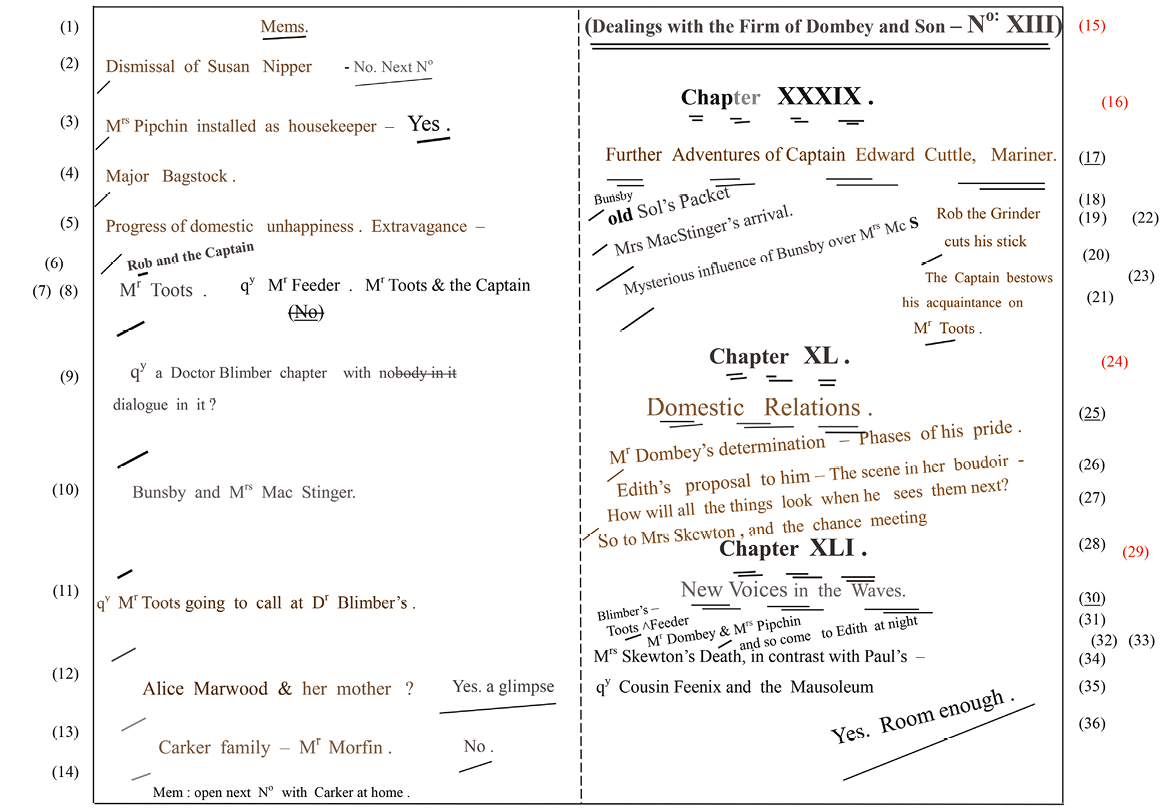

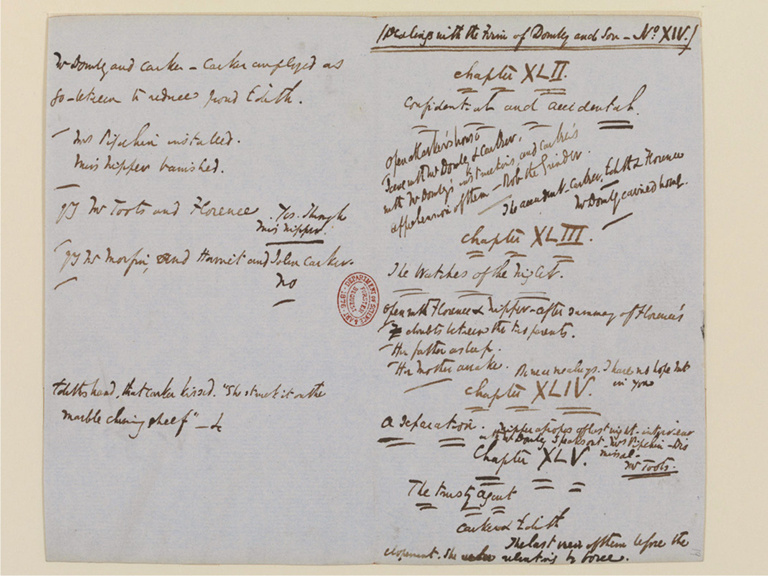

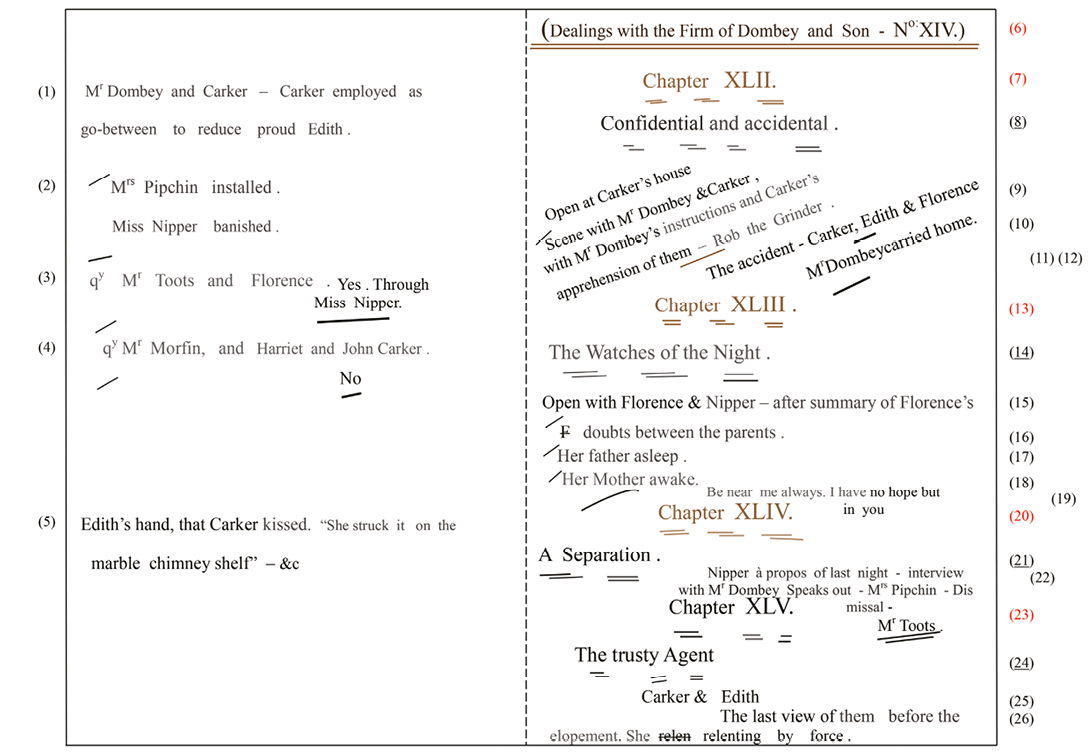

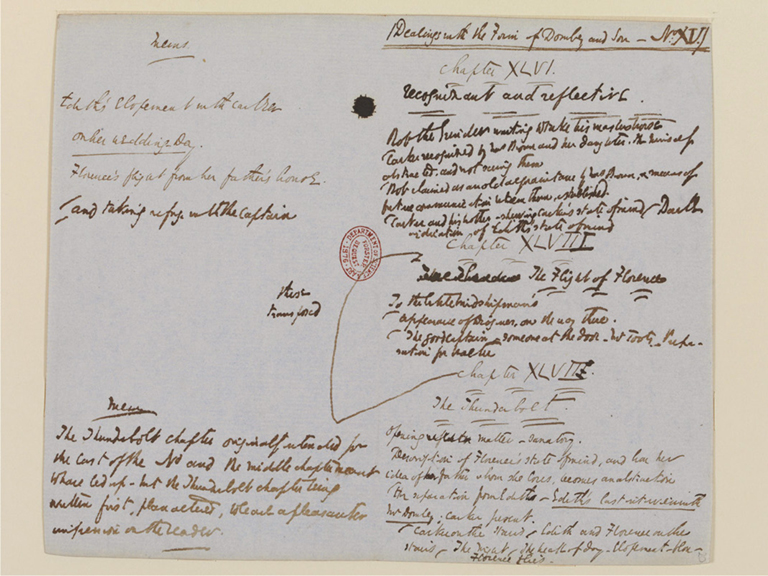

Section 5. The worksheets

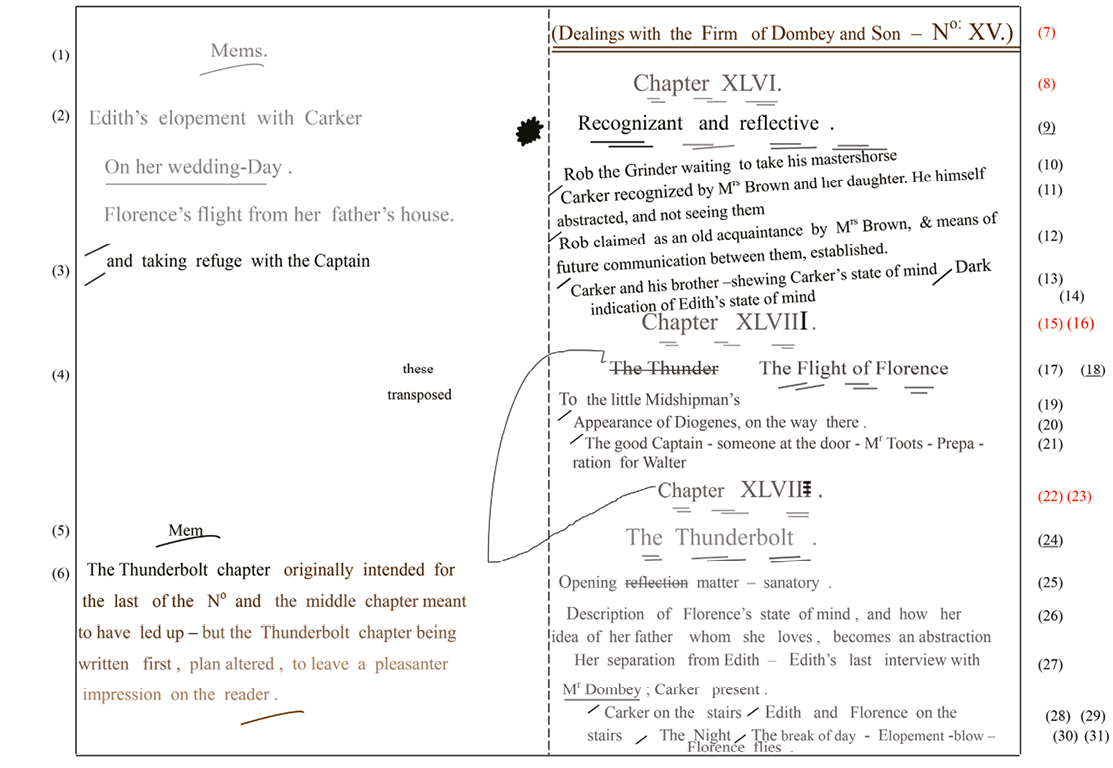

© 2017 Tony Laing, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0092.07

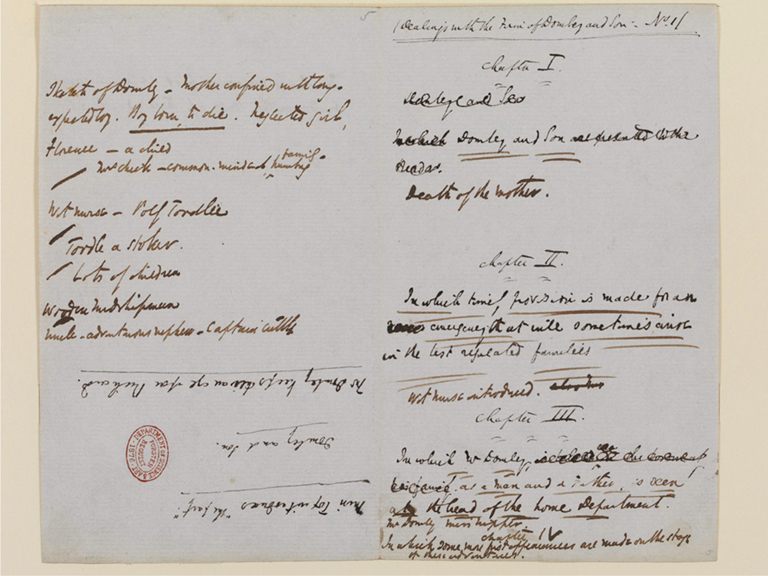

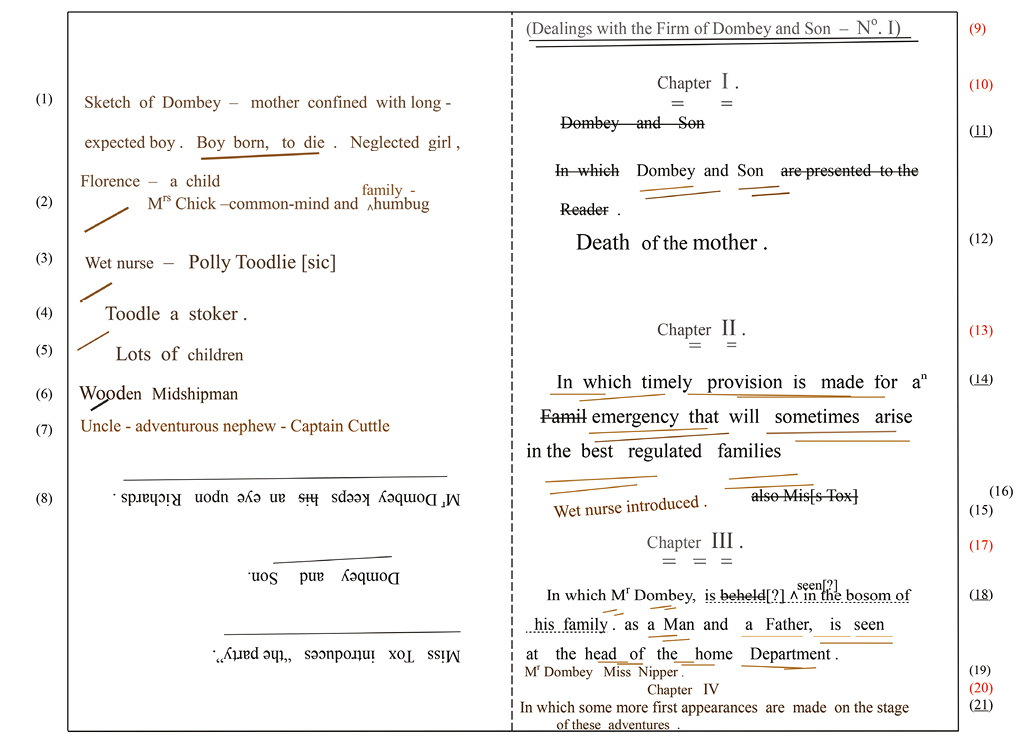

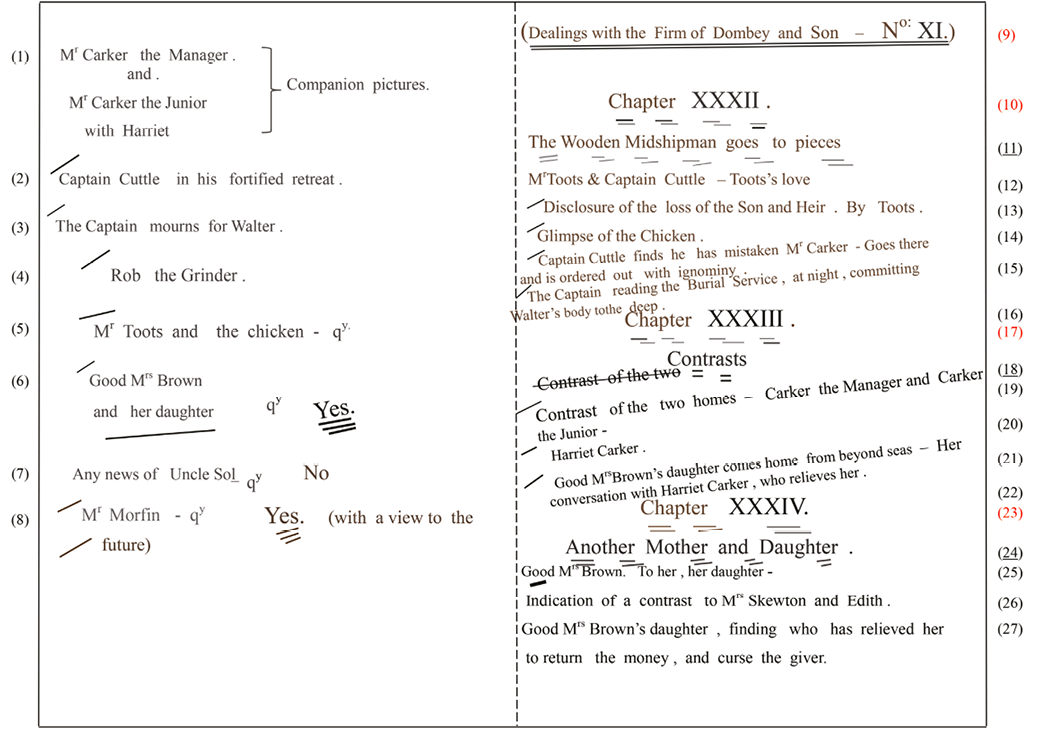

Worksheet for No.1 (verso)

Image No.2012FE1485 verso: Forster Collection, National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum (2015). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Click here to view a 'zoomifiable' version.

Transcription of Ws.1 (verso)

Worksheet for No.1 (recto)

Image No.2012FE1485 recto: Forster Collection, National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum (2015). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Click here to view a 'zoomifiable' version.

Transcription of Ws.1 (recto)

Commentary and order of entry Ws.1 (recto and verso)

Dickens and family settle in Lausanne in June 1846. The day after the arrival of his box of writing materials on 27 June, he “BEGAN DOMBEY! I performed this feat yesterday—only wrote the first slip—but there it is, and it is a plunge straight over head and ears into the story” (Life 400K:8159). Just four weeks later, he sent the first four chapters to Forster, and with it a lengthy detailed summary of the novel’s themes and structure, what he calls “the outline of my immediate intentions”.42 Nine weeks later, on 30 September, No.1 for October 1846 is published.

LH

Initial plan for the number: (1) & (2)→ch.1; (3), (4) & (5)→ch.2

These are identifiable by similarity of hand, ink and alignment. They are divided by idiosyncratic slashes, with one entry “Mrs Chick…humbug” (2) probably inserted soon after the others. The density and corrosion of entries is reasonably consistent in (1) and (2), though less so in (3)–(5). The corrosion of the two groupings is shown in two shades of brown. “Toodlie” is either an early version of Polly’s surname or a temporary trial alternative; either way it is rejected, perhaps for its inappropriate associations. In the last three initial entries, where Dickens is assembling materials for ch.2, entries (3)–(5) slip to the right as his hand and arm move downward. The first entry of a number plan often has wider scope than later ones. After noting the opening situation and the characters involved, Dickens indicates the direction of the narrative by “Boy born to die”. He frequently uses a single continuous underline to show that an entry looks forward beyond the number, in this instance to No.4, during which he initially plans to “kill Paul”.

Additional number plan: (6) & (7)→ch.4

Dickens uses a slightly heavier hand—and/or a more laden quill—for the sign of the Midshipman. Consequently, the lettering of (6) has retained more of its blackness, whereas the lighter hand and/or the less laden quill used for (7) has begun corroding throughout. Both are distinct from (1)–(5) in alignment, hand and to a less extent size. The two groups are divided by a slash, perhaps to further emphasise the importance of the shop and its sign. The second group comprises the three characters in the order in which they appear in the text. Together they suggest that Dickens is imagining structure as well as content for ch.4.

MS and RH

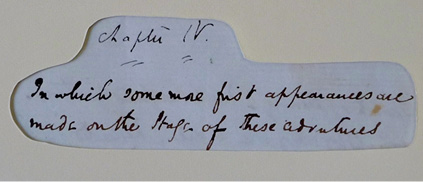

Preliminary headings: (9), (10), (13), (17) & verso (22)43

In the worksheet, Dickens gives the part heading—the longer novel title with the part number—and the number headings for four chapters, three spread evenly down the page and the number heading for ch.4 (22) entered by turning the worksheet over and writing on the under (verso) side. (The facsimile and transcription of the number heading for ch.4 is shown in portrait mode, before the facsimile of No.1 (recto). For an explanation, see endnote 41).

Composition and titling of chs.1, 2, 3 & 4: (11), (14) (18) & (23)44

In ch.1, Dickens probably titles in both worksheet and manuscript, but revises in worksheet and copies the revision to manuscript. In ch.2 on the other hand, he begins by titling in worksheet (he makes a running correction there that is not in the manuscript). Similarly, in ch.3, he again revises in worksheet and transfers the final version to the manuscript. The title of ch.4 (23) is first entered, like its number heading, on the worksheet’s verso side. For more on title revisions, see ‘Appendix D’. He sent Forster three letters, the first when he had written ch.1, the second when “all was finished except for eight slips”, i.e. chs.2 and 3 but not ch.4, and the third when he sent the manuscript of all four chapters (Life 472K:9243). The first three chapters take up thirty-two MS pages, and the initial final chapter adds another ten pages. So even allowing for irregularity of hand and spacing at the start of composition, he would know that, in his enjoyment of a “great plunge […] into the story”, he had overwritten No.1 by many printed pages. After a two-year break, perhaps needing the reassurance of composition, he quite uncharacteristically paid little attention to his instalment boundary.

RH

Summary notes for chs.1–3: (12), (15), (16) & (19)

For chs.1 and 2, partly because the titles are teasingly uninformative, Dickens gives their subject. For ch.3, he juxtaposes Dombey and Susan, whom he intends to be “a strong character […] throughout the book” (see the final paragraph of endnote 42). All four notes are corroded, some more than others. Entry 16 “also Mis(s Tox)” is a separate entry, using a non-corroding ink like that of (8), (14) and (18) but made with a thicker nib or heavier hand. He is perhaps considering how to put right the omission of Miss Tox in the chapter record of ch.2 (and in the number plan). The entry of her name here, and its deletion, is another sign of uncertainty, in this instance over the scope of the worksheet record. At this early stage, Dickens consistently treats the left-hand as a number plan and the right-hand half as a chapter record, apparently entering the few summary chapter notes altogether, after completing the first three chapters.

LH

These three items, perhaps initially intended as trial chapter titles, could just as well be the letterings to accompany illustrations. The first referring to ch.2 becomes the lettering for the first plate; the second becomes the title of ch.1. Dickens composes the third after finishing ch.3, but before he proposes to Forster the more ironic lettering for the second plate on 7 August “‘Mr Dombey and family’ meaning Polly Toodle, the baby, Mr. Dombey, and little Florence” (Life 473K:9283). Dickens, viewing both illustrations as a number requirement always places their lettering on the left-hand side. But because lettering usually arises from a particular text, it is often delayed until the relevant chapter has been written. Entry (8) is the only group made by reversing the page. Finding reversal inconvenient, he avoids repeating the practice. Thinking of how he might use the worksheets, he decides to avoid reversals and keep entries easy to scan and read at a glance.

Composition of an alternative ch.4 (later ch.7)

To reduce the “over-matter” which the added ch.4 creates, Dickens writes a shorter alternative chapter on Miss Tox and the Major to take the place of the one on “Wally & Co”.45 Forster objects to the change that it “might damage his interest at starting”. Dickens agrees “Strength is everything” (Life 474K:9297), implying that he felt it especially important, early on, to capture the reader’s interest in both the main storylines. Balancing the longer ch.4 (and the prospect of more deletions) against the alternative, Dickens prioritises what is more important for the novel as a whole. He also begins to use a smaller hand for the manuscript, with less space between words and between lines. The reductions, applied consistently from No.4 on, make it easier for him to estimate pages of manuscript as pages of print, and thus to calculate how many pages of print remain as he composes.46

RH

Broken underlining of titles of chs.1–3

They are probably made altogether, perhaps in a rush. Swiftly made black lines such as these usually corrode.

Chapter number heading and title for ch.4: (20) & (21)

Once the decision is made to retain the initial ch.4, its headings—already entered on the back, carefully laid out and capitalised—are squeezed onto the front, without capitals or underlines, a hurried final entry for the sake of the record. Transferring the title to the front is another practical decision that shows Dickens is thinking of how he might use the worksheet later (cf. the comment on reversal in the column opposite).

Proofs

The decision to retain the longer fourth chapter gives Dickens “great pangs” (Life 474K:9286). About thirty deletions have to be made, all to chs.1–3, but none to ch.4, which was probably at the printers.47

[Editor’s note: references above to Forster Life are (1) to Ley’s edition and (2) to ebook 25851 in Project Gutenberg downloaded to Kindle (see p.7)].

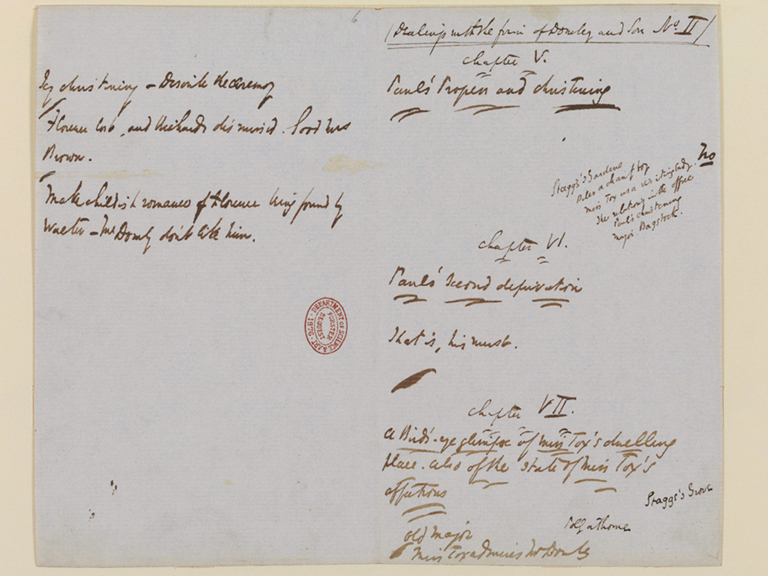

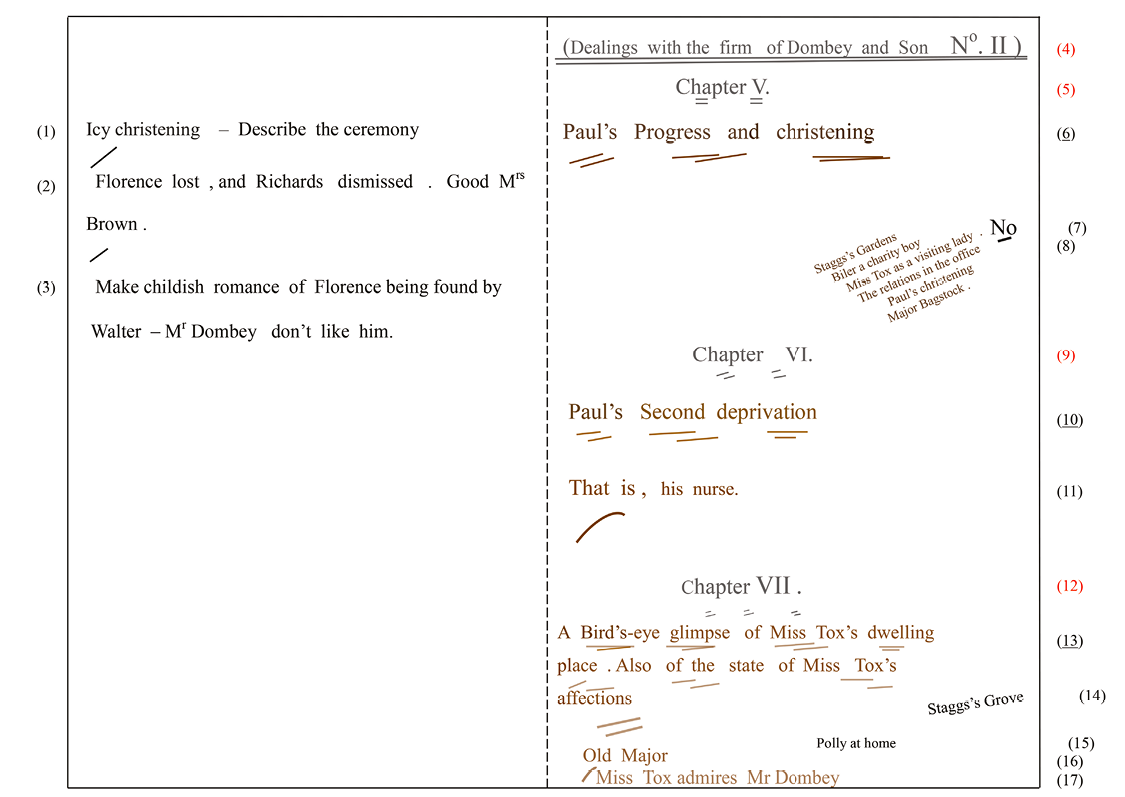

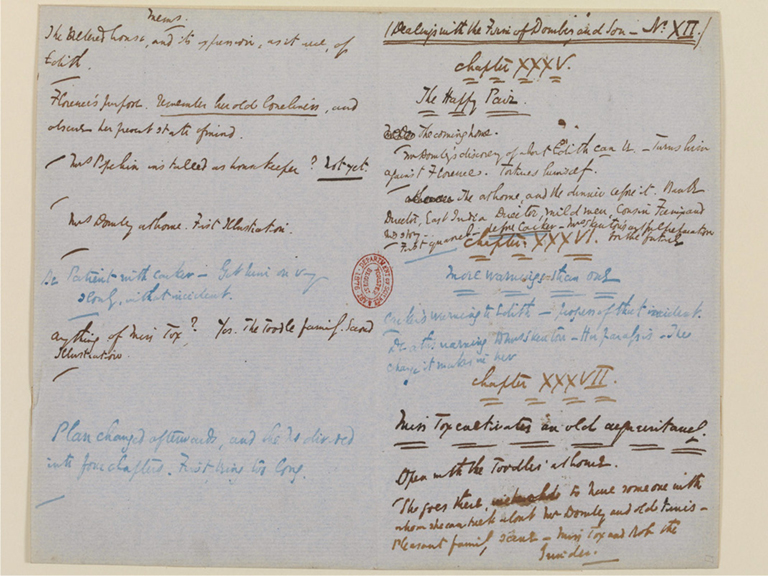

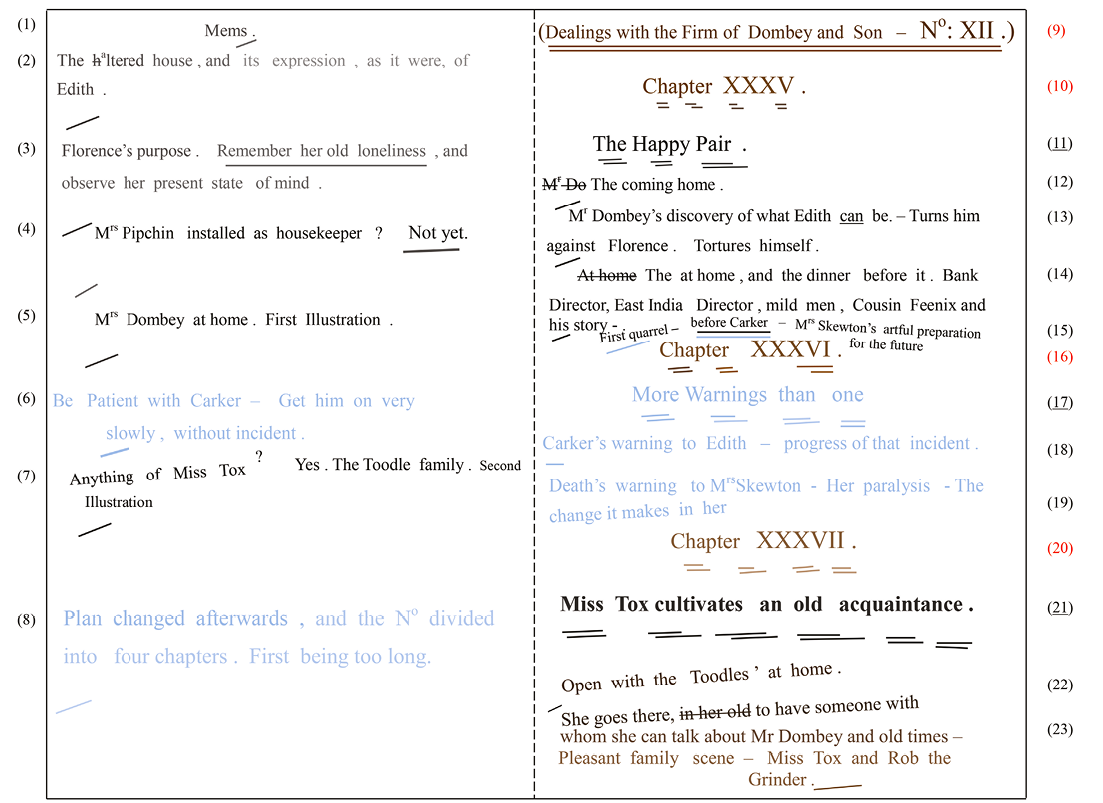

Worksheet for No.2

Image No.2012FE1506 (reduced): Forster Collection, National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum (2015). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Click here to view a 'zoomifiable' version.

Transcription of Ws.2

Commentary and order of entry (Ws.2)

Dickens begins No.2 on 8 August, writing with “infinite pains”, and finishing in the first week of September. The rest of September and early October are given over to his Christmas book for 1846, The Battle of Life. “You can hardly imagine,” he writes on 30 August “what infinite pains I take, or what extraordinary difficulty I find in getting on FAST. Invention, thank God, seems the easiest thing in the world; and I seem to have such a preposterous sense of the ridiculous […] as to be constantly requiring to restrain myself from launching into extravagances in the height of my enjoyment” (Life 423K:8591). The “pains” arise, he supposes, from the long gap between Dombey and his previous novel, and from writing for the first time while living abroad without access to the stimulus of London.48 Nevertheless, he is drawn into the wealthy English speaking community in Lausanne that forms “an agreeable little circle” to whom he reads the first number on ?19 September and the second on 10 October to the “most prodigious and uproariness delight of the circle” (Life 477K:9366). On 31 October, No.2 for November 1846 is published.

RH

Discarded entries (probably pre-format plans): (7), (8), (14) & (15)

Six items (8) on a slant, near the right-hand edge, and two others (14) and (15), directly below towards the bottom of the page, are all written in “smallhand”. Most of list (8) are ideas for this number, though one is for No.4; the two misplaced below (14) and (15) are for a narrative on the Toodles’ home and family. The six entries in (8) cover material that will be considerably reordered: the christening and the charitable gesture that separates Rob from his family to ch.5; “Staggs’s Grove” (perhaps its earlier title) and “Polly at home” to ch.6; the “old Major” to ch.7; and the first extended account of the office to ch.13. The entry “Miss Tox as a visiting lady” may refer her as a visitor to the Dombey house (ch.1), or to her calling on Queen Charlotte’s (as reported in ch.2) or more probably to the development of her visit to the Toodles (reported in ch.2 but not dramatized until much later in ch.38). These entries appear to be ‘pre-format’ notes, i.e. among the very first notes on the early numbers that Dickens jotted down before he had devised the worksheet format. Setting them aside is a result of two key decisions that accompany the division of the worksheet into two halves. Firstly, to always position ideas for the number as a whole on the left-hand side, and secondly to limit all entries on the right-hand side to part heading and chapter number, title and description. If the above are pre-format entries, as seems likely, the “No” of (7) applies to all eight.

RH

Preliminary headings: (4), (5), (9) & (12)

Reverting to the opening procedure of Ws.1, Dickens now enters the longer title with the number of the part issue, followed by three chapter number headings spread evenly down the page.

LH

Plan for the number: 1→ch.5; 2 & 3→ch.6

These notes, written fluently on the same occasion, move smoothly though aspects of the opening and middle chapters. Each entry is twofold giving the subject and some development of it. Dickens already has their shape in mind, though not their detailed structure. In (3) he is imagining Florence speaking, rather than Walter. Compare Walter’s speech to Cuttle that Dombey “does not like me” (209223) with Florence’s cry at the prospect of saying goodnight to her father “Oh no no! He don’t want me” (3535), where the repetitive “no no” and “don’t” is used to typify the speech of a young child. Many contemporary aspiring middle class would expect Dombey, as the head of a respectable and wealthy family, to disapprove of her association with a junior clerk; Dickens deflects their disapproval somewhat by always avoiding nonstandard language when Walter speaks.

MS and RH: (6)

Composition and titling of ch.5

Dickens revises the title as he writes the chapter, and transfers the final version to the worksheet.

MS

Composition and titling of ch.6

Dickens, happy in his choice of a title that looks back to Paul’s first loss in ch.1, enters it at start of composition.

RH

Titles and descriptions of chs.6 and 7: (10), (11), (13), (16) & (17)

Similarity of hand and progressive corrosion confirms that titles and descriptions are entered at the same time.

For the history of the revision in the manuscript of the title of ch.4 (later ch.7), see ‘Appendix D’, ch.7 p.182. When Dickens transfers the revised title of ch.4 to ch.7 in Ws.2, he revises it a second time. Adapting the proofs of the initial ch.4 for ch.7, he appears to copy in the title from the worksheet and, as he does so, to tighten its sentence structure. (Alternatively and perhaps less likely, he may enter the title in the worksheet from his memory of the corrected proofs of ch.4, and misremember its punctuation, in which case the second revision of the title is first made in the proofs).

Progressive corrosion begins with the title of ch.6 and continues to the end, confirming that Dickens makes these entries at the same time. The two summary entries for ch.7 are separated by a slash (used on the right-hand side for the first time). They correspond to the two contrasting concerns of the chapter the Major’s disbelief at being passed over, and Miss Tox’s romantic feelings for Mr. Dombey.

Forster corrects the proofs with Dickens’s consent. He had already “put the drag on” in ch.5 so as not to offend Christian sects. He now adds a conciliatory stuffy paragraph on the sacrament of baptism; the paragraph begins “It might have been well” (6062). Just before that addition, he cuts a comparison of the font to a child’s toy.49 He also deletes the two closing sentences of ch.7 that prepares for the next number to open with Paul’s schooling.50 The deletion of this plant for the opening of No.3 reflects the outcome of a choice under consideration at the time, to postpone schooling to No.4 and “kill” Paul in No.5, and “make number three a kind of halfway house between infancy and Paul being eight or nine”, in contrast to the first paragraph of the outline to Forster “When the boy is about ten years old (in the fourth number), he will be taken ill, and will die” (see endnote 42). Dickens raises the possibility with Forster at the beginning of October, after writing No.2 but before starting No.3 (Life 477K:9358).

The decision to postpone opens the way for an extended portrait of Mrs Pipchin’s “establishment”, the first of Dickens’s explorations in fiction of painful childhood memories. He writes to Forster on 4 November “I hope you will like Mrs. Pipchin’s establishment. It is from the life, and I was there—I don’t suppose I was eight years old; but I remember it all as well, and certainly understood it as well, as I do now. We should be devilish sharp in what we do to children” (Life 479K:9396).

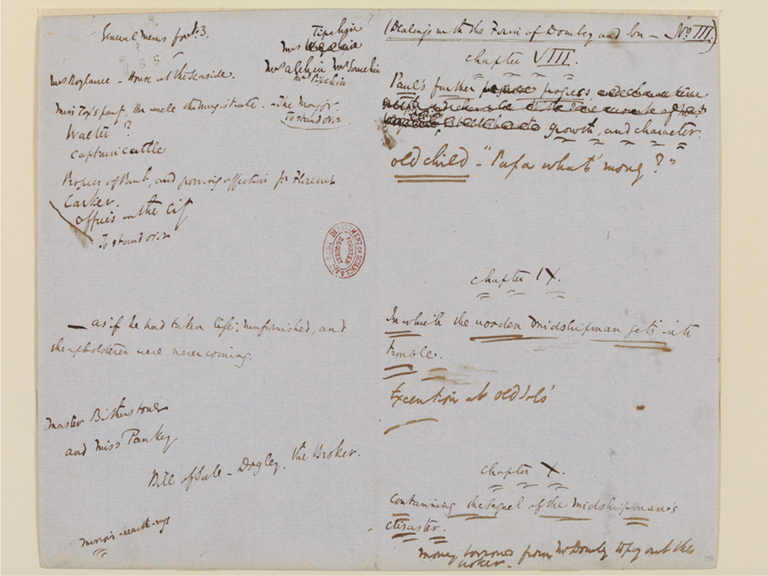

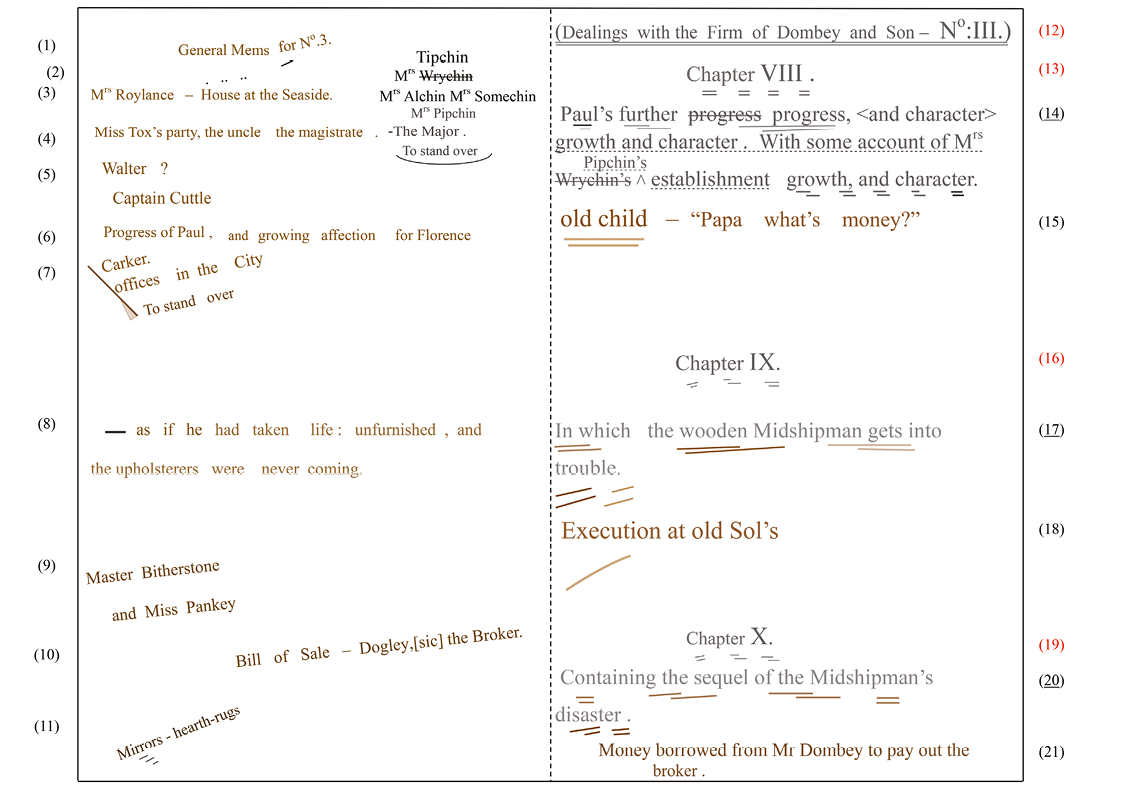

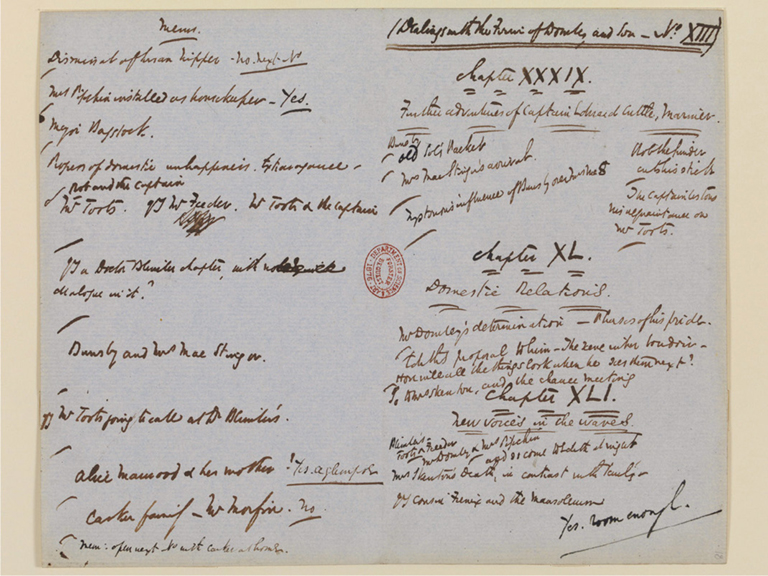

Worksheet for No.3

Image No.2012FE1486 (reduced): Forster Collection, National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum (2015). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Click here to view a 'zoomifiable' version.

Transcription of Ws.3

Commentary and order of entry (Ws.3)

Immensely relieved by the “BRILLIANT!” sale of No.1, Dickens is anxious to sustain its success (Life 477K:9363). He writes to Forster that “A week of perfect idleness […] has brought me round […] I am quite glad to write the heading of the first chapter of number three to-day [26 October]. I shall be slow at first, I fear, in consequence of that change of plan [see ‘Proofs’ in Ws.2 p.45]. But I allow myself nearly three weeks for the number” (Life 478K:9369). On 4 November, he is half through it, on 7 November he is in the “agonies” of its last chapter, and on 9 November, as Forster says ‘all was done…marvellously rapid work’ (Life 441K:8977). Dickens hurries to complete the instalment early, in order to prepare for the family’s move to Paris the following week. He composes fluently, inspired by the memories of childhood that were beginning to preoccupy him. The gap between completing the number and his deadline for delivering copy to the compositors (at least five days prior to issue) is narrowing. On 30 November, No.3 for December 1846 is published.

LH

Plan for the number (including some pre-format plans, cf. Ws.2):

(1); (3)→ch.8; (4); (5)→chs.9 & 10; (6)→ch.8; (7)→ch.13

Dickens’s choice of word in (4) repeats the lettering for the first plate of No.1, where Miss Tox’s “party” is the Toodles family, and repeats the “magistrate” detail of ch.5 (5254).51 These untypical repetitions suggest that he may have been making notes here for the opening numbers before he began work on No.1. The sheet, consisting of entries (1)–(7) excluding (2), may have begun as some “General Mems” for the first few numbers, Dickens’s earliest notes (with Ws.28, 14 & 15) jotted down before he devised the worksheet format (hence the addition later “for No.3”, see below).

Dickens retains the heading “General Mems” because, in comparison with Ws.1 and 2, its left-hand entries go beyond the current number. The heading is not used again until Ws.19&20, when he is once again considering the story as a whole.

He inserts “for No.3” after the heading (2), adds the two “To stand over” entries, jettisons a party at Miss Tox’s—perhaps attended by her uncle and part of a more extended satire of Miss Tox, apparently abandoned—and postpones both the Major (4) and James Carker in the city offices (7). He is left with early memories of Mrs Roylance (3), Walter Cuttle (5), and the development of Paul (6), particularly the boy’s growing attachment to Florence.52 The concentration on Paul, as he begins Ws.3, flows from the decision made between Nos.2 and 3, to lengthen Paul’s story to five numbers (see above “that change of plan”; also the final comment in ‘Proofs’ in Ws.2 p.45).

RH

Preliminary headings: (12), (13), (16) & (19)

LH and RH

Additional number plan: (2)

Titling ch.8: (14)

Dickens begins by devising names for Mrs Roylance as part of the number plan, first “Alchin”, then “Somechin”. When he tries out the next name “Wrychin” (2), he incorporates the name into his third attempt at a chapter title in (14). Still not satisfied, he tries out “Tipchin” and then “Pipchin” in (2), which he inserts into the revised title in (14)—again moving between the left and right-hand half. This version is then copied to MS, where the revision process continues during composition (‘Appendix D’, ch.8 p.183).

Caught up in the memory of Mrs Roylance, Dickens feels compelled to find a name that rings true for a character “from the life”. It is his detailed memory of Mrs Roylance that sways his judgment of the second illustration of Paul and Pipchin at the fireside “It is so frightfully and wildly wide of the mark” (Life 478K:9383). Despite his outrage, he is becoming aware of the difficulty that his retentive memory for visual detail posed for his illustrators.53

MS

Composition and titling of ch.8

When Dickens transfers the title from the worksheet, he adds what is probably an ironic reference to Mrs Pipchin’s “Establishment”. During the writing of the chapter, he reconsiders the emphasis, deletes the phrase, and limits the title to Paul (see reference above).

LH

Further number plan: (8)→ch.11; (9)→ch.8; (10) & (11)→ch.9

Dickens begins to use the lower part of the left-hand side. He notes ideas for individual chapters, here an evocative comparison (8), children’s names (9), a plot detail (10), and a startlingly random but significant juxtaposition of objects (11). These are all written with a similar hand—and with (9) and (10) written on a slant—suggesting that, although his general practice is to work closely on each chapter in turn, he is at the same time imagining characters, places and other details that will find a place somewhere in later chapters.

He holds back the striking entry (8) for the end of the opening chapter of the next number (with amendments to its punctuation) in line with his decision to extend Paul’s story. The entries as a whole signal an important change in the use of the worksheet. He adapts its format to include prospective details for individual chapters before they are written, in this instance using the lower left-hand.

MS

Composition and titling of chs.9 and 10

The long ch.8 has already taken up fifteen MS pages. Ch.9 fills a further ten. Consequently, ch.10 begins on MS p.26. Dickens is probably by now working to a notional 27 or 28 MS pages to thirty-two pages of print, in which case he knows, even as he writes, that cuts will be needed. The number of pages taken up by each chapter as published in each instalment is given in ‘Appendix A’ (see the ‘Key’, p.167, for how chapter length is calculated there).

RH

Titles of chs.9, 10: (17) & (20)

Similarity of hand suggests that Dickens transfers both titles to the worksheet at the same time.

Description of chs.8, 9 & 10: (15), (18) & (21)

Dickens emphasises a common theme, perhaps entering the descriptions of (21), (15) and (18) in that order (see their progressive loss of density and increasing corrosion). After adding, for some reason an extra double underline to (17)—haste rather than a blotting error—he finishes ch.9’s description and the worksheet, with a flourish.

Proofs

As expected, the proofs overrun by four pages. Dickens takes out about two and a half pages, leaving the rest to Forster (Life 479K:9400). The longest of the cuts in ch.10 concerning Miss Tox’s attachment to Dombey—and many early ones in ch.8 that are not so long—are restored in Project Gutenberg’s edition ebook 821, chs.8 and 10).

More cuts are avoided by reducing gaps between chapters and adding a line to each printed page—both devices of last resort that were available but not invoked for No.1, perhaps because they might not be sufficient to accommodate the scale of the cuts required.

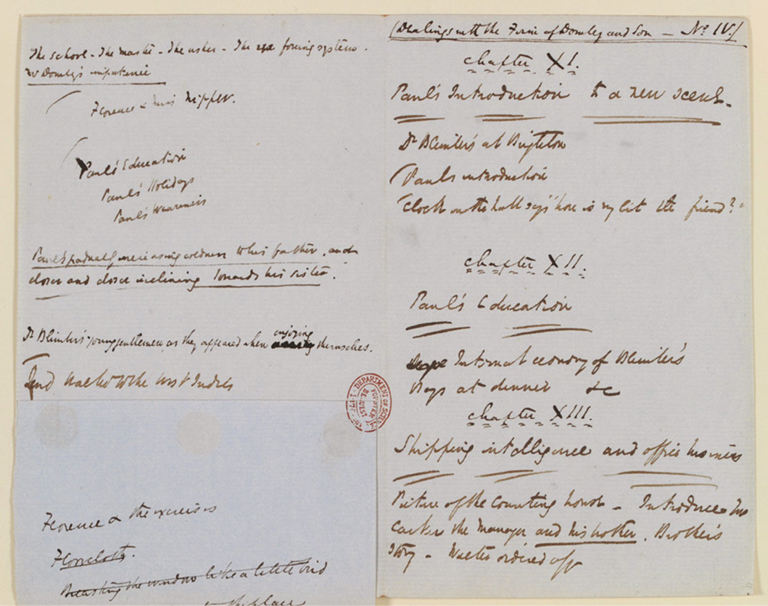

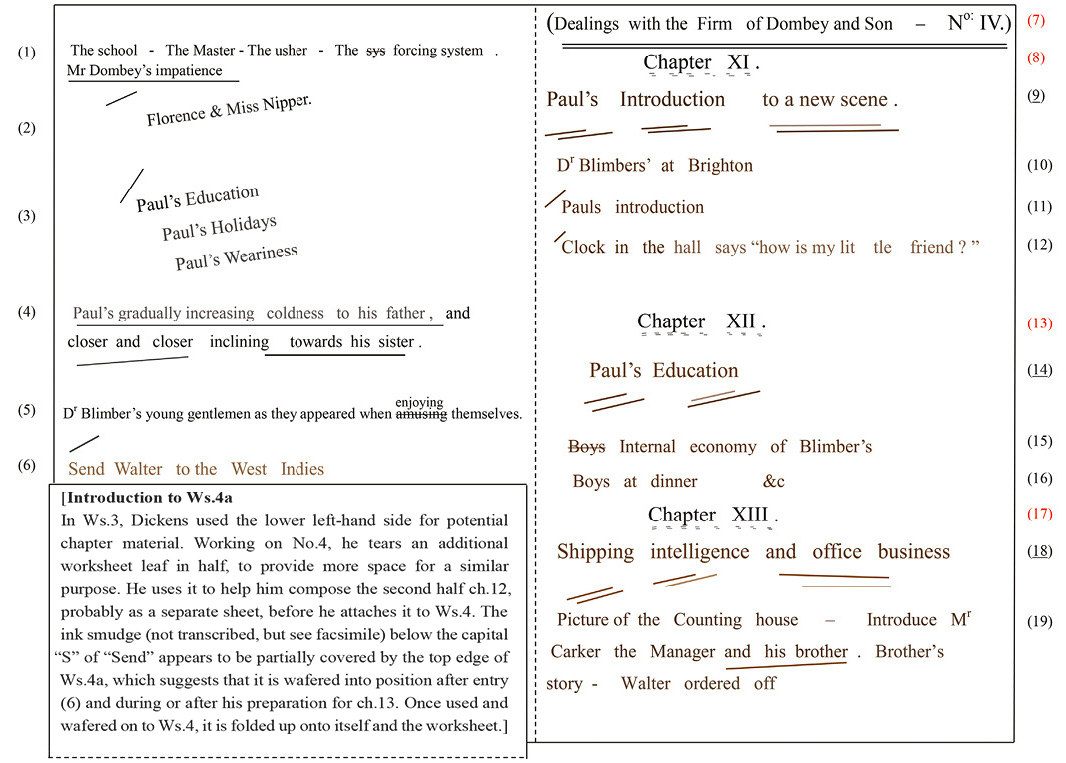

Worksheet for No.4

Image No.2012FE1488 (reduced): Forster Collection, National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum (2015). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Click here to view a 'zoomifiable' version.

Transcription of Ws.4

[Introduction to Ws.4a In Ws.3, Dickens used the lower left-hand side for potential chapter material. Working on No.4, he tears an additional worksheet leaf in half, to provide more space for a similar purpose. He uses it to help him compose the second half ch.12, probably as a separate sheet, before he attaches it to Ws.4. The ink smudge (not transcribed, but see facsimile) below the capital “S” of “Send” appears to be partially covered by the top edge of Ws.4a, which suggests that it is wafered into position after entry (6) and during or after his preparation for ch.13. Once used and wafered on to Ws.4, it is folded up onto itself and the worksheet.]

Commentary and order of entry (Ws.4)

The Dickens entourage—himself, wife, children, servants and luggage, in two carriages and a wagon—leaves Lausanne on 16 November, arriving in Paris on the 20th. For days, he searches for a house to rent, organises the household and explores the city. “I tried to settle to my desk, and went about and about it, and dodged at it, like a bird at a lump of sugar.” By 6 December, he has “written five printed pages” (Life 447K:9094). In another nine days, he completes the number, some ten days before his deadline. On the 15th he goes to London, bringing the finished manuscript with him. He stays until the 23rd, partly to read the proofs and partly to settle details of the publication of the Cheap edition, his first collected works (see Life 448K:9107). The “new preface” he had just written for Pickwick Papers reveals some of his artistic ambitions for Dombey and Son.54 On 31 December, No.4 for January 1847 is published.

RH

Preliminary headings: (7), (8), (13) & (17)

Dickens returns to the procedure of Ws.1, making these entries first (cf. Ws.1–3).

LH

Initial number plan: (1)→ch.11; (2) & (3)→ch.12 ; (4)→chs.11 & 12

Four groups in the same hand are separated by slashes and positioning. In entry (1) Dickens notes the organisation of the school and its methods that are well matched to Dombey’s ambitions for Paul. In (2), Susan now a “Miss Nipper” is a companion—and foil—to Florence. In (3) he proposes three stages to Paul’s progress; the first becomes a title for ch.11 (later transferred to ch.12); the other two will be held over for No.5.

Paul’s turning to Florence and away from his father (4) is underlined, like Dombey’s impatience, as an ongoing and, in Paul’s case, a growing feeling (cf. Ws.36 p.47).

MS

Composition and titling of ch.11

Dickens writes a long recapitulation, adding to the portrayal of Pipchin by her meeting with Dombey, now impatient to push ahead with Paul’s formal education. He initially titles ch.11 “Paul’s education” perhaps expecting to write further into the Blimber material. Then he limits the remaining pages to “introducing a new scene”, arresting the action at the moment of Paul’s abandonment. He can now use Ws.38—the image of the child sitting alone in a desolate and empty newly rented house, so expressive of loss—as a curtain to the chapter. Number openings, usually with strong links with the previous number, are often, as here, expansive and improvisatory.55

LH

Additional number plan: (5)→ch.12; (6)→ch.13

Dickens uses his smallest hand in (5) to get the lettering for the first illustration on one line, probably as he is writing ch.11. The lettering is sent to Browne (?6 Dec 1846, L.4:677) with a lengthy account of the general context (from the completed ch.11) and a brief description of the subject in ch.12 (yet to be written).

Despite the letter, Browne adds to the number of pupils (Dickens writes there are ten). He also supplies a well-developed visual contrast of his own between the formally clothed pupils and the other boys who are free to enjoy the pleasures of the seaside (cf. his final image of a young Florence, with Paul on the seashore in his frontispiece for the finished novel p.163). Although Browne’s subject of both plates for No.4 comes from the same chapter (ch.12), he maintains a strong contrast between them, by inventing the setting for his second illustration, an indoor scene at night (see “Paul’s exercises”).

For all other numbers, Browne finds (or is given) subjects from different chapters, presumably to heighten visually the contrast between storylines. Like other second illustrations, this one requires less detail than the first making it easier for Browne and his engravers prepare it in time.

Chapter plan: Ws.4a→ch.12

Ws.4a is a plan for the second half of ch.12 probably not attached to Ws.4 until entry (6) is made (see above ‘Introduction to Ws.4a’ p.51).

MS

Composition and titling of ch.12

Dickens uses the initial but discarded title of ch.11 for ch.12. He probably has Ws.4a alongside him to help him order the later parts of the chapter, including its ending (see below Ws.4a p.54).

RH

Titles and summaries for chs.11 & 12: (9), (10), (11) & (12); (14), (15) & (16)

Throughout the right-hand side, hand, quill and ink are similar. The hand is rapid, especially in the descriptions, with a great deal of elision of letterform. Both titles are similar in their generous layout, slant and hand. The descriptions of chs.11 and 12 are basic summaries, giving a setting in (10) and (15) and the central episode in (11) and (16). Among Paul’s reactions in ch.11, Dickens picks out a particularly significant moment—his sensation of the great clock’s machinery that begins and ends his first experience of Blimber’s (12). The description of ch.12 is briefer and even hastier, the letters losing definition and increasing in their slant.

The “etc” probably refers to the rest of the repetitive daily tasks and routines, rather than the materials touched on in Ws.4a, though these also act as a record of the chapter, as well as an aid to its composition.

LH

Further number plan: (6)→ch.13

Dickens decides to remove Walter from the narrative until Florence is old enough for the romance plot to be resumed. After this entry, he wafers Ws.4a to the bottom of the left-hand half, overlaying the smudge in (6) (see below, top left of facsimile Ws.4a p.54).

RH

Dickens allocates a generous space for the chapter title as in chs.11 and 12, but this time leaving a gap for the title to be inserted later. The description is the first plan for a whole chapter. The directive “Introduce” is a decisive indication of planning. In composition, he reworks the plan, contriving to give Dombey a prominent part in the picture of the office, in the drama that follows and in the dispatch of Walter—all understandable additions and departures when reworking a plan, but unlikely omissions in a summary.56 Throughout the plan, he uses the same sprawling hand as before. Writing in haste, he avoids re-dipping by reducing pressure on the quill, which thins the density of the ink (see the progressive loss of density in (12) and (19)).

MS and RH: (18)

Composition and titling of ch.13

During composition, once he is satisfied with the title after much revision, Dickens transfers the final version into the gap left for it in the worksheet (see ‘Appendix D’, ch.13, p.183).

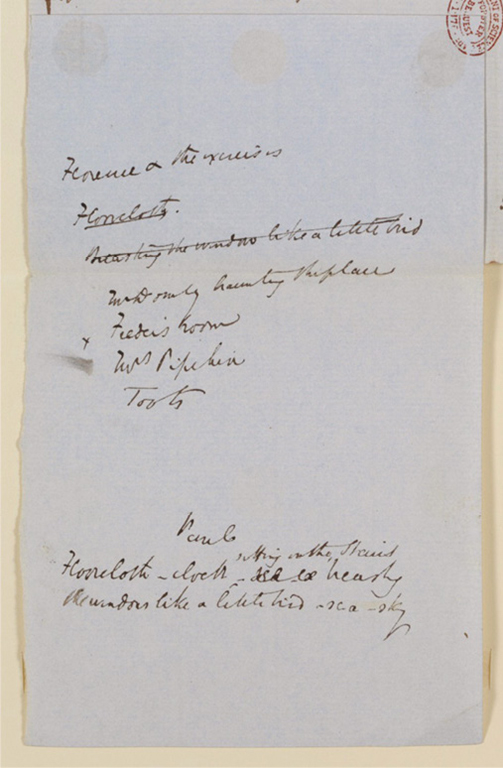

Facsimile of Ws.4a

Image No.2012FE1488 (reduced): Forster Collection, National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum (2015). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Click here to view a 'zoomifiable' version.

Transcription of Ws.4a

Commentary on Ws.4a

This is the first of the four leaves that Dickens attaches to a worksheet. He wafers the leaf to the bottom left-hand of Ws.4, probably after making entry Ws.46 (see the tail end of the “S” of “Send” that is covered by Ws.4a, shown top left in the facsimile above). He spreads a list of entries down and across the page, writing in a fast hand, as though hurrying to keep abreast of thought. All are linked to ch.12, beginning “Oh Saturdays!” (162–70177–81).

The resonance that each entry has for him can be sensed from what it becomes in the manuscript, for example:

- Florence’s scheme to help Paul, in which love transforms learning.

- Paul’s withdrawal into the inner life of his imagination, seeing patterns in the floor covering.

- His helplessness and longing to escape is imaged as an imprisoned bird (cf. 170181).

- Dombey isolated and preoccupied is cut off by his ambition for Paul.

- The compensations of his own room for Feeder “the organ grinder” are prepared for in passing (159169), with a tiny ‘x’ to the left of the name, perhaps to indicate postponement—a reminder to describe the room later (see ch.14, 187198–99).

- Pipchin, still very much present in Dickens’s imagination—note the slight increase in size of the name—is in charge of Florence and so occasionally at Blimber’s; she interrupts Toots’ conversation with Paul.

- Slowly, each appearance of Toots deepens Dickens’s conception of him; he uses him here to draw out the portrayal of Paul (cf. 152–53162–64, 159169).

- He creates a second list by moving (2) and (3) into a separate list of those entries that concern Paul alone. The order of the items in (8)—like those in Ws.5a—has both an emotional and a narrative logic (168–70179–81).

The act of making a second list gives a glimpse into Dickens’s inventive intelligence. He reworks heightened moments in his imagination of the child’s inner life until they join and take on a narrative order, which is then incorporated into the longer text that he has perhaps already imagined. Laying out on the page the sequence of ideas in preparation for a passage of narrative is a significant development in his use of the worksheet. In this respect, Ws.4a—laid out as narrative focalised on the ailing Paul—prepares for the notation of Ws.5a.

Worksheet for No.5

Image No.2012FE1496 (reduced): Forster Collection, National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum (2015). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Click here to view a 'zoomifiable' version.

Transcription of Ws.5

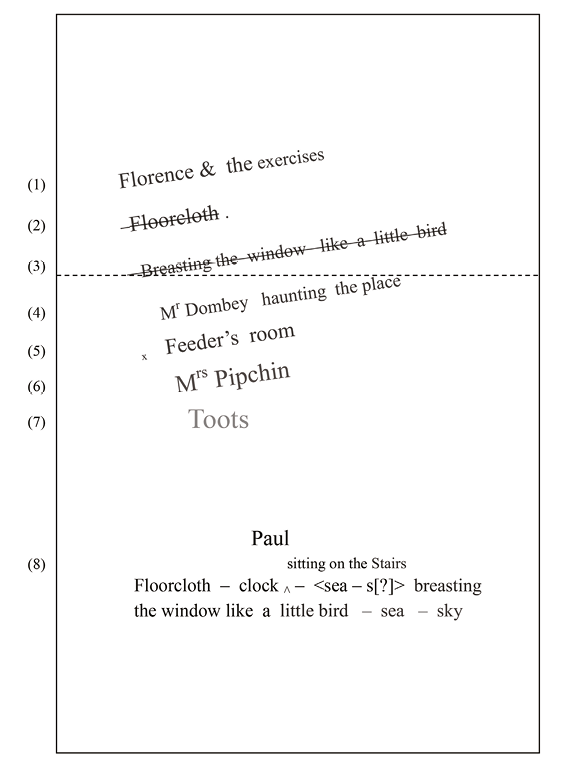

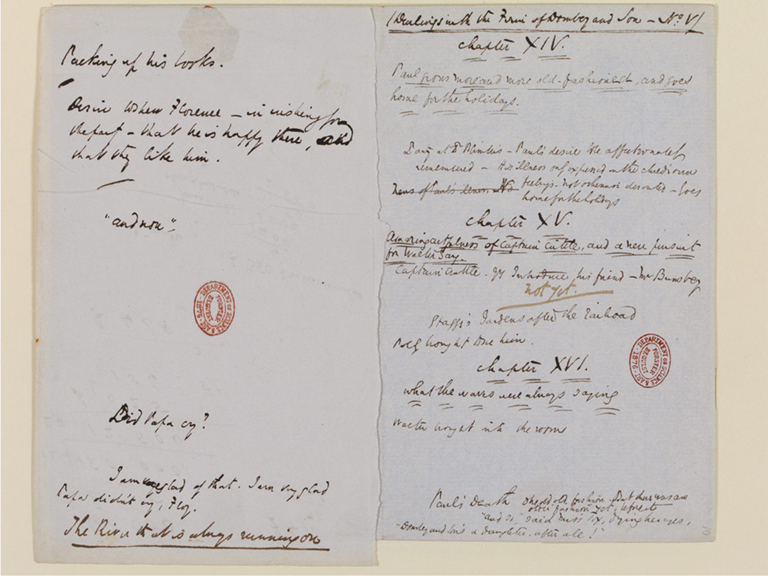

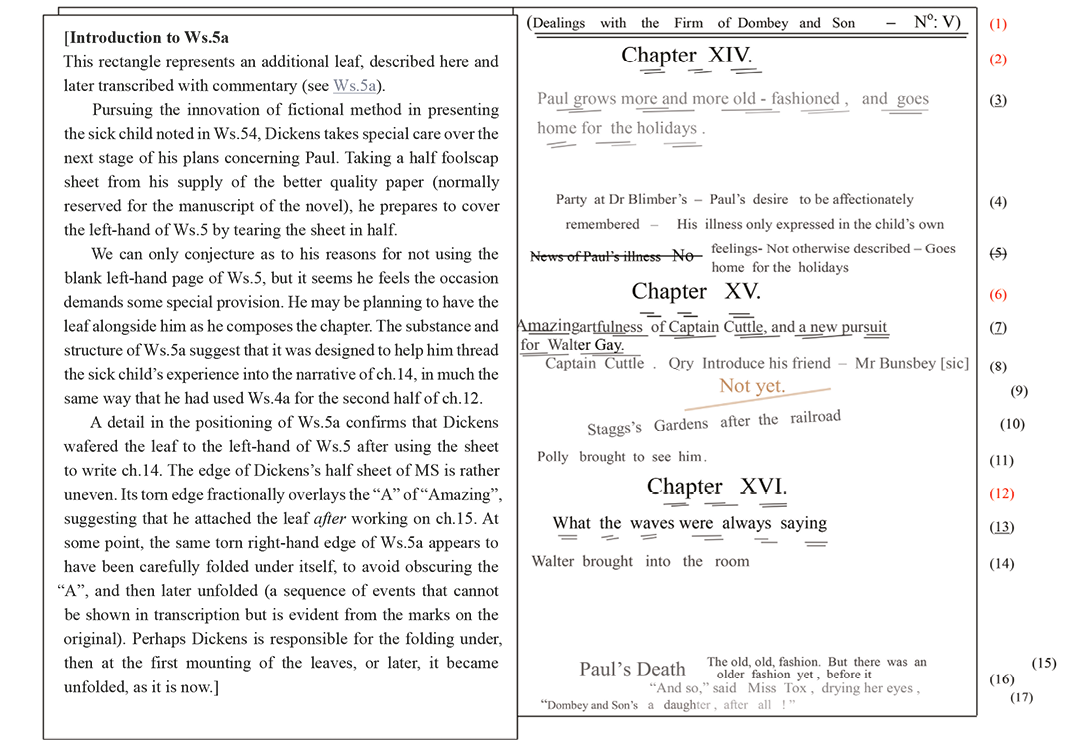

[Introduction to Ws.5a This rectangle represents an additional leaf, described here and later transcribed with commentary (see Ws.5a).

Pursuing the innovation of fictional method in presenting the sick child noted in Ws.54, Dickens takes special care over the next stage of his plans concerning Paul. Taking a half foolscap sheet from his supply of the better quality paper (normally reserved for the manuscript of the novel), he prepares to cover the left-hand of Ws.5 by tearing the sheet in half.

We can only conjecture as to his reasons for not using the blank left-hand page of Ws.5, but it seems he feels the occasion demands some special provision. He may be planning to have the leaf alongside him as he composes the chapter. The substance and structure of Ws.5a suggest that it was designed to help him thread the sick child’s experience into the narrative of ch.14, in much the same way that he had used Ws.4a for the second half of ch.12.

A detail in the positioning of Ws.5a confirms that Dickens wafered the leaf to the left-hand of Ws.5 after using the sheet to write ch.14. The edge of Dickens’s half sheet of MS is rather uneven. Its torn edge fractionally overlays the “A” of “Amazing”, suggesting that he attached the leaf after working on ch.15. At some point, the same torn right-hand edge of Ws.5a appears to have been carefully folded under itself, to avoid obscuring the “A”, and then later unfolded (a sequence of events that cannot be shown in transcription but is evident from the marks on the original). Perhaps Dickens is responsible for the folding under, then at the first mounting of the leaves, or later, it became unfolded, as it is now.]

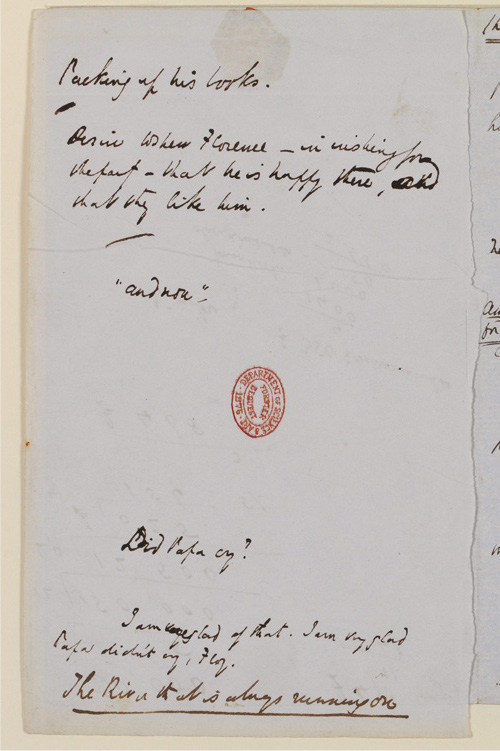

Commentary and order of entry (Ws.5)

Dickens begins No.5 soon after Christmas 1846 (probably 31 December) and finishes on 15 January, once again about ten days before his deadline. Forster arrives on the 16th ‘The greater part of the night of the day on which it [No.5] was written…he [Dickens] was wandering desolate and sad about the streets of Paris. I arrived there the following morning on my visit; and as I alighted…a little before eight o’clock, found him waiting for me at the gate of the post-office bureau’ (Life 481K:9442). On 31 January, No.5 for February 1847 is published.

RH:

Preliminary headings: (1), (2), (6) & (12)

Dickens follows his established routine.

Plan for ch.14: (4) & (5)

He puts number planning aside and instead plans for the first of two chapters concerning Paul. He begins by entering a note of the chapter’s ending, the news of Paul’s illness, adds “No”, and then deletes the whole entry (5). In its place—still leaving half of the space blank for the title—he plans the chapter from its central episode (the party) onwards. He notes Paul’s displacement of feelings of loss by concern for others, and finally his intention to present illness exclusively from the sick child’s viewpoint (4).

Ws.5a

Dickens breaks off from Ws.5 to prepare Ws.5a. The decision to focus on the ailing Paul is “a difficult, but a new way of doing it […] and likely to be pretty” (Life 404K:8229) something he had in mind since at least the 5th of July.57 His use of the word “pretty” to describe the innovation is a characteristic defensive understatement. Aware of some of the difficulties, he makes special preparations in Ws.5a.

MS

Composition and titling of ch.14

Anticipating that the final chapter will be short, Dickens feels free to improvise an unusually long lead-in to the main episode the end-of-term party; it becomes ten printed pages of about seventeen (see ‘Appendix A’ p.165). As he writes ch.14, he weaves the substance and structure of Ws.5a into its composition. He also enlarges its title, revising it twice (‘Appendix D’ p.181). The leave-taking after the party is one of many extended departures that intensify pathos and the general mood of the novel (cf. the procession of farewells in chs.16, 44 and 57).

RH

Title of ch.14: (3)

Dickens copies the final version from manuscript into the gap left for it in the worksheet.

Plan for ch.15: (8), (10) & (11)

Leaving a line for the title, Dickens enters note (8), which presumably points to the first episode that ends with Cuttle seeing Walter off on a long walk. As in the other two chapters, Dickens defines an endpoint (11). The challenge then is to devise a plausible and effective narrative that links (8) to (11). He considers the introduction of Bunsby (9), leaving it as a possibility to be settled during composition. Entry (10) on the progress of the railroad explains Susan’s predicament and makes more acceptable the coincidence of her meeting with Walter (in preparation for his recall). Dickens is alert throughout the novel to the different ways the development of the railway impinges on his characters.

MS and RH

Composition and titling of ch.15: (7)

Dickens ends with Walter being called back to the house, a plant for the opening of ch.16. He copies the title to worksheet.

RH

Outcome of (8) in ch.15: (9)

With a drying quill, Dickens confirms the postponement of Bunsby. The timing is conjecture; there is nothing to indicate when after writing ch.15 he made the entry (8).

Titling and plan for ch.16: (13), (14), (15), (16) & (17)

Dickens titles at once (13), as he sometimes does if certain of his choice. The style of broken underlining—many equal short strokes—may give it additional emphasis, though the style is used elsewhere, without that effect (see Ws.8 p.75). He notes that Walter is to be brought into the room (14), completing the action began in ch.15 (220236), and adding weight to Paul’s last wishes, which later are impetuously set aside by Dombey. Layout and hand suggests that he enters “Paul’s Death” (16) first, then (15) and lastly (17), as the quill begins to dry.

Ws.5a

Dickens adds a final entry to Ws.5a, the river symbol (6). He can then use Ws.5a in much the same way for ch.16 as he did for ch.14.

MS

Composition and title of ch.16

Having copied in the title, Dickens incorporates Ws.5a into the composition of ch.16. The concentration on Paul’s sensations and thoughts continues. Paul’s feelings about his father noted in Ws.5a are echoed in what he says to him in this chapter, adding gesture to words. Throughout the chapter, the “now” gathers emphasis until a final “and now” on the last page.

Similarly, the particulars of the river are developed with every repetition. As the focus is on Paul, we hear through his ears, which conveniently keeps anonymous the speaker whose mention of Walter leads to his summons. Paul makes his last wish to his father before he describes to Florence his imagined journey on “The River that is always running on”. The final narrative represents his passage into death, told in the terms that have been taught him (cf. Richards’ explanation of her mother’s death to Florence (26–2726–27)).

Dickens ends with a consolatory but qualified hope “for all who see it”, a plea to the reader not to estrange the spirits of children, then a “white line”, then a reworked version of Miss Tox’s cry (16). Her exclamation, present in his outline to Forster, is also anticipated at the end of ch.4 (see first paragraph of endnote 42).

After the experience of reading ch.16 in public, Dickens drops the exclamation from the later editions of 1859 and 1867. It was probably Forster who wrote that the sentence ‘was felt a jar at the time [1848], and too light an intrusion upon a solemn catastrophe’.58 A reading copy (1862) has “too” after “bears us to the ocean”.59

Dickens wafers Ws.5a over the left-hand half of Ws.5.

List: [1–5]

In the interval between completing the novel’s first quarter and preparing for No.6, Dickens decides to keep a what he calls a “List of Chapter Headings”. After preparing a few slightly larger leaves, he writes the chapter number and title for chs.1–16 in an even fine hand with consistent alignment and spacing, and without hesitation, probably copying from Ws.1–5 (‘Appendix C’ p.173). Once completed to the end of No.5, the list is usually compiled number-by-number. He now feels the need for a compressed record of the story’s growing complexity, which perhaps reflects some uncertainty over how reliable or useful the worksheets will be in helping him oversee his larger intentions for the novel.

Proofs

There are no proofs extant, but as five long passages in manuscript do not appear in the part issue, it is likely that they were cut at proof stage. Once again, Dickens probably already suspects he has overstepped his limit; ch.16 begins on MS p.26 and ends on p.29.60

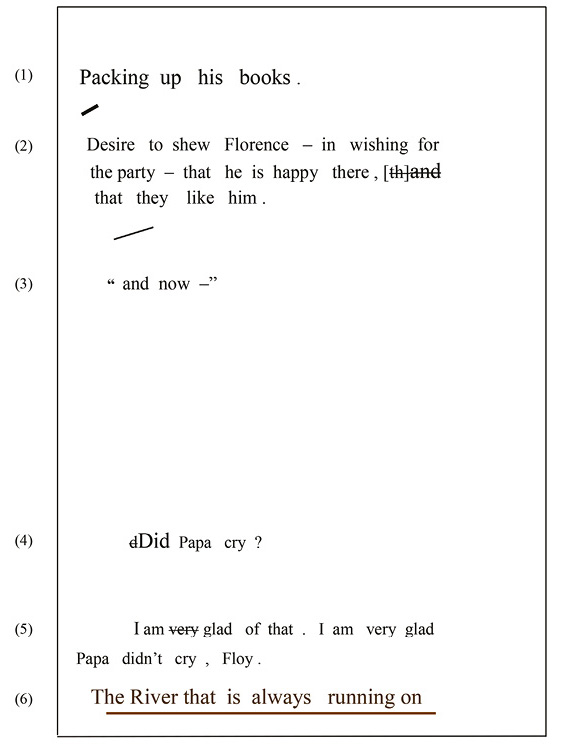

Facsimile of Ws.5a

Image No.2012FE1496 (reduced and cropped): Forster Collection, National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum (2015). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Click here to view a 'zoomifiable' version.

Transcription of Ws.5a

Commentary on Ws.5a

Instead of a number plan for No.5, Dickens prepares an additional leaf, in which all entries are concerned with the presentation of Paul. The entries are similar in hand, quill and ink, and made on the same occasion (except for the final entry). They are spread out so that they fill the page, matching their position in an imagined narrative. He appears to wafer Ws.5a over the unused side of Ws.5, after revising the title of ch.15, and probably after the writing of ch.16 (see above ‘Introduction to Ws.5a’; also ‘Ws.5a’ in the commentary on Ws.5 p.58).

Entry (1)

Dickens begins, in a slightly larger hand, describing an action representative of all of Paul’s preparations for departure that are ways of delaying and coming to terms with loss (see 193205–06).

Entry (2)

Paul’s attachment to and concern for others is noted in language appropriate to him, emphasising the present and in free indirect thought. In the text, his concern becomes more insistent as he declines; it displaces his fears, and increases the reader’s empathy. At the end of the second line of (2), “th” is over-written by a large “and”, which is then smudged and deleted. He removes childlike coordination to emphasise the repeated syntax and monosyllabic choice of word.

Entry (3)

The “and now” is in speech marks to suggest a special function, as if it is an authorial interjection interrupting Paul’s narrative. It marks a decisive stage in Paul’s illness (194207). The blank space below (3) evokes the passage of time and the progress of his sickness in the intervening narrative.

Entry (4) & (5)

In the two penultimate entries, Paul questions Florence about his father’s reaction to his arrival home. The irony of his repeated assertion of his protective feelings for his father provides an endpoint for ch.14 (204219).

Entry (6)

Finally, in a heavier hand (that later corrodes), Dickens adds the always flowing River, underlined as a recurrent symbol. With this addition, the notes—up to this point planned for ch.14—reach into ch.16, where he also repeats the “and now” (220236, 225241) and further develops Paul’s thoughts and gestures in his speeches to Florence about his father (222238, 224240).

The River, as a fact of Nature, a symbol of Time passing and a figurative allusion to death, appears at the chapter’s beginning and at its end. It carries the author’s closing plea “look upon us, angels of young children, with regards not quite estranged, when the swift river bears us to the ocean [too]!”61

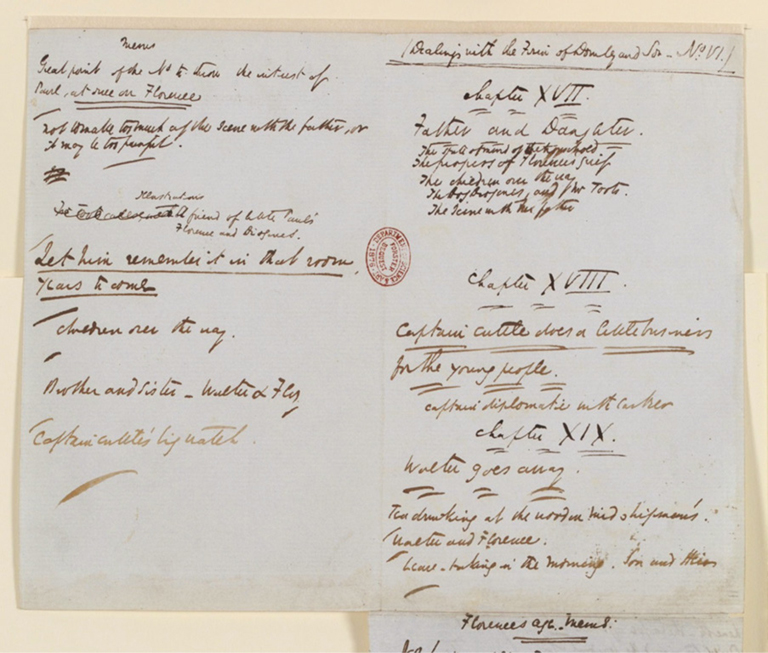

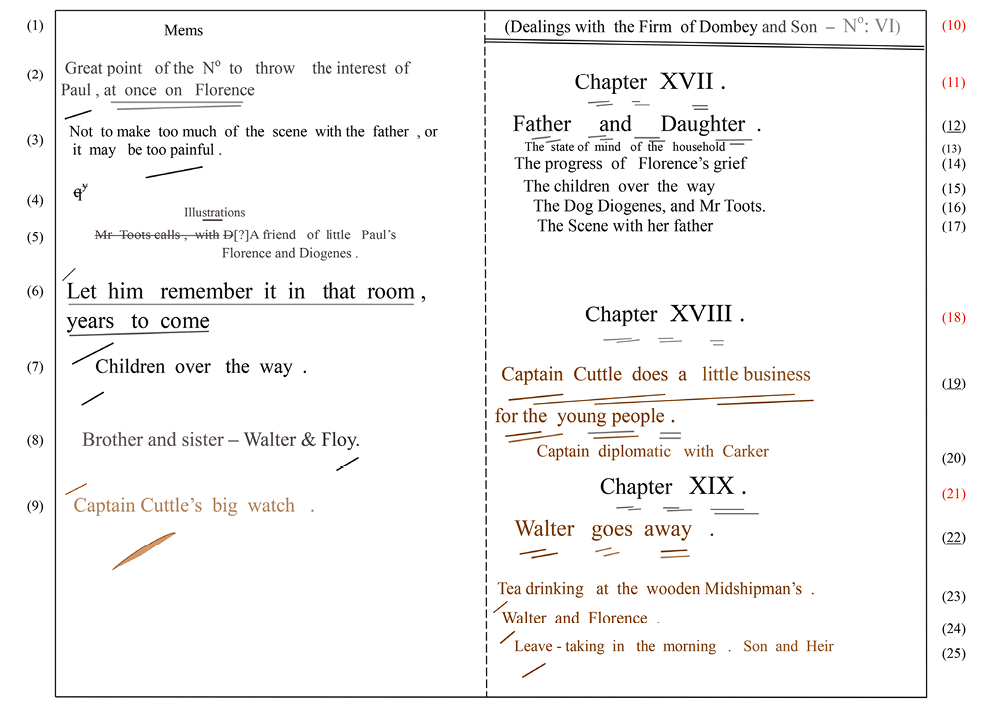

Worksheet for No.6

Image No.2012FE1494 recto (reduced): Forster Collection, National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum (2015). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Click here to view a 'zoomifiable' version.

Transcription of Ws.6

Commentary and order of entry (Ws.6)

Forster left Dickens on 2 February with his writing-table in readiness for No.6. However, on the 4th Dickens writes he is “not under weigh [sic] yet find it very difficult indeed to fall into the new vein of the story […] I will send the chapters as I write them, and you must not wait, of course, for me to read the end in type. To transfer to Florence, instantly, all the previous interest, is what I am aiming at” (Life 481–82K:9446). When Dickens receives the proof of ch.17 (later 18) and ch.18 (later 17), he discovers that the former is more than a page short of what he expected (Life 453nK:9197 n.135). He cannot wait for the proofs of ch.19, so rushes to London from Paris on the 18th to provide more text.62 On 28 February, No.6 for March 1847 is published.

RH

Preliminary headings: (10), (11), (18) & (21)

Dickens’s alignment of the number headings for three chapters slips to the right.

LH

Heading: (1)

He heads the left-hand half “Mems” for the first time. The heading signals that some strategic notes have to do with how the number plan relates to what is to come (see Ws.7, 9, 12, 13 and 15). By contrast, where he is concerned only with the number itself, he may omit a heading (see Ws.16–18). However, the distinction is not made consistently (cf. Ws.8, 10, 11 and 14).

Initial plan for the number: (2), (3), (4), (6) & (7)→ch.17 (later 18)

There are signs—in the changes of hand and positioning—of an untypical hesitancy in selecting and ordering ideas (cf. Horsman 1974, ‘Introduction’, p.xxix). Dickens is troubled by the problem of (2), and makes no mention of Cuttle, leaving the subject of (4) temporarily undecided. He enters (6) with a heavier and larger hand, writing fluently and underlining the whole entry.

Entry (6) anticipates the importance that memory will play in the development of Dombey. However, the content of those memories—their source in crucial scenes between father and daughter—lives so vividly in Dickens’s imagination that, though they are alluded to later, they are seldom planned or even recorded in the worksheets. On this occasion, already aware of the painfulness of the scene, he can only warn himself “not to make too much of it” (3).

Additional number plan: (8)→ch.19

Dickens enters (8) in preparation for ch.19. The young lovers-to-be make their secret relationship more acceptable, to themselves as well as others, by treating it as a close tie between brother and sister. He closes the number plan with a short slash below “Floy”.

MS

Composition and titling of ch.17 (later 18)

Dickens links to ch.16 by opening with the responses to the funeral of the household, office staff, street entertainers and children opposite. Afterwards comes the moment when Dombey miswords Paul’s memorial, the conversation of Chick and Tox, and the comfort they offer Florence—in all, nearly half the chapter, a long lead-in to the solitary Florence. She contemplates the rosy children and their father opposite (7), is distracted by Toots (5), comforted by Diogenes and, on the night prior to his departure, ventures to disturb her father in his study. Surprised, angered and deeply resentful, he lights her ascent on the stairs as before, aware of an earlier similar occasion, but “poisoning” the memory of it with jealous resentment. Dickens keeps the encounter brief, compressing the drama and paring down the exhortatory rhetoric. Revisions show him searching for an inclusive chapter title, but finally choosing to put the emphasis entirely on the closing scene (see ‘Appendix D’, ch.17, p.184).63

RH

Title and summary of ch.17 (later 18): (12), (13), (14), (15), (16) & (17)

Dickens copies in the final version of the title. Omitting the lead-in and writing at speed, he aligns the first entry with the title. He lists four phrases of similar length, structure and rhythm, his arm pulling to the right. They order four parts of the narrative focused on Florence (14–17). Then, noting the role of the household chorus, he inserts (13) almost avoiding the underlines above. Instead he smudges downwards the ‘ou’ of ‘house’, the ‘nd’ of ‘and’, and the ‘a’ of ‘father’, which confirms all five entries were made together, before the ink could dry (shown only in the facsimile; see above).

LH

Further number plan: (5)→ch.17 (later 18)

In his smallest hand, Dickens devises two letterings for illustrations of the chapter he has just completed. Eventually, the first is rejected in favour of the second. (The second plate’s subject, also involving Florence, is found later from ch.19; see ‘List of plates/illustrations’ (lviiilix)).

MS

Composition and titling of ch.18 (later 17)

The title is entered at the start of composition and not revised.

List: [6]

Dickens copies in the headings for chs.17 and 18 (as numbered before their reversal at proof stage) together with a chapter number heading for ch.19 mistakenly entered as ch.9. The omission of a title confirms that these entries are made prior to the composition and titling of ch.19.

MS

Composition and titling of ch.19

Dickens leaves an empty line for a title, a ‘gapping’ tactic used in composition for the first time, and often employed in subsequent chapters. He had devised the ploy in Ws.4 in titling the closing ch.13 (see p.53).

Beginning the chapter on MS p.21, he has sufficient space to preface Florence’s unexpected visit to the Shop with the details of Walter’s recent contact with Susan. The lovers struggle to convey their feelings. When Florence gives him the purse she made for Paul “with money in it”, Walter “would have left without speaking, for now he felt what parting was” (263284). Next morning, amidst the final farewells, he refuses Cuttle’s gift of the watch. Dickens ends on MS p.27 (a half page, like MS p.13 at the end of ch.17).

RH

Title and summary for ch.18 (later 17): (19) & (20)

Title and summary of ch.19: (22), (23), (24) & (25)

LH

Memo: (9)

Progressive corrosion—perhaps re-dipping at (22)—and similarities of hand, suggests the order of entry is as above (19)–(25) plus (9). He memos the gift of the watch (cf. ch.10), for use in later numbers, finishing with a flourish as the quill runs dry.

Proofs

As chs.17 and 18 in their different ways both recall ch.16, Dickens can open the number with either. He transposes them, perhaps to avoid two consecutive numbers involving Cuttle and/or to enclose a “painful” scene within lighter material. He expects ch.17 (now 18) to be 15 or 16 printed pages, but finds the proofs to be only 14. Later chapters add to the shortfall. After rushing to the London office from Paris, he makes five insertions in ch.19, the last two being the most significant: Florence’s conversation with Walter about her father’s dislike of him, as a motive for sending him away (262–63282–83), and the meeting with John Carker (264–65285–86), a farewell that anticipates a shift of emphasis in the latter’s function, from a parallel to Walter to a contrast with James.64

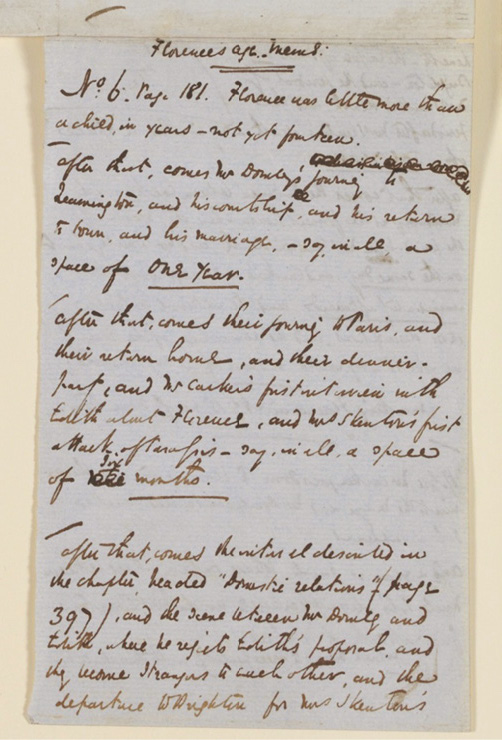

Facsimile of Ws.6a

(recto)

Image No.2012FE1494 recto (reduced): Forster Collection, National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum (2015). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Click here to view a 'zoomifiable' version.

(verso)

Image No.2012FE1494 verso (reduced): Forster Collection, National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum (2015). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Click here to view a 'zoomifiable' version.

Transcription of Ws.6a

(recto)

(verso)

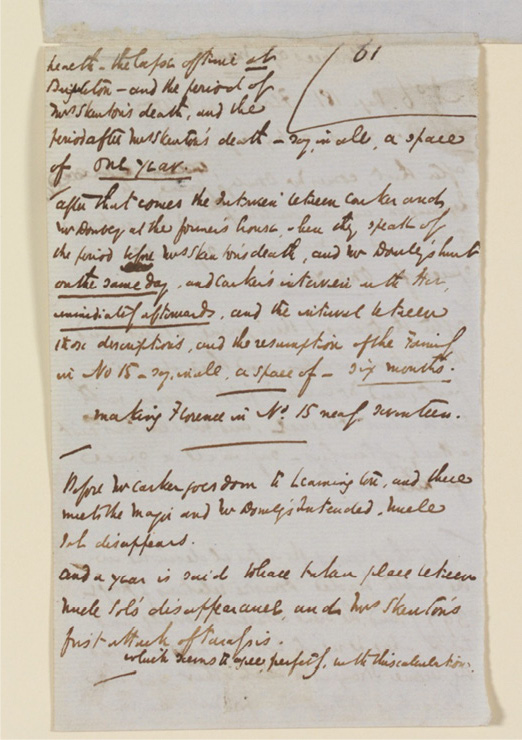

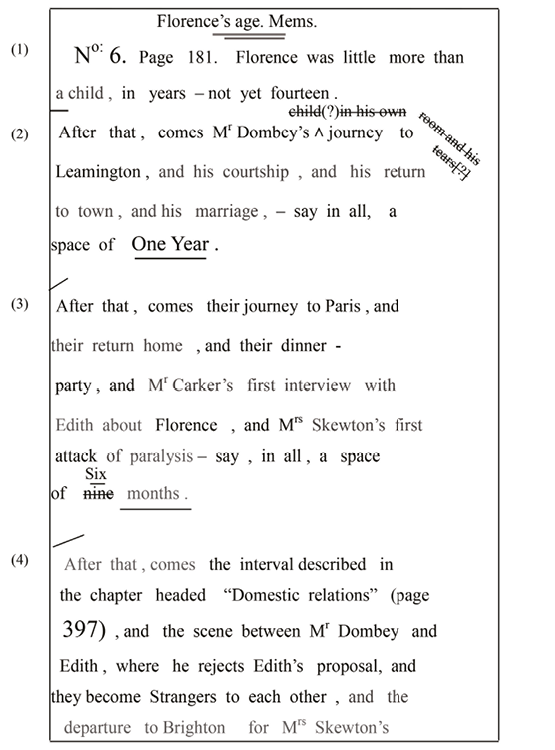

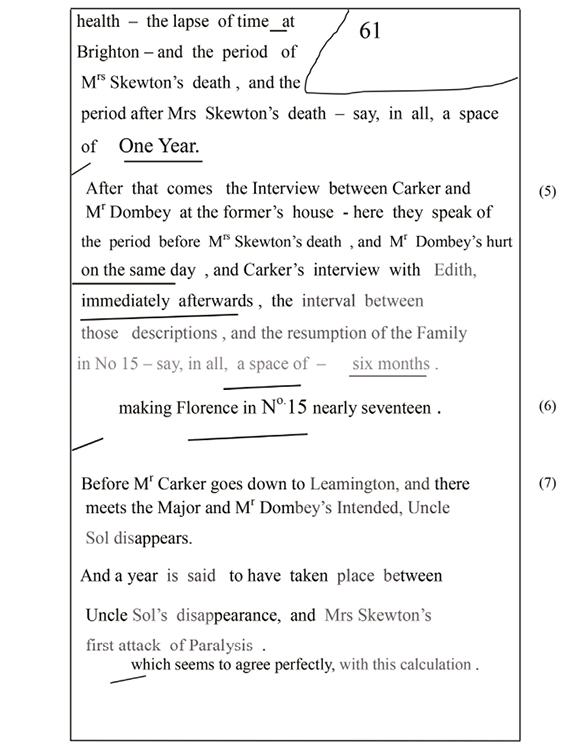

Commentary on Ws.6a (recto and verso)

The additional leaf entitled “Florence’s age. Mems” is attached to Ws.6, pasted by its top edge to the underside of Ws.6, probably because of its opening reference to that number (see the facsimile of Ws.6, p.62). However, the sheet written on both sides was always kept as a loose leaf by Dickens. Closely connected to the beginning of the narrative in No.15, it might be more appropriately attached to Ws.15. The quill and ink appear erratic in flow, perhaps due to a poor barrel and/or sullied ink. The density of the hand fluctuates irregularly throughout, the fluctuation becoming more frequent towards the end.

Aim and method

As the focus of the story changes from one group of characters to another, Dickens suspects that his management of time may lead to inconsistencies. His concern is with accuracy rather than likelihood. The purpose is to check that Florence could be almost seventeen years old at the start of No.15 (621686), that he can make her seventeen during ch.47 (624689), and that the year’s gap between Sol’s disappearance and Mrs Skewton’s first attack is generally consistent. His method is to collate the duration of the episodes as well as the interval between them, using the relevant worksheets and parts published so far.

[Editor’s note: references to the Clarendon text are by page alone, giving the page in the hardback, ed. Horsman 1974, then the page (superscripted) in the paperback, ed. Horsman 2008, superscripted (see ‘References (1)’, p.7)].

Entry (1)

Dickens begins with a moment in the aftermath to Paul’s death, when “Florence was little more than a child in years—not yet fourteen” giving her age as in the published text, rather than the manuscript, which differs in wording.65 He has reason to recall his starting point (1). It was a significant moment in the progress of Dombey’s relationship with Florence. During preparation for the scene, he had warned himself that it “may be too painful” (Ws.63), and at proofing moved the chapter from its opening position to the middle of the number. So, familiar with the occasion, he may scan the worksheets to find “the Scene with her father” (Ws.617) on the evening of the funeral. From there, going to his copy of No.6—perhaps delayed for a moment until he recalls that chs.17 and 18 were later transposed—he finds the relevant quotation on “p.181” (251270). Giving the printed page of the quotation as “p.181 No.6” establishes his reliance on the back number.

Entry (2)

He then calculates the gap between the departure for Leamington and the marriage. Considerations include, as a starting point, Floy’s visit to Dombey’s room, and afterwards his solitary tears of grief, triggered by the sight of her climbing the stairs alone (pp.182–83 of the part issue).66 Powerful for its compression of feeling, the scene adds nothing to the prosaic calculation of time passing, so the allusion is deleted. A glance at Ws.7 for the journey, Ws.9 for the courtship and Ws.10 for the wedding would confirm “One year” as a reasonable estimate of the first interval. The events referred to in (2) are prominent in Ws.7, 9 and 10.

Entry (3)

The second interval covers the return from Paris to Mrs Skewton’s first attack, to be found in No.12. The calculation depends partly on the untimed gap between the return from the three weeks in Paris and the “at home”. That occasion is soon followed by Mrs Skewton’s stroke, whose convalescence, Dickens hopes, can be made to concur with the first wedding anniversary. He stretches the next interval to nine months then later amends it to “Six months”.

Entry (4)

Dickens refers to ch.40 by chapter title and opening “p.397” in the part issue for No.13. The chapter “describes an interval” during which Dombey confronts Edith in her bedroom (he perhaps turns on to p.399). With the rejection of Edith’s proposal “they become Strangers to each other”, an echo of Edith’s last words “Nothing can makes us stranger to each other than we are” (p.404). From this moment, he resumes tracing the interval in the rest of the part. From the quarrel in the bedroom and the departure of Mrs Skewton, Florence, and Edith for Brighton to the time spent there and Mrs Skewton death and her “convenient” burial in Brighton (ch.41), he estimates the interval to be “One Year”.

In contrast to entries (1) and (2), many of the details he refers to in entries (3) and (4) are not mentioned in the worksheets. Instead, when he calculates the intervals from the return from Paris to Mrs Skewton’s death, he relies on two recent back numbers Nos.12 and 13.

Entry (5)

He recounts the events of the day that opens No.14, the instalment he has just completed: Dombey’s exchanges with Carker at his home, the mention of the time before Mrs Skewton’s death (when Carker witnessed Dombey’s first rebuke to Edith see p.569627), the accident and Carker’s interview with Edith—all on the same day. From these events to the dinner on the day preceding the second wedding anniversary, he estimates to be “six months”.

Entry (6)

Taking (1)-(5) together, an interval of about three years, he finds that it is possible for Florence to be “nearly seventeen” at the start of ch.48 (later 47).

Entry (7)

Finally he ties in the Sol/Cuttle subplot. He notes that Sol’s disappearance, discovered in the last chapter of No.8 (ch.25), is prior to Carker’s appearance in Leamington in the first chapter of No.9 (ch.26), and that the gap between Sol’s disappearance and Mrs Skewton’s first attack “is said” to be one year. There is no explicit statement defining the interval—Dickens uses “said” to mean ‘said by implication’.67

Dickens is now prepared, having checked the timeline in Ws.6a, to make its coherence more apparent to the reader. He is particularly concerned that the elopement should occur on the day of the second wedding anniversary, as an expression of Edith’s bitter hostility to Dombey (Ws.152). He continues ch.47 by recapitulating Florence’s experience up to the final quarrel. The new hope—to be loved by her father—is now after “nearly two years” quite gone. In its place, she clings to an idea of the father, dreaming of a man “to cherish and protect her”, a change in her consciousness, which “like the change from childhood to womanhood” occurs when she is “almost seventeen” (621686). She grows to be seventeen a few pages later (624689). Visitors to the house hardly notice her. When they do, they think her pretty, but withdrawn.

Dickens buries his calculations in his description of Florence’s apprehension:

None the less so [“delicate and thoughtful in appearance”], certainly, for her life of the last six months (after the accident), Florence took her seat at the dinner-table, on the day before the second anniversary of her father’s marriage to Edith (Mrs Skewton had been lying stricken with paralysis when the first came round), with an uneasiness, amounting to dread (625690-91).

The interpolated leaf Ws.6a shows that Dickens uses the worksheets to remind him of the content of more distant numbers and to help him retrieve detail in the pages of the part to which they refer. However, for the detail of the more recent numbers, including the number just published, as we might expect, he relies more on the parts themselves.

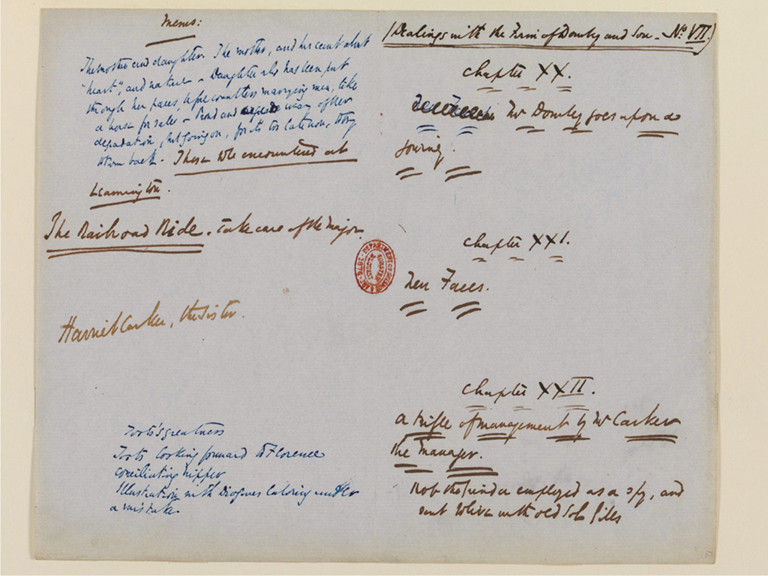

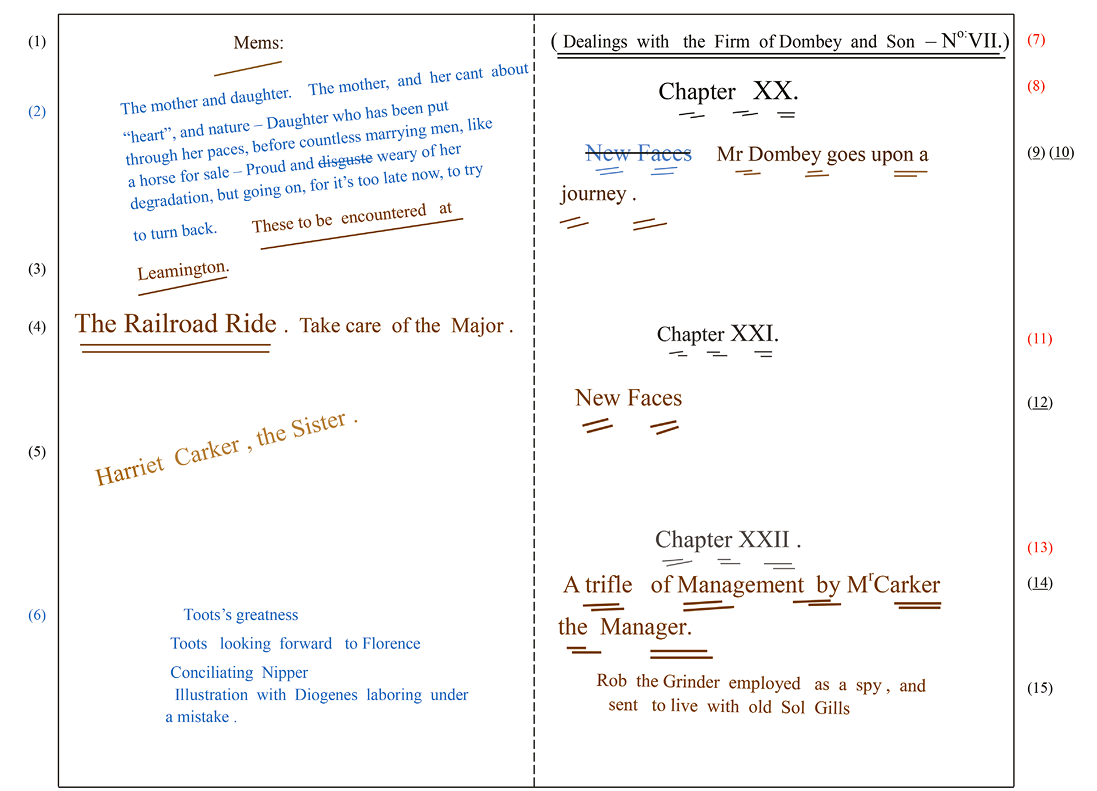

Worksheet for No.7

Image No.2012FE1498 (reduced): Forster Collection, National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum (2015). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Click here to view a 'zoomifiable' version.

Transcription of Ws.7

Commentary and order of entry (Ws.7)

Once back in Paris at the end of February, Dickens is overtaken by another crisis. Charley his eldest, contracting scarlet fever at his boarding school in the Strand, is quarantined and has to be nursed. He returns to make the arrangements and get accommodation for the family. For the first time, he begins a number well into the second week of the month, probably starting on 10 March—“the moment we got housed here, I fell into a dream of work, from which I only awoke last night”—and finishing on 23 March (L5:33 and 41). On this occasion near the office, he finishes his task close to the printer’s deadline. On 31 March No.7 for April 1847 is published.

Preliminary: (2)

This unique entry, the backstory of Edith, is quite unlike any other in its position on the page and in the fullness of its detail. Some of that detail will re-appear in the second half of ch.20 (later ch.21), some not until ch.27. Perhaps using the opportunity to test the quality of a new ink and quill, Dickens writes in the bright blue ink that he intends to use in the number’s composition. The order of entry proposed here minimises the ink changes and keeps consecutive all of the following: the other five blue entries in Ws.7, the corresponding chapters in the manuscript, and the relevant entries in the “List of Chapter Headings”. Further argument for a single entry in blue (Ws.72), with all remaining entries consecutive, runs as follows: (1) judging from the blue inks used later elsewhere, the available blue inks are variable in quality (2) Dickens uncertain of the ink’s quality may be testing it, before using blue of any sort in the manuscript for the first time (3) the bright blue seems to flow more smoothly and dry more quickly (4) having tested it, as the supply is probably uncertain, he restricts its use in the worksheet to those entries that he makes while composing chs.20 (later 20 and 21) and 22.68

RH

Preliminary headings: (7), (8), (11) & (13)

Dickens as usual makes the worksheet entries in black with some progressive loss of density.69

LH

Preliminary heading: (1)

Initial plan for the number: (3) & (4)→ch.20

Dickens now using black ink incorporates the mother and daughter back-story into his plan for the setting (3) and heavily stresses the importance of the railroad (4) with large lettering and double underlining, anticipating its recurrence as setting and symbol. He warns himself to attend to the key figure of the Mephistophelean Major, but perhaps not to overdo his bluster (4). The idea of a second marriage is hinted at in the cover design of the green wrapper by an altar scene involving a shadowy military figure, who becomes the “Old Major” of ch.7 (Ws.216 p.43). Dickens had already made preparations for No.7; during his struggles with No.6, he wrote to Forster “I think I shall manage Dombey’s second wife (introduced by the Major), and the beginning of that business in his present state of mind, very naturally and well” (endnote 62).

Titling and composition of ch.20 (later chs.20 and 21): (9)

Returning to the bright blue ink and quill, Dickens confident in his choice of title enters it in both manuscript and worksheet. On the same day that he starts the chapter, he writes a long letter to Browne about illustrating Dombey’s first meeting with Edith (see below p.136).

List: [6/7]

Still in blue he corrects the numbering of ch.19, adds its title, and copies to the “List of Chapter Headings” the number heading and the initial title of ch.20 (see p.176).

MS and Proofs

Composition and titling of ch.21 (later 22)

Corrections to the Proofs of ch.20

Dickens completes the fifteen MS pages of ch.20 on about 18 March, sends it to the printers and begins ch.21 (later 22).70 Receiving the proofs two or three days later, he is far enough into ch.21 (later 22) to know that it will become the closing chapter. On reading ch.20 in print, he divides the chapter, perhaps because it falls naturally into two parts but also because it seems too long (cf. Ws.128 p.91). Deleting the “New Faces”, he re-titles ch.20 “Mr Dombey goes upon a journey”; then, after “with the Major arm-in-arm”, he inserts the heading for a new ch.21 entitled “New Faces”. He can then return to MS p.16 to change ch.21 to ch.22 by adding a Roman ‘I’ to “XXI”.

In ch.22, Carker weaves his web, in some way touching each of the lives of John and Harriet, Sol and Walter, and Rob and Polly. After making one revision, Dickens finds an appropriately ironic title (see ‘Appendix D’, ch.22, p.185). With “the business of the day accomplished” Carker rides home, contemplating the daughter almost grown into a young woman (304330).

LH

Additional plan to extend the close of ch.22: (6)

Dickens may initially have intended to end with Carker’s reverie on horseback (as in chs.24 and 31). However, after following Carker through the day, he misjudges the approach to the ending. Raw from the mistake in No.6, he perhaps fears he is coming up short again. So breaking off from composition and having rehearsed in his mind’s eye a Toots episode, he notes its ‘salient points’ on the lower left side of the worksheet, still using the blue ink and quill. He then seizes on the episode as material for a contrasting second illustration.71

MS

Composition of an extension to ch.22

Dickens goes back in time to get a satisfactory lead-in to the climax (see “a few digressive words are necessary” (305330)). From then on, he transforms the passage into a sharply comic scene. Identifying with each character in turn—even with the dog—he paces the narrative to its close as planned.72

Titles for ch.20 & 21: (10), & (12)

Now using black ink, Dickens updates the worksheet entries in line with changes in proofs. Deleting the “New Faces”, he retitles ch.20 “Mr Dombey goes upon a journey” and uses its initial title for ch.21, in which Dombey meets the ‘new faces’ for the first time.

Title and summary note for ch.22: (14) & (15)

Dickens copies in the title (14) as revised in manuscript, adding the description, a plot device (15) that establishes a link between Sol’s shop and Carker.

LH

Memo: (5)→ch.22

In ch.22 the Carker brothers recount Harriet’s story (293–94317–18). This note of her mention is corroded, the ink probably thinning as the quill empties. It is another final entry—made after composing ch.22—serving as a reminder of the location of her backstory.

Proofs

Proofs show that, although the manuscript ends on p.26, the number is over, rather than under, written. In contrast, the manuscript of the previous number, which ended on p.27, was short by two pages of print. The discrepancy arises from differences in the amount of empty space and in the number of deletions in No.6 compared to No.7. Dickens makes three small cuts: two cuts to ch.20, one to ch.22 and increases the number of lines per page (Horsman 1974, p.270 n.1, p.278 n.4, and p.289 n.2).73

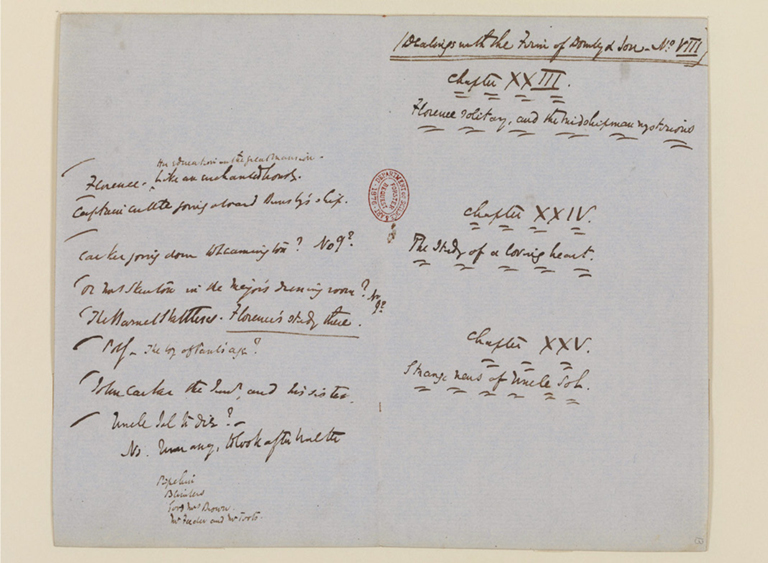

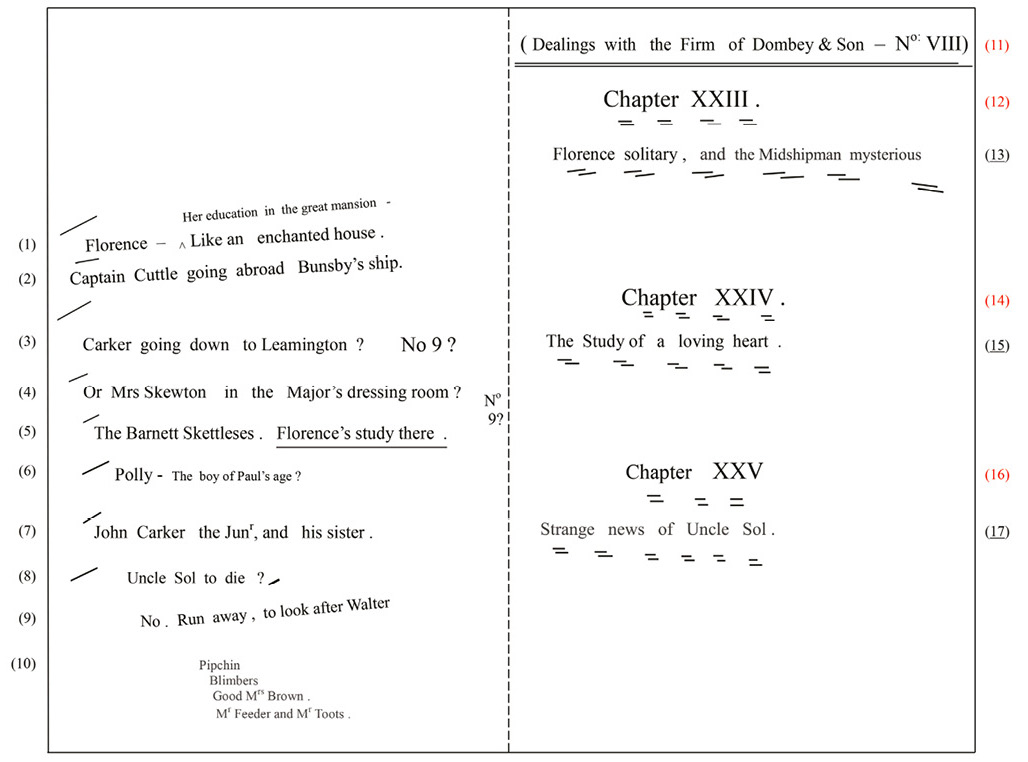

Worksheet for No.8

Image No.2012FE1499 (reduced): Forster Collection, National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum (2015). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Click here to view a 'zoomifiable' version.

Transcription of Ws.8

Commentary and order of entry (Ws.8)

Dickens writes to Forster on 10 April 1847, “I have been trying for three or four days, but really have only just begun” (L5:55). On 19 April, he was so shocked by the difficult birth of Sidney, his seventh child, that on the 20th “with half of the No [chs.24 & 25] yet to write – with my thoughts so shaken by yesterday” he was unable to “fall to work”. Nevertheless, he has “infinite relish for the story I am mining at” completing the second half by 26 April, when he has “just recovered from convulsions of Dombey after which I can never write legibly” (L5:59–60). Five days later on 30 April, No.8 for May 1847 is published.

LH

Plan for the number: (1) & (2)→ch.23; (3) & (4)→No.9, ch.26; (5)→ch.24; (6); (7)→No.11, ch.33; (8) & (9)→ch.25; (10)

Abandoning previous routines, Dickens omits all preliminaries. He writes without much regard to layout, in a fast hand that slopes unevenly, eliding the shapes of many letters, but with many stops and starts from (5) onwards.

He collects ideas for opening with Florence: the spellbound house as (in an inserted note) the setting of her education (1), then the move from pathos to comedy, much as he did in Ws.6, but this time by means of Cuttle, and then Bunsby (2).

He hesitates over the order and timing of the Leamington material (3) and (4), considering a visit to the Skettles (5)—as a way of extending the portrayal of Florence’s “study” of how to win her father’s love, by ‘studying’ the children of loving fathers that she finds there.

The two queries (3) and (4) precipitate the decision to postpone the courtship to No.9, and therefore the wedding to No.10. This has the obvious advantage of ending the novel’s second quarter with a climax. However, the decision to postpone leads to another problem, how to sustain a number devoted entirely to the isolated Florence.

Other notes are also set aside. The opportunity to fan Dombey’s resentment of the Toodles family—aired in ch.20 (273–75294–97)—by introducing a boy of Paul’s age (6) does not arise. The John/Harriet material of (7) would lose some of its point, if it preceded the development of James Carker. Sol’s death (8) might spoil the celebratory opening of his last bottle of Madeira, planned for the last chapter.

Dickens follows the suggestion of (8) with an emphatic hurried ‘No’ and then, after a small gap, adds that Sol should leave, unexpectedly (9), to search for Walter, and presumably return later. His departure opens the way for Cuttle to become caretaker of the Shop—an important first step in forming the small society that goes “over to the daughter” (see the last paragraph of the outline to Forster endnote 42).

Finally, using his “smallhand” for (10), Dickens lists persons for whom he has some particular intention, noted here as a reminder of their futures, but also as a part of his search for material for the current number:

“Pipchin”: to become the head of Dombey’s household staff (ch.40)

“Blimbers”: to be visited again (ch.41), but during the composition of ch.24 to be reintroduced as guests of the Skettles

“Good Mrs Brown”: to tell the fortunes of Edith and Carker, before the courtship begins (ch.27)

“Mr Feeder and Mr Toots”: now both young men, to meet again (ch.41).

MS

Composition of ch.23

Dickens leaves a blank line for the title and composes the chapter. He draws out Florence’s inner life through her reactions to the accelerated decay of the spellbound house and through her dreams of how to gain her father’s love. Her conversation with Susan about Walter leads to their search for news, and meetings with Rob—a ‘Son and Heir’, whose education has trained him for service as Carker’s spy—with Mrs MacStinger, Cuttle, Bunsby and Sol. Cuttle’s alarm at Sol’s strange behaviour prepares for the opening of the next number.

List: [7/8]

Titling of ch.23

Dickens sometimes updates his “List of Chapter Headings” as he begins writing the next number. When he updates the List on this occasion, he treats it as an opportunity to work on the title for ch.23, revising it, not in Ws or manuscript, but in the List (see ‘Appendix C’ [7/8] p.176). He transfers the final version to the gap left for it in the manuscript, and later to the worksheet (see below).

MS

Composition and titling of ch.24 and ch.25

The objective stated in Ws.62 “to throw the interest of Paul at once on Florence” still poses acute difficulties. In ch.23, Dickens relied on Florence’s reactions to “living alone in the great, dreary house” and her meetings with the company at the Wooden Midshipman. But in ch.24 during her visit to the Skettles, he has to import completely new material—with the inevitable appearance of contrivance—to draw out her state of mind in the continuing search for “the road to a hard parent’s heart”.

Dickens is “anxious not to anticipate in this No what I design for the next [No.9], and consequently must invent and plan for it [in No.8]” (L5:55). His planning successfully delays the courtship but his invention for once appears to fail him, contriving a series of poorly motivated encounters with conveniently long passages of stilted dialogue.

Although he postpones Carker material to No.9, he still has him very much in mind (3). He ends ch.24 with Carker’s offer of a message from Florence to her father (343–44373–74 and its illustration). In the next number, he reports other earlier encounters (ch.28: 383–84419–20).

LH

Outcomes: (3), (4), (6)

Dickens has already given in (9) his answer to (8). He leaves implicit his answer to the other three queries. In later worksheets, where he delays replying, he records outcomes more systematically, presumably to signal clearly what might (or must) be included later.

RH

Preliminaries and chapter titles: (11), (12), (13), (14), (15), (16) & (17)

The fall towards the end of each line, especially the curve of each title down the page (not shown) and the style of underlining used throughout suggest that all entries are made at the same time, in the order of their appearance on the page. It is likely that Dickens entered these headings hurriedly, for the sake of the record, after the number was written. The absence of chapter description arises, as in Ws.7, from the pressure of circumstances. It shows that, at this stage in the development of the worksheet, when he is pressed for time and in difficulty, he reins in planning or summarizing, and relies on chapter headings as a record of the instalment—with the exception in Ws.715, which plants Rob in the shop as Carker’s spy.

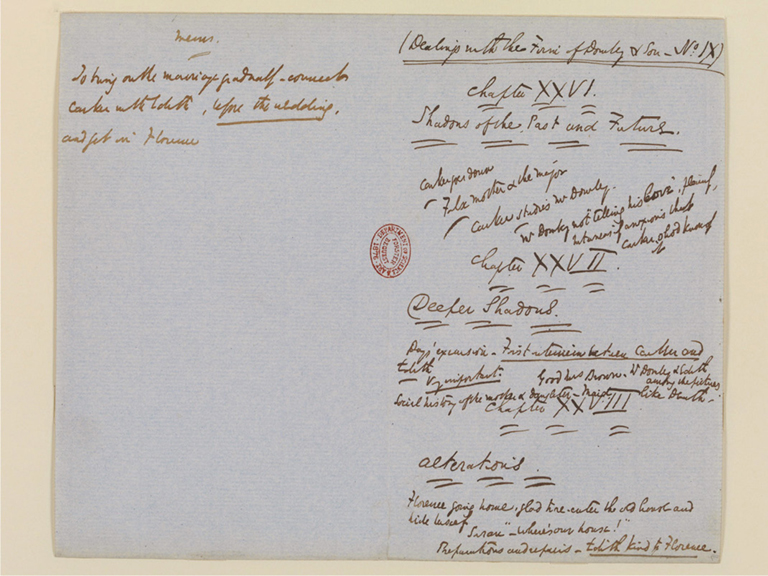

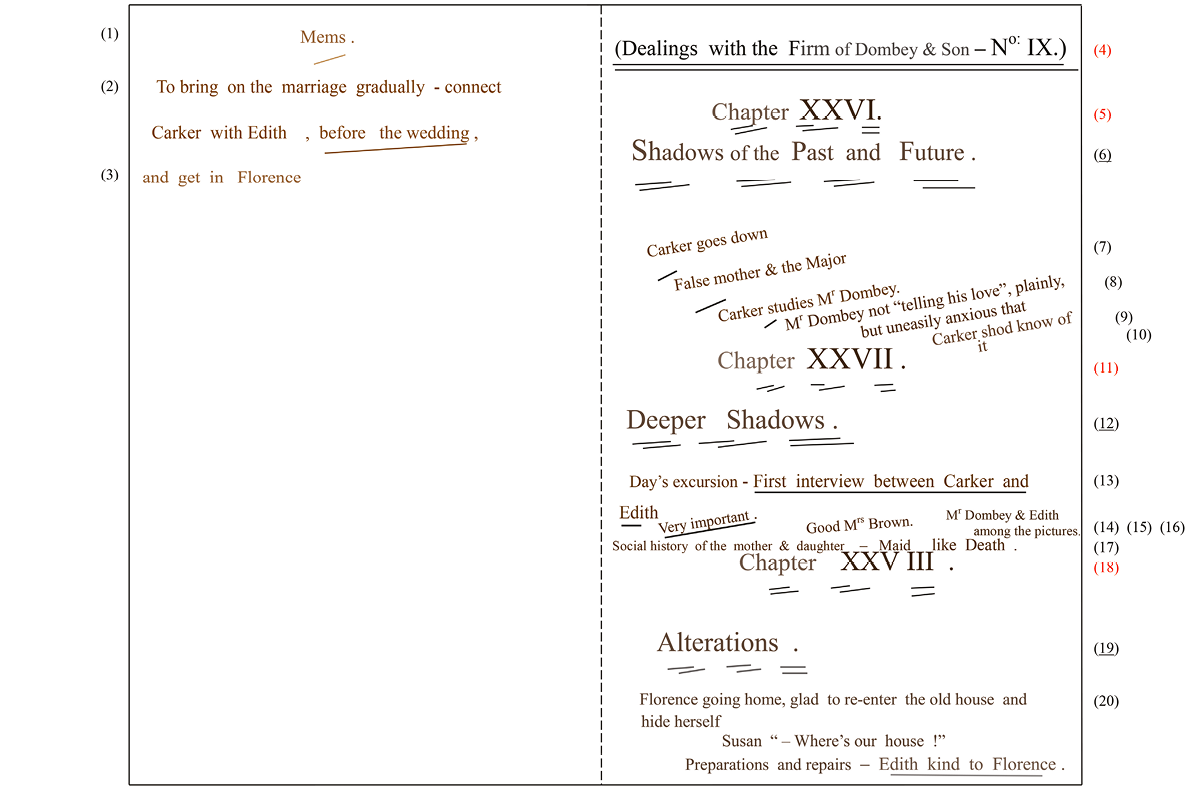

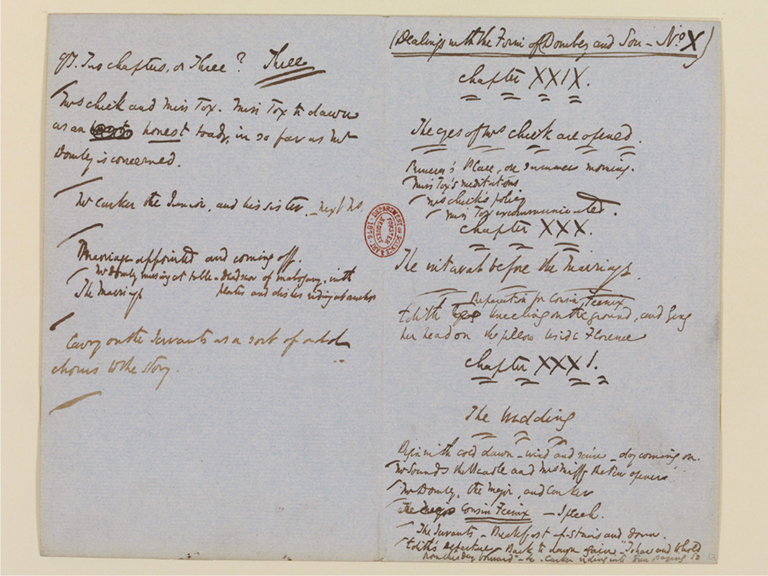

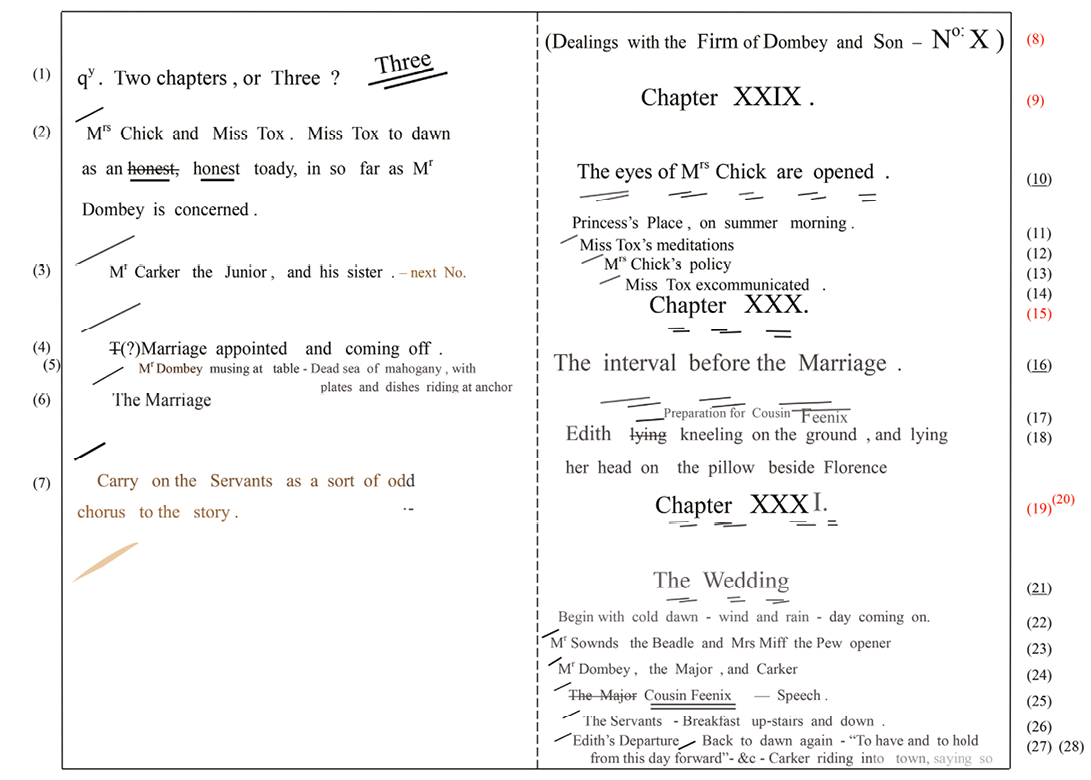

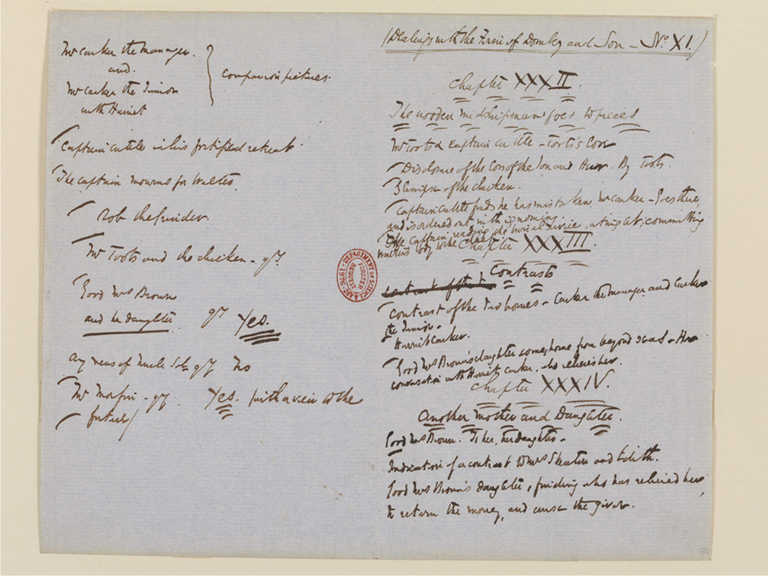

Worksheet for No.9

Image No.2012FE1491 (reduced): Forster Collection, National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum (2015). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Click here to view a 'zoomifiable' version.

Transcription of Ws.9

Commentary and order of entry (Ws.9)

Dickens’s misfortune continues. On 3 May, he is bitten by a horse “under the impression I had gone into his stall to steal his corn” (L5:65). It affects him badly “a low dull nervousness of a most distressing kind”, so much so that for two weeks he is unable to write without discomfort (L5:66). He writes only a few short letters before 16 May, making a very slow recovery from 10 May. He is still “very unwell when I left town [for Brighton 17 May], and had not the heart to go at my Number. I have gone since, however, and with such good will that the Number is very nearly gone too [23 May]” (L5:69). In Brighton “for a change” (L5:67), he produces the number in just seven or eight days, an extraordinary achievement (cf. his struggle to finish No.7, starting 10 March). After starting to write the opening ch.26 in black, he changes half way through to a bright blue ink. Presumably reserving his supply of bright blue for the manuscript (cf. his trial of the ink commented on in Ws.7, see ‘LH preliminary’ p.72), he changes back to black to plan both chs.27 and 28. Similar in hand, ink and quill, the plans for chs.27 and 28 seem to be prepared together. He then changes again to compose those chapters in bright blue (cf. the planning of ch.33 and 34 together in Ws.11, also followed later by a final chapter in bright blue). On 31 May, No.9 for June 1847 is published.

RH

Preliminary entries: (4), (5), (11) & (18)

In making these routine entries, Dickens appears to strain somewhat. He writes in a slightly larger hand, with less control than usual (see the wayward “ch” for the middle chapter, and the untypical ampersand in the novel’s title—only found here and in the hurried part heading of Ws.8).

LH

Plan for the number: (1); (2)→ch.27, (3)→ch.28

Sure of the number’s shape and content, Dickens gives himself three brief instructions. All three are concerned with events after the arrival of Carker. Progressive corrosion suggests that (2) is entered first, followed by (3) then (1). As in his preparation for the climax of the first quarter, the balance changes from number to chapter planning that is mainly concerned with the outcome of earlier plans.

RH

Plan for ch.26: (7), (8), (9) & (10)

Dickens leaves a gap for the title, entering four salient points in the usual black that cover the first half of the chapter: Carker has made the journey (7), the false Mrs Skewton and scheming Major conspire together (8), Carker closely watches Dombey’s reactions (9), and Dombey seeks to get Carker’s understanding without revealing himself (10). In composition the plan is reordered and Bagstock’s part is enlarged to include his assessment of Edith and his rivalry with Carker for influence over Dombey.

MS

Composition of first half of ch.26 in black ink

Leaving the chapter untitled, Dickens begins in the middle of the introductions. He follows the order of his plan, except for the meeting of Bagstock with Mrs Skewton, held back for the long central section of the chapter, during which he breaks off to write in blue.

Composition of second half of ch.26 and its titling

While writing the second half of the chapter, he inserts the most teasingly oblique title thus far (the blue of the title confirms its late entry). The action follows Bagstock to his meeting with the “False mother” in the longest episode of the chapter, which dramatizes the duplicity of Bagstock and Mrs Skewton, an old acquaintance (one of the “shadows of the past”). On his way back to the hotel, he reflects on Edith’s obvious reluctance (a “shadow of the future”). Dickens makes the competitiveness explicit between Bagstock and Carker, showing the latter to be the better game player. Making such a late start, as soon as the chapter is completed, Dickens probably sends it at once to the printers to give more time to set up and run off proofs.

Plan for ch.27: (13), (14), (15), (16) & (17)

Plan for ch.28: (20)

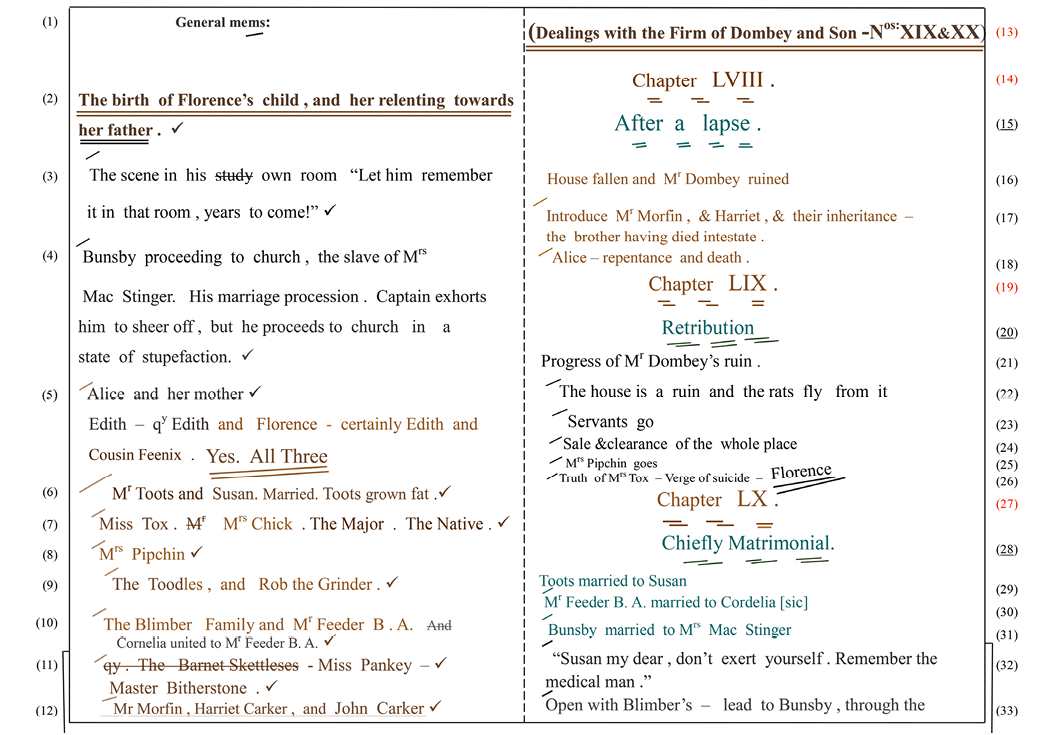

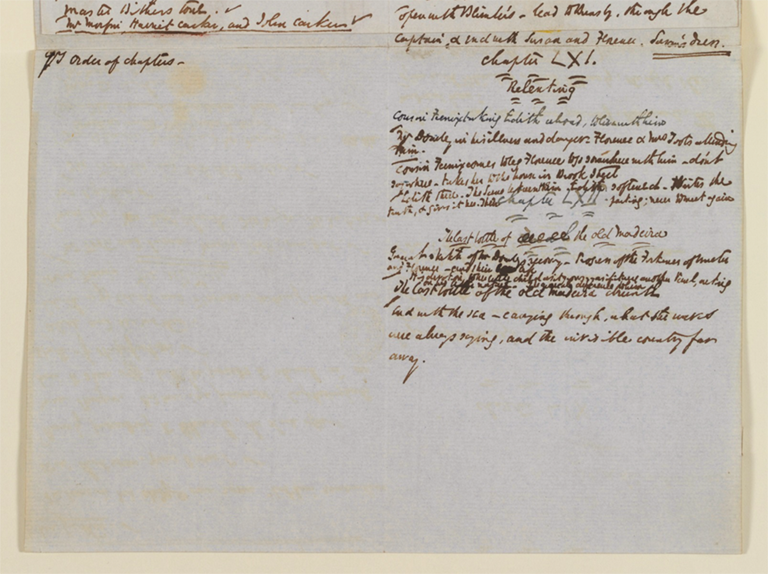

Both chapter plans are written in a similar hand with the same ink and quill. Both leave a similarly generous space for the chapter title, and, uneven in layout, have their final entry pressed up against a boundary (the next chapter number and page bottom respectively).