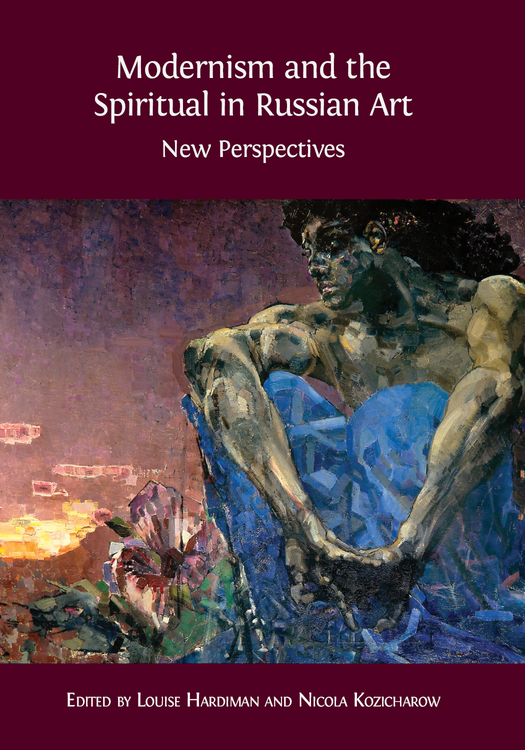

1. Introduction: Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art

© 2017 Louise Hardiman and Nicola Kozicharow, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0115.01

It also belongs to my definition of Modernism […] that art, that aesthetic experience no longer needs to be justified in other terms than its own, that art is an end in itself and that the aesthetic is an autonomous value. It could now be acknowledged that art doesn’t have to teach, doesn’t have to celebrate or glorify anybody or anything, doesn’t have to advance causes; that it has become free to distance itself from religion, politics, and even morality. All it has to do is be good as art.

Clement Greenberg1

In his 1961 text ‘Modernist Painting’ and other writings since, renowned art critic Clement Greenberg contended that the significance of modernist painting lay precisely in its aesthetic qualities. The autonomy granted to an artwork rendered factors outside of its formal aspects, such as artistic intention, tangential to its meaning or value. Art was now free from religious, political, or moral content and ideas, however strongly intended or present. Greenberg’s theory of formalist modernism has been criticised at length since the 1960s, yet scholars still find it necessary to refute it, especially in discussions of the importance of spirituality or religion in the history of modern art, showing its lasting power.2 For Russian modernism, however, Greenberg’s theories have little relevance. It is this book’s contention that, in Russia, extrinsic ideas and influences — and, most of all, those of Russian religious and spiritual traditions — were of the utmost importance in the making, content, and meaning of modern art. The claim is not entirely new; for example, scholarship in recent years has engaged with such highly pertinent questions as how icon painting became an inspiration for the Russian avant-garde.3 Highlighting fresh research from an international set of scholars, this volume introduces new interpretations and approaches, and aims to energise debate on issues which have been circulating in scholarship on modern art over the past century. Ten chapters from emerging and established historians illustrate the diverse ways in which themes of religion and spirituality were central to the work of artists and critics during the rise of Russian modernism.

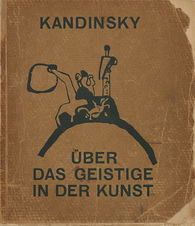

The relationship between modernism and the spiritual has been, and continues to be, a subject of debate in art historical scholarship in the west. Vasily Kandinsky, whose seminal treatise, On the Spiritual in Art (Über das Geistige in der Kunst), of 1911–12 (fig. 1.1) has been hailed as one of the most important texts in the history of modern art, is a key figure in such discussions.4 Kandinsky’s theories, based upon spiritual notions outside of Russian Orthodoxy, are now interpreted as owing much to Theosophy;5 indeed, the influence of spiritual traditions beyond mainstream religion has informed much scholarship to date on the nexus between modernism and spirituality. Appearing soon after Greenberg set out his definition of modernism, Sixten Ringbom’s publications on Kandinsky pioneered the discussion of the spiritual in theories of modern art.6 In the past fifty years more research has emerged, often in connection with the multitude of exhibitions on the theme of ‘the spiritual in modern art’ that took place in the late 1970s and 1980s.7

1.1 Vasily Kandinsky, cover of Über das Geistige in der Kunst (On the Spiritual in Art), 1911 (dated 1912).8

Displays such as Perceptions of the Spirit in Twentieth-Century American Art (Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1977) and The Spiritual in Modern Art: Abstract Painting, 1890–1985 (Los Angeles County Museum of Modern Art, 1986) did much to change the terms of debate (indeed, the latter was described by James Elkins as “watershed work”).9 The momentum continues. To take a more recent example, the relationship between Russian art and religious culture was examined in the exhibition Jesus Christ in Christian Art and Culture of the Fourteenth to Twentieth Centuries (Iisus Khristos v khristianskom iskusstve i kul′ture XIV–XX veka) in 2000 to 2001 at the State Russian Museum in St Petersburg.10 At the time of publication there has been an upsurge in books, conferences, and academic networks focused upon the relationship between modernism and spirituality and/or religion, making this volume’s publication especially timely.11

With these developments in mind, one of the principal aims of this book is to broaden the debate on Russian artists and the spiritual beyond Kandinsky. Instead, the discussion expands to highlight other modern artists, critics, and mediating figures. Our intention is to open research in new directions; this is not, and does not claim to be, a comprehensive survey. The plurality of religious and spiritual traditions with active followers in Russia during the timeframe under consideration, and the resulting effects upon art, cannot meaningfully be reflected by a group of disparate authors without forfeiting analytical depth and the detail of their research. For example, none of the chapters deals with Judaism, which naturally falls into the frame in any discussion of avant-garde artists such as Marc Chagall, Nathan Altman, and others. Esoteric spirituality here is reflected only by Theosophy, but encompasses a far broader set of belief practices that influenced modernist art during this period — the story of Shamanism and Kandinsky is a notable example.12 Although this volume highlights the richness of the spiritual theme, it should be remembered that this did not necessarily have an impact upon the work of every Russian artist of the late nineteenth to mid-twentieth century; rather, this phenomenon represented a pervasive theme within Russian modernism.

Throughout this publication, ‘spiritual’ is used as an umbrella term to encompass a broad range of religious sources and art that engaged — and, at times, entranced — critics and artists in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Credit is given to the variety of influences, including Russian religious art — primarily icons and frescoes, which, in the late nineteenth century, were appreciated for the first time as artistic, rather than religious, objects — and spiritual concepts such as Theosophy, ideas of the Russian ‘soul’, and the translation of mystical concepts. Religion — that “noncultic, major system of belief” and all its often public and communal trappings (hymns, catechisms, liturgies, rituals, etc.) — is thus united with spirituality — the “private, subjective, often wordless”.13

Scholarship in Russia and the west has explored some of the overarching themes of this book with reference to a variety of figures, mostly artists themselves, over a wide chronology. The narrative spans from Aleksandr Ivanov’s exploration of religious ideas in his paintings of the first half of the nineteenth century, to the Soviet nonconformist artists of the 1960s, and ultimately to other artistic media, for example, Andrei Tarkovsky’s films of the latter half of the twentieth century.14 However, this book concentrates on the critical years of modernism in Russia from its early stages in the late nineteenth century, when artists began to challenge the traditional boundaries of painting, sculpture, and architecture by consciously adopting more radical techniques, media, or themes, until the Thaw period, by which time socialist realism had become thoroughly entrenched as the official art of the Soviet Union. The diverse array of spiritual influences during this period fuelled new formal and theoretical investigations in art, incited fierce debates among artists and critics as to how such concerns were to be deployed, and drew interest from followers and enthusiasts in the west. The notion of the spiritual, broadly defined — whether drawn from conventional religious art or from esoteric ideas — helped shape modernism in Russian art and underpinned some of its most radical experiments. This was especially the case with Russia’s pioneering exponents of non-objective painting — Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, Natalia Goncharova, and Mikhail Larionov — who now appear at the heart of the standard art historical narrative of early abstraction.15 This volume offers new readings of a history only partially explored, delving into less familiar stories, and challenging long-held assumptions.

Between East and West: Religion in Russian Art

Thanks to Kandinsky, Russian art has frequently appeared at the heart of discussions of western modernism and spirituality, with a chronology that begins in the 1910s.16 However, in scholarship concentrating on Russian art, the link between art and the spiritual tradition has been a more constant thread. This has much to do with the exceptionally close relationship between art and religion over centuries in Russia’s history, and the particular dynamics of art production in the Church/state relationship, after Grand Prince Vladimir I of Kyiv adopted Orthodoxy from Byzantium as the state religion in AD 988. At the other end of the timeline, the era of emerging modernism was concomitant with a period in the late nineteenth century when various historical developments prompted a deeper, renewed interest in religion and spirituality among artistic communities.17

Until the late seventeenth century, artistic production in Russia was largely dedicated to the service of the Russian Orthodox Church and the ceremonial and personal needs of the Tsars. The visual arts were dominated by the Byzantine tradition of icon painting brought over from Constantinople; the only notable exception was the tradition of folk art that dated from ancient times and continued to develop in parallel with other arts. However, the era of Peter the Great (reigned 1682–1721) saw radical cultural changes as a result of his decision to secularise the arts and implement western modes of representation. This new, secular tradition continued under the auspices of the Imperial Academy of Arts, founded in 1757 in St Petersburg by Empress Elizabeth (reigned 1741–62), and reshaped and energised by Catherine the Great (reigned 1762–96). As in Europe, Russian academic history painting — officially the most elevated genre — encouraged the painting of religious scenes, as well as those from history and classical myth. Among others, the history painter Anton Losenko painted scenes from the Bible such as his vibrant depiction of the apostles hauling up Christ’s miraculous net full of fish (The Miraculous Catch, 1762, State Russian Museum, St Petersburg). Here, however, the religious narrative was used to showcase the artist’s prowess at emulating the best of European artistic practice (for example, Rubens and Raphael had both executed canvases on the same subject), rather than engaging with the spiritual dimensions of the content.

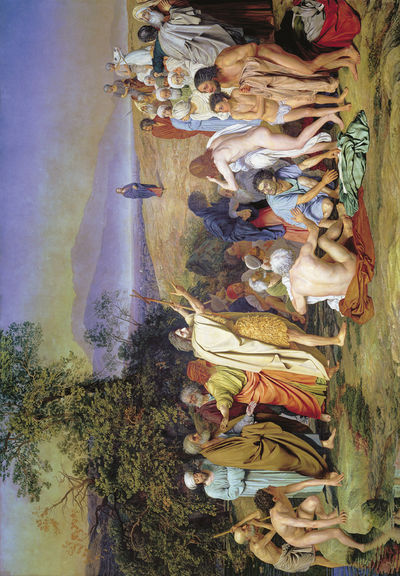

1.2 Aleksandr Ivanov, The Appearance of Christ to the People, 1837–57. Oil on canvas, 540 x 750 cm. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Photograph in the public domain. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Alexander_Andrejewitsch_Iwanow_-_The_Appearance_of_Christ_before_the_People.jpg

The shift toward a more deeply felt engagement with spiritual themes has been credited to Aleksandr Ivanov, whose magnum opus, The Appearance of Christ to the People (1837–57, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow) can be seen as a more fully formed expression of an interest in religious painting emerging earlier in the century (fig. 1.2). For Rosalind Blakesley, Ivanov’s precursor, Fedor Bruni, “was the grit in the oyster in pushing Russian history painting in spiritual directions”, but Ivanov “cast the pearl”.18 Contemporaries praised Bruni’s The Brazen Serpent (1834–31, State Russian Museum) for the “profoundly religious thought that gave soul to the painting”.19 This “soul”, wrote one commentator, set Russian painting apart from that of European artists, for, if a Frenchman had painted this work, “nothing would have engaged our soul and overcome the harsh reality of this world”.20 Thus by the 1830s Russia’s artistic identity had, at least for some observers, developed a distinctive spiritual character.

Ivanov’s The Appearance of Christ heralded the next phase of Russian religious painting — that of realism.21 When the painting was finally revealed to the public in 1858, Bruni called the figures’ nakedness “unchristian”, and one in particular, he wrote, had a head like “a deformed, half-decayed corpse”.22 These realistic portrayals offered a fresh approach to how spiritual themes might be conveyed in paint. As Ivanov wrote to the radical thinker Nikolai Chernyshevsky, he sought to “combine the technique of Raphael with the ideas of modern civilisation — that is the role of art in the present time”.23 To make Christ’s message relevant for contemporary viewers, Ivanov chose to focus on the moment of its reception rather than the figure of Christ himself; the reactions of the slave and other onlookers thus became the main subjects, and Christ was relegated to the background. This was an inversion of the traditional hierarchy of religious figures, for Ivanov had produced a painting in the academic manner, yet with an unprecedented authenticity. To prepare, he had visited synagogues, read accounts of the Holy Land, sketched en plein air, and, like the pre-Raphaelite artist William Holman Hunt in England, he attempted to travel to Palestine. Text, too, was crucial: Ivanov knew the Bible by heart and, after reading David Friedrich Strauss’s Life of Jesus (1835–36), which underlined the significance of Christ as a living person, he travelled to Germany to meet the author. Such actions place Ivanov as an early experimenter on the path towards modernism, in that they signal the artistic freedom and individuality that would characterise modernist painting, the turn away from the studio to lived experience, and, crucially in this context, the idea of the spiritual quest — a notion that would become more important as the century progressed. Ivanov’s explorations of art and spirituality brought him into contact with the Nazarenes, a group of German Romantic painters formed in 1809. These artists had a significant influence on him, sharing his interest in the fourteenth- and fifteenth-century devotional art of Giotto and Fra Angelico, and, indeed, in the nature of devotion itself.24 However, The Appearance of Christ did not have the religious impact Ivanov had hoped. Rather it was Ivanov’s proto-realist approach that remained his lasting legacy. Yet the part played by broader notions of the spiritual in the creative process did not end with Ivanov. Indeed, parallels can be drawn between his use of textual and artistic sources, his interest in spiritual ideas, and the role of his own religious faith and those of artists in subsequent decades, in ways that are well illustrated by this volume. Moreover, as Pamela Davidson has argued, Ivanov can be seen as inaugurating a more fully developed tradition in the visual arts of ‘artist as prophet’, foreshadowing Kandinsky and other spiritually oriented artists and thinkers of the Silver Age.25

In the politically charged climate of the 1860s and 1870s, the state of Russian society and its ills became a rich source of debate in intellectual circles, and the hallmarks of a critical realist art movement emerged when a number of artists broke away from Academic painting and began to approach religious themes in unusually bold ways. Corruption in the Orthodox Church had incited public debate since the 1840s, but it was not until this moment that artists would openly criticise the church in paint, provoking hostile reactions.26 When Vasily Perov exhibited his work The Village Religious Procession at Easter (1861, Tretyakov Gallery) at the Society for the Encouragement of the Arts, the Holy Synod ordered that it be removed from display, owing to its brazen depiction of drunken clergy. The Society acquiesced, and the censor banned its reproduction in print form until 1905.

This censorship did not deter realist artists who tackled biblical scenes in their work. The most notable of these, Nikolai Ge and Ivan Kramskoi, were founder members of the dominant exhibiting society of the late nineteenth century, the ‘Association of Travelling Art Exhibitions’ (Tovarishchestvo peredvizhnykh khudozhestvennykh vystavok, 1870–1923) known as the ‘Peredvizhniki’. Both artists’ depictions of Christ were fiercely debated. Their approaches had in common with Ivanov’s that they sought to portray Christ as a living man and opposing force against the troubled state of society. This was especially true of Ge, whose strong faith prompted him to declare a wish to incite religious ire among his spectators: “I will shake their minds with Christ’s agony. I want them, not to sigh gently, but to howl to the heavens!”27 Enamoured with the religious writings of Leo Tolstoy, he began corresponding with the writer. Tolstoy had broken away from Orthodoxy to found his own belief system, one so controversial that by 1901 he would be excommunicated. Tolstoy saw Ge’s work as representing “the living Christ”, but others reacted with vitriol.28 For Fyodor Dostoevsky, Ge’s Last Supper (1863, State Russian Museum) presented “not the Christ we know […] there is no historical truth here […] everything here is false”.29 Furthermore, in 1890, Ge’s What is Truth? (Tretyakov Gallery) — a bold image of Christ and Pontius Pilate — was exhibited at the Peredvizhnik exhibition in St Petersburg, only to be removed and banned from further display.30 This direct involvement of the state and the Holy Synod in censoring works of a religious nature continued well into the early twentieth century, affecting the work of Natalia Goncharova and Symbolist artists of the ‘Blue Rose’ group, among others. Disapproval might be directed at the choice of imagery or, more broadly, the spiritual ideas which underpinned the work. Indeed Ge, whose work often fell outside the Orthodox and academic canons, can be seen as a precursor of those modernist artists whose unconventional spirituality led them to a new artistic approach, but one that was destined for a difficult reception.

Paths to Modernism: Realism and Nationalism

The rise of realism coincided with an upsurge in nationalist sentiment from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, and realist painters were championed by influential writers such as Vladimir Stasov, who regarded them as the embodiment of a ‘national school’ for their interest in contemporary Russian subjects. The Russian landscape was one of the most prominent of these themes, and artists’ engagement with their native land prompted a spiritual turn that, at times, harked back to the Romanticism of earlier in the century. Such concerns emerged even among the most committed of realist painters: witness the unsettling scenes of deep forest and desolate snowy wildernesses of Ivan Shishkin. A subtly spiritual mood is evoked by such works as In the Wilds of the North (after Lermontov) (1891, National Art Museum of Ukraine, Kyiv), a stark depiction of a solitary pine against the wild, snowy expanse that, as in the works of Caspar David Friedrich, positions landscape as sublime; the expression of a highly ‘spiritualised’ Russian landscape would later reach its height in the work of Isaak Levitan, most notably in such works as Above Eternal Peace (1894) and Evening Bells (1892) (both Tretyakov Gallery).

1.3 Viktor Vasnetsov and Vasily Polenov, The Church of the Saviour Not Made by Hands. 1881–82. Photograph. Abramtsevo Estate and Museum Reserve.31

In the last two decades of the nineteenth century artists also began increasingly to draw inspiration from the native tradition of folk art, exploring new motifs, colours, and styles, and experimenting in media beyond painting and sculpture. In so doing, they moved beyond conventional modes of representation — the verisimilitude and linear perspective of the Academy and the realists. The germ of these innovations first took root at Abramtsevo, a country estate some sixty kilometres outside Moscow owned by the industrialist Savva Mamontov. An aspiring artist himself, whose passion found its outlet in patronage rather than practice, Mamontov urged the artists in his circle to try their hand at theatre design, ceramics, and mosaics in an environment free from restrictions.

For the Abramtsevo artists, the medieval art and architecture of the Russian Orthodox Church became a key source of inspiration, and naturally shaped their first major collaborative art project: the design of a new church on the estate, which they named The Church of the Saviour Not Made by Hands (1881–82) (fig. 1.3). This project was fundamentally one of artistic and architectural revivalism, but it should also be viewed in the broader context of professionally trained artists’ involvement in church design and decoration during the mid- to late nineteenth century; quite apart from such private spaces as Abramtsevo, church commissions were an important source of work for artists during this period, and supplied another means for a direct encounter between modernising artists and the legacy of Russia’s religious past.32 When church building became a key ingredient in Tsar Nicholas I’s official policy of ‘Orthodoxy, Autocracy, Nationality’ (‘Pravoslavie, Samoderzhavie, Narodnost′’), adopted in 1833, artists such as Bruni and Karl Briullov painted icons and frescoes for monumental Imperial churches, such as St Isaacs Cathedral in St Petersburg (1818–58). But western styles and approaches had dominated such commissions, whereas the Abramtsevo church was inspired by early Russian art and architecture; Viktor Vasnetsov’s designs for the exterior evoked twelfth-century churches of Novgorod and Pskov.33 However, the interior, masterminded by Ilia Repin and Vasily Polenov, was an exemplar of the eclecticism characteristic of the Arts and Crafts movement: the ornamental iconostasis and mosaic floor engaged with ancient art, but the figures on the icons were painted realistically, departing from the canon, and reflecting a modern idiom.

Of the Abramtsevo artists, Mikhail Vrubel was the most radical in combining his interest in religious art with formal innovation, moving even further beyond the official canon of the Orthodox Church. Vrubel’s experimentation in media such as mosaic informed his ground-breaking paintings of the 1890s, such as Demon Seated (1890, Tretyakov Gallery) (figs. 2.7 and 2.8), in which he broke down the surface into geometric shapes, leaving areas of blank canvas. This technique, sometimes superficially compared with that of Paul Cézanne, made him arguably the first modernist artist in Russia. But, as Maria Taroutina argues in Chapter 2, a more likely catalyst for his new approach was his interest in the tradition of medieval Russian icon painting and frescoes inherited by the Orthodox Church from Byzantium. In his commission to restore the frescoes of the twelfth-century Church of St Cyril in Kyiv in 1884, Vrubel’s use of heavy stylisation and icon-like facial features reflects his serious attention to medieval precursors, whereas Vasnetsov’s frescoes for St Vladimir’s Cathedral in Kyiv (1886–96), on the other hand, demonstrate realistic modelling and a strong sense of three-dimensional space. The stylistic gulf between the two clearly illustrates the shift in priorities in Russian art at the end of the nineteenth century, from being faithful to reality, to valuing art’s expressive and formal potential. These new aesthetic considerations, which had shaken off the last vestiges of academic tradition and, unlike realism, no longer depended on the external world for representation, thus mark the beginning of the narrative of modernism in Russian art.

Symbolism and the Age of Enquiry

The spiritual turn at Abramtsevo associated with Mikhail Vrubel is now seen as the beginning of Russian Symbolism, which was allied to the broader European Symbolist movement, and thus a more international conception of Russian modernism. Other artists associated with the circle who were forging new paths in this direction included Maria Vasilevna Iakunchikova and Mikhail Nesterov. Iakunchikova, who spent her formative years at the estate before moving her main home to Paris in 1889, painted elegiac, muted landscapes of rural chapels and deserted fields, in which mood and meaning predominate. Likewise, Nesterov often depicted the surrounding Russian landscape, but prioritised religious figures and spiritual themes, as in his famed Vision of the Youth Bartholomew (1889–90, Tretyakov Gallery) (fig. 1.4). By the early twentieth century the focus upon national content had faded in the second wave of Symbolist practice, and now, spirituality could be conveyed by colour, and certain favoured themes evoking life’s essences: love, fear, motherhood, birth, and death. Critical in this respect was Viktor Borisov-Musatov, an artist from Saratov who, like Iakunchikova, was exposed to Symbolism while studying in Paris. He returned to Russia in 1898 to inspire the mystically charged colour experiments of the group of artists known as ‘Blue Rose’, who can be seen as the first ‘avant-garde’ artistic movement in Russia.

Artists of the Blue Rose continued the precedent set by Vrubel for experimenting with church design in ways which stepped further away from the established canons of the Orthodox Church. They worked on several commissions to paint the interiors of churches of the early 1900s, the most notable of which was the project executed by Pavel Kuznetsov, Petr Utkin, and Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin in 1902 to decorate the Church of the Kazan Mother of God in Saratov. Their bold frescoes were so far from the Orthodox canon that they provoked public outcry and were destroyed. Similarly, designs by Nicholas Roerich for the church at Talashkino (1909–11) — the second major centre of the national revival in decorative art, seen as the inheritor of Abramtsevo’s legacy — were too radical for the Orthodox Church to consecrate the building, as Louise Hardiman discusses in Chapter 3. The application of new developments in secular painting to church design reflected the important place religious art had come to occupy in Russian modernism. They also underline the fact that while artists engaged with Orthodox artistic traditions, the church’s official canon was largely ignored. This gave rise to subjective and imaginative renderings of church design that were anathema to its strict codes of representation.

1.4 Mikhail Nesterov, The Vision of the Youth Bartholomew, 1889–90. Oil on canvas, 160 x 211 cm. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Photograph in the public domain. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mikhail_Nesterov_001.jpg

Fear of the noxious effects of materialism and industrialisation continued to grow as the new century drew near, and thinking beyond ordinary perception and the outside, tangible world took on new significance.34 The paintings of the Russian Symbolists had made manifest in images the ideas that were emerging in Silver Age poetry and philosophy, and responded to an existential disquiet which conventional religion seemed unable to answer. This wider Symbolist movement, involving such figures as Aleksandr Blok, Andrei Bely, Aleksandr Scriabin, and Vladimir Solovev, dominated Russian culture at and around the fin de siècle. Most influential of all was Solovev, whose Spiritual Foundations of Life (Dukhovnye osnovy zhizni) had been published in the early 1880s.35 Symbolism influenced later religious thinkers of the early twentieth century too, notably Nikolai Berdiaev, Pavel Florensky, and Sergei Bulgakov. They inaugurated a new breadth to the notion of the spiritual in art and literature, exploring theological ideas outside of Orthodoxy such as Sophiology. The turn away from materiality espoused by the Symbolists engineered a shift in artists’ attention from conventional Orthodoxy to broadly conceived ideas of spirituality. Their influence was far-reaching and enduring, as Jennifer Brewin’s discussion of Symbolist trends in Soviet Georgia in Chapter 11 witnesses. In this respect, the new research on Symbolism presented in several chapters of this volume is of especial importance, and has highlighted the lack of a comprehensive monograph on the Symbolist movement in Russian art.36

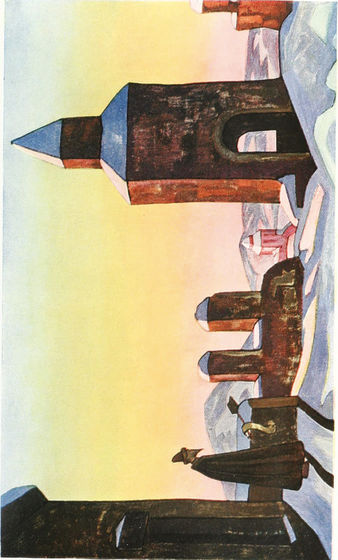

With Symbolist discussions of higher levels of reality and inner expression already in place, mysticism and occultism, too, became increasingly popular in Russia in the early 1900s, as well as the Theosophy of Madame Helena Blavatsky, who co-founded the Theosophical Society in New York in 1875.37 The notion that the artist had privileged access to higher or inner forms of reality as a ‘prophet’ or ‘superman’ was taken up by artists such as Kandinsky, Malevich, and Roerich, playing roles mirroring those which Dostoevsky and Tolstoy (once described as a “seer of the flesh” and a “seer of the soul” respectively) had famously adopted in literature.38 An active Theosophist, Roerich even founded his own spiritual system, Agni Yoga, together with his wife Elena, and, in the 1920s, organised a highly publicised expedition to India, Tibet, and Mongolia. His vividly coloured canvases often portrayed mystical landscapes and figures, and reflected a preoccupation with rites and rituals (fig. 1.5). Roerich’s work serves as a reminder that questions of the spiritual in Russian art are not only about responses to a religious tradition entwined with the country’s nationalism.

New areas of science and pseudoscience investigating areas beyond physical reality and the natural world also permeated the arts. The first X-rays were shown in public at the Berlin Physical Society in 1896, and the possibility of non-Euclidian geometry and the fourth dimension — as first discussed by Charles Howard Hinton in ‘What is the Fourth Dimension’ (1884), and expanded upon by Petr Ouspensky in The Fourth Dimension (1904) — became of interest to the avant-garde in particular. These ideas helped to shape the theories underpinning artists’ experiments with non-objective forms in the early 1910s, such as Kandinsky’s notion of the ‘inner’ sound or vibration of the soul. This concept was embodied in his famed ‘Compositions’, among others, for example, Composition VII of 1913 (Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow) (fig. 1.6). A further interesting figure in this respect was the Lithuanian Symbolist painter Mikalojus Čiurlionis, who shared with Kandinsky the credo that art was part of a world of higher perception and beyond physical reality.39 Both men claimed to possess the gift of ‘synaesthesia’ — the ability to see colours as sounds; both were synthetists too, working across multiple media. Čiurlionis, for example, was a composer as well as artist, and, like Kandinsky, gave many of his paintings musical titles. Other theories giving rise to purely abstract works of art included Mikhail Larionov’s Rayism — the depiction of rays of light reflecting off a physical object — and Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematism — the expression of higher levels of consciousness through simple geometric shapes. Artists’ serious engagement with spiritual ideas, as well as contemporary developments in science, psychology, and music thus led to some of the most pioneering work of Russian modernism.

1.5 Nicholas Roerich, The Call of the Bells (from the old Pskov series), 1897. As reproduced in International Studio, 70, 279 (June 1920), facing p. 60. Photograph in the public domain. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:International_studio_(1897)_(14760097306).jpg

The Icon Rediscovered

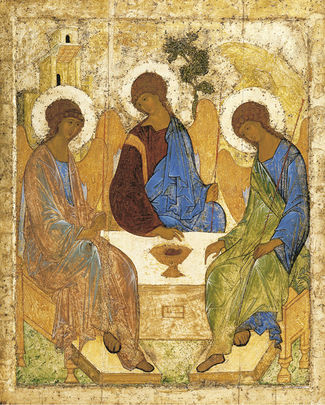

The artistic traditions of the Orthodox Church, and icon painting in particular, continued to play an important part in the work of artists during this period. Until the late nineteenth century, icons had no place in the fine arts in Russia — they were not considered artistic objects. With their meaning intrinsically linked to the context of the Church, they served as a physical medium through which believers could access the Holy Spirit. Their creators were often unknown, and they were re-painted time and again over the years; often they were blackened from the accumulation of dust and soot from incense and sometimes were encased within an oklad — a metal, ornamental casing that covered much of the painted surface. The icon historian Nikodim Kondakov (discussed by Wendy Salmond in Chapter 8) blamed the vogue for western culture from the reign of Peter the Great onwards for this widespread neglect of icons among Russians.40 During Nicholas I’s reign (1825–55) in the mid-nineteenth century, however, Orthodox Church culture became of renewed interest to the government. Restoration of medieval church frescoes began, while icons started to be removed from churches and placed in museums.41 The first proper museum collections of icons appeared in the 1860s, yet these were only showcased to the public specifically as art for the first time in 1898 at an exhibition of medieval Russian art.42 Moving into the early twentieth century, Shirley Glade and Jefferson Gatrall mark two seminal moments in this rediscovery and rehabilitation of icon painting that had an enormous impact on modernist artists: firstly, the restoration of one of the most celebrated icons — Andrei Rublev’s Trinity (fig. 1.7) — between 1904 and 1906, and secondly, the Exhibition of Old Russian Art which took place in Moscow in 1913.43 A restoration team led by Vasily Gurianov stripped away layers of overpaint and varnish to reveal unexpectedly bold colours and the sophisticated technical prowess of Rublev, who soon became a canonical figure in the history of Russian art.44 This led to other important restoration projects, and dealers and collectors scoured remote Russian provinces in search of unknown masterpieces. Prominent art collectors, such as Ilia Ostroukhov and Stepan Riabushinsky, hired hereditary icon painters (ikonniki) to work on their private collections.45 The exhibition of 1913, which included objects from these collections, was unprecedented in its range, and showed previously unseen fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Novgorod works. Other ecclesiastical objects such as embroideries and medieval manuscripts were also on display. Sponsored by the state, the display served to legitimise the icon as a symbol of Russian national culture.46

1.6 Vasily Kandinsky, Composition VII, 1913. Oil on canvas, 200 x 300 cm. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.47

In tandem with restorers, artists thus rediscovered the icon as an object of artistic creation and a rich source of inspiration. As new attitudes towards the collection, display, and conservation of icons were only just beginning during the 1880s — this volume’s starting point — artists of the fin de siècle did not yet have thirteenth-century Novgorod icons that had been newly restored and cleaned to inspire them. As Chapters 2, 3, and 4 by Taroutina, Hardiman, and Myroslava M. Mudrak discuss, the first generation of modern artists mainly responded to religious art in situ, such as church architecture and mural painting. On the other hand, as Chapters 5 and 6 by Oleg Tarasov and Nina Gurianova explain, the later, more radical generation of Russian avant-garde artists, like their counterparts in Europe, looked to other so-called ‘primitive’ art forms for new approaches to representation, and their search for new material would lead to a re-examination of the artistic potential of icons. Across Europe, avant-garde artists responded to objects such as African masks, Japanese woodcuts, and children’s drawings, which were unfettered by western artistic conventions such as chiaroscuro and modelling that had dominated painting since the Renaissance. For Russian avant-garde artists, the source of ‘primitive’ art came from within as they saw Russia as more closely aligned with the east in its origins. Western artistic influences needed to be cast off, in favour of crafting an intrinsically national culture. As Aleksandr Shevchenko wrote in his text outlining this movement — Neoprimitivism — in 1913, “The spirit of […] the East, has become so rooted in our life that at times it is difficult to distinguish where a national feature ends and where an Eastern influence begins […]. The whole of our culture is an Asiatic one”.48 Russian culture abounded with examples of art that was less constrained by western pictorial traditions: icons, Russian broadsheet prints (lubki), trays, and signboards offered “the most acute, most direct perception of life — a purely painterly one, at that”.49

The pictorial characteristics of icon painting — inverse perspective, heavy outlining, general flatness, and large, bold areas of colour — informed the avant-garde’s new artistic language. This approach found little favour with the press and public, and exhibitions of the avant-garde were met with hostility and controversy. As with earlier artists such as Vrubel, this was especially the case when artists applied experimental approaches to religious themes. The censor, for example, removed Goncharova’s Evangelists (1910–11, State Russian Museum) from the Donkey’s Tail exhibition in Moscow in 1912 for the seemingly sacrilegious combination of a sacred subject with such a vulgar exhibition title.50 Such reactions did not discourage artists from underlining the link between the new art and icon painting: Larionov pointedly staged an exhibition of icon patterns (podlinniki) and lubki in Moscow in 1913 (129 icons came from his own collection) at the same time as the ‘Target’ — the latest exhibition of avant-garde art he had organised.51 The deliberate juxtaposition emphasised that both shows were united in their rejection of the west, and that religious art — above all, the icon — was the most revered of native, primitive sources reawakened by Russian artists. As the émigré artist Boris Anrep claimed, “For us Russians, who have been raised to revere the divine countenances created by the piety of our icon painters […] Matisse’s art is neither a great revelation nor a great novelty”.52 Matisse himself was famously riveted by Russian icons on a visit to Moscow in 1911; in a statement echoing the sentiments of the avant-garde, he wrote: “The icon is a very interesting type of primitive painting. Nowhere have I ever seen such a wealth of colour, such purity, such immediacy of expression.”53 And so an entire generation of Russian artists was stimulated by the icon not only for its aesthetics but also as a symbol of what Russian art could achieve outside of the west.54

1.7 Andrei Rublev, Trinity, 1411 or 1425–27. Tempera on wood, 142 x 114 cm. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Photograph in the public domain. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Angelsatmamre-trinity-rublev-1410.jpg

Revolution and its Aftermath

The October Revolution of 1917 ushered in a new era for the arts in Russia, and, under the anti-religious Bolshevik regime, continued interest in spiritual ideas and culture became highly controversial and increasingly dangerous. The Soviet government stripped the Orthodox Church of its property rights and launched campaigns to seize, sell, or destroy its art and valuables. Yet amid the destruction of churches and ecclesiastical objects appeared prodigious efforts to save them. The renewed appreciation of the icon’s artistic value in the early 1900s initially continued to flourish in the years following the Revolution. The secular context of the museum was seen as a safe space where the centuries-long damage that icons had endured in the hands of the Church, such as overpainting and failure to clean layers of black soot from candles and incense, could be rectified. Previously unknown ancient icons were discovered on expeditions to monasteries and churches in the Russian north, and fresh restoration projects, notably those of the Trinity and Vladimir Mother of God icons, led Soviet scholars to condemn earlier interpretations of the icon’s history, as Wendy Salmond discusses in Chapter 8. The government’s anti-religious campaigns of the late 1920s, however, heralded a devastating new wave of iconoclasm and fierce persecution of those who defended religious culture. Figures such as priest and scholar Pavel Florensky, restorer and art historian Iuri Olsufev, and art historian Nikolai Punin, whose work on the link between the icon and the avant-garde is discussed by Natalia Murray in Chapter 10, were arrested and executed. Yet, despite the attempts of the authorities to undermine the Russian spiritual tradition, it would survive in art in a number of ways. The instinct to practise religion could not, of course, be completely quashed, and artists continued to engage with religious and spiritual themes. In some cases this practice moved underground, in others, abroad; in yet others, echoes of pre-Revolutionary spiritual approaches could be found at the periphery of the Union, as Jennifer Brewin testifies in Chapter 11.

With religious practice and spirituality increasingly under threat in Russia itself, the Russian diaspora tasked itself with keeping her traditions alive abroad to bequeath to future generations. The mass exodus of approximately 1.5 million Russian citizens to countries around the world was the most dramatic but often overlooked consequence of the Revolution and subsequent Civil War (1917–22). For this widespread population of émigrés, which included many modernist artists, including Kandinsky, Roerich, Goncharova, and Larionov, preserving Russian national culture was not only of collective benefit to society, but had a very personal dimension — it helped re-forge their individual connection to home. For many, the rejuvenated Orthodox Church abroad became a symbol of sustaining pre-1917 rituals and traditions, especially those facing eradication in the Soviet Union. While artists remaining in the Soviet Union were barred from working on church commissions or religious subjects, those who had emigrated received new opportunities to engage with religious art outside Russia’s borders (the case of one such émigré, Dmitry Stelletsky, is discussed by Nicola Kozicharow in Chapter 9). The practice of icon painting, for example, gained new-found interest abroad, and, in 1927, the Icon Association — a new school of icon painting — was established in Paris with artists such as Ivan Bilibin and Stelletsky among its members. This continuation of Russian religious art in emigration symbolises the broader endurance of spiritual values — and even modernism itself — in the face of its suppression in the Soviet Union. The spiritual dimensions of Russian modernism thus ultimately transcended borders, and evaded any political efforts to curtail their lasting power.

Modernism and the Spiritual: From Symbolists to Soviets

This book highlights the importance of the thriving, multifarious dialogue on spirituality and religion that permeated the visual arts in Russia from the late nineteenth to mid-twentieth centuries. Arranged in roughly chronological order, the ten essays rethink existing interpretations of spiritual themes and influences in the oeuvre of an individual artist or artists (Chapters 2, 4, 6, and 11 by Taroutina, Mudrak, Gurianova, and Brewin) and enhance our understanding of how mediating figures were instrumental in shaping perceptions, whether of spirituality and nationality (Chapters 3, 7, and 9 by Hardiman, Borkhardt, and Kozicharow), or such fundamental questions as the role of icons in, or as, art (Chapters 5, 8, and 10 by Tarasov, Salmond, and Murray). Our objective is to illustrate precisely the diversity of approaches among modern artists to the notion of spirituality, and document their soul-searching, exploratory quests, which are so characteristic of the period. These essays illustrate more clearly the ways in which some painters (for example, Kandinsky and Malevich) assumed the role of artist as prophet. At the same time, though modernism has been associated with a sense of individuality and artistic freedom, age-old practical considerations remained, such as responding to the desires and requirements of patrons and consumers.

After Kandinsky and his theories, it is the influence of the icon upon Russian modernism which has received the most scholarly attention in recent years. In this volume, we seek to extend and deepen this analysis in several ways. A number of our authors expand the discussion of Orthodox artistic tradition to include other media such as mosaic, fresco, and Old Believer icons. While the significance of avant-garde artists such as Malevich remains a central focus, experiments by artists who have typically been excluded from scholarly discussions are here brought to the fore. Under the broad banner of Russian modernism, the book includes such figures as Vrubel — an early practitioner of more radical approaches to painting — and Stelletsky, whose work the Russian avant-garde criticised for being too reliant on the formal characteristics of religious art. Moreover, it re-emphasises how modernising tendencies spanned a wide range of artistic movements across the late Imperial era; for example, it adds weight to the case for integrating the Arts and Crafts movement, in its Russian guise, into the longer history of Russian modernism.

The volume begins in the late nineteenth century with Maria Taroutina’s chapter on Vrubel (Chapter 2), whose art foreshadowed the seismic shift towards abstraction.55 Taroutina considers the radical new ways in which this creative and experimental artist interpreted the Orthodox artistic tradition. Her chapter shifts the chronology of the avant-garde’s engagement with icons back by two decades, to the period associated with the neo-national and Symbolist movements. Taroutina shows that as early as the 1890s the icon was already more than what Gatrall has described as a “parochial craftwork […], an antiquarian curio”.56 She strengthens the case for Vrubel’s modernism, not only in her analysis of his formal innovations (which she contends bore relation to his early experiences in mosaic) but also in his idiosyncratic use of religious art as a source. Vrubel found his inspiration mostly in national sources; drawing from the Byzantine Orthodox tradition, he interwove fresco, icon, and religious (or mythological) symbolism in his oeuvre, for example, in his use of the recurring motif of the demon. His example illustrates dramatically the intense complexity of the spiritual question for the Russian fin-de-siècle artist.

In Chapter 3, Louise Hardiman considers aspects of the neo-national movement and the fin de siècle, turning the spotlight upon the Talashkino colony and Russian Arts and Crafts. Proposing the existence of a shift from Orthodoxy at Abramtsevo to a less conventional spirituality at Talashkino, this chapter re-examines the debate around the ‘Church of the Spirit’ (‘Khram dukha’) commissioned by Talashkino’s founder, Maria Tenisheva, and finally completed in 1914 with the assistance of Roerich. It then charts a common thread toward esotericism by exploring the spiritual turn to Theosophy of Aleksandra Pogosskaia, one of Tenisheva’s collaborators, who devoted her career to selling Russian peasant art and Arts and Crafts, primarily in the west. Hardiman suggests that the beliefs espoused by the Theosophical Society, of which Pogosskaia, and later Roerich, were members, correlated strongly with the pagan traditions inherent in Russian folk belief. This led to a scenario in which unconventional belief systems and neo-nationalist trends in art could naturally intersect.

Turning to the avant-garde, Myroslava M. Mudrak in Chapter 4 extends existing accounts of the relationship of Kazimir Malevich with religion and spirituality, by concentrating on his early Symbolist work and its relation to Ecclesiastic Orthodoxy. Suprematism, the artist’s self-proclaimed new artistic movement of the mid-1910s, is usually thought of as sui generis, and necessarily secular — a replacement for the prevailing Orthodoxy. Indeed, as Christina Lodder reminds us in her catalogue essay for Tate Modern’s Malevich retrospective exhibition in 2014, the artist’s placement of Quadrilateral (1915) (the painting now known as Black Square) (fig. 5.2) in the ‘red (or beautiful) corner’ of the room (krasnyi ugol) at the Last Futurist Exhibition ‘Zero Ten’ (0.10) (fig. 5.3) was “an iconoclastic action, annihilating the old values and shocking the public”.57 Yet, like that of Kandinsky, Malevich’s relationship with the Russian spiritual tradition is complex and multi-faceted, not least his transformation from the Catholicism of his upbringing to his revolutionary, apparently secular Suprematism. Through her careful analysis of Malevich’s early work, Mudrak supplies a new interpretation of the artist’s engagement with his native religious and spiritual traditions.

Oleg Tarasov, in Chapter 5, picks up the story with Malevich at the point where Mudrak ends, explaining clearly how Malevich’s concept of Suprematism drew directly from the principles of the icon; Tarasov then considers the importance of the icon to the wider Russian avant-garde. In this sense his chapter, reflecting the extensive scholarship that led to his groundbreaking texts, Icon and Devotion (2002) and Framing Russian Art (2011), acts as the centrepiece of this book. It conveys the central story of this period — the meaning, role, and influence of ‘the spiritual’ in the work of the avant-garde as they attempted to find a new spirituality based on a “common search for what we might call essences”.58 Tarasov maintains that, unlike representational art, abstract paintings and icons are ‘signs’ — images in which symbol equals meaning. Thus “the real project of the avant-garde was not formal innovation […] but the attempt to place the individual in touch with the transcendental and to transform the world on the basis of ‘ideas’ revealed only to the artist”.59 Here there is an obvious debt to the notion of artist as prophet, and, echoing Chapter 4, the Theosophical concept of wisdom and long-held truths that are known to a select few initiates.

In Chapter 6 the focus is upon two other prominent figures of the avant-garde, Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov. Nina Gurianova adds new depth to existing analyses of these artists, contending that their religious influences should be viewed in the context of the Old Belief movement, rather than contemporary Orthodoxy. The Old Believers were instrumental in the preservation and conservation of ancient icons, lubki, hand-made and hectograph books, manuscripts and the like, resulting in what Gurianova calls a “brief ‘golden age’ of Old Believer culture” between 1905 and 1917.60 Other influential aspects of this movement adopted by Futurist and Neoprimivitist artists included the focus on apocalyptic symbolism and metaphor. In a detailed account of sources and art works, the chapter traces how national identity and past spiritual traditions were inextricably linked.

Chapters 7 and 8 shift the focus from Russia to the west, and the role of critics in shaping interpretations of religious art and the spiritual tradition. Specifically, they illustrate how the notion of a Russian spiritual tradition in art (Chapter 7) and the Russian icon itself (Chapter 8) were received outside Russia. In looking at Kandinsky through the eyes of German critics, Sebastian Borkhardt’s analysis in Chapter 7 provides another perspective from which to view the artist and his seminal text, On the Spiritual in Art. His account provides a stark contrast with Rebecca Beasley’s recent analysis of Kandinsky’s impact on the British Vorticist movement: Beasley finds that the British avant-garde saw Kandinsky as German, rather than Russian (even though the founding artists of The Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter) were of both nationalities), while Borkhardt shows that many German critics felt that he was thoroughly Russian.61 In Germany the reception of the artist during the 1910s drew heavily upon existing perceptions of Russia and Russian art, specifically its ‘eastern mysticism’ as opposed to ‘western rationalism’. But, in a fascinating exploration of differing critical stances, Borkhardt argues that the ideas of Wilhelm Worringer, who had linked abstraction with the “transcendental” character of the Gothic (“a supra-temporal principle that pervaded ‘northern’ culture”), may have led another modernist critic, Paul Fechter, to redefine Kandinsky’s spirituality in terms of “old Gothic soul” and bring his art into a German cultural context.62 When Fritz Burger subsequently categorised these commonalities as part of the “new cosmic life” of the modern era, these ideas crystallised into those which seem again to repeat universal spiritual themes.

Wendy Salmond’s engaging account of the history of Ellis Minns’s translation of The Russian Icon by Nikodim Kondakov in Chapter 8 sheds important new light on how Kondakov was seen initially as a pioneer in the study of the Russian icon during the pre-Revolutionary period, but his ideas fell out of favour by the 1920s. Salmond suggests that his reputation as an expert would have endured far longer, had it not been judged retrospectively through the lens of subsequent developments in conservation and the more recent scholarship of younger intellectuals such as Pavel Muratov and Aleksandr Anisimov. Defending Kondakov’s scholarship, she nevertheless shows how Minns took on the role of a skilled mediator when creating his translation — he wanted the text to be available in the west but also tried to adjust some of its more outdated material. Salmond considers The Russian Icon’s reception in the west during the Soviet period, and ends with an appraisal of its contemporary relevance. Above all, she stresses that this work, and its translation, bear witness to “a particular moment in the unfolding history of the Russian icon”, pointing to “the bitter irony” of its appearance in 1928, when the “worst period of Militant Atheism and the wholesale destruction of icons began”.63

Both Borkhardt’s and Salmond’s chapters demonstrate vividly how, where reception and cross-cultural exchange are concerned, the mediator, the process of mediation, and the culturo-historical context in which it takes place are of prime significance. In literature, the distorting impact of translation and associated intrusion of the mediating point of view are long-established truths; likewise, in the reception of art, the effects of this process lead to equally surprising consequences. For Borkhardt, the German historical context is all; despite a generally receptive, though polarised, interpretation of Kandinsky’s work and his theories among critics earlier in the twentieth century, the advent of Nazism led to denunciation of the artist. By contrast, in the case of Minns and Kondakov, it had been the foreigner who sought to reclaim — for the international audience — the reputation of the national whose theories had become discredited through changes in political ideology.

The last three chapters deal with the period following the October Revolution of 1917. In Chapter 9 Nicola Kozicharow maintains the focus on Russian art in Europe, by examining Dmitry Stelletsky’s designs for the icons and frescoes of what is perhaps the most significant Orthodox church outside of Russia — Saint-Serge in Paris — which became a bastion of Orthodox faith for the tens of thousands of Russians who fled the turmoil of the Revolution and subsequent Civil War and settled in France. As the first theological institute beyond Russia’s borders, Saint-Serge was also a new centre of Orthodox theology, attracting thinkers such as Nikolai Berdiaev and Bulgakov. Returning to the theme of church commissions, Kozicharow explores the designs for the church interior in order to question the avant-garde’s condemnation of the artist’s work as unoriginal and too derivative of medieval precursors. His radical approach to church design, which continued the late nineteenth-century revivalist (or neo-Russian) style in emigration, pushed the boundaries of what was deemed acceptable within the Orthodox canon. Stelletsky’s strict Orthodox faith also raises a key issue that has gone relatively unexplored in scholarship, namely the role of artists’ beliefs in approaching religious themes in their work.

Tracing another path of critical engagement with icons during the early to mid-twentieth century, Chapter 10 returns to Russia. Natalia Murray continues to restore the important historical legacy of Nikolai Punin in Russian modernism, a process which she began in her biography of 2012.64 Murray explains how Punin’s study of icon painting shaped his interpretation of the avant-garde, leading to his conclusion that for these artists icons were “a revelation […], the highest ideal”.65 She describes how Punin’s criticism was pioneering in its approach, appearing at a time when artists themselves were still working out these ideas. In the early Soviet period, Punin fought to preserve icon painting in Mstera while he was Head of the Visual Arts Department of the People’s Commissariat of Enlightenment in Petrograd (Narkompros) and Commissar of the Hermitage and Russian Museums. The account ends poignantly with the personal suffering of Punin under Stalinist repression, after he refused to compromise his modernist and spiritual principles and was incarcerated as a result, dying in a Gulag camp in 1953.

Chapter 11 sets the chronological end point of this collection during the Thaw. However, in reprising some themes of this book’s early chapters, it illustrates the enduring nature of the ‘spiritual’ as an artistic influence, and Symbolist tendencies in particular, despite the shift to secular Soviet rule and the imposition of the official style of socialist realism in 1934, which condemned continued interest in modern movements or themes as ‘formalist’. Jennifer Brewin concentrates upon a single artist, Ucha Japaridze (1906–88), in Georgia. Though existing scholarship has cast Japaridze as a staunch exponent of socialist realism, Brewin recognises his formative influences as the Symbolist poetry group, the Blue Horns, and the Georgian Symbolist painter, Lado Gudiashvili. In her close readings of several of his paintings, she seeks to overturn a realist reading and emphasises the enduring legacy of spiritual influence in the secularised artistic space of Soviet Georgia even as late as the 1960s. In addition, Brewin raises the issue of how modernist trends were interpreted by artists at the periphery of the Union.

What becomes clear as the overarching chronology unfolds is that the detailed essays here serve as staging posts in a narrative of Russian artistic modernism in which the engagement of artists, critics, and scholars with the religious and spiritual tradition is fundamental. This engagement is, we contend, the driving force behind some of the most significant artistic innovations of the period. From the Orthodox — the church’s art and rituals — to the ‘un-Orthodox’ — spirituality, mysticism, and esotericism — new ideas and artistic approaches abounded. Coming from within and beyond the ranks of the Russian avant-garde, artists are instead located within the wider picture of modernism in Russia, and reflect a number of institutional positions and associations. The geographical and chronological scope of the intersection between the spiritual and the arts is also expanded, showing that the story extends far beyond Moscow and St Petersburg, and lasts far longer than has previously been claimed. Within this more widely framed discussion, the relationship between the spiritual and modernism in Russian art deserves proper study, and revisiting its well-trodden histories and exploring its uncharted corners becomes all the more valuable.

1 Clement Greenberg, ‘Modern and Postmodern’, in Late Writings, ed. by Robert C. Morgan (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2003). [First given as the William Dobell Memorial Lecture, Sydney, Australia, 31 October 1979; first published in Arts 54, 6 (February 1980), http://www.sharecom.ca/greenberg/postmodernism.html].

2 See, for example: Charlene Spretnak, The Spiritual Dynamic in Modern Art (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), p. 129; Maurice Tuchman, ‘Hidden Meanings in Abstract Art’, in The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890–1985, ed. by Maurice Tuchman, et al. (exh. cat., Los Angeles County Museum of Art, New York: Abbeville Press, 1986), pp. 17–61 (p. 18).

3 See, for example: John E. Bowlt, ‘Orthodoxy and the Avant-Garde: Sacred Images in the Work of Goncharova, Malevich, and Their Contemporaries’, in Christianity and the Arts in Russia, ed. by William C. Brumfield and Milos M. Velimirovic (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991), pp. 145–50; Andrew Spira, The Avant-Garde Icon. Russian Avant-Garde Art and the Icon Painting Tradition (Aldershot: Lund Humphries Publishers Ltd, 2008); Jane Sharp, Russian Modernism between East and West: Natal′ia Goncharova and the Moscow Avant-Garde (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

4 Vasily Kandinsky, ‘On the Spiritual in Art’, in Kandinsky: Complete Writings on Art, ed. by Kenneth C. Lindsay and Peter Vergo (Boston: G. K. Hall & Co., 1982), Vol. 1, pp. 121–219. The first English translation of ‘On the Spiritual in Art’ by Michael T. H. Sadler, entitled The Art of Spiritual Harmony (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1914), can be read online: https://archive.org/details/artofspiritualha00kandrich. Also see John E. Bowlt and Rose Carol Washton-Long, The Life of Vasilii Kandinsky in Russian Art: A Study of ‘On the Spiritual in Art’ (Newtonville, MA: Oriental Research Partners, 1980); Lisa Florman, Concerning the Spiritual — and the Concrete — in Kandinsky’s Art (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2014).

5 For a recent discussion of theosophical influences in Kandinsky’s oeuvre, see Marian Burleigh-Motley, ‘Kandinsky’s Sketch for “Composition II”, 1909–1910: A Theosophical Reading’, in From Realism to the Silver Age: New Studies in Russian Artistic Culture, ed. by Rosalind P. Blakesley and Margaret Samu (De Kalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2014), pp. 189–200.

6 Sixten Ringbom, ‘Art in the “Epoch of the Great Spiritual”: Occult Elements in the Early Theory of Abstract Painting’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 29 (1966), 386–418, https://doi.org/10.2307/750725. Also see Sixten Ringbom, The Sounding Cosmos. A Study in the Spiritualism of Kandinsky and the Genesis of Abstract Painting (Åbo: Åbo Akademi, 1970).

7 S. Arthur Jerome Eddy, Cubists and Post-Impressionists (Chicago, IL: McClurg, 1914); Sheldon Cheney, A Primer of Modern Art (New York: Boni & Liveright, 1924); Harold Rosenblum, Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition: Friedrich to Rothko (New York: Harper & Row, 1975); The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890–1985, ed. by Maurice Tuchman, et al. (exh. cat., Los Angeles County Museum of Art, New York: Abbeville Press, 1986); Roger Lipsey, An Art of Our Own: The Spiritual in Modern Art (Boston: Shambhala, 1988); Piet Mondrian 1872–1944: A Centennial Exhibition (exh. cat., Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 1971); Art of the Invisible (exh. cat., Bede Gallery, Jarrow, 1977); Kunstenaren der Idee: Symbolistische tendenzen in Nederland ca. 1880–1930 (exh. cat., Haags Gemeente-museum, The Hague, 1978); Abstraction: Towards a New Art (exh. cat., Tate, London, 1980).

8 Photograph in the public domain. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kandinsky,_Umschlag_über_das_Geistige_in_der_Kunst,_ver._1911,_dat._1912.jpg

9 James Elkins, On the Strange Place of Religion in Contemporary Art (New York and London: Routledge, 2004), p. 78.

10 Evgeniia Petrova, ‘“Zemnaia zhizn” Iisusa Khrista v russkom izobrazitel′nom iskusstve’, in Iisus Khristos v khristianskom iskusstve i kul′ture XIV–XX veka, ed. by Evgeniia Petrova (St Petersburg: Palace Editions, 2000), pp. 13–24; The Russian Avant-Garde: Siberia and the East, ed. by John E. Bowlt, Nicoletta Misler, and Evgeniia Petrova (exh. cat., Florence, Palazzo Strozzi; Skira, 2013).

11 James D. Herbert, Our Distance from God. Studies of the Divine and the Mundane in Western Art and Music (Berkeley, CA: University of California, 2008); Lynn Gamwell, Exploring the Invisible: Art, Science, and the Spiritual (Princeton, NJ and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). ‘Modernism and Spirituality’, Conference at Tate Modern, Linda Nochlin and Sarah O’Brien-Twohig, 2013; Sam Rose, ‘How (Not) to Talk About Modern Art and Religion’, at ‘Modern Gods: Religion and British Modernism’ symposium, The Hepworth Wakefield, 24 September 2016; Thomas Laqueur, ‘Why The Margins Matter: Occultism and the Making of Modernity’, Modern Intellectual History, 3 (April 2006), 111–35, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1479244305000648; Leigh Wilson, Modernism and Magic: Experiments with Spiritualism, Theosophy and the Occult (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2012); James Elkins, On the Strange Place of Religion in Contemporary Art (New York and London: Routledge, 2004); Charlene Spretnak, The Spiritual Dynamic in Modern Art (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014); Leah Dickerman, ‘Vasily Kandinsky, Without Words’, in Inventing Abstraction 1910–1925: How a Radical Idea Changed Modern Art, ed. by Leah Dickerman and Matthew Affron (London: Thames & Hudson, 2010), pp. 50–53; Enchanted Modernities: Mysticism, Landscape and the American West, exhibition at the Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art, Utah State University, 2014; Jonathan A. Anderson and William A. Dyrness, Modern Art and the Life of a Culture: The Religious Impulses of Modernism (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2016).

12 See, for example: Peg Weiss, Kandinsky and Old Russia: The Artist as Ethnographer and Shaman (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1995); Charlotte Gill, ‘A “Rupture Backwards”: The Re-emergence of Shamanic Sensibilities Amongst the Russian Avant-Garde from 1900–1933’ (unpublished PhD thesis, University of Durham, 2015).

13 Elkins, p. 1.

14 See, for example: M. N. Tsvetaeva, Khristianskii vzgliad na russkoe iskusstvo: ot ikony do avangarda (St Petersburg: R. Kh. G. A., 2012); Anna Lawton, ‘Art and Religion in the Films of Andrei Tarkovskii’, in Christianity and the Arts in Russia, pp. 151–64; John E. Bowlt, ‘Esoteric Culture and Russian Society’, in Tuchman, The Spiritual in Art, pp. 165–83; Charlotte Douglas, ‘Beyond Reason: Malevich, Matiushin, and their Circles’, in Tuchman, The Spiritual in Art, pp. 185–99; Jane Sharp, ‘“Action-Paradise” and “Readymade Reliquaries”: Eccentric Histories in/of Recent Russian Art’, in Byzantium/Modernism: The Byzantine as Method in Modernity, ed. by Roland Betancourt and Maria Taroutina (Leiden: Brill, 2015), pp. 271–310.

15 See, for example, the treatment of Russian art in survey texts such as Realism, Rationalism, Surrealism: Art Between the Wars, ed. by Briony Fer, David Batchelor, and Paul Wood (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993), pp. 87–169; Art Since 1900: Modernism, Antimodernism, Postmodernism, ed. by Hal Foster, et al. (London: Thames & Hudson, 2004), pp. 174–272.

16 See, for example, Bowlt, ‘Esoteric Culture and Russian Society’; Douglas, ‘Beyond Reason: Malevich, Matiushin, and their Circles’.

17 This has most recently been taken up in the United Kingdom by the Leverhulme-funded network ‘Enchanted Modernities: Theosophy, Modernism and the Arts, c.1865–1960’ at York University, 2012–15, and the symposium ‘Modern Gods: Religion and British Modernism, 1890–1960’, The Hepworth Wakefield, 24 September 2016.

18 Rosalind P. Blakesley, The Russian Canvas: Painting in Imperial Russia, 1757–1881 (New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press, 2016), p. 154.

19 Blakesley, The Russian Canvas, p. 152.

20 Ibid.

21 On the relationship between artistic realism and literary realism of the period, see Pamela Davidson, ‘Aleksandr Ivanov and Nikolai Gogol’: The Image and the Word in the Russian Tradition of Art as Prophecy’, The Slavonic and East European Review, 91, 2 (April 2013), 157–209, https://doi.org/10.5699/slaveasteurorev2.91.2.0157

22 Blakesley, p. 163.

23 Ibid., p. 160.

24 Ibid., p. 161.

25 Davidson, ‘Aleksandr Ivanov and Nikolai Gogol″.

26 See, for example, Vissarion Belinsky, ‘Letter to Gogol’, in Russian Intellectual History: An Anthology, ed. by Marc Raeff (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1966), p. 252.

27 Dmitry Sarabianov, Russian Art: From Neoclassicism to the Avant-Garde: 1800–1917 (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1990), p. 130.

28 Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy, Tolstoy’s Letters: Volume II. 1880–1910, trans. by R. F. Christian (London: The Athlone Press, 1978), p. 508.

29 Fyodor Dostoevsky, ‘A Propos of the Exhibition’, A Writer’s Diary: Vol. I. 1873–1876 (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1994), p. 216.

30 Translator’s footnote in Tolstoy, Tolstoy’s Letters, p. 460.

31 © 2013 A. Savin, CC BY-SA 3.0. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Abramtsevo_Estate_in_Jan2013_img06.jpg

32 The employment of fine artists to create religious art was not an entirely new phenomenon, just as icon painters training as fine artists was also commonplace. For example, the two major portraitists of the late eighteenth century — Dmitry Levitsky and his pupil, Vladimir Borovikovsky — began their careers as icon painters in Ukraine.

33 William Craft Brumfield, The Origins of Modernism in Russian Architecture (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1991), p. 35.

34 Spretnak, The Spiritual Dynamic, pp. 64–65.

35 Vladimir Solov′ev, ‘Dukhovnye osnovy zhizni’ (1882–84). For the collected works, see Vladimir Solov′ev, Sobranie sochinenii (12 vols.) and Pis′ma (4 vols.), 16 vols. (Brussels: Zhizn′ s Bogom, third edition, 1966–70).

36 In terms of English language scholarship, Avril Pyman’s landmark A History of Russian Symbolism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984) mainly concentrates on literature. Bowlt’s doctoral thesis of 1972 and his articles and book chapters on the subject are, to date, the most comprehensive sources for scholars of early artistic Symbolism (John Bowlt, ‘The “Blue Rose” movement and Russian symbolist painting’, PhD thesis, University of St Andrews, 1972, https://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/handle/10023/3703; John Bowlt, ‘Russian Symbolism and the “Blue Rose” Movement’, The Slavonic and East European Review, 51, 123 (April 1973), 161–81. Bowlt has written extensively on mid to late Symbolism, too, in sources too numerous to list here. Also see: William Richardson, Zolotoe Runo and Russian Modernism: 1905–1910 (Ardis Publishers, 1986); A. A. Rusakova, Simvolizm v russkoi zhivopisi (Moscow: Belyi gorod, 2001). More recently, some attention has been paid to symbolism by Russian scholars; see, for example, this year’s exhibition Borisov-Musatov and the ‘Blue Rose’ Society at the State Russian Museum in St Petersburg (V. Kruglov, Borisov-Musatov and the ‘Blue Rose’ Society, ed. by Evgeniia Petrova (exh. cat., The State Russian Museum, St Petersburg: Palace Editions, 2017)).

37 Bowlt, ‘Esoteric Culture and Russian Society’, p. 173.

38 On Kandinsky and esotericism, see Rose-Carol Washton Long, ‘Occultism, Anarchism, and Abstraction: Kandinsky’s Art of the Future’, Art Journal, 46, 1 (Mysticism and Occultism in Modern Art) (Spring 1987), 38–45, https://doi.org/10.2307/776841

39 On Čiurlionis and Symbolism, see John Bowlt, The Silver Age: Russian Art of the Early Twentieth Century and the ‘World of Art’ Group (Oriental Research Partners: Newtonville, MA, 1982, second edition), pp. 78–79.

40 Jefferson J. A. Gatrall, ‘Introduction’, in Alter Icons: The Russian Icon and Modernity, ed. by Jefferson J. A. Gatrall and Douglas Greenfield (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2010), pp. 1–26 (p. 8).

41 Gatrall, ‘Introduction’, p. 7.

42 Ibid., p. 5.

43 The history of how the icon came to be regarded as art rather than artefact is a topic that has benefited from much discussion in recent years. See, for example, Shirley A. Glade, ‘A Heritage Discovered Anew: Russia’s Reevaluation of Pre-Petrine Icons in the Late Tsarist and Early Soviet Period’, Canadian-American Slavic Studies, 26 (1992) 145–95; V. N. Lazarev, ‘Otkrytie russkoi ikony i ee izuchenie’, Russkaia ikonopis′ — ot istorikov do nachala XVI veka (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1983), pp. 11–18. For an overview of this, see Gatrall, ‘Introduction’, pp. 4–9. ‘Old Russian’ is translated from the Russian word ‘drevnerusskii’ and refers to the period before the westernising reign of Peter the Great.

44 Rublev was the subject of Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1966 eponymous film.

45 Sarah Warren, Mikhail Larionov and the Cultural Politics of Late Imperial Russia (Farnham: Ashgate, 2013), pp. 111–32.

46 Ibid., p. 112.

47 Photograph in the public domain. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vassily_Kandinsky,_1913_-_Composition_7.jpg

48 Aleksandr Shevchenko, ‘Neo-primitivism: Its Theory, Its Potentials, Its Achievements’, in Russian Art of the Avant-Garde: Theory and Criticism 1902–1934, ed. by John E. Bowlt (London: Thames and Hudson, 1988), pp. 41–54 (p. 48).

49 Ibid., p. 46.

50 Camilla Gray, The Russian Experiment in Art 1863–1922 (Thames & Hudson: London, 1986), p. 134.

51 For the catalogues, see Vystavka ikonopisnykh podlinnikov i lubkov, organizovannaia M. F. Larionovym (The Exhibition of Icon Patterns and Lubki, Organised by M. F. Larionov) (exh. cat., Moscow Art Salon, Bol’shaia Dmitrovka, Moscow, 1913); Mishen′ (Target) (exh. cat., Moscow Art Salon, Moscow, 1913).

52 Boris Anrep, ‘Apropos of an Exhibition in London with Participation from Russian Artists’, in Russian and Soviet Views of Modern Western Art: 1890s to Mid-1930s, ed. by Ilia Dorontchenkov, trans. by Charles Rougle (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2009), pp. 106–08 (p. 107).

53 Quoted in Bowlt, ‘Orthodoxy and the Avant-Garde’, p. 148. For more on the visit, see Alison Hilton, ‘Matisse in Moscow’, Art Journal, 29, 2 (1969–70), 166–74, https://doi.org/10.2307/775225; Iu. A. Rusakov, ‘Matisse in Russia in the Autumn of 1911’, trans. by John E. Bowlt, The Burlington Magazine, 117 (May 1975), 284–91.

54 Avant-garde artists who wrote on icons include: Shevchenko, ‘Neo-primitivism’ and A. Grishchenko, Voprosy zhivopisi. Vypusk 3-i. Russkaia ikona kak iskusstvo zhivopisi (Moscow: Izdanie Avtora, 1917).

55 See, for example: Josephine Karg, ‘The Role of Russian Symbolist Painting for Modernity: Mikhail Vrubel’s Reduced Forms’, in The Symbolist Roots of Modern Art, ed. by Michelle Facos and Thor J. Mednick (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015), pp. 49–57; Josephine Karg, Der Symbolist Michail Vrubel′: Seine Malerei im Kontext der russischen Philosophie und Ästhetik um 1900 (Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag, 2011).

56 Gatrall, ‘Introduction’, p. 3.

57 Christina Lodder, ‘Malevich as Exhibition Maker’ in Malevich (exh. cat., London, Tate Modern, 2014), pp. 94–99 (p. 95). Also see: Evgeniia Petrova, ‘Malevich’s Suprematism and Religion’, in Kazimir Malevich: Suprematism, ed. by Matthew Drutt (New York, Guggenheim Museum, 2003), pp. 88–95; Mark C. Taylor, Disfiguring: Art, Architecture, Religion (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1992), pp. 79–84.

59 Ibid.

61 Rebecca Beasley, ‘Vortorussophilia’, in Vorticism: New Perspectives, ed. by Mark Antliff and Scott W. Klein (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 33–50 (p. 33), https://global.oup.com/academic/product/vorticism-9780199937660

64 Natalia Murray, The Unsung Hero of the Russian Avant-Garde: The Life and Times of Nikolay Punin (Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 2012).