4. Kazimir Malevich, Symbolism, and Ecclesiastic Orthodoxy

© 2017 Myroslava M. Mudrak, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0115.04

The abstract, non-objective Suprematist paintings of Kazimir Malevich serve as prime examples of spirituality in Russian modernist art. There is no greater testament to this fact than the symbolic placement of Black Square (fig. 5.2) at the launch of Suprematism at the 0.10 Exhibition in 1915 at the Dobychina Gallery in Petrograd (fig. 5.3). Malevich positioned the painting in the corner of one of the rooms of the gallery, close to the ceiling, deliberately emulating the common practice among the Orthodox faithful to place family icons, often festooned with hand-embroidered towels, in the revered ‘beautiful corner’ (krasnyi ugol) of their home. It would seem that Malevich’s dramatic (and symbolic) gesture flowed logically from his brush with Neoprimivitism — a movement that took inspiration from peasant life, which the artist observed keenly, including the peasantry’s outward expressions of faith. As a paradigm of the essentialised image, the icon, no doubt, lay at the core of Suprematism.

Yet Malevich’s understanding of the icon would signal an artistic trajectory that predated Neoprimivitism and went beyond the mere appropriation of its pictorial mechanisms. Unlike fellow Neoprimivitists Natalia Goncharova and Vladimir Tatlin, who adopted the icon’s linearity, pliated geometric forms, and rhythmic values, and interpreted them to purely formalist ends, Malevich set out to establish a higher purpose for his painting that occasioned spiritual engagement of the kind rooted in his first exposure to Symbolism. The main thesis of this chapter, therefore, is that Malevich’s exploration of the supreme by means of simple forms rendered on a flat surface (like the image of a black square on a white background) originated during this earlier period when Malevich and the Symbolists favoured fresco. By contrast, the Neoprimivitists’ preoccupation with the icon would only come into prominence several years later with the flurry of the rediscovery of icons following their cleaning and exhibition in the early 1910s.1

The fresco medium, taken up as a new consideration for Malevich, brought together two important artistic sources for formal experimentation, while tapping into the spiritual in art. The ecclesiastical mural painting tradition of Eastern Orthodoxy, especially scenes depicting the congregations of saints and angels seated compactly on the walls of Russo-Byzantine churches, meshed, in Malevich’s approach, with prime examples of contemporary Symbolist mural painting. Having been exposed to contemporary French painting in the collections of Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov, where the latter had commissioned Maurice Denis to install a cycle of Symbolist murals on The Story of Psyche in 1908–09, as well as through local publications, particularly the Russian Symbolist journal, The Golden Fleece (Zolotoe runo), Malevich also moved closer to a studied recognition of the compressed spaces of Cézanne and the solid swathes of Matisse’s colour. In his fresco designs he also followed these artists’ preoccupation with the subject-matter of multiple nudes congregated in a forest setting. Primarily, Malevich’s approach to art was influenced by the way that the Byzantine sacred tradition was held sacrosanct by the peasants, among whom he lived and whose way of life he revered. In part, this may have been motivated by Malevich’s own personal struggle with his Roman Catholic roots and the conflicts with his Polish aristocratic heritage.2

It can be argued that the visual culture of the Orthodox tradition shaped Malevich’s perception of art as a moral imperative. The example of wall paintings in the old churches of Kyiv and the late nineteenth-century restoration of their ancient frescoes drove home the social exigencies of monumental art, building a community of spectators, reinforcing shared values and a collective engagement with the images portrayed. As an unframed tableau exposing a narrative drama before the spectator, mural design blurred the boundaries between the pedestrian and the transcendent. The artist’s own psyche seemed to occupy the interstitial space between two realms, the physical and the ethereal, as it gently coaxed the spectator to participate in the revelation of the scenes depicted. Following in the steps of Symbolist painter Mikhail Vrubel, who preserved the emotional fervour and spiritual expression of ancient fresco, Malevich began to value mural painting as the medium of community.3 Indeed, when Vrubel produced his unprecedented interpretation of the Pentecost in the choir of the twelfth-century church of the St Cyril monastery in Kyiv in 1884, he privileged the ancient and ecclesiastical medium of fresco to serve as a platform not only for his own personal spiritual expression, but for an engagement with the beholder.4

Vrubel belonged to the era of Symbolist painters who sought to preserve for modernity the merits of an essentialised image imbued with a sacred ideal and spirituality. As a younger artist of that generation, Malevich longed to discover this link within his own art and turned to Symbolism for inspiration. The Symbolists aspired towards an ideational art that demanded strict discipline over the pictorial elements, most particularly line and colour. While maintaining an active link with the external forces of modernity — its urbanity, cosmopolitanism, and heightened secularism — the French Nabis, for instance, turned to interior scenes of psychological quiescence, and some, particularly Maurice Denis and Paul Sérusier, sought reconciliation of the sacred and profane in imagery modelled on the ancient practice of fresco painting. For western Symbolists like Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, fresco gave permanence to lofty notions of spiritual and secular cohesiveness, best exemplified by the St Genevieve cycle in Paris, a tendentious Republican commission that graced the Panthéon monument. The politicising agency of Puvis de Chavannes’s cryptic renderings of a hermetic world carried as much spiritual weight as the monolithically fluid unity of the choir of disciples of Vrubel’s fresco in St Cyril’s.

Once Malevich came to Moscow to pursue his art studies, he fully embraced the existentialist uneasiness addressed by the Symbolists. Russian Symbolism, in particular, reflected the temperament of fin-de-siècle anxieties by utilising diverse modes of expression: from Ivan Bilibin’s illustrations of supernatural figures of old Russian folk tales to Alexandre Benois’s nostalgic references to the ultimate social cohesiveness of the courts of Louis XIV and Peter the Great, the works of the ‘World of Art’ (Mir iskusstva) group — formed by Sergei Diaghilev in 1898 — embodied this plurality. Under the banner of the World of Art, artists diversified their approaches to metachronistic subjects, as in, for example, the paintings of Konstantin Somov and the paragonic motifs of Mikalojus Čiurlionis. In so doing, they expanded the thematic and stylistic bounds of Russian Symbolism from the affected to the theurgic, and gave breadth and depth to Symbolism’s universally redemptive message. When Viktor Borisov-Musatov synthesised the evocative pastel-tinted classical worlds of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, the linear decorativism of Denis, and the introspective intimate imagery of the Nabis, his work came to epitomise the soulful wholesomeness of Orthodox spirituality.

Malevich’s arrival in Moscow in 1904 coincided with the completion of a fresco mural project commissioned and designed by Borisov-Musatov for a church in the artist’s native Saratov. Under the master’s supervision, it was executed by Pavel Kuznetsov, Borisov-Musatov’s most renowned follower and key member of a group that would be known as the Blue Rose (Golubaia roza).5 Their signature style was marked by a reductive palette of blue hues and pastel tones applied in thin tracings on their canvases. Imitating the lime plaster walls of fresco that absorb pigment and leave only wispy traces of brushwork, they dissolved their forms into diaphanous scrims that suggest the silhouettes of vaguely defined figures, usually female in gender.

By 1906, when Borisov-Musatov’s designs for woven tapestry hangings were shown posthumously in a solo exhibition alongside the last exhibition of the World of Art, a bona fide, though short-lived, Symbolist movement in Moscow had reached its apogee.6 Focusing primarily on pictorial themes of females in secret, private worlds of ritual and initiation, most of Borisov-Musatov’s sixty-five pieces on display were studies prepared for gobelins intended for the walls of homes of the bourgeoisie. The artist’s signature retrospectivism, characterised by enigmatic dreamy maidens walking through lush emerald grounds of abandoned country estates, delves into a psychological realm of feminine grace and mysterious ritual that links his art to a retrospective period that would seem to have very little to do with the immediacy of Malevich’s visceral experience of peasant life in Ukraine.7

Yet, under the influence of Borisov-Musatov and the Blue Rose, Malevich made a dramatic shift in his choice of subject and painting materials. Substituting tempera for oil paint and moving away from an Impressionist spectrum to a diluted, monochromatic, and flatly-applied palette, Malevich produced a handful of anomalous paintings between 1907 and 1908 that have received little scholarly attention, mostly because they seem incongruous with his oeuvre and have never before been considered as part of his trajectory toward non-objective painting. This somewhat disconsonant group of works from Malevich’s Symbolist period establishes a point of departure in his art that will move him from positivism to the abstract precisely because of its inherent spiritual overtones. It was during his time in Moscow that Malevich abandoned the prosaic subjects and style of Post-Impressionism and instead turned his attention to the synthesising imagery of both western and Russian Symbolism, the latter emerging out of the revivalist impetus of neo-nationalism and its reinvestment in folk values and spiritual mores. In particular, five paintings of this period, untitled, but designated variously by the artist as ‘fresco designs’, form a cohesive corpus both formally and thematically that speaks of a tectonic shift in Malevich’s relationship to his art. They mark the first step towards the artist’s self-conscious identification with a sense of mission and his calling as an artist.

By the time of the seminal Blue Rose exhibition, which opened on 18 March and ran until 29 April 1907, Malevich was already transitioning to a new approach in painting beyond the pseudo-pointillist technique, which he had pursued since 1904, to embrace a Symbolist mode of expression. He longed to be included in the historic Moscow show, but his reputed Impressionism, exemplified by paintings such as Landscape with Yellow House (1906–07, State Russian Museum, St Petersburg), could hardly correspond to the contemplative, subjective worlds invoked by the Blue Rose. He was not a participant in the exhibition that, tellingly, included the work of Vrubel. The decision on the part of the Blue Rose painters not to include Malevich essentially relegated the newly-minted Symbolist to the fringe of the movement, raising the question of his true status within the novel and relatively short-lived group. This invites us to consider Malevich’s chronological development as a painter, particularly the nebulous circumstances that propelled Malevich to turn to fresco design in the beginning. There is clear evidence of a shift in the artist’s interests during his time at the Rerberg School in Moscow, where Malevich sought formal training in 1906. Here he began to lay the foundation for an approach that would reach ultimate expression in his mystical cruciform compositions of later years. This would be achieved by an increasing compression of the picture space, approaching the flatness of mural painting; such experiments would also serve as an exploratory counterpoint to the Impressionist-inspired fragmented and stippled strokes and reductive colour of his early period.

The unresolved issue is whether the anomalous works Malevich began to produce at this time were really intended as entries for the Blue Rose exhibition in early 1907. Or, more likely, are they the product of his reaction and response to the exhibition from which he was excluded? To be sure, Malevich would have been keen to be represented in the Blue Rose exhibition, for it would have launched him from obscurity to the kind of recognition that would validate his chosen profession as a painter. It is tempting to draw a connection between Malevich’s fresco designs and the exhibition, although there is no tangible evidence that allows us to assess whether these works were a direct result of the Blue Rose event. Even more perplexing is his timeline for producing them. However one wishes to speculate, the series of designs complements the character and manner, and, to some degree, even the subject of the Blue Rose works.

We can be assured, however, that Malevich visited the Blue Rose exhibition and was enthralled with the installation, as evidenced by the exuberant tone in his reminiscences.8 Even though this was still early in his career, he recognised that it was like no other exhibition seen before and was commanding in its creation of mood through colour. Reviewing the exhibition in The Golden Fleece, Sergei Makovsky described the experience of the paintings as being “like prayers” in “a chapel”.9 One of the lingering effects of the viewing experience, as Malevich later remembered it in his autobiographical memoir, was that the space was redolent with the strong fragrance of spring flowers.10 The sweet scent of daffodils, lilies, and hyacinths wafting through the space and the wispy thin strains of a string quartet filling the atmosphere were likened to the sounds and smells of a liturgical event, be it the polyphonic chanting or the smoky incense wafting throughout the church. Malevich described the overall effect as akin to a “feast day […] a celebration — both a dawning, and yet, at the same time, eventide”. In his memoirs, the artist described the show as aromatic visuality: “patches of various forms, which gave off the ‘smell’ of the colour”.11 This observation coincided with Malevich’s growing appreciation for the synaesthetic properties of ecclesiastical rituals and church art shared by a congregation in unison.

That the events leading up to Malevich’s fresco designs occurred in springtime during the solemn Lenten and the festal Paschal seasons of the liturgical calendar suggests that his imagery, though not explicitly religious, was nonetheless seeded by eastern Christianity. Struggling with, and ultimately unable to accede to, the self-indulgent, individualistic expression of Impressionism and its variants, his experience of the lifestyle and values of the simple peasantry made the quest toward a higher artistic purpose a logical one. The full recognition of his indebtedness to the devoutly religious and simple lifestyle of village folk would begin to emerge a few short years later in the aesthetic of Neoprimivitism.

Malevich’s early cycle of fresco designs almost certainly served as a portent of a lifelong commitment to an art that would galvanise community — the source of Malevich’s spirituality. This is not to claim that he was a religious person, or that he was intending to bring religion into his art; rather that the example of the faithful — those who are committed to a redemptive belief in a better, more perfect form of existence — appealed to Malevich, who sought these supreme principles through the agency of painting. Because his art stemmed from a self-awareness that anticipated a lifetime of artistic commitment to this higher cause, the fresco designs that he made in 1907–08 (sometimes referred to as the ‘Yellow Series’), though engaging in the hedonistic and transcendent themes of Symbolism, are also prescient of the utopianism that will mark Malevich’s art in the years to come.

4.1 Kazimir Malevich, Untitled. Study for a Fresco Painting, 1907. Tempera/oil? on cardboard. 69.3 x 71.5 cm. State Russian Museum, St Petersburg. Photograph © State Russian Museum, all rights reserved.

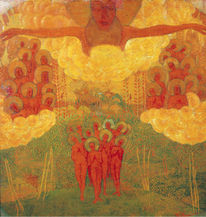

4.2 Kazimir Malevich, Study for a Fresco Painting. The Triumph of Heaven, from the so-called ‘Yellow Series’, 1907. Tempera on cardboard. 70 x 72.5 cm. State Russian Museum, St Petersburg. Photograph © State Russian Museum, all rights reserved.

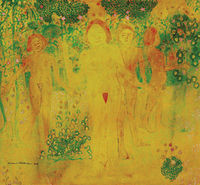

One of Malevich’s paintings of this period, Untitled (1907, State Russian Museum, St Petersburg) (fig. 4.1) — the fourth of a series of sketches for fresco painting indicated by a notation by the artist on the back of the work — shows a mysterious group of seven slender, feminine figures occupying a dense copse of tall and thin willowy trees that frame a verdant clearing in the foreground.12 At the heart of the composition are shrub-like forms that support a limp body stretched over the top of the bushes. This recumbent figure commands a prayerful stance from the surrounding figures, suggesting a scene of bereavement. Some of the mourners cross their hands over their chests, others place their palms together, still others stand with arms to their sides in the Orthodox gesture of prayer. In another work, posthumously titled The Triumph of the Heavens (1907, State Russian Museum) (fig. 4.2), an androgynous figure is shown with arms outstretched and eyes closed, a halo around its head, and a cowl around the neck, emerging from a cloud beyond the horizon. It hovers as if delivered from the firmament above and gently sweeps over the landscape, framing with extended arms three groups of eleven haloed figures, also of unspecified gender, which are accommodated by the span of its gliding reach. Two of the groups, relegated in a symmetrical composition to the sides of the painting, are cradled by a cloud. The third and central group of figures walks with bare feet firmly on the lush grassy ground. Both paintings appear to represent some kind of mystical event known only to the initiated.

Contemporaneous with the mostly gauzy paintings of the sixteen artists shown at the Blue Rose exhibition, which depicted spectral, pubescent females and aqueous embryos set among breezy fountains, wispy willows, and succulent foliage, Malevich here ascribed to the idealisation of woman championed by European Symbolism. These ineffable symbols of divine grace and eternal love were rendered by depleted blues and azure tones — a range of “illusive distances of cobalt and emerald” as described by Denis, who spoke of painting as “a flat surface covered with colours assembled in a certain order”.13 Malevich’s own fluidly fading masses of contoured, somnolent bodies and the mysterious contexts in which they move suggest a strong connection to the work of the Blue Rose painters, who remained active in Moscow until 1908. Yet Malevich’s palette deviates from the filmy blue-greys and dissolving cerulean atmospheres of the works of his contemporaries. Rather, Malevich’s transparent yellows and daubs of green give texture to these seemingly reclusive and isolated settings. The speckled treatment of the paint emphasises the graphically mottled light peeking through dense vegetation; the early-morning radiance illuminates the foliage, making it as palpable as the twinkling dew that settles like jewels upon the edges of shrubs and individual leaves. Indeed, Malevich’s new approach was reflected in the very words used by Makovsky two years earlier when describing Kuznetsov’s and Sergei Sudeikin’s paintings at the Twelfth Exhibition of the Moscow Association of Artists in 1905 as “drowsy tranquillity and silence of daybreak”.14

Not only are Malevich’s designs confluent with the Symbolist context of Borisov-Musatov’s followers, they are consonant with the philosophical echoes of writers such as Viacheslav Ivanov and others, who harked back to the German Romantic notion of Bildung — the concept of ‘reflective judgment’ as the primary function of art as opposed to its mechanical processes. This self-reflexive consideration of art makes room for the examination of aspects of being and belonging, which, as will be argued, began to surface in Malevich’s art in his 1907 fresco designs. Malevich’s questioning and self-projection within his art would become a motivational force that, though originating in these works, would weave throughout the various phases of his subsequent development and culminate in unique achievements: Suprematism, UNOVIS (Utverditeli novogo iskusstva (‘Champions of the New Art’)), and Supranaturalism, the last phase of Malevich’s life as a painter, when he returned to a figurative art form, monumentalising the humble peasantry in stark rural environments. Whether readily cognised or not in the early phases of his art, this force formed the basis for a lifelong endeavour, guided by a philosophy that may have begun in mystification, but resulted, at least for him, in pure revelation. As a result Malevich developed a conception of art that, in its aspirational qualities, went beyond individual subjectivity to a humanistic universalism. Through it all, he harked back, as did the Symbolists before him, to the unifying impulse of the Church as the agent of Orthodox community-building.

References to the self-searching that defines Orthodox Easter rituals seep into Malevich’s frescoes, just as Catholicism had defined the art of Denis almost a decade earlier.15 Indeed, Malevich’s eerie, transparent palette, the paintings’ subdued tones and shock of orange-red, and the calligraphic fluidity throughout the work coincide with the mysterious and unnatural palette of the quintessential turn-of-the-century French Symbolist. By 1900, Denis had achieved a true balance between the ethereal and material, the oneiric and the arcadian, achieving a harmony between line and colour that could be tapped for presenting his spiritual and specifically Catholic subject matter. Like Denis’s Catholic imagery, Malevich’s work is imbued with a profession of faith, it seems, but of a secular order. Retreating into themes of ritual and mystery and associating them with Orthodox liturgical practice, Malevich deviates from the oneiric to embrace an Orthodox sensibility, setting out on an aesthetic pathway rooted not in the intellect, but in the senses, which the example of Eastern Orthodoxy offered him.

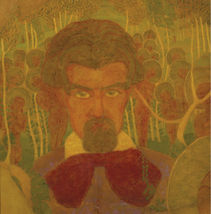

4.3 Kazimir Malevich, Self-Portrait, 1907. Inscribed on reverse in Russian, ‘Study for a fresco painting’. Tempera on cardboard, 69.3 x 70 cm. State Russian Museum, St Petersburg. Photograph © State Russian Museum, all rights reserved.

This is borne out by Malevich’s Self-Portrait (1907, State Russian Museum) (fig. 4.3), which was also included as part of the fresco design cycle. Here, the somewhat introspective young Malevich, shown with steely eyes, dishevelled hair, beard, and moustache, entreats your gaze, as if the artist has taken a moment to retreat from the surrounding ceremony in order to have you look at him closely, and for him to observe you penetratingly. Such visual reciprocity is sustained throughout the image: the painter is shown simultaneously as both actor and surveillant — at once an active player and a witness to the mysterious events taking place. Meanwhile, a crowd of haloed figures surrounds and engulfs him.

The artist’s relationship to religious community as a pathway of self-exploration had been addressed pictorially by Paul Gauguin in the 1880s. Like Malevich, who includes himself within the context of some kind of ceremonial observance, Gauguin’s Self-Portrait with ‘The Yellow Christ’ (1890, Musée d’Orsay, Paris) shows a questioning artist against the backdrop of one of his most commanding paintings, the crucified Christ rendered in acerbic sulphurous yellows. Gauguin portrays himself as complicit in Christ’s suffering (e.g., Christ in the Garden of Olives (1889, Norton Museum of Art, Florida) and Jug in the Form of a Head. Self-Portrait (1889, Kunstindustrimuseet, Copenhagen)) and yet at some distance from it. Offering a glimpse into his state of mind, so too the young Malevich, shown frontally and foregrounded in a bust-view, projects a defiant-looking demeanour.

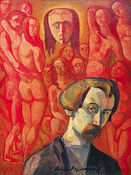

4.4 Émile Bernard, Symbolic Self-Portrait (also known as Vision), 1891. Oil on canvas, 81 x 60.5 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris.16

Not unlike Gauguin’s Christ in the Garden of Olives, which includes the artist’s self-portrait in the guise of a red-haired Christ, Malevich’s Self-Portrait renders his own position singularly ambiguous, negotiating the tension between inclusiveness and external witnessing. As in Gauguin’s Vision After the Sermon (Jacob Wrestling the Angel) (1888, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh), the artist assumes a notable place among a company of pious believers, yet he remains a dubiously assenting figure. Though surrounded by the saintly elect, Malevich’s form is prominently singled out. In the overall yellowish tones of the work and the crowd of nudes it recalls Émile Bernard’s Symbolic Self-Portrait (also known as Vision) (fig. 4.4).

Malevich’s adoption of Christian themes in the manner of the French Symbolists is affirmed by his allusion to Bernard’s and Gauguin’s inclusion of the Christ’s head crowned with thorns. Frontal and foregrounded, with a slight bend of the head (as in Bernard’s self-portrait), the artist’s visage engages directly with the beholder. Within the context of liturgical practice and the iconographic tradition of Orthodoxy, particularly the ubiquitous image of the Pantocrator or Christ the Priest, the artist’s identity here coalesces with the role of acolyte. As in the other fresco paintings, Malevich creates an idyllic, pastoral setting occupied by the pietistic haloed figures. Shown among nudes, which in Bernard’s work include Adam and Eve, the figure of Malevich assumes an important responsibility born of an inner necessity to the lay community to which he belongs.

Without an aureole, however, he is also not fully initiated into their community and appears somewhat incongruous by his dress. Substituting the avocation of the artist for that of the priest, Malevich dons the vestments of his profession: a painter’s smock tied at the neck into a thick floppy bow. Beneath the knot the painter identifies himself with the Cyrillic letters of his name, K-M-A-L, appropriately truncated at the point at which, at least in Polish or Ukrainian, he would call himself a “maliarz” or “maliar” — i.e., a painter, in the respective languages. Thus, like Gauguin, the sideline observer of a Breton religious observance (e.g., in Vision after the Sermon), Malevich is an intimate witness to a religious experience, but, at the same time, he is not fully incorporated within it. Both artists are hyper-conscious of their being both insiders and outsiders to the events taking place around them, and both, it seems, are at some kind of threshold of fuller understanding.17 Malevich returns to this theme several years later. In Self-Portrait Against a Background of Red Bathers (1910–11, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow), Malevich shows a distinctly carnal male sexual organ seen along the right side of the artist’s head, perhaps a reference to himself as an aroused Adam in the Garden of Eden, but again, unfulfilled, pushed to the margins, and left separated from the rest of the figures.

That Malevich’s first Self-Portrait dates to his Symbolist period crystallises the notion that the artist saw himself called to a higher vocation, though still questioning his way. The portrait takes on the characteristics of a manifesto, addressing issues of belonging, induction, and habituation. As a manifesto, moreover, it reveals an opposing and definitive stance against the increasingly decadent and morbid turn of Blue Rose Symbolism. The brighter palette, the communion of figures, and a strong sense of a spiritual coalition and exclusivity suggest a direction of purpose and determination to reach specific goals. Thus, by contrast with the Blue Rose artists’ despair and a growing uneasy disillusionment with the hopeless status of society, reinforced by Kuznetsov’s images of unborn babies and reclusive islands of the consumptives, Malevich’s art ushers in a new era of expectation, purposeful orientation, and hope.18

It is noteworthy that the Blue Rose exhibition took place precisely during the time of Orthodox Lenten preparations for the liturgical Paschal feast — the Resurrection — essentially the solemn period leading up to Easter. In keeping with this ecclesiastical period of reflection, self-evaluation, and soul-searching, church rituals are intensified for the Orthodox, challenging the faithful to become hyper-aware of their earthly conduct, and to take stock of their spiritual state. In keeping with Eastern Christianity’s emphasis on a heightened detachment from the physical and material world, the eschatological nature of the Lenten services keep the faithful focused on a time to come by means of a pensive, introspective observance of church rituals.

In the Byzantine Rite, the Typikon — including Vespers, Matins, the Office of the Presanctified Liturgy, and the series of All-Souls services to remember deceased ancestors — embodies tradition carried out through generations of community prayer. It imbues the canonic springtime observances with a totalising immersion into the realm of the spiritual. For example, the psalmody of the liturgies — the Triodion (Lenten and Paschal hymns), in addition to the prescribed processions and entrances, engages the laity in communion with the clergy who circumambulate the interior of the church, sanctifying everyone with countless blessings and incensings. Malevich would capture viscerally this instance of physical communal worship in his Neoprimivitist Peasant Women in Church (1911–12, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam). Here he shows the devout women affirming their baptismal initiation into the community by making of the sign of the cross (in the Eastern style with three fingers together, ending up at the left shoulder) — a symbolic gesture of accountability that is accompanied by singing (three times) the ancient liturgical hymn that repeats the words, “all you, who have been baptised into Christ, cloak yourself in Christ”.19 Malevich’s devout peasant women display the meaning of the ‘thrice-holy hymn’ (the Trisagion) on their very bodies. Their prayerful gesture of humble ‘cloaking’ (metanie) in the mantle of their faith visibly and openly confirms their belief in, and expectation of, the promise of the universal Kingdom of God.

Malevich’s monumental peasant forms occupy every inch of his picture space in the same way that their devout spirit fills the church, especially on Easter Sunday. Moreover, the entire act of worship is conducted in an atmosphere that heightens the senses. The olfactory nerves, absorbing the incense swelling the interior space of the church, participate in a totalising sensorial experience, not unlike Malevich’s description of the Blue Rose exhibition of 1907. In addition to the tactile gesture of blessing (and ‘cloaking’) oneself while bowing reverently, as shown in Peasant Women in Church, one can assume that the audial sense is stirred by the polyphonic responses of the laity to the chanting of the clergy during the Liturgy, while the flicker of candles and the light passing over wall murals and icons that surround and engulf the faithful give optical instantiation to the Logos — the word of God. Perhaps it is because of this liturgical context that the golden tints of Malevich’s fresco series, steeped in the sensuous experience of the Liturgy, deviate from the concordant scale of blues and dark greys of his Blue Rose contemporaries. Malevich’s palette gives full expression to a site of worship illuminated by divine light. Indeed, as the first dawning light brightens the church interior on Easter morning, the Orthodox faithful sing of celebrating “the annihilation of death, the destruction of Hades, and the beginning of another life which is eternal” (Ode 7, Canon of the Pascha). The church, as an extension of paradise, represents a very complex experience of the spiritual in the anticipation, expectation, and realisation of Byzantine anamnesis — the mystery of the Eucharist, the death, and the resurrection of Jesus Christ. Man, made in His supreme likeness, shares in every aspect of this jubilant mystery, if he is willing to participate in the spiritual journey. The church is there to set the guideposts. Throughout the liturgical year, the faithful are reminded of prototypic milestones on their spiritual journey toward revelation and redemption. The synthesising experience of Christ’s death, burial, resurrection, ascension, His glory in Heaven, and His Second Coming are embodied, for instance, in the example of the profligate, yet contrite, Mary Magdalene, who became closest to Christ at the time of His death, and Lazarus, raised from the dead as a foreshadowing of Christ’s own burial and miraculous resurrection.

4.5 Kazimir Malevich, Collecting Flowers (also referred to as Secret of Temptation), from the so-called ‘Yellow Series’, 1908. Watercolour, gouache, and crayon on cardboard, 23.5 cm. x 25.5 cm. Gmurzynska Collection, Zug, Switzerland.20

One might contend that the two subjects of Mary Magdalene and Lazarus, used as didactic paradigms for spiritual renewal, are referenced obliquely in two of Malevich’s fresco designs. His untitled study for a fresco painting discussed at the beginning of this chapter (fig. 4.1) can now be read within the context of Paschal iconography. It shows a supine figure draped over a raised bed of foliage, an allusion to some kind of sacrificial act, perhaps a liturgical reference to the Lamb of God (or the Raising of Lazarus). In the case of the lamentation over Christ’s body, a male bearded figure to the left and a female with long hair in the middle ground are standing close, and leaning toward the head of the expired body; these figures likely correspond (iconographically) to Mary and Joseph. By the same token, if the scene depicts Lazarus’s resurrection from the dead, then the two females might refer also to Mary and Martha, and the bearded figure to Christ Himself. Another of Malevich’s fresco designs, Collecting Flowers (also referred to as Secret of Temptation) (1908, Gmurzynska Collection, Zug, Switzerland) (fig. 4.5), depicting four auburn-haired females who emerge like nymphs from the idyllic forest, comes closest to affirming such an interpretation. While this image identifies closely with the ‘feminine’ subjects of Denis and Borisov-Musatov, invoking a mysterious, all-female, expression of divine love, Malevich’s exploration points more directly to the three Marys and the repentant Magdalene, who boldly ventured out to the sepulchre to see the dead Christ at dawn.

The sensual figure of Mary Magdalene comes poignantly to mind in yet another of Malevich’s images in this fresco design cycle, commonly called Prayer or Melancholia (1907, State Russian Museum) (fig. 4.6). In composition and mood, as well as in the choice of palette, this image explicitly echoes The Offertory at Calvary painted by Denis in around 1890.21 Yet, from an Eastern Christian liturgical standpoint, the singular figure seated in a lush grove offers a visual correspondence to the words of the Paschal Stichera sung in the Hypakoje of the Byzantine Resurrection Matins, conflating the figure of Mary Magdalene with that of the Angel who is encountered by the three Marys at Christ’s empty tomb: “The women with Mary, before the dawn, found the stone rolled away from the tomb, and they heard the Angel say: ‘Why do you seek among the dead, as a mortal, the One who abides in everlasting light?’” As the symbolism embodied in this liturgical song reveals, the barren rock is transformed into a throne of enlightenment: “Bearing torches let us meet the bridegroom, Christ, as He comes forth from His tomb; and let us greet with joyful song, the saving Pasch of God” (Hirmos, Ode 5. Resurrection Matins).

The jubilant tone of this Paschal Ode is translated into Malevich’s visually evocative painting arbitrarily titled Collecting Flowers, cited above. Again, a dominant yellow palette reinforces the resurrection theme, suggesting the renewal of humanity enlightened by the example of Christ’s resurrection “bestowing upon the world a new life and a new light, brighter than the sun” (Byzantine Prayer for the New Light). Invoking the Genesis story, the prescribed liturgical office thus celebrates the first day of the new Creation as its day of worship. In keeping with this trope, Malevich’s intended frescoes give rise to a realisation that the first fruits of the Kingdom already exist on the earth. Like St Maximus the Confessor and St Sophronius, for whom the Church was the site of the intersection of the spiritual and visible worlds (i.e., the image of that which we perceive spiritually and that which we perceive with our senses), so Malevich taps into the convocative nature of the church assembly to better create art that might be integrated into, if not cultivate, a shared belief system. Indeed, the ancient theologians and Church Fathers spoke of the church as “the heavens on earth, where God, who is higher than the heavens, lives” (St Germanus), and where the “gifts of paradise” are housed, for the Church contains not just the tree of life, but life itself, acted out in the sacraments and communicated to the faithful (St Simeon of Thessalonika).22

4.6 Kazimir Malevich, Prayer (also known as Meditation), 1907. Tempera on wood. 70 x 74.8 cm. State Russian Museum, St Petersburg. Photograph © State Russian Museum, all rights reserved.

The convening function of the Church and the sensorial experience of the Byzantine liturgy, along with the convictions of the faithful and their acts of witnessing, fold into a transcendent experience of expectation, hope, and fulfillment that Malevich seems to have absorbed and adopted as guiding principles for his own, albeit fully secular art. It was this higher purpose that he carried into Suprematism and Supranaturalism, creating, in the first instance, a temple-like environment in a gallery space at the Last Futurist Exhibition of Painting 0.10 (‘Zero-Ten’) in 1915, and later in the 1920s and early 1930s, rendering people as timeless, mostly faceless beings, traversing visceral, deeply furrowed farm fields. Their spectre-like forms intimate, nonetheless, that they inhabit not the earthly, but another atemporal and ethereal realm. The example of the inherently cosmic nature of liturgical synaxis — an image of the entire created, but transfigured, world — functions as an analogue to the revolutionary impetus of Malevich’s art.

Undeniably, Malevich’s early period showing a growing predilection for the oneiric themes of the Symbolists would seed and crystallise the spiritual dimensions of his later art. It is not known whether Malevich took up fresco design precisely around the time of the Blue Rose exhibition in deference to the preoccupations of these artists, who, in their interpretation of the feminine idea, had turned to themes of springtime rebirth, water festivals, and rituals of initiation and motherhood.23 In keeping with the themes of the Blue Rose, Malevich produced a painting titled Maternity (also known as Woman Giving Birth) (1906/1908, Tretyakov Gallery). A few years later, under the sway of the Neoprimivitist aesthetic, he returned to the subject in early 1910, painting the canvas entitled Motherhood/Abundance (1910, Khardzhiev-Chaga Cultural Foundation, Amsterdam (on deposit at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam)). A further rendition of this subject occurred in his Supranaturalist period in the pencil on paper drawing Maternity (c. 1930), showing a mother holding her dead, blackened child in her hands — a modern-day Pietà inspired by the ashen faces of starved peasants during collectivisation. As evidenced by the chronological range of these paintings, the exploration of the contemplative, theurgic impulse, first encountered by Malevich in the atmosphere surrounding the Blue Rose, defined the artist’s own introspective worldview, which he explored through painting.

Indeed, even after an illustrious and at once, notorious, period of abstraction during the 1910s, Malevich would return to figurative fresco painting in the latter part of the 1920s, fulfilling a fascination with the medium that he had first encountered in his childhood.24 Building on the initial example of the French and Russian Symbolists, he sought to create a visually holistic environment that was intended to transport the viewer to a higher consciousness — a goal that would become more apparent with the advent of Suprematism in 1915 and a brief preoccupation with fresco painting in the 1920s, a decade that witnessed a widespread revival of mural painting.25 In 1927, when Stalinist government pressures made life untenable for artists of the avant-garde, Malevich was given a reprieve from the oppressive atmosphere of Leningrad by an invitation from his Ukrainian friends to teach in his native Kyiv. There Malevich produced a fresco sketch for the Conference Hall of the All-Ukrainian Academy of Sciences (1930), which he rendered in pastel, gouache, and graphite pencil on paper, but never realised on site. Prominent in the design is an elongated large cross — a motif he began to incorporate into his new figurative art of Supranaturalism. Upon his return to Leningrad, Malevich would himself design two additional frescoes: a mural for the Leningrad Red Army Theatre, and a project for the House of the Soviets in Moscow.

Malevich’s reputation as a forward-looking abstract painter is rarely associated with the brief duration of Symbolism in Moscow. Yet, as a discrete body of early work linked directly to the esoteric themes, ephemeral style, and philosophical turn of Symbolism, his long unstudied fresco designs of 1907–08 appear to have been instrumental in shaping and supporting the futuristic drive of Russian modernism from the 1910s through the early 1930s. Through it all, Malevich’s aspirations as an artist paralleled the personal struggle of any individual committing to a higher calling. While still at the Rerberg School in Moscow, Malevich’s fellow artists had already pegged him as a somewhat charismatic and endearing — if eccentric — personality. As indicated by their friendly caricatures of Malevich, showing him with his bowl-cut hair (typical of ethnic Ukrainian villagers) and imbuing him with an ascetic look, they understood early on that, notwithstanding Malevich’s reserved, monkish appearance, he was intent upon some sort of a didactic mission, using art as his language. It is not surprising, therefore, that Malevich would become a mentor to a new generation of modernist painters in post-revolutionary Russia. Overcoming the self-doubt and uncertainty of the unknown (as expressed in his early portraits) was instrumental to Malevich’s self-appointed role as a visionary and ‘priest’ of art. The questioning demeanour in his Self-Portrait, which, it might be argued, is central to the fresco cycle, points to a degree of soul-searching to confirm his avocation as an artist, and also begins to reveal Malevich’s psychological state as he constantly reevaluates his status as a painter.

Malevich’s commitment to the missionary nature of his art would blossom after his Suprematist breakthrough: his monastic, introspective existence would be transformed and supplanted by revolutionary slogans such as ‘art into life’ or the process of ‘affirming the new in art’, culminating in the formation of UNOVIS in 1918 and securing a following thanks to his charismatic leadership. Just as the intensity of spiritual life can penetrate a whole mass of Orthodox believers united in the awareness that they form a single body within the hierarchy of the church, so Malevich’s affirmation of the new in art through UNOVIS represented a community of citizens invested in shaping a perfect society. The artist was fully cognizant of the theology of anamnesis, or mindfulness of the present moment, and the church’s systematic, congregational method of bringing man to a heightened spiritual awareness. Initiation was (and remains) critical to that process.

The spiritual underpinnings of the fresco project gave Malevich a firm starting point and a foundation for pursuing a more essentialised form — a nuanced, abstract language for expressing spirituality. Later, the motif of the black square, which initiated his singular journey toward the abstract, would signal the communal value of transcendence and become the ultimate symbol of inclusiveness. As a sign of their unity, UNOVIS inductees together with their leader Malevich, hypostatised in the role of priest, would sew little black squares on their sleeves as a mark of their ideological solidarity. It is noteworthy that the ceremonial vestments of the deacon and higher ranks of clergy within Eastern Orthodoxy include cuffs, called the Epimanikia, that are frequently embroidered with a cross. This reinforces the thesis that Malevich’s avocation paralleled the ecclesiastical patterns of Eastern Orthodox (Byzantine) worship, which he privileged as the belief system of the peasant masses. The tension between belonging and non-belonging, between a sense of inclusivity and exclusiveness, can be traced to a specific exploration of medium (fresco) and to a specific event (the Blue Rose exhibition) in the early years of Malevich’s Moscow experience.

The liturgical contemplation of the Second Coming and the world beyond the present serve as a paradigm of Malevich’s own aspirations in the aftermath of the Revolution of 1905, and again, after 1917.26 This is not to suggest, by any means, that Malevich ‘found religion’, or that, he, as a baptised Roman Catholic, sought conversion to Orthodoxy, nor, at least in the context of this analysis, that he was a religious artist or painted religious subjects. Yet the dogmatics of the Eastern Church lie at the very foundation of Malevich’s conviction that art must reveal a common belief about spiritual transcendence, redemption, and supreme perfection. Malevich’s Symbolist fresco project marks a singular point of departure in the artist’s quest for some kind of transcendent absolute — be it in abstract or figurative art. The mostly square format (about 70 x 70 cm.) and dimensions of the individual paintings foreshadow the square perimeters and iconic completeness of Malevich’s Suprematist works, while the use of simple card stock (as opposed to primed canvas) imbues his representations with a supra-temporal quality in the face of a larger, all-encompassing and permanent notion of ‘Truth’.

Executed in tempera and completed in the aftermath of the Revolution of 1905, the brightness and lightness of Malevich’s fresco studies suggests a renewal of his own belief in a better tomorrow rather than despair at the status quo. By returning to tempera and by contemplating a mural painting project without having an actual commission, Malevich’s actions suggest the necessity for him of tapping into the enduring material and spiritual traditions of ancient Orthodoxy to revive a shared belief system made accessible to all society. If one is willing to consider the frescoes as an analogue for Malevich’s new direction in his art, then this critical juncture can also be seen as a major shift from pure aesthetic concerns to issues of social import. That experience alone would launch Suprematism as a movement of transcendence, morphed into a utopian ideology. The redemptive note carried throughout Malevich’s fresco cycle of heathen imagery seems to embody the stance of the Orthodox Church that makes no distinction between theology and mysticism. Seen as the context for altering consciousness and providing for a change of attitude (metanoia) presented by the example of communal liturgical Paschal preparations, the Church offers an opportunity to recommit to a higher calling and redirect the mediocrity of one’s habituated lifestyle to take on a nobler existence. Such a change of attitude and understanding would be required of the Orthodox faithful in the period following the Revolution when religion was replaced by proletarian ideology.

As Malevich abandoned western Impressionism and began to deviate from the subjects of western painting, the Orthodox mindset became increasingly appealing to him, leading him and his contemporaries such as Goncharova to a closer exploration of the mores of the peasantry, including their devout lifestyles.27 Fully immersed in the discourse of Symbolism, Malevich’s art derived initial inspiration from the idyllic settings and environments of the art of Puvis de Chavannes and Denis; his Edenic depictions and thaumaturgical subjects share a special kinship with the art of Bernard and Sérusier, whose work Malevich also would have known.28 Moreover, channelling the moralising self-scrutiny and soul-searching of Gauguin’s deeply introspective Christological iconography, Malevich’s art directs the beholder towards a sublimated atmosphere of communal ritual for the initiated, depicted in these works in the way that a synaxis of saints might be portrayed in Russo-Byzantine church murals. The scene of the now lost fresco of the Apocalypse in the Moscow Church of the Annunciation in the Kremlin, painted by Theophanes the Greek, comes to mind, as does a whole corpus of similar images painted on the walls of Russo-Byzantine churches throughout the Eastern Christian world. At the time of Symbolism’s flowering, however, Malevich was already in search of a higher purpose for art and a more meaningful engagement with painting beyond formalist invention. As his resolute commitment to art grew stronger, his Symbolist project of fresco designs, which had focused on death and exalted rebirth, would translate into a symbolic expiration of figurative art, only to be supplanted by a resplendent and transcendent rebirth in abstraction. Suprematism, Malevich’s involvement with UNOVIS, and the launching of Supranaturalism bring to full circle the spirituality of his Symbolist period.

Malevich’s fresco designs of 1907 did not yet fully embrace what would in a few short years evolve into a Neoprimitivist aesthetic, which explored the prosaic scenes of Slavic agrarian lifestyle as well as their religious traditions, including the style of their church murals. The summoning agency of Byzantine liturgical practice and the dogmatics of the Eastern Church offered the possibility of turning away from western models and discovering indigenous traditions as the mainstay of a new local modernism. And yet, Malevich’s paintings of 1907 still remain rather anomalous in comprehensive studies of the artist and hardly receive attention as part of a consistent, totalising artistic trajectory.

1 There is much scholarship on the influence of Orthodox icons on the art of Malevich. The most systematic analyses of this borrowing can be found in Kazimir Malevich e le sacre icone russe: Avanguardia e tradizione, ed. by Giorgio Cortenova and Evgeniia Petrova (Verona: Palazzo Forti, 2000). For further contextualisation of the influence of the rediscovery of traditional icons on Russian modernism, see Chapter 5 of this volume.

2 Andréi Nakov places heavy emphasis on the psychological weight of Malevich’s ‘Polishness’. Malevich’s uncle, Lucjan Malewicz, a Catholic priest, was one of the leaders of the nationalist Polish insurrection against the Tsar in 1863, which accounts for the family’s ending up in Kursk to flee Russian chauvinist persecution. Insisting on the Polish spelling of his name (Malewicz), Nakov claims that “the provincial burden of a Catholic sexton’s ‘Polishness’ was a heavy one for the artist”, which imbued his art with “moral connotations” and “to a certain extent religious ones”. See Andréi Nakov, Malevich. Painting the Absolute. Vol. 1 (London: Lund Humphries, 2010), pp. 10 and 27.

3 See Maria Taroutina’s chapter in this volume and also Aline Isdebsky-Pritchard, The Art of Mikhail Vrubel (1856–1910) (Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1982), pp. 67–89, especially pp. 78–80.

4 While supervising students of the Kyiv Drawing School in the restoration of the existing twelfth-century frescoes of the monastery church, Vrubel’s novel approach produced unconventional (though never realised) scenes of the Lamentation for the church of St Vladimir in Kyiv. In addition to his unusual fresco of the Descent of the Holy Spirit, he executed a most enigmatic version of the Mourning at the Sepulchre — a theme that will become relevant later in this chapter. For more on the history of Vrubel’s work for the church of St Vladimir see Chapter 2 of this volume.

5 In around 1903, Kuznetsov, Petr Utkin (another Saratov artist), and several others keen on Borisov-Musatov’s art enrolled at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture.

6 An exhibition of modern Russian art under the name of ‘The World of Art’ was organised by Diaghilev at the Swedish Lutheran Church in St Petersburg, and opened on February 24, 1906; a related solo exhibition of the work of Borisov-Musatov was held separately. See Mir iskusstva: On the Centenary of the Exhibition of Russian and Finnish Artists, ed. by Evgeniia Petrova and trans. by Kenneth MacInnes (State Russian Museum, St Petersburg: Palace Editions, 1998), p. 244. A catalogue for the Borisov-Musatov exhibition has not been traced.

7 Notwithstanding his attachment to the peasantry, towards the end of the decade Malevich would turn his attention to the recreational themes depicting middle-class society in the way typified by Borisov-Musatov’s work. A good example of this interest is Malevich’s Rest. Society in Top Hats (1908). Watercolour and gouache on cardboard, 23.8 x 30.2 cm. State Russian Museum, St Petersburg.

8 Kazimir Malevich, Zametka ob arkhitektury (1924). See ‘A Note on Architecture’ (MS, private collection, St Petersburg), http://kazimirmalevich.ru/t5_1_5_13/

9 Sergei Makovskii, ‘Golubaia roza’, Zolotoe runo, 5 (1907), 25.

10 Malevich wrote: “And indeed, the Blue Rose exhibition was not arranged in the same way as other exhibitions. The whole room, the ceilings, the walls, and the floor were specially upholstered in various kinds of material, everything was calm, the harmony of it all really gave off a blue smell, and the exhibition was accompanied by quiet music, which was intended to tie everything together and enhanced the overall harmony of the exhibition.” “И действительно, выставка «Голубая роза» была обставлена не так, как другие выставки. Все помещение, потолки, стены и пол были специально обиты разного рода материей, все было спокойно, гармония всего сделанного действительно давала голубой запах, выставка сопровождалась тихой музыкой, долженствующей связать все и дополнить собою общую гармонию выставки. ‘Голубая роза’ расцвела живописью и музыкой”. (Kazimir Malevich, Zametka ob arkhitektury (1924)).

11 Ibid. “Здесь были пятна разных форм, которые издавали подобно цветам ароматы, которые можно было обонять, но не рассказать, из чего этот аромат состоит.”

12 It is significant to note that, rather than providing titles for his works, Malevich, in Cyrillic inscriptions on the reverse, put greater emphasis on indicating the medium — fresco.

13 Maurice Denis, ‘Définition du Néo-Traditionnisme’, in Maurice Denis, Théories 1890–1910 (Paris: Rouart et Watelin, 1920), p. 8.

14 [S. Makovskii], ‘XII-ia vystavka kartin “Moskovskogo tovarishchestva khudozhnikov”’, Iskusstvo, 2 (1905), p. 52. Quoted in John E. Bowlt, ‘The Blue Rose: Russian Symbolism in Art’, The Burlington Magazine, 118, 881 (August 1976), 566–75 (p. 571, note 14).

15 The fact that Denis named his home and studio in St Germain-en-Laye a “priory” gives some credence to the artist’s spiritual mission: like a monk, he abandons the physical and carnal world to commit to a higher calling for the good of others.

16 Photograph in the public domain. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Émile_Bernard_Autoportrait_symbolique_1891.jpg

17 According to the Symbolist critic and theorist Albert Aurier, Gauguin’s hypostasising of himself as Christ represents a complex existentialist state that draws on “a potent algebra of ideas”. Referring to Gauguin as an “algebraist of ideas”, Aurier emphasised a series of associations elicited by Gauguin’s works that produced spiritual exaltation. See Albert Aurier, ‘Symbolism in Painting: Paul Gauguin’, in Symbolist Art Theories: A Critical Anthology, ed. by Henri Dorra (Berkeley, CA, London: University of California Press, 1994), pp. 192–203 (p. 193).

18 One has in mind paintings such as Kuznetsov’s Night of the Tuberculosed (1907, Medical Institute, Moscow).

19 United in the gesture of ‘cloaking themselves in Christ’ by making the sign of the cross, the faithful give witness to the sanctification of man (and, by extension, the whole world) as promised by God. The faithful become one with the theological imagery that surrounds and envelops them.

20 Photograph in the public domain. Wikiart, https://www.wikiart.org/en/kazimir-malevich/not_detected_219728

21 Maurice Denis. The Offertory at Calvary (c. 1890). Oil on canvas, 32 x 23.5 cm. Private collection.

22 The word ‘church’ (sobor) means ‘convocation’ or ‘reunion’ — connoting, as St Cyril of Jerusalem specified, the convocation of all mankind, uniting the self with others. As explained at different times by Athanasius the Great, St John Chrysostom, and St Augustine, the term ‘church’ means ‘to summon’ (or ‘convoke’) from somewhere, bringing the presence and the promise of the Kingdom of God to the fallen world. It prepares the world for Christ’s Second Coming. The frescoes that cover the walls of Orthodox churches are designed to confirm this message.

23 However, the work was more likely modelled on the Theotokos icon of the Hodigitria.

24 In his autobiographical notes, Malevich mentions “being intensely affected by his initial encounter with professional painters, who had come to his hometown to decorate a church” (see Nakov, Malevich, p. 27).

25 One of the most prominent figures at the Kyiv Art Institute was the monumentalist Mykhailo Boichuk, who, in his capacity as rector of the Ukrainian Academy of Art almost a decade earlier, had created a Studio of Religious Painting, Frescoes, and Icons. During the 1920s, when the Academy was re-established as an Institute, Boichuk headed the Monumental Paintings Section and developed a reputation as a Neo-Byzantinist, creating multiple mural projects throughout the country. Malevich’s encounter with Boichuk’s followers in Kyiv (the Boichukists) led to a return to figuration in Malevich’s art, inspired by the Neo-Byzantine monumentality of Boichukism. See Myroslava M. Mudrak, ‘Malevich and His Ukrainian Contemporaries’, in Rethinking Malevich: Proceedings of a Conference in Celebration of the 125th Anniversary of Kazimir Malevich’s Birth, ed. by Charlotte Douglas and Christina Lodder (London: Pindar Press, 2007), especially pp. 104–18.

26 It is worth noting that Malevich’s works predate any other avant-garde artist’s treatment of the apocalyptic subject. Kandinsky’s earliest references to such themes, for example, in his painting All Souls, Pilgrims in Kyiv, occur only in 1909.

27 The Byzantine-Orientalist themes of the Ballets Russes — the World of Art’s most spectacular achievement on the world stage — took up the themes of Eastern Orthodoxy in theatrical production when Sergei Diaghilev commissioned the Neoprimivitist painter, Goncharova, to design the scenography for Liturgie (1915). See Natal′ia Goncharova, Décor for the ballet Liturgie (1915). Watercolour, graphite, cut and pasted paper, silver, gold, and coloured foil on cardboard, 55.2 x 74.6 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accession no.: 1972.146.10. Rights and Reproductions: 2011 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/480990

28 For example, such paintings as Paul Gauguin’s The Yellow Christ (1889). Oil on canvas, 91.1 x 73.4 cm. Albright-Knox Gallery, and Paul Sérusier’s Incantation (The Holy Wood), 1889. Oil on canvas, 72 x 91.5 cm. Musée des Beaux-Arts. Quimper, France.