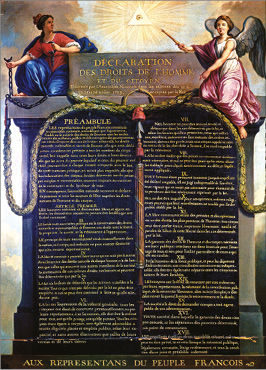

1. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen, 17891

On 4 August 1789, those given the task of drawing up the Constitution decided that it should be preceded by a Declaration of Rights.2 The deputies debated this Declaration fiercely and voted on it article by article throughout the week of 20-26 August 1789. The text remains an active part of the French Constitution.

The representatives of the French people, constituted as a National Assembly, consider that ignorance, neglect or scorn for the rights of man are the sole causes of public misfortune and of the corruption of governments, and have resolved to set out, in a solemn Declaration, the natural, sacred and inalienable rights of man, so that this Declaration, constantly present to all members of the social body, may continually remind them of their rights and duties; so that the acts of the legislative power, and those of the executive power, may be compared at any moment with the objects and purposes of all public institutions and may thereby be the more respected; so that the petitions of citizens, henceforth founded upon simple and incontestable principles, may ever tend to the maintenance of the Constitution and to the happiness of all.

In consequence, the National Assembly recognizes and declares, in the presence and under the auspices of the Supreme Being, the following rights of man and of the citizen:

Article 1. Men are born and remain free and equal in their rights. Social distinctions may only be founded upon the common good.

Article 2. The aim of any political association is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are freedom, property, security, and resistance to oppression.

Article 3. The principle of all sovereignty resides essentially in the nation. No body and no individual may exercise any authority which does not proceed directly from it.

Article 4. Freedom consists in being able to do anything which does not harm anyone else; thus, the exercise of the natural rights of each man has no limits except those which ensure that all other members of society enjoy the same rights. These boundaries may be determined only by the law.

Article 5. The law has the right to prohibit only those actions which are harmful to society. Anything which is not forbidden by the law cannot be prevented, and no man may be constrained to do anything which is not ordered by the law.

Article 6. The law is the expression of the general will. All citizens have the right to contribute personally, or through their representatives, to its creation. The law must be the same for all, whether in punishment or protection. All citizens being equal in its eyes, all are equally eligible for all distinctions, positions and public employments, according to their capacities, and without any discrimination other than that of their virtues and their talents.

Article 7. No man may be accused, arrested or detained other than in the cases determined by the law, and in accordance with the forms it has prescribed. Those who seek, send, execute or cause to be executed arbitrary orders must be punished; but any citizen who is called or summoned by virtue of the law must obey without delay: resistance will incriminate him.

Article 8. The law shall set only punishments which are plainly and absolutely necessary, and no man may be punished except by virtue of a law which has been established and promulgated prior to the offence, and legally applied.

Article 9. Every man being presumed innocent until he has been declared guilty, any rigour which is not deemed necessary for the securing of his person must be severely punished by the law.

Article 10. No man may be harassed for his opinions, even religious opinions, provided their expression does not disturb the public order established by the law.

Article 11. The free communication of thoughts and opinions is one of the most precious rights of man: every citizen may therefore speak, write and publish freely, but shall be responsible for such abuses of this freedom as shall be defined by law.

Article 12. The safeguard of the rights of man and of the citizen requires public military forces: these forces are thus established for the good of all, and not for the personal advantage of those to whom they shall be entrusted.

Article 13. For the maintenance of the public force, and for administrative expenses, a common contribution is indispensable: it must be equally levied from all citizens in proportion to their means.

Article 14. All citizens have the right to determine, either personally or through their representatives, the necessary level of the public contribution, to consent to it freely, to survey its employments, and to decide its rates, basis, collection and duration.

Article 15. Society has the right to demand that every public agent account for his administration.

Article 16. Any society in which the respect of rights is not guaranteed, nor the separation of powers secured, has no constitution at all.

Article 17. Property being an inviolable and sacred right, no one may be deprived of it, except when public necessity, as attested in law, manifestly requires it, and on condition of just compensation, payable in advance.

Read the free original text online:http://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/Droit-francais/Constitution/Declaration-des-Droits-de-l-Homme-et-du-Citoyen-de-1789

1 Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen, 1789.

2 Representation of The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen by Jean-Jacques-François Le Barbier (c.1789): https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Declaration_of_the_Rights_of_Man_and_of_the_Citizen_in_1789.jpg