2. Metadata and endangered archives:

lessons from the Ahom Manuscripts Project

© Stephen Morey, CC BY http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0052.02

Since 2011, the project EAP373: Documenting, conserving and archiving the Tai Ahom manuscripts of Assam has been, with the help of the British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme, digitising and documenting the written legacy of the Tai Ahom.1 It has done this in three ways: by photographing and cataloguing Ahom manuscripts, and archiving the resulting digital materials at the British Library; by archiving digital photographs with our partners at the Institute for Tai Studies and Research (Moran, India), Gauhati University (Guwahati, India) and Dibrugarh University (Dibrugarh, India); and by making images and metadata universally available online through the Center for Research in Computational Linguistics, where they will be integrated with existing search tools developed under the Ahom Lexicography project2 and the Tai and Tibeto-Burman languages of Assam website.3

Between October 2011 and the middle of 2014, the project photographed 411 manuscripts owned by around fifty different persons — a total of nearly 15,000 images. All materials will be available online through the EAP website in combination with basic metadata. Around twenty different manuscripts have been transcribed, of which around ten have been translated in full or in part.4

The methodology of the project followed these steps:

- Locating the manuscripts

- Seeking permission from the owners for them to be copied

- Cleaning and ordering the manuscripts

- Photography

- Data management

- Metadata preparation

- Transcription

- Translation and revision of metadata

While it may seem obvious that the photographing, archiving and long-term preservation of these manuscripts is a good idea, this has not always been apparent to the manuscript owners, who are members of the Tai Ahom priestly caste. Not all of them have allowed us to take photographs for a variety of reasons. For example, there is a belief among some of some of the priestly families that the knowledge contained in the manuscripts should not be shared, and this belief has to be respected; however, the injunction presented as Example 14 below, in our opinion, shows that in the minds of earlier copyists and custodians the knowledge in these manuscripts should be made available. Secondly, since many aspects of Tai Ahom culture have been lost in the last 300 years, those portions of the culture that remain — of which the manuscripts are a large part — become even more important to the community, and there is a sense in which these should not be shared casually with outsiders.

We had a number of meetings with community leaders in different villages to discuss and explain the project, answer questions, and present our work. One of the achievements of the overall project, the online Tai Ahom dictionary,5 was a big argument in favour of our project. Despite some difficulties, most of the manuscript owners have been pleased to have the manuscripts photographed and those photographs preserved and available for study.6

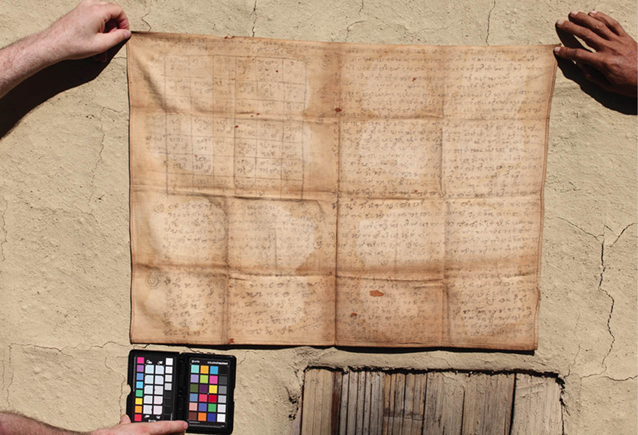

The actual photography itself is not always an easy process. We used a camera with a fixed distance lens to avoid distortion at the edges of the shot. For most manuscripts this worked well. Ban Seng manuscripts, for example, were often only approximately 5 cm wide and 8 cm long. But with a large manuscript it was often necessary to stand far above the manuscript to get a shot of the whole page. Du Kai Seng manuscripts were typically much larger, as much as 12 cm wide and 47 cm long. Even bigger were cloth manuscripts (usually with the text Phe Lung Phe Ban). The following photograph (Fig. 2.1) shows Iftiqar Rahman taking photos of a large nineteenth-century paper manuscript, a Phe Lung Phe Ban belonging to Hara Phukan of Amguri Deodhai village, in which each page was approximately 35 cm wide and 45 cm long.7

Fig. 2.1 Iftiqar Rahman photographing the Phe Lung Phe Ban paper manuscript belonging to Hara Phukan. Photo by Poppy Gogoi, CC BY.

Before taking the photographs, a good deal of time was needed to organise the manuscripts at every site so that they were photographed in page order, whenever possible (see below for a more in depth discussion of the issues involved in page ordering). For example, in one house we found one complete text (which was probably a nineteenth-century copy of a text not yet photographed anywhere else), and all the older manuscripts arranged by the owner into two groups. But these two groups turned out to be parts of at least six different manuscripts, and portions of the two largest of these were found in each of the two groups. None of them were complete, and so before we could photograph them, it was essential to group them as best we could, a process that took a great deal more time than the photography itself.

The Tai Ahom

The Tai Ahom are descendants of Tai speaking people, led by King Siukapha, whose traditional date of arrival in Northeast India is 1228.8 Linguistically, Tai Ahom is one of a group of Tai languages that is classified as part of Southwestern Tai, because the historical home of speakers of these varieties is in the southwestern area of the Tai speaking world (Thailand, southwestern China, Laos and Myanmar).9

Unlike Tai Ahom, most of other communities speaking Southwestern Tai languages are Buddhist.10 Several of them, for example the Tai Khamyang and Tai Phake in India, also still practice ancient Tai rituals described in Tai Ahom manuscripts, such as spirit calling. These rituals, together with chicken bone augury, are observed by more distantly related linguistic groups, such as Zhuang in China.11

The linguistic forms and the literature recorded in Tai Ahom manuscripts are believed to represent one of the oldest examples of Tai language for which we have records. Where a Tai Ahom manuscript is dated, the date is that of its copying, and most of these are late eighteenth or early nineteenth century. In the opinion of Chaichuen Khamdaengyodtai, who has assisted with the identification and translation of some manuscripts, the texts are much older, although there is no way of ascertaining their exact age.

The Ahom Kingdom ruled in Northeast India until the early nineteenth century, but over time the Ahom community assimilated with the Assamese speaking majority, and the Tai Ahom language was lost as a mother tongue by about 1800.12 Today, most Tai Ahom people are Assamese speaking, probably mostly monolingual, and are followers of Hinduism. Nevertheless, the language does survive in some ritual contexts, such as the Me Dam Me Phi ritual celebrated on 31 January every year. This festival became a public event in the 1970s, and the date of 31 January was gazetted as a public holiday in Assam some time after that. The authenticity of rituals such as this is not uncontested. For example, B. J. Terwiel reported that “So far I have come across no record of the state ritual of Medam Mephi being performed before the 1970s,” adding that he believed the Ahom rituals were “created” in the 1960s.13 On the other hand, my consultants have maintained that the Me Dam Me Phi ceremony was held since time immemorial in private houses prior to its becoming a public ritual in the 1970s, using some of the prayers found also in manuscript form.

The Ahom manuscripts

Regardless of the authenticity of these rituals, there is no doubt about the authenticity of the manuscripts that preserve the Tai Ahom language in a wide range of styles. While a number of manuscripts are held in public institutions in Assam, such as the Department of Historical and Antiquarian Studies in Guwahati, the Tai Museum in Sibsagar, and the Institute of Tai Studies and Research in Moran, the large majority of Tai Ahom manuscripts are kept in the homes of members of the Ahom priestly caste, many of whom no longer know the language and cannot read the texts. These manuscripts are often kept very well — nicely wrapped and regularly cleaned and kept free of insects. However, by the time we came to see some of the manuscripts, they were seriously damaged by water, damp or insects, with pages out of order and portions of different manuscripts kept together. Our photography sessions thus often involved time spent on cleaning manuscripts.14

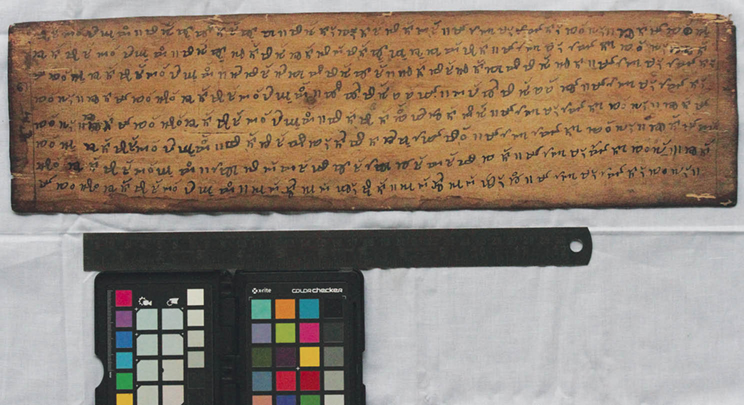

Most of the surviving manuscripts photographed in the project were copied in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth centuries, although the tradition of manuscript copying is continuing. These older manuscripts are overwhelmingly written on bark from the sasi tree (Aquillaria Agallocha), which is cut, scraped and dried for some time before it can be used. In many traditional Tai Ahom gardens, a sasi tree can still to be found. Apart from the bark manuscripts, there are a smaller number of manuscripts written on Assamese style silk, or other cloths. These usually contain the Phe Lung Phe Ban text of calendrically related predictions (discussed in more detail below). An example of one such silk manuscript is owned by Tileshwar Mohan of Parijat village, measuring approximately 50 cm wide and 68 cm long (Fig. 2.2).15

Fig. 2.2 The Phe Lung Phe Ban cloth manuscript

belonging to Tileshwar Mohan (EAP373), CC BY.

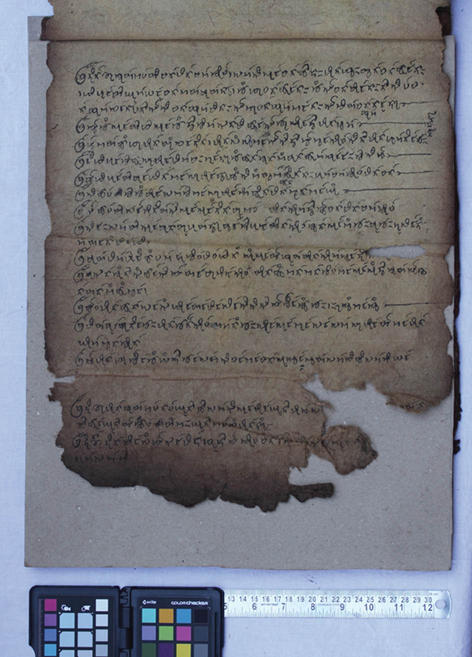

For the modern day Tai Ahom community, these manuscripts represent a link to their long history, commencing with the arrival of King Siukapha in 1228 AD. From at least the late nineteenth century and throughout the early twentieth century, members of the Tai Ahom priestly caste continued copying the manuscripts,16 but although a small number of manuscripts are still copied onto sasi bark, in most of the collections that we have been able to study and photograph, the later manuscripts are written on paper. This paper was usually of a much poorer quality than the bark, as can be seen in the image below (Fig. 2.3). Most of the paper manuscripts are probably not as important as the old bark manuscripts, from the point of view of the texts they contain at least, but we have photographed them when possible. Sometimes they contain versions of texts that are incomplete in the bark manuscripts, and when eventually these are studied in detail, the paper manuscripts may become invaluable. An example of such a manuscript is the Phe Lung Phe Ban belonging to Hara Phukan, mentioned earlier.

Fig. 2.3 The Phe Lung Phe Ban manuscript

belonging to Hara Phukan (EAP373), CC BY.

Apart from the sasi bark, cloth and paper manuscripts, the Ahom script was also used on brass plates, coins17 and some inscriptions on stone, the most famous of which is the Snake Pillar at Guwahati Museum.18 We did not photograph any examples of these. In the manuscripts that we did photograph, the copying date and the name and location of the copyist are often given, occasionally together with the name of the manuscript.

The dates are usually in the sixty-year Lakni cycle, a calendrical cycle used for both years and days. The Lakni cycle names the year by means of two series of terms used in combination, as in Kat Kau. The first element, Kat is one of ten words that are used in the first position, combining with the second element, Kau, which is one of twelve terms used in second position.19 Altogether sixty combinations are used and the cycle starts again after sixty years. With a Lakni date alone, such as Kat Kau, we cannot tell if a manuscript was copied in 1805 or sixty years early in 1745, or even sixty years earlier than that. Sometimes additional information is given and the date can be more certain. For example, on line four of the last page of manuscript Khun Lung Khun Lai, owned by Tulsi Phukan of Sibsagar district (Fig. 2.4), the date is given as Lakni era Kat Kau, eighth month, in the time of King Kamaleshwar Singh (reigned 1795-1811). Thus this particular Kat Kau year corresponds to 1805.20

Fig. 2.4 Folio 33r of the Khun Lung Khun Lai manuscript

belonging to Tulsi Phukan (EAP373), CC BY.

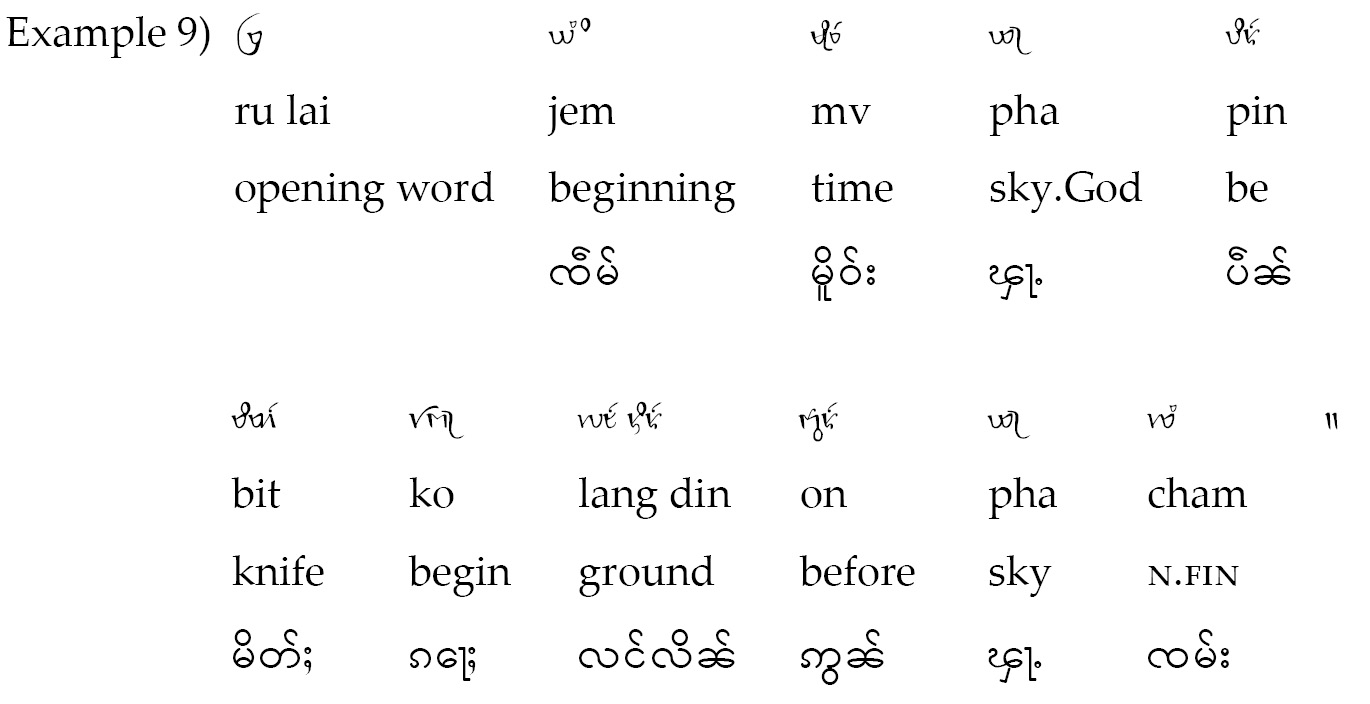

The section containing the name and date and other information, including the name of the text, Khun Lung Khun Lai commences with several ru lai symbols, illustrated below as the opening of Example 9. This symbol is used to mark a new paragraph or section within a manuscript. This section begins with the date,  (lak ni kat kau). The second sentence names the king as

(lak ni kat kau). The second sentence names the king as  (ko mo las por), the nearest Tai Ahom spelling for the Assamese name. It also names the location as Song Su Kat, an old name for the city of Jorhat.

(ko mo las por), the nearest Tai Ahom spelling for the Assamese name. It also names the location as Song Su Kat, an old name for the city of Jorhat.

The pages of the manuscripts are usually numbered, using either Ahom numerals or Ahom numbers spelled out in letters, or a combination of both; in a few cases the Lakni cycle is used to number pages. Generally pages are numbered on the verso side, but not always. The manuscript Sai Kai owned by Padma Sangbun Phukan of Amguri has numbering on the recto side.21 We did not realise this when the manuscript was photographed. At that time it was arranged in order assuming that pages were numbered on the back so that, after photographing the cover (images 0001 and 0002), the correct order of the images is 0004, 0003, 0006, 0005, 0008, 0007, etc, something that was only discovered as a result of working on a translation of the whole text. There are probably other manuscripts photographed in the wrong order, because we did not have the chance to carefully examine the text.

Most of these manuscripts have never been translated, because (a) Tai Ahom language is no longer spoken or indeed understood by most of the manuscript owners, (b) most of the manuscripts have never been photographed or published in any way and have not been available for study, (c) much of the ritual connected with the manuscripts is no longer practiced, making some of the references in the texts impossible to understand, and (d) the Ahom script under-specifies the sound distinctions in the languages, meaning that often a single syllable represents several different pronunciations and meanings. The EAP project has to a large extent overcome (b), by making photographs of over 400 texts. Before discussing points (c) and (d) in detail, the following section will briefly survey the kind of manuscripts that have been found.

Types of Ahom manuscripts

The Tai Ahom manuscripts that we have photographed are of the following types:

- History (Buranji)22

- Creation stories

- Spirit calling texts

- Khon Ming Lung Phai (lung “large”)

- Khon Ming Kang Phai (kang “middle”)

- Khon Ming Phai Noi (noi “small”

- Mantras and prayers

- Predictions and augury

- Phe Lung Phe Ban

- Du Kai Seng (chicken bone augury)

- Ban Seng

- Other priestly texts, relating to the performance of rituals, such as those translated in Tai Ahoms and the Stars23

- Calendar (Lakni)

- Stories

- Traditional Tai stories

- Stories of Buddhist origin

- Lexicons (Bar Amra, Loti Amra)24

- Writing Practice, manuscripts that involve copying the written syllables of Tai Ahom in alphabetical order, presumably used to teach the script

The most common texts are probably those relating to prediction and augury (e), with each of the three manuscript types listed there being found in multiple copies from a variety of owners.25 For example, one manuscript owner, Kesab Baruah of Amguri Deodhai village, possesses no fewer than nine separate versions of the Du Kai Seng text, which is used for the interpretation of chicken bones after sacrifice. There are multiple examples of each of the categories listed above, and future students of these manuscripts will, in time, be able to compare different versions of the same text.

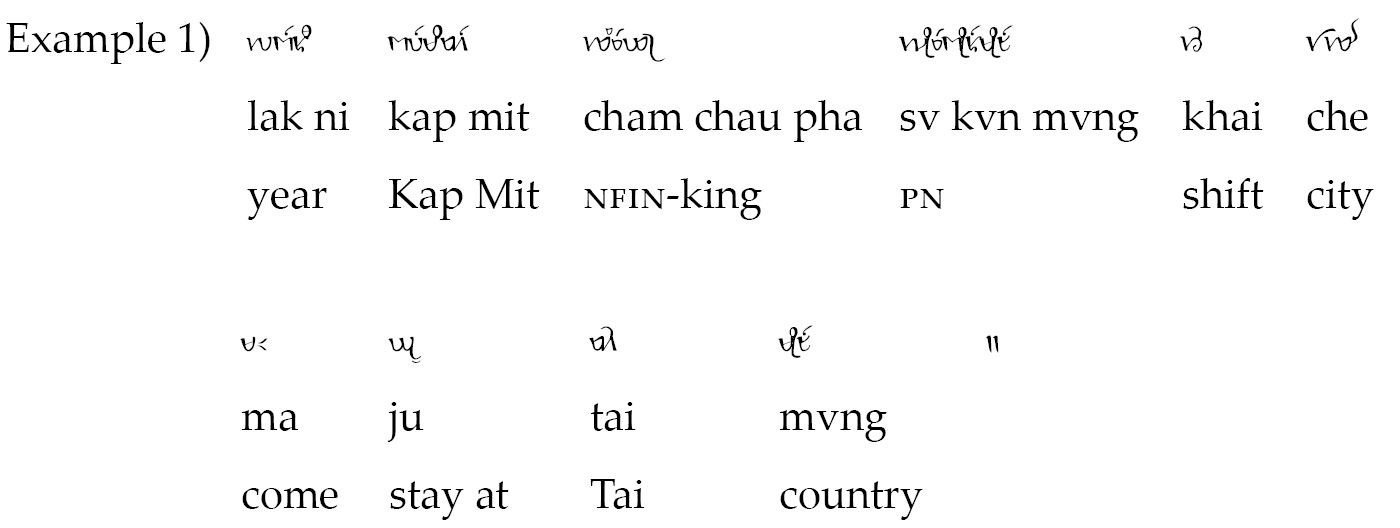

The most widely known texts, both among the Ahom community themselves and among the wider community, are the histories or Buranjis. One set of Buranji manuscripts was translated by G. C. Barua, with two parallel texts, one in Ahom (using Ahom script) and the other an English translation.26 It is relatively easy to match the two texts and thus make an in-depth study of the translation, but because Barua’s knowledge of Ahom was sketchy, the translation is not reliable. It is, however, a widely available book that has been reprinted several times. The Buranji texts have been translated more recently into Standard Thai by Ranoo Wichasin.27 To illustrate the problems with Barua’s translation, consider Example 1.28 Our analysis, based on Ranoo’s translation relies on the reading of the phrase khai che as “shift city”.

“In the year Kap Mit, King Svkvnmvng shifted his (capital) city to Tai Mvng”.

As we will see in more detail below, the same syllable in Tai Ahom can have a number of meanings, and khai could mean “shift”, “ill”, “tell” and several other possibilities. Barua’s original translation for this line was “In Lākni Kapmit (i.e., in 1540 AD) Chāophā Shuklenmung fell ill. He proceeded to Tāimung and stopped there”, reading khai as “ill” which- would make sense if not for the fact that it is followed by che. The combination of khai che, however, only makes sense in the meaning “shift city”.

One of the surprising findings of our project so far is the significant number of manuscripts containing stories that appear to be of Buddhist origin. For example, the Nemi Mang story, one of the previous lives of the Buddha,29 is found on folios 47r-66v of the manuscript owned by Gileswar Bailung Phukan of Patsako.30 The greater part of the manuscript is a story which is ultimately named in the text as Alika,31 which from its form and content is likely to be a Buddhist story also.32 Only a more in-depth study of all of the texts identified as stories will be able to establish how many of them are of Buddhist origin.

The extent of Buddhist influence within the historical Ahom Kingdom is a matter of controversy among the Ahom community, with some people, particularly some of those connected with the royal caste (Rajkonwar), expressing the view that the Tai Ahom were traditionally Buddhist, while others maintain that this was not so. The place of Buddhism, as distinct from both the traditional Ahom rituals of sacrifice and prayer to the ancestor spirits, and the Hindu worship gradually adopted by the Ahoms after 1500, is a matter for further research, but the manuscripts can help with this. Not only are there Buddhist texts, like Nemi Mang, but also, as we will discuss in more detail below, Buddhist features are found in some of the Ahom prayers (mantras) that are still in use.

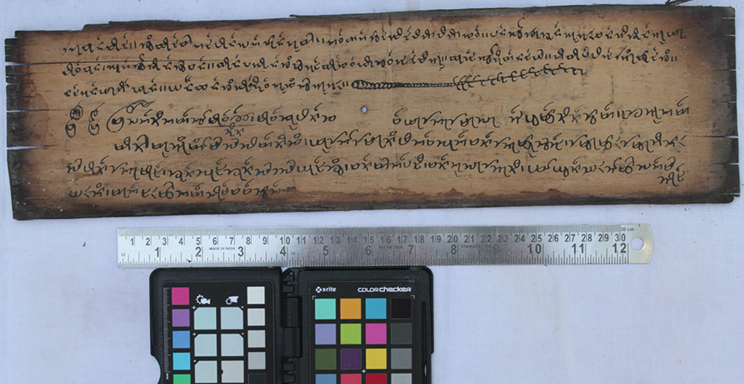

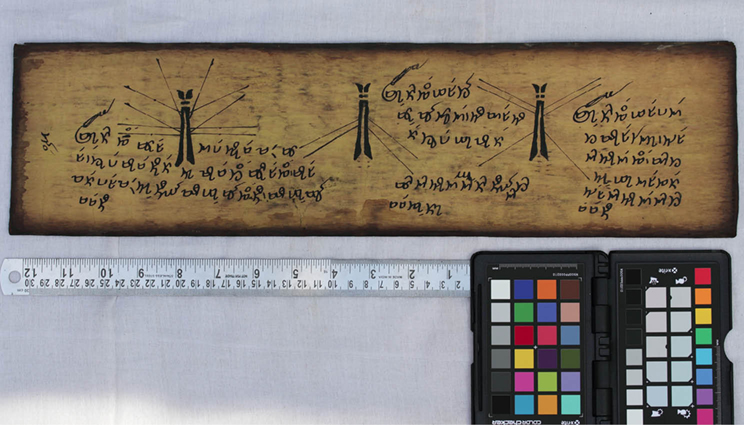

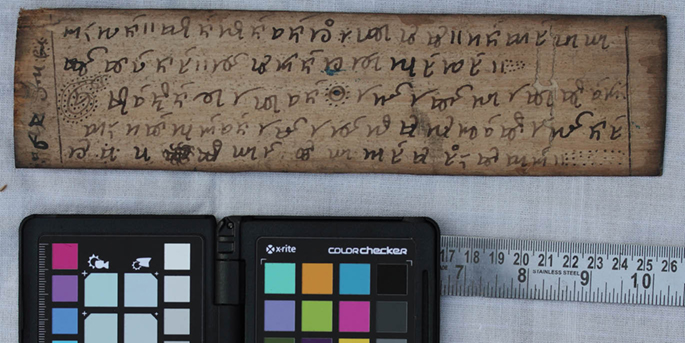

The Buddhist manuscripts and histories are relatively easy to translate because in the case of histories, much of the detail is confirmed by Assamese language sources,33 and in the case of Buddhist manuscripts, the stories are often known from other Buddhist sources.34 However the other categories are more challenging. For example the Du Kai Seng (chicken bone augury) and Ban Seng (augury) texts — listed above under the general category “Predictions and Augury” — are often very short with little context. In our experience, both these kinds of texts contain no copying dates and no information about the copyist. Nothing is known about the age of the texts, but the existence of similar texts among the Zhuang in China suggests that these are very old. The Du Kai Seng contains an illustration of the way chicken bones can appear, and then a short piece of text explaining what this means, usually concluding with ni jav “it is good” or bau ni “it is not good”. This is exemplified by an example belonging to Tileshwar Mohan, of Parijat village (Fig. 2.5).

Fig. 2.5 Folio 9r of the Du Kai Seng manuscript

belonging to Tileshwar Mohan (EAP373), CC BY.

There are small pictures in the manuscript showing chicken bones and small sticks. After sacrifice and cleaning, the chicken bones are found to have tiny holes in them. Sticks are then placed in these holes and this is compared with the drawings in the manuscript to establish the meaning. In the example illustrated here (Fig. 2.5), we see that both the bone on the left, and that on the right, are un-auspicious, with both predictions ending in  (bau ni) “not good”.

(bau ni) “not good”.

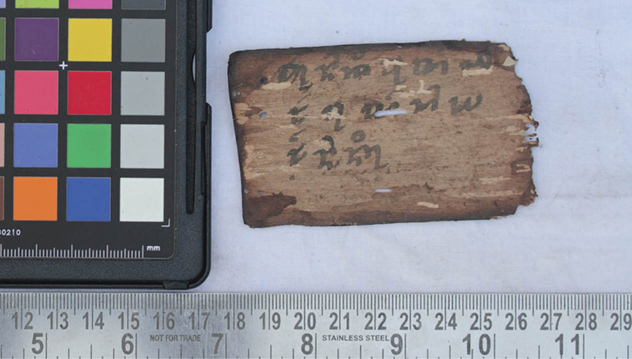

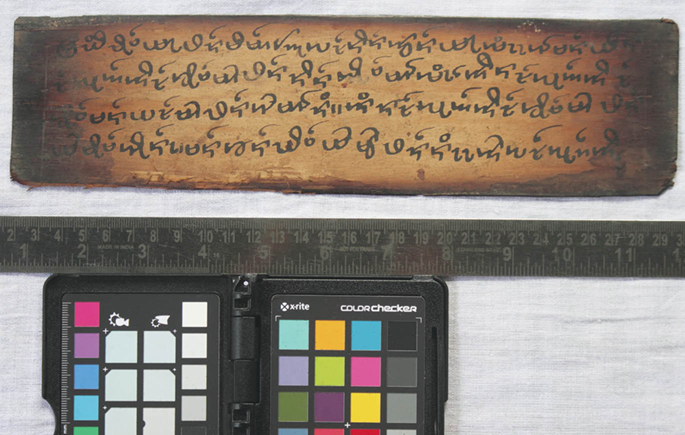

Ban Seng texts are even shorter, containing one page per prediction and a small piece of bone, or perhaps tooth, that is used to choose one of the pages when the augurer is searching for the right prediction. We have not yet translated examples of either of these texts. Ban Seng texts are tiny in size, and are exemplified by a manuscript owned by Bhim Kanta Phukan at Simaluguri (Fig. 2.6).

Fig. 2.6 A page from one of the Ban Seng manuscripts

belonging to Bhim Kanta Phukan (EAP373), CC BY.

The challenges of interpreting Tai Ahom manuscripts

In order to classify the manuscripts photographed, something needs to be said about the content. As already mentioned at the very beginning of this paper, the best metadata would be that which allows for the greatest usability, and the thing that most people will want to be able to do with Ahom manuscripts is to understand their content. However, the translation of Tai Ahom manuscripts is a challenging task, and in this section we will detail the reasons for that, which are related to the structure of the Tai language.

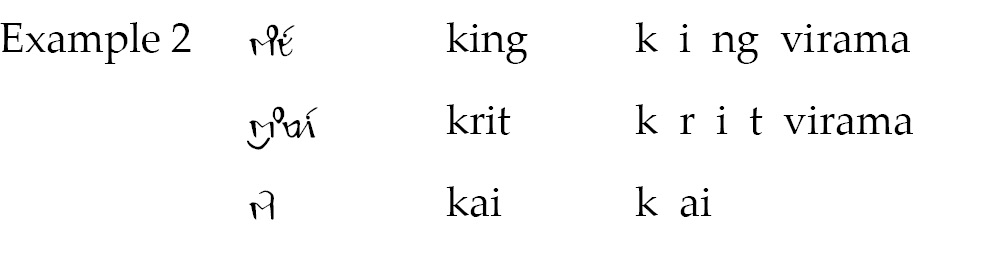

Tai languages are tonal, and most words are single syllables (monosyllables) consisting of up to five elements:35 an optional initial consonant; an optional second consonant (/y/, /r/, /w/); a vowel; a tone; and an optional final consonant (/ŋ/, /n/ or /m/), written followed by a virama,36 or a second vowel (/i/, /ɯ/ or /u/). The traditional Tai scripts used in Northeast India and most of Myanmar did not mark all the vowel distinctions, and did not mark tone at all.37 Some examples of Ahom words are given in Example 2, with their pronunciation and an explanation of each symbol.38

There are several differences between this kind of writing system and the alphabetic system used in the Roman script. First of all, the vowels, exemplified here by /i/, are written as diacritics to the consonant, in the case of /i/ as an oval shaped symbol above the consonant. Secondly, where there is a consonant cluster, as in the word krit, the second consonant is written as an attachment to the initial consonant. Standing by itself, /r/ is written as  , but as the second consonant in a cluster it takes a different form.

, but as the second consonant in a cluster it takes a different form.

All written syllables in Tai Ahom and related languages can be pronounced in a number of ways with a range of meanings. Consider again the first word in Example 2, which it is suggested was pronounced /king/. We cannot be sure that it was not /keng/ or /kɛng/. Several of the spoken languages closely related to Tai Ahom (Shan, Khamti, Tai Phake) have nine distinct vowels (and a length distinction between /a/ and /aa/), but only five or six vowel symbols. Thus, in Tai Phake a word written <king> would look like  (the equivalent in Phake of the Ahom script above), but this can be pronounced as /keng/ or /kɛng/ as well as /king/, because in stop and nasal final syllables these three different vowels are all written identically.39 In addition, there are six contrastive tones in Phake. There are thus eighteen possible pronunciations in Tai Phake for the word written king, and of those, twelve different meanings have recorded for eight of the possible pronunciations.

(the equivalent in Phake of the Ahom script above), but this can be pronounced as /keng/ or /kɛng/ as well as /king/, because in stop and nasal final syllables these three different vowels are all written identically.39 In addition, there are six contrastive tones in Phake. There are thus eighteen possible pronunciations in Tai Phake for the word written king, and of those, twelve different meanings have recorded for eight of the possible pronunciations.

We do not even know how many tones were present in spoken Tai Ahom, let alone the form of those tones, but the expectation is that, as with the modern spoken Tai languages, the tones may have exhibited a combination of features: (relative) pitch; contour (change of pitch); phonation (plain, breathy and creaky); and duration.40 Furthermore, it is likely that the number and form of those tones changed over time, whereas because they were not marked, the writing remained the same.

Native speakers who read Tai manuscripts of this type do so somewhat differently from the way we read modern English, or the way we read older manuscripts in the European tradition. Consider the English word horse. When this is written in isolation, the meaning is clear to all native English speakers. This is not so with the Ahom word  (also written

(also written  ) /ma/, which can mean “horse” but can also mean “dog”, “to come”, “shoulder” and, in compounds, “fruit”. Which of these meanings is correct in a particular manuscript depends on the context.

) /ma/, which can mean “horse” but can also mean “dog”, “to come”, “shoulder” and, in compounds, “fruit”. Which of these meanings is correct in a particular manuscript depends on the context.

The following examples demonstrate the process of translation. We will discuss this in detail with regard to the manuscript Ming Mvng Lung Phai, what we term in English a “spirit calling” text. The main translators for this text were Chaichuen Khamdaengyodtai, whose expertise is in Shan languages and literature, and myself, with knowledge of comparative Tai and Tai grammar. After the text had been transcribed for the first draft translation in 2007, Chaichuen and I worked for a week with Nabin Shyam Phalung, a speaker of the related Tai Aiton language, thoroughly experienced in reading Tai Aiton texts, and for many years the Head of the Tai section at the Department of Historical and Antiquarian Studies in Guwahati.41 The translation was then revised in 2008, in the Ahom village of Parijat, working together with other members of the research team and also with several members of the Tai Ahom priestly caste, including the manuscript’s owner.

This translation method, while probably the most reliable, was also exceptionally time consuming and expensive, requiring the physical presence of people from different countries in the same location. Subsequent texts have been translated by Chaichuen doing a draft translation into Shan, after which I translate the Shan into English; then Chaichuen and I meet, discuss and revise the translation line by line. The new methodology has the advantage of including a gloss in Shan as well as English, as we will see below in Example 8. Using one or other of these methods, we have completed translations of the following manuscripts: Alika,42 Lakni,43 Ma Likha Lit,44 Ming Mvng Lung Phai, Nemi Mang,45 Pvn Ko Mvng,46 running to approximately 4200 lines. All the translations are searchable online at the Tai and Tibeto Languages of Assam website.47

Returning to the Ming Mvng Lung Phai text, in Tai belief, if the spirit (khon or khwan) of a person, of the paddy rice or of the country, or some other entity, goes away, this causes difficulty. The spirit therefore has to be recalled at a ceremony that includes the reading of an appropriate text. We have never experienced an Ahom spirit calling ceremony, but have witnessed the calling of the spirit of both an ill person and of rice in the Tai Phake and Tai Khamyang communities. In the first case, a young person was ill, which was attributed to the absence of the khon from the ill person; in the second case an individual had a poor harvest, which was attributed to the absence of the khon of the paddy rice. The ceremony, in which sweets and fruit were offered to the spirit, included the reading of the appropriate spirit calling text three times. In the case of the calling of the spirit of the ill person, which was held inside, at the conclusion of the third reading of the text the spirit was felt to have returned, and the doors of the house were shut to keep it in.48

Ming Mvng Lung Phai is one of a number of such texts that we believe were to be read when the whole country is in difficulty. The date of composition of these texts is not known, but, in view of the related texts in the Zhuang speaking areas of China, it is felt that they are very old. The version of the text that we studied is owned by one of the most senior Tai Ahom priests or Deodhai, Chaw Tileshwar Mohan, who has been a great supporter of this research for many years. The project has identified other examples of this text, but his version is by far the most complete and most reliable,49 as Fig. 2.7 below shows.

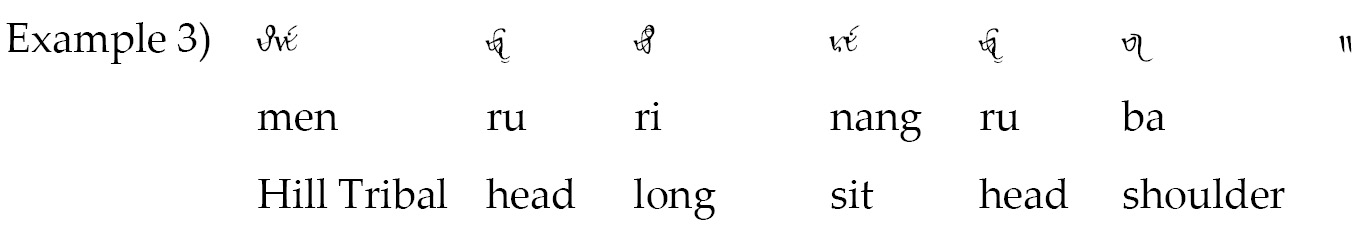

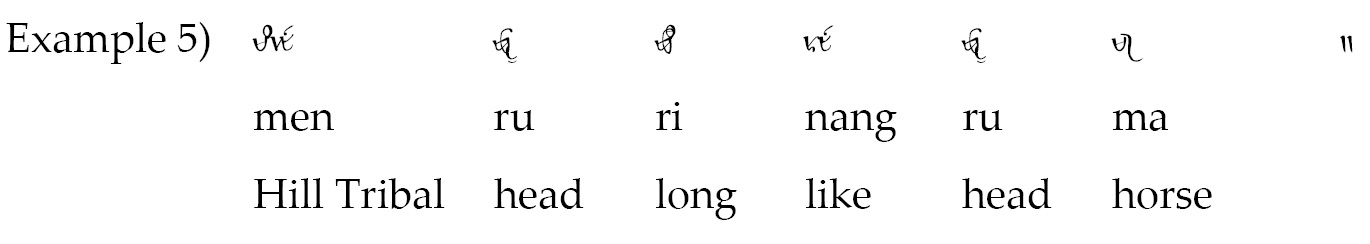

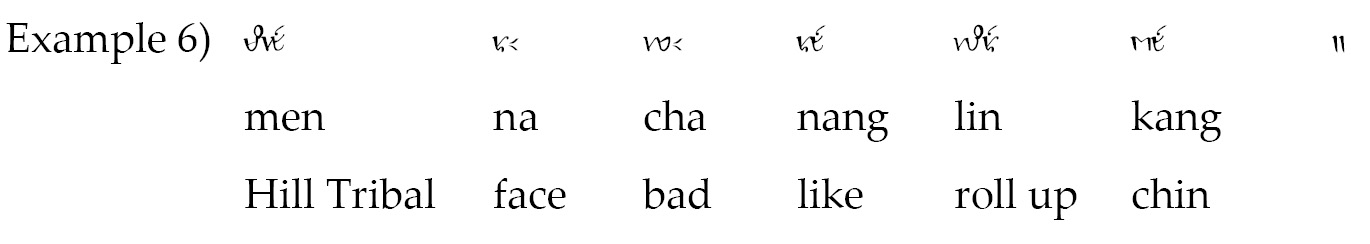

In the section of the text discussed below, the possible locations to which the spirit has gone, and from which it will need to be recalled, are being presented. One example of this is the passage of two lines: men ru ri nang ru ba, men na cha nang lin kang. The poetics of this is clear. The first word is parallel in both lines, as is the fourth word, and in addition there is a “waist rhyme” between the end of the first line, ba, and the third syllable of the second line, cha.

Our first translation of the two lines is given in Examples 3 and 4. Both translations assumed that men was the word for non-Tai tribal people who live in mountainous areas. This is assumed by people in Assam to refer to people living on the border of India and Myanmar, an area mostly populated by Naga people; therefore this word is usually translated as “Naga”. However, if the text had been composed in the original home of the Tai Ahoms, on the Myanmar-China border, this word would refer to a different tribal group,50 so we have glossed it as “Hill Tribal”.

Having decided on this reading for men, the first draft translation assumed that nang was a verb meaning “sit”, which is certainly one of its possible meanings, along with “back”, “extend”, “lady”, “loud”, “be like” and “nose”. Chaichuen then assumed that the phrase ru ba, which in Example 3 follows nang, would be a location, and proposed on the “top of the shoulder”. Syntactically this would have to mean that the long-headed Hill Tribal was sitting there.

“The long headed Hill Tribals sit on the shoulder”.

“The bad faced Hill Tribals sit in the middle of the plain”.

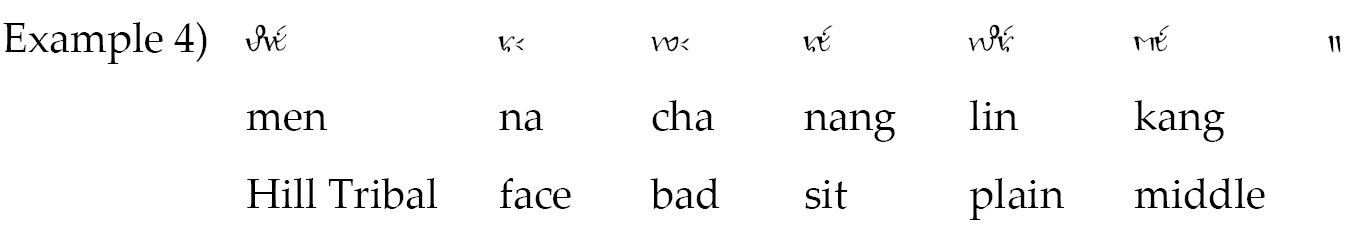

Since these two lines should relate to the location where the spirit was, these translations were plainly not satisfactory. At the time of this work, the research team were staying in Parijat, which is where the manuscript is kept. Chaichuen excitedly came in one morning, having thought about the translation over night, with the suggestion that nang should be read as “like”, and that these two lines were thus similes. With this in mind, we could translate Example 3 as “[The spirit is] with the long headed Hill Tribals whose heads are like dogs”, reading the last word ma as “dog”. This involves reading the first letter of that word, the last in Example 3, as having initial  m rather than initial

m rather than initial  b. In many manuscripts, such as Ming Mvng Lung Phai, these two letters are not distinguished.

b. In many manuscripts, such as Ming Mvng Lung Phai, these two letters are not distinguished.

After listening to Chaichuen’s suggestion, I then suggested that reading ma as “horse” made even more sense — the heads of horses being long — and thus both lines were re-translated as similes describing the Tai Ahom scribes impression of the appearance of the Hill Tribals. Our final translation is given in Examples 5 and 6:

“With the long headed Hill Tribals, whose heads are like horses”.

“With the bad faced Hill Tribals who roll up their chins” (EAP373_TileshwarMohan_MingMvngLungPhai, 6v1).

Fig. 2.7 Folio 6v of the Ming Mvng Lung Phai manuscript

belonging to Tileshwar Mohan (EAP373), CC BY.

The translation process demonstrated here relied on Chaichuen’s substantial lexical knowledge of large numbers of words from Tai varieties still spoken in both Shan State in Myanmar, and in the former Mau Long kingdom, the original home of the Tai Ahom, now inside the Dehong prefecture in Yunnan Province, China. To get the translation to what we see in Examples 5 and 6 requires a deep knowledge of Tai literature that is rapidly becoming extinct, and the ability to read texts in the traditional away. The modernisation of the Shan script since the 1950s, which includes the marking of tone, has made reading a Shan text much more like reading an English text, because the words with different tones are now marked differently.51 The last of the expert readers from the generation brought up before script modernisation are now becoming elderly, and the younger generation, brought up with the reformed script, are reported to have great difficulty reading the traditional texts.

This is the key difference between the challenge of interpreting the Tai Ahom manuscripts and those of interpreting, for example, old English manuscripts, or Latin manuscripts from a period much older than the Ahom texts. Old English and Latin are languages where the script is essentially phonemic, marking most phonemic contrasts. The meaning of a single word is clear, in all but very uncommon cases of homography (such as the modern English bear which could be noun (“type of animal”) or verb (“hold up”) with completely different meaning). In Tai Ahom on the other hand, every written syllable has multiple meanings — in some cases as many as twenty have been recorded — and the texts can only be interpreted in context, and with a very substantial vocabulary at the call of the translator.

One major claim in this paper is that it is of the greatest importance that good quality translations be made of as many of the manuscripts as possible because this is unlikely to be possible to the same extent in the future. Whereas the translation of a Latin or Old English text is likely to be just as possible in 100 years time as it is now, this is not the case with Tai Ahom, because the generation of Chaichuen is the last which has been trained in reading Tai texts in the traditional way, and those are the skills required to interpret these texts correctly.

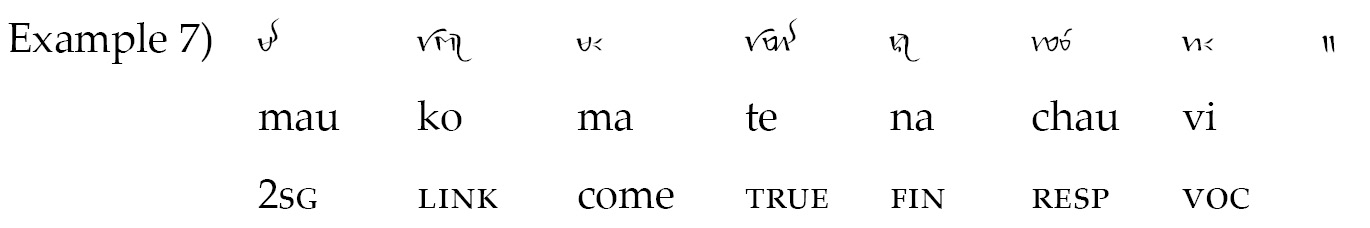

Even making basic metadata on a single manuscript is not something that can be done without considerable effort. We have been fortunate in having Chau Medini Madhab Mohan as a consultant on our project, not only because he has knowledge of the location of large numbers of manuscripts, but also because his experience in studying them has allowed him to identify texts reasonably quickly. This identification is partly done by reading some portion of the texts for meaning, and partly done by comparing stock phrases found often in the texts. So, for example, in the manuscript Ming Mvng Lung Phai, and indeed in all spirit calling texts, there are phrases used for calling the spirit back, which in this manuscript follows the locations where the spirit might be, as in Examples 5 and 6 above. This stock phrase is give as Example 7.

“Come, please come, lord!” (EAP373_TileshwarMohan_Ming MvngLungPhai, 6v1).

The presence of these phrases would be enough to identify the manuscript as a spirit calling text, a group name for which is khon ming (khon “spirit”; ming “tutelary spirit”). Medini Mohan has said that there are three main texts within this genre: Khon Ming Lung Phai (lung “large”); Khon Ming Kang Phai (kang “middle”); and Khon Ming Phai Noi (noi “small”). It has not always been possible to say which of the three a particular text belongs to.

The relationship between contemporary ritual and Tai Ahom manuscripts: The Ai Seng Lau prayer

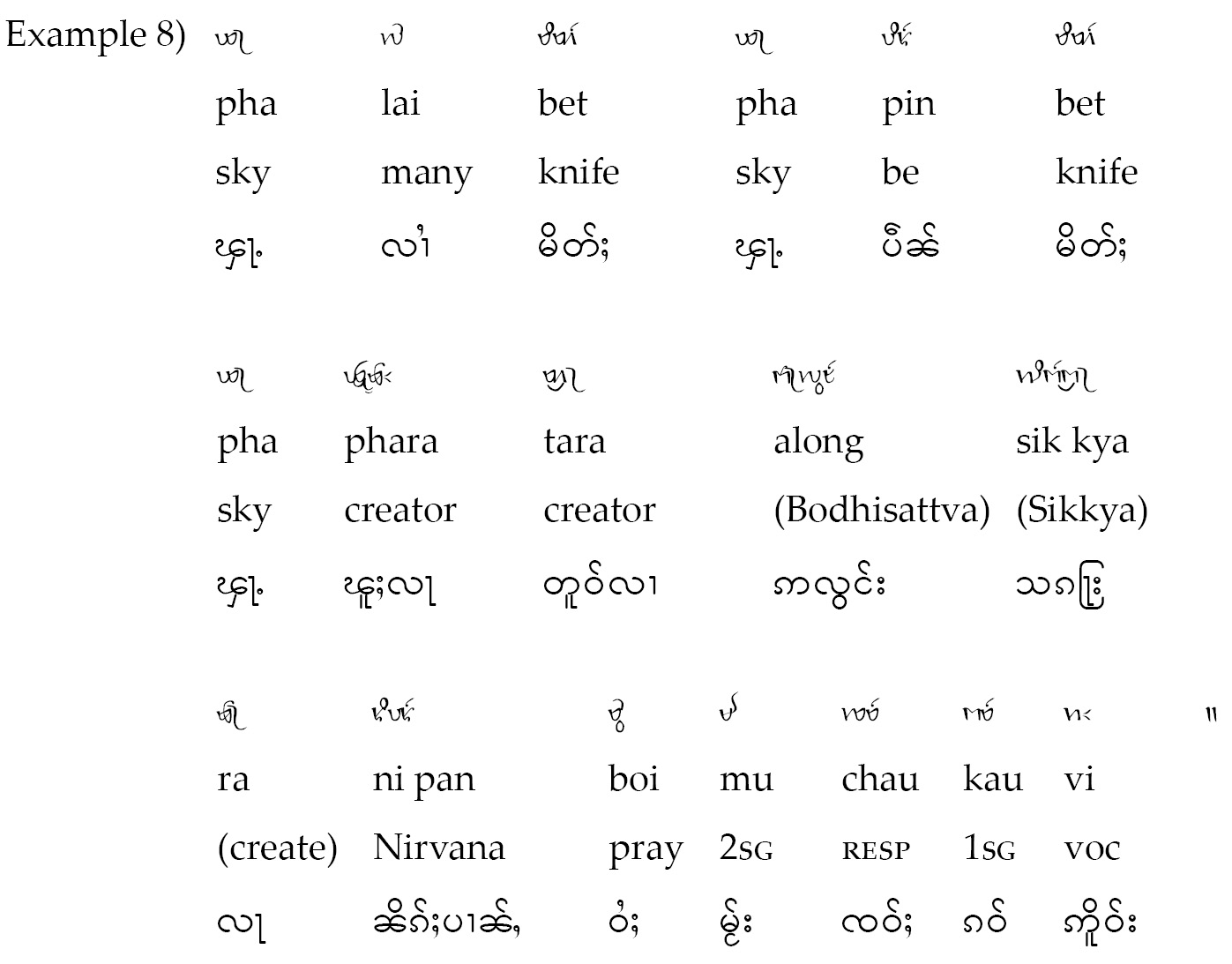

During our photography sessions, the manuscript owners have sometimes asked for a prayer to be performed before the work of photography is commenced.52 This took various forms, sometimes involving the lighting of an oil lamp (probably a Hindu influence) and the offering of money by the project, but also included the recitation of the Ai Seng Lau prayer. Examples of this were recorded in February 2013, in the home of Chau Hara Phukan at Amguri, where we digitised 21 manuscripts;53 and in the home of Chau Kamal Rajkonwar at Lakwa, where we digitised eleven manuscripts.54 The prayer spoken on that occasion was the Ai Seng Lau, led on both occasions by Medini Mohan. The first section of the Ai Seng Lau prayer, as it was uttered, is given below as Example 8.

“The God who is like many knives, the God who is a knife, we pray to you, who are the creator of the sky, the peak of the heaven, oh my Lord”.

There are a number of difficulties in translating this prayer. The first of these is the translation of the word bit, which can also be read as mit. Here we have translated it as “knife”, but there is another Ahom word mit, attested in the Bar Amra lexicon with the meaning “rainbow”. If we take this as the meaning of mit, we would read lai mit as “pattern of the rainbow”, which is a plausible meaning here.

Example 8 is part of a longer prayer that is frequently used in Tai Ahom rituals. While we have not found this exact phrase in a manuscript, we have found references to a similar passage in manuscripts such as the Sai Kai text for which there are several versions. The one shown below (Fig. 2.8) belongs to Chau Padma Sangbun Phukan of Amguri, but we have also consulted two additional copies belonging to Tileshwar Mohan,55 the owner of the Ming Mvng Lung Phai manuscript. None of these manuscripts have the dates of copying, or information about the copyist. None of them is complete, but careful comparison of the three versions means that the text is in the process of being reconstructed. The first line of this text is presented in Example 9. This example confirms the reading of “knife”, in a metaphorical sense, as the one who is carving out the earth, because there cannot have been a rainbow at the time when the creation of the sky had not yet happened.

“Long ago when the God who is a knife was beginning to create the ground, and before the sky was created” (EAP373_PadmaSangBunPhukan_SaiKai1_0004).

Fig. 2.8 Folio 1r of a Sai Kai manuscript

belonging to Padma Sangbun Phukan (EAP373), CC BY.

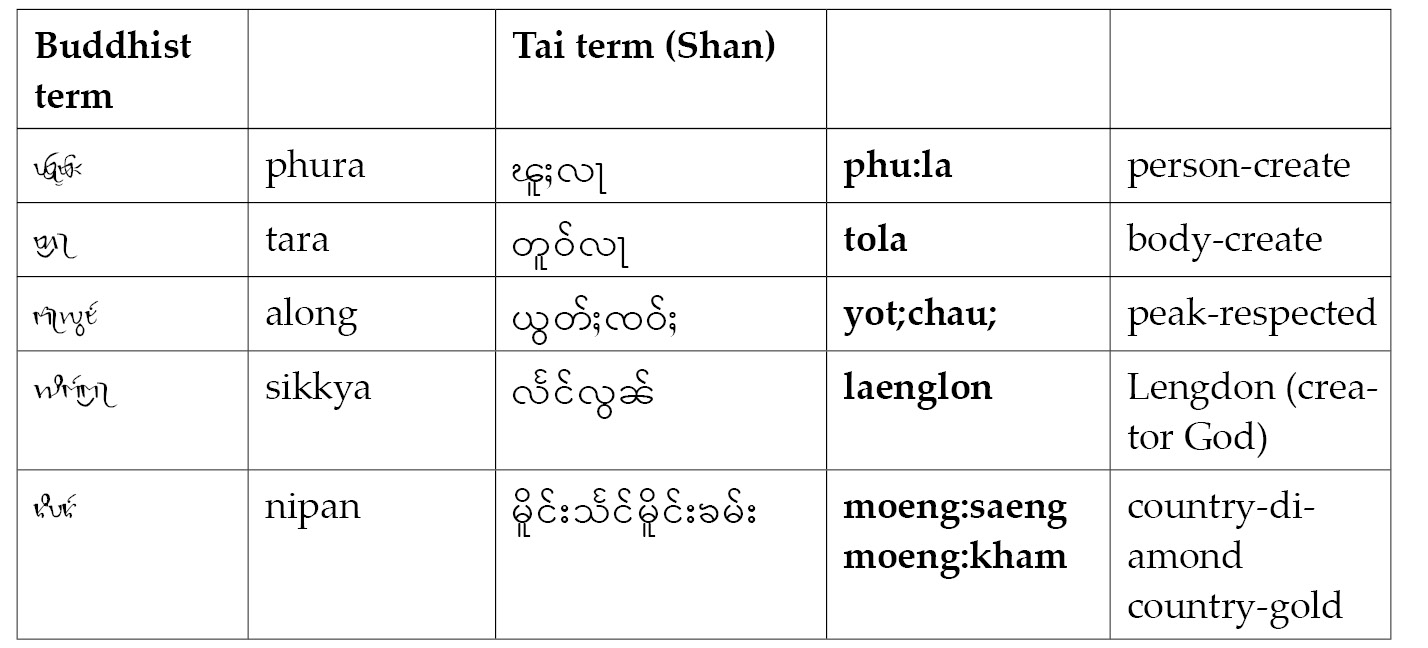

Returning to Example 8, the second line contains a number of Buddhist terms: phura (Buddha), tara (teaching of the Buddha or dharma), along (Bodhisattva, previous incarnation of the Buddha), sikkya (Sakya, creator God in the Buddhist texts) and nipan (Nirvana, the state of enlightenment). The presence of these terms in the prayer suggests Buddhist influence on the Tai Ahom rituals. Chaichuen has suggested that these words can be interpreted as replacing original Tai expressions, as we see in Table 2.1:

Table 2.1 Buddhist terms in the Ai Seng Lau prayer and Tai equivalents

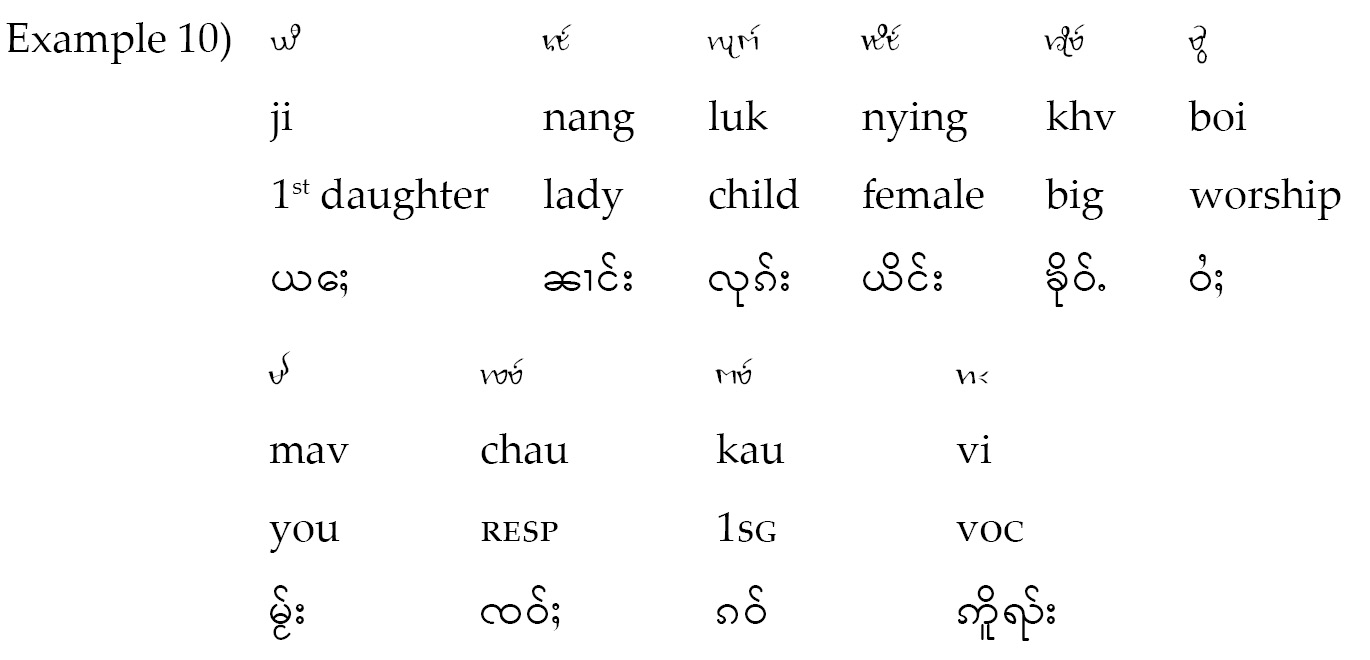

A few lines later in the Ai Seng Lau prayer, we see the following, in which a deity or entity called ji (first daughter) is invoked, as seen in Example 10:

“We pray to you, the first great daughter, oh my Lord”.

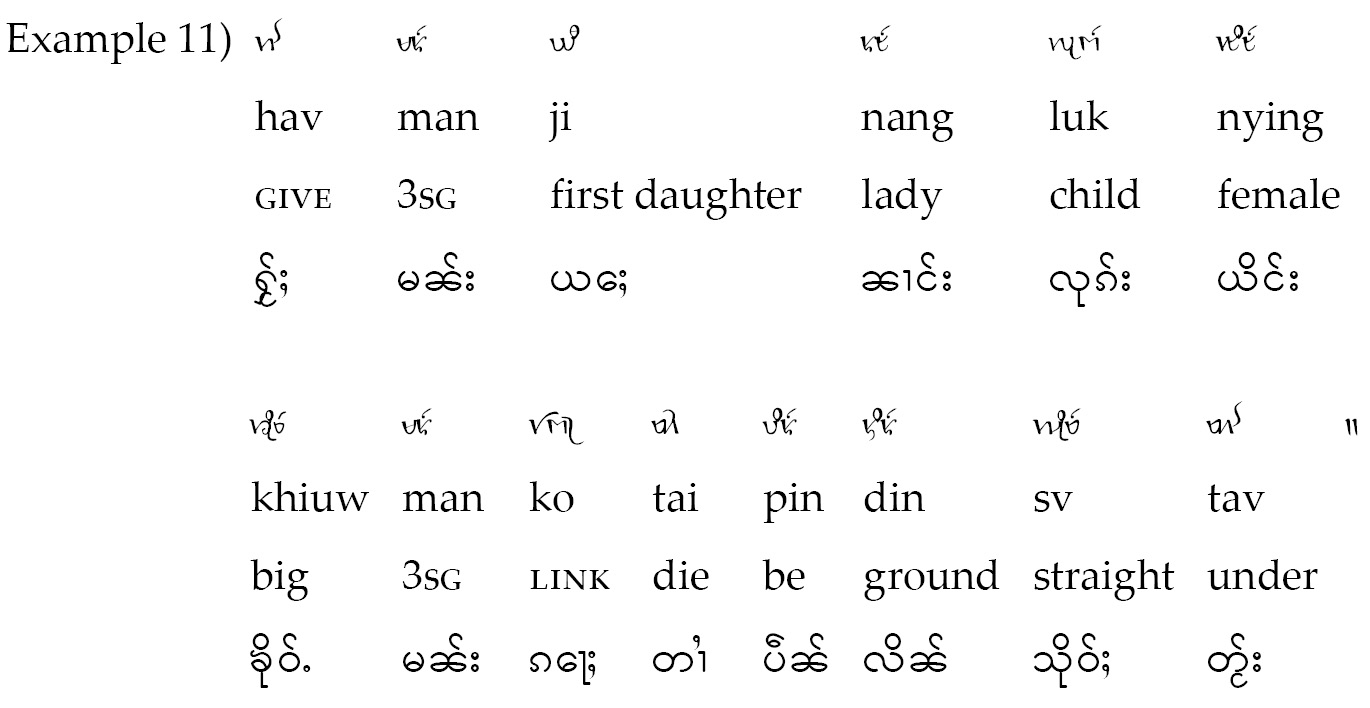

The same entity is found in the Sai Kai manuscript in the line that immediately follows Example 9, presented here as Example 11:

“He made the first daughter, the big one, after she died she became the ground directly under” (EAP373_ PadmaSangBunPhukan_SaiKai1_0004).

Both the Ai Seng Lau prayer and the Sai Kai manuscript have the same phrase to refer to this deity, ji nang luk nying khiuw (the first daughter, the big one). In the Sai Kai manuscript, it goes on after Example 11 to refer to the three younger sisters of ji, namely i (second daughter), am (third daughter) and ai (fourth daughter). These four words occurring in the same position in four successive lines confirm for us the reading that we have given in Example 11.

This brief discussion of Ahom prayers has been presented to show the relationship between these manuscripts and the living tradition of Ahom prayers. The similarity between the Ai Seng Lau prayer and the Sai Kai manuscripts confirms that the language of those prayers is not the “Pseudo Ahom language” that Terwiel has suggested was in use for some Ahom rituals.56 It remains possible that the prayers such as Ai Seng Lau have been newly created after studying the manuscripts, although members of the Tai Ahom priestly caste specifically say that this prayer has been handed down from father to son over many generations, though without knowing the full meaning of the prayer. What we can say is that the close study of the manuscripts has allowed for a translation of the prayers that are in use in contemporary ritual to be undertaken.

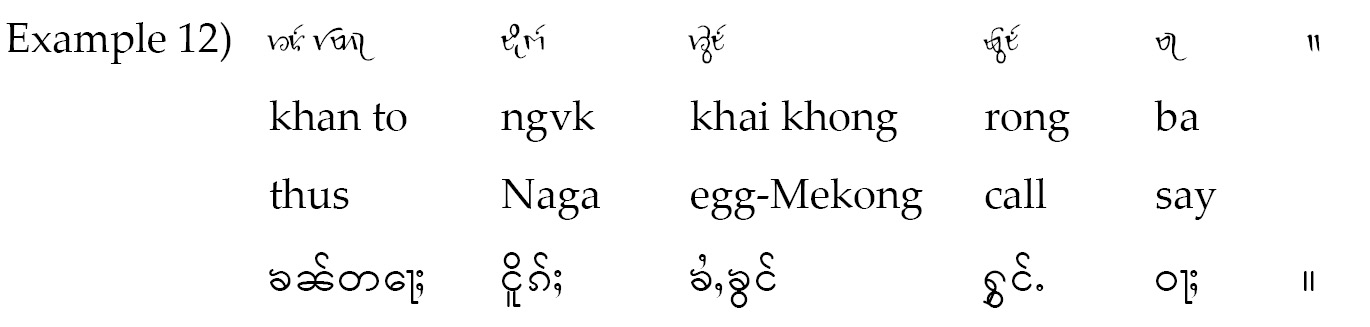

Stories

In addition to the Buddhist stories mentioned earlier, there are a number of Tai stories whose storyline is not necessarily known from other sources and whose translation is thus more challenging. One example of these is the Nang Khai story, from a manuscript owned by the late Baparam Hati Baruah of Hati Gaon (Fig. 2.9).57 The manuscript, one of the first photographed in the project, has the name of the copyist, and the name of the text, but no date. On fol 20v (image 0042) it is written: “In the seventh month, his father who was Serela Baruah and his son Mekheli, he wrote this Nang Khai scripture which should not be allowed to disappear, should not be hidden [lest] you fall into the forks of hell”. The name of the manuscript is given as  [Nang Khai Puthi], where puthi is an Assamese word meaning “sacred text”. Altogether there are 37 folios in this text, and so it is curious that the scribe gave his name only a little over half way through. Although we have not yet finished translating the whole text, it does appear to be one story; perhaps in writing his name in the middle of the text, the copyist was confused about the contents.

[Nang Khai Puthi], where puthi is an Assamese word meaning “sacred text”. Altogether there are 37 folios in this text, and so it is curious that the scribe gave his name only a little over half way through. Although we have not yet finished translating the whole text, it does appear to be one story; perhaps in writing his name in the middle of the text, the copyist was confused about the contents.

Fig. 2.9 Folio 20v of the Nang Khai manuscript

belonging to Baparam Hati Baruah (EAP373), CC BY.

Since the translation of the manuscript is not yet complete,58 we do not yet know the meaning of “nang khai”. It could be “lady egg”, referring to a lady who is related to the king, one term for whom is khai pha (“the egg of the sky”). So while we know the name of this manuscript because it is explicitly stated, we will not know what that means until the whole text has been studied. The story of this manuscript is about a river creature, or Naga, and a man, referred to as “the single man”, who casts his fishing net over the river and accidentally catches that Naga.59

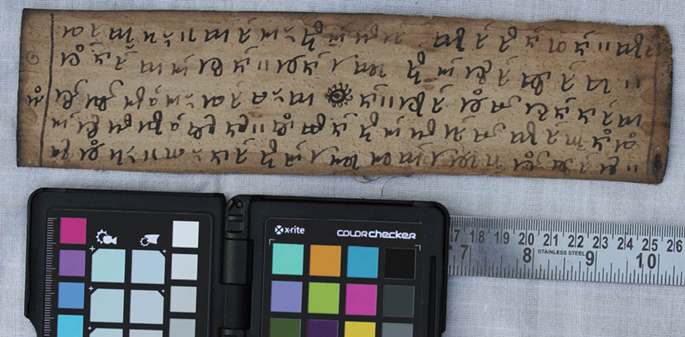

This text gives some clues as to its place of origin. If our translation is correct, it refers to the Mekong River, as we see in Example 12, reproduced in Fig. 2.10.

“Thus the Naga who was the egg of Mekong called out, saying” (EAP373_BaparamHatiBaruah_NangKhai_0008).

Fig. 2.10 Folio 3v of the Nang Khai manuscript

belonging to Baparam Hati Baruah (EAP373), CC BY.

Chaichuen observed that this text, which he has never heard of in Shan areas, refers to the history of Tai people in the Mekong river area, and consequently must have been brought to Assam rather than composed there. In his view, this would have to have been done before the destruction of the kingdoms of Muang Mau Lung, Muang Kong and Muang Yang in the year 1555. This campaign was led by the Burmese King Bayinnaung of Toungoo (1550-1581). Thus our assumption is that the manuscript must have been composed before 1555 and that it may not survive in Mau Lung. Chaichuen said that this story could not have been brought later, because all of the old manuscripts were burned during the wars waged by King Bayinnaung. So far this is the only text we have analysed that can definitely be associated with the Mau Lung area, but we expect there are more among the manuscripts that have been photographed.

Scholarly outcomes

The major scholarly outcomes of EAP373 are: the transcription and translation of a number manuscripts; the further development of the online Tao Ahom Dictionary; the preparation of a descriptive grammar of Tai Ahom; and the realization of the proposal to include Tai Ahom script in the Unicode.

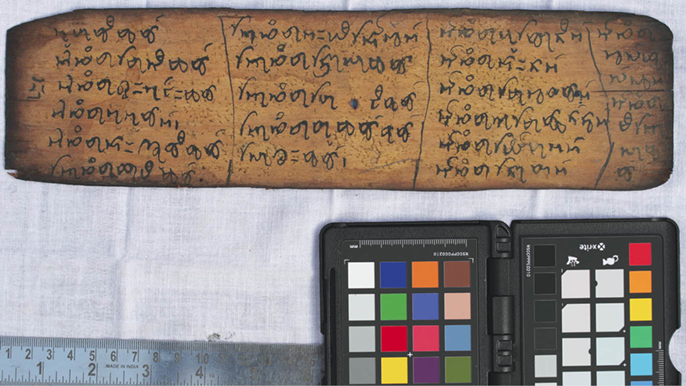

As we have seen, the process of transcribing and translating texts is very time consuming, but they form the basis for the continued development of the online Ahom Dictionary.60 At present the dictionary contains over 4,500 head words and many subentries for multiple senses of a word and for compounds. Each word listed in the dictionary is sourced to an Ahom manuscript, in many cases the Bar Amra, a Tai-Ahom to Assamese lexicon. There are a number of copies of the Bar Amra, of which the most important is kept at the Department of Historical and Antiquarian Studies in Guwahati. The version that we were able to consult is that owned by Junaram Sangbun Phukan, one of the most senior Ahom priests (Deodhai) from Parijat village. The manuscript, written completely in Ahom script, gives a word in Tai and then a translation in Assamese. An example is given below (Fig. 2.11).

Fig. 2.11 Folio 1v of the Bar Amra manuscript

belonging to Junaram Sangbun Phukan (EAP373), CC BY.

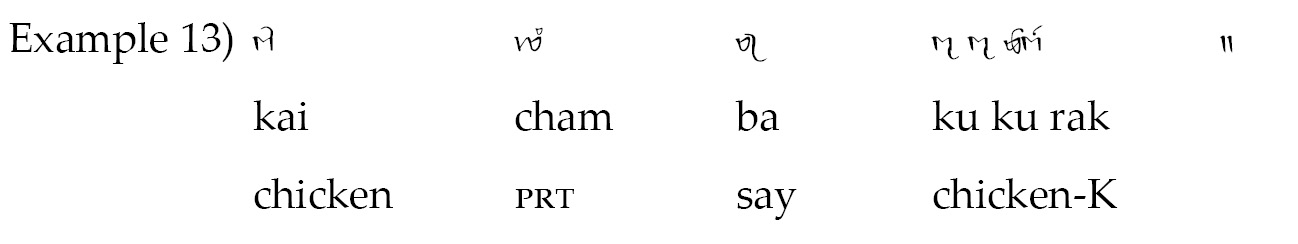

This page, folio 1v, is divided into three columns. The Assamese meanings of the word  kai are given on the left hand side (lines 1-6). The fifth line is the word for “chicken” which reads as in Example 13, with the Assamese translation written in Ahom script and marked by the case marker -ɔk, which marks some direct and indirect objects.

kai are given on the left hand side (lines 1-6). The fifth line is the word for “chicken” which reads as in Example 13, with the Assamese translation written in Ahom script and marked by the case marker -ɔk, which marks some direct and indirect objects.

“For a fowl, kai is said”.

The entire manuscript was transcribed by Zeenat Tabassum,61 and formed the basis for a dictionary in the Toolbox format.62 All words that occur in the Bar Amra are included, but in addition words that we find in other manuscripts are added when their meanings are confirmed. Each of those words is sourced back to at least one example in the manuscripts. The online dictionary includes the sentence containing an example of the word, in Ahom script, transliteration, with English, Shan and sometimes Assamese translations.63 All the manuscripts referenced in the dictionary are also in the EAP archive.

The writing of a descriptive Ahom grammar, based on the language examples as found in the manuscripts, whose translation is possible because of their identification through this project. A sketch grammar, running to around 34 pages has been already published: it is available in a published article, and has been archived online as part of the DoBeS website.64

Finally, there is the development of a Unicode encoding for the Ahom script, which has been jointly developed by Martin Hosken and myself.65 The final version of the Ahom Unicode proposal was presented to the Unicode consortium in October 2012 and approved. A first draft Tai Ahom unicode font has been produced, together with a keyboard, and since July 2014 the font has been in use by community members on Facebook and in some email formats. There are some remaining technical issues to ensure that the font renders correctly in word-processing programs like Microsoft Word or Open Office.66 Nevertheless the fact that the Tai Ahom language can now be used on social media has the potential to lead to a great expansion in the use of this script and further strengthen the revival of the language.

Coda: a manuscript’s injunctions

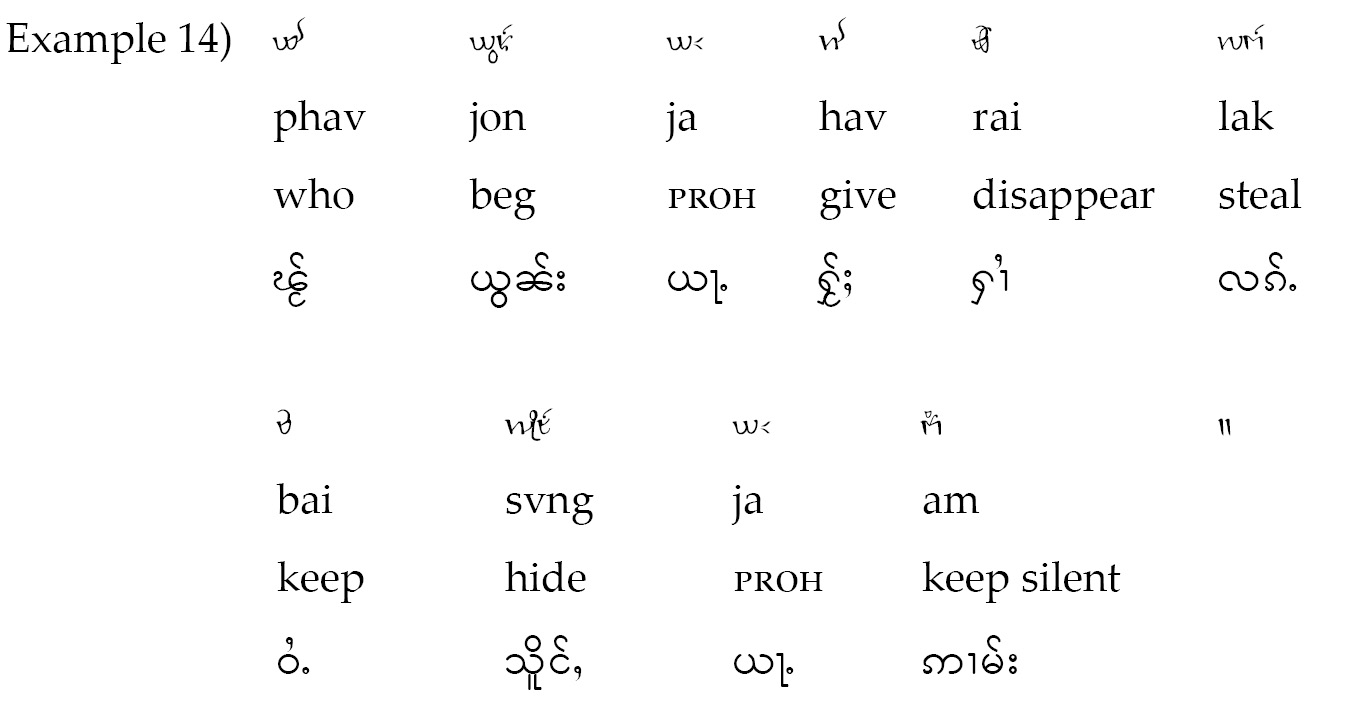

Sometimes at the end of a manuscript, following the section containing the name of the copyist and the date of the copying, there is an injunction from the copyist about what should happen to the text. Example 14 is a line of text from the end of the Khun Lung Khun Lai manuscript belonging to Tulsi Phukan (see Fig. 2.4).

“If someone begs [to take it] don’t give it lest it disappear, keep it hidden, but don’t keep silent [about the story]”.

This translation was done by Chaichuen and myself, and the meaning emerged after some discussion. The grammatical structure of this line is: phav jon, ja hv rai lak, bai svng, ja am. The sentence consists of a condition (phav jon “[if] someone begs [it]”), followed by three commands: ja hav rai lak (“don’t let it be lost and taken away”), bai svng (“keep it hidden” or perhaps “keep it safe”), and ja am (“don’t keep silent about it”). This we interpret as a request to the future owners of the book to keep it in its proper location, not to let it be taken away, keep it safe, but not to hide its contents and meaning from the wider community. I consider that our work is exactly in accord with this injunction.

Abbreviations

|

fin |

final particle |

|

give |

grammaticalisation of the word “give” to imply causation, or allowing something to happen |

|

link |

linking word, sometimes translatable as “also” |

|

n.fin |

non-final, a particle indicating that another phrase or clauses is to follow |

|

pl |

plural |

|

pn |

proper name |

|

proh |

prohibitive, “don’t do X” |

|

resp |

respect particle |

|

sg |

singular |

|

true |

literally “true”; this particle is largely bleached of meaning but conveys that the statement is believed to be true |

|

voc |

vocative |

References

Barua, Bimala Kanta, and N. N. Deodhari Phukan, Ahom Lexicons, Based on Original Tai Manuscripts (Guwahati: Department of Historical and Antiquarian Studies, 1964).

Barua, Golap Chandra, Ahom Buranji: From the Earliest Time to the End of Ahom Rule (Guwahati: Spectrum, 1985 [1930]).

Egerod, Søren, “Essentials of Shan Phonology and Script”, Academia Sinica: Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology, 29 (1957), 121-27.

Gait, Edward, A History of Assam (Guwahati: Lawyers Book Stall, 1992 [1905]).

Gogoi, Lila, The Buranjis, Historical Literature of Assam: A Critical Survey (New Delhi: Omsons, 1986).

Holm, David, Recalling Lost Souls: The Baeu Rodo Scriptures, Tai Cosmogonic Texts from Guangxi in Southern China (Bangkok: White Lotus, 2004).

Li Fang-Kuei, A Handbook of Comparative Tai (Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press, 1977).

Mitra, Anup, Coins of the Ahom Kingdom (Calcutta: Mahua Mitra, 2001).

Morey, Stephen, The Tai Languages of Assam: A Grammar and Texts (Canberra: Pacific Linguistics, 2005).

—, “A Sketch of Tai Ahom”, in Axamiya aru Axamar Bhasa [Assamese and the Languages of Assam], ed. by Biswajit Das and Phukan Basumatary (Guwahati: AANK-Bank, 2011).

—, “Ahom and Tangsa: Case Studies of Language Maintenance and Loss in North East India”, Language Documentation and Conservation, 7 (2014), 46-77.

—, “Studying Tones in North East India: Tai, Singpho and Tangsa”, Language Documentation and Conservation, 8 (2014), 637-71.

Nathan, David, and Peter K. Austin, “Reconceiving Metadata: Language Documentation Through Thick and Thin”, Language Documentation and Description, 2 (2004), 179-88.

Sai Kam Mong, The History and Development of the Shan Scripts (Chiang Mai: Silkworm, 2004).

Sao Tern Moeng, Shan-English Dictionary (Kensington, MD: Dunwoody Press, 1995).

Terwiel, B. J., The Tai of Assam and Ancient Tai Ritual, Volume I: Life Style Ceremonies (Gaya: Centre for South East Asian Studies, 1980).

—, The Tai of Assam and Ancient Tai Ritual, Volume II: Sacrifices and Time-reckoning (Gaya: Centre for South East Asian Studies, 1981).

—, “Reading a Dead Language: Tai Ahom and the Dictionaries”, in Prosodic Analysis and Asian Linguistics: To Honour R. K. Spriggs, ed. by David Bradley, Eugénie J. A. Henderson and Martine Mazaudon (Canberra: Australian National University, 1989), pp. 283-96.

—, “Recreating the Past: Revivalism in Northeastern India”, Bijdragen: Journal of the Royal Institute of Linguistics and Anthropology, 152 (1996), 275-92.

—, and Ranoo Wichasin, eds. and trans, Tai Ahoms and The Stars: Three Ritual Texts to Ward off Danger (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1992).

Wichasin, Ranoo, trans., Ahom Buranji (Bangkok: Amarin, 1996).

1 Since 2007, this work on Ahom was funded first by the DoBeS Documentation of Endangered Languages project, financed by the Volkswagen Stiftung, based at the Max Planck Institute in Nijmegen, and later by the Australian Research Council under the Future Fellowship Scheme. The project EAP373: Documenting, conserving and archiving the Tai Ahom manuscripts of Assam (http://eap.bl.uk/database/overview_project.a4d?projID=EAP373), which is on-going, has been funded by the Endangered Archives Programme, whose support for my work is much appreciated. I am very grateful to members of the research team, particularly Ajahn Chaichuen Khamdaengyodtai whose work on Ahom manuscripts has provided so much enlightenment. The main task of photography and metadata collection has been undertaken by Poppy Gogoi and Medini Madhab Mohan, whose expertise in locating and identifying manuscripts has been invaluable. In the early stages of this project Zeenat Tabassum, Karabi Mazumder, Iftiqar Rahman, Jürgen Schöpf and Palash Nath all gave great assistance. The leading Ahom pandits, Tileshwar Mohan and Junaram Sangbun Phukon, in particular have given enormous help over the years. The support of the Centre for Research in Computational Linguistics at the University of Maryland, and its director Doug Cooper has been very beneficial for a long time. I am very grateful also to the editors of this volume, particularly Maja Kominko and the anonymous reviewers for many helpful comments, and to Bianca Gualandi for her work on images. Finally, I want to thank all the manuscript owners, the Institute of Tai Studies and Research, and its director Girin Phukan; Bhim Kanta Baruah, David Holm, B. J. Terwiel, Wilaiwan Khanittanan, Ranoo Wichasin, Thananan Trongdi, Anthony Jukes, Pittayawat Pittayporn and Atul Borgohain, the last being my mentor and supporter in Ahom studies for many years.

4 As these translations are made ready, they will be published in searchable form on the Tai and Tibeto-Burman languages of Assam website (http://sealang.net/assam).

6 Kamol Rajkonwar, who lives on the banks of the Disangpani River at Lakwa, was particularly keen to get his manuscripts photographed and delighted that the work was being undertaken. When we arrived at his house, he surprised me by producing a copy of my 2002 doctoral thesis on the Tai languages of Assam. Disangpani is an example of a name with elements from possibly three different languages. Di is a word for the Boro or Dimasa language, the language of the pre-Ahom inhabitants of the area, meaning “water”. Most of the rivers in the Ahom area have names with Di- as a prefix. The meaning of sang is not known but could be Tai Ahom, and pani is Assamese for “water”. The place where Rajkonwar lives is near a large outdoor area sacred to the Tai Ahoms, containing altars to some of the deities mentioned in some manuscripts. The exact function of this sacred area is not known and, as far as I know, it has not been investigated in a scholarly manner.

7 Iftiqar Rahman is a Master’s graduate in linguistics who assisted Poppy Gogoi with photography on several occasions.

8 Edward Gait, A History of Assam (Guwahati: Lawyers Book Stall, 1992 [1905]); and Golap Chandra Barua, Ahom Buranji: From the Earliest Time to the End of Ahom Rule (Guwahati: Spectrum, 1985 [1930]).

9 Li Fang-Kuei, A Handbook of Comparative Tai (Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press, 1977). The other two main divisions of Tai, according to Li, are Central and Northern, and both of these are to be found in China — in Yunnan, Sichuan and particularly Guangxi provinces — as well as northern Vietnam. Speakers of Central and Northern Tai varieties are not generally Buddhist. The modern location of the Tai Ahom is in fact north of most of these areas, but that is due to migration since the thirteenth century.

10 A large proportion of Tai people in Vietnam and some in Laos practice what has been described as “traditional religion”. For example, the White Tai (Tai Dón) are said to be mostly animist.

11 Linguistically Zhuang is very diverse, and languages subsumed under this name fall into both Central Tai and Northern Tai.

12 B. J. Terwiel, “Recreating the Past: Revivalism in Northeastern India”, Bijdragen: Journal of the Royal Institute of Linguistics and Anthropology, 152 (1996), 275-92; and Stephen Morey, “Ahom and Tangsa: Case Studies of Language Maintenance and Loss in North East India”, Language Documentation and Conservation, 7 (2014), 46-77.

13 Terwiel, “Recreating the Past”, p. 286.

14 Mustard oil was found to be the best available substance to clean off generations of dirt in order to be able to read the text. Often the first page of the manuscript was the one that was most exposed to the elements and was virtually unreadable. This, not surprisingly, made the identification of manuscripts even more difficult.

15 Usually it was necessary to photograph the silk manuscript both in full and in parts — generally each of the four corners — in order to have a detailed enough photograph of it. In the case of this manuscript, we decided to hold it up against the wall of the owner’s house for photographing.

16 We cannot be sure that the tradition of manuscript copying was continuous throughout the nineteenth century, although members of the Tai Ahom priestly caste assured us many times that they were. We can say with confidence, based on dates found in the manuscripts, and information about the copyists, that there has been a continuous tradition of copying texts since at least the late nineteenth century. For example, in some cases the copyist was identified as the great-grandfather of the present owner, and, in combination with the Lakni date, we could establish that the book was copied in the last third of the nineteenth century.

17 The inscriptions on the coins are usually in Sanskrit or Persian, but a very small number have inscriptions in the Ahom script. The coins are comprehensively listed in Anup Mitra, Coins of the Ahom Kingdom (Calcutta: Mahua Mitra, 2001). Mitra lists a coin of King Pramataa Simha (Sunenpha) (1744-1751) as an example of a coin with a Tai Ahom inscription (p. 76,).

18 For an illustration of the pillar, see Raju Mimi, Arunachal Times, 6 February 2011, http://www.roingcorrespondent.in/the-sadiya-snake-pillar-mishmi-ahom-friendship

19 For an explanation of the Lakni system and a comparison with other calendars in Southeast Asia, see B. J. Terwiel, The Tai of Assam and Ancient Tai Ritual, Volume II: Sacrifices and Time-reckoning (Gaya: Centre for South East Asian Studies, 1981).

20 Taking the accession of King Siuhummiung in the year Rung Bau as equivalent to 1497, the year 1805 corresponds to Kat Kau.

21 This manuscript will be archived as EAP373_PadmaSangBunPhukan_SaiKai_0001 to 0058.tif.

22 This is an Assamese term, of possible Tai origin, referring to histories.

23 Tai Ahoms and the Stars: Three Ritual Texts to Ward off Danger, ed. and trans. by B. J. Terwiel and Ranoo Wichasin (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1992). This is an excellent and well-notated translation.

24 These are Assamese terms for two lexicons composed in the late eighteenth century at the time when the Ahom language was in decline as a mother tongue. Both are written in Ahom script. The Bar Amra is a Tai Ahom-Assamese lexicon, mostly of monosyllabic words, presented in the Ahom alphabetical order with Assamese words transcribed in Ahom script. The Loti Amra is arranged in semantic fields commencing with body parts and contains mostly multisyllabic expressions. Also written entirely in Ahom script, the Loti Amra puts Assamese words first then Tai words second. These two lexicons formed the basis of our online dictionary (http://sealang.net/ahom).

25 Once the project is completed, and all the texts identified, it will be possible to quantify these claims. The texts in category (e), Phe Lung Phe Ban, Du Kai Seng, and Ban Seng, are all very easy to identify, but some of the other categories are not.

26 Golap Chandra Barua, Ahom Buranji: From the Earliest Time to the End of Ahom Rule (Guwahati: Spectrum, 1985 [1930]).

27 Ranoo Wichasin, trans., Ahom Buranji (Bangkok: Amarin, 1996).

28 We will present examples here in four lines: (1) Ahom script, (2) suggested phonemic reading, (3) English gloss, and (4) free translation into English.

We use the symbol <v> to mark an unrounded back vowel /ɯ/ or /ɤ/ in IPA script. Some Tai languages like Phake have a distinction between these two sounds, but there is reason to believe that in Ahom this distinction had been lost by the end of the Ahom Kingdom. This is discussed in Stephen Morey, The Tai Languages of Assam: A Grammar and Texts (Canberra: Pacific Linguistics, 2005), p. 176. We write <ⱱ> to encourage the members of the Ahom community not to pronounce it as /u/ or /e/, a practice that can be seen in Barua’s translation, where the same vowel is present in all three syllables of the king’s name, written as /u/ in the first and third syllables, with the second syllable being read as having an /e/ vowel with an initial consonant cluster.

29 The text in Pali is named Nimi Jataka and is no. 541 in the series of Jataka (previous lives of the Buddha). This is a very famous story, illustrated, for example, in murals in temples in Thailand, http://www.buddha-images.com/nimi-jataka.asp. An English translation is The Jataka, Volume VII, trans. by E. B. Cowell and W. H. D. Rouse (1907), http://www.sacred-texts.com/bud/j6/j6007.htm

30 Archived as EAP373_GileshwarBailung_NemiMang.

31 The naming of both manuscripts is on folio 66r, line 3. It was necessary to read a fair amount of the text in order to find this.

32 Translations of these two texts are searchable online at the Tai and Tibeto-Burman Languages of Assam website, http://sealang.net/assam

33 There are a number of Assamese Buranjis. For a discussion of them, see Lila Gogoi, The Buranjis, Historical Literature of Assam: A Critical Survey (New Delhi: Omsons Publications, 1986).

34 All the Buddhist canonical texts were published in Romanised script by the Pali Text Society, along with translations. Some of the translations are available online at http://www.palicanon.org, and the Pali texts are available to be searched at http://www.tipitaka.org

35 There are different linguistic theoretical frameworks for the presentation of the elements within a syllable. In one theoretical framework, all vowel initial words are actually preceded by a glottal stop [ʔ], and this is represented in writing by  in the Ahom script. In our analysis, the glottal stop is not a phoneme of Tai Ahom, and vowel initial syllables are permitted. For further discussion, see Morey, The Tai Languages of Assam, p. 111.

in the Ahom script. In our analysis, the glottal stop is not a phoneme of Tai Ahom, and vowel initial syllables are permitted. For further discussion, see Morey, The Tai Languages of Assam, p. 111.

36 This is the word given to a sign indicating that a consonant has no following vowel. Consonants without it can be interpreted as being followed by /a/. It is called sāt in Tai Phake.

37 Morey, The Tai Languages of Assam, ch. 7.

38 We use a digraph <ng> rather than the IPA symbol /ŋ/ to mark the velar nasal. This is because we are using only Roman letters to transcribe the Ahom script in our work, to make it easier for the members of the Ahom community to interpret the linguistic materials.

39 For a discussion of the writing of vowels in the Tai Phake script, and how the script under specifies the vowel contrasts, see Morey, The Tai Languages of Assam, pp. 190-94.

40 Stephen Morey, “Studying Tones in North East India: Tai, Singpho and Tangsa”, Language Documentation and Conservation, 8 (2014), 637-71.

41 Nabin’s skills as both a native speaker of a closely related Tai language and his decades of experience working with Tai Ahom manuscripts were not enough to allow him to undertake the task of translating this text alone.

42 This text, containing what we believe is probably a Buddhist story, forms the first two thirds of EAP373_GileshwarBailung_Nemimang_0001 to 0139.tif.

43 This text was translated from a photocopy. The location of the original of this manuscript is not known.

44 This text, containing what we believe is probably a Buddhist story, has yet to be photographed for the project.

45 This text, a Buddhist story, forms the last third of EAP373_GileshwarBailung_Nemimang_0001 to 0139.tif.

46 This text, which tells the story of the creation of the world, is archived as EAP373_TileshwarMohan_PvnKoMvng_0001 to 0038.

47 This website (http://sealang.net/assam) is updated from time to time and additional texts will be added as the translations are completed. The next one to be completed will be the Nang Khai manuscript owned by the late Baparam Hatibaruah, the photographs of which will be archived as EAP373_BaparamHatiBaruah_NangKhai_0001.tif to 0078.tif.

48 For a more detailed discussion of spirit calling among the Ahom, see B. J. Terwiel, The Tai of Assam and Ancient Tai Ritual, Volume I: Life Style Ceremonies (Gaya: Centre for South East Asian Studies, 1980), p. 53. For the practice among the Zhuang in China, see David Holm, Recalling Lost Souls: The Baeu Rodo Scriptures, Tai Cosmogonic Texts from Guangxi in Southern China (Bangkok: White Lotus, 2004).

49 Unfortunately the first folio was damaged by insects between 2007, when I first photographed it in JPG format, and 2012, when the EAP-funded project was able to take raw format files and convert them to TIF format for archiving.

50 In Assam the word men is mostly associated with the people now called Naga, but in Shan State the cognate word refers to the “ethnic group inhabiting the mountains of Muang Ting”. Sao Tern Moeng, Shan-English Dictionary (Kensington, MD: Dunwoody Press, 1995). The phrases “head like horses” and “roll up their chins” might refer to people who wear long-necked decorations, such as the Kayan people in Shan state, i.e. in the mountain areas on the China-Myanmar border. Photographs of women wearing these decorations can be found on the Wikipedia page “Kayan people (Burma)”, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kayan_people_%28Burma%29. Equally these might be ways of referring to the headdresses of the Naga people on the India-Myanmar border.

51 See Søren Egerod, “Essentials of Shan Phonology and Script”, Academia Sinica: Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology, 29 (1957), 121-27. For further details of Shan script and script reform, see Sai Kam Mong, The History and Development of the Shan Scripts (Chiang Mai: Silkworm, 2004).

52 We hope that eventually the videos of these short ceremonies can be archived together with the photographs of the manuscripts.

53 We will not list these here, but the digitised files will have the prefix EAP373_HaraPhukan_.

54 These will be archived with the prefix EAP373_KamolRajkonwar_.

55 These will be archived as EAP373_TileshwarMohan_SaiKai_0001 to 0032.tif and EAP373_TileshwarMohan_SaiKai__02_0001 to 0038.jpg.

56 Terwiel, “Recreating the Past”, p. 283.

57 Baparam Hati Baruah passed away in 2014 before the translation of his manuscript could be completed and presented to him. His house was one of very few Ahom houses that maintained the Tai tradition of building on stilts, but with the special feature that the bamboo floors on the upper level were rendered with mud. This manuscript is archived as EAP373_BaparamHatiBaruah_NangKhai_0001 to 0078.tif.

58 We hope this will be completed in early 2015.

59 There is another manuscript, EAP373_SandicharanPhukan_OdbhutKakhotNangKhai, which shares the name Nang Khai. We have not been able to compare the two texts to see if there is any similarity. In March 2014, we photographed yet another manuscript in fragments, also entitled Nang Khai (EAP373_ DhamenMohanBoruah_NangKhai), but once again we have not been able to connect the text of that version to the version of Baparam Hati Baruah.

61 Tabassum is a Master’s graduate in linguistics from Gauhati University. This work was done between 2005 and 2008 some years before the EAP project commenced. The translation was conducted taking into account the earlier translation in Bimala Kanta Barua and N. N. Deodhari Phukan. Ahom Lexicons, Based on Original Tai Manuscripts (Guwahati: Department of Historical and Antiquarian Studies, 1964).

62 Toolbox is a dictionary-writing program produced by the Summer Institute of Linguistics, http://www-01.sil.org/computing/toolbox

63 We are working towards making the dictionary truly quadrilingual (Tai Ahom, English, Shan, Assamese) but this will take some time. Some entries are already quadrilingual, as with the entry for kai (chicken).

64 For the published version, see Stephen Morey, “A Sketch of Tai Ahom”, in Axamiya aru Axamar Bhasa [Assamese and the Languages of Assam], ed. by Biswajit Das and Axamar Bhasa (Guwahati: AANK-Bank, 2011). At present the best way to access the online Ahom materials is to follow a link to projects on the DoBeS website (http://www.mpi.nl/DoBeS), then Tangsa, Tai and Singpho in Northeast India, then click on corpus and then the node “Ahom”. All of the materials that we have deposited on the website are available for download.

65 Martin Hosken and Stephen Morey, “Revised Proposal to add the Ahom Script in the SMP of the UCS”, Working Group Document, 14 September 2012, http://www.unicode.org/L2/L2012/12309-ahom-rev.pdf

66 The Ahom font renders perfectly on Facebook using the Mozilla Firefox browser, once it is set as the default font. In other browsers and other platforms it may not work so well, as yet. The reason for these rendering issues is the way in which characters are coded. For example, the vowel /e/, is written before the consonant that it sounds after. So the word ke is written  which is e k. Unicode requires the /e/ to be encoded after the consonant and therefore the fonts have to be designed so that the vowel appears in front of the consonant even though it is encoded after. At present the Ahom Unicode font will not work properly in Microsoft Word, and for that reason in this paper and in our online dictionary and texts we are still using the old legacy font, designed by me in the 1990s.

which is e k. Unicode requires the /e/ to be encoded after the consonant and therefore the fonts have to be designed so that the vowel appears in front of the consonant even though it is encoded after. At present the Ahom Unicode font will not work properly in Microsoft Word, and for that reason in this paper and in our online dictionary and texts we are still using the old legacy font, designed by me in the 1990s.