9. Researching the history of slavery in Colombia and Brazil through

ecclesiastical and notarial archives

© J. Landers, P. Gómez, J. Polo Acuña and C.J. Campbell, CC BY http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0052.09

This chapter addresses the history of slavery and development in two of the most African locales in colonial South America: the Pacific and Caribbean coasts of modern Colombia and northeastern Brazil. Both modern nations have recognised the historical and civic neglect of the “black communities” within their borders and now offer them legal and cultural recognition, as well as, at least theoretical, recognition of ancestral communal land ownership.1 The endangered archives digitised under the auspices of the British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme enable researchers, as well as these neglected populations, to know more about their often hard to discover past.2

Colombia’s rich colonial history began in the early sixteenth century when war-hardened adventurers like Alonso de Ojeda, already experienced in the conquest and colonisation of Española (modern Dominican Republic and Haiti) first explored its Caribbean coast in search of gold, Indian slaves, and potential profits.3 In 1525, after decades of brutal coastal raids, another veteran of Española, Rodrigo de Bastidas, founded Santa Marta using slave labour. However, some of the slaves soon rebelled and burned the fledgling town before running to the rugged interior hinterlands where they formed runaway, or maroon, communities known as palenques. Some of these maroon settlements survived for centuries, resisting the Spanish military expeditions that attempted to eradicate them.4

Undaunted, in 1533, another émigré from Española, Pedro de Heredia, founded Cartagena de Indias, also on the Caribbean coast of New Granada.5 Treasure hunters from Cartagena initially employed African slaves to extract gold from looted tombs of the Sinú Indians.6 As those treasures were depleted, Spanish settlers established plantations, ranches and gold mines in the central valley of Colombia, all of which required large numbers of enslaved African labourers.

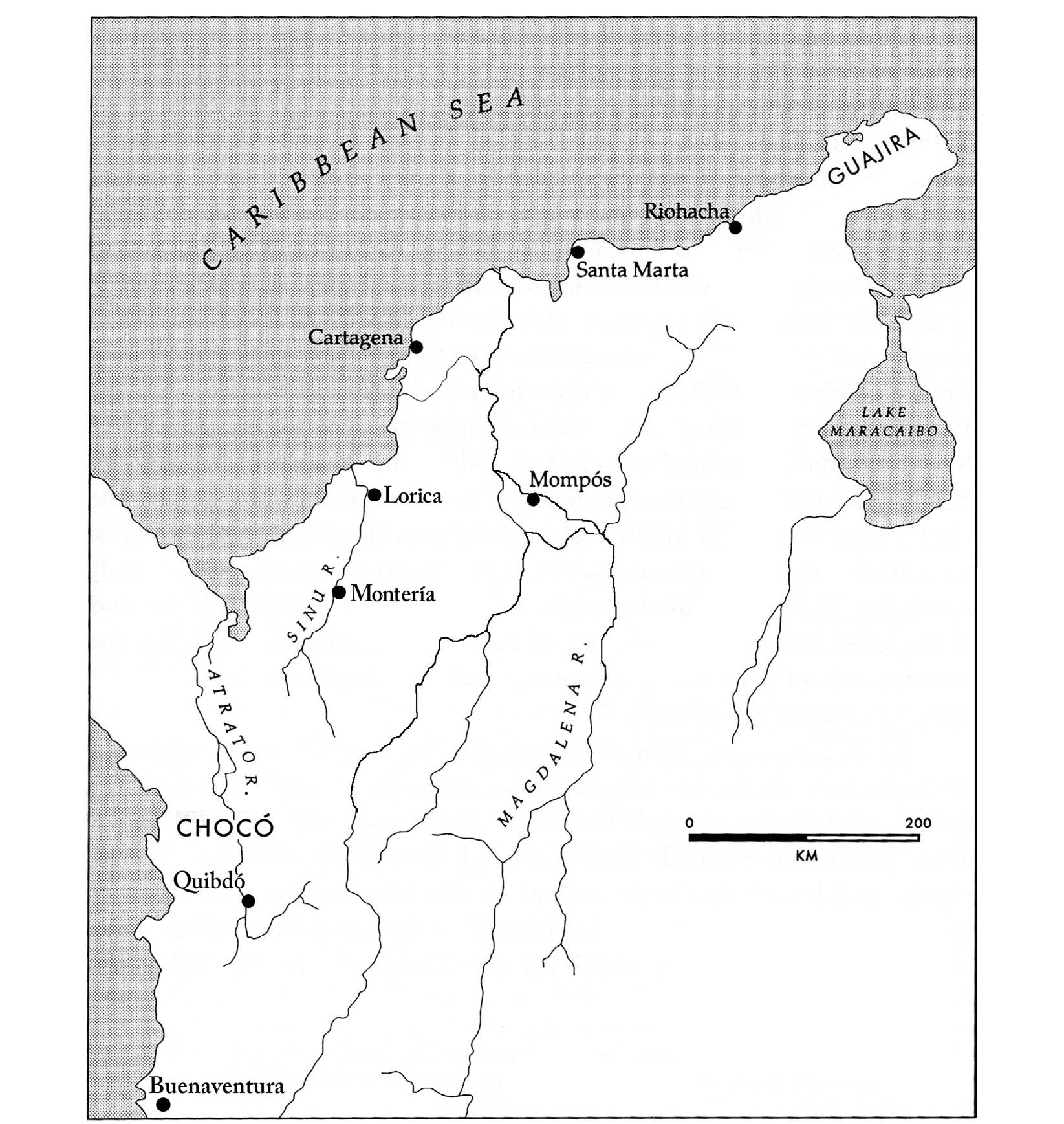

The Magdalena River, which runs through the central valley, became Colombia’s main artery to the interior and it, too, became a largely African region (Fig. 9.1). Soon enslaved Africans replaced Indian rowers on the boats transporting goods to and from Cartagena and Mompox, which was essentially an inland Caribbean port. Enslaved Africans also built the vast complex of fortifications and public works that protected Cartagena, while potentially more fortunate slaves served as domestics in the private homes and the many convents of the city.7

Cartagena was designated as an official port of the Spanish fleet system as early as 1537, and became “by far the largest single port of [slave] debarkation in the Spanish Americas”.8 Most of the early slave shipments into Cartagena originated from Upper Guinea (the Rivers of Guinea) and Cabo Verde. Later shipments through São Tomé brought slaves from Lower Guinea and Angola.9 David Wheat has used previously unknown port entry records to document 463 slave ships arriving in Cartagena between 1573 and 1640 that disgorged more than 73,000 enslaved Africans who were recorded by port officials.10 How many more were smuggled into Cartagena cannot be known, but these numbers clearly show that the city and its hinterlands, where even fewer whites resided, quickly took on the aspect of an African landscape. When the slave ships came into port, agents from as far away as Lima descended upon Cartagena to conduct purchases, and a number of the newly arrived slaves were subsequently transported to Portobello (modern Panama) or to the mines of Potosí in modern Bolivia.11 Many also escaped to form a network of palenques encircling Cartagena.12

Fig. 9.1 Map of Pacific and Caribbean Colombia,

by James R. Landers, CC BY-NC-ND.

Spanish efforts to control Colombia’s western Pacific coast were simultaneous to those made on the Caribbean coast, and followed a similar trajectory. Gold-seeking raiders killed hundreds of natives, burned native villages, attempted to establish fortified settlements, and were repeatedly driven away. From the Isthmus of Panama, the Spaniards moved eastward into the Darién and then eventually pushed farther south into the rugged Chocó, Colombia’s northwestern region of dense jungles noted for its hot and humid climate and extreme rainfalls. Hostile native groups with deadly poison-tipped arrows also prevented Spaniards from settling in the area in the early years of exploration.13 One unhappy Spaniard called the Chocó “an abyss and horror of mountains, rivers, and marshes”.14 Although for many years, Spaniards considered the Chocó a useless and unhealthy frontier, discoveries of gold, silver, and later platinum, attracted miners to the region, and they brought large numbers of enslaved Africans to extract the precious metals.15 As in other contact zones, smallpox and later epidemics of measles combined with unaccustomed labour led to a dramatic decline among the native populations of the Chocó, and more African labourers were brought in to replace them in the mines and agricultural production. The newly imported African bozales arriving in Quibdó and Buenaventura in the eighteenth century lived in small villages or rancherias located in the tropical rainforest while working on alluvial mining centers.16 Independent free prospectors called mazamorreros were also drawn to work in the Chocó.17 The region, therefore, acquired a distinct culture that blended indigenous, African and European peoples and traditions, although people of African descent predominated by the eighteenth century.18

In 1654, Spaniards established San Francisco de Quibdó along the Atrato River that leads to the Caribbean and the small village served as the first regional capital of the Chocó (Fig. 9.1). Quibdó remained relatively isolated, however, because in 1698, in a vain attempt to curtail contraband trade, officials of the Royal Audiencia of Santa Fe de Bogotá banned commerce on the river. The village of Nóvita, on the San Juan River in the southern Chocó, therefore, became the first important mining center in the region, as well as the Chocó’s new regional capital. Although Indian attacks led Spaniards to abandon Nóvita several times, the area’s gold deposits always lured them back to re-build it. In 1784, Bourbon reformers re-opened the Atrato River to legal maritime trade, and Quibdó finally gained importance as a commercial center. In the nineteenth century, it again became the regional capital.19 The abolition of slavery in 1851 disrupted labour supplies for the gold mines of Nóvita causing it to decline in economic importance, but Quibdó’s commerce was relatively unaffected.20 Many of the formerly enslaved in Quibdó had already purchased their freedom with gold mined on days off or stolen from their owners, and by the eighteenth century the Chocó was home to a large free population of African descent.21

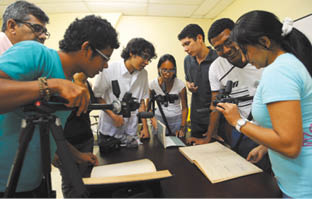

Still considered an inhospitable locale for its distinctive climate, the Chocó is today also notorious for the activities of leftist and paramilitary groups and drug trafficking organisations including the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC), which has been waging war against the Colombian state for more than five decades. An estimated 20,000 Chocoanos, most of African descent, have been displaced by the violence.22 While creating misery for the local inhabitants of the Chocó, this military conflict has also exacerbated the threat to local history and the remaining archives in the region. Supported by the project EAP255, Pablo Gómez trained students from the Universidad Tecnológica del Chocó “Diego Luis Córdoba” to digitalise some of the most endangered colonial records of the region (Fig. 9.2). The project captured images from the First Notary of Quibdó and the Notary of Buenaventura, a city in the Department of Valle, in southern Colombia. All date from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and many have suffered damage from humidity, fungus and lack of attention in poorly maintained storage space.

Fig. 9.2 The Quibdó team examines a notarial register at the EAP workshop.

Photo by David LaFevor, CC BY.

Africans and their descendants living in Colombia’s remote peripheries like Quibdó received little attention either from the colonial or state-building projects and, later, they were largely ignored in Colombia’s historical narratives. The records recovered by the EAP255 project allow researchers to reconstruct the history of these largely forgotten regions and populations. Notarial documents from the region include land sales, mortgages, and many slave sales that offer interesting data not only about the age, sex, and profession of each slave, but also, occasionally, information about the slave’s past history, physical appearance, characteristics and health.23 These records contain untapped information related to the most important economic activity in the region: gold and platinum mining by black slaves, and the social conditions in the towns and mines developed around this enterprise. They hold registers related to the sale and transfer of property (including slaves), certificates of payment and of debt cancelation, wills, ethnic origin of slaves arriving in Chocó and the south Colombian Pacific, and activities of different state and ecclesiastical actors, including visits by the Inquisition office during the eighteenth century.

These sources also provide important data related to the development of independent communities and maroon settlements and their relationships with Emberá-Wounaan groups that inhabited the area for centuries. Indeed, almost every slave inventory from the eighteenth century lists at least one or two slave runaways. Registers of slave manumission in Chocó date as early as 1720, and after buying their freedom former slaves started migrating to places like the Baudo valley where they formed largely black towns with cultural and social characteristics similar to the palenques established by escaped slaves.24

These communities lived in the most difficult conditions. The Colombian Pacific still has — as it has since reliable records begin — some of the highest morbidity and mortality rates of any place in the Americas. This should not be surprising given the harsh climate of the area, the impoverished conditions in which most of the inhabitants of the region still live, and the violence that has characterised the rise and decline of mining and narcotic plantation booms in the region. Starting in the mid-eighteenth century notarial records, most of the registers of slaves’ sales, denunciations for mistreatment, or death registers, also describe the usual roster of diseases that challenged life in the early modern era: yellow fever, malaria, typhus, smallpox, bubonic plague, syphilis and leprosy, among many others. While traveling around the Atrato and San Juan Rivers in the 1820s, French geologist Jean Baptiste Boussingault wrote:

The black sailing my piragua was a magnificent human specimen. However, he had on his thigh an enormous scrofulous, or venereal tumor, a disease that was very common around the places through which we were traveling. […] At around six in the afternoon we disembarked in a Rancheria close to a place called “Las Muchachas”. The blacks who received us were covered in venereal ulcers and disfigured by cancerous afflictions [certainly symptoms of leprosy]. They live very happily as a family when there is a complete nose for ten people. This is a most sad spectacle.25

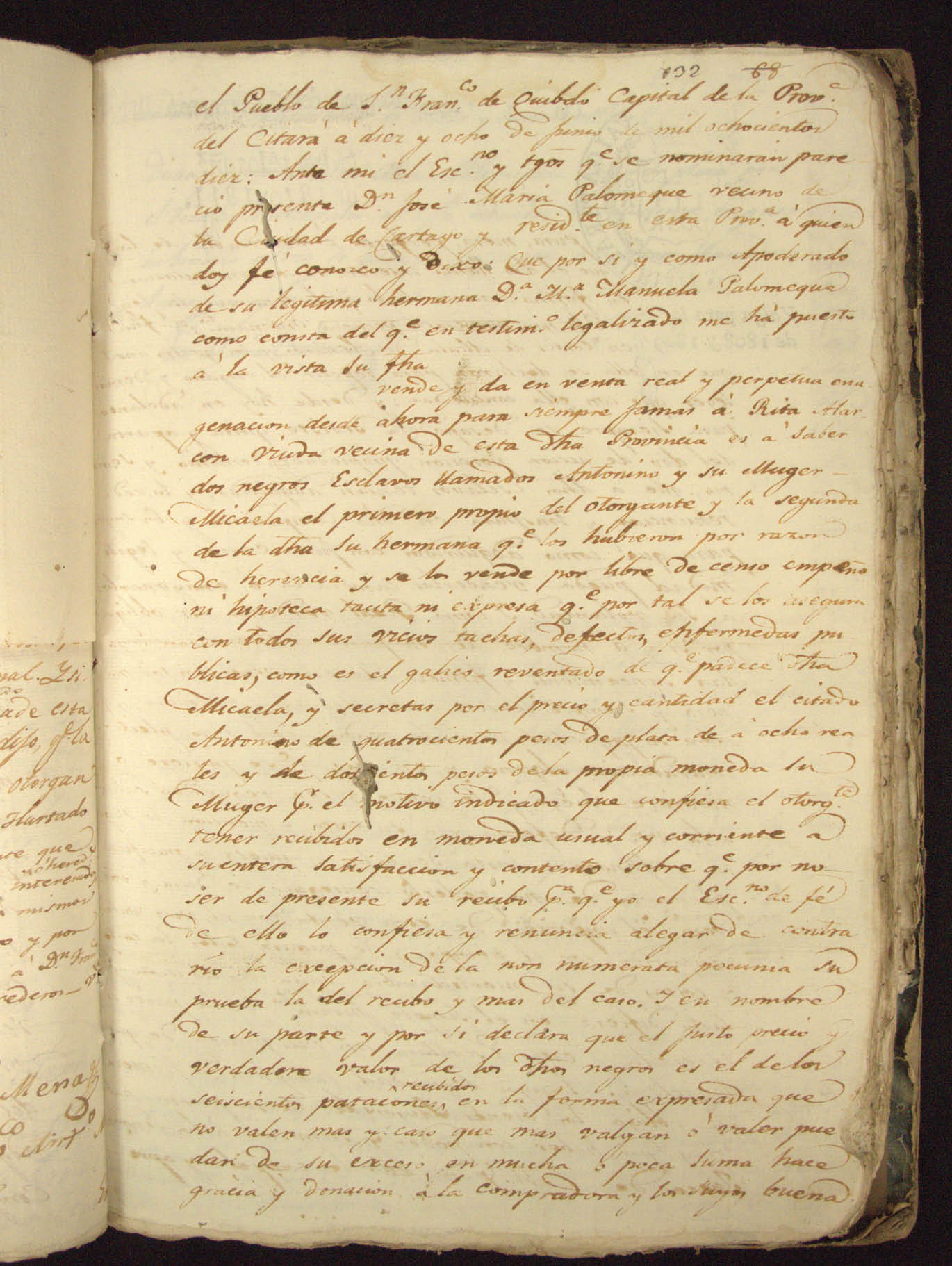

Fig. 9.3 Notarial Document from Quibdó (EAP255/2).

Photo by Quibdó team member, CC BY-NC-ND.

The register of slave sales from Chocó and Buenaventura amply confirm Boussingault’s observations about the prevalence of leprosy. Among the specific designations uniquely referring to leprosy that appear in the records we have digitalised are “galico reventado, llaga, ahoto, gota coral, and tumors”, among others. For instance, Fig. 9.3 provides an example of the sale in 1810 in San Francisco de Quibdó, capital of the province of Citará (today Chocó) of two slaves, Antonino and his wife, Micaela. The seller was José María Palomeque who was registered as a vecino (registered inhabitant) of the city of Cartago, but lived in the province of Citará. Palomeque sold the two slaves to Rita Alarcon, also a resident of Citará for four hundred and two hundred pesos respectively. In the sale document, Palomenque expressly took responsibility for “all the vices, tachas [marks or scars], defects, and public diseases, such as it is the galico reventado [my emphasis] of which said Micaela suffers and other hidden ones [they might have]”.26

Hundreds of similar records contain information about the different diseases suffered by communities of free and enslaved blacks, with most of the cases pertaining to leprosy and/or syphilis. The records coming from the Colombian Pacific also illustrate the dynamics of community formation in these rancherias that were outside the purview of the state. They add an important chapter to the historiography of public health in the country, centered, in this case, on descriptions of leprosarium and the “aldeas de leprosos” (villages of lepers) in the Andes and northern Colombia.27

Eighteenth and nineteenth-century slave trading records from Chocó and the Colombian Pacific include cases of masters who had to sell their slaves for a reduced price due to the lesions produced by leprosy. These cases are probably but a fraction of the real incidence of the disease in the population. Except for anecdotal reports coming from travellers like Boussingault, there is virtually no information, outside the records saved by the EAP255 project, regarding the health conditions, or for that matter, economic, demographic and social conditions of the black population of these villages on the banks of the Atrato and San Juan Rivers at that time. The isolation of most of the towns in the Chocó and the Valle del Cauca gave rise to communitarian models for the perception of disease that emerged spontaneously and preceded mandatory isolationist projects that public health officials enacted during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

The early twentieth century saw the consolidation of the Colombian State, the formation of a national bourgeoisie and the inclusion of the nation within the world economy through the expansion of coffee exports. Modernisation of the country became a national priority, for which leprosy was an obstacle. According to nineteenth century publications on the geography of leprosy, Colombia competed with India for primacy in terms of incidence of the disease — a contest that the Colombian elites refused to win. If Colombia was seen by outsiders as a pestilent country, a “leprosarium” in the words of none other than Gerard Amauer Hansen, the Norwegian scientist who discovered the mycobacterium causing the disease, Chocó became increasingly portrayed as a place inhabited by sick black people.28

While the Chocó’s early settlers struggled to exploit the gold and platinum mines and survive its hostile environment and inhabitants, the lesser frequented, and less settled northeastern coasts of Colombia, first noted as a source of pearls, became infamous in the later sixteenth century as sites of contraband, piracy and illegal slave importations.29 Nuestra Señora de los Remedios del Río de la Hacha, later known simply as Riohacha, was said to be “rich only in pearle and cattell”.30 Its beleaguered governor reported it suffered repeated attacks by “the cruelest Indians of these regions”.31 Riohacha also suffered frequent attacks by French and English pirates and smugglers. In the 1560s, John Hawkins illicitly sold slaves seized in Sierra Leone to local pearl fishermen and, in 1596, his kinsman, the famous English pirate Francis Drake, sacked Riohacha and sailed away with 100 African slaves as part of his booty.32 Riohacha remained a smuggling centre in the seventeenth century for buccaneers such as Henry Morgan sailing out of newly-English Jamaica.33

In this Caribbean port, as in the mines of the Chocó and on the Magdalena River of the central valley, African slaves soon replaced native labourers, working primarily as divers in the coastal pearl fisheries. Conditions were brutal and many of the enslaved, like their counterparts elsewhere in Colombia, soon fled their misery eastward to the La Guajira Peninsula where they joined indigenous rebels fighting their mutual Spanish oppressors.34

Although Riohacha’s pearl fisheries were eventually exhausted, smuggling continued along Colombia’s northern coast throughout the eighteenth century. Riohacha became part of a wider Caribbean and Atlantic commercial network of informal trade and smuggling, centred on nearby Jamaica and Curaçao. The bulk of this highly profitable, but in Spanish law, illicit, trade was in livestock (horses, cattle, mules and goats), textiles and slaves.35 In 1717, Spain’s Bourbon Reformers attempted to regain economic and political control of the region by making Riohacha part of the newly created Viceroyalty of New Granada, but based on his extensive research in Spanish colonial treasury accounts, Lance Grahn argues that “as much if not more, contraband passed through Riohacha than any other single region in the Spanish New World”.36

East of Riohacha, the La Guajira Peninsula jutted northward into the Caribbean and closer, still, to British commercial centres. The Wayúu Indians controlled the Guajira Peninsula and long resisted Catholic evangelisation and Spanish domination. The peninsula existed in a state of almost permanent war well into the eighteenth century and the beleaguered Spanish governor Soto de Herrera referred to the Wayúu as “barbarians, horse thieves, worthy of death, without God, without law and without a king.”37 A large Spanish force sent from Cartagena in 1771 “to reduce the rebellious Guajiros to obedience through respect for Spanish military might” thought better of a fight when met with more than seven times their number of Indians armed with British guns.38 The fierce Wayúu acquired many of those guns through adept contraband trade in pearls and brazilwood.39 The Wayúu also acquired contraband slaves from British and Dutch merchants. For example, in 1753, Pablo Majusares and Toribio Caporinche, two powerful Wayúu chiefs living in the northern region of the Guajira Peninsula, owned eight African slaves who they employed in pearl fishing.40 Other slaves belonging to them were destined for service in the Wayúu’s feared military force.41

Fig. 9.4 Project directors and University of Cartagena student team at EAP workshop. Photo by Mabel Vergel, CC BY-NC-ND.

EAP503: Creating a digital archive of a circum-Caribbean trading entrepôt: notarial records from La Guajira42 enabled students from the Universidad de Cartagena, under the supervision of José Polo Acuña and assistants Mabel Vergel and Diana Carmona to digitalise notarial documents that show that slaves continued to be important in the economy of nineteenth-century Riohacha (Fig. 9.4).43 Documents from the Notaría Primera of Riohacha offer numerous examples of slave transactions. For example, on 23 March 1831, the widow Ana Sierra sold a 25-year-old mulatta slave named Felipa to Maria Francisca Blanchard, a merchant in Riohacha, for 250 pesos.44 Sometime later, Blanchard sold the same slave to Miguel Machado for 200 pesos, although the documents offer no clues as to why the slave’s price dropped.45 The same Miguel Machado appears again in the notarial documents when he bought a seventeen-year-old slave named Francisco Solano from Maria Encarnacion Valverde for 100 pesos. Francisco was the son of another slave who served in Valverde’s household.46

These notarial records also document links between merchants in Riohacha and their factors in the islands of Aruba, Curacao and Jamaica, and show how authorities in Riohacha were able to strengthen their grip on the fertile lands located south of the Rancheria River through peace treaties with formerly hostile indigenous groups. Peace allowed for the southward expansion of the agricultural and cattle ranching frontier, increased production for internal consumption and commercial exchange, and the further integration of Riohacha. As Bourbon reformers of the eighteenth century attempted to halt smuggling and encourage development in Riohacha, they also established new towns to help support their most important port of Cartagena de Indias. Some of the new towns located south of Cartagena in the Department of Córdoba were connected to it via the Sinú River, which also connected the southern towns to the Atrato River, Quibdó and the Pacific.47

The EAP640 project also enabled teams from the University of Cartagena to digitalise ecclesiastical records from the churches of Santa Cruz de Lorica and San Jerónimo de Buenavista in Montería in the Department of Córdoba in northern Colombia (Figs. 9.5 and 9.6).48

Fig. 9.5 Endangered ecclesiastical records from the Iglesia de Santa Cruz de Lorica, Córdoba. Photo by Cartagena team member, CC BY-NC-ND.

Fig. 9.6 Students learn to film endangered records at Vanderbilt’s digital workshop at the University of Cartagena. Photo by David LaFevor, CC BY.

Montería was established in the eighteenth century along the Sinú River, which links it to the Caribbean Sea. It is noted as a ranching capital and also an ethnically and culturally diverse region where Zenú Indians and descendants of Spaniards and Africans all interacted. An official history of Montería states that two different delegations of Zenú Indians presented their chiefs’ petitions to the governors of Cartagena asking that the Spanish town be established in their territory.49

Fig. 9.7 Cathedral of San Jerónimo de Buenavista, Montería, Córdoba.

Photo by Mabel Vergel, CC BY-NC-ND.

The ecclesiast records of San Gerónimo de Buenavista (as it was earlier spelled) (Fig. 9.7) provide insights into one of the most ethnically diverse areas of Córdoba. The Catholic church mandated the baptism of African slaves in the fifteenth century and extended this requirement across the Catholic Americas. Once baptised, Africans and their descendants were also eligible for the sacraments of marriage and a Christian burial.50 Baptism records such as the one below give the date of the ceremony, the name of the priest performing it, the name of the person baptised (whether child or adult), the parents’ names if known, and whether the child or adult was born of a legitimate marriage, or was the “natural” child of unmarried parents. Priests also noted if the baptism was performed “in case of necessity”, allowing researchers to track epidemic cycles. The names of the baptised person’s godparents are also given in these records. Godparents had the responsibility for helping raise their godchild in the Catholic faith, and in case of the parents’ deaths, they were to raise the child as their own. Thus, community networks can be traced through patterns of compadrazgo (godparentage).

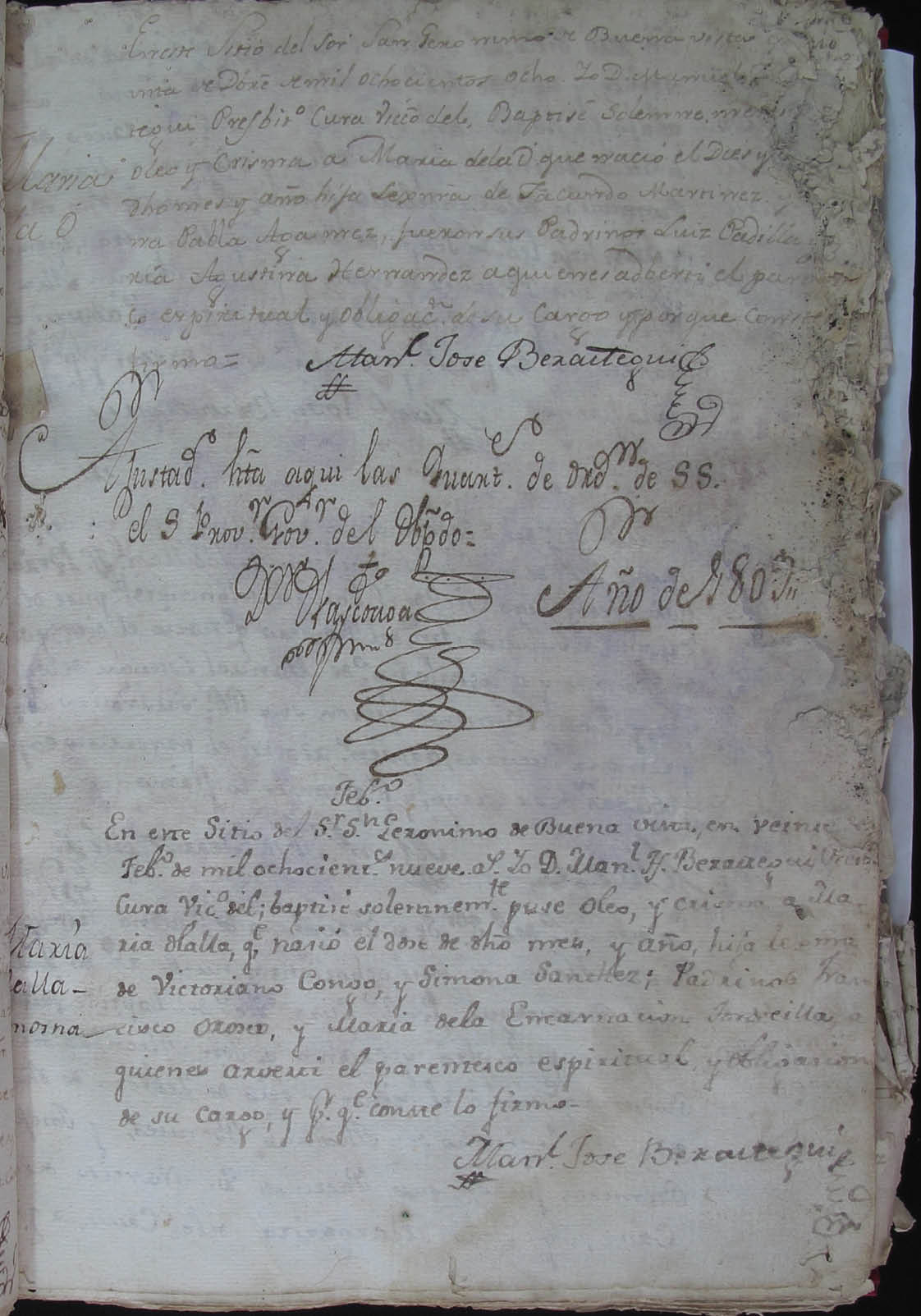

Fig. 9.8 Baptism document of Maria Olalla, San Jerónimo de Buenavista Cathedral, Montería, Córdoba (EAP640). Photo by Cartagena team member, CC BY-NC-ND.

The records of San Gerónimo de Buenavista, unlike those from other Caribbean sites, do not specifically note the race of the person baptised, supporting modern theories about the historical invisibility of Afro-Colombians. However, researchers can at times find racial clues in the names of parents. In Fig. 9.8, the priest, Don Manuel José Beractegui, baptises the legitimate child, María Olalla, born on 12 February 1809 to parents Victoriano Congo and his wife, Simona Sánchez. That the father bore an ethnic surname suggests that he is African-born, or at least not recognised as fully acculturated. However, he is a free man; otherwise his enslaved status would have been noted. A notation to the left of the entry indicates that the baptism was performed as an act of charity, meaning that the parents could not afford the standard ecclesiastical fee.51

As Spaniards explored, exploited and finally colonised the northern coast of what is today Colombia, the Portuguese followed similar patterns along Brazil’s northeastern coast. Despite challenges from French and Dutch competitors in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Portuguese successfully colonised Brazil, transferring techniques of sugarcane cultivation and slaves from West and Central Africa to the coast of Brazil.52 Brazil’s early sugar cultivation concentrated along its northeastern coast.53 The region’s settlers exported sugar and other products and imported goods and enslaved Africans through the major port cities of Recife, Olinda and Salvador, but sugar mills were scattered throughout the countryside and smaller cities also supplied sugar for export. Settlers deep in the sertão (backlands) also raised livestock for local consumption.54

The history of the state of Paraíba (situated to the north of Pernambuco and to the south of Rio Grande do Norte and Ceará) has received less attention than that of its northeastern neighbours despite its interest and significance for Brazilian and Atlantic World history (see Fig. 9.9 for a map of colonial Paraíba and Fig. 9.10 for a map of modern-day Paraíba).55 When the Portuguese Crown formed the Capitania of Paraíba in 1574, French settlers still lived in the region, and the competing Europeans soon allied with warring indigenous nations to battle one another.56 The Portuguese defeated the French and the Potiguar Indians in 1584 and established the city of Nossa Senhora das Neves, which became the political centre of Paraíba, and which is today João Pessoa.57 After a brief Dutch occupation of some coastal areas of Paraíba from 1634 to 1654, the Portuguese expanded into the interior sertão in the late seventeenth century. The names and dates of the first settlers to the region are unknown but they clustered along river routes to raise livestock and routinely battled the Cariri and Tarairiu Indians.58

Fig. 9.9 Nova et Accurata Brasiliae Totius Tabula made in 1640 by Joan Blaeu. Note the Capitania de Paraiba, highlighted on the northeastern coast. Ministério das Relações Exteriores do Brasil, Public Domain (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blaeu1640.jpg).

Fig. 9.10 Map of Paraíba, highlighting São João do Cariri in the interior and João Pessoa on the coast, created by Courtney J. Campbell, CC BY-NC-ND.

The interior town of São João do Cariri received its first official land grant in December 1669 for a place referred to simply as “Sítio São João”, but this land was probably settled prior to this date. Settlers built the town centre near where the Rio da Travessia (now the Rio Taperoá) and the Riacho Jatobá meet. When the parish church was built in 1750, the town was re-named Travessia dos Quatro Caminhos (Crossing of Four Roads).59 The town’s settlers dedicated themselves to raising livestock (cows, horses, sheep and goats) and cultivating cotton, cereals and manioc.60 The area also developed an important internal market of manioc flour, the liquor known as aguardente, and compressed sugar. Traveling salesmen with convoys of donkeys distributed these products throughout the hinterland towns.61 When the parish of Nossa Senhora dos Milagres da Ribeira do Cariri (later Nossa Senhora dos Milagres do São João do Cariri) was founded by the Jesuits in 1750, and its church constructed in 1754, it became the largest parish in Paraíba.62

Although we know from church records that São João do Cariri had a significant number of enslaved Africans and people of African descent, there is surprisingly little in the historical literature of the region about this population. That historians have only recently begun to emphasise the importance of reconstructing and analysing the history of this population is not surprising, given their subaltern status. The enslaved Africans of the sertão were doubly oppressed: first by the institution of slavery and the slave trade, and then by the cruelty of the recurrent droughts in the region which left their population especially exposed, abandoned and affected. These recurrent droughts killed livestock and slaves and created a cycle of poverty in the region from which, some would say, it has never fully recovered.63

To better understand the relationship between the sertão, the coastal colonies and the cities in Brazil’s colonial and imperial history — and to analyse the role of indigenous and Afro-Brazilian populations in the development of the region’s economy, culture and history — researchers must consult the oldest documents remaining in the northeastern region. Unfortunately, as the examples that follow demonstrate, these sources are frequently in poor condition and in danger of disintegrating or disappearing within the next decade. To mitigate this fate, in 2013 a team of researchers supported by the EAP627 project began digitising documents from the Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Paraibano (IHGP) in João Pessoa, the Arquivo Histórico Waldemar Bispo Duarte in João Pessoa, and the Paróquia de Nossa Senhora dos Milagres do São João do Cariri (Fig. 9.11).64

Fig. 9.11 Students from the Universidade Federal da Paraíba filming ecclesiastical records from Nossa Senhora dos Milagres do São João do Cariri (EAP627).

Photo by Tara LaFevor, CC BY.

The IHGP holds volumes of correspondence between royal officials in Portugal and colonial administrators in João Pessoa, administrative records, notarial registers, volumes of land grants ceded by Portuguese royalty to colonials, maps, and some photography. The Arquivo Histórico Waldemar Bispo Duarte, also in João Pessoa, houses correspondence, and administrative and notarial records referring to colonial administration, the sale of slaves and land grants. Finally, the Paróquia de Nossa Senhora dos Milagres in São João do Cariri, in the backlands, holds baptismal, marriage, death, communion and church financial records.

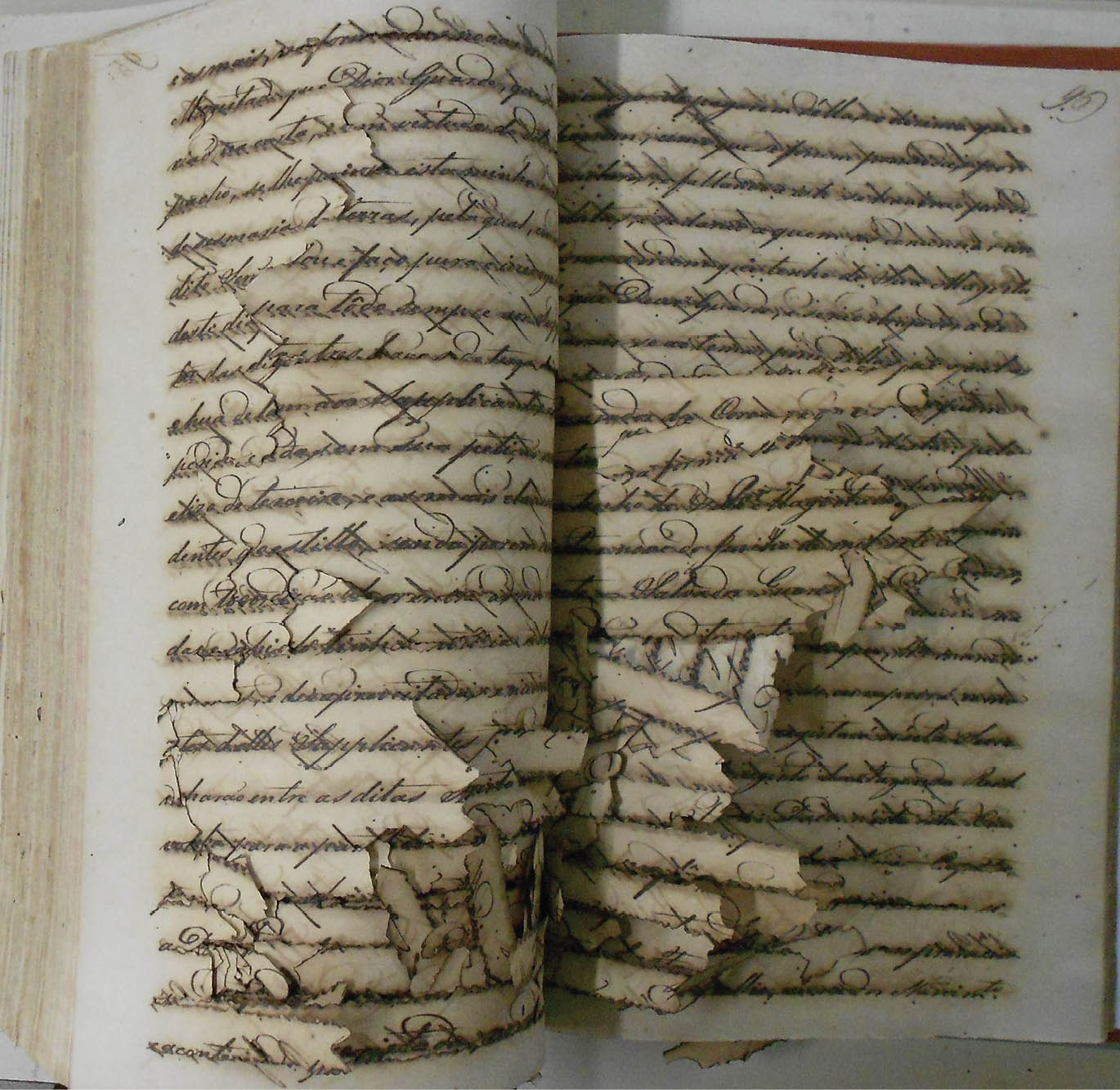

As demonstrated in Fig. 9.12, the sesmaria (land grant) records held at the IHGP and especially at the Arquivo Histórico Waldemar Bispo Duarte are in such precarious condition that they are no longer made available to researchers. The iron-based ink originally used to record these documents has oxidised, eating through the paper and leaving fragile, brittle pages that either break into strips or seem to disintegrate at the slightest touch. Preserving a digital copy of these records, then, is the only way to ensure further research in these documents.

Fig. 9.12 Sesmaria (land grant) document from Paraíba (EAP627).

Photo by Courtney J. Campbell, CC BY-NC-ND.

A sesmaria was a type of land grant by the Portuguese Crown to petitioners throughout the Portuguese Atlantic World, including Brazil and Angola, from 1375 to 1822.65 Colonial subjects (who were often already in unofficial possession of the land) had to petition the governor for these land grants. The governor would respond to the petition with a letter determining a period by which the petitioner had to cultivate the land and, once the petitioner had met these requirements, he or she would send a new petition to the King who would confirm the sesmaria. These grants came with strings attached: in order to maintain ownership of the land, the landowner had to cultivate it productively; otherwise, the Portuguese Crown would rescind the grant.66 Carmen Alveal found that the Crown granted sesmarias to “men, women, Indians, mestiços [persons of European and indigenous descent], free Africans, clergy, new Christians [that is, Jewish converts to Christianity], soldiers, [and] religious and civil institutions”.67 The grants affected not only the petitioners and land grantees, but also the free and enslaved labourers who worked the lands.

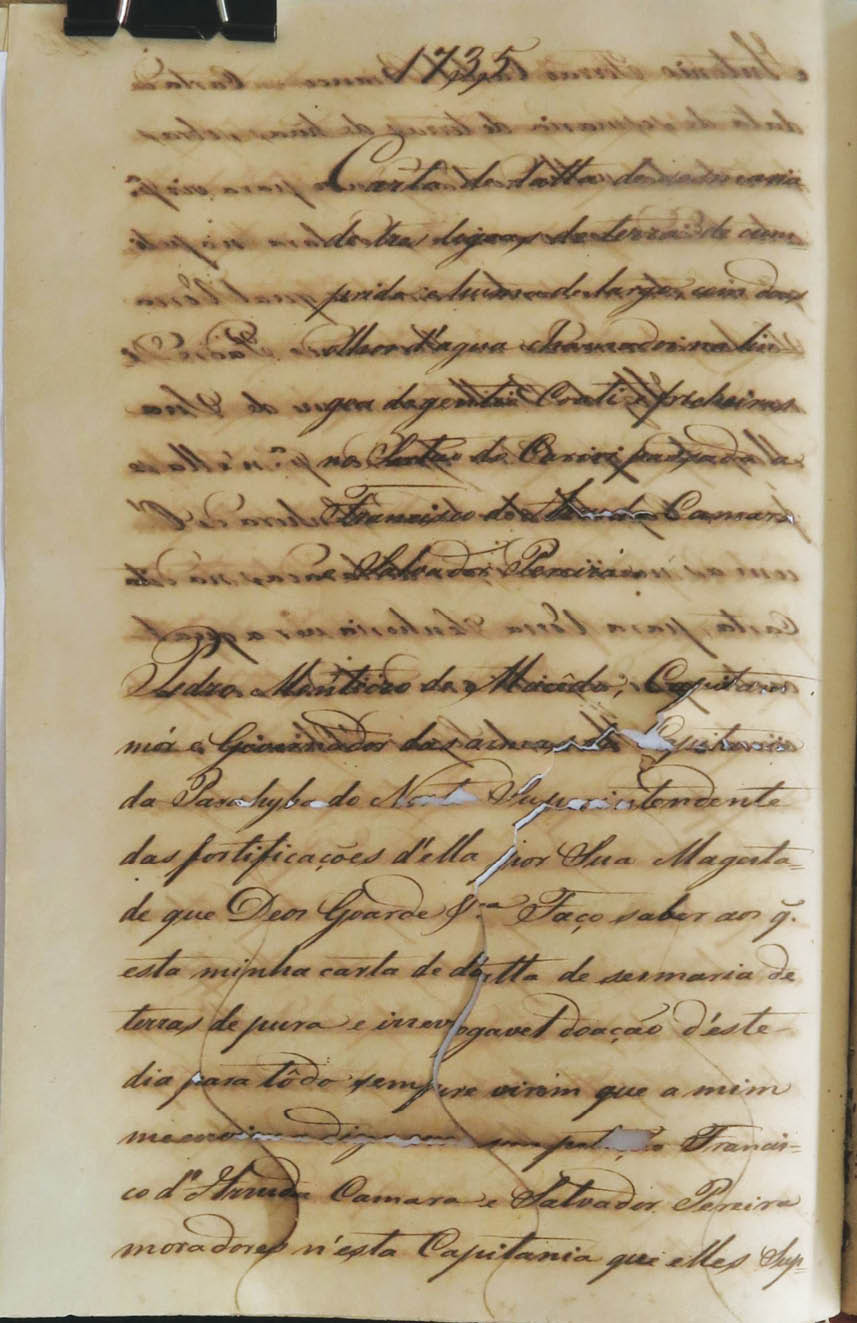

Fig. 9.13 Sesmaria document from Paraíba (EAP627).

Photo by Paraíba team member, CC BY-NC-ND.

Through further study of these documents, researchers might come to a better understanding not only of the colonial period, but also of the unequal land distribution that persists in Brazil today. For example, the document in Fig. 9.13 housed at the Arquivo Histórico Waldemar Bispo Duarte, describes a sesmaria grant that was “three leagues long and one wide with two springs called Coati and Fricheira in the heathen language in the Sertão do Cariri” to a man named Francisco de Arruda Camara e Salvador Pereira in March of 1735. While these land grants are fairly formulaic, we learn particular details from each. The sesmaria above provides the name of the grantee and grantor, the size of the grant, and the ways of measuring the land (“running from sun-up [East] to sun-down [West]”). The frequent mention of the springs on the property demonstrates the importance of water in this arid region and the necessity to register water sources as territory, while the insistence on the names as belonging to the “heathen language” (Tupi-Guaraní), emphasises that, to understand and describe the layout of the territory, not only the Portuguese colonists, but also the Portuguese Crown had to adopt indigenous terminologies. This grant also describes the land as “uncultivated and not used to advantage”, the state of the land as “brush and shrub”, and the purpose of granting as “settlement”. Finally, the inclusion in this letter of handwritten copies of other letters exchanged with various authorities about this particular grant allows the reader to witness the various levels of bureaucracy involved in the granting of one plot of land.

Fig. 9.14 Nossa Senhora dos Milagres do São João do Cariri Church (EAP627). Photo by David LaFevor, CC BY.

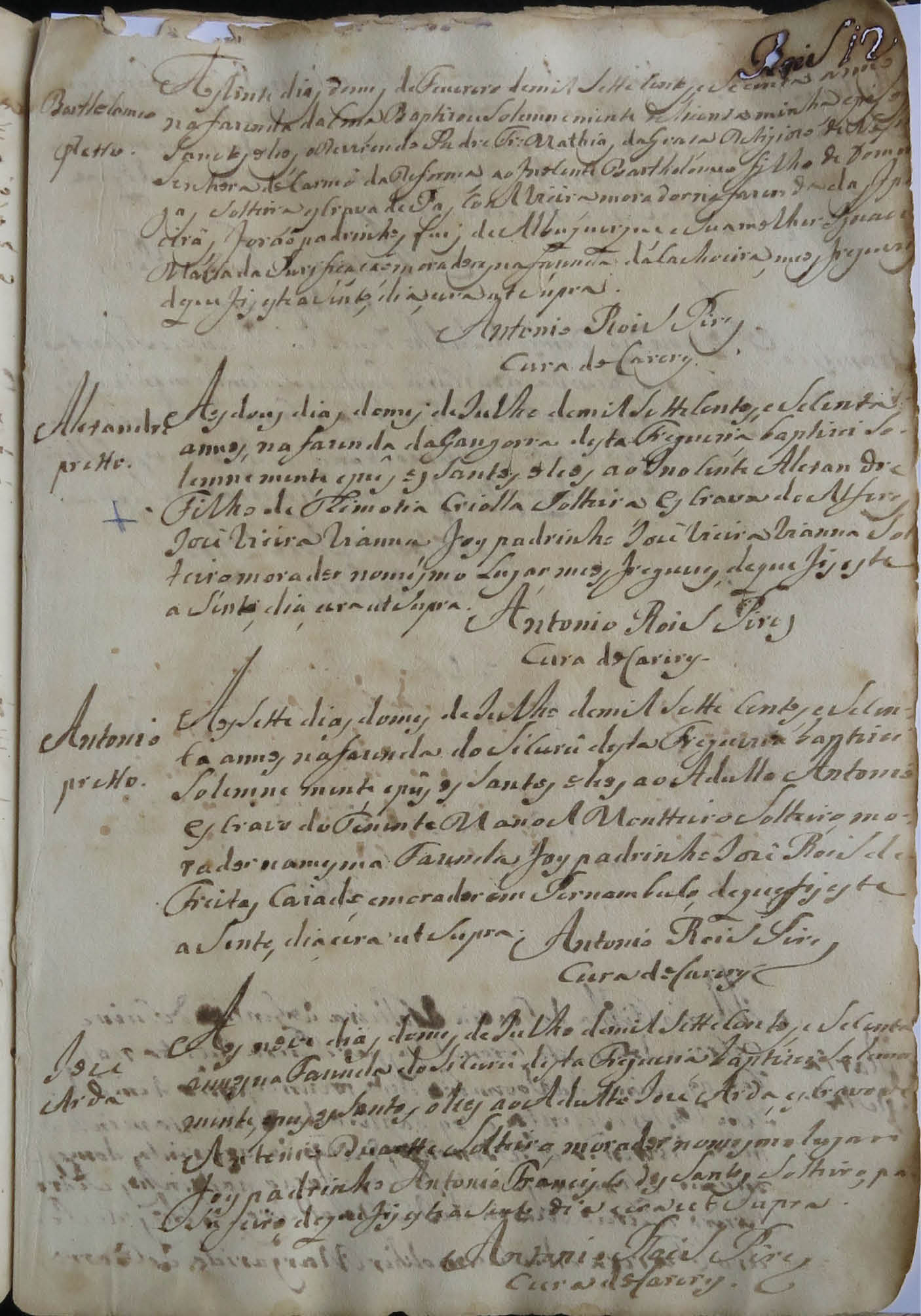

Fig. 9.15 Book of Baptisms, Marriages and Deaths, 1752-1808, from Paróquia de Nossa Senhora dos Milagres do São João do Cariri Paraíba (EAP627).

Photo by Paraíba team member, CC BY-NC-ND.

Fig. 9.16 Book of Baptisms, Marriages and Deaths, 1752-1808, from Paróquia de Nossa Senhora dos Milagres do São João do Cariri Paraíba (EAP627).

Photo by Paraíba team member, CC BY-NC-ND.

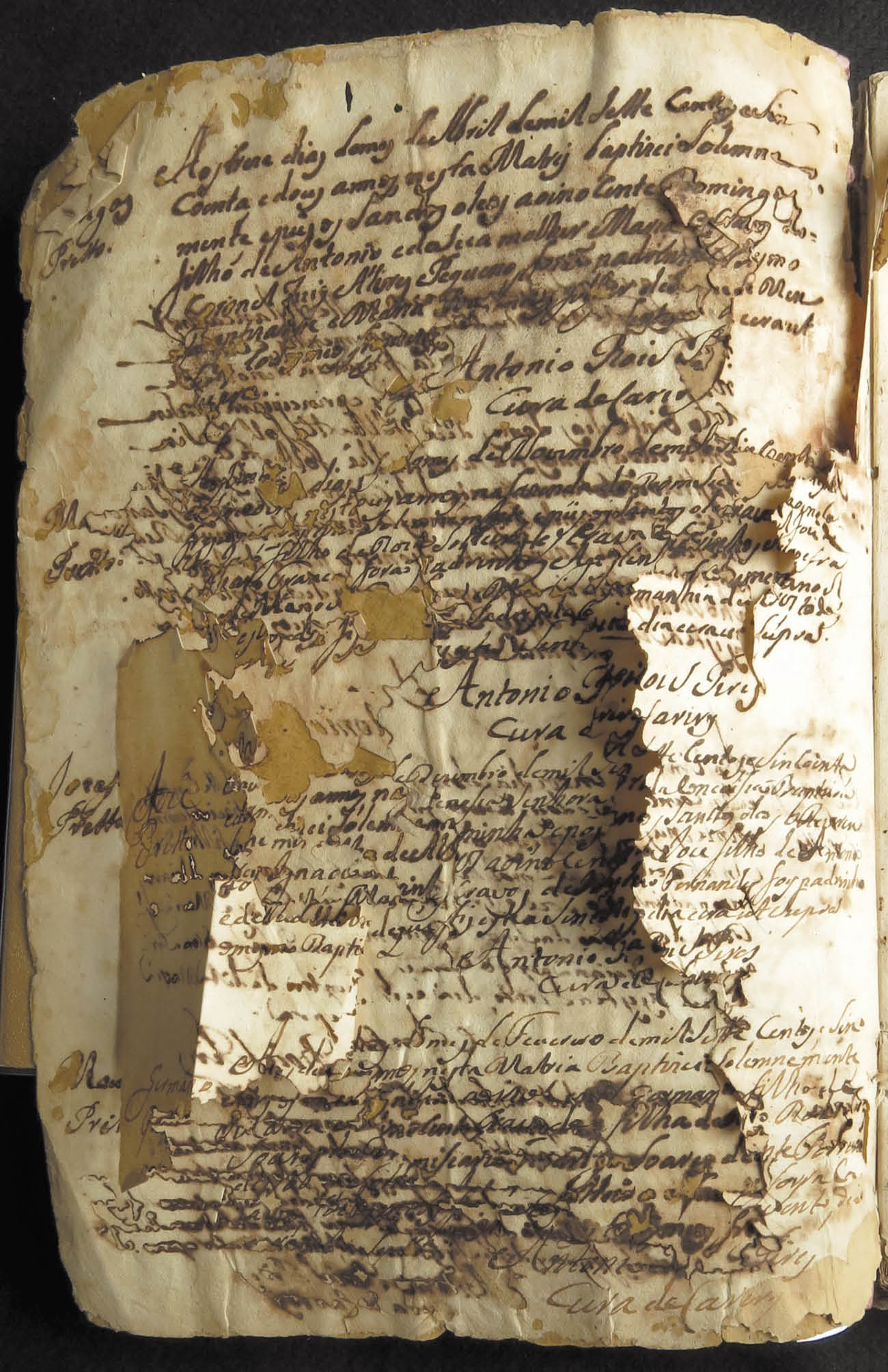

Ecclesiastical documents are also essential sources for studying populations that have not been proportionately represented, including enslaved Africans and Indians, mixed-race and indigenous slaves and labourers, free workers, and poor farmers.68 The pages above (Figs. 9.15 and 9.16), for example, come from the oldest book of baptisms, marriages and deaths of the Paróquia de Nossa Senhora dos Milagres do São João do Cariri, the Livro 1: Batizados, casamentos e óbitos anos de 1752 a 1808. This volume is in a particularly damaged state, suffering from both insect damage and oxidisation of iron-based ink, with the above page being one of the few that is in one piece and fully legible.

Recognising the historical value of the documents, the church agreed to allow our team to digitise and make available online the 55 volumes they house in a small cabinet in the parish office (Fig. 9.14). The collection at this parish includes bound, handwritten records related to baptisms (1752-1928), marriages (1752-1931), deaths (1752-1931), confirmations (1778-1816) and genealogy (1891-1917) of the white, black, Indian, mixed, free, freed, and slave populations from the region, including Africans from the Mina Coast, “Guinea” and Angola. It also includes documents referring to the parish finances (1766-1861). Of particular interest in this book are the terms used to describe those baptised, married or buried. Baptismal records describe adults and children as enslaved and freed, legitimate or not, Brazilian-born, African, black, “pardo” (of mixed ancestry), mulatto, “cabra”, “curiboca”, “mestiço” (of mixed ancestry), and even “vermelho” (red), demonstrating the commonplace nature of racial mixing and the very rootedness of miscegenation in the hinterlands of Paraíba in the eighteenth century.

As seen in the legible page above, parish priests baptised not only children (referred to as “innocents”), but also adult Africans. At times, slaves also served as godparents. Marriage records from the same book include marriages between and among free and enslaved men and women from the parish and from outside of it, and include Brazilian-born Africans, Indians from the Nação (nation) Cavalcantes, and Africans from the Coast of Mina, “Guinea” and Angola. We also learn from this document details about the layout of the region, the names of the fazendas (ranches), and the names of smaller chapels where burials were also performed.69

Baptismal records have already begun to inform academic research on this region. For example, Maria da Vitória Barbosa Lima examines the meanings of freedom among the free and enslaved black population working in the livestock- and sugar-producing areas of nineteenth-century Paraíba. She demonstrates that slaves often tried to purchase freedom or escape, while the poor black population lived precariously on the edge of freedom and slavery.70 Solange Pereira da Rocha’s study of free and enslaved black populations of nineteenth-century Paraíba analyses baptismal records, focusing on formal and informal kinship and family formation among both free and enslaved black residents.71 Rocha finds that slaves advanced their positions “with the weapons at their disposal – such as intelligence and astuteness”.72

One of these weapons was the creation of kinship ties through baptism. Slaves used baptism to establish kinship relations with free people in an attempt to seek freedom, or, at the very least, to create social conditions that eased their survival in captivity.73 Solange Mouzinho’s forthcoming Master’s dissertation relies primarily on ecclesiastical records from the Paróquia de Nossa Senhora dos Milagres do São João do Cariri digitalised by the British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme.74 Her research examines how enslaved men, women and children in Vila Real de São João do Cariri related with others – whether enslaved, freed or free – through religious life. Mouzinho’s research will give insight into the family and social relations that the enslaved population of the region created and influenced, and within which they lived and worked. Through these historical studies, based on ecclesiastical sources, we learn about the lives, social relations and culture of the enslaved African and Afro-Brazilian populations of Paraíba.

Yet, it is not only scholars who are interested in these records. As Brazil struggles to come to terms with the legacies of indigenous displacement and African slavery, quilombos (maroon-descended communities) and indigenous groups might draw upon these records to legally establish their lineage or vindicate their rights. The Fundação Cultural Palmares (FCP) — so named after the famed quilombo called Palmares in Pernambuco (modern-day Alagoas) that resisted colonial domination for over a century — is an agency of the Brazilian Ministry of Culture dedicated to “promoting the cultural, social and economic values resulting from black influence in the formation of Brazilian society”.75 The FCP was established by the Constitution of 1988, and has the official mission of “preserving, protecting and disseminating black culture, with the aim of inclusion and for the development of the black population in the country”.76 Toward this end, one of the FCP’s specific actions is to carry out research, studies and surveys about Afro-Brazilian cultural legacies. The FCP also is in charge of protecting the legal rights of quilombos and pulling together the documentation necessary to support their historical justification. Ecclesiastical records, like those used to support the research of Lima, Pereira, and Mouzinho, are fundamental in the preservation of Afro-Brazilian patrimony.

Further, social movements dedicated to restoring lands granted by sesmaria to indigenous groups rely on historical documents to make their claims. The best-known of these groups, the Tabajara of Paraíba, have been struggling since 2006 to reclaim lands granted to them by sesmaria in the seventeenth century. By combining data from historical sources with GIS and satellite technologies, the Tabajara and socially-dedicated scholars have joined forces with some humble, yet significant successes.77 Making the records digitalised by the EAP freely available through the Ecclesiastical and Secular Sources for Slave Societies online archive not only preserves historical patrimony, but also offers legal support to groups struggling with the economic, social, cultural and legal legacies of Brazil’s history of colonisation and slavery.

References

Acosta Saignes, Miguel, Vida de los esclavos negros en Venezuela (Caracas: Hespérides, 1967).

Almeida, José Américo de, A Paraíba e seus problemas, 3rd edn. (João Pessoa: Estado da Paraíba, Secretaria da Educação e Cultura, Diretoria Geral da Cultura, 1980 [1923]).

Alveal, Carmen Margarida Oliveira, Converting Land into Property in the Portuguese Atlantic World, 16th-18th Century (Ph.D. thesis, Johns Hopkins University, 2007).

Andrews, Kenneth R., The Spanish Caribbean: Trade and Plunder, 1530-1630 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1978).

Andrews, K. R., The Last Voyage of Drake and Hawkins (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1972).

Araújo, Ismael Xavier de, Viviane dos Santos Sousa, Roméria Santana da Silva Souza, Jeremias Jerônimo Leite, Tânia Maria de Andrade and Rodrigo Lira Albuquerque dos Santos, “Processo de emergência étnica: povo indígena Tabajara da Paraíba”, Palmas, Tocantins (2012), http://propi.ifto.edu.br/ocs/index.php/connepi/vii/paper/view/2110/1626

Barrera Monroy, Eduardo, “La Rebelión Guajira de 1769: algunas constantes de la cultura Wayuu y razones de su pervivencia”, Revista Credencial Historia (June, 1990), http://www.banrepcultural.org/blaavirtual/revistas/credencial/junio1990/junio2.htm

—, Mestizaje, comercio y resistencia: La Guajira durante la segunda mitad del siglo XVIII (Bogotá: Instituto Colombiano de Antropolgía e Historia, 2000).

Bassi Arevalo, Ernesto, Between Imperial Projects and National Dreams: Communication Networks, Geopolitical Imagination, and the Role of New Granada in the Configuration of a Greater Caribbean Space, 1780s-1810s (Ph.D. thesis, University of California, Irvine, 2012).

Borrego Plá, María del Carmen, Cartagena de Indias en el Siglo XVI (Seville: Escuela de Estudios Hispano-Americanos, 1983).

Campbell, Courtney J., “History of the Brazilian Northeast”, in Oxford Bibliographies in Latin America, ed. by Ben Vinson (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

Castillo Mathieu, Nicolás del, “Población aborigen y conquista, 1498-1540”, in História Económica y Social del Caribe Colombiano, ed. by Adolfo Roca Meisel (Bogotá: Ediciones Uninorte-ECOE, 1994).

Eakin, Marshall, Brazil: The Once and Future Country (New York: St Martin’s Griffin, 1997).

Grahn, Lance R., “An Irresoluble Dilemma: Smuggling in New Granada, 1713-1763”, in Reform and Insurrection in Bourbon New Granada and Peru, ed. by John R. Fisher, Allan J. Kuethe and Anthony McFarlane (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1990), pp. 123-46.

—, The Political Economy of Smuggling: Regional Informal Economies in Early Bourbon New Granada (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1997).

Helg, Aline, Liberty and Equality in Caribbean Colombia, 1770-1835 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2004).

Hernández Ospina, Mónica Patricia, “Formas de territorialidad Española en la Gobernación del Chocó durante el siglo XVIII”, Historia Crítica, 32 (2006), 13-37.

Heywood, Linda M. and John K. Thornton, Central Africans, Atlantic Creoles, and the Foundation of the Americas, 1585-1660 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Jiménez, Orián, “El Chocó: Libertad y poblamiento, 1750-1850”, in Afrodescendientes en las américas: trayectorias sociales e identitarias: 150 años de la abolición de la esclavitud en Colombia, ed. by Claudia Mosquera, Mauricio Pardo and Odile Hoffman (Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2002), pp. 121-41.

Landers, Jane, “The African Landscape of 17th Century Cartagena and its Hinterlands”, in The Black Urban Atlantic in the Age of the Slave Trade (The Early Modern Americas), ed. by Jorge Cañizares-Ezguerra, James Sidbury and Matt D. Childs (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), pp. 147-62.

—, “African ‘Nations’ as Diasporic Institution-Building in the Iberian Atlantic”, in Dimensions of African and Other Diasporas, ed. by Franklin W. Knight and Ruth Iyob (Kingston: University of the West Indies Press, 2014), pp. 105-24.

Lane, Kris E., Pillaging the Empire: Piracy in the Americas 1500-1750 (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1998).

Leal, José, Vale da Travessia, 2nd edn. (João Pessoa: Editora e Gráfica Santa Fé, 1993).

Lima, Maria da Vitória Barbosa, Liberdade interditada, liberdade reavida: escravos e libertos na Paraíba escravista (século XIX) (Brasília: Fundação Cultural Palmares, 2013).

Machado Caicedo, Martha Luz, La escultura sagrada chocó en el contexto de la memoria de la estética de África y su diaspora: ritual y arte (Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2011).

Martínez Martín, Abel F., El lazareto de Boyacá: lepra, medicina, iglesia y estado 1869-1916 (Tunja: Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia, 2006).

McFarlane, Anthony, Colombia Before Independence: Economy, Society and Politics under Bourbon Rule (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

Mello, José Octávio de Arruda, História da Paraíba, 11th edn. (João Pessoa: A União, 2008).

Mendes, António de Almeida, “The Foundation of the System: A Reassessment of the Slave Trade to the Spanish Americas in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries”, in Extending the Frontiers: Essays on the New Transatlantic Slave Trade Database, ed. by David Eltis and David Richardson (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008), pp. 63-94.

Moreno, Petra Josefina, Guajiro-Cocinas: Hombres de historia 1500-1900 (Ph.D. thesis, Complutense University, Madrid, 1984).

Moreno de Ángel, Pilar, Antonio de la Torre y Miranda Viajero y Poblador (Bogotá: Planeta Colombiana Editorial, 1993).

Mosquera, Sergio A., Memorias de los Ultimos Esclavizadores en Citará: Historia Documental (Carátula: Promotora Editorial de Autores Chocoanos, 1996).

—, “Los procesos de manumisión en las provincias del Chocó”, in Afrodescendientes en las américas: trayectorias sociales e identitarias: 150 años de la abolición de la esclavitud en Colombia, ed. by Claudia Mosquera, Mauricio Pardo, and Odile Hoffman (Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2002), pp. 99-120.

—, Don Melchor de Barona y Betancourt y la esclavización en el Chocó (Quibdó-Chocó: Universidad Tecnológica del Chocó “Diego Luis Córdoba”, 2004).

—, El Mondongo: Etnolingűística en la historia Afrochocoana (Bogotá: Arte Laser Publicidad, 2008).

Mouzinho, Solange, Parentescos e sociabilidades: experiências de vida dos escravizados no sertão paraibano de São João do Cariri, 1752-1816 (Master’s dissertation, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, 2014).

Newson, Linda A., and Susie Minchin, From Capture to Sale: The Portuguese Slave Trade to Spanish South America in the Early Seventeenth Century (Leiden: Brill, 2007).

Obregón, Diana, “Building National Medicine: Leprosy and Power in Colombia, 1870-1910”, Social History of Medicine, 15/1 (2002), 89-108.

—, “The Anti-leprosy Campaign in Colombia: The Rhetoric of Hygiene and Science, 1920-1940”, História, Ciências, Saúde-Manguinhos, 10 (2003), 179-207.

Ortega Ricaurte, Enrique, Historia documental del Chocó (Bogotá: Editorial Kelly, 1954).

Polo Acuña, José and Ruth Gutiérrez Meza, “Territorios, gentes y culturas libres en el Caribe continental Neograndino 1700-1850: una síntesis”, in Historia social del Caribe Colombiano: Territorios, indígenas, trabajdores, cultura, memoria e historia, ed. by José Polo Acuña and Sergio Paolo Solano (Cartagena: La Carreta Editores, 2011), pp. 13-44.

Polo Acuña, José, Etnicidad, conflicto social y cultura fronteriza en la Guajira, 1700-1850 (Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes, 2005).

—, “Territorios indígenas y estatales en la península de la Guajira (1830-1850)”, in Historia social del Caribe Colombiano: Territorios, indígenas, trabajdores, cultura, memoria e historia, ed. by José Polo Acuña and Sergio Paolo Solano (Cartagena: La Carreta Editores, 2011), pp. 45-71.

Porto, J. Costa, O pastoreio na formação do Nordeste (Rio de Janeiro: Ministério da Educação e Cultura, Serviço de Documentação, 1959).

Purves, David Laing, The English Circumnavigators: The Most Remarkable Voyages Round the World by English Sailors (London: William P. Nimmo, 1874).

Restrepo, Vicente, Estudio sobre las minas de oro y plata de Colombia, 2nd edn. (Bogotá: Banco de la República, 1952).

Rietveld, Padre João Jorge, O verde Juazeiro: história da paróquia de São José de Juazeirinho (João Pessoa: Imprell, 2009).

Rocha, Solange Pereira da., Gente negra na Paraíba oitocentista: população, família e parentesco espiritual (São Paulo: Editora UNESP, 2009).

Romero, Mario Diego, Poblamiento y sociedad en el Pacífico Colombiano siglos XVI al XVIII (Cali: Universidad del Valle, 1995).

Rosero, Carlos, “Los afrodescendientes y el conflicto armado en Colombia: La insistencia en lo propio como alternativo”, in Afrodescendientes en las américas: trayectorias sociales e identitarias: 150 años de la abolición de la esclavitud en Colombia, ed. by Claudia Mosquera, Mauricio Pardo and Odile Hoffman (Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2002), pp. 547-59.

Sabater, Pilar, “Discurso sobre una enfermedad social: La lepra en el virreinato de la Nueva Granada en la transición de los siglos XVIII y XIX”, Dynamis, 19 (1998), 401-28.

Sauer, Carl, O., The Early Spanish Main (London: Cambridge University Press, 1966).

Sharp, William Frederick, “The Profitability of Slavery in the Colombian Chocó, 1680-1810”, The Hispanic American Historical Review, 55/3 (1975), 468-95.

—, Slavery on the Spanish Frontier: The Colombian Chocó, 1680-1810 (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1976).

Soares, Mariza de Carvalho, People of Faith: Slavery and African Catholics in Eighteenth-Century Rio de Janeiro (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011).

Stone, Erin, Indian Harvest: The Rise of the Indigenous Slave Trade from Española to the Circum-Caribbean, 1492-1560 (Ph.D. thesis, Vanderbilt University, 2014).

Tadieu, Jean-Pierre, “Un proyecto utópico de manumission de los cimarrones del ‘Palenque de los montes de Cartagena’ en 1682”, in Afrodescendientes en las américas: trayectorias sociales e identitarias: 150 años de la abolición de la esclavitud en Colombia, ed. by Claudia Mosquera, Mauricio Pardo and Odile Hoffman (Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2002), pp. 169-80.

Wheat, David, Atlantic Africa and the Spanish Caribbean, 1570-1640 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, forthcoming).

1 “Ley 70 sobre negritudes”, cited in Aline Helg, Liberty and Equality in Caribbean Colombia, 1770-1835 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), pp. 1-2; “Lei No. 7.668, de 22 de agosto de 1988”, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/L7668.htm; “Programas e ações”.

2 In 2005, with funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, Vanderbilt University launched a major international initiative to begin locating and preserving ecclesiastical and notarial records of Africans in Cuba and Brazil, Ecclesiastical and Secular Sources for Slave Societies (http://www.vanderbilt.edu/esss/index.php). With funding from the British Library, the project was expanded into Colombia (EAP255, EAP503 and EAP640) and into additional areas of Brazil (EAP627).

3 Carl O. Sauer, The Early Spanish Main (London: Cambridge University Press, 1966), pp. 104-19 and 161-177; Erin Stone, Indian Harvest: the Rise of the Indigenous Slave Trade from Española to the Circum-Caribbean, 1492-1560 (Ph.D. thesis, Vanderbilt University, 2014); and Nicolás del Castillo Mathieu, “Población aborigen y conquista, 1498-1540”, in História Económica y Social del Caribe Colombiano, ed. by Adolfo Meisel Roca (Bogotá: Ediciones Uninorte-ECOE, 1994), pp. 25 and 43.

4 Jane Landers, “The African Landscape of 17th Century Cartagena and its Hinterlands”, in The Black Urban Atlantic in the Age of the Slave Trade (The Early Modern Americas), ed. by Jorge Cañizares-Ezguerra, James Sidbury and Matt D. Childs (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), pp. 147-62.

5 Castillo Mathieu, pp. 43 and 25; Anthony McFarlane, Colombia before Independence: Economy, Society and Politics under Bourbon Rule (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), pp. 17-18; and María del Carmen Borrego Plá, Cartagena de Indias en el Siglo XVI (Seville: Escuela de Estudios Hispano-Americanos, 1983), pp. 58-61 and 423-35.

6 McFarlane, p. 8.

7 Castillo Mathieu, pp. 44-45; and María del Carmen Borrego Plá, “La conformación de una sociedad mestiza en la época de los Austrias, 1540-1700”, in História Económica y Social, ed. by A. Meisel Roca (Bogotá: Ediciones Uninorte-ECOE, 1994), pp. 59-108 (pp. 66-68).

8 António de Almeida Mendes, “The Foundation of the System: A Reassessment of the Slave Trade to the Spanish Americas in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries”, in Extending the Frontiers: Essays on the New Transatlantic Slave Trade Database, ed. by David Eltis and David Richardson (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008), pp. 63-94.

9 After the union of the Spanish and Portuguese crowns in 1580, the Portuguese Company of Cacheu began to export more slaves from Angola and the Kingdom of Kongo. Borrego Plá, Cartagena de Indias, pp. 58-61 and 423-35.

10 David Wheat, Atlantic Africa and the Spanish Caribbean, 1570-1640 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, forthcoming), ch. 3. Wheat also participated in the EAP project in Quibdó, EAP255: Creating a digital archive of Afro-Colombian history and culture: black ecclesiastical, governmental and private records from the Choco, Colombia, http://eap.bl.uk/database/overview_project.a4d?projID=EAP255

11 Linda A. Newson and Susie Minchin, From Capture to Sale: The Portuguese Slave Trade to Spanish South America in the Early Seventeenth Century (Leiden: Brill, 2007); and Borrego Plá, “La conformación”, p. 68.

12 Landers, “The African Landscape of 17th Century Cartagena and its Hinterlands”; Jean-Pierre Tadieu, “Un proyecto utópico de manumission de los cimarrones del ‘Palenque de los montes de Cartagena’ en 1682”, in Afrodescendientes en las américas: trayectorias sociales e identitarias: 150 años de la abolición de la esclavitud en Colombia, ed. by Claudia Mosquera, Mauricio Pardo and Odile Hoffman (Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2002), pp. 169-80.

13 Sauer, Early Spanish Main, pp. 161-77, 268-69 and 288-89.

14 William Frederick Sharp, Slavery on the Spanish Frontier: The Colombian Chocó, 1680-1810 (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1976), pp. 19 and 13.

15 Vicente Restrepo, Estudio sobre las minas de oro y plata de Colombia, 2nd edn. (Bogotá: Banco de la República 1952); Enrique Ortega Ricaurte, Historia documental del Chocó (Bogotá: Editorial Kelly, 1954); Helg, p. 72; and Sergio A. Mosquera, El Mondongo: Etnolingűística en la historia Afrochocoana (Bogotá: Arte Laser Publicidad, 2008).

16 See William F. Sharp, “The Profitability of Slavery in the Colombian Chocó, 1680-1810”, The Hispanic American Historical Review, 55 (1975), 468-95.

17 On the early establishment of mines in the Chocó and the enslaved miners and mazamorreros who worked them, see Mario Diego Romero, Poblamiento y Sociedad en el Pacífico Colombiano siglos XVI al XVIII (Cali: Universidad del Valle, 1995). For an overview of the historiography of this region see Mónica Patricia Hernández Ospina, “Formas de territorialidad Española en la Gobernación del Chocó durante el siglo XVIII”, Historia Crítica, 32 (2006), 13-37.

18 On the artistic traditions of the region, see Martha Luz Machado Caicedo, La escultura sagrada chocó en el contexto de la memoria de la estética de África y su diaspora: ritual y arte (Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2011); and Sharp, pp. 20-21.

19 Orián Jiménez, “El Chocó: Libertad y poblamiento, 1750-1850”, in Afrodescendientes en las américas, pp. 121-41.

20 Royal orders repeated this prohibition many times over the course of the eighteenth century. Sharp, Slavery on the Spanish Frontier, pp. 10, 14 and 15.

21 Ibid., pp. 148-70; and Sergio Mosquera, “Los procesos de manumisión en las provincias del Chocó”, in Afrodescendientes en las américas, pp. 99-120.

22 Carlos Rosero, “Los afrodescendientes y el conflicto armado en Colombia: La insistencia en lo propio como alternativo”, in Afrodescendientes en las américas, pp. 547-59.

23 Some published examples appear in Sergio A. Mosquera, Memorias de los Ultimos Esclavizadores en Citará: Historia Documental (Carátula: Promotora Editorial de Autores Chocoanos, 1996).

24 Sharp, Slavery on the Spanish Frontier.

25 As quoted in Sergio A. Mosquera, Don Melchor de Barona y Betancourt y la esclavización en el Chocó (Quibdó-Chocó: Universidad Tecnológica del Chocó “Diego Luis Córdoba”, 2004), p. 162.

26 Notaria Primera de Quibdo, Libro de Venta de Esclavos 1810-188, Fol. 132r. Notaría Primera de Riohacha Archive, Protocolo 1, Riohacha, 23 March 1831. Notaría Primera de Riohacha Archive, Protocolo 1, Riohacha, 4 May, 1831. Baptism of María Olalla, Book of Baptisms, San Gerónimo de Buenavista, Montería, Córdoba, 20 February 1809.

27 See, for instance, Diana Obregón, “Building National Medicine: Leprosy and Power in Colombia, 1870-1910”, Social History of Medicine, 15 (2002), 89-108; or Pilar Sabater, “Discurso sobre una enfermedad social: La lepra en el virreinato de la Nueva Granada en la transición de los siglos XVIII y XIX”, Dynamis, 19 (1998), 401-28; and Abel F. Martínez Martín, El lazareto de Boyacá: lepra, medicina, iglesia y estado 1869-1916 (Tunja: Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia, 2006).

28 Diana Obregón, “The Anti-leprosy Campaign in Colombia: The Rhetoric of Hygiene and Science, 1920-1940”, História, Ciências, Saúde-Manguinhos, 10 (2003), 179-207.

29 Kenneth R. Andrews, The Spanish Caribbean: Trade and Plunder 1530-1630 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1978), pp. 27-29; Kris E. Lane, Pillaging the Empire: Piracy in the Americas 1500-1750 (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1998), pp. 27, 36-38, 106 and 117; and K. R. Andrews, The Last Voyage of Drake and Hawkins (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1972), p. 95.

30 David Laing Purves, The English Circumnavigators: The Most Remarkable Voyages Round the World by English Sailors (London: William P. Nimmo, 1874), p. 103.

31 Relación, 24 January 1596, Archivo General de Indias, cited in Andrews, The Spanish Caribbean, p. 29.

32 Andrews, The Spanish Caribbean, pp. 49, 84, 118-19, 124-25 and 164-65.

33 Lane, pp. 27, 36-38, 106 and 117; and Andrews, The Last Voyage of Drake, p. 95.

34 Miguel Acosta Saignes, Vida de los Esclavos Negros en Venezuela (Caracas, Hespérides 1967), pp. 255-58.

35 Lance R. Grahn, “An Irresoluble Dilemma: Smuggling in New Granada, 1713-1763”, in Reform and Insurrection in Bourbon New Granada and Peru, ed. by John R. Fisher, Allan J. Kuethe and Anthony McFarlane (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1990), pp. 123-46. Also see Ernesto Bassi Arevalo, Between Imperial Projects and National Dreams: Communication Networks, Geopolitical Imagination, and the Role of New Granada in the Configuration of a Greater Caribbean Space, 1780s-1810s (Ph.D. thesis, University of California, Irvine, 2012).

36 Lance Grahn, The Political Economy of Smuggling: Regional Informal Economies in Early Bourbon New Granada (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1997), ch. 3.

37 Eduardo Barrera Monroy, “La Rebelión Guajira de 1769: algunas constants de la Cultura Wayuu y razones de su pervivencia”, Revista Credencial Historia (June, 1990), http://www.banrepcultural.org/blaavirtual/revistas/credencial/junio1990/junio2.htm

38 Grahn, The Political Economy of Smuggling, ch. 3; Helg, Liberty and Equality in Caribbean Colombia, pp. 27-31 and 43-48; and Eduardo Barrera Monroy, Mestizaje, comercio y resistencia: La Guajira durante la segunda mitad del siglo XVIII (Bogotá: Instituto Colombiano de Antropolgía e Historia, 2000), p. 35.

39 José Polo Acuña, Etnicidad, conflicto social y cultura fronteriza en la Guajira, 1700-1850 (Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes, 2005). The Wayúu also traded with British and Dutch merchants for gunpowder, knives, slaves, textiles and foodstuffs. Monroy, Mestizaje, comercio y resistencia, p. 98.

40 Petra Josefina Moreno, Guajiro-Cocinas: Hombres de historia 1500-1900 (Ph.D. thesis, Complutense University, Madrid, 1984), p. 188.

41 Ibid.

43 José Polo Acuña, “Territorios indígenas y estatales en la península de la Guajira (1830-1850)”, in Historia social del Caribe Colombiano: Territorios, indígenas, trabajdores, cultura, memoria e historia, ed. by José Polo Acuña and Sergio Paolo Solano (Cartagena: La Carreta Editores, 2011), pp. 45-71.

44 Notaría Primera de Riohacha Archive, Protocolo 1, Riohacha, 23 March 1831.

45 Ibid.

46 Notaría Primera de Riohacha Archive, Protocolo 1, Riohacha, 4 May, 1831.

47 José Polo Acuña and Ruth Gutiérrez Meza, “Territorios, gentes y culturas libres en el Caribe continental Neograndino 1700-1850: una síntesis”, in Historia social del Caribe Colombiano, pp. 13-44.

48 EAP640: Digitising the documentary patrimony of Colombia’s Caribbean coast: the ecclesiastical documents of the Department of Córdoba, http://eap.bl.uk/database/overview_project.a4d?projID=EAP640

49 See http://www.cordoba.gov.co/cordobavivedigital/cordoba_monteria.html. Also see Pilar Moreno de Ángel, Antonio de la Torre y Miranda Viajero y Poblador (Bogotá: Planeta Colombiana Editorial, 1993).

50 Jane Landers, “African ‘Nations’ as Diasporic Institution-Building in the Iberian Atlantic”, in Dimensions of African and Other Diasporas, ed. by Franklin W. Knight and Ruth Iyob (Kingston: University of the West Indies Press, 2014), pp. 105-24.

51 Baptism of María Olalla, Book of Baptisms, San Gerónimo de Buenavista, Montería, Córdoba, 20 February 1809.

52 For an overview of this period, see Marshall Eakin, Brazil: The Once and Future Country (New York: St Martin’s Griffin, 1997), pp. 7-66. On African contributions to Brazil see Linda M. Heywood and John K. Thornton, Central Africans, Atlantic Creoles, and the Foundation of the Americas, 1585-1660 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), pp. 49-108.

53 For an annotated bibliography of suggested readings on this region, see Courtney J. Campbell, “History of the Brazilian Northeast”, in Oxford Bibliographies in Latin America, ed. by Ben Vinson (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

54 J. Costa Porto, O pastoreio na formação do Nordeste (Rio de Janeiro: Ministério da Educação e Cultura, Serviço de Documentação, 1959).

55 José Américo de Almeida, A Paraíba e seus problemas, 3rd edn. (João Pessoa: Estado da Paraíba, Secretaria da Educação e Cultura, Diretoria Geral da Cultura, 1980 [1923]), p. 54.

56 José Octávio de Arruda Mello, História da Paraíba, 11th edn. (João Pessoa: A União, 2008), pp. 25-26 and p. 263.

57 Ibid., p. 263. Before acquiring its modern name the town was known as Felipéia de Nossa Senhora das Neves, Frederica, and Paraíba.

58 Ibid., 265. These indigenous groups were later defeated in bloody massacres by bandeirantes (a type of scouting explorer). José Leal, Vale da Travessia, 2nd edn. (João Pessoa: Editora e Gráfica Santa Fé Ltda, 1993), p. 17.

59 The town was run by the Coronel and cattleman José da Costa Ramos (formerly Costa Romeu). Leal, p. 25.

60 Ibid., p. 55; Padre João Jorge Rietveld, O verde Juazeiro: história da paróquia de São José de Juazeirinho (João Pessoa: Imprell, 2009), pp. 96-98.

61 Mello, p. 266.

62 Campina Grande superseded it in 1769. Rietveld, p. 98.

63 Ibid., pp. 96-99.

64 EAP627: Digitising endangered seventeenth to nineteenth century secular and ecclesiastical sources in São João do Cariri e João Pessoa, Paraíba, Brazil, http://eap.bl.uk/database/overview_project.a4d?projID=EAP627

65 Carmen Margarida Oliveira Alveal, Converting Land into Property in the Portuguese Atlantic World, 16th-18th Century (Ph.D. thesis, Johns Hopkins University, 2007).

66 Ibid., p. 7.

67 Ibid., p. 4.

68 Citing EAP project documents, Solange Pereira da Rocha demonstrates that using these lesser studied sources, “it is possible to elaborate new understandings of the multiplicity of experiences of men and women that lived the experience of captivity, their perceptions of their condition as slaves, and the ways in which they reconstituted family ties and established links with people from other social groups.” Solange Pereira da Rocha, Gente negra na Paraíba oitocentista: população, família e parentesco espiritual (São Paulo: Editora UNESP, 2009), p. 66.

69 For comparison, on seventeenth-century church records from Rio de Janeiro see Mariza de Carvalho Soares, People of Faith: Slavery and African Catholics in Eighteenth-Century Rio de Janeiro (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2011).

70 Maria da Vitória Barbosa Lima, Liberdade interditada, liberdade reavida: escravos e libertos na Paraíba escravista (século XIX) (Brasília: Fundação Cultural Palmares, 2013). This book won the 2012 Concurso Nacional de Pesquisa sobre Cultura Afro-Brasileira, a national award for research on Afro-Brazilian culture given by the Fundação Cultural Palmares, discussed in more detail below. This recognition demonstrates that the importance of histories based on these endangered sources has gained national attention as Brazilian scholars emphasise the importance of studying the effects of slavery on its multi-ethnic population.

71 Rocha, p. 27.

72 Ibid., p. 294.

73 Ibid.

74 Solange Mouzinho, Parentescos e sociabilidades: experiências de vida dos escravizados no sertão paraibano de São João do Cariri, 1752-1816 (Master’s dissertation, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, 2014). Mouzinho used the documents to create a database of the population of São João do Cariri.

75 “Programas e ações”, Fundação Cultural Palmares, accessed July 29, 2014, http://www.palmares.gov.br/?page_id=20501

76 “Lei No. 7.668, de 22 de agosto de 1988”, accessed on July 29, 2014, available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/L7668.htm; “Programas e ações”.

77 On the Tabajara movement, see: Ismael Xavier de Araújo, Viviane dos Santos Sousa, Roméria Santana da Silva Souza, Jeremias Jerônimo Leite, Tânia Maria de Andrade, and Rodrigo Lira Albuquerque dos Santos, “Processo de emergência étnica: povo indígena Tabajara da Paraíba”, in Congresso Norte Nordeste de Pesquisa e Inovação (CONNEPI) (2012). Available online at http://propi.ifto.edu.br/ocs/index.php/connepi/vii/paper/view/2110/1626