1. The “written landscape” of the central Sahara: recording and digitising the Tifinagh inscriptions in the Tadrart Acacus Mountains

© S. Biagetti, A. Ait Kaci and S. di Lernia, CC BY http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0052.01

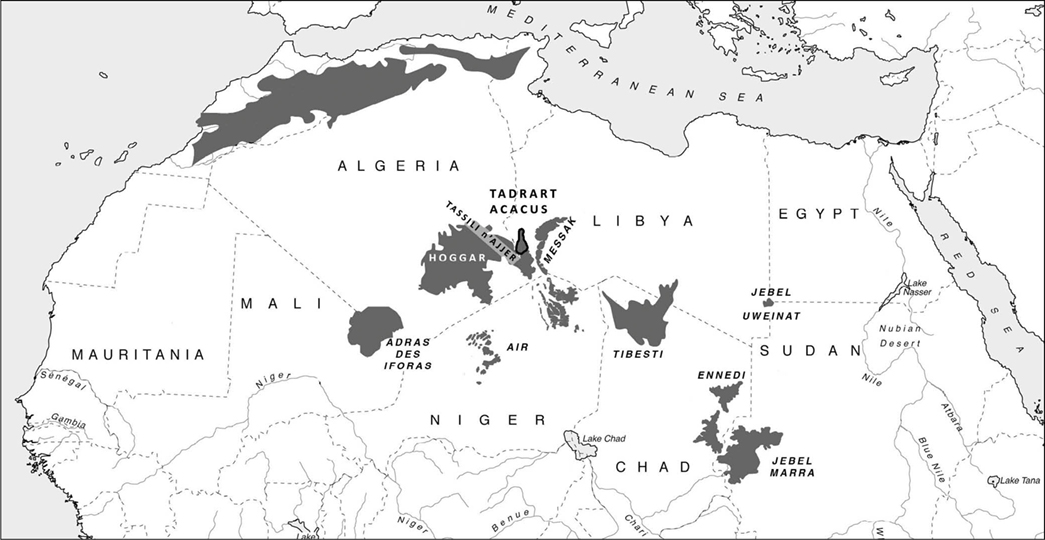

The archaeology of the Sahara in both historical and modern times remains, for the most part, inadequately investigated and poorly understood. However, the Fazzan in southwest Libya stands as a remarkable exception. In the last two decades, the University of Leicester1 and the Sapienza University of Rome2 have undertaken various research programmes that focus on the impressive evidence left by the Garamantian kingdom (c. 1000 BC-AD 700). These studies have provided groundbreaking data on the history of the Fazzan (Fig. 1.1), an area which was the centre of a veritable network of trans-Saharan connections that developed in Garamantian times and continued to modern times, later giving birth to the Tuareg societies.3

Fig. 1.1 Map of the Tadrart Acacus and the central Saharan massifs.

Farmers, caravaneers and herders in this area all participated and intercepted in a variety of socio-economical exchanges that developed from the first millennium BC to the present day. In spite of its arid climate, the central Sahara has, in the last 3,000 years, seen some extremely successful human adaptations to limited resources. An intangible heritage of indigenous knowledge allowed complex societies to flourish in the largest desert in the world. That heritage has left a legacy of tangible evidence in the form of remains, such as forts, monuments, burials, and settlements, all of which have been the focus of recent archaeological studies. This paper deals with the less investigated element of the archaeological and historical landscape of the region: the Tifinagh inscriptions carved and painted on the boulders, caves and rock shelters of the Tadrart Acacus valleys.

The Tadrart Acacus in historical and modern times: the significance of the archaeological research

The Tadrart Acacus massif is of particular importance to the understanding of both local and trans-Saharan cultural trajectories over the past three millennia. The Acacus is set at the very centre of the Sahara, close to the oasis of Ghat and that of Al Awaynat, and about 300 kilometres from the heartland of the Garamantian kingdom, the relatively lush area of the Wadi el Ajal. It hosts a unique set of rock art sites that were added to UNESCO’s World Heritage list in 1985. These sites are often located in physical connection with archaeological deposits in caves and rock shelters. The massif is seen as a key area for studies of Africa’s past: several archaeological deposits have been tested in the past fifty years,4 and some were subjected to excavations.5 Its primary role in African prehistoric archaeology has been further confirmed by some recent discoveries of the Middle Neolithic age (c. sixth to fifth millennium before present) — such as the earliest dairying in Africa and an outstanding set of cattle burials — that received attention in the popular media as well as in academic circles.6

In the last fifteen years, the work of the Libyan-Italian Archaeological Mission of the local Department of Archaeoloy (DoA) and Sapienza University of Rome focused on the village and adjacent necropolis of Fewet,7 the fortified settlement of Aghram Nadharif (close to the Ghat area),8 some funerary monuments in the Wadi Tanezzuft,9 and on two forts located east of the Acacus massif.10 The still-inhabited mountain range of the Tadrart Acacus, cut by dozens of dry river valleys, has been largely neglected. However, in recent years, the development of ethnoarchaeological studies11 has further enlarged the aims of the DoA-Sapienza research to include modern and contemporary civilisations. In fact, the study of human-environment interaction in such a hyper arid region has become one of the hottest topics in the debate around sustainable development in dry lands. The impact of social science in the design and development of possible solutions to mitigate the effects of drought in dry regions has been low and scarcely significant so far. Major involvement from social scientists in the issue of sustainable development has been again recently voiced at the international level.12 There is a strong need to develop integrated approaches focused on the study of the indigenous knowledge in arid lands, by the adoption of archaeological, geoarchaeological, historical and anthropological tools to unveil the practices of variable resource management by desert communities.

The long tradition of scientific research in the area makes the Tadrart Acacus an ideal place to adopt a multi-pronged approach focusing on landscape, where data from historical and modern times are integrated with the study of the ethnographic present.13 These new studies have deeply affected our perception of the whole Acacus landscape, paving the way to more nuanced reasoning about the human-environment interaction in both the modern and historical context.

Materials and methods

Thanks to a major grant from the British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme, the project EAP265: The Tifinagh rock inscriptions in the Tadrart Acacus Mountains (southwest Libya): An Unknown Endangered Heritage14 represented the first research focused on this peculiar type of archaeological and epigraphic evidence. The use of Tifinagh characters in North Africa may date back to the first half of the first millennium BC.15 These types of signs, still used by contemporary Tuareg, were adopted to write down different Libyco-Berber languages or idioms (Table 1.1). This explains why current Kel Tadrart Tuareg are often unable to read the ancient Tifinagh texts of the Tadrart Acacus. The origin of this African alphabet is debated and discussed on the basis of the studies carried out on the Mediterranean and the Atlantic façades of North Africa.16

Table 1.1 Tifinagh alphabet, from Aghali-Zakara (1993 and 2002): Hoggar (Algeria); Aïr (Niger); Ghat (Libya); Azawagh (Niger-Mali); and Adghagh (Mali).

The Saharan texts, however, have been rarely subjected to systematic recording and publication.17 In the absence of any bilingual texts, the translation of Saharan inscriptions is extremely difficult. However, some attempts have been made, and they seem to confirm that Tifinagh was mainly used to write short personal messages, epitaphs, and “tags”.18 A further hurdle to translation is that these texts normally feature metaphors — alterations of signs and/or words — so that they become hardly readable. It has been suggested that some inscriptions have a “ludique” character whose aim was precisely to prevent the comprehension by anyone other than the author and the recipient(s) of the message.19 Tifinagh texts present interpretive problems similar to those raised by Saharan rock art, such as its interpretation, meaning, and chronology. Therefore, the EAP265 project aimed to: 1) create a database of all the available data regarding Tifinagh inscriptions noticed in the past surveys; 2) digitally record known and unknown Tifinagh sites on the ground; and 3) make available an open access dataset.

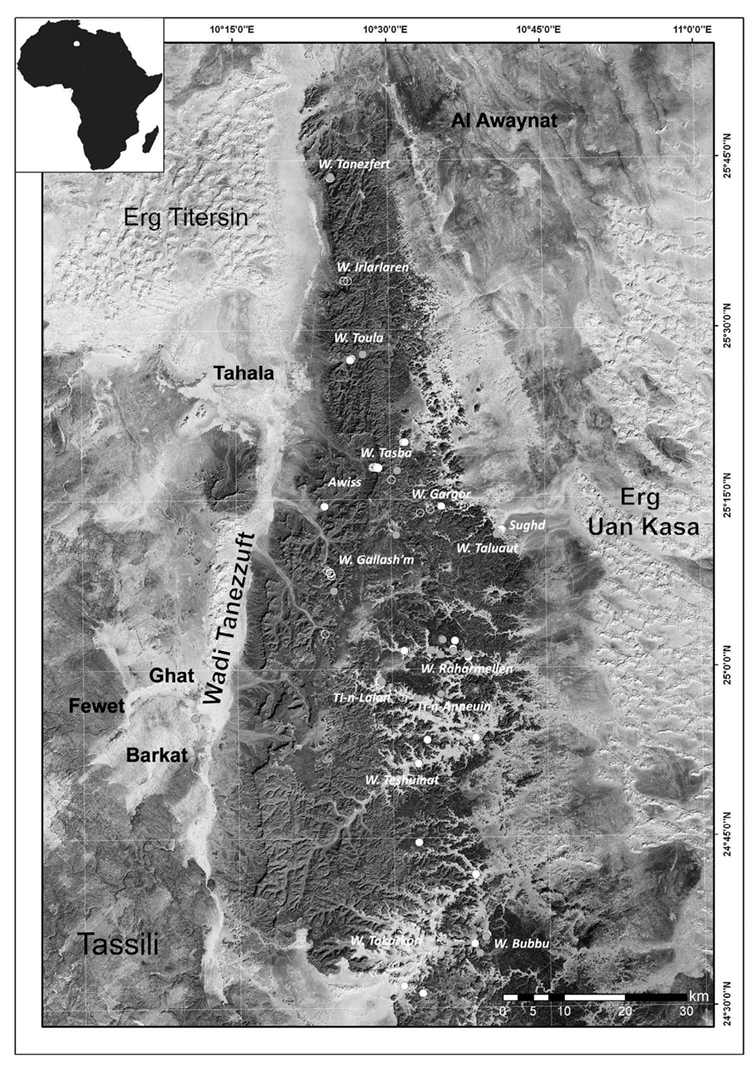

During the fieldwork we carried out in October to December 2009 we identified 124 sites (Table 1.2; Fig. 1.2). Our landscape approach included two main field methods. The first method was geomorphologically inspired, and featured visits to the most relevant water points and other locations of interest such as passageways and what we later discovered to be crop fields. In the Tadrart Acacus, water occurs in the form of gueltas (rock pools where rainfall gathers) and wells. Gueltas have been subjected to investigation by the “Saharan Waterscapes” project, as have etaghas (empty spaces where crops can be raised after floods).20 The aqbas (passageways) that connect the western oases (Tahala, Ghat, Barkat and Fewet) to the valleys of the Tadrart Acacus, have been surveyed, since these are still to this day a key element of the Acacus landscape. Those mountain trails feature variable gradients and climb for up to 300 metres. In addition, some of the Kel Tadrart elders showed us a variety of previously unknown sites.

Table 1.2 List of the sites recorded (adapted from Biagetti et al., 2012). Site types are open-air (O-A), rock shelters (RS), and caves (C).

Technique includes pecking (P), carving (C), pecking and further carving (PC), and painting (Pa). Chronology features pre-Islamic (P-I; early first millennium BC - 700 CE); Islamic (I; CE 700 - 1500 CE) and Modern (M; CE 1500 - present).

|

ID |

N |

E |

area |

context |

site type |

support |

N of sur- |

signif- |

tech- |

chro- |

|

09/01 |

25°34’18.91’’ |

10°26’03.16’’ |

W. Irlarlaren |

wadi |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/02 |

25°34’17.76’’ |

10°25’38.93’’ |

W. Irlarlaren |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/03 |

25°34’17.98’’ |

10°25’38.75’’ |

W. Irlarlaren |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/04 |

25°43’28.78’’ |

10°24’27.79’’ |

W. Irlarlaren |

wadi |

O-A |

boulder |

1 |

high |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/05 |

25°43’26.80’’ |

10°24’26.64’’ |

W. Tanezfert |

wadi |

O-A |

boulder |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/06 |

25°43’26.87’’ |

10°24’26.42’’ |

W. Tanezfert |

wadi |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/07 |

25°43’26.90’’ |

10°24’26.24’’ |

W. Tanezfert |

wadi |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/08 |

25°43’35.33’’ |

10°24’27.43’’ |

W. Tanezfert |

wadi |

O-A |

boulder |

1 |

very high |

P,C,PC |

I |

|

09/09 |

25°43’32.70’’ |

10°24’28.62’’ |

W. Tanezfert |

wadi |

O-A |

boulder |

1 |

very high |

P,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/10 |

25°27’27.00’’ |

10°26’22.88’’ |

W. Toula |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

high |

C |

n.a. |

|

09/11 |

25°27’19.40’’ |

10°26’15.32’’ |

W. Toula |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

high |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/12 |

25°27’19.94’’ |

10°26’12.70’’ |

W. Toula |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

high |

P |

I – M |

|

09/13 |

25°14’24.32’’ |

10°23’35.16’’ |

W. Toula |

aqba |

O-A |

boulder |

1 |

high |

P,C |

I |

|

09/14 |

25°08’40.85’’ |

10°23’46.54’’ |

W. Ghallasc’m |

wadi |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

average |

C |

I |

|

09/15 |

25°08’30.37’’ |

10°24’03.35’’ |

W. Ghallasc’m |

wadi |

O-A |

boulder |

1 |

average |

P |

M |

|

09/16 |

25°08’27.89’’ |

10°24’05.15’’ |

W. Ghallasc’m |

wadi |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/17 |

25°08’14.86’’ |

10°24’09.22’’ |

W. Ghallasc’m |

wadi |

O-A |

boulder |

1 |

average |

PC |

n.a. |

|

09/18 |

25°06’54.79’’ |

10°24’24.15’’ |

W. Ghallasc’m |

wadi |

O-A |

boulder |

1 |

very high |

P,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/19 |

25°06’55.01’’ |

10°24’24.51’’ |

W. Ghallasc’m |

wadi |

O-A |

boulder |

1 |

high |

P,C,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/20 |

25°06’54.32’’ |

10°24’24.44’’ |

W. Ghallasc’m |

wadi |

O-A |

boulder |

1 |

very high |

P,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/21 |

25°06’53.82’’ |

10°24’24.73’’ |

W. Ghallasc’m |

wadi |

O-A |

boulder |

1 |

very high |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/22 |

24°55’43.18’’ |

10°10’49.54’’ |

W. Tanezzuft |

wadi |

O-A |

bedrock |

1 |

very high |

P,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/23 |

25°03’05.44’’ |

10°23’31.05’’ |

W. Ghallasc’m |

wadi |

O-A |

boulder |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/24 |

25°17’49.85’’ |

10°28’15.60’’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

high |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/25 |

25°17’49.63’’ |

10°28’16.78’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

high |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/26 |

25°17’50.60’’ |

10°28’19.77’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

high |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/27 |

25°17’50.64’’ |

10°28’22.30’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

high |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/28 |

25°17’50.68’’ |

10°28’22.47’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

high |

P,PC |

I |

|

09/29 |

25°17’50.39’’ |

10°28’23.55’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

boulder |

1 |

average |

P |

I |

|

09/30 |

25°17’49.81’’ |

10°28’24.88’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

boulder |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/31 |

25°17’50.53’’ |

10°28’33.31’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

boulder |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/32 |

25°17’50.20’’ |

10°28’33.56’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

high |

P |

I |

|

09/33 |

25°17’49.99’’ |

10°28’35.40’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

high |

P |

I |

|

09/34 |

25°17’49.96’’ |

10°28’35.47’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

high |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/35 |

25°17’50.28’’ |

10°28’35.68’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/36 |

25°17’48.44’’ |

10°28’38.20’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

boulder |

1 |

high |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/37 |

25°17’49.06’’ |

10°28’40.08’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

average |

P |

I |

|

09/38 |

25°17’49.20’’ |

10°28’40.44’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/39 |

25°17’49.34’’ |

10°28’40.69’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

ID |

N |

E |

area |

context |

site type |

support |

N of sur- |

signif- |

tech- |

chro- |

|

09/40 |

25°17’49.42’’ |

10°28’40.73’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

high |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/41 |

25°17’49.45’’ |

10°28’40.76’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/42 |

25°17’48.95’’ |

10°28’41.88’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

boulder |

1 |

high |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/43 |

25°17’48.73’’ |

10°28’44.11’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

high |

P,C |

n.a. |

|

09/44 |

25°17’48.59’’ |

10°28’44.11’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

high |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/45 |

25°17’48.16’’ |

10°28’44.58’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

high |

P,PC |

Pre-I |

|

09/46 |

25°17’47.47’’ |

10°28’44.65’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

very high |

P,C |

n.a. |

|

09/47 |

25°17’47.69’’ |

10°28’44.58’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/48 |

25°17’47.58’’ |

10°28’44.51’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/49 |

25°17’46.50’’ |

10°28’48.29’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

average |

C |

n.a. |

|

09/50 |

25°17’46.43’’ |

10°28’48.68’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

bedrock |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/51 |

25°17’46.36’’ |

10°28’48.72’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/52 |

25°17’46.28’’ |

10°28’48.76’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

average |

P,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/53 |

25°17’46.36’’ |

10°28’48.86’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

high |

P,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/54 |

25°17’46.50’’ |

10°28’49.44’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

average |

P |

M |

|

09/55 |

25°17’46.57’’ |

10°28’48.83’’ |

W. Tasba |

aqba |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/56 |

25°27’51.01’’ |

10°27’28.01’’ |

Awiss mts |

wadi |

O-A |

wall |

1 |

very high |

P,C,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/57 |

24°31’16.10’’ |

10°32’40.06’’ |

Waltannuet |

guelta |

O-A |

wall |

2 |

high |

P,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/58 |

24°31’56.10’’ |

10°30’50.18’’ |

W. Takarkori |

wadi |

O-A |

wall |

1 |

high |

P |

I |

|

09/59 |

24°31’55.60’’ |

10°30’50.58’’ |

W. Takarkori |

wadi |

O-A |

wall |

1 |

high |

P,PC |

I |

|

09/60 |

24°35’36.89’’ |

10°37’42.89’’ |

W. Bubu |

wadi |

RS |

wall |

3 |

high |

P,C,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/61A |

24°36’23.08’’ |

10°38’53.70’’ |

W. Bubu |

wadi |

O-A |

boulder |

2 |

very high |

P |

M |

|

09/61B |

24°36’23.08’’ |

10°38’53.70’’ |

W. Bubu |

wadi |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/61C |

24°36’23.08’’ |

10°38’53.70’’ |

W. Bubu |

wadi |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

high |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/62 |

24°41’43.40’’ |

10°37’53.90’’ |

W. Anshalt |

wadi |

O-A |

boulder |

1 |

high |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/63 |

24°58’34.07’’ |

10°28’56.06’’ |

Ti-n-Lalan |

etaghas |

RS |

wall |

6 |

very high |

P,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/64 |

24°58’50.27’’ |

10°29’1.932’’ |

Ti-n-Lalan |

etaghas |

O-A |

complex |

3 |

very high |

P,C,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/65 |

24°58’57.04’’ |

10°28’34.24’’ |

Ti-n-Lalan |

etaghas |

O-A |

wall |

1 |

very high |

P,PC |

I – M |

|

09/66 |

24°58’34.40’’ |

10°28’46.20’’ |

Ti-n-Lalan |

etaghas |

O-A |

wall |

1 |

average |

P,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/67 |

24°58’39.68’’ |

10°28’44.04’’ |

Ti-n-Lalan |

etaghas |

O-A |

wall |

1 |

average |

P |

M |

|

09/68 |

24°58’51.82’’ |

10°28’46.70’’ |

Ti-n-Lalan |

etaghas |

O-A |

wall |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/69 |

24°58’56.60’’ |

10°28’44.50’’ |

Ti-n-Lalan |

etaghas |

RS |

wall |

1 |

average |

Pa |

n.a. |

|

09/70 |

24°57’25.20’’ |

10°30’56.23’’ |

Ti-n-Lalan |

etaghas |

O-A |

wall |

1 |

average |

Pa |

I |

|

09/71 |

24°53’47.76’’ |

10°38’02.69’’ |

Ti-n-Lalan |

etaghas |

O-A |

wall |

2 |

high |

C |

I |

|

09/72 |

24°58’54.62’’ |

10°28’59.19’’ |

Ti-n-Lalan |

etaghas |

O-A |

wall |

3 |

very high |

P,C |

Pre-I - I – M |

|

09/73 |

24°57’20.95’’ |

10°32’30.01’’ |

Ti-n-Anneuin |

wadi |

C |

wall |

6 |

very high |

P,Pa |

n.a. |

|

09/74 |

24°34’45.98’’ |

10°38’12.01’’ |

W. Bubu |

guelta |

O-A |

wall |

2 |

very high |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/75A |

24°36’12.49’’ |

10°38’48.76’’ |

Ti-n-Amateli |

guelta |

O-A |

wall |

1 |

very high |

P,C |

n.a. |

|

09/75B |

24°36’12.06’’ |

10°38’47.68’’ |

Ti-n-Amateli |

guelta |

O-A |

wall |

2 |

very high |

P,C |

n.a. |

|

09/76 |

24°44’36.02’’ |

10°32’26.01’’ |

Intriki |

guelta |

O-A |

wall |

8 |

high |

P,C |

I |

|

09/77 |

24°53’41.03’’ |

10°33’21.06’’ |

Tibestiwen |

guelta |

O-A |

wall |

6 |

high |

P,C,PC |

I – M |

|

09/78A |

24°57’43.99’’ |

10°34’44.33’’ |

Iknuen |

guelta |

O-A |

wall |

3 |

very high |

P |

n.a. |

|

ID |

N |

E |

area |

context |

site type |

support |

N of sur- |

signif- |

tech- |

chro- |

|

09/78B |

24°57’44.42’’ |

10°34’42.06’’ |

Iknuen |

guelta |

O-A |

wall |

1 |

very high |

P,C |

n.a. |

|

09/79 |

25°00’56.95’’ |

10°37’24.24’’ |

W. Raharmellen |

wadi |

RS |

wall |

1 |

high |

C,Pa |

n.a. |

|

09/80A |

25°01’43.64’’ |

10°35’54.31’’ |

W. Raharmellen |

wadi |

O-A |

wall |

3 |

very high |

P,C |

n.a. |

|

09/80B |

25°01’43.57’’ |

10°35’55.28’’ |

W. Raharmellen |

wadi |

O-A |

wall |

3 |

high |

P,C,PC |

I |

|

09/80C |

25°01’42.78’’ |

10°35’55.43’’ |

W. Raharmellen |

wadi |

O-A |

wall |

1 |

high |

P,C |

n.a. |

|

09/81 |

25°00’11.95’’ |

10°37’21.47’’ |

W. Raharmellen |

wadi |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/82A |

25°02’35.09’’ |

10°34’50.01’’ |

Tejleteri |

guelta |

O-A |

complex |

15 |

very high |

P,C,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/82B |

25°02’32.24’’ |

10°34’55.23’’ |

Tejleteri |

guelta |

O-A |

wall |

1 |

very high |

P,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/82C |

25°02’31.92’’ |

10°34’55.63’’ |

Tejleteri |

guelta |

O-A |

wall |

1 |

very high |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/83 |

25°01’13.62’’ |

10°37’17.58’’ |

W. Raharmellen |

wadi |

O-A |

wall |

1 |

very high |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/84 |

25°02’26.34’’ |

10°36’07.49’’ |

W. Raharmellen |

guelta |

O-A |

wall |

2 |

high |

P,C |

n.a. |

|

09/85A |

25°01’30.04’’ |

10°35’58.27’’ |

W. Raharmellen |

wadi |

O-A |

wall |

1 |

very high |

P,C |

n.a. |

|

09/85B |

25°01’30.00’’ |

10°35’57.66’’ |

W. Raharmellen |

wadi |

RS |

wall |

2 |

very high |

P,C |

n.a. |

|

09/86 |

25°01’37.49’’ |

10°33’50.76’’ |

W. Raharmellen |

wadi |

RS |

wall |

1 |

very high |

P,C |

n.a. |

|

09/87A |

24°51’37.51’’ |

10°32’25.36’’ |

W. Teshuinat |

wadi |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

high |

P,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/87B |

24°51’37.48’’ |

10°32’25.00’’ |

W. Teshuinat |

wadi |

O-A |

wall |

1 |

high |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/87C |

24°51’38.20’’ |

10°32’24.72’’ |

W. Teshuinat |

wadi |

O-A |

wall |

2 |

high |

PC |

n.a. |

|

09/87D |

24°51’34.67’’ |

10°32’26.88’’ |

W. Teshuinat |

wadi |

RS |

wall |

1 |

high |

PC |

n.a. |

|

09/88 |

24°59’50.82’’ |

10°38’03.70’’ |

W. Raharmellen |

wadi |

RS |

wall |

1 |

very high |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/89A |

25°01’12.43’’ |

10°34’43.60’’ |

W. Raharmellen |

wadi |

O-A |

wall |

2 |

very high |

P,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/89B |

25°01’11.93’’ |

10°34’41.84’’ |

W. Raharmellen |

wadi |

O-A |

wall |

1 |

very high |

PC |

n.a. |

|

09/90 |

25°01’35.22’’ |

10°31’11.17’’ |

W. Raharmellen |

wadi |

O-A |

wall |

1 |

high |

P,PC |

I |

|

09/91 |

25°14’17.81’’ |

10°37’07.61’’ |

W. Gargor |

wadi |

O-A |

boulder |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/92 |

25°14’21.01’’ |

10°34’56.02’’ |

W. Gargor |

wadi |

O-A |

boulder |

1 |

high |

P,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/93 |

25°14’4.596’’ |

10°33’50.32’’ |

W. Gargor |

wadi |

O-A |

wall |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/94 |

25°13’45.98’’ |

10°32’52.11’’ |

W. Gargor |

wadi |

O-A |

wall |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/95 |

25°11’51.32’’ |

10°30’31.03’’ |

W. Gargor |

wadi |

O-A |

wall |

1 |

very high |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/96 |

25°11’55.64’’ |

10°40’24.16’’ |

Sughd |

well |

O-A |

wall |

24 |

very high |

P,C,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/97 |

25°12’00.86’’ |

10°40’31.26’’ |

W. Taluaut |

wadi |

O-A |

boulder |

1 |

high |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/98 |

25°12’16.99’’ |

10°40’43.42’’ |

W. Taluaut |

wadi |

O-A |

boulder |

1 |

high |

P,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/99 |

25°12’13.64’’ |

10°40’45.73’’ |

W. Taluaut |

wadi |

O-A |

bedrock |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/100 |

25°11’59.35’’ |

10°40’30.47’’ |

W. Taluaut |

wadi |

O-A |

boulder |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/101 |

25°11’58.96’’ |

10°40’29.46’’ |

W. Taluaut |

wadi |

O-A |

boulder |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/102 |

25°11’58.13’’ |

10°40’28.38’’ |

W. Taluaut |

wadi |

O-A |

boulder |

1 |

average |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/103 |

25°11’57.80’’ |

10°40’27.01’’ |

W. Taluaut |

wadi |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

average |

P,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/104 |

25°11’56.58’’ |

10°40’26.08’’ |

W. Taluaut |

wadi |

O-A |

slab |

1 |

high |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/105 |

25°11’54.96’’ |

10°40’20.10’’ |

W. Taluaut |

wadi |

O-A |

wall |

1 |

high |

P |

n.a. |

|

09/106 |

25°11’50.17’’ |

10°40’17.14’’ |

W. Taluaut |

wadi |

O-A |

wall |

4 |

very high |

P,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/107 |

25°17’30.98’’ |

10°30’40.90’’ |

Ti-n-Tararit |

guelta |

O-A |

wall |

2 |

very high |

P,C,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/108 |

25°16’42.82’’ |

10°30’6.084’’ |

Awiss mts |

wadi |

RS |

wall |

1 |

average |

P,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/109 |

25°20’00.10’’ |

10°31’19.06’’ |

Awiss mts |

wadi |

RS |

wall |

2 |

high |

P,C,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/110 |

25°20’01.03’’ |

10°31’27.51’’ |

W. Ti-n-Torha |

wadi |

RS |

wall |

3 |

high |

P,C,PC |

n.a. |

|

09/111 |

25°16’28.31’’ |

10°34’57.25’’ |

W. Tehet |

wadi |

RS |

wall |

1 |

very high |

P,C,PC |

n.a. |

Fig. 1.2 Map of the Tadrart Acacus with the sites recorded for the Endangered Archives Programme sorted by significance. White circle: average; white dot: high; grey dot: very high (adapted from Biagetti et al., 2012).

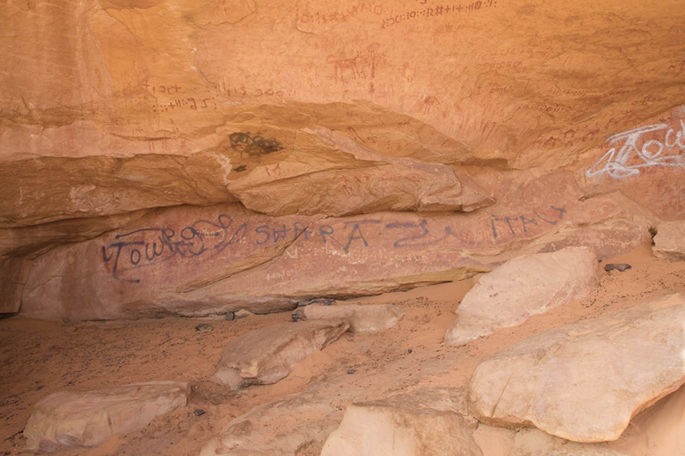

Tifinagh texts of the Tadrart Acacus are carved and painted onto isolated boulders, rocky flanks, and rock shelter walls, and are often characterised by uneven spatial patterns (Fig. 1.3). This raises the issue of how to define a “site” and how to digitally record sets of lines and signs distributed on several uneven stony surfaces. We designed a hierarchical system: a single Tifinagh letter or complex text featuring a clearly recognisable spatial consistency was defined as “site” and progressively labelled from 09/01 to 09/111.21 The whole archive was ultimately given to the largest database of African rock art, the African Rock Art Digital Archive, not only to preserve but also to foster new studies on the recorded evidence.22

Fig. 1.3 An example of Tifinagh inscription, site 09/87B (EAP265/1/87B).

Photo by R. Ceccacci, CC BY.

The sites and their setting in a historical perspective

All the Tifinagh sites found in the Tadrart Acacus are included in Table 1.1, with data for the identification of the sites, their coordinates and local toponyms; the most relevant geomorphological data; and archaeological and epigraphic information on the type of site, technique, significance and, when available, chronology. The significance of each site was established on the basis of the size of the inscriptions, testifying to the presence of repeated rock markings and/or complex texts. We deduced chronology from the study of first names occurring in the Tifinagh texts.23

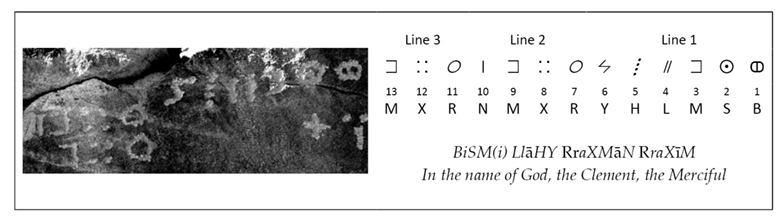

Fig. 1.4 The Basmala inscription from site 09/67.

Most of the Tifinagh sites include lists of anthroponyms that in some cases are veritable genealogies going back several generations. More than 135 anthroponymic sequences have been identified so far, and site 09/92 is likely to include the longest genealogy so far known in Libyco-Berber epigraphy.24 After the spread of Islam, the Tuareg and other Berber populations adopted Arab names. This “neo-anthroponymy” includes names borrowed from the most prominent personalities of Islam; the Tadrart Acacus, for example, features the names Mohamed (37 cases), Ahmed (26), Moussa (17), Fatima (16), and Ali (16). The Basmala (a phrase used by Muslims, often translated as “in the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful”) occurs once (Fig. 1.4). Occasionally, love messages have been recorded as well. In four cases, place names have been recognised: these are TDMKT (read Tadmekka, site 09/85A), likely referring to Es-Souk, an important centre located in Mali and traditionally inhabited by Tuareg; MK(T) (read Mecca, site 09/92), the Islamic Holy City; TŠWNT (read Teshuinat, the largest Acacus wadi, in 09/73, Fig. 1.5); and TGMYT (read Tagamayet “place where there is some couch grass”, in Wadi Raharmellen, 09/88). Furthermore, the same graphist (i.e. author) named Biya, can be recognised in various sites where he left his signature: the same author has written text in at least four sites throughout the Tadrart Acacus, including 09/63 located in the Ti-n-Lalan area, 09/90 in wadi Raharmellen (c. 7 km northeast from site 09/63), 09/37 in wadi Tasba (c. 35 km north from site 09/63), and 09/82A in Tejleteri (c. 13 km east-north-east from site 09/63).

Fig. 1.5 Site 09/73 features the toponym of Teshuinat (TŠWNT).

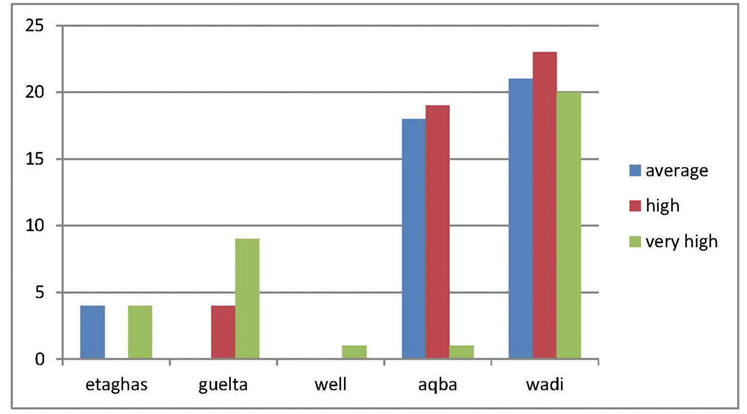

The short discussion above shows the potential of this kind of study. Besides that, it is the place of these inscriptions that holds relevance for the comprehension of the whole landscape. It is often noted that Tifinagh texts are usually short and there is no literature published in Tifinagh characters. Whilst one may accept this reductionist view on Tifinagh on the whole, the case of the Tadrart Acacus allows us to go beyond the intrinsic limits of these kinds of inscriptions, by adopting a landscape approach. As Christopher Chippindale and George Nash argued in a synthesis of different approaches to rock art, it is likely that the firmest attribute of human-made signs on the stone is their place.25 The position in the space of the Tifinagh signs thus represents a solid starting point. The 124 Tifinagh sites recorded (Table 1.2) are found in a variety of landscape contexts, occurring along aqbas (30.6%), wadis (51.6%), gueltas (10.5%), etaghas (6.5%), and the only well (0.8%) (Table 1.3). Most of the Tifinagh evidence has been recorded in open air sites (111, around 90%), and only a small percentage comes from caves and rock shelters (Table 1.4). Nearly half of the Tifinagh inscriptions were carved or painted on boulders and slabs, the rest occurring on the sandstone walls of rocky cliffs (Table 1.5). Most of the evidence (79.9%) consists of single-surfaced sites, whereas multi-surfaced sites occur less frequently (Table 1.6). Regarding the significance, the three categories (average, high, very high) are evenly distributed (Table 1.7). The four types of techniques were unevenly used, with pecking largely occurring in the majority of cases (>60%) (Table 1.8). Occasionally a mixed technique featuring first pecking and then a regularisation obtained by carving was recorded. The case of painting is different: the type of surface was not among the causes that drove that specific choice. It is worth stressing that three out of four painted inscriptions occurred in cave (1) and rock shelters (2). Unfortunately, the chronology of the inscriptions has been determined so far only for 19.4% of the sites.

Table 1.3 Context of sites according to the most relevant element of landscape for human occupations.

|

context |

N |

% |

|

aqba |

38 |

30.6 |

|

etaghas |

8 |

6.5 |

|

guelta |

13 |

10.5 |

|

wadi |

64 |

51.6 |

|

well |

1 |

0.8 |

|

total |

124 |

100 |

Table 1.4 Type of sites.

|

type |

N |

% |

|

open-air |

111 |

89.5 |

|

rock shelter |

12 |

9.7 |

|

cave |

1 |

0.8 |

|

total |

124 |

100 |

Table 1.5 Support of sites.

|

support |

N |

% |

|

boulder |

26 |

21.0 |

|

slab |

42 |

33.9 |

|

bedrock |

3 |

2.4 |

|

wall |

51 |

41.1 |

|

complex |

2 |

1.6 |

|

total |

124 |

100 |

Table 1.6 Number of surfaces.

|

N of surfaces |

N |

% |

|

1 |

99 |

79.8 |

|

2 |

11 |

8.9 |

|

3 |

7 |

5.6 |

|

4 |

1 |

0.8 |

|

6 |

3 |

2.4 |

|

8 |

1 |

0.8 |

|

15 |

1 |

0.8 |

|

24 |

1 |

0.8 |

|

total |

124 |

100 |

Table 1.7 Significance of sites

|

significance |

N |

% |

|

average |

43 |

34.7 |

|

high |

46 |

37.1 |

|

very high |

35 |

28.2 |

|

total |

124 |

100 |

Table 1.8 Techniques (*total here is not 124, since various techniques may occur at a single site)

|

technique |

N |

% |

|

pecked |

113 |

60.8 |

|

carved |

31 |

16.7 |

|

pecked+carved |

38 |

20.4 |

|

painted |

4 |

2.2 |

|

total |

186* |

100 |

As a whole, the Acacus repertoire looks rather modern. The Tadrart Acacus is inhabited by a single lineage of Tuareg, the Kel Tadrart, whose existence has been noted since the first colonial-period reports.26 There is no evidence that in the last century other groups regularly frequented the Acacus, although there may have been occasional “incursions”. If this suggests that the Kel Tadrart are the likely authors of the modern inscriptions, it does not tell us who wrote the texts in the Islamic age. The low proportion of the sites for which dating can be securely determined makes development of further historical hypotheses difficult.

Fig. 1.6 Significance and context of Tifinagh sites.

Going back to our landscape approach, a considerable proportion of high importance Tifinagh texts are located in sites that have a connection to water, whether the gueltas, the etaghas, or the sole well (Fig. 1.6). The aqbas also have a large number of sites, but these are generally less complex and their texts shorter than those recorded around water. Even so, these texts can be used to better understand the use of landscape by its inhabitants. For example, in the Tadrart Acacus there are at least six main mountain trails that connect the large wadis of the east to the oasis set along the wadi Tanezzuft to the west of the Tadrart Acacus (see Fig. 1.2). The occurrence of Tifinagh is a clear sign of the use of a determined route (Fig. 1.7), as in the case of wadi Tasba.

Fig. 1.7 3D view of the aqba of wadi Tasba on the western escarpment of the Tadrart Acacus

(map from Google Earth).

In spite of their relatively low number, the sites connected with water are far more complex in the Tadrart Acacus. Research undertaken by Savino di Lernia and his colleagues highlighted the role of the gueltas — the traditional water reservoirs that still play a key role in shaping the Kel Tadrart — in the inhabitants’ successful adaptation to the rugged environment of the Acacus massif.27

Fig. 1.8 Site 09/74, close to the guelta of wadi Bubu (EAP265/1/74).

Photo by R. Ceccacci, CC BY.

It has been demonstrated that the Kel Tadrart settlements are located close to gueltas;28 however, not all the “main gueltas”,29 i.e. the gueltas recognised as very important for water supply by the current Kel Tadrart, feature Tifinagh inscriptions. As a matter of fact, only half of the gueltas recorded for the EAP project corresponded to the “main gueltas” as identified by the current Kel Tadrart Tuareg (Fig. 1.8). On the other hand, other gueltas with Tifinagh were not included among the main gueltas. Similarly, among the four etaghas recognised by di Lernia et al. as locales for temporary cultivation in the case of exceptional floods,30 only one — Ti-n-Lalan (Fig. 1.9) — bears a significant number of Tifinagh inscriptions at the edges of the crop field. The case of the etaghas looks quite similar to that of the gueltas. It is intriguing to note that dates of inscriptions at one site can range from pre-Islamic, through Islamic to modern times (Table 1.2). This raises the issue of the enduring importance of this locale from historical, and possibly late prehistoric, to the present day.31 The discovery of the remains of a settlement inhabited in 2005 testifies to the current use of this area by the Kel Tadrart Tuareg.32

Fig. 1.9 Etaghas Ti-n-Lalan: the white line borders the etaghas, the dots indicate the Tifinagh sites, and the triangle refers to the Kel Tadrart settlement (map from Google Earth, adapted from di Lernia et al., 2012).

Recent research shows that the late Holocene rock art follows a clear pattern of spatial distribution in the Tadrart Acacus.33 The later phase that includes the so-called “Camel style” can be considered as roughly contemporary to the earliest Tifinagh inscriptions in the Tadrart Acacus. Dating rock art, like dating Tifinagh, poses many challenges. However, scholars agree that the Camel phase began before the end of the Garamantian age (AD 700) and further developed until modern times.34 In some areas of the Acacus, concentrations of Camel style subjects have been identified35 and these overlap with several Tifinagh sites, with the exception of those set on the aqbas along the western side of the mountain. According to di Lernia and Gallinaro, 83.5% of Camel phase rock art is to be found within caves and/or rock shelters, whilst the Tifinagh inscriptions mainly appear on open air sites (89.5%).36 An anthropogenic deposit from a rock shelter along wadi Teshuinat (central Acacus) allowed to obtain the C14 date (1260±60 uncal. BP, i.e. some 1,000 years ago) placing it in the Islamic period.37 It is the only securely dated material in the Acacus valleys but, given the occurrence of Camel phase rock art, it seems likely that the top archaeological layers in Tifinagh inscription sites would yield a similar date.

Changing landscape: the role of the Tifinagh

Tadrart Acacus is often thought of as being poorly frequented in historical and modern times, but in fact resilient human groups have developed a variety of adaptive strategies to flourish in its hyper-arid conditions. The Tifinagh evidence adds previously unknown data to our understanding of the cultural landscape of the massif over the past two millennia. In spite of the issues of both dating and translation, the Tifinagh inscriptions allow us to distinguish between different forms of frequentation in the Tadrart Acacus, at least in historical and modern times. Humans have used rock art to mark their presence in this area at least since early Holocene times. In spite of the socio-cultural context that gave birth to rock markings, the subjects depicted or inscribed in the Tadrart Acacus articulate and give formal visibility to the relationship between humans and the landscape. The fact that some aqbas were marked by Tifinagh inscriptions alone, with no rock art, suggests that the texts were marking a passage, the movement of people through the rugged mountain trails. These people were likely to be connected with the small-scale trade traditionally linking the Kel Tadrart to the oases on the Tanezzuft. It is no surprise, then, that the most relevant aqbas are those on the northern sector of the Tadrart Acacus, intercepting and overlapping with longer regional east-west routes. These trade routes were in use from Garamantian times onwards.38

As well as being markers of human movement, the Tifinagh inscriptions of the Tadrart Acacus are also signs of permanence, as indicated by their occurrence along some of the largest and most relevant wadis, such as Raharmellen and Teshuinat. These are the places where better pastures are to be found,39 and they continue to be the sites of current Kel Tadrart occupation. The discovery that cultivation was practiced in the etaghas has opened a window on what was until recently thought to be an exclusively pastoral landscape. Overriding the traditional dialectic between the desert and the sown, between nomads and farmers, the etaghas of the Acacus offer promising avenues of interpretation of the cultural trajectories in arid lands.40 Not dissimilarly, the use of the gueltas is highlighted by the presence of Tifinagh. From an ethnoarchaeological perspective, it is highly significant to unveil the relationships between current inhabitants of the Acacus and the major features of the landscape. This is relevant to our view of a previously undifferentiated landscape, punctuated by dozens of gueltas, and cut by a number of aqbas. The study of the Tifinagh evidence is thus as significant as that of rock art and other archaeological and historical data. The Tifinagh inscriptions emerge as one of the most tangible remains of the heritage of intangible knowledge that has allowed humans to inhabit the harsh land of the Tadrart Acacus in recent and modern times.

The current situation in the Sahara is likely to pose new threat to the remains of the past (see Fig. 1.10) in the desert. Acts of vandalism occurred in 2009 and others have been recently reported.41 Nevertheless, this broad set of traditional technologies deserves to be understood and preserved, and further taken into account by stakeholders charged with the design of development plans in arid lands. Human groups living in extreme environments have developed effective strategies to survive and minimise the risks that arise from drought and continual fluctuation of natural resources. Far from representing the shadow of past civilisations, the contemporary inhabitants of Sahara are the evidence of continued successful adaptation over the last 3,000 years. In this spirit, a new season of investigation in the now barely accessible central Sahara would be most welcome, at least for focusing on the materials so far collected and integrated with remote sensing techniques.42

Fig. 1.10 Site 09/73, Ti-n-Anneuin, vandalised in 2009 (EAP265/1/73).

Photo by R. Ceccacci, CC BY.

References

Aghali-Zakara, Mohamed, “Les lettres et les chiffres: écrire en Berbère”, in À la croisée des études libyco-berbères. Mélanges offerts à Paulette Galand-Pernet et Lionel Galand, ed. by Jeannine Drouin and Arlette Roth (Paris: Geuthner, 1993), pp. 141-57.

—, “Unité et diversité des libyco-berbères (2)”, La lettre du RILB, 8 (2002), 3-4.

—, and Jeannine Drouin, Inscriptions rupestres libyco-berbères Sahel nigero-malien (Geneva: Droz, 2007).

—, and Jeannine Drouin, “Écritures libyco-berbères: vingt-cinq siècles d’histoire”, in L’aventure des écritures: naissances, ed. by Anne Zali and Annie Berthier (Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 1997), pp. 99-111.

Ait Kaci, Ali, “Recherche sur l’ancêtre des alphabets libyco-berbères”, Libyan Studies, 38 (2007), 13-37.

Barich, Barbara E., “La serie stratigrafica dell’Uadi Ti-N-Torha (Acacus, Libia)”, Origini, 8 (1974), 7-157.

—, “The Uan Muhuggiag Rock Shelter”, in Archaeology and Environment in the Libyan Sahara: The Excavations in the Tadrart Acacus, 1978-1983, ed. by Barbara E. Barich (Oxford: BAR International Series, 1987), pp. 123-219.

Barnett, Tertia and David Mattingly, “The Engraved Heritage: Rock-Art and Inscriptions”, in The Archaeology of Fazzan: Volume 1. Synthesis, ed. by David J. Mattingly (London: The Society for Libyan Studies, 2003), pp. 279-326.

Biagetti, Stefano, Ethnoarchaeology of the Kel Tadrart Tuareg: Pastoralism and Resilience in Central Sahara (New York: Springer, 2014).

—, Ali Ait Kaci, Lucia Mori and Savino di Lernia, “Writing the Desert: The ‘Tifinagh’ Rock Inscriptions of the Tadrart Acacus (South-West Libya)”, Azania, 47/2 (2012), 153-74.

—, and Jasper Morgan Chalcraft, “Imagining Aridity: Human-Environment Interactions in the Acacus Mountains, South-West Libya”, in Imagining Landscapes: Past, Present, and Future, ed. by Monica Janowski and Tim Ingold (Farnham: Asghate, 2012), pp. 77-95.

—, and Savino di Lernia, “Reflections on the Takarkori Rockshelter (Fezzan, Libyan Sahara)”, in On Shelter’s Ledge: Histories, Theories and Methods of Rockshelter Research, ed. by Marcel Kornfeld, Sergey Vasil’ev and Laura Miotti (Oxford: Archaeopress, 2007), pp. 125-32.

—, and Savino di Lernia, “Combining Intensive Field Survey and Digital Technologies: New Data on the Garamantian Castles of Wadi Awiss, Acacus Mts., Libyan Sahara”, Journal of African Archaeology, 6/1 (2008), 57-85.

—, and Savino di Lernia, “Holocene Deposits of Saharan Rock Shelters: The Case of Takarkori and Other Sites from the Tadrart Acacus Mountains (Southwest Libya)”, African Archaeological Review, 30/3 (2013), 305-38.

Camps, Gabriel, “Recherches sur les plus anciennes inscriptions libyques de l’Afrique du nord et du Sahara”, Bulletin Archéologique du C.T.H.S., n.s. (1974-1975), 10-11 (1978), 145-66.

Castelli, Roberto, Maria Carmela Gatto, Mauro Cremaschi, Mario Liverani and Lucia Mori, “A Preliminary Report of Excavations in Fewet, Libyan Sahara”, Journal of African Archaeology, 3 (2005), 69-102.

Chippindale, Christopher, and George Nash, eds., The Figured Landscapes of Rock-Art: Looking at Pictures in Place (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Cremaschi, Mauro, and Savino di Lernia, “The Geoarchaeological Survey in the Central Tadrart Acacus and Surroundings (Libyan Sahara): Environment and Cultures”, in Wadi Teshuinat: Palaeoenvironment and Prehistory in South-Western Fezzan (Libyan Sahara), ed. by Mauro Cremaschi and Savino di Lernia (Milan: CNR, 1998), pp. 243-325.

—, and Savino di Lernia, “Holocene Climatic Changes and Cultural Dynamics in the Libyan Sahara”, African Archaeological Review, 16 (1999), 211-38.

Di Lernia, Savino, ed., The Uan Afuda Cave: Hunter-Gatherer Societies of the Central Sahara (Florence: All’Insegna del Giglio, 1999).

—, and Marina Gallinaro, “Working in a UNESCO WH Site: Problems and Practices on the Rock Art of the Tadrart Acacus (SW Libya, central Sahara)”, Journal of African Archaeology, 9 (2011), 159-75.

—, Marina Gallinaro and Andrea Zerboni, “Unesco World Heritage Site Vandalized: Report on Damages to Acacus Rock Art Paintings (SW Libya)”, Sahara, 21 (2010), 59-76.

—, and Giorgio Manzi, eds., Sand, Stones, and Bones: The Archaeology of Death in the Wadi Tanezzuft Valley (5000-2000 BP) (Florence: All’Insegna del Giglio, 2002).

—, Isabella Massamba N’siala, and Andrea Zerboni, “‘Saharan Waterscapes’: Traditional Knowledge and Historical Depth of Water Management in the Akakus Mountains (SW Libya)”, in Changing Deserts: Integrating People and Their Environment, ed. by Lisa Mol and Troy Sternberg (Cambridge: White Horse Press, 2012), pp. 101-28.

—, Mary Ann Tafuri, Marina Gallinaro, Francesca Alhaique, Marie Balasse, Lucia Cavorsi, Paul D. Fullagar, Anna Maria Mercuri, Andrea Monaco, Alessandro Perego and Andrea Zerboni, “Inside the ‘African Cattle Complex’: Animal Burials in the Holocene Central Sahara”, PLoS ONE, 8 (2013), e56879, http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.005687

Dunne, Julie, Richard Evershed, Melanie Salque, Lucy Cramp, Silvia Bruni, Kathleen Ryan, Stefano Biagetti and Savino di Lernia, “First Dairying in ‘Green’ Saharan Africa in the 5th Millennium BC”, Nature, 486 (2012), 390-94.

Edwards, David, “Archaeology in the Southern Fazzan and Prospects for Future Research”, Libyan Studies, 32 (2001), 49-66.

Farrujia de la Rosa, José, Werner Pichler and Alain Rodrigue, “The Colonization of the Canary Islands and the Libyco-Berber and Latino-Canarian Scripts”, Sahara, 20 (2009), 83-100.

Field, Cristopher B., Vicente Barros, Thomas F. Stocker and Qin Dahe, eds., Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation: Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

Galand, Lionel, “Du berbère au libyque: une remontée difficile”, Lalies, 16 (1996), 77-98.

—, “L’écriture libyco-berbère”, Sahara, 11 (1999), 143-45.

—, “Un vieux débat: l’origine de l’écriture libyco-berbère”, La lettre de répertoire des inscriprions libyco-berbères, 7 (2001), 1-3.

Gallinaro, Marina, “Saharan Rock Art: Local Dynamics and Wider Perspectives”, Arts, 2 (2013), 350-82.

Garcea, Elena A. A., ed., Uan Tabu in the Settlement History of the Libyan Sahara (Florence: All’Insegna del Giglio, 2001).

Gigliarelli, Ugo, Il Fezzàn (Tripoli: Governo della Tripolitania, Ufficio Studi, 1932).

Liverani, Mario, “Imperialismo, colonizzazione e progresso tecnico: il caso del Sahara libico in età romana”, Studi Storici, 4 (2006), 1003-56.

—, ed., Aghram Nadharif: The Barkat Oasis (Sha ‘Abiya of Ghat, Libyan Sahara) in Garamantian Times (Florence: All’Insegna del Giglio, 2005).

Mattingly, David J., ed., The Archaeology of Fazzan. Volume 1: Synthesis (London: Society for Libyan Studies, 2003).

—, ed., The Archaeology of Fazzan. Volume 2: Site Gazetteer, Pottery and Other Survey Finds (London: Society for Libyan Studies, 2007).

—, ed., The Archaeology of Fazzan. Volume 3: Excavations of C. M. Daniels (London: Society for Libyan Studies, 2010).

Mori, Fabrizio, Tadrart Acacus: arte rupestre e culture del Sahara preistorico (Turin: Einaudi, 1965).

Mori, Lucia, ed., Life and Death of a Rural Village in Garamantian Times: The Archaeological Investigation in the Oasis of Fewet (Libyan Sahara) (Florence: All’Insegna del Giglio, 2013).

Pichler, Werner, Origin and Development of the Libyco-Berber Script (Cologne: Köppe, 2007).

Scarin, Emilio, “Nomadi e Seminomadi del Fezzan”, in Il Sahara Italiano: Fezzan e Oasi di Gat. Parte Prima, ed. by Reale Società Geografica Italiana (Rome: Società Italiana Arti Grafiche, 1937), pp. 518-90.

Wilson, Andrew, “Saharan Trade in the Roman Period: Short-, Medium- and Long-Distance Trade Networks”, Azania, 47/4 (2012), 409-49.

Zerboni, Andrea, Isabella Massamba N’siala, Stefano Biagetti and Savino di Lernia, “Burning without Slashing: Cultural and Environmental Implications of a Traditional Charcoal Making Technology in the Central Sahara”, Journal of Arid Environments, 98 (2013), 126-31.

1 The Archaeology of Fazzan. Volume 1: Synthesis, ed. by David J. Mattingly (London: Society for Libyan Studies, 2003); The Archaeology of Fazzan. Volume 2: Site Gazetteer, Pottery and Other Survey Finds, ed. by David J. Mattingly (London: Society for Libyan Studies, 2007); and The Archaeology of Fazzan. Volume 3: Excavations of C. M. Daniels (London: Society for Libyan Studies, 2010).

2 Aghram Nadharif: The Barkat Oasis (Sha ‘Abiya of Ghat, Libyan Sahara) in Garamantian Times, ed. by Mario Liverani (Florence: All’Insegna del Giglio, 2005); and Life and Death of a Rural Village in Garamantian Times: The Archaeological Investigation in the Oasis of Fewet (Libyan Sahara), ed. by Lucia Mori (Florence: All’Insegna del Giglio, 2013).

3 David Edwards, “Archaeology in the Southern Fazzan and Prospects for Future Research”, Libyan Studies, 32 (2001), 49-66; Mario Liverani, “Imperialismo, colonizzazione e progresso tecnico: il caso del Sahara libico in età romana”, Studi Storici, 4 (2006), 1003-56; and Andrew Wilson, “Saharan Trade in the Roman Period: Short-, Medium- and Long-Distance Trade Networks”, Azania, 47/4 (2012), 409-49.

4 Mauro Cremaschi and Savino di Lernia, “The Geoarchaeological Survey in the Central Tadrart Acacus and Surroundings (Libyan Sahara): Environment and Cultures”, in Wadi Teshuinat: Palaeoenvironment and Prehistory in South-Western Fezzan (Libyan Sahara), ed. by Mauro Cremaschi and Savino di Lernia (Milan: CNR, 1998), pp. 243-325.

5 Fabrizio Mori, Tadrart Acacus: Arte rupestre e culture del Sahara preistorico (Turin: Einaudi, 1965); Barbara E. Barich, “La serie stratigrafica dell’Uadi Ti-N-Torha (Acacus, Libia)”, Origini, 8 (1974), 7-157; Barbara E. Barich, “The Uan Muhuggiag Rock Shelter”, in Archaeology and Environment in the Libyan Sahara: The Excavations in the Tadrart Acacus, 1978-1983, ed. by Barbara E. Barich (Oxford: BAR International Series, 1987), pp. 123-219; Uan Afuda Cave: Hunter-Gatherer Societies of the Central Sahara, ed. by Savino di Lernia (Florence: All’Insegna del Giglio, 1999); Uan Tabu in the Settlement History of the Libyan Sahara, ed. by Elena A. A. Garcea (Florence: All’Insegna del Giglio, 2001); and Stefano Biagetti and Savino di Lernia, “Holocene Deposits of Saharan Rock Shelters: The Case of Takarkori and Other Sites from the Tadrart Acacus Mountains (Southwest Libya)”, African Archaeological Review, 30/3 (2013), 305-38.

6 Julie Dunne et al., “First Dairying in ‘Green’ Saharan Africa in the 5th Millennium BC”, Nature, 486 (2012), 390-94; and Mary Ann Tafuri et al., “Inside the ‘African Cattle Complex’: Animal Burials in the Holocene Central Sahara”, PLoS ONE, 8 (2013), http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0056879.

7 Roberto Castelli, Maria Carmela Gatto, Mauro Cremaschi, Mario Liverani and Lucia Mori, “A Preliminary Report of Excavations in Fewet, Libyan Sahara”, Journal of African Archaeology, 3 (2005), 69-102; and Mori, Life and Death of a Rural Village.

8 Liverani, Aghram Nadharif.

9 Sand, Stones, and Bones: The Archaeology of Death in the Wadi Tanezzuft Valley (5000-2000 BP), ed. by Savino di Lernia and Giorgio Manzi (Florence: All’Insegna del Giglio, 2002).

10 Stefano Biagetti and Savino di Lernia, “Combining Intensive Field Survey and Digital Technologies: New Data on the Garamantian Castles of Wadi Awiss, Acacus Mountains, Libyan Sahara”, Journal of African Archaeology, 6/1 (2008), 57-85.

11 Stefano Biagetti, Ethnoarchaeology of the Kel Tadrart Tuareg: Pastoralism and Resilience in Central Sahara (New York: Springer, 2014); Stefano Biagetti and Jasper Morgan Chalcraft, “Imagining Aridity: Human-Environment Interactions in the Acacus Mountains, South-West Libya”, in Imagining Landscapes: Past, Present, and Future, ed. by Monica Janowski and Tim Ingold (Farnham: Asghate, 2012), pp. 77-95; Savino di Lernia, Isabella Massamba N’siala and Andrea Zerboni, “‘Saharan Waterscapes’: Traditional Knowledge and Historical Depth of Water Management in the Akakus Mountains (SW Libya)”, in Changing Deserts: Integrating People and Their Environment, ed. by Lisa Mol and Troy Sternberg (Cambridge: White Horse Press, 2012), pp. 101-28; and Andrea Zerboni, Isabella Massamba N’siala, Stefano Biagetti and Savino di Lernia, “Burning without Slashing: Cultural and Environmental Implications of a Traditional Charcoal Making Technology in the Central Sahara”, Journal of Arid Environments, 98 (2013), 126-31.

12 Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation: Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, ed. by Christopher Field, Vicente Barros, Thomas F. Stocker and Qin Dahe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

13 Biagetti, Ethnoarchaeology of the Kel Tadrart Tuareg; Biagetti and Chalcraft, “Imagining Aridity”; di Lernia, N’siala and Zerboni, “Saharan Waterscapes”; and Zerboni, N’siala, Biagetti and di Lernia, “Burning Without Slashing”.

15 Mohamed Aghali-Zakara and Jeannine Drouin, “Écritures libyco-berbères: vingt-cinq siècles d’histoire”, in L’aventure des écritures: naissances, ed. by Anne Zali and Annie Berthier (Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 1997), pp. 99-111; Lionel Galand, “L’écriture libyco-berbère”, Sahara, 10 (1999), 143-45.

16 Gabriel Camps, “Recherches sur les plus anciennes inscriptions libyques de l’Afrique du nord et du Sahara”, Bulletin archéologique du C.T.H.S., n.s. (1974-1975), 10-11 (1978), 145-66; José Farrujia de la Rosa, Werner Pichler and Alain Rodrigue, “The Colonization of the Canary Islands and the Libyco-Berber and Latino-Canarian Scrips”, Sahara, 20 (2009), 83-100; Lionel Galand, “Du berbère au libyque: une remontée difficile”, Lalies, 16 (1996), 77-98; Lionel Galand, “Un vieux débat: l’origine de l’écriture libyco-berbère”, La lettre de répertoire des inscriprions libyco-berbères, 7 (2001), 1-3; and Werner Pichler, Origin and Development of the Libyco-Berber Script (Cologne: Köppe, 2007).

17 Mohamed Aghali-Zakara and Jeannine Drouin, Inscriptions rupestres libyco-berbères: Sahel nigero-malien (Geneva: Droz, 2007); Camps; and Pichler.

18 Ali Ait Kaci, “Recherche sur l’ancêtre des alphabets libyco-berbères”, Libyan Studies, 38 (2007), 13-37.

19 Aghali-Zakara and Drouin, Inscriptions rupestres libyco-berbères.

20 Di Lernia, N’siala and Zerboni, “Saharan Waterscapes”.

21 Stefano Biagetti, Ali Ait Kaci, Lucia Mori and Savino di Lernia, “Writing the Desert. The ‘Tifinagh’ Rock Inscriptions of the Tadrart Acacus (South-West Libya)”, Azania, 47/2 (2012), 153-74.

22 The African Rock Art Digital Archive is available at http://www.sarada.co.za

23 Biagetti, Kaci, Mori and di Lernia, “Writing the Desert”.

24 Ibid.

25 Christopher Chippindale and George Nash, “Pictures in Place: Approaches to the Figured Landscape of Rock Art”, in The Figured Landscapes of Rock-Art: Looking at Pictures in Place, ed. by Christopher Chippindale and George Nash (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), pp. 1-36.

26 Biagetti, Ethnoarchaeology of the Kel Tadrart Tuaregi; Ugo Gigliarelli, Il Fezzàn (Tripoli: Governo della Tripolitania, Ufficio Studi, 1932); Mori, Tadrart Acacus; and Emilio Scarin, “Nomadi e seminomadi del Fezzan”, in Il Sahara italiano: Fezzan e Oasi di Gat. Parte prima, ed. by Reale Società Geografica Italiana (Rome: Società Italiana Arti Grafiche, 1937), pp. 518-90.

27 Di Lernia, N’siala and Zerboni, “Saharan Waterscapes”.

28 Ibid., pp. 113-15; Biagetti, Ethnoarchaeology of the Kel Tadrart Tuareg; and Biagetti and Chalcraft, “Imagining Aridity”.

29 Di Lernia, N’siala and Zerboni, “Saharan Waterscapes”.

30 Ibid.

31 Ibid.

32 Ibid., and Biagetti, Ethnoarchaeology of the Kel Tadrart Tuareg, ch. 5.

33 Savino di Lernia and Marina Gallinaro, “Working in a UNESCO WH Site: Problems and Practices on the Rock Art of the Tadrart Acacus (SW Libya, central Sahara)”, Journal of African Archaeology, 9 (2011), 159-75; and Marina Gallinaro, “Saharan Rock Art: Local Dynamics and Wider Perspectives”, Arts, 2 (2013), 350-82.

34 Tertia Barnett and David J. Mattingly, “The Engraved Heritage: Rock-Art and Inscriptions”, in The Archaeology of Fazzan. Volume 1: Synthesis, ed. by David J. Mattingly (London: Society for Libyan Studies, 2003), pp. 279-326; and di Lernia and Gallinaro, “Working in a UNESCO WH Site”.

35 Di Lernia and Gallinaro, “Working in a UNESCO WH Site”, Fig. 6, p. 170.

36 Ibid., Table 2, p. 167.

37 Cremaschi and di Lernia, “The Geoarchaeological Survey in the Central Tadrart Acacus and Surroundings”.

38 Liverani, “Imperialismo, colonizzazione e progresso tecnico”; and Wilson.

39 Biagetti, Ethnoarchaeology of the Kel Tadrart Tuareg, ch. 4.

40 Di Lernia, N’siala and Zerboni, “Saharan Waterscapes”, pp. 117-19.

41 Savino di Lernia, Marina Gallinaro and Andrea Zerboni, “Unesco World Heritage Site Vandalized: Report on Damages to Acacus Rock Art Paintings (SW Libya)”, Sahara, 21 (2010), 59-76, Fig. 10. We were told of further acts of vandalism by Ali Khalfalla, DoA representative in Ghat-Acacus area.

42 The research for this article was funded by a Major Project Grant from the Endangered Archives Programme of the British Library (Savino di Lernia as Principal Investigator), and included in the activities of the Italian-Libyan Archaeological Mission in the Acacus and Messak Sapienza University of Rome and the Libyan Department of Archaeology (Tripoli and Sebha), directed by S. di Lernia and funded by Grandi Scavi di Ateneo (Sapienza), and the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (DGPCC/DGPS) entrusted to S. di Lernia. We thank Lucia Mori, who took part in the research project. We wish to thank Giuma Anag and Salah Agahb, former chairmen of the DoA, for their support of the project, and Saad Abdul Aziz for his help and advice. We are very grateful to Mohammed Hammadani for his contribution in the field. We are indebted to Cathy Collins and Lynda Barraclough from the EAP for their support and co-operation. We express our gratitude to Maja Kominko, who has enthusiastically followed all the editing, showing strong support and patience. Ultimately, we thank the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful and useful comments.