7. The first Gypsy/Roma organisations, churches and newspapers

© Elena Marushiakova and Vesselin Popov, CC BY http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0052.07

In the 1970s, a young and provocative German scholar, Kirsten Martins-Heuss, shocked the academic public with her statement that Gypsy Studies is “a science of the plagiarist”.1 It cannot be denied that there are still some grounds for such a critique. In the history of Gypsy (now known as Roma) movements and organisations, inaccurate data and interpretations often make their way from book to book without attempts at verification — for example, scholars refer to the Gypsy Conference in Kannstadt (Germany) in 1871, an event that never actually took place.2 However, it is not always inaccuracy on the part of scholars which is to blame, but the unavailability of complete or reliable records, or the use of second-hand data taken from other publications without first checking the primary sources.

In order to avoid such traps, the research for this chapter is based mainly on primary sources, uncovered among public or family records, most of which were collected, investigated and digitised as part of our projects supported by the Endangered Archives Programme (EAP).3 These sources have been largely out of circulation until now, and they throw new light onto several aspects of the history of the Roma movement for civic emancipation through the creation of public organisations. Apart from these sources, no other evidence corroborating the occurrence of most of the events discussed has been discovered to date.4 The digitised sources we rely on are stored in the Studii Romani Archive.5 A significant number may now also be accessed through the EAP website.6 The books and newspapers discussed are preserved in Bulgarian public libraries.

This chapter focuses on the sources that document the emergence and early development of Roma social and political projects in Bulgaria during the first half of the twentieth century, and that illuminate the main concepts of the emerging Roma discourse. These sources chart the key stages in the evolution of the Roma movement and encompass the movement’s different branches and aspirations.

The first Roma organisation

The first source presented in this chapter is an historical statute officially registering a Roma public organisation, written in the Bulgarian town of Vidin in 1910 and published in the form of a small book that same year. This group was, in all likelihood, the first state-approved Roma organisation in the world. The published registration document, entitled Ustav na Egiptyanskata narodnost v gr. Vidin [Statute of the Egyptian Nation in the Town of Vidin], designates the Roma as Egiptyani (“Egyptians” in Bulgarian), Kıpti (“Copts”, as in Ottoman sources) and Tsigani (“Gypsies” in Bulgarian).7

The creation and the main aims of the first Roma organisation in Bulgaria can be understood in the context of the country’s history. Part of the Ottoman Empire for five centuries, Bulgaria became an independent country in the aftermath of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878, first as the Bulgarian Principality and from 5 October 1908 as the Kingdom of Bulgaria. Independence changed the inter-ethnic relations of the country; whereas the position of ethnic Turks was established by peace treaties, the Roma were left out. Therefore, the foundation of the Roma organisation stemmed from the need to negotiate the new citizens’ situation. The Roma needed to secure the rightful status of their communities in the new independent state and to introduce legal parameters to the relationship between themselves and the state and local authorities, as well as to relations within their own community.8 Article 1 of the statute describes the main tasks of the organisation: “Under the old custom of the aforesaid nation in Vidin, this statute establishes procedures for their right-relations in the society and among themselves”.

The statute determined the terms of office and methods of election of the head of the organisation as well as his responsibilities:

Article 3: For compliance and enforcement of the regulations is to be responsible a chief, called mukhtar, who is elected indefinitely by lot from among nine people of the neighbourhoods’ elders – these leaders (çeribaşi)9 are to be determined by secret ballot among those who have civil and political rights. Even better, those who are inscribed in the municipal election lists should be eligible to become voters and to be elected. […]

Article 10: [A mukhtar is elected] to represent the group before the authorities of the state and all public institutions, [...] to protect the general moral and material interests of his compatriots, [...] to evoke civic awareness among his own people and to assist measures and introduce decrees needed for decent and respectable human life, [...] to take care of finding work for the poor, [...] ensuring proper mental, health and social education of adults, [...] to seek to ensure strict compliance with all lawful orders, [...] to give accurate information to all state and public institutions on issues concerning people of his own nationality.10

From the text of the statute, it is not clear who was the first head (mukhtar) of the new organisation, but most likely it was the chairman of the founding committee (comprising a total of 21 people), Gyullish Mustafa, who, as explicitly noted in the statute, was a member of the Bulgarian army in the position of reserve sergeant.11

All the designations used in these statute articles are taken from the old Ottoman Empire terminology, in which the mukhtar was the mayor of a village, elected by the population and representing the village before the authorities, and the çeribaşi were the heads of the Roma Cemaat (Tax Unit), responsible for collecting taxes.12 These designations were transferred to the new realities of the independent Bulgarian state: the mukhtar became the chief of the “Egyptians” in Vidin and its district, and the çeribaşi became the heads of separate Roma mahallas.13 The statute of the organisation reflects an effort to transfer and legalise existing social relations inherited from the time of the Empire, when the Roma were referred to as Kıptı or Çingene (“Gypsies” in Turkish); although without official status as a religious or ethnic community (millet in Bulgarian), they were de facto treated as such.14 The statute explicitly mentions that only those who are “inscribed in the municipal election lists” may participate in electing the organisation’s head — that is, those who have civil and political rights. This indicates that the organisation was established not only out of the Roma desire to be recognised as a distinct ethnic group, but also because of their aspirations to be publicly acknowledged as an equal part of the overall social structure of the new Bulgarian nation-state.

From the Statute of the Egyptian Nation in the Town of Vidin, it is clear that the organisation was self-financing. Its revenue was generated through “[...] voluntary donations and bequests [...] fines for divorce and unlawful cohabitation [...] interest from money-lending [... and] rents for the common property”.15 The organisation’s leaders (the mukhtar together with his deputy and treasurer) received annual remuneration for their “work” — a sum collected from all families “according to their property status”, of which “it is envisaged for the mukhtar to take half of the total amount and for half to be divided between his two assistants”.16

The statute also attempts to establish the Roma as a “nation”, equal to all other nations in the country, through symbols, signs and holidays. The organisation’s public symbols are described in detail — an example of the stamp of the organisation can be seen below (Fig. 7.1).

Fig. 7.1 Stamp of the Egyptian Nation organisation, Public Domain.

It is a circular stamp with the inscription “Kıptiysko mukhtarstvo – v g. Vidin (Coptic town hall – in the town of Vidin)”. The stamp depicts St George on horseback with a king’s daughter behind him and a spear in his hand, point stuck in a crocodile. As specified in the statute, the picture on the stamp illustrates “a girl who was doomed to be sacrificed to an animal, deified in Egypt, and who was rescued by St George in the same way as the people were saved from paganism”.17 Moreover, the mukhtar wore an oval metal emblem on his chest bearing the inscriptions “Koptic mukhtar” and “city of Vidin”. Between these two phrases was a graven image of the Eye of Horus, considered to be one of the major ancient Egyptian symbols.

The references to ancient Egypt in the names used to define the community, such as “Egyptians” and “Copts” in the organisation’s statute and symbols, reflected the belief at that time that the Roma had originated in Egypt.18 This belief was implied in the term Αιγύπτιοι (Aigyptioi), meaning Egyptian, whose use was already widespread in Byzantine times.19 It was also commonplace during the Ottoman period to use the term Kıpti to designate the Roma in state administrative documents. This designation was accepted by the Roma themselves, and it was the basis for the appearance of numerous etiological legends, widespread among the Roma in the Balkans in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These legends illustrate the community’s efforts to uncover their land of origin, “proof” of which they claimed to find in the Old Testament.20 The links made to ancient Egypt are a clear reflection of the Roma’s intention to express their equality with other nations that, unlike them, had their own countries of origin.

The statute designates St George’s Day, “which remained from the old times”, as the annual holy patron day.21 The honouring of St George as patron of the Roma and the celebration of his day (Gergyovden in Bulgarian, Ђurђevdan in Serbian, etc.) are reflected in both the stamp and the statute of the organisation: indeed, there was a widespread cult of St George among the Roma in the Balkans.22 Along with Roma Christians, the Muslim Roma also honoured this day under the name Hıdırlez (Hederlesi, Herdelez, Ederlezi, etc. in the Roma languages), replacing the Christian saint with the Islamic prophets Hızır and İlyas.23

It is noteworthy that among the members of the founding committee listed in the statute, those with Muslim names are more numerous than those with Christian names.24 At that time, the majority of Roma living in Vidin were Muslims: the fact that a Christian saint is on the organisation’s stamp shows that voluntary conversion to the new official religion (Orthodox Christianity) in the independent Bulgarian state had not only begun, but was already advanced. Nowadays, the conversion is complete: all Roma in Vidin are Christians, the memory of their previous religion is faint and for many it has already disappeared.25

To date, the Statute of the Egyptian Nation in the Town of Vidin is the only known piece of historical evidence supporting the existence of this first Roma organisation. It can be assumed that the organisation existed for only a relatively short period of time; soon after its establishment, a period of hosilities and conflicts began, which included two Balkan wars (1912-1913) and World War I, with the result that many Roma men were mobilised as part of the Bulgarian army and its military operations.26

Roma organisations and newspapers between the two World Wars

Two sources discovered 2007 and 2008 enable us to outline the development of the Roma movement in Bulgaria from the end of World War I to the mid-1950s.27 A 1957 book manuscript by Shakir Pashov reveals a number of important phases of this evolution in the first half of the twentieth century. Although the title of the manuscript, Istoriya na tsiganite v Balgaria i v Evropa: “Roma” [A History of the Gypsies in Bulgaria and in Europe: “Roma”], uses the term “Roma” in inverted commas as the designation for the community, the rest of the text employs the Bulgarian word Tsigani.28 The information we glean from this manuscript can be combined with insights provided by Shakir Pashov’s partially-preserved (the first page is missing), signed “Autobiography”, stored in his family archives and dated 1967.29

Shakir Mahmudov Pashov was born on 20 October 1898 in the village of Gorna Bania (today a neighbourhood of Sofia). His whole, often turbulent, life was dedicated to the Roma movement. He graduated from the railway workers’ school, was conscripted into the Bulgarian army during World War I and was wounded several times (Fig. 7.2). After his return from the War in 1919, according to his book manuscript and autobiography, he founded the “Bulgarian Communist Party among Gypsies” group in Sofia and served there as its secretary. He was employed by the Bulgarian State Railways until 1919, when he was fired for his involvement in the Communist-organised railway strike that paralysed the whole country.30

Fig. 7.2 Shakir Pashov as a soldier (EAP067/1/2/4, image 4), Public Domain.

In Pashov’s book manuscript, we read that on his initiative, a “Gypsy committee” was formed in 1919. This committee met Prime Minister Alexander Stamboliyski from the Bulgarian Agrarian Union (BAP) with a request for the reinstatement of Roma voting rights, which had been nullified by the Election Law of 1901.31 On 2 December 1919, the National Assembly passed a new electoral law introducing compulsory voting for all Bulgarian citizens; in practice, this law eliminated restrictions on the Roma’s voting rights. It was also in 1919 that, according to Pashov’s manuscript, a Druzhestvo Egipet (“Society ‘Egypt’” in Bulgarian) was established in which “the majority of the Gypsy intelligentsia and all the progressive youth” of Sofia participated. The main tasks of the society were “to raise the cultural and educational level of the society members and of the whole Gypsy minority, and most of all, to work to raise political and public awareness of the Gypsy minority”.32 A few months later, however, the General Assembly of the Society “Egypt” decided to merge with the Bulgarian Communist Party.33

In the Bulgarian archives there are no materials concerning the creation or registration of a public organisation called the Society “Egypt”. However, there is the statute of an association, approved by the Ministry of the Interior and Public Health on 2 August 1919,34 named Sofiyskata obshto myusulmansko prosvetno-kulturno vzaimospomagatelna organizacia “Istikbal-Badeshte” (Sofia’s Common Moslem Educational and Cultural Mutual Aid Organisation “Istikbal-Future”). The chair of this association was Yusein Mekhmedov and its secretary was none other than Shakir Mahmudov Pashov. The association that Pashov calls the Society “Egypt” in his book manuscript is in fact the Sofia Common Moslem Educational and Cultural Mutual Aid Organisation “Istikbal”. Pashov intentionally changed a wording which included the attribute “Moslem” to something more neutral. The manuscript was written at a time when the Bulgarian Communist Party was fighting against the “Turkisation of Gypsies”, and so Pashov considered it inappropriate to attract attention to his past activites in connection with Islam.35

However, in the 1919 statute, the words “Gypsy” or “Gypsies” do not appear once in connection with the Istikbal. From this statute it is clear that the Roma of Sofia (majority Muslim at that time) intended to use this organisation to acquire control of the mosque and waqf (Islamic religious endowment) properties in the capital city, manoeuvres which the local Islamic leaders resisted. The organisation filed a number of lawsuits in its attempt to acquire control of these assets. Indeed, the court proceedings and litigations dragged on for more than a year, but the case was eventually dismissed by the Supreme Administrative Court, and the organisation had, in the meantime, changed its name (see below).36

In the 1920s and early 1930s, Pashov was very active politically. In 1922 he was a delegate to the Congress of the Communist Party, and in 1924 he was elected municipal councillor as a member of the United Front, a coalition between the Communist Party and the left wing of the Bulgarian Agrarian People’s Party.37 Following the St Nedelya Church assault — a Bulgarian Communist Party terrorist attack carried out on 16 April 1925 — Pashov was arrested.38 Several months after his arrest, in the midst of the subsequent state political terror, he emigrated to Turkey.39 He returned to Bulgaria in 1929 and became an active member of the Bulgarian Workers’ Party (an organisation linked to the then-illegal Communist Party). As such, he was involved in the municipal election campaign of 1931. During this time, Pashov was also employed as a mechanic at the Municipal Technical Workshop until he was dismissed in 1935 because of his involvement in a political strike. He then opened a small private iron workshop.40

Although the association statute states that the Istikbal was established in 1919, Pashov claims in his manuscript and autobiograpy to have founded the organisation on 7 May 1929, with a membership of 1,500 people. In 1930 it absorbed several other Roma organisations of different kinds, such as mutual aid, cultural, educational and sport societies.41 The organisation then changed its name to Obsht mohamedano-tsiganski natsionalen kulurno-prosveten i vzaimospomagatelen sayuz v Balgaria (Common Mohammedan-Gypsy National, Cultural, Educational and Mutual Aid Union in Bulgaria).42 The word “Gypsy” is thus already present in the new name. Pashov himself headed this new organisation and also started publishing a newspaper called Terbie [Upbringing].43 According to Shakir Pashov’s book manuscript, “the progressive youth united […] the organisations under one common name: the Istikbal”.44 Once again Pashov retrospectively changed the organisation’s name in order to avoid the adjective “Mohammedan”, concealing its connection with Islam.

On 7 May 1932, a conference was held in the city of Mezdra, attended by Roma from different cities in northwest Bulgaria. At this conference, it was decided to open up the Istikbal, which until then had been an association exclusively for Roma residents of Sofia, to all Gypsies living in Bulgaria, and to distribute the newspaper Terbie throughout the country.45 Two years later, however, the organisation was banned and the newspaper closed. This was not a specific anti-Gypsy measure: the new pro-fascist government of Kimon Georgiev — which came to power following a military coup on 19 May 1934 — disbanded all political parties, trade unions and minority organisations, closing all their publications. Every attempt by Pashov to restore the organisation was unsuccessful.

After 1934, Pashov continued his political and cultural activities, albeit in different forms. He agitated with the Roma community to end the custom of Baba Hakkı (Turkish for “father rights”, i.e. bride price), created a Roma support association for funerals and established an informal Roma club, headquartered in the famous pub By Keva (Keva was the name of a very popular Gypsy singer and dancer of the time).46 In 1935, he organised a delegation comprised of Roma men and women wearing traditional shalvary (Islamic trousers) to greet the newborn Crown Prince Simeon at the King’s palace. On 3 March 1938, Pashov organised a ball for the Roma in an urban casino in the garden of the National Theatre, with musical and dance performances of the Arabian Nights. He personally invited Tsar Boris III, who did not attend but did send an envelope of money for the “poor Gypsies”.47

The account of the early history of the Bulgarian Roma movement in Pashov’s manuscript and autobiography cannot be regarded as entirely reliable: there are several differences between the two texts, and some discrepancies with other sources. We already mentioned the inconsistency between the dates given for the establishment of the Istikbal — 1919 according to the statute, a decade later according to Pashov.48 The State Archives, however, do not contain any references to the registration of the Istikbal at this later date, whereas they do provide supporting evidence for its creation in 1919. We also indicated the intentional names changes of Pashov’s organisations. In addition to the organisation’s statute, the State Archives preserve a letter from 10 July 1934 in which the the Ministry of the Interior and Public Health rejects its request for registration because “the Gypsy-Moslems in Bulgaria are organised under foreign influence”.49

These “errors” in Pashov’s manuscript and in his autobiography are not random. Pashov recounts the organisation’s development in accordance with the Communist ideology of the time. For example, the newspaper Terbie is described in Pashov’s manuscript as having been published on behalf of the Istikbal, whereas his autobiography associates it with the workers in the tobacco industry.50 The latter claim is clearly false, as the headings of the preserved issues of the newspaper clearly state that the newspaper is published by “the Mohammedan National Enlightenment and Cultural Organisation”, or, from the sixth issue onwards, by “the Mutual Mohammedan National Enlightenment and Cultural Union in Bulgaria”. Moreover, the newspaper Terbie was published from 1933 to 1934. Consequently, and contrary to what Pashov later claims, it would have been impossible to take the decision to widen the newspaper’s distribution at the 1932 conference in Mezdra since the newspaper did not at that time exist. Besides, the main problems discussed on the pages of all issues of Terbie were the protracted conflicts and disputes over the management of waqf properties and the admission or exclusion of Roma Muslims as mosque trustees.

In the same way, Pashov probably exaggerated his participation in political struggles as a member of the Communist Party. For example, he claimed to have been on the electoral list of the Communist Party for seats in the Bulgarian Parliament in the 1920s, among the leadership of the Workers’ Party in Sofia in the 1930s, and a resistance fighter in the 1940s. There are no documents in police archives to confirm Pashov’s claims, but there is evidence in the protocols and annual reports of local party organisations, and in letters of recommendation, indicating that his participation was more limited.51

In fact, Pashov’s approach to the preparation of his manuscript — his exaggerations, omissions and inaccuracies — was a response to the situation in Bulgaria at that time. Most probably he hoped to arrange publication of his book, although no correspondence with publishers or other sources has been unearthed to provide evidence for this. Under the conditions of a totalitarian state in which Communist Party control was comprehensive, any manuscript involving the history of the Communist Party would need to undergo an extensive review process by Party committees and editorial and censorship boards in order to be published. To fulfil these requirements, Pashov presumably chose to highlight his commitment and that of his organisations to the Communist Party, while concealing other key aspects of their activities.

Roma organisations and newspapers under Communist rule

In this section, we will illustrate the next stage in the development of the Roma movement by way of the difficult transformations sustained by the Roma organisations led by Pashov under Communist rule. The main archival sources we discuss are connected with the statute of the United General Cultural Organisation of Gypsy Minorities “Ekhipe” (referred to subsequently as the Ekhipe [Unity])52 and the newspaper Romano esi [Roma Voice].53

On 9 September 1944, after the Red Army entered Bulgaria, a new government dominated by the Communist Bulgarian Workers’ Party was established. After several transitional years, all power was seized by the Communist Party, and the construction of a new type of society, the socialist state, began. In this new political situation, Roma communties became the object of targeted state policy. They did not present an issue of paramount importance for the Bulgarian state — which had to solve many more urgent and significant socio-political and economic problems — but nevertheless their place in public policy is notable.54

For a relatively short period of time (from 1945 to 1950), the leading political line was to promote the Roma as an equal ethnic community within the Bulgarian nation and to encourage their active involvement in the construction of a new socialist society. This policy was in direct correlation with the so-called “korenizatsiia” (“indigenisation”) conducted in the USSR in the 1920s and 1930s — a strategy which aimed to support and develop the identity, culture, mother tongue and education of various ethnic communties, and which ended with the adoption of the new Soviet Constitution of 1936, also known as the Stalin’s constitution.55

In the case of Bulgaria, the promotion of Roma ethnicity in the first years of Communist rule was certainly inspired by the Soviet “indigenisation” policy. It is also likely to have stemmed, however, from the personal relationship between Shakir Pashov and Georgi Dimitrov, the famous Communist leader and Premier of the People’s Republic of Bulgaria (1946-1949). Pashov himself describes the history of his friendship with Georgi Dimitrov as follows:

During the 1923 election for Members of Parliament, among the candidates was also Comrade Georgi Dimitrov, who visited the polls of the Third District electoral station [...] and for a moment the opposition gang rushed at him with fists, but our party group, present as agitators, immediately pounced and got their hands off Dimitrov, as other comrades also arrived. We accompanied them to the tram and he [Dimitrov] said to me: “Shakir, when the day comes when we gain power, you will be the greatest man, and lay a carpet for me from the station to the palace”. And look, the glorious date 9 September 1944 arrived and it came true; I became a deputy in the Grand National Assembly, nurtured by the ideas of the Party, because my whole life passed in struggle for the triumph of Marxist ideas and in antifascist activities from 1919 to today”.56

After a short period of belatedly emulating the Soviet “indigenisation” policy, and after the death of Georgi Dimitrov, the Bulgarian state gradually returned to its former pattern of policies which underestimated or neglected Roma issues.57

While the“indigenisation” policy was still current, however, an initiative of the Central Committee of the Bulgarian Communist Party led to the creation, on 6 March 1945, of the Ekhipe organisation in the Roma neighbourhood of Tatarly in Sofia. 58 Pashov was elected as chairman of the Ekhipe’s central committee. The Central State Archive in Bulgaria preserves a draft of a statute belonging to the organisation.59 It is undated, but was probably prepared in 1945 or 1946, since the newspaper Romano esi reported on the organisation’s approval by the Minister of the Interior in 1946.60 Some statements in this document are particularly interesting, because they differ from — and even contradict — Soviet policy, thereby demonstrating the creativity of the Bulgarian Roma:

Paragraph 1. The United Gypsy Organisation in Bulgaria incorporates all Gypsies who belong to the Worldwide Gypsy Organisation and are members of the local societies of the United Gypsy Organisation in Bulgaria where they pay their membership fees.

Paragraph 2. The United Gypsy Organisation in Bulgaria is the legitimate representative of the Gypsy movement in the country and before the Worldwide Gypsy Organisation. All members of the organisation are Gypsies over 18 years of age, of Islamic or Orthodox religion, without discrimination on the basic of gender or social status.

Paragraph 3. The United Gypsy Organisation has the following tasks:

А) To struggle against Fascism, as well as anti-Gypsy and racist prejudices; B) To raise Gypsy national sentiment and consciousness among Bulgarian Gypsies; C) To introduce the Gypsy language to the Gypsy masses as a spoken and written language; […] E) To acquaint the Bulgarian Gypsy minority with Gypsy spiritual, social and economic culture; [...] I) To illuminate Bulgarian public opinion about the needs of the Gypsy population; K) To create a sense of striving among Gypsies towards developing a national home on their own land.

As can be clearly seen from the draft statute quoted above, its author(s), presumably Pashov himself, articulate a number of specific objectives for the new organisation, reflecting an attempt to promote equality for the Roma in Bulgarian society. However, it is not clear what is meant by the “Worldwide Gypsy Organisation”, since no such organisation existed at that time. Statements of this sort may indicate that Pashov had a strategic plan to lay the foundations for a global organisation uniting the Roma worldwide. He may have even considered the creation of a separate, independent Roma state.

All these visions, however, are excluded from Pashov’s book manuscript, which is understandable given that the book was written later, when the policy of the Bulgarian state towards the Roma had changed and the internationalisation of the Roma movement was considered undesirable. A comparison of the aims in the draft statute to the actual development of his organisation in the coming years demonstrates that political realities forced Pashov to abandon his ideas of global unity for the Roma and to focus his efforts on solving the particular problems of the Roma in Bulgaria.

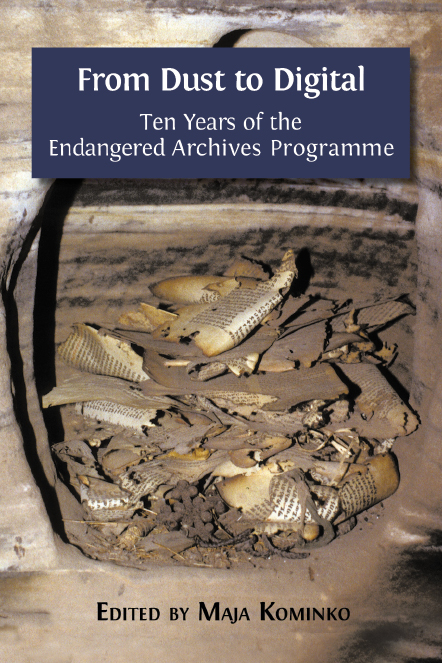

Fig. 7.3 Roma youth preparing a sample of the future alphabet

(EAP067/8/1/16), Public Domain.

The draft statute for the Ekhipe organisation specifies public symbols, particularly a flag and an official holiday. Article 59 decrees the holiday to be 7 May (that is, the day after the St George festivities) and the flag to be red with two white fields and a triangle in the middle. In line with the effort to create a Roma flag and an official holiday — symbols which are characteristic of all nation-states — was the attempt to create a national Roma alphabet, distinct from the Bulgarian one (Fig. 7.3).

We have collected numerous narratives from all over Bulgaria describing these endeavours, but we were able to find only one source documenting them: a photograph from this period which shows Roma youth preparing a sample of the future alphabet.61 Among the youth activists in this photo, we identified Sulyo Metkov, Yashar Malikov and Tsvetan Nikolov, who were also active in the Roma movement in later years. Moreover, the new organisation started publishing the newspaper Romano esi, with Pashov as editor-in-chief. The first issue appeared on 25 February 1946.62

TheEkhipe’s draft statute clearly shows that it was founded not by government initiative, but by the Roma themselves. The document gives no indication of a political commitment to any socio-political formation, but the organisation was to become politicised very quickly nonetheless. Immediately after 9 September 1944, Pashov himself became involved in the activities of the Fatherland Front.63 As articles in Romano esi document, a Roma section of the Fatherland Front was established, and Pashov was elected its chairman. He ran agitation campaigns for the inclusion of the Roma and for their participation in the election of a Grand National Assembly, held on 27 October 1946. Some photographs illustrating his agitation campaigns are preserved in Pashov’s family archive.64

On 28 February 1947, a letter from the “All Gypsy Cultural Organisation” (another name used for the Ekhipe) to the regional committee of the Fatherland Front was discussed at a meeting of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Bulgarian Workers’ Party.65 The letter proposed the appointment of Pashov as a representative of the Roma minority in Sofia in the upcoming election on 27 October (i.e. the letter was only discussed several months after the election). The letter itself was written on behalf of the “Common Organisation of the Gypsy Minority for Combating Fascism and Racism”, which is yet another name for the Ekhipe. Such discrepancies over the exact name of this Gypsy organisation are also found in many other sources, preserved in the Fund of State Agency Archives.66 According to this letter, a conference which brought together the chairs of the different sections (occupational unions) of the organisation, including fourteen delegates representing 300 members, took the following decision:

Because of today’s Fatherland Front government, after 9 September 1944 wider and greater freedom was given to the Bulgarian people, and mostly to the national minorities, such as we are, who in the past were treated like cattle and not respected as people. In today’s democratic government we must emphasise that we value our freedom, and must morally and materially, even at the expenses of our lives, give support to the Fatherland Front, the only defender [...] of national minorities. That’s why we all [...] in the upcoming crucial moments [...] have to appoint our representative to represent the Roma minority in the Grand National Assembly.

A secret ballot was conducted and Pashov was elected as the Roma representative. For the discussion of this letter at the meeting of the Politburo, two other documents are of use and relate to Pashov: his autobiographical statement and an attestation made by the district committee of the Communist Party. In the autobiographical statement, Pashov writes that since 1918 he had been a member of the Bulgarian Social Democratic Workers’ Party (Narrow Socialists), which subsequently developed into the Bulgarian Communist Party, and that he had actively participated in its political struggles for more than two decades. The attestation confirms his participation in the Communist movement and also notes that he was arrested on two occasions (in 1923 and 1925), and that subsequently his membership was suspended. A special emphasis is placed on the influence which Pashov has among the Roma and on the fact that he “is considered as the honest one in midst of this minority”, “progressive and with relatively higher culture”, and promising “if it comes to selecting a candidate from Gypsy minority” since “[one] more appropriate than he does not exist”.67 The attestation also states that with the inclusion of Pashov as a Member of Parliament, “the party can only win since it will raise the party in the eyes of the Gypsy minority and the party will become firmly rooted among the Gypsy minority”.68 Based on the documents submitted, the Politburo took the following decision: “[...] 2. Comrade Dimitar Ganev to resign as MP. To recommend to the next comrades on the list [...] to resign in order to enable the entry into the Grand National Assembly of Comrade Shakir Pashev69 (a Gypsy)”.

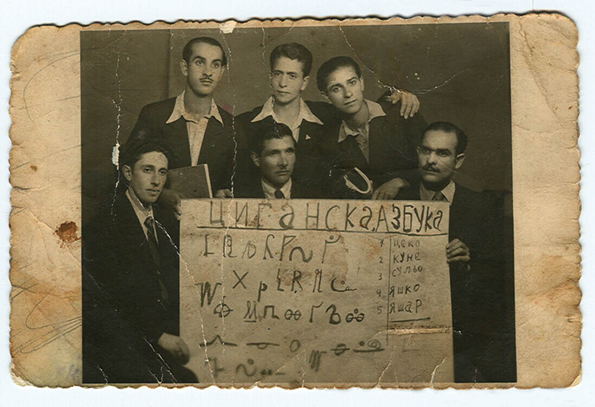

Fig. 7.4 Shakir Pashov (centre) as a Member of Parliament with voters (EAP067/1/1/14), Public Domain.

As a member of the Grand National Assembly, Pashov worked on the new constitution of the People’s Republic of Bulgaria (called Dimitrov’s Constitution), adopted on 4 December 1947. It prohibited the propagation of any racial, national or religious hatred (Art. 72), and stipulated (Art. 79) that “national minorities have the right to learn their mother tongue and to develop their national culture”. As a Member of Parliament and leader of the Roma organisation, Pashov was very active (Fig. 7.4). He toured the country, campaigned among the Roma for their engagement in public and political life and pushed for the creation of Roma workers’ cooperatives (such as the “Carry and Transport” association of porters and carters in Sofia). He also helped to overcome the tension in Ruse resulting from exclusion of Roma from the management of waqf properties, and to resolve internal conflict among Roma in the village of Golintsi (today the neighbourhood of Mladenovo in Lom).70

One of Pashov’s main aims was the development of Gypsy organisations in Bulgaria. He initiated the establishment of new branches of the Ekhipe, which until then had only been for the Roma of Sofia, and in short order approximately ninety branches of the organisation appeared in various towns.71 The support of the ruling Communist regime was crucial to achieving this. In July 1947, a special circular of the National Council of the Fatherland Front was distributed.72 On the basis of articles 71 and 72 of the new constitution, the circular instructed all local authorities and party organisations to support the creation of Roma cultural and educational associations in every village or town where there were at least ten Roma families living.

Local Roma organisations were officially considered to be substructures of the united Ekhipe, though in practice they had autonomy from its central leadership. They were not, however, independent of the Communist Party. The dynamic is clear from the extensive collection of documents of the main Communist Party organisation Istiklyal in Varna (and the particular Roma neighbourhood of Mikhail Ivanov), members of which created their own branch of the Cultural and Educational Society Istiklyal.73 The numerous documents, letters, protocols, minutes and decisions of these two Roma organisations outline their activities and their close links to (and de facto dependence on) city and regional Communist Party leadership. There is no evidence, however, of their maintaining any relations with the Ekhipe.

In 1947, at the instigation of Pashov and with his active support as a Member of Parliament, the “First Gypsy School” in Sofia was built in the Roma neighbourhood of Fakultet. The elders of the neighbourhood still remember these events and the school remains in operation. In his speech at the opening of the school, Pashov said:

We must express our gratitude to the Government of the People’s Republic of Bulgaria, which treats us as equal citizens. Before 9 September, nobody considered us as people […] but after 9 September 1944, the Government of the Fatherland Front gave us complete freedom and made us equal with other citizens. It gave us complete freedom for cultural progress.74

In 1947, following the example of the famous Soviet Romen Theatre,75 the “Central Gypsy Musical Artistic Roma Theatre” was founded under Pashov’s leadership.76 After a personal meeting with Georgi Dimitrov, then head of the Bulgarian state, Pashov secured from the state budget two million Bulgarian lev for the theatre.77

With Pashov as director, the Roma Theatre regularly put on performances in Sofia and toured around the country, presenting productions which included the unpublished play “White Gypsy”, authored by Pashov himself.78 Bulgarian National Radio regularly broadcast Roma music, and on St Basil’s Day a special programme was aired to celebrate the so-called “Gypsy New Year”.79

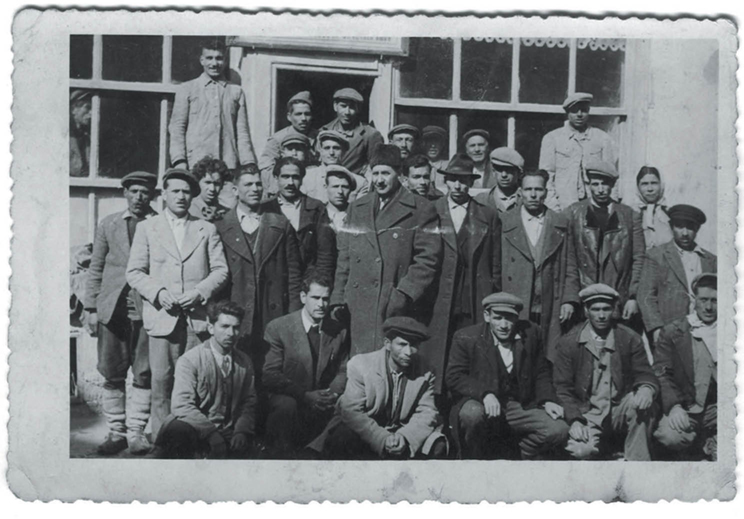

Pashov enjoyed great popularity among the Roma in Bulgaria, as evidenced by a poem written in the spirit of the era by a Rom, Alia Ismailov, and published in Romano esi. It ends with the verse: “... Da zhivee Stalin, Tito, Dimitrov / i drugariat Shakir Mahmudov Pashov! (Long live Stalin, Tito, Dimitrov / and Comrade Shakir Mahmudov Pashov!)”.80 In 1948, Pashov’s popularity reached its peak, as did the Roma movement during the period of Communist rule. On 2 May 1948, at its national conference, the Ekhipe confirmed its commitment to the policy of the Fatherland Front, which by this time had become a mass public organisation led by the Communist Party (Fig. 7.5).

Fig. 7.5 Shakir Pashov (centre) with participants at the national conference

of the Ekhipe (EAP067/1/1/1), Public Domain.

With the active support of the authorities, the creation of new local Roma organisations continued after the Ekhipe’s national conference, and they were incorporated into the Fatherland Front as “Gypsy” sections.81 Linking with the Fatherland Front, however, had unintended consequences for the Roma organisations and for Pashov himself: it led to the end of the Bulgarian state’s support for Roma ethnic affirmation. In the autumn of 1948, the National Council of the Fatherland Front commissioned an assessment of the current activities of the Roma organisations and of the Roma Theatre. In their prepared statement we read:

“[...] The very establishment of the organisation is positive, because it comes to satisfy blatant needs of the Gypsies for education. But from the outset it was not on a sound footing, lacking any connection at all with the Fatherland Front Committees. It is for this reason that the Gypsy organisation launched an improper policy and worked along their Gypsy, minority line. Left to itself without the control of the Fatherland Committees and their immediate help, the organisation was systematically ill [...] On 2 May 1948, without asking the opinion of the National Council of the Fatherland Front, a national conference of the Gypsy minority in Bulgaria was held at which a Central Initiative Committee was elected […] Among the leadership two currents were established:

А) One stream was headed by MP Shakir Mahmudov Pashev, who gathered around himself a set of the petite bourgeoisie; they approved his actions and decisions uncritically.

B) The other stream was led by young communists who disagreed with the philistine understandings of MP Pashev and mercilessly criticised his deeds as unsystematic. [...]

Given the above, I have the following recommendations:

1. To carry out the reorganisation of the Central Initiative Committee, since a committee for the Gypsy minority should be formed which should be directly guided by the National Council of the Fatherland Front.

2. To remove the county and city committees of the Cultural and Educational Society of the Gypsy Minority and instead form Gypsy commissions attached to the respective minority commissions of the urban committees of the Fatherland Front. [...]

The Central Gypsy Theatre was set up in 1947-48 at the initiative of the Cultural and Educational Society of the Gypsy Minority; however, it was not established on the correct foundation, and because of that it is undergoing complete collapse.82

As a consequence of these conclusions, the Theatre was suspended and its future existence put in question. “Upon the request of the minority itself”, the National Council of the Fatherland Front and its Minority Commission convened a general conference, which reported on both the positive and negative sides of the old management. A new leadership for the Roma Theatre, headed by Mustafa/Lubomir Aliev, was selected and approved.83 The conference decided to put the Theatre under the auspices and direct control of the Minority Commission in financial and administrative matters, and in the hands of the Committee on Science, Art and Culture regarding matters of artistic accomplishment.84

Pashov was dismissed from the leadership of the Roma Theatre on the grounds of “financial and accounting irregularities in its management”.85 He was also fired from his position as editor-in-chief of Romano esi. After the tenth issue was printed in 1948, the letterhead of the newspaper identifies Aliev as the head of the editorial board. This marks the begining of a long struggle between Pashov and members of the “Saliko”, the local Roma branch of the Communist Party, such as Tair Selimov, Aliev, Sulyo Metkov and Angel Blagoev. The conflict expressed itself in letters containing unpleasant accusations and sent to various authorities, in new convocations of committees of the Fatherland Front, in new audits. Finally, a special comission of the Central Committee of the Bulgarian Workers’ Party accused Pashov of many misdemeanours, especially in relation to his former work as a Roma activist before and during World War II — for example, his establishment of a Muslim organisation in 1919 and his management during the war of a charity in aid of Bulgarian officers and German soldiers. Finally, in the autumn of 1949, the city committee of the renamed Bulgarian Communist Party expelled Pashov from the Party.86

In the parliamentary elections of 18 December 1949, Pashov was replaced by Petko Yankov Kostov of Sliven as the Roma representative in the National Assembly.87 A few months later, the newspaper Nevo drom, which had replaced Romano esi, contained the following official announcement:

The central leadership of the Cultural and Educational Society of the Gypsy Minority in Bulgaria, after examining the activities of Shakir Mahmudov Pashev at its meeting on 7 April this year [1950], took the following decisions:

For activity against the people before 9 September 1944 as an assistant to the police and for corruption after this date as leader of the Gypsy minority, Shakir Mahmudov Pashev is to be punished by being removed from the position of president of the Cultural and Educational Society of the Gypsy Minority in Bulgaria and permanently excluded from the organisation’s ranks.

Comrade Nikola Petrov Terzobaliev of Sliven is elected Chairman of the Cultural and Educational Society of the Gypsy Minority in Bulgaria.88

Soon after this decision, Pashov was arrested and sent to the concentration camp on the Danube island of Belene.89 His removal from the leadership of the Roma organisations was followed by rapid changes in the Roma movement as a whole. The local Roma organisations were disbanded and their members absorbed into the regular territorial sections of the Fatherland Front, thus losing their distinction as “Gypsy” sections.90

The Roma newspaper and Theatre suffered similar fates. Nevo drom published its last issue in 1950. Although a proposal was put forward to dissolve the Roma Theatre, Decision 389 of the secretariat of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, dated 25 November 1949, recommended that the Roma Theatre continue to exist with the status of a “semi-professional” theatre integrated into the neighbourhood’s community centre. At that time, community centres were organised according to ethnicity and corresponded to the specific make-up of neighbourhoods. The Theatre ceased to exist in the 1950s.91

Pashov remained in the concentration camp until its closure on 1 January 1953. He was rehabilitated after the April Plenum of the Central Committee of the Communist Party in 1956, during the course of which those accused of so-called “cults of personality” and “perversions of the party line” were convicted. In 1957, Pashov joined the leadership of the Roma community reading centre “Ninth of September” in Sofia.92 He actively contributed to the newspaper Neve Roma [New Roma] that the centre began to publish and helped to create the Artistic Collective for Music, Songs and Dances “Roma”.93

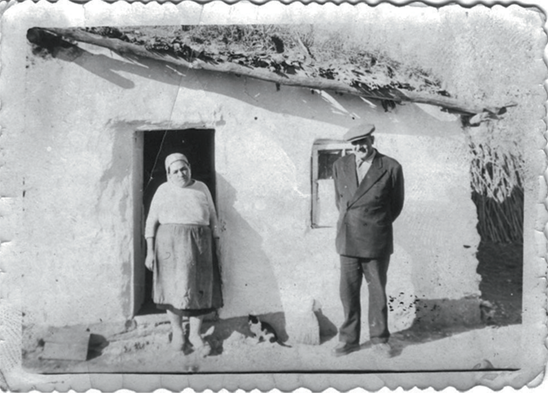

Pashov’s resumed activism did not last long. Soon he was persecuted again by the authorities, accused of “Gypsy nationalism” and, together with his wife, interned for three years (1959-1962) in Rogozina, a village in the Dobrich region (Fig. 7.6).94

Fig. 7.6 Shakir Pashov with his wife in Rogozina (EAP067/1/1/13), Orphan Work.

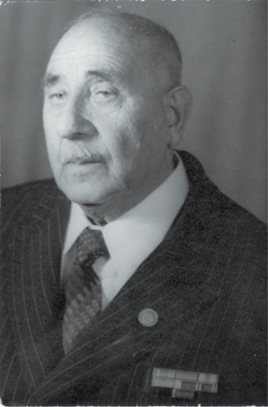

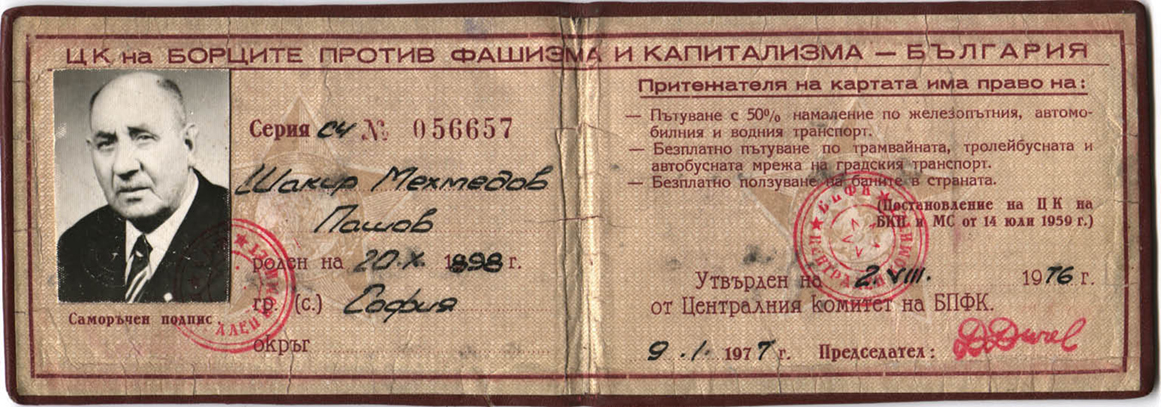

He was again rehabilitated in the second half the 1960s. In 1967 he was granted the so-called personal pension, and in 1976 he received the high title of “active fighter against fascism and capitalism” (Figs. 7.7 and 7.8).95 After returning from internment in the Dobrich region, Pashov no longer took an active part in public life, and his name disappeared from the public domain. In the book Gypsy Population in Bulgaria on the Path to Socialism, published by the National Council of the Fatherland Front in 1968, there is no mention of Pashov or his activities.96

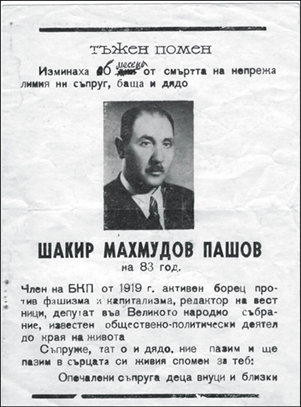

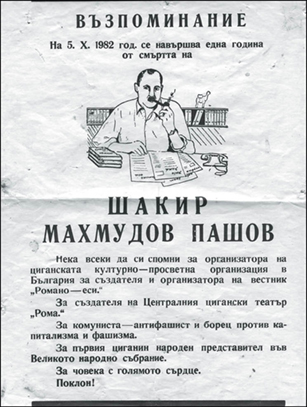

Shakir Pashov died on 5 October 1981 (Figs. 7.9 and 7.10).97

Fig. 7.7 Shakir Pashov as an honoured pensioner (EAP067/1/2/5), Orphan Work.

Fig. 7.8 Shakir Pashov’s card identifying him as an “active fighter

against fascism and capitalism” (EAP067/1/8), Public Domain.

Fig. 7.9 Obituary commemorating the six-month anniversary

of Shakir Pashov’s death (EAP067/1/9, image 2), Public Domain.

Fig. 7.10 Obituary commemorating the first full anniversary

of Shakir Pashov’s death (EAP067/1/9, image 3), Public Domain.

Roma churches and religious newspapers

Parallel to the events discussed above, the Roma movement in Bulgaria in the 1930s and 1940s was marked by the rise of another new phenomenon: the arrival of evangelicalism and the establishment of “Gypsy” evangelical churches. In general, the establishment of the “new” churches of denominations different from Eastern Orthodoxy and Islam had begun in the area as early as the nineteenth century and continued under the new Bulgarian state. Gradually an interest in the Roma arose among the missionaries. The first successful mission among the Roma was in the village of Golintsi, the present-day neighbourhood of Mladenovo in Lom. A legend is still recalled by local Roma recounting the circumstances in which the “new faith” was accepted. According to this story, a Rom found the New Testament in a bag of maize which he stole from a Bulgarian. Being illiterate, the man gave the holy book to another Rom called Petar Punchev, who could read and who began to spread the word of Jesus among the Roma.98

In reality, two Roma pastors, Petar Punchev and Petar Minkov, pioneered the establishment of Roma evangelical churches in Bulgaria. Punchev was born in 1882 into a family of formerly nomadic Roma who had recently settled in Golintsi. Between 1903 and 1910 he frequented the Baptist Home in Lom, where he was baptised in 1910. He started preaching shortly thereafter and, as a result of his activity, a separate Roma church gradually took shape, first as a branch of the Lom church with 29 members. In 1923, Punchev was officially ordained a pastor, and the Roma church assumed official status as an organised church structure.99 In 1927, Punchev published the only issue of the newspaper Svetilnik [Candlestick], with a supplement in the Roma language (Romani) entitled Romano alav [Roma Word].100 This issue of the newspaper includes the legend of the “stolen gospel” and reports on the preparations of the Golintsi Roma women’s missionary society for the New Year soirée. Evangelical texts in Romani were also published in the paper under the heading Romano alav.

After Punchev’s death (the year of which is unknown), the Baptist church in Lom made an unsuccessful attempt to annex the Roma church.101 Yet the Roma church remained independent even though an ethnic Bulgarian, Petar Minkov, became its head.102 Minkov preached in the 1920s and 1930s among the Roma in Golintsi, where he founded a Sunday school and where he opened a new church building in 1930.103 He also published two miscellanies with religious songs in Romani — Romane Svyato gili [Roma Holy Song] (1929) and Romane Svyati Gilya [Roma Holy Songs] (1933) — as well as a second Gypsy church newspaper in Bulgarian, Izvestiya na tsiganskata evangelska missiya [Reports on the Gypsy Evangelical Mission] (1933). In 1933, Minkov left Golintsi for Sofia, where he founded a school for illiterate Muslim Roma.104

In spite of the restrictive policy towards evangelical churches established after the pro-fascist coup d’état of 1934, evangelical preaching among the Roma continued and expanded into new regions, as illustrated by the publication in Romani of the Gospels of Matthew and John,105 and of an entire cycle of evangelical literature.106 Under Communist rule, the activities of Roma churches were strongly limited and supervised by authorities, and so their members gathered in private homes. After the breakdown of the socialist system in eastern Europe, evangelicalism among the Roma rapidly recovered, developed widely and became an important factor in the Roma movement.107

Postscript

We hope that this chapter has shown that the first half of the twentieth century was a period of serious, even cardinal, changes in the social life of the Roma communities of Bulgaria. It may be worth noting that similar changes also occurred in all the countries of southeastern Europe. These parallel developments may be briefly illustrated by the following list of dates for the founding of Roma organisations in the region and at that time.

In Romania, the organisation Infrateria Neorustica was established in 1926 in Făgăraş county; 1933 saw the foundations of the Asociaţia Generala a Ţiganilor din Romania (General Association of the Gypsies in Romania), headed by Ion Pop-Şerboianu (Archimandrite Calinik), and the alternative Uniunii Generale a Romilor din Romănia (General Union of the Roma in Romania), headed by Gheorghe A. Lǎzǎreanu-Lǎzurica and Gheorghe Niculescu. In the 1930s, the newspapers О Rom [The Roma], Glasul Romilor [Voice of the Roma], Neamul Ţiganesc [Gypsy People] and Timpul [Times] were published.108

In Yugoslavia, Prva srpsko-ciganska zadruga za uzajmno pomaganje u bolesti i smrti (The First Serbian-Gypsy Association for Mutual Assistance in Sickness and Death), headed by Svetozar Simić, was inaugurated in 1927; and in 1935, the Udruženja Beogradskih cigana slavara Tetkice Bibije (Association of Belgrade Gypsies for the Celebration of Aunt Bibia) was established. In 1930, the newspaper Romano lil/Ciganske novine [Roma Newspaper/Gypsy Newspaper] was published, while Prosvetni klub Jugoslavske ciganske omladine (The Educational Club of Yugoslavian Gypsy Youth), which grew into Omladina Jugoslavo-ciganska (Yugoslavian-Gypsy Youth), also took shape.109

In Greece, the Panhellenios Syllogos Ellinon Athinganon (Panhellenic Cultural Association of the Greek Gypsies) was founded in Athens in 1939; its main goal was to obtain Greek citizenship and passports for Roma immigrants to Greece from Asia Minor in the 1920s.110

In the new ethno-national states of southeastern Europe, the Roma wanted to be recognised as equal citizens of the new social realities without, however, losing their own ethnic identity. This was the main goal of all the Roma organisations created in the period between the two World Wars.111

The reasons for the rapid development of the Roma movement in southeastern Europe during this period, which has no analogue in other parts of the world, should be sought in the Roma’s specific social position and in the specific history of the region. The Roma had lived in the region since Ottoman times and were an integral part of wider society, which is why they strove for equal participation in the political life of their countries. At the same time, they also wished to preserve their ethnic distinction. In other words, the Roma have always existed in at least two dimensions, or on two coordinate planes: both as a separate ethnic community (or, more exactly, communities) and as part of a society, as an ethnically-based group integral to the nation-state of which the Roma are residents and citizens.112 The entire modern history of the Roma represents a search for balance between these two dimensions, without which it is impossible to preserve their existence as a separate ethnic group. The events presented in this chapter have illustrated the initial attempts of prominent Roma activists to reach such a balance in Bulgaria.

The most impressive illustration of these processes — in the context of the global social changes that occurred after World War I — is that given by Bernard Gilliat-Smith, who, as a British diplomat in Bulgaria during those years, offers an outsider’s perspective on the development of the Roma. It is worth quoting his explanation of the changes in the community that he observed:

[… it] was due, I think, to the effects of the First Great War. Paši Suljoff’s generation represented a different “culture”, a culture which had been stabilised for a long time. The Sofia Gypsy “hammal”113 was — a Sofia Gypsy “hammal”. He did not aspire to be anything else. He was therefore psychologically, spiritually at peace with himself […] Not so the post-war generation [of Gypsies in Sofia …] who could be reckoned as belonging to the proletars of the Bulgarian metropolis. The younger members of the colony were therefore already inoculated with a class hatred which was quite foreign to Paši Suljoff’s generation […] To feel “a class apart”, despised by the Bulgars who were, de facto, their “Herrenfolk”, was pain and grief to them.

References

Achim, Viorel, The Roma in Romanian History (Budapest: CEU Press, 2004).

Acković, Dragoljub, Nacija smo a ne cigani [We are a Nation, but not Gypsies] (Belgrade: Rrominterpress, 2001).

Anonymous, Barre pridobivke [Large Gains] (London: Scripture Gift Mission, [n.d.]).

—, O Del vakjarda [The Lord Said] (London: Scripture Gift Mission, [n.d.]).

—, O drom uxtavdo [The High Road] (London: Scripture Gift Mission, [n.d.]).

—, Duvare bianipe [Two Times Born] (Sofia: [n. pub.], 1933).

—, Romane Svyato Gili [Roma Holy Song] (Lom: Balgarska evangelska baptistka tsarkva, 1929).

—, Romane Sveti Gilya [Roma Holy Songs] (Sofia, Sayuz na balgarskite evangelski baptistki tsarkvi, 1933).

—, Savo peresarla Biblia [What the Bible Tells] (London: Scripture Gift Mission, [n.d.]).

—, Shtar bezsporne fakte [Four Indisputable Facts] (London: Scripture Gift Mission, [n.d.]).

—, Spasitel ashtal bezahanen [The Saviours Remaimed Without Sins] (London: Scripture Gift Mission, [n.d.]).

—, Spasitelo svetosko [The Saviours of the World] (London: Scripture Gift Mission, [n.d.]).

—, Tsiganska evangelska baptistka tsarkva s. Golintsi [Gypsy Evangelical Baptist Church in the Village of Golintsi] (Lom: Alfa, 1926).

—, Ustav na Egiptyanskata narodnost v gr. Vidin [Statute of the Egyptian Nation in the Town of Vidin] (Vidin: Bozhinov & Konev, 1910).

Atanasakiev, Atanas, Somnal evangelie (ketapi) kataro Ioan [Holy Gospel (Book) of John] (Sofia: Amerikansko Bibleisko druzhestvo & Britansko i chuzhdestranno Bibleisko druzhestvo, 1932).

—, Somnal evangelie (lil) Mateyatar [Holy Gospel (Book) of Matthew] (Sofia: Amerikansko Bibleisko druzhestvo & Britansko i chuzhdestranno Bibleisko druzhestvo, 1932).

Braude, Benjamin, and Bernard Lewis, eds., Christians and Jews in the Ottoman Empire: The Functioning of a Plural Society, 1 (New York: Holmes and Meier, 1982).

Büchsenschütz, Ulrich, Maltsinstvenata politika v Balgaria: Politika na BKP kam evrei, romi, pomatsi i turtsi 1944-1989 [The Minority Policies of the Bulgarian Communist Party Towards Jews, Roma, Pomaks and Turks (1944-89)] (Sofia: IMIR, 2000).

Chary, Frederick B., The History of Bulgaria (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2011).

Crampton, Richard, Bulgaria (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990).

Çelik, Faika, “Exploring Marginality in the Ottoman Empire: Gypsies or People of Malice (Ehl-i Fesad) as viewed by the Ottomans”, EUI Working Paper RSCAS, 39 (2004).

—, “‘Civilizing Mission’ in the Late Ottoman Discourse: The Case of Gypsies”, Oriente Moderno, 93 (2013), 577-97.

Detrez, Raymond, Historical Dictionary of Bulgaria (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2006).

Dunin, Elsie Ivančić, Gypsy St. George’s Day – Coming of Summer. Romski Gjurgjovden. Romano Gjurgjovdani-Erdelezi: Skopje, Macedonia 1967-1997 (Skopje: Združenie na ljubiteli na romska folklorna umetnost “Romano ilo”, 1998) [trilingual book in English, Macedonian and Romani].

Genov, Dimitar, Tair Tairov and Vasil Marinov, Tsiganskoto naselenie v NR Balgariya po patya na sotsializma [Gypsy Population in the People’s Republic of Bulgaria on the Road to Socialism] (Sofia: Natsionalen savet na Otechestveniya front, 1968).

Gilliat-Smith, Bernard, “Two Erlides Fairy-Tales”, Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society, 24/1 (1945), 18-19.

Gorchivi istini: Svidetelstva za komunisticheskite represii [Bitter Truths: Evidence of Communist Repressions] (Sofia: Tsentar za podpomagane na khora, prezhiveli iztezania, 2003).

Kasaba, Reşat, A Moveable Empire: Ottoman Nomads, Migrants, and Refugees (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2009).

Kenrick, Donald, The Romani World: A Historical Dictionary of the Gypsies, 3rd edn. (Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press, 2007).

Kostentseva, Raina, Moyat roden grad Sofia. V kraya na XIX nachaloto na XX vek i sled tova [My Home City of Sofia: At the End of the 19th Century, the Beginning of the 20th Century and After] (Sofia: Riva, 2008).

Krastev, Velcho, and Evgenia Ivanova, Ciganite po patishtata na voynata [Gypsies on the Road of the War] (Stara Zagora: Litera Print 2014).

Kovacheva, Lilyana, Shakir Pashov: O Apostoli e Romengoro [The Apostle of Roma] (Sofia: Kham, 2003).

Kyuchukov, Hristo, My Name Was Hyussein (Honesdale, PA: Boyds Mills Press, 2004).

Lemon, Alaina, “Roma (Gypsies) in the Soviet Union and the Moscow Teatr ‘Romen’”, in Gypsies: An Interdisciplinary Reader, ed. by Diana Tong (New York: Garland 1998), pp. 147-66.

Liégeois, Jean-Pierre, Roma in Europe, 3rd edn. (Strasbourg: Council of Europe, 2007).

Martins-Heuss, Kirsten, Zur mythischen Figur des Zigeuners in der deutschen Zigeunerforschung (Frankfurt: Hagg Herchen, 1983).

Marushiakova, Elena, “Gypsy/Roma Identities in New European Dimension: The Case of Eastern Europe”, in Dynamics of National Identity and Transnational Identities in the Process of European Integration, ed. by Еlena Marushiakova (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 2008), pp. 468-90.

Marushiakova, Elena, and Vesselin Popov, Gypsies (Roma) in Bulgaria (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1997).

—, “Myth as Process”, in Scholarship and the Gypsy Struggle: Commitment in Romani Studies, ed. by Thomas Acton (Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press, 2000), pp. 81-93.

—, Gypsies in the Ottoman Empire (Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press, 2001).

—, “The Roma – A Nation without a State?: Historical Background and Contemporary Tendencies”, Orientwissenschaftliche Hefte, 14 (2004), 71-100.

—, “The Vanished Kurban: Modern Dimensions of the Celebration of Kakava/Hidrellez among the Gypsies in Eastern Thrace (Turkey)”, in Kurban on the Balkans, ed. by Bilijana Sikimić and Petko Hristov (Belgrade: Institute of Balkan Studies, 2007), pp. 33-50.

—, “Zigeunerpolitik und Zigeunerforschung in Bulgarien (1919-1989)”, in Zwischen Erziehung und Vernichtung. Zigeunerpolitik und Zigeunerforschung im Europa des 20, ed. by Michael Zimmermann (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 2007), pp. 125-56.

—, “Soviet Union Before World War II”, Factsheets on Roma, Council of Europe, 2008, http://romafacts.uni-graz.at/index.php/history/second-migration-intensified-discrimination/soviet-union-before-world-war-ii

—, “State Policies under Communism”, Factsheets on Roma, Council of Europe, 2008, http://romafacts.uni-graz.at/index.php/history/prolonged-discrimination-struggle-for-human-rights/state-policies-under-communism

—, “Roma Culture”, Factsheets on Roma, Council of Europe, 2012, http://romafacts.uni-graz.at/index.php/culture/introduction/roma-culture

—, Roma Culture in Past and Present (Sofia: Paradigma, 2012).

—, eds., Studii Romani I (Sofia: Club’90, 1994).

—, eds., Studii Romani II (Sofia: Club’90, 1995).

Nyagulov, Blagovest, “Iz istoriyata na tsiganite/romite v Balgaria (1878-1944) [From the History of Gypsies/Roma in Bulgaria (1878-1944)]”, in Integratsia na romite v balgarskoto obshtestvo [Integration of Roma in Bulgarian Society], ed. by Velina Topalova and Aleksey Pamporov (Sofia: Institut po sociologia pri BAN, 2007), pp. 24-42.

Petrovski, Trajko, Kalendarskite obichai kaj Romite vo Skopje i okolinata [Calendar Customs by Roma in Skopje and Surroundings] (Skopje: Feniks, 1993)

Simon, Gerhard, Die nichtrussischen Völker in Gesellschaft und Innenpolitik der UdSSR (Cologne: Bundesinstitut für Ostwissenschaftliche und Internationale Studien, 1979).

Slavkova, Magdalena, Tsigani evangelisti v Balgaria [Evangelical Gypsies in Bulgaria] (Sofia: Paradigma, 2007).

Soulis, George C., “The Gypsies in the Byzantine Empire and the Balkans in the Late Middle Ages”, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 15 (1961), 141-65.

Stoyanova, Plamena, “Preimenuvane na tsiganite: myusyulmani v Balgariya [Renaming of the Roma: Muslims in Bulgaria]”, in XVII Kyustendilski chtenia 2010, ed. by Christo Berov (Sofia: Istoricheski Fakultet, SU “Climent Ohridski” and Regionalen istoricheski muzei Kyustendil, 2012), pp. 252-68.

Suny, Ronald G., and Terry Martin, eds., A State of Nations: Empire and Nation-Making in the Age of Lenin and Stalin (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002).

Tatarev, Atanas, Romane Somnal gilya [Romani Holy Songs] (Sofia: Sayuz na balgarskite evangelski baptistki tsarkvi, 1936).

Tenev, Dragan, Tristakhilyadna Sofia i az mezhdu dvete voini [Three Hundred Thousand’s Sofia and Me Between Two Wars] (Sofia: Balgarski pisatel, 1997).

Thurfjell, David, and Adrian Marsh, Romani Pentecostalism: Gypsies and Charismatic Christianity (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2014).

Todorov, Nicolay, Balkanskiat grad 15-19 vek: sotsialno-ikonomichesko i demografsko razvitie [A Balkan City, 15th-19th Centuries: Social, Economical and Demographic Development] (Sofia: Nauka i izkustvo, 1972).

Vukanović, Tatomir, Romi (cigani) u Jugoslaviji [Roma (Gypsies) in Yugoslavia] (Vranje: Nova Jugoslavija, 1983).

Archives

Archive of the Ministry of Interior (AMI): Fund 13, op. 1, а.е. 759.

Specialised Library and Studii Romani Archive (ASR): Fund “Shakir Pashov”, f. E; FC, FK; Fund “Istikbal”; Fund “Roma activists” f. J; ASR, Fund Newspapers, f. H; ASR, Fund Romano esi, F.I.

State Agency “Archives”, Department “Tsentralen Darzhaven Arkhiv” (SAA-TsDA): Fund 1Б, op. 6; а.е. 235; Fund 1Б, op. 8, a.e. 596; Fund 1Б, op. 25, a.e. 71; TsDA: Fund 1Б, op. 8, а.е. 596, l. 69; TsDA: Fund 264k, op. 2, а.е. 8413, l. 1-3,6 -12, 14, 28-29.

State Agency “Archives”, State Archive — Blagoevgrad (SAA-SAB): Fund 109, op. 1, a.e. 42.

State Agency “Archives”, State Archive — Varna (SAA-SAV): Fund 1440.

Newspapers

Svetilnik [Candelabrum]. Edition of the Evangelical Baptist Mission among Gypsies in Bulgaria. Edited by Pastor Petar Minkov. Lom, 1927, No. 1.

Izvestia na tsiganskata evangelska misia [Bulletin of the Gypsy Evangelical Mission]. Edited by Pastor Petar Minkov. Lom, 1933, Nos. 1-3.

Terbie [Education]. An organ of the Muhammedan National Educational Organisation. Edited by Shakir Pashov. From its 6th issue it became the body of the General Muhammedan National Cultural and Enlightening Union. Edited by Shakir Pashov. Sofia, 1933-1934, ann. I, No. 1; ann. II, Nos. 2-7.

Romano esi [Gypsy Voice, in Romani]. An organ of The All Cultural and Educational Organisation of the Gypsy Minority in Bulgaria. Edited by Shakir Pashov and, after No. 10, by Mustafa Aliev. Sofia, ann. I, 1946, Nos. 1-4; ann. II, 1947, Nos. 5-8; ann. III, 1948/1949, Nos. 9-11.

Nevo Drom [New Way, in Romani]. An organ of The All Cultural and Educational Organisation of the Gypsy Minority in Bulgaria. Edited by Lubomir Aliev. Sofia, ann. I, 1949, Nos. 1-2; ann. II, 1950, No. 3.

Neve Roma [New Gypsies, in Romani]. An organ of the Gypsy People‘s Community and Library 9th of September Centre. Edited by Sulyo Metkov. Sofia, ann. I, 1957, Nos. 1-12.

1 Kirsten Martins-Heuss, Zur mythischen Figur des Zigeuners in der deutschen Zigeunerforschung (Frankfurt: Hagg Herchen, 1983), p. 8.

2 Donald Kenrick, The Romani World: A Historical Dictionary of the Gypsies, 3rd edn. (Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press, 2007), p. 386.

3 EAP067: Preservation of Gypsy/Roma historical and cultural heritage in Bulgaria, http://eap.bl.uk/database/overview_project.a4d?projID=EAP067, and EAP285: Preservation of Gypsy/Roma historical and cultural heritage in Bulgaria ‒ major project, http://eap.bl.uk/database/overview_project.a4d?projID=EAP285

4 The historical background of these events is described in general works devoted to Bulgarian history in the period under review. Frederick B. Chary, The History of Bulgaria (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2011); R. J. Crampton, Bulgaria (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990); and Raymond Detrez, Historical Dictionary of Bulgaria (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2006).

6 See http://eap.bl.uk/database/results.a4d?projID=EAP067 and http://eap.bl.uk/database/results.a4d?projID=EAP285

7 The original of the statute was not discovered in Bulgarian archives. It is available only in published book form: Anonymous, Ustav na Egiptyanskata narodnost v gr. Vidin [Statute on the Egyptian Nation in the Town of Vidin] (Vidin: Bozhinov & Konev, 1910). A copy of the book is preserved in the Specialised Library within the Studii Romani Archive (ASR), and the digitised version is forthcoming. All translations are ours unless otherwise stated.

8 In the Ottoman Empire, the Roma had citizenship status, were classified according to their ethnicity and had their own economic niches and position in the society. See Elena Marushiakova and Vesselin Popov, Gypsies in the Ottoman Empire (Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press, 2001); Faika Çelik, “Exploring Marginality in the Ottoman Empire: Gypsies or People of Malice (Ehl-i Fesad) as viewed by the Ottomans”, EUI Working Paper RSCAS, 39 (2004), 1-21; and Faika Çelik, “‘Civilizing Mission’ in the Late Ottoman Discourse: The Case of Gypsies”, Oriente Moderno, 93 (2013), 577-97.

9 In the first paragraph of the statute preceding Article 3, local variants of the Ottoman administrative term çeribaşi are used: tseribashi and malebashi.

10 Anon., Ustav na Egiptyanskata narodnost v gr. Vidin, pp. 4 and 6.

11 Ibid., p. 15.

12 Marushiakova and Popov, Gypsies in the Ottoman Empire, pp. 39-41.

13 During the Ottoman Empire, mahalla referred to a residential ethnic neighbourhood. For more information about Ottoman urban structure, see Nicolay Todorov, Balkanskiat grad 15-19 vek: sotsialno-ikonomichesko i demografsko razvitie [A Balkan City, 15th-19th Centuries: Social, Economical and Demographic Development] (Sofia: Nauka i izkustvo, 1972).

14 For more detail on the functioning of the Ottoman system in regard to religious and ethnic communities (including the Roma), see Christians and Jews in the Ottoman Empire: The Functioning of a Plural Society, ed. by Benjamin Braude and Bernard Lewis, 1 (New York: Holmes and Meier, 1982); Marushiakova and Popov, Gypsies in the Ottoman Empire; and Reşat Kasaba, A Moveable Empire: Ottoman Nomads, Migrants, and Refugees (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2009).

15 Anon., Ustav na Egiptyanskata narodnost, Article 16, p. 10.

16 Ibid., Article 23, p. 13.

17 Ibid., Article 19, pp. 11-12.

18 Marushiakova and Popov, Gypsies in the Ottoman Empire, pp. 16, 17 and 26.

19 George C. Soulis, “The Gypsies in the Byzantine Empire and the Balkans in the Late Middle Ages”, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 15 (1961), pp. 141-65.

20 For examples and texts of numerous etiological legends, see Studii Romani I, ed. by Elena Marushiakova and Vesselin Popov (Sofia: Club’90, 1994), pp. 16-47; Studii Romani II, ed. by Elena Marushiakova and Vesselin Popov (Sofia: Club’90, 1995), pp. 22-45; and Elena Marushiakova and Vesselin Popov, “Myth as Process”, in Scholarship and the Gypsy Struggle: Commitment in Romani Studies, ed. by Thomas Acton (Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press, 2000), pp. 81-93.

21 Anon., Ustav na Egiptyanskata narodnost, Article 18, p. 11.

22 For more on the cult of St George and its dissemination among Roma in the Balkans, see Elena Marushiakova and Vesselin Popov, Gypsies (Roma) in Bulgaria (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1997), pp. 136-37; Elsie Ivančić Dunin, Gypsy St. George‘s Day – Coming of Summer. Romski Gjurgjovden. Romano Gjurgjovdani-Erdelezi. Skopje, Macedonia 1967-1997 (Skopje: Združenie na ljubiteli na romska folklorna umetnost “Romano ilo”, 1998); Trajko Petrovski, Kalendarskite obichai kaj Romite vo Skopje i okolinata [Calendar Customs of the Roma in Skopje and Surroundings] (Skopje: Feniks, 1993), pp. 142-47; and Tatomir Vukanović, Romi (cigani) u Jugoslaviji [Roma (Gypsies) in Yugoslavia] (Vranje: Štamparija „Nova Jugoslavija“, 1983), pp. 276-79.

23 Elena Marushiakova and Vesselin Popov, “The Vanished Kurban: Modern Dimensions of the Celebration of Kakava/Hidrellez Among the Gypsies in Eastern Thrace (Turkey)”, in Kurban on the Balkans, ed. by Bilijana Sikimić and Petko Hristov (Belgrade: Institute of Balkan Studies, 2007), pp. 33-50.

24 Some of them even have two names: one Muslim and one Christian. Such inter-religious names among the Roma are documented from Ottoman times, e.g. in the tax register of 1522-1523 (Marushiakova and Popov, Gypsies in the Ottoman Empire, pp. 30-31). This practice of using inter-religious names in Bulgaria was reinforced after the break-up of the Ottoman Empire, which resulted in several waves of forced name changes from Muslim to Bulgarian Christian ones. Even today we can observe the practice of using double names, as in a Rom with both a Muslim and a Christian name. See Hristo Kyuchukov, My Name Was Hyussein (Honesdale, PA: Boyds Mills Press, 2004); Marushiakova and Popov, Gypsies (Roma) in Bulgaria; Ulrich Büchsenschütz, Maltsinstvenata politika v Balgaria. Politika na BKP kam evrei, romi, pomatsi i turtsi 1944-1989 [The Minority Policies of the Bulgarian Communist Party towards Jews, Roma, Pomaks and Turks (1944-89)] (Sofia: IMIR, 2000); and Plamena Stoyanova, “Preimenuvane na tsiganite: myusyulmani v Balgariya [Renaming of the Roma: Muslims in Bulgaria]”, in XVII Kyustendilski chtenia 2010, ed. by Christo Berov (Sofia: Istoricheski Fakultet, SU “Climent Ohridski” and Regionalen istoricheski muzei Kyustendil, 2012), pp. 252-68.

25 Marushiakova and Popov, Gypsies (Roma) in Bulgaria, pp. 89-90.

26 For a discussion of the scale of Roma participation in the Bulgarian army, see Velcho Krastev and Evgenia Ivanova, Ciganite po patishtata na voynata [Gypsies on the Road of the War] (Stara Zagora: Litera Print, 2014).

27 EAP067/1/6; ASR, Fund “Shakir Pashov”, f. C 4 a-d.

28 The manuscript was digitised in frames for our EAP067 project (EAP067/1/11); ASR, Fund “Shakir Pashov”, f. E 1-216.

29 EAP067/1/6.

30 Fund “Shakir Pashov”, f. C 4 d.; see also Lilyana Kovacheva, Shakir Pashov. O Apostoli e Romengoro [Shakir Pashov: The Apostle of the Roma] (Sofia: Kham 2003).

31 ASR, Fund “Shakir Pashov”, f. E 101-102. For more details on the suspension of the electoral rights of the majority of Roma in Bulgaria in 1901, and the struggles to defend their constitutional rights, see Marushiakova and Popov, Gypsies (Roma) in Bulgaria, pp. 29-30.

32 ASR, Fund “Shakir Pashov”, f. E 99-100.

33 Ibid.

34 TsDA: Fund 1Б, op. 8, а.е. 596, l. 69. See also: Nyagulov, Blagovest, “Iz istoriyata na tsiganite/romite v Balgaria (1878-1944) [From the History of Gypsies/Roma in Bulgaria (1878-1944)]”, in Integratsia na romite v balgarskoto obshtestvo [Integration of the Roma in Bulgarian Society], ed. by Velina Topalova and Aleksey Pamporov (Sofia: Institut po sotsiologia pri BAN, 2007), pp. 24-42.

35 For more details, see Elena Marushiakova and Vesselin Popov, “Zigeunerpolitik und Zigeunerforschung in Bulgarien (1919-1989)”, in Zwischen Erziehung und Vernichtung. Zigeunerpolitik und Zigeunerforschung im Europa des 20. Jahrhunderts, ed. by Michael Zimmermann (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 2007), pp. 132-33.

36 TsDA: Fund 264k, op. 2, а.е. 8413, l. 1-3,6, 14; See also: Nyagulov, “Iz istoriyata na tsiganite/romite v Balgaria”, p.36

37 ASR, Fund “Shakir Pashov”, f. E 101-10.

38 ASR, Fund “Shakir Pashov”, f. C 4a.

39 ASR, Fund “Shakir Pashov”, f. E 101-10; ASR, Fund “Shakir Pashov”, f. C 4a.

40 ASR, Fund “Shakir Pashov”, f. C 4a.; ASR, Fund “Shakir Pashov”, f. E 101-10.

41 ASR, Fund “Shakir Pashov”, f. E 101-10, ASR, Fund “Shakir Pashov”, f. C 4a. This is also confirmed in a statement from the Blagoev Regional Council regarding the “Personal People’s Pension” issued to Pashov in 1967 (ASR, Fund “Shakir Pashov”, f. C 5a, 5b).

42 TsDA: Fund 264k, op. 2, а.е. 8413, l. 7-12, 14, 28-29

43 ASR, Fund “Shakir Pashov”, f. E 101-10. The newspaper Terbie was published in Sofia from 1933-1934; the preserved copies are: ann. I, No. 1; ann. II, No. 2-7.

44 ASR, Fund “Shakir Pashov”, f. E 103-104.

45 ASR, Fund “Shakir Pashov”, f. E 101-10.

46 Ibid. For more on the famous pub By Keva, see Dragan Tenev, Tristakhilyadna Sofiya i az mezhdu dvete voini [Three Hundred Thousand’s Sofia and Me Between Two Wars] (Sofia: Balgarski pisatel, 1997), pp. 225-27 and 233-35; and Raina Kostentseva, Moyat roden grad Sofia. V kraya na XIX nachaloto na XX vek i sled tova [My Home City of Sofia: At the End of the 19th Century, the Beginning of the 20th Century and After] (Sofia: Riva, 2008), p. 148.

47 ASR, Fund “Shakir Pashov”, f. E 101-10.

48 Ibid.

49 TsDA: Fund 264k, op. 2, а.е. 8413, l. 1-3,6, 14; see also: Nyagulov, “Iz istoriyata na tsiganite/romite v Balgaria”, p. 36

50 ASR, Fund “Shakir Pashov”, f. E 99-100; and ASR, Fund “Shakir Pashov”, f. C 4a, 4b.

51 ASR, Fund “Shakir Pashov”. Numerous documents of this kind are preserved in the ASR and are currently being processed.

52 EAP285/1/1; ASR Fund “Shakir Pashov”, f. K 1-5. The statute is not dated, but was probably prepared in 1945 or 1946; see also the text below.

53 EAP067/7/1-9; ASR Fund “Shakir Pashov”, f.I.

54 Marushiakova and Popov, “Zigeunerpolitik und Zigeunerforschung in Bulgarien”, pp. 151-52.

55 For more on the policy of “korenizatsiia”, see Gerhard Simon, Die nichtrussischen Völker in Gesellschaft und Innenpolitik der UdSSR (Cologne: Bundesinstitut für Ostwissenschaftliche und Internationale Studien, 1979); and A State of Nations: Empire and Nation-Making in the Age of Lenin and Stalin, ed. by Ronald G. Suny and Terry Martin (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002). For more on the policy towards the Roma in the Soviet Union in the same period, see Marushiakova and Popov, “Soviet Union Before World War II”, Factsheets on Roma, Council of Europe, 2008, http://romafacts.uni-graz.at/index.php/history/second-migration-intensified-discrimination/soviet-union-before-world-war-ii

56 ASR, Fund “Shakir Pashov”, f. C4.

57 Marushiakova and Popov, “Zigeunerpolitik und Zigeunerforschung in Bulgarien”, pp. 151-52. This is not a paradox: eastern European countries de facto did not follow the same principles in matters of internal policy. While there was superficial unity on the ideological level, since each country adhered to the “principles of Marxism-Leninism”, in practice each country interpreted these principles in its own way and conducted its own national policy, including its policy towards the Roma population.