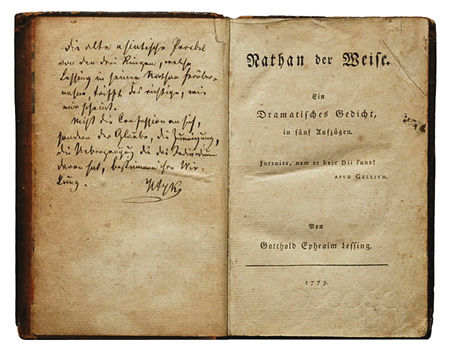

47. Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729-1781), Nathan the Wise, 177978

The German writer Gotthold Ephraim Lessing was the son of a clergyman, and in Nathan the Wise, he defends religious toleration. In this extract, Nathan, who is Jewish, has been telling the Muslim Saladin the parable of the three rings. This is the story of a father who possesses a priceless opal ring and does not know how best to share it amongst his three sons. He decides to have two copies made. On his death, each son receives a ring and each, believing that he alone owns the original one, is ready to fight to prove his claim. Nathan says that when it comes to religion we would do well to remember the story of the rings. Saladin doesn’t understand the point of the analogy, claiming that it is not difficult to tell Judaism, Christianity, and Islam apart. The French version of this was a translation by the poet Marie-Joseph Chénier, in which the misty opal becomes a sparkling diamond. We have not translated the translation: the acclaimed translator of Schiller, Francis Lamport, has gone back to the original and produced the following version for us, and we thank him.

Frontispiece of Nathan the Wise, 1779 edition: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lessing_Nathan_der_Weise_1779.jpg

[Jerusalem in 1192, during a brief truce between Sultan Saladin and the Crusaders. Saladin summons Nathan, the Jew renowned for his wisdom, and calls on him to declare which of the three great religions is the true one. Nathan replies with a parable:]

Long years ago, there lived a man in the East

Who owned a precious ring, inherited

From one he loved. It bore a stone, an opal,

That shimmered in a multitude of colours,

And had the wondrous power to win the love

Of God and man, for him who wore it in

Good faith. [...]

[The ring is handed down the generations, from father to favourite son, until it comes to a man who has three sons, all equally beloved. Unwilling to discriminate between them, he has two replicas made, so that each son severally receives one – which he of course believes to be the one and only true one. They quarrel, and the matter comes to court. The judge pronounces: ]

[...] Unless you can produce your father

To testify before me, I dismiss

The case. What, do you think my occupation

Is solving riddles? Or do you think the one

True ring will speak out for itself? – But wait:

I hear the true ring has the wondrous power

To make its wearer loved by God and man;

That must decide! For surely the false rings

Will not do that. Now, which of you three brothers

Is most loved by the other two? Speak out!

Well, tell me! Have you not a word to say?

The rings have no effect, each one of you

Loves no one but himself? Then you are frauds,

Yourselves defrauded. And it seems your rings

Are counterfeit all three. The true one has

Gone missing, and your father had three made

To cover up the loss [...]

But if your father gave

Each one of you his ring, then let each one

Believe his is the true one. – It may be

Your father wished to put an end to one

Ring’s tyranny within his house. And surely

He loved you all, and all in equal measure,

And did not wish to disadvantage two

By favouring one. – Well, then! Let each of you

Strive just to copy his unprejudiced

And free affection! Let him seek to prove

The power of the opal in his ring,

And seek to aid that power with gentleness,

Benevolence and fellow-feeling, and

Humility before the will of God.

And when these powers are made manifest

Amongst your children’s children’s children, in

A thousand thousand years, let them be called

Before this seat once more. A wiser man

Will then be sitting here, and will pronounce

His verdict. Go! – So spoke the modest judge.

saladin. God! God!

nathan. If, Sultan Saladin, you feel

That you might be that wiser man –

saladin. I? I

Am dust, am nothing! God!

nathan. What is it, Sultan?

saladin. Nathan! Your judge’s thousand thousand years

Are not yet past. His judgement seat is not

For me. Leave me, dear Nathan, go – But be my friend.

78 Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Nathan der Weise, 1779, Act III, scene vii.