13. A charlatan’s album: cartes-de-visite from Bolivia, Argentina and Paraguay (1860-1880)

© Irina Podgorny, CC BY http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0052.13

In 1998, when we began to reorganise the historic archive of the Museum of La Plata in Argentina, manuscripts, letters and photographs all started to resurface from different departments of the institution. Missed, lost, misplaced, forgotten, discharged or withdrawn from everyday use, they had been rescued from the dustbin by diligent staff members. When the historic archive opened to the public, many of them realised that the memorabilia they had kept on the shelves and desk drawers of their offices could finally have a permanent home. They donated these remnants of past scientific practices to the archive, knowing they would now be kept for future generations.

Among the pieces donated was a relatively small collection of cartes-de-visite portraying Andean indigenous peoples and different individuals from Argentina, Bolivia and Paraguay.1 Héctor Díaz, a staff member from the museum’s Department of Physical Anthropology, had stored these cartes-de-visite for many years.2 He had saved them from being plundered or discarded, but he had not been able to collect any further information regarding their origins. In the words of the Egyptologist William Flinders Petrie, the cartes-de-visite arrived in the archive as mere “murdered evidence”, stripped of all the facts of grouping, locality and dating which would give them historical life and value.3

The photographs portray people from several cities and countries — such as Mendoza and Córdoba in Argentina and La Paz in Bolivia — but there is still no certainty as to when these images were taken or collected. When we first came across them, we did not know the name of the collector, nor even if there was a collector in the first place — we thought it possible that they had come together little by little, the result of a chain of contingencies. Some of the cards, however, carry inscriptions, such as the mark of Natalio Bernal, a Bolivian photographer who had established himself in La Paz by the 1860s.4 Other cards came from the studio of Clemente E. Corrège, a French photographer settled since the 1860s in Córdoba.5

Although we still cannot ascertain the identity of the collection’s creator, the cartes-de-visite offered us an additional and crucial clue to their origin, namely an inscription on the back of one of them that reads as follows: “Al Sr. Comendador Dr. Guido Bennati. Prueba de eterna Amistad — Vuestro amigo S. S. Bernabé Mendizábal [To Mr. Comendador Dr. Guido Bennati. As a sign of eternal friendship — Your friend, Bernabé Mendizábal]” (Fig. 13.1).6 The hint was not in the name of the Bolivian General Mendizábal, but in the addressee of the dedication. “Knight Commander” Guido Bennati (1827-1898) was an Italian charlatan and president of the so-called “Medical-Chirurgical Scientific Italian Commission”, a spurious commission of his own invention. From the late 1860s onwards, he travelled through South America with his different successive families, secretaries and associates, offering remedies and displaying his collections of natural history.7

Fig. 13.1 Carte-de-visite from Bernabé Mendizábal to Mr. Comendador Dr. Guido Bennati (EAP207/6/1, images 27 and 28), Public Domain.

Almost simultaneously, as part of another project,8 we discovered in the Biblioteca Nacional de la República Argentina (National Library of Argentina) two dusty, thin pamphlets. The first was published in 1876 in Cochabamba (Bolivia) and contains the “titles of honors, ranks, and diploma” that adorned the name of Guido Bennati. The second is the catalogue of Bennati’s Museo Científico Sudamericano (South American Scientific Museum). The catalogue displays samples from the three natural kingdoms — plants, animals and minerals — that were gathered by Bennati while travelling through the Argentine provinces, Paraguay, Brazil and Bolivia, and that were exhibited in Buenos Aires in 1883.9

The three sets of documents — the cartes-de-visite, the catalogue of Bennati’s museum and the collection of letters and certificates published in Cochabamba — indicate a common travel route shared by people, images and objects in a period lasting from the late 1860s to the early 1880s. At the time of our discovery, we knew that the Museum of La Plata had bought part of Bennati’s ethnographic and anthropological collection,10 transferred at an unknown time to Antonio Sampayo, the man who sold it to the museum.11 Once these disconnected traces and scattered pieces were put side by side, they revealed the itineraries of Bennati along the southern cone of the Americas, a travel route seemingly reflected in the places and people represented in the cartes-de-visite: from Buenos Aires to Mendoza, and from Mendoza to Córdoba, Entre Ríos, Corrientes, Asunción del Paraguay, Corumbá (Brazil), Santa Cruz de La Sierra, Cochabamba, Lake Titicaca and the ruins of Tiahuanaco, La Paz, Tarija, Salta, and then back to Buenos Aires (see Fig. 13.2). With all these elements in view, we developed the hypothesis that the cartes-de-visite are likely the remnants of Bennati’s album, collected, bought or received as a present on his South American travels.

1867: Córdoba, Rosario.

1869: Catamarca, Mendoza.

1870-71: Mendoza, San Juan, San Luis, and La Rioja, National Exhibition at Córdoba.

1872: Victoria (Entre Ríos).

1874: From Paso de los Libres, Alvear (Provincia de Corrientes), Villa Encarnación (Paraguay) Esteros del Iberá to Asunción.

1874-75: From Asunción, Paraguay to Corumbá, Brazil, and from there to Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia.

1875-77: From Santa Cruz to Cochabamba via the Piray River. From Cochabamba to Lake Titicaca up to La Paz, Sucre, Tarija,

1878-79: From Tarija to Jujuy, Salta, Rosario de Lerma, Cachi.

1882-83: From the Argentine NW to Buenos Aires.

Fig. 13.2 Itineraries of Guido Bennati in South America. Map by Samanta Faiad, Dept. Ilustración Científica del Museo de La Plata, CC BY.

Working from this hypothesis, our chapter focuses on the research that allowed us to bring back to life this collection of cartes-de-visite, digitised as part of EAP095 and EAP207, a pilot and a major project undertaken at the Museum of La Plata in the years 2006-2010.12 The first section is a short introduction to the history of the museum and its archive; the second is devoted to Bennati and his travels in South America. Bennati was not a photographer, but he gathered and displayed photographs in his travelling museum and during his medical performances. At the same time, other members of Bennati’s commission bought, resold and dispatched photographs from South America to the European illustrated journals.

Our contribution presents the network of itinerant characters who circulated objects, photographs and knowledge in South America in the 1860s and 1870s. Following the hints provided by the cartes-de-visite, the evidence found in other repositories (the local press in particular) and secondary texts on the history of photography in South America, this chapter aims to shed light on the role of travelling conmen, quacks and charlatans as agents of the circulation of knowledge. As such, the cartes-de-visite accumulated and collected by these agents tell us an important history that can be used as a model for interpreting the flow of images both in the region and on a global scale. At the same time, we want to contribute to the discussion of how historical researchers devoted to the rescue of endangered archives — such as those collected in this volume — can work together to make “murdered” evidence live and speak again.

The Museum of La Plata: collecting without archiving

The Museum of La Plata was established in 1884 as the general museum of La Plata, the new capital of the province of Buenos Aires, founded in 1882 after the federalisation in 1880 of the city of Buenos Aires, the former capital of the province. In 1906, the museum became one of the faculties of the recently established National University of La Plata. As such, it was turned into a school of natural sciences, where zoology, geology, botany, palaeontology, anthropology and archaeology were taught. The extant collections — fossil bones from Patagonia and the Pampas, mineral samples, human skulls and skeletons, dried animal skins, shells, butterflies and herbaria from Argentina, as well as archaeological pottery, moulages and art, maps and photographs — were transformed into materials for scientific training and pedagogical education.13

Fig. 13.3 Museo de La Plata, c. 1890

(Anales del Museo de La Plata, 1890), Public Domain.

These collections had been amassed — and continue to be gathered — through different strategies: expeditions organised by the museum, donations and purchases, the latter representing an important part of the acquisitions from the period.14 Collections began to accumulate in the basements and rooms of the monumental building, the first in South America specifically designed for that purpose (Fig. 13.3). As with many museums around the world, the expansion of the collections was not accompanied by the inventory or study of the objects being incorporated.15 In La Plata, the task of inventory was assigned to the designated “jefes de sección” (chiefs of section), namely the scientists in charge of the different scientific departments of the museum, who preferred to use their time to work on research and publications rather than on keeping records, filing or preparing lists displaying the museum’s accessions.16

The lack of specific administrative staff and the absence of a real budget for the completion of the inventory resulted in the accumulation of things in the repositories and in an incomplete record of both entries and withdrawals. While some departments kept their own records, others did not, depending on the goodwill and interest of officials and the relative independence of each scientific department vis-à-vis the regulations that supposedly ruled the whole institution.17 There was never a single inventory, and no one could assess how many, or which, items the museum actually had and how they were being handled by the staff. However, the museum, as a public office, had to report to its superiors in the Ministerio de Obras Públicas (Ministry of Public Works) of the Province of Buenos Aires, and, starting in 1906, to the Presidency of the National University. For the sake of administration, the Director’s office included a secretary who took care of paperwork, kept the administrative files and recorded the incoming and outgoing correspondence, as all administrative public offices were supposed to do.18 Far from a historic repository, this was a living archive used for institutional administration and management. These papers represent the main collections stored today in the historic archive of the museum.

It was only in 1937 that a memorandum established another kind of archive: a photographic archive to protect the extant photographic materials and to illustrate the museum’s collection. All photographic materials — the ones that already existed and the ones that would be produced in the future — were transferred to the new archive along with information that would help in identifying and classifying the images. The archive, located in a photographic lab created in the late 1880s, had to be organised following the names of the scientific sections that, in fact, reflected neither the historic situation nor the disciplinary boundaries of the late nineteenth century, but rather the scientific organisational chart of the museum in the late 1930s. Thus, the historical photographs that were incorporated into the archive were “reclassified” according to the new disciplinary sections created in those years. In this way, both original order and provenance were lost.19

Furthermore, the transfer of photographic collections from the scientific departments to the archive had not been recorded, and there are no documented traces of the implementation of the 1937 memorandum. However, it is clear that, again, the guidelines were only partially followed: whereas many scientific departments deposited their plate negatives in the new archive, others continue to store photographs and negatives following the organisational chart of the museum’s foundational years.20 These images were never given to the archive, which in fact continued to function as a photographic lab rather than as a historical repository. Thus the archive continued to produce photographs for the researchers working in the museum, but it did not comply with the procedures set in 1937.

In one of these back and forths of papers, memoranda and collections, the cartes-de-visite purchased or presented at and unspecficied date became invisible to curators and officials. Along with many other objects, they started their life as murdered evidence of forgotten facts and events.

One of the administrative files records the purchase of Guido Bennati’s collection. The administrator of the Department of Anthropology noted in the early twentieth century that the collections he curated included 44 skulls from Bolivia, donated in June 1903 by a certain Señor Zavala, the holder of Bennati’s collection.21 By 1910, in fact, the Department of Anthropology had recorded the existence of skulls, skeletons and a dried foetus, collected in Bolivia in 1878 and 1879 and purchased from Bennati, the good friend of the Bolivian General Bernabé Mendizábal, in the early years of the museum. Most probably, this transaction included the collection of cartes-de-visite, which — together with the skeletons — arrived at the department around 1887.

The travels of Guido Bennati as reflected by the cartes-de-visite

Bennati was apparently born in Pisa in 1827. He worked in the fairs and public markets of the Italian provinces and France, where he presented himself as a “Knight Commander” of the Asiatic Order of Universal Morality, a circle of practitioners of animal magnetism established in Paris in the 1830s. Bennati, a professional quack, arrived at the fairs with a parade of horses, musicians and artists, offering miraculous cures for free and for the welfare of suffering humanity. In 1865, Bennati and his associate, an old French physician, were condemned and sued in Lille for dealing in sham remedies.22

We do not know why Bennati came to South America, but his first traces on the other side of the Atlantic date from the late 1860s, when he began travelling in those regions with his successive families, his faux remedies and his collections of natural history.23 Once in South America, he honoured himself with the presidency of the so-called “Medico-Chirurgical Scientific Italian Commission”, an association of his own invention that included a secretary, a physician, and several helpers and servants. With this “Commission” he journeyed through Argentina, Paraguay and Bolivia, pretending to be a travelling naturalist sent by Italy to collect data and artefacts and to promote the natural wealth and potential of South America among European investors. Thus, in the Americas, he substituted the “museum of natural history” for the fair spectacle as a means to attract customers for his curative powers.

Bennati arrived in Argentina when the first National Exhibition of industrial and natural products was being organised in the city of Córdoba. Given that he was acting as travelling doctor and naturalist, several provincial governments — such as the government of the province of Mendoza — commissioned him to collect samples from the local environment and to attend, as their representative, the Exhibition in 1870. On this occasion, he — or his secretaries — wrote reports, kept detailed records of the number of people healed on his travels and gave speeches in Italian on the subject of progress. He was applauded by an audience of educated gentlemen who, although they might not have understood a single word of what he said, eagerly greeted the enthusiasm Bennati displayed for the future of the country.24 Most probably, the experience of the Exhibition and the instructions given by the organisers regarding what and how to collect, taught him which kinds of objects were most valued by governments and politicians.

The collection of cartes-de-visite contains a hint as to Bennati’s relationship with the people he met in the province of Mendoza and at the National Exhibition in Córdoba: the portraits of Michel-Aimé Pouget, a French agronomist hired in 1853 to manage the agriculture school in Mendoza. Pouget is best known today for his role in introducing the vines and seeds of Malbec to Argentina, a grape of French origin that was once predominant in Bordeaux and Cahors. In 1870, he and his wife, Petrona Sosa de Pouget, were exhibiting in Córdoba many of their economic initiatives, such as their experiments in apiculture and their cultivation and production of vegetal fibres and tissues (Fig. 13.4).25

Fig. 13.4 Carte-de-visite from Michel-Aimé Pouget

(EAP207/6/1, images 29 and 30), Public Domain.

Bennati, aware of the interest in these initiatives, collected fibres that could be employed as raw materials for several industries, also exhibiting vegetal products in Córdoba and in other places he visited. At the same time, he collected the portraits of people who shared his interests, as evidence of their collegial friendship. In doing so, he was following a fashion that had spread throughout the Americas and Europe: collecting cartes-de-visite, as it is well established, became an obsession in the second half of the nineteenth century.26 As Douglas Keith McElroy has noted:

These humble images dominated the economics of photography and social intercourse […] Every home became a photographic gallery with luxurious albums filled with cartes, and these reflected the society and its values better than any other art of the period. Standardization created a democratic imagery throughout the world […] The small card was exploited not only for portraiture but also as a vehicle to transport the collector to famous places, to document disasters, and to promote business.27

In our case, the cards travelled with the collector and promoted the business of science and quackery. Bennati, as was common among travelling dentists, surgeons and photographers at that time, announced his Commission’s arrival in the cities it visited in the newspapers, promoting the services and gifts it offered to the local population and government. Thus, in Paraguay in 1875, he presented fragments of the skeleton of Megatherium that had been discovered in the surroundings of the city of Asunción; the remains of this formidable fossil mammal had been considered an icon of prehistoric South America for decades.28 In January 1875, President Juan Bautista Gill accepted it as a gift with the intention of creating Paraguay’s national museum — although this museum was never in fact inaugurated.29

It is probable that when Bennati brought his advertisement to the newspaper, he met its editor, the French journalist Joseph Charles Manó, and discovered that they shared common strategies and interests.30 Bennati invited Manó to join an expedition, covering his travel expenses. Manó, in exchange, would record geological and botanical observations.31 Together they navigated the Upper Paraguay River up to the Brazilian fluvial port of Corumbá, a gateway to Mato Grosso and the Amazon basin which, with the opening of the Paraguay River after the Paraguayan War of 1864-1870, had become strategically important for international trade. Manó and Bennati travelled and, at the same time, encountered a network of itinerant individuals: exiles, émigrés, disappointed European politicians, anarchists, republicans, revolutionaries, adventurers or simply pretenders who travelled throughout the continent, trying to survive by selling their skills to those who were willing to pay for them. The press, writing, and the supposedly neutral rhetoric of science, nature and progress represented the tools that assured their survival in the New World. During their stay in Paraguay, the Commission collected fossils as well as ethnographic objects, such as calabash gourds for drinking mate, bowls, arrows and bows.32

From Paraguay, the collection of cartes-de-visite includes a portrait of Juan Vicente Estigarribia, the personal physician of the Paraguayan “Dictador Supremo” Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia and, later, of the López family, also rulers of Paraguay from the 1840s to the 1860s.33 Although Bennati did not meet Estigarribia (who died in 1869), they share certain connections which may explain the presence of his portrait in the collection (assuming that it is Bennati’s album): Estigarribia, like Bennati, was described as a naturalist by historians and contemporaries, and he was also a doctor interested both in botany and the uses of plants in medicine.34 Objects bring dead and living people together, and Bennati, in collecting Estagarribia’s portrait, perhaps wanted to be associated with one of the most important physicians of the countries he visited.

Bennati’s Commission arrived in Santa Cruz de la Sierra in 1875, and subsequently continued to other Bolivian cities — Cochabamba, La Paz, Sucre, Potosí and Tarija.35 In every single city they visited, they were involved in conflicts with different local actors who sought to demonstrate that the Commission was a fraud and that none of its members were actually what they pretended to be.36 Despite these allegations, members of Bennati’s commission moved freely in the cities’ scientific and literary circles. They were accepted and welcomed by several members of the various political factions and certain members of the Catholic clergy, who dispensed honours to them, supported their initiatives in the fields of public health and science, and gave tokens of their friendship, such as General Bernabé’s carte-de-visite dedicated to Bennati.

The Commission exhibited its collections in Santa Cruz de la Sierra and undertook excursions to the Inca ruins nearby as a means of proving their interest in the local environment and culture. In Santa Cruz, the Commission produced two publications, Relación del Viaje de la Comisión Científica Médico-Quirúrgica Italiana por el norte del Gran Chaco y el Sud de la Provincia de Chiquitos and El Naturalismo positivo en la Medicina (1875); and in Cochabamba they published Compendio de los trabajos ejecutados en este trayecto and Diplomas i documentos de honor de Europa y América que adornan el nombre del ilustre comendador Dr. Guido Bennati (1876).37 While Diplomas i documentos is a transcription of testimonies made by witnesses to Bennati’s degrees as a doctor of medicine, the second and the fourth of these volumes were travel descriptions, and the third a compendium of ideas on the most modern methods in medicine. These publications described what the members of the Commission encountered on their travels: fauna, flora, mineral resources, ruins and natives. They also proposed a plan of action for the local government and elite on how to improve their economic situation by means of new roads and encouraging industry and commerce. Probably written by Manó, an expert in the art of propaganda, these pamphlets were printed on low-quality paper, with a very dense typography, in the printing offices of the newspapers in which they worked or in those owned by their protectors.38

In November 1876, the Commission arrived in La Paz, allegedly after having completed “The scientific study of the material resulting from their travels with regards to Hygiene, Climatology, Botany, Mineralogy, Geology, Zoology, Industry and Commerce of the Argentinian, Paraguayan and Oriental Republics”.39 They wanted to “publish the most exact work on its Ethnography and the systems of mountains and rivers, questions absolutely related to the problem of Hygiene”. They promised to publish a “Descriptive History of the Republic of Bolivia”, imitating the propagandistically-minded publications advertising their natural resources that had allowed other Spanish American countries to successfully attract European migration. This work would be integrated in three quarto volumes of more than 400 pages. They were in fact calling for a subscription and also for the provision of data, information and objects.40

In La Paz, the Commission installed its offices and museum in a house located in the main square of the city. While the cabinet of Doctor Bennati opened from 7am to 11am, the museum opened from 1pm to 4pm, displaying curiosities and representing the diversity and richness of the nature and arts of South America.41 The museum was a means to exhibit the commission’s collection but also to enrich it further: Bennati and company offered monetary compensation for plants, fruits, fossils, petrifactions, furniture, books in all languages or in Spanish from the age of the conquistadors, animals, minerals, artefacts, and everything related to the arts and nature of these regions.42

The museum was indeed the centre of a medical-commercial enterprise. Healing was performed in the space of the museum, which, at the same time, exhibited the local medical and industrial products Bennati and his companions had collected on their travels. The museum attracted not only potential patients to the medical cabinet but also artefacts, photographs and books to be resold on a market that would deliver these objects to other places and people. In doing so, the museum also allowed Bennati and his circle to procure documents, materials and exemplars of writing about the topics they had supposedly investigated in the field. In other cities visited by Bennati, the newspapers published extensive descriptions of the interior of his cabinet: the walls were covered by photographs showing the patients before and after being treated by Bennati. The photograph of a “blind invalid man” is possibly the only item remaining from this series.43

None of the members of the so-called Commission was a photographer. The cartes-de-visite provide a clue as to how they obtained these pictures: they were purchased at the studio of Natalio Bernal, a Bolivian photographer, settled in La Paz since the 1860s. As several historians of photography in South America have remarked, it was a time when travelling photographers made their living portraying people both alive and dead and creating “typical characters”, such as the types exhibited in the Bolivian cartes-de-visite.44 Objects of collection, exchange and trade, the photographs were purchased by locals and visitors alike. Travelling naturalists, as well as itinerant photographers, multiplied the destinies of these images. As we will see in the following section, some images — not kept in the Museum of La Plata, so we do not know whether they were purchased or stolen — reveal the intricate path of photographs as they were collected and traded, and the difficulties of uncovering their complex histories.

The ruins of Tiahuanaco and the Bennati Museum

In November 1876, the newspaper La Reforma of La Paz published an account of a four-month excursion made by Bennati’s Italian Commission to Lake Titicaca and the ruins of Tiahuanaco. The members of the Commission were obliged, they said, to the Bolivian government for “the help and support given to science”, as well as to local authorities in the Titicaca regions, including the priest of the parish of Tiahuanaco and the officials from the Peruvian side of the lake. The craniological and archaeological observations from these explorations demonstrated “that Tiahuanaco had been the cradle and centre of origin of the civilisation of the Americas, which irradiated from the shores of the Titicaca to all the continent”.45

In a tomb opened by a previous excavation, the commission noted the co-existence of two different human types among the skulls: one more advanced and similar to the pre-Aztec skulls; the second representing a lower race, probably enslaved by the first and similar to the skulls of the higher families of apes. In 1878, Paul Broca analysed three skulls sent to the School of Anthropology in Paris by Théodore Ber, another French traveller who was in Tiahuanaco at the same time as the Italian Commission.46 Like the Commission, Broca classified the skulls as belonging to two different human types.47

In the meantime, in La Paz, Manó broke with Bennati and returned to journalism. In March 1877, Manó began an association with Eloy Perillán y Buxó, a Spanish anarchist, anti-monarchist and director of the newspaper El Inca. Perillán y Buxó had had to leave Spain and go into exile in 1874 due to his provocative writings, time he spent travelling in South America.48 Like Bennati and Manó, Perillán y Buxó both mocked and profited from the tastes, pretensions and consumption habits of the petite bourgeoisie of Europe and the Americas. All three men were aware of the importance that government officials and the urban bourgeoisie attached to academic titles, collections and scientific rhetoric. Throughout their travels, the men endeavoured to publish records, inaugurate museums and affirm their own scientific expertise. They also sought to establish newspapers and offer their services to the political factions of the troubled South American republics.

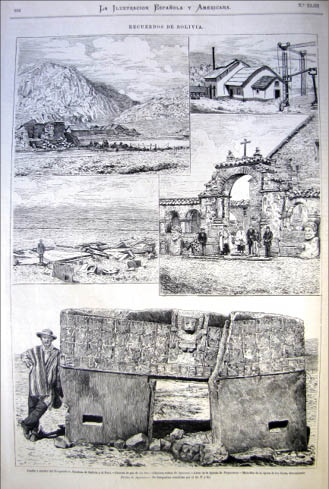

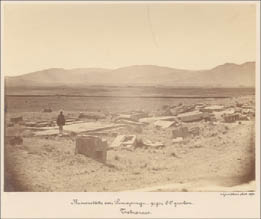

Manó and Perillán y Buxó issued a new periodical, El Ferrocarril [The Railroad],49 and in March 1877 they announced that they were collecting archaeological pieces to be dispatched and published in La Ilustración Española y Americana, an illustrated journal in Madrid.50 Offering to pay for remittances, they obtained “mummies, Incan pottery, medals, arrows, photographs of ruins and Indian types, idols”.51 On 22 November 1877, La Ilustración published “an engraving with five peculiar views of the Bolivian Republic, based on direct photographs sent by an old correspondent of our periodical”. These “souvenirs of Bolivia”, sent by “Mr. P. y B”, showed several vistas, one of them probably portraying the visit of Bennati’s commission to the ruins and village of Tiahuanaco (Fig. 13.5).

Fig. 13.5 “Souvenirs of Bolivia” (from La Ilustración Española y Americana, 43 (November 22, 1877), p. 316). © CSIC, Centro de Ciencias Humanas y Sociales, Biblioteca Tomás Navarro Tomás, all rights reserved.

In fact, these vistas had been taken by the travelling German photographer Georges B. von Grumbkow who, late in 1876, was hired by the aforementioned Théodore Ber to take photographs of the ruins — photos that Ber wanted to send to France as part of his role as Commissioner of the French Government for collecting American antiquities.52 However, Grumbkow, once he took the pictures, sold them to the many customers interested in this kind of material. In 1876-77 Tiawanaku received visits not only from Ber and Bennati’s Commission, but also from the German geologists Alphons Stübel and Wilhelm Reiss. These two men visited the ruins and purchased a set of the photographs taken by Grumbkow, now stored in the Leibniz Institut für Landeskunde (IFL) in Leipzig (Figs. 13.6 and 13.7).53

Fig. 13.6 “The Ruins of Pumapungu”, view to the southwest. © Stübel’s Collections, Leibniz-Institut für Länderkunde, Leipzig, all rights reserved.

Fig. 13.7 “The church of Tiahuanaco”. © Stübel’s Collections, Leibniz-Institut für Länderkunde, Leipzig, all rights reserved.

Less than a year after they were taken, these photographs had travelled far beyond the Andes: dispatched by this dynamic world of itinerant people composed of charlatans, journalists, travellers and photographers, they were soon incorporated into the visual universe of South American archaeology, which was emerging in the same years and through the same agents.

Even though until now we have found no trace of Grumbkow’s photographs either in La Plata or in Buenos Aires, textual evidence suggests that they were exhibited in Buenos Aires in 1883, when Bennati presented his collection in the Argentinian capital. The local newspapers celebrated his collections, reporting and describing them in detail. Bennati’s museum contained the enormous carapaces of mastodons, mylodons and glyptodonts, in addition to fossils, bones, teeth, petrified plants and fruits, mineral collections, precious stones, objects from different tribes and from the Bronze Age, musical instruments, dried skins, human skeletons, skulls, mummies, weapons, jewels, seeds, textiles, pottery, bowls, jars, idols, apparel, baskets, feathers, petrified human eyes, vistas, photographs of Indians domesticated by Bennati, landscapes of primitive cities, etc.54 The collection also included the same cartes-de-visite that — as we argue in this paper — came to the Museum of La Plata a couple of years later. As the catalogue states:

To complement this Group (various), we display a large and diverse collection of vistas representing places, buildings, ruins, etc., among which the ruins of the ancient town of Tiaguanacu, with its gigantic monoliths, stand out. This collection is supplemented by the native attire of nearly all the countries visited.55

This excerpt probably refers to the photographs sold by Natalio Bernal in La Paz, Bolivia — examples of trade and type photographs that, as McElroy has said, “usually represented professions and socioeconomic roles typical or distinctive to a given local culture”.56 These types or roles, McElroy suggests, were often posed or dramatised in the studio rather than taken from life. Carte-de-visite portraits of Indians are numerous and most often fall within the costumbrista tradition of recording distinctive costumes and activities associated with native culture rather than capturing portraits of individuals.57

But it was the photographs that we suppose to be Grumbkow’s that attracted the attention of most reporters and visitors to Bennati’s exhibition as the clearest evidence of the antiquity of the civilisations of the New World.58 Thus, the Buenos Aires press described what they “saw” in the photographs:

Tiahuanaco, this portentous city, with its colossal ruins connects us with the primitive continent, it is very close, in the North of the Republic.

What do these tremendous ruins tell us?

A vanished race, a missing civilisation and a missing history, what was left?

Let’s observe the photographs displayed at Museo Bennati and let’s compare the facts. Huge monoliths, eight metres high and four wide, had been reshaped by the elapsing of time and the action of wind and rain, to become thin needles, just a metre high and eroded on their top.

The palaces, the temples, the circuses and the megalithic masonry keep, however, their mightiness. There one can observe how the monoliths were used, as well as the arts, crafts and power of those thousands of men that had erected them.

Carving, transporting them to a place where there were no mountains, building a city around an “artificial hill”, where the temple of the Sun was located; having this enormous city destroyed, forgetting that this cyclopean city had ever existed, having the wind modelling its monoliths … many centuries, hélas, many centuries must have gone by!

Tiahuanaco! Up there we have its colossal ruins, whose dimensions —as well as those from Palenque — would scare any Londoner.

The Islands of the Sun and the Moon, the temple of the virgins, they lay over thousands of shells left in the mountains by the ancient Titicaca lake with a former circumference of 2650 leagues, today reduced to 52 length and 33 width!

Tiahuanaco, despite all the heresies committed against her, such as the new temple built with her stones, recalls to us the sorrow already caused by the Coliseum “quod non fecerunt barbaros fecir Barberini”, and exhibits one of the oldest civilisations from the Americas.

Is that all?

No! We have photographs in front of us that reveal something still more spectacular.

Bennati dug at Tiahuanaca, searching the tombs of those ancient beings.

Did he find them?

Six metres below Tiahuanaca, under a triple layer of topsoil, clay and sand, he found the vestiges of an older city, with great monuments, superb monoliths, mighty buildings, still more powerful than those from modern Tiahuanaca or Tiahuanacú (the reconstruction of the name is still uncertain). The excavation was not very extensive, the city but partially revealed; however it is enough to confirm its existence, as well as the existence of its monuments, as seen and photographed by Bennati.

When Bennati presented his collections in Buenos Aires, the Museum of La Plata did not exist and the objects that his museum exhibited had never been seen before in South America. The unknown reporter finished his chronicle by strongly encouraging the Argentinian government to purchase Bennati’s collection for Argentinian public institutions, which indeed they did in the years to follow. In this way, a collection that was amassed to accompany a quack doctor’s cabinet became part of the Museum of La Plata. Some of the objects were put on display, while others, such as the cartes-de-visite, were put aside, treated as worthless and, finally, forgotten. However, all of them originated at the crossroads of itinerant people moving through the Americas and carrying with them things, ideas and different devices: photo machines, photographs, collections, newspaper articles and travelling museums.

Manó and Bennati’s travels were propelled by the conflicts in which they were involved, even though they would describe their frequent departures as preconceived plans to survey the natural resources of the places they visited. Bennati represents one of the many itinerant characters — travelling dentists, photographers, journalists, magicians, circus artists, and impresarios of popular anatomical museums — journeying through the Americas, from town to town, from country to country, from one side of the Atlantic to the other, from north to south, from east to west. Historians still have to learn how to deal with the history of travelling people; their traces are elusive to national and institutional histories. The charlatans and photographers did not tend to keep written records, and they were continually on the move. They carried news, propagated modes, discourses and objects, and then disappeared from the scene. However, their traces are there: forgotten, misplaced, almost invisible. So were the cartes-de-visite in the Museum of La Plata, the gateway — among many others — that we have chosen to cross the barrier of South American historiographies and enter into the world of travelling charlatans.59

References

Anonymous, Cartes de Visite (Tarjetas de Visita) Retratos y fotografías en el Siglo XIX, Guía de Exposición (Cochabamba: Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas y Museo Arqueológico, UMSS, 2013).

Bennati, Guido, Diplomas i documentos de Europa y América que adornan el nombre del Ilustre Comendador Dr. Guido Bennati, publicación hecha para satisfacer victoriosamente a los que quieren negar la existencia de ellos (Cochabamba: Gutiérrez, 1876).

—, Museo Científico Sud-Americano de Arqueolojía, Antropolojía, Paleontolojía y en general de todo lo concerniente a los tres reinos de la naturaleza (Buenos Aires: La Famiglia Italiana, 1883).

Bischoff, Efraín, “Fotógrafos de Córdoba”, in Memorias del Primer Congreso de Historia de la Fotografía (Vicente López, Provincia de Buenos Aires) (Buenos Aires: Mundo Técnico, 1992), pp. 111-15.

Boixadós, María Cristina, Córdoba fotografiada entre 1870 y 1930: Imágenes Urbanas (Córdoba: Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, 2008).

Broca, Paul, “Sur des crânes et des objets d’industrie provenant des fouilles de M. Ber à Tiahuanaco (Perou)”, Bulletins de la Société d’Anthropologie de Paris, 3/1 (1878), 230-35.

Buck, Daniel, “Pioneer Photography in Bolivia: Directory of Daguerreotypists and Photographers, 1840s-1930s”, Bolivian Studies, 5/1 (1994-1995), 97-128.

Draghi Lucero, Juan, Miguel Amable Pouget y su obra (Mendoza: Junta de Estudios Históricos, 1936).

Farro, Máximo, La formación del Museo de La Plata: Coleccionistas, comerciantes, estudiosos y naturalistas viajeros a fines del siglo XIX (Rosario: Prohistoria, 2009).

Forster, Babett, Fotografien als Sammlungsobjekte im 19. Jahrhundert: Die Alphons-Stübel-Sammlung früher Orientfotografie (Weimar: VDG, 2013).

García, Susana V., Enseñanza científica y cultura académica: La Universidad de La Plata y las ciencias naturales (1900-1930) (Rosario: Prohistoria, 2010).

—, “Ficheros, muebles, registros, legajos: La organización de los archivos y de la información en las primeras décadas del siglo XX”, in Los secretos de Barba Azul: Fantasías y realidades de los Archivos del Museo de La Plata, ed. by Tatiana Kelly and I. Podgorny (Rosario: Prohistoria, 2011), pp. 41-65.

Gómez, Juan, La Fotografía en la Argentina, su historia y evolución en el siglo XIX 1840-1899 (Buenos Aires: Abadía, 1986).

Gómez Aparicio, Pedro, Historia del periodismo español: De la Revolución de Septiembre al desastre colonial (Madrid: Editora Nacional, 1971).

González Echevarría, Roberto, “The Dictatorship of Rhetoric/The Rhetoric of Dictatorship: Carpentier, García Márquez, and Roa Bastos”, Latin American Research Review, 15/3 (1980), 205-28.

—, The Voice of the Masters: Writing and Authority in Modern Latin American Literature (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1985).

González Torres, Dionisio M., Boticas de la colonia y cosecha de hojas dispersas (Asunción: Instituto Colorado de Cultura, 1978).

Kelly, Tatiana, and I. Podgorny, eds., Los secretos de Barba Azul: Fantasías y realidades de los Archivos del Museo de La Plata (Rosario: Prohistoria, 2011).

Lehmann-Nitsche, Roberto, Catálogo de la Sección Antropología del Museo de La Plata (La Plata: Museo de La Plata, 1910).

Majluf, Natalia, Registros del territorio: las primeras décadas de la fotografía, 1860-1880 (Lima: Museo de Arte de Lima, 1997).

McElroy, Douglas Keith, The History of Photography in Peru in the Nineteenth Century, 1839-1876 (Ph.D. thesis, University of New Mexico, 1977).

—, Early Peruvian Photography: A Critical Case Study (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Research Press, 1985).

Monguió, Luis, “Una desconocida novela hispano-peruana sobre la Guerra del Pacífico”, Revista Hispánica Moderna, 35/3 (1969), 248-54.

Penny, H. Glenn, Objects of Culture: Ethnology and Ethnographic Museums in Imperial Germany (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2002).

Pérez Acosta, Juan Francisco, Carlos Antonio López, obrero máximo, labor administrativa y constructiva (Asunción: Guarania, 1948).

Petrie, William Flinders, “A National Repository for Science and Art”, Royal Society of Arts Journal, 48 (1899-1900), 525-33.

—, Methods and Aims in Archaeology (London: Macmillan, 1904).

Podgorny, Irina, “Robert Lehmann-Nitsche”, in New Dictionary of Scientific Biography 4, ed. by N. Koertge (Detroit, MI: Scribner, 2007), pp. 236-38.

—, “La prueba asesinada: El trabajo de campo y los métodos de registro en la arqueología de los inicios del siglo XX”, in Saberes locales, ensayos sobre historia de la ciencia en América Latina, ed. by Frida Gorbach and Carlos López Beltrán (Zamora: El Colegio de Michoacán, 2008), pp. 169-205.

—, “Momias que hablan: Ciencia, colección y experiencias con la vida y la muerte en la década de 1880”, Prismas: Revista de Historia Intelectual, 12 (2008), 49-65.

—, “La industria y laboriosidad de la República: Guido Bennati y las muestras de San Luis, Mendoza y La Rioja en la Exposición Nacional de Córdoba”, in Argentina en exposición: Ferias y exhibiciones durante los siglos XIX y XX, ed. by Andrea Lluch and Silvia Di Liscia (Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 2009), pp. 21-59.

—, El sendero del tiempo y de las causas accidentales. Los espacios de la prehistoria en la Argentina, 1850-1910 (Rosario: Prohistoria, 2009).

—, “Coleccionistas de Arena: La comisión médico — quirúrgica Italiana en el Altiplano Boliviano (1875-1877)”, Antípoda, 11 (2010), 165-88.

—, Los viajes en Bolivia de la Comisión Científica Médico-Quirúrgica Italiana (Santa Cruz de la Sierra: Fundación Nova, 2011).

—, Un repositorio nacional para la ciencia y el arte (Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2012).

—, “Travelling Museums and Itinerant Collections in Nineteenth-Century Latin America”, Museum History Journal, 6 (2013), 127-46.

—, “Fossil Dealers, the Practices of Comparative Anatomy and British Diplomacy in Latin America”, The British Journal for the History of Science, 46/4 (2013), 647-74.

—, “From Lake Titicaca to Guatemala: The Travels of Joseph Charles Manó and His Wife of Unknown Name”, in Nature and Antiquities: The Making of Archaeology in the Americas, ed. by Philip Kohl, I. Podgorny and Stefanie Gänger (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 2014), pp. 125-44.

—, and Maria Margaret Lopes, El Desierto en una Vitrina: Museos e historia natural en la Argentina, 1810-1890 (Mexico City: Limusa, 2008).

—, and Tatiana Kelly, “Faces Drawn in the Sand: A Rescue Project of Native Peoples’ Photographs Stored at the Museum of La Plata, Argentina”, MIR, 39 (2010), 98-113.

Riviale, Pascal, Los viajeros franceses en busca del Perú Antiguo, 1821-1914 (Lima: IFEA, 2000).

—, and Christophe Galinon, Une vie dans les Andes: Le Journal de Théodore Ber, 1864-1896 (Paris: Ginkgo, 2013).

Rudwick, Martin J. S., Scenes From the Deep Times: Early Pictorial Representations of the Prehistoric World (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1992).

Sampayo, Antonio, Objetos del Museo (Buenos Aires: La Nazione Italiana, 1886).

Torrico Landa, Gustavo, and Cristóbal Kolkichuima P’ankara, La imprenta y el periodismo en Bolivia (La Paz: Fondo Ed. de los Diputados, 2004).

Wichard, Robin, and Carol Wichard, Victorian Cartes-de-Visite (Princes Risborough: Shire, 1999).

1 EAP207/6: “Museo de La Plata, Archivo Histórico y Fotográfico, Colección Cartes de visite [c. 1860-1880]”— 42 documents (a small album of photographic prints mounted on cards 2.5 by 4 inches), comprising full length and torso studio photographic portraits of Andean indigenous peoples and persons of European origin from Argentina, Bolivia and Paraguay, http://eap.bl.uk/database/overview_item.a4d?catId=157500;r=9040

2 As we discuss below, the Department of Physical Anthropology was the final destination of Guido Bennati’s anthropological collections. If the cartes-de-visite were part of an album collected by this Italian charlatan, it is not surprising that they were kept together, or at least held in the same department.

3 William Flinders Petrie, Methods and Aims in Archaeology (London: Macmillan, 1904), p. 48; see also Irina Podgorny, “La prueba asesinada: El trabajo de campo y los métodos de registro en la arqueología de los inicios del siglo XX”, in Saberes locales, ensayos sobre historia de la ciencia en América Latina, ed. by Frida Gorbach and Carlos López Beltrán (Zamora: El Colegio de Michoacán, 2008), pp. 169-205.

4 Daniel Buck, “Pioneer Photography in Bolivia: Directory of Daguerreotypists and Photographers, 1840s-1930s”, Bolivian Studies, 5/1 (1994-1995), p. 10; see also Anonymous, Cartes de Visite (Tarjetas de Visita) Retratos y fotografías en el Siglo XIX, Guía de Exposición (Cochabamba: Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas y Museo Arqueológico, UMSS, 2013), pp. 6 and 16.

5 Efraín Bischoff, “Fotógrafos de Córdoba”, in Memorias del Primer Congreso de Historia de la Fotografía (Vicente López, Provincia de Buenos Aires) (Buenos Aires: Mundo Técnico, 1992), pp. 111-15 (p. 112); Juan Gómez, La Fotografía en la Argentina, su historia y evolución en el siglo XIX 1840-1899 (Buenos Aires: Abadía, 1986), p. 86; and María Cristina Boixadós, Córdoba fotografiada entre 1870 y 1930: Imágenes Urbanas (Córdoba: Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, 2008), pp. 26-27. I am indebted to Roberto Ferrari for this information.

6 EAP207/6/1.

7 On the identification and listing of the collection, see http://eap.bl.uk/database/overview_item.a4d?catId=157500;r=9040, authored by Máximo Farro, Susana García and Alejandro Martínez (accessed 16 October 2014). The latter identified Bennati as the “creator” of this collection. On Bennati, see Irina Podgorny, “Momias que hablan: Ciencia, colección y experiencias con la vida y la muerte en la década de 1880”, Prismas: Revista de Historia Intelectual, 12 (2008), 49-65; and idem, Los viajes en Bolivia de la Comisión Científica Médico-Quirúrgica Italiana (Santa Cruz de la Sierra: Fundación Nova, 2011).

8 In 2007, on a Félix de Azara fellowship awarded by the National Library of Argentina, I explored collections of South American pamphlets and journals to track the Argentinian itineraries of Bennati, discovering that he and his companions were visible mostly through the press. I have continued this research in a collective and cooperative way by visiting archives and libraries; by requesting material through the ILL service from the MPI-WG and the collegial goodwill of colleagues; by travelling or working in the places Bennati or his secretaries visited on their trips. Up to now, I have gathered materials and notes published in the press from Mendoza, Salta, Corrientes, Asunción del Paraguay, Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Sucre, La Paz, Bogotá and Cali; articles from Colombia, Bolivia, and Guatemala; and manuscripts and letters stored at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BNF). The compiled materials give a comprehensive view of the continental scope of the travels of Bennati and other itinerant charlatans.

9 Guido Bennati, Museo Científico Sud-Americano de Arqueolojía, Antropolojía, Paleontolojía y en general de todo lo concerniente a los tres reinos de la naturaleza (Buenos Aires: La Famiglia Italiana, 1883); and idem, Diplomas i documentos de Europa y América que adornan el nombre del Ilustre Comendador Dr. Guido Bennati, publicación hecha para satisfacer victoriosamente a los que quieren negar la existencia de ellos (Cochabamba: Gutiérrez, 1876).

10 Máximo Farro, La formación del Museo de La Plata. Coleccionistas, comerciantes, estudiosos y naturalistas viajeros a fines del siglo XIX (Rosario: Prohistoria, 2009), pp. 102-03; on the museum, see also Irina Podgorny and Maria Margaret Lopes, El Desierto en una Vitrina: Museos e historia natural en la Argentina, 1810-1890 (Mexico City: Limusa, 2008).

11 Roberto Lehmann-Nitsche, Catálogo de la Sección Antropología del Museo de La Plata (La Plata: Museo de La Plata, 1910), pp. 64-65, 90-91 and 112; and Antonio Sampayo, Objetos del Museo (Buenos Aires: La Nazione Italiana, 1886). See also Irina Podgorny, “Robert Lehmann-Nitsche”, in New Dictionary of Scientific Biography 4, ed. by N. Koertge (Detroit, MI: Scribner, 2007), pp. 236-38. In November 1885, Bennati also sold thirteen boxes of fossils to the museum. See Farro, p. 103.

12 On this project, see Tatiana Kelly and I. Podgorny, eds., Los secretos de Barba Azul: Fantasías y realidades de los Archivos del Museo de La Plata (Rosario: Prohistoria, 2011); and Irina Podgorny and Tatiana Kelly, “Faces Drawn in the Sand: A Rescue Project of Native Peoples’ Photographs Stored at the Museum of La Plata, Argentina”, MIR, 39 (2010), 98-113. See also EAP095: ‘Faces drawn in the sand’: a rescue pilot project of native peoples’, photographs stored at the Museum of La Plata, Argentina, http://eap.bl.uk/database/overview_project.a4d?projID=EAP095; and EAP207: ‘Faces drawn in the sand’: a rescue project of native peoples’ photographs stored at the Museum of La Plata, Argentina - major project, http://eap.bl.uk/database/overview_project.a4d?projID=EAP207.

13 On the history and transformations of the museum, see Podgorny and Lopes, El Desierto; Farro; and Susana V. García, Enseñanza científica y cultura académica: La Universidad de La Plata y las ciencias naturales (1900-1930) (Rosario: Prohistoria, 2010).

14 Farro, ch. 3.

15 See, for instance H. Glenn Penny, Objects of Culture: Ethnology and Ethnographic Museums in Imperial Germany (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), in particular ch. 5. This argument is fully developed in William Flinders Petrie, “A National Repository for Science and Art”, Royal Society of Arts Journal, 48 (1899-1900), 525-33; and also Irina Podgorny, Un repositorio nacional para la ciencia y el arte (Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2012).

16 See García, Enseñanza científica y cultura académica, ch. 4; and idem, “Ficheros, muebles, registros, legajos: La organización de los archivos y de la información en las primeras décadas del siglo XX”, in Los secretos de Barba Azul: Fantasías y realidades de los Archivos del Museo de La Plata, ed. by Tatiana Kelly and I. Podgorny (Rosario: Prohistoria, 2011), pp. 41-65 (pp. 59-64).

17 Thus, late in the nineteenth century, whereas the Department of Geology kept their records and noted all the mineralogical samples and objects coming to the collections, others, such as the Department of Zoology, left their collections unrecorded. In 1908, the Departments of Anthropology and Zoology started an inventory book, following the protocols of the new university. Later, when the Photographic Archive was created, Emiliano MacDonagh and Ángel Cabrera, in charge of the Departments of Zoology and Palaeontology respectively, were two of the few chiefs who donated photographs from their collections to the archive. See García, “Ficheros, muebles, registros, legajos”. What caused this difference in attitude to institutional policies and record-keeping, a difference that characterised the running of the institution for most of its history? Beyond the personalities of the employees, one might consider, first, the structural weakness of the institution in comparison to the weight and relevance of certain individuals (which has its correlative in the weakness of the museum director vis-à-vis the “jefes de sección”); and second, the micropolitics of the museum, namely the inner alliances and conflicts which may have caused resistance to certain directives emanating from the authorities.

18 García, “Ficheros, muebles, registros, legajos”.

19 Podgorny and Kelly, “Faces”, pp. 99-101.

20 García, “Ficheros, muebles, registros, legajos”, pp. 59-64.

21 Lehmann-Nitsche, pp. 64-66. I thank Máximo Farro for this information.

22 Podgorny, “Momias que hablan”, p. 51.

23 On Bennati’s travels and museum, see Podgorny, Viajes en Bolivia; idem, “Travelling Museums and Itinerant Collections in Nineteenth-Century Latin America”, Museum History Journal, 6 (2013), 127-46; and idem, El sendero del tiempo y de las causas accidentales: Los espacios de la prehistoria en la Argentina, 1850-1910 (Rosario: Prohistoria, 2009), pp. 271-91.

24 Irina Podgorny, “La industria y laboriosidad de la República: Guido Bennati y las muestras de San Luis, Mendoza y La Rioja en la Exposición Nacional de Córdoba”, in Argentina en exposición: Ferias y exhibiciones durante los siglos XIX y XX, ed. by Andrea Lluch and Silvia Di Liscia (Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 2009), pp. 21-59 (pp. 39-41); and Juan Draghi Lucero, Miguel Amable Pouget y su obra (Mendoza: Junta de Estudios Históricos, 1936).

25 See also http://eap.bl.uk/database/large_image.a4d?digrec=1120613;r=4827 and http://eap.bl.uk/database/large_image.a4d?digrec=1120614;r=5436

26 For Latin America, in particular Peru, see Keith McElroy, Early Peruvian Photography: A Critical Case Study (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Research Press, 1985), pp. 15-45. See also Robin Wichard and Carol Wichard, Victorian Cartes-de-Visite (Princes Risborough: Shire, 1999).

27 McElroy, Early Peruvian Photography, p. 15.

28 Martin J. S. Rudwick, Scenes From the Deep Times: Early Pictorial Representations of the Prehistoric World (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1992), pp. 201-02. See also Irina Podgorny, “Fossil Dealers, the Practices of Comparative Anatomy and British Diplomacy in Latin America”, The British Journal for the History of Science, 46/4 (2013), 647-74.

29 “Decreto de Creación de un Museo Nacional”, in Fernando Viera (comp.), Colección legislativa de la república del Paraguay (Asunción: Kraus, 1896), p. 84.

30 Irina Podgorny, “From Lake Titicaca to Guatemala: The Travels of Joseph Charles Manó and His Wife of Unknown Name”, in Nature and Antiquities: The Making of Archaeology in the Americas, ed. by Philip Kohl, I. Podgorny and Stefanie Gänger (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 2014), pp. 125-44.

31 Guido Bennati, “Al Señor Viviani: Encargado de la Legación Italiana en Lima”, El Pueblo Constituyente, Cochabamba, September 1876.

32 Podgorny, Viajes en Bolivia, pp. 30-33.

34 Dionisio M. González Torres, Boticas de la colonia y cosecha de hojas dispersas (Asunción: Instituto Colorado de Cultura, 1978), pp. 67-78; and Juan Francisco Pérez Acosta, Carlos Antonio López, obrero máximo, labor administrativa y constructiva (Asunción: Guarania, 1948), p. 309. Estigarribia is also mentioned by Augusto Roa Bastos in his historical novel from 1974, I, the Supreme. On Roa Bastos, see Roberto González Echevarría, “The Dictatorship of Rhetoric/The Rhetoric of Dictatorship: Carpentier, García Márquez, and Roa Bastos”, Latin American Research Review, 15/3 (1980), 205-28; and idem, The Voice of the Masters: Writing and Authority in Modern Latin American Literature (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1985), in particular ch. 3.

35 Podgorny, Viajes en Bolivia.

36 Irina Podgorny, “Coleccionistas de Arena: La comisión médico — quirúrgica Italiana en el Altiplano Boliviano (1875-1877)”, Antípoda, 11 (2010), 165-88; and idem, “Momias que hablan”.

37 Podgorny, Viajes en Bolivia.

38 Diplomas i Documentos, El Naturalismo positivo and Bennati’s speeches from the Boletín de la Exposición Nacional de Córdoba are kept in the National Library of Argentina (the library of Harvard University has another copy of Diplomas). The Museo Histórico of Santa Cruz de la Sierra in Bolivia holds Relación del viaje, while the Benson Latin American Collection at the University of Texas at Austin has Compendio de los trabajos. These works had been previously mentioned and collected by the Bolivian historian Gabriel René Moreno (1836-1908) in his Biblioteca boliviana, catálogo de la seccion de libros i folletos (Santiago de Chile: Gutenberg, 1879). The French trial is kept at the BNF (see note 59).

39 El Titicaca, 9 November 1876.

40 “Historia descriptiva de Bolivia”, La Reforma, 15 November 1876.

41 “Museo”, La Reforma, 16 December 1876. For a description of the museum, see Podgorny, El sendero del tiempo, pp. 271-91.

42 “Historia descriptiva de Bolivia”, La Reforma, 15 November 1876; and “Museo Boliviano”, El Ferrocarril, 7 March 1877.

43 “Solicitada. Al Dr. Bennati. Los jujeños. La verdad”, La Reforma de Salta, 7 May 1879. The photograph can be seen at http://eap.bl.uk/database/large_image.a4d?digrec=11

20599;r=19169

44 See, for instance, Douglas Keith McElroy, The History of Photography in Peru in the Nineteenth Century, 1839-1876 (Ph.D. thesis, University of New Mexico, 1977).

45 La Comisión Italiana, “Escursion a Tiaguanaco y al lago Titicaca”, La Reforma, November 1876.

46 Pascal Riviale, Los viajeros franceses en busca del Perú Antiguo, 1821-1914 (Lima: IFEA, 2000), pp. 145-47.

47 Paul Broca, “Sur des crânes et des objets d’industrie provenant des fouilles de M. Ber à Tiahuanaco (Perou)”, Bulletins de la Société d’anthropologie de Paris, 3/1 (1878), 230-35.

48 Luis Monguió, “Una desconocida novela Hispano-Peruana sobre la Guerra del Pacífico”, Revista Hispánica Moderna, 35/3 (1969), 248-54; and Pedro Gómez Aparicio, Historia del periodismo español: De la Revolución de Septiembre al desastre colonial (Madrid: Editora Nacional, 1971), p. 204.

49 Gustavo Torrico Landa and Cristóbal Kolkichuima P’ankara, La imprenta y el periodismo en Bolivia (La Paz: Fondo Ed. de los Diputados, 2004), p. 225.

50 “Museo Boliviano”, El Ferrocarril, 7 March 1877.

51 “Museo Boliviano”, El Ferrocarril, 14 March 1877.

52 Pascal Riviale and Christophe Galinon, Une vie dans les Andes: Le journal de Théodore Ber, 1864-1896 (Paris: Ginkgo, 2013). I am very grateful to Pascal Riviale for his hints regarding Théodore Ber and Stübel’s collection.

53 See the IFL’s Archive for Geography at http://www.ifl-leipzig.de/en/library-archive/archive.html. On Stübel’s collections, see Babett Forster, Fotografien als Sammlungsobjekte im 19. Jahrhundert: Die Alphons-Stübel-Sammlung früher Orientfotografie (Weimar: VDG, 2013). Another set of Grumbkow’s photographs are kept in the Museo de Arte de Lima; see Natalia Majluf, Registros del territorio: las primeras décadas de la fotografía, 1860-1880 (Lima: Museo de Arte de Lima, 1997). One of the images dispatched by Perillán y Buxó to Madrid came to be known as the portrait of Alphons Stübel in Tiwanaku. However, as Riviale’s recent research has proven, the man in the picture is not Stübel but M. Bernardi, Ber’s travel companion. The image is available at http://ifl.wissensbank.com

54 “El Museo Bennati, Reportage transeunte”, La Patria Argentina, 24 January 1883.

55 “Como complemento de este Grupo (diversos) se ha colocado una variada y gran colección de vistas fotográficas, que representan diferentes lugares, edificios, ruinas, etc. entre las que sobresalen las del antiquísimo pueblo de Tiaguanacu, con sus gigantescos monolitos. Está completada esta colección con los trajes naturales de casi todos los países recorridos”. Bennati, Museo Científico, p. 10. Italics and translation are ours.

56 McElroy, Early Peruvian Photography, p. 26. The photographs are available at http://eap.bl.uk/database/overview_item.a4d?catId=142284;r=30106

57 McElroy, Early Peruvian Photography, p. 28.

58 Grumbkow’s photographs are available via the IFL’s catalogue at http://www.ifl-leipzig.de/en/library-archive/online-catalogue.html

59 EAP095 and EAP207 benefited from the professional expertise of Tatiana Kelly, Máximo Farro, Susana V. García and Alejandro Martínez, to whom I express my deepest gratitude: it was their engagement and commitment that made this article possible and that led to the success of both projects. Silvia Ametrano, the director of Museo de La Plata, Américo Castilla, Lewis Pyenson, Maria Margaret Lopes and José A. Pérez Gollán supported us in multiple ways: we are all indebted to them and, in particular, to Cathy Collins, who was always there to help and advise from London. We also want to mention the permanent support provided by Lynda Barraclough, former EAP Curator. Part of the bibliographical materials used in this chapter was available to us because of the permanent support of Ruth Kessentini, Ellen Garske, Birgitta von Mallinkrodt and Hans-Jörg Rheinberger from the Max Planck Institute for the History of Sciences in Berlin (MPI-WG). This paper — which also acknowledges the support of PIP 0116 — is based on research undertaken at Biblioteca Nacional de la República Argentina, Biblioteca Luis A. Arango in Bogotá, Bibliothèque Nationale de France and the Leibniz Institute for Regional Geography in Leipzig (Archiv für Geographie). The chapter — which benefited from the comments by Maja Kominko and two anonymous reviewers — was initiated while I was on a Fellowship at IKKM-Bauhaus Universität Weimar. I am very grateful to Daniel Gethmann and Bernhard Siegert for their productive suggestions. The final pages were, however, finished on a Visiting Professorship as the Chaire Alicia Moreau at the Université Paris Diderot - Paris 7. In this context, the discussions with and suggestions made by Gabrielle Houbre, Pascale Riviale, Natalia Majluf, Roberto Ferrari and Stefanie Gänger were fundamental for understanding the paths of the photographs mentioned here. This paper is dedicated to Pepe, in memoriam.