16. Completion of the Land Register: The Scottish Approach

© John King, CC BY 4.0 http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0056.16

A. Introduction

Scotland can lay claim to the world’s oldest, still running, public property register. Dating from 1617,1 the Register of Sasines has witnessed the industrial revolution, the extension of the franchise and the spread of property ownership. It is a real success story; the authors of the Act got it right first time, and deed registration became a concept which was subsequently adopted, in various guises, across the world.

Scotland also has one of the most recent land registration systems by international standards. The Land Register was a late introduction to Scotland: the Land Registration (Scotland) Act 1979 (“the 1979 Act”) commenced in 1981, albeit only for the operational county of Renfrew.2 It took a further 22 years before the Land Register was extended to all registration counties in Scotland.3 The 1979 Act has enabled the registration of over 1.5 million properties in Scotland but it has not been without challenge or criticism.

One commentator scathingly described the Act as “having all the intellectual sharpness of mashed potato.”4 Consequently, within 12 years of the 1979 Act operating throughout Scotland (though doubts persisted as to whether or not it also extended to Scotland’s seabed as well as its land), it has been reformed and replaced, subject to transitional provisions, by the Land Registration etc. (Scotland) Act 2012 (“the 2012 Act”).

One of the key policy aims that lay behind the 2012 Act was enabling the completion of the Land Register. No timescale for completion was provided in the Act, though the Economy, Energy and Tourism Committee recommended the “setting of a target and interim targets, even if aspirational, on the face of the Bill.”5 This was not an approach that found favour with the Minister responsible for the Bill.6 However, other factors have subsequently influenced Scottish Ministers to set a timescale for completion.

In May 2014 the final report of the Land Reform Review Group was presented to Scottish Ministers.7 Established by the Scottish Government in May 2012, the ground had a remit to consider a broad spectrum of land reform issues. One of the areas it considered was coverage of the Land Register and it recommended that:8

…the Scottish Government should be doing more to increase the rate of registrations to completion of the Register, a planned programme to register public lands and additional triggers to induce the first registration of other lands.

Following consideration of that report, Paul Wheelhouse MSP, the Minister for Environment and Climate Change, made the following announcement:9

Along with my colleague Enterprise Minister Fergus Ewing, I have asked Registers of Scotland to prepare to complete land registration within 10 years, with all public land registered within five years.

So, some 33 years since land registration was introduced to Scotland, we now have a target for completing the Land Register by the end of 2024. This essay seeks to offer a definition of completion, considers the contrasting approaches to completion under both the 1979 Act and the 2012 Act, compares these with the English and Welsh experience and asks whether or not the legal tools exist to enable completion within the ten year target.

B. The Case for Completion

Setting aside discussion over the timescale for completion, the suggestion that a completed Land Register is desirable is likely to be met with general approval. That was certainly the emphasis of the evidence provided to the Economy, Energy and Tourism committee. They reported that there “was overwhelming support from witnesses for a Land Register that is reliable, secure and accessible and for the eventual closure of the Register of Sasines.”10

The arguments in favour of a completed Land Register have been well rehearsed in recent years. The Scottish Law Commission (SLC) succinctly stated that “the short answer is that the Land Register is better than the Register of Sasines”11 and then detailed why this was so. Similarly the Consultation Document on completion of the Land Register12 (“the completion consultation document”) lists the benefits. Indeed, glancing south of the Border, the website of Her Majesty’s Land Registry (HMLR)13 also lists near identical reasons why registration in the Land Register and the aim of a completed register is so desirable. So, what are the reasons?

The completion consultation document sets out four compelling reasons: transparency, cost, efficiency and national asset. Transparency is self-evident. A map-based register of title to land makes for simple interrogation and so provides ease of access to information on who owns Scotland. That, in turn, reduces the costs associated with examination of titles: it takes less time and effort to examine an entry on the Land Register than it does if a property is held under title deeds on the Sasine Register. Added to this, the SLC has highlighted14 the growing issue that some younger conveyancers may not have the requisite knowledge of the workings of Sasine titles.

For a country of Scotland’s size, it is inefficient to have two property registers. The Land Register makes it easier to transact with property, which in turn, facilitates the property market and makes Scotland attractive to foreign investment. At a macro level, transparency, ease of access and the guarantee of title adds value to the economy. That fits with the final reason provided by the completion consultation document for a completed Land Register being a national asset. Knowing who owns Scotland and having access to that information supports those public and private bodies and companies whose administrative and business activities require use of accurate title information. The Land Reform Review Group also commented15 on the difficulties of having an informed discussion on land reform and land use in the absence of comprehensive information on land ownership in Scotland.

Though there is general consensus that a completed Land Register would be an unqualified positive for Scotland, the fact the journey to that end is set against the backdrop of a near 400-year old deeds register is to our advantage. It is more helpful to have two property registers than to simply have one incomplete Land Register. If a property is not on the Land Register, there is a very high chance it will rest on deeds in the Sasine Register. In short, except for an indeterminate but expected low volume of properties not on either register, it is generally possible, albeit at times with difficulty, to identify the title deed or potential title deed that relates to an area of land.

Contrast that with England and Wales. There is one national property register, Her Majesty’s Land Register (“HMLR”), but it is not yet complete. Approximately 15% of the land mass of England and Wales is not on HMLR.16 Tracking information on non-registered land is anything but straightforward; there may be some information in local registers or there may simply be no information available. So, as much as there are solid reasons for completing Scotland’s Land Register, we should recognise that other jurisdictions with incomplete Land Registers may look at us with envy over the continuing safety net that an old deeds register can provide.

C. What Constitutes Completion?

In being asked to complete the register within ten years, it is clearly essential that the Keeper sets out what this entails. This allows progress to be monitored and expectations to be managed. There are various interpretations that can be suggested.

First, completing the Land Register could be viewed as achieved when the Sasine Register is closed to new deeds of any type. RoS estimates that there are some 1.1 million property titles17 remaining in the Sasine Register. The rate at which titles transfer from the Sasine Register to the Land Register has averaged at an annual rate of 40,270 first registrations over the last ten years.18 On the designated commencement day for the 2012 Act, 8 December 2014 (“the designated day”), the Sasine Register closed to all dispositions. Over the last ten years, an average of 22,850 dispositions have been recorded each year in the Sasine Register.19

The 2012 Act contains powers under section 48(2) and (3) which, if used in full, could have the effect of closing the Sasine Register to all deeds. The mechanics and practicalities of this are discussed later. Of course that would not make the Sasine Register redundant; it would simply up the pace with which properties transfer on to the Land Register. In 2013-14 some 35,000 deeds were recorded in the Sasine Register, affecting an estimated 25,000 different properties and interests in land.20 Notwithstanding the increased pace with which properties would move on to the Land Register, the fact remains that the two property registers would continue to co-exist for potentially many decades. So, closure of the Sasine Register to new deeds would not equate with a completed Land Register.

Secondly, taking the first interpretation a step further, completion could be viewed as achieved when all properties and interests held on title deeds recorded in the Sasine Register are brought on to the Land Register. Unquestionably that would be a significant achievement, as it would enable the Sasine Register to take a well-earned retirement amongst Scotland’s national archives. However in terms of Scotland’s new Cadastral Map there would still be gaps. In land registration parlance, there would still be tracts of land without a red edge delineating ownership boundaries. There would still be unregistered land and so the Land Register would not be complete.

Thirdly, the most comprehensive interpretation of completion combines interpretations (i) and (ii) and seeks to add to that the remaining unregistered land. That would provide a complete cadastral map for Scotland reflecting ownership of land, identifying long leases over land and also detailing ownership of separate tenements in that land. It is currently impossible to ascertain the full extent of land that does not fall within either the Land Register or the Sasine Register. Within RoS we have anecdotal knowledge of some such land, for example the original land holdings of St Andrews University and some City of Edinburgh Council land holdings in Edinburgh’s Old Town. The full extent of unregistered land will only become apparent when all properties and interests held on title deeds recorded in the Sasine Register are in turn registered in the Land Register. Much of this land will have seen ownership transferred via charters and deeds that were executed prior to the establishment of the Sasine Register. It is also possible that some of this land will have been gifted as common good land, may be undivided commonty or may, if never alienated, remain with the Crown.

It is also inevitable that some of this notionally unregistered land will ultimately trace back to titles on the Sasine Register that were considered to have previously transferred to the Land Register. This is not surprising; aside from the difficulties in interpreting often vague Sasine deed descriptions, the prescribed application form21 for a first registration under the 1979 Act invites the applicant to advise if they will accept the Land Register boundaries reflecting the occupied extent where that is less than the legal extent as set out in the deeds. Whilst this provision can often resolve what would otherwise be a boundary issue with a neighbouring property that also includes the same area within its title deeds, there are instances where slithers of land excluded from Land Register titles will not fall into any other titles.

An applicant may choose not to include land outwith their physical boundaries (fence, hedge etc.) within the Land Register title. This may satisfy the expectations of a purchaser in a first registration transaction but it does mean that the seller may remain, unwittingly in most cases, the owner of the excluded interest. It is not uncommon for such slithers to be considered abandoned and unused by anyone or to be possessed as part of a neighbouring property extent without being contained within the legal title for that property. Identifying and resolving these unintended consequences of the operation of land registration under the 1979 Act will be challenging, though it may be that the new 2012 Act provisions for prescriptive claimants22 will provide a vehicle for bringing some of these strips of land on to the Land Register.

The completion consultation document sets the bar high. It favours the comprehensive interpretation. It is noted that even if this point is achieved, the cadastral map will not remain unchanged; it is a living map and registered extents will change to reflect sub-divisions and amalgamations of property.

D. Completion: Achievable or Unattainable?

All three of the above possible interpretations talk in terms of absolutes when considering what could constitute completion. The question that arises is whether or not it is practical to talk in terms of absolutes or is that an aspiration that is simply too high. The answer depends in large part on whether or not legal powers exist to enable completion or not. If the legal powers do exist, and there is a political commitment to maximising the use and effect of those powers, then absolute completion is not a forlorn aspiration. Equally, starting from a position whereby legal powers on their own would not be sufficient to achieve completion would suggest that any target ought to be more modest.

(1) England and Wales: the comprehensive register

There has long been an unsubstantiated anecdotal view amongst RoS registration staff that HMLR must be near completion. That view was informed by two factors (three if you include the absence of any research): first, the awareness that the Land Register stems from 1862,23 and secondly the application of a little relative mathematics. The argument runs that if the Land Register has been in existence for over 150 years, it must be near complete if our own Land Register has 58%24 of properties on it after a mere 33 years. Set in the context of a pub quiz for land registrars, it is doubtful if many would correctly answer 54.5% if asked to estimate the end March 200625 figure for land mass coverage of England and Wales. Clearly, our view has been wrong.

It has taken a considerable period of time for their Land Register to gain traction. Although the Land Registry Act 1862 established a land register for England and Wales, it did not back its introduction with any element of direct or indirect compulsion. Consequently, by 1868, only 507 titles were registered. The need for compulsion was recognised, albeit in a less than robust fashion by the Land Transfer Act of 1897; local counties could still veto the introduction of compulsory registration.26 As a result, adoption was slow.27

Compulsion was to the fore in the Land Registration Act 1925, as provision was made for the Sovereign, by Order in Council, to make registration following a sale compulsory in any area.28 It is reported that forecasts at the time suggested that compulsory registration would be extended to all areas by 1955. This was not to be and the remaining 14 areas were not brought within the ambit of the Land Registry until 1 December 1990.29 At this point there were some 12.7 million registered titles whereas now there are some 23.8 million.30 Before the introduction of computer mapping the Land Registry was not able to work out the percentage of land registered. So, the fully-operational English and Welsh Land Register is only some 13 years ahead of our own wholly-operational Land Register.

HMLR do now have a considerably more comprehensive range of legal triggers for registration, referred to under section 4 of the Land Registration Act 2002 (“the 2002 Act”) as the “requirement of registration.” The approach under section 4 is to specify a comprehensive list of events, on the occurrence of which the title must be registered. In contrast to Scotland, the 2002 Act specifies that registration must occur within a specified time limit; namely two months from the date on which the trigger event occurred.31 The penalty for non-compliance is severe: the transfer or grant or creation becomes void “as regards the transfer, grant or creation of a legal estate.”32 So trigger events will result in registration.

As in Scotland, the triggers that generate large volumes of registration applications are the transfer of a freehold estate or a lease for valuable or other consideration or by way of gift. A lengthy list of other triggers is provided for, some of which have proved to be significant in generating registration and countering circumstances where registration may otherwise be avoided. As an example of the former, compulsory registration applies on the creation by the owner of an estate in unregistered land of a protected first legal mortgage33 unless it is a mortgage of a lease with no more than seven years to run. (A protected first legal mortgage is defined as one that, on creation, ranks in priority ahead of other mortgages affecting the mortgaged estate).

The latter is illustrated by the requirement for registration on what is termed an assent, including a vesting assent.34 So the transfer by a trustee or executor to a beneficiary would necessitate registration; this is aimed at countering the situation that occurs in Scotland whereby properties can pass through generations of the same family without any impact on the property registers. Because of the way in which HMLR captures management information it has not been possible to obtain accurate figures to illustrate the impact of these triggers. Discussion with senior HMLR staff suggest both have had a major affect in triggering registration.35

There are two other legal vehicles open to HMLR to further completion. The Lord Chancellor may “add to the events on the occurrence of which the requirement of registration applies such relevant event as he may specify in the order.”36 To date this power has been used once37 to extend compulsory registration to partitions and most deeds of appointment of new trustees. The only other legal tool available to HMLR is to promote voluntary registration and this has been used with effect.

In 2002, HMLR adopted as part of its corporate strategy the achievement of a “comprehensive register.”38 It was explained that a comprehensive land register:39

…will include the majority of freehold land forming the surface of England and Wales. The register need not necessarily include leasehold land although we would expect to register those leasehold interests where the leasehold interest is a valuable interest. The register need not include the seabed and the foreshore. Land where the owner cannot be identified and roads, rivers, and other physical features where ownership is not determined by registration. Also, rent charges and certain rights that can be registered (such as the right to fish or hold a market) need not be included in the comprehensive land register. However, we would still encourage the registration of all these Interests.

The choice of the term “comprehensive” reflected the challenge of completion and the acknowledgement that although the legal framework for determining when registration was compulsory was extensive, it would not by itself lead to all properties being registered and to achieve a significant increase in the properties and land mass on the Land Register other steps would be necessary. Those steps subsequently centred around a marketing campaign to promote and encourage voluntary registration. Incentives in the form of a lesser registration fee (25% reduction) and partnership working whereby Land Registry staff were embedded in organisations to help prepare applications were offered. That campaign ran until 2012, when the decision was taken not to actively market voluntary registrations. The workforce in HMLR had been reduced to match registration intakes and an assessment of the costs against the benefits of registering the remaining land mass was considered too high. The decision was taken to allow the trigger provisions to bring on the remainder of unregistered properties, though voluntary registration would still be available.

The voluntary registration campaign was a success. By end March 2012, some 23.3 million registered titles existed, accounting for some 79% of the English and Welsh land mass.40 Notwithstanding that achieving the comprehensive register is no longer part of their corporate strategy, the land mass coverage has continued to grow; by end March 2014, some 84.3% had been registered.41 HMLR’s experience was positive and demonstrates that Scotland is perhaps sitting on an as yet untapped demand for voluntary registration. The volumes of voluntary and compulsory first registrations since 2007 are set out in the table below.42

|

Year |

Voluntary FR |

Comp FR |

Percent Voluntary |

|

2007-08 |

94,879 |

235,492 |

28.7% |

|

2008-09 |

205,201 |

166,767 |

55.2% |

|

2009-10 |

125,307 |

148,333 |

45.8% |

|

2010-11 |

91,037 |

144,065 |

40.4% |

|

2011-12 |

58,945 |

127,328 |

31.6% |

|

2012-13 |

51,001 |

126,108 |

28.8% |

|

2013-14 |

39,002 |

129,626 |

23.1% |

|

Total |

665,372 |

1,077,719 |

38.2% |

(2) Scotland: aiming for the complete Land Register

The focus of the 1979 Act was not on a completed Land Register. More immediate concerns were to the fore, such as introducing land registration to a jurisdiction where the Register of Sasines, and all the conveyancing practices associated with it, had been largely unchanged for some 360 years. The focus was rightly on introduction and not completion of the Land Register, a sentiment strongly to the fore in the earlier Reid and Henry Committee Reports.43 Notwithstanding that those reports acknowledged the benefits of land registration they were both heavily influenced by the possible inconvenience that introduction could bring to those transacting with property and to the Keeper:44

To prevent dislocation of the work of the Keeper and his staff we suggest that the only practicable scheme is to begin introducing registration of title in one Division and then extend it to other Divisions from time to time as circumstances permit. We regard it as impracticable to require the titles of all properties in a Division to be registered within a limited time. We think that the best method would be to make registration of title compulsory on the first transfer for onerous consideration of any property within a designated Division, and to permit registration of title of any property within such Division at any other time if the owner applies for it.

In favour of such an approach, the committee cited two reasons:45

We do not think it would be reasonable to require an owner to incur the expense of registration except on such a transfer, when the title of the property will have to be examined in any event, and therefore the additional expense involved in registration of title will be small. Secondly, it would unduly increase the work of the staff in the Register House to require compulsory registration of title on other occasions.

The Henry Committee reached a similar conclusion.46 History has shown that their concerns were not overstated: extending land registration to all of Scotland, provisionally timetabled for nine years, ultimately took some 22. This elongated timescale, and the associated build-up of first registration casework that accompanied it, has done much to influence the scepticism with which a number of practitioners view the target of completion within ten years.

The 1979 Act approach generally aligns with what were then the main routes on to the Land Register in England and Wales, namely a transfer for valuable consideration, grant of lease, or through the Keeper accepting a request for voluntary registration. One notable difference with the approach to registration in England and Wales is that the 1979 Act did not make any provision for a time period within which registration should take place after the occurrence of a particular trigger event. Consequently, registration is prima facie optional; section 2(1) provides that an unregistered interest in land “shall be registrable.”

There is of course a sting in the tail should registration not be sought, for in the absence of registration no real right will be obtained. As the commentary to the Registration of Title Practice Book narrates, “the compulsitor is that there shall be no real right without registration.”47 There are other factors driving the time frame in which registration ought to occur: limited company standard securities over registered land require registration in the Land Register before they can be registered in the Register of Charges.48 The protection afforded by letters of obligation and the new advance notices49 in effect set a time-frame within which registration will, in the main, occur.

Requests for voluntary registration were permissible under the 1979 Act50 and the Keeper was given the discretion on whether or not to accept such a request. The criterion by which the Keeper should consider such a request is that of expediency. In practice, for the period from 1981 through to the mid-2000s that criterion was tightly applied and voluntary registrations were rare. The emphasis was very much on the impact such a request would have on the Keeper and not on the needs of the applicant. As the Practice Book51 explains: “the Keeper does not normally accept voluntary registrations unless there are obvious benefits to him.” The main source of voluntary registrations related to transfers of a half pro indiviso share in a Sasine title. In those circumstances the Keeper would encourage voluntary registration of the remaining half share. The only other circumstance in which the Keeper would regularly accept a request was in connection with a builder or developer’s title for which individual plots were about to be sold.

The reason for the reluctance to accept requests was simple: RoS was not coping with the volume of trigger-based registrations and did not want to add to the time it would take to complete those registrations. The Keeper’s position began to change in the mid-2000s. There was growing acceptance that the balance of convenience was tipped too heavily in favour of the Keeper. A more relaxed and encouraging approach developed and culminated in a joint article52 by the current Keeper and Fergus Ewing MSP, the Minister for Energy Economy and Tourism, heralding an effective open door policy. The exceptions to that are limited and relate in the main to ongoing litigation affecting the property to which the request relates. In the last four years, RoS estimate that the volume of voluntary registrations has been in the region of 2000 applications per annum: about 4% of the overall volume of first registrations. That of course compares poorly with the volume of voluntary applications received by HMLR. The open door policy has been supported by some targeted marketing of voluntary registration, mostly around commercial and residential developers and large private estates.

The 1979 Act was not wholly oblivious to the future. The Act states that Ministers may provide:53

…that interests in land of a kind or kinds specified in the order… shall be registered; and the provisions of this Act shall apply for the purposes of such registration with such modifications, which may include provision as to the expenses of such registration, as may be specified in the order.

The provision has not been used. Commentary in the Practice Book describes this provision somewhat dramatically as “machinery for the elimination of the Register of Sasines.”54 In a nod to the current discussion on funding completion, the then Government did indicate the costs of closing the Sasine Register would, other than in trigger situations, be borne by the public purse.55

The problem with the 1979 Act approach is that it allowed for no middle ground. Triggers for registration were set in the legislation and no provision was made for the addition of further triggers. Instead, section 2(5) allowed Scottish Ministers to provide that at a certain point in time those remaining unregistered properties would be registered by the Keeper. Finding an explanation as to how this provision would work in practice is challenging. I am unaware of any detailed discussions within RoS as to its use and there were no plans to suggest to Ministers that it be used. Mindful of the costs associated with section 2(5), the Scottish Executive did suggest in 1999 that consideration of its use would be appropriate when most properties in a registration county had been registered through sale.56 It indicated that would be the case after 10 to 15 years of land registration. That was an overly optimistic assessment of the pace of completion. In the event, the gap from a limited set of triggers to committing to full registration was considered a leap too far.

Without question, the 1979 Act has advanced completion. In just under 34 years, some 1.5 million property titles have been registered, estimated at roughly 58% of all properties within Scotland.57 This is a not inconsiderable figure given that it was April 2003 before all of Scotland was operational under the Act. For the registration counties that were first on to the Land Register, the title coverage is way in excess of the Scottish average; Renfrew stands at 76% and Dumbarton at 74%.58 More recent converts to the Land Register, particularly those predominantly rural counties, have much less coverage. Both Ross & Cromarty and Caithness have fewest titles registered: an estimated 36%.59 This is not surprising. Properties in the more economically active and densely populated urban areas change hands more frequently than properties in rural areas.

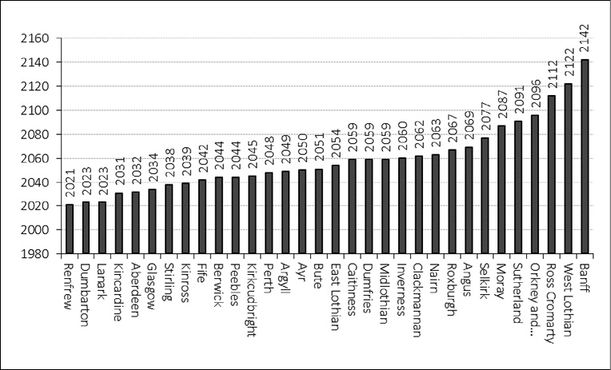

Under the 1979 Act triggers for registration, completion would simply not be achieved. Some properties never change hands and some transfer for no consideration. RoS forecast that registration counties would peak at around 90% title coverage based on the 1979 Act triggers.60 Achieving 90% coverage would vary from registration county to registration county:

Projected completion rate with no changes

Between now and 2030. RoS forecast that only five registration counties would potentially exceed 90% title coverage. The majority of counties would take to 2060 to see 90% title coverage and for some of the more rural counties, such as Ross and Cromarty and Banff we could be waiting for up to 100 years and more. In short, completion would simply not happen and therein lies the driver for the changes introduced by the 2012 Act.

(3) The 2012 Act

The 2012 Act takes a markedly different approach to the bringing of properties on to the Land Register as compared with the 1979 Act. Not only does the Act provide the technical tools to further the goal of completion but underlying those technical provisions is a strategy to direct their use. The 2012 Act approach to registration moves away from the approach under the 1979 Act of listing transaction types the occurrence of which will require registration. Instead it lists those deeds to which the Register of Sasines is closed; the effect being that they must be registered in the Land Register.61

In an Act concerned with completion one might suspect that the list would be extensive. On the contrary it is brief. On the designated day the specified deeds to which the Sasine Register is closed number three; disposition, lease and assignation of lease. The door to the Sasine Register is left slightly ajar for those dispositions where recording in the Sasine Register is necessary for purposes of dual registration under the Title Conditions (Scotland) Act 2003.62 Registration remains voluntary but as under the 1979 Act a real right cannot be acquired otherwise.63

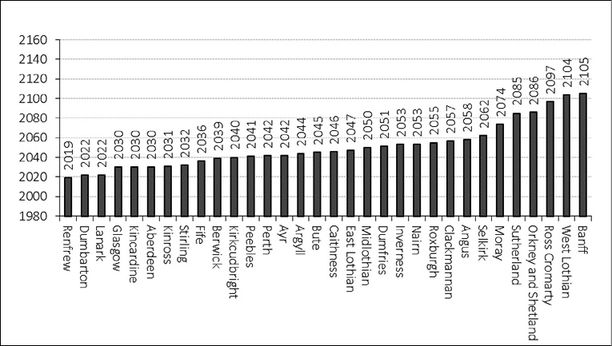

The 2012 Act approach to registration makes no distinction between a disposition for value and a disposition for no consideration or value. Notwithstanding the additional 8500-10000 new registrations that RoS forecast will be generated by this approach, the impact on completion is marginal. The following table suggests that registration counties will achieve 90% completion earlier than would otherwise be the case but not significantly earlier.64 Achieving 90% completion rates across Scotland would still take until the 22nd century. As under the 1979 Act, and indeed as is the case in England and Wales, some properties and interests will simply not change hands and so this new registration requirement will not deliver completion.

Projected impact of the 2012 Act

There is one further legislative change that the 2012 Act introduced that will aid completion, both in a direct and an indirect way. That change concerns leases. Leases are by their nature temporary. Under the 1979 Act, they enter the Land Register and then, at the end of their life, the associated entry on the Land Register is removed. The 2012 Act sets different legal requirements around leases and those requirements aid completion. It will no longer be possible to register a lease, a sub-lease or an assignation of an unregistered lease unless the plot of land to which the deed relates is also registered. Where the plot of land is unregistered, an application to register such a deed will induce registration of the owner’s plot; termed “automatic plot registration.”65 On its own this will not have a major impact on completion – over the last ten years RoS has registered an annual average of 945 leases.66 Where it will have more impact is on making landlords consider whether or not it would be more practical to voluntarily register all their land rather than simply the area affected by the lease. As a driver of voluntary registration, the impact of automatic plot registration could be significant, for it is only through voluntary registration that a landlord can retain control of the registration process for his or her land.

The 2012 Act brings about no immediate changes as far as applications for voluntary registration are concerned. The Keeper’s discretion to accept or refuse such an application remains as does the test of expediency. So too does the Keeper’s open door policy to voluntary applications. However, the Keeper recognises that more will be required than simply having an open door to voluntary applications if the ten year completion target is to be met. The volume of voluntary applications will have to increase substantially and the challenge for realising that will rest with the Keeper. Voluntary registration will have to be actively marketed and the Keeper will need to employ a range of different arguments to different sectors in aid of this. For some, the existence of the automatic plot registration provisions may offer an inducement to register; for others having certainty and assurance as to legal boundaries may be important: and for the wider public sector the catalyst to register will be the target set by Scottish Ministers to register such land within five years. It is the Keeper’s understanding that the vehicle for this is voluntary registration.

Set against the benefits of voluntary registration will be cost. Costs will be a factor for many who are open to considering voluntary registration; the Keeper acknowledges this and the completion consultation document sought views on an appropriate level of financial incentivisation. Registration fees are only part of the overall costs; there will, in most cases, be legal costs. However, as the successful HMLR experience has demonstrated, costs are not an absolute barrier. The outcome of the consultation is not yet known.

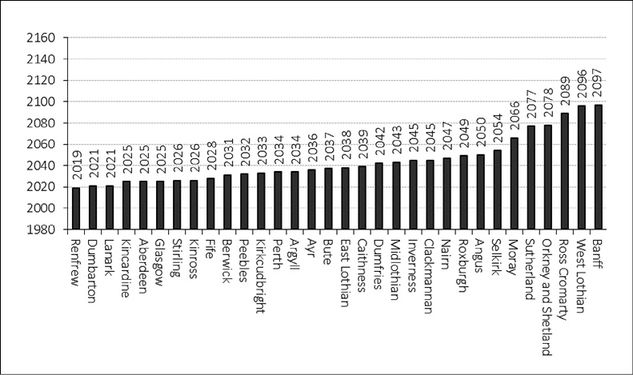

The need to promote voluntary registration means that the legal discretion the Keeper has to refuse a request for voluntary registration is likely to prove theoretical rather than real. The 2012 Act gives Scottish Ministers the power67 to prescribe an end to that discretion and it is thus perhaps no surprise that the Keeper favours its removal.68 There are other strong legal reasons for ending that discretion and those reasons derive from the strategy for completion that the Act gives effect to. The completion toolkit set out in section 48 includes the power for Scottish Ministers, after due consultation with the Keeper and other appropriate persons, to close the Sasine Register to standard securities on a county-by-county or all-Scotland basis. Closure of the Sasine Register in this way will create additional “triggers” that will increase the number of properties having their first registration onto the Land Register. Before this power can be enabled, section 48(7) requires that the Keeper’s discretion to refuse an application for voluntary registration be removed.

The reason for this is perhaps best explained by an example. If the Sasine Register is closed to a standard security, the creditor’s rights under the security can only be made real through registration of the security in the Land Register. To enable registration of the security, there must be a Land Register entry for the property. Thus, the property to which the security relates must be registered in the Land Register either before or at the same time as the security. As there is no statutory trigger for this the proprietor must apply for voluntary first registration in the Land Register. This power is helpful. Based on 2013-14 Land Register intake figures, some 6000 standard securities fell to be recorded in the Sasine Register. The table below shows the projected effect the addition of this provision to the completion armoury would have.69

Projection completion rate inclusive of 2016 standard security changes

The practicality of closing the Sasine Register to standard securities and other deed types has to be considered, and was one of the areas of focus in the completion consultation document. Certain standard securities are already a trigger for registration in England and Wales. That suggests that the market can accommodate the additional work associated with the registration of the property. In the commercial arena, the Keeper has noted that there is an increasing number of requests for voluntary registration arising from the unwillingness of certain lenders to make high end loans in the absence of a Land Register title. In any event, the fact that standard securities are dealt with specifically on the face of the 2012 Act reflects the Scottish Parliament’s view that at some point consideration should be given to closing the Sasine Register to them; the issue is one of timing as opposed to principle.

Closing the Sasine Register to other deed types is more problematic and this is reflected in the completion consultation document. Many of the deeds recorded in the Sasine Register are drawn up and granted by a body other than the proprietor; the most common being discharges, improvement grants, and charging orders and the incentive to apply for voluntary registration does not exist in the same way as with a standard security. Although it is possible for automatic plot registration to be used in such cases to do so would raise a number of practical difficulties for the parties and the Keeper which do not exist for leases and assignations of leases.

To rely on voluntary registration in the same way as is envisaged should the Sasine Register be closed to standard securities is more complicated and less practical. It could also lead to less transparency; if the debtor had to voluntarily register his or her property before being able to register a discharge it may be that such deeds would simply not be registered. Registration would only be necessary at the next transfer of the property or if a fresh standard security was required. Care would also need to be exercised to ensure such a provision would not cut across other policy initiatives or the ability of, for instance, local authorities who may wish to register a charge over a property. Consequently closing the Sasine Register to other deed types would require to be supported by the immediate Keeper induced-registration (KIR) of the property that is to be subject to the deed. The Keeper’s view70 is that closing the Sasine Register to other deed types is best left until the volume of remaining properties is of a manageable scale to allow for a prior KIR; indeed it if KIR is to be aggressively used it may be that this provision will never be used as it may have the effect of running counter to a planned programme of KIR.

The crucial point is that the 2012 Act provides for the practical closure of the Sasine Register to an increasing range of deed types at some future point; a necessary pre-requisite for completion of the Land Register though not in itself actually delivering completion. For that to happen, there requires to be a subsequent transaction affecting a property held on title deeds in the Sasine Register in order to trigger registration in the Land Register. For most properties, there will eventually be a transaction but the point at which that transaction occurs could be well in to the future. Additionally, there will remain a percentage of properties that remain off the Land Register radar. If completion is to happen in a timescale other than that determined by the natural pace of the property market, the remaining unregistered properties need to be identified and brought on to the Land Register. Identification of land not on the Land Register is straightforward. If it has not been mapped and accorded a title number under the 1979 Act (cadastral unit number under the 2012 Act) then quite simply it has not been registered.

In order that this land can then be registered, the 2012 Act gives the Keeper the power to undertake KIR.71 This power, active from the designated day, allows the Keeper “to register an unregistered plot of land or part of that lot.” No application for registration is required and nor is the involvement or consent of the owner required though the Keeper must notify the owner upon completion of registration. So is KIR the answer to the question of whether or not completion is feasible?

It is unquestionably a large part of the answer. It cannot assist with those properties whose titles are not on the Sasine Register but, in principle, it can aid identification of those properties as they will be the gap areas left in a registration county once KIR has been completed. But just how practical is KIR? The SLC are relatively positive about it:72

The draft Bill accordingly makes provision for the final completion of the Register. The Keeper would simply be empowered to register any unregistered property. In practice, the Keeper would usually have enough information to make up the title sheet – information about boundaries, information about the identity of the owner, and information about any subordinate rights to be entered in the C and D sections as encumbrances or in the A section as pertinents. After all, when a title is registered in the Land Register, it is not (with very rare exceptions) moving out of the private realm. Title is already in another of the Keeper’s registers – the Register of Sasines.

There are two key phrases in this statement: “final completion” and “usually have enough information.” With a ten-year completion target, KIR will have to be used extensively. The completion consultation document envisages that through market growth, use of increased triggers, and the commitment to register public land, some 88% of Scotland’s property will be registered by end 2024.73 By the Keeper’s reckoning, that leaves some 275,000 potential property titles (though some titles will inevitably include multiple properties) that require to be brought on to the register by voluntary registration or KIR. Even if the appetite for voluntary registration grows to levels experienced in England and Wales at the height of their marketing campaign, some 150,000 or more potential titles will require to be tackled under KIR. Consequently the use of KIR will not be limited to completing the final parts of the cadastral map jigsaw; it will require to play a much more extensive role.

The critical question is whether or not the KIR powers lend themselves to be used in such an extensive manner. The answer will largely be determined by the information available to the Keeper. The extent to which the Keeper will have enough information, and what can be done when she does not, was the focus of the KIR section in the completion consultation document. For urban residential properties stemming from common routes of title, the Keeper is more likely to have sufficient information as she has already carried out pre-registration title examination and, for a large number of these properties, has pre-mapped them. Fortunately, in terms of absolute numbers, these properties will form the majority of the titles that KIR will seek to register. The completion consultation document notes that there are 700,000 such property titles.74 This does not mean that KIR will be straightforward but the challenges ought to be limited to issues other than mapping. Rural and commercial properties will be less straightforward, as indeed will be titles to minerals and other separate tenements of land, and will present a range of issues, not least the challenge of identification and mapping on to the cadastral map.

The challenge with KIR stems in large part from the absence of any active transaction and the associated involvement of legal professionals tasked with examining title, obtaining pre-registration reports, interacting with the parties and being clear as to what is to be presented for registration. The completion consultation document highlights areas around identification of the legal boundaries, establishing who the owner is and clarifying the encumbrances that affect a property, but also acknowledges that other legal and practical issues will undoubtedly emerge.

For a map-based Land Register, identifying and plotting the legal boundaries of a property on to the cadastral map is essential. Identification is the starting point for any KIR and will be the determining factor in assessing the ability of KIR to enable completion. The 2012 Act acknowledges that under KIR, the Keeper may not always be able accurately to identify the legal boundaries.75 This alludes to the challenge of Sasine deeds, particularly older deeds and deeds relating to properties in rural areas where descriptions can be as general as “all and whole the farm and lands of hightae.” Such a description would not meet the Keeper’s deed plan criteria and so, in 2012 Act parlance, the conditions of registration would not be met. Yet the expectation is that KIR will overcome such technical difficulties. When the Land Register nears final completion, the challenge may be less as the entries already on the Land Register may offer a sufficient guide to the legal boundaries of the remaining unregistered properties. Where the volume of properties to be dealt with by KIR is large, the help offered by existing Land Register entries is less useful. The Keeper will have access to a range of old county series maps and more up-to-date Ordnance maps as well as any neighbouring registrations to assist in the mapping but this may not be sufficient in all cases to enable the boundaries to be plotted with absolute certainty.

The reality is that general descriptions could lead to the Keeper under- or over-mapping the extent of the property. If the extent is under-mapped, the proprietor will become aware when the Keeper notifies them with details of the registration, as is required. If the extent is over-mapped, the 2012 Act provides a general exception to the Keeper’s warranty the effect of which is that the “over-registration” is not warranted. The owner or a third party with title and interest would be able to apply for rectification. If it is under-mapped, the registered proprietor will not have lost their land. It will remain in the Sasine Register and the assumption is that they would seek to rectify their title to include the omitted land. A technical solution is one thing but if such problems were to become commonplace there is a risk that KIR could be brought in to question. The same argument applies to the solution the 2012 Act offers in relation to problems identifying the proprietor;76 these provisions resolve practical problems but there is as yet no clarity on the extent to which they would need to be used.

Notwithstanding that the 2012 Act seeks to provide statutory solutions for certain issues, the Keeper is mindful of the impact of the application of those solutions on those who own the properties in question. The challenge for the Keeper is to ensure KIR works in practice, to be transparent as to its use and ensure that its widespread adoption does not undermine the credibility or integrity of the Land Register. The completion consultation document emphasised that considerable more analysis and public discussion is required around the use of KIR. The Keeper proposes a series of pilot exercises to inform KIR, followed by a further public consultation focusing on the options for using KIR to enable completion. The proposed pilots will, in part, inform whether or not the 2012 Act provides a sufficiently flexible and robust basis for accommodating all possible title scenarios. (It is possible that the pilots will highlight issues that may benefit from a legislative solution.) At present it is not practical to draw firm conclusions other than to acknowledge that the ten-year completion target will require the extensive use of KIR.

(4) Will completion happen in ten years?

It is clear the road to completion will be well advanced. Market activity, the commitment to register public land, the proposed closure of the Sasine Register to other deed types and the continuing use of voluntary registration will all contribute to advancing completion. As indicated previously, the Keeper estimates that this would result in some 88% of property titles being registered. Indeed, the more active the property market, the less challenging and costly the task of completion. A return to the boom years of the mid 2000s, where the annual intake of first registration applications exceeded 50,000 per annum, would have a marked impact on the ease of completion and would reduce the dependency on both voluntary registration and KIR. However, achieving absolute completion, in the sense that every area of land or separate tenement of land, be it large or small, is on the Land Register with an identified owner is unlikely. There are a number of areas of challenge.

The main area falls around the many political considerations that have to be overcome. This essay does not focus on them; it acknowledges that there are cost issues for public bodies, resource allocation considerations for Scottish Ministers, the need for the legal marketplace to grow and accommodate the demand for legal resource, the need for continued political commitment and, of course, the flexibility of RoS to manage an unprecedented growth in applications. In many ways, these will be the determining factors but they are beyond the scope of an essay that is focused on whether or not the technical tools exist to enable completion within the ten-year target.

A key challenge will be those properties that are not held on titles recorded in the Sasine Register. These are largely unquantifiable. The ones that are known can be targeted for voluntary registration or could potentially form the subject matter of a KIR, based on working in tandem with the owner to register the land. Inevitably, many of these areas will only come to light as the Land Register nears completion. Strategies for dealing with those areas will need to be formulated and one senses that the matter may end up being the subject of further public consultation.

Linked to this are those areas of ground that unwittingly remain on titles recorded in the Sasine Register. As discussed previously, the 1979 Act encouraged this behaviour. Identifying these title issues will similarly only be practical once completion nears but resolving them may prove time consuming and resource intensive. On a pure cost versus benefit ratio, consideration will have to be given as to whether or not the cause of transparency is sufficiently aided by resolving the ownership question for these areas. A variation of this challenge relates to mineral titles. There are very few mineral titles in the Land Register. The majority of entries for property on the Land Register will note that the minerals have been reserved but will offer little guidance on where title rests. In some cases, the mineral title will rest on deeds recorded in the Sasine Register, though some will not, but identifying title will not necessarily be straightforward.

The use of voluntary registration needs to become much more frequent than is the case currently and needs to extend beyond public bodies. The HMLR experience suggests that there is a market for voluntary registration; the challenge is to tap that market. The benefits of registration can be extolled, support from RoS can be offered and for some this will be sufficient. The Keeper is already reporting an upsurge of interest and joint initiatives based around the use of voluntary registration is progressing with a number of landowners and other bodies with significant landholdings. Somewhat perversely, one factor that may dissuade some property owners is that of KIR. Quite simply, KIR is free, voluntary registration is not. The risk the Keeper has to manage is that some property owners who are the subject of a voluntary registration campaign (large landowners for instance) may opt to do nothing in the knowledge that within a ten-year timeframe their property will have to be picked up under KIR. The less interest in voluntary registration the greater the scale of the KIR exercise the Keeper will be faced with. That of course will place pressure on the ten-year timeframe.

Linked to the above is the question of land owned by UK public bodies, such as the Ministry of Defence. These landholdings are not insignificant: the Secretary of State for Defence alone owns an estimated 2% of Scotland’s land mass.77 The commitment to register all public land within five years was first made against the backdrop of the independence referendum. Had the outcome of that referendum reflected Scottish Ministers’ desires for an independent Scotland, then at some point in the near future all land owned by UK public bodies would have transferred and come within the orbit of Scottish Ministers. That is no longer the case and so presents a challenge for completion; Scottish Ministers can but encourage their UK counterparts to voluntarily register. If they choose not to then the remaining option is KIR. (That approach can of course create a tension with Scottish public bodies, particularly local authorities, who are being asked to progress registration of their landholdings through voluntary registration, which unlike KIR attracts a registration fee.)

The manner in which KIR can deliver completion is an unknown. In the same way that a series of policies and work practices were developed by the Keeper to support the 1979 Act, a similar approach will be required for KIR. The Keeper’s recommendation in the completion consultation document that a series of pilot exercises be run to gain greater understanding of the range of practical and legal issues to be addressed is an acknowledgment of that. Only once the pilots have concluded and been analysed and the findings and options for progressing KIR shared in a public consultation will it be possible to draw any definitive conclusions as to the use of KIR and the priority it should be given in delivering completion. It is, however, already clear that in offering solutions to some of the most pressing challenges the Keeper will encounter, the 2012 Act did envisage that KIR titles will not necessarily have the look and feel or the legal equivalence of other registered titles. Just how different they may be is yet to be seen but in an acceptance of that may lie the answer to completion.

E. Conclusion

Completion of the Land Register is now high on the political agenda. The continuing focus of the current Scottish Government on land reform matters has ensured a greater awareness amongst community groups, public and private bodies, professional organisations, land charities and citizens as to the information currently available on land ownership in Scotland and the central role of the Land Register in providing that information. This focus is timely, coming as it does on the heels of the implementation of the 2012 Act: legislation that has at its heart the completion of the Land Register.

Setting a ten-year target has brought an immediate focus on the completion provisions in the 2012 Act. They offer a significant improvement on the triggers for registration contained in the 1979 Act and compare favourably with the legislative framework for progressing completion that HMLR operates with. The 2012 Act provides a strategy: progressive closure of the Sasine Register to an increasing range of deeds, continued encouragement for voluntary registration, and the rolling introduction of KIR as operational counties near completion. The SLC’s suggested timeframe for implementation of that strategy was not 10 years: they envisaged a longer time-scale.78 Notwithstanding the timescale for delivering the strategy has shortened, the strategy that underpins the 2012 Act remains largely appropriate.

Achievement of the target will depend, in large part, on continuing political will; political support will be necessary if the legal powers in the 2012 Act are to be used to full effect. If the political desire to see completion continues, and signs are positive given the cross-party support for the completion provisions in the then Land Registration etc (Scotland) Bill, then year-on-year progress to meeting the target will be evidenced. The powers to close the Sasine Register to deed types and those relating to KIR will be instrumental in delivering near completion. Further analysis on and options for the widespread use of KIR will be forthcoming from the Keeper. The Keeper is confident KIR can be used to drive completion but assessment of that confidence must await publication of the planned public consultation on its use.

With continuing political support completion will be well advanced by 2024 and indeed it may, at a practical level, be considered achieved. Inevitably, there will be areas of land for which no title can be readily traced and also areas where there is doubt as to where title rests. There may also be some registrations, particularly of bodies with extensive and complex landholdings where parts of that portfolio are still a work in progress. But come 2024 the completion landscape will have changed and the focus will have moved from enabling completion to ensuring Scotland maximises the social and economic benefits of a complete or near complete Land Register.

1 Registration Act 1617.

2 Land Registration (Scotland) Act 1979 (Commencement n 1) Order 1980, SI 1980/1412.

3 The Land Registration (Scotland) Act 1979 (Commencement n 16) Order 2002, SI 2002/432, brought on to the Land Register the registration counties of Banff, Moray, Nairn, Ross and Cromarty, Caithness, Sutherland and Orkney and Zetland.

4 Professor George Gretton commenting on Kaur v Singh: see 1997 SCLR 1075 at 1085.

5 Scottish Parliament Official Report, Economy, Energy and Tourism Committee, 6 Mar 2012, col 58.

6 Land Registration etc. (Scotland) Bill: Economy, Energy and Tourism Committee Stage 1 Report – Scottish Government Response (2012).

7 Land Reform Review Group, The Land of Scotland and the Common Good (2014).

8 Para 32.

9 Scottish Government, “Target Set to Register all Scotland’s Land” (news release), 25 May 2014.

10 Scottish Parliament, Official Report, Economy, Energy and Tourism Committee, 6 Mar 2012, col 19.

11 Scottish Law Commission, Report on Land Registration (Scot Law Com n 222, 2012) vol 1 para 33.17.

12 Registers of Scotland, Completion of the Land Register Public Consultation (2014).

13 Land Registry, Practice Guide 1: First Registrations (2003) para 1.2, available at http://www.gov.uk/government/publications/first-registrations/practice-guide-1-first-registrations. One additional advantage they list is making large holdings of land and portfolios of charges more readily marketable.

14 Scottish Law Commission, Report on Land Registration (n 11) vol 1 para 33.18.

15 Land Reform Review Group, The Land of Scotland and the Common Good (n 7) Ch 23.

16 HM Land Registry, Annual Report and Accounts 2013/14 (2014) 43.

17 Registers of Scotland (RoS) estimates, current as of November 2014.

18 Based on Land Register intake figures from April 2004-March 2014.

19 Sasine Register Minute Book entries April 2004-March 2013.

20 Sasine Register Minute Book April 2013-March 2014.

21 Land Register (Scotland) Rules 2006, SSI 2006/485, r 9(i)(a) (Part B question 2(a)).

22 Land Registration etc (Scotland) Act 2012, ss 43-45.

23 Land Registry Act 1862.

24 Registers of Scotland, Completion of the Land Register Public Consultation (n 12).

25 Land Register, Annual Report and Accounts 2005/06 (2006) 14.

26 Under s 20(5)-(6), the Registry had to give 6 months’ notice to the council concerned and if within 3 months the Council held a meeting with at least two thirds of councillors present that rejected compulsory registration, then the order could not be made.

27 In 1899 London County Council became the first area to adopt compulsory registration following a sale. An attempt to pass a motion to prevent this under s 20(6) was defeated by 73 votes to 35 (The Times, 16 Feb 1898).

28 Land Registration Act 1925 s 120.

29 Registration of Title Order 1989, SI 1987/1347, available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1989/1347/contents/made. These were the districts of Babergh, Castle Point, Forest Heath, Leominster, Maldon, Malvern Hills, Mid Suffolk, Rochford, St Edmundsbury, South Herefordshire, Suffolk Coastal, Tendring, Wychavon and Wyre Forest.

30 HM Land Registry, Annual Report and Accounts 2013/14 (n 16) 11.

31 Land Registration Act 2002 s 6.

32 2002 Act s 7(1).

33 Ibid s 4(1)(g).

34 Ibid s 4(1)(a)(ii).

35 John Peaden, Director of Operations. A sampling survey on first registration cases marked off on 1 September 2014 from Birkenhead, Coventry, Croydon, Durham, Fylde, Gloucester, Hull, Leicester, Nottingham and Peterborough offices showed that 11% were triggered by the assent provision.

36 Section 5 of the 2002 Act allows s 4 to be amended.

37 The Land Registration Act 2002 (Amendment) Order 2008, SI 2008/2872 which came into force on 6 Apr 2009. Available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2008/2872/introduction/made

38 See the 10 year Strategic Plan included in HM Land Registry, Annual Report and Accounts 2002/03 (2003).

39 HM Land Registry, Public Consultation – The Comprehensive Land Register (2007) 10.

40 Land Registry, Annual Report and Accounts 2011/12 (2012).

41 HM Land Registry, Annual Report and Accounts 2013/14 (n 16).

42 Figures provided by HMLR and derived from annual reports.

43 Registration of Title to Land in Scotland (Cmnd 2032: 1963) (“the Reid Report”) and Scheme for the Introduction of Registration of Title to Land in Scotland (Cmnd 4137: 1969) (“the Henry Report”).

44 Registration of Title to Land in Scotland (n 43) para 91.

45 Ibid.

46 Scheme for the Introduction of Registration of Title to Land (n 43) para 11.

47 Registration of Title Practice Book, 1st edn (1981) para C02.

48 Companies Act 1985 s 410.

49 Section 58(1) of the 2012 Act provides an advance notice has effect for the period of 35 days.

50 1979 Act s 2(1)(b).

51 Registration of Title Practice Book, 2nd edn (2000) para 2.9.

52 F Ewing and S Adams, “All aboard the Land Register,” 17 Oct 2011, available at http://www.journalonline.co.uk/Magazine/56-10/1010324.aspx

53 1979 Act s 2(5).

54 Registration of Title Practice Book, 1st edn (n 47) para C16.

55 HC Debs, First Scottish Standing Committee, 27 Mar 1979, col 13.

56 Scottish Executive, Land Reform: Proposals for Legislation (E/1999/1), Para 6.3.

57 Registers of Scotland, Completion of the Land Register Public Consultation (n 12) para 16.

58 RoS, figures accurate to end Mar 2014.

59 Idem.

60 Registers of Scotland, Completion of the Land Register Public Consultation (n 12) para 26.

61 2012 Act s 48(1).

62 Ibid s 48(6).

63 Ibid s 48(1).

64 RoS, Business Planning Forecast May 2014.

65 Automatic plot registration is required by the operation of sections 24, 25 and 30 of the 2012 Act.

66 RoS, Business Planning figures for the period January 2004-December 2013. From 1 January to 11 November 2014 some 1664 leased have been registered. The increase is in the main due to leases of airport car parking spaces.

67 2012 Act s 27(6).

68 Registers of Scotland, Completion of the Land Register Public Consultation (n 12) para 30.

69 RoS Business Planning, May 2014.

70 Registers of Scotland, Completion of the Land Register Public Consultation (n 12) para 27.

71 2012 Act s 29.

72 Scottish Law Commission, Report on Land Registration (n 11) vol 1 para 33.49.

73 Registers of Scotland, Completion of the Land Register Public Consultation (n 12) para 19.

74 Ibid para 18.

75 2012 Act s 74(3)(a)(ah).

76 2012 Act s30(5).

77 Ministry of Defence, Defence Infrastructure Organisation Estate Information (2014).

78 Scottish Law Commission, Report on Land Registration (n 11) vol 1 paras 33.65-33.67.