensus regarding Germanic presence in Scandinavia during the Stone Age.101

Although the Aryan-Germanic theory was at odds with Retzius and Nilsson’s account of European prehistory, these theories had some important ideological implications in common: southern Scandinavia was designated as a centre of gravity for the Germanic race, which stood at the peak of the racial hierarchy and whose members were the true bearers of European civilisation. Thus, anthroposociology seems to have provided a good starting point for the revival of glorified and racialised national narratives in Scandinavia. How, then, did Scandinavian scholars respond to these ideas? Let us take a brief look at Swedish anthropology before returning to Norway.

The leading figure in Swedish anthropology around the turn of the century was Gustav Retzius, the son of Anders Retzius. His most influential anthropological works were ‘Crania Suecica Antigua’ (1900),102 which was based on practically all existing prehistoric skulls from Sweden, and Anthropologia suecica (1902),103 which was based on a major survey of Swedish conscripts and co-written with his younger colleague Carl Magnus Fürst.

In parallel to Arbo’s findings in Norway, Retzius and Fürst found a slightly higher frequency of short skulls along the coasts and in northern Sweden. They explained this as being the result of an ‘attack’ on the pure Swedish type from alien racial elements. However, the main conclusion of Gustav Retzius’ studies was that Sweden, from the Stone Age until the present time, had been inhabited by a relatively racially-pure Germanic population.

These conclusions seemed to fit well with the Aryan-Germanic theory and attracted considerable interest among German nationalists and anthroposociologists. Gustav Retzius himself, however, was initially opposed to such an interpretation of his findings. Indeed, in concurrence with the views of leading Swedish archaeologist Oscar Montelius, he considered Scandinavia and northern Germany to be the ancestral home of the Germanics, but denied that the Germanics were identical to an ancient Aryan or Indo-European race. Retzius held that the Germanics were only one of a number of Indo-European peoples, and he was sceptical about the anthroposociologists’ dogmas.104

However, less than seven years after the publication of Anthropologia suecica, Retzius changed his mind and lent his strong, public support to the anthroposociological research programme. In a so-called Huxley Lecture in London in 1909, he hailed Lapouge and Ammon as pioneers of a ‘modern’ race typology according to which there were three European races: the Mediterraneans, the Alpines and the Nordics. Retzius even went so far as to portray the conflict between the dark, short-skulled Alpines and the blond long-skulled Nordics as a main driving force in North European prehistory. After the lecture, Retzius received a letter from Ammon, welcoming him into the ‘circle’.105

Historian Olof Ljungström has explained the shift in Retzius’ opinion by pointing to his close ties with German science and by arguing that he was a typically mainstream scientist who became strongly influenced by the rise of anthroposociology within German anthropology. Retzius was a close friend of the famous German paleoanthropologist Gustav Schwalbe, who advocated similar ideas to Otto Ammon, but who possessed far greater scientific credibility and was instrumental in winning academic acceptance for anthroposociology in Germany. In 1903, the year after Rudolf Virchow’s death, Schwalbe was the first influential anthropologist to speak in favour of Ammon and Lapouge’s theories at a meeting of the German Anthropological Society. At a national anthropology conference four years later, he even embraced Gobineau’s writings, and, according to Ljungström, it was Schwalbe who finally managed to convince Retzius that Ammon and Lapouge’s ideas were sound.106

The Aryan roots of the Norwegian nation

In contrast to Gustav Retzius’ initial dismissal of anthroposociology, we have seen that Arbo, his foremost Norwegian colleague, was already referring extensively to Ammon’s work in the 1890s. However, the most ardent, outspoken and well-known Norwegian spokesman of anthroposociology was not Arbo but rather the scientific freelancer Andreas M. Hansen, a scientific freelancer who, in the latter half of the 1890s, developed a grandiose national narrative based on the Aryan-Germanic theory. If we wish to assess the degree of academic success enjoyed by these ideas in Norway, as well as the impact they had on dominant national narratives, we need to consider the reception of Hansen’s ideas.

Hansen held a teacher’s degree in science from the University, which at the time was the highest level of natural-scientific education that could be achieved in Norway. For most of his life, he worked as a freelance researcher and author in disciplines such as geography, geology, anthropology and archaeology. He was the first person in Norway to demonstrate the existence of inland shorelines—traces of the post-glacial land rise—and developed a method for using these shorelines to date Stone Age settlements. This aspect of his work was pioneering, won academic acclaim and is still recognised as scientifically valid. However, these studies also provided a starting point for Hansen’s racial account of the history of the Norwegians, which he launched in the latter half of the 1890s and which became both widely known and hotly disputed.107

Hansen’s account was underpinned by an impressive array of arguments from plant geography, geology, archaeology and linguistics, as well as racial anthropology. The core idea was that the regional boundaries discovered by Arbo between short-skulled and long-skulled populations coincided with the boundaries of the glaciers during the last Ice Age. This, according to Hansen, proved that a short-skulled aboriginal population had survived along the ice-free Norwegian coast during the Ice Age. Long-skulled people had later wandered in and established themselves north and east of the glacier, and then followed the frontier of the melting ice south and westward.

Hansen proposed that the ancient Aryans had their roots in Europe. They had been the first speakers of the original Aryan/Indo-European language and were the forefathers of the long-skulled Germanic peoples. After the Ice Age, they had established themselves as a ruling caste in Europe and had imposed their Aryan language and superior culture upon the inferior and short-skulled Anaryan peoples. In line with this, the short skulls along the west coast of Norway were descendants of an Anaryan race of slaves, while the long-skulled population in eastern Norway and in the interior valleys and mountains belonged to the Aryan master race; they were the ones who had created the Old Norse culture.108

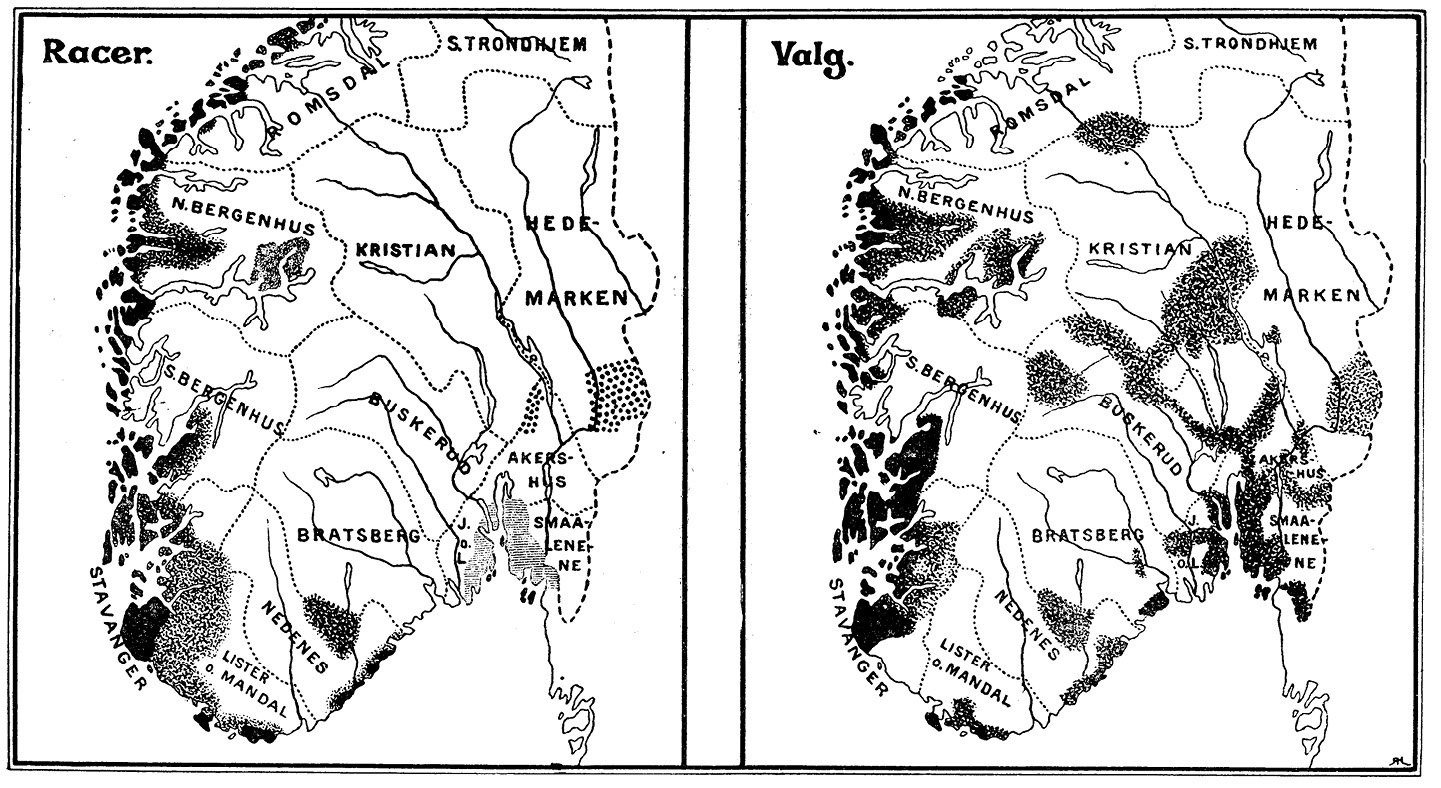

Hansen believed his theory could shed light on a number of cultural, social and political features of contemporary Norway. In his 1899 book Norwegian National Psychology, he demonstrated that the geographical distribution of short and long skulls coincided with the distribution of votes in the parliamentary elections, and claimed that this could be explained by the double racial origin of the nation (see. Fig. 6). Individuals from the predominantly Anaryan rural population on the west coast were distrustful, bigoted, backward-looking and politically conservative, and were therefore inclined to vote for the Høyre Party, while the predominantly Aryan population in the south eastern inland were more open-minded, courageous and intelligent, and thus they represented the progressive forces of society and would most likely vote for the Venstre Party.109

Fig. 6 The map to the right shows the distribution of conservative votes in the Parliamentary election of 1897. The map to the left highlights the areas with a majority short-skulled population.

Hansen’s account of the origin of the Aryans and Anaryans was partly based on theories developed by German philologist Karl Penka in the 1880s. Penka was a pioneer of the Aryan-Germanic hypothesis and an important source of inspiration for Otto Ammon.110 In his work Hansen also referred frequently to Otto Ammon and Vacher de Lapouge, and his racial analysis of the political and social landscape in Norway was typical of the anthroposociological school of research. According to Carlos Closson, an American advocate of anthroposociology, the findings presented in Norwegian National Psychology confirmed the basic anthroposociological idea of a correlation between bodily and psychological racial traits.111

Otto Ammon himself acknowledged Hansen’s book and discussed it in the German journal Centralblatt für Anthrophologie. Ammon was well informed about Scandinavian anthropological research, but argued that it was Hansen who had come up with the true explanation for the geographical distribution of long skulls and short skulls, and that this explanation was also relevant for attempts to understand the racial composition of Germany. Ammon was particularly thrilled by Hansen’s analysis of the psychological differences between the two races, contrasting the aristocratic, freedom-loving attitude of the long skulls with the excessive ideas of equality held by the short skulls, who lacked any sense of freedom. Hansen’s work demonstrated, according to Ammon, that the slave-like mentality of the short skulls and the aristocratic mentality of the long skulls were not the result of the centuries in which the Anaryans had been slaves to the Aryans; instead, the master/slave relationship had emerged naturally from the ancient inborn psychological differences between the two races.112

Ammon even discussed the objections that had been raised against Hansen’s theories, such as the claim that there was no proof of any relationship between skull shape and intelligence. According to Ammon and Hansen, this critique was beside the point, and neither man believed in a direct relationship between skull shape and mental faculties. They rejected, implicitly, the theories on brain anatomy that had been the rationale behind Anders Retzius’ invention of the cephalic index sixty years earlier, though this index was still a key concept in their research. They declared that the cephalic index was nothing more than a method for identifying racial difference; however, since the races were equipped with different mental abilities, there was an indirect relationship between the geographical distribution of short skulls and long skulls and psychological characteristics.113

This idea of an indirect relationship between skull shape and mental faculties meant that Ammon and Hansen were able to dismiss critics who took the existence of brave and highly intelligent short-skulled individuals as evidence against the anthroposociological dogmas. They claimed that even if the races were mentally different on average, there could still be great variation within each race. Thus, the existence of some superior non-Aryan individuals did not disprove claims that the non-Aryans were, on average, inferior to the Aryans.

The controversy over the blond short skull

A linchpin of Hansen’s account was the notion of the two races within the Norwegian people.114 However, Hansen did not base this view upon his own empirical research; instead, he leaned strongly on the work of Arbo and others. This meant that Hansen ran into trouble when Arbo discovered that blondness tended to coincide with brachycephaly in southeast Norway and began arguing for the existence of a third race, one that was blond and short-skulled. Arbo termed this the ‘North Sea race’ (Nordsjørasen) on account of its similarity to racial elements found on the European North Sea coast.115

In his book Norrønnaskaller, Justus Barth also proposed the existence of two different short-skulled types, and in 1901 Carl F. Larsen claimed to have identified no fewer than seven different racial types in the University’s skull collection.116 Over the following years, Larsen undertook a series of surveys of conscripts from the central Norwegian counties of Trøndelag and Nordland, and claimed to have identified a certain long-skulled Trønder type that differed from the eastern Norwegian long skulls. He even suggested that the existing Norwegian population contained a number of different short-skulled types, arguing that the most common of these were not the dark, Alpine race, but rather a blond type.117

These views, and in particular the idea of a blond short-skulled race, ran counter to the simple racial dichotomy upon which Hansen’s grand theory was based. Hansen therefore set out to prove that the blond brachycephal was not a true race but the product of racial mixing between a dark bracycephalic and a blond dolichocephalic race. He tried to prove his point with the help of arguments drawn from a number of disciplines, such as philology, archaeology and history, as well as anthropology. Larsen responded by accusing Hansen of interpreting any empirical evidence in ways that would fit his overarching theory, and he countered Hansen’s grandiose theorising with quantified data on anatomical variations within past and present Norwegian populations.118 Hansen, in turn, claimed that Larsen’s empiricist, inductive and descriptive approach would only lead to the splitting up of any population into an increasingly fine-graded, descriptive and meaningless typology of races.119

The strong disagreement over the number of Norwegian races and the controversy between Hansen and Larsen must be understood against the background of ongoing international debates over the meaning of the anthropological concept of race. Around the turn of the century, American sociologist William Z. Ripley published The Races of Europe,120 while the French anthropologist Joseph Deniker issued The Races and the Peoples of the Earth.121 Both men studied the geographical distribution of traits such as skull shape, body length, hair and eye colour, but while Deniker split the Europeans into six main races and four secondary races, Ripley, in line with the anthroposociologists, argued for three: the dark, long-skulled Mediterranean race in the south, the blond, long-skulled Nordic race in the north, and the dark, short-skulled Alpine race in the middle.122 According to Ripley, their conflicting results were caused by different understandings of the concept of race: Deniker’s typology was purely descriptive and did not identify the underlying original races. When Deniker detected a frequently-appearing combination of traits, he characterised them as a race and gave them a name, and this meant that Deniker did not address what Ripley considered the real task of anthropology—that of identifying the inheritable, ideal ‘types’ within the population.123

The controversies between Deniker and Ripley and between Larsen and Hansen had to do with a built-in ambiguity in the anthropological idea of racial types. When anthropologists talked about ‘types’, this could mean an average bodily type that was assumed to be typical of a certain race. However, it could also mean an anatomical ‘building plan’ inherited by members of a race. This double meaning led to problems for the anthropologists. The theories of Anders Retzius, Sven Nilsson and Rudolf Keyser had been based on the assumption of a concurrence between skull shape, ethnic identity and racial type. Since their time, however, it had become increasingly clear that there was a complicated relationship between ‘people’ and ‘race’: it was commonly accepted that all observed populations were racially mixed. There was no easy way to detect the basic racial types within racially-mixed populations.124

Perhaps the turn-of-the-century debates over racial types can be best understood against the background of the approach to heritability put forward by the anthropologist, statistician, biologist and eugenicist Francis Galton in the 1880s. Galton studied the frequency of various quantifiable traits in a population and showed that they tended to vary around an average value. He also showed that deviations from the average were distributed according to a normal distribution curve, meaning that when biological traits were inherited over generations, it was this tendency to vary around a norm that was passed down. Singular individuals who deviated from the average norm would therefore produce offspring who, on average, were closer to the norm than their parents. Accordingly, a reversion to the average type took place.125

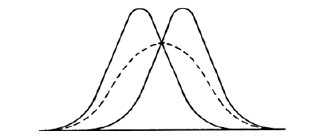

For racial anthropology, this meant that any human race had a series of racially-specific features that could be described with the help of figures, such as body length, facial length, arm span and cephalic index. If one examined these figures in a purebred population, one would find that the values that deviated from the race-specific figure occurred with a frequency that was normally distributed around this average figure. The question was how to detect the true racial types within a racially-mixed population.126 Hansen believed that he had found an answer to this question. With the help of his own statistical invention—the so-called affinitetstallet (affinity figure)—he claimed that he could demonstrate that blondness was statistically correlated with dolichocephaly, and darkness with brachycephaly. This would indicate that the ‘blond brachycephal’ represented a mixture of blond dolichocephalics and dark brachycephalics. Hansen also produced graphs showing the frequency of various cephalic indices in the population. These graphs proved to have three peaks, and the highest peak was located between the two others, indicating that the most frequent cephalic index was neither the assumed typical index of the short-skulled Alpine race, nor the assumed typical index of the Nordic race, but something in between. Somewhat counter-intuitively, Hansen took this as evidence of racial mixing. He explained the curve as the sum of two overlapping standard distribution curves, which peaked around the average cephalic index of the Alpine (non-Aryan) and the Nordic (Aryan) race (see Fig. 7). The highest peak occurred in the middle because negative deviation in one racial group and positive deviation in the other overlapped, so that individuals could have the same cephalic index and still belong to different races.127

Fig. 7 Illustration of the issue of racially-mixed populations from Rudolf Martin’s Lehrbuch der Anthropologie. The dotted line shows the relative distribution of cephalic indices in the overall population. The two overlapping curves show the relative distribution of cephalic indices among the two races assumed to comprise the whole population.

In order to prove that brachycephaly and dolicocephaly were deeply-rooted, inheritable racial traits, Hansen also referred to research that indicated that individuals could be identified as dolichocephalics or brachycephalics at an early stage of embryological development, and that these traits were not blurred in mixed offspring. Children with a brachycephalic father and a dolichocephalic mother would either be dolichocephalic or brachycephalic, not something in between. He claimed that the task of anthropology was to identify such inborn racial traits in the population, and that Larsen’s purely descriptive typology was irrelevant to this task.128

Hansen’s racial theories turned him into a well-known public figure in Norway, and his theories were taken seriously both by the academic community and by the general public. Hansen never held a regular academic position, but in 1908, at the age of 51, he was awarded a lifelong state scholarship by the Norwegian Parliament to enable him to continue his studies of the history and anthropology of Norwegians.129 Such state scholarships were usually given to individual scholars whose work did not fit within the scope of established institutions, particularly scholars doing research in the humanities that was considered to be of national importance. In 1910, Hansen even attained membership of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters, meaning that in spite of his fanciful racial theories, he was clearly acknowledged as a legitimate member of the Norwegian academic community.

However, while he may not have been regarded as a pseudo-scientist, Hansen was clearly a controversial one. He was a stubborn and opinionated man who moved freely and without humility between disciplines, often quarreling with respected experts in various fields of knowledge. We have already seen that his physical anthropological views were strongly disputed by Larsen, and in the next chapter we will see that experts were also critical of many of his historical, linguistic and archaeological arguments.

Professor Guldberg and anthroposociology

If Hansen was an enfant terrible who thrived on the outskirts of the academic establishment, Gustav Adolf Guldberg was his antithesis. As head of the Department of Anatomy, Professor Guldberg held one of the most influential and prestigious positions within the national system of medical research and education. In 1903, he was even elected president of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters, consolidating his position as a key figure in the Norwegian academic world. At the same time, he was also a driving force behind the anthropological research at the Department of Anatomy. How, then, did Guldberg respond to anthroposociology?130

Despite taking the lead in establishing anthropological research at the university, Guldberg produced relatively few anthropological works himself. The most important of these were an investigation of two female skeletons from the Oseberg Viking ship and a study of Norwegian medieval and prehistoric bones that sought to determine body length through a comparison of shin bones.131 These studies reveal little about his attitude towards race, but they do show that Guldberg was an empirically accurate and thorough scientist who—in contrast to Hansen, Lapouge and Ammon—was reluctant to draw bold conclusions.

Guldberg’s attitude can also be discerned in a popular-science book from 1890 in which he argued that Darwinism should be confined to natural science and not turned into a social philosophy. Guldberg strongly opposed the idea of an evolution driven solely by random variation and natural selection, and he characterised Ernst Haeckel, the famous zoologist who is often referred to as the main German advocate of Social Darwinism,132 as ‘a literary gifted fanatic’ surrounded by ‘blind’, arrogant and narrow-minded supporters.133 In sum, Guldberg’s book espoused a type of evolutionism and a view on the social (ir)relevance of evolutionary theory that were strongly at odds with the anthroposociological research programme. Fourteen years later, however, Guldberg appears to have changed his thinking. In 1904, he launched a plan for a racial survey of Norway that was explicitly inspired by Ammon and Lapouge. In a speech to the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters, he proposed a nationwide investigation of regional variations in bodily characteristics such as head shape, body length and eye colour, and even suggested gathering data on regional variations in mentality and behaviour. He argued that the national population was composed of different races that were not only physically but also psychologically unique, and that this, more than anything else, could explain certain social phenomena and shed light on historical and political issues.134

Guldberg seems to have moved a long way from his dismissal of the Social Darwinian faith a decade earlier. This may in part have been due to the fact that, like his Swedish colleague Gustav Retzius, most of Guldberg's international professional network was located in Germany. He was thus influenced by the growing acceptance of anthroposociology within German anthropology after the turn of the century. Guldberg’s proposal for a national survey was put forward at the request of Gustav Schwalbe, who headed an initiative by the German Anthropological Society for a ‘Statistical-Anthropological’ survey of Germany. Schwalbe suggested similar surveys in Scandinavia, and Guldberg’s speech to the Academy of Science was in part a word-for-word translation of Schwalbe’s original proposal, which was strongly inspired by the anthroposociological research programme.135 Given that the request came from a respected scientist like Schwalbe, acting on behalf of the German Anthropological Society, the project may have appeared to Guldberg to be an uncontroversial, mainstream scientific undertaking. In addition, it can be argued that anthroposociology offered a convenient set of arguments for the social utility of anthropological research. But the important fact is that these arguments actually won support from the scientists assembled at the Academy meeting. Guldberg’s speech led to the establishment of an ‘Anthropological Central Committee’ consisting of Guldberg, Arbo, Larsen and the army doctor A. L. Faye.136 The initiative, however, proved unsuccessful; no national survey was ever undertaken by the committee, and over the next four years Guldberg, Arbo and Larsen passed away. It was not until the interwar years that the vision of a national survey would finally be realised by a new generation of anthropologists.

64 See, for instance: Elisabeth A. Williams, ‘Anthropological Institutions in Nineteenth-Century France’, Isis, Vol. 76, no. 3 (1985), pp. 331-48; Chris Manias, ‘The Race Prussienne Controversy: Scientific Internationalism and the Nation’, Isis, Vol. 100, no. 4 (2009), pp. 733-57; Stephen Jay Gould, The Mismeasure of Man (London: Penguin, 1996), pp. 105-42; Martin Staum, ‘Nature and Nurture in French Ethnography and Anthropology, 1859-1914’, Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 65, no. 3 (2004), pp. 475-95.

65 Richard McMahon, The Races of Europe: Anthropological Race Classification of Europeans 1839-1939 (Ph.D. thesis, European University Institute, 2007), p. 207.

66 The relationship between internationalism, nationalism and the development of anthropology is discussed in Chris Manias, ‘The Race Prussienne Controversy: Scientific Internationalism and the Nation’, Isis, Vol. 100, no. 4 (2009), pp. 733-57.

67 Jacob Heiberg, ‘Om et biologisk laboratorium’, Norsk Magazin for lægevidenskaben, no. 1 (1883-1884), pp. 65-70; Jon Røyne Kyllingstad and Thor Inge Rørvik, 1870-1911: Vitenskapenes universitet, Universitetet i Oslo 1811-2011, Vol. 2 (Oslo: Unipub, 2011), pp. 195-99, 438; H. Hopstock, Det anatomiske institutt 23. Januar 1815 -23. Januar 1915 (Kristiania: I kommission hos Aschehoug, 1915), pp. 155-85; Per Holck, Den fysiske antropologi i Norge. Fra anatomisk institutts historie 1815-1990 (Oslo: Anatomisk institutt, University of Oslo, 1990).

68 Gustav Guldberg, Om det anatomiske studium: Tale tale ved tiltrædelsen af professoratet i anatomi ved Christiania universitet d. 7de septbr. 1888 (Kristiania: I kommision hos Dybwad, 1888).

69 Justus Barth, ‘In Memoriam! Professor Dr. Med. G.A. Guldberg’, Internationale Monatsschrift für Anatomie und Physiologie (1908), pp. 101-04; idem, ‘Gustav A. Guldberg’, Forhandlinger i Videnskabs-selskabet i Christiania aar 1908. (Kristiania: I kommission hos Jacob Dybwad, 1909), pp. 11-24; Carl M. Fürst, ‘Gustav Adolph Guldberg’, Anatomischer Anzeiger, Vol. 32, nos. 19/20 (1908), pp. 506-12.

70 Guldberg, Om det anatomiske studium.

71 On morphology and anatomy in Germany, see Lynn K. Nyhart, Biology Takes Form: Animal Morphology and the German Universities, 1800-1900 (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1995).

72 Jacob Heiberg, ‘Om et biologisk laboratorium’, Norsk Magazin for lægevidenskaben, no. 1 (1884), pp. 65-70. The comparative anatomical collection (Det zootomiske museum) had existed in the Department of Anatomy since the 1840s, but in the 1870s it was transferred to the Zoological Museum. This was against Heiberg’s will, as he wanted to keep the collection at the Department of Anatomy and further expand it. See RA: S-2536 UiO Medfak Aa, L0002 Forhandlingsprotokoll 1870-1885: Faculty board meeting, 23 October, 13 November and 11 December 1877.

73 Kyllingstad and Rørvik, 1870-1911: Vitenskapenes universitet, pp. 295-300.

74 Ibid., pp. 195-99, 212-19, 295-300.

75 Before returning to Kristiania, Guldberg also occupied for some months the chair vacated by anatomist and anthropologist Gustaf von Düben, the successor to Anders Retzius in Stockholm, where it is likely that Guldberg familiarised himself with the Swedish tradition of racial anthropology. See Barth, ‘In Memoriam!’ and Fürst, ‘Gustav Adolph Guldberg’.

76 G. A. Guldberg, ‘Udsigt over en del fund af gammelnorske kranier’, Nordisk medicinsk arkiv, Vol. 30, no. 13 (1897), pp. 1-6.

77 Ibid.

78 See ‘Det anatomiske institut’, in Det kongelige norske Frederiks Universitets Aarsberetning for 1889-1890, 1890, 1890-1891, 1891-1892 and 1892-1893 (Kristiania: Universitetet, 1889-1894).

79 Gustav A. Guldberg, ‘Skeletfundet paa Rør i Ringsaker og Rør kirke’, Christiania videnskabs-selskabs forhandlinger, no. 9 (1895), pp. 3-14; G. A. Guldberg, ‘Fra det anatomiske institut ved det kgl. Fredriks universitet’, in Foreningen til norske fortidsmindesmærkers bevaring, Aarsberetning for 1900 (Kristiania: [n. pub.], 1901), pp. 1-3.

80 Justus Barth, Norrønaskaller: crania antiqua in parte orientali Norvegiæ meridionalis inventa: En studie fra Universitetets Anatomiske Institut (Kristiania: Aschehoug, 1896), pp. 1-3, 57ff. In 1868 the Department of Anatomy received 53 skulls from archaeological excavations in a medieval churchyard and a nearby site in Kristiania (Mariakirken and Sørenga). In 1879, fifty skulls came in from the cemetery of a medieval monastery in Kristiania. In 1890, the collection was further supplemented by 56 skulls assumed to be from a Franciscan monastery in Tønsberg, located on the Kristiania fjord (Oslofjorden) and one of Norway’s oldest towns.

81 C. F. Larsen, Norske kranietyper: efter Studier i Universitetets anatomiske Instituts Kraniesamling. Skr. Vidensk. Selsk. Christiania MN kl., 1901, no. 5 (Kristiania: Videnskabsselskabet, 1901).

82 Otto Ammon, Anthropologische Untersuchungen der Wehrpflichtigen in Baden. (Hamburg: Verlagsanstalt und Druckerei Actien-Gesellschaft, 1890); Ridolfo Livi, Antropometria Militare (Roma: Presso il Giornale medico del Regio Esercito, 1896-1905). Manias, ‘The Race Prussienne Controversy’, p. 739.

83 Norsk tidsskrift for militærmedicin. Kristiania. First issue, 1897.

84 C. O. E. Arbo, Om Sessions-Undersøgelsernes og Recruterings-Statistikens Betydning for Videnskaben og Staten med et Udkast til en derpå grundet Statistik for de tre nordiske Riger (Kristiania: Steenske bogtrykkeri, 1878), pp. 1-8.

85 Arbo, Om Sessions-Undersøgelsernes, pp. 1-8, 17-18, 154.

86 Axel Johannessen, ‘Carl Oscar Eugen Arbo’, Tidsskrift for den norske lægeforening, Vol. 26 (1906), pp. 516-19.

87 Stephen Jay Gould, The Mismeasure of Man, pp. 105-42.

88 Lars Walløe, ‘Carl Arbo’, in Norsk biografisk leksikon, https://nbl.snl.no/Carl_Arbo. Arbo was cited in detail in William Z. Ripley, The Races of Europe. A Sociological Study (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., 1899), pp. 205-11. Joseph Deniker also used data from Arbo’s works in his 1899 book Les races de l’Europe (see Hans Daae, Militærlægers bidrag til norsk anthropologi (Kristiania: Gøndahl, 1907), p. 16).

89 Retzius used Broca’s system of three categories based on the cephalic index (dolicho-, meso- and brachycephalic), but in his final analysis he merged the dolicho- and mesocephalics into one dolicho-mesocephalic category.

90 C. O. E. Arbo, Fortsatte Bidrag til Nordmændenes Anthropologi IV Lister og Mandals Amt, Skr. Vidensk. Selsk. Christiania MN kl. 1897 (Kristiania: I Kommission hos Dybwad, 1897), p. 43.

91 C. O. E. Arbo, Fortsatte Bidrag til Nordmændenes Anthropologi V. Nedenes amt. Skr. Vidensk. Selsk. Christiania MN kl. 1898 (Kristiania: I Kommission hos Dybwad, 1898), p. 53; Gustaf Retzius, ‘Blick på den fysiska antropologiens historia’, Ymer, Vol. 16, no. 4 (1896), pp. 221-45 (pp. 240-41); Gaston Backman, ‘Den Europeiska rasfrågan ur antropologisk och sociala synspunkter’, ‘Den Europeiska rasfrågen ur antropologisk och sociala synspunkter’, Ymer, Vol. 35, no. 4 (1915), pp. 330-50 (p. 345).

92 See, for instance: C. O. E. Arbo, ‘Udsigt over der sydvestlige Norges anthropologiske forhold’, Ymer, Vol. 14 (1894), pp. 165-86, (p. 173ff.); Fortsatte Bidrag til Nordmændenes Anthropologi V. Nedenes amt, p. 62; idem, Fortsatte Bidrag til Nordmændenes Anthropologi IV Lister og Mandals Amt.

93 Arbo, Om Sessions-Undersøgelsernes, pp. 17-18, 154.

94 The most cited foreign book in Arbo’s works in the 1890s was Otto Ammon, Die natürliche Auslese beim Menschen (Jena: G. Fischer, 1893).

95 Jennifer Michael Hecht, ‘The Solvency of Metaphysics: The Debate over Racial Science and Moral Philosophy in France, 1890-1919’, Isis, Vol. 90, no. 1 (1999), pp. 1-24 (pp. 3ff.); Benoit Massin, ‘From Virchow to Fischer: Physical Anthropology and “Modern Race Theories” in Wilhelmine Germany’, in George W. Stocking, Jr., ed., Volksgeist as Method and Ethic (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin, 1996), pp. 106-14.

96 Jennifer Michael Hecht, ‘A Vigilant Anthropology: Léonce Manouvrier and the Disappearing Numbers’, Journal for the History of the Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 33, no. 3 (1997), pp. 221-40.

97 Hecht, ‘A Vigilant Anthropology’, pp. 221-40.

98 Massin, ‘From Virchow to Fischer’, pp. 79-153 (pp. 86ff.).

99 Ibid., pp. 100ff., 132.

100 Massin, ‘From Virchow to Fischer’, pp. 126-43.

101 Olof Ljungström, Oscariansk antropologi. Etnografi, förhistoria och rasforskning under sent 1800-tal. (Hedemora: Gidlund, 2004), pp. 262ff.

102 Gustav Retzius, ‘Crania Suecica Antigua’, Ymer, Vol. 20, no. 76 (1900), pp. 76-87.

103 Gustav Retzius and Carl M. Fürst, Anthropologia suecica: beiträge zur Anthropologie der Schweden nach den auf Veranstaltung der schwedischen Gesellschaft für Anthropologie und Geographie in den Jahren 1897 und 1898 ausgeführten Erhebungen (Stockholm: [n. pub.], 1902).

104 Ljungström, Oscariansk antropologi, pp. 301, 303-06, 322.

105 Ibid., p. 341.

106 Ibid., p. 333ff.

107 Werner Werenskiold, ‘Andreas M. Hansen’, in Norsk biografisk leksikon, Vol. 5 (Oslo: Aschehoug, 1931) pp. 358-63.

108 Andreas M. Hansen, Menneskeslektens ælde (Kristiania: Jacob Dybwad, 1899), pp. 46, 69-75. Hansen refers to Karl Penka’s Die Herkunft der Arier. Neue Beiträge zur historischen Anthropologie der europäischen Völker (Vienna: K. Prochaska, 1886).

109 Andreas M. Hansen, Norsk folkepsykologi: med politisk kart over Skandinavien (Kristiania: Jakob Dybwad, 1899).

110 In Menneskeslektens ælde, pp. 46, 69-75. Hansen refers to K. Penka’s Origines Ariacæ (1883) and Die Herkunft der Arier (1886).

111 Carlos C. Closson, ‘A Critic of Anthropo-Sociology’, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 8, no. 3 (1900), pp. 397-410 (p. 403); Josep R. Llobera, ‘The Fate of Anthroposociology in L’année Sociologique’, Jaso, Vol. 27, no. 3 (1996), pp. 235-51 (p. 242).

112 Otto Ammon, ‘Zur Anthropologie Norwegens‘, Zentralblatt für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Uhrgeschichte, Vol. 5, no. 3 (1900), pp. 129-37.

113 Ibid.

114 Barth, Justus, Norrønaskaller: crania antiqua in parte orientali Norvegiæ meridionalis inventa: En studie fra Universitetets Anatomiske Institut (Kristiania: Aschehoug 1896).

115 C. O. E. Arbo, Den blonde Brachycephal og dens sandsynlige udbredningsfelt (Kristiania: Kristiania Videnskabs-Selskab, 1906).

116 C. F. Larsen, Norske kranietyper, pp. 1-20. Larsen used a system invented by the Italian anthropologist Guiseppe Sergi and classified the skulls according to geometrical types: ellipsoid, rhomboid, etc.

117 C. F. Larsen: Trønderkranier og trøndertyper, Skr. Viden. selsk. Christiania MN kl. 1903 (Kristiania: I kommission hos Dybwad, 1903); idem, Nordlandsbefolkningen: antropologiske Undersøgelser 1904, Skr. Viden. selsk. Christiania MN kl. 1905 (Kristiania: I kommission hos Dybwad,1905).

118 Ibid., pp. 23-26.

119 Andreas M. Hansen, Landnåm i Norge. En udsigt over bosætningens historie (Kristiania: Fabritius, 1904), pp. 219ff.

120 William Z. Ripley, The Races of Europe. A Sociological Study (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., 1899).

121 Joseph Deniker, Les races et les peuples de la terre: elements d’anthropologie et d’ethnographie (Paris: Schleicher, 1900). I refer to the English version of this work: The Races of Man (London: Walter Scott, 1900).

122 Ripley, The Races of Europe.

123 Ibid., pp. 597-608.

124 See, for instance: Massin, ‘From Virchow to Fischer’, pp. 106-14.

125 Daniel J. Kevles, In the Name of Eugenics: Genetics and the Uses of Human Heredity (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1985), pp. 13-19.

126 See, for instance, Andreas M. Hansen, ’To grundraser i det danske folk’, Nyt magasin for naturvidenskaberne, Vol. 53, no. 3 (1915), pp. 203-67; Søren Hansen, ‘Om Grundracer i Norden’. Forhandlinger ved De skandinaviske naturforskeres 16. møte i Kristiania den 10.-15. juli 1916 (Kristiania: A.W. Brøggers boktrykkeri 1918), pp. 822-38; C. O. E. Arbo, ‘Er der foregået nye invandringer i Norden? Foredrag på det skandinaviske naturforskermöde i Stockholm 1897’, Ymer, Vol. 20, no. 1 (1900), pp. 25-49.

127 Hansen, Landnåm i Norge, pp. 230-51.

128 Hansen, Landnåm i Norge, pp. 230-51.

129 Statsstipendium from 1908, cited in Per Holck, Den fysiske antropologi i Norge, p. 38.

130 Barth, ‘In Memoriam!’, pp. 101-04.

131 Gustav Guldberg, Die Menschenknochen des Osebergschiffs aus dem jüngeren Eisenalter: eine anatomisch-anthropologische Untersuchung, Skr. Vidensk. Selsk. Christiania MN kl. 1907 (Kristiania: I komission hos Dybwad, 1907); idem, Anatomisk-anthropologiske Undersøgelser af de lange Extremitetknokler fra Norges Befolkning i Oldtid og Middelalder, 1, Undersøgelsesmethoderne, Laarbenene og Legemshøiden, Skr. Vidensk. Selsk. Christiania MN kl. 1901 (Kristiania: Brøggers bogtrykkeri, 1901).

132 Richard Weikart, ‘The Origins of Social Darwinism in Germany, 1859-1895’, Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 54, no. 3 (1993), pp. 469-88.

133 Gustav A. Guldberg, Om Darwinismen og dens rækkevidde (Kristiania: Dybwad, 1895), p. 85.

134 Gustav A. Guldberg, Om en samlet anthropologisk undersøgelse af Norges befolkning, Christiania videnskabs-selskabs forhandlinger for 1904, no. 11 (Kristiania: I commission hos Dybwad, 1904), p. 6.

135 Ibid., p. 339.

136 Ibid., p. 5.