16. Archiving a Cameroonian photographic studio

© David Zeitlyn, CC BY http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0052.16

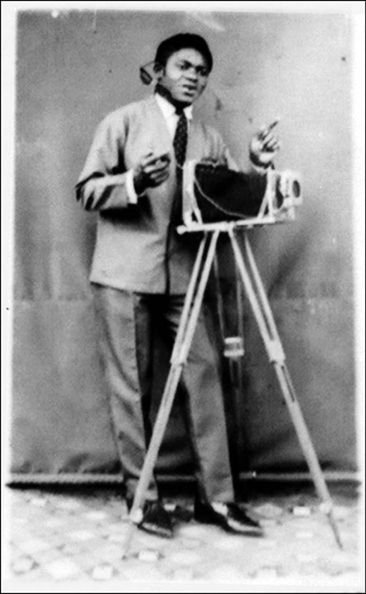

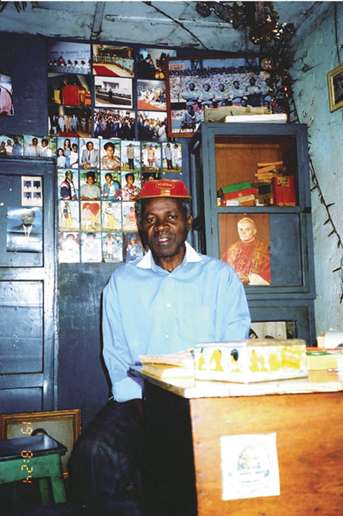

In 2005, I helped to organise an exhibition of the work of Joseph Chila and Samuel Finlak, two Cameroonian studio photographers, at the National Portrait Gallery, London.1 This arose from my then twenty-year involvement as a social anthropologist working in Cameroon. Chila later introduced me to his “patron”, Jacques Toussele, who had taught him photography in the early 1960s (Figs. 16.1-16.4). Together we made several visits to “Photo Jacques” in Mbouda, Western Province, and I was shown the pile of boxes containing what I now know to be approximately 45,000 medium format negatives and some uncollected prints: the legacy of Toussele’s forty-year career.2 The collection is an unparalleled archive of local photographic practices spanning several decades. Among the negative archives of the studios, as well as administrative (identity) photographs, we found marriage photographs, family groups, new babies and young couples. Others mark funerals and in some cases illness. Road traffic accidents and buildings under construction are among the other types of image.

With the help of the British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme (EAP), the negatives have been scanned and catalogued.3 This was the first step in ensuring their long-term survival and making them available for a wide range of different research purposes to scholars in Cameroon and elsewhere. I prepared an application to the EAP after discussing the possibility with Toussele, who was bleak about the prospects for black-and-white photography. The archive project gave him and his photographs a new lease of life as well as the hope of a renewed income. At the time of writing in 2014, the negatives remain in Toussele’s personal possession, and thus the archival story has not yet finished. The project is unlike cases of “digital repatriation” in that the images never left Cameroon; however, most Cameroonians, even in the Mbouda area, had and have no idea that the negatives survive. Therefore, digitisation will open the collection to wider access in the longer term, with parallels to some of the earlier “repatriation” projects such as Digital Himalaya.4

Fig. 16.1 Jacques Toussele with a plate camera in 1965.

© Jacques Toussele, CC BY-NC-ND.

Fig. 16.2 Jacques Toussele in 2001. Photo by author, CC BY-NC-ND.

More than a bare collection of negatives, Toussele’s photographs offer a rare archive of local photographic practices, now documented with his assistance (Toussele still lives in the community where these photographs were taken). In its relative completeness and range of subject matter, the archive provides a way of contextualising the work of the few internationally famous African photographers. For all their achievements, we should not let Seydou Keïta, Malick Sidibé and a few others stand for the whole of Africa.5

Since its pioneering work began in the late 1970s,6 there has been an explosion of both art historical and anthropological interest in African photography. Exhibitions such as In/Sight at the Guggenheim, New York in 1996, and similar displays in Paris and the United Kingdom, are the proof.7 Several books published in the 1990s attest to widening interest among art historians and other researchers in non-western photography. For example, Christopher Pinney discussed colonial and Indian influences on image-making in India, while Deborah Poole considered ideas of race and image in the Andes; Elizabeth Edwards provided an overview of the uses of anthropological photographs soon after.8 The publications of the 1990s represent the beginning of a true art history of African photography. This research continues to examine the social roles that photographs play and the different ways in which they can be studied.9

The cultural context of photography in Cameroon

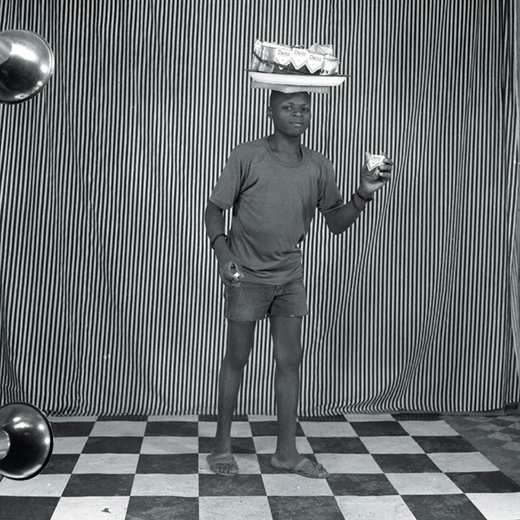

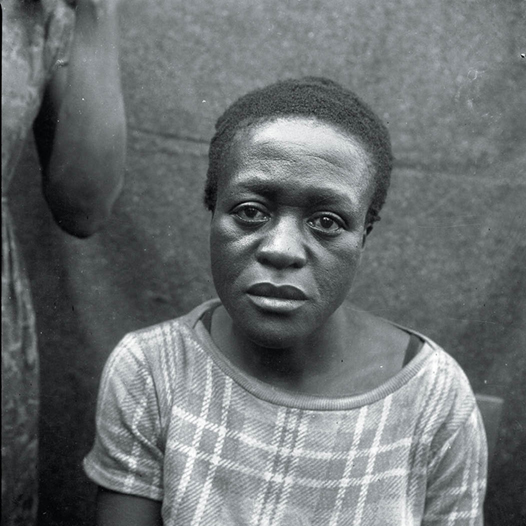

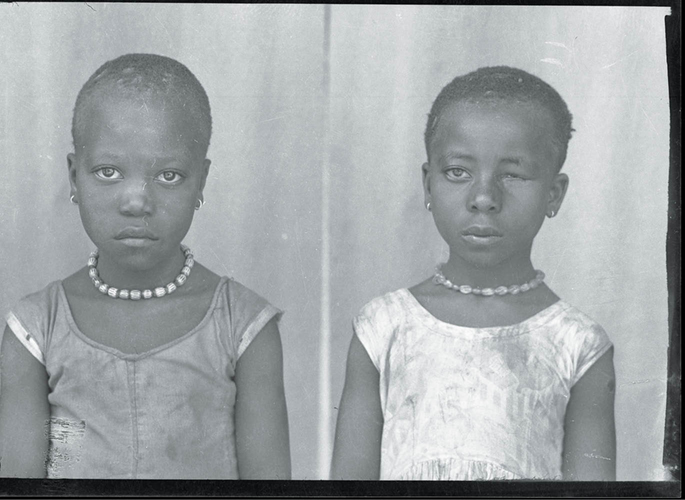

Professional black-and-white photography in Cameroon had been under threat from colour since the 1980s. Following the introduction of new identity cards in 1998, it has now all but disappeared. The cards were issued complete with instant photographs, removing the need for black-and-white, 4cm by 4cm “passport photographs” (Figs. 16.5 and 16.8-16.9). Such black-and-white “wet photography” had meant that images could be produced easily without much technology or infrastructure (whereas printing colour images, whether film or digital, requires more complex and expensive equipment). Rural photographers could process and print the film without access to electricity. Throughout West Africa, therefore, a small supporting industry of photographers (whose ranks included Sidibé, Augustt and Keïta, mentioned above) has effectively been destroyed by the computerisation of national identity cards and the arrival of cheaper 35mm colour processing in the cities. Toussele is among many such photographers to have lost their livelihoods in Cameroon.

Although these photographers were sustained by administrative requirements (for example, the need for ID photographs), such requirements did not fully determine the kinds of images they could take. Bureaucratic demands provided a secure economic basis for the studios and rendered the cost of other photographs affordable for clients (Figs. 16.5 and 16.17).

Fig. 16.3 The studio in 1973 (EAP054/1/123/56).

© Jacques Toussele, CC BY-NC-ND.

Fig. 16.4 The studio building in 2006. Photo by author, CC BY-NC-ND.

Fig. 16.5 A street seller (EAP054/1/54/58). © Jacques Toussele, CC BY-NC-ND.

Fig. 16.6 Portrait for an ID card (EAP054/1/94/167). © Jacques Toussele, CC BY-NC-ND.

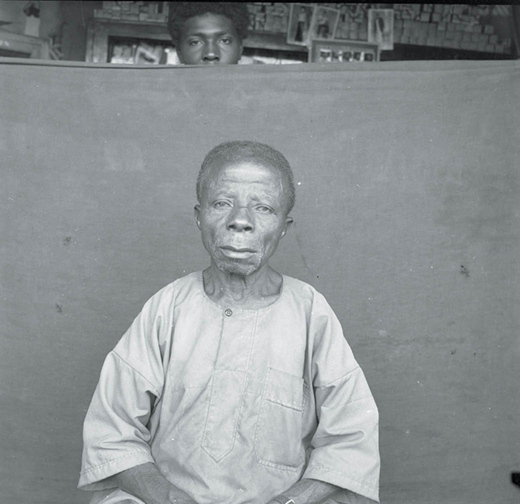

Fig. 16.7 Portrait of an elderly man with spear and pipe (EAP054/1/68/125).

© Jacques Toussele, CC BY-NC-ND.

Fig. 16.8 Portrait for an ID card (EAP054/1/177/24). © Jacques Toussele, CC BY-NC-ND.

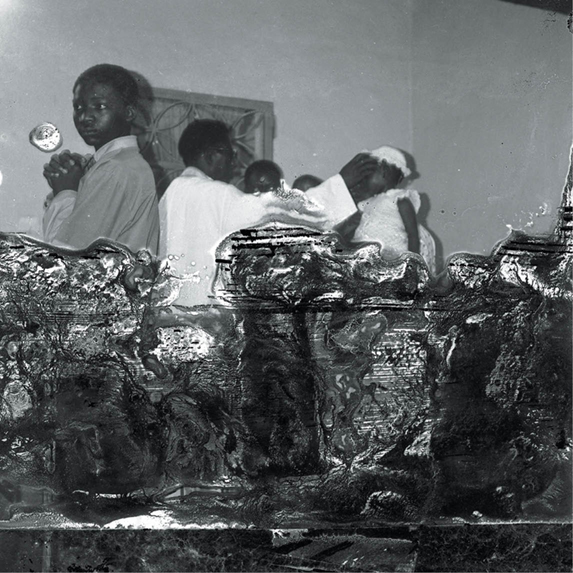

Fig. 16.9 Portraits for school ID cards. Double exposure on a single negative (EAP054/1/52/144). © Jacques Toussele, CC BY-NC-ND.

To give a more concrete idea of the relative frequency of the different kinds of photographs found in the archive, just over half of the total of 46,504 are passport-style photographs for national identity cards. Recreational images include many groups of family or friends (3,522 images contain more than two people) as well as photographs of babies. I note that there are almost as many images of road traffic accidents (191) as there are of weddings (212). There are also a small number of photographs taken in hospital showing bandaged patients recovering after surgery. I have done other such counts with Cameroonian contemporaries of Toussele, and the relative percentages are similar.10

It must also be noted that even identity card photographs are of considerable research interest, especially when one examines the entire negative and not just the head and shoulders which were printed for the passport-style image. This raises a host of problems and issues about representation and analysis (by whom and of what) which, to my mind, gives this project a dynamic tension. The analysis of individual photographs or groups of photographs are problematic in many different senses. They are transformed by being archived and viewed as part of “a collection” in, variously, the Cameroon national archives, the university archives or a photographer’s shop.11 There is a dynamic of appropriation, not only by the researcher but by the state and the photographer as well — for older identity card photos, the negatives were left with commercial photographers or the sitters (see below). Now that identity cards are digitised, there are no negatives and only government representatives can make and “own” these important images. There is no longer the possibility of reusing them for other non-bureaucratic purposes.

Between client and photographer a delicate negotiation, often unspoken, took place about props, backcloth and pose. The photographers I have interviewed are insistent that although they made suggestions and delicate adjustments, the choices of poses and props were made by the clients.12 Many different conventions become visible when one compares images of similar categories taken by different photographers. In other papers I discuss some of the tropes at play, but here I am concerned more with the archival side of the project.13

Uses of photographs

The images had many uses and these often changed over time. If the single most common reason for commissioning a photograph from one of the studio photographers was to get a passport-style print for the national identity card (or school cards for secondary school pupils), then there were also many casual or recreational uses. Photographs of families, babies, weddings and friends were taken for display, storage or discussion when albums were passed around.14 Weddings, funerals, official meetings, hospital treatments and traffic accidents are among the different sorts of images found in photographers’ collections of negatives.

In some cases, a single print or image could serve different purposes over time: the ID photos of the elderly are in many cases the only surviving photographs of grandparents. After a death, the identity card may be copied for an enlarged print to be displayed on the wall. Such photographs are also on show in funerary celebrations, the so-called “cry-dies” which are widespread in west Cameroon.15 Photographs were sent by villagers to relatives in town (e.g. for secondary education). Those at school together in the towns exchanged photographs before they graduated and scattered, some returning to their villages of origin, others moving to other cities in search of employment.

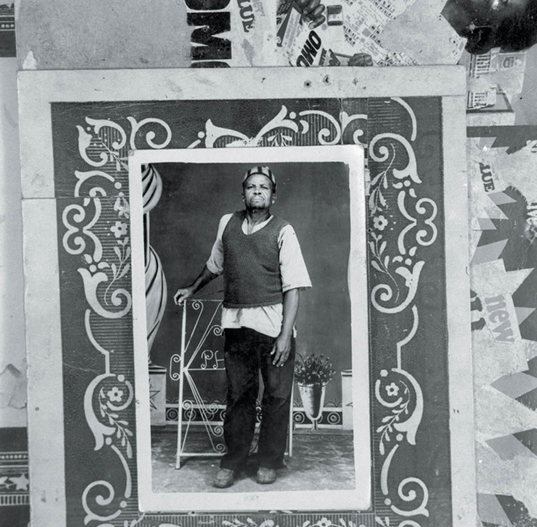

Sometimes prints were brought back to the studio to be copied (in literal photocopies). Where these were Jacques’ own work, we can sometimes compare the original negative with the copy of the original print. This comparison can reveal a great deal about his dark-room practices, and about the ways in which the negatives (which were scanned full-frame) were actually used to create prints.

Fig. 16.10 A photocopy of a print of a man standing, showing how the original negative was cropped (EAP054/1/4/145). © Jacques Toussele, CC BY-NC-ND.

Fig. 16.11 Original negative for the print shown in Fig. 16.10 (EAP054/1/50/562).

© Jacques Toussele, CC BY-NC-ND.

Copyrights and permissions

The convention among studio photographers in Cameroon (and elsewhere in West Africa) was a two-tier pricing structure. Clients paid a certain amount per print but had to make an additional payment if they wanted the negative as well. The archiving project is therefore strictly concerned with the negatives the clients chose not to redeem. Moreover, it is impossible to get permission from the people who commissioned the photographs: Toussele did not keep records of his clients, hence we have no means of contacting them. As is conventional in photographic copyright law, the assumption is that the owner of the negative holds the copyright, and this has been reserved by Toussele. He signed a licence with the EAP allowing the negatives to be scanned and the scans to be distributed for non-commercial purposes only. All commercial rights are reserved by him, and the London-based charity, Autograph ABP, are acting as his commercial agents.

Vulnerability

Until our project began, Toussele’s collection was vulnerable.16 It was stored in a back room of the studio under a leaking roof. When I opened several boxes at random they showed signs of deterioration and damage — some negatives had stuck together (Figs. 16.12 and 16.13). The negatives are of medium format and mainly high quality (good contrast and well-fixed). Many were very dusty and had suffered from the damp; it was necessary to wash them before copying. This work was undertaken by Emmanuel Noupembong, a former apprentice of Toussele who had recently retired from service as a photographer for the Cameroonian government.

Toussele is ageing and not in the best of health. He collaborated with the project team of four people to provide basic documentation. He was also able to recognise some of the people in the photographs, enabling future research to be undertaken and thus greatly enhancing the importance of the archive. However, it should be noted that recognising someone is not the same as knowing their name — often all we could record was that this person came from that village.

Nonetheless, it is anticipated that the archive will enable scholars to raise a wide range of issues about the presentation of self, changing fashions and global patterns of influence as mediated by local norms of appropriate behaviour in public. An example might be the influence of magazines such as Vogue and Paris Match which in the 1970s led some young women to be photographed in daring mini-dresses, and some men to be pictured parading in trousers known locally as “patte d’éléphant” (“elephant’s foot”), the widest of flares. The Toussele archive permits a systematic examination of modes of displaying “modernity” and of being fashionable. I look forward to a new generation of African historians and scholars exploring the archive in ways I cannot imagine.

Fig. 16.12 Baptism. Damaged negative (EAP054/1/44/45).

© Jacques Toussele, CC BY-NC-ND.

Fig. 16.13 Negatives before scanning. Photo by author, CC BY-NC-ND.

Archival realities

Originally it was proposed to use digital SLR cameras to copy the negatives, but further consultation and testing persuaded me that higher quality could be achieved with dedicated negative scanners. Moreover, during the initial phase of the project an Epson scanner was available which could scan direct to a memory card without an intermediary computer. It was originally planned that Toussele and Chila would copy the collection, but this proved impossible in practice. Between the application’s submission and its acceptance, the owner of the studio building in Mbouda decided to redevelop, and so Toussele was given notice to quit by his landlord. My arrival was fortuitous, and I was able to help him clear out the studio. In the end, the negatives were temporarily taken from the studio to the British Council Library in Yaoundé, where they were scanned by an operator trained specifically for the project.

After scanning, the memory cards were used to make duplicate DVDs in a standalone burner. Of the DVDs, one went to the British Library where it was eventually made available online, and the other went back to Toussele so that he has his own set of the scans. A Cameroonian coordinator made prints from the DVDs on an ordinary laser printer; these were then sent with data forms back to Mbouda, where a small team worked with Toussele to produce basic documentation of the images (Fig. 16.14). The results were typed up in a database (the basis of the archive’s catalogue).

Fig. 16.14 The documentary team at work in Mbouda.

Photo by author, CC BY-NC-ND.

The project produced a reference digital archive, licensed for free educational use, based on the surviving negatives and reference prints in Toussele’s studio.17 Copies on hard drives were deposited at the National Archives in Yaoundé (which supported the project from the outset), at the University of Dschang (which is the nearest university to Mbouda), and at the University of Ngaoundéré (which already has experience of archiving digital photographs through its collaboration with the University of Tromso on the archives of the early Norwegian missionaries), as well as at the British Council Library in Cameroon.

Looking to the future

Now completed, the archive provides raw material for a wide range of different research projects. An example of what is possible may be found in the work of Katie McKeown, who made a brief visit to Mbouda when studying for her master’s degree in 2007.18 Her research led to a small exhibition of Toussele’s work at the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford in 2007-2008. As this book goes to press in 2015, a documentary film made by Regis Talla about Toussele and his peers is in production, and a research student (funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council in collaboration with the British Library) has started field research in Cameroon.

I hope Toussele’s collection will inspire other archiving work and enable many different new research projects. Moreover, as was indicated at the beginning of this essay, I hope that such archives allow the history of African photography to be written on the basis of a large and representative sample rather than a few exemplary cases.19

References

Bouttiaux, Anne-Marie, Alain D’Hoogue and Jean Loup Pivin, eds., L’Afrique par elle-même: un siècle de photographie africaine (Paris: Revue Noire, 2003).

Edwards, Elizabeth, Raw Histories: Photographs, Anthropology and Museums (Oxford: Berg, 2001).

Jahn, Janheinz, Durch afrikanische Türen: Erlebnisse und Begegnungen in Westafrika (Frankfurt: Fischer Bücherei, 1967 [1960]).

Magnin, André, ed., Seydou Keïta (Zurich: Scalo, 1997).

McKeown, Katie, “Studio Photo Jacques: A Professional Legacy in Western Cameroon”, History of Photography, 34 (2010), 181-92.

Mercer, Kobena, Self-Evident (Birmingham: Ikon Gallery, 1995).

Newbury, Darren and Christopher Morton, eds., The African Photographic Archive (London: Bloomsbury, forthcoming in 2015).

Peffer, John, and Elisabeth L. Cameron, eds., Portraiture and Photography in Africa: African Expressive Cultures (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2013).

Pinney, Christopher, Camera Indica: The Social Life of Indian Photographs (Reaktion: London, 1997).

Poole, Deborah, Vision, Race and Modernity: A Visual Economy of the Andean Image World (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997).

Saint Léon, Pascal Martin, and N’Goné Fall, eds., Anthology of African and Indian Ocean Photography (Paris: Revue Noire, 1999).

Sprague, Stephen, “Yoruba Photography: How the Yoruba See Themselves”, African Arts, 12 (1978), 52-59.

Turin, Mark, “Born Archival: The Ebb and Flow of Digital Documents from the Field”, History and Anthropology, 22 (2011), 445-60.

Vokes, Richard, ed., Photography in Africa: Ethnographic Perspectives (Woodbridge: James Currey, 2012).

Werner, Jean-François, “La photographie de famille en Afrique de l’ouest: une méthode d’approche ethnographique”, Xoana, 1 (1993), 35-49.

—, “Produire des images en Afrique: l’exemple des photographes de studio”, Cahiers d’Etudes Africaines, 36/141-42 (1996), 81-112.

—, “Twilight of the Studios in Ivory Coast”, in Anthology of African and Indian Ocean Photography, ed. by Pascal Martin Saint Léon and N’Goné Fall (Paris: Revue Noire, 1999).

Zeitlyn, David, “A Dying Art?: Archiving Photographs in Cameroon”, Anthropology Today, 25/4 (2009), 23-26.

—, “Photographic Props/The Photographer as Prop: The Many Faces of Jacques Toussele”, History and Anthropology, 21 (2010), 453-77.

—, “Redeeming Some Cameroonian Photographs: Reflections on Photographs and Representations”, in The African Photographic Archive, ed. by Darren Newbury and Christopher Morton (London: Bloomsbury, forthcoming in 2015).

1 See Joseph Chila and Samuel Finlak: Two Portrait Photographers in Cameroon, ed. by Ingrid Swenson (London: Peer, 2005).

2 No glass plate negatives — as used in the 1960s in the camera shown (Fig. 16.1) — have survived, although a very small number of plastic plates were found and have been scanned. The archive covers the period from approximately 1970 to 1990.

3 EAP054: Archiving a Cameroonian photographic studio, http://eap.bl.uk/database/overview_project.a4d?projID=EAP054.

4 See the Digital Himalaya website at http://www.digitalhimalaya.com. See also Mark Turin, “Born Archival: The Ebb and Flow of Digital Documents from the Field”, History and Anthropology, 22 (2011), 445-60.

5 See Seydou Keïta, ed. by André Magnin (Zurich: Scalo, 1997). For parallels from Togo and Ivory Coast, see Jean-François Werner, “La photographie de famille en Afrique de l’ouest: une méthode d’approche ethnographique”, Xoana, 1 (1993), 35-49; and idem, “Twilight of the Studios in Ivory Coast”, in Anthology of African and Indian Ocean Photography, ed. by Pascal Martin Saint Léon and N’Goné Fall (Paris: Revue Noire, 1999), pp. 92-103.

6 For example, Stephen Sprague, “Yoruba Photography: How the Yoruba See Themselves”, African Arts, 12 (1978), 52-59.

7 For more on the Paris exhibition, see Anne-Marie Bouttiaux, Alain D’Hoogue and Jean Loup Pivin, L’Afrique par elle-même: un siècle de photographie africaine (Paris: Revue Noire, 2003). For the UK exhibition, see Kobena Mercer, Self-Evident (Birmingham: Ikon Gallery, 1995). An overview is presented in Anthology of African and Indian Ocean Photography, ed. by Saint Léon and Fall.

8 See Christopher Pinney, Camera Indica: The Social Life of Indian Photographs, Envisioning Asia (London: Reaktion, 1997); Deborah Poole, Vision, Race and Modernity: A Visual Economy of the Andean Image World (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997); and Elizabeth Edwards, Raw Histories: Photographs, Anthropology and Museums (Oxford: Berg, 2001).

9 See work in collections such as The African Photographic Archive, ed. by Darren Newbury and Christopher Morton (London: Bloomsbury, forthcoming in 2015); Photography in Africa: Ethnographic Perspectives, ed. by Richard Vokes (Woodbridge: James Currey, 2012); and Portraiture and Photography in Africa: African Expressive Cultures, ed. by John Peffer and Elisabeth L. Cameron (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2013).

10 I surveyed the work of Samuel Finlak and Joseph Chila, as well as a smaller sample of negatives from Photo Royale, Banyo.

11 For further discussion, see David Zeitlyn, “Redeeming Some Cameroonian Photographs: Reflections on Photographs and Representations”, in The African Photographic Archive, ed. by Newbury and Morton.

12 The main interviews were with Toussele, Chila and Finlak, but I also spoke with several other photographers in Adamaoua, Central, Northwest and West Regions of Cameroon.

13 My other papers include David Zeitlyn, “A Dying Art?: Archiving Photographs in Cameroon”, Anthropology Today, 25/4 (2009), 23-26; and idem, “Photographic Props/The Photographer as Prop: The Many Faces of Jacques Toussele”, History and Anthropology, 21 (2010), 453-77.

14 For an early description of how albums were used to introduce families to strangers, see Janheinz Jahn, Durch Afrikanische Türen: Erlebnisse Und Begegnungen in Westafrika (Frankfurt: Fischer Bücherei, 1967 [1960]), pp. 169-72.

15 See the film Funeral Season (La saison des funérailles): Marking Death in Cameroon, dir. by Matthew Lancit (2010).

16 It is very likely that, had I not been in touch with Toussele, the collection of negatives would have been burnt or discarded when he left his studio. I have met many photographers from his generation who have not retained their black-and-white negatives. Many reasons are given, the most common being that “since no one is interested any more, there is no money in it”.

17 The archive is available at http://eap.bl.uk/database/overview_project.a4d?projID=EAP054

18 Katie McKeown, “Studio Photo Jacques: A Professional Legacy in Western Cameroon”, History of Photography, 34 (2010), 181-92.

19 The project could not have taken place without the generous support of the British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme. In Cameroon, the Yaoundé office of the British Council have provided invaluable logistical support to the NGO “AAREF”, which has dealt with the everyday running of the project. The Cameroon National Archives have also encouraged the project from its inception. At the University of Kent (where I was based while the archiving took place), staff in the university’s photographic unit were extremely helpful in helping me move from theory to practice. An earlier version of this article appeared as David Zeitlyn, “Archiving a Cameroonian Photographic Studio with the Help of the British Library ‘Endangered Archives Programme’”, African Research and Documentation, 165 (2009), 13-26.