10. Convict labour in early colonial Northern Nigeria: a preliminary study

© Mohammed Bashir Salau, CC BY http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0052.10

Scholars have developed a lively and fruitful interest in the history of slavery and other forms of unfree labour in early colonial Northern Nigeria. Paul E. Lovejoy and Jan Hogendorn have investigated how various measures implemented by the colonial government resulted in the “slow death of slavery”;2 Chinedu N. Ubah has examined how the end of slave trading came about in three stages;3 Alan Christelow has emphasised how Emir Abbas of the Kano Emirate dealt with cases involving emancipation and redemption;4 and Ibrahim Jumare has looked at how the 1936 proclamation marked the beginning of the last phase of domestic slavery in all parts of Northern Nigeria.5 While the history of slavery has attracted the most critical attention, the history of forced labour has not been neglected. Michael Mason, for example, has drawn our attention to the use of forced labour in railway construction,6 while other general studies on wage labour in Northern Nigeria have made considerable reference to either slavery or forced and bonded labour in general.7

Although there is evident interest in the history of slavery and unfree labour in Northern Nigeria, as well as a burgeoning interest in the history of the prison system across Nigeria,8 I am not aware of any comprehensive study on convict labour in the region. I have referred to the employment of convict labour in agricultural production in early colonial Kano, but in a book that focuses primarily on the pre-colonial period.9 Other writers have written comprehensive studies dealing mainly with the post-colonial use of convict labour in other parts of Africa.10 Whereas most extant literature on convict labour focuses on the post-colonial era, Allen Cook’s work on convict labour in South Africa, unlike this study, mainly explores the “relationship of the prison labour system to other aspects of apartheid.”11 This paper seeks to add to the growing literature on convict labour in Africa, among the forms of unfree labour, by introducing to the debate colonial records related to the use of convict labour in early colonial Northern Nigeria.

The colonial records used in this study were written by Frederick Lugard, the first Governor of Northern Nigeria, and other colonial administrators in the region.12 After the British conquest of Northern Nigeria in 1897-1903, Lugard fashioned an administrative system of indirect rule, mainly because Britain was not prepared to bear the cost involved in employing a large number of its citizens as administrators in Africa. Under this system, just a few European officials were able to rule through an agency of native administration. These Europeans often lived in separate quarters and enjoyed many privileges. Over time, the administrators in question promoted many policies and programmes such as railway construction, road construction and cash crop production.13

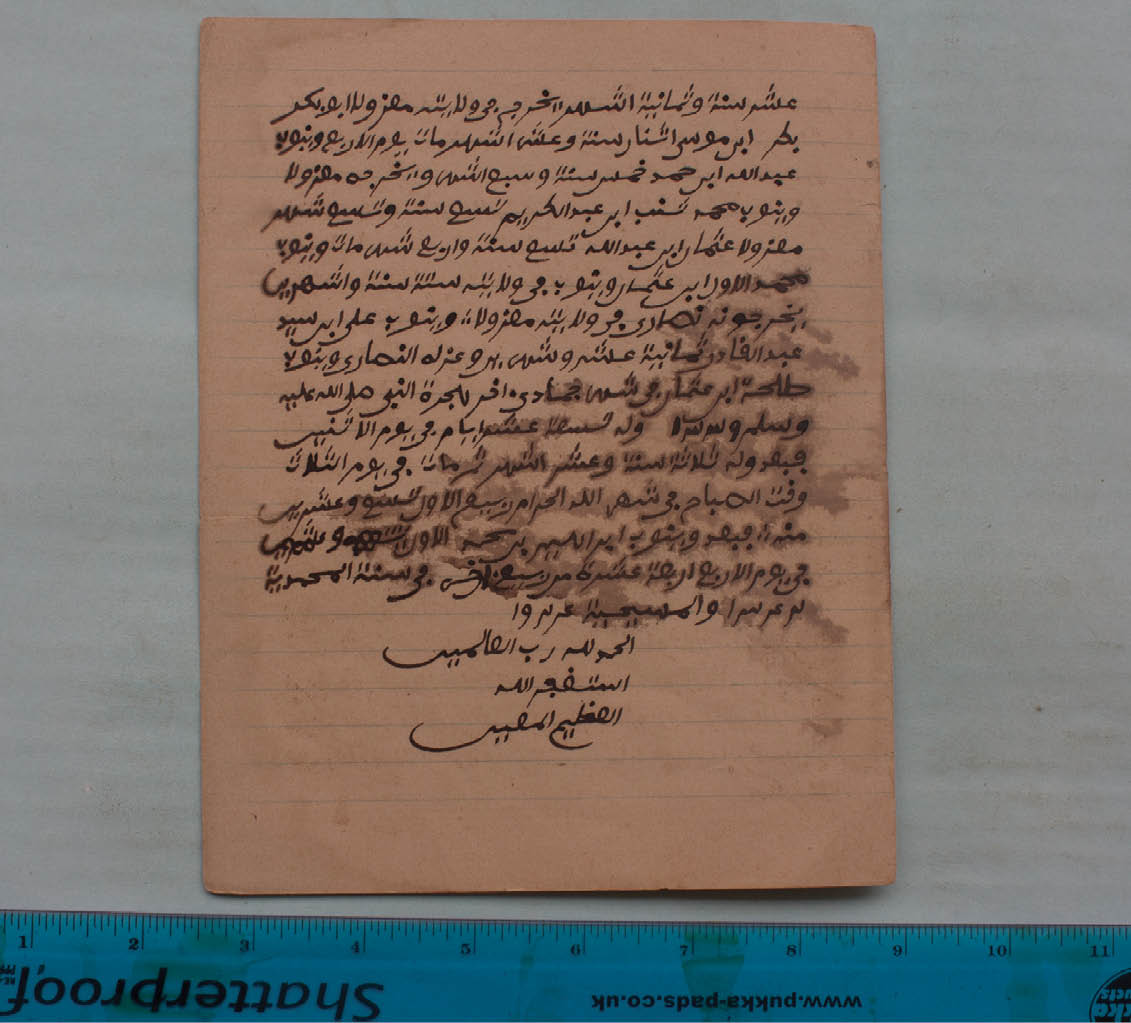

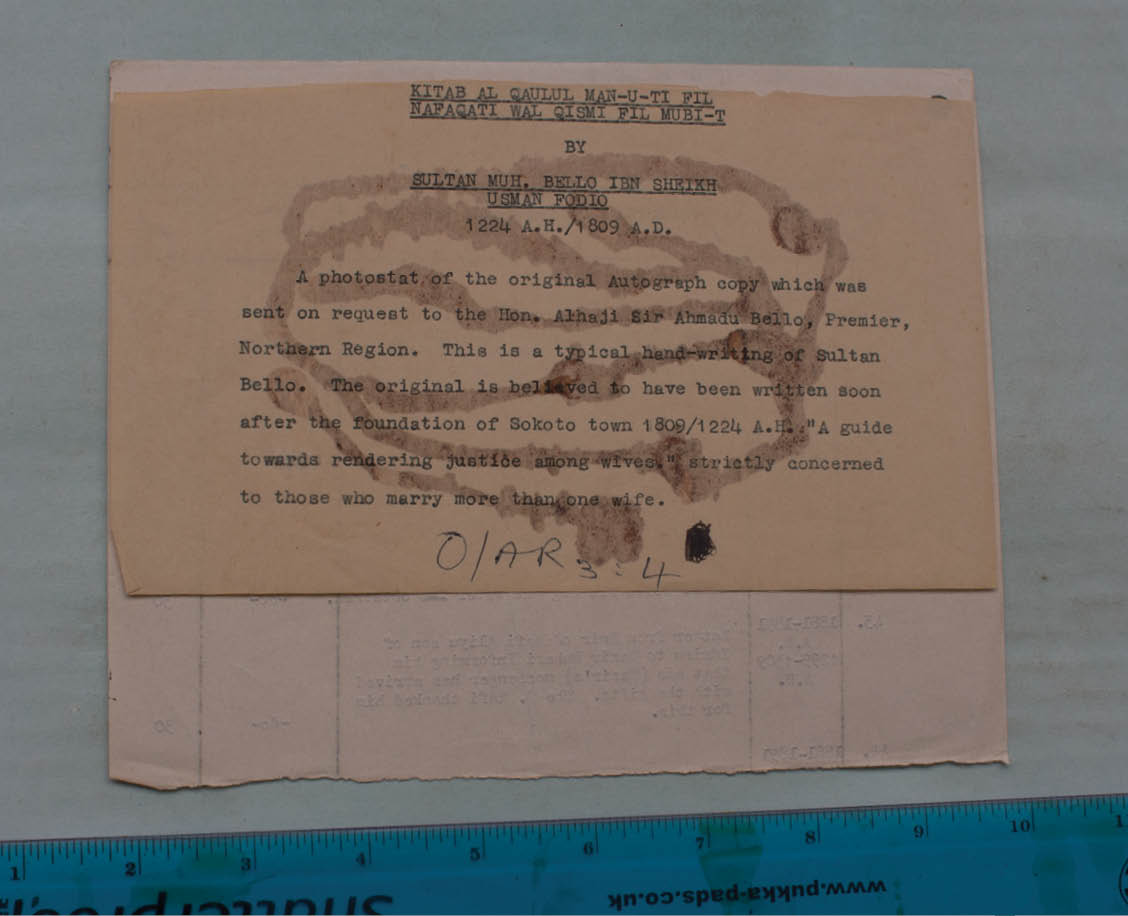

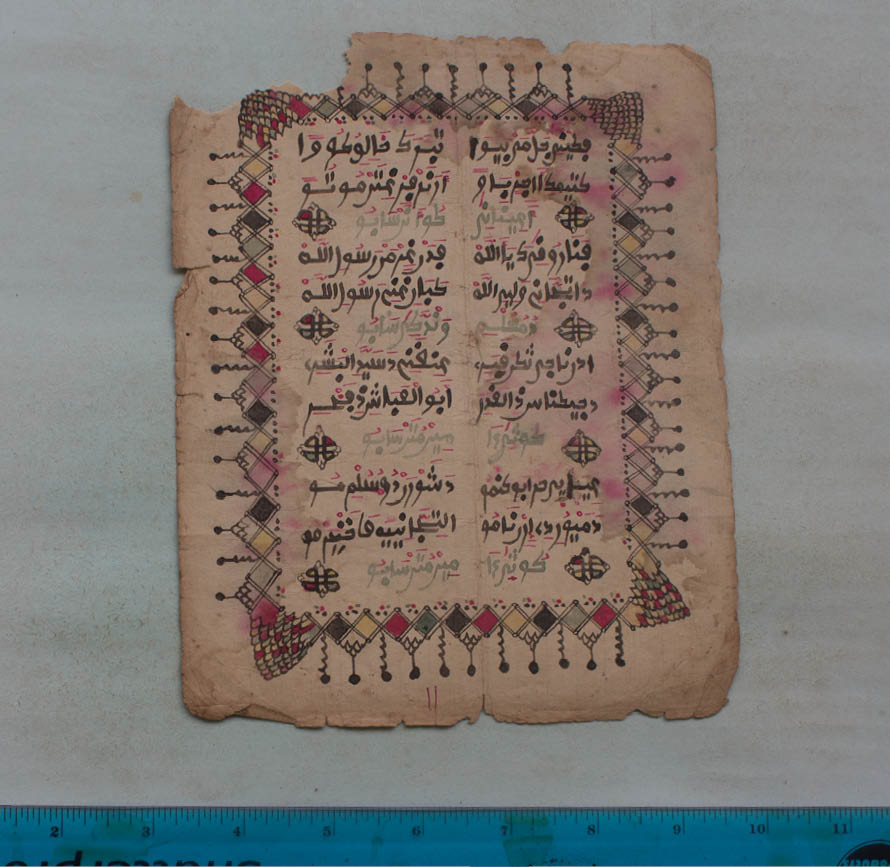

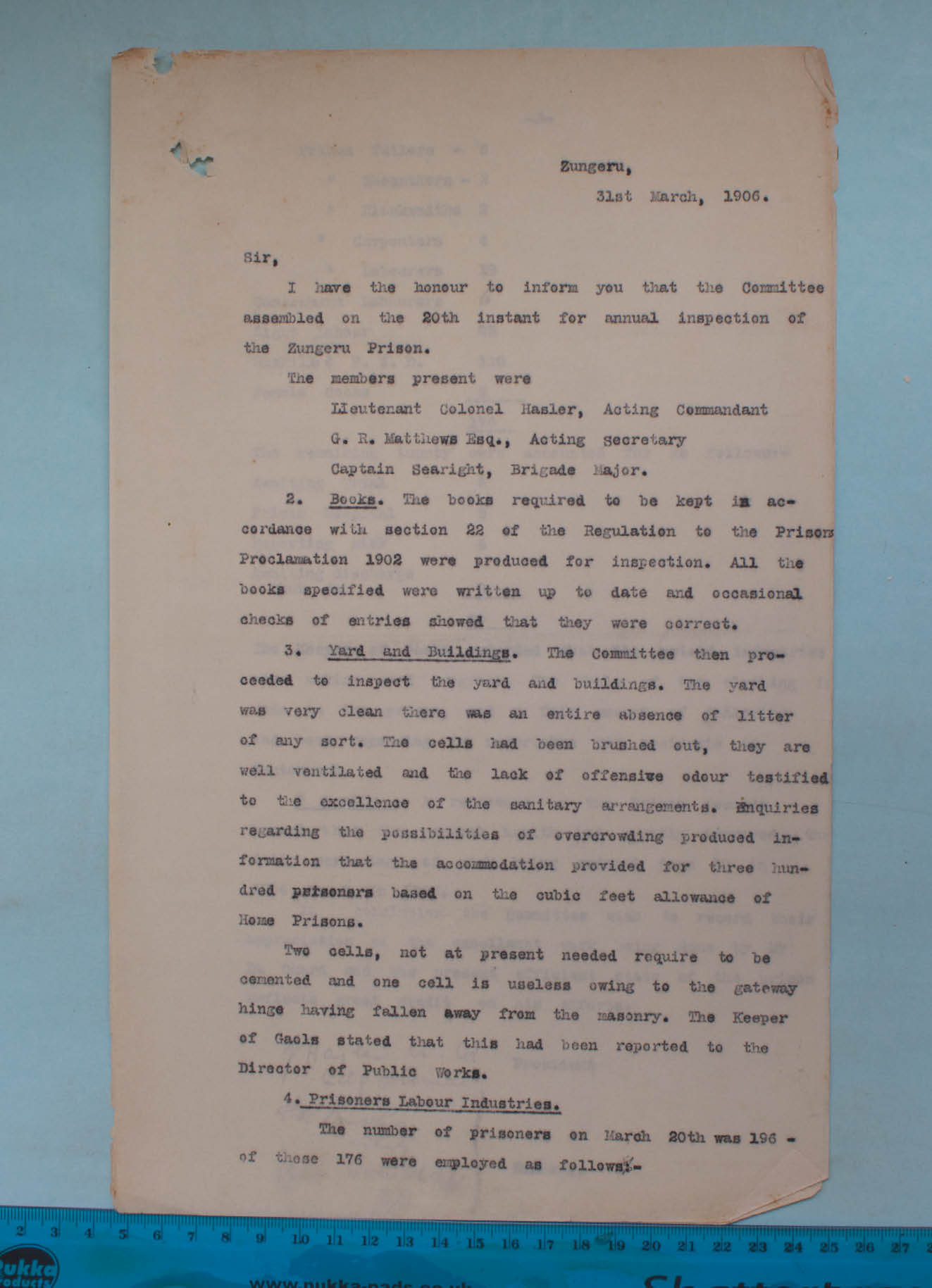

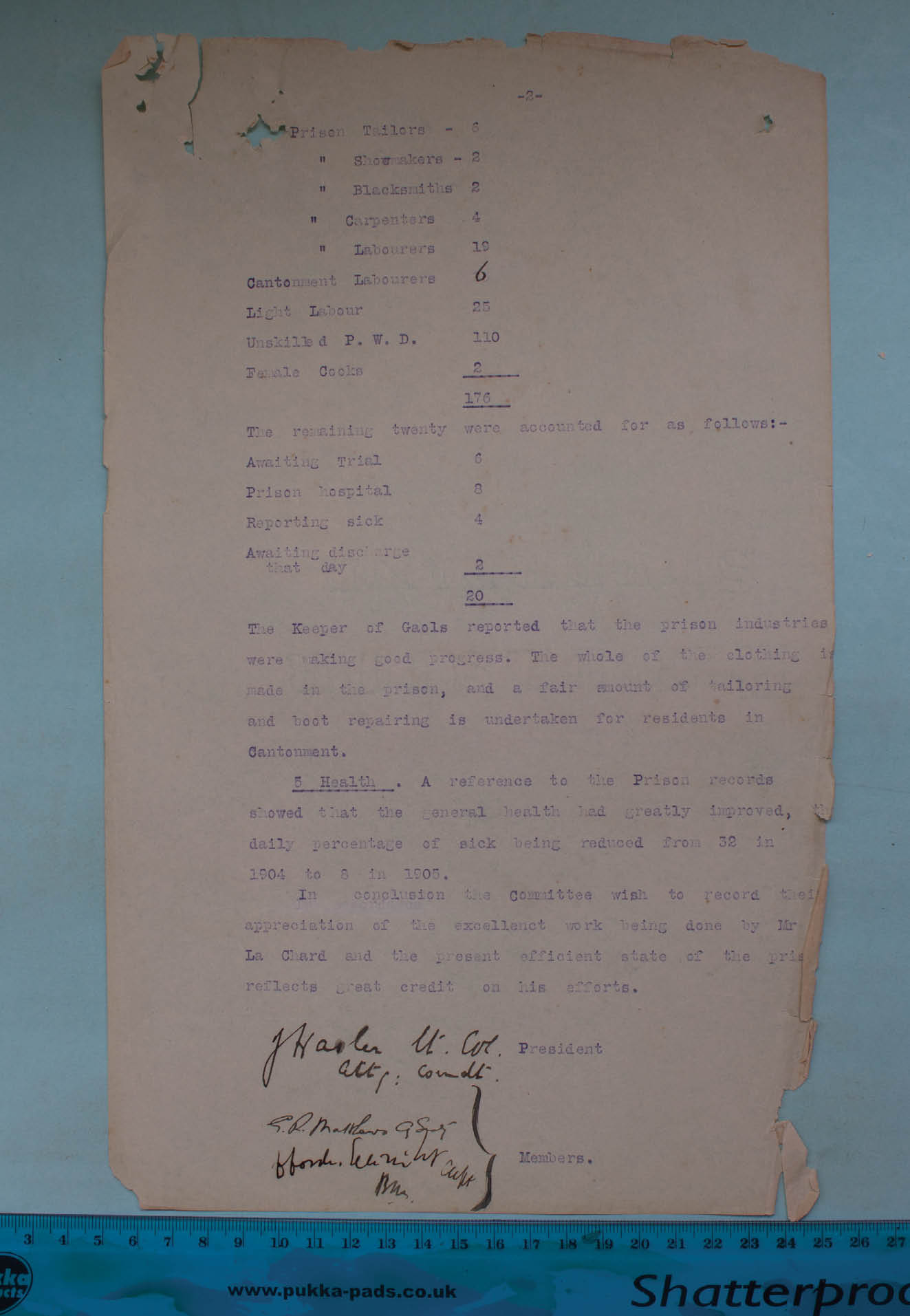

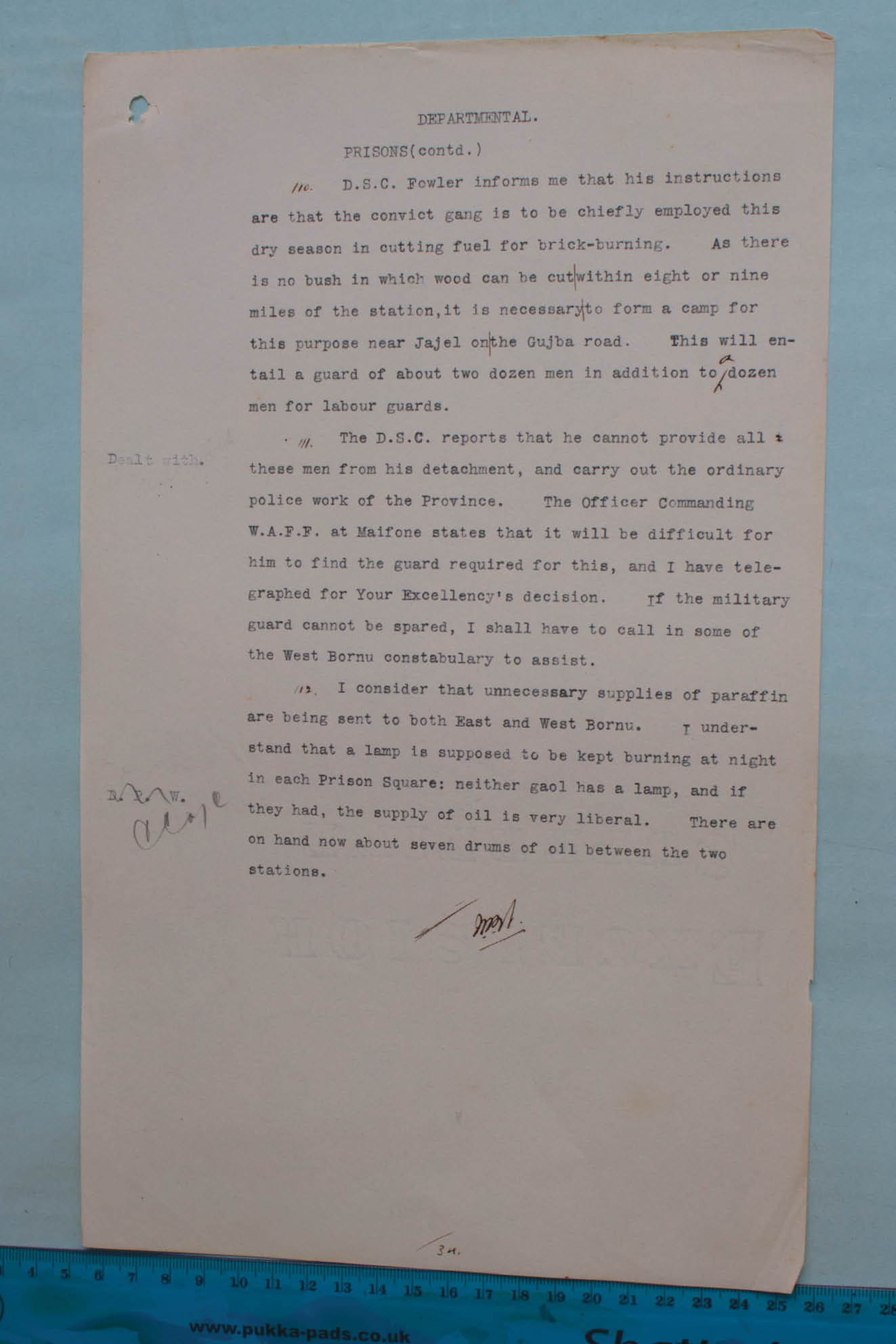

The colonial records used in writing this study were largely obtained in 2012 as part of a major digitisation project (EAP535) funded by the Endangered Archives Programme at the British Library.14 This project targeted materials stored at the National Archives of Nigeria in Kaduna and written during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Hausa, Arabic and English. It succeeded in creating an updated catalogue of materials that focus on the pre-colonial and early colonial history of Northern Nigeria (see Figs. 10.1-10.4 for examples of targeted materials). This catalogue contains 2,376 items dealing with such diverse topics as colonial policies, slavery, religion, forced labour, convict labour, pawning, agriculture and culture.15 The research team turned all of the physical paper items associated with this catalogue into 62,177 digital files. We have also deposited copies of all the digitised materials at the National Archives of Nigeria and at the British Library.16

The research team did not digitise all of the colonial records available in the National Archives or even all of the materials related to the various series mentioned below. The project leader and the relevant officials of the National Archives jointly selected materials for digitisation. Two major criteria for selection were the historical value of the records and the state of their physical preservation.

Fig. 10.1 Kitāb tārīkh Zazzau [A History of Zazzu or Zaria Emirate] by B. Ulama-i, 1924. Digitised handwritten Arabic document (EAP535/1/2/3/2, image 2), Public Domain.

Fig. 10.2 Digitised original file description written in English on an Arabic document by Sultan Muhammad Bello, n.d. (probably 1954-1966). The National Archives, Kaduna (EAP535/1/2/3/3, image 2), Public Domain.

Fig. 10.3 A Guide to Understanding Certain Aspects of Islam, by Sultan Muhammad Bello, 1809. The National Archives, Kaduna (EAP535/1/2/3/3, image 3), Public Domain.

Fig. 10.4 Waqar jami-yah by Sheikh Ahmadu ti-la ibn Abdullahi, n.d. (EAP535/1/2/19/20, image 2), Public Domain.

The underlying rationale of the project was to provide better access to endangered and unique materials dealing with slavery and unfree labour in Northern Nigeria. The colonial records we digitised in the course of EAP535 are classified in two distinct categories: the EAP535 Secretariat Northern Provinces Record Collection (SNP) and the EAP535 Provincial Record Collection. The first collection has been arranged into six series based on the order in which the records were originally accumulated by the National Archives:

|

The EAP535 Secretariat Northern Provinces Record Collection (SNP) |

|

|

SNP6 Series |

Official correspondence exchanged from 1904 to 1912 between the office of the British High Commissioner for the Northern Provinces and other colonial officers in various parts of Northern Nigeria. SNP6 represents the earliest record accumulation transferred from the Office of the Colonial Civil Secretary of Northern Nigeria at Kaduna to the National Archives, while the other series represent materials subsequently accumulated. |

|

SNP7 Series |

Official correspondence exchanged from 1902 to 1913 between the office of the British High Commissioner for the Northern Provinces and other colonial officers in various parts of Northern Nigeria. |

|

SNP8 Series |

Official correspondence exchanged from 1914 to 1921 between the office of the British High Commissioner for the Northern Provinces and other colonial officers in various parts of Northern Nigeria. |

|

SNP9 Series |

Official correspondence exchanged from 1921 to 1924 between the office of the British High Commissioner for the Northern Provinces and other colonial officers in various parts of Northern Nigeria. |

|

SNP10 Series |

Official correspondence exchanged from 1913 to 1921 between the office of the British High Commissioner for the Northern Provinces and other colonial officers in various parts of Northern Nigeria. |

|

SNP17 Series |

Official correspondence exchanged from 1914 to 1921 between the office of the British High Commissioner for the Northern Provinces and other colonial officers in various parts of Northern Nigeria. |

The EAP535 Provincial Record Collection has been organised into seven series by place/geographical areas:

|

The EAP535 Provincial Record Collection |

|

|

Zaria Provincial Records (Zarprof) Series |

Official correspondence exchanged from 1904 to 1938 between the office of the Resident of Zaria Province and other colonial officers in various parts of the province in question. |

|

Sokoto Provincial Records (Sokprof) Series |

Official correspondence exchanged from 1903 to 1929 between the office of the Resident of Sokoto Province and other colonial officers in various parts of the province in question. |

|

Ilorin Provincial Records (Ilorprof) series |

Official correspondence exchanged from 1912 to 1926 between the office of the Resident of Ilorin Province and other colonial officers in various parts of the province in question. |

|

Lokoja Provincial Records (Lokoprof) Series |

Official correspondence exchanged from 1917 to 1929 between the office of the Resident of Lokoja Province and other colonial officers in various parts of the province in question. |

|

Makurdi Provincial Records (Makprof) series |

Official correspondence exchanged from 1922 to 1938 between the office of the Resident of Makurdi Province and other colonial officers in various parts of the province in question. |

|

Minna Provincial Records (Minprof) Series |

Official correspondence exchanged from 1910 to 1928 between the office of the Resident of Minna Province and other colonial officers in various parts of the province in question. |

|

Official correspondence exchanged from 1913 to 1921 between the office of the Resident of Kano Province and other colonial officers in various parts of the province in question. |

|

Few of the materials in both the EAP535 collections focus primarily on convict labour. Rather, the majority are in the form of intelligence reports, district assessment and reassessment reports, letters, memoranda, provincial annual reports, provincial quarterly reports and touring reports.

The archival documents digitised in the course of EAP535 present a number of problems. For instance, most of the documents are culturally biased: none of them come from the convicts’ viewpoint. In one document, a European official commenting on the colonial police states that: “The fact is that this country does not produce men who can be trusted out of sight of European officers”.17 Implicitly, this statement characterises the local people of Northern Nigeria as incapable of the same strength of character that the policemen are assumed to possess. It reveals a conscious effort to depict Africans as inferior while portraying Europeans as members of a superior race.

The limitations of such materials notwithstanding, they constitute a valuable source of information about convict labour when analysed together. They tell us about the criminal records of convict labourers, the development of the prison institutions in which they lived, the health issues they experienced, their discipline and their work activities (see examples of colonial records that highlight such issues in Figs. 10.5-10.8). Furthermore, the materials demonstrate that colonial records focusing exclusively on the prison institution/convict labourers do indeed exist.18

Fig. 10.5 Report on the annual inspection of Zungeru prison by Lieutenant Colonel Hasler, 1906 [1] (EAP535/2/2/5/4, image 7), Public Domain.

Fig. 10.6 Report on the annual inspection of Zungeru prison by Lieutenant Colonel Hasler, 1906 [2] (EAP535/2/2/5/4, image 5), Public Domain.

Fig. 10.7 Report on Bornu Province prisons by W. P. Hewby, 1906 [1] (EAP535/2/2/5/16, image 53), Public Domain.

Fig. 10.8 Report on Bornu Province prisons by W. P. Hewby, 1906 [2] (EAP535/2/2/5/16, image 54), Public Domain.

The partially-extant archival documents digitised in the course of EAP535 tell us a great deal about prisons and convict labourers from the first decade of the twentieth century to the 1930s. This chapter will, for clarity of exposition, be predominantly based on materials written within the first two decades of the twentieth century, and it will focus on what these items tell us about the work activities of convicts.

In addition to materials digitised as part of EAP535, I have consulted another body of colonial records, Northern Nigeria Annual Reports, obtained from the Harriet Tubman Institute at York University in Toronto, Canada.19 These reports were written by the High Commissioner or Governor of Northern Nigeria and addressed to the Colonial Office in Britain. I will focus here on the annual reports from 1902 to 1913. The strengths and limitations of this group of reports are similar to those of other colonial records discussed above. To mitigate these limitations, in particular the colonial European bias, I have also consulted a number of primary and secondary sources, such as oral evidence from the Yusuf Yunusa Collection20 and published works on slavery in the Sokoto Caliphate and Northern Nigeria.

In my analysis of colonial records, I argue that there are clear connections between convict labour and cash crop production, the construction of public facilities, the cultivation of crops to meet the food needs of both European and African administrators, the cost-effectiveness of colonial administration in Northern Nigeria, and the construction of European hegemony. Before substantiating these arguments, I will discuss the history of the prison system in pre-colonial Northern Nigeria.

Convict labour in the pre-colonial Sokoto Caliphate

Prisons existed in the Sokoto Caliphate before the British conquest, but little attention has been devoted to examining pre-colonial imprisonment. Nevertheless, it is clear from extant sources that the inmates in Sokoto Caliphate prisons could be classified into three major groups: war prisoners, freeborn people imprisoned for political or other crimes, and slaves.21 Generally, most inmates could be ransomed, executed, enslaved or exchanged. Although many of those enslaved (from all three groups of prisoners) were used as domestic servants, others were sent to ribats (frontier fortresses) where they served as soldiers and/or in other roles such as plantation labourers, builders, concubines and weavers.22

There is evidence that convicts based within Sokoto Caliphate prisons (including those war prisoners who were yet to be ransomed, executed, enslaved or exchanged) often worked under close supervision on state fields “the entire day before returning to their cells”.23 Inmates, like many Sokoto Caliphate slaves, frequently experienced physical cruelty and starvation.24 Even though slave owners mostly punished their own slaves outside the prison, there is evidence that the slaves within Sokoto Caliphate prisons were often sent there by private estate owners or administrators of state holdings.25

In the Kano area, the major prison to which recalcitrant slaves were banished was Gidan Ma’ajin Watari.26 Situated less than a kilometre northeast of the Emir’s palace in Kano city, it was owned by the state and managed by the state official called Ma’ajin Watari. Masters sent defiant slaves, including those whom they did not want to sell or otherwise dispose of, to this prison for reform or, as Yusuf Yunusa puts it, “to be punished and preached to”.27 On a slave’s arrival at the prison, the master was expected to declare the specific offence the slave had committed and the type of punishment to be meted out. Thereafter, the erring slave was admitted to the facility through two doors, being severely beaten in the process.28 The conditions at Gidan Ma’ajin Watari were terrible, as an early colonial record indicates:29

A small doorway 2 ft. 6 in. by 18 in. gives access into it; the interior is divided by a thick mud wall (with a smaller hole in it) into two compartments, each 17 ft. by 7 ft. and 11 ft. high. This wall was pierced with holes at its base, through which the legs of those sentenced to death were thrust up to the thigh, and they were left to be trodden on by the mass of other prisoners till they died of thirst and starvation. The place is entirely air-tight and unventilated, except for one small doorway or rather hole in the wall through which you creep. The total space inside is 2,618 cu. ft., and at the time we took Kano [1903] 135 human beings were confined here each night, being let out during the day to cook their food, etc., in a small adjoining area. Recently as many as 200 have been interned at one time. As the superficial ground area was only 238 square feet, there was not, of course, even standing room. Victims were crushed to death every night — their corpses were hauled out each morning.30

While in prison, a slave was usually subjected to torture by fellow inmates as well as by guards.31 Masters could occasionally pay a visit to the prison to determine whether or not their slaves should be released. During such visits, the masters often presented their slaves with cowries or food, while the slaves, in turn, would plead for forgiveness. Ultimately, it was the master who decided how many days the slave would spend in the facility.32

Whether or not it was standard practice for masters in all parts of the Sokoto Caliphate to send slaves to various state prisons for reform, three facts are clear from the pre-colonial era. First, a prison system existed prior to British conquest in pre-colonial Muslim Nigeria. Second, convicts were sometimes made to work on state fields. Third, for all the physical punishment of convicts, the notion of rehabilitation appears to have been part of the ethos of both the caliphal state and the caliphal slaveholders.

Convict labour under colonial rule

After the British conquest in 1897-1903, the state established new prisons and maintained some old ones.33 The vast majority of the current prisons in Northern Nigeria, such as the Kano central prison and the Kazaure central prison, were built during the colonial era.34 The colonial government saw to it that agriculture emerged as the most important economic activity. This was due to several factors, of which the most prominent were: the growing demand for raw materials like cotton, rubber, groundnuts, palm oil and palm kernel by British industries; the need to make Britain independent of America for its raw cotton; and the need to generate revenue for the administration of the protectorate/colony.35 Given that colonial economic activities were mainly directed towards satisfying these needs, it is not surprising that the focus of agricultural production was on cash crop cultivation.36 The state and European firms provided seeds and employed other strategies to encourage owners of small farms to produce mainly groundnuts and cotton.37 Slave labour on plantations was instrumental to the expansion of groundnut production, as evidenced by the contribution of the royal estate in Fanisau to its development in Kano.38

In addition to encouraging the production of cash crops on small holdings and plantations, the state initiated agricultural experimental centres in prisons so as to help determine whether specific regions in Northern Nigeria were suitable for growing specific cash crops. These centres were often located on prison “farmlands,” which were also responsible for the production of food.39 The prison farmlands varied in size, but in general they occupied public land or land owned by the government, rather than land rented, purchased or borrowed.40 Because of that, the prison farmlands did not face significant obstacles in terms of land use. Consequently, colonial prison administrators could increase the acreage under cultivation at any point and locate farmlands either “on the ground in the immediate vicinity of gaol[s]” or elsewhere.41 In one report, it was proposed to move a farmland to an area relatively distant from the prison because “The ground in the immediate vicinity of the gaol is not suitable for farming purposes, the ground being very stony, and the crops were not successful”.42

The evidence discovered among the documents we digitised suggests that, unlike the use of convict labourers for food production, their use in cash crop production was not practised in all the prison farmlands that existed in early colonial Northern Nigeria. Specifically, it suggests that the use of these labourers in cash crop production was limited to several areas in Northern Nigeria including Zungeru, Lokoja, Niger Province, Kabba Province and Nassarawa Province. In these areas, convicts cultivated cash crops that were important both in Europe and also locally. Thus, in Nassarawa Province, convicts cultivated soya beans as well as the Nyasaland and Ilushi types of cotton; in Niger Province, convicts cultivated cotton; in Kabba, convicts cultivated cotton and soya beans; in Zungeru, convicts cultivated ceara rubber and sisal hemp; and in Lokoja, convicts cultivated cocoa and kola.43 Outside the actual cultivation of cash crops by convicts in these regions, there is evidence that the Director of Agriculture advocated the experiment of growing wattle in Zaria Province in 1913, although we do not know whether or not this experiment was conducted.44

Although data on the quantity of cash crops produced by convicts are lacking for almost all the regions mentioned above, we do have documents indicating that ten acres of cotton were cultivated in Nassarawa in 1911 and that 150 lbs of cotton were picked in Niger Province in 1911 (Fig. 10.6).45

Given this available data, and the fact that convicts represented a small percentage of the colonial workforce, one can assume that the cash crops produced by convicts were generally of little quantitative importance.46 On the other hand, the experimental cash crop cultivation on prison farmlands, whether successful or unsuccessful, helped to determine whether the soil and climate of specific regions were suitable for the cultivation of specific cash crops.47 Accordingly, this experimental cultivation must have been one of the factors that helped to foster the expansion of cash crop production in early colonial Northern Nigeria.

The work done by the prisoners employed in farming was considered “light” in comparison to the work prisoners did elsewhere.48 Although farm work was ideally meant only for convicts certified as medically unfit for hard labour, there is evidence that convicts employed for “hard” or non-agricultural work were sometimes also employed for farming.49 The working day could start from 6am-12pm and finish between 2pm-5.15pm, six days per week.50 Sometimes non-convicts assisted convicts in work on prison farmlands. In Niger Province in 1911, for instance, “Two acres of land were planted on July 4th with cotton and on December 13th the first picking was done by some of the Resident’s staff. All the labour other than the actual picking, was carried out by prisoners”.51

Fig. 10.9 Document from the Niger Province annual report

on cotton production for 1911 by Major W. Hamilton Browne, 1912

(EAP535/2/2/11/18, image 58), Public Domain.

Although this is not spelled out, the evidence suggests that convicts relied on the use of traditional implements and technologies (Fig. 10.9). According to one report, cash crop production, and farming in general, was often “undertaken in a really strenuous manner”; moreover, at least in Nassarawa Province before May 1911, the amount of food “originally provided was quite inadequate for men working as hard as they do”.52 This is not to say that colonial administrators regularly starved the convicts. Indeed, some colonial administrators viewed the productive activities of convicts as important. Consequently they believed that prisoners should be fed at least the minimum amount and quality of food necessary to maintain their productivity. For example, on noting that the “contract agreement”53 system was responsible for the inadequate amount of food supplied to convicts in Nassarawa Province before his tenure as the Resident of Nassarawa Province in May 1911, Major Larymore discontinued this system. Instead he instituted a prisoner’s food committee consisting of “one clerk, one Political Agent, and the sergeant of police” who eventually saw to it that convicts received “rather more than twice what they did before, under a contract agreement”.54 Overall, cash crop production, whether or not prisoners received an inadequate amount of food in the course of their activity, was less beneficial to the convicts than the food crops they produced, and the emphasis on cash crop production resulted in convicts being forced into strenuous labour.55

Convict labour in colonial public works

The colonial administrators saw an effective transport system as an indispensable accessory to the task of subordinating the economy of Northern Nigeria and making it serve the needs of Europe. Soon after gaining control, the British began the construction of roads and railroads not only to connect various parts of Northern Nigeria to each other, but also to connect Northern Nigeria in general to Southern Nigeria and its Atlantic ports.56 This infrastructure made it possible to move cash crops easily and relatively inexpensively to the various ports located along the Nigerian Atlantic coast. It also enabled the colonial government to move troops and other resources easily to various parts of Northern Nigeria in order to reinforce its control over the peoples of this region. Finally, a good transport system meant that imports from Europe, such as European fruits, vegetables and manufactured goods, could be distributed within Northern Nigeria at a relatively fast pace and at relatively low prices.57

In colonial Northern Nigeria, as in the Southern Provinces of Nigeria, the Public Works Department (PWD) was responsible for the construction and maintenance of roads and railroads. Since its inception, this department was also charged with “the maintenance of public buildings and roads and the extension of electric lighting, telegraphs, piers, public transport, among other things”.58 To carry out its diverse responsibilities, the PWD relied partly on wage labour. Because of labour shortages and the desire to lower the cost of work, the Department was also compelled to resort to the forced labour of slaves and convicts.59

Colonial administrators recorded an example of the use of convict labourers by the PWD in Yola Province in 1906.60 In that year, a foreman in charge of related government projects could not find local labour to hire. Moreover, he was unable to check the flight of non-convicts who were conscripted into forced labour. To address these challenges, the foreman suggested they import fresh batches of labour. It was in part this foreman’s request for more labourers and in part the recognition that convicts were a cost-effective labour pool, while imported labour “would add greatly to the cost of work”, that caused convict labourers to be employed in the execution of the PWD project in Yola Province.61 It is equally important to stress that, according to one telegraph, once convict labourers were placed at the disposal of the PWD, the “necessity to import labour” no longer existed.62

The work performed by prisoners employed on projects supervised by the PWD was generally described as hard labour.63 Convicts involved in hard-labour activities were often certified as being medically fit for the work they did. They were also, in the vast majority, men. Indeed, in line with the late-Victorian attitude that women should take care of domestic responsibilities, the documents declared that “Female convicts are exclusively employed in domestic duties — drawing water, preparing the prison food &c”.64

The hard labour done by convicts included “road and railway earthwork construction”,65 in addition to “ordinary labour connected with the prison”.66 This “ordinary labour” probably included improving sanitation by clearing bushes around government establishments; planting of hedges and trees; and constructing, extending and maintaining prison facilities and other public buildings. Most of these activities, such as watering shrubs and carrying bricks, stones and sand for public buildings or works, could be undertaken by unskilled labourers. Some, such as brickmaking, roofing, woodworking, finish-plastering, flooring and the like, required skilled or semi-skilled workers.67 Colonial officials usually described convicts employed on skilled labour activities as “more intelligent”.68

To ensure that skilled convict labourers were always available for use on colonial projects, many inmates “who showed any aptitude” were trained in the skills mentioned above, while others were taught “other useful trades and employed as tailors”, shoemakers, mat-makers, rope-makers, weavers and hoe-makers, among other things.69 While the training of skilled workers may have been meant to help rehabilitate the convicts,70 the products of this skilled workforce undoubtedly had commercial value that benefitted the prison.71 Although convicts engaged in manufacturing mainly worked for the benefit of the institution, one colonial report indicates that they could take private commissions from clients. In particular, it reveals that “among other works this gang was lately able to repair an ordinary English snaffle, and the broken dashboard of a four-wheeled Buckboard American trap belonging to Capt Seccombe”.72

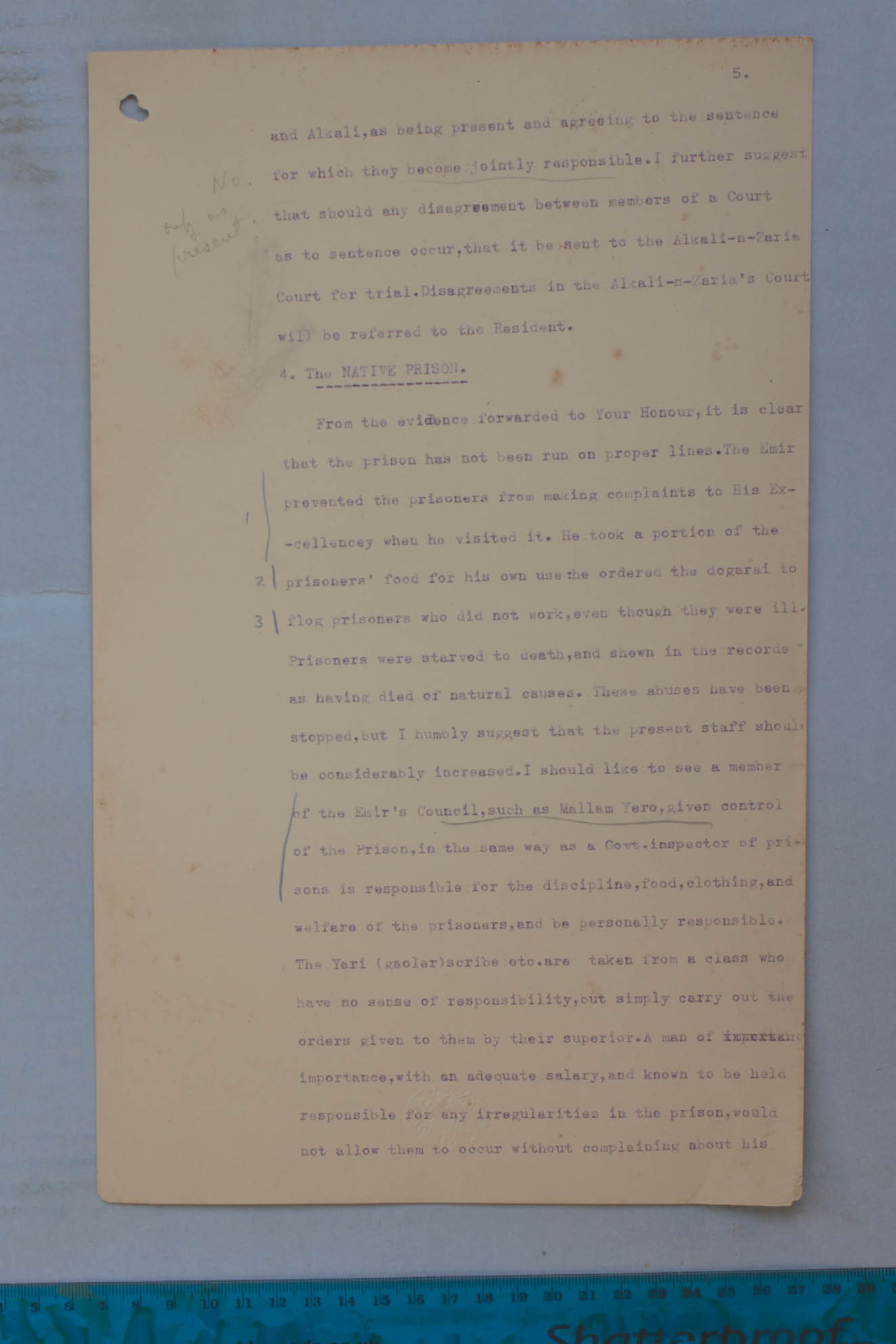

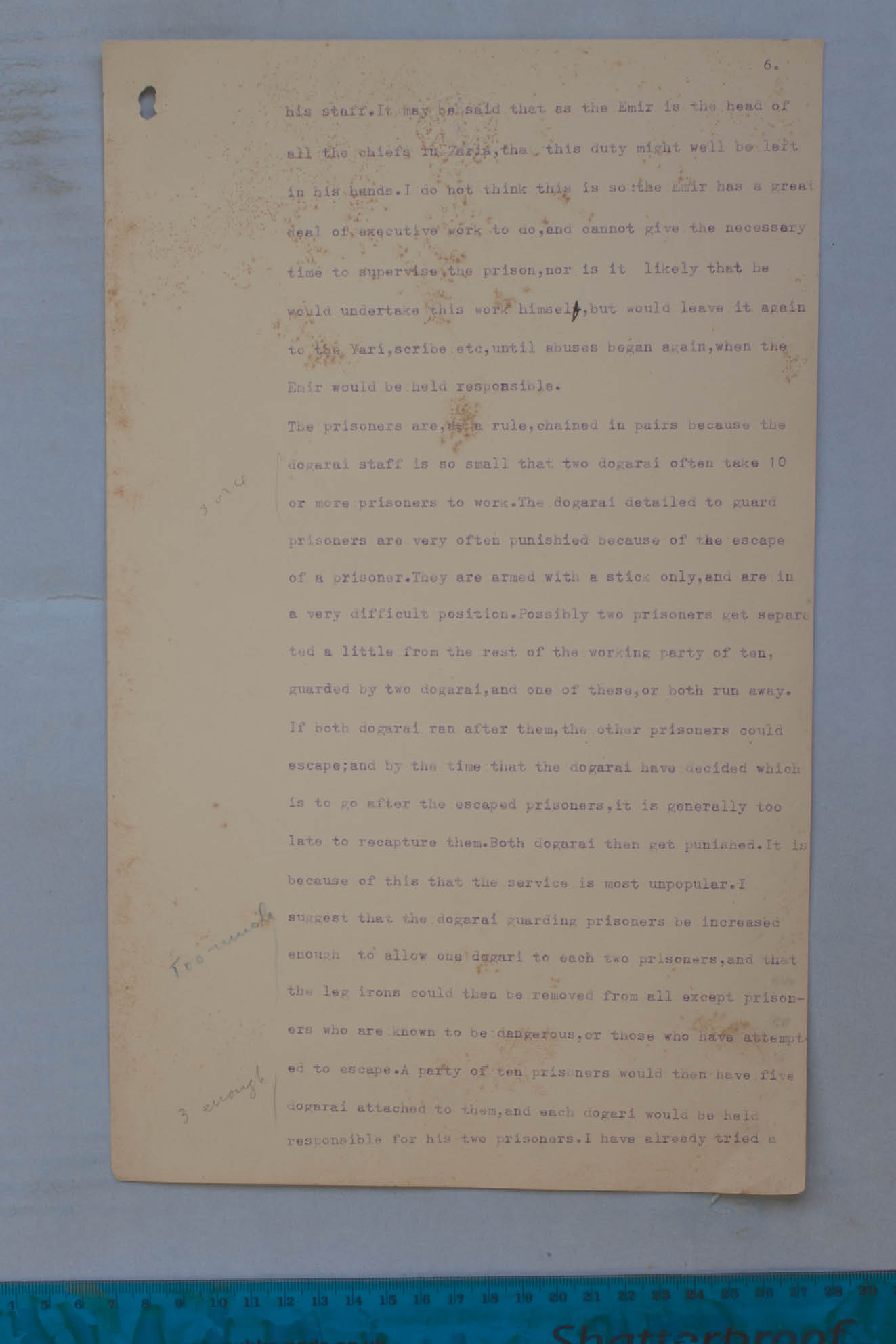

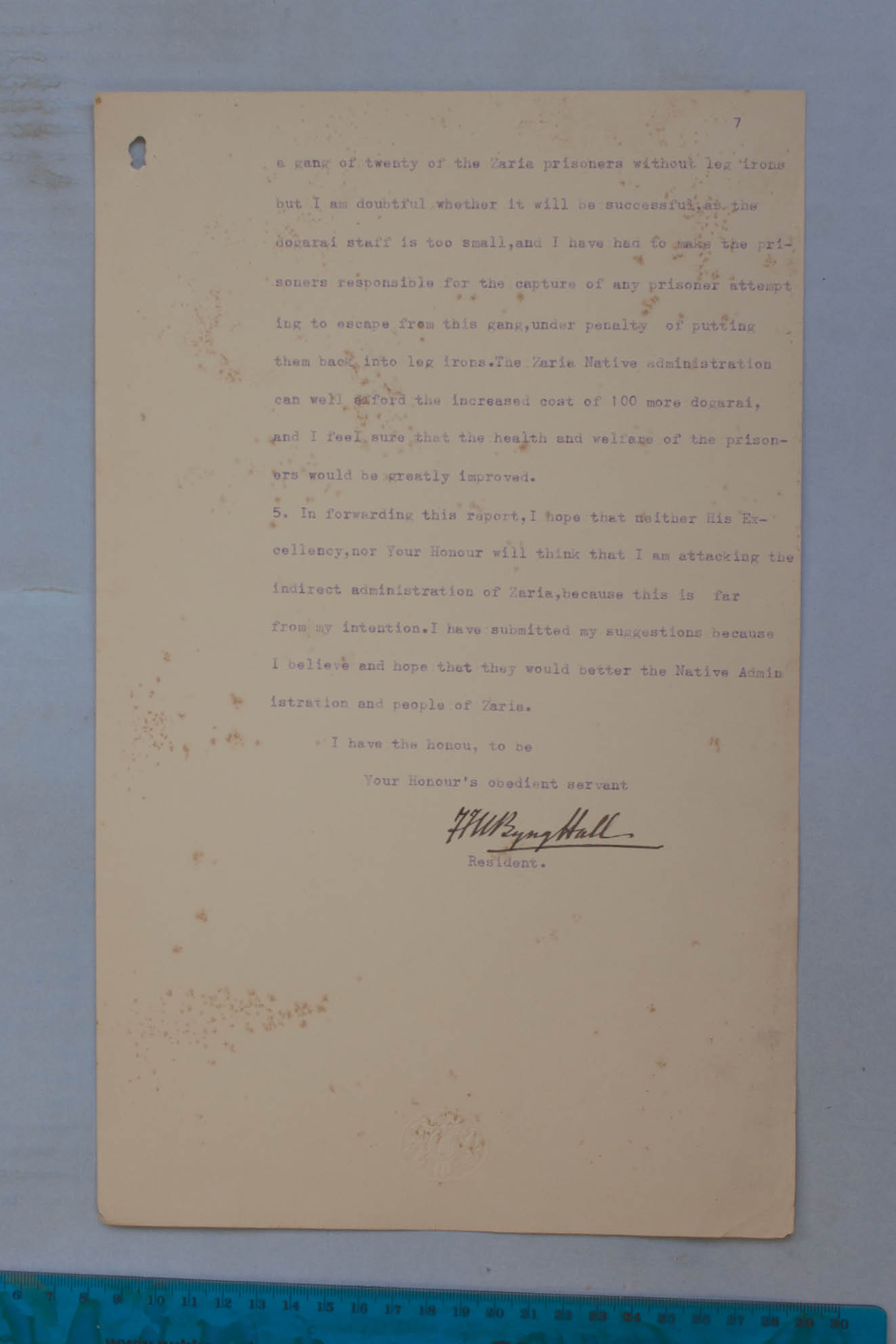

Convicts employed on projects supervised by the PWD were often divided into gangs. Thus, for instance, while one gang could be employed on station work and improvement, watering shrubs and trees, another gang could be employed in the construction of a road, and yet another gang could be used to carry materials for building operations.73 Each gang was usually escorted, guarded and supervised by security officials such as police officers, dogarai74 and armed warders.75 The archival sources do not indicate whether skilled or more experienced and hardworking convicts were given supervisory roles subordinate to those of security officials. Similarly, we have very little information about the treatment of convict workers employed on the PWD’s projects. Nevertheless, one document clearly indicates that the dogarai in the Zaria Emirate were ordered to flog prisoners who did not work, even though they were ill (Fig. 10.10).76 This same document also reveals that prisoners were often chained in pairs while working, and that they “were starved to death, and shown in the records as having died of natural causes”.77

Fig. 10.10 Report on the unsatisfactory conduct of the Maaji of Zaria by the District Officer in charge of the Zaria Emirate, Y. Kirkpatrick, to the Resident of Zaria Province, 1921 [1] (EAP535/2/3/6/18, image 20), Public Domain.

Fig. 10.11 Report on the unsatisfactory conduct of the Maaji of Zaria by the District Officer in charge of the Zaria Emirate, Y. Kirkpatrick, to the Resident of Zaria Province, 1921 [2] (EAP535/2/3/6/18, image 21), Public Domain.

Fig. 10.12 Report on the unsatisfactory conduct of the Maaji of Zaria by the District Officer in charge of the Zaria Emirate, Y. Kirkpatrick, to the Resident of Zaria Province, 1921 [3] (EAP535/2/3/6/18, image 22), Public Domain.

Like the colonial document on Zaria discussed above (Figs. 10.10-10.12), Michael Mason’s exploration of the use of forced labour in railway construction also demonstrates that convict labourers employed by the PWD often experienced physical cruelty.78

In colonial Northern Nigeria, convict labourers of diverse cultural backgrounds were often accommodated in the same prison, and the prisons themselves were often located in settlements consisting of African immigrants and non-African, mainly European residents. Each of these diverse groups wanted to maintain their own food consumption habits, which required the cultivation of specific crops. It seems that one of the reasons the state allowed some of the prison farmlands in virtually all parts of Northern Nigeria to be used as centres for the cultivation of varieties of food, fruits and vegetable crops was to meet the culinary needs of people from diverse African and European backgrounds.79 Allowing such use of some of the prison farmlands helped to address the increasing food demand of convicts in many prisons. It also lowered the cost of the prisoners’ maintenance and improved the nutritional content of their diet.80 Crops cultivated in prison farmlands in early colonial Northern Nigeria included yams, potatoes, beans, Indian peas, guinea corn, soya beans, cassava, “tropical fruits and English vegetables”.81 In determining what crop should be grown in each prison farmland, colonial officials sometimes based their suggestions, and probably decisions, on the results of experiments in their private gardens, as the following excerpt suggests:

Potato farms on a fairly large scale should certainly be tried this year. The results in my private garden were thoroughly successful. The produce of one case resulted in three months’ sufficiency or nearly three cases. I should imagine that the prison earnings from this source would be considerable (Fig. 10.9).82

Fruit and vegetable crop production in these prison farmlands had further advantages. It involved little or no capital investment by the state and it was not related to technological improvements in agricultural techniques. The production of the crops in prison was also a great boon to local Europeans, and to many Africans, because it significantly lowered food prices. The additional revenue generated for the prisons allowed them to pay for the provision of other food items to convicts, such as palm oil, fish and salt, or for any other necessary maintenance expenses.

Many prison farms planted with edible crops yielded good results, at least during specific agricultural seasons.83 Nevertheless, prison-farm production of crops — whether fruits and vegetables or cash crops — was not without problems. Their production was not cost-free, at least to the convicts; for most of them, the cultivation and care of such crops involved strenuous or “unpleasant” forced labour.84 Other issues included poor seeds and related planting materials, an inadequate workforce at times when prison labour was moved to other public works, an inadequate supply of water, poor soil conditions, poor supervision by colonial officials, natural disasters and poor farming skills.85 The colonial administrators recognised that these problems put constraints on the agricultural yields and that poor harvests, in turn, made the cost of feeding the prisoners higher than it should be. In one report, for instance, Lugard noted that:

There has been a general increase in the expenditure on prisoners’ food during the year, particularly at Bornu, Bassa, Kano and Kabba, which is ascribed to indifferent harvests. The maximum rate of 2d. per prisoner per day was exceeded in Bassa and Kabba for a portion of the year. The daily average cost per prisoner during the year was 1s. 5d.86

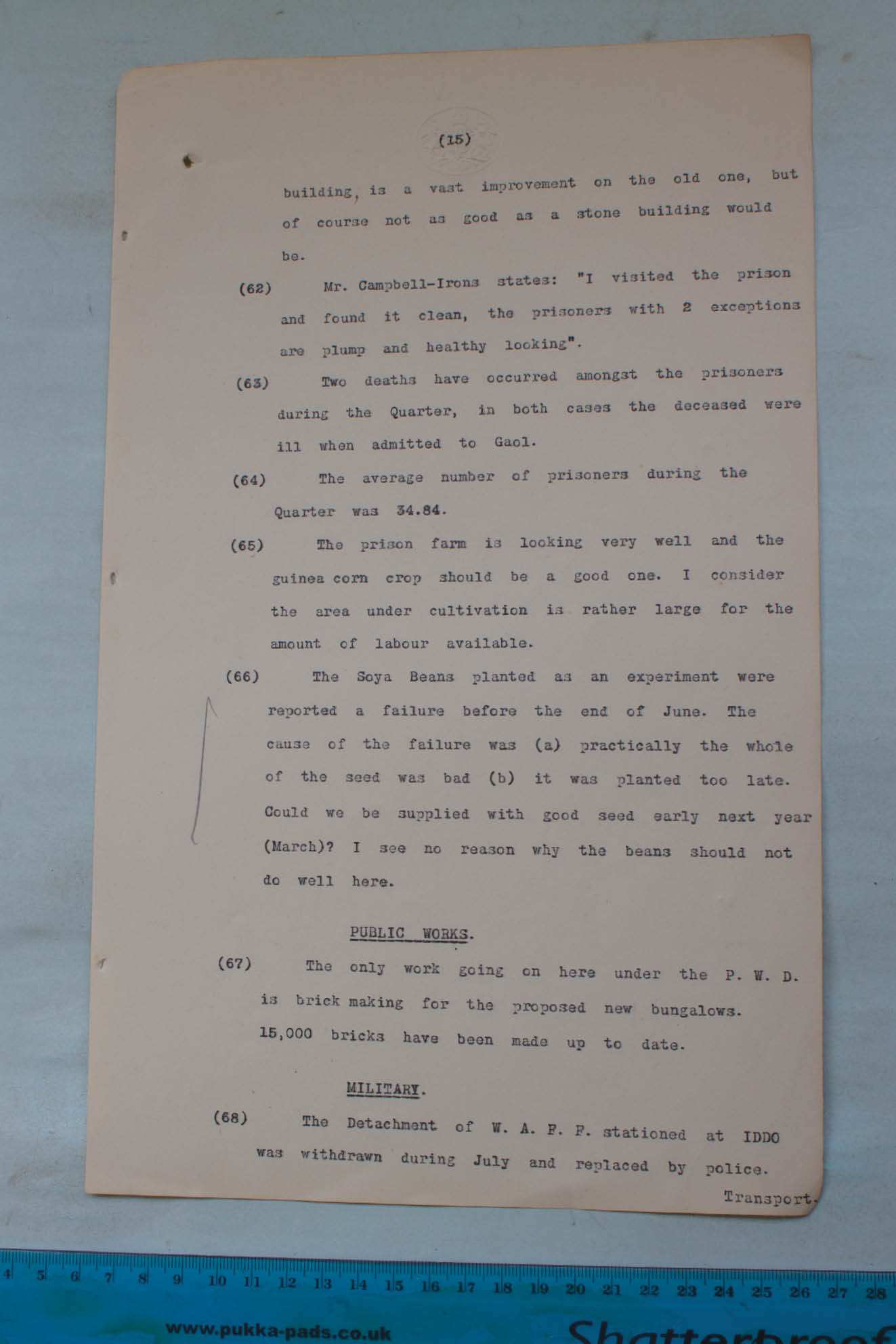

Colonial administrators often took proactive measures to deal with or to alleviate the constraints on the cultivation of all types of crops. For instance, in one case the Resident of Kabba Province, J. A. Ley Greeves, linked the failure of soya bean cultivation in 1911 to bad seeds and the fact that they were planted too late. He then called for the early supply of good seeds in the subsequent farming season. Evidently, he saw “no reason why the beans should not do well” in his province (Fig. 10.13).87

Fig. 10.13 Document from “Report September quarter 1911-Kabba Province” concerning constraints on crop cultivation by J. A. Ley Greeves, 1912 (EAP535/2/2/10/32, image 21), Public Domain.

Similarly, another colonial administrator recognised that good supervision by his subordinates was essential to successful harvests and revealed his strategy for preventing poor supervision thus:

On my return from leave I informed the Makum of Agaei who is in charge of the prison that the prison farm should be promptly cultivated and that after the harvest no further payments would be made from the Beit-al-mal, that the prison should be self supporting, and if it were not, the deficit would be made up by the Makum personally as an insufficient crop would be due to his failure to supervise.88

Cost and cost-efficiency

The British did not overlook the concept of “cost-efficiency” in making decisions of any kind in their administration of Northern Nigeria. They administered a system of indirect rule which allowed them to control the vast region with very few European officials, very little reliance on funds generated in Britain and minimal out-of-pocket costs.89 The British also made the prisons pay for themselves by using of convicts as labourers and by manufacturing and farming food within the prisons.90 The evidence also indicates that colonial administrators sometimes hired out convicts to Europeans and Africans, at a nominal charge, to do various tasks, including farming and carrying water. One 1913 report on Muri Province reveals that hiring out convicts enabled the state to cut the cost of feeding prisoners since “the employer provides their food and pays 1d. per man per day wages”.91 The same report indicates that this payment was considered small, and that this matter of inadequate pay “should be brought up for discussion with the Emir and council”, so that raising payments to 2d in the next farming season might be considered.92 For comparison, a report on Zaria Province written in the same year (1913) shows that non-convict labourers earned a daily wage of 4d.93

Several reports by colonial administrators reveal that significant cost savings were achieved through the use of convict labour. In 1907, for instance, one administrator reported that “All prison clothing has been made on the premises. In the Provinces the prisoners have been principally employed on farm work, conservancy, and making and repairing roads. […] In Zungeru and Lokoja the prison farms supply sufficient food for the maintenance of the prisoners”.94 Similarly, in 1910, he reported:

Substantial stone workshops, built entirely by prison labour, have been erected in Zungeru. The gaol at Lokoja was considerably enlarged during the year by the addition of a new wing. A considerable saving to the general revenue on this account has been effected, and it is proposed to further extend the system of employing convict labour on such work.95

As a cost-saving measure, the British trained convicts in various trades within prisons. As previously mentioned, prison administrators mainly promoted the training of convicts whom they considered “more intelligent” in tailoring, shoe making, brick-making, mat-making and the like. The emphasis on such training often fostered the production of more goods and therefore helped to swell the revenue of the Prison Department.96 The sale of items produced by convicts allowed the prisons to raise funds to hire non-convict instructors and purchase training/production materials.97

The colonial administrators were not shy about arguing for the use of convict labour to maintain public facilities in order to keep costs low. For instance, the governor of Northern Nigeria noted that in 1911 the state made significant cost savings in part because of the use of convicts in public works. He added that:

The value (calculated at two-thirds of the market rate) of prisoners’ labour in connection with public works, &c., which would otherwise have had to be paid for in cash, was £3,878. If calculated at the ordinary market rates the value of the prisoners’ useful labour would have exceeded the entire cost of the Prison Department.98

Conclusion: convict labour and European hegemony

Several works on labour history have focused intensively on the relationship between the use of convict labour and the expansion of European hegemony. Examining the transportation of convicts by European powers to various parts of the world, Clare Anderson and Hamish Maxwell-Stewart argue that although the character of convict transportation changed over time, the cost-efficiency of convict labour in colonies explains why it became a “durable and flexible” tool that shaped the expansion of European hegemony worldwide from 1415 to 1954.99 The connection between cheap convict labour and the economic success of colonies is explored in detail by William H. Worger, in the contexts of Birmingham, Alabama and Kimberley, South Africa,100 and by Florence Bernault in a broader African context.101

The documents investigated for the purpose of this chapter corroborate these conclusions. Britain’s main interest in Northern Nigeria during the colonial era was to make the region an economic appendage of Britain and Europe. To secure this interest, the British initiated infrastructure projects and encouraged agricultural production using cheap convict labour. The availability of such low-cost labour, and the resulting decrease of the cost of infrastructure and agricultural projects, made it possible for the colonial administration to increase the scale of such undertakings. Consequently, the availability of convict labour strengthened European hegemony.

Some of the documents examined for this article show that a prison system existed in the Sokoto Caliphate and that inmates within this prison system were employed in productive activities. Although the Sokoto Caliphate prisons were places of punishment, my analysis suggests that slave owners in the caliphal state sometimes employed the rhetoric of reform or rehabilitation to justify the imprisonment of many individuals. Overall, however, the findings of this project support the claim of existing scholarship that “permanent places for holding convicted prisoners or suspects before trial” in centralised states in West Africa, like the Sokoto Caliphate, “did not seek to rehabilitate criminals”.102 Evidence shows that, during the colonial era, convicts worked both within and outside the prisons; there was a direct link between their labour and the specific needs of the colonial state. In this, the colonial prison system in Africa was significantly different from the prison systems of western societies.103

References

Anderson, Clare, and Hamish Maxwell-Stewart, “Convict Labour and the Western Empires, 1415-1954”, in The Routledge History of Western Empires, ed. by Robert Aldrich and Kirsten McKenzie (London: Routledge, 2013), pp. 102-17.

Bah, Thierno, “Captivity and Incarceration in Nineteenth-Century West Africa”, in A History of Prison and Confinement in Africa, ed. by Florence Bernault (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2003), pp. 69-77.

Bashir, Tanimu, “Nigeria Convicts and Prison Rehabilitation Ideals”, Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 12/3 (2010), 140-52.

Bernault, Florence, “The Shadow of Rule: Colonial Power and Modern Punishment in Africa”, in Cultures of Confinement: A History of the Prison in Africa, Asia and Latin America, ed. by Frank Diköter and Ian Brown (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2007), pp. 55-95.

Christelow, Alan, “Slavery in Kano, 1913-1914: Evidence from the Judicial Records”, African Economic History, 14 (1985), 57-74.

Clapperton, Hugh, Journal of Second Expedition into the Interior of Africa from the Bight of Benin to Socaccatoo (London: Frank Cass, 1829).

Cook, Allen, Akin to Slavery: Prison Labour in South Africa (London: International Defence and Aid Fund, 1982).

Dirk, Kohnert, “The Transformation of Rural Labour Systems in Colonial and Post-Colonial Northern Nigeria”, Journal of Peasant Studies, 13/4 (1986), 258-71.

Elias, T. O., ed., The Prisons System in Nigeria: Papers (Lagos: Lagos University Press, 1968).

Falola, Toyin, and Matthew M. Heaton, A History of Nigeria (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

Frimpong, Kwame, “Botswana and Ghana”, in Prison Labour: Salvation or Slavery?: International Perspectives, ed. by Dirk van Zyl Smit and Frieder Dünkel (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1999), pp. 25-36.

Heaton, Matthew M., Black Skin, White Coats: Nigerian Psychiatrists, Decolonization, and the Globalization of Psychiatry (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2013).

Heussler, Robert, The British in Northern Nigeria (London: Oxford University Press, 1968).

Hill, Polly, “From Farm Slavery to Freedom: The Case of Farm Slavery in Nigerian Hausaland”, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 18 (1976), 395-426.

Hogendorn, Jan S., Nigerian Groundnut Exports: Origins and Early Development (London: Oxford University Press, 1979).

—, and Paul E. Lovejoy, “The Reform of Slavery in Early Colonial Northern Nigeria”, in The End of Slavery in Africa, ed. by Suzanne Miers and Richard Roberts (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1988), pp. 391-411.

—, and Paul E. Lovejoy, Slow Death for Slavery: The Course of Abolition in Northern Nigeria, 1897-1936 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

Jumare, Ibrahim M., “The Late Treatment of Slavery in Sokoto: Background and Consequences of the 1936 Proclamation”, International Journal of African Historical Studies, 27/2 (1994), 303-22.

—, Land Tenure in Sokoto Sultanate of Nigeria (Ph.D. thesis, York University, Toronto, 1995).

Killingray, David, “Punishment to Fit the Crime?: Penal Policy and Practice in British Colonial Africa”, in A History of Prison and Confinement in Africa, pp. 97-118.

Lovejoy, Paul E., “Slavery in the Sokoto Caliphate”, in The Ideology of Slavery in Africa, ed. by Paul E. Lovejoy (Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 1981), pp. 200-43.

Lugard, F. D., The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa (Edinburgh: William Blackwood, 1922).

Mason, Michael, “Working on the Railway: Forced Labor in Northern Nigeria, 1907-1912”, in African Labor History, ed. by Peter C. W. Gutkind, Robin Cohen and Jean Copans (London: Sage, 1978), pp. 56-79.

Nicolson, I. F., The Administration of Nigeria, 1900-1960: Men, Methods and Myths (London: Oxford University Press, 1969).

Northern Nigeria Annual Reports 1902-1912, MS, Harriet Tubman Institute, York University, Toronto, Canada (cited as NNAR) (uncatalogued).

Okediji, F. A., An Economic History of Hausa-Fulani Empire of Northern Nigeria, 1900-1939 (Ph.D. thesis, Indiana University Bloomington, 1972).

Onimode, Bade, Imperialism and Underdevelopment in Nigeria: The Dialectics of Mass Poverty (Lagos: Macmillan, 1983).

Orr, Charles William James, The Making of Northern Nigeria, 2nd edn. (London: Cass, 1965).

Perham, Margery, Lugard: The Years of Authority 1898-1945 (London: Collins, 1960).

Salau, Mohammed Bashir, The West African Slave Plantation: A Case Study (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011).

Saleh-Hanna, Viviane, and Chukwuma Ume, “Evolution of the Penal System: Criminal Justice in Nigeria”, in Colonial Systems of Control: Criminal Justice in Nigeria, ed. by Viviane Saleh-Hanna (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 2008), pp. 55-68.

—, ed., Colonial Systems of Control: Criminal Justice in Nigeria (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 2008).

Super, Gail, “Namibia”, in Prison Labour: Salvation or Slavery?: International Perspectives, ed. by Dirk van Zyl Smit and Frieder Dünkel (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1999), pp. 153-68.

Ubah, Chinedu N., “Suppression of the Slave Trade in the Nigerian Emirates”, Journal of African History, 32 (1991), 447-70.

Van Zyl Smit, Dirk, “South Africa”, in Prison Labour: Salvation or Slavery?: International Perspectives, ed. by Dirk van Zyl Smit and Frieder Dünkel (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1999), pp. 211-40.

Worger, William H., “Convict Labour, Industrialists and the State in the US South and South Africa, 1870-1930”, Journal of Southern African Studies, 30 (2004), 63-86.

Yunusa, Yusuf, Slavery in the 19th Century Kano (Bachelor’s dissertation, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, 1976).

Documents from the National Archives of Nigeria

in Kaduna104

EAP535/3/7/2/5

Sokoto Province monthly report no. 23, February 1905.

EAP535/3/7/2/7

Sokoto Province monthly report no. 25, May and June 1905.

EAP535/2/2/5/4

Report on prisons for year ending 21 December 1905.

EAP535/2/2/5/16

Bornu Province quarterly report, September 1906.

EAP535/2/2/7/39

Kano Province twelve-year report, 30 June 1908.

EAP535/2/2/8/1

Zaria Province quarterly report, December 1908.

EAP535/2/2/10/26

Nassarawa Province quarterly report, June 1911.

EAP535/2/2/10/32

Kabba Province quarterly report, September 1911.

EAP535/2/2/10/38

Nassarawa Province quarterly report, September 1911.

EAP535/2/2/10/44

Bornu Province quarterly report, December 1911.

EAP535/2/2/11/13

Yola Province quarterly report, December 1911.

EAP535/2/2/11/18

Niger Province annual report, 1911.

EAP535/2/2/11/8

Kabba Province annual report, 1911.

EAP535/2/2/11/9

Bornu Province annual report, 1911.

EAP535/2/2/11/17

Nassarawa Province annual report, 1911.

EAP535/2/5/1/39

Quarterly report no. 80, December 1912, by Mr. F. H. Buxton Resident Muri Province.

EAP535/2/5/1/14

Kabba Province quarterly report, December 1912.

EAP535/2/5/1/46

Muri Province annual report, 1912.

EAP535/2/5/1/81

Zaria Province quarterly report, March 1913.

EAP535/3/6/5/4

Niger Province annual report no. 6, 1913.

EAP535/3/8/2/12

Zaria Province annual report no. 62, 1913.

EAP535/3/2/2

Kano Province annual report, 1917.

EAP535/2/2/9/1

Sanitation labourers for Katsina Allah.

EAP535/2/2/4/20

Difficulty of obtaining labourers at Yola.

EAP535/2/3/6/18

Report of unsatisfactory conduct of Maaji of Zaria.

EAP535/2/3/6/9

Flogging in gaols for prison offences: amendment of regulations.

1 The research for this article was funded by the Endangered Archives Programme and the College of Liberal Arts award from the University of Mississippi. I would like to thank the editor and anonymous reviewers of this volume for their comments and support.

2 See for instance Jan S. Hogendorn and Paul E. Lovejoy, “The Reform of Slavery in Early Colonial Northern Nigeria”, in The End of Slavery in Africa, ed. by Suzanne Miers and Richard Roberts (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1988), pp. 391-411.

3 Chinedu N. Ubah, “Suppression of the Slave Trade in the Nigerian Emirates”, Journal of African History, 32 (1991), 447-70.

4 Alan Christelow, “Slavery in Kano, 1913-1914: Evidence from the Judicial Records”, African Economic History, 14 (1985), 57-74. Related to Christelow’s work on the Kano region is Polly Hill, “From Farm Slavery to Freedom: The Case of Farm Slavery in Nigerian Hausaland”, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 18 (1976), 395-426.

5 Ibrahim M. Jumare, “The Late Treatment of Slavery in Sokoto: Background and Consequences of the 1936 Proclamation”, International Journal of African Historical Studies, 27/2 (1994), 303-22.

6 Michael Mason, “Working on the Railway: Forced Labor in Northern Nigeria, 1907-1912”, in African Labor History, ed. by Peter C. W. Gutkind, Robin Cohen and Jean Copans (London: Sage, 1978), pp. 56-79.

7 See, for instance, Kohnert Dirk, “The Transformation of Rural Labour Systems in Colonial and Post-Colonial Northern Nigeria”, Journal of Peasant Studies, 13/4 (1986), 258-71.

8 Examples of works that focus comprehensively or less comprehensively on the prison system in Nigeria include Viviane Saleh-Hanna, ed., Colonial Systems of Control: Criminal Justice in Nigeria (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 2008); Tanimu Bashir, “Nigeria Convicts and Prison Rehabilitation Ideals”, Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 12/3 (2010), 140-52; and T. O. Elias, ed., The Prisons System in Nigeria: Papers (Lagos: Lagos University Press, 1968).

9 Mohammed Bashir Salau, The West African Slave Plantation: A Case Study (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 124-25.

10 See for instance Kwame Frimpong, “Botswana and Ghana”; Gail Super, “Namibia”; and Dirk Van Zyl Smit, “South Africa”, in Prison Labour: Salvation or Slavery?: International Perspectives, ed. by Dirk van Zyl Smit and Frieder Dünkel (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1999), pp. 25-36, pp. 153-68 and pp. 211-40 respectively.

11 Allen Cook, Akin to Slavery: Prison Labour in South Africa (London: International Defence and Aid Fund, 1982), p. 3.

12 For more details on Lugard see, for instance, I. F. Nicolson, The Administration of Nigeria, 1900-1960: Men, Methods and Myths (London: Oxford University Press, 1969); and Margery Perham, Lugard: The Years of Authority 1898-1945 (London: Collins, 1960).

13 Examples of works on European administrators and their activities in Northern Nigeria include Robert Heussler, The British in Northern Nigeria (London: Oxford University Press, 1968); and Charles William James Orr, The Making of Northern Nigeria, 2nd edn. (London: Cass, 1965).

14 EAP535: Northern Nigeria: Precolonial documents preservation scheme - major project, http://eap.bl.uk/database/overview_project.a4d?projID=EAP535

15 The British Library has published the catalogue online at: http://searcharchives.bl.uk/primo_library/libweb/action/search.do?dscnt=1&scp.scps=scope%3A%28BL%29&frbg

=&tab=local&dstmp=1413822282462&srt=author&ct=search&mode=Basic&dum=true&

indx=1&vl%28freeText0%29=EAP535*&fn=search&vid=IAMS_VU2&fromLogin=true&

fromLogin=true

17 EAP535/3/7/2/7: Sokoto Province, monthly report no. 25, May and June 1905.

18 While investigating documents in the National Archives of Nigeria in Kaduna, I discovered that the Prison Department in colonial Northern Nigeria maintained monthly and annual reports. Also, many records in the Public Works Department (PWD), as well as other SNP and provincial files dealing with the late colonial era, contain references to the use of convict labourers. Unfortunately, mainly due to the limited duration of the project, the research team could not digitise all materials related to the use of convict labour during the colonial era.

19 The Harriet Tubman Institute probably obtained these materials from the British Library, although such colonial records could be found in other archives based elsewhere.

20 The Yusuf Yunusa Collection consists of interviews recorded on cassette tapes in 1975. The tapes have been deposited at the Northern History Research Scheme of Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, and at the Harriet Tubman Institute, York University, Toronto. They are also available on CDs or in digital format at the Tubman Institute.

21 Salau, pp. 83-84; Northern Nigeria Annual Report (henceforth cited as NNAR) 1902, p. 29; Thierno Bah, “Captivity and Incarceration in Nineteenth-Century West Africa”, in A History of Prison and Confinement in Africa, ed. by Florence Bernault (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2003), pp. 69-77 (p. 74); and David Killingray, “Punishment to Fit the Crime?: Penal Policy and Practice in British Colonial Africa”, in Prison and Confinement in Africa, pp. 97-118 (p. 100).

22 For further details on how slaves were used to foster Hausa-Fulani or Muslim hegemony in the Sokoto Caliphate see, for instance, Salau, pp. 45-54.

23 Bah, p. 74.

24 F. D. Lugard, The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa (Edinburgh: William Blackwood, 1922), p. 199; and Bah, p. 74.

25 Ibrahim Jumare, Land Tenure in Sokoto Sultanate of Nigeria (Ph.D. thesis, York University, Toronto, 1995), p. 193; and Hugh Clapperton, Journal of Second Expedition into the Interior of Africa from the Bight of Benin to Socaccatoo (London: Frank Cass, 1829), p. 210.

26 Salau, p. 83; Yusuf Yunusa, Slavery in the 19th Century Kano (Bachelor’s dissertation, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, 1976), pp. 23-24; and Paul E. Lovejoy, “Slavery in the Sokoto Caliphate”, in The Ideology of Slavery in Africa, ed. by Paul E. Lovejoy (Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 1981), pp. 200-43 (p. 232). See also the Yunusa Collection at the Harriet Tubman Institute, York University, particularly the testimonies of Muhammadu Sarkin Yaki Dogari (aged 70 when interviewed at Kurawa ward, Kano city, 28 September 1975), Malam Muhammadu (aged 75 when interviewed at Bakin Zuwo, Kano Emirate, 9 October 1975), and Sallaman Kano (aged 55 when interviewed at the Emir’s palace, 20 September 1975). Sallaman Kano was resident at the palace and responsible for the royal holdings at Giwaram and Gogel.

27 Yunusa, “Slavery in the 19th Century”, p, 23.

28 Salau, p. 83; and Yunusa, “Slavery in the 19th Century”, pp. 23-24.

29 Northern Nigerian Annual Report 1902, p. 29, as quoted in Lugard, p. 99 n. For a similar description of the deplorable conditions of prisons in the Sokoto Caliphate, see Jumare, Land Tenure, p. 193; and Clapperton, p. 210.

30 Lugard, p. 199.

31 Salau, p. 84; and Yunusa, “Slavery in the 19th Century”, pp. 23-24.

32 Ibid., pp. 23-24. See also the Yunusa Collection, particularly the testimonies of Muhammadu Sarki Yaki Dogari and Sallaman Kano.

33 On the maintenance of old prisons, see NNAR 1902, p. 76; and on the construction of new prisons, see Viviane Saleh-Hanna and Chukwuma Ume, “Evolution of the Penal System: Criminal Justice in Nigeria”, in Colonial Systems of Control: Criminal Justice in Nigeria, ed. by Viviane Saleh-Hanna (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 2008), pp. 55-68.

34 For further details on the growth of the prison system in Nigeria, including Northern Nigeria, see ibid., pp. 55-68.

35 NNAR 1904, p. 61.

36 For references to the predominance of cash crops in Nigerian agriculture of the time see, for instance, Jan S. Hogendorn, Nigerian Groundnut Exports: Origins and Early Development (London: Oxford University Press, 1979); F. A. Okediji, An Economic History of Hausa-Fulani Empire of Northern Nigeria, 1900-1939 (Ph.D. thesis, Indiana University Bloomington, 1972); and Bade Onimode, Imperialism and Underdevelopment in Nigeria: The Dialectics of Mass Poverty (Lagos: Macmillan, 1983).

37 For further details on such incentives see, for instance, Hogendorn, Nigerian Groundnut Exports, pp. 16-35 and 58-76.

38 For further details on steps taken to enhance groundnut production in colonial Northern Nigeria see, for instance, Salau, pp. 122-25; and Hogendorn, Nigerian Groundnut Exports, pp. 58-76.

39 NNAR 1912, p. 10; EAP535/2/2/10/26: Nassarawa Province quarterly report, June 1911; EAP535/2/2/11/18: Niger Province annual report, 1911.

40 For an excellent discussion of colonial land policies in early colonial Northern Nigeria and the problems of land use faced by slaves in particular, see Jan S. Hogendorn and Paul E. Lovejoy, Slow Death for Slavery: The Course of Abolition in Northern Nigeria, 1897-1936 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

41 EAP535/2/2/11/18.

42 Ibid.

43 NNAR 1912, p. 18; EAP535/2/2/10/26; EAP535/2/2/11/18; EAP535/2/2/11/8: Kabba Province annual report, 1911.

44 EAP535/2/5/1/81: Zaria Province quarterly report, March 1913.

45 EAP535/2/2/10/26; and EAP535/2/2/11/18, p. 33.

46 It is difficult to determine the precise scale of production of cash crops in Northern Nigeria. However, according to Hogendorn, little more than 50,000 to 100,000 bales of cotton were already grown in the Kano-Zaria region alone by 1907 (Nigerian Groundnut Exports, p. 29). Given that a bale of cotton generally weighs about 500 pounds, it is logical to say that the cash crops produced by convicts were generally of little quantitative importance.

47 NNAR 1912, p. 18.

48 NNAR 1908-09, p. 12.

49 EAP535/2/2/10/26.

50 Ibid.

51 EAP535/2/2/11/18.

52 EAP535/2/2/10/26.

53 Ibid. It is important to stress that this source seems to suggest that prisons depended on local contractors/merchants for part of their food supplies under the “contract agreement” system.

54 EAP535/2/2/10/26.

55 Ibid.

56 Mason, p. 57.

57 See, for instance, ibid.; Hogendorn, Nigerian Groundnut Exports, pp. 16-35; and Northen Nigeria Annual Report 1902, p. 58.

58 Toyin Falola and Matthew M. Heaton, A History of Nigeria (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008), p. 116; and Matthew M. Heaton, Black Skin, White Coats: Nigerian Psychiatrists, Decolonization, and the Globalization of Psychiatry (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2013), p. 32.

59 For details on land policies and other factors that compelled slaves to take part in infrastructural works in early colonial Northern Nigeria, see Hogendorn and Lovejoy, Slow Death for Slavery, pp. 136-58.

60 EAP535/2/2/4/20: Difficulty of obtaining labourers at Yola.

61 Ibid.

62 Ibid.

63 NNAR 1908, p. 31. For a similar classification, see EAP535/2/2/5/4: Report on prisons for year ending 21 December 1905.

64 NNAR 1907-08, p. 31. For a similar entry see, for instance, EAP535/2/2/5/4.

65 NNAR 1908, p. 12; and NNAR 1909, p. 15.

66 NNAR 1908, p. 31.

67 NNAR 1907-08, p. 31; and NNAR 1909, p. 15.

68 See, for instance, EAP535/2/2/11/9: Bornu Province annual report, 1911.

69 NNAR 1903, p. 25.

70 For examples of the use of reform rhetoric by colonial officials see, for instance, NNAR 1906-07, p. 41; and EAP535/2/2/10/38: Nassarawa Province quarterly report, September 1911.

71 Inferred from ibid.

72 EAP535/2/2/10/44: Bornu Province quarterly report, December 1911.

73 Ibid. For further references to the division of convicts into gangs for such productive activities see, for instance, EAP535/2/2/5/16: Bornu Province quarterly report, September 1906; EAP535/2/2/7/39: Kano Province twelve-year report, 30 June 1908; EAP535/2/2/9/1: Sanitation labourers for Katsina Allah; and EAP535/3/7/2/5: Sokoto Province monthly report no. 23, February 1905.

74 Dogarai refers to native administration police, some of whom served as each Emir’s guards and messengers.

75 For references on the use of the three category of guards see, for instance, NNAR 1903, p. 23; NNAR 1904, p. 117; NNAR 1908, p. 12; NNAR 1909, p. 14; and EAP535/3/2/2: Kano Province annual report, 1917.

76 EAP535/2/3/6/18: Report of unsatisfactory conduct of Maaji of Zaria. The main report in this file was written by the District Officer in charge of the Zaria Emirate, Y. Kirkpatrick, to the Resident of Zaria Province. This report deals with the conduct of the Maaji, a senior Native Administration official who was responsible for the Emirate’s treasury. Although it focuses mainly on various transactions mostly in connection with the collection of taxes in Zaria Province, it also points to malpractice in the prison system. In addition to issues related to the treatment of prisoners mentioned above, the report provides useful information on convict resistance and on the colonial prison system in Northern Nigeria in general.

77 EAP535/2/3/6/18. For more details on the flogging of prisoners see, for instance, EAP535/2/3/6/9: Flogging in gaols for prison offences: amendment of regulations.

78 Here, forced labourers refer to non-convicts who were conscripted into forced labour. See Mason.

79 NNAR 1912, p. 18.

80 NNAR 1906-07, p. 41; and NNAR 1912, p. 18. For discussion related to the issue of proper nutrition for prisoners, see p. 15.

81 See, among others, NNAR 1906-07, p. 41; EAP535/2/2/11/18; EAP535/2/2/11/8; EAP535/3/6/5/4: Niger Province annual report no. 6, 1913; EAP535/2/2/8/1: Zaria Province quarterly report, December 1908.

82 EAP535/2/2/11/18.

83 For references to successful farmlands see, for instance, EAP535/2/5/1/14: Kabba Province quarterly report, December 1912; and EAP535/3/6/5/4.

84 EAP535/3/7/2/5 and EAP535/2/2/10/26. It is notable that the former also reveals that convicts were often forced to labour in mosquito breeding swamps.

85 NNAR 1913, p. 12; EAP535/2/2/10/26; EAP535/2/2/11/8; EAP535/2/5/1/81; EAP535/3/6/5/4.

86 NNAR 1913, p. 12.

87 EAP535/2/2/10/32: Kabba Province quarterly report, September 1911.

88 EAP535/3/6/5/4; and EAP535/3/8/2/12: Zaria Province annual report no. 62, 1913 also indicates that poor supervision resulted in a specific farm failure in Zaria Province in 1913.

89 See Heussler, The British in Northern Nigeria, especially pp. 31 and 53.

90 This idea is expressed in, for instance, EAP535/3/6/5/4.

91 EAP535/2/5/1/39: Quarterly report no. 80, December 1912, by Mr. F. H. Buxton. On the hiring out of convicts, see also EAP535/2/2/11/13: Yola Province quarterly report, December 1911; EAP535/2/5/1/46: Muri Province annual report, 1912; and EAP535/3/7/2/7.

92 EAP535/2/5/1/39.

93 EAP535/2/5/1/81: Zaria Province report-March quarter 1913.

94 NNAR 1907-08, p. 31; and NNAR 1909, p. 15.

95 NNAR 1910-11, p. 21.

96 Inferred from EAP535/2/2/11/17: Nassarawa Province annual report, 1911.

97 EAP535/2/2/11/9.

98 NNAR 1906-07, p. 41.

99 Clare Anderson and Hamish Maxwell-Stewart, “Convict Labour and the Western Empires, 1415-1954”, in The Routledge History of Western Empires, ed. by Robert Aldrich and Kirsten McKenzie (London: Routledge, 2013), pp. 102-17 (p. 113).

100 William H. Worger, “Convict Labour, Industrialists and the State in the US South and South Africa, 1870-1930”, Journal of Southern African Studies, 30 (2004), 63-86.

101 Florence Bernault, “The Shadow of Rule: Colonial Power and Modern Punishment in Africa”, in Cultures of Confinement: A History of the Prison in Africa, Asia and Latin America, ed. by Frank Diköter and Ian Brown (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2007), pp. 55-95.

102 Ibid., p. 57.

103 For the view that the colonial prison system in Africa was unique see, for instance, ibid., pp. 59, 71 and 77-79.