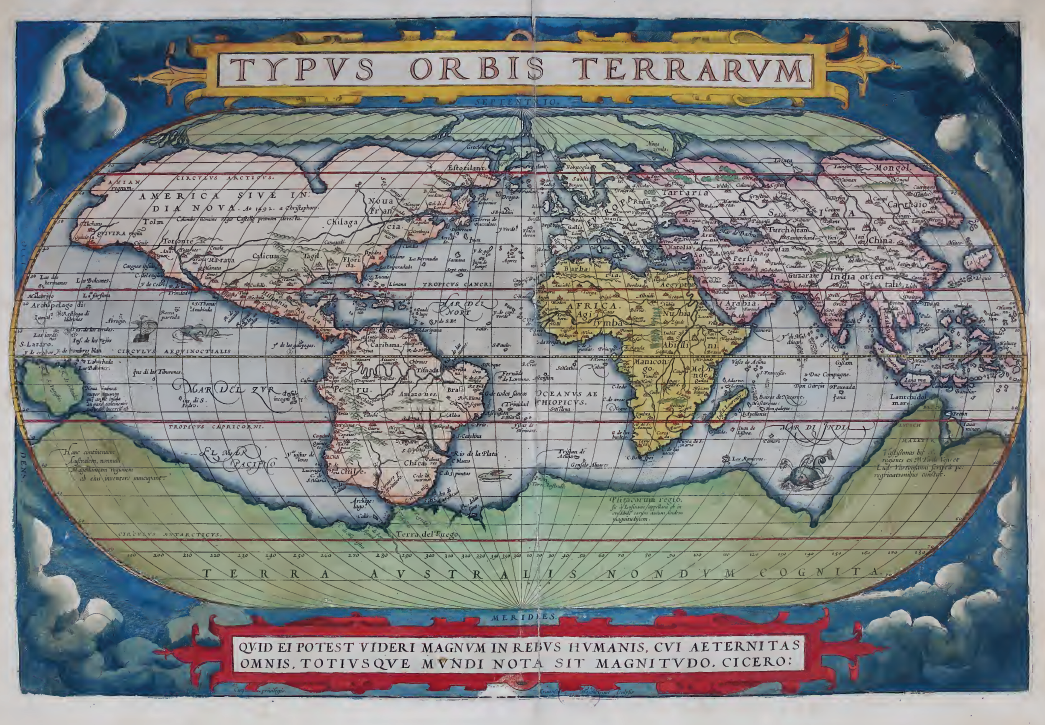

Map of the world from Abraham Ortelius, Theatrum orbis terrarum (Antverpiae: Apud Aegid. Coppenium Diesth, 1570), p. 26, https://archive.org/details/theatrumorbister00orte

8. European Expansion

© 2019 Erik Ringmar, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0074.08

A study of comparative international systems is by definition a historical study. There are no separate international systems to compare anymore. There is only one system — the system which first made its appearance in Europe in the late Renaissance, and which later came to spread to every corner of the globe. But “spread” is not the right word. This was not a matter of a process of passive diffusion. Rather, the eventual victory of the European international system was a result of the way the Europeans first came to “discover” and later to occupy and take possession of most non-European lands. This is a story of imperialism and colonialism. In this, the final chapter of the book, we will tell the story of how Europe for a while at the turn of the twentieth century came to rule the world.

For most of its history Europe had quite a peripheral position in relation to everyone else. Europe was an international system turned in on itself, confident in its own culture and largely uninterested in what was going on elsewhere. Moreover, outsiders made only occasional forays into Europe — like the Berber kingdoms in the eleventh and twelfth centuries and the Mongols in the thirteenth century. What these outsiders found were a few impressive cathedrals, the occasional castle, but also a lot of desperately poor people, serfs without much food and without education. Before the year 1500, no European city was a match for the splendors of Baghdad, Xi’an, Kyoto or Tenochtitlan.

Yet Europe eventually did become rich, powerful and important, and it came to have a profound impact on the rest of the world. In the first half of the fifteenth century, Europeans began to embark on sea voyages which took them down the western coast of Africa, and eventually far further afield. Here they discovered a number of commodities which found a ready market back home. Before long the Europeans began looking for new goods and for opportunities to trade. The commercial activities transformed Europe’s economy and enormously strengthened the institutional structure of the state. It was at this point that the Europeans established their first permanent colonies overseas. In some areas, such as in the Americas, Europeans settled permanently, but in Asia they mainly established small trading posts.

Beginning at the end of the eighteenth century, the development of an industrial economy based on mechanical production in factories radically changed European societies, making them “modern.” Modernization entailed changes in almost all aspects of social, economic and political life — often analyzed as a question of “urbanization,” “industrialization,” “democratization,” etc. As far as the rest of the world was concerned, the modernization of Europe had a number of far-reaching consequences. The Europeans needed raw materials for the goods they were producing and often these resources could be found outside of Europe itself. Moreover, European producers needed to find more people who were prepared to buy all the things their factories were spewing out. The hope was that these consumers could be found in India, for example, or in China. And as people outside of Europe were to discover, the industrial revolution had given the Europeans access to far more lethal weapons than ever before. Armed with these new incentives, and these new guns, the Europeans set out to conquer the world.

A sea route to India

Europe’s isolation came to an end in the thirteenth century when the first sustained contacts were established with East Asia. During the Pax Mongolica, the “Mongol peace,” European merchants and the occasional missionary traveled as far eastward as China. Read more: Dividing it all up at p. 112.

The Europeans were amazed at the wealth of the countries they discovered here, the power of their rulers and all the curious objects which no one in Europe knew anything about. Returning home they would tell tales of their wondrous adventures. The objects they brought with them — spices, tea, precious stones, china, silk and so on — embodied these mysteries and for that reason alone they were highly sought after. This was not least the case for members of the elite who derived power and prestige from buying and displaying these exotic objects. There was, European merchants discovered, a lot of money to be made for those who could satisfy this market. It was the Italians who took the lead — the Venetians and Genovese in particular. Marco Polo, the most famous among them, was a Venetian.

Did Marco Polo go to China?

In 1271, the merchants Niccolò and Maffeo Polo left their native city of Venice and set sail for the east. The two brothers had already done business in Constantinople and in the Crimea, and they had visited the lands of the Mongols. When they had returned to Europe in 1269, they carried a message from Kublai Khan to the Pope in Rome. Having delivered the letter, they were now on their way back to Asia. They had a paiza with them, a small tablet in gold, which gave them free passage, lodgings, and horses throughout Mongol lands. With them, as they left Venice, was Niccolò’s son Marco, who was seventeen years old at the time.

Marco Polo was to find particular favor with the Great Khan who made him an official at his court. He learned to speak Mongolian together with several other languages and he traveled around the vast empire visiting lands which no European had previously seen. His account of the splendors of the khan’s palace is particularly famous, together with his description of Kinsay, today’s Hangzhou. The Polos came back to Venice as wealthy men and the many stories Marco told about his adventures amazed everyone who heard them. The stories of his travels were collected in Il Milione, a title that either derived from Polo’s nickname, “Emilione,” or from the millions of marvellous tales the book contained.

Yet it may be that Marco Polo never actually visited China. It is striking, for example, that he never mentions Chinese customs such as foot-binding or tea-drinking, and it is strange that place-names are consistently given in Persian rather than in Mongol or Chinese. This is not, however, a reason to dismiss the text. Despite its omissions and mistakes, the account of Polo’s travels contains many details which we know from other sources to be correct. Marco Polo’s book — or the book associated with a person by that name — had a tremendous impact on European readers, stirring up elaborate fantasies of the exotic East. The most famous reader was Christopher Columbus, who had his own copy of the book on which he had scribbled extensive notes in the margins.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/943e5744

Yet trade with the East was a perilous business. Goods traveled slowly on camelback across the caravan routes of Central Asia, where there were a number of things that could go wrong — robbers could attack, officials could interfere, and then there was the inclement weather and the turn of the seasons. As long as the Mongol Empire lasted it was possible to deal with these challenges, and the profits remained high. The Mongol khanates had not always been at peace with each other, but they understood the value of commerce and they did what they could to encourage it. Yet, with the end of the Pax Mongolica in the fourteenth century, both the risks and the costs associated with the caravan trade rose dramatically. The new rulers who appeared about halfway between Europe and East Asia wanted their cut of the profits. Both the Ottomans and Mamluk Egypt put up customs and tariffs which made it far more expensive to trade.

In response, the Europeans began looking for alternative ways to reach East Asia. They tried their luck by ship. One idea was to go down the west coast of Africa and find a passage to India that way. Once these attempts proved successful, trade moved away from the Mediterranean, away from Italy, and to the countries along Europe’s Atlantic coast. Here Portugal took the lead, soon followed by Spain, although the Spanish, at least to begin with, continued to rely on the services of Italian sea captains. The most famous of these, Cristoforo Colombo, “Christopher Columbus,” had the idea that it should be possible to travel to India by going westward, straight into the Atlantic Ocean. He did not find India this way, but he found a new world — a Mundus novus — of which no one in the old world had had any previous knowledge. Eventually the new world came to be known as “America,” named after Amerigo Vespucci, another Italian sea captain.

Prior to the Middle Ages, Europeans had not shown much interest in the world outside of their continent, as we said before, but there were two exceptions. First of all there were the Vikings of Scandinavia. The Vikings traveled far and wide. Vikings from what today is known as Sweden went eastward along the large rivers of Russia until they came into contact with the Byzantine Empire and the Abbasid Caliphate. Read more: A Viking funeral on the Volga at p. 89. Meanwhile Vikings from what today is Denmark and Norway went westward, exploring first Iceland, then Greenland and finally what they called Vinland, that is today’s “North America.” Columbus was not the first European to set foot in the Americas.

The second exception concerns the military campaigns known as the “Crusades.” To some Europeans — notably a few militant Popes — it was unacceptable that lands mentioned in their religious scriptures, and which before the Arab expansion had been predominantly Christian, now were in Muslim hands. The idea was to equip a pan-European army which could win them back. Altogether seven major Crusades were organized between 1096 and 1254, in which hundreds of thousands of Europeans took part. For a while the Crusaders were quite successful. They conquered Jerusalem in 1099 and managed to establish small kingdoms throughout the eastern Mediterranean. Yet at the Battle of Hattie in 1187, the Crusaders were decisively defeated by the armies of the Fatimids, the caliphate with its base in Cairo. Read more: Saladin and the Crusaders at p. 88. Although the Europeans gathered their forces for several more Crusades, they never achieved their ends.

Wars on behalf of the Christian religion continued on the fringes of Europe, both in Eastern Europe and in Spain. Lithuania was converted to Christianity in 1386 by means of armies consisting of so-called “Teutonic knights,” a military but also a religious order. In Spain, a project — the Reconquista — was undertaken to invade al-Andalus. Read more: The Arabs in Spain at p. 81.

In 1212, the Christian coalition won an important battle at Las Navas de Tolosa, yet it would take another 250 years before the Iberian Peninsula was fully under Christian occupation. The last Muslim ruler — Muhammad XII of Granada, known to the Spaniards as “Boabdil” — was expelled in 1492, the same year that Columbus made his first journey across the Atlantic. The Christian victory severed seven-hundred-year-old links between southern Spain and the centers of civilization in the East. They also forced both Muslims and Jews to convert to Christianity on pain of death or expulsion.

Europeans in the “New World”

This was when the Europeans came to divide the world between them. Or rather, when it was divided by the Pope in Rome and given to Portugal and Spain.

Treaty of Tordesillas, 1494

In 1494, representatives of the crowns of Portugal and Spain met to divide the world between them. At the Treaty of Tordesillas, Portugal was given everything west of a meridian running between the Cape Verde Islands in the mid-Atlantic and the new lands which Columbus had discovered. The other, eastern, side of the world was divided by the Treaty of Zaragoza in 1529, along a meridian that mirrored the one agreed on in Tordesillas. On both occasions, the pope in Rome was involved. It was God who had given the earth to mankind, after all, and only his representative had the authority to approve of a division of it. The treaty is one of the first examples of how a science invented in Europe — cartography — could be used as a means of controlling the world.

From now on what amounted to the center of the world belonged to Portugal and the peripheries belonged to Spain. Thus, Africa, the Indian Ocean, and Brazil fell to the Portuguese, whereas Spain received the remainder of the Americas but also, for example, the Philippines. This is why people to this day speak Portuguese in Brazil, but Spanish in Mexico and Peru. Spain and Portugal respected this agreement fairly conscientiously; other European countries, however, did not. When the Dutch Republic and England took over much of world trade in the seventeenth century, the Treaty of Tordesillas became irrelevant.

The Treaty of Tordesillas was the first time that European powers met to divide the world between them in an orderly and civilized fashion. In the nineteenth century, Africa and China were divided in much the same way. Read more: The Berlin Conference at p. 195. At the end of the Second World War, the United States and the Soviet Union met to determine each other’s respective “spheres of influence.” On none of these occasions were the inhabitants of the partitioned territories asked for their opinion.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/f28aa9c7

For many Spaniards — the soldiers known as conquistadors — the wars in the Americas were simply an extension of the wars which they already had fought in Spain. Neither Arabs nor “Indians” were Christian and just like the Arabs, the Indians were enemies to be defeated. Hernán Cortés and his men marched into Tenochtitlan in 1519, and Francisco Pizarro’s army captured Cuzco in 1533. Despite their awesome power, both the Aztecs and the Incas turned out to be surprisingly easy to conquer, and in both cases, the Spaniards took control by means of only a few hundred men. In fact, both empires consisted of loose coalitions made up of many different political entities, and some of these subjects were quite happy to side with the Europeans. Although the Incas eventually regrouped and organized a military resistance, it was far too little, too late. Their last stronghold fell in 1572.

What the Europeans more than anything were looking for in the New World was gold. Columbus’s own descriptions of his discoveries contained endless references to how much gold the new continent contained. This, he knew, was the best way to get European kings to back more voyages of exploration. Although the Europeans indeed did find some gold, they found even more silver. In fact, there was a mountain — Potosí in Peru — which was said to be made entirely of silver.

A mountain of silver

In a remote, dry and cold part of the high Andes, in today’s Bolivia, there is a mountain which the Incas knew as Sumaq Urqu, “beautiful mountain,” and the Spaniards called Cerro Rico, “rich mountain.” As the Incas had already discovered, the mountain was enormously rich in silver, the richest in the world. When the Spaniards began extracting the ore in 1545, a town, Potosí, was established there. By the seventeenth century, it had grown to include some 200,000 inhabitants, over thirty churches, and many palaces, theaters and boulevards. This was where the crown of Spain minted its money. Yet the mines relied on slave labor and the working conditions were atrocious. Hundreds of thousands of miners died of exhaustion and disease.

It was the silver from Potosí which paid all of Spain’s debts, financed its armies and churches in Europe and allowed the country to go on “shopping sprees” in Asia. First, the silver was transported by llamas to the Pacific coast, then shipped to Acapulco in Mexico, and from there on to Europe. Before long the Spaniards began shipping silver across the Pacific too, to Manila in the Philippines, where it was used to pay off their Chinese creditors. It was silver from Potosí which more than anything provided the means of payment that enabled the creation of a world market. Spanish coins — the famous peso de ocho, “pieces of eight” — were a universal currency accepted everywhere in the world. The symbol stamped on the coin — “$,” the dollar sign — has come to symbolize money ever since.

However, the windfall had disastrous long-term consequences for the Spanish economy. Since the silver from Potosí allowed them to buy whatever they wanted, Spain failed to develop a domestic industry. And when the silver boom was over and the colonies declared independence, Spain had nothing left. The country was now poor because it once had been so rich. There is still some silver left in Sumaq Urqu and today it is mined by collectives of miners. Yet the working conditions have hardly improved since the sixteenth century. It is dirty, dangerous work, and few of the miners live beyond the age of forty-five.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/eba42922

In the end, the European occupation of the Americas resulted in genocide. Some indigenous people were killed in military confrontations, many were worked to death in mines or on plantations, but the vast majority of people died as a result of exposure to European diseases like smallpox and measles. These illnesses had long existed in Europe, and the Europeans had adapted to them, but to the people of the Americas they were deadly. It is estimated that perhaps 80 percent of the indigenous population of South, Central and North America perished as a result. This was equal to tens of millions of people. The impact on the population of the Americas was consequently far worse than the impact of the Black Death on Asia and Europe. Read more: The Black Death at p. 119.

As a result, there were not enough indigenous people who could do the physical labor involved in exploiting the natural wealth of the continent. In response, the Europeans began importing slaves from Africa, often sold to them by West African kingdoms. Read more: Dancing kings and female warriors of Dahomey at p. 139.

From the sixteenth century to the nineteenth some 12 million African slaves were forcibly transported across the Atlantic Ocean. Although both the U.S. and Britain officially outlawed the importation of slaves as early as 1807, the international trade in slaves was banned only in the 1830s, and slavery itself was finally abolished in the United States in 1865 and in Brazil not until 1888.

Not only were germs and human beings exchanged, however, but also a wide range of plants, fruits, and animals. Read more: The Columbian exchange at p. 156.

Since life on the American continent had evolved independently of the rest of the world, it had developed a wide range of unique species. There were also many species that only existed elsewhere in the world. Through global trading networks these plants, fruits and animals soon spread far and wide.

Carl von Linné names the world

Carl Linnaeus, 1707–1778, or “Carl von Linné” as Swedes call him, was the botanist who came up with the Latin names for all plants and animals. In fact, they were not only named by him but organized into a system — a Systema naturæ, to give the title of his most famous work, published in 1735 — in which every living thing found its proper place. In this system, all species could be related to each other, even those that had not yet been discovered. Linné’s system of nature had a universal scope. In order to put names into the many empty grids, Linnaeus traveled around Sweden looking for plants, but he also dispatched his students — often referred to as his “disciples” — to find new plants in the most remote corners of the globe.

Linnaeus believed botany should serve the interests of the nation. In particular, he found it an outrage that Swedes spent their hard-earned money on tea from China. “We are sending silver to the Chinese and all we get in return are dry leaves!” Thus, when one of his disciples one day returned from China with a tea bush, Linné was very excited and devised a plan to start a tea plantation. “Imagine how rich the country would be if we never have to trade with foreigners!” Unfortunately, however, the bush died when exposed to the harsh Swedish winter.

Carl von Linné may have been a great botanist, but he, together with almost all of his contemporaries, did not understand much about political economy. The wealth of a nation, as Adam Smith was later to explain, consists of what the country can produce, and Sweden cannot produce tea. It is much better to let the Chinese produce tea and for Swedes to produce what they are comparatively better at producing — cars, for example, or flat-pack furniture. By focusing on their respective advantages, and by trading with each other, the wealth of both China and Sweden will be maximized. Smith, in the Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, provided the intellectual rationale for a global market in which there are no borders and no customs duties.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/718b8209

As far as North America is concerned, it was originally settled by the Dutch, the English, and the French, but eventually it was English settlers who came to dominate. A substantial proportion of the first settlers were members of various religious minorities — the so-called “Puritans” — who took refuge there after the English Civil War, 1642–1651. They called it “New England.” In North America too, European germs quickly wiped out entire populations. This was why the land looked empty and unoccupied when subsequent waves of Europeans arrived. The Europeans referred to it as terra nullius, Latin for “nobody’s land.” Land which did not belong to anyone, the Europeans argued, was there for the taking. It was God’s will that they should take charge of the New World. And take charge they did.

The Mayflower

In 1620, a ship, the Mayflower, transported 102 passengers from Plymouth, England, to what was to become the Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts, New England. A majority of the people on board were Puritans, members of a strict Protestant denomination who were persecuted in Europe. Yet they arrived too late in the season to plant crops and, the story goes, they survived only because of the help they received from the natives. The following year, after their own first harvest, they held a “thanksgiving,” a ritual meal that is commemorated by Americans to this day.

The reason they survived the first winter, it turns out, was not that they were given food by the natives, but rather that they stole it. One of the Puritans, William Bradford, who chronicled the event, describes how they ransacked houses and dug up native burial mounds looking for buried stashes of corn. “And sure it was God’s good providence that we found this corn, for else we know not how we should have done.” Far greater devastation was caused by European diseases. Thomas Morgan, another early settler, recalled that the hand of God “fell heavily upon them, with such a mortall stroake that they died on heapes as they lay in their houses.” Yet this too, the settlers decided, was a result of the foresight of the Christian God who had made the land “so wondrously empty.” “Why then should we stand starving here for places of habitation… and in the meantime suffer whole countries, as profitable for the use of man, to lie waste without any improvement?”

People in the United States think of the passengers on the Mayflower as the first Americans. Those who can claim descent from one of them consider themselves as uniquely American. There are today some 10 million people who can make that claim.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/c95ed1c4

A commercial world economy

In a sense the European discovery of the Americas was something of a distraction. After all, it was to East Asia that the Europeans wanted to go. From this perspective the year 1498 is more important than 1492. It was in 1498 that the Portuguese sea captain Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope, on the southernmost tip of Africa, and started making his way up Africa’s eastern coast. Here the Europeans met traders from Oman, Yemen and Gujarat; in fact, if the Europeans only had arrived half a century earlier, they would have met Chinese traders here too. Read more: A giraffe in Beijing at p. 25.

Benefiting from the monsoon winds, da Gama arrived in Kerala in southern India in May 1498, and from there Portuguese ships soon started exploring other ports around the Indian Ocean. This is how the Europeans came into contact with the “spice islands,” the vast archipelago in today’s Malaysia and Indonesia where assorted exotic spices were grown. The Europeans soon developed a taste for nutmeg, cloves, cardamom, black pepper and mace — which all helped to bring flavor to the notoriously bland European diet. Before long European ships had continued into the Pacific Ocean too, traveling northward to China and Japan. The Portuguese established trading depots in Goa in India in 1510; Malacca in Malaysia in 1511; and in Macao in China in 1557. These were not colonies, only ports where they could trade with the locals, store goods and repair their ships.

The Portuguese were soon followed by the Spanish. In 1565, conquistadors from Mexico sailed to the Philippines where they established a colony known as the “Spanish East Indies,” with Manila as its capital. The Spanish visited Taiwan too, and southern China. The Spanish economy at the time was actually quite underdeveloped, yet their discovery of silver in the Americas allowed them to ignore this fact. The silver also provided a way around a problem that had always plagued European trading relations with the East: there was so much they wanted to buy from the Asians, but next to nothing that the Asians wanted to buy from them. Once silver started flowing from the Americas, however, the Europeans could suddenly buy anything they wanted. This infusion of cash caused a boom in international trade, bringing great wealth both to China and India. Before long the Spanish did not even bother to send the silver to Europe first, but instead sent it directly across the Pacific Ocean, straight to their Asian creditors.

More than the Spanish, however, it was the Dutch who came to copy the Portuguese. The Dutch also became their greatest rivals as international merchants. The Dutch lived in a republic, and officially they had no imperial ambitions, but they were very keen on trade. It was in Holland, in 1602, that the first truly multinational company — the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the Dutch East India Company — was established. The VOC, as it was known, expanded the markets for the products which the Portuguese had discovered and connected all parts of the world into one global marketplace. Similar trading companies were soon established all over Europe. Read more: De Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie at p. 34.

The European states benefited greatly from the trade with the East. The seventeenth century was a time when European rulers increasingly came to call themselves “sovereign,” meaning that they had pretensions to exercise supreme authority within the territory which they took to be theirs. In order to give credence to this rather extravagant claim, the kings needed resources, and this is what the trade with East Asia supplied. For one thing, each trading company was given a monopoly on trade with a particular part of the world. Or rather, these monopolies were sold by the kings and thus constituted a good source of revenue for them. Soon the kings could also borrow money from the trading companies. Making fabulous profits, they had surplus cash which they needed to invest. The kings of France were notorious for defaulting on these loans, but the kings of England were less extravagant. This is how the Bank of England and similar financial institutions came to be established. Eventually the City of London became the leading center of international finance.

The development of these global trading networks had a profound impact on the world economy and it was to have political implications too — involving European countries in colonization and empire building. Yet in Asia, Europe’s position was nothing like their position in the Americas. The Dutch established a colony, Batavia, in Indonesia, and the Spanish occupied the Philippines, but there was no way for the Europeans to successfully wage war on the powerful kingdoms of the East. China, India, Japan, Siam, the Mughal Empire, Persia and the Ottomans were far too rich and powerful, their armies too strong, and the Europeans were far too few in numbers. Portuguese traders had established a powerful grip on commerce in the Indian Ocean, ending the tradition of free competition and free trade, but this was not something that worried the rulers of Asia. The Europeans, much as in the Middle Ages, continued to be awestruck by the wonders of the East, and the eastern empires were greatly admired for their wealth and power.

The Seven Years’ War, 1756–1763, is the world war few people have heard about. It was fought in Europe — between Britain and France and their respective allies — but the war spread to other continents too. The conflict was particularly fierce in North America where both Britain and France had established communities of settlers and had strong commercial interests. The Seven Years’ War was intensely fought in India too where the settlers were fewer in numbers, but the commercial interests at least as strong. In both cases the conflicts concluded with victories for Britain. One long-term consequence of the wars in Europe was that the European settlers came to make themselves more independent of their home governments. In fact, relations between the European settlers and their motherland had always been complicated. The Spanish government had, for example, tried to keep some order in the empire and sought to stop the conquistadors from mistreating the natives. Yet the conquistadors were scornful of such policies and they resented Madrid’s meddling in what they regarded as their own affairs. When Spain itself was occupied during the Napoleonic Wars, 1808–1814, the settlers saw an opportunity to assert themselves. One after another, they declared their independence: Colombia in 1810, Venezuela in 1811, Argentina in 1816, Peru in 1821, Bolivia in 1825, and so on.

Something similar happened in the case of North America. In the southern parts of that continent the British had established large plantations where they grew tobacco, sugar and cotton for export. In the eighteenth century these products proved extraordinarily successful. Suddenly people everywhere around the world started smoking, eating sweets and dressing in cotton fabrics. To make up for the shortfall in cheap labor, the settlers in North America began importing African slaves. When slavery eventually was abolished in 1865, there were close to 4 million slaves in the United States. Today some 13 percent of the U.S. population — around 40 million people — identify themselves as “African-American.” In British North America, there were three quite distinct groups of settlers — the plantation owners in the South, the Puritan settlers in New England, and the people who lived in fledgling cities like New York and Boston. The lifestyle, outlook, and values of these three groups were really quite different, yet they, much as the settlers in South America, shared a resentment towards any outside interference. They insisted that London had no right to tax them as long as they were not represented in the British parliament. Moreover, they wanted to continue their expansion westward, a project which London regarded as too adventurous. Thirteen settler colonies in North America declared their independence from Britain in 1776.

As a result, by the 1820s European imperialism had largely come to seem a thing of the past. People in Britain looked back wistfully on the days when they had had an empire. There was still Canada to be sure, but this territory was mainly a concern for merchants involved in the fur trade; there was India too, but India was ruled by the East India Company and was not a British colony. Other European countries had even less of an empire. As a result of the Seven Years’ War, the French had lost most of their commercial outposts; the Portuguese had lost Brazil, even though they retained their trading posts in Africa and Asia; there were Dutch settlers in South Africa, but the Dutch presence in the rest of the world was motivated by commercial imperatives, not by imperialism.

An industrial world economy

And yet, one hundred years later, at the time of the First World War, next to all of Africa and much of Asia were in European hands. Colonialism had returned with a vengeance. In order to understand this turn of events, we must understand the changes that took place in Europe itself. This is more than anything the story of the industrial revolution.

At the end of the eighteenth century, new ways of manufacturing goods were invented in Europe. Things were now being made in factories and by machines, powered first by steam and later by electricity. Before long cheap, mass-produced goods were flooding European markets. Yet the factories produced much more than European consumers could buy and, for this reason, it became crucial to find new customers. New sources of raw material were needed too, resources which in many cases could only be found on other continents. These economic imperatives meant that the Europeans took a renewed interest in the world. The eventual result was a second wave of imperial expansion and the creation of an international system completely dominated by Europe.

This time it was the British who took the lead. It was in Britain after all that the industrial revolution started, and the trading stations and colonial outposts which remained in their hands provided them with a head start. The British also had a navy which was second to none. Moreover, throughout the nineteenth century, the British government was dominated by free-traders, by politicians, that is, who wanted to abolish customs duties and make sure that British merchants had free access to foreign markets. It was easy for the British to be in favor of free trade since they were the ones whose factories produced goods most cheaply. The strategy the British pursued was always the same. They approached the ruler of a non-European country and asked for access to its customers and its raw materials. If the country in question agreed, the British established themselves and started buying and selling. But if the country refused, the British would threaten military action. In some cases the natives eventually gave in and signed a commercial treaty, often referred to as an “unequal treaty.” In other cases, when the natives stood their ground, the result was war.

This is how Britain, step by step, came to establish its worldwide preeminence. The British, that is, had no grand master plan for how to take over the world. Rather, one step led to another, and they were all guided by what were at first regarded as economic imperatives — foreign markets had to be opened up; trading posts had to be defended; British investments abroad had to be made more secure. India illustrates this rather absent-minded logic. Here the British had at first only small trading posts, but in the course of the eighteenth century they were sucked into the struggles which characterized politics in the fragmenting Mughal Empire. Read more: The Mughal Empire at p. 64.

Soon the East India Company made alliances with powerful Indian princes. The carrot the British dangled before them was access to international markets; the stick which they wielded was the army the British had brought with them. At the battle of Palashi — known to the English as “Plassey” — in 1757, the East India Company defeated the ruler of Bengal and his French allies. As a result, the British suddenly found itself the main power broker on the subcontinent.

At the same time it would be a mistake to exaggerate Europe’s superiority — at least as far as the first half of the nineteenth century is concerned. Many locals defended themselves ferociously and often they had access to military technology which was no worse than that of the Europeans. Thus, even as their colonial empires spread, there were plenty of embarrassing reversals. The British lost wars not only in Burma and Afghanistan, but against the Asante and the people of Benin. And in 1857 they came very close to being thrown out of India.

The well of Cawnpore

In May 1857, a mutiny began among native soldiers in the army of the British East India Company. The rebels captured large parts of the northern plains of the subcontinent, including the province of Oudh and the city of Delhi, where they installed the Mughal king as their ruler. The war was characterized by great cruelty on both sides. In June 1857, the Indian rebels laid siege to the British settlement at Kanpur — “Cawnpore” to the British — but after three weeks, with little food left, the settlers accepted an offer of safe passage. As they made themselves ready to depart, however, the men were all butchered. While women and children were spared at first, they were later hacked to death and their bodies were thrown into a well — the notorious “well of Cawnpore” — which, as the story goes, “filled up to within six feet of the top.”

The acts of retribution meted out by the British army were every bit as savage as the acts committed by the rebels. On the suspicion of harboring pro-rebel sympathies, the British commanders ordered entire villages to be burned. A favorite method of execution was to tie the rebels before the mouths of cannons and to blow them to pieces. As Charles Dickens’s weekly, Household Words, assured its readers in a graphic account of this practice, this way of punishing mutineers “is one of the institutions of Hindustan.” While it may seem barbarian to us, it is in fact “one of the easiest methods of passing into eternity.”

As for the British public, it was largely supportive of such cruelties. Many felt betrayed by the mutineers who, according to an influential strand of opinion, had always been benevolently treated by the East India Company. In general — and as newspaper proprietors soon discovered — the British public loved reading about atrocities committed against their own countrymen. The gorier the details, the more titillating; a particular favorite were accounts of fair English maidens being raped by low-browed, brown men. Given such heinous crimes, the justice of the British retribution was never in doubt.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/a16b152d

The British Empire was enormous, but Britain itself was tiny. The empire was like an oak tree planted in a flower pot. Meanwhile the French began their colonial conquest of North Africa. Parts of Algeria were occupied in the 1830s and eventually incorporated into the French state. But here too the Europeans met with ferocious resistance and it took the French more than ten years to conquer Algeria. Since they were often unable to defeat their enemies outright, the French employed what they proudly described as “barbarian tactics.”

Le système Bugeaud

Algeria was invaded by France in 1830. However the country soon proved difficult to govern, and the French army was harassed by Arab guerrilla fighters. In 1837, they were forced to conclude a treaty which gave Algerians control of two-thirds of their territory. The French ignored the agreement, however, and the following year the war recommenced. Looking for a more effective way to fight the Arabs, general Thomas Robert Bugeaud, the Governor-General of the colony, developed a new method of warfare — known as le système Bugeaud — which he argued was more suitable for African conditions. A main feature of the système was the razzia — the destruction of all resources that supported the lives and livelihoods of the Arab community, their crops, orchards, and cattle. Only by declaring war on civilians, Bugeaud argued, and by terrorizing and starving them, could the enemy be subdued. Yet, he insisted, there was nothing immoral about such methods. After all, France’s aim was to civilize the Africans. “Gentlemen,” as he explained to the parliament in Paris, “war is not made philanthropically; he who wills the end wills the means.”

Other European powers met with similar resistance in their colonial wars. The British had to fight no fewer than five wars against the Asante, three wars in Afghanistan and Burma, and two opium wars in China. The French fought two wars in Dahomey and the Germans were fiercely resisted by the Herero of southwestern Africa. The problem in all cases was that the enemies were far away, the European forces actually quite small, and that it was difficult to administer the lands to which they laid claim. Even if one expedition was successful, the natives soon reasserted themselves, and the Europeans had to come back for a second expedition, and occasionally for several more. Colonial wars were not at all like wars in Europe, the Europeans concluded; they required tactics suitable to local conditions.

What settled these wars, in the end, was not military superiority as much as the ability to strike terror in the local population. Colonial warfare should have “pedagogical aims” — you should strike so hard and in such a devastating fashion that no one dared to resist. The système Bugeaud was an example of such state-sponsored terrorism, and it eventually proved effective. One by one the Algerian guerrilla fighters were killed or captured, and in 1843 their independent state collapsed.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/05a1d23c

In the nineteenth century this was more than anything the way the Europeans conducted colonial warfare.

Yet the big prize for European merchants was China. The country had some 350 million people — reputed to represent “a third of mankind” — and they were all, the Europeans were convinced, eager to buy their products. The only problem was that the Chinese authorities only allowed trade in the southern city of Guangzhou — known to the Europeans as “Canton” — and only for part of the year. To the British in particular this was not nearly good enough. Read more: George Macartney at Qianlong’s court at p. 29.

They wanted access to China for their cotton fabrics and their silverware but in addition they wanted to sell opium. Opium was the solution to the perennial problem of what to sell to the Chinese. Opium was grown in India by the British East India Company, and before long the exports to China were booming. The only problem was that opium was illegal in China. When the Chinese authorities tried to stop the trade, the British embarked on two wars — the First Opium War of 1839–1842, and the Second Opium War of 1856–1860. China lost on both occasions and was eventually forced to open all its ports to foreign trade, including the trade in opium. The traditional international system of East Asia, which had had China at its center, was no more.

The European destruction of Yuanmingyuan

The Chinese emperors of the Qing dynasty did not live in the imposing buildings that tourists can still see in the center of Beijing. Rather, they lived at Yuanmingyuan. Yuanmingyuan, just northwest of Beijing, was a large pleasure garden filled with palaces, villas, temples, pagodas, lakes, flowers, and trees. It was also the location of an imperial archive and library, and the place where the emperors stored tributary gifts given to them by foreign delegations. The Yuanmingyuan was the secluded playground of the Chinese rulers; it was “the garden of gardens” and a vision of paradise.

In October 1860, a combined army of British and French troops entered Yuanmingyuan and destroyed the whole compound. Between October 6 and 9, the French looted many of the contents of the palaces. The soldiers, including many officers, ran from room to room, “decked out in the most ridiculous-looking costumes they could find,” looking for loot. The ceramics were smashed, the artwork pulled down, the jewelry pilfered and rolls of the emperor’s best silk were used to tie up the army’s horses. “Officers and men seemed to have been seized with a temporary insanity”; “a furious thirst has taken hold of us”; it was an “orgiastic rampage of looting.” Then on October 18, James Bruce, the eighth Lord Elgin, the highest-ranking diplomat, and leader of the British mission to China, decided to burn the entire compound to the ground. Since most of the buildings were made of cedar-wood, they burned quickly, but since the compound was so huge it still took the British soldiers two days to complete the task.

The Europeans committed this act of barbarism in order to “civilize” the Chinese. China had isolated itself and failed to keep up with world events, but now the Europeans were going to help them. By waging war on the Chinese, they were going to force them to open up to the world market and to influences from abroad. The destruction of Yuanmingyuan was the act of barbarism which was to decide the matter. The destruction terrorized the emperor and the court and made them realize that they were powerless against the intruders.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/58535007

From being the “Middle Kingdom,” and the country responsible for keeping Heaven and Earth in harmony with each other, China became a peripheral player in an international system controlled by Europe.

The Japanese market was pried open in much the same fashion, although here threats were enough, and it was the Americans who took the lead. Since the early seventeenth century, Japan had had only limited interactions with the rest of the world; all official trade was restricted to only one city, Nagasaki, in the far south. Read more: A Japanese international system? at p. 36.

However, in the summer of 1853, the American Matthew Perry appeared in Edo harbor on board a steam-driven gunboat, demanding that Japan open up its markets. Initially at a loss for what to do, the Japanese began making concessions. Eventually, their policy of seclusion unraveled. An important force behind the change in policy was the daimyo, the local rulers, especially the ones in the south of the country who had already been engaging in clandestine trade with the outside world for a long time. Read more: The Ryukyu Islands as the center of the world at p. 38.

In 1868, the changes set in motion led to the overthrow of the Tokugawa government. Soon Japan also found itself a small player in an international system dominated by Europe.

The apotheosis of colonialism

As a result of the industrial revolution, and the relentless pace of economic development it unleashed, the Europeans gained a new sense of self-confidence. This radically changed their view of the rest of the world, and of Asia in particular. From the first faltering contacts in the Middle Ages to the end of the eighteenth century, the Europeans had admired and looked up to Asia. However, in the first part of the nineteenth century, almost overnight, Asia became an object of scorn. The problem, more than anything, was that Asia had failed to develop in the European fashion. Asia had missed out on the industrial revolution. A country like China, the Europeans now decided, was “stagnant” and “stuck in the past”; it made no progress and as a result it could not be said to have a proper history. In order to give the semblance of scientific validity to such claims, many Europeans made references to biology. Misreading Charles Darwin’s The Origin of the Species, published in 1859, they decided that the different “races” of the world were locked in an inescapable struggle. The Europeans had proven themselves superior and thus deserved to rule over all others. The “inferior races” were to be their servants, and the least developed people of all would come to be destroyed. Such was the logic of human history. To help history along, the Europeans carried out genocides against the people of Tasmania, Tierra del Fuego, the Herero people of Namibia, and many others. Read more: The Ryukyu Islands as the center of the world at p. 191.

The nineteenth century had been quite peaceful, as far as European history goes. There were some wars to be sure, but nothing like the wholesale destruction that was to take place in the twentieth century. In the last couple of decades of the nineteenth century, however, the mood began to change. A more aggressive form of nationalism emerged, and one country after another began looking for ways to assert themselves. Italy was united in 1861 and Germany in 1871. Both countries — Germany in particular — were on the rise and they wanted a bigger role, and a bigger say, in world affairs. One way for a country to assert itself was to acquire colonies. Colonial possessions became a symbol of great-power status and the new European nation-states often proved themselves to be very aggressive colonizers.

It was then that Africa for the first time came into focus as a continent to explore and exploit. The Europeans had been trading with Africa since the fifteenth century, but much as in Asia, their presence had been limited to small trading ports along the coast. The only exception was the southernmost part of the continent where Dutch farmers had settled. Meanwhile the Europeans knew nothing whatsoever about the inner parts of the continent. This gradually changed in the course of the nineteenth century as European adventurers and missionaries went on voyages through the jungles, often supported by “national geographical societies” in their respective home countries. In their footsteps came agents of large trading companies, European soldiers, settlers and colonizers. The Europeans found gold and ivory, but also diamonds and copper, palm oil, cocoa, bananas and other “colonial produce.” There was plenty of money to be made in getting these products back to markets in Europe. As a result, little by little, Africa was divided up. Although the African kingdoms often defended themselves successfully, the Europeans always returned with larger and more powerful armies. It was in order to regulate this “scramble for Africa” that all countries with colonial aspirations met at a conference in Berlin in 1884.

The Berlin Conference

After 1871, European imperialism in Africa entered a new phase. Until this time only small groups of investors, explorers and missionaries had taken an interest in this part of the world. Except for the Dutch settlement in South Africa and the French in Algeria, their presence had been restricted to a few trading ports along the coast. The rest of Africa was too remote, too malaria-ridden, and simply not a sufficiently profitable proposition. After 1871, however, Europeans suddenly went on to explore and colonize the interior too. Before long the whole continent, except for Ethiopia, was divided between them. Read more: Countries that were never colonized at p. 196.

The reason for this burst of colonial ambition had little to do with Africa and everything to do with Europe itself. France turned to Africa as a way to compensate for the humiliating loss in the war against Germany in 1871. For the French, it was a way to prove to themselves that they still were a world power. Britain became interested in Africa mainly as a way to check French ambitions. Germany, which was united only in 1871, aimed to catch up with the other European powers. Africa was a good place to do it, since much of the land there seemed to be empty. Meanwhile, the Ottoman Empire, which up to this point had ruled much of North Africa, was too weak to defend its former possessions. Technological advances assisted the Europeans. Steamships took them up Africa’s rivers, quinine helped them fight malaria, and far more lethal weapons helped them fight the natives.

In order to find an orderly way to resolve these conflicts, fourteen European countries gathered for a conference in Berlin in November 1884. On the wall of the conference hall was a large map of Africa on which the Europeans staked out their claims. Only two of the delegates had themselves set foot in Africa, and no Africans were present. The great winner was King Leopold II of Belgium who managed to acquire all of Congo as his personal possession. He presented himself to the global community as a great humanist and friend of the African people. In the subsequent conquest of the continent, millions of Africans died.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/e73db31d

The meeting, by all accounts, was a very civilized affair. The participants gathered around a large map of Africa and divided the various territories between themselves. Elsewhere in the world the French added Indochina to its growing empire and Britain occupied Burma and Malaya. Meanwhile the Russians moved into Central Asia and the United States pushed westward across the great North American plains towards the Pacific Ocean. This is how it happened that, by the time of the First World War, most parts of the world were under European control, or were controlled by European settler societies. There were some scattered exceptions to this rule, but in these ostensibly independent countries the Europeans still had a strong presence.

Countries that were never colonized

Not all non-European countries were colonized by the Europeans, not even at the height of Europe’s power. Which countries were these and why did they manage to preserve their independence? First of all, we have the ancient empires of Asia — Persia, China, and Japan. They were far too big and far too far away to be colonized. This does not mean, however, that the Europeans did not meddle in their affairs. China was something of a “semi-colony,” and Japan was forced to accept humiliating terms in the treaties they concluded with European powers. In addition, we have countries such as Nepal, Bhutan, and Afghanistan which are best described as “buffer states.” That is, they were left as cushions between European empires — or, to be precise, between Britain and Russia. The Afghans defended themselves ferociously in no fewer than three Anglo-Afghan wars and, in the end, Britain decided it was better to leave them alone. A third group includes Ethiopia and Thailand. Both were established monarchies and the kings in question were very skillful in appealing to the international community for support. In addition, they were good at organizing their own bureaucracies. Essentially, they colonized their own countries using administrative methods which were very close to those employed by the Europeans themselves.

Then there is Liberia in West Africa which was established by the American Colonization Society, an American charity, as a place to which former slaves could be repatriated. It was not a colony, but not really an independent country either. In addition, there were states which now are independent — such as Korea, Taiwan, and Mongolia — which were colonized, but not by the Europeans. The final case is the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans were not colonized by the Europeans; indeed they were themselves a part of the European system of states. They were also a large and ancient empire, although in the nineteenth century this was shrinking precipitously.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/1f204a45

When we think of the colonial era today, it is generally this second burst of colonial expansion that we have in mind. In the last decades of the nineteenth century the Europeans really did come to rule almost all of the rest of the world. Their methods were often ruthless and exploitative. There were many wars and the occasional genocide. The atrocities were backed up by ideas of European superiority based in the alleged science of race biology. At the same time we should remember that the apogee of colonialism only lasted for about fifty years. In terms of world history, this is nothing but a short parenthesis. Already in 1914, by the time of the First World War, the Europeans found themselves busy with other matters, and in 1945, by the end of the Second World War, colonial empires were an anachronism. Europe was devastated by the two world wars and colonies had become an expensive luxury. Things were once again about to change.

Decolonization

Independence and statehood are most conveniently measured in terms of membership of the United Nations. The United Nations today has well over 190 member states. This number can be contrasted with the fifty-seven independent states that joined the organization before the year 1950. Something has happened, in other words, since the time of the founding of the UN — the number of independent states in the world has increased four-fold! This is the story of decolonization, of how the former colonies made themselves independent from their European rulers.

By 1945, as we have said, colonialism had become an anachronism. Colonies were a net drain on the resources of European countries and colonialism had little public support. Although there certainly were individual business interests which gained considerably from the existing arrangements, the European countries as a whole did not. This was particularly the case where there was determined local resistance to colonial rule. As Europeans came to realize to their chagrin, when faced with a local enemy bent on fighting for its independence, the Europeans would always, sooner or later, lose. The locals were fighting on their own turf after all, and the Europeans were far from home. The Europeans had the clocks, as the saying went, but the locals had the time. Maintaining an empire under such circumstances would have required a commitment that simply did not exist.

The process of decolonization began in an unlikely place: the island of Saint-Domingue in the West Indies, a French colony and the country we today call Haiti.

Revolution in Saint-Domingue

On August 22, 1791, the slaves on the French island of Saint-Domingue in the Caribbean began a rebellion which ended with independence for the new country of Haiti in 1804. This was the first successful slave uprising in the Americas, and Haiti was the second country, after the United States, to become independent of Europe. The French had first arrived in the 1660s, and in 1697 they established a colony there. Saint-Domingue had been a quiet, provincial outpost until the first sugarcane plantations were established. When in the eighteenth century Europeans began their intense love affair with sugar, Caribbean plantations became the main source of the produce. The laborers required for the task were imported as slaves from Africa. Read more: Dancing kings and female warriors of Dahomey at p. 139. Soon the plantation owners in Saint-Domingue were making enormous profits, and the 40,000 Europeans on the island were the owners of some 500,000 African slaves.

The French Revolution of 1789 provided the slaves with a language in which to formulate their grievances. They too wanted liberté, égalité, and fraternité. In addition, the voodoo religion united the community around a shared, African, identity. The leader of the uprising, Toussaint Louverture, was a freed slave who soon proved himself to be a very talented general who, before long, had the slave masters on the run. However, once Napoleon Bonaparte had come to power in Paris, he sent a punitive expedition to the Caribbean. They captured Toussaint Louverture and dispatched him to France. Nonetheless, the revolution itself was unstoppable. New, equally talented leaders emerged, and in 1803 the French army was conclusively defeated. Independence was declared the following year. The country was renamed “Haiti,” meaning “mountainous place” in the language spoken by the Taino, the people who had lived there before the Europeans arrived.

The subsequent history of Haiti is a sad one. By the nineteenth century, the sugar boom was over, and the country’s new elite proved itself to be both authoritarian and corrupt. The United States invaded the island in 1915 and occupied it until 1934. Since 1945, the country has had a number of dictators and successive military coups have taken place. Today Haiti is the poorest country in the western hemisphere.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/744a8bb0

In 1791, inspired by news of the French Revolution, and fed up with being exploited for their labor, a vast rebellion broke out among the slaves on the plantations, and in 1804, the country declared itself independent. A similar independence struggle began in India in 1857. Read more: The well of Cawnpore at p. 190.

British rule in India was always fragile and depended heavily on the collaboration of local elites and on the loyalty of the indigenous army. When Muslims and Hindu soldiers joined forces, rallying behind the institution of the Mughal emperor, the British found themselves in a seemingly hopeless situation. Eventually the British reasserted their power, but it was a close call.

Starting in the late 1950s, and accelerating in the 1960s, one former colony after another made itself independent, and by 1970 there were few colonies left. Those that remain today are geographical curiosities like the Malvinas Islands in the South Atlantic, which are a British possession, and Nouvelle-Calédonie (New Caledonia) in the Pacific, which remains French. This is not to say that the struggle for independence was an easy process or that the Europeans gave up without a fight. Well into the 1950s, the French believed they could defend their possessions in Indochina. However, at the battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954, they were decisively defeated. From this time onward, the United States gradually came to take over responsibility for what in the 1960s was known as “the Vietnam War.” Yet the U.S. too was also eventually defeated by the Vietnamese and its armies were expelled from Indochina in 1975.

Another bloody conflict fought by the French took place in Algeria. Here a sizable group of European settlers, numbering well over one million people, had considered Algeria their home for generations. An armed uprising began in 1954 which ended with independence for the country in 1962. The British, meanwhile, were fighting guerrillas in both Kenya and Malaya. Here too the conflicts were bloody, but the independence movements eventually won.

This is how the European way of organizing international politics became the universal norm and the European type of state the only viable political unit. This outcome was a consequence of colonialism, yet colonialism itself was actually not the cause. After all, a colonized country is the very opposite of a sovereign state; colonized peoples have no nation-states and enjoy no self-determination. It was instead through the process of liberating themselves from the colonizers that the European models were copied. The Europeans would only grant sovereignty to states that reminded them of their own. The only way to become an independent state, that is, was to become an independent state of the European kind. The creation of such a state was consequently the project in which all non-European political leaders were engaged. All independence movements wanted their respective territories and fortified borders, their own capitals, armies, foreign ministries, flags, national anthems and all the other paraphernalia of sovereign statehood. They all wanted to become a version of what the Europeans were.

Yet, in far too many cases the newly independent states ran into difficulties. The political institutions were too weak, the economy was not developing, or not developing fast enough. Often there were highly valued commodities — gold, diamond, oil — over which men with weapons were prepared to fight. The new national leaders — in many cases educated in the schools of the colonial powers and trusted by the Europeans as “one of theirs” — often had no nations that they could lead. Instead, nations had to be “built” — constructed, assembled, imagined — but this, in many instances, turned out to be an impossible task. The outcome was a long series of “failed states,” states, that is, which have failed to live up to the European standard. Whether it made sense for the newly independent states to live up to European standards in the first place was rarely discussed. Whether there were alternative, non-European ways of organizing a state and its foreign relations was never discussed either. The pre-colonial history of the non-European world was never allowed to play a role in the world of independent states which now came to be established.

G. K. Chesterton on Indian nationalism

G. K. Chesterton, 1874–1936, was a British journalist and author, still known today for the Father Brown series of detective stories. Chesterton was also a philosopher of sorts and a devout Catholic. On September 18, 1909, he wrote an article in the Illustrated London News in which he discussed Indian nationalism. He did not like it, but not for the reasons one might expect. Indian nationalists, he declared, are “not very Indian and not very national.” What they want for their country are all the trappings of our government — they want our parliament, our judiciary, our newspapers, our science. The fact that Indian nationalists want all these things is evidence that they really want to be English. As a result, “[w]e cannot feel certain that the Indian Nationalist is national.”

Mahatma Gandhi, the leader of the Indian independence movement, who was visiting London at the time, read Chesterton’s article when it first appeared and, according to his biographer, “he was thunderstruck.” On the boat back to South Africa two months later he wrote the first draft of a book, Hind Swaraj, where he addressed the problem of “home rule.” Clearly, Chesterton’s thoughts were still with him. In order to obtain home rule, Gandhi insisted, we must first make sure that we have a home that is truly our own. If we only copy English institutions, our country will not be “Hindustan,” but instead “Englistan.” For a country to be independent, it must be defined in independent terms. India must be herself, not a version of Britain. Starting from this premise, the rest of the book elaborates on what home rule really means.

Chesterton and Gandhi were romantics, and they were quick to denounce the evils of modern society. “It is machinery that has impoverished India,” Gandhi argued, and in particular the factories of Manchester that had wiped out India’s indigenous cotton industry. Gandhi’s famous response was to learn how to spin his own yarn using a hand-loom, and to make his own clothes. This, he argued, was the way to make India self-sufficient. Only a self-sufficient India would be able to rule itself.

Read more online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/e13224c8

This is how we all came to live in a European world.

|

|

|

|

Chakrabarty, Dipesh. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000. |

|

|

Harlow, Barbara, and Mia Carter, eds. The Scramble for Africa. Durham: Duke University Press, 2003. |

|

|

Hillenbrand, Carole. The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1999. |

|

|

Lemarchand, René, ed. Forgotten Genocides: Oblivion, Denial, and Memory. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011. |

|

|

Nandy, Ashis. The Intimate Enemy: Loss and Recovery of Self Under Colonialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994. |

|

|

Osterhammel, Jürgen. The Transformation of the World: A Global History of the Nineteenth Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014. |

|

|

Ringmar, Erik. Liberal Barbarism: The European Destruction of the Palace of the Emperor of China. New York: Palgrave, 2013. |

|

|

Ringrose, David R. Expansion and Global Interaction, 1200–1700. New York: Longman, 2001. |

|

|

Todorov, Tzvetan. The Conquest of America: The Question of the Other. New York: Harper & Row, 1994. |

|

|

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston: Beacon Press, 1995. |

Timeline

|

1095 |

First Crusade called for by Pope Urban II. |

|

1295 |

Marco Polo returns to Venice after 24 years in China. |

|

1492 |

Cristoforo Colombo arrives in the Caribbean and establishes a colony in Hispaniola, today’s Haiti. |

|

1498 |

Francisco da Gama arrives in Calicut. This was the first successful journey by sea between Europe and India. |

|

1602 |

The Dutch East India Company, Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, known as VOC, is established in Amsterdam. |

|

1620 |

The Mayflower carrying English settlers arrives at Plymouth Rock. |

|

1763 |

The Seven Years War is concluded. France loses most positions in India and North America. |

|

1776 |

European settlers in North America declare independence. |

|

1804 |

Haiti declares independence from France. |

|

1830 |

France invades and colonizes Algeria. |

|

1857 |

The Indian Uprising comes close to expelling the British from India. |

|

1885 |

The Berlin Conference is concluded. Africa divided between European powers. |

|

1947 |

India and Pakistan declare independence from Britain. |

|

1954 |

The Battle of Dien Bien Phu. French forces are defeated by a Vietnamese army. |

|

1975 |

The United States withdraws from Vietnam. |

Short dictionary

Think about

A sea route to India

- Who were the Vikings?

- What were the Crusaders trying to achieve?

- Why did the Europeans started looking for a sea route to Asia?

Europeans in the “New World”

- What explains the genocide of indigenous people in the Americas?

- What is the “Columbian exchange”?

- Who were the Puritans?

A commercial world economy

- What political roles did the East India companies play?

- Give an account of the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

- Why and how did the settler societies of the Americas achieve independence?

An industrial world economy

- How did the industrial revolution change Europe’s relations to the rest of the world?

- What were the characteristic battlefield tactics of Europe’s colonial wars?

- How was the Chinese market eventually opened up to foreign trade?

The apotheosis of colonialism

- How were the kingdoms of Asia turned into objects of ridicule?

- What happened at the Berlin Conference in 1884-85?

- Why did European states start searching for colonies in the latter part of the nineteenth century?

Decolonization

- Why did most colonies achieve independence in the decades after the Second World War?

- Give an account of Algeria’s independence struggle. And Vietnam’s.

- What were some of the challenges faced by the newly independent states?