4. Analysis of Performance Features

© Dorottya Fabian, CC BY http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0064.04

Having focused on overall trends and the inter-relationship between HIP and MSP characteristics in the previous chapter, here I provide a systematically detailed account of performance features. My aims are, however, the same as throughout the book: 1) to investigate the claim that performances have become more uniform and homogeneous both technically and stylistically; 2) to examine how different performance features interact to create particular interpretations and aesthetic constructs; 3) how these relate to time and place as well as musical sensibilities and knowledge; and 4) what all this tells us about musical performance. Ultimately I aim to provide empirical evidence for the complex nature of performing western classical music and a model for an integrated analytical approach.

The recordings testify to a fascinating palette of interpretative possibilities. It is quite staggering to contemplate how Bach managed to compose such pieces that speak to us almost exactly 300 years later with such directness and wealth of potential that all violinists wish to perform and record them, one generation after another. In the previous chapter I have quoted several violinists of varied background and ilk who all discussed, explicitly or implicitly, the emotional pull and instrumental challenge of Bach’s Violin Solos. They mentioned the honesty, awe, curiosity, puzzle and bewilderment these works represent for them. So what is their answer? How do they solve the problems? How do they respond to Bach’s invitation? What conversations may we, listeners, witness between composer and performer 300 years apart? How is the age of the musician reflected in his or her dialogue with the music? Are youthful players drawn to different aspects of the music then older ones? Are cultural pre-conceptions more dominant than personal age and psychological-musical maturity? The spectrum offered by Bach from timeless contemplative music to period-bound genre pieces is wide open.

Musicians and listeners find the seemingly endless ways of engaging with the Solos unquestionably rewarding. As a listener one often has a sense that quite a few violinists must also enjoy facing the technical challenges inherent in them. Otherwise they wouldn’t be returning to the pieces and performing and recording them over and over again. The sheer sonority, physicality, virtuosity of certain movements is so imminent and the performance of them so abundantly brilliant that one is reminded of musicians confiding off-record, “Yes, wasn’t that great, playing so fast? I can do it!” –– echoing Horowitz, who, when asked once why he had played so fast, responded simply: “Because I can.” The reward is not exclusively the musician’s. Listeners are enchanted as well; otherwise the market would have long relegated the works back to the pile of forgotten music or the practice studio. I for one certainly love listening to this music and find something beautiful, interesting, or novel in most versions and even those I don’t much enjoy can envelop me in Bach’s sound world in ways that lift me into another sphere. It is therefore an exciting challenge for me to explain how they do it and why I may prefer one over another when most are truly wonderful and of exquisite standards.

I have organized my analysis along performance features, moving from the most factual towards the more subjective measures. First I look at tempo choices, vibrato and ornamentation. This is followed by the discussion of rhythm and timing which entails an analysis of playing dotted rhythms and the topic of inégalité as well as the expressive timing of notes, including tempo and rhythmic flexibility. Subsequently I discuss matters that are even harder to describe in words, such as bowing (including the playing of multiple stops), articulation, and phrasing. Wherever possible I compare performance choices to musicological opinion, as found in both historical sources and modern pronouncements. The points I make are supplemented by further observations presented in tables, graphs and transcriptions as well as descriptions of particular moments in recordings. The more detailed or specific analytical observations and descriptions appear in boxed texts shaded grey for ease of navigation.

It is a daunting task to provide an honest account when analysing forty-odd recordings of Bach’s Six Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin. Each complete set entails about two hours of music. Given my position regarding the problems of the current state of music performance studies that I outlined in chapters one and two, my conclusions cannot be based on a case study. The main challenge is, therefore, to find a balance between sampling a judiciously appropriate cross-section of movements and violinists for each performance feature under investigation without getting lost in detail. Perhaps an eclectic approach will help: At times, like in the case of tempo choice and ornamentation, I provide comprehensive coverage with numerous tabulated summaries and transcriptions. Other times, like in the case of vibrato, I illustrate my claims through measurement of specific moments in a select few movements. In both cases I aim to highlight the potential for misinterpretations and misrepresentations; how the data, masquerading as objective, can nevertheless be manipulated to support whatever argument the researcher wishes to make.

Certain performance features, like the performance of dotted rhythms or multiple stops, self-determine what excerpts I have to focus on as only certain movements feature such material. What is of special interest here is the obvious slippage that readers will notice: ostensibly about dotting or the delivery of multiple stops, the discussion will actually shift to various other performance features, namely articulation, dynamics, timing, bowing, and tempo (again)—illustrating the workings of a complex, non-linear system of interactions that give rise to musical character, the affective-aesthetic dimension of the performance. Overall, it is probably inevitable that certain movements will feature more frequently because they offer more for discussion. In particular, the E Major Partita somehow emerged as a focal point, but the two Sarabandes, the A minor Andante and the G minor Adagio and Fuga also receive much attention. At the same time, the famous Ciaccona is conspicuous for its absence. It deserves a separate study.

Right here at the start and in relation to an apparently straightforward matter, a difficulty has to be noted: it is near impossible to generalize tempo trends as each movement provides something different (Tables 4.1-4.3). Furthermore, and perhaps contrary to expectations, period specialists have slower averages than MSP players, except in the slow movements, allemandes and courantes. Therefore, the once commonly held view that performances, especially HIP versions, of baroque music have become faster as we progress through the twentieth century is questionable.1

But let us stop for a minute and take a closer look. First, how should one group violinists into MSP and HIP categories if there is such confluence between approaches as discussed in the previous chapter? Readers are invited to consult Table 4.1 to see the results of grouping violinists simply on the basis of specialist / non-specialist. Table 4.2 takes into account a larger pool of players including recordings made since the beginning of the twentieth century. The top row presents the same simple subdivision (specialist / non-specialist) while the bottom row re-configures the grouping by adding the HIP-influenced players to the specialist group and contrasts them to the “hard-core” MSP cluster. Finally, in Table 4.3 I present the average tempo values of all recorded performances selected for the present study against the pre-1977 average.

In each Table the results are slightly or strikingly different! This is extremely important to note because it highlights how easy it is to draw incorrect conclusions. Even if one is interested in overall trends only (Table 4.3), caution is warranted: only 19 out of 28 movements (68%) show a slight increase in tempo. It is noteworthy that the Fugues, the E Major Preludio, as well as the D minor Allemanda and Giga have become slower. Moreover, the size of the pool of recordings examined also has to be kept in mind. Many more recordings may exist and although I believe I have examined a fairly exhaustive portion of the most readily available versions, additional versions could change the results reported here.2 Furthermore, the perceptual difference between one or two metronome marks is unlikely to be significant, especially since these values are averages based on overall tempo calculated from duration.

However honestly one reports averages, such a presentation hides what I believe to be the case: that tempo is a personal thing. My investigations over the years indicate that there are musicians who like to play fast and there are those who prefer it slower. Alternatively, some tend to play fast movements really fast and slow movements quite languidly (e.g. Ibragimova in the current data set), while others prefer less extreme tempo choices regardless of movement type (most HIP violinists). This lesson can be drawn from the examination of pre-1980 recordings as well and seem to hold true in other repertoires too.3

Table 4.1. Summary of tempo trends 1977-2010 (For change to be noted R2 = >0.001)4

|

Performing style |

Speeding up |

Slowing down |

No change |

|

MSP (all non-specialist) |

Am Grave, Fuga CM Adagio, Allegro assai Bm Allemanda (v. slightly); Corrente Double, Borea & Double Dm Corrente, Giga EM Preludio, Loure, Bourée |

Gm Fuga, Siciliano, Presto Am Andante, Allegro CM Largo Bm Allemanda Double; Corrente, Sarabande & Double Dm Sarabanda EM Menuets |

Gm Adagio CM Fuga Dm Allemanda, Ciaccona EM Gavotte, Gigue |

|

HIP (all period specialists; Gähler not regarded as such) |

Gm Siciliano, Presto Am Fuga CM Allegro assai Bm Corrente, Borea & Double, Dm Corrente, Giga EM Preludio, Gavotte, Menuet 2 & da Capo, Gigue |

Gm Adagio, Fuga Am Grave, Andante, Allego CM Adagio Bm Allemanda & Double, Sarabande & Double Dm Allemanda, Sarabanda, Ciaccona EM Loure, Bourée |

CM Largo, Fuga Bm Corrente Double, EM Menuet 1, |

Table 4.2. Average MSP and HIP tempos across all studied recordings made since 1903 (Joachim). Violinists who were added to HIP are: Zehetmair, Tetzlaff (both), Tognetti, St John, Barton Pine, Gringolts, Mullova (1993, 2008), Faust, and Ibragimova.

|

G minor Sonata: |

|||||||

|

Adagio |

Fuga |

Siciliano |

Presto |

||||

|

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

|

25 |

22 |

66 |

72 |

26 |

25 |

69 |

76 |

|

Recalculate adding “cross-over” to HIP |

|||||||

|

25 |

21 |

69 |

72 |

27 |

24 |

74 |

75 |

|

A minor Sonata: |

||||||||

|

Grave |

Fuga |

Andante |

Allegro |

|||||

|

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

|

|

26 |

23 |

70 |

77 |

31 |

29 |

41 |

43 |

|

|

Recalculate adding “cross-over” to HIP |

||||||||

|

26 |

22 |

76 |

75 |

32 |

28 |

43 |

42 |

|

|

C Major Sonata: |

|||||||

|

Adagio |

Fuga |

Largo |

Allegro assai |

||||

|

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

|

38 |

32 |

65 |

70 |

28 |

26 |

120 |

126 |

|

Recalculate adding “cross-over” to HIP |

|||||||

|

37 |

31 |

69 |

69 |

28 |

26 |

126 |

123 |

|

B minor Partita |

|||||||||||||||

|

Allemanda |

Double |

Corrente |

Double |

Sarabande |

Double |

Borea |

Double |

||||||||

|

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

|

38 |

36 |

35 |

34 |

127 |

138 |

131 |

136 |

57 |

54 |

73 |

79 |

79 |

79 |

82 |

86 |

|

Recalculate adding “cross-over” to HIP |

|||||||||||||||

|

39 |

35 |

35 |

34 |

141 |

134 |

137 |

133 |

56 |

54 |

72 |

83 |

82 |

77 |

85 |

85 |

|

D minor Partita |

|||||||||

|

Allemanda |

Corrente |

Sarabanda |

Giga |

Ciaconna |

|||||

|

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

|

59 |

56 |

125 |

118 |

40 |

40 |

76 |

79 |

60 |

55 |

|

Recalculate HIP adding “cross-over” |

|||||||||

|

58 |

56 |

122 |

114 |

41 |

39 |

79 |

78 |

60 |

54 |

|

E Major Partita |

|||||||||||||

|

Preludio |

Loure |

Gavotte |

Menuet 1 |

Menuet 2 |

Bourée |

Gigue |

|||||||

|

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

HIP |

MSP |

|

115 |

121 |

26 |

22 |

73 |

73 |

119 |

117 |

122 |

118 |

50 |

51 |

71 |

72 |

|

Recalculate HIP to add cross-over players |

|||||||||||||

|

119 |

120 |

26 |

21 |

75 |

71 |

122 |

114 |

124 |

117 |

52 |

48 |

74 |

71 |

Table 4.3: Average tempos in recordings made pre and post 1978 (before or after Luca).

MSP and HIP versions are combined.

|

4.3a: Tempo averages in slow movements |

|||||||||

|

Gm Adagio |

Am Grave |

CM Adagio |

Gm Siciliano |

Am Andante |

CM Largo |

Dm Sarabanda |

Bm Sarabande (Double) |

EM Loure |

|

|

Pre-1980 |

20 |

21 |

31 |

23 |

28 |

24 |

39 |

55 (87) |

20 |

|

Post- 1980 |

23 |

24 |

34 |

26 |

31 |

27 |

40 |

55 (74) |

24 |

|

4.3b: Tempo averages in fugues and final allegros |

|||||||

|

Gm Fuga |

Am Fuga |

CM Fuga |

Gm Presto |

Am Allegro |

CM Allegro assai |

EM Preludio |

|

|

Pre-1978 |

72 |

77 |

69 |

73 |

42 |

121 |

121 |

|

Post-1978 |

70 |

75 |

68 |

74 |

42 |

126 |

118 |

|

4.3c: Tempo averages in other movements |

||||||

|

Bm Allemanda (Double) |

Dm Allemanda |

Bm Corrente (Double) |

Dm Corrente |

Dm Giga |

EM Gigue |

|

|

Pre-1978 |

34 (34) |

59 |

132 (130) |

112 |

79 |

70 |

|

Post-1978 |

37 (35) |

56 |

139 (137) |

122 |

78 |

73 |

|

EM Gavotte |

EM Menuet I |

EM Menuet II |

EM Bouree |

Bm Borea (Double) |

Dm Ciaconna |

|

|

Pre-1978 |

72 |

110 |

113 |

48 |

77 (87) |

55 |

|

Post-1978 |

74 |

120 |

120 |

51 |

80 (84) |

56 |

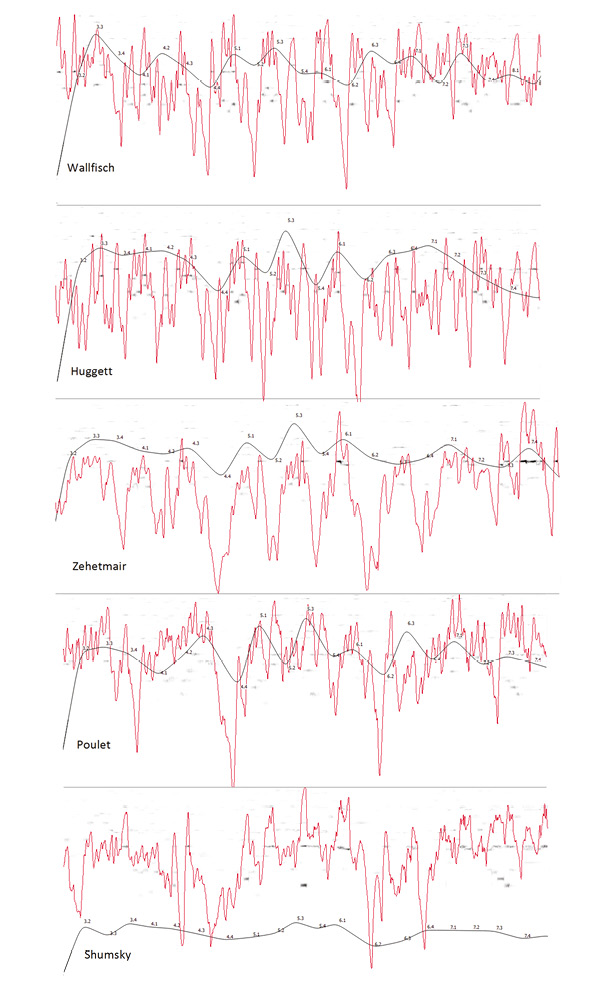

A focus on individual differences in tempo choices makes overall trends recede and diversity emerge. Some basic statistics may assist us to better understand the extent of this diversity. Standard Deviations (SD) are useful in determining global relationships. They show that there are examples in every movement of every work where the tempo difference is above two or close to three SD.5 Almost any violinist, irrespective of age, may be performing above one SD in any given movement, indicating fairly wide-spread tempo choices. This is also true when HIP and HIP-inspired players are grouped together against “hard-core” MSP players as well as when tempo choices are pooled into groups of non-specialist versus period violinists.

One overall observation that can be made reasonably safely, I believe, is that extreme tempos (i.e. SD values well above ±2) are more typical among MSP players: First and foremost Zehetmair, Tetzlaff, Kremer (in 2005) and Gringolts who all tend to play fast, but also Edinger and Gähler who tend to choose tempos at the slower end of the spectrum. In contrast, when compared to the entire pool of the studied recordings, only two HIP violinists stand out with frequently higher than ±2 SD scores: Monica Huggett and, to a lesser extent, Brian Brooks. Hers are often among the slowest whereas Brooks’ are among the faster versions. Other HIP violinists might deviate much in just one movement, like Beznosiuk who plays the C Major Allegro assai much slower than the norm (-2.04 SD). Among HIP-inspired violinist a similar example is Tognetti who takes the A minor Fuga very fast (2.84 SD) and the Double of the B minor Sarabande rather slow (-1.82 SD). Otherwise his tempos are close to the average found in recordings issued since the beginning of the twentieth century.

So what have we learned about tempo that was worth the trouble and informs the main goals and argument of this book? We gained three significant insights: First, there is great plurality in tempo choice among the examined recordings which may be overlooked when reporting only averages. This diversity seems to be relatively independent of the performer’s age and generation; it is related, rather, to individual preference. Nevertheless closer study may indicate the impact of advances in musicology and performance practice in terms of knowledge about baroque dances and determining the right tempo of these and other movements (e.g. through an understanding of the meaning of eighteenth-century time signatures and notation practices).6 Blanket statements that the performance of baroque music has become faster over time hide these important reasons and may lead to unwarranted explanations privileging broader cultural or social forces.

Second, although the average tempo of HIP-inspired players is often closer to the average of HIP violinists, the range of tempos found in the former group is nevertheless more in line with the spread found among “hard-core” MSP players (evidenced in the reduction of SD values when these players are grouped with MSP versions). This, in turn, points to the third insight, namely the greater congruence of tempo (i.e. less diversity) among HIP versions.

Period violinists tend to choose less extreme tempos in every movement. This means that the tempo contrast between faster and slower movements is also less significant in these versions, reflecting historically informed tempo choices. Current readings of historical treatises encourage moderate tempos across the board; the idea being that extreme tempos are a feature of nineteenth-century romantic conceptions of music. Perhaps this belief impacts primarily on the slower movements where musicians may feel that an overtly slow Adagio or Largo may foster a romantic emotion. The resulting faster pace of ostensibly slow movements may foster the public impression that performances have become faster. Even if this was upheld by an examination of a large corpus of recorded performance, a tendency for faster tempos in all movement types may have more to do with historical performance practice research than modernist aesthetics: playing Bach’s music fast is congruent with Philip Emmanuel Bach’s edict, reported by Forkel, that “in the execution of his own pieces [his father] generally took the time very brisk.” However, the sentence continues by stating that “besides this briskness [Bach contrived] to introduce so much variety in his performance that under his hand every piece was, as it were, like a discourse.”7 The more moderate speeds found in HIP versions often serve a more closely articulated performance that is richer in nuance and agogic-rhetorical detail.

Finally, the subjectivity of tempo is also underlined by a comparison of recommendations found in the literature and actual practice. For the Preludio of the E Major Partita, for instance, Schröder recommends a “relaxed [crotchet] = 110, approximately.”8 Most violinists tend to opt for a faster tempo with the average being around 118 (see Tables 4.2 and 4.3c). Schröder’s own version is considerably slower; in fact it is the second slowest at 99 crotchet beats per minute (Beznosiuk’s tempo is 98 bpm).

Apart from tempo and dynamics, vibrato is perhaps the most often studied parameter, especially in empirically orientated studies of vocal and violin performance.9 Being a very personal matter, a whole study could be dedicated to analysing and comparing the nature and characteristics of different violinists’ vibrato. Although of potential interest to other violinists, it is doubtful if written accounts and objective measurements provide meaningful information regarding this particular matter. Visual inspection of players in action, reflecting on resulting sound qualities and pondering their affective dimension may be more productive. Engaging with bodily, kinaesthetic actions and musical-emotional gestures are likely to be more useful than thinking in terms of vibrato width (depth) or rate.

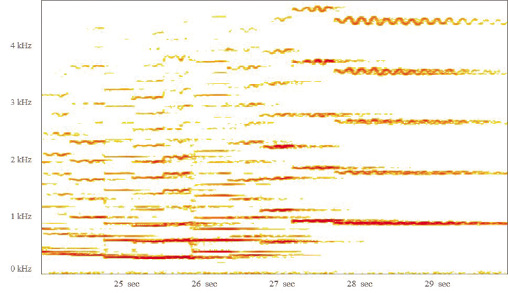

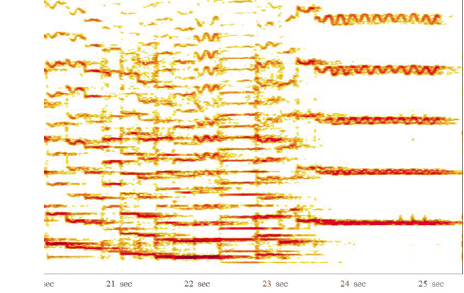

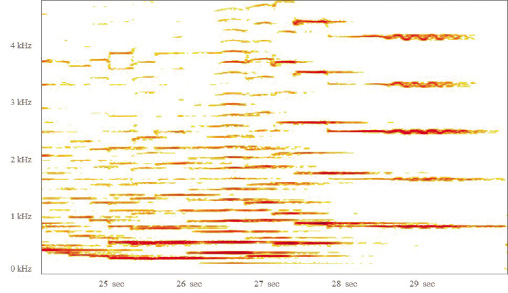

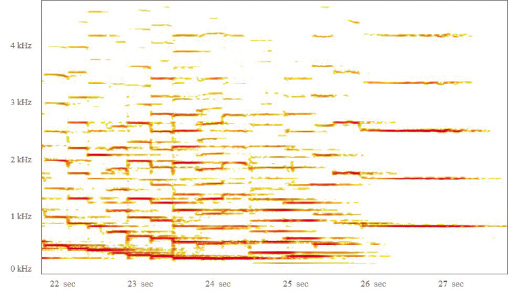

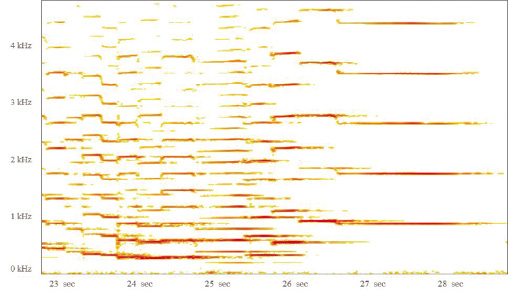

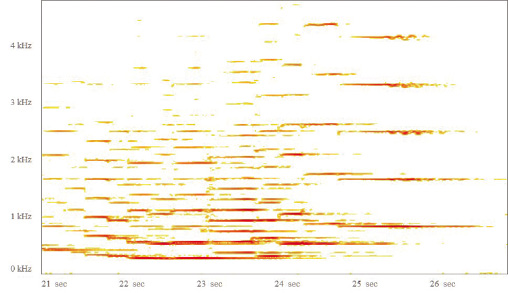

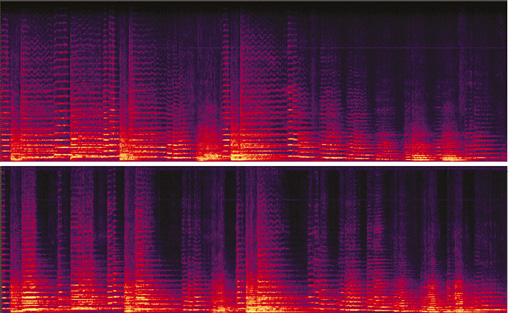

In this regard my data set shows that period and HIP-inspired players vary their vibrato more, often combining it with “hair-pin” swells (i.e. rapid crescendo on a single note) or messa-di-voce effects (i.e. adding or increasing vibrato in the middle of a rapid crescendo-decrescendo). Longer notes starting straight and being vibrated from half-way through are also quite common. Other times the vibrato might be tapered off into straight notes either in combination with a diminuendo or without. Quite clearly, for these violinists vibrato is an expressive device whereas “hard-core” MSP players use it as a part of basic tone production. Their well-regulated, near-continuous, and uniform vibrato indicates this (Figure 4.1a-c).

(a) Hahn

(b) Shumsky

(c) Podger

(d) Tognetti

(e) Ibragimova

(f) Mullova 2008

Figure 4.1a-f. Spectrograms of bars 5-6 of the D minor Sarabanda performed by (a) Hahn, (b) Shumsky, (c) Podger, (d) Tognetti, (e) Ibragimova and (f) Mullova in 2008. [Spectrogram parameters: High band Hz: 4800; Window size / Display width: 6 sec; Colour Spectrum Level Minimum: -80dB; Frequency resolution: 12.5 Hz.]

Exceptions among MSP players include Buswell. He plays many notes non-vibrato, using it instead to intensify certain longer notes, such as melodic high-points. Mullova is an interesting case as her vibrato often starts from below; in other words with a downward fluctuation of pitch (especially in 2008). In her later recordings she limits vibrato to function only as decoration, often simply a fast single quiver on a short or long note. On the basis of visually inspecting the spectrograms of her recordings I believe that it might be more bow (and / or finger) pressure fluctuation that contributes to a vibrato effect rather than change in the width of the pitch’s frequency range achieved through finger or wrist movements. Her practice of lifted bowing (quick decay) allows more room for changes in dynamics (intensity of sound level) than for vibrato.

Such a conflation of bowing and vibrato underscores the multiplicity of elements contributing to the acoustic-aesthetic stimulus we listeners perceive. Tonal colouring enriches the expressive content musical moments communicate. The greater the blend of elements from bowing, phrasing, timing, dynamics, tone colour, harmony and melody, the stronger the “Gestalt” experience: we are less inclined to say “oh, did you hear that vibrato?” or “what exquisite bowing!” and more inclined to respond globally: “ah, that was beautiful!” When one or another performance element comes to the fore our analytical mind may interfere with our holistic perception. We may relish the fact that we can pick out the cause of an effect, “ahah, she used vibrato here to highlight that note”; or “gosh, that was a wide vibrato!” But if such analytical recognition happens too often, the overall verdict may be that the performance is “idiosyncratic” or “mannered.”10 So it is really doubtful what purpose the attention to measuring vibrato (or indeed looking at performance features in an itemized fashion as I do here in this chapter) serves.

Furthermore, quantitative results are also silent about additional characteristics of approaches to vibrato use. For instance, quite a few violinists reduce their vibrato during repeats (e.g. Buswell, Huggett, St John, Mullova in 1993). Fischer is the only player who vibrates more notes in repeats but the depth is extremely narrow, making the vibrato sound more like a fast, enhancing quiver or extra vibration. Nevertheless, for those who are interested in quantitative measures I offer Table 4.4 and a brief commentary on the four overarching information that can be deduced from the data: 1) a steep decline in use of vibrato since around 1995; 2) a fairly standard vibrato rate; 3) a narrower vibrato depth among HIP and younger players; and 4) a lack of noteworthy change in vibrato style in subsequent recordings of the same violinist.11

Table 4.4. Vibrato rate, width (depth) and frequency of use measured on selected notes in different movements and averaged across each selected violinist. (Rate is expressed in cycles per second (cps); Width in semitones (sT). Frequency refers to occurrence of vibrato on the selected pitches). Standard Deviation (SD) indicates the evenness of each player’s vibrato (the smaller the number, the more regular the vibrato).

|

Performer, date |

Rate ( in cps) (SD) |

Width (in sT) (SD) |

Frequency of use |

|

Barton-Pine 1999 |

6. (SD: 0.9) |

0.21 (SD: 0.12) |

62% |

|

Barton-Pine 2004 |

nil |

||

|

Barton-Pine 2007 |

6.1 (SD: 0.9) |

0.12 (SD: 0.03) |

14% |

|

Besnosiuk 2007 (HIP) |

Very little |

not measurable |

<5% |

|

Brooks 2001 |

6.9 (SD: 1.08) |

0.12 (SD: 0.03) |

67%† |

|

Buswell 1987 |

6.5 (SD:0.08) |

0.19 (SD: 0.08) |

89% |

|

Ehnes 1999 |

6.3 (SD:0.6) |

0.2 (SD: 0.05) |

100% |

|

Faust 2010 |

Fast quivers |

<0.1 |

<1% |

|

Fischer 2005 |

6.4 (SD: 0.5) |

0.14 (SD: 0.04) |

50% |

|

Gähler 1998 |

6.3 (SD:0.37) |

0.15 (SD: 0.06) |

>60%* |

|

Gringolts 2001 |

6.9 (SD:0.28) |

0.16 (SD: 0.04) |

<3% |

|

Hahn 1999 |

6.6 (SD: 0.3) |

0.23 (SD: 0.1) |

100% |

|

Holloway 2006 (HIP) |

6 (SD: 0.5) |

0.17 (SD: 0.04) |

39% |

|

Huggett 1995 (HIP) |

5.8 (SD: 0.5) |

0.12 (SD: 0.06) |

46.3% |

|

Ibragimova 2009 |

Nil to measure |

nil |

0% |

Table 4.4., cont. Vibrato rate, width (depth) and frequency of use measured on selected notes in different movements and averaged across each selected violinist. (Rate is expressed in cycles per second (cps); Width in semitones (sT). Frequency refers to occurrence of vibrato on the selected pitches). Standard Deviation (SD) indicates the evenness of each player’s vibrato (the smaller the number, the more regular the vibrato).

|

Performer, date |

Rate ( in cps) (SD) |

Width (in sT) (SD) |

Frequency of use |

|

Khachatryan 2009 |

6.8 (SD: 0.6) |

0.17 (SD:0.05) |

89-94% |

|

Kremer 1980 |

6.3 (SD: 0.36) |

0.26 (SD: 0.07) |

91% |

|

Kremer 2005 |

6.2 (SD: 0.8) |

0.2 (SD: 0.15) |

44% |

|

Kuijken 1983 (HIP) |

5.9 (SD: 0.6) |

0.15 (SD: 0.07) |

63.3% |

|

Kuijken 2001 (HIP) |

5.9 (SD: 0.8) |

0.16 (SD: 0.9) |

60% |

|

Lev 2001 |

6.8 (SD: 0.29) |

0.12 (SD: 0.04) |

61% |

|

Luca 1977 (HIP) |

6.7 (SD: 0.1) |

0.14 (SD: 0.08) |

39.5% |

|

Matthews 1997 |

Rarely measurable; end of trills |

<1% |

|

|

Mintz 1984 |

5.9 (SD: 0.4) |

0.3 (SD: 0.04) |

90% |

|

Mullova 1993 |

6.8 (SD: 0.5) |

0.16 (SD: 0.06) |

44% |

|

Mullova 2008 |

6.8 (SD: 0.26) |

0.12 (SD: 0.03) |

11% |

|

Perlman 1987 |

6.6 (SD: 1.7) |

0.33 (SD: 0.15) |

76% |

|

Podger 1999 (HIP) |

6 (SD: 0.7) |

0.14 (SD: 0.09) |

27% |

|

Poulet 1996 |

6.2 (SD: 0.3) |

0.19 (SD: 0.06) |

72% |

|

Ricci 1981 |

6.0 (SD: 0.5) |

0.3 (SD: 0.17) |

76% |

|

Schröder 1985 (HIP) |

6.5 (SD: 0.6) |

0.15 (SD: 0.06) |

55% |

|

Shumsky 1983 |

6.4 (SD: 0.27) |

0.21 (SD: 0.05) |

100% |

|

St John 2007 |

6.7 (SD: 0.6) |

0.23 (SD:0.02) |

22% |

|

Szenthelyi 2002 |

6.4 (SD: 0.28) |

0.3 (SD: 0.1) |

82% |

|

Tetzlaff 1994 |

6.2 (SD: 1.1) |

0.16 (SD: 0.12) |

73% |

|

Tetzlaff 2005 |

6.5 (SD: 0.43) |

0.21 (SD: 0.48) |

91% |

|

Tognetti 2005 |

5.9 (SD: 0.3) |

0.1 (SD: 0.03) |

39% |

|

Ughi 1991 |

(quite fast) |

Not wide |

100% |

|

Van Dael 1996 (HIP) |

6.3 (SD: 0.8) |

0.13 (SD: 0.04) |

17% |

|

Wallfisch 1997 (HIP) |

5.8 (SD: 0.5) |

0.06 (SD: 0.14) |

45.5% |

|

Zehetmair 1983 |

4.8 (SD: 0.5) |

0.44 (SD: 0.16) |

14% |

† Brooks’ vibrato is often very fast and extremely narrow; hard to measure at all let alone accurately. Therefore the frequency percent is an estimate based on where rate could be measured but width not and where width was measurable but not the rate (signal showing a thick line with fluctuating intensity).

* Gähler’s vibrato is basically continuous but when playing full chords it is not easily executed or measured. Measurements were possible for more than 60% of the selected notes. His vibrato tends to be slow but not too wide except on single longer notes. On these occasions it becomes faster.

First, the steep decline in the use of vibrato since around 1995 is also indicated by the considerable drop in vibrato use in subsequent recordings of the same violinist (see Kremer 91% to 45.3%, Barton Pine 62% to 14%). The exceptions are Tetzlaff, who vibrated more frequently in 2005 and Kuijken, whose approach remained steady, around 60%, the highest among HIP versions.

Second, according to various researchers, a well-regulated vibrato has around six to six-and-a-half cycles per second (cps).12 Table 4.4 shows most violinists’ vibrato rate to hover around this value. The vibrato speed of HIP players is slightly slower (except for Brooks). I believe this slower rate to be related to the idea of vibrato being an ornament because a slower vibrato tends to be more audible and to sound more like an expressive decoration or a change in tone colour. A fast vibrato sounds more like a quiver, at times a sign of tension, although it could also tend towards a shake or trill.

Third, vibrato depth (or width) is shallower in HIP (up to 0.15 of a semitone [sT]) than in MSP versions (up to around 0.3 sT). This may also be related to the aim of avoiding vibrato altogether: In a stream of straight notes a very shallow vibrato may create enough tonal nuances to signify certain musical moments.

Fourth, multiple recordings of violinists show no substantial change in their vibrato style. One may speculate that no change in vibrato width and rate in these multiple versions is evidence that the technical delivery of vibrato is a personal signature and when players control it unconsciously it reflects their ingrained technical style. Of course at their level of professionalism it is perfectly within their conscious control to vary vibrato for expressive effect—or to eliminate its use entirely.

Table 4.4 also provides information about variety of vibrato. This can be deduced from the SD values. Standard Deviation values indicate the variability in the measurement of each player’s vibrato. According to this, the depth varies much less than the rate. Brooks, Perlman and Tetzlaff in 1994 have the least regular vibrato rate, having greater than 1 SD. The results for Zehetmair’s vibrato are also worth pointing out: they are extreme and indicate one aspect of his highly idiosyncratic style. He used vibrato infrequently and also varied it quite a bit. At significant high notes it tended to be wide and slow—very noticeable, indeed.

Finally it is worth picking out some violinists from the roster for individual attention. This may help to unpack the interaction of vibrato with other performance features or to explain seeming anomalies in Table 4.4.

Looking at players with narrow vibrato width, Kachatryan should be mentioned first. When he is playing softly, it becomes almost impossible to measure due to lack of visible signals. Hence the range of percentage for him in Table 4.4: the lower number excludes notes where only rate could be measured. Brooks’ vibrato is also often extremely narrow and quite fast, making accurate measurements difficult. Therefore the percentage of frequency of use is an estimate only; a combination of where rate could be measured but depth not (i.e. signal showing a thick line with fluctuating intensity) and where depth was measurable but not the rate. Ehnes’ vibrato is audible primarily because it tends to be rather slow. At the same time it is quite narrow (and therefore hard to measure) and it tapers off on longer notes. Lev’s vibrato seems often to be a result of bow pressure fluctuation, a consequence of strong down-bows followed by quick decay. At other times it might be a short quiver creating emphasis. Barton Pine has no measurable vibrato in 2004 (only the D minor Sarabanda was available). Bowing (e.g. swell and reverse swell / down-bow) shows some fluctuation but as it is not vibrato but an effect of bowing, it is rather pointless to measure.

In Gringolts’ A minor Andante there is nothing measurable. What one may hear as vibrato seems to be an effect of his bowing (pressure, speed) that creates a kind of “gliding,” rapidly fluctuating sound. However, it is hardly possible to call that vibrato: not a single vibrato curve can be seen in the spectrogram, just some unsteadiness in the intensity of the signal. In his interpretation of the E Major Loure, quivers (or just a single quiver) are more audible when “leaning-on” with bowing (down-bows). Proper vibrato curves are still hard to detect and often turn out to be trills. The two notes where vibrato could be measured in the Loure were the B crotchet on the down-beat of bar 8 and the A crotchet on the forth beat of the same bar. The vibrato rate of the two notes was 6.4 and 7.1 cps, respectively, while the depth measures were 0.13 and 0.19 sT.

Among older MSP players, who are inclined to regard vibrato as integral to tone production, Poulet’s vibrato is quite slow but not too wide. It becomes more prominent on melodically or harmonically important notes. Shumsky’s vibrato is wider than the younger players’ and at times slower as well. Gähler’s vibrato is basically continuous but when playing full chords with his curved “Bach-bow,” it is not easily executed creating blurred signals. Measurements were possible for more than 60% of the selected notes. His vibrato tends to be slow but not too wide except on single longer notes. On these occasions it was faster or sped up after a slower beginning.

All this speaks particularly to two of my main aims in this book. Firstly, it shows that even vibrato has again become less homogeneous during the past thirty years; it has started to sound similarly varied to what one hears on early twentieth-century recordings. This is true on several levels: at the level of contrasting MSP and HIP approaches to vibrato along a continuum of frequency of use and tone production, and at the level of varying vibrato “style” or quality. Secondly, it shows the interaction of performance elements contributing to tone production and musical expressivity.

Diversity in vibrato is interesting first and foremost for how it is varied, not whether it is used at all. It is fascinating to realize that vibrato has again become part of expression rather than tone production. And not just in this special repertoire as might be objected. I have studied many recordings of Beethoven and Brahms violin sonatas as well, for instance, and can confirm that variation in vibrato for expressive tonal effects is on the rise among players as different as Anne-Sophie Mutter, Viktoria Mullova, Rachel Barton Pine, Isabelle Faust or Daniel Sepec.13

Why is variety in vibrato an important finding? Because a fundamental piece of evidence that supports the criticism of uniformity in performance is uniformity of sound—homogeneous, undifferentiated tone achieved through seamless bowing of equal pressure throughout and perfectly controlled, even vibrato, as exemplified by Hilary Hahn’s playing, for instance. Joseph Szigeti complained already in the 1950s that players have lost the “speaking quality” of their bowing, that too much emphasis has been put on right hand technique and power of tone. He pointed out that without varied bow strokes the musical characters are ironed-out.14 Alternatively people blamed the recording industry and oversized concert halls for needing big sounds that carry into the farthest corners and balance well with the might of large orchestras. We have seen, in chapter three, how famous teachers contributed to this development and Table 4.4 clearly shows that violinists of the Juilliard / Curtis School continue this tradition. The continuous vibrato, allegedly developed to counteract the depersonalized nature of sound recordings,15 became a vehicle for an idealized aesthetic of perfect control manifest in consistent tone. Perhaps it is a saturated market calling on musicians to differentiate themselves, perhaps it is the opportunity offered by smaller independent record labels, perhaps it is the musicians’ need to do something new, perhaps it is our pluralistic time that allows musicians to interpret, to play and not be bound by rules and the tyranny of perfection that resulted in the return of varied vibrato. Most likely it is a combination of all this that calls on violinists to question the nature of perfection by creating performances full of tonal shades, uneven bow strokes and variously vibrated notes.

Much has been written about ornamentation in baroque music and I focus only on those matters that relate to the broader concerns of this book. Pertinent among these is the aesthetic effect achieved. Therefore, first I will discuss some of the scholarly opinions that highlight essential aesthetic problems and then will aim to analyze the recordings in this context.

Problems of Aesthetics and Notation Practices

One of the most difficult problems of ornamentation and improvisation in baroque music is deciding not so much how but when and how much to do it.16 There are countless charts providing solutions to symbols of graces and many examples of figurative embellishments.17 However, in the end all sources, modern and historical alike, reiterate that it is a matter of good taste to know when and what, or how much, is appropriate. What’s more, it is obvious that the sensibility of this infamous bon goût changes with the passing of generations.

Take Pier Francesco Tosi (1653-1732), for instance. Writing in his old age, when the much younger Farinelli (alias Carlo Maria Broschi, 1705-1782) and other popular singers are admired for their ability to lavish simply sketched melodies with passagi and roulades, he decries them as “modernists” who are lacking in true taste, scorning them for “their offences against the true art of singing.”18 At the same time, Johann-Joachim Quantz (1697-1773), a contemporary of Farinelli, enthusiastically praises the 1720s-30s when, in his view, the art of singing reached its greatest height.19 However, reading both Tosi and Quantz further, one encounters statements from the former: “whoever cannot vary and thereby improve what he has sung before is no great luminary”;20 and from the latter: “all-too-rich diminutions will deprive the melody of its capacity to ‘move the heart.’”21 So how do we know what is “all-too-rich” and what may be an “improvement” on what has already been sung?

Among modern writers on the matter Neumann provides an open-ended basic framework when he distinguishes between first- and second-degree ornamentation:

As a rule of thumb […] an adagio is skeletal if it contains no, or only very few, notes smaller than eighths; it has first-degree diminutions if it contains many sixteenth notes; it has second-degree diminutions if it contains a wealth of thirty-second notes or smaller values. The skeletal types were always in need of embellishment; the first-degree types may fulfill stylistic requirements in the lower range […] further ornamental additions are optional and often desirable on repeats; the second-degree designs were in no need of further enrichment but on repeat could be somewhat varied.22

Bach’s notation practices tend to fall into the third category (i.e. second-degree design). Deciding on ornamentation in his music is often complicated as he was in the habit of notating out diminutions, even graces that others indicated with symbols (see fn. 17 above). John Butt considers it likely that this practice of Bach, that he notates everything that is to be played, might be the key reason for the lasting appeal and value of his music.23 Bach was chastised for it in his own time by Johann Adolf Scheibe (1708-1776) and defended by Johann Abraham Birnbaum (1702-1748) in a public debate that seems to rehearse the familiar problem of taste, the composer’s “honour” and the performer’s “prerogative” that are voiced also in other historical sources.24

Scheibe (1737) reproached Bach for writing out all the melodic embellishments (figures or divisions) and for not leaving space for the performer’s improvisation: “Every ornament, every little grace, and everything that one thinks of as belonging to the method of playing, he expresses completely in notes.”25 In Bach’s defense, Birnbaum observed that it was a fortunate situation when a score where embellishments are added by the composer was available, for he knew best “where it might serve as a true ornament and particular emphasis of the main melody.” Birnbaum considered it “a necessary measure of prudence on the part of the composer” to write out “every ornament ... that belongs to the method of playing.” He asserted that improvised embellishments “can please the ear only if it is applied in the right places” but “offend the ear and spoil the principal melody if the performer employs [embellishments] at the wrong spot.” To avoid attributing errors of melody and harmony to the composer, Birnbaum posited the right of “every composer […] to […] [prescribe] a correct method according to his intentions, and thus to watch over the preservation of his own honor.”26

The mid-twentieth-century Bach scholar and conductor Arthur Mendel (1905-1979) pointed out the crucial lesson in this debate, which turns the attention away from petty point scoring and the matter of taste toward the fundamental issue in twentieth-century Bach performance and playing baroque music in general. He suggested that Scheibe’s objection was perhaps due to the difficult rhythmic patterns that arise from written-out turns and other embellishments:

Because of the essentially improvisatory character of trills, appoggiaturas, and other ornaments, the attempt to write out just what metric value each tone is to have can never be successful. I think this may be partly what Scheibe meant in criticizing Bach for writing out so much [...] The attempt to pin down the rhythm of living music at all in the crudely simple arithmetical ratios of notated meter is [hardly ...] possible.27

In their concern for the text, the notated score of a composition, and its technically correct rendering, modern musicians are easily misled by the visual representation of music. Notes of equal significance in print will likely be played with equal importance. Recognizing the ornamental nature of Bach’s notation practices is a first step toward rendering rhythmic patterns and melodic groups with some freedom.

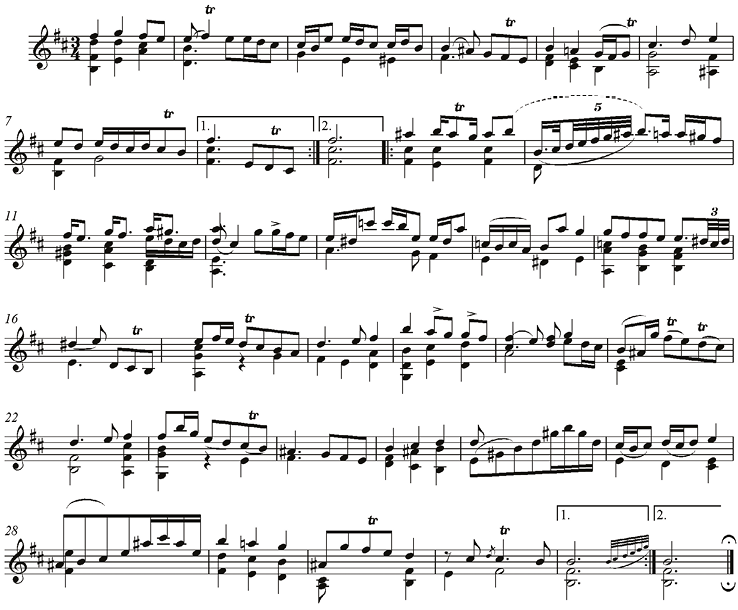

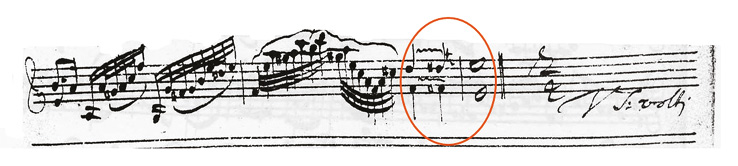

The G minor Adagio is a good example of this problem. The opening bars of it would likely have been notated as in the top system of Figure 4.2 by most other baroque composers, especially those of the Italian tradition.28 Instead, Bach wrote out a possible embellished performance version. Playing the notes rhythmically accurately is therefore a mistake, because spontaneous ornamentation is never rhythmically stable or exact. As Lester points out, “Thinking of the Adagio as a prelude built upon standard thoroughbass patterns can [help] the melody [be] heard not so much as a series of fixed gestures, but rather as a continuously unfolding rhapsodic improvisation over a supporting bass.”29

Figure 4.2. Bars 1-2 of Bach’s G minor Adagio for solo violin (BWV 1001). The top system is a hypothetical version that emulates the much sparser notation habits of Italian composers such as Corelli, who tended to prescribe only basic melodic pitches that the musicians were supposed to embellish during performance. The middle stave is Bach’s notation, reflecting one possible way of ornamenting the passage. His original slurs indicate ornamental groups to be performed as one musical gesture. The lowest stave shows the “standard thoroughbass” that players might conceptualize for a “rhapsodic improvisation” to unfold.

4.1. Literal versus ornamental delivery of small rhythmic values in J. S. Bach, G minor Sonata BWV 1001, Adagio, extract: bars 1-2. Six versions: Monica Huggett © Virgin Veritas, Oscar Shumsky © Musical Heritage Society, Shlomo Mintz © Deutsche Grammophone, Julia Fischer © PentaTone Classics, Sergey Khachatryan © Naïve, Alina Ibragimova © Hyperion. Duration: 2.08. See also Audio examples 5.22, 5.23 and 5.24.

To listen to this extract online follow this link: http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0064.07

Tracing flexibility (or lack thereof) in performances of the G minor Adagio throughout the course of the work’s recorded history provides an excellent window into the trajectory of Bach performance practice since the beginning of the twentieth century.30 Among the recordings under examination here, Huggett, Wallfisch, Barton Pine, Ibragimova, Mullova and others, including Schröder and Buswell, play with enough flexibility to create the impression of free ornamentation. Shumsky, Fischer, Khachatryan, Ehnes, Mintz, among others, provide much more literal and measured readings (Audio example 4.1 at Figure 4.2).

The difference in performance style also impacts on the perceived affective dimension of the piece. This movement is clearly melancholic-meditative since it contains many dissonances, displays descending melodic tendencies, and is in the minor mode;31 a soliloquy that perhaps sounds less sad and personal when played in a measured style and sounds more as a self-reflective monologue passing through passionate outbursts and calming-tenderness when performed with fluid, rhapsodic freedom. Pondering the perceived affective dimensions of various versions is fascinating, especially since fairly small variations in particular details can lead to quite diverse overall impression. I will come back to this in the next chapter where I consider individual differences and affective response.

Given Bach’s notation practices, it might seem enough for the contemporary musician and listener to adopt a quasi-improvisatory style of playing when faced with performing Bach’s written-out ornaments. However, there are also movements that are less clearly decorated, where the quantity and place of additional ornaments and embellishments are worth contemplating. Although Bach habitually wrote out more figuration than his contemporaries, including elaborate ornamental figures as we have just seen, as well as appoggiaturas and terminations of trills that need to be recognized and performed as such, he indicated graces such as trills, slides, and mordents relatively sparingly. In addition, surviving successive versions of pieces, for instance the Inventions and Sinfonias (BWV 772–801) or the reworking for lute of the E Major Partita for Solo Violin (BWV 1006a), show different degrees of ornamentation. According to contemporary records, Bach was also in the habit of improvising richly textured, polyphonic continuo parts instead of the apparently more common simple chordal style. So what is a performer supposed to do? What might be within “good taste”?

There seems to be “a fairly broad range of legitimately possible levels of ornamentation, extending from a desirable minimum to a saturation point.”32 Moreover, “informed” subjectivity is encouraged by Neumann when he recommends Georg Friedrich Telemann’s published embellishments to his Sonate metodiche for violin or flute (Hamburg: [n.p.], 1728) as “helpful […] to late Baroque diminution practice because they strike a happy balance between austerity and luxuriance.”33

As always, performances are judged ultimately for their expressive affect and, in this regard, Quantz’s reasons for his admiration of “Italian singing style [and] lavishly elaborated Italian arias” are perhaps the most useful guide. His praise is earned because they are profound and artful; they move and astonish, engage the musical intelligence, are rich in taste and rendition, and transport the listener pleasantly from one emotion to another.34 In the footsteps of Quantz we should feel liberated to speak of the subjective, to use metaphor, to allow our holistic and affective mind-body to sort out what “works.” Such a reporting goes against my scientifically trained brain but feels valid to my listening, music-loving persona. I aim to balance the two by recognizing that both the performer and the analyst are confronted with a multitude of musical puzzles and possibilities with no hard and fast rules, but only “sufficiently developed taste,” culturally and historically conditioned expectations, and subjective boundaries regarding what feels appropriate as aids and foundations for aesthetic judgment. Importantly, I hope to have demonstrated that none of this ought to be a moral issue, not even in the music of the “great” Johann Sebastian Bach. Performance is not about absolutes but about conviction and affect, nowhere more so than in relation to ornamentation and embellishment.

The Performance of Embellishments

So what do we find in the recordings? In this repertoire the past thirty years seem to demonstrate that we have reached a stage where quite a few violinists dare ornament several movements quite lavishly, especially in most recent times. However, ornamentation happens less in the slow movements that are already embellished by Bach and more in the lighter dance movements. Furthermore, adding short graces and altering articulation, rhythm or dynamics, or, as we have seen, using vibrato to ornament special notes are more common than melodic embellishment.35 Nevertheless, there are also significant instances of sumptuous embellishing, even complete rewriting of bars and passages, and even in movements containing written-out figuration.

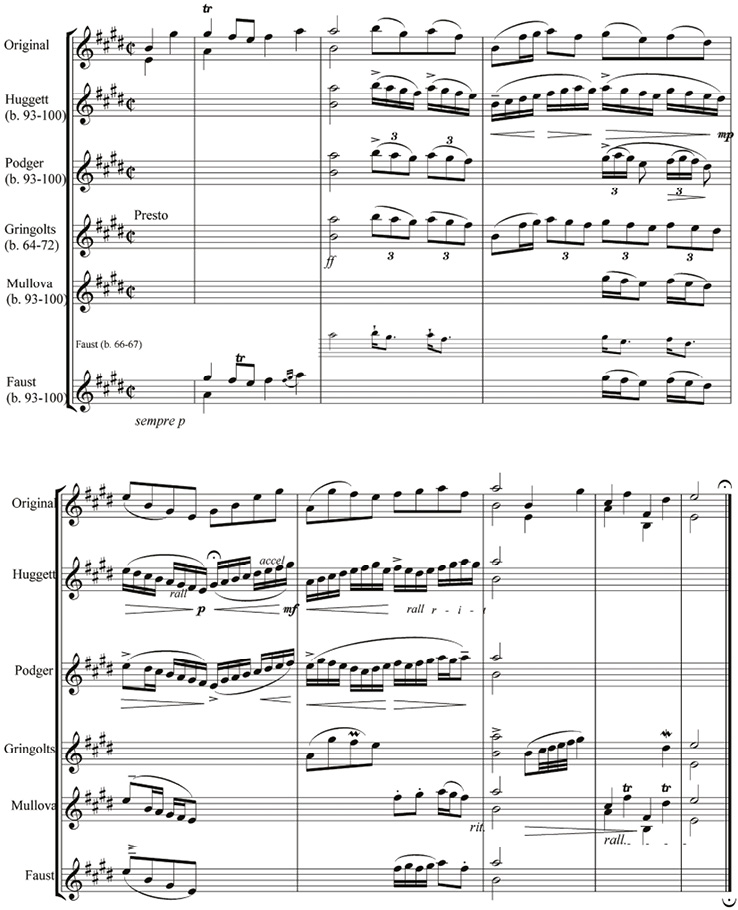

Again we can note the difference between what the factual information tells us and what it hides. Table 4.5 lists the most ornamented movements and the violinists involved in order of the amount of ornamentation and / or embellishment observed. It is immediately apparent that the E Major Partita features prominently and, although slow movements are represented, none of the opening adagios of the sonatas is listed (to my knowledge only Montanari adds embellishments in the G minor Adagio and this 2013 recording was made after the designated three decades of 1980-2010 under discussion here). The table also makes it apparent that ornamentation is more frequently practiced by non-specialist than HIP violinists—only Luca, Huggett, van Dael, Wallfisch, Beznosiuk and Podger represent period instrumentalists, and only Luca’s name can be seen in the columns of the slow movements. Huggett adds beautifully haunting ornaments in the D minor Sarabanda but only during the repeat of the first half (bb.1-8) and in none of the other slow movements. It is also obvious from Table 4.5 that less than one third of the forty-odd violinists studied here add ornaments and only four (Luca, Mullova, Gringolts, and Faust) to a significant extent.

Table 4.5. Most embellished movements listed in order of amount of ornamentation. The named violinists add graces and embellishments extensively, decreasingly so as moving downward in each column. Others not listed here may also add a few graces here and there.

|

EM Gavotte |

EM Menuet |

EM Loure |

Bm Sarabande |

Am Andante |

Dm Sarabanda |

|

Huggett Podger Gingolts Mullova ‘08 Faust Tognetti Beznosiuk (Matthews) (Barton Pine) (van Dael) |

Faust Mullova ‘08 Gringolts Podger Wallfisch (Tognetti) |

Gringolts Faust Mullova ‘08 Luca van Dael Wallfisch Tognetti |

Gringolts Mullova ‘92 Mullova ‘08 Luca Faust Tetzlaff 2005 (Tognetti) (Kuijken) |

Gringolts Luca Tognetti Faust |

Faust Beznosiuk Huggett (1st half) (Barton Pine 2004) (Luca) |

What we cannot see from the table is the fact that the solutions of different violinists tend to vary widely in terms of type, place and frequency of added ornaments. I discussed more of this fascinating detail in a separate paper so here I only provide some additional observations, transcriptions and Audio examples.36 My current concern is rather to explore further the meaning and affective dimensions of ornamentation and embellishment.

In the slow movements (including the E Major Loure) what I find most important to highlight is the sharp contrast between Gringolts’s almost constant ornamentation and the more selectively added melodic passing notes and occasional flourishes or compound graces in Luca’s, Tetzlaff’s, Tognetti’s, Mullova’s and Faust’s or Beznosiuk’s versions. Kuijken tends to add only trills and approggiaturas. Furthermore, compared to Gringolts, these versions maintain a greater sense of rhythm and basic pulse and they also manage to keep the original melody intact.

In the A minor Andante, for instance, Gringolts bows very smoothly and swiftly, adding many twists and turns throughout. In contrast Luca’s embellishments are more selective, filling in or varying certain well-recognizable melodic motives in a pattern-like manner, keeping with the movement’s steady style of harmony and rhythm (Audio examples 4.2).

4.2. Ornamentation in J. S. Bach, A minor Sonata BWV 1003, Andante, extract: repeat of bars 1-11. Two versions: Sergiu Luca © Nonesuch, Ilya Gringolts © Deutsche Grammophon. Duration: 1.07.

To listen to this extract online follow this link: http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0064.08

The difference in affect is palpable: the Andante in Luca’s hand is a simple, direct, beautifully balanced little aria, an intimate song. In Gringolts’ interpretation it sounds more like an over-cultivated flower that delights with its intricacies and quasi magical unfolding (as if on a sped-up film showing the opening of a bud) but somehow leaves the heart detached; calling forth a captivated outside observer rather than an intent listener enchanted by the serene beauty of the song. Overall I find Gringolts’ embellishments and bowing curiously unusual and intriguing. It surprises me that my students are quite categorically dismissive of this performance. I have always found them to prefer Luca’s version and in the ensuing discussion I will eventually offer reasons for this fairly constant aesthetic response.

Interestingly, while reviewers of Gringolts’ disk comment on its “swaggering individuality and abundant fantasy”37 and find that his “readings are remarkably elastic, and many figures are played with capricious fleetness,”38 they hardly mention ornamentation.39 Most surprisingly Robert Maxham opines that “movements like the Second Sonata’s Andante ([…]) come closer to the interpretive canon,” meaning, I guess, the playing of violinists like Szigeti and Milstein! Apart from the aural experience, my transcription of Gringolts’ lavishly embellished performance of the Andante’s second half shows that this can hardly be the case (Figure 4.3).

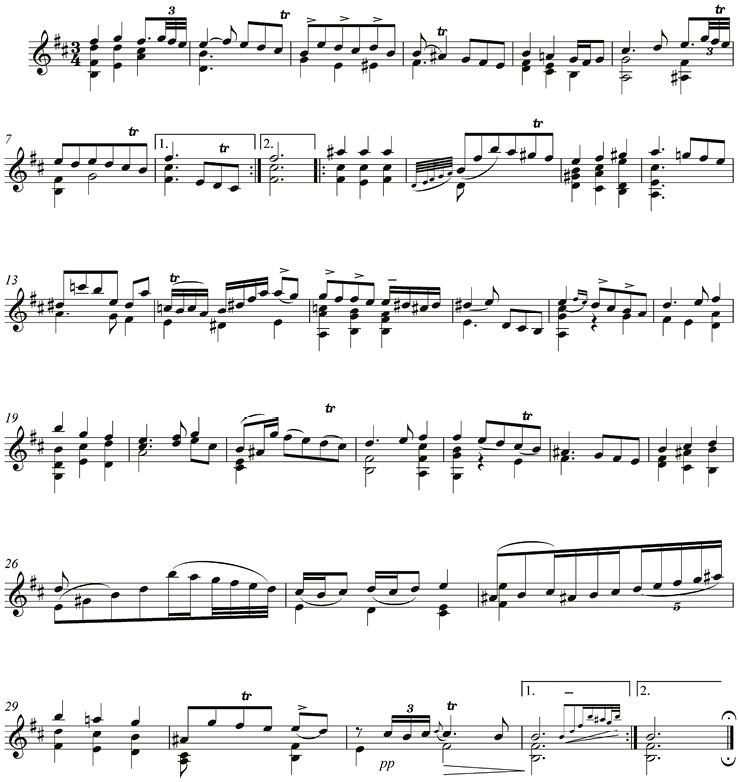

Figure 4.3. A minor Andante, bb. 12-24. Transcription of melodic embellishments in Gringolts’ performance during repeat.

Similar observations could be made in relation to the E Major Loure or B minor Sarabande as well. The Loure is a particularly good example of the idiosyncratic nature of Gringolts’ ornamenting. In light of Schröder’s recommendation that the movement should never sound busy and should always retain a sense of “quiet nobility,” Gringolts’ reading seems a-historical.40 It sounds busy, indeed. The near constant addition of notes, trills, slides, scalar figures and appoggiaturas requires him to play with very light, uneven bowing, creating continuous chiaroscuro effects as he glides up and down and across the strings. Nevertheless he maintains some of the key rhythmic elements and pulse of the Loure (Audio example 4.3).

4.3. Ornamentation in J. S. Bach, E Major Partita BWV 1006, Loure, extract: repeat of bars 5-20. Ilya Gringolts © Deutsche Grammophon [edited sound file, first time play of bars 12-20 eliminated to show only the repeats]. Duration: 0.58.

To listen to this extract online follow this link: http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0064.09

The special quality of his playing becomes particularly clear when compared to other versions (cf. Audio examples 4.7, 4.12, 5.1 and 5.2). Although in the Sarabande Gringolts’ embellishing contains a few more metrically well-defined moments (for instance b. 7), elsewhere it again tends to sound overelaborated (e.g. b. 11) as I will discuss in more detail below. Here too the overall effect is created by the “gliding” bow strokes and the many smooth, sliding filler notes that grace not just larger melodic leaps but stepwise motions as well (cf. Audio example 4.4 contrasting Mullova, Gringolts and Luca, below).

While transcriptions convey well the differences between Luca’s and Gringolts’ ornamentation of the A minor Andante, with the B minor Sarabande the situation is different. Here the visual information can be deceptive because the transcription of Mullova’s decorations may seem just as lavish as Gringolts’ (Figure 4.4a, b). Furthermore, some of her solutions resemble those of Gringolts in terms of placement and shape or pitch content. Yet the delivery, the sound of their respective performances is very different, highlighting the difficulty in finding academically meaningful (and printable) presentations of critical observations—or rather, it underscores the difficulty in making the object of study (aurally perceived sound) readily available for analysis, for visual and verbal dissection.

One of the similarities between the transcriptions is found in measure 17. Both musicians grace the E dotted crotchet with an upper neighbour motion, but Mullova plays the two semiquavers ornamentally (i.e. soft, light), like Luca, not melodically as Gringolts does. In the transcriptions I aimed to convey this by using smaller notes for Mullova and normal semiquavers for Gringolts. Similarly, she plays the upward runs in bars 32 and 10 before the beat, giving emphasis to the downbeat and not affecting the basic pulse. Gringolts, on the other hand, while using a practically identical type of embellishment in b. 10, plays it in a less dotted and rhythmical manner. It sounds more like a gracing of the high B that he introduces as anticipation at the end of the previous bar (Figure 4.5a).41 Through his constant diminution of rhythm and anticipation or delay of harmonic notes Gringolts loosens the sarabande pulse that Bach so clearly outlined with harmonic, melodic and rhythmic structures. Mullova’s performance remains close to the implications of the score and is metrically steadier, with a less altered melody line. As one reviewer put it, “she adorns the ‘open spaces’ of the Sarabande of the B minor Partita in a delightful fashion” and “with discretion.”42 Her embellishments fulfill their supposed historical function as they heighten the rhythmic-melodic-harmonic character of the music. Gringolts’ constantly flowing, light flourishes cover up these underlying structures. To better appreciate the differences and to exemplify Mullova’s own interpretative trajectory, I have included the same section in all three of Mullova’s commercial recordings (in chronological order), followed by Gringolts’ performance and then Luca’s discussed below (Figure 4.4c). Mullova’s 1987 recording (the first example heard in the audio) has no ornaments and thus establishes the reference for Bach’s score (Audio example 4.4: repeat of bb. 9-17 Mullova 1987, 1993, 2008 followed by Gringolts then Luca. For other, unembellished versions see Audio example 4.17).

4.4. Ornamentation in J. S. Bach, B minor Partita BWV1002, Sarabande, extract: repeat of bars 9-16. Five versions: Viktoria Mullova 1987 © Philips, 1992 © Philips, 2008 © Onyx, Ilya Gringolts © Deutsche Grammophon, Sergiu Luca © Nonesuch. Duration: 2.31.

To listen to this extract online follow this link: http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0064.10

Figure 4.4a. B minor Sarabande—Transcription of embellishments in Gringolts’ performance of the repeats.

Figure 4.4b. B minor Sarabande—Transcription of embellishments in Mullova’s 2008 performance of the repeats.

In comparison to these highly ornamented versions I offer a transcription of the more sparsely embellished performance of Luca, bars 9-17 of which are heard at the end of Audio example 4.4 (Tognetti, Tetzlaff and Holloway embellish the movement so sparsely that it is not worth commenting on; it is enough just to enjoy!). What is interesting about Luca’s performance is the way he also varies accenting, articulation and rhythm during the repeats (e.g. both the dotting in bb. 8, 16 and the paired slurs in b. 15 are heard only during repeat). Although the added decorations often fall on the downbeat, their shape, rhythm and delivery tend to function so as to give impetus to the second beat of the measure, which is traditionally accented in sarabandes (e.g. bb. 2, 3, 10).

Figure 4.4c. B minor Sarabande—Transcription of embellishments in Luca’s

performance of the repeats.

The E Major Menuet is another movement worth considering briefly. Being in the French style some players (e.g. Schröder, Podger, St John) introduce slight dotting or lilted playing of the quavers. Podger also adds short graces, trills and mordents, during repeats. Given its simple structure and many repetitions (especially if Menuet I is played again as a da capo after Menuet II and with all repeats), it seems quite reasonable to expect HIP performers to add decorations. This is not really the case. Apart from Podger and Wallfisch it is again the HIP-inspired MSP violinist who ornament the most, in particular Isabelle Faust (cf. Table 4.5). She performs all repeats in the da capo as well and not twice the same way. What is wonderfully playful about her rendering is that she uses ideas and figures from different parts of the movement to vary other bars. It teases the ear and brings a smile on the listeners’ face, as I have often found in conference and class presentations. The Audio example offers one straight and two slightly lilted interpretations of the first 8 bars—with St John’s an instance of the latter. This is followed by Faust’s recording edited so that only repeats are played taken from her performance of Menuet I and the Da Capo of Menuet I (Audio example 4.5).

4.5. Ornamentation and lilted rhythm in J. S. Bach, E Major Partita BWV1006, Menuet I, four extracts: bars 1-8. Jaap Schröder © NAXOS; bars 1-8 with repeat. Rachel Podger © Channel Classics; bars 1-8. Lara St John © Ancalagon; embellished repeats from Menuet I and its Da Capo. Isabelle Faust © Harmonia Mundi [edited sound file to show repeats only]. Duration: 2.31.

To listen to this extract online follow this link: http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0064.11

I identified and discussed several similar findings in relation to the other ornamented movements in my 2013 paper (see fn. 17), to which the interested reader is referred. However, I need to make one amendment to the data presented in that paper. There I state that “except for Luca adding two graces in measures 6 and 21, Faust is the only violinist who embellishes the D minor Sarabande, although I have heard it embellished by others in live concerts” (p. 18). Since publication I have noticed that Huggett adds soulful embellishments during the first repeat while Beznosiuk and Barton Pine add grace notes and short ornaments in a few bars: Beznosiuk in bars 1, 2, 6 and 21; Barton Pine (only on the commercial disk from 2004) in bars 4, 6, 11-12 and 18-19.43 What Beznosiuk does is simpler but at times similar to Faust’s solutions in that he plays around with adding mostly appoggiaturas. Barton Pine adds an appoggiatura in bar 6 and light-fast turn-like graces and trill elsewhere. Overall Beznosiuk’s playing is not just less embellished but also much more reserved and measured than Faust’s or Barton Pine’s. In addition Huggett plays most of the semiquavers in the second half, but in particular the coda (bb. 25-29), as if she was improvising (Audio example 4.6).

4.6. Ornamentation in J. S. Bach, D minor Partita BWV 1004, Sarabanda, six extracts: repeat of bars 1-8. Two versions: Pavlo Beznosiuk © Linn Records, Isabelle Faust © Harmonia Mundi; repeat of bars 16-21. Two versions: Isabelle Faust, Pavlo Beznosiuk; repeat of bars 4-21. Rachel Barton Pine 2004 © Cedille [edited to show only repeats]; repeat of bars 1-8 and 25-29. Monica Huggett © Virgin Veritas. Duration: 5.05.

To listen to this extract online follow this link: http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0064.12

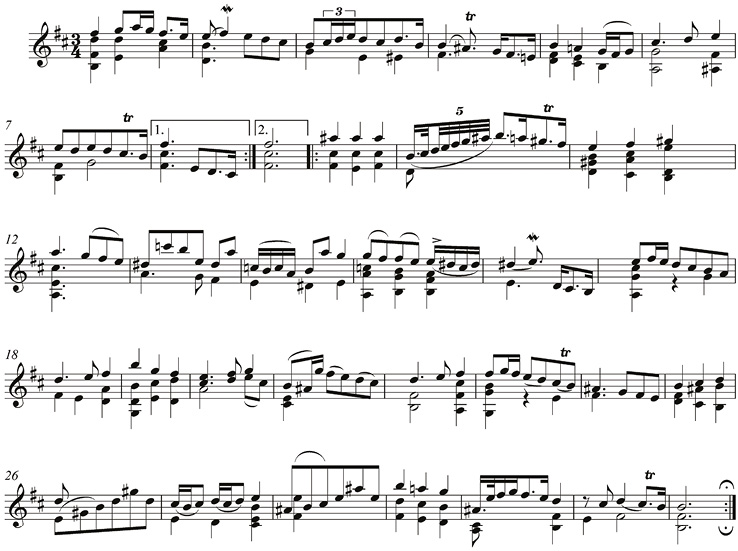

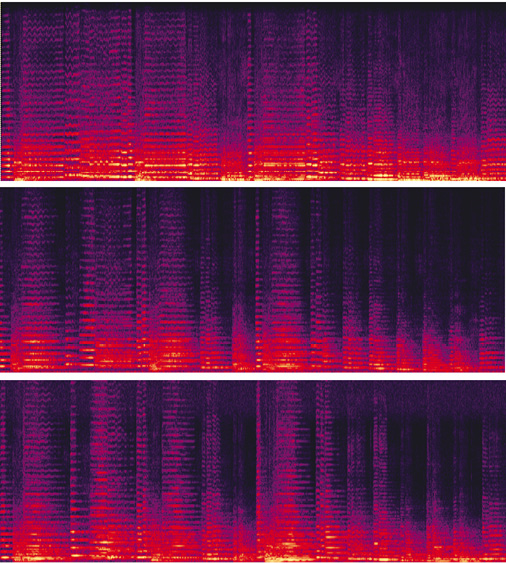

Otherwise enough has already been said here regarding the fundamental aesthetic issue: whether the added ornaments fit well with the pulse and overall musical character of the movement or go somewhat against these. Other details, such as the appropriateness of choosing upper or lower appoggiaturas, compound ornaments, and so on (discussed in my above mentioned paper) seem like moot points. Few listeners are acutely aware of eighteenth-century rules and even fewer would register such minor details when listening to the recordings. The speed with which such ornaments pass by is frequently quite fast. Accurate transcription is often only possible by repeated close listening and slowing down the recording to half or slower speed with the aid of computer technology: useful for creating accurate data but of little ecological value. So to conclude this exploration of ornamented-embellished examples I rather just recommend listening to the brilliant and playful passage work that varies statements (usually but not always the last) of the Gavotte and Rondeau’s theme (Figure 4.5; see also Audio example 5.6 illustrating Gringolts’ embellishing recurrences of the theme) and the many graces and melodic alterations in the Loure (Figure 4.6 and Audio example 4.7). In the Loure the differences in sound effect, in delivery, are hard to convey in transcription. The scale up to the top B in bar 1, for instance, is played quite differently by all 3 violinists who introduce it (van Dael, Wallfisch and Mullova). And this is so even though all three of them use the gesture to create a spritely effect, to point up the rhythm and create energy! Speed, bowing, timing, and articulation contribute to the clearly perceivable aural difference.

Figure 4.5. Gavotte en Rondeau, E Major Partita: theme and its major variants.

Figure 4.6. Transcription of 7 different ornamentations during the repeat of bars 1-3 of the Loure, E Major Partita WITH audio 4.7.

4.7. Ornamentation in J. S. Bach, E Major Partita BWV 1006, Loure, extract: repeat of bars 1-3. Seven versions: Ilya Gringolts © Deutsche Grammophon, Isabelle Faust © Harmonia Mundi, Viktoria Mullova 2008 © Onyx, Lucy van Dael © NAXOS, Elizabeth Wallfisch © Hyperion, Sergiu Luca © Nonesuch, and Richard Tognetti © ABC Classics. Duration: 1.53.

To listen to this extract online follow this link: http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0064.13

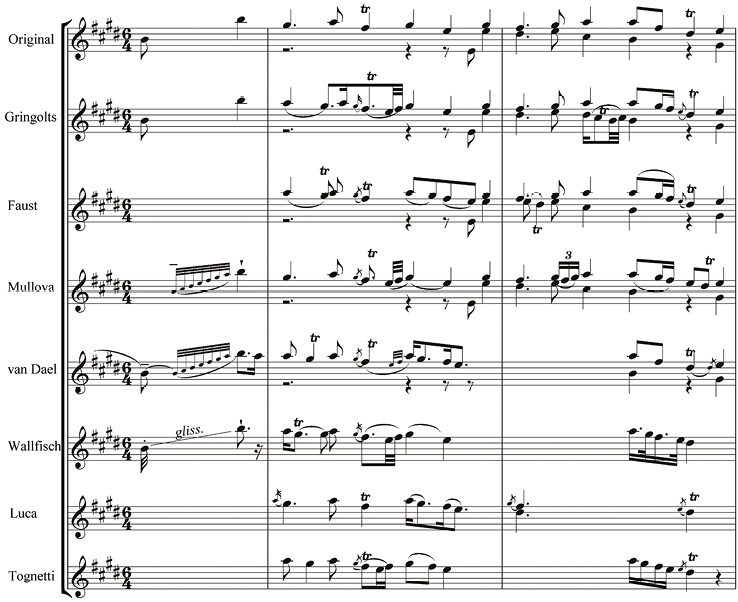

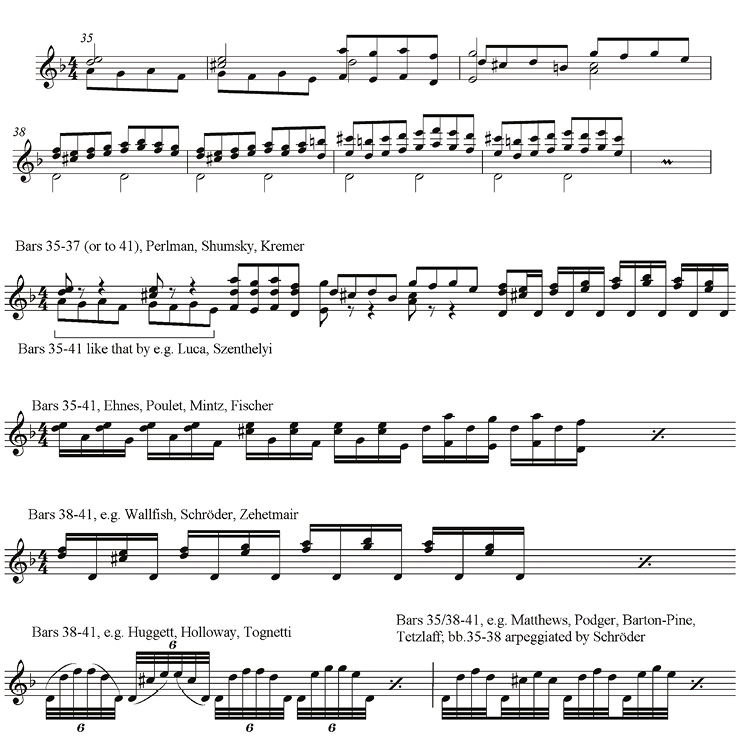

Moving on from added ornaments and returning to questions of understanding the meaning of notation, one particular moment of the set needs our attention: the final two bars of the A minor Grave (Figure 4.7). This excerpt illustrates spectacularly the rich variety of interpretations and individual solutions currently available on record. At least eighteen different solutions can be identified among the thirty-one examined recordings (Table 4.6). Such diversity challenges the claims that today’s performances occupy a uniform scene with very few real individuals compared to the “golden age” of the early recording era.

How to render the notation of the two double stops in the penultimate bar is open to debate (Figure 4.7), although Neumann asserts, on the basis of considerable evidence and concurring with several other authors, that the wavy line Bach notated indicates vibrato.44 According to Neumann a combination of bow and finger vibrato should be used followed by a trill starting on the main note.45

Figure 4.7. Grave, A minor Sonata: facsimile of final bars.

Older MSP versions tend to trill the top notes or just the D#, more recent and HIP versions (except for Huggett and Ibragimova) seem to opt for a kind of tremolo effect achieved through “bow vibrato.” This is a term used by several authors and is related to what Moens-Haenen calls “measured vibrato.”46 She explains it as playing with “controlled pressure changes of the bow” and states that the “beats should be strictly in time” because “measured vibrato is as a rule written out by the composer” (in eighth or sixteenth-notes that are indicative of speed). The resulting pulsating sound is said to emulate the tremulant stop on the organ. Other authors use the term “bow vibrato” and discuss its possible context and execution a little less categorically. They seem to agree that the wavy line here may be a sign for this tremolo-vibrato effect. Stowell cites Baillot’s treatise identifying “a wavering effect caused by variation of pressure on the stick”;47 Neumann claims that “in the Italo-German tradition vibrato was often done by bow pulsation,”48 whereas Ledbetter suggests vibrato or a “sort of bow vibrato.”

Since [the pair of wavy lines] seems to have something to do with going up a semitone, one obvious possible interpretation is the vibrato (flattement) followed by glissando up a fret (coulé du doigt) common in French viol repertory. The flattement can be either a finger vibrato (striking lightly, repeatedly, and as closely as possible to the fixed finger with the finger adjacent to it), or it can be a wrist vibrato. Marais and others use a horizontal wavy line for this. […] In the Brandenburg Concerto the solo parts [from measure 95] are accompanied in the ripieno by a sort of bow vibrato (repeated notes under the slur), and that also is a possible interpretation of the wavy line. J.J. Walther (1676) uses repeated notes with a wavy line to indicate this.49

Basically, the accelerating frequency of energy pulsation creates an effect that is similar to what Caccini (1602) and others of the early baroque period called the trillo (rapidly repeated pitch) and that is indeed very similar to the tremulant stop on the organ. Since in the A minor Grave the effect is not written out in small note values but simply indicated by a wavy line connecting two held notes, the choice between finger and bow vibrato remains open and thus the term “bow vibrato” seems more appropriate than “measured vibrato.” Bow vibrato is also distinct from “tremolo” which is achieved by rapid up-down bow movements rather than change in bow pressure.

Other possibilities for variety include the shape and speed of trills and tremolos, choice of dynamics and articulation (e.g. slurring the dyads), and the decisions whether to add short or long, lower or upper appoggiaturas and / or terminations to the trill(s), to play the final octave with or without anticipation, and whether to emphasize either note of the final octave. Altogether approximately eighteen different solutions were found in thirty-one examined recordings; some more subtle than others. Table 4.6 provides a summary of the main choices without differentiating all the nuances that are clearly audible and make each version slightly different from the other. These nuances are illustrated through a selection of audio excerpts (Audio example 4.8).

4.8. Interpretations of the notation at the end of J. S. Bach, A minor Sonata BWV 1003, Grave, extract: bars 22-23. Eight versions: James Ehnes (© Analekta Fleurs de lys) trilling both notes in both dyads; James Buswell (© Centaur) trilling the top notes of the dyads; Miklós Szenthelyi (© Hungarton) strongly vibrating the first dyad and then trilling the top note; Lara St John (© Ancalagon) trilling the top note and then both notes; Pavlo Beznosiuk (© Linn Records) producing a trillo (bow-vibrato) on the first dyad followed by a trill on the second; Brian Brooks (© Arts Music) performing a less obvious bow vibrato; Benjamin Schmid (© Arte Nova) playing a crescendo with increasing vibrato leading to trill on second dyad followed by decrescendo; Alina Ibragimova (© Hyperion) playing without vibrato, creating a small mezza-di-voce on the first dyad then a trill with diminuendo on the second. Duration: 2.43.

To listen to this extract online follow this link: http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0064.14

Table 4.6. Summary of solutions in the penultimate bars of the A minor Grave

|

Both notes trilled in both dyads |

Top note trilled in first and both trilled in second dyad |

Top note trilled in both dyads |

Top note trilled in second dyad |

Both dyads with vibrato (tremolo) followed by trill† |

Vibrato and / or crescendo followed by trill |

Straight (with crescendo or messa di voce) followed by trill* |

|

Huggett Ehnes Kremer ‘05 |

St John |

Ricci Perlman Mintz Buswell |

Shumsky Poulet Kremer ‘80 |

Luca Kuijken Schröder van Dael Barton Pine Brooks Tetzlaff Tognetti Holloway Beznosiuk Mullova |

Szenthelyi Zehetmair Wallfisch |

Podger Ibragimova Fischer Schmid Gringolts Khachatryan |

† Brooks’s and Tetzlaff’s delivery seems to be a combination of bow and finger vibrato perhaps closer to tremolo.

* Fischer and Schmid create a crescendo-decrescendo over the duration of the two dyads (accompanied by increasing-decreasing vibrato) whereas Ibragimova performs a messa di voce proper on the first dyad alone without any vibrato and articulates the second dyad quite separate from the first. There is hardly any crescendo-decrescendo in Podger’s and Khachatryan’s versions; straight-held dyads with trill on D# although one can perhaps detect a very slight tremolo/vibrato in Podger’s.

Our discussion of ornamentation started with the need to understand what Bach’s notations mean; to render the many small note values as if spontaneously unfolding improvisations over an imagined melody. Circling back to such broader issues, the contention that ornamentation should always be improvised is worth unpacking. So far I have argued that the performance should sound as if improvised. How are we to know, really, whether or to what degree an added ornament is pre-planned or spontaneous? Musicians intimately familiar with a particular style are able to play extempore, they just have not been encouraged much to do so until recently.50

People, including musicians, used to say that ornamentation in recorded performance is not desirable because of the repeatability offered by the medium. The idea being that the listener will not be able to hear it as improvised, or as an added ornament, because it will recur unchanged in each playing of the record. It may even become annoying to hear it over and over again instead of “the music proper.” Christopher Hogwood apparently advised his players against ornamenting in the recording studio

because he felt that risk-taking, ‘wild risks’ and ‘fantastic cadenzas,’ improvisatory élan, spontaneity and dangerous living which would certainly elicit cheers in a live performance ‘nearly always pall on repeated hearings.’51

A debatable position, indeed! Yes, perhaps I hear some of these embellishments as if part of the composition—especially when they seem as fitting and enriching as in Mullova’s and Faust’s recordings. But I certainly don’t get tired of hearing them and due to the style of delivery, always hear them as embellishments.