17. Music for a revolution: the sound archives of Radio Télévision Guinée

© Graeme Counsel, CC BY http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0052.17

I first travelled to West Africa in 1990. With little money and even less experience I crossed the Sahara via Morocco and spent a few weeks in Mauritania before returning home. This brief voyage had given me just a glimpse of the region, but it was sufficient to drive my determination to return. I was compelled to go to West Africa because of my interest in the origins of the Blues, and my research led me on a journey to trace its roots via the trans-Atlantic slave trade from Africa to the New World.1 Through my research I had discovered the music of West Africa’s Mandé griots, and this inspired my broader enquiries into the music of the region.

The Mandé are one of the largest ethnic groups in West Africa. Descendants from the formation of the Empire of Mali in the thirteenth century AD, today they number approximately twenty million people with significant populations in the nations of Mali, Senegal, Guinea Bissau and The Gambia. In Guinea they are known as Maninka. A griot 2 is a member of one of the Mandé’s endogamous social groups, the nyamakala, which includes blacksmiths, weavers and potters. Griots fulfil a multiplicity of roles in Mandé communities, including that of genealogists, arbiters, and masters of ceremonies at life events (births, circumcisions, weddings and funerals). They have been described as “singer-historians”,3 and they maintain an extensive repertoire of oral histories which are passed from one generation to the next. These histories are often performed as songs.4

During a trip through Ghana, Burkina Faso, Mali, Senegal, The Gambia, Guinea Bissau, Guinea and Côte d’Ivoire in 1994, I purchased a wide variety of local recorded music. The age of vinyl recordings had long since passed in West Africa, with newer mediums such as the audio cassette being the format of choice throughout the region at this time. In Guinea, however, I came across many local vinyl releases produced by a company called Syliphone, the national recording label of Guinea. I started to collect Syliphone’s vinyl discs from markets, locals, and wherever I could find them. The catalogue numbers of the discs indicated that more than 100 recordings had been released.

The Syliphone 33.3 rpm and 45 rpm discs that I was collecting had many features that set them apart from other African recordings of the era. A lot of care had gone into their production: the cover art was high quality glossy colour; the lyrics of the songs were often provided; the musicians were named; and lengthy annotations providing a musicological analysis were featured on many of the back covers. Another remarkable feature was the excellent quality of the audio. The sound engineer’s positioning of the microphones, the subtle use of echo effects, and the fidelity of the production were of the most exceptional standard when compared with recordings of a similar type. Such high quality audio had captured Guinea’s musicians at their best, and they clearly rivalled, if not surpassed, the great singers and groups from neighbouring Mali and Senegal.

Upon returning to Australia, I discovered that not only was scholarly research concerning the music of Guinea almost non-existent, but that of the few published discographies of West African music none could produce a complete list of Syliphone recordings.5 It became apparent that the only way to discover more about Syliphone was to obtain more of its catalogue. As my Syliphone collection began to grow, so did my efforts to re-create the complete discography. I returned to West Africa on subsequent occasions to continue my research, and each time I sought Syliphone recordings. I began to publish my discographies6 and research,7 and had made contact with African music collectors and experts, including John Collins, Günter Gretz, Stefan Werdekker and Flemming Harrev. Of all of Africa’s major recording labels we held Syliphone in very high regard.

During my doctoral fieldwork in Guinea in 2001, I met with personnel from the sound archives of the national broadcaster, Radio Télévision Guinée (RTG). Enquiries concerning Syliphone revealed that a significant section of the RTG’s audio collection had been destroyed during an attempted coup in 1985. The building had been bombed by artillery and the collection of Syliphone discs was lost. I was shown some audio recordings on reel-to-reel magnetic tape that consisted of unreleased recordings by Guinean orchestras of the Syliphone era. I surmised that these were the master tapes for potential Syliphone releases. A handwritten list of some fifty of these audio reels was produced, which I understood to be the archive’s complete holdings. The idea of a project to preserve these reels came to mind: a project that would not only re-create the complete recording catalogue of Syliphone but preserve its extant master tapes. I had been informed of the Endangered Archives Programme (EAP) through a colleague, so I began to formulate a project proposal.

The project context

On 28 September 1958, Guineans voted in a referendum to choose between total independence from France or autonomy within a confederation of French administered states. Guineans voted overwhelmingly for independence, and on 2 October 1958 they became the first of France’s colonies in Africa to become independent.8 Guinea’s bold demand for freedom defined the nation in the post-colonial era, though it came at a high cost. In a systematic and calculated process, France withdrew all assistance and support, and introduced a range of punitive economic measures that both impoverished and isolated the new nation.9 In a spiteful exercise, medical equipment, blueprints for the electrical and sewerage systems, electrical wiring, office fittings, uniforms for the police, rubber stamps, and cutlery, amidst a host of other items, were also removed or destroyed.10 Guinea had been made an example of, and though greatly disadvantaged from its inception, the nation nevertheless entered into independence full of optimism and hope, energised by its youthful and charismatic leader, President Sékou Touré.

One of the immediate challenges for the new leader of Guinea’s First Republic was the promotion of national unity.11 Touré was a strong proponent of the ideology of pan-Africanism, which sought the political union of all Africans. He believed that regionalism and tribalism had been exploited by the French in order to divide Guineans, and saw the task of developing indigenous cultures as fundamental to the challenge of ridding his people of the vestiges of the colonial mentality.12 Touré sought the “intellectual decolonization”13 of his nation, with the idea that Guinean culture must be revitalised, restored and re-asserted:

Marx and Ghandi have not contributed less to the progress of humanity than Victor Hugo or Pasteur. But while we were learning to appreciate such a culture and to know the names of its most eminent interpreters, we were gradually losing the traditional notions of our own culture and the memory of those who had thrown lustre upon it. How many of our young schoolchildren who can quote Bossuet are ignorant of the life of El Hadj Omar? How many African intellectuals have unconsciously deprived themselves of the wealth of our culture so as to assimilate the philosophic concepts of a Descartes or a Bergson? How many young men and young girls have lost the taste for our traditional dances and the cultural value of our popular songs; they have all become enthusiasts for the tango or the waltz or for some singer of charm or realism.14

In the prelude to independence Touré’s political party, the Parti Démocratique du Guinée (PDG), utilised music as a means of disseminating its policies. Women were instrumental in this role, and from the local markets to the train stations, from the public water taps to the taxi stands, songs were the primary means of communication to the PDG’s non-literate constituencies.15 Upon independence, music became the focus of the government’s efforts to develop an indigenous culture, and a few weeks after assuming power, the PDG created its first orchestra, the Syli Orchestre National.16 The orchestra was composed of the nation’s best musicians, hand-picked by the government.17 Touré decried Guinean musicians who played only foreign music, stating “that if one could not play the music of one’s country, then one should stop playing”.18 He issued a decree which banned all private orchestras from performing, and foreign music, in particular French music, was also removed from the government’s radio broadcasts.19 All spheres of local musical production were targeted, with the orchestra of the Republican Guard instructed to drop their colonial-era military marches and adopt the “warlike melodies, epic songs and anthems of ancient kingdoms and empires in Africa”.20

In the capital, Conakry, the government supported the members of the Syli Orchestre National to form their own groups, such as Orchestre de la Bonne Auberge, Camara et ses Tambourinis, and Orchestre du Jardin de Guinée.21 The government encouraged these new orchestras to compose songs that befitted the era of independence, as demonstrated by a series of ten LPs released from 1961 to 1963 by the American label Tempo International. These discs represent the first commercial recordings of Guinean music of the independence era, and were titled “Sons nouveau d’une nation nouvelle [New Sounds from a New Nation]”. Guinea’s musicians were encouraged to incorporate rhythms and melodies from the traditional musical repertoires into their new compositions, and thus transpose traditional Guinean music to a dance-orchestra setting.22

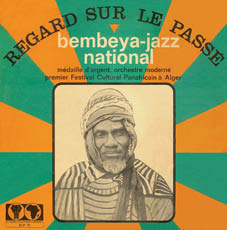

The Guinean government’s proactive approaches to creating orchestras and directing music broadcasting are early examples of policies of cultural nationalism. These became formalised when the government adopted authenticité as its official cultural policy. Authenticité was a philosophy that promoted a return to the values, ethics and customs found in “authentic” African traditions. Where its predecessor, négritude, sought “a symbiosis with other cultures”,23 the proponents of authenticité rejected such overtures as pandering to the West. Authenticité was entirely Afrocentric, and it called for “a self-awareness of ancestral values”.24 In Guinea this was achieved under the catchcry of “regard sur le passé [look at the past]”, a phrase that gained wide currency in the region following the release of a Syliphone LP recording of the same title.25 Under authenticité, Guinea’s musicians were encouraged to research the musical folklore of their regions and incorporate aspects such as the melodies, lyrics and themes into their new compositions. In effect, they were being asked to “look at the past” for their artistic inspiration, and thus re-connect Guinean society to its cultural and political history. Through this practice, the Guinean nation could advance because, as Touré declared, “each time we adopt a solution authentically African in its nature and its design, we will solve our problems easily”.26

Having banned all orchestras, the PDG set about creating new groups. The Guinean state is divided into more than thirty regions, and in each regional capital city the government created and sponsored an orchestra.27 Select musicians from the Syli Orchestre National were given the task of training the musicians of the new orchestras in the basics of composition and performance.28 The entire programme was state-sponsored, with musical instruments and equipment provided free of charge to all musicians in the orchestras. Those who were members of the national orchestras were placed on the government payroll, with such investment in culture coming at a great financial cost. Musical instruments and equipment, such as saxophones, amplifiers, electric guitars, drum kits, microphones, etc., could not be obtained locally, so the government flew a senior musician to Italy. There he purchased the equipment for all of the orchestras in Guinea, which by the mid-1960s had grown to over forty.29 In addition to the creation of orchestras, in each regional capital the government also created theatrical troupes, traditional music ensembles, and dance groups, who together formed artistic companies who represented their region.30 To encourage their endeavours and to showcase their talent, the government built or redeveloped performance venues in each regional capital.

The creation of troupes and venues was supported by the establishment of annual arts festivals. The first of these were held in 1960 and were known as the Compétition Artistique Nationale. The format of the festivals saw troupes from Guinea’s regions compete against each other in performance categories, such as ballet or theatre. The competition rounds took place over several months and culminated in a series of finals which were held in Conakry. In 1962, orchestras performed at the festivals for the first time, and the following year the competition expanded into a two-week event, thus becoming the Quinzaine Artistique et Culturelle Nationale. Prizes were awarded in the categories of orchestra, ballet, choir, theatre, ensemble instrumental, and folklore.31 When Guinea organised its Premier Festival National des Arts, de la Culture, et du Sport, over 8,000 committees at the district level sent delegates to compete, resulting in more than 10,000 competitors taking part in the festival. Guinea thus proclaimed its place as “the uncontested metropolis for the rehabilitation and development of the African cultural personality in all of its authenticity and its eminent human riches”.32

On 2 August 1968 the Guinean government announced a “Cultural Revolution”. This “third and final phase” of the transformation of the Guinean state33 called for renewed efforts towards modernisation,34 and it saw the transformation of Guinea’s education system through the establishment of Centres d’Education Révolutionnaire throughout the country. Coupled with the 2,500 Pouvoir Révolutionnaire Locales (local committee groups that formed the basis of the PDG’s pyramidal structure), the government had extended its influence into almost all aspects of daily life.

The Cultural Revolution further centralised cultural production in Guinea. All media was monopolised by the government, including the daily newspaper, Horoya, the radio broadcasts via Radio Guinea, and, from 1977, television via the RTG. The Guinean government had also formed its own film company, Syli-Cinema; its own photography unit, Syli-Photo; and Syliart, a regulatory body overseeing the production of literary works.35 The prevalence of the word “syli” is due to its derivation from the local Susu word for “elephant”, for the elephant was the party symbol and emblem of the PDG. Guinea’s currency was re-named the syli, and so pervasive was the use of the term “syli” that Guineans lit their fires with Syli brand matches.This merging of the Guinean nation with the syli illustrates the totalitarian nature of Touré’s regime, an autocracy that was further embedded by the Cultural Revolution.

As with its other industries, Guinea’s recording industry was operated entirely by the state. In 1968 this was formalised when the government announced the creation of Syliphone, its national recording company responsible for the reproduction and distribution of Guinean music.36

Fig. 17.1 The logo of the Syliphone recording company. © Editions Syliphone, Conakry, under license from Syllart Records/Sterns Music, CC BY.

By the late 1960s, Guinea’s cultural policy had successfully created a network of orchestras and musical groups throughout the nation. Some of the groups, such as Les Ballets Africains, were gaining international recognition. Having performed in various guises since 1947, Les Ballets Africains were nationalised following independence, and under the PDG they evolved to become the foremost dance troupe in the country, touring the world to broad acclaim.37 Other Guinean artists also gained international popularity, such as Kouyaté Sory Kandia, who was promoted as the “voice of Africa”, and Demba Camara, lead singer of Bembeya Jazz National.

Another star was Miriam Makeba, who was among the most successful African singers of the 1960s. Exiled from South Africa, Touré had invited her to Guinea in 1967 to attend a cultural festival. Of Guinea’s authenticité cultural policy, she “liked the fact that the people were going back to the roots of their music and their culture”.38 Touré gave Makeba and her husband Stokely Carmichael a residence, and Makeba lived in Guinea from 1969 until 1986. Touré appointed her one of Guinea’s best modern groups, the Quintette Guinéenne, with whom she performed Guinean songs.39

Guinea’s orchestras, too, were also very popular on the international stage, and many were sent on tours to Eastern Bloc nations, Europe, and the United States. Their impact was greatest, however, on the African continent, where they toured extensively and played for dignitaries (as the official group representing the president) and citizens alike. Their influence was furthered by Syliphone, who presented their recordings on 33.3 rpm and 45 rpm vinyl discs.

In the 1960s West Africa’s recording industry was in its infancy. Many nations lacked professional studio facilities and Guinea’s fledgling broadcasting infrastructure had been sabotaged by the departing French.40 Touré directed funds towards the improvement of Guinea’s radio network, and by the mid-1960s Guinea had one of the largest radio transmitters in West Africa. With the assistance of the West German government, a new building was constructed which housed four recording studios and was the centre for radio (and later television) production and broadcasting. It was named the Voix de la révolution and it was here that Syliphone recordings were made.41

Guinea’s cultural policy of authenticité was thus being broadcast via radio, concert tours, and commercial recordings. It had a considerable influence in the region, with Mali and Burkina Faso adopting similar approaches to national cultural production.42 By the late 1960s it had spread further, with Zaire43 and then Chad also adopting authenticité as their national cultural policy. By the mid 1970s, authenticité had blossomed into a movement, and Syliphone was one of the primary mediums through which it was promoted.

From circa 1967 to 1983 Syliphone released a catalogue of 160 vinyl discs that were distinctive in content, format and style. The lyrical content of the music was often overtly political and militant in theme, and featured songs that critiqued colonialism and neo-colonialism,44 extolled the virtues of socialism by exhorting citizens to unite and work for their country,45 or borrowed from themes and legends found in traditional African musical repertoires.46 Musically, the styles represented on the recordings were eclectic, with the musicians adapting elements from Cuban music,47 jazz,48 and African popular music49 to create new musical forms.50 The label was progressive in presenting modern music that successfully incorporated traditional instruments, songs and melodies into an orchestra setting. In the 1960s and 1970s, Guinea’s musicians were at the vanguard of contemporary African music — they were “the lighthouse to music in Africa”51 — and Syliphone captured them at the peak of their abilities and recorded their music in state of the art studios. The influence of the recording label on the development of African popular music was profound, and felt throughout the region.

Fig. 17.2 Bembeya Jazz National, Regard sur le passé (Syliphone, SLP 10, c. 1969). The photo depicts Samory Touré, grandfather of President Sékou Touré, who led the insurgency against French rule in the late nineteenth century. The orchestra’s version of the epic narrative in honour of his life earned them great acclaim; when it was performed at the First Pan-African Cultural Festival, held in Algiers in 1969, it won Guinea a silver medal. © Editions Syliphone, Conakry, under license from Syllart Records/Sterns Music, CC BY.

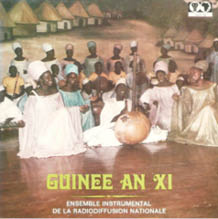

Fig. 17.3 Ensemble Instrumental de la Radiodiffusion Nationale, Guinée an XI (Syliphone, SLP 16, 1970). Guinea’s premier traditional ensemble displays the prominence of the griot musical tradition, with two koras (first and second rows, centre) and a balafon (second row, far left). © Editions Syliphone, Conakry, under license from Syllart Records/Sterns Music, CC BY.

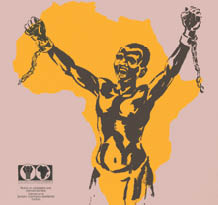

Fig. 17.4 The verso cover of a box set of four Syliphone LPs (Syliphone, SLP 10-SLP 13, 1970), released in recognition of the performances of Guinea’s artists at the First Pan-African Cultural Festival, held in Algiers in 1969. © Editions Syliphone, Conakry, under license from Syllart Records/Sterns Music, CC BY.

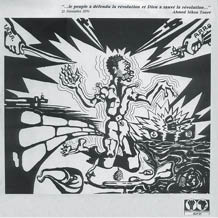

Fig. 17.5 Bembeya Jazz National/Horoya Band National, Concerts des Orchestres Nationaux (Syliphone, SLP 27, 1971). Political doctrine was reinforced through Syliphone. Here the cover depicts an enemy combatant, his boat blasted, surrendering to the JRDA (Jeunesse de la Révolution Démocratique Africaine, the youth wing of the PDG) and the APRG (Armée Populaire Révolutionnaire de Guinée). © Editions Syliphone, Conakry, under license from Syllart Records/Sterns Music, CC BY.

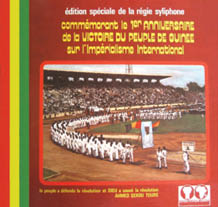

Fig. 17.6 Édition spécial de la régie Syliphone. Commémorant le 1eranniversaire de la victoire du peuple de Guinée sur l’Impérialisme International (Syliphone SLPs 26-29, 1971). A box set of four LP discs (“Coffret special agression”) released to celebrate Guinea’s victory over the Portuguese-led forces which invaded the country in 1970. © Editions Syliphone, Conakry, under license from Syllart Records/Sterns Music, CC BY.

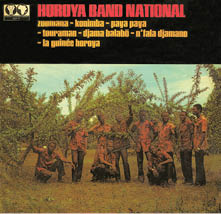

Fig. 17.7 Horoya Band National (Syliphone, SLP 41, c. 1973). Many of Guinea’s orchestras featured the band members wearing traditional cloth. Here, an orchestra from Kankan in the north of Guinea wears outfits in the bògòlanfini style associated with Mandé culture. © Editions Syliphone, Conakry, under license from Syllart Records/Sterns Music, CC BY.

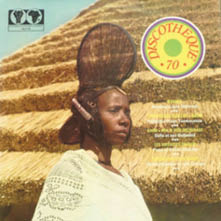

Fig. 17.8 Various Artists, Discothèque 70 (Syliphone, SLP 23, 1971). Tradition and modernity: a compilation of music by Guinean orchestras is promoted by images from local cultural traditions. Here, a Fulbé woman is depicted. © Editions Syliphone, Conakry, under license from Syllart Records/Sterns Music, CC BY.

From around 1967, Syliphone began to release the first of its 750 songs recorded on 12-inch (33.3 rpm) and 7-inch (45 rpm) vinyl discs. 52 Many of the recordings would become classics of African music. Of note is the 1969 recording by Bembeya Jazz National, “Regard sur le passé”,53 which presents the life of Almami Samory Touré, a national hero who fought against French rule in the nineteenth century. The orchestra’s version of his life story, performed in a style closely associated with that of the traditional griots, extended to over 35 minutes and used both sides of the LP — a first for a modern African recording. The group’s performance of the song (as the Syli Orchestre National) at the Premier Festival Cultural Panafricain held in Algiers in 1969 earned them a silver medal. In 1970 the Académie Charles Cros awarded its Grand Prix du Disque to a Syliphone LP by Kouyaté Sory Kandia,54 a recording which featured the mezzo-soprano performing traditional griot songs on side A of the disc and accompanied by the modern orchestra Keletigui et ses Tambourinis on side B.

Few other African nations could demonstrate a commitment to musical culture to the extent of the Guinean government’s. Its national cultural policy of authenticité and of “looking at the past” had created dozens of state-sponsored orchestras who released hundreds of songs that were at the cutting edge of African music. Guinea’s musicians and arts troupes toured Africa and the world, and were a feature of the nation’s cultural festivals where they were joined by thousands of other performers. Syliphone was at the centre of this cultural movement. It was emblematic of Africa’s independence era, and captured a moment in African history when a new nation asserted its voice and placed music at the forefront of its cultural identity.55

As the voice of the revolution, Syliphone recordings also served as a bulwark for Touré’s leadership. There were many hundreds, perhaps thousands, of songs that were recorded which praised the president, thus illustrating the personality cult that was being created around the Le Responsible Suprême et Stratège de la Révolution, as Touré had become known. “Kesso”, by Keletigui et ses Tambourinis, is one example.56 The chef d’orchestre of the group and its lead guitarist, Linké Condé, explained the meaning of the song:

The title can be translated as “home” and it is dedicated to Sékou Touré. It says that a person will never be defeated by the words of an enemy. It compares the Guinean nation to a woman who needs to be married, so in effect the people of Guinea are married to the President. Many different praises are used in the song. It names many towns that are ready to receive the President and welcome him.57

This kind of positive imagery extended beyond praise of the president to portrayals of a utopian lifestyle. “Soumbouyaya” is a case in point, whereby a rotund and popular mythological character is associated with the bounteous wealth that is found in Guinea under the PDG: “Since the world has been created, I have not seen a country like Guinea […] My people, the country will flourish thanks to commerce”.58 The annotations to a Syliphone recording describe it as “a nourishing disc”, with its songs, such as “Labhanté”, proclaiming “Artisans, peasants, students, workers! Only work liberates! Transform the world through our work!”,59 while “M’badenu” on the same disc informs the listener that “nothing is more beautiful” than to be working for your country.60

The reality of life in Guinea during the First Republic of Touré (1958-1984) was, however, far removed from that depicted on the Syliphone recordings. A weakening economy had fed discontent with the PDG and its leadership as early as 1960, when the so-called “Ibrahima Diallo” plot was uncovered.61 It was the first in a long series of purported “fifth columnist” plots and subversions which were used by Touré to quell dissent and centralise power. Opposition to the president’s authority was not tolerated, with opponents of the government risking arrest, imprisonment, torture, or a death sentence in the notorious Camp Boiro prison. Others simply disappeared. These efforts to eliminate opponents of the regime were aided by informants and loyalists who comprised some 26,000 party cells that were located in Guinea’s villages, towns and cities.62 Although Touré had entered the presidency with a popular mandate, Guineans were now unable to dislodge their leader.

On 22 November 1970, a Portuguese-led invasion force attacked Conakry. Although it was repelled by government and local forces, it provided the president with the concrete evidence needed to support his claims of destabilisation. The attempted invasion was followed by a wave of arrests, and the show trials and public hangings which followed did not spare members of Touré’s inner circle. As the decade progressed, Guinea’s economy contracted further. New laws were introduced which banned all private trade and made the smuggling of goods punishable by death. In 1976 a new plot was announced by the PDG, the “Fulbé plot”, whereby members of Guinea’s largest ethnic group were accused of being the enemies of socialism.63 With a history of opposition to the PDG, Fulbé candidates had stood against Touré in the prelude to independence. The president now threatened their entire ethnic group with annihilation: “We have respected them, but as they do not like respect, we present them with what they like: brute force! […] We will destroy them immediately, not by a racial war, but by a radical revolutionary war”.64

By the end of the decade, approximately 25% of Guinea’s population had fled to escape persecution and the rigours of life under the PDG. Such matters, however, were never referred to on Syliphone recordings. There are no songs of dissent or any that offer even the mildest of criticisms, with all broadcast material vetted by censors prior to release to ensure conformity. There were no private groups in Guinea to voice protest, no private studios to record them, and no private media to transmit their material.

This lack of political dissent in Guinean music has recently been addressed by Nomi Dave, who notes the dominance of griot performance practices and their influence on Guinean music.65 One of the key aspects of jeliya, as the griots’ artistry is known, is the practice whereby griots sing praise songs to their patrons. For musicians of the First Republic, their patron was the state, hence their repertoires contained numerous examples of songs which praised government figures, industries, campaigns and policies.66 This alignment to political doctrine had been embedded by the nationalist political campaigns of the 1950s, whereby musicians had been mobilised to disseminate party ideologies.67 Such appropriations stifled creativity and silenced the voices of protest, particularly in Guinea where performers operated within the narrowest of political confines.

A further factor that contributed to the “silence” of protest was cultural: direct criticism in West African society is considered ill-mannered to the extent of it being a social faux pas. It is also highly unusual for griots to directly criticise their patrons; any criticism is offered obliquely via analogy and metaphor. Bembeya Jazz National’s “Doni doni”,68 for example, with its lyrics “Little by little a bird builds its nest, little by little a bird takes off”, caused some consternation at the highest levels as to its allusive potential vis à vis the large numbers of citizens fleeing Guinea.69 The nation’s censors, however, were in less doubt about the double entendre contained in Fodé Conté’s song “Bamba toumani”,70 which described a caterpillar, and how its head eats everything: the song was never released by Syliphone, and Conté fled Guinea shortly after recording it. Such musical examples are extremely rare, and few musicians dared to express anything but solidarity with the Guinean regime. The socio-political situation of the era required the artists’ creativity and conscience to be silenced, less they risk their lives.71

Guinea’s Cultural Revolution came to a close on 26 March 1984 when Touré died suddenly of a heart attack. A week later a military coup ousted his regime and set about dismantling the cultural policies of the First Republic. It was the end of Syliphone, the end of funding for the orchestras and performance troupes, the end of the cultural festivals, and the end of authenticité. Colonel Lansané Conté was Guinea’s new president, and he would rule for a further 24 years. Such were the demands of allegiance on musicians that, long after Touré’s death, many who served his government still choose to deflect rather than answer enquiries related to his rule.72 Although the era of the one-party state and of Cultural Revolution has passed, the “silence” persists. It is reinforced by severe and ongoing economic hardships which make it imprudent for musicians to criticise contemporary figures, for they are tomorrow’s potential benefactors. As Dave indicates, it is a silence which allows musicians to accommodate the political regimes and to manage their lives in highly volatile contexts.73

From 1984 until 2008, under President Conté, the vast majority of the music of the First Republic was never broadcast on Guinean radio. The RTG employed censors who vetted recordings prior to broadcasting. It was a practise initiated by Touré’s regime, and during Conté’s presidency it rendered large parts of the audio collection to gather dust in the archives. Songs which praised Touré, the PDG, its leadership, or its policies were taboo, thus effectively silencing the music of the revolution. Though attempts by the Conté government to rehabilitate the era and legacy of Touré commenced in 1998,74 such actions were uncoordinated, low-key and sporadic. Efforts to reconcile the Guinean nation with its past were far from a priority for Conté’s government, whose descent into nepotism, corruption and the drug trade has been well documented.75 Access to the National Archives was unreliable and limited; its director explained to one researcher: “We cannot allow the public to go leafing through these documents. Can you imagine the kinds of social disruption this would cause? For the sake of peace in Guinea, those documents must not be consulted”.76

As historical documents, the audio recordings of the RTG archives could have provided a meaningful contribution to the rehabilitation process, but for 25 years this did not occur. Rather, a silence was imposed whereby it was politically expedient to erase the recordings from the cultural memory. Little effort was directed towards the preservation of the audio materials, which lay dormant in far from suitable conditions. Perhaps the RTG’s audio archive was regarded by the authorities as a tinderbox, one that was so imbued with a kind of political nyama (a powerful force conjured by griots during their performances) that it must remain hidden from the public, lest the revolution takes hold and rises from the ashes. In a political landscape that had scarred so many, the RTG’s archives contained materials that would very likely reignite passions and debates. Its capacity for both harm and good resonates with attitudes to similar documents from Guinea’s First Republic, insofar as they are seen to have the potential to both cleanse and destabilise society.77 Whatever the government’s motivation, or lack of it, the inactivity of the Conté years (1984-2008) resulted in a generation of young Guineans being denied the music of their nation’s independence era. If successful, the EAP projects would bring to light that which had been hidden in the RTG’s archives for decades.

The 2008 EAP project

I arrived in Guinea in August 2008 to commence the project EAP187: Syliphone – an early African recording label.78 The project worked in partnership with the Bibliothèque Nationale de Guinée (BNG), and was given excellent support through its director, Dr Baba Cheick Sylla. During the Touré era, Guinea had its own press, the Imprimerie Nationale Patrice Lumumba, and the government had established one of the best-resourced libraries in West Africa. After Touré’s death, however, many of the official documents and archives were destroyed, damaged, or left scattered in various locations. Dr Sylla had spent many years gathering the materials and saving them from destruction.79 The RTG had not been spared either, and following its bombing in 1985 it was thought that the collection of Syliphone recordings was permanently lost.

The aim of the EAP project was two-fold: to re-create the complete Syliphone catalogue of vinyl discs and archive the recordings in digital format; and then to locate any surviving Syliphone-era studio recordings and archive and preserve them. The project involved the cooperation of two ministries, the Ministère de la Culture des Arts et Loisirs, who presided over the BNG, and the Ministère de la Communication, who administered the RTG.

Over a period of fourteen years, I had gathered many Syliphone vinyl recordings, but not all of the collection was in good condition. Vinyl recordings scratch very easily, and Guinea’s climatic extremes produced annual abundances of mould in the wet season and harmattan dust in the dry, which caused many recordings to be in a far from pristine condition. Musicians, technicians and government officials were contacted in order to assist in the search for the best quality discs for the project. A full colour catalogue was printed, which featured each Syliphone vinyl recording with its cover both recto and verso, and which was presented to Minister Iffono and his culture ministry.

Politically, Guinea had been enduring a prolonged period of instability. Decades of corruption, cronyism and mismanagement in the government had relegated the country to the lowest reaches of the United Nation’s Human Development Index. In 2007, nation-wide strikes and related protests had left dozens dead. President Conté, now in his seventies, was rumoured to be bed-ridden and close to death. On 2 October 2008, Guinea would achieve fifty years of independence, yet it was unclear how such a momentous occasion would be celebrated. Preparations were very low-key, though the Ministère de la Culture des Arts et Loisirs had organised for the EAP project to open for a week-long exposition at the National Museum. It remained to be seen how the project, with its large catalogue of performances by Guinea’s most acclaimed and revered musicians — who faithfully exalted Touré in their songs and who lavished praise on his ideals for the nation — would be integrated into the independence festivities.

The EAP project was due to open on 29 September 2008, and to generate interest amongst the public, the RTG broadcast a television commercial for the event.80 All of the Syliphone vinyl recordings had been collected, archived and catalogued by the opening date, and they were now digitised and displayed in the National Museum’s exhibition centre. A large media contingent attended the opening of the exhibition, and the event was well received. With the first part of the EAP project completed, my attention now turned to the RTG sound archives. Formal enquiries had failed to deliver access to the archives, however the success of the Syliphone exposition had helped to propel the requests, and on 6 October the Ministère de la Communication agreed that the second stage of the archival project could commence.

Based upon a hand-written catalogue that I was shown in 2001 when conducting my doctoral research, I estimated that the RTG held approximately fifty audio reels of Syliphone era recordings. However, when I gained entry to the sound archive I saw what appeared to be thousands of reels scattered amongst rows of shelving from floor to ceiling. Many of the reels were in poor physical condition, and their preservation and digitisation were urgent. I set to work, transferring the magnetic reels of tape to a digital medium. Recordings by Guinea’s national and regional orchestras were prioritised, and with many reels at over seventy minutes, the collection represented a very large volume of work.

The EAP project was now focused on preserving music from the Syliphone era that had not been commercially released but which had been broadcast on its original magnetic tape format on Guinea’s national radio network. As the archival project continued, the true extent of the authenticité policy was revealed. Audio recordings by groups and performers from every region of Guinea were uncovered.81 It was apparent that the archive held great significance, not only as a resource for musicological research but also for the social sciences more broadly. Given the extent of the audio archives, however, it became clear that it would be impossible to complete the project within its timeline. In December 2008, the project concluded. 69 reels of recordings had been archived, and these contained 554 songs by Guinean orchestras.

Fig. 17.9 The Radio Télévision Guinée (RTG) offices in Boulbinet, Conakry.

Photo by author, CC BY-NC-ND.

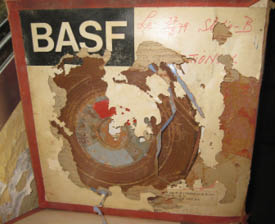

Fig. 17.10 Audio reels stored in the RTG’s “annexe”.

Photo by author, CC BY-NC-ND.

Fig. 17.11 Some of the audio reels were in urgent need of preservation.

Photo by author, CC BY-NC-ND.

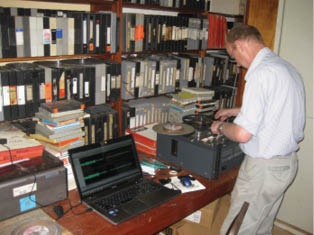

Fig. 17.12 Archiving the audio reels and creating digital copies.

Photo by author, CC BY-NC-ND.

Subsequent EAP projects

In order to complete the 2008 archival project, a further application for EAP funding was made, and I returned to Guinea in July 2009.82 President Conté had died on 22 December 2008, an event which heralded a military coup led by Captain Moussa “Dadis” Camara.83 The Ministère de la Culture des Arts et Loisirs was now combined with the Ministère de la Communication into a single ministry, which was led by Justin Morel, Jr. This bode extremely well for the project, as JMJ (as he is colloquially known) was a former journalist who was responsible for the annotations on many of the Syliphone discs.

I estimated that the RTG held approximately 1,000 reels that required digitising and preservation. The EAP project commenced in August, under the shadow of a disintegrating security situation. Public discontent with President Camara had led to street protests which were violently quelled by the military. The protests culminated on 28 September 2009 with an anti-government rally held at the national football stadium. Tens of thousands attended, only to be attacked by several units of fully armed soldiers and presidential guardsmen. Nearly 200 people were killed and more than 2,000 injured. Witnesses stated that Fulbé protestors at the rally were singled out and murdered by the military,84 and there were rumours of a split in the army and of civil war. The RTG did not report any of these events, but as news of the massacre spread, people prepared to flee Conakry. It became apparent that conducting research and working at the RTG in such an environment would be impossible. The building and office complex lies at the centre of government communications and it had previously been the focus of military actions. Many governments were advising their nationals to depart, and with this the EAP project was abandoned. Before this abrupt end, the project had successfully digitised and archived 229 reels of music containing 1,373 songs.

The United Nations announced an International Commission of Inquiry into the “stadium massacre”, as it had become known, with charges of crimes against humanity to be laid on those responsible. These events caused considerable internal friction within the Guinean military government, and on 3 December 2009 an assassination attempt was made on President Camara in the small army barracks which adjoins the RTG. Camara survived, and was flown to Morocco to recuperate. After several months of convalescence, Camara was ready to return to Guinea and reclaim the Presidency, however Guinea’s interim leader – Gen. Sékouba Konaté – forbade his return. Rather, Konaté led Guinea towards democracy, and in 2010 the nation held its first democratic elections. These brought Alpha Condé to the presidency, and with stability restored, the EAP projects could recommence. Further funding to complete the archival project was granted, and it resumed in August 2012.85

Due to the uncertainty and volatility of the political situation, the project focused on preserving and archiving the oldest materials available. These audio reels required intensive conservation, for the original magnetic tape of the recordings had become brittle with age. The audio fidelity of the music, however, was still remarkably good. The EAP project’s scope had also been expanded to include a small building adjacent to the RTG, known as the “annexe”. Accessing the annexe was problematic, however, for the RTG authorities had initially denied its existence. I had been inside this small archive previously and seen hundreds of audio reels, and once this was conveyed it was confirmed that the archive did in fact exist, but it contained no music, only speeches. It was only after persistent enquiries that I was permitted access to the annexe, which was perplexing. Consisting of one large room, with no climate control and water above one’s ankles when it rained, the annexe contained numerous shelves of audio reels of music stored in an ad hoc fashion. The purpose of the annexe, however, appeared to be to house many hundreds of reels of speeches by Sékou Touré, all stored in neat rows, the preservation of which was unfortunately outside the parameters of the project.

A further remarkable aspect of the annexe was its unusually high percentage of audio recordings by Fulbé artists. My research of Syliphone recordings had indicated a strong bias towards Maninka performers at the expense of Fulbé artists. It had been my contention that the idea to “look at the past” for cultural inspiration was in fact an invitation to look at Guinea’s Maninka past, primarily, and that figures and events associated with Maninka history were invariably the subject of songs and praise. Moreover, I claimed that Guinea’s representations of national culture as expressed through Syliphone invariably depicted a Mandé cultural aesthetic, which over time had come to dominate the (cultural) politics of the era and which was the façade of nationalism.86 Songs performed in Maninkakan accounted for over 70% of Syliphone recordings, while those sung in Fulfulde (the language of the Fulbé, Guinea’s largest ethnic group) accounted for just 3%. In the RTG’s annexe, however, approximately 20% of the recordings were performed in Fulfulde.

In January 2013 the archiving of the audio reels held at the RTG and its annexe was completed. The EAP project had preserved, digitised, archived and catalogued 827 audio reels containing 5,240 songs. Together, the three EAP projects archived a total of 1,125 reels which contained 9,410 songs, or some 53,000 minutes of material. The RTG’s collection frameworks the entire development of Guinean music following independence, from the birth of a new style in the early 1960s to the year 2000. 90% of the material dates to the era of the First Republic of Sékou Touré. The earliest recordings archived were two reels from 1960, both of which featured griots (Mory and Madina Kouyaté87 and Ismaila Diabaté88). The earliest recordings by an orchestra presented the Orchestre Honoré Coppe Orchestre Honoré Coppet from 2 February 1963,89 a recording which presaged the musical styles which would later define Guinean music. Pre-Syliphone recordings of the Syli Orchestre National,90 Balla et ses Balladins,91 Orchestre de la Paillote,92 the 1ère Formation de la Garde Républicaine,93 and Kébendo Jazz94 are also in evidence.

17.1 Orchestre Honoré Coppet, “no title” (1963), 4’40”. Syliphone2-068-02.

To listen to this piece online follow this link: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/media/978-1-78374-062-8/no-title

17.2 Syli Orchestre National, “Syli” (c. 1962), 4’33”. Syliphone3-248-3.

To listen to this piece online follow this link: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/media/978-1-78374-062-8/Syli

17.3 Balla et ses Balladins, “PDG” (c. 1970), 5’22”. Syliphone2-089-08.

To listen to this piece online follow this link: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/media/978-1-78374-062-8/PDG

These early orchestra recordings reveal the strong influence of Cuban and Caribbean music, with songs performed as mambos, meringues, pachangas, boleros, beguines, rumbas and boogaloos,95 many of which were sung in less-than-fluent Spanish. Of particular interest are two reels, recorded by the Orchestre de la Brigade Féminin on 8 November 196396 and 7 November 1964.97 This group was Africa’s first all-female orchestra,98 who would later gain worldwide fame as Les Amazones de Guinée. These, their first recordings, predated their commercial releases by twenty years.

17.4 Orchestre de la Paillote, “Dia” (1967), 3’48”. Syliphone4-358-10.

To listen to this piece online follow this link: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/media/978-1-78374-062-8/Dia

17.5 Orchestre de la Garde Républicaine 1ère formation,

“Sabougnouma” (1964), 4’25”. Syliphone2-067-02.

To listen to this piece online follow this link: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/media/978-1-78374-062-8/Sabougnouma

17.6 Kébendo Jazz, “Kankan diaraby” (1964), 3’20”. Syliphone2-052-03.

To listen to this piece online follow this link: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/media/978-1-78374-062-8/Kankan-diaraby

17.7 Orchestre Féminin Gendarmerie Nationale,

“La bibeta” (1963), 3’41”. Syliphone4-382-08.

To listen to this piece online follow this link: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/media/978-1-78374-062-8/La-bibeta

The greater part of the music archived by the EAP projects was recorded at the Voix de la Révolution studios at the RTG, although a significant number of live concert recordings were also archived. Of particular interest are recordings of concert performances by Guinean orchestras, few of which appeared on Syliphone discs due to the length of the performances exceeding the practicalities of the vinyl medium. Among the concerts are performances by the legendary Demba Camara, the lead singer of Bembeya Jazz National, who died in 1973.99 Live concerts by Myriam Makeba are also in evidence.100 All of Guinea’s 36 regional orchestras and eight national orchestras are represented in the archive, with many recorded between 1967 and 1968.101 Recordings of orchestras of the post-Touré era are also present, with numerous examples from groups such as Atlantic Mélodie, Super Flambeau and Koubia Jazz.

17.8 Syli Authentic, “Aguibou” (c. 1976), 7’04”. Syliphone2-077-01.

To listen to this piece online follow this link: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/media/978-1-78374-062-8/Aguibou

17.9 Koubia Jazz, “Commissaire minuit” (1987), 5’40”. Syliphone4-022-03.

To listen to this piece online follow this link: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/media/978-1-78374-062-8/Commissaire-minuit

17.10 Bembeya Jazz National, “Ballaké” (c. 1972), 8’02”. Syliphone2-091-01.

To listen to this piece online follow this link: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/media/978-1-78374-062-8/Ballake

Performances in the modern styles, however, are not restricted to the large-scale orchestras, with a wealth of material by smaller groups and popular artists present in the collection. Of note are unreleased recordings by Kouyaté Sory Kandia, recorded with a traditional ensemble.102 Mama Kanté, the powerful lead singer of l’Ensemble Instrumental de Kissidougou, is known internationally by just one track which appeared on Syliphone,103 yet the RTG archive contains dozens of her recordings. One of Guinea’s most popular singers was Fodé Conté, an artist who did not appear on a single Syliphone release. The RTG archive contains over 100 of his recordings, including his last sessions before fleeing Guinea.104

17.11 Kouyaté Sory Kandia, “Miniyamba” (c. 1968), 2’24”. Syliphone4-380-05.

To listen to this piece online follow this link: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/media/978-1-78374-062-8/Miniyamba

17.12 Kouyaté Sory Kandia, “Sakhodougou” (c. 1973), 8’26”. Syliphone3-168-4.

To listen to this piece online follow this link: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/media/978-1-78374-062-8/Sakhodougou

17.13 Mama Kanté avec l’Ensemble Instrumental de Kissidougou, “JRDA” (1970), 4’37”. Syliphone4-251-12.

To listen to this piece online follow this link: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/media/978-1-78374-062-8/JRDA

17.14 Fodé Conté, “Bamba toumani” (c. 1978), 3’33”. Syliphone4-165-01.

To listen to this piece online follow this link: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/media/978-1-78374-062-8/Bamba-toumani

The acoustic guitar tradition for which Guinea is well-known is also represented through a number of excellent recordings by Manfila Kanté (of Les Ambassadeurs) and Manfila “Dabadou” Kanté (of Keletigui et ses Tambourinis). Kemo Kouyaté also presents several instrumental recordings (some of which feature a zither accompaniment),105 while Les Virtuoses Diabaté provide further material which augments their Syliphone vinyl recordings.106 The audio collection also features several versions of popular Guinean songs, with multiple examples of “Diaraby”, “Malamini”, “Kaira”, “Soundiata”, “Wéré wéré”, “Kemé bouréma”, “56”, “Armée Guinéenne”, “Toubaka”, “Tara”, “Douga”, “Nina”, “Minuit”, “Mariama”, “Lannaya” and “Malisadio” performed by solo artists and orchestras alike, thus providing significant resource materials for comparative analyses.

17.15 Les Virtuoses Diabaté, “Toubaka” (c. 1971), 4’22”. Syliphone4-047-04.

To listen to this piece online follow this link: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/media/978-1-78374-062-8/Toubaka

17.16 Kadé Diawara, “Banankoro”(c. 1976), 4’25”. Syliphone4-446-10.

To listen to this piece online follow this link: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/media/978-1-78374-062-8/Banankoro

17.17 M’Bady Kouyaté, “Djandjon” (c. 1974), 7’35”. Syliphone4-322-03.

To listen to this piece online follow this link: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/media/978-1-78374-062-8/Djandjon

More than half of the recordings in the collection are examples of traditional Guinean music. Many of these feature artists performing within the Maninka griot tradition, such as Kadé Diawara and Tö Kouyaté, who were the lead singers of the Ensemble Instrumental National. Instrumentalists such as M’Bady Kouyaté, one of Guinea’s foremost kora players, are also well represented. The Maninka material is augmented, however, by hundreds of recordings from Guinea’s other ethnic groups, including music by Susu, Guerzé, Kissi, Toma, Sankaran, Baga, Diakhankhé, Kônô, Wamey, Landouma, Manon, Lokko, Lélé, Onëyan and Bassari performers. The archive contains many unique recordings by these, and other, ethnic groups.

17.18 Femmes du Comité Landreah, “Révolution” (1964), 2’54”. Syliphone3-068-3. Sung in the Susu language.

To listen to this piece online follow this link: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/media/978-1-78374-062-8/Revolution

17.19 Musique Folklorique du Comité de Guèlémata, “Noau bo kui kpe la Guinée ma” (1968), 2’33”. Syliphone3-088-3. Sung in the Guerzé language.

To listen to this piece online follow this link: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/media/978-1-78374-062-8/Noau-bo-kui

17.20 Sergent Ourékaba, “Alla wata kohana” (c. 1986), 2’10”. Syliphone4-755-06. Sung in the Fulfuldé language.

To listen to this piece online follow this link: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/media/978-1-78374-062-8/Alla-wata-kohana

It is also important to note the quantity of Fulbé music. Marginalised politically and under-represented culturally, the RTG archive contained over 1,000 songs sung in Fulfuldé by popular singers such as Binta Laaly Sow, Binta Laaly Saran, Ilou Diohèrè, Doura Barry, Amadou Barry and Sory Lariya Bah. Perhaps the most popular of all Fulbé artists was Farba Tela (real name Oumar Seck), who was an influence on Ali Farka Touré. No commercial recordings of his music were released, with the 45 songs recorded at the RTG representing his complete catalogue to date.

17.21 Binta Laaly Sow, “56” (c. 1986), 5’01”. Syliphone4-581-09.

To listen to this piece online follow this link: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/media/978-1-78374-062-8/56

17.22 Farba Téla, “Niina” (1979), 7’52”. Syliphone3-097-2.

To listen to this piece online follow this link: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/media/978-1-78374-062-8/Niina

This breadth of diverse recordings from Guinea’s ethnic groups spans forty years and underscores the significance of the RTG audio collection. At the conclusion of the EAP project the Ministère de la Culture, des Arts et du Patrimoine Historique organised a ceremony held at La Paillote, one of Guinea’s oldest music venues. All of the surviving chefs d’orchestre of the national orchestras attended, and Les Amazones de Guinée and Keletigui et ses Tambourinis, two of Guinea’s grands orchestres, performed.107 A large media presence documented the event.

Conclusion

The archiving of the audio collection held at Radio Télévision Guinée represents one of the largest sound archival projects conducted in Africa. For a generation, most of its 9,410 songs were considered too politically sensitive to be broadcast and were hidden from public view. Interest in the recordings, however, especially in the international market, had been growing, led by a renewed awareness of the importance of the Syliphone recording label in the development of African music, and of its symbolic role as the voice of the Guinean revolution. To date, over fifty CDs of Syliphone material have been released.108

It is germane that the RTG’s audio collection is now available for the Guinean public to access and for Guinean radio to broadcast, for it comes at a time when Guinea is implementing democratic reforms and multi-party government for the first time. The success of the EAP projects through the cooperation of several Guinean ministries signals a willingness by the government to engage with Guinea’s past, and to reconcile the political aspirations and motivations of its leaders with those policies and practices which had failed its citizens.

It is within this spirit of national reconciliation that the sound archive will greatly contribute to our understanding of Guinea’s journey. For Guineans it will demonstrate the tremendous value that their first government placed on rejuvenating and promoting indigenous culture. It will also indicate the extraordinary depth of talent of Guinea’s musicians, and it will remind us all of the concerted efforts of a young nation to develop culture, to restore pride and dignity to culture, and to promote African identity.

In recognition of his Endangered Archive Programme projects and his contribution to culture, the Guinean government bestowed on the author Guinea’s highest honour for academic achievement, the gold medal of the Palme Académique en Or, and a Diplôme d’Honneur.

References

Adamolekun, Ladipo, Sékou Touré’s Guinea: An Experiment in Nation Building (London: Methuen, 1976).

Anonymous, “Création en Guinée d’une régie d’édition et d’exploitation du disque ‘Syliphone’”, Horoya, 16 May 1968, p. 2.

—, “De la Révolution Culturelle”, Horoya, 30 August 1968, p. 2.

—, Annotations to Disque souvenir du Premier Festival National de la Culture. Conakry – du 9 au 27 mars 1970. Folklores de Guinée (Syliphone, SLP 18, 1970).

—, “Guinea: September 28 Massacre was Premeditated”, Human Rights Watch, 27 October 2009, http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2009/10/27/guinea-september-28-massacre-was-premeditated

Arieff, Alexis and Nicolas Cook, “Guinea: Background and Relations with the United States”, Congressional Research Service Report 7-5700/R40703 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2010).

Arieff, Alexis and Mike McGovern, “‘History is Stubborn’: Talk about Truth, Justice and National Reconciliation in the Republic of Guinea”, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 55/1 (2013), 198-225.

Arnaud, Gérald, “Bembeya se réveille”, Africultures, 1 November 2002, http://www.africultures.com/php/?nav=article&no=2626

Bah, Tierno Siradiou, “Camp Boiro Internet Memorial”, Camp Boiro Memorial, 2012, http://www.campboiro.org/cbim-documents/cbim_intro.html

Browne, Don R., “Radio Guinea: A Voice of Independent Africa”, Journal of Broadcasting, 7/2 (1963), 113-22.

Bureau Politique du Mouvement Populaire de la Révolution, Authenticité, l’Etat et le parti au Zaïre (Zaïre: Institut Makanda Kabobi, 1977).

Camara, Mohamed Saliou, His Master’s Voice: Mass Communication and Single Party Politics in Guinea under Sékou Touré (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2005).

—, Thomas O’Toole and Janice E. Baker, Historical Dictionary of Guinea, 5th edn (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2013).

Camara, Sékou, “Sékou Camara dit le Gros, membre-fondateur du Bembeya Jazz National de Guinée”, interview by Awany Sylla, Africa Online, 20 December 1998, http://www.africaonline.co.ci/AfricaOnline/infos/lejour/1167CUL1.HTM (accessed 28 June 2014 via Wayback Machine Archive).

Charry, Eric, Mande Music: Traditional and Modern Music of the Maninka and Mandinka of Western Africa (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2000).

Charters, Samuel, The Roots of the Blues: An African Search (London: Quartet, 1982).

Cohen, Joshua, “Stages in Transition: Les Ballets Africains and Independence, 1959 to 1960”, Journal of Black Studies, 43/1 (2012), 11-48.

Collins, John, West African Pop Roots (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1992).

Coolen, Michael T., “Senegambian Archetypes for the American Folk Banjo”, Western Folklore, 43 (1984), 117-32.

— “Senegambian Influences on Afro-American Culture”, Black Music Research Journal, 11 (1991), 1-18.

Counsel, Graeme, “Syliphone Discography”, Radio Africa, 1999, http://www.radioafrica.com.au/Discographies/Syliphone.html

— “Popular Music and Politics in Sékou Touré’s Guinea”, Australasian Review of African Studies, 26 (2004), 26-42.

— “Music in Guinea’s First Republic”, in Mande-Manding: Background Reading for Ethnographic Research in the Region South of Bamako, ed. by Jan Jansen (Leiden: Leiden University Department of Cultural Anthropology and Development Sociology, 2004).

— “The Return of Mali’s National Arts Festival”, in Mande-Manding: Background Reading for Ethnographic Research in the Region South of Bamako, ed. by Jan Jansen (Leiden: Leiden University Department of Cultural Anthropology and Development Sociology, 2004).

— “Guinea’s Orchestras of the 1st Republic”, Radio Africa, 2006, http://www.radioafrica.com.au/Discographies/Origin.html

— Mande Popular Music and Cultural Policies in West Africa: Griots and Government Policy since Independence (Saabrücken: VDM Verlag, 2009).

— Annotations to Keletigui et ses Tambourinis: The Syliphone Years (Sterns, STCD 3031-32, 2009).

— “Music for a Coup — ‘Armée Guinéenne’: An Overview of Guinea’s Recent Political Turmoil”, Australasian Review of African Studies, 31/2 (2010), 94-112.

— “The Music Archives of Guinea: Nationalism and its Representation Under Sékou Touré”, paper presented at the 36th Conference of the African Studies Association of Australasia and the Pacific, Perth, 26-28 November 2013, http://afsaap.org.au/assets/graeme_counsel.pdf

Dave, Nomi, “Une Nouvelle Révolution Permanente: The Making of African Modernity in Sékou Touré’s Guinea”, Forum for Modern Language Studies, 45/4 (2009), 455-71.

— “The Politics of Silence: Music, Violence and Protest in Guinea”, Ethnomusicology, 58 (2014), 1-29.

Denselow, Robin, “Sound Politics”, The Guardian, 3 July 2003, http://www.theguardian.com/music/2003/jul/03/artsfeatures.popandrock

DeSalvo, Debra, The Language of the Blues: From Alcorub to Zuzu (New York: Billboard, 2006).

Diawara, Manthia, African Cinema: Politics and Culture (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1992).

du Bois, Victoire, Guinea: The Decline of the Guinean Revolution (New York: Columbia University Press, 1965).

Dukuré, Wolibo, Le festival culturel national de la République Populaire Révolutionnaire de Guinée (Conakry: Ministère de la Jeunesse des Sports et Arts Populaire, 1983).

Eyre, Banning, “Bembeya Jazz: Rebirth in 2002”, Rock Paper Scissors, 2002, http://www.rockpaperscissors.biz/index.cfm/fuseaction/current.articles_detail/project_id/102/article_id/708.cfm

Eze, Michael Onyebuchi, The Politics of History in Contemporary Africa (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2010).

Graham, Ronnie, Stern’s Guide to Contemporary African Music, 2 vols (London: Pluto Press, 1988 and 1992).

Grant, Stephen H., “Léopold Sédar Senghor, former president of Senegal”, Africa Report, 28/6 (1983), 61-64.

Guinean National Commission for UNESCO, “Cultural Policy in the Revolutionary People’s Republic of Guinea”, in Studies and Documents on Cultural Policies, 51 (Paris: UNESCO, 1979).

Hale, Thomas A., Griots and Griottes: Masters of Words and Music (Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press, 1998).

Kaba, Lansiné, “The Cultural Revolution, Artistic Creativity, and Freedom of Expression in Guinea”, The Journal of Modern African Studies, 14/2 (1976), 201-18.

Keita, Cheick M. Chérif, Outcast to Ambassador: The Musical Odyssey of Salif Keita (Saint Paul, MN: Mogoya, 2011).

Khalil, Diaré Ibrahima, Annotations to Keletigui et ses Tambourinis, JRDA/Guajira con tumbao (Syliphone, SLP 519, 1970).

Kourouma, Ibrahima, “Des productions artistiques à caractère utilitaire pour le peuple”, Horoya, 14 September 1967, pp. 1-2.

Kubik, Gerhard, Africa and the Blues (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 1999).

Lavaine, Bertrand, “Independence and Music: Guinea and Authenticity. A Politicised Music Scene”, RFI Music, 3 May 2010, http://www.rfimusique.com/musiqueen/articles/125/article_8351.asp

Makeba, Miriam, and Nomsa Mwamuka, Makeba: The Miriam Makeba Story (Johannesburg: STE, 2010).

Mandel, Jean-Jacques, “Guinée: la long marche du blues Manding”, Taxiville, 1 (1986), 36-38.

Matera, Marc, “Pan-Africanism”, New Dictionary of the History of Ideas, 2005, http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Pan-Africanism.aspx

Merriam, Alan P., “Music”, Africa Report, 13/2 (1968), 6.

Morel, Justin, Jr, Annotations to Camayenne Sofa, A grand pas (Syliphone, SLP 56, c. 1976).

Niane, Djibril Tamsir, “Some Revolutionary Songs of Guinea”, Presence Africaine, 29 (1960), 101-15.

Rivière, Claude, Guinea: The Mobilization of a People, trans. by Virginia Thompson and Richard Adloff (London: Cornell University Press, 1977).

Sampson, Aaron, “Hard Times at the National Library”, Nimba News, 22 August 2002, pp. 1 and 6.

Schachter, Ruth, “French Guinea’s RDA Folk Songs”, West African Review, 29 (August 1958), 673-81.

Schachter Morgenthau, Ruth, Political Parties in French-Speaking West Africa (Oxford: Clarendon, 1964).

Schmidt, Elizabeth, “Emancipate Your Husbands! Women and Nationalism in Guinea, 1953-1958”, in Women in African Colonial Histories, ed. by Jean Allman, Susan Geiger and Nakanyike Musisi (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2002).

— Mobilizing the Masses: Gender, Ethnicity, and Class in the Nationalist Movement in Guinea, 1939-1958 (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2005).

— Cold War and Decolonization in Guinea, 1946-1958 (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2007).

Sweeney, Philip, “Concert Review”, Rock Paper Scissors, 29 June 2003, http://www.rockpaperscissors.biz/index.cfm/fuseaction/current.articles_detail/project_id/102/article_id/885.cfm

Touré, Sékou, “The Political Leader Considered as the Representative of a Culture”, Blackpast.org, 1959, http://www.blackpast.org/1959-sekou-toure-political-leader-considered-representative-culture

— “Le racism Peulh, nous devons lui donner un enterrement de première classe, un enterrement définitif”, Horoya, 29 August-4 September 1976, p. 34.

Wald, Elijah, “Spirit Voices”, Acoustic Guitar, 4 (1994), 64-70.

Archival materials

Syliphone2-028-01 – Syliphone2-028-07. Bembeya Jazz National, 1973.

Syliphone2-038-01 – Syliphone2-038-04. Ismaila Diabaté, 1960.

Syliphone2-052-01 – Syliphone2-052-04. Kébendo Jazz, 1964.

Syliphone2-053-01 – Syliphone2-053-05. Orchestre de la Brigade Féminine, 1964.

Syliphone2-060-01 – Syliphone2-060-06. Orchestre de la Paillote, 1963.

Syliphone2-064-02 – Syliphone2-064-03. Kébendo Jazz, 1964.

Syliphone2-067-01 – Syliphone2-067-06. Orchestre de la Garde Républicaine - 1ère Formation, 1964.

Syliphone2-068-01 – Syliphone2-068-07. Orchestre Honoré Coppet, 1963.

Syliphone3-042-01 – Syliphone3-042-05. Kouyaté Sory Kandia, c. 1973.

Syliphone3-091-01 – Syliphone3-091-05. Kemo Kouyaté, 1977.

Syliphone3-213-06 – Syliphone3-213-10. Orchestre Féminin de Mamou, 1970.

Syliphone3-248-01 – Syliphone3-248-11. Syli Orchestre National, c. 1962.

Syliphone4-007-01 – Syliphone4-007-06. Orchestre de la Garde Républicaine, 1964.

Syliphone4-047-01 – Syliphone4-047-04. Virtuoses Diabaté, c. 1973.

Syliphone4-105-01 – Syliphone4-105-06. Orchestre de la Garde Républicaine - 1ère Formation, 1963.

Syliphone4-165-01 – Syliphone4-165-10. Fodé Conté (“Kini Bangaly”), c. 1978.

Syliphone4-202-01 – Syliphone4-202-03. Kouyaté Sory Kandia, c. 1971.

Syliphone4-354-01 – Syliphone4-354-11. Orchestre de la Garde Républicaine, 1970.

Syliphone4-382-01 – Syliphone4-382-13. Orchestre Féminin Gendarmerie Nationale, 1963.

Syliphone4-681-01 – Syliphone4-681-04. Mory and Madina Kouyaté, 1960.

Syliphone4-698-01 – Syliphone4-698-06. Miriam Makeba, c. 1973.

Syliphone4-717-01 – Syliphone4-717-05. Orchestre du Jardin de Guinée, c. 1963.

Syliphone4-739-01 – Syliphone4-739-07. Orchestre de la Paillote, 1963.

African Journey: A Search for the Roots of the Blues. Volumes 1 and 2 (Sonet, SNTF 666/7, 1974).

Authenticité: The Syliphone Years. Guinea’s Orchestres Nationaux and Fédéraux 1965-1980 (Sterns, STCD 3025-26, 2007).

Balla et ses Balladins, Fadakuru (Syliphone, SLP 47, 1975).

Balla et ses Balladins, Soumbouyaya (Syliphone, SLP 2, c. 1967).

Balla et ses Balladins: The Syliphone Years (Sterns, STCD 3035-36, 2008).

Bembeya Jazz National, Sabor de guajira (Syliphone, SYL 503, c. 1968).

Bembeya Jazz National, Regard sur le passé (Syliphone, SLP 10, c. 1969).

Bembeya Jazz National: The Syliphone Years. Hits and Rare Recordings (Sterns, STCD 3029-30, 2007)

Keletigui et ses Tambourinis, Kesso/Chiquita (Syliphone, SYL 513, c. 1970).

Keletigui et ses Tambourinis: The Syliphone Years (Sterns, STCD 3031-32, 2009).

Kouyaté Sory Kandia (Syliphone, SLP 12, 1970).

Mama Kanté and l’Ensemble Instrumental et Vocal de Kissidougou, Simika (Syliphone, SLP 29, 1971).

Orchestre de la Garde Républicaine, Tara (Syliphone, SLP 6, c. 1967).

Pivi et les Balladins, Manta lokoka (Syliphone, SYL 549, 1972).

Quintette Guinéenne, Massané Cissé (Syliphone, SLP 54, c. 1976).

Interviews by the author

Linké Condé, Chef d’orchestre Keletigui et ses Tambourinis, Conakry, 18 September 2009 and 24 December 2013.

Balla Onivogui, Chef d’orchestre Balla et ses Balladins, Conakry, 14 August 2001.

Métoura Traoré, Chef d’orchestre Horoya Band National, Conakry, 21 August 2001.

1 Graeme Counsel, Mande Popular Music and Cultural Policies in West Africa: Griots and Government Policy since Independence (Saabrücken: VDM Verlag, 2009).

2 Griot is the French term for these musicians. It denotes a male musician, with griotte referring to a female musician. In this text it is used in a non-gender specific sense. Local terms for griots include djely and djelymoussou, for the male and female musician respectively.

3 Debra DeSalvo, The Language of the Blues: From Alcorub to Zuzu (New York: Billboard, 2006), p. 116.

4 Thomas A. Hale, Griots and Griottes: Masters of Words and Music (Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press, 1998); Eric Charry, Mande Music: Traditional and Modern Music of the Maninka and Mandinka of Western Africa (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2000); and Counsel, Mande Popular Music.

5 Ronnie Graham, Stern’s Guide to Contemporary African Music, 2 vols (London: Pluto Press, 1988 and 1992); John Collins, West African Pop Roots (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1992); and Charry, Mande Music.

6 In addition to the Syliphone catalogue, I have created discographies of major West African recording labels including N’Dardisc, Mali Kunkan, Volta Discobel, Safie Deen, Djima, Club Voltaïque du Disque and Société Ivoirienne du Disque. These are located at my web site, Radio Africa, http://www.radioafrica.com.au

7 Graeme Counsel, “Popular Music and Politics in Sékou Touré’s Guinea”, Australasian Review of African Studies, 26/1 (2004), 26-42; and idem, “Music in Guinea’s First Republic” and “The Return of Mali’s National Arts Festival”, in Mande-Manding: Background Reading for Ethnographic Research in the Region South of Bamako, ed. by Jan Jansen (Leiden: Leiden University Department of Cultural Anthropology and Development Sociology, 2004).

8 Ruth Schachter Morgenthau, Political Parties in French-Speaking West Africa (Oxford: Clarendon, 1964).

9 Claude Rivière, Guinea: The Mobilization of a People, trans. by Virginia Thompson and Richard Adloff (London: Cornell University Press, 1977).

10 Counsel, Mande Popular Music, p. 73; and Don R. Browne, “Radio Guinea: A Voice of Independent Africa”, Journal of Broadcasting, 7/2 (1963), 113-22 (pp. 114-15).

11 Victoire du Bois, Guinea: The Decline of the Guinean Revolution (New York: Columbia University Press, 1965), pp. 122-23.

12 Elizabeth Schmidt, “Emancipate Your Husbands! Women and Nationalism in Guinea, 1953-1958”, in Women in African Colonial Histories, ed. by Jean Allman, Susan Geiger and Nakanyike Musisi (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2002), p. 50.

13 Sékou Touré, “The Political Leader Considered as the Representative of a Culture”, Blackpast.org, 1959, http://www.blackpast.org/1959-sekou-toure-political-leader-

considered-representative-culture

14 Ibid.

15 Schmidt, “Emancipate Your Husbands!”, p. 287; and idem, Cold War and Decolonization in Guinea, 1946-1958 (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2007), p. 74.

16 African “orchestras” of this era should not be confused with concepts of classical music orchestras. Rather, they should be considered as “dance orchestras” (a widely used local term) in the vein of jazz-style or Cuban-style groups, first popular in the 1930s, whose instrumentation includes: a brass section comprising of alto and tenor saxophones, and trumpets; three to four electric guitars, including bass; timbales; congas; claves; and a drum kit. Ten or more musicians and singers comprise an average orchestra in the African context. See Collins, West African Pop Roots; Charry, Mande Music; and Counsel, Mande Popular Music.

17 Guinean National Commission for UNESCO, “Cultural Policy in the Revolutionary People’s Republic of Guinea”, in Studies and Documents on Cultural Policies, 51 (Paris: UNESCO, 1979), p. 80; and Jean-Jacques Mandel, “Guinée: La long marche du blues Manding”, Taxiville, 1 (1986), 36-38.

18 Sékou Camara, “Sékou Camara dit le Gros, membre-fondateur du Bembeya Jazz National de Guinée”, interview by Awany Sylla, Africa Online, 20 December 1998.

19 Browne, “Radio Guinea", pp. 114-15; and Gérald Arnaud, “Bembeya se réveille”, Africultures, 1 November 2002, http://www.africultures.com/php/?nav=article&no=2626

20 Wolibo Dukuré, La festival culturel national de la République Populaire Révolutionnaire de Guinée (Conakry: Ministère de la Jeunesse des Sports et Arts Populaire, 1983), p. 58 (translation mine).

21 Interview with Linké Condé, Chef d’orchestre Keletigui et ses Tambourinis, Conakry, 24 December 2013. All interviews were conducted by the author, unless otherwise stated.

22 Bertrand Lavaine, “Independence and Music: Guinea and Authenticity. A Politicised Music Scene”, RFI Music, 3 May 2010, http://www.rfimusique.com/musiqueen/articles/125/article_8351.asp; and Mandel, pp. 36-38.

23 Leopold Senghor, cited in Stephen H. Grant, “Léopold Sédar Senghor, Former President of Senegal”, Africa Report, 28/6 (1983), 61-64 (p. 64).

24 Michael Onyebuchi Eze, The Politics of History in Contemporary Africa (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2010), p. 120.

25 Bembeya Jazz National, Regard sur le passé (Syliphone, SLP 8, c. 1968). See also Lansiné Kaba, “The Cultural Revolution, Artistic Creativity, and Freedom of Expression in Guinea’, The Journal of Modern African Studies, 14/2 (1976), 201-18.

26 Cited in Ladipo Adamolekun, Sékou Touré’s Guinea: An Experiment in Nation Building (London: Methuen, 1976), p. 365.

27 Counsel, Mande Popular Music, pp. 281-83; Nomi Dave, “Une Nouvelle Révolution Permanente: The Making of African Modernity in Sékou Touré’s Guinea”, Forum for Modern Language Studies, 45/4 (2009), 455-71; and Philip Sweeney, “Concert Review”, Rock Paper Scissors, 29 June 2003, http://www.rockpaperscissors.biz/index.cfm/fuseaction/current.articles_detail/project_id/102/article_id/885.cfm

28 Interview with Balla Onivogui, chef d’orchestre Balla et ses Balladins, Conakry, 14 August 2001; and Lavaine, “Independence and Music”.

29 Interview with Onivogui.

30 Dukuré, Le festival culturel national.

31 Interview with Mamouna Touré in Ibrahima Kourouma, “Des productions artistiques a caractere utilitaire pour le peuple”, Horoya, 14 September 1967, pp. 1-2.

32 Annotations to Disque souvenir du Premier Festival National de la Culture. Conakry – du 9 au 27 mars 1970. Folklores de Guinée (Syliphone, SLP 18, 1970).

33 Anonymous, “De la Révolution Culturelle”, Horoya, 30 August 1968, p. 2.

34 Dave, “Une Nouvelle Révolution Permanente”, p. 465.

35 Mohamed Saliou Camara, His Master’s Voice: Mass Communication and Single Party Politics in Guinea under Sékou Touré (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2005); and Manthia Diawara, African Cinema: Politics and Culture (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1992).

36 Anonymous, “Création en Guinée d’une Régie d’édition et d’Exploitation du disque ‘Syliphone’”, Horoya, 16 May 1968, p. 2.

37 Joshua Cohen, “Stages in Transition: Les Ballets Africains and Independence, 1959 to 1960”, Journal of Black Studies, 43/1 (2012), 11-48.

38 Miriam Makeba and Nomsa Mwamuka, Makeba: The Miriam Makeba Story (Johannesburg: STE, 2010), p. 120.

39 The Quintette Guinéenne was comprised of musicians allocated from the national orchestra Balla et ses Balladins.

40 Browne, “Radio Guinea", pp. 114-15.

41 Ibid., p. 115.

42 Robin Denselow, “Sound Politics”, The Guardian, 3 July 2003, http://www.theguardian.com/music/2003/jul/03/artsfeatures.popandrock

43 Bureau Politique du Mouvement Populaire de la Révolution, Authenticité, l’Etat et le parti au Zaïre (Zaïre: Institut Makanda Kabobi, 1977).

44 L’Ensemble Instrumental et Choral de la Radio-diffusion Nationale, Victoire à la révolution (Syliphone, SLP 29, 1971).

45 Balla et ses Balladins, Fadakuru (Syliphone, SLP 47, 1975).

46 Orchestre de la Garde Républicaine, Tara (Syliphone, SLP 6, c. 1967).

47 Bembeya Jazz National, Sabor de guajira (Syliphone, SYL 503, c. 1968); and Sweeney.

48 Diaré Ibrahima Khalil, annotations to Keletigui et ses Tambourinis, JRDA/Guajira con tumbao (Syliphone, SLP 519, 1970).

49 Pivi et les Balladins, Manta lokoka (Syliphone, SYL 549, 1972).

50 Quintette Guinéenne, Massané Cissé (Syliphone, SLP 54, c. 1976).

51 Interview with Métoura Traoré, Chef d’orchestre Horoya Band National, Conakry, 21 August 2001.