8. Sacred boundaries: parishes and the making of space in the colonial Andes

© Gabriela Ramos, CC BY http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0052.08

The all-encompassing influence of the Catholic Church in Spanish America is a compelling reason to collect, preserve and study ecclesiastical records in any Latin American country. Church archives house documents that allow us to learn the history of people of all walks of life throughout the centuries. Ecclesiastical archives often provide us with the only clues to the lives of many anonymous men and women.

The Spanish Crown legitimised its sovereignty over the New World through its commitment to convert its inhabitants and future subjects to Christianity. To accomplish this end, significant changes were brought upon the indigenous population. Using the digitised collections of the Huacho diocese in Peru,1 this chapter studies the agents and circumstances behind the formation of parishes and parish jurisdictions. The essays investigates the meaning of parish boundaries, how these boundaries were created, how both clergy and parishioners perceived them, and in what ways such boundaries contributed to shaping the colonial order. Although ecclesiastical legislation — especially that produced by the Council of Trent — provided guidance for the establishment of parishes, local circumstances and the overlapping of authorities and jurisdictions made parish boundaries the subject of controversy and contestation.2

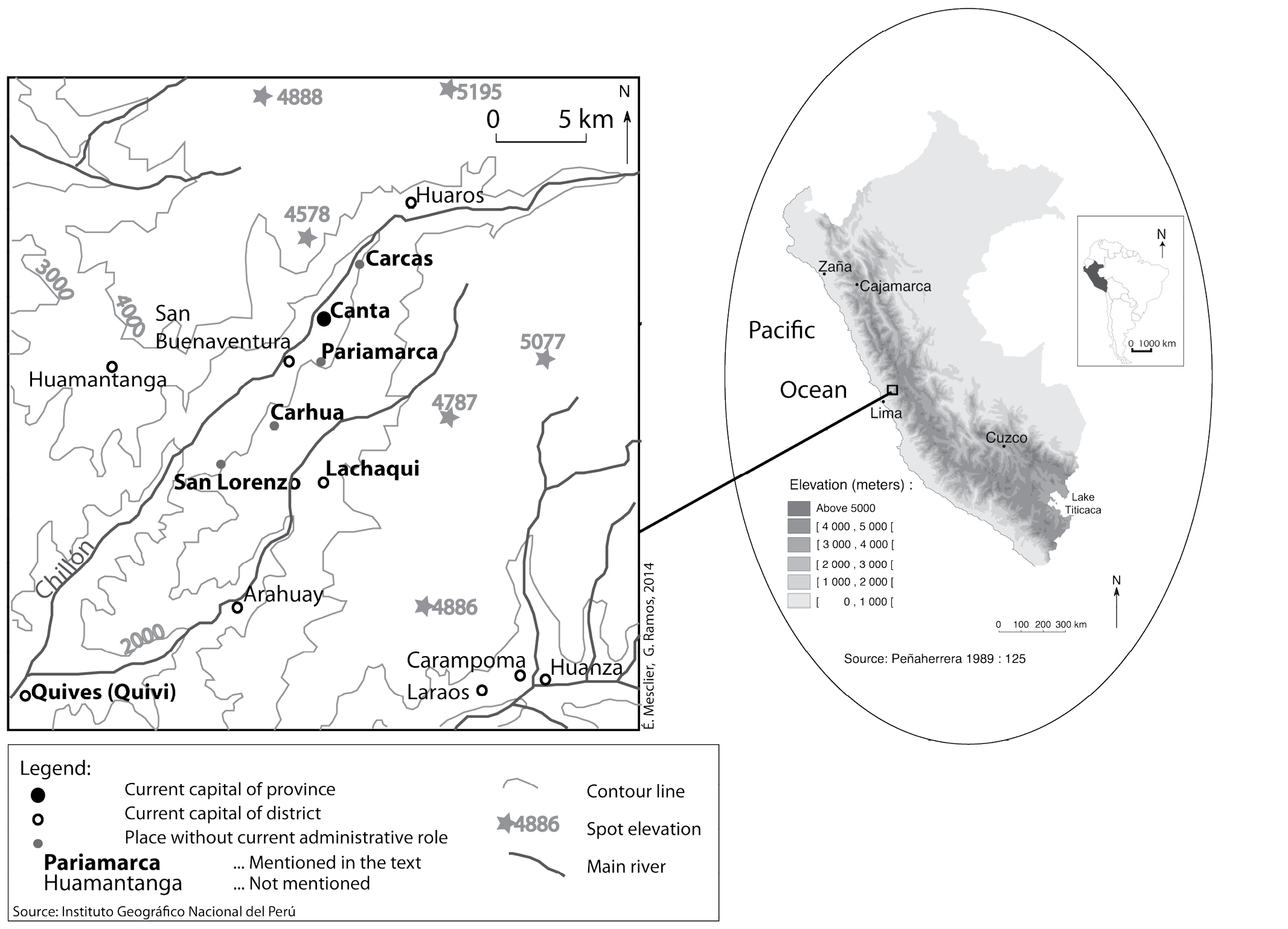

Fig. 8.1 Map of the Valley of Canta, Peru, by Évelyne Mesclier, CC BY.

The extent to which towns and urban life were widespread in the pre-Columbian Andes is still a subject of discussion among scholars.3 Although hundreds of years before the Spanish conquest ancient Andeans built impressive urban centres, most of them had primarily ceremonial and administrative functions. There is solid evidence suggesting that the state had a fair degree of control over population movement, and that not everyone was allowed to live in towns and cities. Temporary migrations were nevertheless common across the ecologically diverse Andean landscape. The inhabitants of a given area were able to claim access to land and to other resources in places situated at considerable distance, and at lower or higher altitudes from their usual settlements.4 To assert their control over a recently conquered region or to increase agricultural production, the Inca, and possibly also their predecessors, usually moved entire populations even across considerable distances.5 Religious life in the Andes demanded a continuous interaction with the surrounding environment. To secure their livelihoods, Andean people also travelled variable distances to perform religious rituals honouring their ancestors and several other protective deities scattered in the landscape.6 It is possible to assert that mobility in the Andes was a norm, that sacred places were numerous, and that many settlements were neither large, nor permanent.

Spanish colonists took advantage of established Inca state governmental practices, even if at the same time colonial officials endeavoured to substantially modify key cultural and political patterns such as the use of the space. Mobility and dispersal were issues Spanish officials thought necessary to address in order to achieve political control over the indigenous population, to gain access to indigenous labour, to facilitate Christian indoctrination, and to collect tribute and taxes. The Spanish empire’s economic, political and evangelising ends demanded a reorganisation of the space, following European ideas about what constituted a civilised, Christian life.7 Urban life provided the model Spanish colonisers set out to apply in the Andes and elsewhere in Spanish America.8

Andean colonial cities and towns were set up following a grid layout, a format that provided a sense of order and allowed for the easy identification of the quarters into which urban centres were divided. Although the grid plan evoked the idea of regularity, uniformity was not the ideal pursued. A strong sense of hierarchy dominated the design the Spanish imposed on towns and cities throughout their New World domains. At the centre of each city, town or village, was the plaza or public square and, at its heart, stood the pillory, symbolising royal justice. The church, always the largest and tallest building on the central square, was a glaring sign of Catholicism’s prevalence; the city council building and the houses of the prominent local officials and citizens usually surrounded the plaza. Although this description corresponds to the leading cities, any traveller journeying across Spanish America would observe that the model was applied in every urban settlement independently of its size and importance.

In the years following the arrival of the Spanish, a large proportion of what later became the Peruvian viceroyalty was immersed in wars between bands of Spanish conquistadors fighting over the conquest booty. Some Spaniards professed their loyalty to the king, while a few others were bold and ambitious enough to consider appropriating the wealth of Peru for themselves and installing a new monarchy in alliance with an Inca faction. Years of generalised instability caused by what the historiography knows as “The Civil Wars” delayed the organisation of a government — actually, the first viceroy to arrive in Peru was assassinated by one of the Spanish warring factions — while the few missionaries who were not themselves involved in the fighting failed to make much progress in this highly toxic and chaotic setting. Itinerant missionaries travelled throughout certain Andean regions, but no formal church organisation was possible until after the wars were over, when several of the first conquistadors and many of their rebel followers were executed, and a crown representative acknowledged by most, together with the appointed bishop, were able to act. Therefore, ecclesiastical divisions known as parishes and doctrinas did not exist until approximately thirty years after the arrival of the first Spaniards in the Andes.9

In the early modern period, Peru’s wealth was usually represented to European audiences by accounts of the immense quantities of silver and gold enclosed in its temples, palaces and tombs, or found in mines such as Potosí.10 While these riches attracted both conquistadors and migrants, most of them soon realised that, although the stories about the abundance of precious metals were no fabrication, the land’s main source of wealth was its people. The Incas and their ancestors valued gold and silver for their appearance but, since they assigned them no monetary value, wealth consisted not in owning considerable amounts of precious metals, but in having as many people as possible under one’s control.11 Wealth involved power over labour, and also over the labourers’ minds, since submission was crucial to validate power.

This idea of wealth in the Andes did not become entirely obsolete after the Spanish conquest. The civil wars that ravaged the region soon after the military conquest were caused by disputes over the control of people. In compensation for their participation in the expeditions leading to the subjugation of the Inca Empire, the first conquistadors were granted encomiendas. Known as repartimiento in late medieval Iberia, once transplanted to the New World, the encomienda was significantly transformed: it entitled its beneficiary to the labour and even tribute in kind of a group of people who inhabited or claimed domain over a territory, shared kin ties, and acknowledged the authority of their leaders or chiefs but, in contrast with the Iberian repartimiento, the encomendero’s12 domain was over people, not over their land.13 In return, encomenderos were committed to ensuring the religious indoctrination of the people under their charge, through enlisting priests and paying their salaries. The first encomenderos were convinced that their grants or encomiendas were perpetual and thus they could pass them over to their successors. However, at the time of the Spanish conquest of Peru, the encomienda was already under severe criticism, since it was considered the main culprit for huge population losses in the Caribbean and Mexico.14

Denunciations against the encomienda and concerns raised over the legitimacy of Spain’s sovereignty claims over the inhabitants of the New World were behind the crown’s decision in 1542 to issue the “New Laws” to protect the indigenous population from encomendero abuse and exploitation.15 Asserting royal authority over the seigniorial system that rested upon the encomienda involved curtailing encomenderos’ power by ending the perpetuity of encomiendas. The New Laws of 1542 that sparked vociferous protest in Mexico and triggered armed confrontation in Peru demonstrate the degree to which control over people was widely acknowledged as both a crucial source and a symbol of wealth.

In colonial Spanish America, a chain of mutual obligations linked power and its different incarnations — the pope as God’s representative, the Spanish king, a number of Spanish subjects and officials, the Catholic clergy and Indian chiefs and headmen — to indigenous labour and religious conversion. The papal bull of 1493, which granted the Spanish sovereign with dominion over the New World, entrusted the Spanish crown with the conversion of the inhabitants of the Americas. Through the Royal Patronage, the Spanish king was committed to support the Catholic church and all missions to the New World.16 In exchange, he was entitled to make ecclesiastical appointments within his domains: from parish clergy to archbishops.

We have already seen how the encomienda fitted within this scheme: indigenous peoples gave their labour and tribute — in kind and/or in cash — to the encomendero in return for religious indoctrination. Priests appointed to evangelise the Indians received the sínodo, a proportion of the Indian head tax or tribute, in payment for their services. Indian chiefs were in charge of collecting the head tax from their subjects and handing it to their encomendero. After the encomienda was suppressed or disappeared, Indian chiefs continued collecting the tribute transferring it now to Spanish magistrates known as corregidores. The funds to pay corregidores’ salaries also came from the indigenous head tax. Indigenous leaders or chiefs, known in the Andes as caciques17 or curacas, were entrusted with assuring that their subordinates pay tax, attend mass and catechism lessons, and provide their labour whenever they were requested for the benefit of the king or his representatives, the church, Spanish miners and farmers, or “the common good” such as when they were required to labour in public works. In return for their governmental duties and their cooperation, curacas were exempted from paying tribute, an acknowledgement of their condition as “nobles”. As the crown’s vassals, curacas and their subjects were entitled to the king’s protection.

As a result of the circumstances explained above, offices and jurisdictions frequently overlapped. There was no question that the Indians had to be evangelised. Even a number of curacas agreed, if admittedly many did so for strategic and survival reasons. However, because of the Royal Patronage and the interwoven obligations and functions already described, decisions leading to the establishment of parishes and doctrinas involved the intervention of other agents in addition to the representatives of the Catholic church.

The establishment of parishes and doctrinas

The circumstances surrounding the creation of new jurisdictions throughout the Andes during the colonial period and beyond remain surprisingly understudied. Scholars have focused on the formal and legal underpinnings of reducciones.18 Reducciones were settlements modelled following a grid plan, where the indigenous population were forced to move since Spanish officials thought that population dispersal was not favourable to their good government and religious indoctrination. The ideas, conflicts and negotiations behind the formation of reducciones need further attention. In the Peruvian Andes, although Spaniards sought to create reducciones a few years after their arrival, a sweeping plan to implement them gained momentum during the rule of viceroy Francisco de Toledo (1569-1581), to the point that today the idea of reducción is often closely associated with his name.19 Because reducciones were meant to ease the religious conversion of the indigenous population, the presence of churches within them is normally assumed, but the story of the shaping of ecclesiastical jurisdictions — in other words, the creation of a complex hierarchy of parishes and chapels and their connection with reducciones — needs further scrutiny.

In the sixteenth century, the Council of Trent saw it necessary to reform parishes. The reforms aimed at achieving a more effective presence of the secular church in both cities and countryside. The council mandated that bishops should live in their dioceses and the clergy should settle closer to, and interact regularly with, their flocks. If a parish priest was unable to tend to the needs of the population — either because of their numbers, their dispersal, or both — it was imperative to set up new jurisdictions. The bishops attending the Council of Trent anticipated that these reforms were likely to elicit resistance among parish priests concerned about the imminent and possibly substantial cuts to their income and weakening of their influence, since the economic interest and political importance of a parish depended heavily on the number of people within its boundaries. The council decrees advised the bishops to carry on establishing new parishes regardless of the opposition.20

Population, territory and boundaries

The circumstances behind the formation of the most elementary ecclesiastical jurisdictions or, more precisely doctrinas, in the colonial Andes are varied and not always easy to elucidate. Repartimientos — social units formed by family groups related to each other through kin ties, often subdivided in smaller units, and each with its own leaders — were at the origins of several doctrinas, possibly established by missionaries belonging to the regular clergy.21 This means that in several cases pre-conquest indigenous settlements could have constituted the initial places for the establishment of primitive churches or sites of worship and indoctrination. The First Lima Council, presided over by the Dominican friar Jerónimo de Loayza in 1551, referred to an already completed partition of the population and territory between the religious orders. The council advised the regular clergy to set up their convents in the best, most important or most populated region possible (en la mayor comarca) within the province under their charge.22 In other instances encomiendas and pre-Toledan reducciones were the sites of the first Indian parishes.

The bishops provided guidance to priests and missionaries on how to select the places where churches should be built: the churches should be established in settlements where the leading indigenous chiefs had their main residence, and which had the largest population. The ruling was followed by the instruction that missionaries should either burn or tear down pre-existing sites of worship and, if the places where these pagan temples and shrines were conveniently located, Christian churches should be built in their stead. These instructions allow us to suggest that a number of new parishes were in fact erected on pre-Columbian indigenous settlements. To signal the distinctiveness of the new places of worship, priests were advised to acquire works of art to make the main churches attractive and worthy of gaining the people’s appreciation. In smaller and secondary settlements, missionaries were to build churches of modest dimensions but no less dignified and, if enough people and means of support to the parish were not available, to set up a chapel or at the very least erect a cross.23

Although repartimientos are often described as primarily involving people and only secondarily territory, the circumstances behind the establishment of doctrinas, the instructions given to priests on how to organise and conduct indoctrination, and the interactions between priests and parishioners throughout time, suggest that the notion of a clear-cut separation between people and territory is difficult to pin down.24 There was an overlap between repartimiento, encomienda, and doctrina. The notion behind the repartimiento and the encomienda revolved around people acknowledging the authority of a curaca or chief and/or, as explained above, sub-chiefs or principales. The close link between repartimiento and provincia involved the idea of not only population, but also of a territory claimed by those who inhabited it. Early accounts and descriptions penned by chroniclers and travellers, as well as church legislation support this view.25 Local Andean populations also acknowledged salient features in the landscape like mountains, caves, lakes and rock formations, as well as tombs and funeral monuments as markers signifying their domain over a territory.26

The idea that the jurisdiction of a parish involved people but not territory, as if their status was identical to that of repartimientos and encomiendas needs further scrutiny. The Constitutions of the First Lima Council instructed priests on how to indoctrinate the Indians, implying that parishes had territorial jurisdiction: priests were advised to say mass in the most populated town of their doctrinas and to make sure that parishioners living in subsidiary towns were also in attendance. This emphasis on place later shifted to a greater accent on people. The Second Lima Council (1567) ruled that to ensure priests were able to accomplish their obligations, a maximum of 400 married men were to be assigned to a parish.27 Perhaps the drastic population changes experienced across the Andean region due to high mortality rates, displacement, and migration are behind this emphasis on population numbers. Different or shifting understandings concerning the sphere of influence of parish, encomienda, province, and repartimiento led to confusion and eventually to conflict. It should be noted that the equivocal status of parishes concerning their population scope and territorial boundaries was not a phenomenon unique to the Andes.28

While a diocese definitely involved territory — a bishop’s jurisdiction clearly was the territory of his diocese — the intersection between the notions of repartimiento and doctrina, and the emphasis these two entities had on people rather than on place made the latter difficult to pin down but also easier to manipulate. In the Andes, the transformations brought by Spanish colonisation, such as significant population losses and continuous Indian migrations — voluntary and forced, temporary and permanent — added to the difficulty in determining parish or doctrina boundaries.

A petition to close down a Doctrina

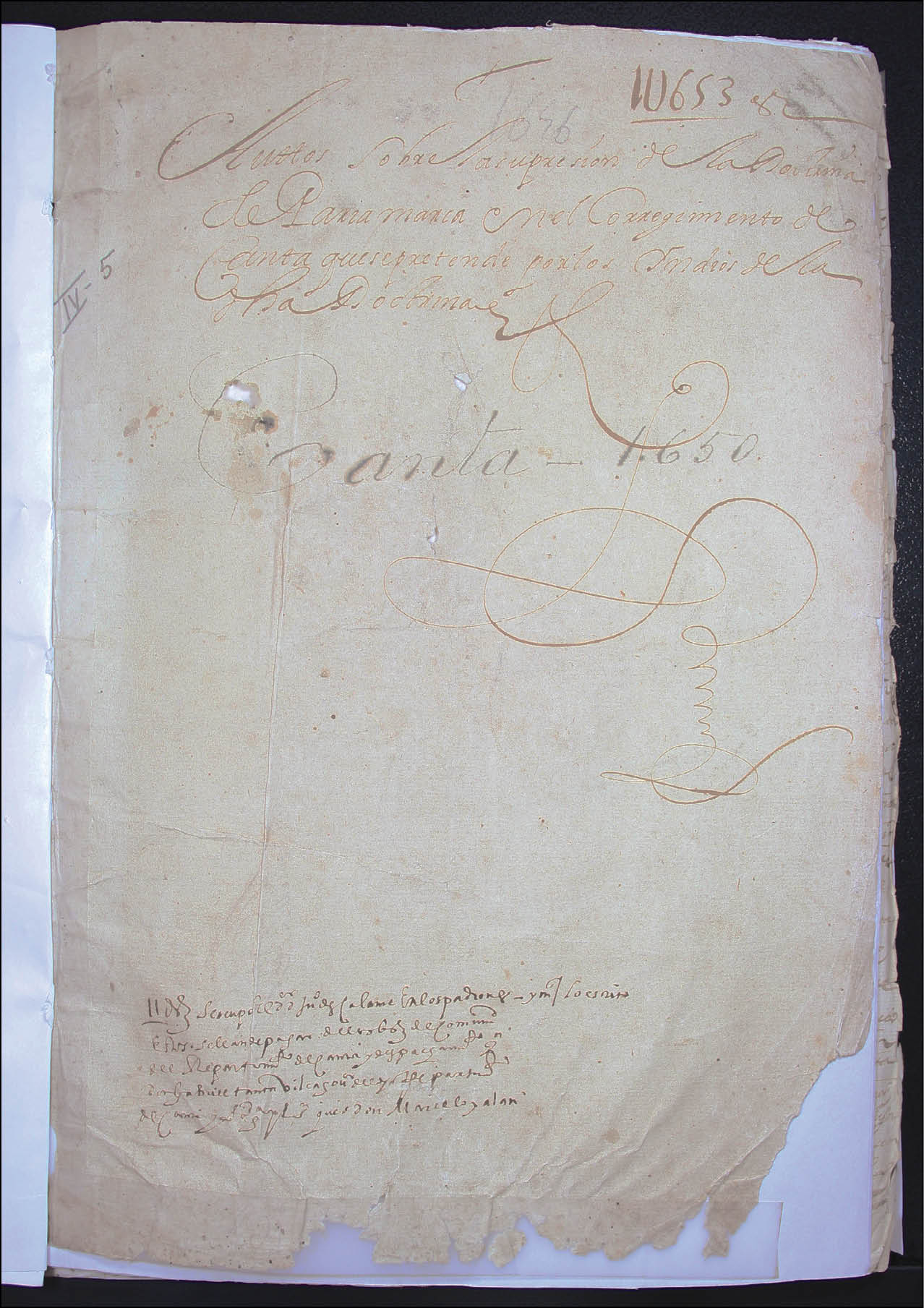

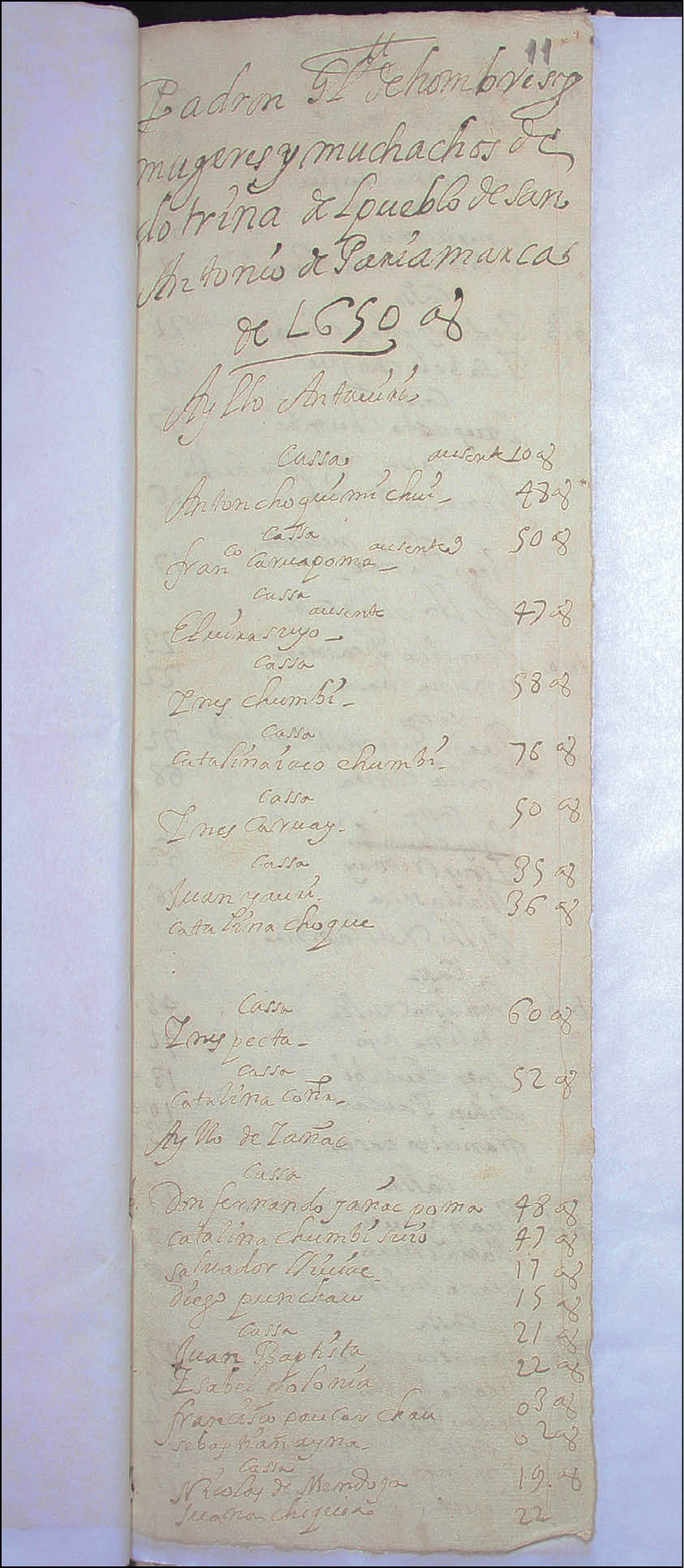

Fig. 8.2 Cover page of the records of the petition to close down

the parish of Pariamarca in the corregimiento of Canta, 1650

(EAP333/1/3/11 image 1), Public Domain.

A file belonging to the historical archives in the Huacho diocese holds a petition of the “headmen” (Fig. 8.2) of the doctrina of Canta, a town in the highlands north of the city of Lima (Fig. 8.1), presented to the archbishop in 1650.29 The petitioners sought to close down the doctrina of Pariamarca.30 Following the filing of the petition, the archbishop started an investigation into the doctrina of Pariamarca. The doctrina, created on an unknown date, was separated from the parish of Canta to facilitate the indoctrination of, and the administration of the sacraments to, the labourers of a textile mill belonging to the repartimiento of Canta. Known as obrajes, textile mills flourished in different areas across Spanish America producing basic fabrics for the local market, namely Indian, African and other low-income consumers. Combining rudimentary technology with harsh working conditions, and normally set up when raw materials were readily available, a number of obrajes across colonial Spanish America prospered by meeting the demand from cities, mining centres, plantations, and other landed properties using slave labour.31

Apparently, the obraje of Pariamarca was economically successful enough to provide the indigenous people of the area with additional income and pay for the priest’s salary. Even though this was clearly advantageous for the Indians, when a fire destroyed the obraje, the corregidor (Spanish magistrate) decided against its reconstruction and ordered the demolition of its premises. The fact that a manufacture that was thriving was given such a sudden and extreme end does not seem reasonable. Regrettably, the sources do not explain the corregidor’s decision, and we can only hypothesise that competitors benefiting from the obraje’s extinction were behind it.

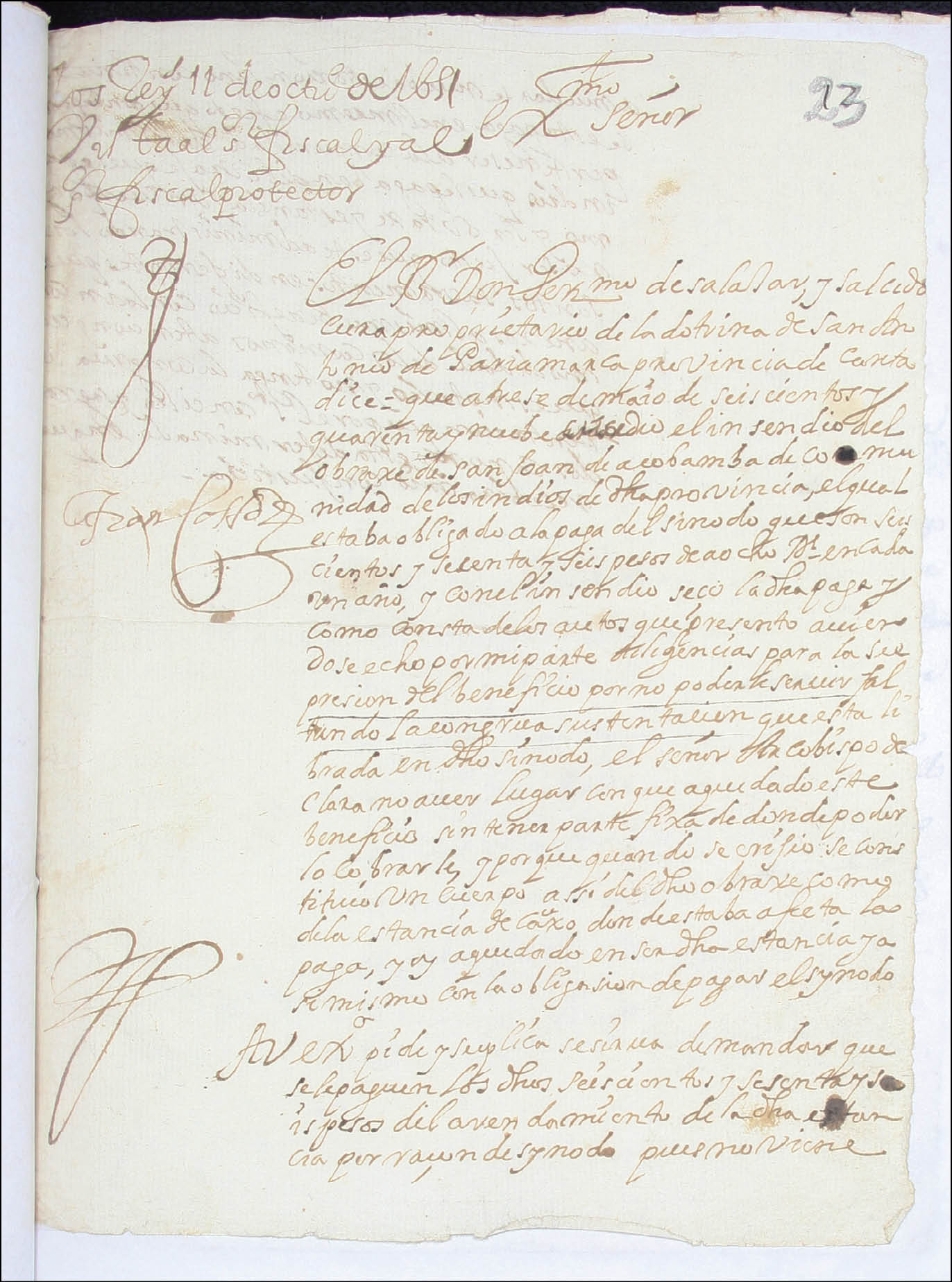

Fig. 8.3 In this letter, Don Gerónimo de Salazar y Salcedo, parish priest of San Antonio de Pariamarca, explains that because of the fire that destroyed the textile mill of Pariamarca, he requested the closing down of the doctrina. Lima, 11 October 1651 (EAP333/1/3/11 image 46), Public Domain.

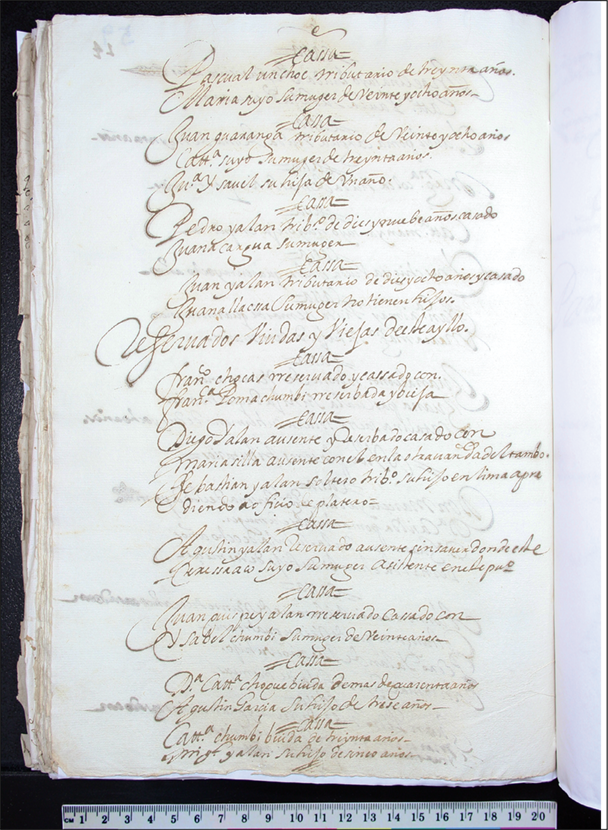

Fig. 8.4 Register of the inhabitants (men, women and youth) of the doctrina of San Antonio de Pariamarca, 1650 (EAP333/1/3/11 image 23), Public Domain.

Deprived of this source of income, the parish priest, don Gerónimo de Salazar, requested the archbishop to close down the doctrina, possibly because he thought that in this way he could leave Pariamarca and get another assignment (Fig. 8.3). The archbishop’s reply requested that Salazar exhibit the parish registers to determine the number of parishioners in Pariamarca (Fig. 8.4). Noting that 500 people were listed, Salazar’s petition was denied. Anticipating the difficulties he would face in collecting his salary with the obraje gone, Salazar filed another petition, this time to the viceregal government, requesting that his salary be funded with the proceeds of a farm — also belonging to the repartimiento of Canta — that had produced the wool used in the now extinct textile mill. Salazar’s petition was successful, but his parishioners opposed the move, arguing that the farm was never meant to fund the priest’s salary (Fig. 8.5). In fact, the indigenous headmen argued that the farm was too far away from Pariamarca, and not within the priest’s reach. According to the headmen, the shepherds labouring at the farm were under the care of the curate of another doctrina where the farm was located. The repartimiento of Canta paid the priest a modest annual sum for performing his pastoral duties.

Salazar left the scene shortly thereafter as he was appointed to another parish. However, his departure did not bring the dispute to an end because the archbishopric stood fast in its decision not to close down the doctrina; in fact, a call for applicants to the vacant post started to circulate. To make the matters worse for the Indians, the government had accepted Salazar’s argument that the doctrina of Pariamarca had been established counting on the proceeds from both the obraje and the farm belonging to the Indians of Canta. Although in the course of the investigation no papers certifying the parish origins were found at the diocesan archives, the government admitted as valid a document that the local scribe of Canta had provided Salazar attesting that the proceedings of the farm had been assigned to the doctrina of Pariamarca from its very beginnings.

To rend legible these and other incidents of the proceedings, it is worth pointing to the issues at stake thus far. First, how many people were necessary to set up a parish? Second, in the context of the doctrina (an Indian parish), did the number of people required to form a parish include everyone, or only taxpayers (tributarios)? Third, were the Indians supposed to pay for the priest’s salary with means other than their taxes?

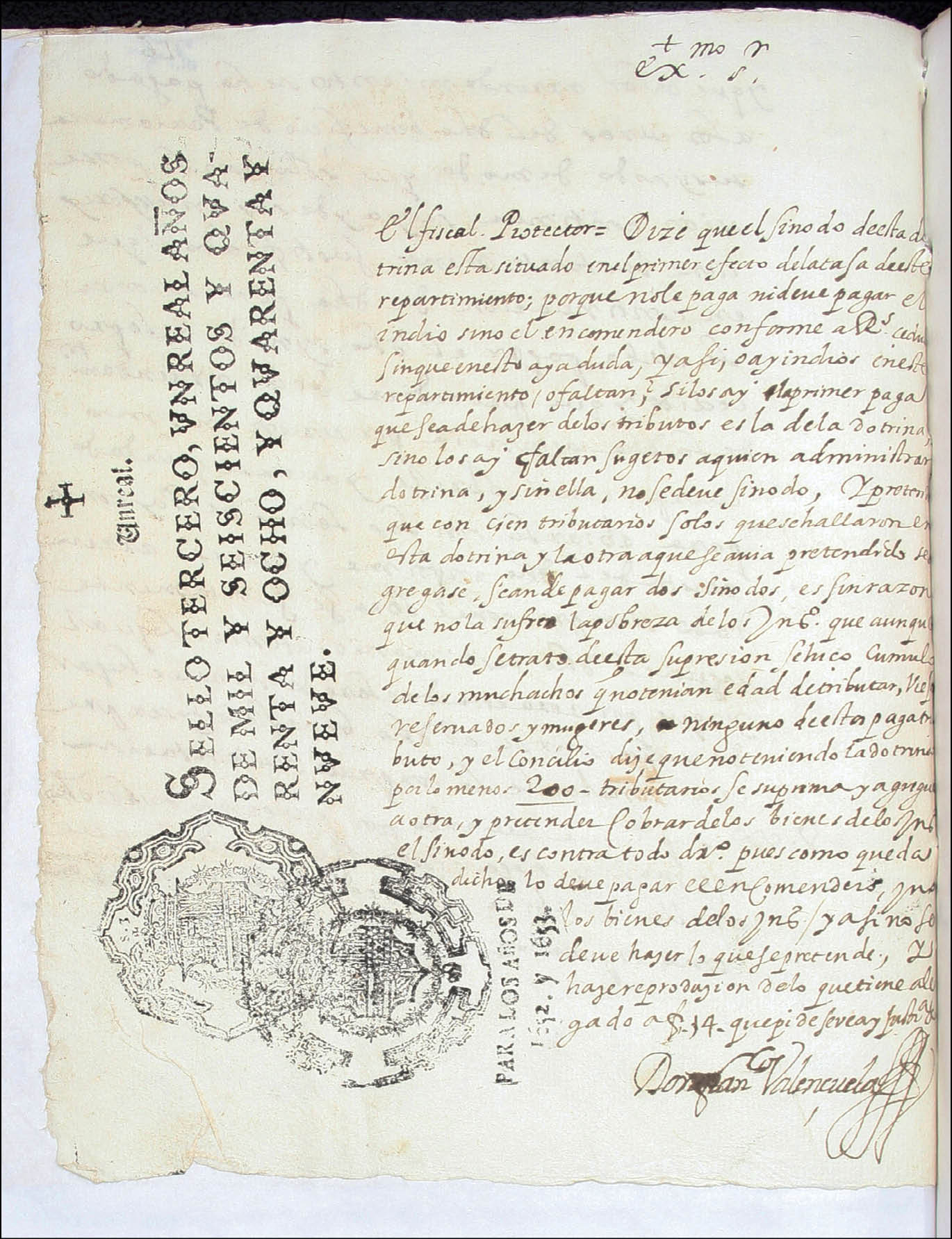

Fig. 8.5 In this letter, the protector of the Indians, don Francisco Valençuela, states that the priest of Pariamarca’s salary cannot be paid with the proceeds of the Indians’ assets. Lima, c. 1651 (EAP333/1/3/11 image 54), Public Domain.

Different viewpoints were advanced to answer these questions. We have seen that when Salazar was asked to show the parish registers, the archbishop’s representative concluded that, since 500 people appeared in them, the continuity of the doctrina was entirely justified. While the Second Church Council (1567) had established that a parish should have no more than 400 married Indians,32 the Third Church Council (1583) decreed that “any Indian town with more than 200 or 300 taxpaying Indians33 should have its own curate, and if there were less than 200 the prelate should make sure that they were permanently settled34 so that they could be adequately indoctrinated and ruled”.35 The Indian headmen of Canta contested the archbishop’s interpretation of Salazar’s parish registers, because although 500 people “small and large” (chicas y grandes) were listed, only 66 of them were taxpayers. While the Indians insisted on this aspect of the council decree (only those who paid tax were to be counted), the archbishop highlighted the words indicating that it was the prelate’s right to decide on the adequate number of people to form a parish.

Three years after the original filing of the petition, the archbishop commissioned the priest of the neighbouring doctrina of Quivi, don Juan de Escalante y Mendoza, to conduct a population count that should include “all the Indians, small and large, men and women, boys and girls as well as those exempted from tax,36 foreigners, and all other residents in the parish of Canta and subsidiary towns, with as much meticulousness as possible”.37 Escalante started his investigation shortly after his appointment by requesting data from three different sources: governmental, ecclesiastic, and indigenous. The first were the records of the latest headcount, from an inspection carried out in 1640, the second were the parish registers, and the third were the tax registers kept in the hands of the repartimiento’s governor.

In his efforts to obtain these documents, Escalante reported encountering resistance. He had to demand the magistrate’s assistant repeatedly for his cooperation. Also, when the Indian governor, don Gabriel Tantavilca, handed him his registers, Escalante found that these contained only the numbers of people classified by towns, but no individual names or details of each household. Furthermore, when Escalante compared the three registers, he noticed that the disparity between them was such that he decided to conduct a population count himself. Escalante commanded the indigenous headmen that on Sunday — when everyone in the doctrina attended mass at the main parish church — the Indian parish officers38 should allow no one to leave whilst Escalante carried out a house-by-house search to see if anyone was hiding. He would then proceed to the headcount.

Escalante may have thought that his authority was uncontested and his plan was infallible, but on Sunday a fire consumed the parish church and he reported that he had instead spent his time with the parishioners trying to save the edifice from complete ruin. Whether the fire was intentional or accidental, Escalante did not allow himself to be distracted by the incident and carried on with the investigation. He ordered Tantavilca and all other Indian officers to assemble all their subjects on Thursday, the day when everyone in the doctrina was meant to attend cathechism instruction, and when he could proceed with the headcount.39

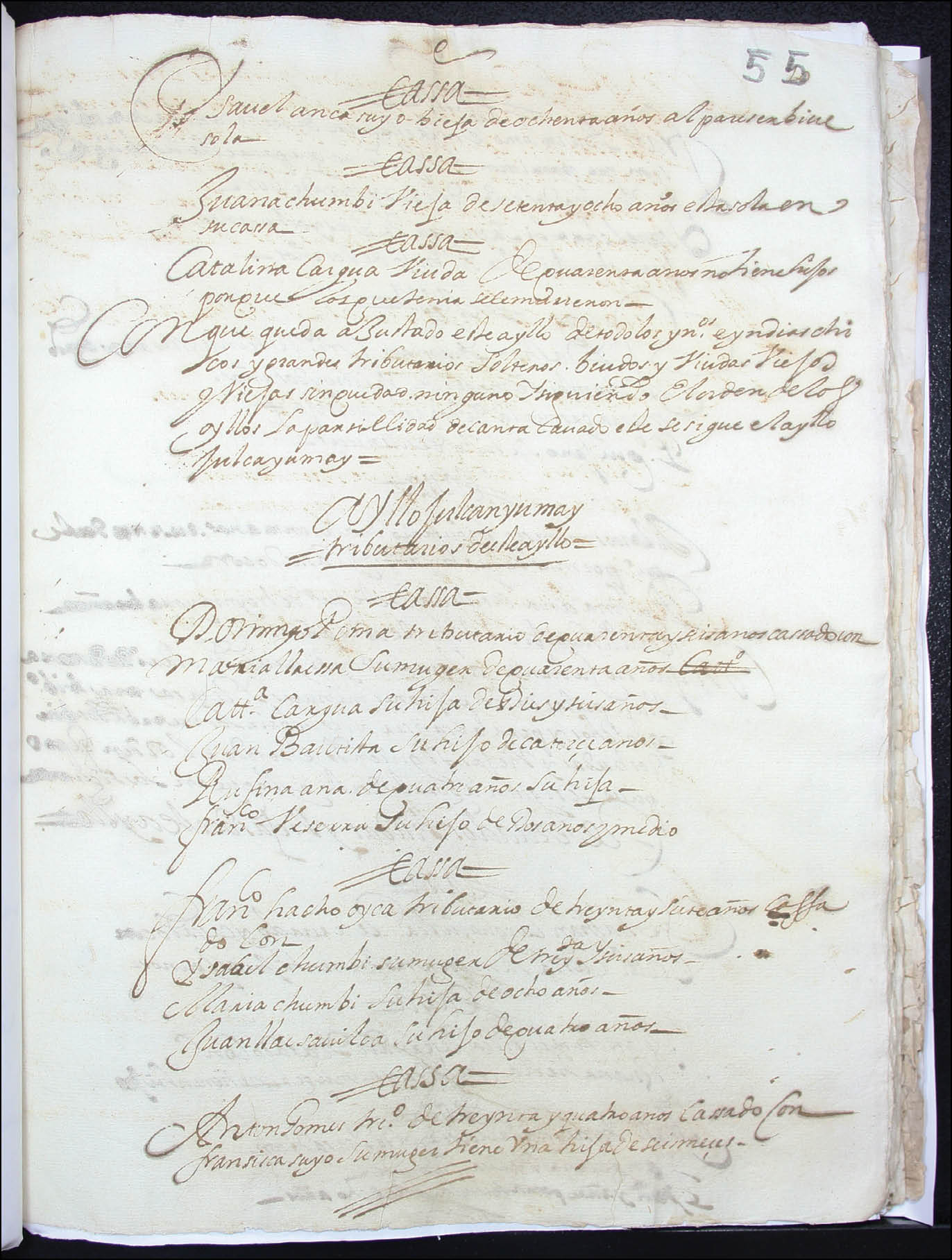

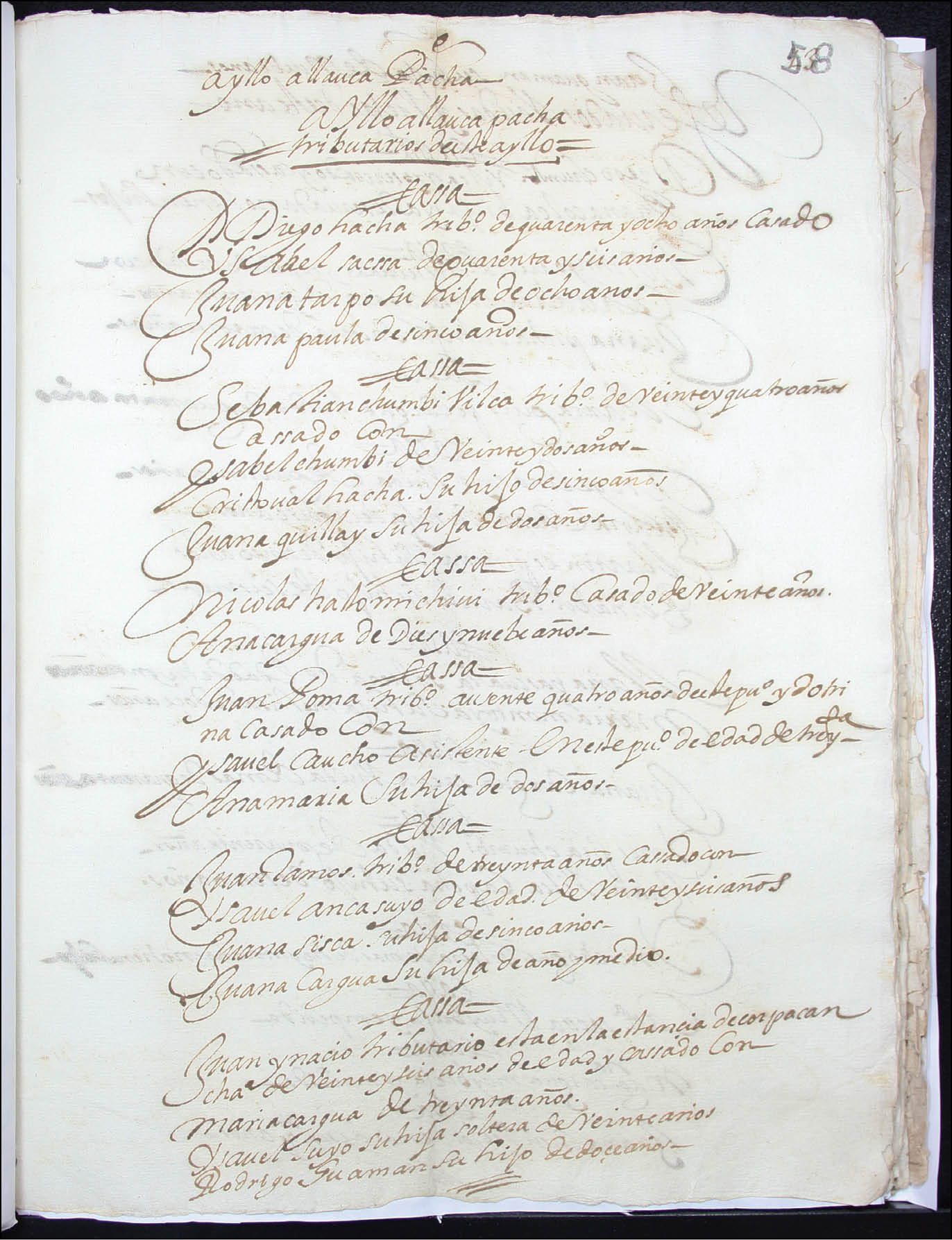

When Escalante was appointed to conduct the investigation into the doctrina, he was asked to be as meticulous as possible, and meticulous he was. The document resulting from the headcount provides to my knowledge one of the most detailed pictures we have of the conditions in which the inhabitants of a rural parish in mid-colonial Peru lived (Figs. 8.6, 8.7 and 8.8). Escalante aimed to describe the repartimiento as a whole, then the two parts40 in which it was divided, and the ayllus or kin groups in which the towns were subdivided. This was followed by a description, household by household, noting the names and estimated age of each household dweller, and — when possible — the whereabouts of those who were absent.

Fig. 8.6 Sample page of the census conducted in 1653 by Juan de Escalante y Mendoza showing part of the headcount of the ayllu (kin group) Julcan Yumay (EAP333/1/3/11 image 107), Public Domain.

Fig. 8.7 Sample page of the census conducted in 1653 by Juan de Escalante y Mendoza, showing part of the headcount of the ayllu Allauca Pacha

(EAP333/1/3/11 image 113), Public Domain.

In 1653, the repartimiento of Canta was organised into two parcialidades: Canta and Loccha.41 Canta was subdivided in eight ayllus while Loccha was much smaller, with only four. Canta had a larger number of head tax payers, or tributarios (forty), as well as more people, with 290 in total. Loccha had 27 head taxpayers and a total of 192 people were counted. Loccha’s smaller number of adult males and population did not mean it had a politically diminished status, because its governor, Tantavilca, was a member of the parcialidad, and presided over the ayllu Curaca Loccha, a name that suggests that this kin group had been holding for a while the office of indigenous governor.

Although outside academia the ayllu is often seen as the fundamental organisational unit in Andean society that has preserved most of its features since pre-Columbian times, historical evidence shows that while the term ayllu persisted throughout times, ayllu members have changed its form and composition to accommodate varying situations. The formation of new ayllus has also been part of this long-established process of social transformation. The image of the ayllu as an institution that hardly admits change is due in great part to the ability of its agents to make adjustments to new circumstances appear as mere reproductions of the old.

The inspection and headcount of the Canta repartimiento provides a good example of the ways in which larger transformations in Andean colonial society can be verified at the local level. Records of inspections of the Canta repartimiento carried out in 1549 and 1553, before Spanish settlements or reducciones were implemented, list ayllu names and numbers that differ from those appearing on the records formed 100 years later. The ayllu names correspond to smaller towns that later became settlements subsidiary to the doctrina of Canta.42 Among the eight ayllus of the Canta parcialidades listed in 1653, the one that stands out as significantly different is that of the plateros tributarios, or silversmith taxpayers. It is known that under Inca rule, artisans were moved between regions to facilitate the formation of new settlements and to make their output more easily available to the elites.43 The inspections records of 1549 and 1553 do not list silversmiths, which suggest that this kin group of artisans was introduced under Spanish colonial rule. This may have been because they were moved to the reducción when Spanish officials set it up in the late sixteenth century, possibly as an attempt to emulate the Inca governmental strategy of transferring specialised workers into a new settlement to accommodate the state’s interests.

The most salient change in the social structure of the doctrina is the inclusion in 1653 of two ayllus of forasteros, or foreigners whose presence considerably modified not only the social, but also the ethnic composition of the community.44 The first forastero ayllu in the 1653 headcount in Canta included non-Indian males, all of them married to local Indian women. The first person on the list was a Spanish man, married to an elite Indian woman. The others were mestizo or mixed race men, a mulatto man, and two single women of African and Indian descent. The second forastero ayllu was formed by Indians that had arrived from other towns and places, some of them as far as Cuzco, in the southeast, and Zaña, on the north coast. All the men in this ayllu were married to local women. Since adult males in these ayllus were exempted from the onerous head tax or paid a lower sum, and were not subject to draft labour (mita), it is likely that these circumstances explain the larger number of people of all ages belonging to this ayllu (98) as compared to all other kin groups in Canta.

The inspection records show a total of 83 taxpayers in the two parcialidades and in the thirteen ayllus of the doctrina. The whole population excluding foreigners was 512.45 When compared to the figures listed 100 years earlier, we note a considerable population decline. When interviewed by the inspectors in 1549, Diego Flores, a Spanish man in charge of the encomendero’s affairs, estimated there were 750 adult males in Canta.46 That the population of Canta had not collapsed entirely in the following decades was probably due to the arrival of new forasteros who, by marrying local women, had gained access to land. Since these foreigners were exempted from paying the head tax or, if they did pay tax this was certainly at a lower rate, they possibly had more opportunities to prosper.47 When added to the registered population, the approximate total number of people living in Canta rose to 610. Although additional evidence would be necessary to better understand their place within the community, it would be safe to say that forasteros contributed with their labour to the benefit of the whole community — in constructing and maintaining irrigation works, for example — and also engaged with ritual life within the doctrina, a participation that also demanded family and community expenditures.

Fig. 8.8 Sample page of the census conducted in 1653 by Juan de Escalante y Mendoza showing part of the headcount of reservados, adult men and women who because of their occupation, age or health were exempted from paying tribute (EAP333/1/3/11 image 106), Public Domain.

The presence of forasteros made figuring out the number of people required to form a doctrina problematic. The Canta headmen’s request was to make the number of taxpayers correspond with the number of heads of households, while the view of the church was to count the total number of doctrina inhabitants, independently of age, gender and fiscal status. This was a serious matter of contention because of the crucial issue placed at the core of the petition presented at the start: who was supposed to pay for the priest’s salary and what was its rightful source?

As we have seen, the priest’s salary was a portion of the taxes the repartimiento Indians paid to the encomendero and, once the encomienda ceased to exist, the payment was due to the corregidor. The indigenous headmen from Canta reasoned that if there were not enough taxpayers an additional doctrina was not justified. This view was not only based on the manifest decline in population, but also on the understanding that they had a right to be protected from abuse.48 From the viewpoint of the church, the decision to include every single inhabitant of the doctrina — whose souls had to be saved through the administration of the sacraments — was not arbitrary but legally supported by the decrees of the Council of Trent and the Lima church councils.49

A closely connected issue in the dispute was the source that provided the funds to pay for the priest’s salary. The petitioners challenged the archbishop’s decision to use the revenue from the community-owned farm now that the Pariamarca textile mill was closed, arguing that community assets were to be used only for the Indians’ own benefit.50 The fact that revenues from the obraje had been assigned to the doctrina at the time of its foundation was exceptional, they maintained. The status of Pariamarca, its inhabitants and resources is nevertheless left in the dark. For reasons that remain unexplained, Escalante carried out the headcount in the town of Canta and in the subsidiary settlement of Carcas, situated on the same river valley, but apparently he did not visit Pariamarca or the towns nearby (Figs. 8.9 and 8.10). This is intriguing, since Escalante’s knowledge of the doctrina was far from superficial: before his appointment as priest of the doctrina of Quivi, he had been parish priest at Pariamarca.51

Fig. 8.9 Cultivated fields in Pariamarca, August 2014. Photo by Évelyne Mesclier, CC BY.

The 1549 and 1553 inspections records of Canta, published by María Rostworowski, shed light on the special circumstances of Pariamarca. At that time, Pariamarca was not described as a village. The indigenous chiefs informed the inspectors in 1549 that it had no inhabitants and that under Inca rule weavers spent limited periods of time there producing cumbi, the finest textiles that only elite individuals were allowed to use.52 The inspectors arriving in 1553 in Pariamarca described it as a place where artisans belonging to the seven moieties of Canta assembled to weave cumbi. The inspectors found 29 well-built houses, and cultivated plots of land, but the people they interviewed informed them that there were no permanent residents and the houses they had seen were but temporary dwellings.53

The early sixteenth-century inspection records reveal that Pariamarca was a pre-Columbian centre of textile production. That the site did not have a permanent population was not exceptional, as a number of settlements across the Andes were used only temporarily.54 After the Spanish conquest, Pariamarca became an obraje and remained in indigenous hands. When the archbishop of Lima, Toribio Alfonso de Mogrovejo visited the diocese in 1598, Pariamarca was not yet a parish; it was listed in the records as a subsidiary village (pueblo) of the doctrina of Canta. It appears that because of the obraje, Pariamarca’s status was exceptional. The headcount carried out during Mogrovejo’s inspection yielded a total of 335 people in Pariamarca, but not all of them were included in the total population count of the doctrina. The textile mill was mentioned as a place in addition to the subsidiary towns of Canta.55

Who exactly were the labourers at the obraje is unclear. According to the headmen of Canta that requested the closing down of the doctrina in 1653, production at the obraje relied on draft labour (mitayos);56 this explains why, once the textile mill was destroyed, the labourers disbanded. The inspections of 1549 and 1553 present a different view, as they suggest that all the Canta parcialidades, ayllus and settlements periodically sent labourers to Pariamarca to weave cloth. Cloth and clothing were also produced domestically, and the products were taken to Lima and sold to get the cash necessary to pay the head tax.57

Finding out the names and number of the obraje labourers, as well as where they resided was crucial to determine the boundaries of the parish. If the labourers were from the doctrina, then Pariamarca had to continue to exist, as the archbishopric’s representative maintained. If they were coming from elsewhere, as the Canta headmen argued, the labourers had already left, their pastoral care was under other parish jurisdictions, and there was little justification for keeping the doctrina in Pariamarca.

These issues were difficult to elucidate because, in order to pursue their productive activities and to respond to the demands of the colonial state, the local population was and needed to be very mobile. In fact, many adult men and a smaller number of women moved out from their doctrinas never to return, as the case of the forasteros living in Canta demonstrates. When Escalante conducted the headcount in 1653, several adult men, a few boys and a couple of women were registered as missing (ausentes). Indigenous officers were constantly accused of hiding their subjects to evade tribute payments and, as the case of the non-inhabited, although non-abandoned, villages demonstrates, in the Andes people often made use of their space differently from the way certain Spanish authorities were prepared to understand.

There was more to this case. Having learned about the petition to close down the doctrina of Pariamarca, don Francisco Pizarro Caruavilca, the cacique of the village of Lachaqui (subsidiary of Pariamarca) requested the archbishopric that, if the Canta headmen were successful, his town of Lachaqui and all others under his authority should not become subsidiary to Canta. Don Francisco adduced that the long distances in between villages, the rough terrain, and the difficulties involved in travelling up the valley, especially during the rainy season, made Lachaqui’s attachment to the doctrina of Canta inconvenient. He explained that his people spent most part of the year not in Lachaqui, but working in their farms in the low-altitude, warmer sections of the valley, in a location called Mallo. The people of Lachaqui, argued don Francisco, regularly attended mass at Mallo and, when necessary, at Quivi, where they also went regularly to comply with the mita or draft labour.58

Fig. 8.10 A street in Pariamarca, August 2014. Photo by Évelyne Mesclier, CC BY.

If Pariamarca ceased to exist as a doctrina, don Francisco and his people would be compelled to travel to Canta to attend a series of unavoidable religious functions, from regular mass and confession to Holy Week and Corpus Christi, not to speak of the contributions in money and labour the curate at Canta was likely to demand from them. This situation would threaten their welfare, for the long and dangerous journeys to Canta would not allow them to look after their farms. The archbishopric requested don Diego de Vergara, a canon in the Lima cathedral chapter and a former parish priest at Quivi, to offer his opinion on the petition. One by one, displaying knowledge about the conditions of the terrain, about the weather, about the villages in the region and the distances between them, Vergara dismissed don Francisco’s points. Don Alonso Osorio, also a canon and former parish priest, presented a brief statement sharing Vergara’s views. But these interventions from the high clergy did not dismiss the cacique’s petition, for both Vergara and Osorio also advised against the closing down of the doctrina of Pariamarca.

The canons’ involvement in the proceedings had the effect of disempowering the cacique by accusing him of misrepresenting the situation, but in an oblique manner, their statements were also a boost for don Francisco, who must have been relieved at the prospect that his people would not fall under the dominance of the curate of Canta and possibly, that of its indigenous headmen.

Conclusion

Fig. 8.11 A view of the town and valley of Canta, August 2014.

Photo by Évelyne Mesclier, CC BY.

The file ends rather abruptly, leaving us wondering about the outcome of the proceedings. Once Escalante finished the headcount in Canta, we find don Francisco’s petition, followed by Vergara’s and Osorio’s depositions. The final pages, written three years later in 1656, contain two petitions addressed to the viceregal justice. The first, by the Protector general de los indios, or Indians’ attorney, and the second by don Phelipe Quispi Guaman Yauri, governor of the Canta repartimiento. Both petitions reiterate the request to close down the doctrina of Pariamarca and warn about the political costs of keeping a parish that so obviously represented a burden on a population whose numbers continued to decline. We get the impression that the case would hover indefinitely.

The lack of a conclusion to the proceedings is frustrating, although unsurprising. In colonial Spanish America — and Peru was no exception — legal disputes could take years, even decades, without ever reaching a resolution. Historians investigating the social significance of law under Spanish colonial rule maintain that its power resided in the proceedings rather than in the results.59

Parish boundaries in colonial Peru represent a complex set of issues. For the church and the Spanish crown, dividing the territory to carry out the evangelising endeavour seemed both appropriate and necessary. Contemporary ideas about Christian duty were combined with the crown’s imperative to compensate a number of soldiers, clergymen, entrepreneurs, and bureaucrats for their services to the king. This was no easy amalgam. The Catholic church, at the global and local level, provided the principles guiding the procedure.60 Implementing these norms involved dealing with the local populations, which held their own religious views and kept their own sacred places, had their own political institutions and systems of authority, in addition to their own ways of controlling and using vital resources such as land and water. In the Peruvian Andes, parish boundaries were linked to aspects such as dwindling population numbers, as well as kinship ties and political alliances that had been severely affected by the Spanish conquest and continued to evolve. As all other parts of the colonial edifice, parishes rested upon indigenous labour. The case studied here exemplifies the extent to which the very existence of the parish, its functioning and reach, concerned perhaps more than any other colonial institution, the lives and livelihood of the people.

References

Acosta, José de, “Historia natural y moral de las Indias”, in Obras del P. José de Acosta, ed. by S. J. Francisco Mateos (Madrid: Atlas, 1954 [1590]), pp. 1-247.

Bauer, Brian, The Sacred Landscape of the Inca: The Cusco Ceque System (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1998).

Benito, José Antonio, ed., Libro de visitas de santo Toribio de Mogrovejo (1593-1605) (Lima: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, 2006).

Burns, Kathryn, “Unfixing Race”, in Histories of Race and Racism: The Andes and Mesoamerica from Colonial Times to the Present, ed. by Laura Gotkowitz (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), pp. 57-71.

Cañeque, Alejandro, The King’s Living Image: The Culture and Politics of Viceregal Power in Colonial Mexico (London: Routledge, 2004).

Cieza de León, Pedro de, Crónica del Perú. Primera parte. 2nd edn. (Lima: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, 1984 [1553]).

Clayton, Lawrence, Bartolomé de Las Casas and the Conquest of the Americas (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011).

Cook, David N., ed., Demographic Collapse: Indian Peru, 1520-1620 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981).

—, Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492-1650 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Council of Trent, “The Canons and Decrees of the Sacred and Oecumenical Council of Trent”, ed. by J. Waterworth (London: Dolman, 1848).

Covarrubias, Sebastián de, Tesoro de la lengua castellana o española (Barcelona: Alta Fulla, 2003 [1611]).

Diez Hurtado, Alejandro, Comunes y haciendas: Procesos de comunalización en la sierra de Piura, siglos XVIII al XX (Cuzco/Piura: CIPCA/Centro Bartolomé de las Casas, 1998).

Elliott, John H., “The Spanish Conquest and Settlement of America”, in The Cambridge History of Latin America, ed. by Leslie Bethell (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), pp. 147-206.

—, “Spain and America in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries”, in The Cambridge History of Latin America, ed. by Leslie Bethell (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), pp. 287-340.

Escandell Tur, Neus, Producción y comercio de tejidos coloniales: los obrajes y chorrillos del Cusco, 1570-1820 (Cuzco: Centro de Estudios Regionales Andinos Bartolomé de las Casas, 1997).

Espinoza Soriano, Waldemar, “Migraciones internas en el reino colla: tejedores, plumereros y alfareros del Estado imperial inca”, Chungará, 19 (1987), 243-89.

Gade, Daniel W., and Mario Escobar, “Village Settlements and the Colonial Legacy in Southern Peru”, Geographical Review, 72 (1982), 430-49.

Garrett, David, Shadows of Empire: The Indian Nobility of Cusco, 1750-1825 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Harris Isbell, William, Mummies and Mortuary Monuments: A Postprocessual History of Central Andean Social Organization (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1997).

Instituto Geográfico Nacional del Perú, Canta, Perú. Edition 1-IGN, Series J631, Sheet 1548 (23-J) (Lima: Instituto Geográfico Nacional, 1967).

Instituto Geográfico Nacional del Perú, Chosica, Perú. Edition 2-IGN, Series J631, Sheet 1547 (24-J) (Lima: Instituto Geográfico Nacional del Perú, 1971).

Kagan, Richard, and Fernando Marías, Urban Images of the Hispanic World, 1493-1793 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000).

Keith, Robert, Conquest and Agrarian Change: The Emergence of the Hacienda System on the Peruvian Coast (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976).

Makowski, Krzysztof, “Andean Urbanism”, in Handbook of South American Archaeology, ed. by Helaine Silverman and William Isbell (New York: Springer, 2008), pp. 633-57.

Málaga Medina, Alejandro, “Las reducciones en el virreinato del Perú (1532-1580)”, Revista de Historia de América, 80 (1975), 8-42.

Molina, Cristóbal de, Fábulas y mitos de los Incas, ed. by Henrique Urbano and Pierre Duviols, Crónicas de América (Madrid: Historia 16, 1988).

Muldoon, James, The Americas in the Spanish World Order: The Justification for Conquest in the Seventeenth Century (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1994).

Mumford, Jeremy Ravi, Vertical Empire: The General Resettlement of Indians in the Colonial Andes (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012).

Murra, John, The Economic Organization of the Inka State (Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 1980).

—, “Andean Societies before 1532”, in The Cambridge History of Latin America, ed. by Leslie Bethell (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), pp. 59-90.

O’Malley, John, Trent: What Happened in the Council (Cambridge, MA: Belknap, 2013).

Ortiz de la Tabla Ducasse, Javier, “Obrajes y obrajeros del Quito colonial”, Anuario de Estudios Americanos, 39 (1982), 341-65.

Owensby, Brian P., Empire of Law and Indian Justice in Colonial Mexico (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008).

Peñaherrera del Águila, Carlos, ed., Atlas del Perú (Lima: Instituto Geográfico Nacional, 1989).

Rackham, Oliver, “Review of ‘Discovering Parish Boundaries’”, Journal of Ecclesiastical History, 43 (1992), 504.

Ramos, Gabriela, Death and Conversion in the Andes: Lima and Cuzco, 1532-1670 (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2010).

—, “Los tejidos y la sociedad colonial andina”, Colonial Latin American Review, 19 (2010), 115-49.

—, “Pastoral Visitations as Spaces of Negotiation in Andean Parishes”, The Americas (forthcoming).

Rostworowski de Diez Canseco, María, Estructuras Andinas del poder: ideología religiosa y política (Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1983).

Rostworowski, María, Señoríos indígenas de Lima y Canta (Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1978).

—, “Las visitas a Canta de 1549 y de 1553”, in Obras Completas (Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 2002), pp. 289-373.

Salas de Coloma, Miriam, De los obrajes de Canaria y Chincheros a las comunidades indígenas de Vilcashuamán: siglo XVI (Lima: Sesator, 1979).

Salomon, Frank, and George Urioste, eds., The Huarochirí Manuscript: A Testament of Andean and Colonial Andean Religion (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1991).

Salvucci, Richard, Textiles and Capitalism in Mexico: An Economic History of the Obrajes, 1539-1840 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1987).

Sánchez Albornoz, Nicolás, Indios y tributos en el Alto Perú (Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1978).

Spalding, Karen, “The Crises and Transformations of Invaded Societies: The Andean Area”, in The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas, ed. by Frank Salomon and Stuart B. Schwartz, 3 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), pp. 904-72.

Tineo, Melecio, Vida eclesiástica, Perú colonial y republicano. Catálogos de documentación sobre parroquias y doctrinas de indios. arzobispado de Lima, siglos XVI-XX (Cuzco: Centro Bartolomé de las Casas, 1997).

Tineo, Primitivo, “La recepción de Trento en España (1565): disposiciones sobre la actividad episcopal”, Anuario de Historia de la Iglesia, 5 (1996), 241-96.

Trujillo Mena, Valentín, La legislación eclesiástica en el virreynato del Perú durante el siglo XVI (Lima: Imprenta Editorial Lumen, 1981).

Vargas Ugarte, Rubén, ed., Concilios Limenses (1551-1772), 3 vols (Lima: [n. pub.], 1951).

Wernke, Steven, “Negotiating Community and Landscape in the Andes: A Transconquest View”, American Anthropologist, 109 (2007), 130-52.

Wightman, Ann, Indigenous Migration and Social Change: The Forasteros of Cuzco, 1570-1720 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1990).

Archival resource

Autos de la supresión de la doctrina de Pariamarca en el corregimiento de Canta que se pretende por los indios de dicha doctrina, in Archives of the Diocese of Huacho (ADH), Curatos, Leg. 2, Exp. 1, 1653.

1 EAP333: Collecting and preserving parish archives in an Andean diocese, http://eap.bl.uk/database/overview_project.a4d?projID=EAP333

2 The Council of Trent, one of the most important events in the history of the Catholic church, was held in the city of Trent in the sixteenth century (1545-47, 1551-52, 1562-63). The Council assembled western European prelates and theologians in response to the challenges posed by the Reformation. The Council of Trent produced canons and decrees clarifying Catholic doctrine and practice, and aimed to reform the life of the clergy. The literature on the subject is vast. An accessible book on Trent is John O’Malley, Trent: What Happened at the Council (Cambridge, MA: Belknap, 2013).

3 Krzysztof Makowski, “Andean Urbanism”, in Handbook of South American Archaeology, ed. by Helaine Silverman and William Isbell (New York: Springer, 2008), pp. 633-57.

4 John V. Murra, The Economic Organisation of the Inka State (Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 1980).

5 Terence D’Altroy, The Incas (Oxford: Blackwell, 2002).

6 Gabriela Ramos, Death and Conversion in the Andes: Lima and Cuzco, 1532-1670 (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2010).

7 Jeremy Ravi Mumford, Vertical Empire: The General Resettlement of Indians in the Colonial Andes (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012).

8 Richard Kagan, and Fernando Marías, Urban Images of the Hispanic World, 1493-1793 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000).

9 The name doctrinas was given to parishes entirely populated by Indians, thus dedicated exclusively to their religious indoctrination. Valentín Trujillo Mena, La legislación eclesiástica en el virreynato del Perú durante el siglo XVI con especial aplicación a la Jerarquía y a la Organización Diocesana (Lima: Editorial Lumen, 1981).

10 John H. Elliott, “The Spanish Conquest and Settlement of America”, in The Cambridge History of Latin America, 1st edn., ed. by Leslie Bethell, 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), pp. 147-206, http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521232234.008. For a contemporary description of the Potosí mines in the sixteenth century, see Joseph de Acosta, “Historia natural y moral de las Indias”, in Obras del P. José de Acosta, ed. by S. J. Francisco Mateos (Madrid: Atlas, 1954 [1590]), pp. 1-24, http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra-visor/historia-natural-y-moral-de-las-indias--0/html/fee5c626-82b1-11df-acc7-002185ce6064_8.html#I_78_, book 4, ch. 6

11 John V. Murra, “Andean Societies Before 1532”, in The Cambridge History of Latin America, 1st edn., ed. by Leslie Bethell, 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), pp. 59-90, http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521232234.004

12 An encomendero was the grantee of an encomienda.

13 The encomienda had its precedent in the repartimientos granted during the Reconquista, a crucial historical period in the Iberian peninsula by which Christian kings and lords fought intermittently throughout seven centuries to recapture territory from Muslim domination. Whilst in Iberia, the granting of repartimientos involved land, but this was not the case in the New World. This of course did not prevent encomenderos from appropriating land belonging to indigenous people. Scholars have suggested that the large landed property, known as hacienda, had its origins in the encomienda. For a classic example of this view, see Robert Keith, Conquest and Agrarian Change: The Emergence of the Hacienda System on the Peruvian Coast (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976). For a brief, yet clear explanation of the encomienda in Iberian history and in the early history of Spanish conquest and colonisation of the New World, see John H. Elliott, “Spain and America in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries”, in The Cambridge History of Latin America, 1st edn., ed. by Leslie Bethell, 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), pp. 147-206, http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521232234.008

14 On the population crisis at the time of contact, see, for example, Noble David Cook, Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492-1650 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998); and idem, Demographic Collapse: Indian Peru, 1520-1620 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981).

15 Lawrence A. Clayton, Bartolomé de las Casas and the Conquest of the Americas (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011).

16 For an excellent discussion of the king’s support of the Catholic church, see James Muldoon The Americas in the Spanish World Order: The Justification for Conquest in the Seventeenth Century (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1994).

17 The term cacique, a word that the Spanish had learned in the Caribbean, was widely used across the Americas to refer to indigenous chiefs.

18 The resettlement of the indigenous population was carried out with mixed results all over Spanish America. In the Andes these settlements were known as reducciones and in Mexico they were called congregaciones.

19 Alejandro Málaga Medina gives a long-term overview of reducciones from the time of the conquest up to a few years after their implementation by viceroy Toledo. His research is based mostly on legislation and official documentation related to reducciones. See Alejandro Málaga Medina, “Las reducciones en el virreinato del Perú (1532-1580)”, Revista de Historia de América, 80 (1975), 8-42. Daniel W. Gade and Mario Escobar offer a long-term perspective of settlements situated in a highland province of Cuzco. The authors are geographers, and the discussion presented is guided almost in its entirety by fieldwork, and by inferences transposed from the present to the past. See Daniel W. Gade and Mario Escobar, “Village Settlements and the Colonial Legacy in Southern Peru”, Geographical Review, 72 (1982), 430-49. From the field of archaeology, Steven Wernke has published several works about reducción formation, focusing on the Colca valley in southern Peru. See, for example, Steven Wernke, “Negotiating Community and Landscape in the Andes: A Transconquest View”, American Anthropologist, 109 (2007), 130-52. The most ambitious study to date on the subject is Mumford, who also offers an overview of reducción as a critical component of the colonial project; the strength of his book is the refreshing discussion of the legal and political debates surrounding reducciones. Mumford maintains that the documentary evidence for the founding and early history of reducciones is insufficient. For a discussion of these issues although for a later period in northern Peru, see Alejandro Diez, Comunes y haciendas: procesos de comunalización en la sierra de Piura, siglos XVIII al XX (Cuzco: CIPCA and Centro Bartolomé de las Casas, 1998).

20 “As regards those churches, to which, on account of the distance, or the difficulties of the locality, the parishioners cannot, without great inconvenience, repair to receive the sacraments, and to hear the divine offices; the bishops may, even against the will of the rectors, establish new parishes, pursuant to the form of the constitution of Alexander III, which begins, Ad audientiam…”. The Canons and Decrees of the Sacred and Oecumenical Council of Trent, ed. and trans. by J. Waterworth (London: Dolman, 1848), Twenty-First Session, Decree on Reformation, ch. 4, p. 147, http://history.hanover.edu/texts/trent/ct21.html

21 Repartimientos were the grants of people given to encomenderos as compensation for their participation in the conquest (see above, note 13). A seventeenth-century Spanish dictionary defines repartimiento as the effect of dividing something into parts. Sebastián de Covarrubias, Tesoro de la lengua castellana o española (Barcelona: Alta Fulla, 2003 [Madrid: Luis Sánchez, 1611]), p. 905. What early Spanish chroniclers and travellers described as provincias (provinces) were later divided between religious orders and encomenderos. Repartimientos stemmed from these initial divisions. It is apparent that the term repartimiento had a shifting meaning throughout the colonial period.

22 “Primer Concilio Provincial Limense, Constituciones de los Naturales”, in Concilios Limenses, ed. by Rubén Vargas Ugarte, 3 vols (Lima: [n. pub.], 1951), 1, Constitución 29, p. 24. See also Mumford, p. 120.

23 Vargas Ugarte, 1, Constitución 2, pp. 8-9; idem, Constitución 40, p. 33. A similar directive is found in the decrees of the Second Lima Council (1567) in idem, 1, p. 251. In this text, the bishops advised that encomenderos and curacas should also be consulted about the most adequate place to build a church.

24 Mumford, pp. 28-29. Mumford presents an interesting discussion on the subject of repartimientos. On Andean political organisation, see also María Rostworowski, Estructuras andinas del poder: ideología religiosa y política (Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1983).

25 See, for instance, Pedro Cieza de León, Crónica del Perú, Primera parte (Lima: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, 1984). The link between parish and territory is best represented in the legislation concerning pastoral visitations. Both the Council of Trent and the local church councils ruled that bishops should periodically visit the towns within their dioceses to inspect the functioning of their parishes, to assess priest behaviour and competence, and to certify the correct indoctrination of their parishioners. Council of Trent rulings on visitations are found in Session 24, Reformation decrees, ch. 3, http://history.hanover.edu/texts/trent/ct24.html. Constitution 44 of the Lima First Council ruled that bishops should inspect the towns within their dioceses every two years (Vargas Ugarte, 1, p. 62). On inspection visits in the Lima diocese, see Gabriela Ramos, “Pastoral Visitations as Spaces of Negotiation in Andean Parishes,” in The Americas (forthcoming).

26 As attested by The Huarochirí Manuscript, ed. by Frank Salomon (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1991); and Cristóbal de Molina’s Fábulas y Mitos de los Incas, ed. by Henrique Urbano and Pierre Duviols (Madrid: Historia 16, 1988). For archaeological studies supporting this view, see William Harris Isbell, Mummies and Mortuary Monuments: A Postprocessual History of Central Andean Social Organization (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1997); and Brian Bauer, The Sacred Landscape of the Inca: The Cusco Ceque System (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1998). A historical interpretation of this extended practice can be found in Ramos, Death and Conversion, pp. 9-33.

27 “Sumario del concilio provincial que se celebró en la ciudad de Los Reyes el año de mil y 567”. Vargas Ugarte, 3, p. 249. Based on a study of the laws produced by the church in the sixteenth century, Trujillo Mena assures that territory was a constitutive part of the doctrina (p. 242).

28 Oliver Rackham described parish boundaries in England as “a rebuke to administrative tidiness”. Oliver Rackham, “Review of ‘Discovering Parish Boundaries’”, Journal of Ecclesiastical History, 43 (1992), 504.

29 I use the word “headmen” here and throughout because — for reasons that would be worth investigating, although not at this time — the documents describe most indigenous authorities as governors and principals, but — with one exception — not as caciques or curacas as it was customary in other areas of the Andes.

30 “Autos de la supresión de la doctrina de Pariamarca en el corregimiento de Canta que se pretende por los indios de dicha doctrina”, in Archives of the Diocese of Huacho (ADH), Curatos, Leg. 2, Exp. 1, 1653. For a good overview — although focused on Cuzco and Peru’s southeast — of how Andean settlements were organised and the participation indigenous people had in their government, see David Garrett, Shadows of Empire: The Indian Nobility of Cusco, 1750-1825 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), pp. 15-44.

31 On textile mills (obrajes) in the Andes and other regions of Spanish America, see Miriam Salas de Coloma, De los obrajes de Canaria y Chincheros a las comunidades indígenas de Vilcashuamán, siglo XVI (Lima: Sesator, 1979); Neus Escandell, Producción y comercio de tejidos coloniales: Los obrajes y chorrillos del Cusco 1570-1820 (Cusco: Centro Bartolomé de las Casas, 1997); Javier Ortiz de la Tabla Ducasse, “Obrajes y obrajeros del Quito colonial”, Anuario de Estudios Americanos, 39 (1982), 341-65, and Richard Salvucci, Textiles and Capitalism in Mexico: An Economic History of the Obrajes, 1539-1840 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1987).

32 See note 21.

33 Males from eighteen to fifty years of age were subject to paying head tax.

34 The decree in Spanish uses the word “reducido”, which I interpret here as established in a town or reducción and therefore under the government’s control.

35 “Los decretos del santo concilio provincial celebrado en la ciudad de Los Reyes del Perú en el año de 1583”, in Vargas Ugarte, 2, ch. 11, p. 348.

36 Exempted from tax were “reservados”. These included men older than fifty years old; also, the ill or injured and unable to work, and those holding a position in the church, such as choristers and sacristans.

37 The order was issued on 7 October 1653, “Autos de la supresión…”, ADH, Curatos, Leg. 1, Exp. 2, f. 88.

38 These parish officers were known as fiscales and alguaciles. Their duties could be described as those of a church police. Both fiscales and alguaciles had to make sure that everyone in town attended mass and cathechism instruction and observed correct behaviour.

39 “Autos de la supresión…”, ADH, Curatos, Leg. 1, Exp. 2, f. 97.

40 These parcialidades, in which repartimientos were divided, were not necessarily exact halves, as the case of Canta. Each moiety was subdivided in kin groups or ayllus. The number of ayllus in each moiety could vary. For a view on how repartimientos were organised, see Mumford, pp. 28-29.

41 These parcialidades are mentioned in the records of an inspection carried out in 1553. María Rostworowski, “Las visitas de Canta de 1549 y 1553”, in Obras Completas, 2 (Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 2002), pp. 289-314.

42 Such as Carhua, Visca and Lachaqui. See map in Rostworowski, “Las visitas”, p. 294.

43 Waldemar Espinoza Soriano, “Migraciones internas en el reino Colla: Tejedores, plumereros y alfareros del estado imperial Inca”, Chungará, 19 (1987), 243-89.

44 From very early in the colonial period, Spanish colonial officers aimed to keep the indigenous population separated from Spaniards, mixed-race and Africans, arguing that Indians were thus protected from abuse and bad example. Although this goal proved unattainable in the large urban centres, it is often assumed that such was not the case in small provincial settlements. On Spanish colonial policies about race and racial mixing, see Kathryn Burns, “Unfixing Race”, in Histories of Race and Racism: The Andes and Mesoamerica from Colonial Times to the Present, ed. by Laura Gotkowitz (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), pp. 57-71. On the significance of forasteros in Andean colonial society, see Nicolás Sánchez Albornoz, Indios y tributos en el Alto Perú (Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1978); and Ann Wightman, Indigenous Migration and Social Change: The Forasteros of Cuzco, 1570-1720 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1990).

45 Including the 75 people of all ages found in the inspection of the town of Carcas, subsidiary or annex of the doctrina of Canta, a settlement situated further up the valley. The headcount does not provide total numbers, but only for the first ayllu of the first moiety registered. According to this view, the number of taxpayers would have been higher, since Escalante incorporated to the headcount those who were absent.

46 Rostworowski, “Las visitas”, p. 347. The population losses are appalling. The friars carrying out the inspection in 1549 also noted a number of abandoned houses. Ibid., p. 295.

47 The incorporation of forasteros into the registers of taxpayers was not uniform throughout the Andes. It is not apparent from the documents herein studied that forasteros were also taxpayers.

48 On the political principles that guided the link between the Spanish king and the indigenous vassals, see Alejandro Cañeque, The King’s Living Image: The Culture and Politics of Viceregal Power in Colonial Mexico (London: Routledge, 2004). An excellent discussion about how indigenous people understood and made use of the law under Spanish colonial rule can be found in Brian P. Owensby, Empire of Law and Indian Justice in Colonial Mexico (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008).

49 See note 15, and “Autos de la supresión…” f. 44v, where the archbishop’s representative argues that even if the population is smaller than the required number of parishioners established by law, ultimately the decision to create or maintain a parish belonged to the bishop.

50 Community assets were meant to provide extra income when resources were insufficient for the maintenance of community members or to acquire the necessary means to pay for the head tax.

51 The historical archives of the archdiocese of Lima (AAL) hold the file of a petition Escalante presented in 1640, wherein he describes himself as “el bachiller don Juan de Escalante y Mendoza, presbítero, cura y vicario del pueblo de Pariamarca y sus anexos…”. AAL, Curatos Diversos, 1622-1899, exp. 42v. The reference is found in Melecio Tineo, Vida eclesiástica, Perú colonial y republicano: Catálogos de documentación sobre parroquias y doctrinas de indios. Arzobispado de Lima, siglos XVI-XX, 1 (Cuzco: Centro Bartolomé de las Casas, 1997), p. 403.

52 In the course of the visitation, the inspectors noted sixteen abandoned villages and were informed that artisans lived in them only temporarily. Pariamarca is mentioned in the records as Paron Marca Cambis. Rostworowski, “Las visitas”, p. 345. On the role of textiles and especially of cumbi in Andean society, see Gabriela Ramos, “Los tejidos y la sociedad colonial andina”, Colonial Latin American Review, 19 (2010), 115-49.

53 Rostworowski, “Las visitas”, pp. 370-71.

54 Mumford, p. 25.

55 José Antonio Benito, Libro de visitas de santo Toribio de Mogrovejo (1593-1605) (Lima: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, 2006), p. 172. Unfortunately, the inspection records do not provide an explanation for how the headcount was conducted. It is unclear why the obraje was noted apart. The omission is probably not entirely Mogrovejo’s secretary’s fault: the transcription of the pastoral visitations is poorly edited and the errors are so many that scholars must use it with much caution.

56 The Inca used draft labour, regularly levied for several purposes, from agriculture to public works. Spanish colonial officers adapted this system for the benefit of miners, encomenderos, farmers, obrajes, various entrepreneurs, and urban centres. The system was called mita and the labourers were known as mitayos. See Mumford, pp. 95-96; and Karen Spalding, “The Crises and Transformations of Invaded Societies: The Andean Area”, in The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas, ed. by Frank Salomon and Stuart B. Schwartz, 3 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), pp. 904-72.

57 Rostworowski, “Las visitas”, p. 372.

58 Among a number of duties, Indians complying with the mita had to provide services at inns (tambos) located in key points on Andean roads. One of these inns was situated in the town of Quivi.

59 See Owensby. On late August 2014, I visited the town of Pariamarca along with friends and colleagues, whose company and support I would like to acknowledge: Évelyne Mesclier, Ana María Hurtado and César Iglesias. From our conversations with the locals, we learned that no one knows today that in Pariamarca there was ever a textile mill. Pariamarca has a church, but does not have parish status. For government administration purposes, Pariamarca is today subordinated to Canta.

60 In 1564 the Spanish crown incorporated the decrees of the Council of Trent as law of the state. On this subject, see Primitivo Tineo, “La recepción de Trento en España (1565): disposiciones sobre la actividad episcopal”, Anuario de Historia de la Iglesia, 5 (1996), 241-96.