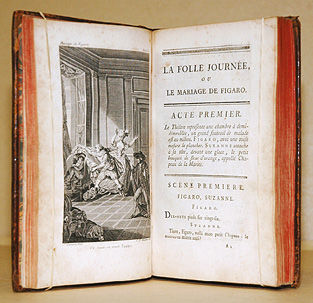

12. Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais (1732-1799), The Marriage of Figaro, 178420

In 1784, Beaumarchais was finally able to stage his censored play The Marriage of Figaro.21 In this famous soliloquy, Figaro bitterly assesses his life and opportunities, looking back over the different jobs he’s had, particularly as a writer, when he was ceaselessly subjected to censorship, whatever he wrote, and threatened with imprisonment for debt by the bailiff’s assistant. This extract picks up just after Figaro’s explanation of why he gave up being a vet.

Tired of making sick animals miserable, and looking for a complete change of job, I throw myself body and soul into the theatre: if only I’d tied a stone round my neck instead! I put together a comedy set in a harem. As I’m Spanish, I think I can be rude about Mohammed without any trouble, but some emissary from I don’t know where immediately complains that my lines are offensive to the Ottoman Empire’s Sublime Porte, to Persia, to a sub-section of the Indian sub-continent, to all of Egypt and to the kingdoms of Cyrenaica, Tripoli, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco, and the result is that my play is done for, just to please some Muslim princes, not one of whom can read so far as I know, and who like to give us a good whipping as they call us names and tell us we’re Christian dogs. – When people can’t debase wit or cleverness, they take their revenge by abusing it. – My cheeks hollowed out, I had run my course: I could see the horrendous bailiff’s assistant looming over the horizon, a quill stuck ominously in his wig: shaking and shuddering with fear, I make one last effort. Everyone’s debating the nature of wealth, and given that it isn’t necessary to have any wealth to be qualified to discuss it, and without a penny to my name, I publish a piece on the value of money and its net product, whereupon I’m immediately hauled off to prison. From the back of a carriage, I watch the drawbridge of a fortress lowering just for me, and there I abandon hope and freedom. (He stands up.) How I would love to get hold of one of those flash-in-the pan powerful men who so lightly give the order for disaster to strike, once they’ve fallen from grace good and proper, and their pride all been scooped away! I would tell him… that printed nonsense only ever means anything in those places where it’s blocked; that, without the freedom to criticise, there can be no truly flattering praise; and that only small men mind about little pieces of writing. (He sits back down.) They finally tire of giving someone as obscure as me bed and board, and turn me out onto the street. As I still need to eat, even though I’ve been freed from prison, I sharpen my pen once more, and ask around to find out what the current hot topic is : I am told that during my economic retreat a system has been set up in Madrid to permit the free sale of commodities which extends even to the press, and that, so long as I don’t write about the authorities, about worship, politics, morality, about anyone in power, protected institutions, the Opera or other performing arts, or about anyone who particularly stands by anything, I can publish whatever I like, subject only to inspection by two or three censors. To take advantage of this delightful freedom, I advertise that I will be setting up a periodical, and, assuming I won’t be treading on anyone’s toes, I call it the Useless Journal. We-hey! Straightaway a thousand poor devils set on my paper, I am suppressed, and here I am, jobless again!

Title page of Act I, The Marriage of Figaro, 1785 edition: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Figaro-acte1-éd_originale_1785.jpg

20 Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais, Le Mariage de Figaro, Act V, scene iii, in Théâtre, ed. by Jean-Pierre de Beaumachais, Paris: Garnier, 1980, pp. 305-306.

21 Portrait of Beaumarchais after Jean-Marc Nattier (c.1755): https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jean-Marc_Nattier,_Portrait_de_Pierre-Augustin_Caron_de_Beaumarchais_(1755).jpg