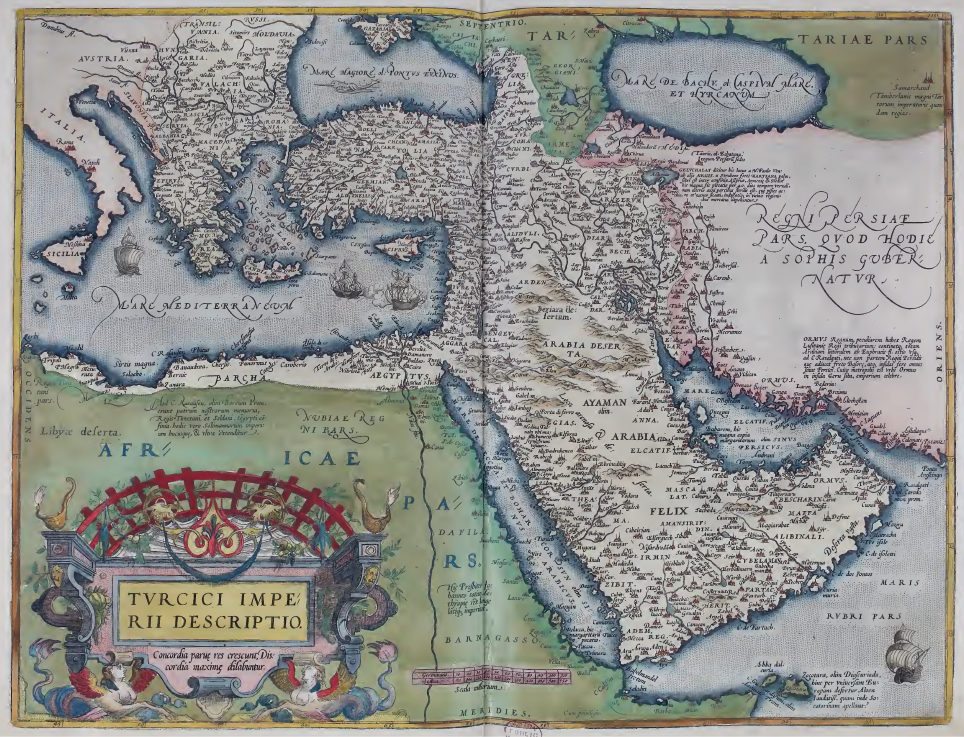

Map of the Ottoman Empire from Abraham Ortelius, Theatrum orbis terrarum (Antverpiae: Apud Aegid. Coppenium Diesth, 1570), p. 219, https://archive.org/details/theatrumorbister00orte

4. The Muslim Caliphates

© 2019 Erik Ringmar, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0074.04

After the death of the Prophet Muhammad in Medina in 632, his followers on the Arabian Peninsula quickly moved in all directions, creating an empire which only one hundred years later came to include not only all of the Middle East and much of Central Asia, but North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula as well. This was known as the “caliphate,” from khalifah, meaning “succession.” Yet it was difficult to keep such a large political entity together and there were conflicts regarding who should be regarded as the rightful heir to the Prophet. Thus, the first caliphate was soon replaced by a second, a third and a fourth, each one controlled by rival factions. The first, the Rashidun Caliphate, 632–661, was led by the sahabah, the “companions” who were the family and friends of the Prophet and who were all drawn from Muhammad’s own Quraysh tribe. The second caliphate, the Umayyads, 661–750, moved the capital to Damascus in Syria. And while it did not last long, one of its offshoots established itself in today’s Spain and Portugal, known as al-Andalus, and made Córdoba into a thriving, multicultural center.

The third caliphate, the Abbasids, 750–1258, presided over what is often referred to as the “Islamic Golden Age,” when science, technology, philosophy, and the arts flourished. The Abbasid capital, Baghdad, became a center in which Islamic learning combined with influences from Persia, India and even China. These achievements came to an abrupt halt when the Mongols sacked the city in 1258. From then on it was instead Cairo that constituted the center of the Muslim world. Yet the caliphs in Cairo too were quickly undermined, in this case by their own soldiers, an elite corps of warriors known as the mamluks. The next Muslim empire to call itself a “caliphate” was instead the Ottoman Empire, with its capital in Istanbul, the city the Greeks had called “Constantinople.” Although the Ottomans were Muslims, they were not Arabs but Turks, and they had their origin in Central Asia, not on the Arabian Peninsula.

Despite the continuing story of political infighting and fragmentation, the idea of the caliphate continues to exercise a strong rhetorical force in the Muslim world to this day. During the caliphates the Arab world experienced unprecedented economic prosperity and a cultural and intellectual success which made them powerful and admired. Not surprisingly perhaps, the idea of restoring the caliphate is still alive among radical Islamic groups who want to boost Muslim self-confidence.

The Arab expansion

After the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632, the various families, clans and, tribes that made up the population of the Arabian Peninsula seemed prepared to return to their former ways of life, which included perpetual rivalries and occasional cases of outright warfare. Yet a small but influential group of the Prophet’s followers, the sahabah, sought to preserve the teachings which he had left them and to keep the Arabs united. This, the sahabah believed, could best be achieved if their energies were directed towards external, non-Arab targets. Moreover, they were on a mission from God. The sahabah were the custodians of the revelation as given to Muhammad and their task was to spread the word and convert infidels to the new faith. The new leader of the community must consequently, many felt, combine the qualities which had characterized Muhammad — to be a religious leader but also a politician and military commander. In 632, it was the Prophet’s father-in-law, Abu Bakr, who best exemplified these qualities, and he was elected to be the first caliph of what later came to be known as the rashidun, or “rightly guided,” caliphate. During his short rule, 632–634, Abu Bakr consolidated Muslim control over the Arabian Peninsula, but he also attacked the southern parts of Iraq, occupied by the Persians, and the southern parts of Syria, occupied by the Byzantines.

The term jihad, “holy war,” is often used to describe this military expansion, yet political control, not religious conversion, was its main objective. The expansion may best be explained not by a religious but by a military logic. Since the troops of the caliphate were paid by the spoils of war — by what they could lay their hands on in the lands they conquered — the army could only be maintained as long as it continued to be successful. “Raids” is consequently a better term for many of these engagements than “battles,” even if the raids eventually turned into permanent occupations. Thus when the advance of the Muslim forces throughout Europe was eventually halted at the Battle of Tours in 732, this was regarded as a major triumph by European observers but merely as a temporary setback by the Arabs themselves. They simply retreated in order to fight another day. Moreover, since their occupation in many cases was quite superficial, it was often easy enough for the local population to reassert their independence. As a result, in several cases the Arabs had to reconquer the same territory over and over again.

The secret behind this astounding military success was a lightly armed and highly mobile fighting force. Although Muhammad and his immediate followers were merchants and city-dwellers, most of the population of the Arabian Peninsula were Bedouins. Mobility was key to survival in the harsh environment of the desert, and thanks to horses and camels, the Bedouins could cover large distances with great speed. Once they were formed into an army their horses could be used for swift attacks and their camels for transporting supplies. The neighboring empires — the Greeks in Byzantium to the west and the Persians to the east — were both stationary by comparison. As soon as the Arabs had mastered the basics of siege warfare, these sedentary societies were easily defeated.

Moreover, the Arabs were able to benefit from the fact that Byzantines and Persians had been each other’s worst enemy for centuries. After decades of relative peace, the wars between the two superpowers flared up again in the beginning of the seventh century, with devastating effects for both parties. Thus, when the Arab forces began their incursions from the south, both Byzantines and Persians were already considerably weakened. Yet, it was far more difficult for the Arabs to expand their territorial control wherever they encountered people who resembled themselves. This was the case in northern Africa where the Berbers, after some costly engagements, were not defeated as much as bought off and incorporated into the new Arab elite.

During the reign of the second caliph, Umar, who succeeded Abu Bakr in 634 and ruled for ten years, these military campaigns were dramatically extended. The caliphate now became an imperial power. It occupied the eastern parts of the Byzantine Empire, including Syria, Anatolia, and Egypt in the 630s; and then all of the Persian Empire in the 640s, including present-day Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia. Umar’s greatest achievement, however, was to give an administrative structure to the new state. Clearly, the institutions once appropriate for the cities of Mecca and Medina were not appropriate for the vast political structure which the caliphate now had become. Umar’s answer was the diwan, a state bureaucracy with a treasury and separate departments responsible for tax collection, public safety and the exercise of sharia law. Coins were minted by the state and welfare institutions were established which looked after the poor and needy; grain was stockpiled to be distributed to the people at times of famine. The caliphate engaged in several large-scale projects, building new cities, canals and irrigation systems. Roads and bridges were constructed too and guest houses were set up for the benefit of merchants or for pilgrims going to Mecca for the hajj. Umar, the second rightly guided caliph, has always been highly respected by Muslims for these achievements and for his personal modesty and sense of justice.

Although the occupation of lands outside of the Arabian Peninsula happened exceedingly quickly, converting the occupied populations to the new faith took centuries to accomplish, and in many cases, it never happened. As a result of its military victories, Islam became a minority religion everywhere the Arabs went and forced conversions were for that reason alone unlikely to prove successful. Moreover, conversions were financially disadvantageous to the authorities. Since non-Muslims were required to pay a tax, the jizya, which was higher than the tax for Muslims, a change of religion meant a loss of tax revenue for the caliphate.

Instead, the various non-Muslim communities, known as the dhimmi, were allowed to practice their religion much as before. As the new Arab rulers saw it, monotheistic religions such as Christianity, Judaism and Zoroastrianism were precursors of Islam, which the teachings of the Prophet had made redundant.

Zarathustra and Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism, just as Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, is a monotheistic religion. Zoroastrians call their deity Ahura Mazda, translated as “enlightened wisdom.” Zoroaster, or Zarathustra, who founded the faith, was born northeast of the Caspian Sea most probably sometime around 1200 BCE. He was the author of the Yazna, a book of hymns and incantations. After the fourth century of the Common Era, Zoroastrianism was the official and publicly supported religion of the Sasanian Empire, located in today’s Iran.

Like other monotheistic religions, Zoroastrianism grapples with the question of how a belief in one almighty god can be combined with the existence of evil. The Zoroastrian answer is that good and evil are choices that confront human beings, not entities that compete for power. Questions of correct conduct are a crucial part of their faith. Zoroastrian rituals rely heavily on fire which is regarded as a holy force. Fire temples, attended by priests, were constructed throughout the Sasanian Empire. Zoroastrianism had a powerful influence on the other monotheistic religions of the Middle East, and many of its main themes — questions of the afterlife, morality, issues of judgment and salvation — feature prominently in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam too. Moreover, Zoroastrianism was the first religion that regarded people as equals before God and gave every believer the opportunity to attain salvation.

Although the conversion took several centuries to accomplish, some 95 percent of Zoroastrians eventually switched to Islam. There are still Zoroastrians today, but not many. In Iran, an official census has counted less than 30,000. Yet the Persian new year, Nouruz, which was central to the Zoroastrian faith, is still the most important holiday in Iran. On occasions when the mandatory fasting required during Ramadan has come into conflict with the eighteen days of festive celebrations required by Nouruz, the Zoroastrian tradition has prevailed.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/b7bffe6e

The military success of his followers, in their own eyes, had proven the viability of the new faith. Other religions were regarded as the colorful remnants of an older order, but not as threats to Islam itself. Indulging them, the Arab rulers allowed them to govern their respective communities in accordance with their own customs. Christians, for example, could continue to drink alcohol and eat pork. Though the dhimmi lacked certain political rights that came with membership in the community of Muslim believers, they were regarded as equal with Muslims before the law and they were not expected to become soldiers in the caliphate’s armies.

In 644, Umar was assassinated by a slave during a hajj to Mecca, apparently in revenge for the wars which the Arabs had waged against the Persian empire. This time, the problem of succession became acute. The question of who should take over as caliph raised issues concerning the proper distribution of power among the small elite of the Prophet’s Arabian followers. The most obvious choice was Ali, Muhammad’s son-in-law, who had married Fatimah, the only one of the Prophet’s children who survived him. Yet it was instead Uthman ibn Affan who became the third caliph. Uthman too was an early convert to Islam and one of the Prophet’s closest companions but — and probably more importantly as far as the question of succession was concerned — he was a member of the Umayyads, one of Mecca’s oldest and best-established families.

Once elected, Uthman dispatched military expeditions to recapture regions in Central Asia which had rebelled against Arab rule. He also made war on the Byzantine Empire, occupying most of present-day Turkey and coming close to besieging Constantinople itself. Rather more surprisingly for a military force largely made up of Bedouins, Uthman constructed an impressive navy which occupied the Mediterranean islands of Crete, Rhodes, and Cyprus and made raids on Sicily. At the end of the 640s, when the Byzantine attempt to recapture Egypt failed, all of North Africa came under the caliphate’s control.

Despite these military advances, it was difficult to maintain peace between the various factions of the caliphate’s elite. Indeed, the rich spoils which the Arab armies encountered in countries such as Syria and Iraq constituted a new source of conflict. During Umar’s reign the soldiers had been paid a stipend, been quartered in garrisons well away from traditional urban areas, and been banned from taking agricultural land. During Uthman's leadership these policies were reversed. This led to resentment as a new land-owning Arab elite came to replace traditional leaders. Uthman was also accused of favoring members of his own family when it came to appointing governors to the new provinces. Another source of conflict was Uthman’s attempt to standardize the text of the Quran and thereby to force all believers to accept his interpretation of its message.

Resentment against these policies was channeled into support for Ali, Muhammad’s son-in-law, and before long an uprising against Uthman was underway. In 656, three separate armies marched on Medina, laid siege to Uthman’s house and killed him. Now it was finally time for Ali to become the new leader. He remained in power for five years, 656–661, but his rule was undermined by continuous conflicts. Uthman’s followers wanted revenge and insisted that Ali should punish the people who had murdered him. This, however, was difficult for Ali to do since it was thanks to them that he had come to power. In addition, Uthman’s relatives and associates in the provinces wanted to protect their assets and their new landholdings. The result of these conflicts was the First Fitna, the first civil war between Muslims, which broke out in 657. Ali’s forces met the forces of the Umayyads at Siffin, in today’s Syria, but instead of a military confrontation, Ali decided to settle the matter by means of negotiations. This led some of his supporters to abandon his cause, and in 661 he was murdered by one of them. Muawiyah, the leader of the Umayyads, now established himself as the new caliph. However, this succession was disputed by Husayn, Ali’s son, and once again war broke out. In the year 680, Husayn was ambushed and killed together with his whole family.

This is the historical origin of the split between the Sunni and the Shia, the two largest denominations of Muslims in the world today. According to Shia beliefs, Ali had been designated as the Prophet’s immediate successor, and his son and Muhammad’s grandson, Husayn, was thus the rightful heir. Shia Muslims continue to believe that the caliphate was taken away from them by the Umayyad family and that authority in the Muslim world is illegitimately exercised to this day. They even blame themselves for Husayn’s killing, since too few of his followers came to his support. On the day of his death, Ashura, a festival of mourning and repentance is celebrated by Shia Muslims. The processions held in Karbala, Iraq, where Husayn died, are the most spectacular, with millions of believers attending. These festivals have often been the targets of violence by non-Shia groups. Although only about 10 percent of all Muslims are Shia, they constitute today around 30 percent of the population of the Middle East.

The Umayyads and the Abbasids

The Umayyad Caliphate, 661–750, was a time of military consolidation rather than expansion, but it was above all a time when the caliphate established itself as a proper empire, ruled by institutions and bureaucratic routines. Muawiyah, who had been governor of Syria, began by moving the capital to Damascus. It was there that the caliphate’s first coins were minted, instead of copies of Byzantine originals. It was also then that a regular postal service was set up, a requirement for disseminating information, instructions and decrees across the empire. And crucially, Arabic was made into the official language of the state, replacing Greek and an assortment of other languages. Greek had been spoken by administrators throughout the Middle East since the days of Alexander the Great — for close to a thousand years — but from the Umayyad Caliphate onward you had to know Arabic if you aspired to an administrative career. As a result, territories in which no Arabic speakers had previously existed, such as Egypt, were Arabized for the first time. And with Arabization, in many cases, came conversion to Islam.

Yet no amount of administrative reorganization could stop political conflicts from tearing this caliphate apart too. In the middle of the eighth century, the Umayyads were challenged by new regional elites, in particular by the governors of Iraq, a fertile and rich part of the empire. Before long a new civil war, the Second Fitna, broke out. In 750 the Umayyads were decisively defeated and the Abbasid Caliphate, 750–1258, took their place. The Abbasids claimed descent from Abbas, Muhammad’s youngest uncle. Their first capital was Kufa, in southern Iraq, but in 762 they constructed a new capital in Baghdad. It was soon to become the largest and richest city in the world and a great center of culture and learning.

In Baghdad many cultures mixed freely and, much as elsewhere in the Muslim world, the dhimmi were given the right to run their own affairs. During the Abbasid Caliphate, the influences from Persia and Central Asia were strong. Persians, or rather Arabized Persians, were employed in the administration of the caliphate as advisers and judges, and Persian scholars and artists populated the caliph’s court. Cultural influences did not only come from Persia, however, but also from far further afield. From the Indians the Arabs learned about the latest advances in mathematics. Read more: Indian mathematics at p. 48.

Through exchanges with China, the Arabs came to master the secrets of paper-making and soon a paper mill was established in Baghdad. Since paper is far cheaper to produce than parchment or papyrus, it was suddenly possible to gather far larger collections of books. Libraries were established throughout the caliphate which contained hundreds of thousands of volumes. At the time, the caliph’s library in Baghdad had the largest collection of books in the world.

Arabian Nights

One Thousand and One Nights is a collection of folktales compiled in Baghdad during the Islamic Golden Age. It is often known in English as The Arabian Nights from the first English-language translation, undertaken in 1706, which rendered the title as “The Arabian Nights’ Entertainment.” The work was not written by a single author but instead assembled over many centuries by various translators and editors. Caliph Harun al-Rashid was in charge of one of the main editions, and he also featured as a protagonist in some tales. Other stories retell plots popular in Indian, Persian and Arabic folklore and include love stories, tragedies, poems, and burlesques. There are murder mysteries too and horror stories featuring jinns, ghouls, sorcerers, and magicians. Many of the tales — such as “Aladdin’s Wonderful Lamp” or “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves” — were not part of Harun al-Rashid’s original compilation but were instead added by European translators.

All the editions of The Arabian Nights share the same framing device. This is the story of a Persian king who despairs at the infidelity of women. In order to make sure that his wife remains faithful he decides to marry a succession of virgins and have each killed on the day after their wedding night. Eventually, the king’s vizier, whose duty it is to provide the women, cannot find any more virgins for the king. This is when Scheherazade, the vizier’s own daughter, offers herself as the next bride. On the night of their marriage, Scheherazade begins telling him a story, but without finishing it. Curious to hear the conclusion, the king postpones her execution. Each night, as soon as one story had ended, she begins telling a new one, and in this way, the king is forced to let her live. The ruse is repeated for 1,001 consecutive nights. In the end, Scheherazade’s life is spared.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/6941bc5f

During the Abbasid Caliphate, the Arab world received influences from Byzantium too. Indeed, since Byzantium remained the caliphate’s greatest military enemy, competition with this remnant of the Roman Empire was intense. One cultural expression of their rivalry was the so-called “translation movement” which began during the reign of the founder of the Abbasid Caliphate, al-Mansur, 754–775. Compared to the Greeks, the Arabs were social upstarts and although their cultural sponsorship was paying off handsomely, they had none of the historical prestige of the Greeks. Indeed, the Arabic language had until recently been spoken mainly by Bedouins in the desert and it lacked much of the technical terminology required to express philosophical and scientific ideas. All too aware of these deficiencies, the Abbasid caliphs embarked on a vast project of translating Greek books into Arabic.

The translation movement

With the fall of Rome, the cultural heritage of classical Greece was lost to Western Europe and next to no Europeans knew how to read Greek. Instead, the texts survived in translations into Arabic. The Abbasid Caliphate sponsored these translations and the caliphs took a personal interest in the project. The translations were often carried out by Syrian Christians, who spoke both Greek and Arabic, and they often used Syriac as an intermediary language. The translators would send for manuscripts from Byzantium, or they would go there themselves to look for books. They were handsomely rewarded for their efforts — a translator might be paid some 500 golden dinars a month, an astronomical sum at the time.

There were two main circles of translators in Baghdad, centered on the scholars Hunayn ibn Ishaq and al-Kindi. Having mastered Arabic, Syriac, Greek, and Persian, Hunayn translated no fewer than 116 works, especially medical and scientific texts, but also the Hebrew Bible. His son and nephews joined him as translators in his workshop. Hunayn was notable for his method which began with literal translations on which he based subsequent, rather loose paraphrases of the original text. Hunayn also wrote his own books, some thirty-six works altogether, of which twenty-one were concerned with medical topics. Hunayn may also be the author of De scientia venandi per aves, a book on falconry much admired in the Middle Ages.

Al-Kindi was Hunayn’s near-contemporary and the head of a rival circle of translators. Although al-Kindi knew no Greek himself, his collaborators did, and he spent time overseeing and editing their work. The members of the al-Kindi circle were the first to translate many titles by Aristotle and other Greek philosophers. Al-Kindi also wrote his own books. In On First Philosophy, he gave an impassioned defense of why translations from Greek were necessary. The truth is the truth, he insisted, regardless of the language in which it is expressed. Al-Kindi is said to have introduced Indian numerals to the Islamic world, and he was a pioneer in cryptography. He also devised a scale that allowed doctors to assess the potency of the medication they gave patients.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/8394a664

Despite its glories and successes, Baghdad was not the only center of the caliphate. Indeed, in Iraq itself, Basra and Samarra were important hubs, and in Central Asia different cities were run by increasingly assertive local rulers. Much like the caliphs in Baghdad, they wanted not only political power but also the reputation of running an intellectually and culturally sophisticated court. Thus the library of the rulers of Shiraz, in Persia, was reputed to have a copy of every book in the world, and the library in Bukhara, in today’s Uzbekistan, had a catalog which itself ran to thousands of volumes — besides, the library provided free paper on which its users could take notes. Meanwhile, the local rulers of Afghanistan made that part of the Abbasid Caliphate into a center of learning. The leading scholar here, Abu Rayhan al-Bīrūnī, went to India and returned with books on astronomy and mathematics which he synthesized and expanded. Read more: Indian mathematics at p. 48.

As the power of these regional centers grew, the Abbasid rulers in Baghdad became correspondingly weaker. They lost power over North Africa, including Egypt, in the eighth century, and in the tenth century, they controlled little more than the heartlands of Iraq. Even in Baghdad itself, the caliphs lost power to the viziers, their prime ministers. Interestingly, the city seemed to benefit culturally from the political fragmentation and the new influences it provided. The majlis, or salon, was a particularly thriving institution. In the drawing-rooms of the members of the elite, scientists, philosophers and artists would meet to gossip, debate and exchange ideas. Here Muslims, Jews and Christians could mingle freely and often the political elites, including the caliphs themselves, would participate in the proceedings. The majlis provided a free intellectual atmosphere in which different opinions on matters of philosophy, religion and science thrived. This is how Muhammad al-Razi’s chemical discoveries — including the discovery of alcohol — became known, together with al-Farabi’s synthesis of the philosophies of Plato and Aristotle.

The glories of Baghdad, together with the Abbasid Caliphate itself, came to an abrupt end with the Mongol invasion of 1258. What the Mongols did to Baghdad counts as one of the greatest acts of barbarism of all time. A large proportion of the inhabitants were killed — estimates run into several hundreds of thousands — and all the remarkable cultural institutions were destroyed together with their contents. Survivors said that the water of the river Tigris running through the city was colored black from the ink of the books the Mongols had thrown into it, and red from the blood of the scholars they had killed. The caliph himself was rolled up in a carpet and trampled to death by horses. Baghdad never recovered from the devastation.

The Arabs in Spain

Although the Umayyads were decisively defeated by the Abbasids in 750, they were given a new and surprising lease of life — in the Iberian peninsula, on the westernmost frontier of the Arabic world. As the caliphate in Damascus was about to fall, a branch of the Umayyad family fled across North Africa and established itself in the city of Córdoba, in present-day Spain, or in what the Arabs referred to as “al-Andalus.” The Arabic incursion into Spain had started already in 711, with a small party of raiders, predominantly Berbers, making their way from Morocco to Gibraltar — or Jabal Ṭariq as they called it, “the mountain of Tariq,” named after their commander. In the end, all of present-day Spain and Portugal were occupied, except for a few provinces close to the Pyrenees in the north. In 756, the Umayyads established a new caliphate for themselves at Córdoba. They were greeted as saviors by the Jewish community who had suffered from persecution under the Visigoths, the previous rulers, and by many ordinary people too who had suffered under heavy taxation.

The Caliphate of Córdoba, 929–1031, was the high point of Arabic rule in Spain. This was, first of all, a period of great economic prosperity. The Arabs connected Europe with trade routes going to North Africa, the Middle East and beyond, and industries such as textiles, ceramics, glassware, and metalwork were developed. Agriculture was thriving too. The Arabs introduced crops such as rice, watermelons, bananas, eggplant, and wheat, and the fields were irrigated according to new methods, which included the use of the waterwheel. Córdoba was a cosmopolitan city with a large multi-ethnic population of Spaniards, Arabs, Berbers, Christians and a flourishing community of Jews. In Córdoba, much as in the rest of the Arab world, the dhimmi were allowed to rule themselves as long as they stayed obedient to the rulers and paid their taxes. The caliphs were patrons of the arts and fashion and their courtiers took up civilized habits such as the use of deodorants and toothpaste.

Deodorants and the origin of flamenco

Abu I-Hasan, 789–857, nicknamed “Ziryab” from the Arabic for “blackbird,” was a musician, singer, composer, poet, and teacher, who lived and worked in Baghdad, in Northern Africa, and during some thirty years also in al-Andalus in Spain. More than anything he was a master of the oud, the Arabic lute, to which he added a fifth pair of strings and began playing with a pick rather than with the fingers. Many good musicians assembled at the court in Córdoba, but Ziryab was the best. He established a school where the Arabic style of music was taught for successive generations, creating a tradition which was to have a profound influence on all subsequent Spanish music, not least on the flamenco.

The first references to flamenco can be found only in the latter part of the eighteenth century and then it was associated with the Romani people. Yet it is obvious that the flamenco is a product of the uniquely Andalusian mixture of cultures. The music does indeed sound Romani but at the same time also Arabic, Jewish, and Spanish. According to one theory, the word “flamenco” comes from the Arabic fellah menghu, meaning “expelled peasant.” The fellah menghu were Arabs who remained in Spain after the fall of Granada in 1492. Some of them joined Romani communities in order to escape persecution. The Arabs and the Roma must have enjoyed themselves playing guitar and dancing together.

As for Ziryab, he was also ninth-century Córdoba’s leading authority on questions of food and fashion. He was said to have changed his clothes according to the weather and the season, and he had the idea of wearing a different dress for mornings, afternoons and evenings. He invented a new type of deodorant and a toothpaste and promoted the idea of taking daily baths. He also made it fashionable for men to shave their beards. In addition, Ziryab popularized the concept of three-course meals, consisting of soup, main course, and dessert, and he was the person who introduced the asparagus to Europe. If a society’s level of civilization can be determined by its standard of hygiene, Ziryab had a profoundly civilizing impact on southern Spain.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/f2a0fb14

Córdoba was an intellectual center also. The great mosque, completed in 987 and modeled on the Great Mosque of Damascus, was not only a place of religious worship but also an educational institution with a library which contained some 400,000 books. The scholars who gathered here did cutting-edge research in the medical sciences, including surgery and pharmaceuticals. They reacted quickly to intellectual developments that were coming out of Baghdad and from other places in the Arab world.

Yet this caliphate too proved difficult to keep together. It fell apart in the first part of the eleventh century, as rivalries, a coup and a fully-fledged civil war — the Fitna of al-Andalus — pitted various factions against each other. In 1031, the caliphate disintegrated completely and political power in the Iberian peninsula was transferred to the taifa — the small, thirty-plus kingdoms which all called themselves “emirates” and all to varying degrees were in conflict with one another. This was when the Christian kingdoms in the north of the peninsula began to make military gains. Christian forces captured Toledo in 1085, and the city soon established itself as the cultural and intellectual center of Christian Spain.

The Toledo school

Once Toledo was captured in 1085, it became the most important city in Christian Spain and its cultural and intellectual center. Christians from al-Andalus took their refuge there, but intellectually speaking the city served more as a bridge than as a spearhead. The scholars who settled in Toledo were often Arabic-speaking, and they relied on Arabic sources in their work. When they came into contact with western Christendom, where Latin was the only written language, it became necessary to translate this material. In the first part of the twelfth century, Raymond, the archbishop of Toledo, set up a center in the library of the cathedral where classical texts were translated, together with the commentaries and elaborations provided by Arabic authors. This was an exciting task since the Arabs had access to many works, including classical Greek texts, which Europeans had heard of but never themselves read. This included works by Galen, Ptolemy, Aristotle, and many others. Gerard of Cremona was the most productive of the translators, completing more than eighty-seven works on statecraft, ethics, physiognomy, astrology, geometry, alchemy, magic and medicine.

The translation movement of Toledo in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries thus parallels the translation movement of Baghdad in the ninth and tenth centuries. The Arabs translated the classics from Greek into Arabic, and now the same texts were translated from Arabic into Latin. From Toledo, the classical texts traveled to the rest of Europe where they were used as textbooks at a newly established institution — the university. Read more: Nalanda, a very old university at p. 56. This is how Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas at the Sorbonne came to read Ibn Rushd and Ibn Sina, how Roger Bacon at Oxford became inspired by the scientific methods of Ibn al-Haytham and how Nicolaus Copernicus in Bologna read the works of Greek and Arabic astronomers. Renaissance means “rebirth” and what was reborn, more than anything, was the scholarship of classical antiquity — as saved, translated and elaborated on by the combined efforts of the scholars of Baghdad and Toledo.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/b733cd75

This is not to say that the various Christian kingdoms had a common goal and a common strategy. Rather, each Christian state, much as each Muslim, was looking after its own interests and waging wars with other kingdoms quite irrespective of religious affiliations. Thus some emirs were allied with Christian kings, while kings paid tribute to emirs, and they all employed knights who killed on behalf of whoever paid the highest salary. Quite apart from the military insecurity of the taifa period, this competition had positive side effects. The taifa kings sponsored both sciences and the arts. This is how small provincial hubs such as Zaragoza, Sevilla and Granada came to establish themselves as cultural centers in their own right.

Enter the Almoravids. Read more: North Africa at p. 131.

The Almoravids were a Berber tribe, originally nomads from the deserts of North Africa, who had established themselves as rulers of Morocco, with Marrakesh as their capital. After the fall of Toledo, they invaded al-Andalus and a year later, in 1086, they had already successfully occupied the southern half of the Iberian peninsula. However, they never managed to take back Toledo. In 1147, at the height of their power, the Almoravids were toppled and their leader killed by a rival coalition of Berber tribes known as the Almohads. The Almohads were a religious movement as well as a military force, and their rule followed strict Islamic principles: they banned the sale of pork and wine and men and women were forbidden to mix in public places. They burned books too — including Islamic tracts with which they disagreed — and insisted that Christians and Jews convert to Islam on pain of death.

Ibn Rushd and the challenge of reason

Ibn Rushd, also known as “Averroes,” was a scholar and a philosopher born in Córdoba in al-Andalus in 1126. He is famous for his detailed commentaries on Aristotle, whose work he strongly defended against those who regarded him as an infidel. Ibn Rushd, that is, defended reason against revelation. Or rather, he regarded revelation, as presented in the Quran, as knowledge suitable above all for the illiterate masses. Ordinary people are literal-minded, and they need miracles in order to believe. Miracles do indeed happen, Ibn Rushd argued, but they must correspond to the laws which govern the universe. If not, the universe will become arbitrary and unintelligible.

The works of Ibn Rushd came to have far-reaching influence on intellectual developments in Europe, in particular on the thinking of Thomas Aquinas. Aquinas, the Church Father whose Summa Theologica laid the foundations for all theological debates in the European Middle Ages, asked himself the very same questions as Ibn Rushd. He too wanted to know how to reconcile reason with revelation. Aquinas too was a great fan of Aristotle, and although he disagreed with many of Ibn Rushd’s specific arguments, his general conclusions were basically the same. Aquinas always referred to Ibn Rushd with the greatest respect, calling him “the Commentator,” much as he called Aristotle “the Philosopher.”

The seminal contribution which Ibn Rushd made to the intellectual development of Europe had no counterpart in the Muslim world. Here Ibn Rushd left no school and no disciples, and his works were barely read. It was only at the end of the nineteenth century that he was rediscovered. The immediate reason was a book by the French Orientalist Ernest Renan, Averroès et l’Averroïsme, 1852, in which Renan made a strong case for Ibn Rushd’s importance. Translating Renan’s book into Arabic, Muslim intellectuals discovered exactly what they had been looking for — an Arab who had made a seminal contribution not only to Arabic civilization but to the civilization of the world. To some contemporary Muslim intellectuals, the work of Ibn Rushd has become a symbol of a rationalistic intellectual tradition, in tune with modern society, liberalism and a scientific outlook on life.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/deab0a1f

By 1172, the Almohads had conquered all of al-Andalus. Under these circumstances many of the inhabitants preferred to flee — Christians to the north, while Jews fled east to Cairo and the Fatimid Caliphate, where the rulers were far more accepting of members of other religions.

Mosheh ben Maimon

Mosheh ben Maimon, commonly known as Maimonides, was a scholar, judge and medical doctor, born into an influential Jewish family in Córdoba in 1135. He is known as “Musa Ibn Maymun” in Arabic and as “Moses Maimonides” in Latin. Ben Maimon was trained both in the Jewish and the Arabic intellectual traditions, and he wrote in Judeo-Arabic, a classical form of Arabic which used the Hebrew script. Ben Maimon is most famous as the author of the fourteen-volume Mishneh Torah, a sprawling collection containing all the laws and regulations that govern Jewish life. The Mishneh Torah is widely read and commented on to this day.

In 1148, when the Almohad rulers of al-Andalus imposed their harsh reforms on their subjects, Christians and Jews were required to either convert or be killed. Ben Maimon and his family escaped to Egypt, which at the time was run by the Fatimid caliphs, a far more tolerant regime. In Cairo, he established himself as an interpreter of the Torah and as a teacher in the Jewish community. This is also when he wrote his most famous philosophical work, Guide for the Perplexed. We are knowledgeable about Ben Maimon’s life thanks to the Cairo Geniza, a collection of up to 300,000 fragments of manuscripts discovered in the synagogue in Cairo. Since Jews were afraid to throw away any piece of paper which may have the name of God written on it, they ended up with a very large collection of scraps of papers of all kinds. The papers were kept in a “geniza,” a storage room, and the Cairo Geniza, once the historians investigated it, turned out to include much of Ben Maimon’s personal notes and correspondence.

Ben Maimon is buried in Tiberias, in today’s Israel. On his death, as the story goes, he wanted to be buried in the land of his forefathers. Yet Ben Maimon would no doubt have objected to being made into an Israeli citizen after his death. More than anyone Ben Maimon symbolizes the tight connection that always has existed between Muslim and Jewish traditions. Meanwhile, the Jewish community in Cairo which as recently as in the 1920s comprised some 80,000 people has dwindled to fewer than 200 members today. There is a tradition among them that Ben Maimon’s body was never transferred to Tiberias and that he still is buried in Cairo.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/685232b7

Yet Almohad rule in al-Andalus did not last long. In 1212, at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, the Christian princes managed, for the first time, to put up a united front against them. Córdoba fell to the Christian invaders in 1236 and Sevilla in 1248. From this time onward only Granada, together with associated smaller cities such Málaga, remained in Muslim hands. Here, however, the multicultural and dynamic spirit of al-Andalus continued to thrive for another 250 years. Wisely, after Navas de Tolosa, Granada allied itself with the Christian state of Castile. Although this friendship occasionally broke down, the Emirate of Granada, as it came to be known, continued to pay tribute to Castile in the form of gold from as far away as Mali in Africa. Read more: Golden Stool of the Asante at p. 138.

Today the most visible remnant of the Emirate of Granada is the Alhambra, the fortress and palace which served as the residence of the emir. It is famous above all for its courtyards, its fountains and its roses. Yet in 1492, Granada too fell to the Christians and the last Emir of al-Andalus — Muhammad XII, known as “Boabdil” to the Spaniards — was forced out of Spain. The Christians, much as the Almohads before them, were on a mission from God, and they ruled the territories they had conquered in a similarly repressive fashion. The Alhambra Decree, issued three months after the fall of Granada, forced the non-Christian population to convert or leave. As a result, some 200,000 Muslims left for North Africa, while an equal number of Jews preferred to settle in the Ottoman Empire to the east. This was the end of Muslim rule and the end of the cultural and intellectual flourishing of southern Spain.

An international system of caliphates

The Fatimid Caliphate, 909–1171, is usually considered as the last of the four original caliphates which succeeded the Prophet Muhammad. The Fatimids were originally Berbers from Tunisia but claimed their descent from Fatimah, the Prophet’s daughter. They were Shia Muslims, which make them unique among caliphs. In 969 they moved their capital to Cairo and from there they ruled all Muslim lands west of Syria, including the western part of the Arabian Peninsula, Sicily and all of North Africa. Fatimid Cairo displayed much the same multicultural mix and intellectual vigor as the capitals of the other caliphates. The Fatimids founded the al-Azhar mosque there in 970, and also the al-Azhar University, associated with the mosque, where students studied the Quran together with the sciences, mathematics, and philosophy. Al-Azhar University is still the chief center of Islamic learning in the world and the main source of fatwas, religious rulings, and opinions.

Yet the Fatimid Caliphate was not actually an empire, if we by that term mean a united political entity that imposes its authority on every part of the territory it claims to control. Much as the other caliphates, it had barely established itself before it began to fall apart. First, the Fatimids lost power over the Berber homeland where the Almoravids and Almohads took over; Sicily was next to break off, first establishing its own independent emirate and then, in 1071, the island was occupied by Normans from France.

Kitab Rujar and the Emirate of Sicily

The Arabs did not only invade Spain but also Italy, or at least the southern Italian island of Sicily. In 831, Sicily was wrestled from the Byzantines and an emirate established here, with Palermo as its capital. It lasted, albeit in an increasingly weakened form, until 1071. Much as in Spain, the Arab occupation transformed a provincial backwater into a flourishing economic and cultural center. Land reform reduced the power of the old aristocracy and increased the productivity of agriculture; the irrigation systems were improved and the Arabs introduced new crops such as oranges, lemons, pistachios, and sugarcane. In the eleventh century, Palermo had a population of 350,000, making it the second-largest city in Europe after Córdoba in al-Andalus. In 1071, the Normans captured the island. The Normans were from northern France, and they had Viking heritage. They had started out as mercenaries working for Byzantine kings, but before long they began making war on their own behalf. Yet in sharp contrast to the situation in Spain after the Reconquista, the Normans did not try to destroy Arab Sicily. Instead, Arab scholars and artists were given new commissions and Arab bureaucrats continued to be employed by the new rulers. Visitors were astonished to learn that even the king’s own chef — a key position for anyone interested in poisoning his majesty — was an Arab. The result was a blend of Arabic, Byzantine and Norman influences which is still on display in some of Palermo’s churches.

The court of the Norman king Roger II, 1130–1154, was particularly splendid. Although its official language was French, the king spoke Arabic fluently, and the administration communicated with its subjects in Latin, Greek, Arabic, and Hebrew. People were encouraged to convert to Christianity, but Islam was tolerated. The geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi, was one of the scholars employed at Roger’s court. In 1154, after fifteen years of research, he produced the Kitab Rujar, the “Book of Roger,” a description and a map of the world. The original copy of Kitab Rujar was lost in the 1160s and the Norman court was destroyed soon after that. Next Sicily came under the power of the Catholic church. The persecution of Arabs began in the 1240s and Byzantine influences were wiped out too. By the 1330s, Palermo was once again a provincial backwater — now with only 50,000 inhabitants.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/ce76893e

In the end the caliphs were really only in control of their heartland in the Nile River Valley.

In addition, the Fatimid caliphs became increasingly dependent on mercenaries, known as mamluks, meaning “possession” or “slave.” The mamluks were bought or captured as children, often from the Caucasus or Turkish-speaking parts of Central Asia. From there they were taken to Cairo where they were housed in garrisons together with other captives, brought up in the Muslim faith and taught martial arts — archery and cavalry in particular. The mamluks served as soldiers and military leaders but also as scribes, courtiers, advisers, and administrators. As it turned out, however, it was not a good idea to give slaves access to weapons. The mamluks ousted the Fatimids and took power in Egypt in 1250. They continued to rule the country, as the Mamluk Sultanate, until 1517, when the Ottomans invaded.

Saladin and the Crusaders

Richard Coeur-de-lion, or “Lionheart,” 1189–1199, was an English king, yet he is famous above all as one of the commanders of the Third Crusade. In 1099, during the First Crusade, the Europeans had captured Jerusalem and established a Christian kingdom there. In 1187, however, the Europeans were decisively defeated at the Battle of Hattin, and Jerusalem retaken by the Muslims. It was to relieve them, and to try to get Jerusalem back, that Richard set off for the Holy Land. On his way there he occupied Sicily in 1190, Cyprus in 1191, and once he arrived he retook the city of Acre. The Europeans established a new kingdom here which was to last until 1291. Read more: Rabban Bar Sauma, Mongol envoy to the pope at p. 113. But that was as far as Richard got. The various European commanders were quarreling with each other; they lacked the soldiers and the patience required for a successful campaign. Despite repeated attempts, Richard never recaptured Jerusalem.

The person who more than anyone else stopped the Europeans was An-Nasir Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub, 1174–1193, known as “Salah ad-Din” or “Saladin.” Saladin was of Kurdish origin but had made his career with the Fatimids in Cairo where he rose to become vizier. In 1171, he turned on his employer and established a dynasty of his own, the Ayyubids, 1171–1270. It was Saladin and the Ayyubid armies that defeated the Crusaders at Hattin, took Jerusalem back, and successfully defended themselves against the onslaught of the foreigners.

Richard Lionheart and Saladin are the original “knights in shining armor.” Despite an abundance of high-quality scholarship on the Crusades it is difficult to separate facts about them from all the fiction. Walter Scott, the British author, published a highly romanticized account of their rivalry in 1825, and in the twentieth century, Hollywood has produced a number of similar versions. According to the Europeans, Richard brought Christianity and civilization to the Middle East. According to the Arabs, Saladin defended Muslim lands against a barbarian invasion. Reading and fantasizing about them ever since, political leaders both in Europe and in the Muslim world have found their respective role models.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/d34b96c8

The Mamluk sultans ran a meritocratic regime which rewarded the talented and the hardworking rather than the well-connected, but since succession did not follow a family line, the infighting at court was intense. Some rulers were in power for days rather than years and none of them slept comfortably at night. The mamluks embarked on ambitious architectural projects, constructing mosques and other public buildings in a distinct architectural style of their own.

The result was an international system with unique characteristics — perhaps we could talk about a “caliphal international system.” Instead of being an empire, each caliphate was more like a federation where the constituent parts had a considerable amount of independence from the center and from each other. The system as a whole was held together by institutional rather than by military means — by its language, its administrative prowess and by an abiding loyalty to the idea of the caliphate itself. And it was held together by religion too of course. The caliphs were religious leaders of enormous cultural authority. This applied in particular to the caliphs, such as the Fatimids, who had responsibility for the holy sites at Mecca and Medina.

In this international system there were occasional conflicts over boundaries and jurisdictions, but there were no wars of conquest. Political entities beyond the caliphate’s borders would occasionally make trouble, and military expeditions would be dispatched to punish them, yet the caliphs much preferred to control the foreigners by cultural means. For example: Baghdad would dispatch missions to the Bulgars, a people living on the river Volga in present-day Russia, in order to instruct them how to properly practice the Muslim faith.

A Viking funeral on the Volga

Ahmad ibn Fadlan was a faqih, an expert in Islamic jurisprudence, who accompanied an embassy dispatched in 921 by the Abbasid caliph to the Bulgars who lived along the river Volga, in today’s Russia. The Volga Bulgars had only recently been converted to Islam and the purpose of the mission was to explain the tenets of the faith and to instruct them in the proper ritual. This was why Ibn Fadlan came along.

The embassy encountered many interesting peoples along the way, but it is Ibn Fadlan’s account of the Vikings which is most famous. In the tenth century, Vikings from today’s Sweden relied on the rivers of Russia to travel and to trade, and their commercial contacts reached as far as Constantinople, Baghdad, and the Silk Road. Ibn Fadlan was both fascinated and horrified by these people. “I have never seen more perfect physiques than theirs,” he insisted — they are “fair and reddish” and tall “like palm trees,” and tattooed “from the tip of his toes to his neck.” Yet they were also ignorant of God, disgusting in their habits and devoid of any sense of personal hygiene.

Ibn Fadlan went on to describe a Viking funeral which he personally had witnessed. First, the dead chieftain was placed in a boat, together with his swords and possessions, then a number of cows, horses, dogs, and cockerels were sacrificed. Finally, a slave girl was dressed up as his bride and ritually raped by all the warriors. She too was placed on the funeral pyre, while the members of the tribe banged on their shields to drown out her screams. The boat was then set alight.

In 2007, a Syrian TV station produced a drama series based on Ibn Fadlan’s account. The background was the controversy stirred up when Hollands-Posten, a Danish newspaper, published cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad which many Muslims regarded as offensive. The publication led to diplomatic protests, a boycott of Danish goods and to demonstrations and rioting in several Muslim countries in which some 200 people were killed. It is easy to see why Ibn Fadlan’s account might appeal to an Arab audience of TV viewers. He was a sophisticated intellectual, of urbane tastes and refined manners, and the Scandinavians he encountered were little more than savages. The task of today’s Muslims too is to explain the true meaning of Islam to Europeans, and perhaps to Scandinavians in particular.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/0378c429

Rulers such as the Bulgars paid tribute and, as a result, the caliphates came to exercise a measure of control over far larger areas than their armies could capture.

Two external incursions temporarily wreaked havoc with these arrangements — the invasions by European Crusaders and by the Mongols. Both had come to Muslim lands from very far away indeed, and they had no respect whatsoever for Islamic civilization or for the idea of the caliphate. Both were also bent on territorial conquest. The Europeans, known to the Arabs as Faranj, from “Franks,” first arrived in the eastern Mediterranean in the final years of the eleventh century and proceeded to capture Jerusalem and what they regarded as the “Holy Land.” Read more: Saladin and the Crusaders at p. 88.

They then returned again and again as the First Crusade, 1095–1099, was followed by similar military campaigns in 1145, 1189, 1202, 1213, 1248 and 1270. The Faranj established small kingdoms on the territory of the Fatimid Caliphate, and they waged war in a barbaric fashion — the capture of Jerusalem in 1099, and the subsequent massacre of civilians, is only the most notorious example. In 1291, with the fall of the last Crusader state, the Europeans were finally defeated. As far as the Mongols are concerned, they captured and destroyed Baghdad in 1258, yet only two years later, at the Battle of Ain Jalut, they were themselves defeated and their advance stopped. Although the Mongols had been beaten before, they would always come back to exact a terrible revenge. After Ain Jalut, however, this did not happen. It signaled the beginning of the end of the Mongol Empire.

The question of why empires rise and fall preoccupied Ibn Khaldun, 1332–1406, a historian and philosopher, who worked first in Tunis, then in Cairo. It is the communal spirit of a people, he argued, which makes a state powerful. This is the spirit that causes a group, such as the Berbers of North Africa, work together even under the harshest of circumstances. Yet, once they have come to power and settled in cities, they lose their communal spirit. Instead, everyone becomes more selfish and the political leaders start fighting each other. Ibn Khaldun’s work, the Muqaddimah, published in 1377, is sometimes considered the first text on historical sociology.

Ibn Khaldun and the role of asabiyyah

Ibn Khaldun, 1332–1406, was a historian and philosopher born in Tunis in North Africa but in a family which for centuries had been officials to the Muslim rulers of Spain. By Khaldun’s time, Muslim North Africa was in decline and the once-powerful states had fragmented into a number of competing political entities. It was among these that Ibn Khaldun looked for employment. He was well-read in the Arabic classics, an expert in jurisprudence, and he knew the Quran by heart. He was, by all accounts, extraordinarily ambitious and perfectly convinced of his own intellectual superiority. He was also in the habit of plotting against his employers. The result was a life which alternatively turned him into a statesman and a prisoner.

In 1375, he took a prolonged sabbatical from his political career and settled in the Berber town of Qalat Ibn Salama, in today’s Algeria. Here he began writing what at first was meant to be a history of the Berber people but which soon turned into a history of the world, prefaced by a Muqaddimah, a “Prolegomenon,” in which he laid out his theory of history. Writing as a historical sociologist, Ibn Khaldun sought to explain what it is that makes kingdoms rise and fall. As far as the rise to power is concerned, he emphasized the role of asabiyyah, “social cohesion” or “group solidarity.” The Berbers provide a good example. They survived in the harsh conditions of the desert only because they stayed united and helped each other out. This sense of solidarity provided them with mulk, “the ability to govern,” and made them into formidable conquerors. The success of a conqueror, however, would never last long. Once in power, the asabiyyah would start to dissipate as the new rulers became rich and began to indulge in assorted luxuries. Instead of relying on the solidarity of the group, the rulers employed mercenaries to fight their wars and bureaucrats to staff their ministries. In five generations, Ibn Khaldun explained, the mulk was gone and the state was ripe for a takeover by others.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/95b70d1f

The Ottoman Empire

The empire which rose to replace the Abbasids as leaders of the Muslim world were the Ottomans. The Ottomans were Turks with their origin in Central Asia, and they spoke Turkish, not Arabic. Remarkably, the same dynasty, the Osmans, was in charge of the empire from Osman I in the thirteenth century until the last sultan, Mehmed VI, in the twentieth. Altogether there were thirty-six Ottoman sultans. Although the Turks too were Muslim and called themselves a “caliphate” — the Ottoman Caliphate, 1517–1924 — their capital was the former Greek city of Constantinople. While they ruled much of North Africa and the Middle East, they ruled much of Europe too — the Balkans in particular and large parts of eastern Europe.

First founded in 1299, the Ottoman Empire began as one of many small states on the territory of what today is Turkey. After having conquered most of their neighbors, the Ottomans moved across the Bosporus and into Europe in the early fifteenth century. Before long they came to completely surround the Byzantines — now reduced to the size of little more than the city of Constantinople itself. As far as the Byzantine Empire is concerned, it claimed a legacy that went right back to the Roman era. In the year 330 CE, emperor Constantine had moved the capital to the eastern city that came to carry his name. Rather miraculously, when the Western Roman Empire fell apart in the fifth and sixth centuries, the Eastern Roman Empire survived. Over the years Constantinople was besieged by Arabs, Persians and Russians, and in 1204 the city was sacked and destroyed by members of the Fourth Crusade. Despite these setbacks, the Byzantine Empire managed to thrive both culturally and economically.

The Byzantine diplomatic service

The Byzantine Empire, 330–1453, was originally the eastern part of the Roman Empire, where Emperor Constantine established a capital, Constantinople, in 330. When Rome was overrun and sacked by various wandering tribes, the empire survived in the east. The Byzantine Empire was to last for another thousand years and at the height of its power, it comprised all lands around the eastern Mediterranean, including North Africa and Egypt. The Byzantines spoke Greek, they were Christian, and they spread their language and their religion to all parts of the empire. An educated person in Egypt or Syria prior to the eighth century was likely to have been Christian and Greek-speaking.

An important reason for the longevity of the Byzantine Empire was its aggressive use of diplomacy. They set up a “Bureau of Barbarians” which gathered intelligence on the empire’s rivals and prepared diplomats for their missions abroad. The diplomats negotiated treaties and formed alliances and spent much time making friends with the enemies of their enemies. Foreign governments were often undermined by various underhanded tactics. For example: in Constantinople, there was a whole stable of exiled, foreign, royalty whom the Byzantines were ready to reinstall on their thrones if an occasion presented itself.

Constantinople was thoroughly sacked by the participants in the Fourth Crusade in 1204, an event which left bitter resentment and strong anti-Catholic feelings among all Orthodox Christians. In the thirteenth century, the Turks began expanding into the Anatolian peninsula, and eventually, the once vast Byzantine Empire came to comprise little but the capital itself and its surrounding countryside. Constantinople fell to the Turks in 1453 and the large cathedral, Hagia Sophia, was turned into a mosque. The fall of Constantinople is still remembered as a great disaster by Greek people while Turks celebrate it as ordained by Allah and foretold by the Prophet Muhammad himself.

“Byzantine” is an English adjective which means “devious” and “scheming” but also “intricate” and “involved.” Learning about the diplomatic practices of the empire, it is easy to understand why. But then again, their diplomacy served the Byzantines well.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/8fb10ad6

However, in May 1453, after a seven-week-long siege, Constantinople fell to the Ottomans, led by Sultan Mehmed II, henceforth known as “Mehmed the Conqueror.” The city was renamed “Istanbul,” and the famous cathedral, Hagia Sophia, was turned into a mosque. The defeat was met with fear and trepidation by Christians all over Europe and it is mournfully remembered by Greek people to this day.

Even as Constantinople was renamed “Istanbul,” it continued to be a cosmopolitan city. In the Ottoman Empire, much as in the Arab caliphates which preceded it, the dhimmi enjoyed a protected status. Known as the millet system in Turkish, the Ottoman Empire gave each minority group the right to maintain its traditions and to be judged by its own legal code. It was policies such as these that convinced many Jews to settle here after the Christian occupation of Muslim Spain in 1492. To this day there are Spanish-speaking Jews in the former parts of the Ottoman Empire. Moreover, the city’s strategic location at the intersection of Europe and Asia was as beneficial to Ottoman traders as it had been to the Byzantines. The state manipulated the economy to serve its own ends — to strengthen the army and to enrich the rulers — yet the administrators employed for these purposes were highly trained and competent. The state-sponsored projects which the Ottomans embarked on, such as the construction of roads, canals and mosques, helped spur economic development. The empire was prosperous and markets for both consumer items and fashion were established.

Tulipmanias

At the beginning of 1637, a madness seems to have overcome the Dutch. Everyone was buying tulips and the price of tulip bulbs was skyrocketing. Even the most casual of daily conversations would refer to the prices for various strains, hybrids, and colors. For a while, one single bulb was selling for more than ten times the annual income of an ordinary laborer. In the rising market, extraordinary wealth could be accumulated in a matter of days. Soon what was bought and sold was not the tulips themselves, but the right to buy or sell tulips at a certain price at a future date. The Dutch were seized by “tulipmania.”

Today we may associate tulips with Holland, but originally the flower grew wild in Anatolia, in today’s Turkey. In 1554, the first bulbs were sent from the Ottoman Empire to Vienna and from there the flower soon spread to Germany and the Dutch Republic. The first attempts to grow tulips took place in Leiden in 1593 and it turned out that the flower survived well in the harsher climate of northern Europe. Soon tulips became a status symbol for members of the commercial middle classes. The flower was not only beautiful and unusual but, given the Ottoman connection, also very exotic. When commercial cultivators entered the market, prices began to rise. This was where the speculation in the tulip market began.

The “Tulip Period” is the name commonly given to the short era, 1718–1730, when the Ottoman Empire began orienting itself towards Europe. It was a time of commercial and industrial expansion and when the first printing presses were established in Istanbul. In the Ottoman Empire too there was a tulip craze. In Ottoman court society, it was suddenly very fashionable to grow the flower, to display it in one’s home and to wear it on one’s clothes. The tulip became a common motif in architecture and fabrics. In the Ottoman Empire too, prices of bulbs rose quickly and great fortunes were made and lost. This was the first commercialized fad to sweep over the caliphate and the beginning of modern consumer culture.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/740ed361

The Ottomans continued to enjoy military success. Selim I, 1512–1520, established a navy which operated as far away as in the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf. He defeated both Persia and the mamluks in Egypt, dramatically expanding an empire that came to include the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. It was then that the sultans began calling themselves “caliphs,” implying that they were the rulers of all Muslim believers everywhere. Suleiman I, known as “the Magnificent,” 1520–1566, continued the expansion into Europe. He captured Belgrade in 1521 and Hungary in 1526, and laid siege to Vienna in 1529, but failed to take the city. The Ottoman army responsible for these feats was quite different from the European armies of the time. Like other armies with their roots in a nomadic tradition, they relied on speed and mobility to overtake their enemies but the Ottoman armies were also one of the first to use muskets. During the siege of Constantinople they used falconets — short, light cannons — to great effect. More surprisingly perhaps, the Ottomans had a powerful navy which helped them unite territories on all sides of the Mediterranean. The Ottoman army, much as armies elsewhere in the Muslim world, relied heavily on foreign-born soldiers.

Janissaries and Turkish military music

The janissaries were the elite corps of the Ottoman army, independent of the regular troops and responsible directly to the sultan himself. In a practice known as devşirme, or “gathering,” the Ottomans would periodically search Christian villages in the Balkans for young boys whom they would proceed to abduct. The boys were taken to the Ottoman Empire, taught Turkish, circumcised and given a Muslim education. The great advantage for the sultans was that these men had no families and their only loyalty was to the sultan himself. By relying on the janissaries to carry out the key functions of the state, it was possible to sideline the traditional nobility. The janissaries were used, to great effect, in all military engagements, including the siege in 1453 when Constantinople was captured. During the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, 1520–1566, there were some 30,000 janissaries employed by the Ottoman state.

Initially, the janissaries were not allowed to marry or to own property. They lived together in garrisons where they practiced various martial arts and socialized only among themselves. They wore distinct uniforms and were required to grow mustaches but not allowed to grow beards. From the seventeenth century onward, however, they became powerful enough to change many of these rules. The practice of devşirme was discontinued in the seventeenth century, mainly since the existing janissaries did not want competition from outsiders.

The janissaries had their own distinct form of music, known as mehterân. When marching off to war they would bring their musicians with them. The shrill ululations of the zurna, a sort of oboe, struck a fearful mood in the enemy much as the davul drums made the janissaries more courageous. Impressed by these effects, European armies too began making use of military bands. Turkish military music suffered when the janissaries' corps was abolished in 1826, but the tradition has recently been revived.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/4a6911c2

In the case of the Ottomans too, these former slaves eventually established themselves as rulers in their own right. This is how the Ottoman provinces of Egypt, Iraq and Syria came to assume an increasingly independent position, each ruled by its own military commanders.

The Ottomans were skillful diplomats. Despite the official Christian fear of the Turks, the Ottoman Empire was, after 1453, a European power and as such an obvious partner in both alliances and wars. This was particularly the case for any European power that opposed countries which were also the enemies of the Turks — such as the Habsburg Empire and Russia. The French, for example, quickly realized that the Ottomans constituted a force that could be convinced to attack the Habsburgs from the south. During the Thirty Years War in the seventeenth century, the king of Sweden drew the same conclusion. And much later, in the 1850s, Great Britain and France relied on Turkey as an ally in waging war against Russia in the Crimea. At the Congress of Paris, 1856, which concluded the Crimean War, the Ottoman Empire was officially included as a member of the European international system of states.

Yet for much of its later history, the empire was in decline. Economically it suffered when international trade routes, from the sixteenth century onward, were directed away from the Mediterranean. Together with the rest of Eastern Europe it suffered again when, in the nineteenth century, the western parts of Europe began to industrialize and cheap factory-made goods began flooding in. The failed siege of Vienna in 1683 — the second time the Ottomans tried to take the city — is often seen as the symbolic start of the decline. The Ottomans held the city ransom for some two months, during which food was becoming exceedingly scarce and the Austrians increasingly desperate.

Coffee and croissants

All coffee comes originally from Ethiopia where the coffee tree grows wild. By the fourteenth century, the tree was cultivated by the Arabs and exported from the port city of Mocha in today’s Yemen. But it was only once the Ottomans occupied the Arabian peninsula in the first part of the sixteenth century that the habit of coffee drinking really took off. The first coffeehouse opened in Istanbul in 1554, and before long sipping coffee, eating cakes and socializing became a fashionable pastime. From the Ottoman Empire, the coffee-drinking habit was exported to the rest of Europe, together with the word itself. “Coffee” comes from the Turkish kahve, and ultimately from the Arabic qahwa. The first coffee shop opened in Venice in 1645, in London in 1650 and in Paris in 1672.

Vienna has its own and quite distinct café tradition. The Viennese drink their coffee with hot foamed milk and, just as in Turkey, it is served with a glass of cold water. The first coffeehouse in Vienna was opened by a man called Jerzy Franciszek Kulczycki, a Polish officer in the Habsburg army. Since Kulczycki had spent two years as a Turkish prisoner of war, he was well acquainted with the habit of coffee drinking and was quick to spot a business opportunity. Every year, coffeehouses in Vienna used to put portraits of Kulczycki in their windows in recognition of his achievements.

There is a legend that the croissant — the flaky, crescent-shaped pastry that French people, in particular, like to eat for breakfast — first was invented during the siege of Vienna. According to one version of the story, the Ottomans were trying to tunnel into the city at night, but a group of bakers who were up early preparing their goods for the coming day heard them and sounded the alarm. The croissant, invoking the crescent shape so popular in Muslim countries, was supposedly invented as a way to celebrate the victory. Unfortunately, however, this story cannot possibly be true. Baked goods in a crescent shape — known as kipferl in German — were already popular in Austria in the thirteenth century.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/63788023

In the end the Ottomans were decisively defeated, losing perhaps 40,000 men. And before the seventeenth century came to a close they had lost both Hungary and Transylvania to the Austrians. In the nineteenth century, the Ottoman Empire became known as “the sick man of Europe.” A number of administrative reforms were tried during this period. After the revolt of the so-called “Young Turks” in 1908 — a secret society of university students — the Ottoman Empire became a constitutional monarchy in which the sultan no longer enjoyed executive powers. The Ottoman Empire ceased to exist in 1922, the Republic of Turkey was founded in 1923, and the caliphate was officially abolished in 1924.

|

|

|

|

Adamson, Peter. Philosophy in the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016. |

|

|

Bauer, Susan Wise. The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade. New York: WW Norton & Co., 2010. |

|

|

Bennison, Amira K. The Great Caliphs: The Golden Age of the ’Abbasid Empire. London: I. B. Tauris, 2009. |

|

|

Casale, Giancarlo. The Ottoman Age of Exploration. New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. |

|

|

Faroqhi, Suraiya. The Ottoman Empire and the World Around It. London: I. B. Tauris, 2006. |

|

|

Gutas, Dimitri. Greek Thought, Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early ’Abbasaid Society. London: Routledge, 1998. |

|

|

Jayyusi, Salma Khadra, ed. The Legacy of Muslim Spain. Leiden: Brill, 2000. |

|

|

Menocal, Maria Rosa. The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain. Boston: Back Bay Books, 2003. |

|

|

Ramadan, Tariq. Introduction to Islam. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017. |

|

|

Starr, S. Frederick. Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia’s Golden Age from the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013. |

Timeline

|

632 |

Death of the Prophet Muhammad in Medina. |

|

657 |

The First Fitna or Muslim civil war is fought between groups which later would become Sunni and Shia. |

|

661 |

The Umayyad Caliphate is established in Damascus. |

|

711 |

Arabs cross into Spain at Gibraltar. |

|

732 |

The Battle of Tour in central France. The Muslim forces are defeated. |

|

750 |

The Umayyads are defeated in the Second Fitna. The Abbasid Caliphate is founded and takes Baghdad as its capital. |

|

929 |

The Caliphate of Córdoba is established by a branch of the Umayyad family. |

|

969 |

Cairo is founded by the Fatimid Caliphate. |

|

1031 |

Fall of the Caliphate of Córdoba. |

|

1212 |

Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa where a coalition of Christian kings defeats the Almoravids. |

|

1258 |

The Mongols destroy Baghdad. |

|

1453 |

The Ottomans capture Constantinople and rename it “Istanbul.” |

|

1492 |

Granada falls and the last Muslim ruler leaves for North Africa. |

|

1683 |

The Ottomans besiege Vienna but fail to take the city. |

|

1922 |

The Ottoman Empire is dissolved. |

Short dictionary

|

asabiyyah, Arabic |

“Solidarity,” or “group cohesion.” A term used by Ibn Khaldun to explain the military and political success of nomadic peoples like the Berber. |

|

devşirme, Turkish |

“Ingathering.” The Ottoman practice of kidnapping young boys, mainly in the Balkans, who were brought up as servants of the state. The practice was abolished in the first part of the eighteenth century. |

|

dhimmi, Arabic |

Literally, “protected person.” Designated non-Muslim residents of a Muslim caliphate. Equivalent to the Turkish millet. |

|

Faranj, Arabic |

Literally, “Frank.” “European.” Name given to the waves of armies from Europe who invaded the Middle East from the eleventh to the thirteenth century. Cf. the Thai farang and the Malay ferenggi. |

|

fatwa, Arabic |

A legal opinion on a point of Islamic law given by a legal scholar. |

|

fitna, Arabic |

Literally, “sedition,” “temptation” or “civil strife.” The name given to wars fought between various Muslim groups. |

|

hajj, Arabic |