15. The photographs of Baluev: capturing the “socialist transformation” of the Krasnoyarsk northern frontier, 1938-1939 1

© D. G. Anderson, M. S. Batashev and C. Campbell, CC BY http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0052.15

The craft of photography played an important role in the construction of early Soviet society. In western Europe and the Americas, the early Soviet period is associated with repressions and the blacking-out and forced amnesia of portraits and other representations.2 It is less known that photographers and photographic equipment were widespread, not only capturing faces for identity documents and staged, instructive scenes, but also giving glimpses of a new society and new subjectivities coming into being. The photographs of the period should not be read merely as superficial political instruments, although they were also undoubtedly used that way. We argue that some photographers, or at least some photographers some of the time, strove to capture the aspirations and tensions experienced by people living in rapidly changing times. To this end, we present a selection of photographs from a relatively unknown photographer who assembled a portfolio of images of everyday life in what was then a remote corner of the Soviet Union in the time of the great repressions and political dramas of the Stalinist period. In the photographs — which we have selected from what is a large archive — we demonstrate the difficult yet successful balance that this artist struck between documenting “topics” and depicting personalities.

Ivan Ivanovich Baluev was employed as a staff photographer at the Krasnoyarsk Territory Regional Museum (Krasnoiarskii Kraevoi Kraevedcheskii Muzei, or KKKM) through the worst of the Stalinist period, from 1934-1941. During this time, 1,951 of his images were added to the collection of the museum, illustrating a broad range of subjects from the industrialisation of the city of Krasnoyarsk to, more typically, the lives and living conditions of a variety of rural peoples across the vast central Siberian district where he worked. His name is usually cited in the tradition of realist ethnographic photography that was, for example, published by N. N. Nekhoroshev in the Turkestanskii al’bom, or associated with N. A. Charushin’s work in Zabaikal’e.3

Portions of Baluev’s mostly unpublished archive of fragile glass-plate negatives came to our attention only recently during a broader thematic research project, supported by the Endangered Archives Programme (EAP), to digitise and safely preserve a vast number of plate negatives featuring images of indigenous peoples across central Siberia.4 At that time we digitised, annotated and posted on the internet 297 examples of Baluev’s work on this topic plucked from the larger set, the existence of which we were for the most part unaware. His haunting images captured our attention and, indeed, at the end of the project his work emerged as by far the most prolific of any individual photographer on our stated topic. With the exception of a few images, his work has never been published or discussed in Russian or in English.

For the purposes of this discussion, we decided to focus on one particular chapter in his career — his participation in a nine-month expedition from 1938 to 1939, called the “Northern Expedition”, through some of the most remote regions of the central Siberian district (which is still known today as Krasnoyarsk Territory). Using the same equipment and skills provided by the EAP, we consulted, catalogued and digitised an additional 91 of his glass-plate negatives and catalogue annotations to produce what we assume to be a near-complete series of 711 images.5 Furthermore, we found and transcribed his diary of travels during the Northern Expedition.6 We also consulted and partially photographed a thin folder of archived reports and correspondence about the expedition, and consulted the scattered references in the secondary published literature on the expedition. Perhaps most ambitiously, we linked the photographs to diary entries — which was a Herculean task given the sometimes unhelpful ways that images are sorted and catalogued in Soviet-era museum archives. For a variety of reasons, the images and diary entries were linked by date and are quoted as such in this chapter.7 Our discussion further focuses on a four-month section of his travels between 7 November 1938 and 17 February 1939 for reasons we discuss below.

In this chapter we have decided to address what we call the documenting of “socialist transformation”, which is based on the somewhat loose translation of the headline term in the surviving documents of this expedition. What came to be known as the Northern Expedition was originally outfitted as the “Expedition [documenting] socialist construction [sotsialistcheskoe stroitel’stvo] in the North of Krasnoyarsk Territory”.8 The Soviet concept of stroitel’stvo, directly translated as “construction”, is an active concept which should be more accurately, but clumsily, translated as “building”. The term implies that a new socialist society is being erected in an empty space. While the northern taigas of central Siberia were undoubtedly thought to be more empty than most places in the Soviet Union at that time, the fact of the matter was that, even here, socialist society was by necessity reassembled from the already existing traditions, lifestyles and infrastructures of both indigenous dwellers and settler Russians in the region.

The “struggle” to build socialism was often commented upon at the time, and one of the goals of the expedition was to document for the KKKM those ways of life which were being replaced. We have therefore coined the term “socialist transformation” in order to represent the conflicted, ironic, but nonetheless creative way that many of Baluev’s photographs represent the old being turned into something new. Our argument is based on a selection of seventeen images which we find to be evocative of this theme during this particularly intense period in his life. In their own time, Baluev’s expeditionary images, although unpublished, were displayed in museum exhibitions, perhaps mixed in with the work of other photographers, perhaps on their own.9 This term represents, therefore, our attempt to use an early twenty-first century logic to look back on what has become a mythic time, to see if we can sense and touch elements of choice, insight and agency in circumstances that are thought to be dark with intrigue.

Our study has yet another goal in terms of trying to reach beyond stereotypes and myths to reveal people caught up in difficult processes. This archive helps us see through what might at first glance seem like the overwhelming “provincialism” of one man’s story, caught as it was in a network of relationships so very far away from Moscow and Leningrad, the so-called centres of political and cultural life. Baluev’s life and work seems ephemeral when set beside the relatively rich biographies of aristocrats and revolutionaries in the capital cities. This is why we tried to provide more detail about his life before he became a photographer and then after he left the museum. Similarly to what has been often done for the great figures of this time, we attempted to follow Baluev’s life through a trail of correspondence and reports in local newspapers.

While our attempts to find this material and to provide this global context are admittedly tentative and partial, what emerges in this study is a snapshot of the man as he was known by the museum which employed him. All the materials which we discovered on Baluev are in the personnel files, the manuscript collections or the photographic collections of the KKKM itself. After Baluev left the museum his trail vanished and faded from view. We do not know where or when he died, but again this is not uncommon in the traumatic period on the eve of World War II. This tale is therefore also the tale of an archive — a repository which has given us a brief bright window onto the life of a creative person. In the theoretical terms in which we have framed this chapter, early Soviet institutions not only transformed people but represented them, leaving us with material records of their lives which allow us to think through the events they experienced.

Ivan Ivanovich Baluev

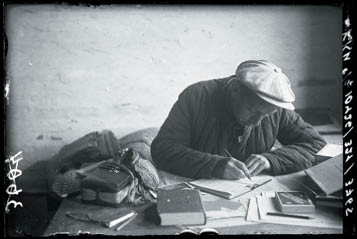

Baluev was in many ways a product of the Soviet project of social advancement (Fig. 15.1). In his Avtobiografiia — a standardised list of dates and events filed as part of his personnel records in the museum — he records that he was born into a peasant family in the village of Karatuz on 23 September 1905 (6 October 1905 NS) on the eve of the revolutions which would transform the Russian Empire.10 This village was a centre for the Yenisei Cossacks,11 and was one of the largest Cossack villages in the south of Yenisei province. After the October Revolution this social group would come to be labelled as suspect, due in part to their wealth as well as to the role that many Cossacks played in the civil war resisting Bolshevik power.

Fig. 15.1 Baluev writing in his journal in Dudinka, 1938.

© Krasnoyarsk Museum, Siberia (KKKM 3604), all rights reserved.

Baluev studied in the Karatuz local school and upon completion of his studies was trained as a photographer in the provincial capital Minusinsk between 1926 and 1928. He married Zinadia T. Toropova in 1928, and then went to work in the Rembrandt photographic company in the same city, most likely doing portraiture for private clients. In 1930 he tried to change careers by retraining as an accountant (ekonomist). However, due to a lack of money he was unable to finish his studies and took a job as a casual labourer. Between 1930 and 1931, he resumed photographing at the Slavgorod invalid commune. Again, it is not entirely clear what his duties were in the commune. These organisations were formed to help improve the lives of handicapped people through selling handicrafts or through repairing shoes or watches. It is possible that he took photographs to advertise the work of the organisation, or taught photography to the organisation’s clients. From 1931 to 1934, he became one of the main accountants in the Alma-Alta biochemical factory. While there are many details in his autobiography, it is silent on one point: it seems that his family was repressed. In a book documenting repressions in Krasnoyarsk, he and his wife are listed as victims of political repression along with his father, mother, brothers and sisters. According to this source, the entire family was exiled to Slavgorod.12

Baluev moved to Krasnoyarsk in 1934, possibly at the time that his exile was annulled. First he worked from 1934 to 1935 as a planner in the worker’s trade organisation KraRAIORS (Krasnoiarskii Raionnyi Otdel Rabochego Snabzheniia), and then as a planner in the Education Department. In the autumn of 1935, he returned to photography at the KKKM. His wife joined him there in the summer of 1938, also as a photographer, and they worked together until the war, at which point his fate is not clear. Baluev’s personal biography is only faintly outlined in the museum’s records. However, his brick home still stands in the city of Krasnoyarsk at number ten Oborony Street, and the world he saw through his camera is registered in hundreds of photographs.

Baluev’s photographic portfolio is archived by the KKKM, which in 2005 was a partner in the EAP project. The museum was founded in 1889 at the initiative of a group of intellectuals who wished to bring together objects and collections held in private hands.13 Between 1903 and 1920, it came under the sponsorship of the Krasnoyarsk section of the Eastern Siberian Division of the Russian Geographical Society, which outfitted many expeditions to outlying regions, greatly increasing its collections of objects and photographs. The work of the museum in this respect did not depart from the already widely-documented work of the Russian Geographical Society in this period.14 It would be fair to say that the majority of the collecting concerned the Turkic peoples to the south and the Tungusic peoples in the near north along the Angara River. Arctic collections were few and far between for reasons of distance, but also due to the fact that they were administered from different towns such as Eniseisk or Turukhansk.

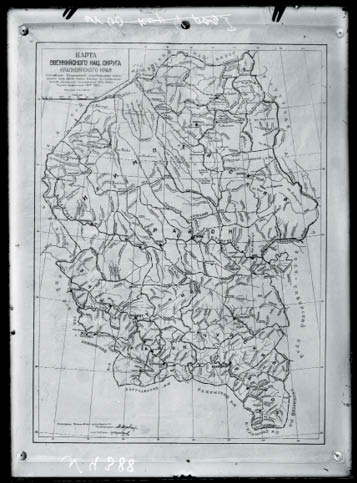

The Egyptian-style building in which the photographs are currently housed was designed between 1913 and 1914 and completed in 1930. In 1934, following the merging of former Tsarist-era territorial divisions, the museum came to be responsible for representing the entire territory of the newly-joined entities which made up Krasnoyarsk Territory (krai).15 This included the Evenki National District, the subject of most of the images analysed here (Fig. 15.2). From 1934 onwards, the KKKM was therefore given a new mandate to represent a regional territory that had in fact quadrupled through annexation to the north. It is within the context of this new Soviet mandate to depict a vast and newly acquired frontier that Baluev’s collection should be interpreted.

Fig. 15.2 Map of the Evenki National District. Photo by I. I. Baluev (EAP016/4/1/223). © Krasnoyarsk Museum, Siberia, all rights reserved.

Baluev’s contribution to the 1939 Northern Expedition is his most famous portfolio of work — 711 images taken across an enormous territory in difficult conditions. The images are still admired by local museum curators today for their clarity and honesty of composition. In 1937, prior to the expedition, Baluev contributed a set of photographs to the Khakas villages along the Chernyi lius, Belyi lius and Mana rivers. After the end of the expedition, Baluev made another 300 images for the museum. These include a 1940 photographic essay of the Sovrudnik gold mine in the North Yenisei district, another set of essays on three state farms in the northern part of the district and a 1941 photo essay on the Janus Darbs collective farm in Uiar district. In 1941 he was also asked to re-photograph (duplicate) a set of images of Stalin and Sverdlov, and a set of images of World War I. All of these collections are housed in the KKKM.

The Northern Expedition

The Northern Expedition of the Krasnoyarsk Territory Regional Museum (1938-1939) was organised by the famous ethnographer Boris Osipovich [Iosovich] Dolgikh,16 and led by the young communist party activist Mark Sergeevich Strulev (Fig. 15.3).17 The team travelled in the late autumn downstream from Krasnoyarsk to the mouth of the Yenisei River at Dudinka, on the last navigation before the winter set in. They then travelled overland across the southern portions of the vast continental peninsula of Taimyr using hired reindeer porters, and then southwards through the taiga interior of this territory back to Krasnoyarsk. The majority of the work took place in the Evenki National District. The expedition would encounter and document the lives of peoples known today as Enets, Nenets, Nganansan, Dolgan (Yakut) and Evenki, as well as local Russians.

Fig. 15.3 The first camp after crossing the border between Taimyr and Evenkia

with all three expedition members: Baluev, Dolgikh and Strulev.

© Krasnoyarsk Museum, Siberia (KKKM 3683), all rights reserved.

An expedition of Socialist discovery

The goals and styles of Northern Expedition fit within a long history of state-sponsored research on the lives and ethnography of northern peoples. To some degree, these surveys of indigenous dwellers did not differ in style from those conducted by great empires the world over. Travellers, be they Imperial-era Orthodox priests or Scottish geologists crossing the Canadian North, tended to note the difficulties of their journeys, the exoticness of the food and clothing, and the harshness of the taiga and tundra they travelled through. Russian ethnographic expeditions differed from those of other empires in one important sense: they surveyed a “near” frontier. The Russian Empire was inland and contiguous. Rather than travelling for weeks and months across oceans, most travellers already had a pre-formed impression of the people they were to encounter.18

Early Soviet expeditions adopted many of the time-tested techniques of earlier expeditions; there was, however, a distinct new quality — one of our co-authors has described it elsewhere as a spirit of “discovery”.19 Briefly put, if in the Imperial period there was always a consciousness that settler Russians were surrounded by non-Christian “alien” peoples (inorodtsy), these peoples were of little concern to the Russians busy with cultivating the taiga and building new settlements. After the Revolution and extended civil war, however, there was a new sense that all residents of the Soviet Union enjoyed a common citizenship and and that qualities once dismissed as cultural differences were now recognised as matters requiring improvement: hence the early Soviet-era battles against backwardness and illiteracy. Although northern Siberians had been in regular contact with Russians since the seventeenth century, this mid-twentieth-century expedition was nevertheless one of discovery, since these Soviet museum workers were travelling to encounter people and places in a new way. With reference to standard Soviet rhetoric and roles, they literally saw themselves as “pioneers”.20

The blending of older methods of expeditionary work with new assumptions can be best illustrated by two formal aspects of the expedition. As already mentioned, Baluev, Dolgikh and Strulev followed trails and roads which were already well-established. This autumn-winter clockwise expedition route from the Yenisei through the taiga had been followed routinely by state servants for the past half-century if not longer. Within the ethnographic literature we can compare the itineraries of the missionary Innokentyi Suslov in 1870,21 the Polar Census expedition led by Dolgikh in 1926 and 1927,22 and then two expeditions headed by Andrei A. Popov in 1930-1931 and 1936-1938.23 Dolgikh himself repeated the same route as a territorial formation worker, mapping the boundaries of newly-collectivised economic enterprises in 1934.24

Although the route was traditional and well-worn, the group travelled across the boundaries of the newly created socialist districts, and focused their attention in a different way. In the preliminary proposal for the expedition, Dolgikh stressed the importance of documenting the lives of the “new” administrative districts they would be visiting. The route was justified by the need to visit both the new Taimyr National District and the new Evenki National District.25 The window of entry across these “new” territories corresponded to deep winter (November-February) — this is the period of time that we focus upon almost exclusively in this article.

The material artefacts produced by the expedition also followed many of the standard protocols set up in the Imperial period. Roughly stated, the task of the Party-appointed leader Strulev was to collect statistical data on the population, much as his Orthodox predecessor Innokentyi Suslov might have counted pagan and Christian souls. However, in Strulev’s case, the task was to count people and animals collectivised into farms, and the numbers of indigenous people being trained for new occupations, which a nineteenth-century Orthodox priest would not have done.26 Dolgikh’s contribution was clearly aimed at the collection of folklore texts and genealogies, much like a nineteenth-century ethnologist, although as he would describe his work in his final report, the genealogies gave him insight not into an individual’s past, but into “the details of the historical development of one or another people”.27

Finally, Baluev’s task was to take images of people and landscapes using a type of camera which required careful choreographing, planning, posing and staging. The level of light and his equipment would have limited the angles he could choose and his opportunities for “spontaneous” portraiture. Therefore he worked within the constraints and guidelines of a nineteenth-century traveller working for the Russian Geographical Society.28 He nevertheless departed from the canon by photographing objects (usually structures) which represented institutions and by capturing new forms of association (usually represented as groups of people engaged in specific tasks), as we will describe in detail below.

The interweaving of old and new ways of life seems to have been part of a long process of negotiation. Indeed, the expedition was planned over a period of a year. In the summer of 1939, Dolgikh had just taken charge of the ethnographic “cabinet” of the museum, assigning himself the broad goal of documenting the “social and economic structure [stroi] of the people of the North of Krasnoyarsk Territory”.29 The term “structure” is misleading in the sense that what was meant was a process. The data that the team gathered — be they narratives, images or statistical tables — spoke not to how people saw themselves, but instead of their trajectories in space and time, from the past to the present, and from the present to the future. In the plan for the expedition, filed on 28 December 1937, Dolgikh listed the following subjects as important to describing these destinies. The intangible sense of what people were becoming is evident in the words “social development”, “extension”, “Sovietisation”, “dawn”, “transformation” and “movement”:30

- [Documenting] industrial development (the activities of the Main Administration of the Northern Sea Route and of Sevpoliarles [the state forestry company]);

- The activities of the Northern Sea Route Administration {in general}in {the exploitation of} the north of Krasnoyarsk Territory and in contributing to social development (transport, trade, scientific work and political enlightenment work, among others);

- The extension of agriculture into the north;

- The Sovietisation of the northern national districts;

- The dawn of cultural and primary school education among the peoples of the north;

- The {sedentarisation and} transformation of the lifestyle [byt] of the peoples of the north;

- The collective farm movement and the collective farms of the peoples of the north;

- A presentation of talented individuals among northern peoples;

- {Folklore};

- {History and Ethnography}.

We will return to this list in the next section when we analyse the types of images Baluev took.

The team was also guided by an official document from the People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs (NKVD) that provided a list of subjects to be photographed in the north.31 In this document, the Commissariat instructed them to photograph intangibles such as “further education of the population” or “the work of teachers liquidating illiteracy”, as well as tangibles such as industry, factories and collective farms. 32

An expedition in the time of “terror”

Knowing what we know today about the late 1930s in the Soviet Union, it is difficult to write about a scholarly or artistic endeavour as if it were an open-ended creative process. To this end, Baluev’s diaries and photographs offer us a unique opportunity to contextualise a time now remembered darkly. Both an earlier published account of this expedition33 and an unpublished report by our co-author Mikhail Batashev make a strong and convincing argument for how state terror provided a centrifugal inspiration for northern ethnography: people simply wanted to escape the epicentres of political intrigue and hide as far away as possible in the most remote corners of the Soviet Union. Such “little corners of freedom”, as historian Douglas Weiner has called them, became the places where ethnographic and artistic intuition were cultivated during these trying times.34

There is indeed a lot of evidence for this argument. Two of the participants in the expedition, Baluev and Dolgikh, had both suffered personally from the repressions. Baluev, as stated above, was forced into exile to support his parents, who had likely been exiled due to their family heritage. This experience probably gave him a certain shrewdness, and caution can be read in the passages of his diary which we quote below. The life history of Dolgikh is much better documented. With his long-standing interest in the lives and fate of indigenous taiga peoples, Dolgikh developed a critical attitude to the strict methods used to remove property from the rich. He voiced criticisms to others in a student dormitory in Moscow; his dissent was overheard and reported to the authorities. As a result, Dolgikh was expelled from university and exiled for four years, beginning in 1929, to the village of Krasnoiarovo on the Lena River in the northern part of Irkutsk province.35 Although it was at this time he was to write some of his better-known earlier work, and eventually gain a position in Krasnoyarsk as a museum ethnographer, it is likely that this experience bred in him an element of caution reflecting the stressful and dangerous times. It is perhaps noteworthy that, after his return from exile, Dolgikh legally changed his Jewish-sounding patronymic from Iosevich to the Russian sounding equivalent Osipovich. He is best known by the later middle initial and name.

According to Sergei Savoskul’s reading of the archival records, Dolgikh’s idea was to organise an expedition in the North, ostensibly to “diplomatically” investigate “socialist transformations”, but in reality to collect texts for the museum and to document the clan structure and ethnogenesis of northern peoples.36 The stated goal of the expedition, in Savoskul’s opinion, was a convenient mask for the actual work of ethnography, which was subversive to some degree. Despite Dolgikh’s role as the initiator of the expedition, Savoskul notes that a much younger and less experienced man, Strulev, was appointed expedition leader.37 Instead of having credentials as a seasoned traveller and a speaker of indigenous languages, Strulev was an approved Komsomol member who could be trusted to represent the expedition politically.

It is striking that there is not much sense of fear in the diaries of either Baluev or Dolgikh. True to form, Dolgikh’s manuscript diary seems obsessed with kinship terminology and structural debates over the evolution of indigenous native groups in this region. His manuscript report of the expedition is full of flow-charts showing how one clan group merges into another, eventually leading to the creation of distinct nations. This manuscript would anticipate his famous works on ethnogenesis.38 The dominant tropes in Baluev’s diary, which can be read in the excerpts selected below, are homesickness, frustration with working conditions and, interestingly, a sense of resistance to some of the tasks set before him.

In many places Baluev reveals a sense of caution and irony regarding the instructions given to him by his superior. In one of the strongest passages, which admittedly follows a rather gruelling trip in rough conditions, Baluev questions Strulev’s instructions to photograph a recently expropriated state enterprise.

January 24, 1939. At noon we arrived at a camp after having travelled fifty km At this camp I took a few photographs. While I was taking them it somehow entered the heads of my colleagues, and especially Mark Sergeevich [Strulev], to go to the Reindeer State Farm and photograph it. Nothing that I could say to the effect that photographing an immense quantity of reindeer under these conditions was pointless had any effect on the stubbornness of my boss. In order that nobody could ever say that I refused to photograph the State Farm I agreed to go. In the evening a worker from the State Farm escorted me […]

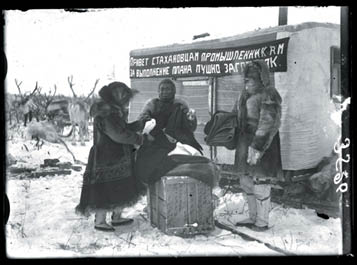

Elsewhere we can read his worry about the privileges of the political leadership vis-à-vis the workers he was documenting. In one incident, the team travels to a remote hunting camp to photograph the heroic Stakhanovite squirrel trappers who had exceeded their quota of animals hunted for the state (Fig. 15.4). Here, he represents the heroic workers almost as second-class citizens. After several days of illness, Baluev writes:

January 19, 1939. I woke in the middle of the night in terrible shape. The people inhabiting the rooms given to the Stakhanovites were the leaders of the Nomadic Soviet and the Simple Production Unit. The Stakhanovites themselves had collapsed on the dirty floor near the door. The leaders were sleeping on their beds.

Fig. 15.4 Stakhanovite hunter, Stepan N. Pankagir, on the hunt for squirrels.

Uchug, Evenki National District, 17 January 1939 (EAP016/4/1/1264).

© Krasnoyarsk Museum, Siberia, all rights reserved.

In other fragments of this late Stalinist description of everyday life we get a picture of the banal — of taking the opportunity to leaf through a newspaper when one finds it, to play the card game préférence, to enjoy sleeping late or to read a novel by Pushkin, Dostoevsky or Balzac that one might discover lying about even the most remote camp. The terror certainly disrupted lives and careers, but it also left space for mundane being in which certain routines, fascinations and relationships remained relatively stable. In viewing these photographs it is the impression of routine and stability that comes through most strongly.

Photographing northern transformations

The photographic archive of Ivan Baluev provides us with one of the more reliable insights into how a “socialist transformation” was perceived in 1939. The texts surviving from this time — full of calls to “enlightenment”, a “new dawn” and political inclusion — contain pointers to an implicit collective knowledge of what people hoped would come to be, but few clues as to what these transformations might look like. In the case of the indigenous peoples of Siberia, their lives were often framed as a “leap” from primitive communism to proper communism. All state and scholarly academic interactions with them reflected this aspiration.39 This article is one of the first published attempts to assess how photography participated in building this sense of transformation. After reviewing some of the technical challenges to making photographs in this sub-Arctic setting, we identify six transformational themes in the Baluev collection.

The creation of this collection of black and white glass plate negatives — ultimately gathered together as an archive — was in itself a difficult task requiring great discipline and inventiveness on the part of the photographer. The team travelled in open-air reindeer sledges and often spent their nights in tents. The fragile glass plates had to be protected from damage and mishap. While their vulnerability to damage was evident, the benefit of dry plate glass negatives was superior image quality and greater stability in cold conditions than flexible cellulose film, which would become brittle in low temperatures.40 Once exposed, the glass plates were often developed in the field — an effort that required preparing temperature-sensitive chemicals and having different equipment to hand. Finally, the photographer was burdened with heavy but fragile cameras, as well as cumbersome tripods.41

The photographic glass plates Baluev used were not unlike small windowpanes coated with a dried chemical solution that was extremely sensitive to light. The vast majority of negatives in the KKKM collection are 9 x 12 cm (roughly 4 x 5 inches). A box of negatives can be seen on the table in front of Baluev as he works on his journal (Fig. 15.1). Exposure to light outside the camera would render the chemical coating on the plates unusable, producing a negative that was uniformly black. To make his pictures, Baluev would have loaded each precious frame into a light-tight cartridge. These loaded cartridges would then have been stored in a box or leather pouch, ready for exposure. It is not clear how many cartridges the photographer would have had, though we estimate that it was not more than a dozen or so (commercially available pouches appear to have held five to ten cartridges).42

When his camera was ready, Baluev would load the cartridge into its interior, which did not admit any light whatsoever. Once in the camera, a cover was removed from the cartridge where the plate — opposite the camera’s lens — was ready for exposure. After taking measurements and adjusting the camera to let more or less light through the lens, and deciding upon the duration of the exposure, he would open the shutter for the selected exposure time. The cover of the cartridge was then re-inserted and the cartridge itself removed, placed in a pouch or box of cartridges containing exposed plates and saved until it could be developed in chemicals. If the plate was exposed to light prior to development, the image would be obliterated. Photographers until this time appear to have been technicians as much as they were artists. They learned their craft through a mixture of training, shop theory and experience.43

Baluev notes in his diary that he is using a “Compound” shutter.44 This style of shutter (also known as Kompur) was typically affixed to “Fotokor” cameras. The Fotokor (short for Photo Correspondent) was a highly portable rangefinder camera. It used a bellows system which collapsed into a small box. This kind of camera is referred to as a “folding bed plate camera”. In the portrait of Baluev where he is writing in his diary, you can see a case that is very similar in appearance to the kind used to hold these cameras when they are folded up. The Fotokor cameras were produced by GOMZ (Gosudarstvennyi Optiko-Mekhanicheskii Zavod/State Optical-Mechanical Factory) in Leningrad.45 The bellows and compartments in Baluev’s Kompound camera were no doubt brittle and stiff in the cold. Working with the plates and camera mechanisms must have been a great challenge with numb fingers. Nonetheless, Baluev produced hundreds of images both inside and out, in all conditions, even temperatures cold enough to freeze mercury — not to mention skin — upon exposure.

The process of developing the negatives required chemicals, water and a completely dark room or tent. Darkness in the long winter nights in northern Siberia was probably not difficult to come by. Indeed it was light that was more likely to be a concern. While daylight was critical for exposing the images, Baluev also had flash equipment and used magnesium powder for interior shots. By the 1930s the magnesium powder formula was so refined and the flash so quick that the photographer could take more or less candid shots in darkened spaces.46 According to his journals, he attempted to use available light whenever possible, implying perhaps that his magnesium stock was in short supply. The challenges of using this equipment in Arctic conditions are thoroughly documented in his diary:

7 November 1938, Kamen’. Today is the 21st anniversary of the October Revolution. I got up at 8.00, went outside, and an entire herd of reindeer ran up to me. I took some salt out of my bag and began to feed them. […] Today was a lightly cloudy day, and therefore it was difficult for me to make spontaneous [momental’nye] photographs. […] My camera froze and the shutter took exposures much longer than the meter was showing. […].

26 December 1938, Tura. I guess I have finally caught cold from all of these severe frosts [minus 48]. This evening I felt very poorly. My legs hurt and my head is beginning to hurt. The cold is creating ice fog which makes it impossible to take pictures outside. And now I am running out of photographic plates. Today I went around the village of Tura looking for replacement plates. The veterinarian has some, and he promised to give me a few. I wasn’t able to photograph anything today […].

29 December 1938, Tura. The cold is not particularly bad but it still does not allow me to do my work. I took a picture of the meteorological station and the post office. I am really fed up with Tura. And the worst is that it [the village] does not allow me to take any pictures. Also there is nowhere to develop the negatives because it is so cold. The room where we live is warm only when the stove is burning at full blast, and then only in that corner where the stove is sitting. If I developed the negatives then there would be no place to dry them. At night it is horribly cold in the room despite the fact that it is packed with people.

30 December 1938, Tura. My nerves are fraying from the fact that it is not possible to photograph the subjects that interest me. I can only take pictures inside and then with magnesium [magniia]. Today I took a picture of the cafeteria with the delegates of the Ilimpi region conference.

One surprising revelation of Baluev’s diaries is the balance between the difficulties of managing glass-plate photographic technology in the alien environment of the far north and the fact that photographic technology was apparently present nevertheless in every small corner of this northern frontier. Although Baluev complains of difficulties in replenishing his photographic stocks, it was not impossible. During his one-month stay in the village of Tura he came to distinguish local stocks of photographic plates by type and quality — at one point rejecting some plates held in the school and accepting a set from the government administration. There are numerous mentions in the diary of the fact that, as he moved southwards, the team was successful in procuring replacement stocks in other settlements. The 1930s may have been a time of strict political control, but Baluev’s diaries suggest that access to image-making technology was widespread in these communities.

One of the strongest themes in the Baluev collection is the representation of indigenous people in the setting of modern institutions. One finds photographs of young Evenki children learning to read, or of white-coated doctors examining Yakut patients. In other images we see representatives of the nomadic populations standing in front of newly-built structures or before machines. These compositions have a strong sense of irony to them. In most, the subject in the foreground, perhaps dressed in furs, contrasts strongly with the clean lines of a newly-hewn log building or a metal machine in the background. This sense of social distance is often amplified by the somewhat static pose adopted by the subject, who was undoubtedly asked to remain motionless for the rather long periods of time needed to take a photograph during the polar night.

Baluev’s representations of indigenous people applying themselves to study or tasks recall some of the guidelines published for ethnographical portraiture in the nineteenth century. In 1871, the Imperial Russian Geographical Society evaluated ethnographic portraiture as being different from physical anthropological portraiture in that it “opens up a wider field for the artistic inclinations of the photographer”. The society then provided a list of subjects and contexts:47

Of particular importance is the subject’s clothing, one or another of their typical poses, their weapons or other equipment [utvar], and equally [importantly], scenes which show how one or the other of these things are used. In addition [one should photograph] dwellings, cities, villages, riverine landscapes, scenes of public life, and specialised domestic animals.

These rules of thumb are clearly visible in most of the photographs selected here (see especially Figs. 15.3 and 15.6). However, Baluev’s work distinguishes itself from the late Imperial canon by what might be described as a photographic essay documenting particular enterprises or institutions such as a school, a collective farm, trading posts, or a hunting party (see especially Figs. 15.5, 15.8, 15.12 and 15.15). Here what nineteenth-century photography might describe as the habitual background is replaced with posters or backdrops revealing public scenes to be fully organised and contained by a particular institution. In these photographs we feel the force of another list, like the one written by Dolgikh and quoted above, demanding portraiture which captures “the dawn of […] primary school education” or “the collective farm movement”.48 To this end, Baluev brought with him particular skills, both technical and compositional. It would seem that his training in portraiture as well as his previous experience in working for small enterprises gave him the skills and the imagination to photograph something as intangible and fragmented as a “collective farm”.

The photographic conventions practised by Baluev presented a stable and recognisable world. His camera was oriented according to the horizon. His backgrounds were critical for the recognition of individuals. Architectural features were used to locate the viewer in space to help make sense of the scene. When he photographed people, he usually placed a clearly defined subject in the centre of the frame. Landscape photographs tended to be composed to maximise the perception of key features like rivers, cliffs, ridges and forest clearings. Pictorial representation as a conventional photographic technique dominated Baluev’s photography, which, unlike more revolutionary types of photography, was more concerned with documenting socialist transformation than formally instigating it.

What enlivens Baluev’s work on this topic is what we could perhaps define as an “aspirational” quality and what some readers might call propagandist. We would argue that the term propaganda is a heavy one, castigating more than it enlightens. The term implies that the visible engagement of subjects in the photographs is forced or somehow legislated in order to legitimate an unpopular policy goal. Although the late 1930s were over-determined by rather arbitrary policy goals, we must also bear in mind that many of the institutional public settings that Baluev photographed were new. They brought together people united by a particular skill set and class profile; they might have never worked together before. In that vein, these enterprises were experimental, organised with a sense of destiny or hope that they could improve the lives of people in a single state-constructed community.49 This intangible sense of aspiration — what we theorise here as a sense or feeling of transformation — is what comes across in Baluev’s photographs, and what may have made him a favourite photographer for commissions over a five-year period at the start of the Stalinist era.

Ironic Compositions

Fig. 15.5 Prize-winning hunter Ivan K. Solov’ev (a Yakut) shows his award to his wife. Next to her is V. V. Antsiferov. Kamen’ Factory, 7 November 1938 (EAP016/4/1/1913). © Krasnoyarsk Museum, Siberia, all rights reserved.

Moving beyond Baluev’s aspirational public photographs, we can also detect in this archive a set of images and notes-to-self in his diary which are ironic or perhaps even critical of what he was witnessing. A strong candidate for an ironic interpretation is a photograph of a ceremony in which a prize was given to a hunter (Fig. 15.5). Here we can clearly see a roll of wool fabric being presented to the Stakhanovite hunter who is identified in the attribution as Ivan Solovev; the date is specified as 7 November, Soviet Army Day. In the background there is a typical northern Taimyr Dolgan balok — a box-shaped caravan containing a stove, table, bed and belongings, designed to be pulled by a set of reindeer. Over the door a socialist banner celebrates the occasion. To the left, a woman and a man in fancy beaded clothing are offering the gift. The hunter receiving the present is standing in blindingly bright, newly tanned leggings and smoking a cigarette. While these ceremonies were part of the fabric of Soviet life, the Kamen’ group of Yakut-speaking Evenki hunters portrayed in this photograph were not particularly well-known for their loyalty to the Soviet project. Two years prior to Baluev taking this picture, kinsmen of those photographed incited a rebellion against collectivisation.50 Nevertheless, the photograph seems to denote stability, acquiescence and participation.

Counterpoising other photographs with Baluev’s diary entries shows a deeper conflict between Soviet expectations and local ways. There is, for example, an interesting set of photographs taken in late January in the Kataramba River region of Baikit district. Here two female squirrel hunters caught the eye of Baluev, and he took a photograph that was likely to illustrate gender parity within a productive trapping regime (Fig. 15.6).

Fig. 15.6 Female hunters. From the left, Mariia L. Mukto and Mariia F. Chapogir hunting for squirrels in the forest. Evenki National District, 1939 (EAP016/4/1/1323). © Krasnoyarsk Museum, Siberia, all rights reserved.

However this encounter was soon recorded in Baluev’s diary with puzzlement and disappointment at the productive logic of the region (Fig. 15.7):

Fig. 15.7 Icefishing with reindeer fat. Evenki National District, 1939.

© Krasnoyarsk Museum, Siberia (KKKM 3684), all rights reserved.

20 January 1939, Kataramba River. In the morning after having tea, I got to work. Here I found two women squirrel hunters, and took their picture. Around noon I travelled with the camp owner to go fishing. Among his fishing equipment I found a fishing lure that was not in any way alluring [nekliziuzhe]. It was like a branch that would likely frighten any fish set before it. At the end of the lure the fisherman set a huge cube of fat weighing about 25 grams. He threw it into the water, waited for half an hour and then decided that there were no fish. He then turned around and went back to the lodge. He tried to convince me that on this lure, the hook of which was as thick as an index finger, he catches fish. Fishing with such equipment is called khinda.

The passage reveals Baluev’s lack of faith in the traditional ecological knowledge of local Evenkis and his sense of knowing better than them how production should be organised. Reading this passage today, in an era when ideologies of production are not sacrosanct, allows us to interpret this encounter as a clash of worldviews. From the perspective of an average urban Russian of this time, the point of fishing would be to catch fish, with success being quantified and measured by the number of fish caught. Such a Russian would assume that fish would have to be lured into a fish trap or onto a hook.

However, within many northern indigenous cosmologies, including those of the Evenkis, animals are attributed with agency and are expected to come to hunters of their own will.51 Approaching the task from this point of view, a fisherman would not try to lure the fish onto a subtly concealed hook but instead strive to advertise his or her presence to give the fish an opportunity to present itself. If a fish did not turn up on the hook, it would mean that it did not want to provide itself for food, or “that there were no fish”. It is not entirely clear why Baluev took the time to comment on a fishing strategy that he found to be inefficient. He may have been expressing a frustration with the impossibility of the Soviet project that aimed at including all nationalities equally in a common economic project of building socialism.52 It would seem that here he notes the impossible distance between the utopia of a fully efficient productive society and the level of education of the citizens in this region.

Making boundaries real

As has been well-documented, a major aspect of Soviet modernisation was the inscription of more or less arbitrary boundaries and then the insistence that these boundaries had meaning in everyday life.53 Jurisdictional boundaries were made relevant by the fact that subsidies and opportunities flowed within them. The population was expected to receive their employment and the right to groceries, healthcare and education only within the orbits of specific regions. Within the new redistributional economy, families became tethered to these specific places so that it was difficult — if not impossible — to survive outside the spatial domains where one was registered.

While many of these compact civic domains were built upon existing patterns of trade and movement in the south, the north was quite different. Here local peoples, with their knowledge of how to identify subsistence resources as they moved and with their domesticated reindeer, were not necessarily tied to one particular place, although to claim that they were completely nomadic would also be an exaggeration. Engineers of socialism put a lot of energy into inscribing “national autonomous districts” across the river valleys and mountain escarpments of the northern part of Krasnoyarsk Territory where they had very little relevance.

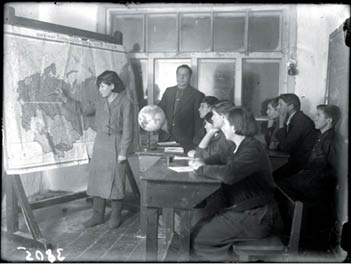

One consistent quality in Baluev’s work is his attempt to make these newly created districts appear solid and real. As Savoskul noted following his short survey of Baluev’s collection: Baluev had a remarkable interest in capturing geography lessons, in which children would follow these ephemeral boundaries with their fingers (Fig. 15.8).54

Fig. 15.8 Geography lesson in grade seven at the Russian School.

Evenkii National District, Tura Settlement, January 1939 (EAP016/4/1/1546).

© Krasnoyarsk Museum, Siberia, all rights reserved.

There are many such staged photographs taken in different parts of this vast region. One might add that Baluev also had an interest in maps. In many cases, he simply photographed paper maps wherever he found them — perhaps to help document the expedition, or to provide a reference copy for himself when he returned home (Fig. 15.2). It must be understood that these maps were undoubtedly rare, having been freshly printed, and that even the intellectuals in Krasnoyarsk might not be too sure where the boundaries of one district ended and another began.

One remarkable exercise, in which he invested a lot of effort, was photographing the exact place where one district turned into another. Baluev created an entire series of photographs attempting to document the division between the northerly Taimyr National District and its southern neighbour, the Evenki National District. On one photograph (Fig. 15.9), he notes with irony that the trapper Nikolai Nikloaevich Botulu, who traps from a collective farm within Taimyr, actually sets his deadfalls for Arctic foxes within the Evenki National District.

Fig. 15.9 The Yakut Nikolai N. Botulu (Katykhinskii) with a polar fox caught in the jaws of a trap. He was from Ezhova, Taimyr National District, but his traps were located in the Evenki National District, 1938 (EAP016/4/1/315).

© Krasnoyarsk Museum, Siberia, all rights reserved.

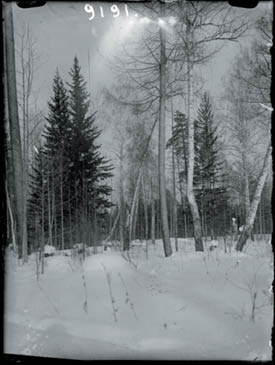

This comment draws attention to the arbitrariness of these divisions. On 9 February 1939, at another border, between Evenkia and Boguchan County, he desperately tries but fails to find the frontier among the trees (Fig. 15.10). He captures the same scene in his diary:

Today we crossed the border between Evenkia and Boguchan County. I had an idea to capture the exact place where the [National] District became a County, but neither my guide nor the people in the postal caravan we met on the road could give me an exact answer as to where the border was. I took a photograph of the place that B. I. [Boris Iosofich Dolgikh] indicated for me. We are now travelling in a mixed forest.

Fig. 15.10 Krasnoyarsk krai forest on the border of the Evenki National District, Boguchansk Region, February 1939 (EAP016/4/1/1646).

© Krasnoyarsk Museum, Siberia, all rights reserved.

Built structures

A second marked feature of the Baluev collection is the photographer’s attention to institutional architecture. In every named, populated place he made a concerted effort to photograph every government building and note the institution it held. If poor weather prevented him from taking photographs, he held the images in his head until the weather cleared, and then he would quickly “photograph the place”. Unfortunately, his diary does not give much insight into how he made his selection of what to photograph. It is tempting to conclude that Baluev was checking off either a formal or implicit list of all the institutions that made up Soviet civic order. In every named place we have photographs of schools, collective farms, nursing stations, boats and other vehicles, as if these were the architectural grammar from which a civilised place was constructed. His choice of objects is presented as self-evident:

3 January 1939, Tura. I tried today to photograph the village, but as with the previous days my efforts were not rewarded with success. […] The cold is the main thing that is freezing my work.

4 January 1939, Tura. In the evening I photographed students of Evenkia’s primary school in their school.

6 January 1939, Tura. At noon I walked around Tura glancing at interesting subjects to photograph, but it was impossible to photograph them since the fog was covering everything.

8 January 1939, Tura. The temperature rose to minus 38. The fog thinned and I took advantage of the opportunity to run around Tura to take a picture of whatever I could.

9 January 1939, Tura. I got up at 10.00 and after breakfast went to photograph [different] means of transport in Tura. Yesterday I made arrangements that all the automobiles and horses would be ready. The reindeer, to my great fortune, were standing in front of the School of Political Enlightenment [politprosvet shkola], although their antlers were unattractive [Fig. 15.11]. I dropped the idea of photographing the reindeer and instead went to the place where all the Tura vehicles are concentrated. After doing ‘the transport’ I went to the Fur Exchange [Fig. 15.12].

Fig. 15.11 Three modes of transport: reindeer, sleigh and truck. Evenki National District, Tura, 1939. © Krasnoyarsk Museum, Siberia (KKKM 3767), all rights reserved.

Fig. 15.12 Evenki hunter Danil V. Miroshko trading furs. The head of the exchange is Luka Pavlovich Shcherbakov. Tura, January 1939. © Krasnoyarsk Museum, Siberia (KKKM 3822), all rights reserved.

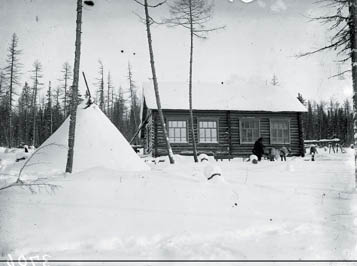

By documenting this architectural grammar, Baluev allows the viewer to think that even this remote corner of the Soviet Union has a familiar feel and function, just like every other corner. However, there are also points of resistance and even cynicism. We already cited above his dissatisfaction and sense of frustration towards Strulev, who diverted the expedition from their homeward journey to photograph the newly formed state farm (sovkhoz) at what is today Surinda (Figs. 15.13 and 15.14).

Fig. 15.13 A reindeer herd with herder from the Reindeer Sovkhoz (state farm), NKZ. Evenki National District, February 1939 (EAP016/4/1/1341).

© Krasnoyarsk Museum, Siberia, all rights reserved.

The same diary entry continues:

[It was] another 15km to the headquarters of the state farm. It was dark. I was terribly tired not having slept for two nights being on the road all the time. And now I was travelling again at night. The state farm reindeer were weak. They barely pulled us. […] The reindeer did not run in a straight line but would escape into the metre-deep snow, or the thick brush, and we would have to stop to retrieve our sleds. [… 25 January] I got up at 6.00, looked around the camp, dried my reindeer-skin leggings [bakhari] and ordered the men to harness the reindeer. […] I went around photographing what I could. This morning the sun reflected off the snow and burned our eyes. […] Taking pictures of reindeer is very clumsy.

Fig. 15.14 Headquarters for the Reindeer Sovkhoz (state farm), NKZ. A chum (conical tent) is in the foreground, a new home for Evenki labourers in the background.

© Krasnoyarsk Museum, Siberia (KKKM 3706), all rights reserved.

Here, aside from venting his dissatisfaction at the reality of travel in this region, Baluev indicates a dislike for collective subjects like reindeer herds — subjects of great scale and variety. This observation resonates with the character of his portfolio; with the exception of this one image, all of his other images feature a single building, a portrait or a rather strictly posed group of people. It seems that in his aesthetic view there were limits to the demands of state authorities on what should be photographed.

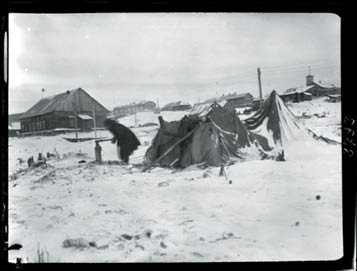

Within his chosen frame of the intimate subject, however, there was room for personal interest and visual juxtaposition. After filing dozens of photographs of imposing log structures with multiple smoking chimneys, he liked to add photographs of how modest people lived. One particularly striking image captures a hastily-constructed Yakut tent pitched in among the grid-like structures of the capital of the Evenki National District, Tura (Fig. 15.15).

Fig. 15.15 Yakut tent in Tura in the winter. Evenki National District, Tura settlement, January 1939 (EAP016/4/1/1556). © Krasnoyarsk Museum, Siberia, all rights reserved.

Reinvented traditions

Soviet transformation was often illustrated with depictions of rituals reinvented for a new era. In Baluev’s portfolio, a series of photographs portray the reconfiguration of a traditional Slavic New Year’s celebration as a “tree celebration” (elka). The entry in his diary seems to suggest that Baluev documented the celebration simply because at the darkest time of year it was difficult to take any pictures outside.

1 January 1939, Tura. Today we allowed ourselves to relax in our sleeping bags as long as we wished. We got up at 12 o’clock. It was a clear day, minus 51 degrees. Tura was sitting in clouds of steam and smoke. The visibility was not more than 70-100 sazhen. In the sky one could see that the sun was peeking up far away (but it didn’t warm us). By 2 o’clock there was the fog before the sunset and by 3 o’clock people were already lighting lamps in their flats. It is very boring. At 4pm the procurator came by to visit. […] at 7pm I photographed the New Year’s tree in the school.

Fig. 15.16 New Year’s tree celebration at the secondary school.

© Krasnoyarsk Museum, Siberia, (KKKM 3759), all rights reserved.

In Fig. 15.16, we see a group of children standing before the festive tree adorned in an array of costumes representing various nationalities (Cossack militiamen, Russian peasants and possibly Uzbeks), iconic labourers (such as a sailor), as well as animals from fairy tales (a fox or wolf, etc.). This looks like a relatively familiar spectacle of organised youth theatre in the winter holiday season. The Soviet New Year tradition eclipsed the old Orthodox Christmas, which was celebrated on 7 January. The festival culture of the officially atheist state was an important element in the production of everyday Soviet socialism that stripped old festivals of their religious symbolism and remade them as non-spiritual celebrations of human community and national patriotism. The costumes in this photograph appear to be part of a staged programme, perhaps in part celebrating the communist international — an aspirational community of happy communist nationalities. The calendric marker of the decorated tree and the masks demarcate a carnival time defined by collective celebration even at the most remote edges of the Soviet empire.

Conclusion

Although overtly focused on documenting Soviet futures, Baluev’s images from the Northern Expedition came, more often than not, to be consulted by historians, museum workers and anthropologists in an effort to document the vanishing past. The two enterprises are of course linked, since a view to the past can give an impression of the tremendous distance a society has travelled. Savoskul’s Russian-language overview of the Northern Expedition has done the most to document the way that Baluev’s images were circulated and cited. Savoskul’s interest in the development of the security state leads him to note that

[…] the photographs of I. I. Baluev even came to the need of the employees of the GULAG. In December of 1954, the Museum received a letter on the letterhead of the Political Division of the NKVD Noril’sk Labour Education Camp. It turned out that in preparation for the publication of a book celebrating the 25th anniversary of the Komsomol [the agency] was lacking photographic material on the life and living conditions of the ‘indigenous population of the Taimyr National District which was absolutely necessary to illustrate the introduction to the collection’.55

Baluev’s images began to circulate among anthropologists and museum workers, specialists in the representation of cultural traditions. In 1939, the Russian Ethnographic Museum requested copies of the material from the Northern Expedition, perhaps including photographs.56 A selection of his photographs was sent in 1941 to the Museum of Ethnography and Anthropology in Leningrad in order to enrich their collections on the native peoples of central Siberia.57 At least one public exhibit was organised in Krasnoyarsk from the materials of the Northern Expedition to illustrate “the progressiveness of Leninist-Stalinist Nationality policies in the backward regions of the USSR”.58 In all cases it was others who selected and circulated the images on Baluev’s behalf.

Although the use of these images to create a sense of distance from the past is quite understandable, we feel that it misrepresents the spirit of this collection. In this article we placed our emphasis on how this photographer tried to balance inherited styles of field photography, the difficult technical challenges of winter work in the sub-Arctic and a rather strict laundry-list of requisite topics with an element of intuition and style. We argue that this particular photographer during this troubled time felt limitations and saw opportunities, and that this comes out strongly in his images. For example, one of Baluev’s photographs was published in an early twenty-first century English-language monograph documenting the effects of the redistributive state on the psychology and ways of life of forest hunters (Fig. 15.17).59

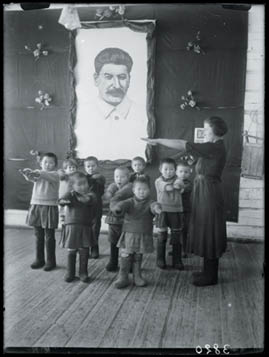

Fig. 15.17 Children performing exercises under a portrait of Stalin (a small portrait of the assassinated Bolshevik leader, Sergei Kirov, is behind the teacher’s head) (EAP016/4/1/1246). © Krasnoyarsk Museum, Siberia, all rights reserved.

This photograph, taken in the boarding school in Tura, portrays a group of young school children happily conducting their lessons under a gigantic image of Josef Stalin in the background. In the book it was selected to evoke a sinister Orwellian tone. However, when taken in context with the rest of the collection, the photograph was likely composed to illustrate a comforting form of social inclusion.60

This particular exercise also illustrates a human side to one of the more technocratic institutions of modern life — the archive itself. As we mentioned several times in this chapter, there are few social memories or material remains of the life and work of Baluev other than his photographs and the personnel files housed in the KKKM. Without the archive itself, and indeed without the intervention of the EAP, the vision and words of this artist might have disappeared. Just as his glass-plates provided a window onto vanishing lives, the archive has given us an important window onto Baluev’s work and life.61

References

Abramov, Georgi, “Etapy razvitiia otechesvennogo fotoapparatostroeniia”, http://www.photohistory.ru/index.php

Anderson, David Dzh., ed., Turukhanskaia ekspeditsiia pripoliarnoi perepisi: etnografiia i demografiia malochislennykh narodov Severa (Krasnoyarsk: Polikor, 2005).

Anderson, David G., “Turning Hunters into Herders: A Critical Examination of Soviet Development Policy among the Evenki of Southeastern Siberia”, Arctic, 44 (1991), 12-22.

—, Identity and Ecology in Arctic Siberia: The Number One Reindeer Brigade (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

—, “The Turukhansk Polar Census Expedition of 1926/27 at the Crossroads of Two Scientific Traditions”, Sibirica, 5 (2006), 24-61.

—, “First Contact as Real Contact: The 1926/27 Soviet Polar Census Expedition to Turukhansk Territory”, in Recreating First Contact: Expeditions, Anthropology and Popular Culture, ed. by Joshua A. Bell, Alison K. Brown and Robert J. Gordon (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 2013), pp. 72-89.

—, and Craig Campbell, “Picturing Central Siberia: The Digitization and Analysis of Early Twentieth-Century Central Siberian Photographic Collections”, Sibirica, 8 (2009), 1-42.

—, and Natalia Orekhova, “The Suslov Legacy: The Story of One Family’s Struggle with Shamanism”, Sibirica, 2 (2002), 88-112.

Anonymous, “Nastavleniia dlia zeliaiuschikh izgotovliat fotograficheskie snimki na polzu antropologii”, Izvestiia Imperatorskogo Russkego Geograficheskogo Obshestva, 8 (1872), 86-88.

Barkhatova, Elena, ed., A Portrait of Tsarist Russia: Unknown Photographs from the Soviet Archives (New York: Pantheon, 1989).

—, “Realism and Document: Photography as Fact”, in Photography in Russia 1840-1940, ed. by David Elliot (London: Thames and Hudson, 1992), pp. 41-50.

Bassin, Mark, Imperial Visions: Nationalist Imagination and Geographical Expansion in the Russian Far East, 1840-1865 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

Campbell, Craig, Agitating Images: Photography Against History in Indigenous Siberia (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2014).

Danileiko, V. A., “Gosudarstvennaia etnografiia, ili otrazhenie protsessa sotsialisticheskogo stroitel’stva na prieniseiskom Severe, v rabotakh etnografov kontsa 1930 gg. (k postanovke voprosa)”, in Vestnik Krasnoiarskogo gosudarstvennogo pedagogicheskogo universiteta im. V.P. Astaf’eva, ed. by N. I. Drozdov (Krasnoyarsk: Krasnoiarskskii Gosudarstvenii Pedogogicheskii Universitet im. V. P. Astaf’eva, 2011), pp. 122-27.

D’Encausse, Hélène Carrère, L’empire éclaté: La révolte des nations en URSS (Paris: Flammarion, 1978).

Diment, Galya, and Yuri Slezkine, Between Heaven and Hell: The Myth of Siberia in Russian Culture (New York: St. Martins, 1993).

Dolgikh, Boris Osipovich, Rodovoi i plemennoi sostav narodov Sibiri v XVII veke (Moskva: Nauka, 1960).

—, “Proiskhozhdenie dolgan”, in Sibirskii etnograficheskii sbornik, ed. by Boris Osipovich Dolgikh (Moskva: Nauka, 1963), pp. 92-141.

Fondahl, Gail, and Anna Anatol’evna Sirina, “Working Borders and Shifting Identities in the Russian Far North”, Geoforum, 34 (2003), 341-56.

Futorianskii, L. I., “Problemy kazachestva: raskazachivanie”, in Vestnik OGU, ed. by V. P. Kovelevskii (Orenburg: Orenburgskii gosudarstvenii universitet, 2002), pp. 43-53, http://vestnik.osu.ru/2002_2/8.pdf

Grimsted, Patricia Kennedy, “Lenin’s Archival Decree of 1918: The Bolshevik Legacy for Soviet Archival Theory and Practice”, The American Archivist, 45/4 (1982), 429-43.

Hallowell, A. Irving, “Ojibwa Ontology, Behaviour, and World View”, in Culture in History: Essays in Honour of Paul Radin, ed. by Stanley Diamond (New York: Columbia University Press, 1960).

Hirsch, Francine, Empire of Nations: Ethnographic Knowledge and the Making of the Soviet Union (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005).

Holquist, Peter, “From Estate to Ethnos: The Changing Nature of Cossack Identity in the Twentieth Century”, in Russia at a Crossroads: History, Memory and Political Practice, ed. by Nurit Schleifman (London: Frank Cass, 1998), pp. 89-124.

Iaroshevskaia, V. M., “Muzei vchera, segodnia, zavtra”, in Vek podvizhnichestva, ed. by V. I. Parmononova (Krasnoyarsk: Krasnoiarskoe knizhnoe izdatel’stvo, 1989), pp. 3-15.

Ingold, Tim, “From Trust to Domination: An Alternative History of Human-Animal Relations”, in Animals and Human Society: Changing Perspectives, ed. by Aubrey Manning and James Serpell (London: Routledge, 1994).

Jaubert, Alain, Le Commissariat aux Archives (Paris: Barrault, 1986).

Karlova, O. A., ed., Kniga pamiati zhertv politicheskikh repressii Krasnoiarskogo kraia (Krasnoyarsk: PIK Ofset, 2012).

King, David, The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin’s Russia, 1st edn. (New York: Metropolitan Books, 1997).

Kislitsyn, S. A., Gosudarstvo i raskazachivanie, 1917-1945 gg.: Uchebnoe posobie po speskursu, ed. by E. I. Dulimov (Rostov-na-Donu: Nauchno-issledovatel’skii tsentr kul’tury, istorii Dona im. E. N. Oskolova, 1996).

Kodak, “Photography Under Arctic Conditions”, October 1999, http://www.kodak.com/global/en/professional/support/techPubs/c9/c9.pdf

Kovalaschina, Elena, “The Historical and Cultural Ideals of the Siberian Oblastnichestvo”, Sibirica, 6 (2007), 87-119.

Kun, A. L, ed., Turkestanskii Alʹbom: po razporiazheniu Turkestanskogo general’nogo gumeratora K.P. fon Kaufman (Tashkent: n. pub., 1872), http://www.loc.gov/rr/print/coll/287_turkestan.html

Lavedrine, Bertrand, Michel Frizot, Jean-Paul Gandolfo and Sibylle Monod, Photographs of the Past: Process and Preservation, trans. by John P. McElhone (Los Angeles, CA: Getty Conservation Institute, 2009).

Marmyshev, A. V., and E. G. Eliseenko, “Grazhdanskaia voina v Eniseiskoi gubernii” (Krasnoyarsk: Verso, 2008).

Morozov, Sergei Aleksandrovich, Russkie puteshestvenniki-fotografi (Moskva: Gosudarstvennoe izdatel’stvo geograficheskoi literatury, 1953).

Newhall, Beaumont, The History of Photography, from 1839 to the Present Day (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1964).

Popov, Andrei Aleksanrovich, “Poezdka k dolganam”, Sovetskaia etnografiia, 3-4 (1931), 210-13.

—, “Iz otcheta o komandirovke k nganasanam ot Instituta Etnografii Akademii Nauk SSSR”, Sovetskaia etnografiia, 3 (1940), 76-95.

Ribalta, Jorge, ed., The Worker Photography Movement, 1926-1939: Essays and Documents (Madrid: Museo Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2011).

Savoskul, Sergei S., “Etnograf Krasnoiarskogo muzeia B. O. Dolgikh v 1937-1944 gg.”, Etnograficheskoe obozrenie, 1 (2009), 100-18.

—, “Vpervye na Severe: B. O. Dolgikh — registrator pripoliarnoi perepisi”, Etnograficheskoe obozrenie, 4 (2004), 126-47.

—, and David G. Anderson, “An Ethnographer’s Early Years: Boris Dolgikh as Enumerator for the 1926/27 Polar Census”, Polar Record, 41 (2005), 235-51.

Sergeev, Mikhail Alekseevich, ed. Nekapitalisticheskii put’ rasvitiia mal’ykh narodov Severa (Moskva: Nauka, 1955).

Slezkine, Yuri, Arctic Mirrors: Russia and the Small Peoples of the North (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1994).

Sonntag, Heather S., Genesis of the Turkestan Album 1871-1872: The Role of Russian Military Photography, Mapping, Albums and Exhibitions on Central Asia (doctoral thesis, University of Wisconsin, 2011).

Ssorin-Chaikov, Nikolai V., “Bear Skins and Macaroni: The Social Life of Things at the Margins of a Siberian State Collective”, in The Vanishing Rouble: Barter Networks and Non-Monetary Transactions in Post-Soviet Societies, ed. by Paul Seabright (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), pp. 345-61.

—, The Social Life of the State in Subarctic Siberia (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2003).

Suny, Ronald Grigor, and Terry Martin, A State of Nations: Empire and Nation-Making in the Age of Lenin and Stalin (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001).

Terletskii, Petr Evgen’evich, “Natsional’noe raionirovanie Krainego Severa”, Sovetskii Sever, 7/8 (1930), 5-29.

Trut, V. P., “Tragediia raskazachivaniia”, in Donskoi vremennik. God 2004-i: Kraevedcheskii al’manakh, ed. by L. A. Stavdaker (Rostov-on-Don: Donskaia gosudarstvennaia publichnaia biblioteka, 2004).

Uvachan, N., Perekhod k sotsializmu malykh narodov Severa (Moskva: Gosudarstvennoe izdatel’stvo politicheskoi literatury, 1958).

Vainshtein, S. I., “Sud’ba Borisa Osipovicha Dolgikh: cheloveka, grazhdanina, uchenogo”, in Repressirovannye etnografy, ed. by D. D. Tumarkin (Moskva: Vostochnaia Literatura, 1999), pp. 284-307.

Weiner, Douglas R., A Little Corner of Freedom: Russian Nature Protection from Stalin to Gorbachëv (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1999).

Wolf, Erika, “SSSR na stroike: From Constructivist Visions to Construction Sites”, in USSR in Construction: An Illustrated Exhibition Magazine, ed. by Petter Osterlund (Sundsvall: Fotomuseet Sundsvall, 2006).

—, “The Soviet Union: From Worker to Proletarian Photography”, in The Worker-Photography Movement, 1926-1939: Essays and Documents, ed. by Jorge Ribalta (Madrid: Museo Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2011), pp. 32-50.

Yurchak, Alexei, Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More: The Last Soviet Generation (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006).

Antsiferova, 1938.06.02. Spisok raboty po fotosnimki Krasnoiarskogo kraevogo muzei ekspeditsii eduiushie na Sever KKKM fond 1842 opis 1 delo 599 list 26.

Baluev, I. I., 1935.06.15. Avtobiografiia. KKKM-Nauchnyi arkhiv, opis 02 delo 44 list 2-3.

Baluev, I. I., 1941.5.12. Anketnyi list I. I. Balueva. KKKM-Nauchnyi arkhiv, opis 02 delo 44 list 11-12.

Baluev, I. I., 1938-39. Dnevnik ekspeditsii museia na Sever Krasnoiarskogo Kraia v 1938-1939. KKKM-Nauchnyi arkhiv, 7886 Pir 222 (in three separate notebooks).

Dolgikh, B., 1939. Predvaritel’nyi otchet etnografa Severnoi ekspeditsii Krasnoiarskgo kraevogo muzeia 1938-39 gg. KKKM, fond 1843, opis 1 delo 600 list 1-12.

Dolgikh, B., 1937.12.28. Plan ekspeditsii etnograficheskogo kabineta Krasn. Gos. Muzeiana 1938g Number p/n 1842, opis 01, delo 599, 4-5. Programma raboty ekspeditsii po sotsialistichekomu stroitelstvu Severa Krasnoiarskogo Kraia. KKKM, fond 1842, opis 1 delo 599 list 24-25.

Strulev, M. S., 1938. Materialy sotsstroitel’stva po Evenkiiskomu natsional’nomu okrugu. Statisticheskie dannye. KKKM, osnovnoi fond 7886/PIr 223.

1 In this chapter we employed a simplified version of the Library of Congress transliteration system without diacritics. In cases where there is a recognised standard English-language equivalent for a place or ethnonym (Krasnoyarsk, Yenisei River), we use this version in the text, but not in the references or citations.

2 Alain Jaubert, Le Commissariat aux archives (Paris: Barrault, 1986); and David King, The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin’s Russia (New York: Metropolitan, 1997).

3 On Nekhoroshev, see Heather S. Sonntag, Genesis of the Turkestan Album 1871-1872: The Role of Russian Military Photography, Mapping, Albums and Exhibitions on Central Asia (Ph.D thesis, University of Wisconsin, 2011); and A.L. Kun, editor Turkestanskii Alʹbom: po razporiazheniu Turkestanskogo general’nogo guberatora K.P. fon Kaufman (Tashkent: n. pub., 1872). On Charushin, see Sergei Aleksandrovich Morozov, Russkie puteshestvenniki-fotografi (Moskva: Gosudarstvennoe izdatel’stvo geograficheskoi literatury, 1953). pp. 38-40.

4 EAP016: Digitising the photographic archive of southern Siberian indigenous peoples, http://eap.bl.uk/database/overview_project.a4d?projID=EAP016. The digital images are available at http://eap.bl.uk/database/results.a4d?projID=EAP016

5 In this chapter, the glass-plate images digitised by the EAP are referenced with a two-part number which represents the box number within which they were found as well as their ordinal number with the box (EAP125-020). This is the reference which links to copies displayed online and held on microfilm in the British Library. The newly digitised images are referenced with a four digit number which is hand-written on the negatives and which corresponds to an older cataloguing system, now lost (KKKM 3604). We have no hard evidence to prove that the 711 images form a complete unbroken series since there is no archival record of how many images Baluev took; neither do the hand-written numbers consistently correspond to a series. We assert that the set must be more-or-less complete due to the fact that it would be hard to imagine Baluev carrying many more plates back to Krasnoyarsk. The older cataloguing system corresponds to a single-sentence description of the item which we have called an annotation. While it stands to reason that Baluev must have composed this annotation, we cannot be sure. It may have been another member of the expedition or indeed any other museum worker.

6 I. I. Baluev, “Dnevnik ekspeditsii museia na sever krasnoiarskogo kraia v 1938-1939”, KKKM-Nauchnyi arkhiv, 7886 Pir 222 (in three separate notebooks). The archived notebooks are not consistently paginated and all references herein are therefore by date.

7 In Soviet-era museum practice, collections are curated by topic, not by date or collector. Further inventory numbers are assigned sequentially to any object that is added to the collections and therefore do not necessarily sequence items in a particular collection. To add more complexity, inventory numbers are regularly redone and the records of the previous inventory discarded. Baluev’s images were re-numbered thrice (and for the EAP a fourth time). It is extremely difficult to see a logic in the older numbering system. Indeed, our EAP system was also topical and not universal. For this article we reassembled the entire collection according to date by linking the images to the diary by their attributions, in many cases by viewing the images and making a judgement as to which place or nationality was represented, and then often arranging the images in order by one or another of the older numeric codes. We cannot be sure that we have reconstructed the exact sequence of photographs, but we are confident that we sorted most photographs accurately by date, place and subject.

8 In Russian: “Ekspeditsiia po sotsialistichekomu stroitelstvu Severa Krasnoiarskogo Kraia”. B. Dolgikh, 1937.12.28, “Plan ekspeditsii etnograficheskogo kabineta Krasn., Gos. Muz., 1938g” p/n 1842, op. 01, d. 599, ll. 4-5; and idem, “Programma raboty ekspeditsii po sotsialisticheskomu stroitelstvu Severa Krasnoiarskogo Kraia”, KKKM, f.1842 op. 1 d. 599, ll. 24-25. All translations are ours, unless otherwise stated.