3. Violinists, Violin Schools and Emerging Trends

© Dorottya Fabian, CC BY http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0064.03

To introduce and contextualize the recordings analysed in chapters four to five and to account for cultural, personal and educational influences this chapter starts off by surveying the violinists whose Bach performance is in the focus of attention. Almost all discussions of violinists and their playing visit the issue of violin teachers and schools.1 As noted by some of these studies, the usefulness of such accounts is doubtful even regarding earlier violinists, but given the greater mobility and internationalization of musical training since the second half of the twentieth century, sorting out influences and delimiting stylistic boundaries are of interest in the present study only to the extent to which these inform the discussion of homogeneity versus plurality of styles or the possible blending of HIP and MSP. While Milsom largely deals with earlier artists, Ornoy provides a “genealogy” of teachers and schools of most of the violinists considered here.2 Biographical information on most of them is also readily available on the internet and various encyclopaedias. Therefore I provide only a very basic overview, focusing on those violinists who will be mentioned more frequently and on information regarding their Bach-playing. I cite potentially decisive influences and events as well as some violinists’ opinions on certain issues in the “Influence of HIP on MSP” section, in so far as they seem relevant to the main focus: the musical interpretation of Bach’s Solos for Violin.

The recordings under study showcase roughly four generations of violinists (cf. Table 1.1). The smallest cohort is the oldest, born during the first three decades of the twentieth century: Oscar Shumsky (1917-2000), Ruggiero Ricci (1918-2012), Jaap Schröder (b.1925), and Gérard Poulet (b.1938). Out of these, the Philadelphia-born Oscar Shumsky studied with the famed Leopold Auer and, after his death, with Efrem Zimbalist, but as a child prodigy he was also in close contact with Fritz Kreisler. Later he became a teacher at various US conservatories, including the Curtis Institute of Music (Philadelphia) and also the Juilliard School of Music (New York) from 1953. His Bach recording is interesting because of his reputation among fellow violinists and also because of his association with Glenn Gould through the Stratford Festival in Ontario during the early 1960s. There he played with Gould and the cellist Leonard Rose in all Bach programs as well as other repertoire.3

Ruggiero Ricci, like Yehudi Menuhin, was from the West Coast of the United States and, just like him, first studied with Louis Persinger,4 and then went to study in Europe. He chose to go to Berlin, though, to study with Georg Kulenkampff, rather than George Enescu in Paris, as Menuhin did. Thus he was exposed to the German tradition best represented by Adolf Busch. As with most violinists, Ricci studied with others as well, including Paul Stassevich and Michel Piastro. His distinguished career as virtuoso and promoter of nineteenth-century violin repertoire spanned over seventy-five years. He gave master classes all over the world (including at the Mozarteum in Salzburg) and also taught at Indiana University and the Juilliard, among others. His Bach-playing is represented here by concert recordings from 1988 and 1991 of the A minor Sonata and D minor Partita only, both displaying his celebrated sweet tone and romantically inclined expression.

The Frenchman Gérard Poulet studied at the Paris Conservatoire with André Asselin. After winning the Paganini International Competition in 1956 he continued his studies with a series of renowned violinists of the mid-twentieth century, most of whom were also famed for their Bach interpretations: Zino Francescatti, Yehudi Menuhin, Nathan Milstein and Henryk Szeryng. Poulet’s recording of the complete set from 1996 is interesting as it has many movements that are lightly bowed and clearly articulated while elsewhere his playing exhibits the hallmarks of MSP.

Jaap Schröder stands out in this oldest group of violinists for being closely associated with the early music movement. He studied at the Amsterdam Conservatory between 1943 and 1947 with Jos de Clerck and with Jean Pasquier at the Ecole Jacques Thibaud in Paris. He joined Gustav Leonhardt, Anner Bylsma and Frans Brüggen around 1960, establishing the Quadro Amsterdam to explore historical performance practices of eighteenth-century music. He became a well-known teacher5 and chamber musician (e.g. Concerto Amsterdam, Quartetto Esterhazy) of the baroque and classical violin, as well as an orchestral leader (e.g. Academy of Ancient Music). Schröder has lectured widely on historical playing conventions and also published on performing the Bach Solos.6 His interpretation will often be referred to as it offers an interesting case. Although he was the oldest violinist among HIP specialists who made a recording of the Solos, he did so quite late in his career (1985) and considerably later than the earliest such versions (1977, 1981). His performance thus provides insights into generational boundaries and developments in period violin technique.

The pool of the youngest players, hardly in their late twenties as the first decade of the twenty-first century came to its close, is similarly small: Ilya Gringolts (b.1982), Julia Fischer (b.1983), Sergey Khachatryan (b.1985), and Alina Ibragimova (b.1985). The four of them have diverse paths but some shared backgrounds as well.

Ilya Gringolts went from St Petersburg and the tutelage of Tatiana Liberova and Jeanna Metallidi to the Juilliard and studied with Dorothy DeLay and Itzhak Perlman but then returned to Europe. Currently he resides in Switzerland and is professor of violin at the Basel Hochschule für Musik. In an interview with Inge Kjemtrup in 2011 Gringolts claims that he had been “at a crossroads musically, where I was questioning everything” while he was studying with Perlman. “I was not happy with my playing in many respects,” he says.

I was looking around, trying to absorb a lot of influences and trying to make sense of them. I don’t know if any teacher would have helped at that point. He was there for me, but he didn’t really know how to handle me at that time[…].7

In this same interview Gringolts states that his Bach Solos recording was a “real transition, meaning that I just started moving in one direction and I was still moving as I was recording. But later I did really explore period performance and Baroque playing.” The “transitory” stage of his approach to Bach at the time of making the recording under study here will be evidenced and commented upon on multiple occasions. His onward move towards HIP can be witnessed in his collaboration with Masaaki Suzuki, performing the Bach accompanied sonatas.8

Julia Fischer mostly remained in her native Germany, her main teacher being Helge Thelen. Her 2005 recording was well received by reviewers who praised the recording’s “immaculate finish” and Fischer’s “ability to trace a smooth, even line” while desiring “more in the way of expressive flexibility.”9 As we will see, her approach on this disk to interpreting Bach is much closer to the traditional MSP style and, like Sergey Khachatryan’s from 2010, somewhat fades into grey eminence in comparison with many others issued around the same time. As the reviewer in Gramophone noted, Fischer’s performances “are in general lightly pressured, leisurely and at times rather austere […] a sort of half-way house between period-style asceticism and a more emotive style associated with the various twentieth-century schools.”10

Khachatryan is Armenian but has been living in Germany since 1993, when he was eight, and in 2000 became the youngest ever winner of the Jan Sibelius competition. In relation to his debut compact disk with EMI the reviewer in Gramophone noted already in 2003, that his Bach performance “is impressive […] for its polish and fine rhythmic control but Kachatryan does have something to learn about playing eighteenth-century music—in particular to use the slurs to add light and shade to the phrasing, rather than ironing out the difference between slurred and separate notes.”11 The advice was apparently not taken on board, for the disk of the Six Solos recorded seven years later shows very similar ironed-out traits.

Of this youngest generation only Alina Ibragimova’s set exhibits the influence of HIP. She was born in Russia and studied with Valentina Korolkova in Moscow before moving to London and joining the Menuhin School under the tutelage of Natasha Boyarskaya. Later she completed her training at the Guildhall and the Royal College of Music (under Gordan Nikolitch). She also studied with Christian Tetzlaff, which is noteworthy given all the observations I will make about his two recordings throughout the book but especially in chapter five. Ibragimova’s interest in HIP is most unequivocally demonstrated by her founding of Chiaroscuro, a period-instrument string quartet that focuses on performing the classical repertoire.

In between the oldest and youngest performers represented by the recordings, there are two further generations: those born in the 1940s to early 1960s and those born between the mid-1960s and the end of the 1970s. Discussion will inevitably centre on those players who are either better known or contributed interpretations of particular note. From the first group these include Sergiu Luca (1943-2010), Sigiswald Kuijken (b.1944), Gidon Kremer (b.1947), Elizabeth Wallfisch (b.1952), Monica Huggett (b.1953), Viktoria Mullova (b.1959) and to a lesser extent Itzhak Perlman (b.1945), Lara Lev (birth year not known) and James Buswell (not known). From the younger group Thomas Zehetmair (b.1961), Richard Tognetti (b.1965), Christian Tetzlaff (b. 1966), Rachel Podger (b.1968), Lara St John (b.1971), Isabelle Faust (b.1973), Rachel Barton Pine (b.1974), James Ehnes (b.1976) and Hilary Hahn (b.1979) will be repeatedly mentioned.

Originally from Rumania, Sergiu Luca lived in Israel from 1950 and later studied with Max Rostal in Europe before emigrating to the United States of America, where he studied with Galamian at the Curtis Institute and won the Leventritt Award before turning to period instruments and becoming a pioneer of HIP. His recordings of Mozart’s sonatas with Malcolm Bilson are no less revolutionary than his solo Bach; each being the first of its kind by far.12 The Belgian Sigiswald Kuijken, on the other hand, remained close to home, joining the innovative Flemish-Dutch branch of the early music movement during the 1960s-1970s. He eventually became a seminal figure not just as one of the first professors of baroque violin and consequently the teacher of many later players, but also as founding conductor of La Petite Bande (1971) and as a chamber musician in several projects involving Gustav Leonhardt, among others.

Monica Huggett first studied at the Royal Academy of Music (London) with Manoug Parikian and Kato Havas and later became one of the first students of Kuijken at the Royal Conservatory in The Hague. She was a close associate of Ton Koopman, with whom she established the Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra and whose influence she frequently acknowledges. Apart from her solo career she is also well known as a professor of baroque violin (in Bremen and, since 2008, also at Juilliard) and as a concertmaster and conductor of period orchestras. Huggett has frequently mentioned in interviews her youthful desire to be a rock musician and her reluctance to conform.13 Her recording from 1995 is infused by this strong sense of individuality through and through. Hence it is worth noting further what she tells us about her life and inspirations.

As a kid, Hugget’s brother introduced her to jazz giants Charlie Parker and John Coltrane while later she became a fan of the Beatles, Jimi Hendrix and the Beach Boys. Most importantly, “[f]rom an early age I didn’t like the way that I had to play if I was playing with a big Steinway. It wasn’t my idea of what a violin should sound like and I always felt that the instrument had more possibilities in terms of tone quality and nuance.”14 She felt immediately happier when a friend “said my style would suit a gut fiddle, and she lent me one. “Oh yes,” I thought, “this is really nice.”’15 Huggett also notes how much she admired “Henryk Szeryng’s amazing set of Bach (Sony MP2K 46721) for its “mind-bogglingly [technical] perfect[ion]”16 but how, at the time of recording the set, she rather took inspiration from jazz-rock guitarist John McLaughlin’s album My Goals Beyond. Apparently the “first recording she heard of authentic instruments” was Rameau’s Pièces de Clavecin en Concert performed by Gustav Leonhardt with Sigiswald and Wieland Kuijken (Teldec 9031-77618-2).17 Characteristically Huggett is not afraid to admit listening to and imitating others’ performances and recordings.

I believe that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, and I’m not afraid to imitate something that really works. Some musicians have got a thing about not ever sounding like other artists, but that doesn’t worry me at all. If I think somebody else did something really well, I’ll happily copy it. But funnily enough, I generally find that the end result doesn’t sound like any of them.18

Perhaps most tellingly, Huggett sees

Bach as this big North German with huge hands who could stretch a tenth and play all the parts in between, a great big chap who was difficult, passionate, overwhelming and larger-than-life. His music should be full-blooded; you shouldn’t be feeling ‘I mustn’t do this, it’s too much,’ but really go for it!19

Huggett’s performance of the set certainly “goes for it.” She often takes slow tempos paying attention to every little detail but also joyously plays around with certain dance movements, like the E Major Gavotte en Rondeau, adding a showy cadenza. Elsewhere she deepens the music’s sad or melancholy character through soulful embellishments (e.g. D minor Sarabanda) or rapturous tempo and rhythmic flexibilities. Her unique style will be the focus of attention in the final part of chapter five.

The similarly flamboyant Elizabeth Wallfisch (only one year senior to Huggett) was born in Australia but also trained in the Royal Academy of Music under Frederick Grinke. Currently residing in England, she became a specialist HIP violinist during the early 1970s, and is renowned for founding the Locatelli Trio and for her appearances with the Australian Brandenburg Orchestra, the Hanover Band and many other European period-instrument orchestras. She also teaches baroque violin at the Royal Conservatory in The Hague and the Royal Academy of Music in London. She recorded the set just a few years after Huggett did and her reading is almost the polar opposite of Huggett’s; much faster, more virtuosic, strongly accented and displaying an entirely different timbre.

Although approximate contemporaries of the above named players, the artistic trajectories of Perlman, Kremer, Mullova, Lev and Buswell are quite different. Itzhak Perlman was thirteen years old when he was “talent-hunted” from Israel by Ed Sullivan for his touring show, “Cavalcade of Stars,” which eventually led to studies with Ivan Galamian and Dorothy DeLay at Juilliard. He was barely eighteen when he won the Leventritt Award in 1964, an achievement that launched his solo career. For many years he has taught at Brooklyn College and at the Perlman Program, a summer school on Long Island established by his wife. In 1998 he started co-teaching with DeLay at Juilliard, eventually succeeding her.

Gidon Kremer was David Oistrakh’s prized student before he emigrated to the West, a fully formed virtuoso soloist, in the late 1970s. He followed his own path, playing the staple repertoire of classical and romantic concertos, commissioning and promoting new works, collaborating with diverse conductors (from Herbert von Karajan to Nikolaus Harnoncourt) and chamber orchestras, and eventually forming his own ensemble, Kremerata Baltica, in 1996. He is known for his musical integrity, wide ranging repertoire and promotion of new music.

Lara Lev and Viktoria Mullova could have followed a similar path, both having been trained in Soviet Conservatoires: Lev studied with Yuri Yankelevich and Vladimir Spivakov in Moscow, while Mullova’s teacher was Leonid Kogan. Lev played in orchestras before taking a teaching post in Helsinki during the 1990s and then joining the Chamber Music Faculty of Juilliard in 2008. In contrast, Mullova focused on solo performance: she won the Sibelius competition in 1980 and the Gold Medal at the Tchaikovsky Competition in 1982, before defecting to the West in 1983. She became an internationally known soloist and over time completely overhauled her playing of baroque music as evidenced by her three recordings under study here, the B minor Partita from 1987, the three Partitas from 1992-1993 and the complete set from 2007-2008.20

James Buswell, currently professor of violin at the New England Conservatory (Boston, Massachusetts), initially trained at Juilliard with Ivan Galamian and then worked at both the Lincoln Centre in New York and the Music School of Indiana University. His interest in Bach’s Solos led to a documentary for the PBS Network and a recording on the Centaur label. He is highly respected for his dedication to new music and performances of the chamber repertoire. His recording of the Solos is of special interest because he was one of the last teachers of the Canadian Lara St John, whose interpretation will often be mentioned.

Among the younger group of mid-career violinists Rachel Podger (b.1968) and Ingrid Matthews (b.1966) are baroque specialists while Thomas Zehetmair (b.1961), Richard Tognetti (b.1965), Christian Tetzlaff (b.1966), Benjamin Schmid (b.1968), Lara St John (b.1971), Isabelle Faust (b.1973) and Rachel Barton Pine (b.1974) are not, even though some of them may opt for a baroque bow and gut strings, or speak of being influenced by the tenets of HIP, as I will detail later.

In terms of his age, the Austrian Thomas Zehetmair could belong to the previous, older group. However, his radical performing style makes it more natural to regard him as belonging to this third generation of violinists. Among non-specialists he was one of the first to “cross-over” and learn from Nikolaus Harnoncourt’s classes while at the Salzburg Mozarteum, eventually making a recording with the conductor (Mozart Haffner Serenade, Teldec 1986). Nowadays Zehetmair works mostly as a conductor but earlier in his career as violinist he undertook master classes with Nathan Milstein and Max Rostal.

Benjamin Schmid, also an Austrian, is renowned for playing jazz as well as classical music. He tends to mention the influence of Yehudi Menuhin and Stéphane Grappelli, and studied in Salzburg, Vienna and at the Curtis Institute. His recording exhibits an interesting, at times rather idiosyncratic, combination of MSP and HIP features.

The Germans Tetzlaff and Faust both have international reputations and both play the gamut of the standard violin repertoire. Christian Tetzlaff first studied with Uwe-Martin Haiberg (Lübeck Hochschule für Musik) and then with Walter Levin at the University of Cincinnati. He is a regular soloist with many orchestras and has an extensive discography covering works from Bach to Bartók and beyond. The younger Isabelle Faust is one of the more original players on the current scene. She studied with Denes Zsigmondy and Christoph Poppen, whom she often cites as inspirational. Having established her first string quartet at the age of 11, she continues to be an active chamber musician. In 2004 she was appointed professor of violin at the Berlin University of the Arts. Faust is well-known for her interest in exploring different musical idioms and new repertoires, including contemporary music. She has also collaborated with performers who specialise in baroque and classical music and for her recording of three of the Bach Solos she worked closely with fortepianist-harpsichordist Andreas Staier. The second disk of her Bach Solos (containing the G minor and A minor Sonatas and the B minor Partita) came out only in 2012; too late for me to include it in the current discussion. Suffice to say perhaps, that she tends to choose rather fast tempos in all movements on this second disk that gives the interpretation a rather hurried and somewhat routine feel in spite of the original added embellishments in the A minor Andante and B minor Sarabande movements. The tone could also be warmer although this may reflect recording technology more than her playing. Overall, I find Faust’s first disk containing the D minor and E Major Partitas and the C Major Sonata much more revelatory and convincing. All my comments regarding her interpretation refer to that disk from 2009 unless specifically indicated otherwise.

One of the first teachers of the Australian Richard Tognetti was William Primrose (1904-1982), the famed viola player, once a pupil of Eugène Ysaÿe. Perhaps more influential were Tognetti’s teachers at the Sydney Conservatorium High School (Alice Waten) and at the Bern Conservatoire (Igor Ozim). Since his return to Australia in 1989 Tognetti has been the leader and artistic director of the Australian Chamber Orchestra, an ensemble that plays a wide variety of repertoire (often especially transcribed by Tognetti or crossing boundaries with world music and other styles) on modern instruments. He has made several recordings as a soloist too, including Bach’s complete works for violin (Solos, Accompanied Sonatas and Concertos). For his recording of the Bach Solos, Tognetti chose lower tuning, gut E and A strings and a classical period bow. Reviewing it for Gramophone, Duncan Druce noted his varied bow strokes, limited use of vibrato and “persuasive ornamentation.” He described Tognetti’s interpretation as conveying

remarkable freedom and imaginative range, stemming from what is clearly a deep understanding of eighteenth-century performance style. The set, in fact, offers a closer comparison with the best period instrument versions than with a modern player such as Julia Fischer who, by the side of Tognetti, sounds smooth and bland, for all her sensitivity and stylistic awareness. […] His view of the music is so well founded that he is able to communicate with an air of complete spontaneity.21

In 1992, Chicago-based Rachel Barton Pine became the youngest American to win the gold medal at the Leipzig International Johann Sebastian Bach competition. A virtuoso musician, she performs her own cadenzas; prepares transcriptions and arrangements of all sorts of music; promotes the music of little known composers and black musicians; and plays with heavy metal bands (e.g. Earthen Grave) and early music groups (e.g. Trio Settecento). When performing baroque music, she opts for a period bow and gut strings. She issued one commercial disk containing the G minor Sonata and D minor Partita but she kindly made available to me two of her live concert recordings of the complete set: a series of radio broadcast concerts from 1999 and a marathon single day event (afternoon and evening) in 2007.

Barton Pine’s close Canadian contemporary Lara St John started learning the violin with Richard Lawrence in her home town, London Ontario, and later studied with Linda Cerone in Cleveland and Gérard Jarry in Paris. She received her degree from the Curtis Institute (studying with Felix Galimir and Arnold Steinhardt) and continued at the Moscow Conservatoire. This was followed by further studies at the Guildhall in London (under David Takeno), the Mannes College in New York (again with Felix Galimir) and finally the New England Conservatoire in Boston with James Buswell. Her Bach Solo album was described by one critic as “wild, idiosyncratic, and gripping.”22 Her interpretation of the G minor Adagio and A minor Grave are improvisatory in character and the fugues are light and fast; there are also a few idiosyncratic moments in other movements that I will discuss in chapter four. St John plays with a modern bow but uses little vibrato when playing Bach; her repertoire is wide-ranging but remains primarily within the concert tradition. In that she is less like Barton Pine and closer to Ehnes and Hahn, who represent the most traditional mainstream within this group of violinists.

James Ehnes studied at the Juilliard with Sally Thomas, graduating in 1997. He is one of the most prolific recording violinists of the past decade, covering mostly nineteenth- and twentieth-century works. According to his website (http://www.jamesehnes.com), The Guardian described his playing as “effusively lyrical […] hair raising virtuosity.” His 1999 recording of the Solos has all the hallmarks of MSP at the end of the twentieth century, but his more recent recording of the accompanied sonatas (with harpsichordist Luc Beauséjour) indicates that he too has started to adopt characteristics of the HIP style.

In contrast, Hilary Hahn remains true to her upbringing and initial aesthetic ideals. She studied with Klara Berkovich (who taught in the Leningrad School for the Musically Gifted for twenty-five years previously) from the age of five and with Jascha Brodsky for six years at the Curtis Institute. In a 2003 interview Hahn stated that although she “keeps abreast” with her own generation, she feels closer to “an older period, the artists of the same generation of my teacher and musical grand-father, Jascha Brodsky.”23 This is indeed quite clear when listening to her recording of three of the Solos (1999) and also a much more recent disk of Bach arias with violin obligato (2010).24

Out of the two HIP specialists in this generation of violinists Rachel Podger will feature more than Ingrid Matthews, partly because her disk came out earlier (1998 versus 2001) and also because it contains more variations from the score.25 Both of them have many recordings to their credit but Matthews seems to appear more frequently as leader of ensembles whereas Podger is primarily a soloist and guest director who also teaches at several institutions (including the Guildhall, the Royal Academy of Music, the Royal Welsh College and the Royal Danish Academy of Music). Her teachers at the Guildhall were David Takeno, Micaela Comberti and Pauline Scott. The American Ingrid Matthews studied at Indiana University with Josef Gingold and Stanley Ritchie. She won the Erwin Bodky International Early Music Competition in 1989 and served as leader of the Seattle Baroque Orchestra between 1994 and 2012, which she co-founded with harpsichordist Byron Schenkman. Apart from baroque music she has also made recordings of contemporary works.

Having surveyed some of the main violinists in my sample, a few words about so-called violin schools are also in order. Traditionally discussions of violin playing distinguished a German and a Franco-Belgian school of playing, the latter subsuming aspects of the Italian style. Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century representatives of the former were Joseph Joachim and his disciples, while the French school was embodied by Henri Vieuxtemps and Eugène Ysaÿe. The German school was regarded as analytical and sober and was epitomized by the “Berlin circle” and Carl Flesch’s famous studio in the first half of the twentieth century. The French school on the other hand was considered flamboyant and virtuosic, cultivating warmth of sound. Around the turn of the twentieth century a Russian school came to the fore headed by Leopold Auer at the St Petersburg Conservatoire. From his classes came such violinists as Jascha Heifetz, Misha Elman, Efrem Zimbalist, and also Nathan Milstein.26 Auer (1845-1930) himself studied mainly with Joachim, but stated that it was Jacob Dont in Vienna who “gave me the foundation of my violin technique.”27 Auer chose teaching rather than playing at the age of only twenty-three when he was appointed to the St Petersburg Conservatory; and later famously refused to premiere Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto, leaving the honour to Adolph Brodsky (1851-1929).28 He remained in his post for nearly 50 years, until the Bolshevik revolution in 1917 forced him to move to the United States. There he continued to teach for another twelve or so years, privately and at the Juilliard School as well as at the Curtis Institute.

According to Nathan Milstein, Auer hardly ever demonstrated during a lesson and neglected to teach technique: he encouraged his students to use their head, not their hands.29 This may be one reason why all his famous students sound so different. Milstein also claims that the students “almost never played Bach in Auer’s class. Bach was not at all popular in Russia then. […] Auer wasn’t interested in listening to Bach. He didn’t know what to say, and he said practically nothing.”30

Apparently Auer was “deliberately vague as to how to grip the bow” relying instead on “the physical structure of the student’s arm.”31 Yet the so-called Russian bow hold is often linked to Auer because Carl Flesch observed it in the playing of Heifetz and Elman, two of Auer’s best known pupils. This bow hold places the index finger lower and more over the bow while the Franco-Belgian grip has the index finger positioned so that the bow touches it around the middle joint.32 In an article about his career, Schröder is cited explaining that it was the French tradition of bowing that attracted him to study with Pasquier.

I observed how their bows not only sang, but also talked and danced. The extreme flexibility of their fingers on the bow shaped the sound with refined articulation. Their bow strokes could abruptly change speed and intensity at any part of the bow; slow languid movements were suddenly followed by biting spiccato produced by the finger joints of the bow hand. Their tone palette was full of surprises, from whispering sounds to an open and bright tone that has always been a hallmark of French string playing. I noticed that Jean’s wrist and elbow were not high, that his index finger was clearly steering the bow and had absolute control over the tone production.33

According to Schwarz, photographs show Auer holding the bow with the Franco-Belgian grip (so named by Flesch as well). He also claims that, if anybody, perhaps Wieniawski held the bow the way that came to be known as the Russian grip. He may have introduced it to Russia when teaching at St Petersburg during the nineteenth century.34 Later in his teaching career Flesch advocated the Russian grip; although it makes bowing less flexible, he still regarded it to be superior to the Franco-Belgian and old German grips because it produces a bigger tone.35 The rather uniform bowing typical of much violin playing on record from the second half of the twentieth century may be a result of this grip gaining ground through Flesch’s pupils and their pupils. However, bow hold may not be the main reason. According to pictures in Galamian’s method book, he seems to be teaching the Franco-Belgian grip.36 Perlman also describes his grip as Franco-Belgian.37 Furthermore, some players say they use both types of bow hold. Aaron Rosand, for instance, uses the Franco-Belgian grip for “Mozart, Bach, and pyrotechnical works.”38 Looseness of wrist, bow pressure and speed all contribute to tone and variation in tone.39 Without close study of visual documentation one can only speculate the constituents contributing to the impression of a more uniform style of bowing during the 1950s to 1980s period compared to the beginning of the century and since its last decade. The aesthetic ideal regarding a big, even sound may have been the most important driving force behind it.

Many Russian-Jewish violinists escaped to the United States of America at the end of the First World War and thereafter thus making the US the new home of the “Russian school,” whatever that might actually be. Among them was Jascha Brodsky (1907-1997), who became professor at the Curtis Institute, a music academy of equal prestige to the Juilliard School, thus influencing innumerable players (e.g. Hilary Hahn, as noted earlier). It is important to note, however, that Brodsky studied not only with his father but also with Lucien Capet and Eugène Ysaÿe, two key figures of the “Franco-Belgian School,” before moving to Philadelphia in 1930 (on advice from Mischa Elman) to study further with Efrem Zimbalist at the “newly founded Curtis Institute of Music.”40 So perhaps rather than a special technique or grip, the main attribute of the Russian school may well be its fairly stern pedagogical approach, a method that was typical of Auer as well as Flesch and many less famous teachers coming from Eastern Europe. This is related in numerous first-hand accounts and reminiscences, including Perlman’s:

With my first teacher, who was of Russian background, I would play something and she would say, “That’s wrong. You do this and you do that.” It was more like you’ll play and I’ll give you instructions, and Galamian was in a sense the same way.41

So the “American school,” dominated by Juilliard and Curtis, essentially became a continuation of the Russian school established by Auer. The two most famous and influential teachers associated with these institutions were Ivan Galamian (1903-1981) and Dorothy DeLay (1917-2002). According to Perlman, who studied at the Juilliard School with both of them for about seven years, “they had different approaches to teaching, but similar systems technically speaking, especially with the bow and the way it works. The goals of the two were basically similar—certainly technically they were.”42 Both DeLay and Galamian placed special emphasis on tone production and projection. According to Arnold Steinhardt, a pupil of Galamian, his students “were given two basic principles which he delivered with a heavy Russian accent: one was ‘More bow’ and the other was ‘Play so that the last person in the last row of the hall can hear you.’”43 Other pupils also emphasized this aspect of Galamian’s teaching: “He stressed warmth and good sound,” noted David Nadien, while James Buswell stated: “Galamian had a revolutionary technique for the bow arm […] the ability to project the violin sound at a time when halls are getting bigger […] has become ever more critical.” DeLay agreed that Galamian’s “students had good sound. Big healthy sounds.”44 DeLay seemed to have shared this principle with Galamian as her training routine focused a lot on developing sound, including vibrato. Cornelius Duffalo remembered how when he first came to her, he was directed to develop “a clean sound, a nice, clean, beautiful sound. Then we worked on vibrato.” Peter Oundijan also noted that DeLay gave him “terrific vibrato exercises,” while he “never heard [Galamian] teach vibrato.” According to Duffalo, DeLay expected her students to “work on every note so that every note has a beautiful beginning, a beautiful middle, and connects beautifully into the next note.”45

Where they differed was their pedagogy. The Armenian Galamian was educated in pre-revolutionary Moscow at the Philharmonic School by former Auer student, Konstantin Mostras, followed by a brief period with Lucien Capet in Paris between 1922 and 1924. Although he performed for a while, his focus had soon become teaching, first at the Russian Conservatory in Paris and from 1937 in New York. He eventually joined the faculties of both the Juilliard School (1946) and the Curtis Institute (1944) where he remained until his death in 1981. According to Sand, he “instructed and intimidated two entire generations of violinists” during his near forty years of tenure, and “his influence on performance style continues undiminished.”46 Sources agree that his teaching style was “old school authoritarian,” focusing on technical work and leaving nothing to chance. He believed that anybody could become a fine violinist if only they practised (“suffered through exercise”) and therefore “the first goal must be perfect control of the instrument.”47 According to Isaac Stern “it was never his forte or basic interest to teach a very large musical style” because he believed that the violinist’s musical personality could be developed later, once their technical command had been achieved.48

These aesthetic ideals and pedagogical views are important factors contributing to the much lamented homogeneity in classical music performance during the second half of the twentieth century. Leaving nothing to chance, focusing on technique rather than style and expression hinders spontaneity and exploration of what a composition may require to sound unique. Assuming that many other teachers had similar approaches, it becomes questionable whether it was primarily the demand of the recording industry that fostered uniformity and precision and discouraged risk-taking and experimentation in performance. Conservatoires and competition judges might have played a more crucial role.

Although sharing a similar aesthetic and technical outlook, the American DeLay was the complete opposite of Galamian when it came to pedagogy. She was motherly and had a holistic approach to developing not just technique but the musician and the personality as well. Not that she was less methodical or lenient. She provided her charges with practice sheets that mapped out the tasks of a five-hour daily routine.49 But she was interested in teaching her students how to think and how to become independent musicians. She would constantly probe them with questions like “Well, what do you think of that phrase? What could the composer want with such a passage? Why should it sound like this? Why don’t you experiment a little with bowing until you are satisfied with the sound?” She also routinely advised them “to get hold of as many recordings of a work as they can […] to compare the various performance styles.”50 Comparing her approach to Galamian’s, DeLay once remarked that having come from a traditional Armenian family where

the father’s word is law […] Mr Galamian felt that formalities must be adhered to and that in a situation with a child, he was the authority—that children were there to do as they were told. I just don’t feel that way about children, but then I’m an American and I’m a woman, and I have two children of my own.51

Her goal was to get inside the pupil, to help them find their own solution. Whether her students ended up being or sounding more individual than those who only studied with Galamian is beyond the scope of my investigations here because very few of them have recorded the Bach Solos. The lesson that bears significance for the present discussion is DeLay’s and Galamian’s shared principle of aesthetics and technique, which was rooted in a beautifully controlled, even, well-projected, warm sound. Given the reputation of the Juilliard School as “the real seat of stringed instrument power” in terms of “producing solo virtuosos,” the influence of this ideal should not be underestimated.52

Meanwhile, on the European Continent the pre-war era was dominated by the equally famous Carl Flesch in Berlin and George Enescu in Paris. After the Second World War various renowned music institutions have carried the torch for international “best practice” in violin playing and pedagogy. As the biographies above show, the most important of these have been the Guildhall, the Royal College and Royal Academy of Music; the Salzburg Mozarteum, and the conservatories in Amsterdam and The Hague. The last two institutions were also instrumental in pioneering the institutionalized training of historical performing practices.

The very first school to teach specialization in “early music” was the Schola Cantorum in Basel (established in 1933), where Leonhardt completed his studies in 1950.53 The Schola developed curricula; provided a forum for workshops, master classes and concerts; and brought together many continental musicians interested in reviving earlier performing practices. It was there that the Los Angeles based Sol Babitz, a much neglected and maligned violinist pioneer of the movement, was given the opportunity to demonstrate his findings regarding articulation and bowing. These masterclasses inspired the post-war generation. He was also invited by the Kuijken Quartet to give lecture demonstrations in The Hague.54 This openness and rapid embracing of the period instrument movement on the Continent meant that during the 1970s and early 1980s Amsterdam and The Hague were the places to go if one wanted to study harpsichord playing or to learn to play the baroque version of a string or wind instrument. From 1973 the Salzburg Mozarteum also offered courses in early music theory taught by Nikolaus Harnoncourt.55

Decca saw the commercial success of the continental groups and, apparently, wanted to recreate it in England. Christopher Hogwood recounted in an interview how the company recruited him to create an orchestra that would specialize in performing the music of the eighteenth century on period instruments.56 Of course there were many scholars and musicians in England, attached to various universities and cathedrals, who had been engaged with the early music movement all along. Yet formal training opportunities were not introduced until the 1980s and many of these institutions’ future leaders and first teachers had to gain specialist qualifications in the Netherlands. By now, however, most conservatoires around the world have an early music department. Many offer full degrees specifically in period instruments while others reserve the learning of such instruments for post-graduate training or as an optional or supplementary opportunity. The extent to which HIP has become accepted is demonstrated by the institutional recognition that knowledge of HIP maximises a musician’s employment prospects, thus it needs to be an essential part of tertiary or post-tertiary training. When the bastions of tradition like the Juilliard consider it important to introduce such a program at least at the graduate level as happened in 2008, then we can be certain that HIP is here to stay—it is current, it is fashionable, it is the contemporary style of playing baroque music.

As this brief overview shows, HIP is exerting an increasing influence on MSP not just at the individual but also at the institutional level. This may lead to a possible relaxing of dogma on both sides of the divide regarding how a piece of music “should go.” Music schools are establishing early music departments and many younger players are interested in or feel obliged to gain specialist knowledge, to diversify. I now turn to tracing the qualitative details of this trend.

3.3. The Influence of HIP on MSP

Chronologically speaking, the period under discussion shows an initial decline in the number of recordings made by MSP violinists of the Bach Solos during the 1980s and 1990s with a concurrent increase in those made on period instruments, especially during the 1990s. By the mid-2000s however this is reversed, with several non-specialists releasing complete sets. What is important to note, as mentioned earlier, is the fact that quite a few of them use a baroque bow (and often gut strings as well) or acknowledge in interviews or compact disk liner notes the inspiration gained from discussions and collaborations with period performance practitioners and musicologists (e.g. Barton Pine, Faust, Gringolts, Ibragimova, Mullova, Poppen, Schmid, Szenthelyi, Tetzlaff, Tognetti, Zehetmair). How far each of them goes or in what sense they adopt period performing aesthetics varies considerably and provides a fascinating landscape of performing Bach’s Solos at the beginning of the new millennium. I will discuss individual differences in more detail later on.

In general, the influence of HIP manifests most clearly in bowing and articulation, in vibrato use, and in an increase in added ornaments and embellishments during repeats. Recordings of period violinists also show this trend as their playing becomes more locally nuanced, metrically and harmonically articulated and richer in ornamentation.57 In both the HIP and MSP versions of more recent years one can observe greater flexibility in the timing of notes and shaping of phrases. This is largely due to the stronger articulation of smaller musical units and rhythmic groups. The trend towards a more interventionist (or less literal) approach reflects increased freedom and subjectivity and results in a pluralism that may be linked to the postmodern condition observed by Butt, among others.58 This development becomes even more apparent when the findings of the examination are ordered according to the age of the violinists rather than the recording date (cf. Table 1.1). The very strong correlation between similarities in performance characteristics and date of birth indicates, first and foremost, that soloists develop their distinctive interpretations early in their career and divert from it only rarely.59 This, in turn, assists us to see what the dominant interpretative modes are in any given decade or so; the aesthetic “common ground,” if you wish, that provides the framework for individual differences.

The much lamented “Urtext mentality” of the post-war era can be observed in recordings of violinists born between approximately 1945 and 1960 (e.g. Perlman, Mintz, Kremer 1980). The few even older players (e.g. Shumsky, Poulet) also displayed a similarly literal approach to the works, supporting the view that a decidedly literalistic (either “reverential / romantic-modernist” or “objective / classical-modernist”), technically highly polished playing of Bach had become an ideal already by the 1930s. As such readings were also detected in the recordings of four of the youngest MSP violinists (Ehnes, Hahn, Khachatryan, and to a lesser degree Fischer), this aesthetic seems to have a strong grip on the musical psyche of modern performers. It is tempting to think that the horrors of the First and then Second World Wars, followed by a series of radical social and cultural changes, induced lasting shifts in sensibilities or in willingness to exhibit the deeply personal.60 Perhaps less dramatically and unconsciously but in a rather more systematic and inevitable way, essentially musical developments must also have contributed to this new aesthetic. The canonization of the classical repertoire that brought about an increased reverence for composers and their scores had started already in the nineteenth century.61 Yet it seems to have been accomplished only around the 1950s, partly as a drive in historicism and associated preservation of cultural artefacts in the wake of the devastation of the Second World War. The ensuing decades saw further consolidation of this trend through renewed interest in critical editions and musicological dicta based on textual analysis. The more and more formalized and internationalized training of performing musicians—training that emphasized instrumental technique and projection of tone while de-emphasizing the composing and improvising that used to be part and parcel of many earlier virtuosos’ skills (e.g. Kreisler, Busch, Milstein, to name only violinists)—fostered an acceptance of the score’s authority and the performer’s role as an accurate transmitter of the composer’s text.62 Given the very gradual conquest of this ideology and the longevity of musicians’ careers in the twentieth century, it is perhaps not surprising that the professors in some of the most famous institutions (e.g. the Moscow Conservatoire, Royal College of Music, Juilliard and Curtis) still seem to produce musicians whose playing displays this trend that started approximately between the 1920s and 1950s.63

On the basis of their Bach recordings Hahn, Ehnes, Khachatryan and to a slightly lesser extent Fischer are representative of such violinists. As noted in the previous sections, Hahn and Ehnes were educated at Juilliard and Curtis where famous violin pedagogues (Ivan Galamian, Jascha Brodsky, Sally Thomas, Dorothy DeLay) of a modern “Russian-American” school ruled. It is indicative of Hahn’s style of playing that in a lead article about her that appeared in the Gramophone in 2000, Milstein, Heifetz, Kreisler and Grumiaux were named as the violinists who influenced her the most. The link between her tutelage under Brodsky and her approach to Bach is also hinted at:

He wanted me to bring in Bach every week […] You can’t get away with anything in Bach. You can’t focus on the technique and forget about the phrasing, and you can’t focus on the phrasing and forget the technique because neither will work. You also have to balance voices. It’s a challenge to phrase each voice individually, to play everything the way it should be played technically and make the multiple voices sound like one piece. It takes a lot of thought and a lot of playing to get to where you can feel comfortable with it.64

In a 2003 interview she added

Bach is the composer I’ve played the most—he’s the touchstone that keeps my playing honest […] As long as he is played with good intentions, some thought and an organised approach he will always grab people’s attention. Bach never gets old. Something about him is always identifiable.65

Julia Fischer, who started with the Suzuki method under the guidance of Helge Thelen in her native Munich, similarly looks to older generations, in particular Oistrakh and Menuhin, when asked to name her idols. She considers Sophie Mutter to be “the greatest German violinist today” and admires Oistrakh because he was

one of the most honest musicians in the world—a real medium between the composer and the listener. He was never, not in one [musical] phrase, on stage to show off, but only to be a servant to music and the composer.66

Regarding performing Bach Fischer states:

Bach has been part of my daily diet for years, and recording the Sonatas and Partitas is something I’ve long wanted to do. One of the things that I love most about Bach is that you can have absolutely your own view—there’s no unbroken performing tradition that you’re up against.67

This seems to be a view shared by the Armenian Khachatryan, another young violinist playing in a decidedly MSP (according to some reviewers “old school”) style. When asked about his view on period performance he responded:

People move with the times. In the Baroque period repertoire was played in the way that was modern at that moment. But in time new techniques and new methods have been developed, and if you continued playing Baroque instruments, you’d kind of stagnate. We should approach the pieces from our knowledge now, rather than staying at that earlier level.68

What emerges from these quotes is the impression that these violinists have made a deliberate choice regarding their MSP approach to playing Bach and that the decision has been deeply influenced by spending their formative years in musical environments where traditions of mid-twentieth-century aesthetics—including the notion of “letting the music [composer] speak for itself” and thinking of current instruments and playing modes as being all-round better than their period versions—are upheld strongly. Mullova describes these ideals succinctly when she writes,

When I was at the Conservatory in Moscow [the rules of playing Bach] were based on a widely-held approach of the time that combined a standardized beautiful sound, broad, uniform articulation, long phrasing, if possible, and continuous and regular vibrato on every single note.69

She also explains the main differences between her Bach playing then and now:

During those years [in the Moscow Conservatoire] my Sonatas and Partitas became stiff, monotonous and even more difficult to perform […] I used to play them with very little articulation, and without the distinction between strong and weak beats that is so naturally linked to bow-strokes. But most of all, I didn’t understand the harmonic relationships, which are fundamental to a feeling of freedom and involvement in the musical argument.70

In her biography she adds information about the MSP style of bowing typical throughout the second half of the twentieth century:

I was so proud that I could […] play one note, change the bow up or down on the same note and you couldn’t hear the join. That was one of the things I had to technically master very young and I was brilliant at it. But now I don’t use this technique when I play Baroque music.71

Whereas Mullova has changed her approach radically since her first solo Bach recording in 1987—due to musical encounters with HIP musicians who lured her back to the repertoire which she had abandoned out of frustration, as recounted in the quoted liner notes—it remains to be seen if Hahn and the others cited above ever will and if so, why.72

Apart from playing on modern violins with modern bows, the common characteristics of the recordings of Shumsky, Ricci, Perlman, Kremer (in 1980), Mintz, Ehnes, Hahn, Khachatryan and to a slightly lesser extent Poulet and Fischer are the predominantly literal approach to tempo (besides slowing down to mark the end of phrases), rhythm and dynamics; a tendency to use even, portato strokes; projecting longer melodic lines played on a single string as much as possible; not adding ornaments; and playing with regular accenting and an even, vibrato tone. In short, all the features that Mullova so aptly summarized in her liner notes cited above. Other violinists who seem to belong to this modernist school include Gähler, Ughi, Edinger, and to a lesser extent Buswell, Kremer (in 2005), Schmid, Szenthelyi, Schröder, and Kuijken (especially in 2001). Kremer is different in that his interpretation can be linked to his Russian schooling. For instance it is rather intense, serious and grand, a style that upholds Gringolts’ opinion that the Russians “always played everything in a romantic manner. Their […] Bach has a tendency to sound a bit on the never-ending side—a lot of melodic line, shapeless.”73 In Kremer’s second version a reviewer heard a “seeming determination to bypass his instrument in pursuit of musical truths” through the “hard hitting, raw, squeezed-out quality of many notes above the stave and loud broken chords.” The critic also noted that “[t]he utterly unprettified G minor [is] brisker and grittier than what one usually hears.”74 Nevertheless, this later recording also shows signs of more recent approaches to baroque music performance adopted in an idiosyncratic way, as I will show in chapters four and five. Similarly, Buswell and Szenthelyi attempt to invoke HIP articulation and bowing but these are usually evident only in the opening bars or phrase of a movement and not across all movements. Schmid’s version seems fairly hybrid, with emotionalized dynamics and tone but the pulse often being strong and the articulation detailed. He uses varied bow strokes.

The surprise names in the above list are Schröder and Kuijken, both of them being associated with period performance practice and both playing with period apparatus. Kuijken’s first version (recorded in 1981 and issued on compact disk in 1983) is also the most often chosen HIP-comparative recording in reviews published in the Gramophone. Nevertheless the evenness of their tempos (Schröder tends to play rather slowly, too), the fairly limited presence of metrical inflections, rhythmic freedom, and additional ornaments, together with a pervasive vibrato, long-range phrasing through dynamics, and occasionally rather sturdy, heavy bowing make their recordings sound quite similar to some of the more “stylish” MSP (alias “authentistic”) rather than to the full-blown HIP versions.75

Again, the age of the artists and the time of their formative years may provide the explanation. As stated earlier, Schröder was born in 1925 and has been associated with the early music movement since the 1960s, especially for his performances of classical string quartet music and for promoting little known seventeenth- and eighteenth-century works for violin. He once told Kjell Harman that “changing to the Baroque violin was a gradual transition, and in my case it was never complete”; it is well known that even in the early 2000s he was still playing “both the Baroque and Classical violin and occasionally an instrument set up in accordance with modern requirements, but he never uses different instruments in the same programme.”76 In my view, Schröder’s published statements regarding historically informed violin playing are much more illuminating and in line with how other period instrumentalists now perform baroque music than his own renderings.77 This echoes what Sol Babitz reported about the state of early music performance at The Hague in the mid-1970s: “They teach unequal playing to their students, but they don’t do it themselves.”78

Kuijken, although some twenty years Schröder’s junior and thus belonging to the next generation of Flemish and Dutch musicians who spearheaded period instrument performance during the 1970s, plays the pieces in a similar fashion. As I will show later, his interpretations go only a little further than Schröder’s in the direction of HIP (for details see also Table 3.2). Kuijken’s recordings with La Petite Bande display much more clearly the characteristically HIP style of closely articulated and metrically orientated playing than either of his two albums of solo Bach (1981, 2001). Perhaps he acquainted himself with the Solos too early in his violin studies to be able to fully shed ingrained readings and executions. The finding that his later recording is even less HIP-sounding than the first may indicate that as musicians age, the musical conventions and techniques ingrained during their early training could easily resurface.79

Contrary to Sigiswald Kuijken, his close contemporary Sergiu Luca (1943-2010) provided listeners with a radically different style of playing Bach’s Solos when he recorded them with a period bow and period violin in 1976. His was the first such recording yet it is rarely mentioned in the sources and was never reviewed in Gramophone.80 Although in the USA it stirred some positive reactions—for instance a reviewer voiced his astonishment at hearing the works in such a new light81—by and large later recordings tended to be compared to Kuijken’s 1981 version as if that was a yardstick for period practice.82 In many ways Luca’s version was so radical and advanced for its time that only recordings from the mid-1990s started to match it in terms of articulation, bowing, added embellishments, rhythmic flexibility and expressive freedom. His story is somewhat similar to Mullova’s conversion as related in her liner notes. They both exemplify the rare case when a musician radically changes his or her approach to a composition. The Galamian-trained Luca, who was also playing Sibelius and other late romantic concertos at the time, found inspiration in recorded performances of Gustav Leonhardt and discussions with Alan Curtis, another important harpsichordist. Together they helped him to discard tradition and allow his baroque bow to guide him in finding possible sonic equivalents of written descriptions found in eighteenth-century treatises.83

While the recordings of Schröder and Kuijken still showcase many characteristics of the authentistic-modernist MSP style typical of the mid to late twentieth century, younger players born after about 1965, demonstrate an influence of HIP. An interest in recreating eighteenth-century performing practices had started already at the beginning of the twentieth century with publications by Dolmetsch and Landowska. It gained increased momentum from the mid-1950s and eventually became a radical alternative approach and style by the 1980s. Since then it has gradually lost its controversial status. Rather, as the observations in this book also demonstrate, it is the dominant way baroque music is performed nowadays. Some of the violinists born between 1940 and 1960 in the current sample had become leading figures in propelling the HIP aesthetics to the fore (Kuijken, Luca, Wallfisch, Huggett, Beznosiuk, Holloway). This influence is clearly seen in the more lifted bowing of Lev, Mullova, Zehetmair, Schmid, Tetzlaff, Tognetti, Faust, St John, Barton Pine, Gringolts, and Ibragimova. It is also evidenced in their rhythmic and tempo flexibilities, limited use of vibrato, approach to polyphony, and delivery of multiple stops that tend to be (almost) arpeggiated, rather than played as chords. Some of them also embellish the music freely (e.g. Mullova, Tognetti, Tetzlaff, Faust, Barton Pine, Gringolts).

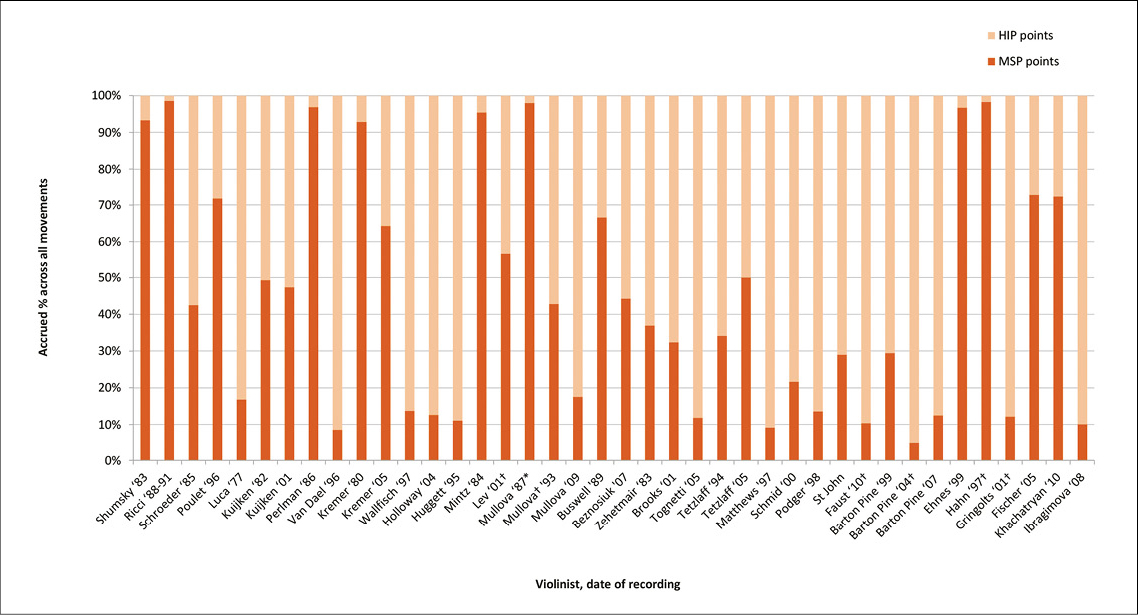

From a broad perspective I found little difference between the general interpretative vocabulary of these players and their contemporary HIP specialists playing on period instruments (Brooks, Podger, Matthews; see Figure 3.1). Short bow strokes with rapid note decay, rhythmic inflections, strong projection of pulse, closely articulated small motivic cells, over-dotting, arpeggiated multiple stops, bouncing, lively dance movements, and dynamic nuances within a basic, “average” volume can be observed in all of these recordings to a greater or lesser extent. The recently released (2008-2010), entirely HIP-sounding, lavishly ornamented performances of Faust (volume one) and, even more so, the much older Mullova are further testaments to this transformation of interpretative style within pockets of MSP. Closer inspection reveals differences in kind (e.g. vibrato or no-vibrato tone, accent rather than metric stress; short but not inflected bow stroke) as well as in degree (e.g. long-range dynamics even if motivic cells are articulated, legato / longer strokes that are nonetheless inflected and varied). These differences will be discussed in the next section.

Noting the similarities, it is intriguing to ponder why these players show such a strong influence of HIP while others of their generation (Ehnes, Hahn, Edinger, Fischer) do not, as discussed earlier. Zehetmair mentions in an interview the decisive influence of attending Harnoncourt’s classes in Salzburg and later performing with the conductor.84 Tetzlaff, Tognetti and Barton Pine are also on record acknowledging the aural appeal of HIP performances of baroque music and, in the cases of Tognetti and Barton Pine, the benefits of using a period bow.85 But perhaps it is also noteworthy that none of them studied at the Juilliard or the Curtis Institute, not even the American Barton Pine, who is based in Chicago and studied with Roland and Almita Vamos at the Oberlin Conservatory.86

Members of the Juilliard-Curtis Schools, in particular Perlman (himself a pupil of Galamian and DeLay, as mentioned before) are well known for their anti-HIP pronouncements.87 This has likely impacted on the musical horizon of their students, at least at the beginning of their careers when they recorded the Bach Solos.88 The musical-aesthetic “baggage” that the Solos seem to have accumulated since their re-introduction to the concert repertoire by Joachim in the nineteenth century is manifest even in the much more contemporary-minded Isabelle Faust’s reflection. Her goal being “to get into what the composer wants,” she worked closely with harpsichordist-fortepianist Andreas Staier, as mentioned earlier, to learn more about baroque performance practice before making the recording. Nevertheless, she admits to finding the process difficult.

[Bach is] a unique man in his time and his field […] and it’s hard to digest it all. I want to get as close to Bach as I possibly can, and yet still transform it into something that’s my own personal vision. Whether to follow rules or be flexible can be very confusing. Still, it’s been a fantastic time trying to stretch, at least a little, my approach to Bach. […] The truth is, with Bach you’re never there.89

3.4. Diversity within Trends and Global Styles

Notwithstanding the broad trends summarized so far, an examination of the details show great diversity and at times less clear-cut distinction between HIP and MSP characteristics in a given recording.90 In certain dance movements (especially the Gavotte en Rondeau of the E Major Partita and the E Major and D minor gigues) almost all violinists adopt a lively, rhythmically orientated performance that projects the pulse and articulates the harmonic-metric units clearly. The final fast movements and the E Major Preludio, on the other hand, tend to sound more MSP because of a uniformly virtuosic approach. Although the violinists may employ some accenting to underscore certain structurally, harmonically or figuratively important notes, overall they deliver these movements as virtuosic show pieces (see chapter five for a detailed discussion). The fugues and slow movements of the Sonatas are different, some tending towards MSP, others towards HIP depending on tempo choice, the over-emphasis or not of fugal subjects, and the way polyphony and multiple stops are handled. In case of the lyrical slow movements, the MSP style is reflected in a predilection for phrasing longer melody lines and building major melodic climaxes. Intensification of vibrato and long-range dynamic arches contribute to the effect.

Various authors have identified how the MSP and HIP styles differ along performance scales such as contrasting approach to phrasing, articulation, bow strokes, multiple stops, ornamentation, rhythmic flexibility, dotted rhythms, and rubato. I summarized my definition of these issues in Table 3.1.91 Nevertheless, describing the differences in kind often remains elusive and not just because of the subjective nature of perception. For instance, it is generally agreed that in baroque music it is important to articulate smaller rhythmic-melodic units that reflect the beat hierarchy of the meter as well as the harmony implied by a real or imagined bass line. But the execution remains subject to taste within the broadly established parameters. In his seminal study of Bach interpretation, John Butt quotes Leopold Mozart whose advice leaves many doors open for subjective interpretation:

One must first know how to make all variants of bowing; one must understand how to introduce weakness and strength in the right place and in the right quantity: one must learn to distinguish between the characteristics of pieces and to execute all passages according to their own particular flavour.92

Lawson and Stowell also discuss articulation and accenting at length, highlighting the importance of distinguishing between strong and weak beats (“good” and “bad” notes in Quantz’s expression) and linking it to bowing, tonguing and fingering patterns.93

The trouble is that such articulation can be achieved in a variety of ways with diverse performance features and techniques interacting in seemingly endless degrees of contribution: a bow stroke can be short and light yet not create inflections in terms of dynamic shade-nuance or rhythmic stress; harmonic-metric groups can be created by dynamic accents (such as little sforzandos or fortepianos) rather than timing or “agogic” stress (that is, slight elongation of certain notes or slight delay before sounding the note). Such playing often results in a regular accentual pattern rather than a constantly shifting, nuanced, “hierarchical” one. By the same token relatively longer, more sustained bow strokes can nevertheless sound “lifted” because of tiny swells or decays in the sound produced. Phrases articulated in small metric-harmonic groups can still be legato and project a longer line, yet be heard as completely different to a “continuous legato phrase.” This latter is achieved primarily through sustained note-lengths (bowing) and a long-range dynamic arch of gradual crescendo and increasing tension followed by decrescendo and rallentando. Furthermore, the less intense tone (lighter bow pressure, less conspicuous vibrato) and looser flow (slight metrical stresses, more decay between notes, not too slow tempos) seem to contribute to the perception that Poulet’s, Buswell’s and Fischer’s recordings are less strictly MSP in style than those of Shumsky, Perlman, Kremer (1980), Mintz, Hahn, Ehnes, or Khachatryan. But in the case of Khachatryan the major difference may be the use of dynamics that create “emotionalized” phrasing, as his bowing is not that intense or heavy even though he uses long bow strokes, often combined with sustained legato. Moreover, the agogic stresses he introduces highlight the harmony or create rhythmic inflections. There are several Audio examples in chapters four and five that will illustrate these subtle and not-so-subtle differences.

Importantly, different movements bring up different issues and possibilities that indicate performance style. In certain movements it is more the phrasing, in others more the bowing and bow pressure; elsewhere it may be the articulation or accenting that seems to determine the perceived style. To put it more accurately, any of these could be the performance feature through which the style can be best described.

Fast movements (E Major Preludio and the finales of the three sonatas) are often just accented and played rapidly with short, non-legato bows even by period specialists. At times these specialists (e.g. Podger) and certain HIP-inspired violinists (e.g. Tognetti, Mullova) relish in the resonances produced by the open gut strings. This creates a fundamentally different effect to the technical brilliance and virtuoso perpetual motion of the typical MSP style. However, to complicate things further, period specialists (e.g. Wallfisch) may also adopt this virtuosic approach as shown in chapter five.

Slow movements (e.g. the C Major Largo and A minor Andante) tend to be played legato yet articulated by several violinists (e.g. Buswell, St John, Barton Pine)—or phrased into longer units through dynamic and tempo arches even by HIP and HIP-inspired players (e.g. Kuijken, Holloway, Tetzlaff). Apart from the kinds of dynamics used, it is often the tone production—intensity of vibrato and bow pressure—that seems to create the real difference. Broader bow strokes and slower tempos may counteract the impact of articulation, especially if this calls upon accenting rather than a projection of meter or pulse. At the same time longer lines may still be heard as “hierarchical-rhetorical” if the small rhythmic values (such as in the G minor Adagio and A minor Grave) are played with some freedom: Flexibility creates a series of gestures that build up to a longer phrase.

So, even if one manages to define the meaning of descriptive categories (e.g. phrasing, articulation, etc.; see Table 3.1), the degree to which the performance features of a given interpretation fit these definitions remains subjective. The overall perceived effect depends on the dominant elements within the interaction of bowing, accenting, articulation, timing, tempo, dynamics, tone and vibrato.

With this in mind, I attempt to summarize my results. Table 3.1 lists the performance features referred to throughout the analyses and my definitions of them. Table 3.2 summarizes the tendency of selected performers to cross over to HIP or MSP styles in particular movements.94 Table 3.3 provides a more detailed overview of the extent to which HIP and MSP stylistic features are present across all the movements of the more closely studied recordings.95 It is important to reiterate, however, that styles are necessarily “fuzzy” categories; they often overlap and my discussion of the details in chapters four and five is essential to justify and unpack my judgement tabulated here. As not even movements of a similar type (e.g. fugues, slow movements, opening adagios, allemandes, gigues etc.) are necessarily delivered in a similar vein, I decided to rate each recording as a whole for each category along a ten point scale (10 = maximum) to indicate the consistency of the examined features across all movements in a given recording. These are cumulative scores calculated from rating individually each of the performance features in every movement of the selected recordings and then averaging the result of each scale to obtain the final cumulative score listed in Table 3.3. This way one can see the degree to which a particular performance feature of a given recording belongs to the MSP or the HIP category; how prominently each manifests in any of the studied albums. Shading the ratings with progressively darker colours aims to aid the visual grasping of the differences. As the categorization is based entirely on repeated listening, issues of instrumental apparatus (e.g. period bow), tuning, choice of score, and artistic intention (if known) are disregarded in this tabulation.96

Table 3.1. Definition of stylistic features as listed in column headings in Table 3.3.

|

Performance feature |

Definition |

|

|

Phrasing |

Melodic (MSP) |

Melodically orientated; long-spun; created by long-range graded dynamics (crescendo / decrescendo) and tempo rubato (accelerando-rallentando) |

|

Motivic units (HIP) |

Follows bass line / harmony and metric hierarchy; difference between strong and weak beats; delineates small motives and gestures through timing (agogic stress) and bowing inflections; constant ebb and flow of nuance |

|

|

Articulation and Accentuation |

Even, regular (MSP) |

Broad, uniform style; semi-detached or legato; all notes equally important, have equal weight; regular or fairly regular accenting; note groups delineated by accenting |

|

Grouped, metric (HIP) |

Inflected according to meter and harmony; follows metrical structure; varied length of notes; first note (or group of notes) under slur stressed / elongated; dissonances leaned-on; hierarchical accentuation (stress) aided by inflected bow strokes |

|

|

Bowing |

Even, sustained (MSP) |

Seamless legato or portato strokes; consistent bow pressure / speed; weighted / sustained bowing; little or no decay between notes; often sounding intense |

|

Uneven, inflected (HIP) |

Light or lifted strokes, often short; decay between notes; difference between up and down-bow; constantly shifting dynamic shades; rapidly swelling or receding sound |

|

|

Multiple stops |

Together (MSP) |

As efficient but weighted blocks (quasi chords), at times harshly accented or broken in 2+2 or 3+1; intense sound and bow pressure; breaking is not always ascending in direction |

|

Arpeggio (HIP) |

Lightly bowed rapid or slower arpeggiation, mostly from bottom up; light and fast bowing of complete, quasi unbroken blocks (often with reverse “hairpin swell”; quick decay) |

|

|

Ornamentation (HIP) |

Graces |

Short trills, slides, appoggiaturas, vibrato added in moderate amounts |

|

Embellished |

Melodic embellishments and copious amounts of grace notes added; alternative figurations inserted / improvised |

|

|

Improvisational |

Smaller note values played as ornamental gestures; delivery reflects the ornamented nature of the notation |

|

|

Rubato |

Tempo (MSP) |

Rubato manifest in tempo speeding-slowing to indicate phrases (usually over 4+ bars); the degree of slowing at internal cadence points is varied |

|

Rhythm |

Accented (MSP) |

Rhythmic-motivic grouping achieved mostly through (dynamic) accenting |

|

Inflected (HIP) |

Taking time and using the inflections of the bow to highlight metrically strong points and hurry weak moments thus flexing rhythm and local tempo; rubato occurs at bar (or half-bar) level; notes inégales and paired slurring |

|

|

Vibrato |

Pronounced (MSP) |

Clearly audible, possibly intense (e.g. fast, wide) and fairly continuous; heavy bow pressure creates intense sound |

|

Light (HIP) |

Used occasionally to colour or decorate notes; narrow and inconspicuous; often entirely avoided |

|

|

Dynamics |

Long-range (MSP) |

Builds longer phrases or units through large-scale crescendo-decrescendo. |

|

Local (HIP) |

Constant chiaroscuro effect through bow inflections; short / rapid swells and reverse swells; subtle / rapid variation in dynamic nuances and shades |

|

Table 3.2. Movement by movement tendency of selected violinists’ interpretative styles listed in DOB order. “H” stands for HIP, “M” stands for MSP. The selection was based on Table 3.3, to provide further information on a few “clear-cut” recordings and most of those displaying a “mixed” approach. This Table was prepared on the basis of renewed listening some 2 years after preparing data presented in Table 3.3. Styles listed in parentheses indicate that the stylistic features are not strong and that characteristics of the other style (or some idiosyncratic style) are also present.

|

Gm Sonata |

Am Sonata |

CM Sonata |

Bm Partita |

Dm Partita |

EM Partita |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Adagio |

Fuga |

Siciliana |

Presto |

Grave |

Fuga |

Andante |

Allegro |

Adagio |

Fuga |

Largo |

Allegro assai |

Allemanda |

Corrente |

Sarabande |

Tempo di Borea |

Allemanda |

Corrente |

Sarabanda |

Giga |

Preludio |

Loure |

Gavotte en Rondeau |

Menuet |

Bourée |

Gigue |

|

|

Shumsky |

(H) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Schröder |

H |

(H) |

(H) |

M |

(M) |

M |

(M) |

M |

(M) |

(M) |

M |

H |

(M) |

(H) |

H |

H |

H |

H |

(H) |

H |

H |

(M) |

(H) |

|||

|

Poulet |

(H) |

(H) |

(M) |

M |

M |

M |

M |

(H) |

(H) |

M |

M |

(H) |

M |

M |

(H) |

|||||||||||

|

Kuijken ‘81 |

H |

(H) |

M |

M |

H |

H |

(H) |

M |

(M) |

M |

M |

H |

H |

H |

H |

(H) |

H |

H |

(H) |

M |

(H) |

(M) |

(H) |

|||

|

Kuijken ‘01 |

H |

H |

H |

(M) |

M |

H |

M |

M |

(H) |

M |

(H) |

M |

H |

(M) |

(H) |

H |

H |

(M) |

H |

(H) |

M |

(M) |

(H) |

H |

(H) |

H |

|

Van Dael |

(M) |

(M) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Kremer ‘05 |

(M) |

M |

(M) |

M |

M |

M |

M |

(M/H) |

(M/H) |

M |

H |

M |

(M) |

M |

H |

(M) |

H |

(H) |

H |

(H) |

(M) |

(H) |

(H) |

H |

H |

H |

|

Mintz |