5. Localising Islamic knowledge: acquisition and copying of the Riyadha Mosque manuscript collection in Lamu, Kenya1

© Anne K. Bang, CC BY-ND http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0052.05

In Lamu, Islamic practice and intellectual traditions in the late nineteenth century were strongly marked by the foundation of the Riyadha Mosque, established by Ṣāliḥ b. ʿAlawī Jamal al-Layl, known in East Africa as Habib Saleh (1853-1936).2 He was a descendant of early migrants from Ḥaḍramawt, Yemen, who settled in Pate in the late sixteenth century. From there, the Jamal al-Layl family branched out to the urban centres of East Africa, including Zanzibar and the Comoro Islands. Being not only of Ḥaḍramī (and thus Arab) origin, but also claiming Sharīfian descent (i.e. in direct patrilineage from the prophet Muḥammad), the male representatives of the Jamal al-Layl clan in East Africa were able to take up professions as religious experts, often in combination with roles as traders.

As part of the stratum collectively called the ʿAlawī sāda, the Jamal al-Layl family was also known to adhere to the brand of Sufism (Islamic mysticism organised in ṭarīqas, or brotherhoods) known as the ṭarīqa ʿAlawiyya. The “ʿAlawī way” rests on a dual silsila (chain of spiritual transmission). The first links back to Shuʿayb Abū Madyan (d. 1197 in the Maghreb) and shares the same origin as the more widely diffused ṭarīqa Shādhiliyya.3 However, in Ḥaḍramawt, the ʿAlawiyya was for centuries perpetuated as “clan Sufism” among the sāda, its spiritual secrets understood to rest within the bloodline of the prophet. This came to be known as a second chain of transmission, and in turn made for a tight-knit stratum that upheld strict rules of endogamous marriage and control of access to knowledge. However, by the nineteenth century, the idea that mystical knowledge was accessible only to males born to a sayyid father had somewhat retreated, probably due to centuries of widespread migration and the accompanying need for intermarriage into host societies in East Africa, Southeast Asia and India. The shift was also likely the result of an ongoing intellectual reform within the ʿAlawī ṭarīqa, closely connected to reformist ideas emerging within the wider Islamic world. What we do know is that in late nineteenth-century East Africa, representatives of the ṭarīqa ʿAlawiyya were ready to teach non-ʿAlawīs to marry their daughters to them and initiate them into the ṭarīqa.

Habib Saleh was born in Grande Comore, but left as a young man to stay with relatives in Lamu. He returned to Grande Comore again, but finally settled in Lamu some time in the late 1870s or early 1880s. His biography, as well as his religious and intellectual formation are well documented in earlier studies and will not be repeated at length here.4 However, one aspect that must be addressed is Habib Saleh’s spiritual connection to his Sufi master in Ḥaḍramawt, the renowned teacher, saintly figure and scholar ʿAlī b. Muḥammad al-Ḥibshī (d. 1915).5 In the history of the ʿAlawī ṭariqa, al-Ḥibshī is known as part of a group of scholars who were the driving force behind what has been termed a “reform” of the religious precepts of the ʿAlawiyya. It may be argued whether or not this reform actually constituted a clear break with the past, but what is clear is that their emphasis on institution building (first and foremost in the form of religious schools for primary and higher education, known as ribāṭs), changed the ways in which Islamic knowledge was transmitted. Rather than restricting transmission to the personal relationship between a murshid (master) and his student (murīd), Islamic — and even Sufi — knowledge was now understood as a set of texts that could be taught in classes, following an organised curriculum. As a consequence, these institutions emphasised written authority, in the sense that they favoured text (and, specifically text in Arabic) over oral transmission.

The ribāt founded by al-Ḥibshī in Sayʾūn, Ḥaḍramawt, was named al-Riyāḍ (The Garden), and received students from the wide diaspora of Ḥaḍramī ʿAlawī migrants in the Indian Ocean. The efforts of scholars like al-Ḥibshī influenced like-minded scholars (ʿAlawīs primarily, but also non-ʿAlawīs) who founded similar teaching institutions not only in East Africa, but also further afield in the Indian Ocean, including Indonesia.6 The Riyadha Mosque and its teaching institution was explicitly modelled on that of al-Riyāḍ in Sayʾūn, and the impact of al-Ḥibshī on the Riyadha was to be long standing. In the Riyadha library there are manuscript copies of al-Ḥibshī ’s writings, his khuṭbas (Friday sermons) and his mawlid (text recited on the occasion of the birth of the Prophet Muhammad) Simṭ al-durar.7

The construction of the Riyadha Mosque was made possible through the help of Sayyid Manṣab b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān (1828-1922).8 He was a Lamu-born Ḥaḍramī ʿAlawī scholar very much in touch with reformist ideas then current in Ḥaḍramawt as well as in Mecca. After a career that included studies in Mecca and Ḥaḍramawt, and long periods as qāḍī (Islamic judge) of Dar-es-Salaam and Chwaka, Zanzibar, he returned to Lamu as a revered religious authority, especially consulted upon questions of Arabic language and grammar. In 1903, he transformed some of his land in Lamu into a waqf (pious endowment) for the purpose of building the Riyadha.9 However, it should be noted that Habib Saleh started his teaching activities several years earlier, probably shortly after he settled in Lamu some time between 1875 and 1885.10

From the very beginning, the main hallmark of the Riyadha was the incorporation of ritual traditions derived from al-Ḥibshī (notably the Simṭ al-durar, also known as the Mawlid al-Ḥibshī). However, the most enduring reformist agenda of the Riyadha was the admittance of students from beyond the stone town itself (Oromo, Giryama, Pokomo and others). These groups had until then been considered “outsiders” by the traditional Lamu aristocracy, and many of them were former slaves.11

The manuscript collection of the Riyadha Mosque

The manuscript collection of the Riyadha consists of approximately 150 manuscripts, presently housed in the library of the educational facility of the mosque. It is the largest privately held collection of Islamic manuscripts known to exist in Kenya, and the manuscripts date from the early nineteenth century to the 1930s. In terms of content, it ranges from 700-page tomes of Islamic law to smaller leaflets of 20-50 pages meant for use in an educational setting. The older manuscripts are bound in leather, while the more recent are written by pen in lined schoolbooks. The Riyadha collection is unique from several perspectives. Firstly, it provides an important overview of the historical orientation of Islamic education in East Africa. Secondly, several of the manuscripts have inscriptions that name owners over decades, indicating the economy of books and reading. Thirdly, the presence in some of the manuscripts of inter-linear Swahili translations in the Arabic script allows for research on the use of the Arabic script before colonial education.12

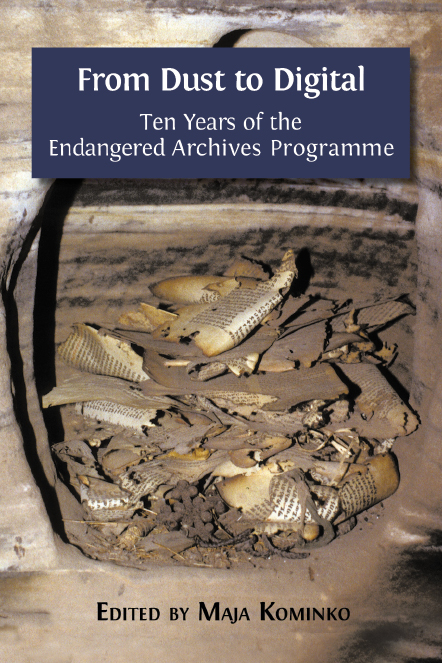

Lastly, the collection holds copies of texts authored by East African scholars themselves, sometimes in the author’s own hand. One prominent example is EAP466/1/38 (Fig. 5.1) by the Brawa-born scholar Muḥyī al-Dīn al-Qaḥṭānī (ca. 1790-1869), Sharḥ tarbiyyat al-aṭfāl: a commentary on the text “Tarbiyyat al-aṭfāl” [Instruction for children]. Al-Qaḥṭānī was a renowned scholar on the coast.

Fig. 5.1 First page of Sharḥ Tarbiyyat al-aṭfāl by Muḥyī al-Dīn al-Qaḥṭānī (d. Zanzibar, 1869). Possibly in the author’s own hand (EAP466/1/38, image 3), CC BY-ND.

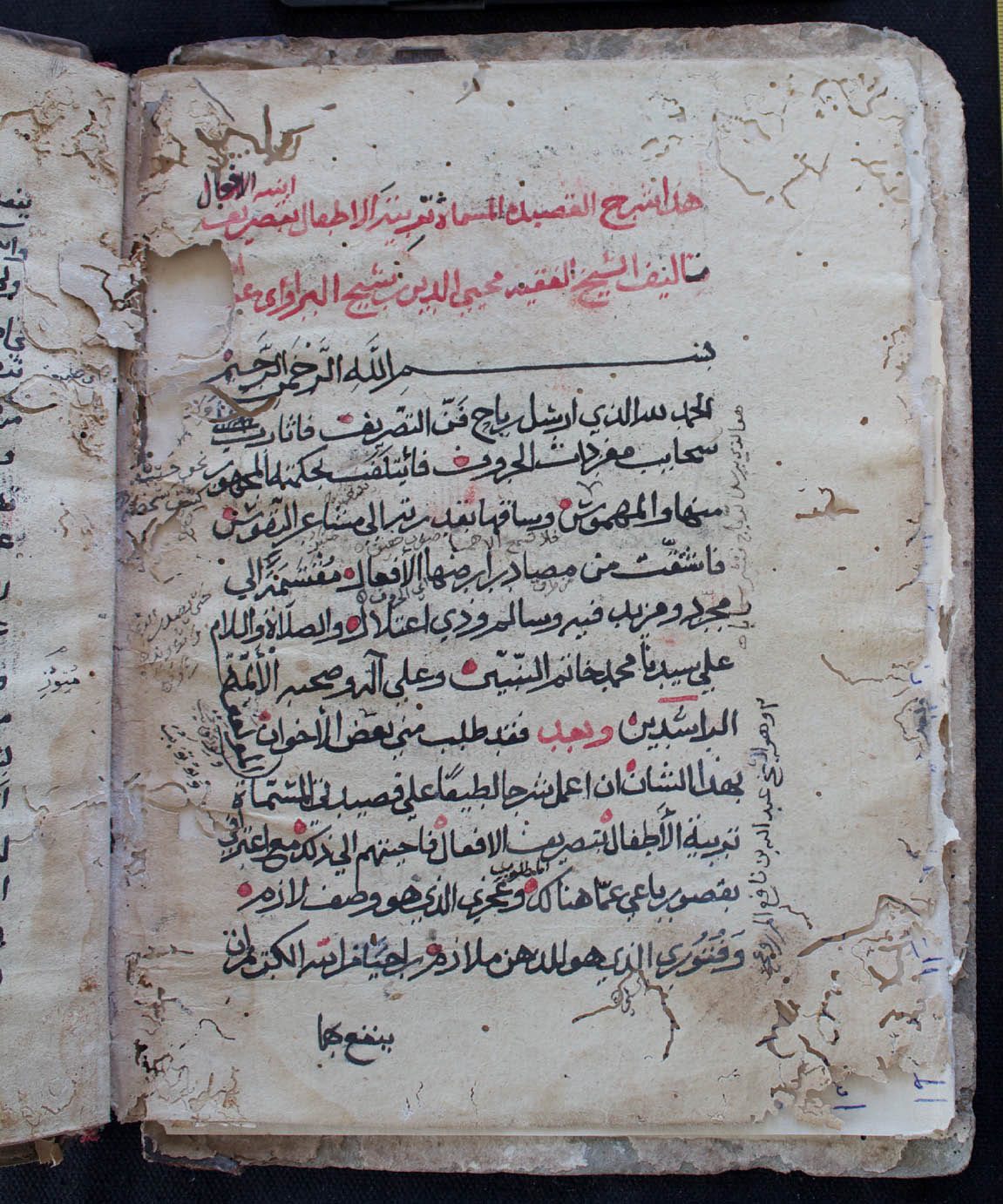

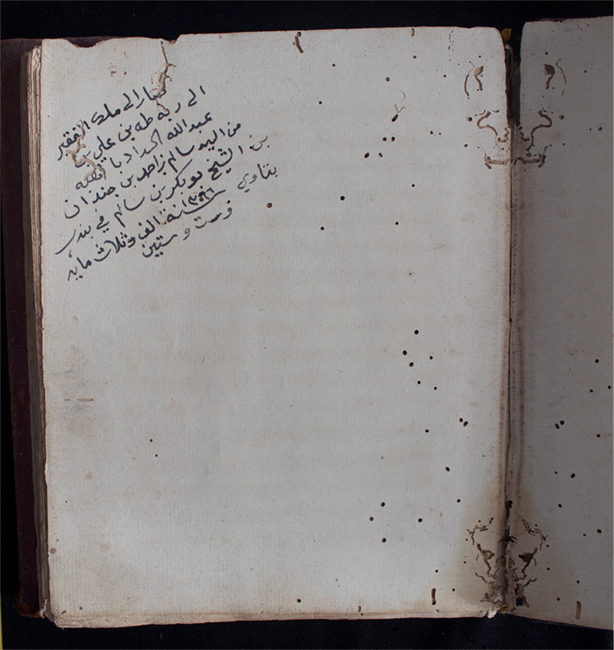

Fig. 5.2 Wiṣayāt Aḥmad b. Abī Bakr b. Sumayṭ ilā ʿAbd Allāh BāKathīr. Spiritual testament from the Zanzibari Sufi shaykh Aḥmad b. Sumayṭ (d. 1925) to his friend and disciple ʿAbd Allāh Bā Kathīr (d. 1925), dated 1337H/1918-1919. Possibly in the author’s own hand (EAP466/1/99, image 2), CC BY-ND.

Another example is EAP466/1/99 (Fig. 5.2). This is the “spiritual testament” of the leading Sufi and chief qāḍī of Zanzibar Aḥmad b. Sumayṭ to his close friend, disciple and associate, the Lamu-born scholar ʿAbd Allāh Bā Kathīr, who founded the Madrasa Bā Kathīr in Zanzibar and who maintained close family ties with Habib Saleh. Most likely, the manuscript is in the author’s own hand. Also by a local author is EAP466/1/144. This is a travelogue produced by the aforementioned ʿAbd Allāh Bā Kathīr, meticulously listing the shaykhs with whom he studied during his journey in Ḥaḍramawt in 1897. A final example is EAP466/1/60, authored by the Zanzibari scholar Ḥasan b. Muḥammad Jamal al-Layl (d. 1904), who came from the same family as Habib Saleh. The work, entitled Marsūmat al-ʿAyniyya, is a commentary on a well-known poem by the Ḥaḍramī ʿAlawī poet ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿAlawī al-Ḥaddād (d. 1719). While these are certainly important and merit an in-depth study, the focus here is on the mechanisms by which texts authored outside East Africa were made available there.

My first visit to the Riyadha was in April 2010. I then returned in July 2010, with colleagues from the University of Bergen and the University of Cape Town. Together with Aydaroos and Ahmad Badawi of the Riyadha, and Eirik Hovden from the University of Bergen, we made a preliminary inventory of the manuscript collection, simply numbering each manuscript in order from one upwards, and listing its title, author, copyist and date of copy only. In total, at that time we listed forty manuscripts. In August 2011, we received the Endangered Archives Programme (EAP) grant to digitise the collection; this task was completed in December 2012, and the digitised collection is accessible at the EAP website.13

The EAP website displays 144 individual items. In addition, twelve other manuscripts were partly digitised but they have not been put online, either because they were too fragile to be completely digitised, or because of errors during the digitising process. There is still no full catalogue of the collection. The handlists produced for the EAP project, as well as a provisional catalogue created for some categories of text (devotional texts, Sufism, genealogy and fiqh) forms the basis for this contribution. A future full catalogue will certainly add much depth to what is stated here, both in terms of the content of the works, as well as their transmission.

As has been argued elsewhere, the titles in the manuscript collection in the Riyadha Mosque show clear traces of the close intellectual inter-connection with the Ḥaḍramawt and with wider trends of Islamic thought that were spreading throughout the Indian Ocean during that period.14 This is especially clear if we look at the prevalence of texts that can be categorised as devotional, i.e. supererogatory prayers, Sufi dhikr (commemorations of God), mawlid texts, various types of invocations, prayers and poetry expressing devotion to the prophet. The collection shows a not unexpected over-representation of authors from within the Ḥaḍramī ʿAlawī tradition, or authors sanctioned by this tradition. This is especially so in the fields of Sufism and genealogy, where authors from the ʿAlawī tradition dominate.

Finally, it is worth noting that the Riyadha collection also holds multiple copies of texts that were common to all of East Africa, and indeed beyond to the wider Muslim world (such as the Qaṣīdat al-Burda and the Mawlid Barzanjī).15 From their presence in an educational institution, we can deduce that knowledge of these texts — literally, the ability to read them — was an essential prerequisite for being an educated member of contemporary Muslim society. There existed, in other words, what Roman Loimeier in his study of Zanzibar called an Arabic-language bildungskanon:16 an educational common ground that encompassed Ḥaḍramawt, Lamu, Zanzibar and the Comoro Islands. This canon was being taught in new educational facilities, such as the aforementioned al-Riyāḍ in Sayʾūn and the Madrasa Bā Kathīr in Zanzibar.

Before the emergence of print, this bildungskanon consisted mainly of manuscript texts that reached the Riyadha through buying, donations or copying over a long period of time — well into the era of print. Manuscripts were acquired during travel (to Ḥaḍramawt, Mecca, Egypt or elsewhere), either directly on behalf of the Riyadha, or by individuals who later decided to deposit their books with the institution, often through the Islamic institution of waqf. Buyers and donors, in other words, were important transmitters of ideas. Known texts were also copied by local copyists, who thus also acted as transmitters. The focus here is on the ways in which the manuscripts, as physical manifestations of an emerging bildungskanon, found their way to the shelves of the Riyadha.

Buyers, owners and donors

One illustrative example of how the actual, physical transmission of manuscripts took place can be found in the Riyadha library. Around 1890, the mufti of Tarīm, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Mashhūr, completed a massive genealogical work known as Shams al-Ẓahīra [The Mid-day Sun].17 Six years later, the Lamu-born scholar ʿAbd Allāh Bā Kathīr travelled to Tarīm in the search for knowledge. While in Tarim, he sought out al-Mashhūr and then wrote a letter to his colleague in Zanzibar, the aforementioned Ḥasan Jamal al-Layl (d. 1904). This letter is reproduced in the front of the text authored by Ḥasan Jamal al-Layl, the Marsūmat al-ʿAyniyya mentioned above, and which deals precisely with genealogy:

[Al-Mashhūr] greets you and gives you a big gift, but I don’t want to send it by somebody else’s hand, as it is very a precious book, but I will bring it myself after the Hajj [Pilgrimage]. What he composed is a book about all the sāda and the names they were known by…18

It is worth noting that Bā Kathīr emphasises the value of the book, not necessarily in monetary terms, but nonetheless as too precious to be sent by somebody else’s hand. The implication, of course, is that books were frequently sent “by somebody else’s hand” from Ḥaḍramawt and elsewhere to the scholarly centres of East Africa, including Lamu. The sending of texts back and forth seems to have been a common feature of intellectual friendships and collaborations; for example, Ṭāhir al-Amawī (d. 1938), qāḍī of Zanzibar, corresponded regularly with the mufti of Mecca. In this correspondence too, the sending of books, journal and texts is frequently mentioned.19

The text that Bā Kathīr brought to Zanzibar was almost certainly al-Mashhūr’s magnum opus, the Shams al-ẓahīra al-ḍāḥiyya al-munīra fī nasab wa-silsila ahl al-bayt al-nabawī [The Luminescent, encompassing mid-day sun on the lineage and genealogy of the people of the house of the Prophet].20 This work was only completed in manuscript form by 1890, and it is interesting to note how relatively quickly a copy made its way to East Africa. The Shams al-ẓahīra was since copied throughout the ʿAlawī diaspora, including in East Africa. One example is a copy held by the Riyadha Mosque, copied in Ṣafar 1322/April 1904 by Aḥmad b. Ṣāliḥ Jamal al-Layl (Ahmad Badawi, the son of Habib Saleh, b. 1305/1887-88).21

Owners affiliated with the Riyadha Mosque

Not surprisingly, we find among the original owners of manuscripts in the Riyadha collection the founder of the mosque itself, Habib Saleh. Three manuscripts carry his inscription (EAP466/1/17, 19, 28) while a fourth (EAP466/1/49) almost certainly belonged to him (by textual evidence, the text is a compilation of works by Habib Saleh’s shaykh, ʿAlī b. Muḥammad al-Ḥibshī). By all accounts, the manuscripts remained with the family, and were deposited at the Riyadha for safekeeping.

Another central Riyadha-affiliated scholar whose books can be found at the library was Sayyid Manṣab b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān. EAP466/1/48 is a collection of Sufi ijāzas (certificates, proof of proficiency) and spiritual advice from his main teacher in Ḥaḍramawt, ʿAydarūs b. ʿUmar al-Ḥibshī (d. 1896, Ḥaḍramawt). This collection stems from Sayyid Manṣab’s period of study with ʿAydarūs al-Ḥibshī, and almost certainly belonged to him. The series of Quranic juzus22 held in the Riyadha all carry his inscription, stating that the copy is “verified by Sayyid Manṣab”. According to the account by Abdallah Saleh Farsy, Sayyid Manṣab was known as the best Arabist in Lamu, and his “verification” meant that the vocalisation was correct and that the copy could be used for recital.

While it is not entirely clear from the inscription if the copies actually belonged to Sayyid Manṣab, they certainly came to the mosque via him. The same is the case with a copy of the Duʿa Birr Walidayn, a prayer often recited for one’s parents (EAP466/1/105). This copy bears Sayyid Manṣab’s comments and corrections in the margin, indicating that it may have belonged to him. The final inscription is almost unreadable, so another possibility is that Sayyid Manṣab was the copyist of the eight-page prayer. A final possibility, of course, is that Sayyid Manṣab corrected the work of another, unknown copyist.

The institution of waqf and the transmission of Islamic knowledge

The donation of books as waqf (pious endowment, permanently removing the item in question from circulation in the market) served as a way for the learned class to ensure that manuscripts and books remained within families or institutions.23 The Riyadha collection shows that waqf was used as a way to safeguard access to Islamic learning. One interesting example of waqf donation in the collection is in fact not a manuscript, but a lithograph printed in Cairo in 1272/1855. This is a gloss by the Egyptian scholar Muḥammad al-Khiḍr al-Dimyāṭī (1798-1870), completed by the author in 1250/1834, of the commentary by Ibn ʿAqīl on Ibn Mālik’s grammatical poem, the Alfiyya.

The Riyadha’s copy is one of the earliest printed versions of this book coming from Egypt, and hence one of the earliest printed versions overall.24 The inscriptions in the front of the book show the history of this particular copy. The oldest inscription says that the book was acquired by one Saʿīd Qāsim b. Saʿīd al-Maʿmarī in Rajab 1297/June 1880 and taken to Lamu by him. The Maʿmarī (Swahili: Maamri) family was (and is) a well-known Lamu family, originally of Omani origin, but long since part of the Sunni Muslim community of the region; they were known as traders and “pillars of the community”. The next thing we know is that the book was bought by one Saʿīd b. Rāshid from the estate of Muḥammad b. Qāsim al-Maʿmarī, most likely the brother of the first owner. Saʿid then made the book waqf for his son Nāsir to be used “as a fount for knowledge”.

How did Saʿīd Qāsim al- Maʿmarī obtain this book? It is possible that he bought it himself in Cairo, but Cairo was not part of the regular orbit of travelling trader-scholars from East Africa. Was it ordered from Cairo through middlemen and travellers – in other words “carried by somebody else’s hand”? Was it traded in Mecca or Ḥaḍramawt and procured during ḥajj or on a trading trip? Evidently, such questions cannot be answered with reference to a single manuscript or book, but this book demonstrates the important role played by individuals in procuring Islamic texts as well as the institution of waqf for safeguarding this knowledge for future generations. It seems clear that the book remained in the possession of the Maʿmarī family from 1880 until at least some time in the early twentieth century. Most likely, it was only deposited at the Riyadha some time after the 1903 foundation of the mosque itself.

Several other manuscripts in the Riyadha were donated as waqf (at least nine carry clear waqf inscriptions; EAP466/1/1, 2, 27, 35, 40, 43, 44, 66, 106). The earliest (EAP466/1/66) is a section of the Quran that was made waqf on 11 Rabīʿ al-Awwal 1268/3 January 1852 by Bwana Mshām (?) b. Abī Bakr b. Bwana Kawab (?) al-Lāmī for his daughter Khamisa. This, of course, was decades before the foundation of the Riyadha. However, being waqf, it was probably deposited at the Riyadha later, either for safekeeping or for use. The story is different for the 27-page long poem contained in EAP466/1/35. This was made waqf to the Riyadha directly in 1364/1945. The waqfiyya note tells us that the manuscript was “made waqf by ʿAbd al-Ḥabīb b. ʿAbd Allāh al-Yāfiʿī for the mosque of the quṭb (spiritual pole) Ṣāliḥ b. ʿAlawī b. ʿAbd Allāh Bā Ḥasan Jamal al-Layl”. The same ʿAbd al-Ḥabīb was also the copyist of the manuscript, having penned it eight years earlier (in Rajab 1356/September-October 1937).

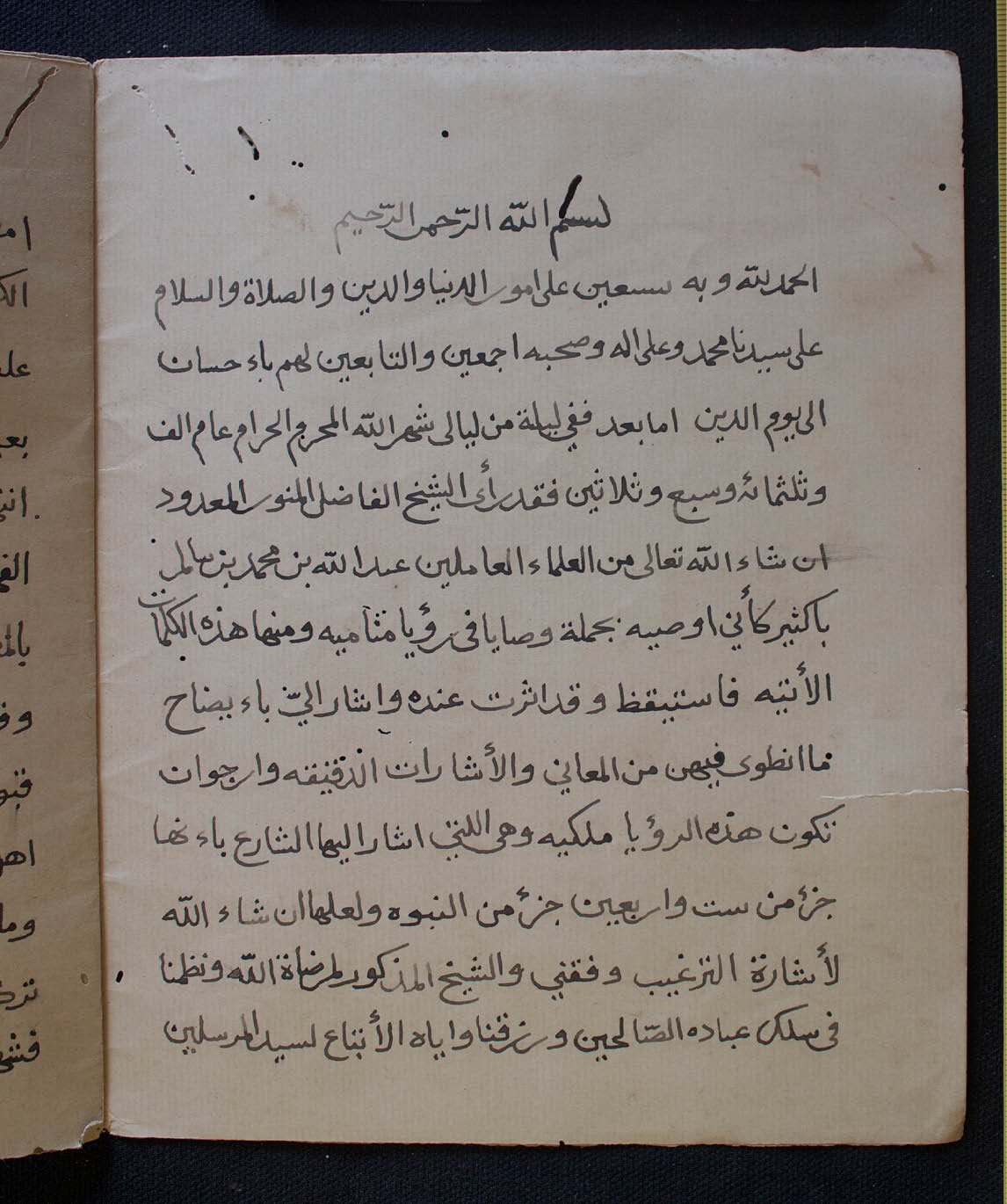

A final, charming example of waqf donation to the Riyadha is EAP466/1/106 (Fig. 5.3). This is a collection of prayers and dhikr, penned in a notebook in 1934, clearly for the purpose of aiding memory. On the front page, a hand that evidently was not skilled in Arabic calligraphy has written: “This book is waqf for all Muslims [of] God most high”. The word waqafa is misspelled, and rendered as wakafa. The same manuscript also carries an official stamp of the Riyadha, which curiously is not found in any other manuscripts (but generally in the printed works held by the institution).

Fig. 5.3 Example of late waqf donation “for the benefit of Muslims”.

Notebook with compilation of prayers and adhkār (Sufi texts for recitation)

(EAP/1/106, image 2), CC BY-ND.

Purchasing manuscripts abroad

As indicated above, many of the Riyadha manuscripts were not produced in Lamu, or even East Africa. Many carry the inscriptions of copyists whose names indicate origins in Ḥaḍramawt or Mecca, although this cannot be fully verified without a thorough analysis of paper, ink and script, and a comparative survey of copyists in Ḥaḍramawt and Mecca. Although little actual research has been produced on this phenomenon, we have many indications that texts in manuscript form circulated alongside other goods, and that scholars, traders and benefactors alike played a role as transmitters of Islamic knowledge. As has been demonstrated by Amal N. Ghazal, the Ibāḍīs of East Africa had access to text produced in Oman within a remarkably short period after production.25 General studies on the transmission of knowledge in the late nineteenth century indicate a pattern whereby manuscripts and books circulated along established trade routes.26

Among the manuscripts that made their way to the Riyadha, we also find a more surprising item: a Ḥanafī legal text.27 In a region where the overwhelming majority follow the Shāfʿī school of Islamic jurisprudence, we can assume that this text was not used for actual faṭwas (rulings), but rather for the intellectual study of law. The set of inscriptions on the manuscript demonstrate how texts of this type could be acquired. What we find is that the two first owners were evidently Meccan, which indicates that the manuscript itself was most likely produced in Mecca. The last owner given is Abū Bakr b. ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿUmar al-Shāṭirī, who was then residing in Mombasa. He adds: “I bought this book in Mecca for half a piaster (niṣf qirsh)”, thus providing us with an indication of what a manuscript of several hundred pages would fetch in Mecca in the late nineteenth century. The most likely conclusion is that Abū Bakr al-Shāṭirī bought the book for himself. However, interviewees also indicated that members of the Shāṭirī family in East Africa were known to act as philanthropists on behalf of the community, buying books during their travels and donating them to individual teachers, or mosques, like in this case, to the Riyadha.28

The Riyadha as a repository after the age of manuscripts

The first decades of the twentieth century saw the gradual shift from handwritten manuscripts to printed texts in the Middle East, India, Southeast Asia, and East Africa.29 In centres like Cairo, Beirut, Mecca, Hyderabad, Batavia (Jakarta) and Zanzibar, printing presses were being set up to print anything from small prayer leaflets to multi-volume legal tomes. The bildungskanon was gradually put into circulation in the form of books, and East African scholars were also seeing their own works take on printed form.30 That said, the Riyadha collection shows that the tradition of transmitting knowledge in manuscript form continued well into the 1930s and 40s, especially when it came to devotional texts to be recited. These were copied in lined, colonially produced notebooks, probably for memorisation (Fig. 5.3). More surprisingly, the Riyadha continued to acquire manuscripts at this point in time, now probably for the purposes of preservation rather than for direct usage. In other words, the Riyadha took on a function as an archive for the ʿAlawī tradition, as keepers of items of baraka (blessing, magic powers) and increasingly also of monetary value.

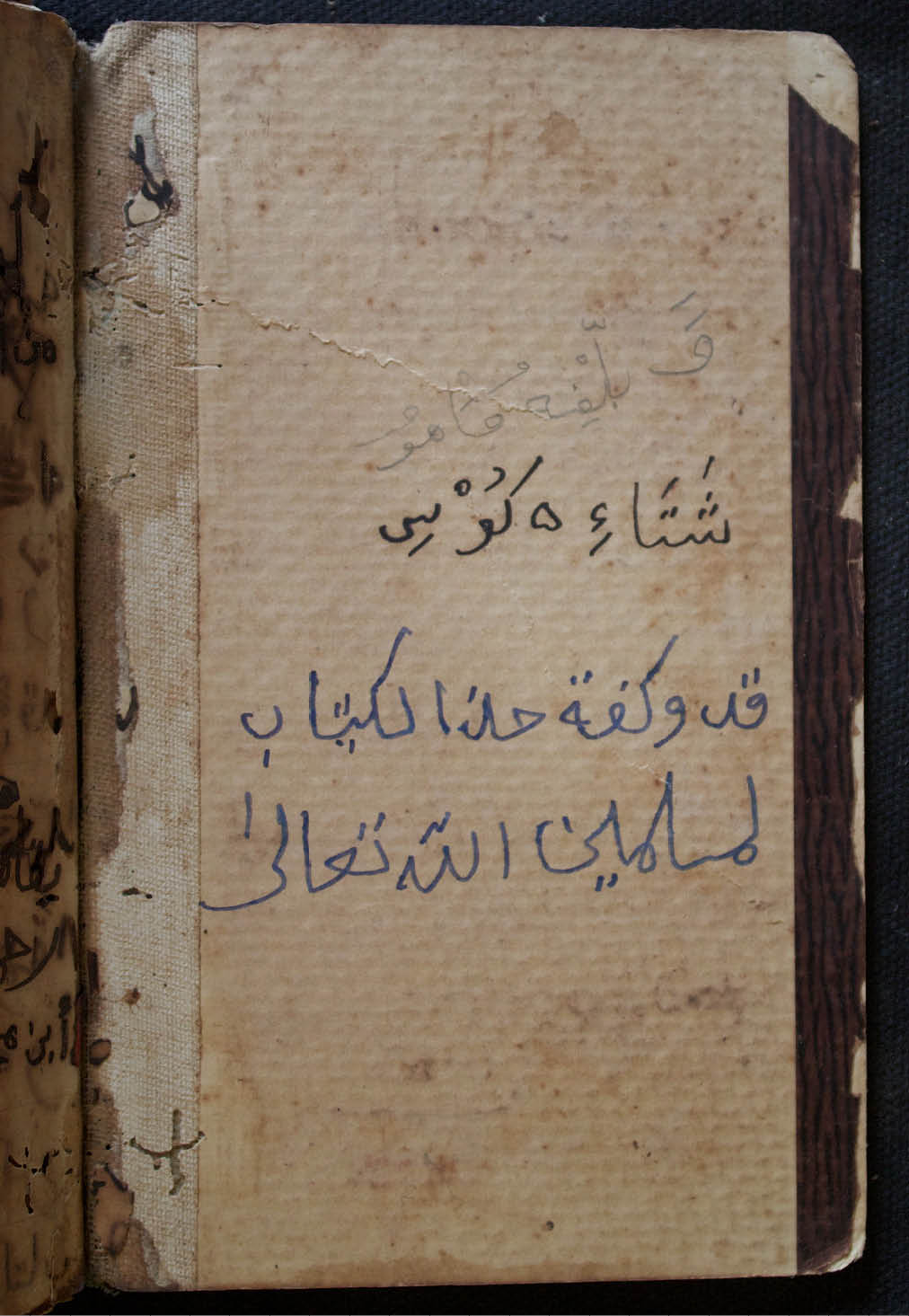

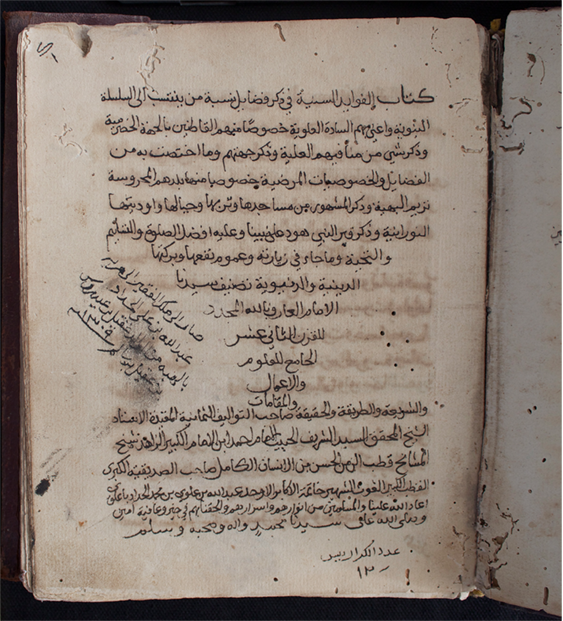

One example of the many different functions of a manuscript is EAP466/1/29 (Figs. 5.4 and 5.5). This work includes descriptions of Ḥaḍramawt, typically highlighting its many glorious mosques, scholars, books, and its learned tradition. As such, it is a classic ʿAlawī work, describing at length the “sublime benefits” of the homeland, forming precisely what Engseng Ho has called “travelling texts that formulate discourses of mobility”.31 It was completed in 1203/1788-89 by Aḥmad al-Ḥaddād who was the grandson of the famous Ḥaḍramī poet and religious teacher ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿAlawī al-Ḥaddād (d. 1719).

The copy in the Riyadha library was completed in 1253/1837-38 (i.e. some fifty years after it was first written) by Jaʿfar b. Muḥammad al-Ḥaddād. It is not clear whether the copying took place in Ḥaḍramawt itself or in some other location on the Indian Ocean rim; either scenario is equally likely. It has a fascinating set of inscriptions that shows the diasporic life of the book itself. The first inscription simply says that the copy was given away in 1309/1891-92 — in other words when the copy was almost fifty years old — by ʿAqīl b. ʿAydarūs b. ʿAqīl “as a gift” to ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿAlī al-Ḥaddād. A half-century later, in 1366/1946-47, it was given away again, indicating the long life these manuscripts had, being re-circulated as gifts, donated as waqf or passed on as inheritance. The inscription shows that the copy at this point was in Southeast Asia: “To Ṭāhā b. ʿAlī b. ʿAbd Allāh al-Ḥaddād Bā Faqīh from Shaykh Bū Bakr b. Sālim in Bandar Batawī [Batavia/Jakarta]”. Most likely, Ṭāhā b. ʿAlī was the one who brought the copy to East Africa, probably to Mombasa, from where it passed on to Lamu.

Fig. 5.4 Al-Fawāʾid al-Saniyya fī dhikr faḍāʾil man yantasibu ilā al-silsila al-nabawiyya [The Benefits of Remembering the Virtues of those Belonging to the Prophetic Lineage], by Aḥmad b. Ḥasan b. ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿAlawī, d. 1203/1788-1789 in Ḥaḍramawt. The inscriptions show the travelling of this particular manuscript, first given as a gift in 1891-1892 and then again in Batavia (Jakarta) in 1946-1947 (EAP466/1/29, image 4), CC BY-ND.

Fig. 5.5 Al-Fawāʾid al-Saniyya fī dhikr faḍāʾil man yantasibu ilā al-silsila al-nabawiyya, by Aḥmad b. Ḥasan b. ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿAlawī (d. 1203/1788-1789 in Ḥaḍramawt) (EAP466/1/29, image 6), CC BY-ND.

What is clear is that this particular copy reached East Africa some time in the latter half of the twentieth century, which shows that even at this late point – when printed and even audio Islamic material had long since arrived – manuscript copies were still circulating. The same pattern can be observed elsewhere in East Africa, notably in Zanzibar, where handwritten manuscripts were being made waqf for the Madrasa Bā Kathīr as late as the 1930s.32 In contrast to the Riyadha case, this waqf inscription specifies explicitly that the manuscript is to be used for “recitation”, the interpretation being that the volume is not yet a “collectors item” or deposited in the institution for safe-keeping. In other words, manuscripts could have extraordinary long lives, first as items for use, especially reference works and texts used for recitation. Then – even as print copies of the same text appeared – manuscripts were kept as items with special value (charisma or baraka), as a result of their author, copyist or possibly their previous owners.

By the late twentieth century, manuscripts may also have been circulated due to their monetary value.33 In some instances, there are indications that manuscripts were also taken care of for their value as cultural heritage, thus disassociating them entirely from their value as items of learning or holders of special baraka.34 A possible example of this is found in EAP466/1/40. This is an unidentified book of fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence) that carries the inscription: “This is the book of Khalfān b. Suwā, Bājūnī by tribe, Shāfiʿī of madhhab”. A second note states that “I received this book from the aforementioned”, signed by Muḥammad Bā Ḥasan b. ʿAlī b. Aḥmad Badawī Jamal al-Layl in Rajab 1369/April 1950, meaning that the manuscript came into the Jamal al-Layl family and thus the Riyadha collection, possibly as an item of heritage value. For the purpose of this discussion, however, it should be stated that although indications are that manuscripts were circulated and kept long after their “user value” had expired, we have too few examples and lack sufficient data to say anything conclusive about the motivation for donating or endowing these manuscripts as waqf.

From the two examples mentioned here, and with reference to the attached list of manuscripts, it is striking that books were owned and purchased both by ʿAlawī Ḥaḍramī families and their associates (al-Shāṭirī, al-Ahdal), and also by those whose names do not indicate any family link to the Ḥaḍramawt (al-Bājūnī). This, in turn, points to a more widely diffused pattern of text distribution, which can only be verified by an in-depth study of the originals.

The copyist as transmitter of Islamic knowledge

The origin of an individual manuscript can to some extent be deduced from the names of its copyist whose nisba (family) names are sometimes given. The Ḥaḍramī nisba is typically prefixed by the syllable Bā (such as Bā Kathīr, Bā Ṣafar), indicating tribal belonging. In addition, a set of family names such as Jamal al-Layl, al-Shāṭirī, Sumayṭ, al-Hibshī indicates that the person belongs to the sāda stratum. Of course, there were many copyists in East Africa too, who carried Ḥaḍrami names, and it is thus not possible to determine with certainty whether the copying actually took place in Ḥaḍramawt, East Africa, or elsewhere. Further research into the paper and ink, as well as a detailed analysis of script and handwriting is the best way to provide more in-depth knowledge about the origin of each individual manuscript. Furthermore, the nisba name of a copyist also indicates his origin, while in some cases the copyist himself has noted his place of residence or where the copying took place.

A total of 31 out of the 144 manuscripts can clearly be identified as being produced by a scribe in Lamu or East Africa, either because the name or place is actually given or because other circumstances indicate that copying took place in East Africa. This is, however, a very conservative figure. More specifically, there remains several twentieth-century notebook texts that have no scribe or copyist noted, but which are highly likely to have been copied in Lamu (and even in the Riyadha itself) and which may be identified through a comparison of handwriting and through interviews with older representatives of the Riyadha.

The majority of the Riyadha manuscripts that we can know for certain were copied locally derive from the twentieth century (only six date from the nineteenth century). That said, this should not be construed to mean that copying was not an activity undertaken by East African scholars in the nineteenth century and earlier. Their relative scarcity in the Riyadha collection is most likely due to the physical disintegration of the older manuscripts, which makes it difficult or impossible to identify the names of copyists, and the fact that much research is needed to determine the provenance of each manuscript. In the list below I have also included texts that are by known East African authors, on the assumption that they are most likely to have been copied locally. Furthermore I have assumed that the manuscripts which contain Swahili ajami (Swahili in the Arabic script) were penned by East African scribes. I am not qualified to make any identification (let alone analysis) of the Swahili manuscripts, but they are included in the attached provisional catalogue.

|

Name |

Riyadha MS |

Copied year |

|

|

1 |

Shārū b. Uthmān b. Abī Bakr (al-Sūmālī) |

EAP466/1/15 EAP466/1/030 |

1858 1840-42 |

|

2 |

Muḥammad b. Maṣʿūd al-Wārith or al-Wardī |

EAP466/1/2 EAP466/1/39 |

1860 1862 |

|

3 |

Muḥammad b. Shaykh b. ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Barāwī |

EAP466/1/60 |

1896 |

|

4 |

Muḥammad b. ʿUmar Maddi al-Shanjānī |

EAP466/1/144 |

1899 |

|

5 |

ʿAlī b. Nāṣir al-Mazrūʿī |

EAP466/1/49 |

1905-05 |

|

6 |

ʿAbd al-Ḥabīb b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Nāsir |

EAP466/1/10 EAP466/1/35 |

1906-07 1937 (?) |

|

7 |

ʿUmar b. Aḥmad b. Yunus al-Mafāzī, Pate |

EAP466/1/91 |

1915-16 |

|

8 |

Muḥammad b. ʿUthmān b. Faqīh b. Abī Bakr al-Bājūnī |

EAP466/1/34 |

1921-22 |

|

9 |

Sālim b. Yusallim b. ʿAwaḍ Bā Ṣafar |

EAP466/1/19 EAP466/1/28 EAP466/1/59 EAP466/1/76 EAP466/1/107 |

1927 1917-18 1934 1927 1929 |

|

10 |

Muḥammad b. Abī Bakr al-Bakrī Kijuma |

EAP466/1/58 |

1928 |

|

11 |

Aḥmad b. Saʿīd b. Sulaymān (“in Malindi”) |

EAP466/1/61 |

1932 |

|

12 |

Aḥmad b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Yūsuf (Maddi) |

EAP466/1/75 EAP466/1/81 EAP466/1/102 EAP466/1/103 |

1932-33 1932 1932 nd (?) |

|

13 |

ʿAbd Allāh b. Hamīd b. ʿAbd Allāh al-Shirāzī al-Qumrī |

EAP466/1/69 |

Between 1927 and c. 1930. |

|

14 |

ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Saʿīd b. Aḥmad, Lamu |

EAP466/1/65 |

Undated, twentieth century |

Without a proper comparison of handwriting and ink that can only be conducted on the original texts, this list gives only the cases where the copyist can be identified as East African by origin or residence, by name, as given in the text or from direct mention of where the text was copied. On this basis, fourteen East African (or East Africa-based) copyists can be identified in the Riyadha collection.

As in the case of ownership and purchase, we see in this list that scribes of diverse origin (Ḥaḍramī, Somali, Brawanese, Comorian — al-Qumrī meaning “The Comorian”) acted as copyists over a period of seventy years. It is also worth noting that the oldest locally produced manuscript was copied by a man of Somali origin (Shārū b. ʿUthmān al-Sūmālī, Fig. 5.6). In other words, knowledge of Arabic and Islamic text was relatively widely diffused in terms of ethnic background. More detailed research to identify hitherto unidentified copyists and their background, as well as their other roles in society, will undoubtedly give further nuance to this picture.

Fig. 5.6 Example of local copying in the nineteenth century. Alfyya [The One Thousand, verse of 1000 lines] with marginal commentary by Ibn ʿAqīl copied by Shārū b. ʿUthmān b. Abī Bakr b.ʿAlī al-Sūmālī in 1858 (EAP466/1/15, image 574), CC BY-ND.

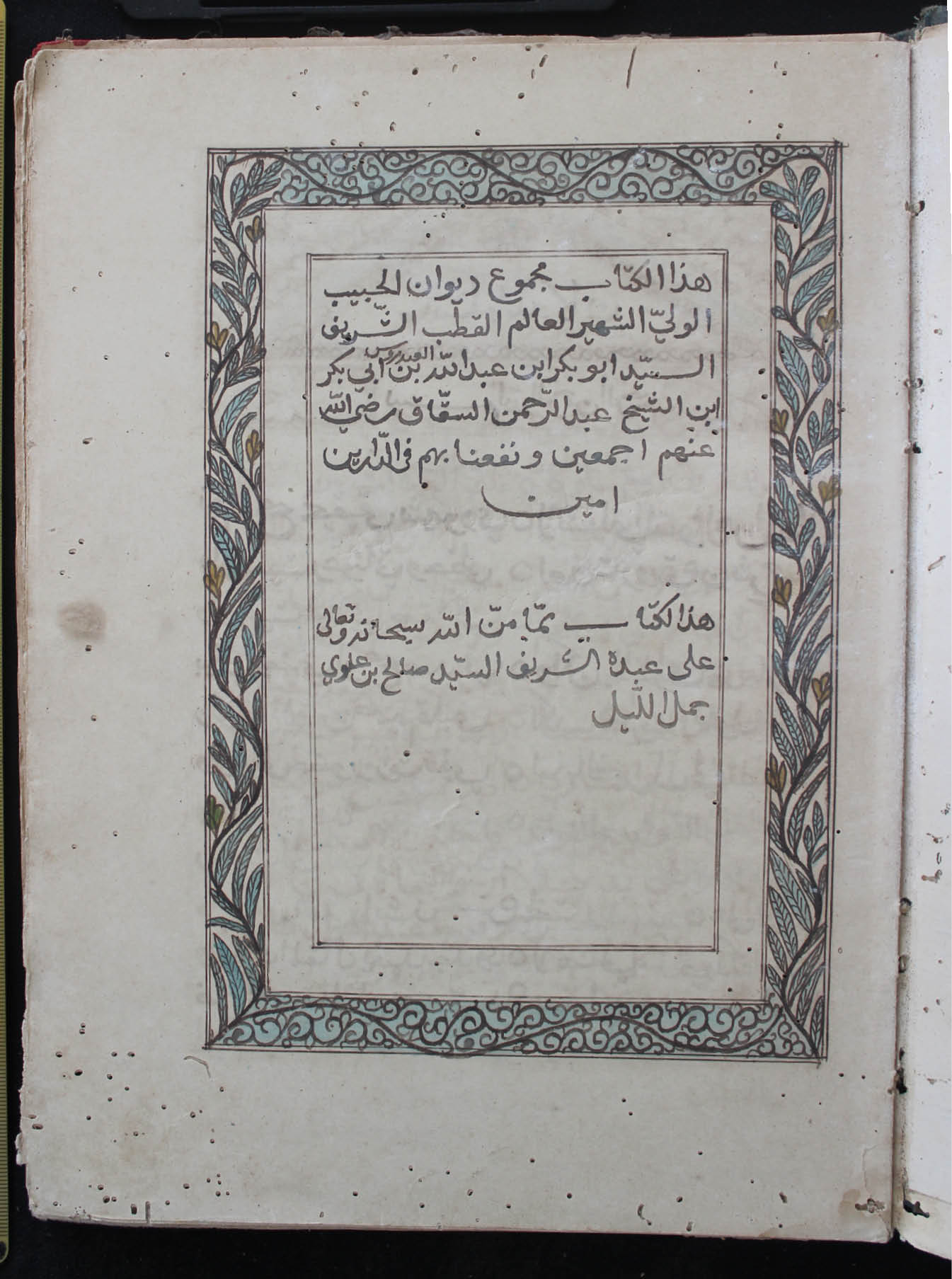

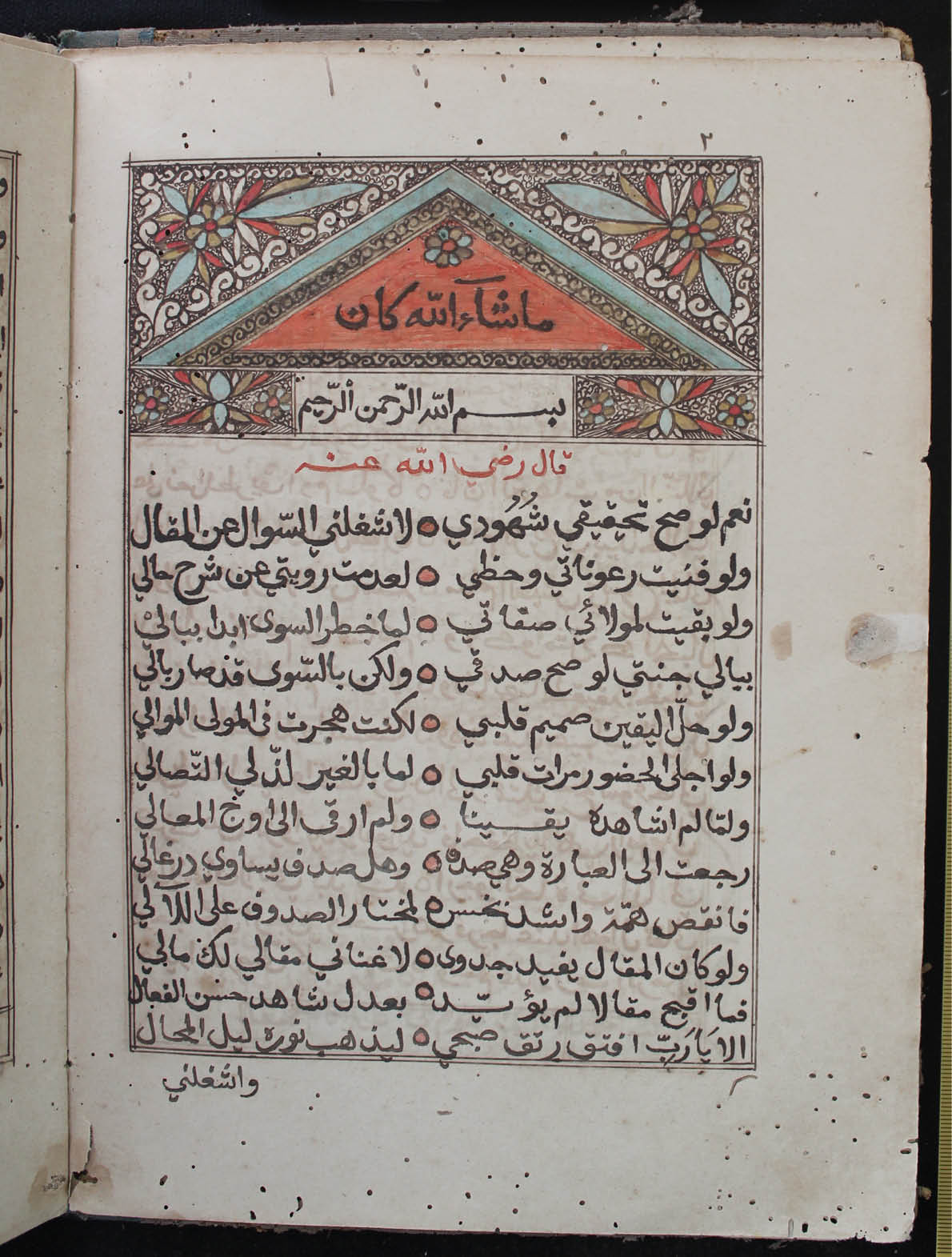

Twentieth century local copyists: modernity in handwriting

The scribe whose name appears most frequently in the Riyadha collection is Sālim b. ʿAwaḍ Bā Ṣafar, who stands as the copyist of five manuscripts. Although his name identifies him as a person of Ḥaḍramī family background, we can safely assume that he was a resident in East Africa, probably Lamu. This is because he also appears as the copyist of manuscripts in Swahili (ajami).35 Furthermore, Bā Ṣafar was a contemporary of, and clearly somewhat of a favourite copyist for Habib Saleh, having penned two of the manuscripts that we know belonged to him. Of special interest are the two copies of the poetry collection by the Ḥaḍramī ʿAlawī poet-saint, Abū Bakr al-ʿAydarūs (known as al-ʿAdanī), penned by Bā Ṣafar. In July 1927, he completed a 266-page copy of the text, and equipped his copy with an index whereby each poem was listed by page number — much in the same way as it is done in a printed book. It is not known if this copy made Habib Saleh commission yet another version of the same text. What we do know is that by November that same year, Bā Ṣafar had completed a new copy, with the same index system, this one running to 244 pages and with an illumination on the front page. This copy was owned by Habib Saleh, and it is likely that he commissioned it from Bā Ṣafar directly (Figs. 5.7 and 5.8).

The use of an index and pagination is a striking feature of the copies produced by Bā Ṣafar. This was the age when printed Arabic books were becoming widely circulated in East Africa, and it is not unlikely that Bā Ṣafar based himself on the “print model” rather than the traditional layout of Arabic poetry in manuscript form, whereby sequence is marked by a lead word at the end of each page.

|

Texts in the Riyadha collection copied by Sālim b. Yusallim b. ʿAwaḍ Bā Ṣafar |

||

|

EAP466/1/19 |

EAP466/1/28 |

EAP466/1/59 |

|

EAP477/1/76 |

EAP466/1/107 |

|

Fig. 5.7 Diwān al-ʿAdanī [The Collected Poetry of Abū Bakr al-ʿAdanī],

copied by Sālim b. Yusallim b. ʿAwaḍ Bā Ṣafar for Habib Saleh in 1927 [1]

(EAP466/1/19, image 2), CC BY-ND.

Fig. 5.8 Diwān al-ʿAdanī [The Collected Poetry of Abū Bakr al-ʿAdanī],

copied by Sālim b. Yusallim b. ʿAwaḍ Bā Ṣafar for Habib Saleh in 1927 [2]

(EAP466/1/19, image 3), CC BY-ND.

Another copyist — and another contemporary of Habib Saleh and Bā Ṣafar — was Aḥmad b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Yūsuf (al-Maddī: he sometimes uses the nisba name, sometimes not). He adhered to the same style as Bā Ṣafar, using pagination, and he even added a table of contents to some of the works. In the case of al-Maddī, we may even wonder why he made the copies. As the table below shows, he copied three texts in quick succession between June and August 1932 — the longest being 38 pages. The last copy was completed in October 1933, and is also a relatively short text (forty pages). We can speculate here that al-Maddī was commissioned to write these texts for use in the Riyadha education, which would indicate that they were not available in printed form. Another possibility, of course, is that Aḥmad himself was a student at the Riyadha and that the writing of these texts was part of his student work.

|

Texts in the Riyadha collection copied by Aḥmad b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Yūsuf (al-Maddī) |

||

|

EAP466/1/75 |

EAP466/1/81 |

EAP466/1/102 |

|

EAP466/1/103 |

|

|

The famous scribe, Muhammad Kijuma: EAP466/1/58

Although often assigned a role of anonymity as a name at the end of a long text, copyists and scribes could also be well-known public figures, either as exceptional calligraphers or as authors or artists in their own right. One such figure was Muhammad Kijuma (1855-1945), who stands as the copyist of EAP466/1/58 (Fig. 5.9).36 Kijuma was born in Lamu and received traditional Islamic education there. As a young man, he studied with his relative Sayyid Manṣab b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān, the man who donated part of his land for the foundation of the Riyadha Mosque and who “verified” Quran texts for recitation. Sayyid Manṣab, too, was known as en excellent calligrapher and – as mentioned above – a highly skilled Arabist.

Kijuma then turned to the somewhat dubious profession of a musician (at least as viewed by his strictly Islamic-observant mother), followed by an interest in carpentry, carving and art. It is worth noting that some of the less transgressive ngomas (songs with accompanying dance) were even incorporated into the public mawlid celebrations of the Riyadha, apparently sanctioned by Habib Saleh himself.37 The more expressive ones, however, were condemned outright as un-Islamic. In sum, Kijuma was a talented artist in many ways, and his later fame in Lamu is that of a somewhat controversial cultural icon: composer of songs, artist, carver and — not least — calligrapher. His lasting legacy is as a scribe of Swahili poetry into manuscript form in the Arabic script, mainly for European clients, and many of which have been kept in European collections. His poem on the act of writing has been quoted frequently by scholars of the Swahili poetic tradition. It emphasises the care taken by the scribe to make sure his writing “looks nice”:

Let me have black ink

And a reed pen

That I may write with it

Together with a good board

That I may mark lines with

That the writing looks nice

And be in a straight line38

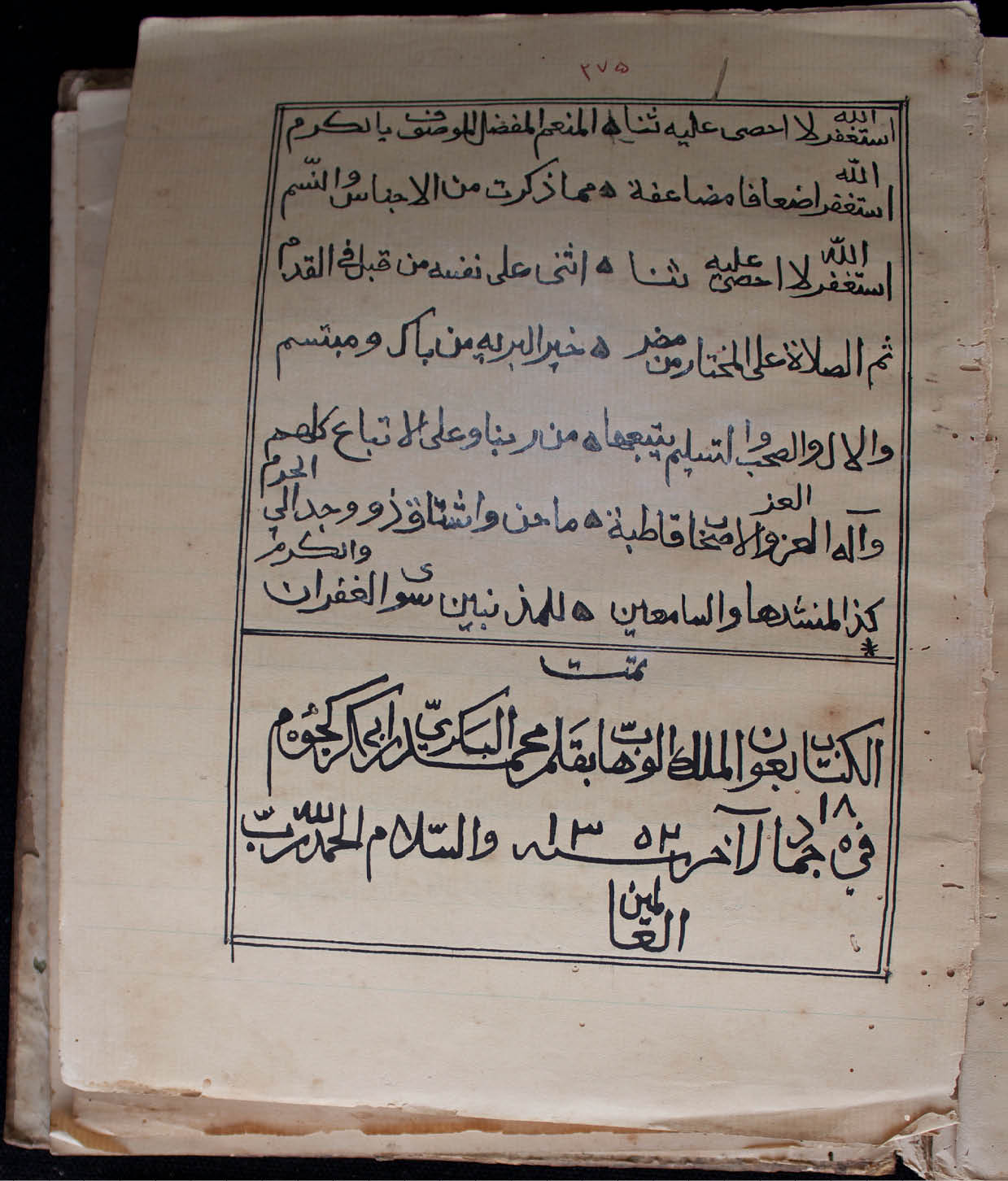

Fig. 5.9 Colophon showing the signature of copyist Muḥammad b. Abī Bakr al-Bakrī Kijūma and the date 18 Jumāda II 1352H/8 October 1928.

(EAP466/1/58, image 310), CC BY-ND.

Conclusion

The latter half of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth was the period when text-based Islam became widely diffused on the East African coast. The Riyadha Mosque in Lamu was part and parcel of this development, claiming authority based not only on the divine revelations (the Quran and the Sunna), but also in the wider corpus of Islamic texts. The impact of Ḥaḍramawt (Yemen) is very evident when it comes to the choice of texts. In total, these texts formed the basis for a new type of authority, beyond local hierarchies, that has been referred to as a reform. While Islamic scholars were at the forefront of this reform, important roles were also played by book-buyers, owners and individuals who endowed books as waqf for the purpose of their own family members or for “all Muslims”.

In the Riyadha, families of Ḥaḍramī origin seem to have played a particularly important role, possibly because of their relatively high socio-economic status, and because of their family connections with the Ḥaḍramawt (where, after all, the majority of texts originated). However, it is also clear that individuals of all backgrounds could decide to endow a particularly important manuscript, and that women also held this prerogative.

The copyist is another of the “silent” transmitters of Islamic knowledge. Although the evidence from the Riyadha remains inconclusive (a thorough analysis of paper, ink and script is needed, as well as a comparison between the handwriting of known authors and copyists), indications are that in the nineteenth and early twentieth century there existed an active class of scribes whose meticulous work made the Islamic scriptural tradition available to local scholars and students. In the twentieth century we see a new development closely linked to the emergence of educational institutions like the Riyadha. At this time, texts were copied in lined notebooks, clearly for educational purposes or for the purpose of memorising. The latter was particularly the case for the many devotional texts that were (and still are) central to ritual practice at the Riyadha.

References

Abou Egl, M. I., The Life and Works of Muhamadi Kijuma (Ph.D. thesis, University of London, 1983).

Anameric, Hakan, and Fatih Rukanci, “Libraries in the Middle East During the Ottoman Empire (1517-1918)”, Libri, 59 (2009), 145-154

Ayalon, Ami, “Private Publishing in the Nahḍa”, International Journal of Middle East Studies, 40:4 (2008), 561-77.

Badawī, Ṣāliḥ Muḥammad ʿAlī, Al-Riyāḍ bayna māḍīhi wa-ḥādirihi, Transcript, NP, 1410/1989.

Bang, Anne K., Sufis and Scholars of the Sea: Family Networks in East Africa, 1860-1925 (London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003).

—, “Another Scholar for all Seasons?: Tahir b. Abi Bakr al-Amawi (1877-1938), Qadi of Zanzibar”, in The Global Worlds of the Swahili. Interfaces of Islam, Identity and Space in 19th and 20th-Century East Africa, ed. by Roman Loimeier and Rüdiger Seesemann (Hamburg: LIT Verlag, 2006), pp. 273-88.

—, “Authority and Piety, Writing and Print: A Preliminary Study of Islamic Texts in Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century Zanzibar”, Africa, 81 (2011), 63-81.

—, “Zanzibari Islamic Knowledge Transmission Revisited: Loss, Lament, Legacy – and Transformation”, Social Dynamics, 38/3 (2012), 419-34.

—, “The Riyadha Mosque Manuscript Collection in Lamu: A Ḥaḍramī Tradition in Kenya”, Journal of Islamic Manuscripts, 5/4 (2014), 1-29.

—, Islamic Sufi Networks in the Western Indian Ocean (c. 1880-1940): Ripples of Reform (Leiden: Brill, 2014).

Farsy, Abdallah Saleh, Baadhi ya Wanavyoni wa Kishafii wa Mashariki ya Afrika [The Shafiʿi Ulama of East Africa, ca. 1830-1970: A Hagiographic Account], trans. and ed. by Randall L. Pouwels (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin, 1989).

Freitag, Ulrike, “Hadhramaut: A Religious Centre for the Northwestern Indian Ocean in the Late 19th and early 20th Centuries?”, Studia Islamica, 89 (1999), 165-83.

—, Indian Ocean Migrants and State Formation in Hadhramaut: Reforming the Homeland (Leiden: Brill, 2003).

Ghazal, Amal N., Islamic Reform and Arab Nationalism: Expanding the Crescent from the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean (1880s-1930s) (London: Routledge, 2010).

Green, Nile, “Journeymen, Middlemen: Travel, Transculture and Technology in the Origins of Muslim Printing”, International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, 41 (2009), 203-24.

Ho, Engseng, The Graves of Tarim: Genealogy and Mobility across the Indian Ocean (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2006).

Hoffman, Valerie J., “The Role of the Masharifu on the Swahili Coast in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries”, in Sayyids and Sharifs in Muslim Societies: The Living Links to the Prophet, ed. by Morimoto Kazuo (London: Routledge, 2012), pp. 185-97.

Katz, Marion Holmes, The Birth of the Prophet Muhammad: Devotional Piety in Sunni Islam (London: Routledge, 2007).

Khamis, Khamis S., “The Zanzibar National Archives”, in Islam in East Africa, New Sources: Archives, Manuscripts and Written Historical Sources, Oral History, Archaeology, ed. by Biancamaria Scaria Amoretti (Rome: Herder, 2001), pp. 17-25.

Kitamy, BinSumeit, “The Role of the Riyadha Mosque College in Enhancing Islamic Identity in Kenya”, in Islam in Kenya: Proceedings of the National Seminar on Contemporary Islam in Kenya, ed. by Mohamed Bakari and Saad S. Yahya (Nairobi: Mewa, 1995), pp. 269-76.

Krätli, Graziano, and Lydon, Ghislaine, eds., The Trans-Saharan Book Trade: Manuscript Culture, Arabic Literacy and Intellectual History in Muslim Africa (Leiden: Brill, 2011).

Lienhardt, Peter, “The Mosque College of Lamu and its Social Background”, Tanzania Notes and Records, 53 (1959), 228-42.

Loimeier, Roman, Between Social Skills and Marketable Skills: The Politics of Islamic Education in 20th Century Zanzibar (Leiden: Brill, 2009).

Martin, B. G., “Arab Migrations to East Africa in Medieval Times”, International Journal of African Historical Studies, 7/3 (1974), 367-90.

Al-Mashhūr, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Muḥammad b. Ḥusayn, Shams al-ẓahīra fī nasab ahl al-bayt min banī ʿAlawī. Furūʿ Fāṭima al-Zahrāʾ wa-Amīr al-Muʾminīn ʿAlī, 2 vols., 2nd edn., ed. by Muḥammad Ḍiyāʾ Shihāb (Jiddah: ʿĀlam al-Maʿrifa, 1984).

Mobini-Kesheh, Natalie, The Hadrami Awakening: Community and Identity in the Netherlands East Indies, 1900-1942 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999).

Noer, Deliar, The Muslim Modernist Movement in Indonesia, 1900-1942 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973).

Nuṣayr, ʿAyīda Ibrāhīm, Al-kutub al-ʿArabiyya allatī nushirat fī Misr fī ’l-Qarn al-tāsiʿ ʿashar (Cairo: The American University of Cairo Publications, 1990).

O’Fahey, Rex S., and Vikør, Knut S., “A Zanzibari Waqf of Books: The Library of the Mundhiri Family”, Sudanic Africa, 7 (1996), 4-23.

Padwick, Constance E., Muslim Devotions: A Study of Prayer-Manuals in Common Use (Oxford: Oneworld, 1996 [1961]).

Pedersen, Johannes, Den Arabiske Bog (Copenhagen: Fischer, 1946).

Plas, C. O. van der, “De Arabische Gemente Ontvaakt”, Koloniaal Tijdschrift, 20 (1931), 176-85.

Reese, Scott S., ed., The Transmission of Learning in Islamic Africa (Leiden: Brill, 2004).

—, Renewers of the Age: Holy Men and Social Discourse in Colonial Benaadir (Leiden: Brill, 2008).

Robinson, Francis, “Technology and Religious Change: Islam and the Impact of Print”, Modern Asian Studies, 27 (1993), 229-51.

Romero, Patricia W., “‘Where Have All the Slaves Gone?’: Emancipation and Post-Emancipation in Lamu, Kenya”, The Journal of African History, 27 (1986), 497-512.

Roper, Geoffrey, ed., World Survey of Islamic Manuscripts, 2 (London: Al-Furqān Islamic Heritage Foundation, 1993).

Sadgrove, Philip, “From Wādī Mīzāb to Unguja: Zanzibar’s Scholarly Links”, in The Transmission of Learning in Islamic Africa, ed. by Scott S. Reese (Leiden: Brill, 2004), pp. 184-211

Schrieke, Bertram, “De Strijd onder de Arabieren in Pers en Literatuur”, Notulen van de Algemeene en Directievergaderingen van het Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen, 58 (1920), 190-240.

Schulze, Reinhard, “The Birth of Tradition and Modernity in 18th and 19th Century Islamic Culture: The Case of Printing”, Culture and History, 16 (1997), 29-72.

Skovgaard-Pedersen, Jakob, ed., Culture and History (16) special issue: The Introduction of the Printing Press in the Middle East (Oslo: Scandinavian University Press, 1997).

Tolmacheva, Marina, ed. and trans., The Pate Chronicle (East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 1993).

Trimingham, J. Spencer, The Sufi Orders in Islam (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971).

el Zein, Abdul Hamid M., The Sacred Meadows: A Structural Analysis of Religious Symbolism in an East African Town (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1974).

Provisional catalogue entries for the Riyadha manuscripts referred to in this article39

EAP466/1/1

Unidentified work of fiqh.

Date of copy and copyist unknown.

Manuscript, Arabic, 215 pages.

Fiqh.

Waqfiyya note, folio 215.

EAP466/1/2

Title: Fatḥ al-qarīb al-mujīb aw qawl al-mukhtār fī sharḥ ghāyat al-iqtiṣār.

Author: Abī ʿAbd Allāh Shams al-Dīn Muḥammad b. Qāsim al-Ghāzzī al-Shāfiʿī, known as Ibn al-Gharābīlī, d. 918/1512.

Date of copy: 13 Ṣafar 1277/30 August 1860.

Copyist: Muḥammad b. Masʿūd al-Wārith (or al-Wardī) in Zanzibar (“naskhhā arḍ Zinjibār”).

Manuscript, Arabic, 225 pages.

Fiqh.

Note, folio 226: Waqfiyya note. Not clear if the waqf is made by or for Fāṭima bt. Ḥabīb b. Shayr (Shīr?) al-Wardī, who died 21 Dhū al-Ḥijja 1352/6 April 1934. The original bestowing seems to have been on 15 Jumāda I 1352/6 September 1933 by Shayr (Shīr) b. Muḥammad. Written by Muḥammad b. Masʿūd al-Wārith/al-Wardī (same as copyist).

EAP466/1/10

Title: Mawlid Dibāʾī.

Author: ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Dibāʾī (d. 1537).

Date of copy: 1324 H/1906-07.

Copyist: ʿAbd al-Ḥabīb b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Nāṣir.

Manuscript, Arabic, 46 pages.

Devotional. Poetic text for recitation on the occasion of mawlid.

Note: The identification of this copyist as local is based on the fact that the same person donated EAP466/1/35 as waqf. See below, EAP466/1/35.

EAP466/1/11

Title: Mawlid Barzanjī.

Author: Jaʿfar b. Ḥasan al-Barzanjī, d. 1764.

Date of copy: 13 Rajab 1313/30 December 1895

Copyist: Muḥammad b. Abī Bakr b. ʿUmar al-Bakrī.

Manuscript, Arabic, 29 pages.

Devotional. The most widely recited poem on the occasion of mawlid.

EAP466/1/15

Alfiyya with marginal commentary, Sharḥ Ibn ʿAqīl.

Author: Muḥammad b. ʿAbd Allāh Ibn Mālik (d. 1273) and ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Ibn ʿAqīl.

Date of copy: 30 Ṣafar 1283/16 July 1866

Copyist: ʿUthmān b. Ḥājj b. ʿUthmān b. Ḥājj b. Shayth (?) in Faza, Pate Island.

Manuscript, Arabic, 1283/1866, 567 pages.

Grammar, language.

EAP466/1/17

Unidentified.

Date of copy and copyist unknown.

Manuscript, Arabic, 342 pages.

Fiqh.

Note of ownership: Saleh b. Alawi Jamal al-Layl.

EAP466/1/19

Title: Kitāb majmū‘ diwān al-Ḥabīb al-‘Adanī.

Author: Abū Bakr b. ‘Abd Allāh al-‘Aydarūs, known as al-‘Adani, 1447-1508, Aden.

Date of copy: 11 Jumāda I 1356/6 November 1927.

Copyist: Sālim b. Yusallim b. ʿAwaḍ Bā Ṣafar.

Manuscript, Arabic, 244 pages. Paginated.

Note: A beautifully copied volume of the diwān of al-‘Adanī, made for Habib Saleh. The copy has an index listing the individual poems by page number.

EAP466/1/23

Title: Kitāb waṣiyyāt al-Jāmiʿa.

Author: ʿAbd Allāh b. Muḥsin b. ʿAlawī al-Saqqāf.

Date of copy: 1320/1902-03.

Copyist: ʿAbd al-Ḥabīb b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Nāṣir ʿAwaḍ al-ʿAfīf (?).

Manuscript, Arabic, 312 pages.

Sufism.

EAP466/1/24

Title: Al-Fatḥ al-Mubīn. Sharḥ snfās al-‘Aydarūs Fakhr al-Dīn.

Auhor: Abd al-Raḥmān b. Muṣṭafā b. Saykh al-‘Aydarus, d. 1778.

Date of copy: 1324/1906-07.

Copyist: Sulaymān b. Sālim al-Mazrūʿī.

Manuscript, Arabic, 456 pages.

EAP466/1/27

Title: Hāshiya ʿalā sharḥ Ibn ʿAqīl ʿalā Alfiyya ibn Mālik.

Author: Muḥammad al-Khiḍrī al-Dimyāṭī, d. 1870, Egypt. Commentary completed 1250/1834.

Litograph, Cairo, 1272/1855, 718 pages.

Grammar, language.

Waqfiyya note, folio 3.

EAP466/1/28

Title: Idāḥ al-asrār ʿulūm al-muqarribīn.

Author: Muḥammad b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Shaykh al-ʿAydarūs (d. 1621-22. Born and educated in Tarīm, died in Surat, India (?). Aḥmad b. Zayn al-Ḥibshī (?).

Date of copy: 1336/1917-18.

Copyist: Sālim b. Yusallim b. ʿAwaḍ Bā Ṣafar.

Manuscript, Arabic, 225 pages, paginated.

Time measurement/astronomy.

Note of ownership: Saleh b. Alawi Jamal al-Layl.

EAP466/1/29

Title: Al-Fawāʾid al-Saniyya fī dhikr faḍāʾil man yantasibu ilā al-silsila al-nabawiyya.

Author: Aḥmad b. Ḥasan b. ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿAlawī al-Ḥaddād, d. 1203/1788-89.

Unidentified text.

Date of copy: 1253/1837-38.

Copyist: Jaʿfar b. Muḥammad b. Jaʿfar b. Muḥammad b. ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿAlawī al-Ḥaddād.

Manuscript, Arabic, 244 pages.

Nasab/genealogy.

Note, folio 2-3: Several notes of ownership.

EAP466/1/34

Title: Ahl Badr.

Author: Unknown.

Date of copy: 1340 H/1921-22.

Copyist: Muḥammad b. Uthmān b. Faqīh b. Abī Bakr al-Bajūnī.

Manuscript, Arabic, 42 pages.

Devotional. Du‘ā’ for recitation upon completion of the names of the participants in the battle of Badr.

EAP466/1/35

Title: 2 poems in praise of the sāda ʿAlawiyya, various duʾāʾ for ʿAlawī saints.

Author: Unknown.

Date of copy: Rajab 1356/September 1937.

Copyist: ʿAbd al-Ḥabīb b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Nāṣir.

Devotional. Poetry.

EAP466/1/38

Title: Sharḥ Tarbiyyat al-aṭfāl.

Author: Muḥyī al-Dīn al-Qaḥṭānī, d. Zanzibar, 1869.

Copyist: Not given. Possibly in the author’s own hand (?).

Date: Not given. Mid/late nineteenth century by visual appearance.

Manuscript, Arabic with some text in Swahili ajami added at the end, 154 pages.

Grammar, language.

EAP466/1/40

Title: Unidentified.

Author: Unknown.

Date of copy and copyist: Unknown.

Manuscript, Arabic, 341 pages.

Fiqh.

Notes:

1) Book made waqf by Khaṭīb b. Daʿlān (?) al-Bājūnī (…) to the mosque of Barza b. Harān (Harūn??). No date.

2) Note of ownership: Khalfān b. Suwā al-Bājūnī by tribe, Shāfiʿī by madhhab.

Note of ownership: I received this book from the aforementioned. Muḥammad Bā Ḥasan b. ʿAlī b. al-Ḥabīb Aḥmad Badawī, Rajab 1349/Nov-Dec 1930.

EAP466/1/43

Title: Shifāʾ al-ṣudūr. Possibly: Shifāʾ al-Ṣuḍur fī ziyarāt al-mashāhid wa-‘l-qubūr.

Author: Marʿī b. Yūsuf al-Maqdisī, d. 1033/1623-2.

Manuscript, Arabic, 260 pages.

Sufism/fiqh. On grave visitation.

Note, Folio 2: Muḥammad b. Ṣāliḥ b. Ḥaydar bought this book from (…?) ʿUmar b. Yūsuf al-Lāmī in Ḥijja (?) 1277/June 1861 (Or: Ḥijja, 1377/June 1958. Most likely 1277).

Note, folio 7: Muḥammad b. Ṣāliḥ b. Ḥaydar bought this book “Shifāʾ al-Ṣuḍur” from ʿUmar b. Yūsuf al-[…] in Muḥarram 1277. Both are loose sheets, and it is possible that the first may have belonged to another book (?).

EAP466/1/44

Quran, from Sura 2 (al-Baqara).

Part of series of juzus, EAP466/1/44-45-46-47.

Manuscript, Arabic, 312 pages.

Illuminated frontispiece, black, red, yellow.

Note of ownership/waqf: Sayyid ʿAbd Allāh b. Salam (Yusallim?) b. ʿUmar owned this maṣḥaf and made it waqf for the Lahm (?) Mosque. No date.

EAP466/1/48

Title: Wiṣayāt wa-jamīʿāt al-ijāzāt ʿAydarūs b. ʿUmar al-Ḥibshī.

Author: ʿAydarūs b. ʿUmar al-Ḥibshī (d. 1896, Ḥaḍramawt).

Date of copy and copyist: Unknown.

Manuscript, Arabic, 121 pages

Sufism. A collection of ijāzas and advice by ʿAydarūs b. ʿUmar al-Ḥibshī .

Note: Inscriptions suggest the ownership of Sayyid Manṣab b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān.

EAP466/1/49

Title: Mukātabāt ʿAlī b. Muḥammad al-Ḥibshī.

Author: ʿAlī b. Muḥammad al-Ḥibshī (d. 1915, Ḥaḍramawt).

Date of copy: 1323 H/1905-06.

Copyist: More than one hand. Copyist 1:‘Alī b. Naṣr al-Mazrūʿī.

Manuscript, Arabic, 157 pages.

Sufism. A collection of writings by ʿAlī b. Muḥammad al-Ḥibshī.

EAP466/1/51

Several texts, including poetry, text on moon sighting, duʿāʿ, prayer to the prophet, etc.

Author: ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz b. ʿAbd al-Ghānī al-Amawī al-Barāwī, d. 1896, Zanzibar (folio 9 onwards to folio 40). Possibly also by his son, Burhān b. ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Amawī, d. 1935, Zanzibar (folio 33 onwards).

Poetry and a collection of duʿāt by Muḥyī al-Dīn al-Qaḥṭānī, d. Zanzibar, 1869 (folio 41-99), abyāt by al-Qaḥṭānī (folio 53 onwards), and a series of prayers/poetry by al-Qaḥṭānī.

Date of copy and copyist: Unknown.

Manuscript, Arabic, 98 pages.

Poetry, devotional, astronomy.

Note: Folio 1: Added text in a different hand, ʿAlī b. ʿAbd Allāh al-Mazrūʿī, possibly ʿAlī b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Yāfiʿ al-Mazrūʿī, d. 1894 in Mombasa.

EAP466/1/58

Title: Miscellaneous devotional texts.

Author: Several authors.

Date of copy: 1347/1928.

Copyist: Muḥammad b. Abī Bakr al-Bakrī Kijūma.

Manuscript, Arabic, 314 pages.

Devotional. Collection of aḏkār and duʿāt.

EAP466/1/59

Title: Majmūʿ al-laṭāʾif al-ʿarshiyya.

Author: ʿAydarūs b. ʿUmar al-Ḥibshī.

Date of copy: 1353/1934.

Copyist: Sālim b. Yusallim b. ʿAwaḍ Bā Ṣafar.

Manuscript, Arabic, 129 pages. Paginated.

Sufism.

EAP466/1/60

Title: Marsūmat al-ʿayniyya.

Author: Ḥasan b. Muḥammad b. Ḥasan Jamal al-Layl, d. 1904, Zanzibar.

Date of copy: 14 Rabīʿ I 1314/14 August 1896.

Copyist: Muḥammad b. Shaykh b. ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Barāwī.

Manuscript, Arabic, 62 pages.

Genealogy, Sufism. Commentary on the Al-Qaṣīda al-‘Ayniyya by al-Ḥaddād (d. 1719, Ḥaḍramawt). A two-page preface in another hand, a letter from ‘Abd Allāh Bā Kaṯhīr to the author.

EAP466/1/61

1) Title: Taḫmīs ʿalā qaṣīdat al-mudhariyya li-al-imām al-Buṣīrī.

Author: ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿAlawī al-Ḥaddād (d. 1719, Ḥaḍramawt).

2) Title: Jāliyat al-qadr bi-asmāʾ ahl al-Badr.

Author: Jaʿfar al-Barzanjī (d. 1765, Medina).

Date of copy: 7 Jumāda II 1351/1932

Copyist: Aḥmad b. Saʿīd b. Sulaymān, in “jihat Sawāḥilī, fī Bandar Malindi”.

Manuscript, Arabic, 37 pages.

Devotional.

EAP466/1/63

Title: Qurʾat al-anbiyāʾ.

Author: Unknown.

Date of copy and copyist: Unknown.

Manuscript, Swahili ajami with some Arabic, 29 pages.

Fortune-telling, based on the names of the prophets, possibly a translation into Swahili from an Arabic original.

EAP466/1/65

Title: Iḥdā ‘ashariyya.

Author: Aḥmad b. Muḥammad al-Miḥḍār, d. 1304/1886-87, Ḥaḍramawt.

Date of copy: Undated. Twenthieth century by visual appearance.

Copyist: ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Saʿīd b. Aḥmad, “resident in Lamu”.

Manuscript, Arabic, 42 pages.

Devotional. Poetic text recited on the 11th of every month.

EAP466/1/66

Quran, juz 11.

Date of copy and copyist: Unknown

Manuscript, Arabic, 56 pages.

Note, folio 2: Made waqf by Qāḍī Hishām b. Abī Bakr b. Bwana Kawb (or: Kūb) al-Lāmī for his daughter Khamīsa and her children, 11 Rabīʿ I 1261/20 March 1845. Written by Muḥammad b. ʿAlī al-Lāmī by his own hand.

EAP466/1/69

Title: Khuṭbas of ʿAlī b. Muḥammad al-Ḥibshī, and various ijāzas and waṣiyya (spiritual advice) including from ʿAydarūs b. ʿUmar al-Ḥibshī to Sayyid Manṣab b. ʿAbd al-Raḥman.

Author: ʿAlī b. Muḥammad al-Ḥibshī et al.

Date of Copy: At different points between March 1927 and January 1930.

Copyist: ʿAbd Allāh b. Ḥamīd b. ʿAbd Allāh al-Shirāzī al-Qumrī.

Manuscript, Arabic, 267 pages.

Sufism.

EAP466/1/75

Collection of texts: Majmūʿ al-mutun:

1. Jawāhir al-tawḥīd, by Ibrāhīm al-Bājūrī.

2. Badʾ al-amālī, matn al-Kharīda.

3. Al-kharīda, by Aḥmad al-Dardīr.

Copyist: Aḥmad b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Yūsuf Maddi.

Date of copy: 1351/1932-33.

Manuscript, Arabic, 19 pages

EAP466/1/76

Title: Diwān al-Ḥabīb Abū Bakr b. ‘Abd Allāh b. ‘Aydarūs al-‘Adanī.

Author: Abū Bakr b. ‘Abd Allāh b. ‘Aydarūs, known as al-‘Adanī, d. Aden, 1508.

Date of copy: 6 Muḥarram 1346/6 July 1927.

Copyist: Sālim b. Yusallim b. ʿAwaḍ Bā Ṣafar.

Manuscript, Arabic, 266 pages. Paginated.

Poetry, Sufism.

EAP466/1/81

Title: Compilation of devotional texts.

Author: Multiple authors.

Date of copy: 27 Muḥarram 1351/2 June 1932

Copyist: Aḥmad b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Yūsuf (al-Maddī).

Manuscript, Arabic, 38 pages. Paginated. In lined notebook with a table of contents at front.

EAP466/1/83

Title: Unidentified sharḥ on a qaṣīda on tawḥīd by ʿAbd al-Ġānī al-Nabulsī (d. 1731).

Author: Possibly Aḥmad b. Abī Bakr b. Sumayṭ’s text entitled Mātālib al-Sunniya.

Date of copy: Unknown. Twentieth century by visual appearance.

Copyist: Unknown, looks like same copyist as that of EAP466/1/144 (Riḥlat al-Ashwāq).

Manuscript, Arabic, 16 pages.

Tawḥīd (?).

Note: The copy is incomplete.

EAP466/1/91

Title: Ṭayyib al-asmā’ al-mubāraka.

Author: Unknown.

Date of copy: 1334 H/1915-16.

Copyist: ʿUmar b. Aḥmad b. Yunus al-Mafāzī, resident in Siyu (Pate).

Manuscript, Arabic, 36 pages.

Devotional text based on the names of God.

Notes of ownership: Muhammad b. Salim b. Hamid al-Khawasini. 2. Alawi b. Muhammad b. Ahmad Badawi.

EAP466/1/96

Title: Dini ni ngome.

Author: Unknown.

Date of copy and copyist: Unknown.

Manuscript, Swahili ajami, 9 pages.

EAP466/1/99

Title: Wiṣayāt Aḥmad b. Abī Bakr b. Sumayṭ ilā ʿAbd Allāh BāKathīr.

Author: Aḥmad b. Abī Bakr b. Sumayṭ (d. 1925, Zanzibar).

Date of copy: 1337/1918-19.

Copyist: Possibly autograph copy (or ʿAbd Allāh Bā Kathīr?). Possibly same copyist as EAP466/1/144.

Manuscript, Arabic, 11 pages.

Sufism. Sufi advice/ legacy from Aḥmad b. Sumayṭ (d. 1925, Zanzibar) to his colleague and disciple, ʿAbd Allāh BāKathīr (d. 1925, Zanzibar).

EAP466/1/102

Title: Matn al-Bājūrī waʾ-nafs.

Author: Ibrāhīm al-Bājūrī, d. 1277/1860 (Shaykh al-Azhar).

Date of copy: 2 Ṣafar 1351/7 June 1932.

Copyist: Aḥmad b. ʿAbd Allāh (al-Maddī).

Manuscript, Arabic, 24 pages. Paginated. In lined notebook.

Tawḥīd.

EAP466/1/103

Title: Mulḥat al-iʿrāb.

Author: Abū Muḥammad al-Qāsim b. ʿAlī al-Ḥarīrī.

Date of copy: 7 Rajab 1352/27 October 1933 (both H and CE date are given)

Copyist: Aḥmad b. ʿAbd Allāh (al-Maddī).

Manuscript, Arabic, 40 pages. Paginated. In lined notebook.

Grammar, language.

EAP466/1/105

Title: Duʿāʾ birr walidayn.

Author: Muḥammad b. Aḥmad b. Abī al-Ḥubb al-Ḥaḍramī (d. 611/1214-15, Ḥaḍramawt).

Date of copy: 1334 H/1915-16.

Copyist: Unknown. Possibly Sayyid Manṣab b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān.

Manuscript, Arabic, 8 pages.

The copy most likely belonged to Sayyid Manṣab b. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān. It bears his corrections in the margins.

EAP466/1/106

Title: Kitāb jāmiʿ al-aḏkār.

Author: Multiple authors.

Date of copy: 1353/1934.

Copyist: Unknown.

Manuscript, Arabic and Swahili, 144 pages.

Devotional/Sufism. Notebook with a collection of ḏikr and prayers for the prophet. Some of the prayers have additional commentary in Swahili in Arabic script.Waqfiyya note, folio 1.

EAP466/1/107

Title: Nafḥ al-misk al-maftūt min akhbār wādī Ḥaḍramawt.

Author: ‘Alī b. Aḥmad b. Ḥasan b. ‘Abd Allāh al-‘Aṭṭas.

Date of copy: 24 Ḏū ‘l-Qi‘da 1347/4 May 1929.

Copyist: Sālim b. Yusallim b. ʿAwaḍ Bā Ṣafar.

Manuscript, Arabic, 25 pages. Paginated.

Genealogy. A history of the genealogical lines of the sāda and qabā’il (tribes) of Ḥaḍramawt.

EAP466/1/111

Title: Misc. devotional texts.

Author: Multiple authors.

Date of copy: 12 Rabīʿ 11342/23 Oct 1923.

Copyist: Wālī b. Abī Bakr b. Muḥammad al-Barāwī.

Manuscript, Arabic, 37 pages.

EAP466/1/144

Title: Riḥlat al-ashwāq al-qāwiyya ilā diyār al-sāda al-‘alawiyya.

Author: ʿAbd Allāh BāKathīr, d. Zanzibar 1925.

Date of copy: 27 Jumāda II 1317/1 November 1899.

Copyist: Muḥammad b. ʿUmar b. Maddi al-Shinjanī.

Travelogue from the journey in Ḥaḍramawt.

1 The transliteration of Arabic words in this chapter is based on the LOC transliteration system.

2 The honorific use of the term ḥabīb (beloved) is common to many of the most revered scholars of the ʿAlawī tradition up to the present time; for example, “Habīb ʿUmar” (ʿUmar b. Hafīẓ) is the current leader of the Dar al-Muṣṭafā in Tarim, Ḥaḍramawt. In some instances, the term ḥabīb is used almost synonymously with the term sharīf or sayyid, implying descent from the prophet. Abdallah Saleh Farsy, in his hagiographic account of the Islamic scholars of East Africa, uses the name “Habib Saleh” consistently. See Abdallah Saleh Farsy, Baadhi ya Wanavyoni wa Kishafii wa Mashariki ya Afrika [The Shafi’i Ulama of East Africa, ca. 1830-1970: A Hagiographic Account], trans. and ed. by Randall L. Pouwels (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin, 1989).

3 Anne K. Bang, Sufis and Scholars of the Sea: Family Networks in East Africa, 1860-1925 (London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003), pp. 13-16; and J. Spencer Trimingham, The Sufi Orders in Islam (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971), p. 16. Trimingham bases his observation on Maghrebi sources deriving from the Shādhiliyya-Jazūliyya.

4 Ṣāliḥ Muḥammad ʿAlī Badawī, Al-Riyāḍ bayna māḍīhi wa-ḥādirihi, Transcript, NP, 1410/1989; Abdul Hamid M. el Zein, The Sacred Meadows: A Structural Analysis of Religious Symbolism in an East African Town (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1974); Peter Lienhardt, “The Mosque College of Lamu and its Social Background”, Tanzania Notes and Records, 53 (1959), 228-42; BinSumeit Kitamy, “The Role of the Riyadha Mosque College in Enhancing Islamic Identity in Kenya”, in Islam in Kenya: Proceedings of the National Seminar on Contemporary Islam in Kenya, ed. by Mohamed Bakari and Saad S. Yahya (Nairobi: Mewa, 1995), pp. 269-76; and Patricia W. Romero, “‘Where Have All the Slaves Gone?’: Emancipation and Post-Emancipation in Lamu, Kenya”, The Journal of African History, 27 (1986), 497-512.

5 In Swahili, the name is usually referred to as “al-Hibshi”, whereas the Ḥaḍramī vocalisation is given as “al-Ḥabshī”. I have chosen here to use the most common Swahili vocalisation. On the history of ʿAlī b. Muḥammad al-Ḥibshī , see Freitag, Ulrike, “Hadhramaut: A Religious Centre for the Northwestern Indian Ocean in the Late 19th and early 20th Centuries?”, Studia Islamica, 89 (1999), 165-83; and Bang, Sufis and Scholars, pp. 63-68. On the relationship between Habib Saleh and ʿAlī al-Ḥibshī, see Badawī: “there existed between [the two] a strong bond and connection, even though the two never met in their lives” (p. 24).

6 In Indonesia, the emergence of new strands of education among the Ḥaḍramīs caused a deep conflict between “traditionalists” and “modernists”. For the development of new teaching institutions, see Ulrike Freitag, Indian Ocean Migrants and State Formation in Hadhramaut: Reforming the Homeland (Leiden: Brill, 2003); Natalie Mobini-Kesheh, The Hadrami Awakening: Community and Identity in the Netherlands East Indies, 1900-1942 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999); Muḥammad Nūr b. Muḥammad Khayr al-Anṣarī, Taʾrīkh al-Irshād; and Deliar Noer, The Muslim Modernist Movement in Indonesia, 1900-1942 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973). For two contemporary Dutch accounts of the conflict, see B. J. O. Schrieke, “De Strijd onder de Arabieren in Pers en Literatuur”, Notulen van de Algemeene en Directievergaderingen van het Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen, 58 (1920), 190-240; and C. O. van der Plas, “De Arabische Gemente Ontvaakt”, Koloniaal Tijdschrift, 20 (1931), 176-85.

7 The works of al-Ḥibshī can be found in EAP466/1/49, EAP466/1/52, EAP466/1/69. For more detailed description, see the bibliography below.

8 Badawī, p. 17; Farsy, pp. 66-68; and Bang, Sufis and Scholars, p. 102.

9 Waqfiyya dated 1320/1903 (both years are actually given in the waqfiyya), and stamped by the East Africa Protectorate Lamu Registry, 21 Feb 1903: In the possession of the Riyadha Mosque.

10 This is also the conclusion arrived at by Peter Lienhardt, “The Mosque College of Lamu and its Social Background”, Tanzania Notes and Records, 53 (1959), 228-42 (p. 230).

11 Patricia W. Romero, “‘Where Have All the Slaves Gone?’: Emancipation and Post-Emancipation in Lamu, Kenya”, The Journal of African History, 27 (1986), 497-512.

12 The texts that include Swahili ajami have been included below in the list of works by local copyists (EAP466/1/38).

13 EAP466: The manuscripts of the Riyadh Mosque of Lamu, Kenya, http://eap.bl.uk/database/overview_project.a4d?projID=EAP466. The digitised manuscripts are available at http://eap.bl.uk/database/results.a4d?projID=EAP466

14 For the content of this intellectual tradition, see Anne K. Bang, “The Riyadha Mosque Manuscript Collection in Lamu: A Ḥaḍramī Tradition in Kenya”, Journal of Islamic Manuscripts, 5/4 (2014); and idem, Islamic Sufi Networks in the Western Indian Ocean (c. 1880-1940): Ripples of Reform (Leiden: Brill, 2014).

15 Qaṣīdat al-Burda, by the Sufi and poet al-Buṣīri (d. 1202) is a poetic praise of the Prophet Muḥammad and widely recited among Sunni Muslims throughout the world. The mawlid poem authored by Jaʿfar al-Barzanjī (d. 1764) is a panegyric on the Prophet, widely recited in the Islamic world on the date of his birth. See Marion Holmes Katz, The Birth of the Prophet Muhammad: Devotional Piety in Sunni Islam (London: Routledge, 2007); and Constance E. Padwick, Muslim Devotions: A Study of Prayer-Manuals in Common Use (Oxford: Oneworld, 1996 [1961]).

16 Roman Loimeier, Between Social Skills and Marketable Skills: The Politics of Islamic Education in 20th Century Zanzibar (Leiden: Brill, 2009).

17 ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Muḥammad b. Ḥusayn Al-Mashhūr, Shams al-ẓahīra fī nasab ahl al-bayt min banī ʿAlawī. Furūʿ Fāṭima al-Zahrāʾ wa-Amīr al-Muʾminīn ʿAlī, 2 vols., 2nd edn., ed. by Muḥammad Ḍiyāʾ Shihāb, Jiddah (Beirut: ʿĀlam al-Maʿrifa, 1984). Al-Mashūr himself was a representative of the reformist movement discussed above, and the founder of a school in Tarim that was sought out by scholars from East Africa and beyond.

18 Another, related text by Ḥasan b. Muḥammad Jamal al-Layl can be found in the Zanzibar National Archives, ZA 8/58 (photocopy in Bergen). For a discussion of this text, see Valerie J. Hoffman, “The Role of the Masharifu on the Swahili Coast in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries”, in Sayyids and Sharifs in Muslim Societies: The Living Links to the Prophet, ed. by Morimoto Kazuo (London: Routledge, 2012), pp. 185-97.

19 For a discussion of this correspondence, see Anne K. Bang, “Another Scholar for all Seasons?: Tahir b. Abi Bakr al-Amawi (1877-1938), Qadi of Zanzibar”, in The Global Worlds of the Swahili. Interfaces of Islam, Identity and Space in 19th and 20th-Century East Africa, ed. by Roman Loimeier and Rüdiger Seesemann (Hamburg: LIT Verlag, 2006), pp. 273-88.

20 See al-Mashhūr. The book was first printed in Hyderabad in 1911, and again in Mecca in 1955. The latest edition, from 1984 (which is the one consulted here) has additional entries and updates. For a discussion of its content, see B. G. Martin, “Arab Migrations to East Africa in Medieval Times”, International Journal of African Historical Studies, 7/3 (1974), 367-90. For a discussion of its diffusion and meaning within the ʿAlawī diaspora, see Engseng Ho, The Graves of Tarim: Genealogy and Mobility across the Indian Ocean (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2006).

21 This manuscript is not on the EAP website as it was insufficiently digitised (not all pages could be opened). In the initial listing by Shaykh Ahmad Nabhany, it was assigned the number RM30. It is stored in the Riyadha library.

22 For the purpose of reciting and learning the Quran by heart, the text is often divided into thirty sections (Ar: juzʾ, Swahili: juzu). These do not correspond to the chapters of the Quran, as breaks are inserted in order to make the sections of even length. EAP466/1/118 – 43 are individual manuscripts where each juz is bound separately.

23 The use of waqf to establish and expand libraries was a well-known practice in the Ottoman Middle East. See Hakan Anameric and Fatih Rukanci, “Libraries in the Middle East During the Ottoman Empire (1517-1918)”, Libri, 59 (2009), 145-54. For a discussion concerning waqf endowment of books in Zanzibar, see Anne K. Bang, “Authority and Piety, Writing and Print: A Preliminary Study of Islamic Texts in Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century Zanzibar”, Africa, 81 (2011), 63-81.

24 ʿAyīda Ibrāhīm Nuṣayr, Al-kutub al-‘Arabiyya allatī nushirat fī Misr fī ’l-Qarn al-tāsi‘ ‘ashar (Cairo: The American University of Cairo Publications, 1990), p. 148. The overview by Nuṣayr lists only three editions printed in 1272H, and no earlier edition. However, it also shows that the gloss by al-Dimyāṭī was printed repeatedly in the years that followed by several printers, and no less than five times by the Būlāq Printing Press between 1865 and 1895. On the Bulāq Printing Press, established by Muḥammad ʿAlī in 1821, see Johannes Pedersen, Den Arabiske Bog (Copenhagen: Fischer, 1946).

25 Amal N. Ghazal, Islamic Reform and Arab Nationalism: Expanding the Crescent from the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean (1880s–1930s) (London: Routledge, 2010). On the transmission of texts within the Ibāḍī tradition, see also Rex S. O’Fahey, and Knut S. Vikør, “A Zanzibari Waqf of Books: The Library of the Mundhiri Family”, Sudanic Africa, 7 (1996), 4-23.

26 Graziano Krätli and Ghislaine Lydon, eds., The Trans-Saharan Book Trade: Manuscript Culture, Arabic Literacy and Intellectual History in Muslim Africa (Leiden: Brill, 2011); and Scott S. Reese, ed., The Transmission of Learning in Islamic Africa (Leiden: Brill, 2004). As an example of circulation to East Africa, see Philip Sadgrove, “From Wādī Mīzāb to Unguja: Zanzibar’s Scholarly Links”, in Reese, pp. 184-211.

27 Muṣṭafā b. Khayr al-Dīn b. ʿAbd Allāh al-Rūmī al-Ḥanīfī (d. 1616), Tartīb qawāʾid al-ashbāh wa’l-naẓāʾir (Tanwīr al-adhhān wa-‘l-damāʾir). The poor condition of this manuscript did not allow for its full digitisation. Its original reference in the Riyadha catalogue is RM6.

28 Interview, Aydaroos and Ahmad Jamal al-Layl, Lamu, Kenya, 5 December 2011.

29 For an overview of the introduction of print in the Islamic world, see Jakob Skovgaard-Pedersen, ed., Culture and History (16) special issue: The Introduction of the Printing Press in the Middle East (Oslo: Scandinavian University Press, 1997); Francis Robinson, “Technology and Religious Change: Islam and the Impact of Print”, Modern Asian Studies, 27 (1993), 229-51; A. Ayalon, “Private Publishing in the Nahḍa”, International Journal of Middle East Studies, 40:4 (2008), 561-77. For the spread of printing, see Nile Green, “Journeymen, Middlemen: Travel, Transculture and Technology in the Origins of Muslim Printing”, International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, 41 (2009), 203-24.

30 Bang, Islamic Sufi Networks, pp. 130-39; and Ghazal.

31 Ho, p. 154.

32 Bang, “Authority and Piety”. The example concerns a volume of Ramadan prayers, copied in 1847, which was made waqf for the Madrasa Bā Kathīr some time after the founder’s death in 1925.

33 Reinhard Schulze, “The Birth of Tradition and Modernity in 18th and 19th Century Islamic Culture: The Case of Printing”, Culture and History, 16 (1997), 29-72.

34 The awareness of these manuscripts as cultural heritage seems to have started in the 1970s. It is possible that this awareness stemmed at least partly from the Eastern Africa Centre for Research and Oral Tradition (EACROTONAL) manuscript survey in East Africa, which between 1979 and 1988 aimed to map and collect manuscripts for research. See Khamis, Khamis S., “The Zanzibar National Archives”, in Islam in East Africa, New Sources: Archives, Manuscripts and Written Historical Sources, Oral History, Archaeology, ed. by Biancamaria Scaria Amoretti (Rome: Herder, 2001), pp. 17-25. For a discussion and examples from Zanzibar, see Anne K. Bang, “Zanzibari Islamic Knowledge Transmission Revisited: Loss, Lament, Legacy – and Transformation”, Social Dynamics, 38/3 (2012), 419-34.

35 Bā Ṣafar is mentioned by Mohammad Ibrahim Abou Egl as one of the copyists whose handwriting resembles that of Muhammad Kijuma (see below). While Abou Egl does not provide any further identification of Bā Ṣafar, he does refer to manuscripts by Bā Ṣafar in European collections that are in Swahili. I have not consulted these for this article. Mohammad Ibrahim Abou Egl, The Life and Works of Muhamadi Kijuma (Ph.D. thesis, University of London, 1983), p. 160.

36 On the life of Kijuma, see ibid.

37 Ibid., p. 83.

38 Translation from Swahili in ibid., p. 158.