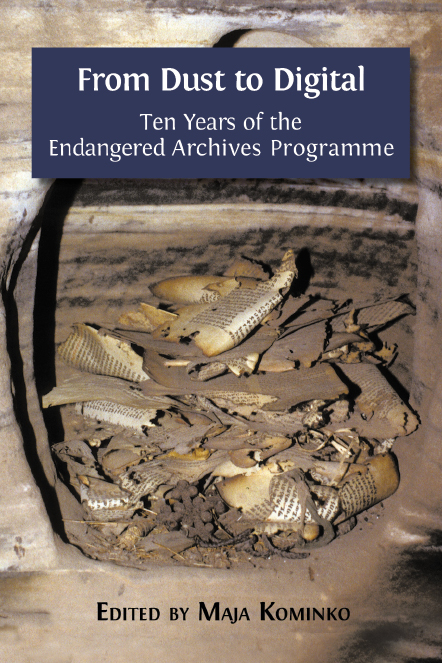

4. Technological aspects of the monastic manuscript collection at May Wäyni, Ethiopia1

© J. Tomaszewski and M. Gervers, CC BY http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0052.04

Located in the Horn of Africa, Ethiopia is one of the most ancient civilisations in the world, a place where traditional culture, firmly fixed in the past, is continually challenged by the customs of the modern world. One of the treasures of this country is its manuscript culture, inseparably tied to the Christian tradition. There are thousands of churches in Ethiopia, and stored in nearly every one are parchment manuscripts which contain ancient and sometimes unknown religious texts. This rich cultural heritage is particularly vulnerable to damage, loss and destruction, and requires a variety of approaches for its preservation.

One otherwise inconspicuous place is the village and ancient monastic site of May Wäyni in the northern province of Tigray. The complete collection of manuscripts there was digitised in 2013 under the auspices of the British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme (EAP).2 The site is located on a steep slope at a distance of nearly fifty kilometres south from Tigray’s capital city of Mekelle. It is situated a few kilometres away from the main road and is barely accessible by vehicle. The monastic enclosure stands alone on relatively flat terrain. According to local tradition, the monastery was founded by the saintly monk Father Qäsäla Giyorgis3 and flourished at the end of the fourteenth and the beginning of the fifteenth centuries. He was one of the companions of the important Ethiopian monastic figure Yohannes Käma, abbot of Däbrä Libanos Monastery in Šäwa.4

A provincial Ethiopian church library may generally contain about forty manuscripts, so the May Wäyni collection of 91 items is considered large.5 It consists not only of the standard set of books needed to perform the liturgy and other services, but also of important texts for the study of the history of Ethiopia and the Ethiopian Church, the literature of the Christian and Ethiopian Church, and the history of the manuscript book. Most of the manuscripts appear to have been copied in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries;6 only a few are decorated.

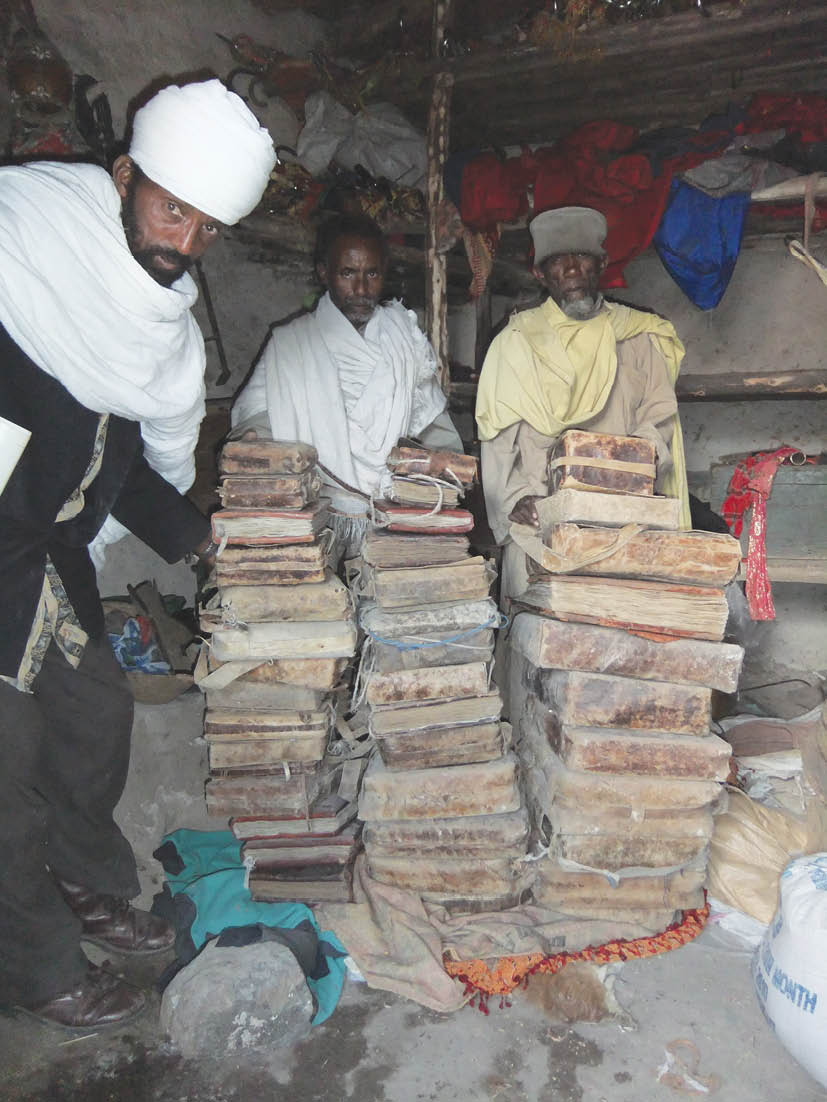

The old church of May Wäyni and its storage facility collapsed in recent years, and the construction of the new church has been delayed due to lack of funds. The manuscripts are presently stored in a relatively new “treasury” building made of mud and mortar, where most of them are stacked on a rough wooden rack, kept in heavy wooden boxes or hung on wall pegs (Fig. 4.1). Regularly-used liturgical books reside in the altar unit of the unfinished sanctuary of the new church. To prevent further damage to the manuscripts, the monks have distributed those not used during the daily services among themselves and the villagers. This arrangement is particularly unfortunate as it may lead to the increased dispersal and consequent loss of volumes.

Fig. 4.1 May Wäyni. Treasury building interior with

cased manuscripts on pegs. Photo CC BY-NC.

During an initial visit to May Wäyni in 2009, only some of the manuscripts were available to us in evaluating the extent of the collection and determining the scope of spiritual activity carried out in the compound. A prior inspection of the rugged terrain around the church and surroundings ruled out the possibility of setting up camp for the time required to digitise the books. Lack of water for cooking and drinking, or electricity for powering and charging the photographic and computer equipment, necessitated daily travel to and from Mekelle. On the one hand, these daily expeditions had their drawbacks — three hours a day were spent traveling, and because the churchyard was also used for religious purposes, the field station had to be established and dismantled daily. On the other hand, the evenings could be spent in the city downloading and backing up image files on computers, charging batteries and making necessary repairs to equipment.

Having made a positive assessment of the content of the archive, we agreed with the monks and representatives of the local community on how to establish the conditions for digitising the collection. These discussions substantially improved the efficiency of the process and at the same time allowed the benefits of the project to be presented to the local inhabitants. The previous experiences of teams studying or digitising manuscripts in various places in Ethiopia have shown that, despite lengthy negotiations ending in consensus, work may be frequently interrupted, often for trivial reasons.7 The assumption is that any collection of manuscripts is the property of the entire community, both lay and ecclesiastical, and the opposition of even a single member may bring all digitisation activity to a sudden halt. In such circumstances, no governmental or church authority can legally impose a decision on the community.8 Objective factors of this sort, in addition to the difficult field conditions, render the process of digitising in Ethiopia extremely complicated.9

With participation from representatives of the local church authorities, we established a detailed plan for the digitisation of the manuscripts and prepared all materials, tools, equipment and procedures. The recording of any collection in such difficult conditions as were encountered at May Wäyni requires elaborate preparation and the development of appropriate methods to facilitate the recording process.10 In the absence of on-site electricity, the team depended on a portable, gasoline-fuelled generator to run cameras and laptop computers. At May Wäyni, digitisation began in the ambulatory of the new, not yet finished church of St George, situated several hundred metres from the monastic buildings where the manuscripts were stored. Because the four-member team included a woman, work could not be conducted within the monastic compound itself. The manuscripts were therefore transported back and forth along a rough and narrow track.

The ambulatory, which is, fortunately, roofed, provided daylight suitably diffused by reflection from the bare stone walls. The team was thus able to operate relatively smoothly along a makeshift “assembly line” in the cambered space running below the oblong arcades through which the light passed.

Fig. 4.2 May Wäyni. Church ambulatory, assembly line set-up. Photo CC BY-NC.

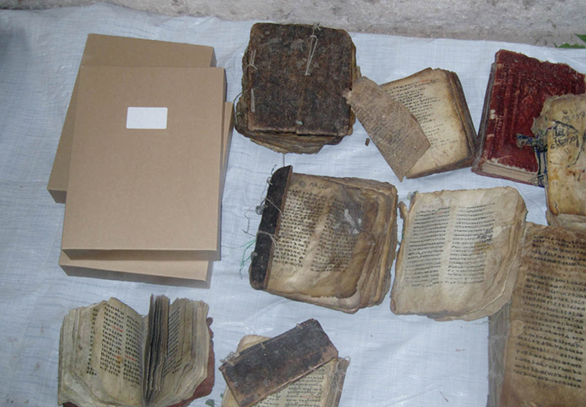

Other places were also organised: a temporary stocking of the manuscripts as they were successively transported from the treasury (Fig. 4.3), a provisional conservator’s field studio, a position where one could sit to paginate the manuscripts and prepare the metadata and, finally, two recording stations. Dusty ground, an incline and a rough floor were the negative aspects of this space, although these problems were resolved by spreading reed mats provided by the monks which, in turn, were covered with large tarpaulin sheets, and by propping boards on stones so that they could be rendered parallel to the camera lenses.

Fig. 4.3 May Wäyni. Preparing manuscripts in the iqabet for preliminary observation. Photo CC BY-NC.

No sooner had the team been established at this site than some members of the local community deemed it inappropriate, either for the kind of activity being carried out or because religious services were to be held there. As always in Ethiopia, there was an alternative, which in this case took the form of a large British army bell tent left behind by the Napier Expedition of 1868;11 it was there that most of the digitisation took place. Foliation and other preliminary activities continued in the open air, with a fallen tree trunk serving as the studio workbench.

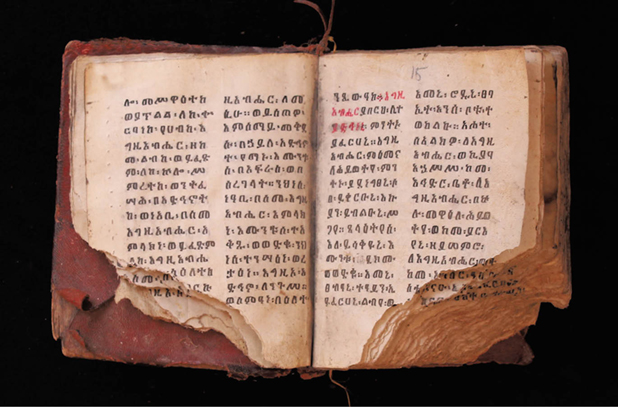

As each manuscript arrived from the treasury, it was checked by the conservator to determine how best to digitise it, while the condition of the folios, the handwriting and the painted decoration were recorded. All manuscripts were cleaned with a soft brush or small vacuum to remove impurities from the folios and the bindings. Some manuscripts required modest repairs to the leather which covered the wooden binding boards, or a strengthening of the sewn structure. The foliation and preparation of metadata provided a final opportunity to study the individual manuscript and to determine in which order the digitisation was to be executed. At a subsequent stage, recommendations for conservation focused mainly on protecting the book block and binding against cracking and on avoiding damage to the folios as digitisation proceeded. The shooting of manuscripts with damaged leather covers and spines, or manuscripts with leaves in an advanced state of deterioration caused by rodents, worms, damp, dirt, mold and tearing due to overly tight or inadequate stitching, had to be constantly monitored.12

Each of the two digitisation posts was equipped with a modest set of tools. In order not to have to change focal length more than a minimal amount from one manuscript to the next, large manuscripts were digitised at one post and smaller ones at the other. Volumes were stabilised on styrofoam or light plywood baseboards wrapped with black fabric, while custom-made velcro angle brackets held the covers in place. The construction of Ethiopian codices, whose book blocks are sewn with a chain stitch, allowed the volumes to be opened relatively easily and safely, although when tight bindings were encountered it was invariably difficult to capture fully the words written on the inner margins. In such cases, verso and recto folios were photographed separately rather than as a single image. It was possible to maintain an even plane for facing verso and recto folios by placing soft bags filled with styrofoam pellets below the side of the manuscript with the fewest folios turned.

Badly damaged manuscripts in which loose folios had been reattached by sewing with a stabbing technique, or where the cover was missing and the sewing which held the quires together had loosened or disappeared, presented particular difficulties.

Fig. 4.4 May Wäyni. A monk re-stitches a manuscript binding

in the church courtyard. Photo CC BY-NC.

In such cases, the positioning of the open folios had to be constantly manipulated in order to keep them within the frame of the angle fasteners. Depending upon the format and condition of the manuscript, folios could be kept in place manually by applying pressure to the margins with one to four transparent quarter-inch plexiglass rods with rounded bodies and polished ends. In especially arduous cases it was occasionally necessary for the entire four-person team to manage a single manuscript, with one person on the camera, a second on the computer and two holding down verso and recto sides of facing folios using the transparent rods.

In remote parts of the world, storage conditions are usually unsatisfactory and adequate means of preservation unavailable. Experience in the preservation of written materials from such areas has shown that attempts to transfer unrealistic recommendations and high standards invariably fail. Sometimes a simple, fundamental change to the method of storage, such as raising volumes from the floor, can effectively improve manuscript security. Guidance about simple and correct remedial treatments at May Wäyni showed that, with minimum effort, those responsible for the books could effectively protect them from further damage by improving their storage conditions. Traditionally, as in the case of a few codices at May Wäyni, Ethiopians have hung their cased manuscripts from wooden pegs inserted into the whitewashed earth wall of a roofed repository (see Fig. 4.1). With passing time, straps have broken and cases have been lost, leaving the floor as the most available alternative storage space. It is there, however, that they have become vulnerable to attack from water, damp and rodents. Increasingly, ecclesiastical libraries in Tigray are being equipped with closed metal shelving units, but not yet in May Wäyni, where the wooden shelves and the manuscripts they bear are all the more vulnerable to fire as well. The team placed most damaged manuscripts and those lacking their leather cases13 in special boxes made of acid-free cardboard.14

Fig. 4.5 May Wäyni. Particularly vulnerable manuscripts are stored

in acid-free cartons. Photo CC BY-NC.

The examination and recording of manuscripts at May Wäyni permitted a broad study of the technological aspects of Ethiopian manuscripts. This would not have been possible without our being able to handle them. Physical examination of individual manuscripts and the direct assessment of the condition of an entire collection helped to determine what lay behind their relative states of deterioration. The results of this survey at May Wäyni were reached through an analysis of existing damage to the parchment and to the writing and painting layer, as well as to the construction of the book blocks and the bindings.15

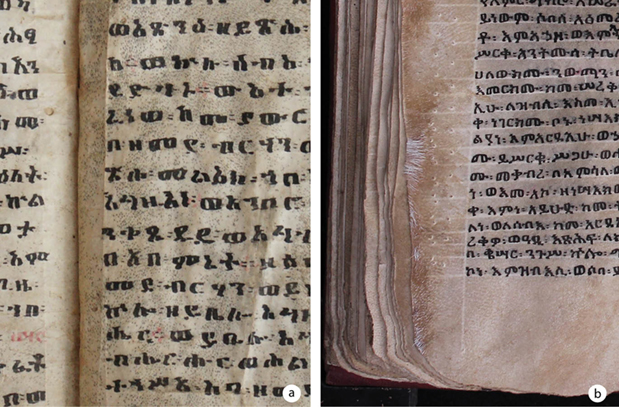

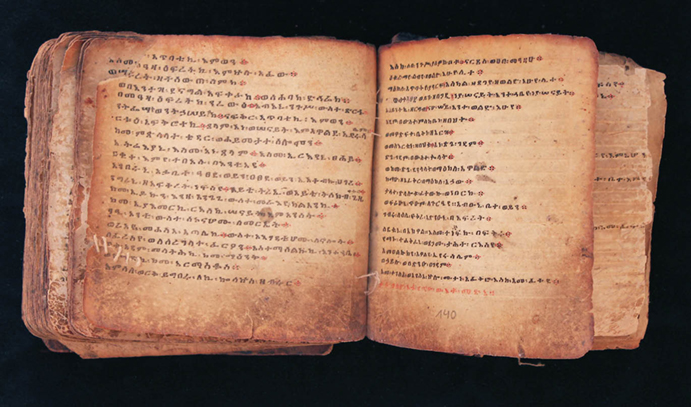

Ethiopian parchment has distinctive features that differentiate it from its European counterparts. Dissimilarities result mainly from different methods of manufacturing and indirectly from the type of mainly goat leather used to produce it.16 A fairly basic way of making parchment, without strong chemical processing, produces a relatively raw, rigid, uneven and sometimes hairy product, with large areas of gelatinisation on the surface (Fig. 4.6a and b).

Fig. 4.6 May Wäyni manuscripts. Examples of minimally-prepared parchment showing (a) hairy surface and (b) gelatinisation (EAP526/1/15 and EAP526/1/44), CC BY-NC.

For this reason, parts of some folios were semitransparent and already deformed at the time of creation. This effect is clearly visible on a number of pages from the manuscript containing the Sǝrᶜatä qǝddase [Order of the Mass] (EAP526/1/90), where ruled lines appear as light impressions because of changes to the structure of the semi-translucent parchment under the pressure of a metal ruler (Fig. 4.7). Visual assessment of the condition of all manuscripts in the collection indicated that, as a consequence of the progressive gelatinisation of the parchment, further deterioration appeared in the form of a glass-like layer on the surface of most of the folios.

Fig. 4.7 May Wäyni manuscript Sәrᶜatä qәddase [Order of the Mass] showing the structure of the semi-translucent parchment with traces of ruling (EAP526/1/90), CC BY-NC.

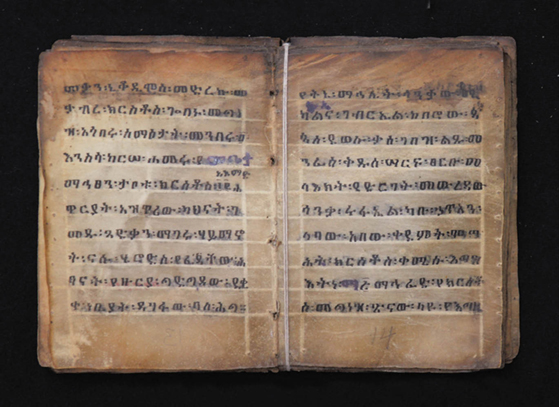

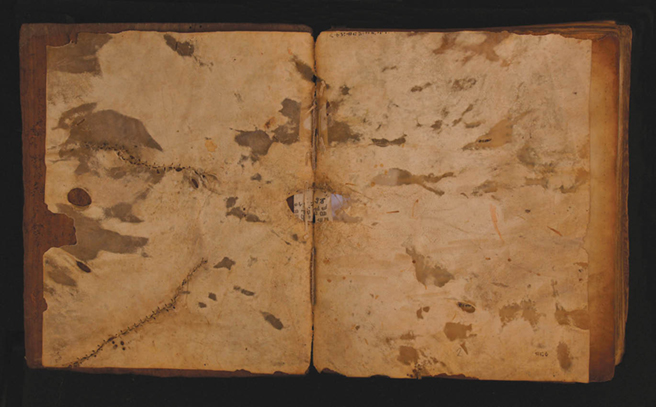

A majority of the manuscripts from the May Wäyni collection have to a large extent already been very badly demaged. In many cases, the degradation has affected entire parchment folios. Nearly 30% of the manuscripts bear traces of water stains caused by poorly-secured storage conditions. The parchment of these manuscripts has suffered damage mainly to the margins, which have become very stiff, brittle, fragile and therefore vulnerable to additional injury during use (Fig. 4.8). Nearly a quarter of the manuscripts have suffered further harm in varying degrees due to rodents (Fig. 4.9), while 11% of the total are largely deformed and severely damaged by use. On the positive side, the volumes showed no serious injury from microbiological agents. Resistance to the action of microorganisms can be caused by the fairly compacted structure of the collagen fibers. For the several manuscripts which were in extremely bad condition, special procedures had to be applied in order to digitise them.

Fig. 4.8 May Wäyni manuscript Mälә’әktä Ṗawlos [Letters of Paul] showing

extensive water damage (EAP526/1/56), CC BY-NC.

Fig. 4.9 May Wäyni manuscript Ṣälotä ᶜәṭan [The Prayer of Incense]

gnawed by rodents (EAP526/1/62), CC BY-NC.

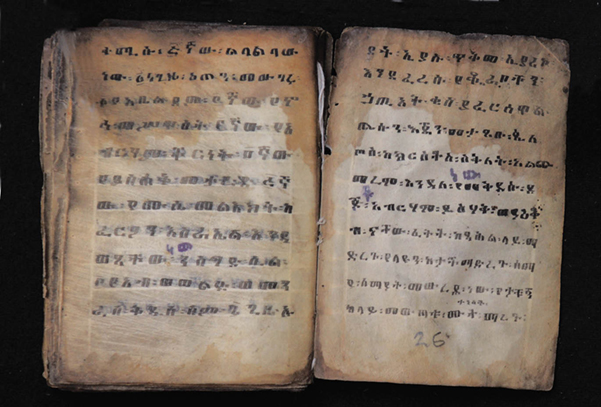

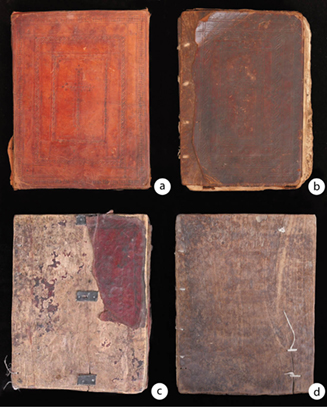

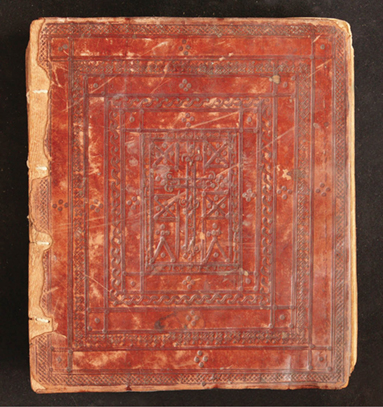

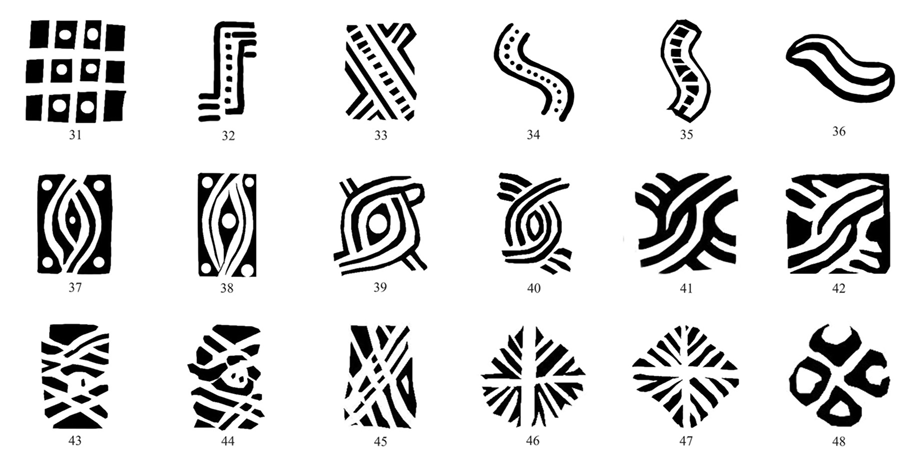

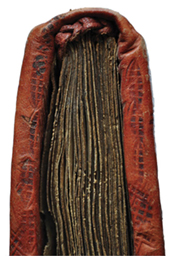

The state of the parchment folios was one problem, while that of the condition of the book blocks and manuscript bindings was quite another. The sewn structure of most manuscripts was in urgent need of repair. The binding boards of 30% of the manuscripts were found to be seriously damaged — cracking and warping being characteristic features of the wood used for the purpose in the region.17 It should be noted that the boards are generally bound in leather, which in over 40% of cases was found to be damaged in varying degrees. In most cases the leather at the edges of the covers or in the joints was torn, 16% had lost the leather on the spine, 13% had lost their leather covering altogether or nearly so, and in an additional 13%, small residues of leather were still visible on the inner sides of the boards. This type of damage is typical of Ethiopian bindings and results from a rapid deterioration of the leather.

The damages can be attributed mainly to such issues as the use of the book, the natural ageing of the materials and the unfavourable climate, but also to the use of a relatively weak adhesive.18 It seems that the bindings of most Ethiopian manuscripts go through similar stages of deterioration, which can be described as follows: the leather covering between the edges of the boards and the spine cracks and gradually disappears due to the weak attachment of the endband sewing to the covers; large losses of leather then occur at the corners and along all the edges of the boards; the leather separates completely from the spine and from both covers, remaining only as turn-ins. Finally, even the traces of the adhesive layers on both sides of the boards fade (Fig. 4.10).19

Fig. 4.10 May Wäyni manuscript book boards showing various stages of cover deterioration (a (EAP526/1/4) and b (EAP526/1/1), with sewn repairs

to c (EAP526/1/19) and d (EAP526/1/4)), CC BY-NC.

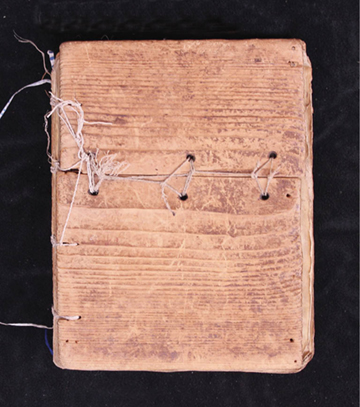

An overview of the collection revealed former methods of traditional manuscript repair and their scope. These methods were mainly provisional and were concerned only with maintaining the integrity of the whole book and its binding rather than with repairs to individual parchment folios. In 16% of the manuscripts, a plurality of sewn repairs were visible in different kinds of threads and cords, used particularly for connecting the book block to the covers (Fig. 4.11). Other typical treatments saw repairs to damaged and broken boards, which in 12% of the cases generally involved tying them together with string, leather strips, plastic cords or even wire, since other adhesives were unavailable (Fig. 4.12).20

Fig. 4.11 May Wäyni manuscript Arganonä wәddase [The Harp of Praise] by Giyorgis of Sagla showing a variety of threads and cords used to connect the book block to the covers (EAP526/1/23), CC BY-NC.

Fig. 4.12 May Wäyni manuscript Qeddus Gädlä Gäbrä Manfäs Qeddus [The Life of Gäbrä Manfäs Qeddus] showing sewn repairs to the front book board

(EAP526/1/30), CC BY-NC.

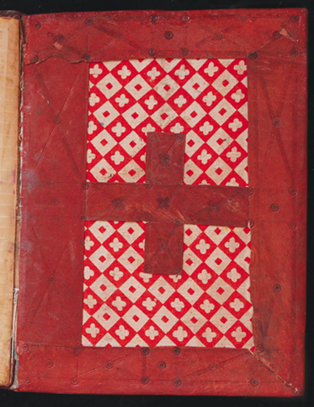

The main method of repair, however, was to re-sew the book block entirely and often to rebind the entire manuscript in new leather. Recent sewing is evident in 8% of the collection, although a larger number of volumes bound in new leather were also re-sewn. The procedure is clearly recognisable in the manuscripts devoid of leather covering and with exposed spines, where relatively fresh threads are visible (Figs. 4.11 and 4.12). As a rule, thoroughly repaired manuscripts were rebound using new materials. It was not unusual, however, to find discarded boards from older manuscripts reused for this purpose, as evidenced by additional holes located especially on the outer edge of the boards which formerly connected the cover to the book block.21 Newly bound manuscripts were covered with new leather and were decorated with blind tooling, using traditional patterns. As a result of such procedures, it sometimes proved difficult to determine whether the book had been subjected to any additional treatment. The only clue might be the relatively good condition of the binding compared to that of the folios of the manuscript.

Due to the lack of effective adhesives in Ethiopia, any local repairs to wooden boards or to manuscript folia tend to be rendered by sewing or linking with string or thongs. A major difficulty at May Wäyni was the state of damaged folio margins, as well as the gathering of individual folios which were broken along the folds. The May Wäyni collection exhibited very few examples of repairs to the margins of parchment folios. Some simple stitching is visible on the folios of manuscript EAP526/1/61.

Fig. 4.13 May Wäyni manuscript Mäzmurä Dawit [Psalms of David] showing loose folios held together by stab-stitching (EAP526/1/61), CC BY-NC.

Approximately 8% of the manuscripts which had fallen apart, leaving loose folios and quires, are currently held together by stab-stitching along the edges of the inner margins of all folios.22 Stabbing was the only effective means available for connecting the leaves of deteriorated manuscripts; the practice is broadly used not only in this collection, but also in many other places in Tigray and elsewhere in Ethiopia.23 In many cases, additional folded strips of parchment were inserted in order to span and reinforce individual folios before sewing.24

These manuscripts proved extremely difficult to photograph because the degree to which they could be opened was restricted by the stitching, and also because the folded strips covered words and letters along the inner margins of the folios. Since multiple photographs needed to be taken in such cases, an entire day could be spent digitising a single long manuscript of this sort. In the case of the extremely damaged manuscript containing the Mälǝᵓǝktä Ṗawlos [Letters of Paul, EAP526/1/56], the thread which was pierced well into the inner margin, and thus hindered the opening of the book, was removed.

In the absence of adequate methods and means for the effective repair of the original historic materials, the total rebinding of a manuscript was the most reasonable solution for its preservation.25 In this context, it was uncommon to find repairs to bindings in which bookbinders sought to maintain the original, decorated leather covers. In such cases, repairs were limited to the attachment of new leather to the spine and to the inner margins of the book boards, and to introducing new endbands. This type of repair was observed in 6% of the manuscript bindings in May Wäyni.26 Some of these books may have been re-sewn previously, as evidenced by ruptures to the original leather covering around the spine of the volume providing free access to the lacing holes in the boards. Very clear traces of such actions are visible on the binding of the Mäṣḥafä Tälmid [The Book of the Disciple] manuscript (EAP526/1/45).27

Fig. 4.14 May Wäyni manuscript Mäshafä Tälmid [The Book of the Disciple] showing the ruptures to the original leather covering around the spine of the volume that provide free access to the lacing holes in the boards, holes made for resewing the book (EAP526/1/45), CC BY-NC.

In this case, however, the repair did not include the pasting of new leather onto the spine. In examples where the repair was comprehensive, the original leather on the boards near the spine was trimmed and a new piece of leather was pasted on or under the edge of the old leather.

Direct contact with the May Wäyni manuscripts provided an opportunity to analyse their codicological and technological aspects. As the pages were prepared for writing, prick holes and metal point rulings were applied to designate the layout of columns and lines, invariably on the flesh side of each bifolio. The holes were predominantly round and were probably made with a locally produced awl (wäsfe). Folio rulings were made in two ways. In most cases (77%) each bifolium was ruled individually on the flesh side, after which the bifolia were assembled in quires (see Fig. 4.7). In the remaining 33% of manuscripts, another ruling system was applied. Once quires had been assembled and tacketed, they were ruled on the flesh sides which invariably faced each other. This system is clearly evident, especially in the middle bifolio of a quire with the hair side open, where lines on both pages do not coincide on the facing verso and recto folios.

In most May Wäyni manuscripts (about 70% of the collection), numeric quire signatures appear as guidelines for binding, but the system was not applied consecutively. The signature was most frequently placed on the first page of each quire, at the top of the inner margin (58% of cases); they also appear in the middle of the upper margin (34%). The system of quire signatures is sometimes more complex. In a few cases, for decorative purposes, ornamented numbers could be repeated three times in the upper margin. The signature occasionally appears in the upper right corner of the last page of one quire, and in the upper left corner of the first page of the next. Generally, the numeric signatures are turned into decoration, encircled by black and red dots and strokes, and often arranged in the form of a cross.28

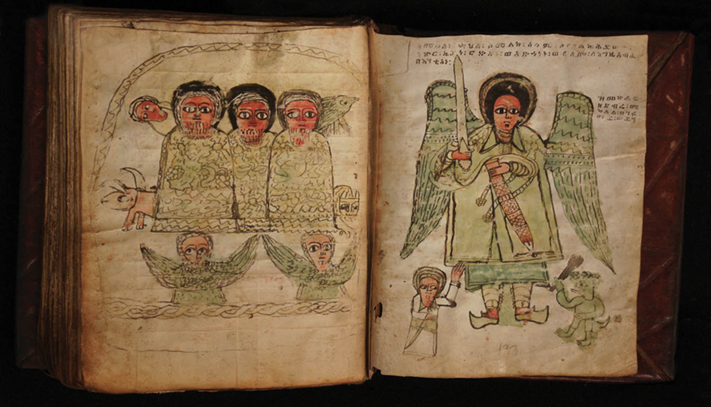

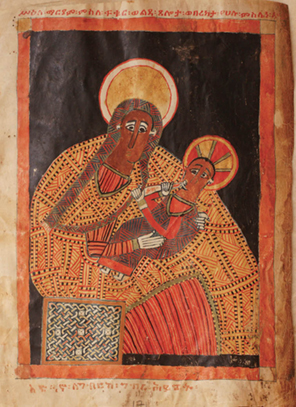

Decorated manuscripts are relatively few in the collection. The aniconic decoration, called ḥaräg in Ethiopic,29 used to mark the headings, chapters or a section of the text, is present in barely 15% of the manuscripts.30 Figural decoration as a full-page miniature or drawing appears very rarely, in only eight manuscripts.31 An exception is the richly decorated manuscript of Dǝrsanä Mikaᵓel [Homily in Honour of the Archangel Michael, EAP526/1/7], where six miniatures and a drawing are included.

Fig. 4.15 May Wäyni manuscript Dәrsanä Mikaᵓel [Homily in Honour of the Archangel Michael]. Full-page miniatures (EAP526/1/7), CC BY-NC.

Fig. 4.16 A rare fifteenth-century illumination of the Virgin and Child bound between folios 171 and 172 of a seventeenth-century copy of Täᵓammәrä Maryam

[The Miracles of Mary] (EAP526/1/41), CC BY-NC.

Other manuscripts contain miniatures which were added at a later time. For example, a much earlier miniature originating from another manuscript was added to Täᵓammǝrä Maryam [The Miracles of Mary] (EAP526/1/041) (Fig. 4.16).32 Mary is depicted in the miniature nursing Jesus, a type popular in the art of Coptic Egypt and known throughout the Byzantine world as Galaktotrophousa or Maria lactans.33 Colour and patterning add a decorative quality to the clothing of the highly stylised figures. The limited scale of colours applied in the miniature include red (cinnabar), blue (indigo), yellow (orpiment), light green (composed of two pigments: indigo and orpiment), light brown (the natural earth pigment modified by the addition of a small amount of cinnabar) and black (soot). An organic yellow appears also to have been applied to paint Mary’s maphorion and halo.34 All of these stylistic and technological features associated the miniature with a series of illustrated manuscripts attributed to the fifteenth century.35

The book blocks and the binding structures of all manuscripts in May Wäyni were analysed on site.36 The number of quires37 is usually a consequence of the contents of the volume.38 In practice, however, depending on when and by whom a particular version of the manuscript was copied, and on individual additions to it, the number of pages and quires can vary substantially (see Table 4.1).39

Table 4.1 List of the manuscripts showing details of construction of the book blocks.

|

Title of the Manuscript |

Number of manuscript |

Number of folios |

Number of quires |

Number of bifolia in quires* |

|

Mäṣḥafä täklil [Ritual of Matrimony] |

01 |

82 |

9 |

(3/5; 6/4) |

|

Arbaᶜətu wängelat [Gospel Book] |

02 |

158 |

19 |

(9/5; 9/4; 1/2) |

|

22 |

133 |

18 |

(12/4; 5/3; 1/2) |

|

|

Orit [Octateuch] and Mäṣḥafä kufale [The Book of Jubilees] |

03 |

170 |

16 |

(1/6; 14/5; 1/4) |

|

Nägärä Maryam [Mariology] |

04 |

112 |

14 |

(13/4; 1/3) |

|

Mäṣḥafä ṭәmqät [Ritual of Baptism] |

05 |

148 |

16 |

(1/7 4/5; 11/4) |

|

Rәtuᶜa Haymanot [The Orthodox One] |

06 |

291 |

38 |

(2/5; 31/4; 1/3; 3/2; 1/1) |

|

Dərsanä Mikaᵓel [Homily in Honour of the Archangel Michael] |

07 |

133 |

14 |

(9/5; 5/4) |

|

26 |

88 |

11 |

(11/4) |

|

|

Baḥrä ḥassab [Sea of Computation] |

08 |

90 |

9 |

(7/5; 2/4) |

|

Zəmmare [Antiphonary for the Eucharist] |

09 |

136 |

14 |

(1/6; 12/5; 1/2) |

|

Gädlä Kiros [Life of Our Father Kiros] |

10 |

56 |

7 |

(6/4; 1/2) |

|

16 |

54 |

6 |

(6/4) |

|

|

Mäṣḥafä qәddase [Missal] |

11 |

112 |

13 |

(1/6; 5/5; 5/4; 1/3; 1/2) |

|

17 |

130 |

15 |

(1/5; 14/4) |

|

|

25 |

115 |

15 |

(14/4; 1/0,5) |

|

|

54 |

292 |

23 |

(20/7; 3/6) |

|

|

58 |

65 |

8 |

(1/5; 7/4) |

|

|

82 |

58 (incomplete) |

9 |

(5/4; 2/3; 2/2) |

|

|

Mälkәᵓ [Portraits] |

12 |

202 |

26 |

(24/4; 1/3; 1/2) |

|

Täᵓammәr [Collection of Miracles] |

13 |

73 |

10 |

(8/4; 1/3; 1/2) |

|

Gädlä Gäbrä Manfäs Qeddus [Life of Gäbrä Manfäs Qeddus] |

14 |

60 |

8 |

(1/5; 5/4; 2/3) |

|

20 |

130 |

14 |

(13/5; 1/4) |

|

|

30 |

100 |

14 |

(10/4; 2/3; 1/2; 1/1) |

|

|

Ṣälotä ᶜәṭan [Prayer of Incense] |

15 |

54 |

8 |

(7/4; 1/2) |

|

51 |

34 |

4 |

(3/4; 1/3) |

|

|

Täᵓammәrä Iyasus [Book of the Miracles of Jesus] |

18 |

142 |

18 |

(17/4; 1/2) |

|

38 |

147 |

17 |

(17/4) |

|

|

44 |

41 |

6 |

(3/4; 2/3; 1/2) |

|

|

72 |

57 |

7 |

(1/5; 4/4; 2/3) |

|

|

75 |

70 |

10 |

(9/4; 1/2) |

|

|

Täᵓammərä Maryam [The Miracles of Mary] |

19 |

59 |

8 |

(5/4; 3/3) |

|

28 |

77 |

11 |

(9/4; 1/3; 1/2) |

|

|

33 |

73 |

9 |

(9/4) |

|

|

41 |

177 |

22 |

(3/5; 16/4; 1/3; 1/2; 1/1) |

|

|

74 |

84 |

9 |

(4/5; 5/4) |

|

|

Śәrᶜatä Yaᶜәqob zäśәrug [Order of James of Sarug] |

21 |

102 |

13 |

(12/4; 1/2) |

|

Arganonä wәddase [The Harp of Praise by Giyorgis of Sagla] |

23 |

175 |

22 |

(1/7; 21/4) |

|

Gäbrä ḥawaryat [Acts of the Apostles] |

24 |

91 |

15 |

(3/4; 10/3; 2/2) |

|

Dəggʷa [Antiphonary (Proper for the Divine Office)] |

27 |

60 |

6 |

(6/5) |

|

40 |

261 |

27 |

(3/6; 22/5; 1/4; 1/2) |

|

|

Dərsanä arba‘ətu ənsəsa [Homily on the Four Celestial Creatures] |

29 |

69 |

13 |

(9/4; 2/3; 1/2) |

|

Gubaᵓe qana [Collection of Hymns] |

31 |

149 |

18 |

(1/6; 2/5; 14/4; 1/3) |

|

Miscellanea. Collection of Marian Texts |

32 |

55 |

10 |

(3/4; 2/3; 4/2; 1/1) |

|

Gәbrä Ḥәmamat [Ritual of the Holy Week] |

34 |

184 |

21 |

(6/5; 15/4) |

|

Ṣomä dəggʷa [Antiphonary Proper for the Great Lent] |

35 |

88 |

9 |

(7/5; 2/4) |

|

Sərᶜatä qəddase [Order of the Mass] |

36 |

76 |

9 |

(9/4) |

|

90 |

26 (incomplete) |

- |

- |

|

|

Qəddase [Missal] |

37 |

117 |

12 |

(1/6; 9/5; 1/4; 1/3) |

|

Gädlä Täklä Haymanot [Life of St. Täklä Haymanot] |

39 |

101 |

13 |

(1/5; 8/4; 4/3) |

|

Zena śәllase [Narrative Teaching on the Holy Trinity] |

42 |

116 |

14 |

(14/4) |

|

66 |

95 |

11 |

(11/4) |

|

|

73 |

61 |

8 |

(6/4; 2/3) |

|

|

Gәnzät [Funeral Ritual] |

43 |

118 |

16 |

(15/4; 1/3) |

|

55 |

125 |

15 |

(5/5; 6/4; 2/3; 2/2) |

|

|

Mäṣḥafä Tälmid [The Book of the Disciple] |

45 |

192 |

18 |

(18/5) |

|

Gädlä sämaᶜәtat [Martyrology or Synaxarion] |

46 |

193 |

21 |

(13/5; 8/4) |

|

47 |

210 |

24 |

(17/5; 4/4; 1/3; 1/1) |

|

|

Mar Yəsḥaq [Book of St. Isaac the Syrian, of Nineveh] |

48 |

104 |

12 |

(12/4) |

|

Dərsanä Gäbrәᵓel [Homily on Gabriel] |

49 |

78 |

12 |

(5/4; 5/3; 2/2) |

|

Mäṣḥafä Mädḫané ᶜAläm [Book of the Saviour of the World] |

50 |

82 (incomplete) |

11 |

(1/5; 5/4; 5/3) |

|

68 |

76 |

9 |

(8/4; 1/3) |

|

|

Ṣälotä ᶜәṭan [The Prayer of Incense] |

70 |

47 |

6 |

(5/4; 1/3) |

|

62 |

120 |

14 |

(3/5; 11/4) |

|

|

Collection of Prayers |

52 |

53 |

3 |

(1/4; 2/3) |

|

Haymanotä abäw [The Faith of the Fathers] |

53 |

174 |

23 |

(21/4; 1/3; 1/2) |

|

Mäləᵓəktä Ṗawlos [Letters of Paul] |

56 |

51 (incomplete) |

- |

- |

|

71 |

35 |

7 |

(4/4; 2/3; 1/2) |

|

|

Mäzmurä Dawit [Psalms of David] |

59 |

50 |

5 |

(5/5) |

|

61 |

149 |

15 |

(12/5; 3/4) |

|

|

85 |

191 |

18 |

(11/5; 5/4; 1/3; 1/2) |

|

|

81 |

68 (incomplete) |

8 |

(3/5; 4/4; 1/3 |

|

|

Prayers to Mary |

57 |

50 (incomplete) |

- |

- |

|

Collection of Prayers for Weekdays |

60 |

86 (incomplete) |

7 |

(1/4; 6/3) |

|

Gädlä ḥawaryat [The Contendings of the Apostles] |

63 |

22 (incomplete) |

3 |

(1/6; 1/4; 1/3) |

|

Täᵓammərä Mikaᵓel [Miracles of Michael] |

64 |

36 |

4 |

(2/5; 1/4; 1/3) |

|

Gädlä Ṗeṭros zä-Däbrä Abbay [Acts of Petros of Däbrä Abbay] |

65 |

65 |

8 |

(8/4) |

|

Zena Mikaᵓel [Story of Michael] |

67 |

108 |

12 |

(4/5; 8/4) |

|

Mäṣḥafä krәstәnna [Ritual of Baptism] |

69 |

40 |

5 |

(5/4) |

|

Mäftəḥe śәray [Against the Magical Charms] |

76 |

38 |

5 |

(4/4; 1/2) |

|

Dərsanä Sənbät [Homily of the Sabbath] |

77 |

52 |

8 |

(2/5; 5/4; 1/3) |

|

Dərsanä Yaᶜәqob zäśәrug [Homilies of Jacob of Serug] |

78 |

40 |

5 |

(4/4; 1/3) |

|

Sälam Śəllase [In Praise of the Holy Trinity] |

79 |

30 |

5 |

(3/4; 1/2; 1/1) |

|

Raᵓәyä Yoḥannәs [Apocalypse of John] |

83 |

11 (incomplete) |

- |

- |

|

Keśtätä aryam [“Revelation on the Highest Heaven”] |

84 |

16 |

2 |

(2/4) |

|

Mäṣḥafä Ziq [Lesser Antiphony] |

86 |

52 |

7 |

(6/4; 1/1) |

|

89 |

21 |

2 |

(2/5) |

|

|

Dərsanä maḥyäwi [Homily of the Life-Giver] |

87 |

74 |

10 |

(8/4; 1/2; 1/1) |

|

Säyfä Mäläkot [The Sword of the Divinity] |

88 |

100 |

12 |

(1/6; 11/4) |

|

Arbaᶜətu wängelat [New Testament], Mäləᵓəktä [Letters], Yoḥannәs Afäwärq [Homily of John Chrysostom] |

91 |

55 (incomplete) |

8 |

(5/5; 3/4; 1/3) |

*The number of bifolia in quires are included in the right column: number of quires/number of bifolia in a single quire. Simplified data do not reveal the exact arrangement of irregular quires.

In well-preserved manuscripts, the number ranges from two to 38, but the majority of volumes are of medium thickness and contain from seven to fifteen quires (63%). In 57% of all manuscripts the number of folios in each quire is irregular, while the remainder are of quaternion format (33%), with eight leaves in each quire, and in quinion format with ten (10%). In most cases, books with disparate numbers of quires have leaves inserted at the end of the book block, rarely at its beginning. Manuscripts with an irregular structure are usually constructed of quires in quaternion and quinion format, with far fewer in formats of three and six bifolia. In one case, a relatively new paper manuscript with quires in seven or six bifolia was observed.40

All manuscripts, whether of regular or irregular construction, consist of bifolia and single leaves. In books with quires of mixed construction, the number of folios in a given quire is generally even, although odd number systems are not unusual; for example: 6/5, 4/5, 3/4, 2/3, and in the reverse order of 5/6, etc. The use of differing numbers of folios in quires is largely practical. It reflects the need to adapt quire structures to the content of the text and provides the opportunity to use smaller pieces of parchment by attaching single leaves on narrow strips between bifolia (Fig. 4.17).

Fig. 4.17 Drawing of a combined quire structure.

Protective flyleaves are widely used in book-block construction, and are most often added at the beginning of the manuscript, while the final protective sheet tends to be part of the last quire of the book. This last folio is often blank on both sides, although cases of leaves with text on the recto side were also noted. These records, frequently including small memorial texts and documents, could be very important for a local community. In many manuscripts, protective flyleaves are also present at the end of the book block, in which case they tend to have the same structure as those placed at the beginning. On occasion, however, their folio composition is irregular, indicating that no particular attention was paid to the consistent arrangement of the book.

Lower quality parchment was generally used in the preparation of flyleaves. Numerous stains, discolorations, defects and semi-transparency tend to be the main features of this material, whether inserted as separate protective flyleaves at the beginning of the manuscript (Fig. 4.18) or as the final unwritten folio of the last quire.41 In the latter case, the outer bifolio of the quire was chosen for the purpose. In this manner, the part used for the first written leaf could be of good quality parchment, while the last leaf of this bifolio (derived from the outer edge of the hide) would be less well-prepared, often damaged and gelatinised.

Fig. 4.18 May Wäyni manuscript Orit [Octateuch] and Mäṣḥafä kufale [The Book of Jubilees] showing low-quality folios used as protective flyleaves (EAP526/1/3), CC BY-NC.

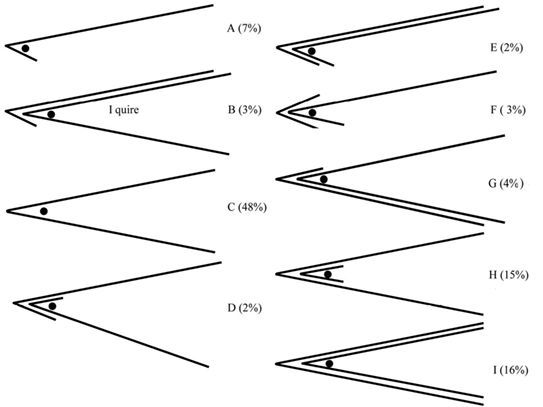

Separate protective end flyleaves were observed in 73% percent of all manuscripts. However, because many of the manuscripts are preserved in bad condition and are incomplete, it is likely that a significant number originally had additional folios which have not survived. Nine variants of flyleaves were observed, generally resulting from quires made of one or two bifolia. Nearly half of all manuscripts (48%) have a single bifolio as protective end flyleaves (Fig. 4.19c), and sixteen have two (Fig. 4.19i). There are other variants, in which single sheets of parchment retained by folded strips are sewn together to create bifolia (Fig. 4.19d and e).

Fig. 4.19 Distribution of flyleaf arrangements in the May Wäyni collection.

With but two exceptions, all the manuscripts were originally bound between wooden boards. In one example (EAP526/1/89), the manuscript has a limp binding made of thick parchment. This volume is rather small (12.5 × 15.5 centimetres) and contains only two quires bearing the text known as the Mäṣḥafä Ziq [Lesser Antiphony or Book of Antiphonal Chants]. Its cover is made of the same kind of parchment as that used to prepare the whole manuscript, with a similar disposition of ruled lines indicating that it could represent the original construction of the binding. Quires are attached to the covering material by means of straight long stitches, carelessly executed, running through the first and second quires. This simple and transitory way of binding is relatively rare, occurring mainly in small books of limited content (Fig. 4.20).

Fig. 4.20 May Wäyni manuscript showing straight long stitches on the spine (EAP526/1/89), CC BY-NC.

A second exception to the common form of binding between wooden boards is to be found in contemporary liturgical manuscripts written on machine-made paper (for example, Mäṣḥafä qәddase [Missal], EAP526/1/54). These covers were prepared from cardboard. Despite the use of modern materials, the form of the book, the writing materials used and the techniques for decorating its leather covers are still traditional.

12% of all manuscript bindings have been completely destroyed. Their folios are not secured and require urgent protection. It can only be assumed that, like most of the manuscripts, they were once secured by wooden covers. 21% have bare board bindings, a type showing no evidence of having previously been covered with leather. The remaining 66% are bound in leather-covered wooden boards.42 Of those currently bound only in boards, some presumably had leather covering in the past which has since disappeared.

Over 90% of the books from the May Wäyni manuscript collection were sewn with thick thread43 on two pairs of sewing stations, while only two small manuscripts were sewn on one pair and one on three pairs. Another group, comprising six manuscripts of small format, had three sewing stations (1.5 pairs).44 The clear tendency to use two pairs of sewing stations was common for small and relatively large manuscripts, regardless of their format.

The construction of the spine could be assessed for two-thirds of all the leather-bound volumes. In the remaining cases, both the spine and the endbands have been lost. A characteristic feature of Ethiopian bindings is the very simple spine structure. It is flat, untreated and covered only by leather, which is glued to the wooden boards. An exception is the Dǝrsanä Mikaᵓel [Homily in Honour of the Archangel Michael] manuscript (EAP526/1/7), in which an additional wide strip of leather has been applied to the spine. Threads connecting the covers to the book block have been stitched through the strip of leather, which was folded over the edges of the first and last quire, indicating that this feature was added at the time the book was sewn (Fig. 4.21).

Fig. 4.21 May Wäyni manuscript Dәrsanä Mikaᵓel [Homily in Honour of the Archangel Michael] showing spine lining with a wide strip of leather (EAP526/1/7), CC BY-NC.

At the top and bottom of the spine, this piece of leather was folded and braided endbands were sewn through it. As a result, on the back of a fully leather-bound book, the seams connecting the endbands to the leather spine and quires are invisible. Such use of additional material to strengthen the spine appears to have been rare in the Ethiopian bookmaking tradition. Further research may determine the extent to which bookbinders resorted to this solution or whether it appeared incidentally as a relic of the early Coptic technique.45

In the majority (70%) of well-preserved leather bindings, one finds endbands sewn on after the covering was complete. As in the previously-mentioned example, they are usually made of a two-thonged slit braid, stitched with threads to each quire and to the leather spine.46 As a rule, the longer ends of the braided endbands are sewn between the covers and the book block to the nearest book-sewing station. Although this is a common way of strengthening the construction of the binding, simple folded strips of leather were often used in place of braided thongs.47 This type of endband, though less decorative, provides considerably more strength to the binding as the covering material at the top and bottom of the spine is stitched not through two, but through four layers of leather (Fig. 4.22). Apart from these two predominant types, there are also numerous examples of manuscripts without any endbands (20%), resulting in a substantially weakened binding structure.

Fig. 4.22 May Wäyni manuscript Dәrsanä arba‘әtu әnsәsa [Homily on the Four Celestial Creatures] showing the endband made of a folded strip of leather (EAP526/1/29), CC BY-NC.

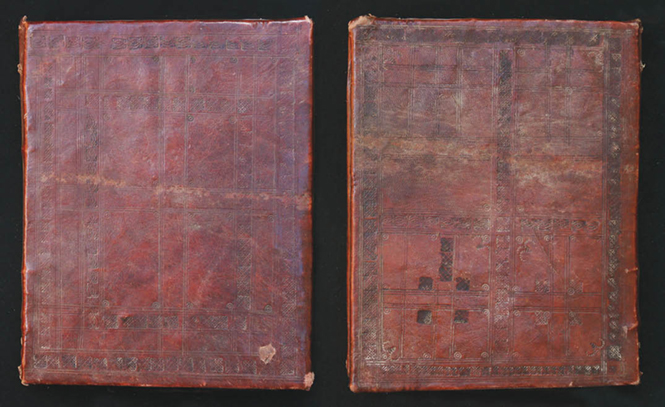

Another striking feature of Ethiopian manuscript bindings is the manner in which the inner face of the boards is finished. In 46% of cases, the surface of the boards between the wide leather turn-ins is inlaid with decorative textiles (Fig. 4.23),48 and less frequently with paper, in order to secure the book block and to decorate the manuscript. In other cases, the inner surfaces of the boards have been entirely covered with leather (30%), while in a number of cases the boards were left bare (24%). The types of fabrics used for this purpose are worthy of note. In addition to the relatively modest fabric of tabby or twill weave, monochrome (EAP526/1/25, 45, 46, 47) or with vertical stripes (EAP526/1/4, 87), examples of more decorative cloths occur. Fragments of Indian Masulipatam cloths (Fig. 4.23d),49 imported from the eighteenth to at least the early twentieth century, are recognisable because of their characteristic design and colour, along with other types of fabric carried to East Africa by Gujarati traders.50 Two small fragments of this plain-weave fabric, decorated with a black block-printed plant design and probably hand-painted brownish background, are used on the inner side of the binding of a manuscript containing the Gǝnzät [Funeral Ritual, EAP526/1/43,1; Fig. 4.23d]. Decorative shuttle-woven textiles bearing the “buta” motif also come from North India or Persia (Fig. 4.23a). Recognisable types of textiles used in bindings include satin (EAP526/1/42,1,117), damask (EAP526/1/23,1) and even tapestry weave (EAP526/1/37,1,118).51 Unique in this collection is a modest, dark blue-striped plain-weave textile insert made up of six narrow strips with their selvedges (Fig. 4.23b).52

All but one of the leather bindings from the May Wäyni collection are tooled with a variety of decorative motifs which are unusually well made. The preparation of the leather and the quality of the decorative tooling illustrate well-developed skills arising out of a long tradition. As a rule, the tooled decoration is based on a large, centrally-positioned cross, framed by an ornamental border. A limited number of tools with relatively simple patterns are used for decorating the leather-bound book covers of Ethiopian manuscripts.53 It is believed that the simple structure of Ethiopian binding is very similar to that of early Coptic codices.54 Presumably, all decorative elements of the binding also stem from this early period in the development of the codex. As the tradition of writing and bookbinding spread, patterns travelled with it such that similar ornamentation can be found on Syrian, Armenian and even European bindings from the Romanesque period. However, the limited number of examples from the early Coptic period makes it difficult to trace unambiguously the direction of influence. Richard Pankhurst found the closest similarity between Ethiopian and Armenian bindings, especially in the decoration of the central panel, the use of one or more bands in ornamental fringes and the employment of a number of similar tools.55 Despite the differences in binding and decorative techniques that have evolved through the centuries between these two traditions, a significant feature common to both is the application of decorative textiles to the inside of the covers.56

Fig. 4.23 Different types of textiles used as lining for the inner side of the manuscript bindings: (a) Indian plain-weave, shuttle-woven fabric (?) – with “buta” (Persian) or “boteh” (Indian) motif (EAP526/1/18); (b) six narrow strips of plain-weave fabric each with both selvedges (EAP526/1/48); (c) tapestry, plain-weave fabric (EAP526/1/37); (d) Indian Masulipatam plain-weave fabric, block-printed (EAP526/1/43), CC BY-NC.

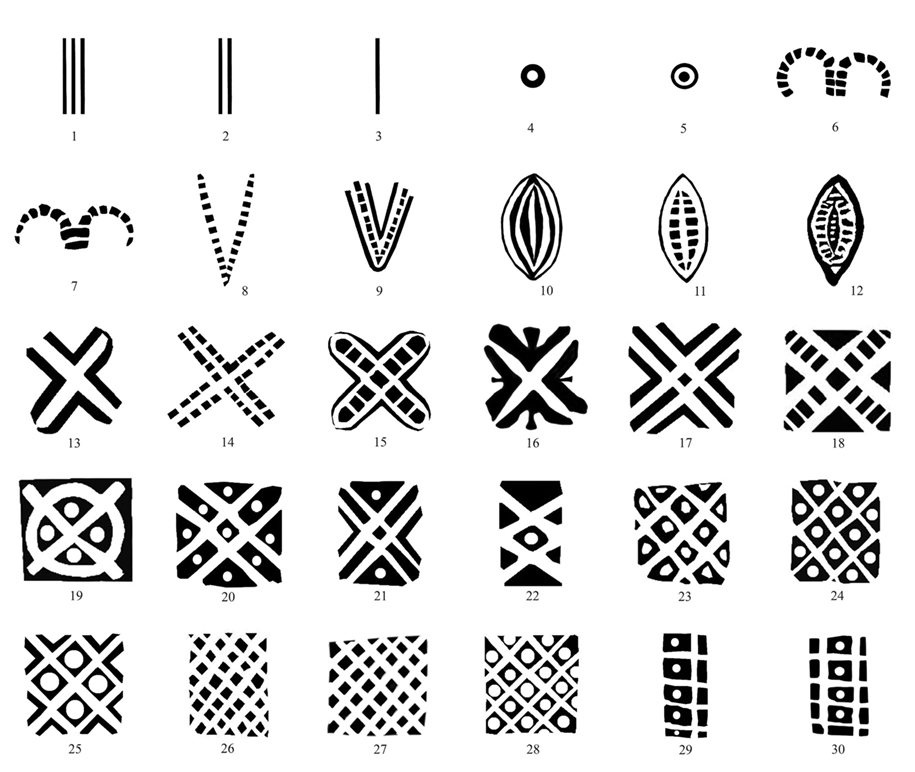

The literature mentions no more than ten basic tooled designs used by bookbinders (kwättač) for the decoration of Ethiopian bindings.57 The existing classification of individual patterns is, however, imprecise and needs to be systematised, especially in the context of early examples.58 The simple iron tools are all used for decorating the central, rectangular motif and surrounding frames (Fig. 4.24). The principal divisions of the composition are created using drawn pallets,59 giving the impression of single, double and triple lines. Equally popular are traditional motifs of diagonal crosses or X-form type,60 a motif resembling a palm tree or its leaf,61 an undulating or wave pattern, also called “mother of water”,62 and the rosette.63

Fig. 4.24 Set of iron tools for decorating bindings, CC BY-NC.

One of the oldest border designs, frequently appearing on the outer edge of the fringe, consists of an oblique chequered patterning or crisscross ornament. Because of its importance, this decoration is called Ge’ez, “head” or “principle”.64 Different strapwork or braided elements, used to build so-called zigzag type patterns65 are commonly enclosed in a square or rectangular shape. The typical tool set also includes a double wheel, called “dove’s eye”66 or corniform, which is also known as a single curved element in the form of a crescent.67 Other motifs occur, but they are less popular and tend to be used incidentally by local craftsmen.68

Virtually all the basic variations of decorative motifs are visible on the bindings in the May Wäyni collection. The most popular binding tools are those used for creating the framing fillets. Nine varieties of cross motifs could be identified, among which is a tool for producing a circle superimposed on a cross and complemented by four dots (Fig. 4.25: 19). Seven basic varieties of crisscross patterning are supplemented by a grid pattern which has not previously been noted in sets of bookmakers’ tools (Fig. 4.25: 29-31). The crisscross is used in conjunction with the above-mentioned patterns to create fillets. A variety of simple strap-work elements in the form of straight (Fig. 4.25: 32-33) and wavy shapes (Fig. 4.25: 34-36) together serve as the basis for a large group of tools used solely to create fillets as well as more complicated patterns arising from a broad braid motif (Fig. 4.25: 37-45). The first two from this group (Fig. 4.25: 37-38) are very popular and represent an intermediate form between the wave-like design and braiding.

Fig. 4.25 Tools found on bindings in May Wäyni collection. Straight lines: triple (1- EAP526/1/26), double (2- EAP526/1/37), single (3- EAP526/1/39). Circles: single (4- EAP526/1/4 [Ø≈5 mm]), double (5- EAP526/1/18 [Ø≈5 mm]). Corni-form (6- EAP526/1/4 [18 × 8mm], 7- EAP526/1/44 [17 × 8 mm). V-form: dotted (8- EAP526/1/11 [5 × 10mm], triple lines (9- EAP526/1/24 [9 × 12 mm]). Almond form: ‘mother of water’ (10- EAP526/1/4 [7 × 10 mm]), ’palm shape’ (11- EAP526/1/5 [13 × 6 mm], 12- EAP526/1/49 [12 × 6mm]). Diagonal cross: 13- EAP526/1/17 [7 × 7 mm], 14- EAP526/1/11 [8 ×8mm], 15- EAP526/1/5 [10 × 10 mm], 16- EAP526/1/4 [9 × 9 mm], 17- EAP526/1/18 [7 × 7 mm], 18- EAP526/1/87 [9 × 9 mm], 19- EAP526/1/48 [8 × 8 mm], 20- EAP526/1/42 [12 × 12 mm], 21- EAP526/1/11 [8 × 10 mm]. Criss-cross: 22- EAP526/1/7 [4 × 6 mm], 23- EAP526/1/26 [9 × 10 mm], 24- EAP526/1/15 [8 × 8 mm], 25- EAP526/1/18 [9 × 9 mm], 26- EAP526/1/49 [7 × 9 mm], 27- EAP526/1/5 [9 × 10 mm]; 28- EAP526/1/66 [8 × 8 mm]. Grid pattern: 29- EAP526/1/24 [7 × 13 mm], 30- EAP526/1/4 [10 × 15 mm], 31- EAP526/1/41 [12 × 12 mm]. Straight strapwork elements: 32- EAP526/1/3 [5 × 11 mm], 33- EAP526/1/18 [6 × 9 mm].Wavy lines: 34- EAP526/1/3 [5 × 14 mm], 35- EAP526/1/26 [6 × 15 mm], 36- EAP526/1/1 [4 × 10 mm]. Curve strapwork elements or ‘wave form’: 37- EAP526/1/13 [8 × 10 mm], 38- EAP526/1/15 [6 × 10 mm], 39- EAP526/1/18 [9 × 10 mm], 40- EAP526/1/49 [7 × 10 mm], 41- EAP526/1/22 [9 × 10 mm], 42- EAP526/1/31 [9 × 10 mm], 43- EAP526/1/22 [6 × 10 mm], 44- EAP526/1/41 [7 × 10 mm], 45- EAP526/1/41 [7 × 10 mm]. Rosette motives: 46- EAP526/1/25 [8 × 8 mm], 47- EAP526/1/31 [7 × 7 mm], 48- EAP526/1/46 [7 × 7 mm]. All images CC BY-NC.

Forms of simple rosettes (Fig. 4.25: 46-48) appear rarely, but are characteristic elements which allow the linking of individual bindings to a particular creator. A survey of the entire collection identified two types of the basic forms of this so-called “dove’s eye” tool. In contrast, the tool which gives the imprint of a single or double circle is common (Fig. 4.25: 4-5). Another pattern which has not previously been mentioned in the literature can be defined as the “V-form.” Two variations of this type of decorative tooling appear in the bindings of the May Wäyni manuscripts, one consisting of a single dotted line (Fig. 4.25: 8) and the other of two solid outer lines with a dotted line down the centre (Fig. 4.25: 9).

Established centuries ago, decorative conventions and most of the tools were rigidly prescribed by Ethiopian bookbinders.69 Many of these patterns were used by different binders in almost identical form, although in many cases small differences can be seen in the drawing or the size of the design. Finding these subtle differences may contribute to the identification of the individual binders. Although it is assumed that seven or more kinds of tools may be used to decorate large books, it is common to find only three used on small bindings.70 The number of border arms and of tools used depends more on the creativity of the bookbinder than on the format of the book. Not only did the diligence and accuracy of a scribe’s handwriting serve as testimony to his artistry, but it also promoted the splendour of the decorative binding that he prepared for his book. For this reason, as many designs and tools were applied as possible, and in many cases a sense of horror vacui is clearly visible.

Over 73% of the tooled fringes consist of two or three ornamental sequences. The remaining fringes are more complex, having four or five fringe arms. Only in one case is the central field encompassed by a single decorative frame. Normally, a seemingly simple traditional decorative surround is enriched with different varieties of the central cross theme, yet the number of variations based on such simple shapes and figures is remarkable. It is challenging to create a typology of these central elements, enclosed in a rectangular shape, because the wide variety of tooled ornaments differs from the basic compositional scheme. However, with some simplification, four main groups of motifs can be identified.71

Fig. 4.26 Decorative tooling on the central panels of the leather covering of four manuscripts from May Wäyni (a (EAP526/1/4), b (EAP526/1/16), c (EAP526/1/7), d (EAP526/1/31)), CC BY-NC.

In the simplest version, the ornamented central Latin cross stands alone or is sometimes found with an unobtrusive decorative background (Fig. 4.26a).72 The cross in the next group is enhanced by squares or triangles at the base (Fig. 4.26b). In the third group, rectangular forms appear below the cross with square ones at the top, thus creating an additional background outline for it (Fig. 4.26c).73 These forms could be further decorated with straight-line or dual-wheel tooling. In the last group, a church is represented schematically with a diamond-shaped cross on an architectural post rising above the pitch of the roof (Fig. 4.26d).74

The tooling of most of the bindings in the May Wäyni collection is based on these few characteristic schemes, only some of which received a marginally different decoration. Although it, too, is based on a cross motif, the tooled composition of the binding from a copy of the Zena śәllase [Narrative Teaching on the Holy Trinity, EAP526/1/73; Fig. 4.27] is less complex, but deserves particular attention due to its elaborate tooling. The upper cover consists of a centrally-arranged simple cross whose arms extend to the outer frame of a double, ornamental fringe. On the back cover, the fringe embodies a single ornamental sequence, while the central cross is filled with embossed decoration. Smaller crosses were placed in rectangular fields in the corners of the composition, the lower pair being additionally decorated with a blind, stamped pattern.

Fig. 4.27 May Wäyni manuscript Zena Sәlase [Narrative Teaching on the Holy Trinity]. Tooled leather binding (EAP526/1/73), CC BY-NC.

Tooling was not restricted to the covers. Blind tooling ornamentation can be observed in nearly 30% of the manuscripts from May Wäyni whose leather has been entirely preserved (Fig. 4.28).75 Most often, it consists of a rectangular segment dividing the surface into two to six fields, usually filled with diagonally arranged crosses. In some cases, smaller fields close the composition at the top and bottom of the spine. Less typical are designs consisting of a sequence of crosses, placed on the back of the book without segmental division, but usually enriched with additional small tool impressions. An unusual decoration appears on the manuscript of the Täᵓammǝrä Iyäsus [Book of the Miracles of Jesus, EAP526/1/44], whose spine is divided by oblique lines into triangular fields and embellished with impressions of rectangular stamps in a crisscross pattern (Fig. 4.28, right). The arrangement of decoration on the spines of these manuscripts has a purely decorative function and was introduced independently of the layout of the sewing stations.

Fig. 4.28 Tooled leather decoration on the spines of manuscripts (from left to right: EAP526/1/31, EAP526/1/22, EAP526/1/44), CC BY-NC.

Decorative stamping is further visible on the inner side of the covers, particularly on the wide leather turn-ins and strips pasted down on the binding edge of the wooden cover to form the border of the central field. This ornamentation is predominantly restricted to the tooling of straight lines, enhanced with double circles. Among the manuscripts from May Wäyni, of particular distinction is the very precisely made and relatively new binding of the Gädlä Ṗeṭros zä-Däbrä Abbay [Acts of Petros of Däbrä Abbay, EAP526/1/65]. On the inner side of the covers, the evenly trimmed leather margins form a border for the middle field lined with a plain-weave textile. The orange and white textile is printed in oblique diamonds which are filled alternately with impressions of small diamonds and four-leaf rosettes or crosses. Placed in the middle of the central panel is a square cross, also made of leather (Fig. 4.29). Both the cross and the border are tooled and divided into square and rectangular segments, the insides of which have been stamped with diagonal lines. Double circles and crosses are tooled in the corners of each field and where the lines intersect. In this case, the leather ornamentation seems to have been inspired by the geometric pattern of the printed textile.

Fig. 4.29 May Wäyni manuscript Gädlä Ṗeṭros zä-Däbrä Abbay [Acts of Petros of Däbrä Abbay] showing decoration of the inner side of the cover (EAP526/1/65), CC BY-NC.

Finally, tooled decoration can also be found on the edges of the covers. As on the inner side of the covers, the tooling on the edges serves both a decorative and technological purpose. The impression with a hot metal tool on moist leather enhances its adhesion to the cover. This type of decoration is present on about 30% of all bindings with preserved leather covers. Most often, it takes the form of a triple line running along all edges of the book. Less common is the impression of double circles or other patterns, including more complex decoration in which multiple lines and circles are integrated.

Fig. 4.30 May Wäyni manuscript showing tooled decoration on

the edges of the covers (EAP526/1/52), CC BY-NC.

The examination and recording of the May Wäyni manuscripts have provided the opportunity to develop a more general conservation strategy for manuscripts found in Ethiopia. The compromising storage conditions and the state of preservation of the collection are common to its rural counterparts throughout the country. Many, if not most, of these manuscripts are vulnerable to massive loss and destruction, and it is probable that large numbers will suffer such a fate sooner rather than later. To some extent, this situation can be marginally postponed by the ancient scribal tradition of copying books manually, a custom still practiced in various parts of the country. However, this method of replicating texts is insufficient, all the more so when one considers the example of late antique and medieval Europe. In the difficult conditions facing Ethiopia today, every effort needs to be undertaken to preserve both the tangible and the intangible history of the region. Digitisation is an extremely important and effective tool for the protection and preservation of this heritage but, faced with the enormous numbers of extant Ethiopian manuscripts, it can only succeed if accompanied by increased activity at the international level. In order to preserve the manuscript traditions of Ethiopia adequately there must be broad cooperation among Ethiopians and non-Ethiopians in the conservation of the most valuable literary works, sustained through training in modern conservation methods and, wherever possible, by supporting surviving scribal practices.

References

Abbadie, Antoine d’, Catalogue raisonné de manuscrits éthiopiens appartenant à Antoine d’Abbadie (Paris: Imprimerie impérial, 1859).

Alehegne, Mersha, “Towards a Glossary of Ethiopian Manuscript Culture and Practice”, Aethiopica: International Journal of Ethiopian Studies, 14 (2011), 145-62.

Ancel, Stéphane, “Yohannes Käma”, Encyclopaedia Aethiopica, 5, ed. by Siegbert Uhlig et al. (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2014), p. 81.

Balicka-Witakowska, Ewa, “Un psautier éthiopien illustré inconnu”, Orientalia Suecana, 33-34 (1984-86), 17-48.

—, Bausi, Alessandro, Claire Bosc-Tiessé, and Denis Nosnitsin, “Ethiopian Codicology”, in Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies, ed. by A. Bausi et al. (Hamburg: COMSt - Nordstedte: BOD, 2014), pp. 168-191.

—, “Recording Manuscripts in the Field,” Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies, ed. by A. Bausi et al. (Hamburg: forthcoming in 2015).

Chaitanya, Krishna, A History of Indian Painting: The Modern Period (New Delhi: Shakti Malik Abhinav, 1994).

Delamarter, Steve, and Melaku Terefe, Ethiopian Scribal Practice 1: Plates for the Catalogue of the Ethiopic Manuscript Imaging Project (Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2009).

Di Bella, Marco, and Nikolas Sarris, “Field Conservation in East Tigray, Ethiopia”, in Care and Conservation of Manuscripts 14: Proceedings of the Fourteenth International Seminar Held at the University of Copenhagen 17th-19th October 2012, ed. by Matthew J. Driscoll (Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, 2014), pp. 271-307.

Gast, Monika, “A History of Endbands, Based on a Study of Karl Jäckel”, The New Bookbinder, 3 (1983), 42-58.

Gervers, Michael, “The Portuguese Import of Luxury Textiles to Ethiopia in the 16th and 17th Centuries and their Subsequent Artistic Influence”, in The Indigenous and the Foreign in Christian Ethiopian Art: On Portuguese-Ethiopian Contacts in the 16th-17th Centuries: Papers from the Fifth International Conference on the History of Ethiopian Art (Arrabida, 26-30 November 1999), ed. by Manuel João Ramos with Isabel Boavida (Burlington: Ashgate, 2004), pp. 121-34.

Hable Selassie, Sergew, Bookmaking in Ethiopia (Leiden: Karstens Drukkers, 1981).

Haile, Getatchew, A Catalogue of Ethiopian Manuscripts Microfilmed for the Ethiopian Manuscript Microfilm Library, Addis Ababa and for the Hill Monastic Manuscript Library, Collegeville, 10 (Collegeville, MN: Saint John’s University, 1993).

Kane, Thomas Leiper, Amharic-English Dictionary, 2 (Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1990).

Lemenih, Mulugeta, and Frans Bongers, “Dry Forests of Ethiopia and Their Silviculture”, in Silviculture in the Tropics, ed. by Sven Günter, Michael Weber, Bernd Stimm and Reinhard Mosandl (Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 2011), pp. 261-72.

Liszewska, W., Conservation of Historical Parchments: New Methods of Leafcasting with the Use of Parchment Fibres (Warsaw: Akademia Sztuk Pięknych, 2012).

Machado, Pedro, “Awash in a Sea of Cloth: Gujarat Africa, and the Western Indian Ocean, 1300-1800”, in The Spinning World: A Global History of Cotton Textiles, 1200-1850, ed. by Giorgio Riello and Prasannan Parthasarathi (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), pp. 161-80.

Markham, Clements R., A History of the Abyssinian Expedition (London: Macmillan, 1869).

Mellors, John, and Anne Parsons, “Manuscript and Book Production in South Gondar in the Twenty-First Century”, in Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on the History of Ethiopian Art, Addis Ababa 5-8 November 2002, ed. by Birhanu Teferra and Richard Pankhurst (Addis Ababa: Institute of Ethiopian Studies, 2003), pp. 185-89.

Middleton, Bernard C., A History of English Craft Bookbinding Technique (New York: Hafner, 1963).

Pankhurst, Richard, “Indian Trade with Ethiopia, the Gulf of Aden and the Horn of Africa in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries”, Cahiers d’études africaines, 14/55 (1965), 455-97.

—, “Imported Textiles in Ethiopian Eighteenth Century Manuscript Bindings in Britain”, Azania, 16 (1981), 131-50.

—, “Ethiopian Manuscript Bindings and their Decoration”, Abbay, 12 (1983-1984), 205-57.

Peterson, Dan, “An Investigation and Treatment of an Uncommon Ethiopian Binding and Consideration of its Historical Context”, The Book and Paper Group Annual, 27 (2008), 55-62.

Simpson, William, Diary of a Journey to Abyssinia, 1868, ed. by Richard Pankhurst (Los Angeles, CA: Tsehai, 2002).

Szirmai, Janos A., The Archaeology of Medieval Bookbinding (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1999).

Tomaszewski, Jacek, Oprawy haftowane i tekstylne z XVI-XIX wieku w zbiorach polskich, t. 1, Kontekst historyczny [Embroidered and Textile Bookbindings from the 16th to the 19th Century in Polish Collections, I: Historical Context] (Warsaw: Akademia Sztuk Pięknych, Biblioteka Narodowa, 2013).

—, Balicka-Witakowska, Ewa, and Zofia Żukowska, “Ethiopian Manuscript Maywäyni 041 with Added Miniature: Codicological and Technological Analysis”, Annales d’Éthiopie, 29 (forthcoming in 2015).

Uhlig, Siegbert, Introduction to Ethiopian Palaeography (Stuttgart: Steiner, 1990).

Van Regemorter, Berthe, Some Oriental Bindings in the Chester Beatty Library (Dublin: Hodges, Figgis and Co, 1961).

Zanotti-Eman, Carla, “Linear Decoration in Ethiopian Manuscripts”, in African Zion: The Sacred Art of Ethiopia, ed. by Roderick Grierson (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993).

1 The transliteration of Ge’ez and Amharic words in this chapter is based on the system used by the Encyclopaedia Aethiopica (EAe).

2 EAP526: Digitisation of the endangered monastic archive at May Wäyni (Tigray, Ethiopia), http://eap.bl.uk/database/overview_project.a4d?projID=EAP526. The digitisation was

undertaken by Michael Gervers (University of Toronto, Canada), Ewa Balicka-Witakowska (Uppsala University, Sweden), Jan Retsö (Gothenburg University, Sweden) and Jacek Tomaszewski (Polish Institute of World Art Studies, Warsaw). The expedition was greatly facilitated by the cooperation of Ato Kebede Amare, General Manager for the Agency of Culture and Tourism in the National State of Tigray. The authors would like to thank Ewa Balicka-Witakowska for her important contributions towards the accuracy of this chapter.

3 We are grateful to Denis Nosnitsin for pointing out that the monastic rules he wrote are to be found in the nineteenth-century manuscript HMML, Hill Museum and Manuscript Library, Pr. No. 5000, for which see Getatchew Haile, A Catalogue of Ethiopian Manuscripts Microfilmed for the Ethiopian Manuscript Microfilm Library, Addis Ababa and for the Hill Monastic Manuscript Library, Collegeville, 10 (Collegeville, MN: Saint John’s University, 1993), p. 383.

4 Stéphane Ancel, “Yohannes Käma”, Encyclopaedia Aethiopica (hereafter cited as EAE), ed. by Siegbert Uhlig et al., 5 (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2014), p. 81f.

5 By way of comparison, Däbrä Sälam Mikaᵓel in Tigray is noted to have had 44 manuscripts in 1974 (EAE II, p. 39); Däbrä Baḥrәy in Wollo has 54 (ibid., p. 11); the old Aksumite church of Däbrä Libanos in Eritrea is known to have had at least 84 in 1994 (ibid., p. 29); Däbrä Ṣärabi in Tigray has 98. In the second quarter of the sixteenth century, Däbrä Bәśrat in Šäwa was said to have had hundreds (EAE II, p. 15). The monastery of Gundä Gunde currently has 219 manuscripts (see below, n. 7), having previously given an additional 65 to the re-established nunnery of Asir Matira. Gianfrancesco Lusini reports that the greatest manuscript collection in Eritrea is at Däbrä Bizän, holding 572 manuscripts (EAE II, p. 17a).

6 No information about dating was found in the colophons of the manuscripts. Furthermore, differences in the handwriting of the mid-seventeenth century to the mid-nineteenth century have proved difficult to distinguish, the more so since around 1800: “From about 1800 onward, the art of handwriting entered into a state of flux and styles developed which are parallel to those of the recent past and the present”. Siegbert Uhlig, Introduction to Ethiopian Palaeography (Stuttgart: Steiner, 1990), pp. 87-115 (p. 103).

7 EAP254 was diverted from the Shire region of Tigray Province, following an unexpected episcopal decision, and redirected to Romanat (Enderta region) with the assistance of the civilian Commissioner of Culture and Tourism. EAP340 was interrupted after the digitisation of only four manuscripts due to a dispute between the local community at Däbrä Sarabi (Tigray Province) and the regional agency responsible for repairing their church. An attempt carried out there by Ethio-spare in May 2014 was also unsuccessful.

8 The problem was presented by Ewa Balicka-Witakowska at the COMSt (Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies) conference: “La circulation des collections” (team 5, workshop 4), Paris, 12 January 2012.

9 An early project to preserve the content of manuscripts in Ethiopia was the Ethiopian Manuscript Microfilm Library (or EMML), which administered the microfilming, in Addis Ababa, of nearly 10,000 volumes from Šäwa province between 1973 and 1987. Since the introduction of digital photography, field expeditions have been mounted by Michael Gervers, Ewa Balicka-Witakowska, Denis Nosnitsin, Mersha Alehegne Mengistie, Meley Mulugetta Bazzabeh, Hasen Said and Steve Delamarter. Gervers and Balicka-Witakowska digitised the entire manuscript collection (219 items) of the monastery of Gundä Gunde in 2006 with the support of the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library at Saint John’s University (Collegeville, Minnesota); the collection is presently being prepared for open access over the internet by the Library of the University of Toronto Scarborough. In 2007, they digitised a further 65 manuscripts at Asir Matira (Tigray), which formerly belonged to Gundä Gunde, for the Hiob Ludolf Centre for Ethiopian Studies in Hamburg. More recently, digitisation in Ethiopia has been sponsored by the British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme (EAP254, the library of Romanat Qeddus Mika’el; EAP286, the collection of the Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Addis Ababa; EAP336, manuscripts of the lay bet exegetical tradition [about which see EAE II, p. 473]; EAP340, manuscripts from the monastery of Ewosṭatewos at Däbrä Särabi; EAP357, manuscripts from the Säharti and Enderta regions of Tigray; EAP401, Islamic manuscripts; EAP432, monastic collections from East Gojjam; EAP526, the monastic collection of May Wäyni) and by the European Research Council’s European Union Seventh Framework Programme (see: http://www1.uni-hamburg.de/ethiostudies/Ethio-spare).

10 Cf. Ewa Balicka-Witakowska, “Recording Manuscripts in the Field,” Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies, ed. by A. Bausi et al. (Hamburg: COMSt - Norderstedt: BOD, 2014), pp. 626-31.

11 On the Napier expedition, see Clements R. Markham, A History of the Abyssinian Expedition (London: Macmillan, 1869). For images of the bell tent, see William Simpson, Diary of a Journey to Abyssinia, 1868, ed. by Richard Pankhurst (Los Angeles, CA: Tsehai, 2002), p. 87.

12 The digitised manuscripts mentioned in this chapter are available at http://eap.bl.uk/database/results.a4d?projID=EAP526.

13 Amharic: maḥdär.

14 Some manuscripts were customarily covered with cloth jackets (Amharic: lǝbas and its types suti, gǝmǧa, šǝfan). See Mersha Alehegne, “Towards a Glossary of Ethiopian Manuscript Culture and Practice”, Aethiopica: International Journal of Ethiopian Studies, 14 (2011), 145-62 (p. 153).

15 Observations on the nature of Ethiopian binding and its structure were published recently in Marco Di Bella and Nikolas Sarris, “Field Conservation in East Tigray, Ethiopia”, in Care and Conservation of Manuscripts 14: Proceedings of the Fourteenth International Seminar Held at the University of Copenhagen 17th-19th October 2012, ed. by Matthew J. Driscoll (Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, 2014), pp. 271-307.

16 For the traditional technology of parchment production, see Sergew Hable Selassie, Bookmaking in Ethiopia (Leiden: Karstens Drukkers, 1981), pp. 9-12; John Mellors and Anne Parsons, “Manuscript and Book Production in South Gondar in the Twenty-First Century”, in Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on the History of Ethiopian Art, Addis Ababa 5-8 November 2002, ed. by Birhanu Teferra and Richard Pankhurst (Addis Ababa: Institute of Ethiopian Studies, 2003), pp. 185-89. The results of scientific research on the properties and character of Ethiopian parchment are noted in W. Liszewska, Conservation of Historical Parchments: New Methods of Leafcasting with the Use of Parchment Fibres (Warsaw: Akademia Sztuk Pięknych, 2012), pp. 380-98.

17 Species used to produce cover boards for books are mainly Cordia Africana (Wanza), Juniperus procera (Gatira) and Olea Africana (Weyra). Widespread use of these types of wood arises from the popularity of these trees in church woodland in Ethiopia. See Mulugeta Lemenih and Frans Bongers, “Dry Forests of Ethiopia and Their Silviculture”, in Silviculture in the Tropics, ed. by Sven Günter, Michael Weber, Bernd Stimm and Reinhard Mosandl (Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 2011), pp. 261-72 (p. 269).

18 Currently, wheat starch paste is commonly used for this purpose (Sergew Hable Sellassie, Bookmaking in Ethiopia, p. 25), but there is no information on the kinds of adhesives used in the past. It appears that another type of adhesive was originally used on the binding of manuscript EAP526/1/48. Survey tests by Raman spectroscopy of a sample of the binding substance excluded starch glue and gums and confirmed the presence of elements characteristic of gum resins (tests were carried out by the Faculty of Chemistry of the Warsaw University of Technology). In the absence of relevant chemical samples, however, it was not possible to identify the binder.

19 Jacek Tomaszewski, Ewa Balicka-Witakowska and Zofia Żukowska, “Ethiopian Manuscript Maywäyni 041 with Added Miniature: Codicological and Technological Analysis”, Annales d’Éthiopie, 29 (forthcoming in 2015).

20 Different types of material for repairing boards are visible on the bindings: EAP526/1/3, EAP526/1/14, EAP526/1/19, EAP526/1/30, EAP526/1/32, EAP526/1/33, EAP526/1/40, EAP526/1/51, EAP526/1/61, EAP526/1/64, EAP526/1/70, EAP526/1/74, EAP526/1/85 and EAP526/1/86. Other examples are illustrated in Steve Delamarter and Melaku Terefe, Ethiopian Scribal Practice 1: Plates for the Catalogue of the Ethiopic Manuscript Imaging Project (Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2009), p. 35, plates 7, 22, 45 and 65.

21 Additional lacing holes are visible on opposite sides of the boards of EAP526/1/34 and EAP526/1/50. The practice is also noted by Di Bella and Sarris, p. 302.

22 The technique of stabbing is described in detail by Bernard C. Middleton, A History of English Craft Bookbinding Technique (New York: Hafner, 1963), pp. 11-12.

23 Further examples of stabbing in the May Wäyni collection are visible in manuscripts EAP526/1/57, EAP526/1/80, EAP526/1/85 and EAP526/1/89. Good examples of this practice are also to be found in manuscripts from the monastery of Märᵓawi Krәstos, where such repairs were made systematically. See also Delamarter and Melaku Terefe, plate 22.

24 Additional folded strips (Amharic: sir) appear in EAP526/1/63, EAP526/1/83 and EAP526/1/91; see also Delamarter and Terefe, plate 25.

25 This observation relates to other book collections observed in Tigray province. Examples of rebound manuscripts can be found, for example, in the book collections of Däbrä Abbay and Märᵓawi Krәstos (Shire region), among many others. Total rebinding has been widely used in Europe in the past. For information on rebinding in the fifteenth century, see Janos A. Szirmai, The Archaeology of Medieval Bookbinding (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1999), p. 277; and for rebinding in England in the nineteenth century, see Middleton, p. 6. In modern Europe, many of the medieval ecclesiastical books have received new bindings made in accordance with contemporary fashion and design.

26 New leather is clearly visible on the spine of the following manuscripts: EAP526/1/2, EAP526/1/17, EAP526/1/22, EAP526/1/41 and EAP526/1/67. See also Delamarter and Terefe, plate 85.

27 Such repairs were observed on manuscripts EAP526/1/1, EAP526/1/9, EAP526/1/23, EAP526/1/25 , EAP526/1/34, EAP526/1/45, EAP526/1/46 and EAP526/1/3.

28 See, for example, EAP526/1/53 ff. 11v and 12r, and EAP526/1/91 f. 8r; and Delamarter and Terefe, plates 4, 12, 30, 32 and 48.

29 Carla Zanotti-Eman, “Linear Decoration in Ethiopian Manuscripts”, in African Zion: The Sacred Art of Ethiopia, ed. by Roderick Grierson (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993), pp. 63-67; Ewa Balicka-Witakowska, “Ḥaräg”, in EAE II, pp. 1009a-1010b.

30 EAP526/1/5, EAP526/1/6, EAP526/1/8, EAP526/1/13, EAP526/1/21, EAP526/1/24, EAP526/1/28, EAP526/1/30, EAP526/1/39, 40, EAP526/1/42, EAP526/1/61, EAP526/1/65, EAP526/1/67 and EAP526/1/78.

31 Painted miniatures are found in manuscripts EAP526/1/7, EAP526/1/23, EAP526/1/41, EAP526/1/49 and EAP526/1/79. Some small drawings are also to be found in manuscripts EAP526/1/18, EAP526/1/22 and EAP526/1/40.