14. Hearing images, tasting pictures: making sense of Christian mission photography in the Lushai Hills district, Northeast India (1870-1920)

© Kyle Jackson, CC BY http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0052.14

If today the sky were to thunder and the local church bell to peal in the mountaintop village of Aithur in Northeast India’s Mizoram state, the resident Christian Mizo villager would simply pack an umbrella to church. However, a century ago the same soundscape would have held radically different meaning for most listeners.2 Thunder was not a sonic shockwave devoid of transcendental meaning, but rather evidence of the god and healer Pu Vana — Grandfather of the Sky — as he dragged a bamboo plate about the heavens. The church bell would have rung out in direct contravention of the village headman’s strict order for its silence. Its sound was thought to bring pestilence upon Aithur, whose tiny minority of first Christian converts were far from welcome and farther still from representing the near total majority that Christians would enjoy a century later, when the first converts were long dead and Pu Vana long forgotten.3

In the last decade, the field of sensory history — or the “habit” of writing sensory history, the term historian Mark M. Smith employs to refer to its overarching utility — has made great strides in advancing our understanding of historical and cultural articulations of human ways of knowing.4 While this body of scholarship has been helpful in broadening our understanding of the complex history of the human sensorium, it nonetheless treats the continents with an uneven hand. For example, the bibliography of Smith’s recent overview of scholarship sensitive to the history of the senses reveals a ratio of roughly 8.5:1 for studies of the west to those of the wider world.5

Historians attentive to non-western countries have yet to examine in depth the hill tribes of India’s Northeastern frontier and the history of their ways of knowing. In 1935, many Northeastern hill areas were formally deemed “excluded areas” by the British Raj; until 2011, Mizoram itself remained a region restricted to visitors. Entire textbooks on the history of the subcontinent have been written with only a scant sentence or two reserved as a quota for the tribes of the comparatively less populated Northeast.6 Only of late, with the publication of works like James C. Scott’s The Art of Not Being Governed, a special issue of Journal of Global History, Andrew J. May’s study of the Khasi Hills and Indrani Chatterjee’s monograph on debt and friendship, is scholarly attention turning to this kaleidoscopically diverse, borderland region.7 The present chapter, a preliminary “history through photographs”, mobilises historical sources only recently located and digitally preserved in Mizoram (known in colonial times as the Lushai Hills District), allowing us to begin not only to see, but also to smell, taste, hear and feel an entirely new scene in upland Northeast India. By paying special attention to the human sensorium, we pry open some crawlspace towards a thicker and more context-specific understanding of how Christianity in the Lushai Hills became a specifically and overwhelmingly Lushai Hills Christianity.

Sources and method

A vast chasm separates the supersaturated world of images that we inhabit today from the visual world of those creating photographs in historical Lushai Hills. As historian Robert Finlay points out, someone surfing the internet or walking down a supermarket aisle sees “a larger number of bright, saturated hues in a few moments than [would] most persons in a traditional society in a lifetime”.8 Save for exceptions like “beetles, butterflies, and blossoms”, the world of nature reaches the human eye “chiefly in browns and greens beneath a sky of unsaturated blue”.9 Today, the supersaturated colours of synthetically-produced objects artificially overexcite the human visual cortex, demanding for the first time in human history the full biological potential of human colour vision. Meanwhile, the modern ubiquity of camera devices (there are seven in various guises within a four-metre radius of the desk at which I write) has turned modern photographs into ephemeral “snapshots”.

By contrast, late-nineteenth-century Lushai Hills was a world in which a group of Mizo villagers walked for miles to the colonial headquarters of Aijal, hoping to see a colonial official’s family photographs.10 Photography here was not part of an everyday “dull catalogue of common things”.11 For whatever reasons, photographs could be a destination in themselves. Only by leaving our modern baggage at the door can we begin to appreciate the extraordinary in what might otherwise seem a bunch of old “snaps”: photographs were in fact the most concentrated human-made visual object then available in the Lushai Hills, unmatched in detail, realism, resolution and novelty.

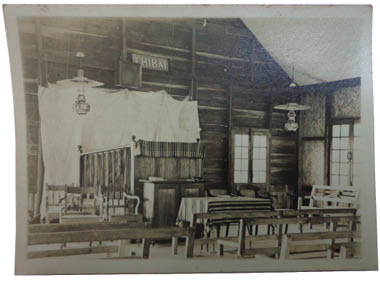

It is in part to experiment with a methodology of wide-eyed wonder that this chapter on the visual history of the Lushai Hills eschews a typical photo-album approach (where one photograph after another appears ordered by chronology, typology or geography). Here, we instead purposefully engage with rarity — indeed primarily with a single photograph. Taking as our base unit a circa-1913 photograph of the interior of Aijal’s flagship Mission Veng Church (biak in), we sidestep the question of whether, in history-writing, images support texts or texts support images, to instead bring together a range of contemporary textual, oral and visual sources as equals in the analysis of a single image.12 We thus take a page from the methodological playbook of French author Raymond Queneau, whose Exercices de style (1947) retells the same short story in 99 different literary styles.13 I organise the analysis here into six sedimentary layers — the different styles, for our purposes — of human knowing: hearing, seeing, tasting, smelling, touching and, as a wild card, the Mizo harhna (or “awakening”). The senses are far from quarantined into these analytical containers, nor is this list exhaustive. With the inclusion of a sixth “sense” — the non-biological but still sensory-charged world of the historical Mizo harhna — we can attempt to approach the earliest Mizo Christians on their own terms, remaining attentive both to the diversity of sense broadly defined and to the potential hamfistedness of traditional western models of sense when applied without due reflexivity to sensory cultures in the wider world.14

Listening in the biak in

From 1911-1912, the people living in what the British Raj knew as the Lushai Hills District suffered mautam (bamboo death). As entire mountainsides of bamboo simultaneously flowered, seeded and died, jungle rat populations skyrocketed in number with the mass availability of protein-rich seeds. Exhausting these, the rodents turned next to village rice crops and grain stores; as the colonial government in Aijal, as well as Baptist and Welsh Calvinistic Methodist foreign missionaries in Aijal and Serkawn village, scrambled to distribute meagre relief loans of rice, villagers subsisted on jungle roots.15 Within such a context of hunger and desperation, Christian converts in Mission Veng, Aijal borrowed the fundraising concept of buhfai tham (handful of rice) from Khasia-Jaintia and Garo churches in the neighbouring Khasi Hills, and began donating precious handfuls of rice towards the construction of a new chapel. Our central photograph (Fig. 14.1) depicts the result: the Mission Veng biak in, constructed in 1913.

Fig. 14.1 Mission Veng Church, c. 1913-1919,

Mizoram Presbyterian Church Synod Archive, Aijal, Mizoram, India.

Like the life-sustaining jungle tubers, sound was far more important to people in early-twentieth-century Lushai Hills than it is in Mizoram today.16 Indeed, life and death were literally at stake in the audible realm, for malevolent forest phantasms (ramhuai) lived in the forest, listening to and seizing those people careless enough to utter the names of humans, certain animals or ramhuai aloud. Mizos, too, interacted with this forest world through auditory channels. Lasi Khal was the hunter’s chanted sacrifice to the female forest spirit Lasi, who decreed his success or failure in the hunt; the auspicious crow of the rooster informed a village headman’s surveyors as to whether a given clearing was healthy and thus habitable; the tap of a metal knife (dao/chempui) on fallen bamboo shafts betrayed the position of protein-rich worms (tumlung) to the careful listener.17

The jungle offered up only occasional instances of sonic uniqueness: the onomatopoeic huk of the barking deer, the throaty chawke of lizards, the kaubupbup of jungle birds, the kek and kuk of monkeys and gibbons were all infrequent interruptions of the otherwise “constant hum or whir of the insect world”.18 The human village added voices to the soundscape: women’s voices in public at certain times, travelling to the water source or to the jhum field, men’s voices at others, setting out on early morning hunts.19 Spikes in volume were unusual and unpredictable, save for the assured din of domesticated animals waking at sunrise, the thunder claps of the rainy season and the singing and dancing at periodic festivals (kut).

The early Christian church was an acoustic outlier in the typical village soundscape. The interior of the church in our central photograph has its own sonic signature, one unique in the Lushai Hills. Mizo structures were always constructed in bamboo weave, their thatched and layered design highly reminiscent of the noise control panels preferred in acoustic design today. One need only step into a thatched bamboo home in a modern Mizo village to hear the difference: the bamboo weave radically reduces reverberation time, diffusing and absorbing sound waves like an anechoic chamber. But though this traditional construction technique is alluded to aesthetically in the 1913 church walls, the structure is primarily made of great planks of acoustically-reflective hardwood, likely teak harvested locally.

The pulpit raised a central speaker so the congregants could hear his voice.20 The elders (upa) seated in the individual chairs visible in the photograph, facing the congregants, had the poorest view of the platform, but by far the best sound from it. Speech loses six decibels in sound level each time the distance in metres is doubled from speaking mouth to listening ear. Hence, those nearest the Welsh Calvinist and Mizo preachers, whose doctrine emphasised hearing the Word of God, were not only the most senior in the hierarchical church structure as upas, but also most privy to the sound of the Word itself. In Mizo terms, they were the most bengvar (literally, “quick hearing”, or informed).21

Regardless, however, of where one sat, the room depicted in the photograph was the largest and most reverberative single space in the region, encouraging human voice and song in ways hitherto unheard in the Lushai Hills. The church structure employed the type of high, gabled ceiling that, as the historian of hearing Richard Rath notes, “sonically fortif[ies]” congregants’ singing, praying and audible verbal and non-verbal responses.22 In inherently promoting such a uniquely live acoustic space, this built environment could itself have been a catalyst for the “noisy” hlimsang Mizo revivalist song and dance that so worried stoic missionaries throughout the early history of Christianity in the region. In a very real sense, this particular church was not just a building. It was also an instrument.23

The church resounded outwards too. Alain Corbin’s pioneering work on the social history of the church bell in rural France resonates in colonial Lushai Hills, for here also the Christian community was inherently reliant on the church’s brass gong.24 Residents in the model Christian village of Mission Veng had to live within earshot to know when to attend mandatory services — the invisible “acoustic horizon” of the gong defined the physical range of the community.25 In Mission Veng, a handbell announced schoolchildren’s classes, while a brass gong heralded church services. Tone and frequency thus attended concepts of time and punctuality.26 Such human-made sonic tools were second only to guns in the range and volume of their report.

Within this new auditory milieu, foreign missionary preachers still fought for their own brand of sonic discipline. Physical walls served their obvious structural function, but they also acted as sonic barriers against what missionaries heard as the “unruly” sounds of the village and of agents of Satan, the “evil spirits” who disturbed outdoor preaching tours by making livestock “cackle”, “squeal”, “bark”, “bleat”, and human babies “cry”.27 Part of the missionary project within the church’s walls was an imposition of what historian Andrew J. Rotter calls “respectable, mannerly sound”.28

Early missionary preaching seems to have baffled the Mizo, who repeatedly interrupted sermons with unrelated questions and diversions. The central pulpit in our photograph points to a new way of ordering communication and sound. Verbal communication in the hills had no precedent for the monologue, the expectation of silence lasting “twenty or thirty minutes” while a single speaker stood in front of a seated group.29 Mizo communal meetings were more casual, held in what the missionaries would have called an informal manner on verandahs or at the entrance to villages.30 In song, too, Mizo congregants had difficulty with the Welsh fourth and seventh scale degrees, their efforts sounding flat or “plaintive” to western ears. Traditional Mizo musical languages operated in five-note pentatonic registers, whereas Welsh mission music assumed an eight-note, or diatonic, scale.31

In many ways, then, Christianity arrived packaged as a bafflingly foreign sonic cacophony. Missionaries record that it was only when they started promoting Jesus less as a redemptive saviour from sin and more as an ally (Isua Krista, the “vanquisher” of the huai) that Mizos suddenly started listening.32 This Isua Krista claimed power to intervene in the ancient aural regime of the ever-listening huai. The very radicalness of the Mission Veng church’s aural practices — jarringly foreign scales, tempos, bells and monologues — would thus have been wholly consistent with the arrival of the missionary’s sonic revolutionary, Isua Krista.

Tasting in the biak in

Here, our central photograph demands some imagination, for it does not depict anything particularly taste-worthy. Following on from our discussion of hearing, one way towards taste is to imagine inhabiting the photograph, with its congregation in song. Song in the Lushai Hills had always been tied to drink, and the ear to the taste bud. An oft-quoted missionary report records that early Christian hymns were frequently met with confused questions of, “Where is the zu?”.33 Communal singing demanded rice beer. Indeed, this link was so strong that missionaries soon felt compelled to institute a twelve-month probationary period on all candidates for baptism: new Christians had to keep the Sabbath Day for a year, abstaining from both zu and sacrificing animals for health.34 Missionary translations tiptoed around inconsistencies in their message. In a purposeful lexical distancing, the wine of the Last Supper and Communion was translated into Mizo from English partly phonetically, as uain tui (wine liquid), while sweetened water was used in the ritual itself.35 Taste was policed with a watchful eye and a discerning tongue, with alcohol banned from communion cups and missionary print media alike.

Such missionary authority over taste could become even further entwined in everyday life, as when missionaries were granted the government monopoly over the local distribution of salt. Then as now a favourite condiment of the Mizo diet, salt sustains both health and life, particularly in such a hot climate.36 Colonial records from the 1880s and 1890s reveal a sellers’ market: brokers were making 100% profit, trading salt from the plains for rubber from the Mizo hills; marching British Raj soldiers were being stopped by Mizo villagers hoping to trade foodstuffs not for money, but for salt; and in Mission Veng, too, missionaries paid for construction labour with the popular condiment.37 Mizos craved salt for medicines to treat goitres and to soothe burns, and, of course, for food, particularly bai — bean or pumpkin leaves boiled with vegetables and fermented pig fat (sa um).38 The first letter written by a Mizo — in 1897, from the village headman Khamliana to Kumpinu (Company Mother) Queen Victoria herself — explained, “we have become your subjects now and in this distant land live by your rice and salt”.39

Thinking of our central photograph and attuned to our sense of taste, we suddenly see the pulpit at the front of the church as occupied not only by foreign pastors, but also by salt barons, whose open- or close-fistedness meant everything to anyone with burns or goitres, or indeed anyone with food they wished to cook. Imported salt in the Lushai Hills would also become an “unmistakably modern” good, first in terms of its gradual devolution (imported salt — as opposed to the salt-spring varieties of “Lushai salt”, available in small quantities —was the first luxury foodstuff to become prevalent amongst the general populace), and second in terms of its trade (salt was also the first luxury foodstuff “to become considered essential by the people who had not produced it”).40 Modernity had its own attendant tastes.

Sometimes the sheer foreignness of the Welsh missionaries’ taste preferences met with baffled amusement. For instance, one Mizo from Aijal is recorded as deeming the missionaries’ toast altogether too “noisy” for human consumption.41 However, certain equally foreign conventions of missionary-normative taste and tasting could have a much deeper significance. Viewed on its own, the missionary pattern of serving food on individual plates or communion sweet-water in individual bamboo cups, promoted for hygienic reasons to Mizo congregants, might seem inconsequential enough at first blush.42 But these patterns were a part of a whole gamut of colonial practices that worked to promote the individual. New names and individual identities grew increasingly real as they were repeated in public and written into “property deeds, tax returns, and school registration forms”,43 while Christianisation began to imbue old names with new Christian undertones. By the time our central photograph was taken, the Mizo names of Lalrinawma and Lalliani would have denoted “the Lord is trustworthy” and “the Lord is great” respectively, whereas only decades earlier they had referred not to Lal Isua (Lord Jesus), but to a historical lal, or village headman.

As a digitisation team from the British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme (EAP),44 we travelled around Mizoram in 2011, following thick webs of kinship connections and uncovering in Mizo homes an array of individual forms and certificates that were issued by colonial institutions long before the rise of any predominantly literate public sphere.45 These historical collections were maintained as often by professional and amateur Mizo historians as by the rural and urban descendants of historical village headmen or by those early educated Mizos who had lived in the mission centres and beyond. Everywhere, the act of colonial documentation had generated new identities that apparently needed to be preserved.46 Many such colonial files are still used in legal battles over land entitlement today.47

The broader encounter with the colonial state worked to pull individuals out of communitarian social networks. In a world where people were normally defined within networks of indebtedness (of marriages, friendships, oaths or a variety of possible fealties to a village headman, any of these potentially spanning generations), colonial bureaucratic practices did not document existing individual identities so much as create them.48 Networks, village identities and multi-generational debts were irrelevant to the matrices of standardised, individualised files on which colonial bureaucracy and surveillance in Aijal depended.

As Adam McKeown has shown in the case of China, the act of bureaucratic documentation can be a powerful force towards individualisation.49 In the Lushai Hills, the two mission stations demanded individual hospital in-patient names, dispatched myriad certificates for Sunday School, recorded the names of individual congregants in vast registers and offered salvation on a person-by-person basis, devoid of any ancestral or familial articulations. Government authorities took individuals’ thumbprints; offered and monitored individual loans during famines; licensed individuals to own shops and guns, and individual chiefs to own property (via standardised ramri lekha forms); restricted individual mobility; stationed writers in each village to record individual births and deaths; granted individual savings books and passbooks; and counted up all individuals in the district in 1901 and every decade thereafter. In 1902, the Sub-Divisional Office in Lungleh was keeping 49 separate register books, including books for house tax, guns, periods of leave, criminal cases, obituaries and lists of Mizo “coolies”.50

The Mizoram State Archives today are bursting with colonial papers that assumed and mapped individual identities, and with emotive appeals to such papers by village headmen who were quickly made to understand the need to work within the matrices of these files, lest they forfeit rights to the land, jungle and village headship. One’s qualifications were no longer the sole purview of a flexible village memory, embedded within matrices of family, bride price, oath, debt, personal and familial deeds, and local history. Missionary tastes and standards of right eating and drinking must be viewed as a part of a much larger colonial challenge to everyday ways of living, knowing and being known. It was within a very specific and atomising colonial context that Mizos learned to eat from individual plates, to drink from individual cups, to abstain from communal pots of rice beer and, indeed, to believe in only one soul inhabiting each human body. Mizos before had always had two.

Smelling in the biak in

Following our noses into our central photograph, we learn that Christians in the Mission Veng biak in were intended by missionaries to be differentiated by smell. Specific rules were applied to the residences immediately surrounding the church in order to ensure that this was so: stipulations included a separate latrine for each home and separate buildings to house animals. In addition, converts patronised the weekly day called Puan suk ni (washing-up day) — a missionary translation into Mizo of the noun “Saturday”, implying ideas of both hygiene (the godliness and healthiness of washing) and time (the concept of a named day in a seven-day week).51

A common thread running through the missionary literature is disgust with the smell of the unredeemed Mizo. Mizos lived in “squalid hovels”, their “hair matted with clay”.52 In contrast, the mission station served as a “model of order [and] cleanliness”, and missionaries who lived there filled their accounts with praise for the exemplary Christian Mizos and, by association, for the transformative power of their god: “our [Mizo student] children are much cleaner than any other children”.53 The link between Christianity, cleanliness and olfactory neutrality was portrayed and manufactured as self-evident as much as it was insisted upon. When one Lushai woman came to see Pu Buanga (J. H. Lorrain) and professed to be a Christian, the missionary told the “abominably filthy” woman he would not believe it “until she made herself cleaner”.54

The manufacture and continuous repetition of such a sensory stereotype was an important part of the missionaries’ civilising mission and of the construction of a Mizo “race”, seeking to protect the senses against affront as defined by a missionary-normative nose. In an offhand comment in 1891, a colonial superintendent pointed out that the Mizo ideas of “disagreeable smells are not ours”; arriving three years later, missionaries worked at bringing the Mizo sense of smell around, towards sensing in “right” ways.55 The olfactory was thus ideological. Missionaries had a self-imposed duty as “more sensorily advanced westerners to put the senses right before withdrawing the most obvious manifestations of their power”.56

Missionaries lived among and smelled the Mizos with whom they worked on a daily basis — Mizos who in their eyes looked and smelled filthy and, worse, did not know it. Early on, an exasperated Pu Buanga noted that “to teach the inseparableness of Godliness and cleanliness… seems to be the hardest doctrine of any for them to understand or act upon”.57 Over a decade later, the missionary was still frustrated that local Mizos remained unconcerned with washing.58 The righting of this sensory wrong provided significant justification not only for the white missionary “staying on”, but also for the non-devolution of his authority. In terms of pure subjectivity, the white missionary nose was the most powerful nose (indeed, which Mizo was ever qualified to disagree?), powerful enough even to ignore its own hypocrisy. In one instance, in early private letters home, two missionaries told of not bathing for two weeks on account of a water scarcity, apparently oblivious to the human effort required to transport water in the hills (by way of bamboo tubes generally carried in baskets on Mizo women’s backs).59 While foreign missionaries handed out cakes of soap as school prizes, Christmas gifts and tokens of attendance, there could not have been enough soap to lift contemporary Mizos up to olfactory equality.60 The extension of soap and right-smelling were potent and highly visible symbols for the missionaries of “improvement” and of civilisation, yet missionary racial and sensory stereotypes simultaneously barred Mizos from full membership of this civilisation, no matter how much the converts washed.61

The question of what made a smell “good” or “bad” was culturally subjective in a radical sense. Using the visual orientation of our central photograph as a perspectival thinking tool, we can in fact bend historians’ usual assumptions about the missionaries’ civilising mission back on themselves. As early as 1903, a new compound noun had crystallised in the Mizo lexicon: “the foreigners’ smell”, used to refer to the missionaries’ use of soap.62 The deprecating label had gained some traction in the Hills, and J. H. Lorrain heard it across multiple villages. In one instance, he was baffled when the Mizo owner of a house at which the missionary was staying “ran over to the other side of the street muttering, ‘I can’t stand the smell any longer!’”.63 When asked by Pu Buanga what she meant, a passerby seemed surprised at having to explain what appears to have been a smell as familiar as it was unpopular: “Why! The foreigners’ smell — the smell of soap!”.64

Here, the repulsive personal habits of the missionaries made them disgusting and unacceptable. Useful analyses of the “other” have appeared in recent historiography where the “other” generally refers to “non-Europeans, as seen through European eyes”.65 Seated in the Mizo congregant pews of our central photograph, facing the missionary leaders rather than peering over their shoulders, we perform an about-face: if indeed the Mizo themselves ever thought in such generalising terms, the foul-smelling “other” could equally be European. As anthropologist Constance Classen points out, the dominant classes in a society often define themselves in positive olfactory terms against their perceived subordinates.66 In 1903 Lushai Hills, who was subordinate seems to have depended upon who was doing the smelling.

Touching in the biak in

A clear hierarchy of physical comfort is visible in our central photograph. The chairs of the elders (upa) and pastors face the congregants. They use at least twice the wood per seated person as the pews opposing them; the leftmost chairs are designed with top- and lower-rails, as well as three vertical spindles offering support in line with the upa’s spine. The mid-backs of general congregants were supported crosswise, a single bar bisecting the spinal cord. We see that the pastors, sitting in the finest seats of all behind the central table, benefited from the ergonomic elasticity of pressed sheet cane backings for their chairs, these sheets (almost certainly machine-woven by this time) pressed and glued into grooves at the back of the chair’s frame. The glare on the rightmost of these two chairs in the photograph reveals careful sanding and softer edges. For their part, the edges on the congregants’ benches are sharp and unfinished, devoid of even the curved visual ornamentation that elaborates the arms of the upas’ chairs. This was a gendered hierarchy of tactility, for only men (white men and those chosen Mizo trainees and pastors closest to them) would have ever occupied the frontmost chairs, or enjoyed their comparative comfort during church services that lasted for “hours on end”.67

Colonial stereotypes about the Mizo often had the haptic at heart, and acted as catalysts for a broader human exhaustion in early-twentieth-century Lushai Hills that did not exclude lay members of the Mission Veng biak in. In the colonial archive, Mizos are above all characterised as lazy (“the Lushai will always scheme out of his work if he can”) and incapable of hard work (their “laziness can only be got over by good supervision”).68 Though comparatively light on the ground in terms of actual manpower, colonial officials were uncompromising in their demands, overseeing what historian Indrani Chatterjee has called “government by terror”.69 Mizo households groaned under the imposition of heavy taxes (chhiah) payable in cash or rice, even in times of famine, and the ten days’ forced “coolie” (kuli) hard labour that required men to travel and work anywhere in the Lushai Hills District with meagre or no pay.

The district was explicitly intended to be governed with more flexibility and less accountability, and colonial impositions were only more resented as they were further abused.70 Assistant political officer C. S. Murray demanded sexual corvée from Mizo village women until his removal following a village riot in protest; the records of Superintendent John Shakespear’s assistant nonchalantly report the burning of tens of Mizo villages (“We burnt the village and returned to Serchhip”); village headmen begged for relief from the crippling debt of loans extended by the government in times of scarcity.71 In a private letter dating from 1938, retired officer Shakespear boasts to the contemporary incumbent about the corruption, profiteering and misuse of human labour under his superintendentship decades earlier:

I gather that matters are not as casual now as they were in my day. We had lots of ways of wangling a few rupees when we needed them. That very fine retaining wall and the parapet along the terrace in front of your house represents the result of a raid by Cole, who was acting for me, on the Aijal-Champhai road estimate. The plough cultivation in Champhai, was started by Loch & myself misusing government bullocks and coolies supplied for transport purposes. Then there was the Political Fund, at my uncontrolled disposal. I also instituted a “Political Bag”, into which fines for political offences were put to be used for just things as your rugs. Alas I fear that I should find the Superintendents [sic] job far harder than it was in my day.72

Within such a context of state violence and the rhetorical stereotypes of lazy, savage Mizo “tribesmen” necessary to underwrite it intellectually, kuli-impressed labour was presented as good for the Mizo male. The Mizo skin was to be thickened and the Mizo condition improved through the imposition of a new work ethic — work towards civilisation that, as Shakespear once told a group of gathered males, “you are too lazy to do except under compulsion”.73 In forced labour and in punishment, Mizo bodies thus bore the physical brunt of a colonial stereotype that saw them as too soft. In 1897, a letter from E. A. Gait, Secretary to the Chief Commissioner of Assam, specifically aimed for the extension of the Whipping Act, VI of 1865 into the Lushai Hills District under the Scheduled Districts Act, XIV of 1874. The act granted the superintendent power to sentence Mizos, including juveniles and female tea-plantation workers, to punishments of whipping.74 In 1909, Superintendent H. W. G. Cole had to intervene in what seems to have become a culture of violence in local government itself, issuing a standing order to stop government workers from assaulting Mizos with “light canes etc”.75 To consider the tactile dimensions of our central photograph in the Mission Veng church we must first situate the benches in their haptic context, as filled with exhausted human bodies.

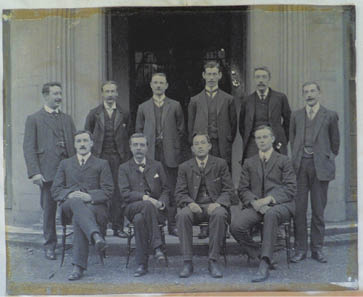

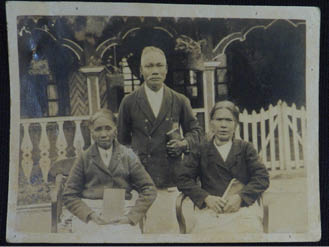

The “improvement” of Mizo tactility extended to the handshake. Earlier this year in Mission Vengthlang, I was taken on a short walk down the hill from the religious tel atop which sits the latest incarnation of the Mission Veng church, to visit Pu Thangliana, the great-grandson of the famous Mizo Christian named Challiana. The family’s history is full of human hurt. The colonial archives tell us clearly that Challiana was born in the 1890s out of travelling political officer C. S. Murray’s demands for sexual corvée. The child was raised by his mother, unbeknownst to Murray, until village rumour of a boy sap reached missionaries J. H. Lorrain and F. W. Savidge in Serkawn. The mother was made to bring the child, and Challiana was taken away from her in the missionaries’ firm conviction that no Mizo could raise a (half) white boy. Under Savidge’s bungalow roof and tutelage, and with Murray’s discreet financial support from abroad, the boy was groomed as a translator, church pastor and medical assistant. He smoothed out the Mizo language translations of his new, missionary fathers and even visited England with Savidge (Fig. 14.2).

Fig. 14.2 Challiana, seated second from right, with F. W. Savidge, seated second from left, and others, n.d., British Library (EAP454/16/1), CC BY.

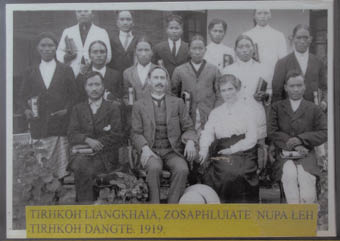

The archives’ version of things is not discussed publicly in Serkawn or Mission Vengthlang today. The family’s genealogy stops at Challiana, for atrocity is sometimes easier to forget than to articulate. But Pu Thangliana’s family photographs and carefully circumscribed memories of his grandfather depict a staunchly Europeanised man.76 Challiana would insist on eating with a fork and knife as well as on handshakes — indeed on careful tactility. At the time, these habits were all strange to his grandson.77 Family photographs digitised under the EAP depict a man dressed impeccably in western clothes — a trope common throughout mission photography of students and chiefs under mission tutelage. As in the cases of cutlery or handshaking, we might be tempted to see a primarily visual marker of difference in such mission photographs (see Figs. 14.3 and 14.4).

But clothes have a crucial haptic dimension, too. Smith reminds us that “the quality and feel of the clothing on the inside, how it was understood to either caress or rub the skin of the wearer” can also suggest something “about the wearer’s skin and [thus] about his or her worth and social standing”.78 Christian leaders like Challiana first had to be deemed, and then had to see themselves as, meritorious of wearing softer, imported, luxury dress — clothing that would have caressed Mizo skin, the human body’s largest sense organ, with a thread count higher and a weave tighter than any puan produced by the Mizo handloom.79 Westernised Christian male leaders wearing softer clothes (Sunday School teachers, medical men and evangelists) were those uplifted individuals on whose behalf missionaries applied for the treasured kuli awl — exemption from the colonial regime’s hated demands for male Mizo labour.80 Changes in Mizo uses and perceptions of tactility, whether via a softer collared shirt or a civilised handshake, said much about politeness, hmasawnna (“cultural progress”) and one’s broader place in society, even as polite conversation today about the same must stop short — must have tact — in discussions about some of these pasts.81

Fig. 14.3 Wedding at Mission Veng Church, n.d., British Library (EAP454/12/1 Pt 2), CC BY.

Fig. 14.4 Church leaders at Mission Veng Church, 1919, British Library (EAP454/13/22), CC BY.

Seeing in the biak in

Early textual records from the Lushai Hills explain how the typical Mizo house was windowless — a widespread security precaution that prevented the huai, or the malevolent phantasms of the forest that caused human sickness, from entering the dwelling.82 Beliefs about health thus dictated architectural design, since windows were portals to suffering. When missionaries made windows mandatory in multiple Christian model villages, not all Mizo Christians were ready to accept such rules.83 Some were convinced that “great misfortune” would befall the village that allowed Christians to so recklessly entice the huai.84 Folk tales were the security cameras of the Lushai Hills, and they recorded huai entering homes through holes in the wall — huai real and physical enough to pull occupants out and slam their heads through the soil.85

Our central photograph, then, allows us to glimpse just how far early missionary architecture transgressed Mizo norms. By switching our perspective from the missionaries to the Mizo, we can here begin to see the extraordinary in what would otherwise just be a source of light or a hole in a wall: windows were dangerous designs from abroad that were ill-suited to the Hills. Photographs show that the Mission Veng biak in was no less than a seventeen-window-sash offender (see Figs. 14.1 and 14.5).86

Bamboo chapels, mission school buildings, the central mission bungalow and the mission dispensary at Aijal all featured windows extraordinary to Lushai belief and building custom.87

Fig. 14.5 Liangkhaia at Mission Veng Church, 1919,

British Library (EAP454/13/22), CC BY.

The Mizo in-patient at a mission dispensary thus had in a real sense to ignore or endure the health risk inherent in the very structure itself. So when a missionary made the offhand jest that, between Christ and windows, “more than one kind of light has come … into Lushai”,88 he was actually touching upon a massive chasm between missionary and Mizo ideas of both health and architecture. For the missionary, an open window letting in air and sunlight was healthy. For the Mizo, it endangered the pursuit of health.

Turning in our central photograph from the windows to the tables, we can make out seven books —three thin (perhaps the New Testaments first printed in 1916, since the complete Bible in Mizo did not appear until the 1950s) and four thick (likely the Kristian Hla Bu, or “Christian Hymn Book ”).89 Like the church windows, the church’s New Testaments were not immune to the infiltration of the huai. In the Mizo-language Gospel of John, one of the first books of the Bible to be translated, Jesus’s response to a crowd’s accusation is “Ramhuai zawl ka ni lo ve [I am not possessed by a ramhuai]”.90 While other words without Mizo equivalents (like “crown”) were simply kept in their English form, the demons of Galilee literally became the huai of Northeast India in this text.91

Meanwhile, the song books pictured would have been hot off the press, for updated volumes of the Hla Bu were released in 1913, 1915 and 1919. The Hla Bu was a living text, with ten versions appearing between 1899 and 1922. The 1919 version was the heftiest and most indigenised at that time, featuring some 558 songs, many by Mizo Christian composers and some, written after the mautam famine of 1911-1912, characterising the world as a place of suffering.92 The Kristian Hla Bu was in fact crystallising around the historical moment these texts were photographed here: no edits followed for twenty years after the 1922 version. By 1919, young Mizo composers like Kamlala (1902-1965) and Huala (1902-1995) started penning lyrics that included elements of the traditional, poetic register of the Mizo language — a lexicon that until then had been largely banned in the church along with traditional drumming, dance and drink.93 That the Hla Bu stabilised at the same time as traditional Mizo drumming and poetic vocabulary made their debuts within Mizo Christianity is no coincidence. Christianity in the Lushai Hills was becoming a vernacularised Lushai Hills Christianity. The Mission Veng biak in, the historical headquarters for the Welsh Calvinistic missionaries, was henceforth one of only two churches in the district where congregants were barred from hearing the traditional drum (khuang) in worship.

As knowledge about literacy, and then literacy itself, spread throughout the early 1910s, Mizo interpretations of the power of the written word abounded. Some realised its potential to transform ephemeral oral and aural declarations into edicts of greater permanency: one lal, or village headman, demanded that the missionary Daktawr Sap (Dr. Peter Fraser) confirm the lal’s declaration so “that it may not be destroyed for ever. I want you very much also to kindly write it in a book”.94 Others decoupled missionary claims about the inherent truth of God’s word while assisting with the translation of it: one Mizo co-translator of the Gospels — not self-identifying as a Christian himself at the time — was known to argue with Mizo converts, claiming that he knew “more about the Gospel than [the converts]” for he had “helped to make it up!”.95 Others saw books as talismans for missionary soothsayers, in the register of traditional Mizo puithiam healers: one Mizo father whose daughter had run away demanded the missionaries “consult their books” to tell him whether she would return to Aijal or run to Silchar.96

Whatever the interpretations, by the time our central photograph was taken, the New Testament had become a mandatory photographic prop in all Mizo Christian circles (see Figs. 14.4, 14.6 and 14.7). Captions on such photographs regularly single out individuals such as the one “sitting in the middle holding books”97 or the one “on the right holding books”.98 Those with books sometimes placed themselves (or were placed) in conspicuous positions of prominence, their tomes emphasised and open, or displayed prominently against their bodies. Mizo Christians, known in the hills as “Obeyers of God” (Pathian thuawi), were under strict injunction to transgress traditional Mizo norms. These could be as emotive as where to bury dead family members, as fundamental as which actions were socially acceptable or as conceptually diverse as ideas about marriage, gender or entry to the afterlife. In doing so, Obeyers of God met with much opposition at this time.

Most likely, Christians held the New Testament especially close in photographs as a visible marker both of difference and of real and genuine personal conviction. Perhaps, too, the burgeoning Mizo literacy was seen as the key conduit to greater Mizo roles in the expanding church and colonial government, for the 1910s witnessed the ordination of the first trained Mizo pastors, the commissioning of the first Mizo Bible Women and the paid employment of the first Mizo evangelists, all while groups of Mizo graduates began to assist the colonial bureaucracy in Aijal. Reading could and did provide Christians with a route around social persecution via colonial brokership.

Fig. 14.6 Suaka Lal, Veli and Chhingtei at Durtlang, 1938,

British Library (EAP454/3/3 Pt 2), CC BY.

Fig. 14.7 “Wives of the Soldiers in Lungleh”, c. 1938, loose photo in J. H. Lorrain’s file, BMS Acc. 250, Angus Library and Archive, Regent’s Park College, Oxford.

Before noticing the books in our central photograph, the congregant’s eye would have been drawn to the pulpit and, above it, to the visual centrepiece of the church interior: the signboard proclaiming chibai (greetings). The prominence of this Mizo word is significant, for it seems to have undergone a revolution in both meaning and usage in the early colonial Lushai Hills. In the late nineteenth century, chibai was in fact part of the vocabulary of human health, employed by a highly specialised Mizo practitioner (puithiam) when he approached forest spirits (ramhuai) with offerings on behalf of the sick.99 Chibai thus functioned as a sort of inter-species pidgin, a human attempt at communication with powerful non-human beings. The word had seemingly little or no public life of its own; the earliest English dictionaries and grammars of the Mizo language ignore it entirely, despite their impressive breadth (Brojo Nath Shaha’s 1884 work spans 93 pages; T. H. Lewin’s 1874 work teaches 1609 phrases) and their emphasis on the basic vocabulary typical of a phrasebook.100 Lewin and Shaha equip readers to ask “What is your name?” but offer no words of greeting.

To contemporary officials (and to our modern ears), the question “What is your name?” may have sounded innocuous enough. But attempting to listen to the question with historical Mizo ears, we can begin to hear the discordant echoes of conceptual chasms that existed between Mizo and colonial, western modes of interpersonal communication. These differences are key to the history of chibai —the word which would come to be elevated to the quintessential personal greeting in colonial Lushai Hills and in today’s Mizoram, catapulted into public use and onto 1930s church platforms. For an historical Mizo, the seemingly mundane question “What is your name?” was actually rather grave, for it would have involved an acute assessment of risk. Personal names were directly related to personal health. Intentionally unattractive names were sometimes given to Mizo children as a precautionary measure against their being stolen by the ramhuai.101 Names were thus an asset that cost nothing and yet could pay back in spades: a properly given name could be an important prophylactic against ill health.

Since names had transcendental value, they could prove a battlefield between the physical world of the Mizo and the spirit world of the ramhuai. Thla ko was the verb for calling back a Lushai soul (thlarau) that had escaped its two-souled human body only to be seized by the ramhuai.102 Losing one’s thlarau meant sickness. The responsibility then fell to the grandfather (pu) of the sick person to call aloud the name of his grandchild at the abode of the huai — an experience harrowing in itself. The lost soul could then be escorted home safely to its body, whereupon the afflicted person could recover.103

Names were thus to be jealously guarded, “since the name of a being also encapsulated the [thlarau] of the being”.104 Historian Indrani Chatterjee notes that for a Mizo to be addressed by her childhood nickname “constituted a public invitation to seizure” by the ramhuai who continually eavesdropped on human conversation.105 In 1912, Superintendent Shakespear noted that there was “a strong and general dislike among all Lushais to saying their own names”,106 this perhaps not least because anti-huai names could be embarrassingly unattractive. Mizos in the early twentieth century would instead introduce themselves via a cautious triangulation of nouns, as the son of a father, or as the friend of a friend.107

Taken together, a keynote feature of Mizo interpersonal communication in the Lushai Hills was that personal names were seen less as simple, semiotic referents and more as actual verbal embodiments of the person — the signifier was the signified.108 This connection seems to have been taken literally: in one case, a Mizo man remembered first identifying as a Christian when “as a boy his Day School Teacher wrote his name down as a Christian.”109 If we attempt to turn towards this Mizo perspective where names are deeply significant, the missionaries’ requirement that the Mizo register their names upon seeking conversion — or the government’s myriad bureaucratic registers, or the grammars informing arriving officials and missionaries of phrases like “What is your name?” —becomes deeply imbued with meaning. It is highly likely that the missionaries employed Mizo terminology in their frequent references to the approaches of new potential converts who, in all the reports, “give their names”, “gave their names” or “have given their names” (all variants of the Mizo hming an pe) to become Christians.110 To “give” one’s name — indeed, one’s self — was likely for the Mizo an act of faith much more meaningful than even the missionaries ever realised.

The history of chibai played out against this backdrop of radically different interpersonal modes of communication. Upon the arrival of missionaries in the late nineteenth century, the word chibai featured in the chants and forest negotiations of the village puithiam, the complexities and nuances of which were disparaged by missionaries as mere “demon worship”. Once only an oral and aural word, chibai came to be written down in missionary writings with connotations of the English word “worship”. In the Gospel of John, the Christian worshippers (in spirit and in truth) are translated as chibai an buk (givers of chibai, or worship).111 With the reach of schools gradually expanding under missionary leadership, and with a tertiary economy opening to young Mizo graduates in the colonial bureaucracy, chibai accrued new meaning over the ensuing decade.

By 1914, the Mizo leh Vai Chan Chin Bu [Mizo and (Indic) Indian News] — a monthly government newspaper launched in 1903 to disseminate government rulings, district news and western knowledge in vernacular Mizo to an increasingly literate public — gave explicit guidance on new protocols of respect expected in interpersonal communication, particularly with regard to colonial government servants. A September 1914 article entitled “The New, Admirable Rules” pointed out that government employees and first-generation students in Aijal greeted one another, and asserted that this was an “admirable practice among the foreigners (Sap [British] and Vai [Indic Indians])”.112 The article informed villagers that the foreigners “appreciate it when we greet them”, and taught the new pleasantries such as khawngaih takin (if you please), ka lawm e (I thank you) and chibai (greetings) preferred by government officials and students, or the moderns of contemporary society.113

In another article, one Thangluaia (who was employed by the colonial government) urged villagers to show respect to government employees and to the Aijal students, for those in power would in turn help the villagers and not treat them badly.114 Mizo historian Lalpekhlua notes that, at this time, Mizo men who had once had long hair cut it, “put on long pants, and began to say, ‘Ka pu, chibai’ [Good Morning, Sir]”.115 In the context of a burgeoning vernacular print culture, and of the expectations of verbalised respect for colonial officials and a missionary-educated Mizo nouveau elite, the word chibai became publicly heard, its meaning fettered and exported through print, as the new and enduring personal greeting of the most modern people in the district, and of those villagers who wished to greet such people in hopes of being treated well by them.

Like an epoxy, through the twin injection of a missionary-controlled education system and a booming vernacular print culture, chibai seems to have spread, stabilised and crystallised. By 1922, missionary Kitty Lewis could write home that “everybody shakes hands in this country — people you meet casually on the road, and everybody else. They say ‘chibai’ …”.116 By the late 1930s, chibais were used in letters both as goodbyes and as fond hellos, in missives from Mizos in Serkawn to retired missionaries in Britain.117 The authoritative 1940 dictionary published by the missionary J. H. Lorrain included the stabilised chibai as a “salutation, greeting, or farewell, equivalent to Good Morning, Good Afternoon, Good Evening”.118 In a final coup evident only in visual sources, missionaries used “CHIBAI” signs to welcome Christian congregants to “Harvest Thank Offerings”, and indeed to the Mission Veng biak in itself — the very epicentre of church power in the North Lushai Hills.119 Once merely the specialised pidgin of village puithiams approaching forest spirits, a word unnoticed even by colonial grammarians, chibai was over a half-century co-opted and elevated literally to the front-piece of the missionaries’ flagship church, to the outset of all polite and modern conversation.

In a sense, the history of chibai parallels the history of hello, for both were elevated to their current prominence in part by technology — the early-twentieth-century rise of Mizo vernacular print culture for chibai, the late-nineteenth-century rise of the telephone for hello.120 But in the Lushai Hills, chibai also provided a malleable tool for the colonial import of several basic tenets of interpersonal communication: that one person greets another person, that one person asks another’s name, and that these exchanged names are inherently devoid of transcendental value. Only by approaching this photograph in context — and by leaving aside our modern, western assumptions about communication — can we see the extraordinary in what would otherwise just be a church welcome sign.

Harhna in the biak in

We could say that harhna was, for historical Mizos, the physically felt and enacted “sense” of being awakened spiritually — a process that manifested itself amidst the whole gamut of physical senses. Here, we stretch the term sense elastically, in an approach purposefully open-minded and sympathetic. Taking the supramundane sensory worlds of our subjects seriously can reward us with new insights into their subaltern pasts, even as it reminds us that we operate today in a world radically removed. Harhna, like the sense of hearing, was completely involuntary: just as Mizos had no earlids to block out unwanted sound, those with this “sensory” ability were unable to block out harhna. “To have the spirit” or “to receive the spirit” (thlarau chan) was to have harhna; “to not have the spirit”, “to quench the spirit” or to be “anti-spirit” was not to have it — the binary of this distinction closely paralleled those of sensory ability and disability, sighted or blind, hearing or deaf, tasting or ageusia.121 Harhna was often characterised as an involuntary moving under and of God’s spirit — something like a proprioception attuned to the supernatural. Translated, the term evokes “being awakened”, “enthusiasm” or, out of historical context and rendered in terms familiar to Mizo Christians today, “revival”.122

Around the time of this photograph, harhna was characterised by sensory overload, both of the person with harhna doing the sensing and of those around her or him. In contemporary missionary reports, those Mizos “with the spirit” engaged in “singing, dancing, quaking, swooning” and “trembling”; they “stiffened”, “stretched”, “shivered” and “fell”.123 In Welsh missionary eyes, such Mizos were “quite out of control”, as they practiced “singing, simultaneous prayer and dancing and jumping all the time”.124 As with the human senses of overwhelming physiological pain (nociception) or overwhelming heat (thermoception), harhna demanded an immediate physical response: Mizo church historian Lalsawma relates how the “whole body quaked and could be brought under control by no other means than dancing. […] Refusal to dance might result in pains in the head, throat, or stomach, or it might even turn to paralysis of the whole or parts of the body”.125 Contemporary observers highlight this compulsion as characteristic: “Those who danced did not merely dance because of a sense of joy but because they were shaking and could not but dance”.126

As with the other human senses, a distinct physical process appeared to be at work. As an odour might spread through a room, or the front of a cold wind blow across a city, so did it seem that the “quaking might pass to the one in the back row, and to the middle row, and then the corner” in contiguous fashion.127 For their part, Mizos seem to have valued those with “awakening” as uniquely spiritual guides, their special sense offering an uplink to another realm, not unlike the zawlnei — the women seers in their past. Missionaries complained that congregants often valued the words and revelations of those “that danced or jumped or fell in a swoon” (in other words, those attuned to harhna) more than the “words of the Scriptures or preacher or common sense”.128 Harhna was a credible sense to the Mizo, its revelations as physically real as, and arguably of greater import than, those of the biological senses.

The battle over harhna (over who sensed what from the spirit of God, how and in what sensory ways these revelations should be manifested) played out in the myriad texts of mission reports, in conflicts in meetings (as when Savidge screamed, “Stop dancing!”, during a meeting in Muallianpui village) and, turning to our photograph, apparently also in the layout of the mission’s most important church.129 By the time this photograph was taken, the lam tual was an important feature of most chapel architecture in the Lushai Hills — a central area made between the pulpit and the pews for a circle of processional dancing. However, the interior of the Mission Veng biak in, the centre of mission power pictured at the height of a wave of harhna in the Lushai Hills, is altogether unaccommodating. The placement of pews cannot have been accidental; from a contemporary Mizo perspective, they are “anti-spirit” and authoritative, crowding out both the quintessential Mizo sense of the movement of God’s spirit and any chance for the attendant dancing which was, as contemporary accounts suggest, a bodily reaction of self-preservation as innate as pulling away from a hot flame.

Conclusion: interpretation, method and visual sources of mission history

Historian Andrew J. May has rightly argued that by reading historical photographs alongside textual sources about often heavy-handed missionary demands for “moral compliance”, historians can discover codes of “indigenous symbolism and modes of resistance”.130 However, there is a danger that when historians attempt to recover, without explicit evidence, the motives of missionary photographers or the agency of the colonised from their camera’s “gaze”, they run the risk of imprisoning missionaries and missionised alike in their own interpretive frameworks or historiographical dogmas. Without explicit evidence, can we conclude that the blurry Mizo woman in Fig. 14.8 is resisting colonial power by exploiting the slow shutter speed of the missionary’s camera?131 Do the women in Fig. 14.9 necessarily assert agency by “denying the gaze” of the missionary’s camera?132

Fig. 14.8 “Some of the mothers who live in Lungleh”, c. 1938, loose photo in J. H. Lorrain’s file, BMS Acc. 250, Angus Library and Archive, Regent’s Park College, Oxford.

Fig. 14.9 Two Mizo nurses in Serkawn, c. 1924, British Library (EAP454/6/1), CC BY.

This chapter instead uses the historical mission photograph as a thinking cap. The material scarcity, wonder and feel of photography in the historical Lushai Hills might break down in the modern, supersaturated visual world from which historians must visit the historical Mizo. But we can seize on this breakdown as an opportunity, even pulling it on board as a methodological organising principle, gazing again and again at the same photograph. By simultaneously attending to the human sensorium in all its cultural and historical articulations, we take a human pulse in an historical moment of real, tumultuous and lived religious change.

Here, we move beyond the post-colonial critiques in mission studies that have focused on one-way cultural hegemony and conquest. These perspectives, while useful in shining the brightest light possible onto questions of subordination, can also wash out the complex collisions, contestations and, indeed, cooperations that arose in the mission field. In extreme cases indicative of a broader trend, we find modern post-colonial assertions that would have baffled their historical subjects, missionary or missionised. For instance, historian Emma Anderson claims that the “official purpose” of missionaries baptising converts was “rendering the exotic, dangerous ‘other’ familiar”; Christopher Herbert claims that missionaries taught converts to read simply as “a means of reordering the mind itself and putting it in thrall to new institutions”.133

Thinking with and making sense of photographs can help us move beyond clunky categorisations of domination to explore the many layers of cross-cultural action, reaction, discourse and everyday lived experience inherent in the missionary enterprise, landing us on the interesting “ambivalent ground between missionary versions of their roles and relationships with [locals], and the ways in which indigenous converts refashioned and subverted these expectations”.134 Extending goodwill and empathy to our historical subjects by endeavouring to approach them on their own sensory terms allows us to see old stories in new ways — “to see the strange as familiar so that the familiar appears strange”.135 Suddenly windows and wooden benches and gabled roofs are wholly astonishing. Unlocking a fuller research potential for mission photographs might just take a little less looking at photographs and a little more savouring of them.

References

Bynum, W. F., and Roy Porter, Medicine and the Five Senses (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

Chatterjee, Indrani, “Slaves, Souls, and Subjects in a South Asian Borderland”, paper presented at the Agrarian Studies Colloquium, Yale University, 14 September 2007.

—, Forgotten Friends: Monks, Marriages, and Memories of Northeast India (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

Classen, Constance, Worlds of Sense: Exploring the Senses in History and Across Cultures (London: Routledge, 1993).

Clossey, Luke, “Review of Emma Anderson, ‘The Betrayal of Faith’”, International History Review, 30 (2008), 828-29.

—, Salvation and Globalization in the Early Jesuit Missions (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

—, “Asia-Centered Approaches to the History of the Early Modern World: A Methodological Romp”, in Comparative Early Modernities: 1100-1800, ed. by David Porter (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), pp. 73-98.

—, and Nicholas Guyatt, “It’s a Small World After All: The Wider World in Historians’ Peripheral Vision”, Perspectives on History, 51/5 (May 2013), http://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/may-2013/its-a-small-world-after-all

Corbin, Alain, Village Bells: Sound and Meaning in the Nineteenth-Century French Countryside, trans. Martin Thom (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998).

Elias, Norbert, The History of Manners, Volume 1: The Civilizing Process, trans. by Edmund Jephcott (New York: Pantheon, 1982).

Feld, Steven, Sound and Sentiment: Birds, Weeping, Poetics, and Song in Kalui Expression (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1982).

Finlay, Robert, “Weaving the Rainbow: Visions of Colour in World History”, Journal of World History, 18/4 (2007), 383-431.

Fraser, Peter, Slavery on British Territory: Assam and Burma (Carnarvon: Evans, 1913).

Glover, Dorothy, Set on a Hill: The Record of Fifty Years in the Lushai County (London: Carey Press, 1944).

Grierson, George Abraham, ed., Linguistic Survey of India, Volume 1, Part 1: Introductory (Calcutta: Government of India, 1927).

Grimshaw, Patricia, and Andrew J. May, “Reappraisals of Mission History: An Introduction”, in Missionaries, Indigenous Peoples and Cultural Exchange, ed. by Patricia Grimshaw and Andrew J. May (Eastbourne: Sussex Academic Press, 2010), p. 96.

Hardiman, David, Missionaries and their Medicine: A Christian Modernity for Tribal India (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2008).

Harvey, Susan Ashbrook, Scenting Salvation: Ancient Christianity and the Olfactory Imagination (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2006).

Haudala, “A Lushai Pastor on Tour”, The Herald: The Monthly Magazine of the Baptist Missionary Society (London, 1916), pp. 61-64.

Heath, Joanna, “Lengkhawm Zai”: A Singing Tradition of Mizo Christianity in Northeast India (Master’s dissertation, Durham University, 2013).

Herbert, Christopher, Culture and Anomie: Ethnographic Imagination in the Nineteenth Century (Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press, 1991).

Hluna, J. V., Education and Missionaries in Mizoram (Guwahati: Spectrum, 1992).

Hminga, C. L., Christianity and the Lushai People: An Investigation of the Problem of Representing Basic Concepts of Christianity in the Language of the Lushai People (Master’s dissertation, University of Manchester, 1963).

Hoffer, Peter Charles, Sensory Worlds of Early America (Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press, 2003).

Howes, David, Sensual Relations: Engaging the Senses in Culture and Social Theory (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2003).

—, ed., Empire of the Senses: The Sensual Culture Reader (New York: Berg, 2005).

Jones, D. E., “Our New Mission: Touring in the South Lushai Hills”, The Missionary Herald, July 1904, pp. 340-43.

—, “The Report of the North Lushai Hills, 1923-1924”, in Reports of the Foreign Mission of the Presbyterian Church of Wales on Mizoram, 1894-1957, ed. by K. Thanzauva (Aijal: The Synod Literature and Publication Boards, 1997).

—, A Missionary’s Autobiography – D. E. Jones (Zosaphluia), trans. by J. M. Lloyd (Aijal: H. Liansailova, 1998).

Keay, John, India: A History (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2000).

Khilman, Sunil, The Idea of India (London: Penguin, 2012).

Kohn, Eduardo, How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology beyond the Human (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2013).

Kyles, David, Lorrain of the Lushais: Romance and Realism on the North-East Frontier of India (London: Stirling Tract Enterprise, 1944).

Lalpekhlua, L. H., A Study of Christology from a Tribal Perspective (Ph.D. thesis, University of Auckland, 2005).

Lalrinawma, Impact of Revivals on Mizo Christianity, 1935-1980 (Master’s dissertation, Serampore College, 1988).

Lalsawma, Revivals the Mizo Way (Mizoram: Lalsawma, 1994).

Lewin, T. H., Progressive Colloquial Exercises in the Lushai Dialect of the ‘Dzo’ or Kuki Language (Calcutta: Calcutta Central Press Company, 1874).

Lewis, Grace R., The Lushai Hills: The Story of the Lushai Pioneer Mission (London: Baptist Missionary Society, 1907).

Lloyd, John Meirion, On Every High Hill (Liverpool: Foreign Mission Office, 1952).

—, History of the Church in Mizoram: Harvest in the Hills (Aijal: Synod Publication Board, 1991).

Lorrain, J. H., Chan-chin tha Johana Ziak (London: British and Foreign Bible Society, 1898).

—, A Grammar and Dictionary of the Lushai Language (Shillong: Assam Secretariat Printing Office, 1898).

—, Dictionary of the Lushai Language (Calcutta: Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal, 1940).

—, “After Ten Years: Report for 1912 of the B.M.S. Mission in the South Lushai Hills, Assam”, reprinted in Reports by Missionaries of Baptist Missionary Society (B.M.S.), 1901-1938 (Serkawn: Mizoram Gospel Centenary Committee, 1993).

—, “Amidst Flowering Bamboos, Rats, and Famine: Report for 1912 of the B.M.S. Mission in the South Lushai Hills, Assam”, reprinted in Reports by Missionaries of Baptist Missionary Society (B.M.S.), 1901-1938 (Serkawn: Mizoram Gospel Centenary Committee, 1993).

May, Andrew J., Welsh Missionaries and British Imperialism: The Empire of Clouds in North-East India (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2012).

McKeown, Adam M., Melancholy Order: Asian Migration and the Globalization of Borders (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008).

Mendus, E. Lewis, “Editorial”, Kristian Tlangau, September 1932, p. 188.

—, The Diary of a Jungle Missionary (Liverpool: Foreign Mission Office, 1956).

Meyer, Birgit, Translating the Devil: Religion and Modernity Among the Ewe in Ghana (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1999).

Mintz, Sidney W., “Time, Sugar, and Sweetness”, in Food and Culture: A Reader, ed. by Carole Counihan and Penny Van Esterik (New York: Routledge, 2008), pp. 91-103.

Morris, John Hughes, The History of the Welsh Calvinistic Methodists’ Foreign Mission, to the End of the Year 1904 (Carnarvon: C. M. Book Room, 1910).

Pachuau, Joy L. K., “Sainghinga and His Times: Codifying Mizo Attire”, paper presented at the workshop History Through Photographs: Exploring the Visual Landscape of Northeast India, Delhi, 1 November 2013.

—, Being Mizo: Identity and Belonging in Northeast India (Oxford: Oxford University Press, forthcoming in 2015).

Queneau, Raymond, Exercices de style (Paris: Editions Gallimard, 1947).

Rath, Richard Cullen, How Early America Sounded (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005).

Rotter, Andrew J., “Empires of the Senses: How Seeing, Hearing, Smelling, Tasting, and Touching Shaped Imperial Encounters”, Diplomatic History, 35:1 (2011), 3-18.

Rowlands, E., English First Reader: Lushai Translation (Madras: SPCK Press, 1907).

Sangchema, H., “Revival Movement”, in Baptist Church of Mizoram Compendium: In Honour of BMS Mission in Mizoram, 1903-2003 (Serkawn: Centenary Committee, Baptist Church of Mizoram, 2003).

Savidge, F. W., “A Note from the Lushai Hills”, The Missionary Herald, 31 May 1910, p. 284.

Schafer, R. Murray, The Tuning of the World: Towards a Theory of Soundscape Design (New York: Destiny, 1977).

Schmidt, Leigh Eric, Hearing Things: Religion, Illusion, and the American Enlightenment (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000).

Scott, James C., The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009).

Shakespear, John, The Lushei-Kuki Clans (London: Macmillan, 1912).

Shaha, Brojo Nath, A Grammar of the Lushai Language (Calcutta: Bengal Secretariat Press, 1884).

Smith, Bruce R., The Acoustic World of Early Modern England (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1999).

Smith, Mark M., Listening to Nineteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2001).

—, How Race is Made: Slavery, Segregation, and the Senses (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2006).

—, Sensing the Past: Seeing, Hearing, Smelling, Tasting, and Touching in History (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007).

Thirumal, P., and C. Lalrozami, “On the Discursive and Material Context of the First Handwritten Lushai Newspaper ‘Mizo Chanchin Laishuih’, 1898”, Indian Economic & Social History Review, 47/3 (2010), 377-404.

Tlanghmingthanga, An Appraisal of the Eschatological Contents of Selected Mizo-Christian Songs with Special Reference to Their Significance for the Church in Mizoram (Master’s dissertation, Serampore College, 1995).

Vanlalchhuanawma, Christianity and Subaltern Culture: Revival Movement as a Cultural Response to Westernisation in Mizoram (Delhi: Indian Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 2006).

Way, G. A., Supplementary Report on the North-East Frontier of India (Simla: Government Central Branch Press, 1885).

Weiner, J. S., and R. E. van Heyningen, “Salt Losses of Men Working in Hot Environments”, British Journal of Industrial Medicine, 9 (1952), 56-64.

Zakim, Michael, Ready-Made Democracy: A History of Men’s Dress in the American Republic, 1760-1860 (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2003).

Zou, David Vumlallian, The Interaction of Print Culture, Identity and Language in Northeast India (Ph.D. thesis, Queen’s University, Belfast, 2007).

—, Bible Belt in Babel: Print, Identity and Gender in Colonial Mizoram (New Delhi: Sage, forthcoming in 2015).

Archival resources

“Annual Report on the Admin of the Lushai Hills, 1916-17”, Mizoram State Archives, Aijal, CB-18, G-219, n/p.

“Diary of Captain J. Shakespear for the year ending 17th October 1891”, India Office Records, British Library, London, Photo Eur 89/1.

“List showing the registers kept in the Sub-Divisional Office at Lungleh other than Treasury account book”, Mizoram State Archives, Aijal, CB-2, H-28, n/p.

“Mission Cottage at Aijal, blueprints by District Engineer, Lushai Hills”, 29 September 1905, Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru/National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth, CMA 27 300.

“Plan of Mission Bungalow, 1903”, The Angus Library and Archive, Regent’s Park College, Oxford, BMS Acc 250, Lushai Group IN/111.

“Some of the mothers who live in Lungleh”, loose photograph in J. H. Lorrain’s file, c. 1938, The Angus Library and Archive, Regent’s Park College, Oxford, BMS Acc. 250.

“The Story of Dara, Chief of Pukpui”, India Office Records, British Library, London, MSS Eur E361/4.

“Wives of the Soldiers in Lungleh”, loose photograph in J. H. Lorrain’s file, c. 1938, The Angus Library and Archive, Regent’s Park College, Oxford, BMS Acc. 250.

Buanga, H., “Old Lushai Remedies”, 13 June 1940, India Office Records, British Library, London, Mss Eur E361/24.

Chapman, E., clipping entitled “Day by Day in Darzo”, n/d, The Angus Library and Archive, Regent’s Park College, Oxford, IN/65.

Cole, H. W. G., “Standing Order No. 10 of 1909-10”, 19 July 1909, Mizoram State Archives, Aijal, CB-14, G-169.

Jones, D. E., “A Note on ‘The Revival’”, 24 April 1913, Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru/National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth, CMA 27 318.

Lorrain, J. H., “South Lushai”, Annual Reports of the BMS, 118th Annual Report, 1910, The Angus Library and Archive, Regent’s Park College, Oxford.

—, Logbook, Baptist Church of Mizoram Centennial Archive, Lunglei, Mizoram.

Mendus, E. L., “A Jungle Diary” draft, n/d, Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru/National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth, HZ1/3/46.

Parry, N. E., People and Places in Assam, n/d, Cambridge Centre of South Asian Studies Archive, Cambridge, Parry Papers, Microfilm Box 5, No. 40.

Scott, Lady Beatrix, “Indian Panorama”, Cambridge Centre of South Asian Studies Archive, Cambridge, Lady B. Scott Papers, Box 1.

Shakespear, John, “Extracts from Diary of the Superintendent of Lushai Hills”, 17 February 1895, Appendix No. 2, Mizoram State Archives, Aijal.

Woodthorpe, R. G., “The Lushai Country”, 1889, The Royal Geographical Society Manuscript Archive, London, mgX.291.1.

Archival letters

Challiana to Wilson, 27 January 1938, The Angus Library and Archive, Regent’s Park College, Oxford, IN/56.

E. A. Gait to the Secretary to the Government of India, “Proposals for the Administration of the Lushai Hills”, 17 July 1897, Mizoram State Archives, Aijal, CB-5, G-57.

Fraser to Williams, 10 March 1909, Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru/National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth, CMA 27 315.

Fraser to Williams, 11 July 1910, Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru/National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth, CMA 27 314.

Fraser to Williams, 25 September 1909, Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru/National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth, CMA 27 315.

Fraser to Williams, 28 March 1912, Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru/National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth, CMA 27 318.

Kitty Lewis to Mother and Father, 20 November 1922, Letters of Kitty Lewis to her Family, 1922-1923, J. M. Lloyd Archive, Aijal Theological College, Durtlang, Mizoram.

Kitty Lewis to Mother and Father, 27 April 1923, Letters of Kitty Lewis to her Family, 1922-1923, J. M. Lloyd Archive, Aijal Theological College, Durtlang, Mizoram.

Kitty Lewis to Parents, 22 November 1922, J. M. Lloyd Archive, Aijal Theological College, Durtlang, Mizoram.

J. H. Lorrain to J. Hezlett, 13 September 1913, Mizoram State Archives, Aijal, CB-16, G-204.

J. H. Lorrain to J. Hezlett, 19 November 1913, Mizoram State Archives, Aijal, CB-16, G-204.

Lorrain to Lewin, 16 October 1915, University of London Archives and Manuscripts, London, MS 811/IV/63.

John Shakespear to the Commissioner of the Chittagong Division, 14 August 1895, Mizoram State Archives, Aijal, CB-4, G-47.

Shakespear to McCall, 28 August 1938 India Office Records, British Library, London, Mss Eur 361/5.

Thu dik ziak ngama [One Who Dares to Write the Truth] to McCall, 26 December 1937, India Office Records, British Library, London, Mss Eur E361/20.

Interviews by the author

M. S. Dawngliana, Serkawn, Mizoram, 29 March 2014.

Joanna Heath, Aijal, Mizoram, 25 May 2014.

B. Lalthangliana, Aijal, trans. by Vanlalchhawna, 25 April 2006.

Thangliana, Mission Vengthlang, Mizoram, 16 May 2014.

H. Vanlalhruaia, Champhai, Mizoram, 22 June 2014.

1 I wish to thank Roberta Bivins, Luke Clossey, Lindy Jackson and Joy L. K. Pachuau for comments on an earlier draft.

2 R. Murray Schafer coined the term “soundscape” to refer to a “sonic environment”, the auditory equivalent of a landscape, in his seminal The Tuning of the World: Towards a Theory of Soundscape Design (New York: Destiny, 1977), pp. 274-75.

3 Haudala, “A Lushai Pastor on Tour”, The Herald: The Monthly Magazine of the Baptist Missionary Society (London, 1916), p. 63. All quoted editions of The Herald and The Missionary Herald were viewed in the Angus Library and Archive, Regent’s Park College, Oxford, UK (hereafter ALA).