11. Murid Ajami sources of knowledge: the myth and the reality1

© Fallou Ngom, CC BY http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0052.11

It is because of divine grace that there is ethnolinguistic diversity.

Ajami, the practice of writing other languages using the modified Arabic script, is a centuries-old tradition, deeply embedded in the histories and cultures of Islamised Africa.2 With roots intertwined with those of the first Quranic schools of Africa, Ajami remains important in rural areas and religious centres where the Quranic school is the primary educational institution.3 African Ajami traditions go as far back as the sixteenth century to the early days of Islam in sub-Saharan Africa.4 They emerged as local scholars understood that they needed to write in local languages texts that could be read, recited and chanted in order to convert people. The materials that emerged represent an essential source of knowledge on the Islamisation of the Wolof, Mande, Hausa, and Fulani in West Africa and the Swahili and Amharic in East Africa, as well as a mine of information on Africa.5 In South Africa, Muslim Malay slaves produced some of the first written records of Afrikaans in Ajami.6

This contribution focuses on the Ajami tradition of the Muridiyya Sufi order founded by Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba Mbacké (1853-1927).7 The bulk of the materials discussed here is taken from those digitised with the support of the Endangered Archives Programme.8 The article addresses Ajami literacy in Africa and the factors that contributed to its flourishing among the followers of Muridiyya. It also explores the religious and secular functions of Ajami and its role in the emergence of the Murid assertive African Muslim identity that perpetually thwarts external tutelage and acculturation. Finally, it outlines the scholarly and practical benefits that could be gained from studying African Ajami systems.

Ajami literacies of Africa

While illiteracy remains a major problem in sub-Saharan Africa, the official literacy rates of local governments and UNESCO do not reflect the actual literacy rates in Muslim areas where the classical Arabic script has been modified to write local languages for centuries, just like the Latin script was modified to write numerous European languages. In many Muslim areas of Africa, Ajami literacy is more widespread than Latin script literacy, including among women in some cases.9

A limited census conducted in the areas of Labé in French-speaking Guinea reveals that over 70% of the population are literate in the local form of Ajami (including 20-25% of women);10 in Diourbel (the heartland of Muridiyya), Matam, and Podor in Senegal, about 70% are literate in Ajami, and in Hausa-speaking areas of Niger and Nigeria, over 80% of the population are Ajami literates.11 Though Marie-Ève Humery questions Cissé’s rates of literacy in Ajami, and while it is true that Ajami literacy is less developed in Fuuta Tooro,12 it is undeniable that grassroots Ajami literacy is much higher in West African Muslim communities in general than Latin-script literacy. One need not look any further than in the business records of local shopkeepers to establish the significance of Ajami in West African Muslim communities.13

The misrepresentation of Ajami users in official statistics is due to the fact that “literacy” is generally construed for sub-Saharan Africans as the ability to read and write in Arabic or European languages or the ability to read and write African languages using the Latin script. This narrow and prevailing understanding of literacy has perpetuated the prevalent myth of sub-Saharan Africa as a region with no written traditions. This understanding of literacy espoused by African governments and international organisations has excluded the millions of people who regularly use Ajami.14 The rich African Ajami materials refute the pervasive myth of the holistic illiteracy of Africa that is perpetuated by the over-emphasis on African oral traditions in academia.15 This emphasis has resulted in the omission of Africa’s unique sources of knowledge in Ajami in various domains of knowledge production about the continent.

As David Diringer has rightly noted, scripts generally follow religions.16 Just like the Latin script spread throughout the world through Christianity and was modified to write numerous European languages, so too the Arabic script spread through Islam and was modified to write numerous African languages. Many African Ajami traditions initially emerged as part of the pedagogies to disseminate Islam to the illiterate masses.17 However, their usage expanded to encompass other areas of knowledge, as for example in Figs. 11.5-11.8, 11.11, and 11.12, just as the Latin script flourished from the church environment to encompass other secular domains of knowledge of different European communities that had modified the script to meet their written communication needs.

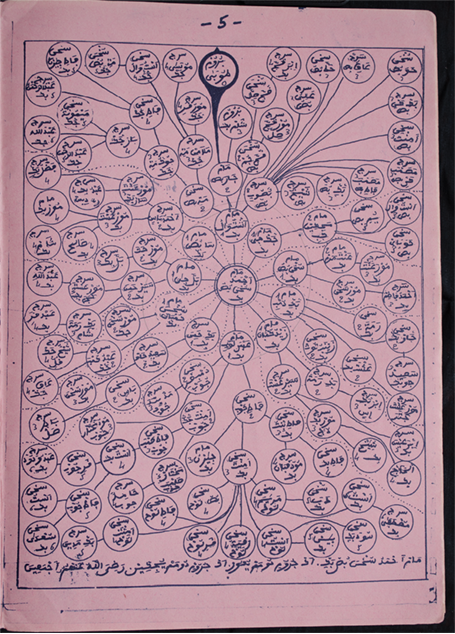

African Ajami materials uncovered to date encompass various areas of knowledge. These include prayers, talismanic protective devices, religious and didactic materials in poetry and prose, elegies, translations of works on Islamic metaphysics, jurisprudence, Sufism, and translations of the Quran from Arabic into African languages. The existing secular Ajami writings encompass commercial and administrative record-keeping, family genealogies, as for example in Fig. 11.5, records of important local events such as foundations of villages, births, deaths, weddings, biographies, political and social satires, advertisements, road signs, public announcements, speeches, personal correspondences, traditional treatment of illnesses (including medicinal plants), incantations, history, local customs and ancestral traditions, texts on diplomatic matters, behavioural codes, and grammar.18

African Ajami traditions are varied and old. The oldest material in Wolofal (the local name of Wolof in Ajami script), I found is a bilingual French-Wolof Ajami diplomatic document dating to the early nineteenth century. The document is a treaty negotiation between King Louis XVIII of France and King of Bar of the Gambia of 1817. The negotiation was about a trading post that the King of France desired in Albreda on the northern bank of the River Gambia. The scribes of the two kings wrote down the words of their respective rulers in their separate “diplomatic languages and scripts”. The resulting French and Ajami texts are juxtaposed in the document.19

The juxtaposition of the French and Ajami texts in the document reflects the balance of power between the two kings at that time. The document indicates that European rulers recognised local Ajami literacies and their significance in their initial encounters with African Muslim rulers. However, as colonisation unfolded and the balance of power shifted in favour of European rulers, Ajami began to be suppressed and gradually replaced in official transactions by the Latin script, and the myth of the holistic illiteracy of Africans began to be cultivated to legitimise the colonial “civilising mission”.20

Many of the first official transactions signed between Europeans and African Muslim rulers in their initial encounters (when they treated each other as peers) contain traces of Ajami. The King Bomba Mina Lahai of Malagea of Sierra Leone “signed in Ajami” two treaties with the French in May and August of 1854 to allow them to travel and trade in the Melacori River.21 Additionally, in the collections of Abbé Boilat, a letter dated 1843 of the local Wolof Imam to the mayor of Saint-Louis, Senegal was written in Ajami and translated into French.22 In 1882, over 1,200 inhabitants of the four towns of Gorée, Dakar, Rufisque, and Saint-Louis in Senegal, traditionally called les quatres communes (whose inhabitants acquired French citizenship) petitioned the French government against the mandatory military service. The names of the signatories were written in Wolof Ajami.23 Additionally, the names in the collective letter written by over 25 cantonal chiefs and Wolof notables of Senegal to renew their loyalty to the French colonial government and to express their concerns in 1888 were “signed in Ajami” though the message of the letter was written in Arabic.24

Until the 1920s, the information on banknotes in Senegal included Wolof Ajami text explaining their worth. Mamadou Cissé ties the removal of Wolof Ajami writings on Senegalese banknotes to the general neglect of West African Arabic-based writings, which he attributes to the bias against Islam of colonial authorities that post-colonial leaders perpetuated. He argues that both colonial and post-colonial authorities treat Arabic-based writings as a threat to the construction of a secular and multi-ethnic state.25 Banknotes with Ajami writings also existed in Nigeria. Hausa Ajami appeared alongside English on the Nigerian currency called Naira (₦) until the new ₦ 1,000 banknote introduced in 2006, but the new ₦ 20 and ₦ 50 banknotes introduced in March 2007 bear English, Yoruba, Igbo and Hausa, all in Roman script.26 Although the change represents a shift to a national language policy known as wazobia, which is construed as a symbol of national unity, Muslims took it as anti-Islamic, while a number of prominent Christians favoured it on the basis that Arabic (for which they had mistaken the Arabic script Hausa) was a foreign language.27 The existing evidence demonstrates that Ajami was and is not exclusively used for religious purposes. When studied, African Ajami materials will illuminate various aspects of Africa’s pre-colonial, colonial and post-colonial history.

The flourishing of Ajami in Murid communities

Although many African Ajami traditions began as part of the pedagogies of teaching religious subjects in Quranic schools and learning centres, little is known about the idiosyncratic local factors that account for the flourishing or lack of flourishing of Ajami in specific Muslim communities. It is widely accepted that Ajami thrived in the Hausaland of northern Nigeria particularly because Usman ɗan Fodio (1754-1817) and his family used Ajami poetry in order to convert people to Islam and to gain their support for their Jihad effort.28 In Fuuta Jalon in Guinea, Thierno Mombeya used Ajami to spread Islam to the farmers and herders and to express his desire for cultural autonomy.29 The exceptionally close links of the Fuuta Tooro (the origin of Oumar Tall) with Arabic-speaking centres of learning in North Africa likely prevented the flourishing of Ajami tradition in Fuuta Tooro.30 But nothing significant is known about why Ajami flourished among the Murids the way it did to become the primary means of written communication and the badge of their collective identity. The factors that contributed to the flourishing of Ajami among Murids are numerous.

Muslims represent over 90% of the Senegalese population.31 They are distributed among three major Sufi orders: Qadiriyya (whose members are predominantly Moors and Mandinka and their Wolofised descendants); Tijaniyya (which includes four offshoots: the Malick Sy, the Niassène, the Layène branch whose members are predominantly Lebu (a subgroup of the Wolof), and the branch of Oumar Tall whose followers are mostly members of the Fulani subgroup called Tukulóor); and Muridiyya (whose membership was predominantly Wolof but is now increasingly mixed). Both Qadiriyya and Tijaniyya orders originated from the Maghrib and the Middle East.32 In contrast, Muridiyya is the youngest Sufi movement and the only Sufi order founded by a black man who was born and raised in sub-Saharan Africa. It is with the advent of Muridiyya that a black man (Ahmadou Bamba) had parted with Middle Eastern Sufi orders to claim the status of a founder for the first time in the history of Islam in sub-Saharan Africa.33

The Murid Ajami master poets’ lack of direct contact with the Arab world and their focus on conveying Bamba’s views and teachings to the masses in their local tongue are two significant factors that partly account for the flourishing of Ajami in Muridiyya. Though other Senegalese orders have produced Ajami materials, their production remains limited compared to that of the Murids. Most of the didactic and devotional literature of Tijaniyya and Qadiriyya orders of Senegal are written in Arabic. In contrast, besides Bamba’s classical Arabic odes, the bulk of the readily available Ajami materials in marketplaces and bookstores across Senegambia are produced by the Murids. Despite being the youngest Sufi movements of Senegambia, its Ajami production dwarfs the combined output of the other orders. This significant difference in Ajami materials among the Murids is due to the origin, history, didactic, and ideological orientation of Muridiyya as conveyed in the works of Murid Ajami scholars. 34

As shown in the previous section, grassroots Wolof Ajami literacy existed before the emergence of Ahmadou Bamba. Like their Hausa and Fulani colleagues in Hausaland and Fuuta Jalon,35 Wolof Muslim scholars were bilingual. Many produced didactic and devotional materials in Arabic and Wolof, their native tongue and the lingua franca in Senegambia.36 One of the most prominent Wolof scholars who wrote both in Arabic and Ajami is the jurist and poet Khaly Madiakhaté Kala (1835-1902) who initiated Bamba in the arts of poetry.

Khaly was a colleague of Bamba’s father, Momar Anta Saly (d. 1883). Momar and Khaly served both as Muslim judges and advisors to the last Wolof king, Lat Dior Ngoné Latyr Diop (1842-1886). As part of his pedagogy, Khaly co-authored poems with his advanced students. He often began Arabic, Ajami, or bilingual poems (Arabic and Ajami) and tasked his advanced students to complete them in order to teach them new poetic techniques and to gauge their knowledge of Islamic sciences. One such work is the popular Arabic poem “Huqqal Bukā’u? [Should they be Mourned?]” that Bamba wrote in his teenage years. Khaly had begun the poem with the following theological question: since the Quran teaches that heaven and earth did not mourn the death of the unrighteous such as the pharaoh and his followers, should the deceased saints be mourned? He asked Bamba to complete the poem in order to assess both his poetic skills and mastery of the Islamic literature on the issue. Bamba completed the poem and highlighted the reasons why deceased saints ought to be mourned.37

Similarly, in one bilingual Arabic and Ajami poem entitled in Arabic “Qāla qāḍi Madiakhaté Kala [Judge Madiakhaté Kala said]” jointly composed with Bamba before 1883, Khaly wrote the first 22 verses engaging Bamba, his then student, who responded with the sixteen remaining verses of the poem. All the verses of the poem rhyme with a Wolof structure written in Ajami, including “woppuma” [I am not ill], “ba na ma” [left me], “të na ma” [it is beyond my control], and “meruma” [I am not angry]. 38

With this educational background, Bamba recognised the importance of Ajami before he began his Sufi movement in 1883. The founding of Muridiyya accelerated Ajami literary production in Wolof society, an acceleration that continues today.39 The establishment of Muridiyya, the life story of Bamba, and his own Arabic writings are fairly well known.40 His life story as told in hagiographic Ajami sources such as Jasaawu Sakóor: Yoonu Géej gi [Reward of the Grateful: The Odyssey by Sea] written between 1927 and 1930 and Jasaawu Sakóor: Yoonu Jéeri ji [Reward of the Grateful: The Odyssey by Land] written between 1930 and 1935 by Moussa Ka, and Jaar-jaari Boroom Tuubaa [Itineraries of the Master of Tuubaa] published in 1997 by Mahmoud Niang is poignant and inspirational for Murids.41

Bamba was born and raised in Senegambia in the troubled nineteenth century, a period characterised by French colonisation and the destruction of the local traditional political and social structures. He emerged in the national scene in 1883 after the death of his father. Murid scholars regard 1883 as the birthdate of Muridiyya.42 From 1883 to his death in 1927, Bamba’s life was marked by suffering. He was wrongly accused of preparing a holy war against the French colonial administration and subsequently was exiled to Gabon for seven years (1895-1902).

Fig. 11.1 Picture of Ahmadou Bamba taken during the 2012 Màggal, the yearly celebration of his arrest in 1895. The Arabic verses read as follows: “My intention on this day is to thank You, God; O You, the only one I implore, The Lord of the Throne”.

Upon his return from his seven-year exile to Gabon, new unfounded accusations were again made against him, which led to his second exile to Mauritania (1903-1907). When he returned from Mauritania, the French administration kept him under house arrests in Thieyène (1907-1912) and in Diourbel (1912-1927) where he died. He is buried in Touba, the holy city of Muridiyya. At the end of his life, however, the French colonial administrators realised that they were mistaken and they attempted to rehabilitate him by awarding him the Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honour), the highest distinction of the French Republic.43 Though colonial sources note that Bamba received the award, Murid Ajami sources contend that he did not accept it.44

But for Bamba and his followers, the long unjust sufferings he courageously endured and the nonviolent approach he championed have profound religious meaning. They see his ordeals as analogous to the sufferings of the prophets and saints of the Abrahamic religions, so too the price he had to pay to attain supreme sainthood in order to become the saviour and the intercessor of mankind. These narratives pervade Murid Ajami and oral sources.45

Bamba stressed in his teachings the equality between all people, work ethic, Sufi education, self-reliance, and self-sufficiency. He also sought to reform the traditional Islamic book-based education to make it more practical, ethics-centred, and to accommodate the varying ethical and spiritual needs of the uneducated crowds who first joined his movement. Because he understood that Ajami is pivotal to communicate his teachings to the masses, he encouraged it and implemented a division of tasks within his movement. He gave orders to some of his senior disciples to separate from him and found their own communities as independent leaders.46 He encouraged Mor Kairé (1869-1951), Samba Diarra Mbaye (1870-1917), Mbaye Diakhaté (1875-1954), and Moussa Ka (1889-1967), the four initial Murid Ajami poets, to write in Ajami in order to spread his message to the majority of the Wolof people who could not read Arabic.47

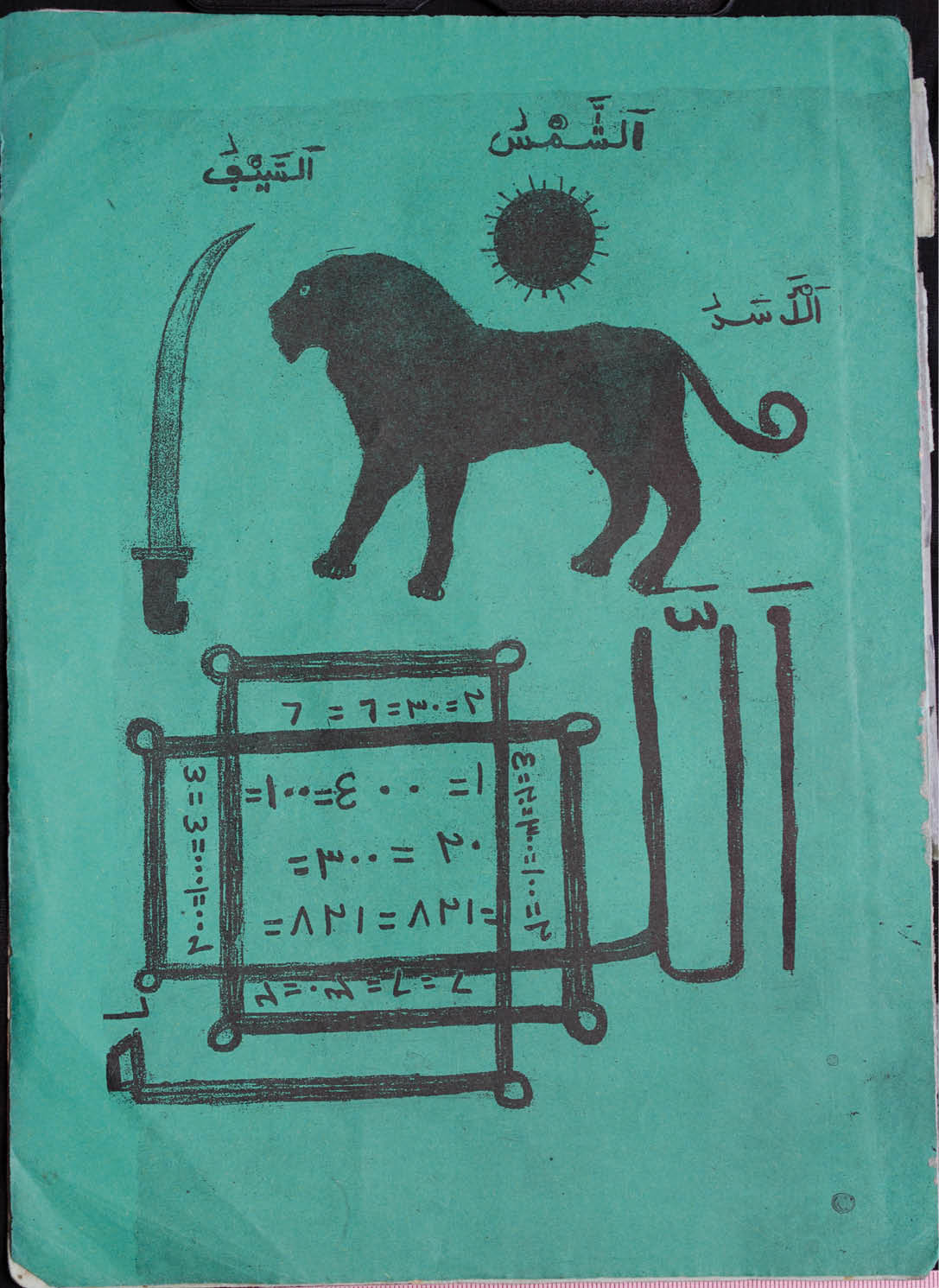

As the language of the Quran, Arabic letters (including Arabic numerals) have a holy status in African Muslim areas. They are believed to have spiritual potency and are thus regularly used in prayers, Islamic medicine, numerology, and in the making of amulets such as good luck charms and protective devices as documented in Fig. 11.3, discussed below. Arabic has also been used as the lingua franca of the elite in Muslim communities. For the illiterate masses (who cannot differentiate Ajami texts from Arabic texts) everything that looks like Arabic is regarded as potent, regardless of whether the material is religious or not. Among educated and semi-educated African Muslims, however, Ajami does not have the potency of Arabic nor its holy status.48

Ajami is used primarily for educational and communicational purposes among the Murids. Because of the “de-sacralised” status of Ajami scripts, Murid Ajami materials routinely include western numerals.49 These numerals are used for different purposes, including in the paginations of Arabic and Ajami educational materials in Murid communities. The use of western numerals in paginations in Murid communities is a post-colonial phenomenon because manuscripts written before Senegal’s independence (1960) do not use numerals for pagination. They utilise “pointers” called joxoñ in Wolof. These “pointers” consist of writing the first word of the next page at the bottom of the preceding page. They have largely been replaced by paginations with western numerals in contemporary Murid educational materials.50

In contrast, materials used in Islamic medicine, numerology, or potent prayers do not include western numerals. While the instructions to use the medicine, the numerological figure, or the prayer formulae are typically in Ajami and can include western numerals, the formulae themselves are exclusively in Arabic with Arabic numerals due to their perceived potency derived from the sacredness of the Quran.51

Related to this issue is the centrality of numeracy among Ajami users, an issue largely overlooked in the literature. Many successful business people, shopkeepers, farmers, fishermen, and merchants in African Muslim communities are Ajami users with good numeracy skills.52 Ironically, most of them know western numerals but they do not necessarily know the Arabic numerals. This is partly because the western numerals are readily available to them through the local currencies used in their communities.

According to Sam Niang, archivist at the Bibliothèque Cheikhoul Khadim in Touba, who was born and raised in the Murid community, though the traditional Quranic schools do not teach numeracy as a subject matter, students generally acquire numeracy in western numerals through a process that could be termed “currency-derived numeracy”, i.e. through their sustained exposure to the currency used in their communities. His experience taught him that Murid Ajami users learn western numerals primarily from the money that circulates in their communities and schools. These include the coins of 5 francs (dërëm), 10 francs (ñaari dërëm), 15 francs (ñetti dërëm), 25 francs (juróomi dërëm), 50 francs (fukki dërëm), and 100 francs (ñaar fukk) and banknotes such as 500 francs (téeméer), 1000 francs (ñaari téemeer), 5000 francs (junni), and 10000 francs (ñaari junni).

When students leave their communities and schools later, they enhance their numeracy skills in western numerals by learning from their supervisors. Thus, an Ajami literate apprentice tailor will learn from his boss how to take measurements and write them correctly and a novice shopkeeper, itinerant merchant, or businessman will improve his numeracy skills in western numerals by learning from his supervisor more arithmetic, how to use modern calculators, keep financial records, and write invoices for local customers who request them.53

The learned people who are literate in Arabic and in the local Ajami form are generally those who can use Arabic numerals. Thus, while in general one develops literacy and numeracy in the same language, the case of Ajami users demonstrates that these two skills can be acquired from two different languages, as the Fuuta Tooro Pulaar and Wolof Ajami business records demonstrate.54

Because they lack the potency associated with Arabic, Ajami materials are used to communicate both religious and non-religious information in African Muslim societies. The bulk of African Ajami materials consist of poems, which continue to be recited and chanted to the illiterate masses to convey the teachings of Islam to this day. Among the Murids, texts by Bamba or Ajami poems of his disciples often offer the occasion for a public performance where the singers and their vocalists sing the lines to a tune that they have adopted.55 The recitations of Ajami poems followed the tradition of the recitations of the Quran and Sufi poems. But African Ajami poems were also enriched by the local African musical traditions. While the skills needed for Wolof Ajami poets are, among others, mastery of the Ajami script and an understanding of Arabic and Wolof poetic devices, the skills required for singers of Ajami poems include literacy in Ajami, a good voice, and an understanding of appropriate singing styles for each poetic genre (referred to as “daaj” in Wolof). Murid Ajami poets and singers draw from the rich Wolof praise-singing tradition in content and form. Their poetry in its musicality and rhythm reflects the localisation of Islam.56

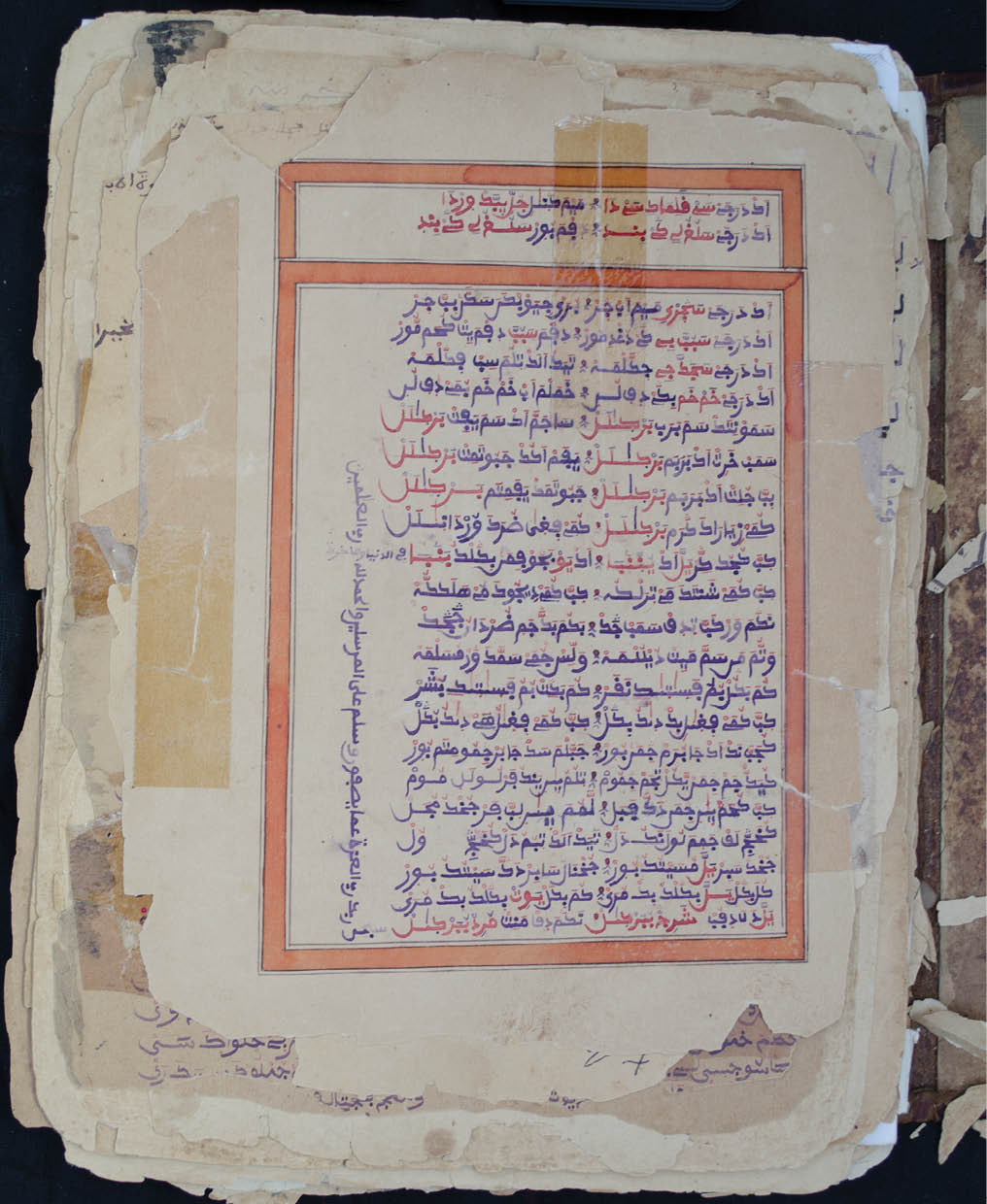

In order to execute his pedagogical and religious vision, Bamba focused on writing in Arabic for devotional purposes and to communicate with his peers, while at the same time he specifically tasked some of his senior disciples to communicate his ethos to the masses in their tongue (Wolof) through read, recited, and chanted Ajami poetry. The first four senior scholars he tasked to communicate his ethos to the masses were Mor Kairé, Samba Diarra Mbaye, Mbaye Diakhaté and Moussa Ka, the most famous Murid Ajami poet. All four were learned Muslim scholars who used to produce Arabic poems before Bamba tasked them to convey his teachings using Wolof in the form of Ajami poetry. They are responsible for the expansion of Ajami as a mass communication tool in Murid communities and its use as a badge of identity of their movement. A good example of their poetic work is a poem by Diakhaté illustrated in Fig. 11.4.

The division of tasks that Bamba implemented between him and his senior followers engendered four major categories of Ajamists (Ajami scholars): social scientists; esoteric scholars; poets and singers; and scribes and copyists.57 The first group consists of professional historians, genealogists and biographers such as Habibou Rassoulou Sy (1920-2001).58 The second consists of scholars whose primary work focuses on esoteric knowledge (such as prayers, protective devices and interpretations that unlock secrets hidden in Bamba’s writings and in other religious materials).59 The works of scholars in these two groups are primarily based upon fieldwork data, i.e. they travel from place to place to study with specialists and collect various types of information, including family histories and genealogies, prayers, and techniques of magical formulae to address particular problems in their communities. They also collect recipes for medical treatment of various illnesses. The third group consists of poets whose job is to compose religious and non-religious poetry to be sung by specialised singers.60 The last group consists of professional scribes and copyists. Their work ranges from translating Bamba’s Arabic poems into Wolof and making copies of important manuscripts, to writing correspondences in Ajami for illiterate customers who want to communicate with their Ajami literate friends or relatives. They also prepare public announcements, road signs and advertisements in Murid areas.61

The categorisation of the specialisations of Murid Ajami scholars, however, is not rigid. It is simply meant to reflect the major trends of Ajami scholars and their methods of production and dissemination of knowledge.62 This is because Ajami scholars are generally eclectic in their approach, and often combine activities and functions of several of the four categories. The following picture, Fig. 11.2, shows one eclectic Ajami scholar, who combines activities of social scientists and religious scholars.

Fig. 11.2 Mbaye Nguirane reading an Ajami excerpt of one of Moussa Ka’s poems during an interview with Fallou Ngom on 11 June 2011. Born in 1940 in Diourbel, Senegal, Nguirane is a leading specialist in Sufism, a historian and a public speaker.

Just as Ahmadou Bamba modelled his life on the Prophet Muhammad, his Ajamists also modelled their works on those of the poets who used to praise the prophet. The scholars who followed him also wrote his hagiography and genealogy — as illustrated in Fig. 11.5 — and compiled his teachings in Ajami as the poets and scholars of the prophet once did. To emphasise that he performs the same tasks for Bamba (in this life and the afterlife) as those of the poets of Prophet Muhammad, Ka declares: “on judgment day when Arab poets (who praise Prophet Muhammad) boast about the beauty of their language, I will praise Bamba in Wolof in ways that would dazzle them”.63

Additionally, the contemporary prolific Murid social scientist, El Hadji Mbacké, models the ranking of the sources he used to compile his Ajami anthologies of Bamba’s sayings and teachings entitled Waxtaani Sëriñ Tuubaa [Discussions of the Master of Tuubaa] on that of the Muhaddithun, Muslim scholars who compiled the hadith (sayings and accounts of the conduct of the Prophet).64 The Murid Ajami social scientists performed peripatetic travels in local communities and in Gabon and Mauritania where Bamba was exiled to document his experiences and compile his sayings and teachings.65

Another important factor that boosted the flourishing of Ajami among Murids is the fact that Bamba was proud of his black African identity. As Ousmane Kane reports, he was proud of being black and African and did not use the customary “principle of genealogical sophistication” to claim to be of Arab and/or Sharifian descent, which was an integral part of the system of legitimisation of Muslim leaders of West Africa and beyond.66 He denounced the racism of the Moor/Arabs who were “notorious for their disapproving attitude toward black Africans”.67 He noted in his book Masālik al-Jinān [Itineraries of Paradise] written between 1883 and 1887 the following: “The best person before God is the one who fears Him the most, without any sort of discrimination, and skin color cannot be the cause of idiocy or lack of knowledge of a person”.68

In the hagiographic poems of Murid Ajami scholars, Bamba’s call for racial equality constitutes one of the first major benchmarks of his emergence as a prominent Muslim leader concerned with racial justice within the Muslim community. Murid Ajami scholars interpreted his proud African identity and his views on the claims of Sharifian descent and on racial equality before God within the Muslim community as a call to utilise their read, recited, and chanted Ajami materials in order to cultivate an assertive black African Muslim identity within their communities. They used Ajami as a means of resistance against what they perceived as the Arabisation ideology that accompanied Islam in sub-Saharan Africa.69

Murid Ajami scholars disseminate these views to the masses and defended the legitimacy of Ajami in Islamic discourse. They separated Islamisation from Arabisation by untangling the inferred link between the holy status of Arabic (the language of the Quran) and the presumed superiority of the Arab ethnolinguistic group. A good example of a poem illustrating this effort is Ka’s Taxmiis bub Wolof. In this work, modelled on the classical Arabic poetic form called Takhmīs, structured around five-line verses, Ka challenges the hegemony of Arabic and asserts that the holy prestige of Arabic is derived from its proselytising function, and not from some inherent superiority of Arabic or Arabs over any ethnolinguistic group. He emphasises that just like Arabic, Aramaic (the language of Jesus) and Hebrew (the language of Moses and David) are equally sacred because they were the tongues through which God’s message was conveyed. He notes that all languages are equal and that any tongue that is used to convey God’s message acquires holy prestige.70

Murid Ajami poets strove to demonstrate that Islam does not require acculturation, forsaking one’s cultural and linguistic heritage. Instead, they contend that Islam requires exemplary ethical and spiritual excellence.71 The flourishing of Ajami and the assertive African identity of the Murids are entwined with these narratives in the works of Murid Ajami scholars. But these perspectives are unknown in the external academic literature because they are embedded in the Ajami sources that have been omitted in most studies of Muridiyya.72

The blossoming of Ajami in Murid communities followed the three phases of Bamba’s spiritual odyssey: the first decade of his movement (1883-1895); his exile to Gabon (1895-1902); and his exile to Mauritania and house arrests (1903-1927). In the first phase he diverged from the traditional Islamic education system and created three types of schools in rural areas. He created Daaray Alxuraan (Quranic schools), Daaray Xam-Xam (Knowledge Schools), and Daaray Tarbiyya (Ethical and Spiritual Vocational Schools). In the first schools, traditional Quranic instruction was offered. In the second, Islamic sciences were taught. His disciples in these two schools mostly came from learned families. In the third schools new adult disciples who were largely illiterate were given ethical and vocational training (including physical work) combined with gradual study of the Quran and his Arabic poems. These were the largest schools in the initial years of the movement. It is in these early Murid schools that Ajami literacy first began to spread widely and to become later the primary means of written communication among the Murids.73 The trend continued during the second phase of Bamba’s life. But the use was not drastically different from other communities.

But it is during the third phase (1903-1927) that the use of Ajami flourished as the dominant mass communication tool in Murid communities thanks to the works of the Ajami scholars who followed Bamba. The period encompassed Bamba’s exile to Mauritania (1903-1907) and his house arrests in Thieyène (1907-1912) and Diourbel (1912-1927). The three Murid Ajami master poets — Kairé, Mbaye and Diakhaté — visited Bamba in Mauritania where they became his disciples. They shifted from writing in Arabic as they did previously to devote the rest of their lives to Ajami. During the period of the house arrest in Diourbel, Ka, the youngest of the Murid Ajami master poets, contributed greatly to the expansion and popularisation of Ajami in Murid communities.74

Besides the traditional proselytising function of Ajami, Murid Ajami poets present Bamba as a local African hero and a blessing to humanity just as other saints and prophets were heroes of their people and God’s blessings to humanity.75 They routinely celebrate their proud African identity and treat their Ajami skills as assets, as the following verse by Kairé illustrates: “[Bamba] you made us erudite till we rival Arabs and compose poems both in Arabic and Ajami”.76 They produced a rich corpus of read, recited and chanted poems, which conveyed the teachings of Islam and Muridiyya, and reflected an enduring resistance against acculturation into the Arab and western cultures. The contents of their poems continue to resonate with people today, and are still read, recited, chanted and listened to in Murid communities.77

During Bamba’s house arrest in Diourbel, Ajami writing, reading and chanting became part of the major activities in Murid communities and schools along with copying, reading, reciting and chanting the Quran and Bamba’s poems. During Bamba’s time in Diourbel, his compound gradually became a centre of Islamic learning and scholarship, and Moorish and Wolof disciples and teachers flocked to the quarter to work as readers of the Quran and scribes, copying Quranic and other religious books destined for students in the new schools that were opened in the area.78 Translations of Bamba’s poems and other Islamic didactic and devotional materials into Ajami were also part of the regular activities during this period.79 The activities of copying, translating and chanting didactic and devotional materials continued. They have become important employment-generating activities in Murid communities as illustrated in Figs. 11.9 and 11.10.

Ajami poets such as Ka and Diakhaté used to meet in Diourbel to discuss Ajami poetry and techniques (metric, rhythms and versification) during Bamba’s house arrest there. The joint Ajami poem “Ma Tàgg Bàmba [Let me Praise Bamba]” was written during this period by Ka and Diakhaté.80 An important corpus of Ajami poems written by Bamba’s daughters also exists, but it remains unknown outside Murid communities. Ka and Sokhna Amy Cheikh, a daughter of Bamba, wrote together the popular Wolof Ajami poem entitled “Qasidak Wolofalu Maam Jaara [A Wolof Ajami Tribute to Maam Jaara]” to celebrate the virtues of Bamba’s mother, Maam Jaara Buso (or Mame Diarra Bousso in the French-based spelling).81 According to Sam Niang, Bamba’s daughter Sokhna Amy Cheikh contributed 21 verses to the poem. Niang indicates that Ka routinely assisted Bamba’s daughters in the writing of their Ajami poems.82 I have collected seven Ajami poems, 72 pages of manuscripts in total, written by Murid women. These include poems by two of Bamba’s other daughters: Sokhna Mai Sakhir (1925-1999) and Sokhna Mai Kabir (1908-1964), and one poem by Sokkna Aminatou Cissé, a contemporary Murid female Ajamist who does not belong to Bamba’s family.83

The Murid Ajami poets generally worked with assistants who helped to decorate their poems with colours and designs (Fig. 11.6) and to vocalise them, just as some of Bamba’s senior disciples decorated his Arabic odes and vocalised them.84 The tradition is derived from the colourful calligraphic copying of the Quran.85

Murid Ajami poems are grounded in the local culture. They contain maxims and metaphors drawn from it, as illustrated by the following metaphor in one of Diakhaté’s poems: “If you cannot resist worldly pleasures and your baser instinct for a day, you are no wrestler or if you are, you are (nothing but) a sand-eating wrestler”.86 Wrestling is the most popular traditional sport in Senegambia. The image of a wrestler is used to underscore the spiritual potency of religious leaders in the Wolof society. Mbër muy mëq suuf (a sand-eating wrestler) is the defeated wrestler thrown down so hard that his face and mouth are filled with sand. Diakhaté uses this local metaphor to refer to religious leaders who lack the appropriate ethical and spiritual credentials.

The recitation and chanting of such materials facilitated the spread of the teachings of Muridiyya and Ajami literacy. Many illiterate people memorised the lyrics of the Ajami poems they heard repeatedly before later learning the Ajami script. Among them are second language speakers of Wolof such as members of the Seereer ethnolinguistic group of the Baol area of Senegal, the birthplace of Muridiyya.87 Many Seereer of Baol joined Muridiyya in its early days because of the beautiful and inspirational hagiographic songs of Ajami poets they heard. They learned the Ajami script when they joined the movement and became exposed to greater Murid influence.88

This was the case of Cheikh Ngom (1941-1996), a Seereer who was born and raised in the Baol area, spoke Wolof as a second language, and acquired Wolof Ajami literacy as a result of his membership to Muridiyya. When he died in 1996, he left over 900 pages of materials in Arabic and Ajami. The Arabic materials consist of Islamic litanies, formulae, and figures used in prayers, medicinal treatment and protective devices. The Wolof Ajami materials, the bulk of his written legacy, encompass his personal records — records of important events in his life, his family and community, and his financial dealings. However, his entire written legacy includes no Ajami text in Seereer, his mother tongue.89

The Wolof Ajami songs that attracted many Seereer people of the Baol area to Muridiyya include the two popular masterpieces by Ka, which describe the poignant lived and spiritual odyssey of Ahmadou Bamba.90 These works recount Bamba’s suffering, his confrontations with local immoral Muslim leaders, traditional rulers, and the French colonial administration, as well as his exemplary virtues, spiritual achievements, and his mission on earth from his emergence as a prominent religious leader in 1883 to his death in 1927.

The fact that some scholars taught Ajami literacy or used Ajami as a vehicle to teach other subjects, including Arabic literacy and Quranic lessons, also boosted Ajami among Murids. The Ajami book Fonk sa Bopp di Wax li Nga Nàmp [Respect Yourself by Speaking your Mother Tongue] written by the Murid scholar Habibou Rassoulou Sy (1920-2001) specifically teaches Ajami literacy and proposes an indigenous standard for Wolof Ajami users.91 In contrast, the contemporary Murid Ajami scholar Mouhammadou Moustapha Mbacké Falilou uses French and Ajami to teach Arabic literacy and key concepts of the Quran to Ajami literates who do not know the unmodified Arabic script.92 Mbacké’s audience consists of individuals who have acquired Ajami skills through “music-derived literacy”, but are unfamiliar with the original Arabic script. This phenomenon of acquiring Ajami skills without prior literacy in the Arabic script, while unusual, is easy to understand since recitation and chanting pervade Murid communities. Murid disciples were routinely arrested and put in prison for disturbing the peace in Diourbel with their noisy chanting.93

The phenomenon of music-derived literacy reveals that there are multiple channels through which Ajami literacy is developed in African Muslim communities. Music-derived literacy in Murid communities is sustained by the largely unknown but remarkable investments that Murids have made in the audio recordings and publishing presses. Today Murids own the largest network of homegrown, private printing presses and media outlets in Senegambia. They produced and disseminated devotional and didactic materials ever since Bamba’s house arrest in Diourbel. To make this possible, since the 1950s the Murids have invested in printing presses and recording studios. Their written and verbalised materials pervade the Islamic bookstores in marketplaces in Murid areas and urban centres in Senegal. Many of their textual and audiovisual materials are also available online.94

Conclusion: the significance of Ajami

Through the discussion of African Ajami traditions in general and the Murid Wolof Ajami materials and their historical context, I have attempted to demonstrate that the prevailing treatment of Africa as lacking written traditions is misleading.95 It disregards the important written traditions of the continent, which are not taken into account in official literacy statistics and in the works of many historians, anthropologists and political scientists, to name only a few disciplines. Yet, just like written Arabic and European languages hold the Arab and European knowledge systems, so too Ajami sources are reservoirs of the knowledge systems of many African societies.

The omission, dismissal and downplaying of the significance of African Ajami traditions among many scholars — including language planners, and governmental and non-governmental professionals — have perpetuated the stereotypes which have devalued sub-Saharan Africa’s people and their languages for centuries. Ka and Frederike Lüpke deplore and trace these stereotypes to the Arab-centric and Euro-centric traditions. While the tendency is to treat stereotypical representations and racial prejudice against the black population of sub-Saharan Africa as an exclusive Euro-Christian problem, the enduring historical facts tell a different story.

The devaluing of sub-Saharan Africans, their languages and cultures are well established in the works of Arab Muslim scholars, including the celebrated Ibn Battuta and Ibn Khaldun. Both were excessively preoccupied with skin colour and believed that sub-Saharan Africa’s black people were naturally inferior.96 Their works and those of like-minded scholars have bequeathed many people with the enduring fallacy that insightful knowledge about Africa is either oral or written in non-African languages, especially in European languages.97

Because of these misconceptions, many students of Africa continue to disregard the unfiltered voices of millions of people captured in Ajami materials as unworthy of scholarly attention. As Lüpke laments, even the few accounts in the educational literature that mention pre-colonial and ongoing Ajami writing traditions at all tend to stress their marginality.98 But the voices omitted due to the neglect of Ajami traditions contain illuminating insights that force revisions of various aspects of our understanding of Africa’s history, cultures, the blending of the African and Islamic knowledge systems, and the varying African responses to both colonisation and Islamisation (along with its accompanying Arabisation that the Murid Ajami sources challenge relentlessly).

It is encouraging to note a growing interest in Africa’s Ajami traditions as the sources cited throughout this chapter demonstrate. The current scholarly efforts on African Ajami orthographies and the new digital repositories of Ajami materials are important steps toward the crucial phase of translating the insights in African Ajami materials into major European languages and Arabic. It would be fascinating to see, for example, what intellectual response Ka’s Taxmiis bub Wolof would receive in the Arab world, if it were translated into Arabic. This is the work in which he celebrates his Islamic faith but rejects the Arabisation ideology that he believed came along with Islam in sub-Saharan Africa. This is a unique perspective that is only documented in Ajami sources. The translation of Ajami materials into major languages would open new doors for students of Africa across disciplines, giving access into hitherto unknown insights on the thinking, knowledge systems, moral philosophies, and religious and secular preoccupations of many African communities.

In addition to the scholarly potential that African Ajami sources hold, there are practical implications of Ajami in Africa. The Senegalese government in collaboration with UNESCO and ISESCO developed standard orthographies for Wolof and Pulaar in 1987. ISESCO subsequently produced the first Afro-Arabic keyboard and typewriter.99 The efforts resulted in what is commonly known as the caractères arabes harmonisés (harmonised Arabic letters) conceived as a top-down model of standardisation, proposing foreign standardised diacritics to write the idiosyncratic African consonants and vowels that Arabic lacks. This necessitated the introduction of new diacritics proposed to write the Wolof vowels o, e, é, and ë. The vowel o is represented with a reversed ḍammah above the consonant; é with a ḍammah below the consonant; e with a reversed ḍammah below the consonant, and ë with a crossed sukūn above the consonant. In the proposed standardised system, p is also written as پ.100

With the exception of the reversed ḍammah above consonants attested in Bambara Ajami manuscripts,101 none of the proposed modified Arabic letters is traditionally used in West African Ajami systems. It has been argued that the local Wolof Ajami letters (so-called les lettres vieillies) are found in ancient texts. This suggests that Wolof Ajami letters are rarely or not found in current Ajami materials.102 This is incorrect. The so-called les lettres vieillies remain the most widely used letters in Wolof communities as illustrated by Figs. 11.5, 11.7, 11.8 and 11.12, and by the plethora of Wolof Ajami materials in the digital repositories cited throughout this article.

While p is written in Persian, Urdu, Kurdish, Uyghur, Pashto, Sindhi and Osmanli (Ottoman Turkish) as پ,103 it is never written in this way in West African Ajami traditions. In Wolof and the other local African Ajami traditions, p is typically written with a single bāʾ (ب) or a bāʾ with an additional three dots below or above. Similarly, the letter proposed for the voiced velar consonant g (گ) is the same as the one used in Persian, Uyghur, Kurdish, Urdu and Sindhi.104 But this letter is also not used in West African Ajami writing systems. While the proposed approach was reasonable because some of the new characters were already encoded in Unicode, most were unknown in the region prior to the project. Symptomatically, the local Ajami systems that had devised their own diacritics to represent their peculiar vowels and their consonants that do not exist in Arabic, were excluded in the standardisation effort.

This approach was also utilised for Senegambian Mandinka. The result is that although books, a keyboard and a typewriter were produced for the standardised Ajami orthographies, there is no single functioning school or community in Senegambia that uses the caractères arabes harmonisés. Ajami users continue to utilise their centuries-old Ajami orthographies to which they are loyal for cultural, historical and practical reasons as illustrated in Figs. 11.4-11.8, and 11.12.105 Most of the documents produced with the caractères arabes harmonisés are thus dormant in the offices where they were produced and in the homes of the people who participated in the harmonisation project.

The experience with caractères arabes harmonisés shows that great initiatives can fail because of a wrong approach. It demonstrates that standardisation of Ajami scripts must be carried out bottom up, and must be grounded in local realities, if it is to be successful. Rather than teaching Ajami users who have been using their local Ajami orthographies for centuries to learn new diacritics and letters they have never seen, the diacritics and letters to be used as standards must be drawn from the pool of those already in use in local communities.

The standardisation of Ajami orthographies, if done well, has great potential for Africa. Given the scope of usage of Ajami in the continent, standardised Ajami orthographies grounded in a bottom-up approach have transformative potentials. They could help to modernise Quranic schools across Islamised Africa and develop curricula for the teaching of such subjects as science, mathematics, geography and history, thereby exposing students to the world outside their communities.106 Well-harmonised African Ajami systems could also open up new means of communication never possible before, and they could unite Ajami users from the same ethnolinguistic group from different countries segmented by European official languages. They equally have the potential of enhancing access to and communication with millions of Ajami users and improve the work of educators, journalists, public health workers, and local and international NGOs in areas where Ajami is the prevailing medium of written communication.107

Appendix: sample of Murid materials

A protective device

Fig. 11.3 This image is the last page of Moukhtar Ndong’s Ajami healing and protection manual, Manāficul Muslim (EAP334/12/2, image 19), CC BY.

The use of the Arabic numerals inside the design (made with the word Allāh) requires skills in Islamic numerology and mathematics.108 The image illustrates the different roles assigned to Arabic and Ajami in African Muslim societies. Only Arabic letters and numerals are used in the image because of their purported potencies. Ndong omitted the instructions on how to use the formula. The omission is not accidental, but devised to protect the potent knowledge of the formula. Protection of such potent knowledge is typically done by partial or full omission of information. Though some ingredients or instructions may be provided in Ajami, a crucial piece of information or the entire instruction may be omitted. This is because the authors generally acquired the knowledge through arduous peripatetic learning and they only provide it to deserving individuals.

Poem: “In the Name of Your Quills and Ink”

Fig. 11.4 “In the Name of Your Quills and Ink” by the master poet and social critic, Mbaye Diakhaté, written between 1902 and 1954 (EAP334/4/2, image 46), CC BY.

A Wolof transcription of the poem reads:109

Ak darajay say xalima aki say daa, may ma ngëneeli julli yépp ak wirda

Ak darajay sa loxo lii ngay binde, def ma bu wér sa loxo lii ngay binde

Ak darajay sa cër yii may ma ab cër, bu rëy ci yaw bu gëna sàkkan bépp cër

Ak darajay sa bopp bii ngay dox di muur, def ma sa bopp def ma it ku am muur

Ak darajay sa jàkka jii jëgal ma, tey ak ëllëg te lu ma sib fegal ma

Ak darajay xam-xam bi ngay defe lu ne, xamal ma ab xam-xam bu may defe lu ne

Samaw nit ak sama barab barkeelal, saa jëmm ak sama yëf it barkeelal

Samab xarit ak barabam barkeelal, yëfam akug njabootam it barkeelal

Bépp jullit ak barabam barkeelal, njabootam ak yëfam it barkeelal

Ku may siyaara ka gërëm barkeelal, ku may fexe lor aka wor daaneelal

Képp ku jóg ngir Yàlla ak yonent ba ak yaw ba ñów fi man, begal ko Bàmba

Képp ku may sant aka may teral ko, képp ku may diiju aka moy alak ko

Na nga ma wër kàpp te def sa ab ñag, ba ku ma bëgga jéema lor daanu ca ñag

Wàttu ma man sàmm ma it doylul ma, wàllis ñu may sàmm aka wër musal ma

Ku ma bëggul bu mu faseeti aki naqar, ku ma bëgg it bu mu faseeti aki busar

Képp ku may fexeeli mbeg dee ko begal, képp ku may fexeeli ay dee ko bugal

Ku jàpp nak ag jaamburam ci man bu wér, jàppal ma sag jaambur ci moom itam bu wér

Ku yëngu jëm ci man yëngul te jëm ci moom, te lu mu yéene yan ko far loolale moom

Képp ku am yéene ci man dëgg, fabal la mu ma yéene lépp far jox ko mu jël

Ku xàcci lëf jam ma loola na ko dal tey ak ëlëg, te bu mu dal ku xàcciwul

Jox nga sa mbir Yàlla mu saytu ko bu wér, jox naa la sama mbir dëgg saytu ko bu wér

Ku la begal Yàlla begal ko mbeg mu rëy, ku ma begal yaw it begal ko mbeg mu rëy

Yàlla daa la def sëriñ bu barkeel, na nga ma def man it murid bu barkeel

Subhāna rabika rabi’l-cizzati camā yasifūna wa salāmu calā’l-mursalīna

wa’l-hamdu li’llāhi rabi’l-cālamīna

An English translation of the poem reads:

In the name of your quills and ink, offer me blessings of all prayers and invocations.

In the name of your hand you write with, make me your hand you write with.

In the name of your distinctions, offer me a distinction greater than any distinction.

In the name of your head you always cover,110 make me yourself and a fortunate person.

In the name of your mosque, forgive me now and ever, and save me from things I dislike.

In the name of your multifaceted knowledge, offer me multifaceted knowledge.

Bless my people and my home and bless my body and my property.

Bless my friends and their homes and bless their properties and families.

Bless all Muslims and their homes and bless their families and properties.

Bless whoever visits and thanks me and subdue whoever seeks to harm and to betray me.

Bamba, make happy whoever comes to me for the sake of God, the Prophet, and you.

Honor whoever praises and offers me gifts; and curse whoever demeans and offends me.

Surround and fence me so that whoever seeks to harm me falls on the fence.

Sustain me, protect me, fulfil me, and bring me people who will shield and save me.

Make ever unhappy whoever dislikes me, and make ever happy whoever likes me.

Make ever happy whoever seeks to please me, and punish whoever wishes me ill.

Whoever leaves me alone leave him alone too.

Whoever threatens me, threaten him, and make his ill-wishes fall back onto him.

Whoever wishes me well, take all his good wishes and give them all back to him.

Whoever hits me, punished him now and ever and leave alone whoever did not hit me.

You left your affairs to God Who addressed them, I leave you with mine, address them.

May God bring joy to anyone who makes you joyful and to anyone who brings me joy.

God has made you a blessed spiritual leader; make me a blessed Murid disciple.

Your Lord is Sacred and unblemished of all that is alleged against Him; and He is The Most Exalted. May God’s blessing be upon all His Messengers. All praise belongs to God, The Sustainer of all the worlds.

Fig. 11.5 A page from Habibou Rassoulou Sy’s Lawtanuk Barka [Flourishing of Baraka], a genealogy book of the family of Boroom Tuubaa (Ahmadou Bamba). Bamba is located in the circle in bold (EAP334/12/1, image 6), CC BY.

The book from which this page is taken describes in great detail the maternal and paternal ancestry of Ahmadou Bamba from its Fulani roots to its full Wolofisation. The page above focuses on Bamba’s great maternal grandfather and his descendants. The Ajami note at the bottom of the page reads as follows: “The Grandfather Ahmadou Sokhna Bousso Mbacké and his five sons and five daughters. May God be pleased with them”.111

Using chronograms based on Maghrib Arabic numerals, Sy also provides in the book the birth and death dates of Bamba’s paternal ancestor (Maharame Mbacké). Sy reveals that he was born in the year Ayqashi (y+q+sh = 10+100+1000 = AH 1110/1698 CE) and died in the year Yurushi (y+r+sh = 10+200+1000 = AH 1210/ 1795 CE).112 This dating system, which is commonly used in Murid Ajami sources, remains unknown in the existing historical studies on Muridiyya.

Fig. 11.6 A work of Ajami art displaying a key Murid maxim: “Loo yootu jàpp ko (Seize whatever you reach)” in Mbaye Diakhaté’s “Yow miy Murid, Seetal Ayib yi La Wër [You, the Murid, Beware of the Challenges Surrounding You]” (EAP334/8/1, image 29).

The maxim Loo yootu jàpp ko (Seize whatever you reach) echoes the pivotal teaching of optimism of Muridiyya. Muridiyya teaches that genuine Murids will achieve their wishes in life as a prelude for their paradise in the afterlife.

Fig. 11.7 Photo of a shopkeeper’s Ajami advertisement in Diourbel, the heartland of Muridiyya, taken in June 2009. The Ajami text reads as follows: “Fii dañu fiy wecciku ay Qasā’id aki band(u) ak kayiti kaamil aki daa” [Poems, audiocassettes, Quran-copying quality paper and ink are sold here]”. The word TIGO refers to a local mobile phone company.

The image illustrates the digraphia situation in Diourbel where Ajami dominates French literacy. The entire message of the advertisement is in Ajami because it targets Ajami users who represent the majority of the population of the region of Diourbel.

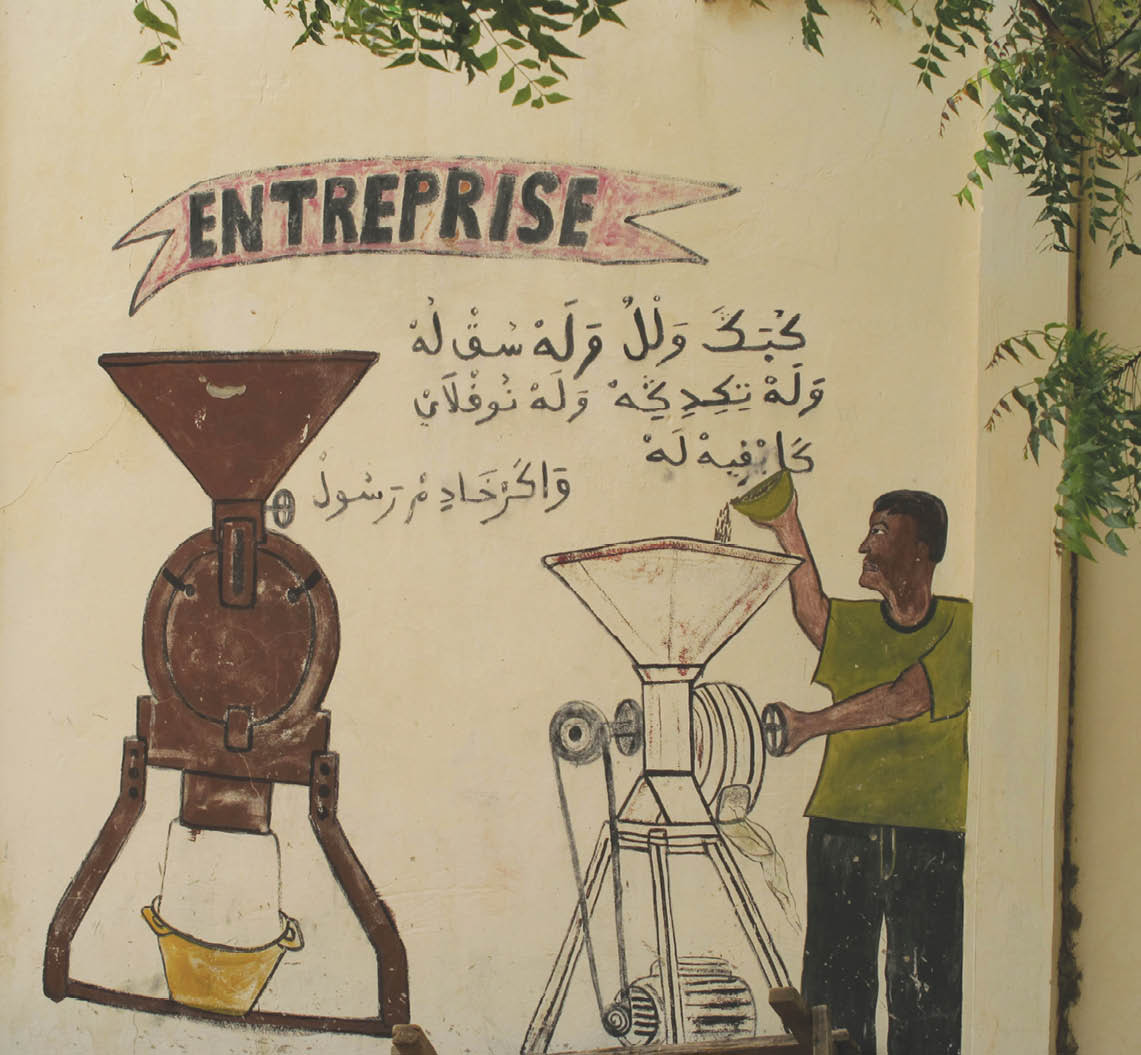

A mill owner’s advertisement

Similar to the preceding image, this one also reflects the digraphia situation in Diourbel and the significance of Ajami literacy in the region. The Eastern (Mashriqī) fāʾ (ف) and qāf (ق) are used for the Wolof f and q in the Ajami advertisement rather than the usual Western (Maghribī) fāʾ (ڢ) and qāf (ڧ) commonly found in West African Ajami materials.113

Fig. 11.8 A mill owner’s advertisement for grinding grains, including peanuts. The Ajami text reads as follows: “Ku bëgg wàllu wàlla soqlu wàlla tigadege wàlla nooflaay; kaay fii la. Waa Kër Xaadimu Rasuul [If you want (your grains) pounded or grinded or peanut butter effortlessly; come here. The People of The Servant of the Prophet (Ahmadou Bamba)]”. Photo taken in Diourbel in June 2009.

The word tigadege (peanut butter) is written as tikidigi. While these variations constitute challenges for outsiders to read Ajami materials, they do not pose problems for local Ajami users. This is because local Ajami users know the dialectal, sociolectal, idiolectal, and stylistic variations in Ajami materials of their communities. Just like most native speakers and educated people can predict Arabic vowels in a work, so too Ajami users can generally predict the consonant or vowel the author intended based on their knowledge of the contextual and stylistic cues in Ajami materials of their communities. The text also reflects the use of Ajami as the badge of identity among Murids. The owner of this small business asserts his Murid identity with the last phrase of his advertisement: “Waa Kër Xaadimu Rasuul [The People of the Servant of the Prophet]”. “Xaadimu Rasuul [The Servant of the Prophet]” is one of the most popular names of Bamba, the founder of Muridiyya.

Shopping for Ajami texts

Fig. 11.9 Shopping for Ajami materials in Touba, Senegal during the 2012 Màggal.

Besides the Ajami materials, the image captures the centrality of work ethic in Muridiyya. The patchwork clothing is a symbol of the group of Murids who emulate Ibra Fall (called “Baye Fall”), the most loyal disciple of Bamba popularly known as the apostle of work ethic. The belt around the man’s waist symbolises “the belt of work ethic”.

Shopping for Ajami materials and Murid paraphernalia

Fig. 11.10 Shopping for Ajami materials and Murid paraphernalia

in Touba, Senegal, 12 July 2014.

An advertisement for the mobile phone company Orange

Fig. 11.11 An advertisement in Ajami for the mobile phone company Orange in a suburb of the Murid holy city of Touba, 12 July 2014.

Similar to image 7 and 8, this image also reflects the digraphia situation in Touba, which is located in the region of Diourbel. It is worth noting that the advertisement is not written with the caractères arabes harmonisés, which most people do not know. The Ajami text is written with Eastern Arabic script (Mashriqī) which many people now know rather than the Maghribī script more commonly used in West Africa. It reads as follows in standard Wolof: “Jokko leen ci ni mu leen neexee ak Illimix #250#. Woote (below a telephone icon), mesaas (below the message icon), and enterneet (below the icon @) [Communicate freely with Illimix by dialling #250# to call, send a text message, or access the Internet]”. The Wolof vowel e is systematically written with a kasrah, which is one way to write the vowel in Wolof Ajami.114 The phone company understood that Ajami is key for the effective marketing of its product in the Murid areas.

In the region of Diourbel, all important announcements destined to the public — be they public health announcements, calls to action, speeches or official letters of the highest authority of the Murid order (the Khalife Général des Mourides) — are first written in Ajami before their subsequent reading on television and radio stations and translated into French for wider national dissemination. Murids nationwide often receive copies of the original announcements in Ajami scripts through their regional leaders. Such a use of Ajami as a mass communication tool is a uniquely Murid phenomenon in Senegal.115 The Murid have revalorised Ajami and made it their preferred written communication tool and their badge of identity.

The Orange company is thus ahead of the Senegalese government (which continues to treat Ajami users as illiterate) in acknowledging the large constituent of Ajami users and the economic benefits of engaging with them. With similar efforts of private individuals, NGOs and companies, we hope that African governments will realise the benefits of including Ajami texts in the educational, economic and developmental priorities of their post-colonial states.

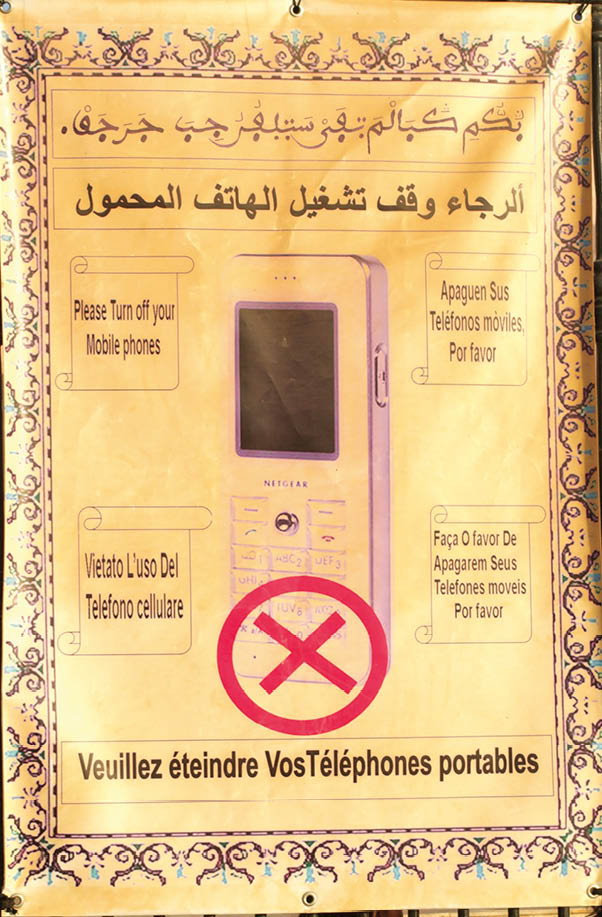

A public announcement to turn off mobile phones

Fig. 11.12 A public announcement in Ajami and six foreign languages asking pilgrims who attended the 2011 Màggal to turn off their mobile phones when entering the Great Mosque of Touba where Ahmadou Bamba is buried, 11 January 2011.

Because Wolofal (Wolof Ajami) is the primary medium of written communication among the Murids, the announcement naturally begins in Ajami. It starts with the following words: “Mbokk mi, nga baal ma te fay sa telefonu jiba. Jërëjëf [Fellow disciple, please turn off your mobile phone. Thank you]”. The prenasal mb is written with bāʾ with three dots above, which is also used to write p in Wolofal. The prenasal ng is written with a kāf with three dots above, which is also used for g in Wolofal. The dot below the letter is used for the vowel e. The vowel o is rendered with a ḍammah, rather than a ḍammah with a dot inside, which is common in Wolofal texts. The centralised vowel ë is rendered with the fatḥa as commonly attested in Wolofal texts. f is written with the Maghrib fāʾ, with one dot below the letter at word medial position and without a dot at word final position, as commonly attested in Wolofal.116

The second line of the announcement communicates the message of the Ajami text in Arabic. Subsequently, the message is communicated in five European languages: English, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese and French.117 The use of the seven languages in the announcement echoes the global dimension of the Màggal. The goal of the announcement is to communicate with the international body of pilgrims who come from around the world to attend the Màggal. International pilgrims include a substantial number of Murids from the diaspora, comprising North America, Europe, and across Africa. The 2011 Màggal brought more than three million people of all races, ages and genders to Touba from around the world for 48 hours, and attracted an estimated five billion Francs CFA (about U.S. $10,400,000) exclusively used for the food and expenses of the event.118

References

Ba, Oumar, Ahmadou Bamba face aux autorités coloniales, 1889-1927 (France: Abbeville, Imprimerie F. Paillart, 1982).

Babou, Cheikh Anta, Fighting the Greater Jihad: Amadu Bamba and the Founding of the Muridiyya of Senegal, 1853-1913 (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2007).

Besson, Ludovic, “Les collectes ornithologiques sénégalais de Victor Planchat dans la collection Albert Maës”, Symbioses nouvelle série, 30/2 (2013), 2-16.

Bondarev, Dmitry, “Old Kanembu and Kanuri in Arabic Script: Phonology Through the Graphic System”, in The Arabic Script in Africa: Studies in the Use of a Writing System, ed. by Meikal Mumin and Kees Versteegh (Leiden: Brill, 2014), pp. 107-42.

Bougrine, Nadia, and Ludovic Besson, “Décryptage des termes en wolof et soninké utilisés pour les collectes ornithologiques de Victor Planchat”, Symbioses nouvelle série, 31/1 (2013), 1-8.

Boyd, Jean, and Beverly Mack, Collected Works of Nana Asma’u: Daughter of Usman ɗan Fodiyo, 1793-1864 (East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 1997).

Breedveld, Anneke, “Influence of Arabic Poetry on the Composition and Dating of Fulfulde Jihad Poetry in Yola (Nigeria)”, in The Arabic Script in Africa: Studies in the Use of a Writing System, ed. by Meikal Mumin and Kees Versteegh (Leiden: Brill, 2014), pp. 143-57.

Camara, Sana, “Ajami Literature in Senegal: The Example of Sëriñ Muusaa Ka, Poet and Biographer”, Research in African Literatures, 28/3 (1997), 163-82.

Chrisomalis, Stephen, Numerical Notation: A Comparative History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Chtatou, Mohamed, Using Arabic Script in Writing the Languages of the People of Muslim Africa (Rabat: Institute of African Studies, 1992).

Cissé, Mamadou, “Écrits et écriture en Afrique de l’ouest”, Sudlangue: revue électronique internationale de sciences du language, 6 (2007), 77-78.

Conklin, Alice L., The French Republican Idea of Empire in France and West Africa, 1895-1930, 1st edn. (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1997).

Alidou, Ousseina D., Engaging Modernity: Muslim Women and the Politics of Agency in Postcolonial Niger (Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2005).

Daniels, Peter T., “The Type and Spread of Arabic Script”, in The Arabic Script in Africa: Studies in the Use of a Writing System, ed. by Meikal Mumin and Kees Versteegh (Leiden: Brill, 2014), pp. 34-39.

Diakhaté, Souhaibou, Xasiday Wolofalu Sëriñ Mbay Jaxate: Li War ab Sëriñ ak ab Taalube [Ajami Poems of Mbay Jaxate: Duties of Leaders and Disciples] (Dakar: Imprimerie Issa Niang, [n.d.]).

Dieng, Bassirou, and Diaô Faye, L’Épopée de Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba de Serigne Moussa Ka: Jasaa-u Sakóor-u Géej gi–Jasaa-u Sakóor Jéeri ji (Dakar: Presses Universitaires de Dakar, 2006).

Diop, Cheikh Anta, Nations nègres et culture, 4th edn. (Dakar: Présence Africaine, 1979).

Diringer, David, The Alphabet: A Key to the History of Mankind (New York: Philosophical Library, 1948).

Donaldson, Coleman, “Jula Ajami in Burkina Faso: A Grassroots Literacy in the Former Kong Empire”, Working Papers in Educational Linguistics, 28/2 (2013), 19-36.

Dumont, Fernand, La pensée religieuse d’Amadou Bamba (Dakar: Nouvelles Éditions Africaines, 1975).

El Hamel, Chouki, Black Morocco: A History of Slavery, Race, and Islam (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Gérard, Albert, African Language Literatures (Washington, DC: Three Continents Press, 1891).

Glover, John, Sufism and Jihad in Modern Senegal: The Murid Order (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2007).

Gutelius, David, “Newly Discovered 10th/16th c. Ajami Manuscript in Niger Kel Tamagheq History”, Saharan Studies Newsletter, 8/1-2 (2000), 6.

Hall, Bruce S., A History of Race in Muslim West Africa, 1600-1960 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Hamès, Constant, ed., Coran et Talismans: Textes et Pratiques Magiques en Milieu Musulman (Paris: Éditions Karthala, 2007).

Hanson, Hamza Yuyuf, “The Sunna: The Way of The Prophet Muhammad”, in Voices of Islam, ed. by Vincent J. Cornell, 5 (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2007), pp. 125-47.

Haron, Muhammed, “The Making, Preservation and Study of South African Ajami Manuscripts and Texts”, Sudanic Africa, 12 (2001), 1-14.

Hassane, Moulaye, “Ajami in Africa: The Use of Arabic Script in the Transcription of African Languages”, in The Meaning of Timbuktu, ed. by Shamil Jeppie and Souleymane Bachir Diagne (Cape Town: Human Sciences Research Council 2008), pp. 115-17.

Hiskett, Mervyn, A History of Hausa Islamic Verse (London: University of London School of Oriental and African Studies, 1975).

Humery, Marie-Ève, “Fula and the Ajami Writing System in the Haalpulaar Society of Fuuta Tooro (Senegal and Mauritania): A Specific ‘Restricted Literacy’”, in The Arabic Script in Africa: Studies in the Use of a Writing System, ed. by Meikal Mumin and Kees Versteegh (Leiden: Brill, 2014), pp. 173-98.

Ka, Moussa, Waa ji Muusaa Bul Fàtte Waa ja fa Tuubaa [Dear Moussa, Do not Forget the Man in Touba] (Dakar: Imprimerie Islamique al-Wafaa, 1995).

—, Jasaawu Sakóor: Yoonu Géej gi [Reward of the Grateful: The Odyssey by Sea] (Dakar: Librairie Touba Darou Khoudoss, 1997).

—, Jasaawu Sakóor: Yoonu Jéeri ji [Reward of the Grateful: The Odyssey by Land] (Rufisque: Afrique Impression, 2006).

—, Taxmiis bub Wolof [The Wolof Takhmīs] (Dakar: Imprimerie Librairie Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba, [n.d.]).

—, and Sokhna Amy Cheikh Mbacké, Qasidak Wolofalu Maam Jaara [A Wolof Ajami Tribute to Maam Jaara] (Touba: Ibrahima Diokhané, [n.d.]).

Kane, Ousmane, Les intellectuels Africains non-Europhones (Dakar: Codesria, 2002), p. 8.

—, The Homeland Is the Arena: Religion, Transnationalism, and the Integration of Senegalese Immigrants in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

Last, Murray, “The Book and the Nature of Knowledge in Muslim Northern Nigeria, 1457-2007”, in The Trans-Saharan Book Trade: Manuscript Culture, Arabic Literacy and Intellectual History in Muslim Africa, ed. by Graziano Krätli and Ghislaine Lydon (Leiden: Brill, 2011), pp. 208-11.

Luffin, Xavier, “Swahili Documents from Congo (19th Century): Variations in Orthography”, in The Arabic Script in Africa: Studies in the Use of a Writing System, ed. by Meikal Mumin and Kees Versteegh (Leiden: Brill, 2014), pp. 311-17.

Lüpke, Frederike, “Language Planning in West Africa — Who Writes the Script?”, in Language Documentation and Description: Volume II, ed. by Peter K. Austin (London: SOAS, 2004), pp. 90-107.

Lydon, Ghislaine, “A Thirst for Knowledge: Arabic Literacy, Writing Paper and Saharan Bibliophiles in the Southern Sahara”, in The Trans-Saharan Book Trade: Manuscript Culture, Arabic Literacy and Intellectual History in Muslim Africa, ed. by Graziano Krätli and Ghislaine Lydon (Leiden: Brill, 2011), pp. 37-38.

Mack, Beverly B., and Jean Boyd, One Woman’s Jihad: Nana Asma’u-Scholar and Scribe (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2000).

Mbacké, Abdoul Aziz, Ways Unto Heaven (Dakar: Majalis Research Project, 2009).

Mbacké, El Hadji, Waxtaani Sëriñ Tuubaa [Discussions of The Master of Tuubaa], 1 (Dakar: Imprimerie Cheikh Ahmadal Khadim, 2005).

Mbacké, Khadim, Sufism and Religious Brotherhoods in Senegal, trans. by Eric Ross, ed. by John Hunwick (Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener, 2005).

Mbacké, Mouhammadou Moustapha Falilou, Afdhalul Hiraf-Taclīmu Haraf Ngir Fer ijji [The Best Letters-Teaching Letters for Literacy] (Touba: [n. pub.], 1995).

Mbacké, Soxna Mai Kabir, Maymunatu, Bintul Xadiim [Maymunatu, Daughter of The Servant] (Dakar: Imprimerie Serigne Saliou Mbacké, 2007).

Mbacké, Sokhna Mai Sakhir, Al Hamdu li’llāhi Ma Sant Yàlla [Thanks be to God, Let Me Grateful to God] (Dakar: Imprimerie Serigne Saliou Mbacké, 2007).

McLaughlin, Fiona, “Dakar Wolof and the Configuration of an Urban Identity”, Journal of African Cultural Studies, 14 (2001), 153-72.

Mumin, Meikal, “The Arabic Script in Africa: Understudied Literacy”, in The Arabic Script in Africa: Studies in the Use of a Writing System, ed. by Meikal Mumin and Kees Versteegh (Leiden: Brill, 2014), pp. 41-62.

Nasr, Seyyed Hossein, Islamic Art and Spirituality (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1987).

Ngom, Fallou, “Ahmadu Bamba’s Pedagogy and the Development of Ajami Literature”, African Studies Review, 52/1 (2009), 99-124.

—, “Ajami Script in the Senegalese Speech Community”, Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies, 10/1 (2010), 1-23.

—, “Murīd Identity and Wolof Ajami Literature in Senegal”, in Development, Modernism and Modernity in Africa, ed. by Augustine Agwuele (New York: Routledge, 2012), pp. 62-78.

—, and Alex Zito, “Sub-Saharan African Literature: cAjamī”, in Encyclopaedia of Islam III, ed. by Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas and Everett Rowson (Leiden: Brill Online, 2014), http://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-3/sub-saharan-african-literature-ajami-COM_26630

Niang, Mahmoud, Jaar-jaari Boroom Tuubaa [Itineraries of the Master of Tuubaa] (Dakar: Librairie Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba, 1997).

O’Brien, Donald B., Mourides of Senegal: The Political and Economic Organization of an Islamic Brotherhood (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971).

O’Fahey, R. S., ed., Arabic Literature of Africa, Vol. III: The Writings of the Muslim Peoples of Northeastern Africa (Leiden: Brill, 2003).

—, and John O. Hunwick, Arabic Literature of Africa (Leiden: Brill, 1994).

Oxford Business Group, The Report: Senegal 2009 (Oxford: OBG, 2009).

Roberts, Allen F., and Mary Nooter Roberts, A Saint in the City: Sufi Arts of Urban Senegal (Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 2003).

Robinson, David, Paths of Accommodation: Muslim Societies and the French Colonial Authorities in Senegal and Mauritania, 1880-1920 (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2000).

—, “The ‘Islamic Revolutions’ of West Africa on the Frontiers of the Islamic World”, February 2008, http://www.yale.edu/macmillan/rps/islam_papers/Robinson-030108.pdf

—, Muslim Societies in African History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014)

Schaffer, Matt, “‘Pakao Book’: Expansion and Social Structure by Virtue of an Indigenous Manuscript”, African Languages, 1 (1975), 96-115.

Scheele, Judith, “Coming to Terms with Tradition: Manuscript Conservation in Contemporary Algeria”, in The Trans-Saharan Book Trade: Manuscript Culture, Arabic Literacy and Intellectual History in Muslim Africa, ed. by Graziano Krätli and Ghislaine Lydon (Leiden: Brill, 2011), pp. 292-318.

Seesemann, Rüdiger, “‘The Shurafâ’ and the ‘Blacksmith’: The Role of the Idaw cAli of Mauritania in the Career of the Senegalese Ibrâhîm Niasse (1900-1975)”, in The Transmission of Learning in Islamic Africa, ed. by Scott S. Reese (Leiden: Brill, 2004), pp. 72-98.

Sharawy, Helmi, ed., Heritage of African Languages Manuscripts (Ajami), 1st edn. (Bamako: Institut Culturel Afro-Arabe, 2005).

Souag, Lameen, “Ajami in West Africa”, Afrikanistik Online, 2010, http://www.afrikanistik-aegyptologie-online.de/archiv/2010/2957

—, “Writing ‘Shelha’ in New Media: Emergent Non-Arabic Literacy in Southwestern Algeria”, in The Arabic Script in Africa: Studies in the Use of a Writing System, ed. by Meikal Mumin and Kees Versteegh (Leiden: Brill, 2014), pp. 91-94.

Sow, Alfâ Ibrâhîma, La Femme, la Vache, la Foi (Paris: Julliard Classiques Africains, 1966).

Sy, Habibou Rassoulou, Fonk sa Bopp di Wax li Nga Nàmp [Respect Yourself by Speaking your Mother Tongue] (Kaolack: [n. pub.], 1983).

Tamari, Tal, “Cinq Textes Bambara en Caractères Arabes: Présentation, Traduction, Analyse du Système Graphémique”, Islam et Société au Sud du Sahara, 8 (1994), 97-121.

—, and Dmitry Bondarev, eds., Journal of Qur’anic Studies: Qur’anic Exegesis in African Languages, 15/3 (London: Centre of Islamic Studies, School of Oriental and African Studies, 2013).

Vydrin, Valentin, “Ajami Script for Mande Languages”, in The Arabic Script in Africa: Studies in the Use of a Writing System, ed. by Meikal Mumin and Kees Versteegh (Leiden: Brill, 2014), pp. 119-224.

Warren-Rothlin, Andy, “West African Scripts and Arabic Orthographies”, in The Arabic Script in Africa: Studies in the Use of a Writing System, ed. by Meikal Mumin and Kees Versteegh (Leiden: Brill, 2014), pp. 261-88.

Zito, Alex, Prosperity and Purpose, Today and Tomorrow: Shaykh Ahmadu Bamba and Discourses of Work and Salvation in the Muridiyya Sufi Order of Senegal (Ph.D. thesis, Boston University, 2012).

Interviews by the author

Amdy Moustapha Seck, Dakar, Senegal, 12 June 2013.

Bassirou Kane, Khourou Mbacké, Senegal, 25 July 2011.

Cheikh Fall Kairé, Touba, Senegal, 24 July 2011.

Masokhna Lo, Diourbel, Senegal, 11 June 2011.

Mbaye Nguirane, Diourbel, Senegal, 11 June 2011.

Moustapha Diakhaté, Khourou Mbacké, Senegal, 25 July 2011.

Sam Niang, Touba, Senegal, 12 July 2014.

Africa’s Sources of Knowledge Digital Library, http://www.ask-dl.fas.harvard.edu/

African Online Digital Library, http://aodl.org/islamictolerance/ajami/scholars.php

Archives Nationales d’Outre Mer, Aix-en-Provence, France, Senegal, IV, 28a.

Archives Nationales d’Outre Mer, Aix-en-Provence, France, SG, SN, IV, 98b.

Archives Nationales d’Outre-Mer, Aix-en-Provence, France, FN, SG, SN, XVI, 1.

Archives Nationales d’Outre-Mer, Aix-en-Provence, France, Sen/IV/1.

EAP334: Digital Preservation of Wolof Ajami Manuscripts of Senegal, http://eap.bl.uk/database/results.a4d?projID=EAP334

Recited Ajami poems of Mbaye Diakhaté, http://www.jazbu.com/wolofal/

Recited Ajami poems of Mor Kairé, http://www.jazbu.com/mor_kayre/

Recited Ajami poems of Moussa Ka, http://www.jazbu.com/Serigne_Moussa_ka

Recited Ajami poems of Samba Diarra Mbaye, http://www.jazbu.com/sambadiarra/

WebFuuta, http://www.webfuuta.net/bibliotheque/alfa-ibrahim-sow/index.html

1 The transliteration of Arabic words in this chapter is based on the LOC transliteration system.