Afterword

© 2017 Tony Laing, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0092.09

I began work for this ebook by photographing the original working notes in the National Art Library within the V&A, while at the same time studying the printed transcriptions of the worksheets wherever I could find them, including Horsman’s edition of Dombey and Son. The original manuscript written with quill and ink on ordinary paper is still—a hundred and fifty years on—evocative of the occasion, which even facsimiles cannot fully convey. Horsman’s printed version, however—and others like it—quite without individuality, can seem uninteresting and lifeless.

The transcriptions in this edition attempt to convey many of the features of the original in a way that, while assisting in the interpretation of the facsimiles, may also intrigue the reader. The layout and appearance of the handwritten word has been converted to a printed equivalent in Word 2010, with the addition of all accompanying conventional and idiosyncratic lines. If the reader studies a facsimile of a worksheet alongside its transcription, some of what Stone calls the ‘immediacies’ of the original should still be detectable in both (Stone, p.xxxi).

With regard to context of the working notes given in Horsman and Stone, I have added a more detailed account of how the novel was published in ‘Section 1’, and in the commentaries of ‘Section 5’ an outline of Dickens’s other commitments and personal circumstances during the composition of each worksheet, gleaned from the labours of later researchers, particularly those responsible for the Pilgrim edition of the Letters. However, Dickens’s order of work—of which the worksheets are only a part—had to be independently reconstructed. It involved scrutiny of the hand, quill and ink of the worksheet, manuscript and List of chapter headings, then ordering in time the various sorts of entries in the worksheets and the related tasks in manuscript, List, and proofs (as described in Horsman 1974 ‘Introduction’, pp.xlv–vi).124

The reconstruction produces some unexpected results. For example, why does Dickens cover the left-hand side of Ws.5 with Ws.5a, instead of using the empty page beneath? And why is Ws.5a wafered into position after the composition of ch.14—as the right-hand edge of the added leaf suggests—when its entries clearly anticipate events described in that chapter? The likely solution is that Ws.5a has a special purpose. Dickens probably intended to use it as a separate sheet, keeping it alongside him as he composed ch.14. Then, adding a final entry (6) to the leaf, he may do the same again, as he composes ch.16.125 Thus, Ws.5a helps him pursue the innovation in fictional method noted in Ws.54; Paul’s experience of illness is to be “only expressed in the child’s own feelings – Not otherwise described”. The use of Ws.5a led me to look more closely at the point at which he added the other three attachments to their worksheets. Not that they might be used in the same way as Ws.5a (though Ws.4a may be), but that the timing of each attachment may be linked to a particular moment, which proves to be true of Ws.6a, and probably Ws.19&20a as well.

Another innovation occurs in the second quarter of the novel. Dickens experiments with a two-chapter number in No.10, making a note of the possibility at the start of Ws.10. The worksheet shows that he abandons the attempt early in the planning of the number, before he began composition. I detect a preparatory instance of that interest in No.7, which would have been a two-chapter number, had he not divided ch.20 at proof stage. He writes an unusually long chapter to open the number, and does the same in the closing chapter, after hastily planning an extension during its composition (and incidentally preserving unbroken the use of his bright blue ink).

Ordering entries and their associated tasks creates another significant recurrent dilemma. You cannot position on a timeline the ‘chapter descriptions’ (the entries immediately below the chapter title) without deciding whether those entries are made before composition and are plans, or are made after it and are summaries. Sorting out how to make that decision takes up most of ‘Chapter descriptions as plans’ in ‘Section 6’, p.137. One outcome is that, contrary to received opinion, there are many more chapter plans in the worksheets (for Dombey and Son at least) than chapter summaries. Establishing that many chapter descriptions are plans gives us fresh insight into Dickens’s working methods, particularly his sensitivity to the approaching end of chapter and number.

When Dickens prepares for the final double number, he isolates himself from his London life for the best part of three weeks by moving to lodgings in Brighton. Tracing the course of his work, while he was living there, reveals the close attention he gives to the double number. The various indications of planning found there confirm the validity of the evidence used to distinguish plans from summaries in the single-number worksheets.

The timing of the change to the less satisfactory poorer blue inks—the watery blue and the greeny blue—also has a surprising outcome. Both of the changes to those blue inks coincide with a move by Dickens to a temporary residence, where he is soon obliged to use whatever ink is available. He has just returned temporarily to Devonshire Terrace (after his tenant vacated it) in No.12 and is in Brighton (in different lodgings from his previous visit) for the double number Nos.19&20. The concurrence of ink change with a temporary move strengthens the assumption that all uses of blue are—with two significant exceptions— consecutive and unbroken.

I summarise these investigations because they may be of interest to other researchers. They flow from the reconstruction of what is often a complicated sequence of events—the ordering in time of all aspects of Dickens’s work in what he calls his “monthly harness” (L5:221) or “my month’s dream” (L5:44). A full account of the order of entry, to do justice to the complexity of what he was attempting, requires a succinct way of identifying each entry. To meet that requirement, I add marginal numbers to all transcriptions, aware that they might slow reading, but hoping that they would ultimately make it easier to test evidence or follow an argument.

Dickens devises the worksheets to help him unify the novel by giving it shape, interweaving its many threads and drawing together its characters. The attempt brings with it “prodigious” and “infinite” pains. Approaching a climax, he complains “it takes so much time, and requires to be so carefully done” (L5:165). At the finish, he writes, “All through I have bestowed all the pains and time at my command upon it” (L5:271). Looking back, he believes “if any of my books are read years hence, Dombey will be remembered as among the best of them” (L5:611). The worksheets, with their ordered commentaries, give us the means whereby we can retrace some of his struggles.

I hope that the pursuit of the above outcomes will not deflect readers with an interest in how Dickens wrote Dombey and Son. The first four Sections, much of the commentaries, and of course all the facsimiles and transcriptions are intended for all readers, whether they are adapting the novel to other media, teachers and students in colleges and universities, members of reading groups, researchers in the field or Dickens enthusiasts. For the sake of readers, wherever they are, I have included references to easily accessible and inexpensive sources, as well as to the standard scholarly texts. Quotations from Dickens’s letters to Forster are referred to using an online edition of Forster’s Life, ebook 25851 in Project Gutenberg, downloaded to the free Kindle app, rather than the richly annotated Pilgrim Letters. Quotations from Dombey and Son are to both the hardback and paperback version of the Clarendon text; for more on ‘References’, see p.7. Most deletions made to the novel’s text are restored in ebook 821 of Project Gutenberg. I have also included in the endnotes passages from all these sources.

Although Dickens’s entries in the worksheet on Hablot Browne’s illustrations are noted in the commentaries, there is unfortunately insufficient space in my chosen format to describe their detail, or to relate them to his changing responses to Browne’s work.126 The evidence for the contact between author and illustrator is considerable in the first half of the novel—for example in the letter to Browne quoted in connection with Dickens’s vision of the first meeting of Dombey and Edith (see above p.136)—but, during the second half of the novel, there are few letters to Browne, and few entries in the worksheets concerning illustration. Their absence suggests perhaps either his resignation to Hablot Browne’s shortcomings or some relaxation in his narrow conception of the role of the illustrator. A full account of the way the illustrations illuminate the text by visual allusion is given by Andrew Sanders in Appendix 2 of the Penguin Classics edition of Dombey and Son (London: Penguin Books, 2002), pp.950–57. There is also a substantial summary of ‘Scholarship concerning illustration’ in Leon Litvack’s Charles Dickens’s “Dombey and Son”: An Annotated Bibliography (New York: AMS Press, 1999) pp.23–56.

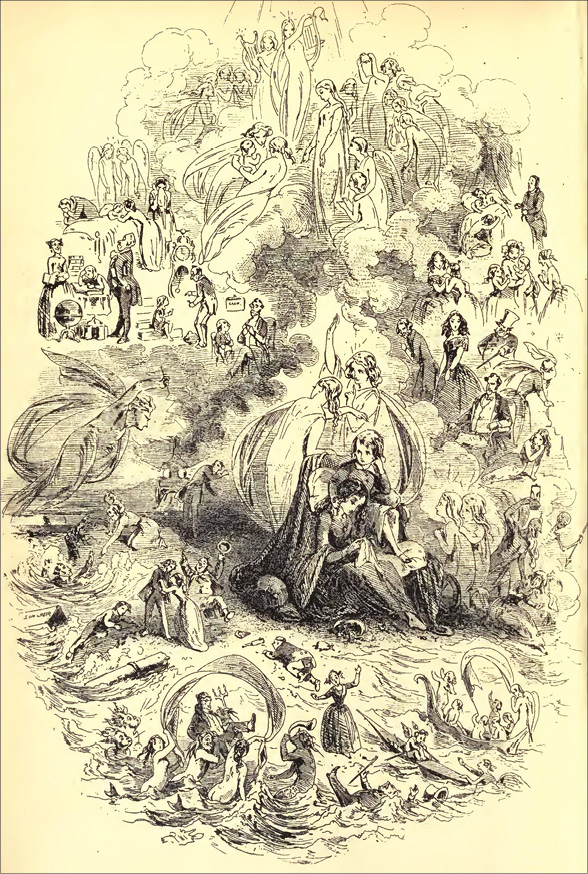

To close this edition of the working notes, by way of a final comment on the relation of notes and text to illustration, it seems appropriate to end with an image of the novel’s frontispiece, the last plate that Browne made for the novel. We know from Dickens’s letter to his publishers that “Browne has come down here [Brighton] today [12 March 1848] with his frontispiece”. The illustrator made a special journey from Croydon to show Dickens his sketch for the plate (L5:261). Presumably, it had the author’s consent, and perhaps his approval. (There are signs in worksheets and letters that Dickens eventually stands back to allow his illustrator to form his own vision of the text (cf. endnote 53)).

In contrast to the cover design of the green wrapper, Browne’s second rendering of the story is shaped, not by the fortunes of the Firm and the passage of time, but by an allegorical and symbolic re-interpretation of the text, focusing on Florence. With Paul, she forms a triangle, deeply cut in the foreground of the design. From there, the picture is divided into segments. In the upper right-hand segment are three episodes from the story of Florence, beginning with the death of her mother after the Paul’s birth; followed below by a group—including an older Florence—delineated by their attitude towards the seated figure of an implacable unseeing Dombey; in the upper left-hand segment are four episodes from the story of little Paul, ending with his death; and between and above them, cut with the very lightest line, is a host of youthful angelic spirits, typified by their free-flowing robes, two of whom carry Paul upwards towards a mother figure, who welcomes him with open arms. On each side of the central triangle are emblematic images of Carker’s violent death and of the death of the terrified Mrs Skewton, linked by the rise and fall of the steam train’s smoke. Beneath the triangle, in a half-circle, is a fanciful depiction of figures in action: Walter struggling to survive the wreck of his ship, the lovers now reconciled, the radiant Cuttle celebrating the occasion, Florence preventing her father’s suicide (imaged as a rescue from the sea, and encouraged by Paul), Old Sol mischievously carried on the waves by mermaids, and finally the figures of Rob and Miss Tox in a line from sextant and telescope to the sea, where Major Bagstock, helpless in the waters, is about to lose to his stick.

Browne, probably assisted by friend and co-worker Robert Young, among others, etches two copies of the sketch—after it had been reversed—on to the specially prepared steel. They organise the composition by using a full range of graded tones, a reflection of the eighteen days they had for the work, in contrast to the usual ten.127 Browne manages to include a great deal of detail, which readers can recognise with the same pleasure they may have had in matching visual and textual detail in the earlier plates.128

However, even with its tonal variation, Browne’s medium allows him only one reading of the novel. His design emphasises, in composition and detail, the role played by Florence (cf. Butt and Tillotson, p.95). Dickens, judging by his “immediate outline” might object to the omission of much of “the stock of the soup”, especially the scenes that show the progress of the relation of Dombey and Florence (see endnote 42). He might also dislike Browne’s repositioning of baby Paul and Florence to express their shared dependence on the mother—an example of an illustrator’s interpretive freedom, which on occasion irritated Dickens considerably, if it clashed with his text or with his conception of the scene (see 2nd paragraph of ‘Proofs’ p.109).

Browne follows Carker’s recollection of Florence as a little child “dark eyes and hair [and] a very good face” and his expectation that “I dare say she’s pretty” (304330).129 He depicts her with luxuriant hair let down, bonnet cast aside, shawl falling around her, long legs crossed, and a naked foot on the sand, while Paul lovingly rests a hand on her hair and shoulder. By such detail, Browne claims his own version of Florence. She is still the same loving young sister that we know from the text, who enjoys the needy affection of her little brother. She is also still the young girl, attending to her needlework, perhaps in the hope of pleasing her father. But for Browne, in his summary picture of her, at the heart of the novel, she is above all free from constraint and physically at ease with herself.

Frontispiece to Dombey and Son by Charles Dickens with illustrations by H. K. Browne (1848).