12. Auto-Palimpsests:

Virginia Woolf’s Late Drafting of Her Early Life

© Hans Walter Gabler, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0120.12

I

At the time of her death Virginia Woolf left handwritten and typewritten materials collected together under the title ‘Sketch of the Past’. They divide into two batches, one from the summer of 1939 and the other from the summer and autumn of 1940. These are preliminary materials for an autobiography, with especial emphasis on the years of her childhood and youth. Woolf wrote ‘Sketch of the Past’ in segments, as intermittent relief from her ongoing writing (in 1939) of her biography of Roger Fry and (in 1940) of Between the Acts. The materials consist of an incomplete set of draft units written in her own hand, and a continuous self-typed typescript of the full run of the 1939 and 1940 writing of the ‘Sketch of the Past’ she never finished. The segments are identically dated in the draft materials and in the typescript. Pagination patterns in the typescript, especially for the 1939 batch of segments—whether extant or lost in manuscript—indicate that Woolf tended to prepare the typescript by segments, immediately or very soon after finishing the respective draft. It may be inferred, moreover, firstly that the typescript represents the entirety of the text as completed, and secondly that the segments existing only in typescript were most probably derived throughout from handwritten antecedents. This means, importantly, that each segment present in both manuscript and typescript exists in two versions, and that wherever a section survives only in the typescript, what has been preserved is the segment’s text in its second version, the first having been lost.

All segments surviving in both a first and a second version reveal an intensive process of revision, initially within the manuscript, and then in particular at the point of transfer of the text from manuscript to typescript. This allows us to distinguish layers and levels in the textual genesis, and these in turn reveal the creative driving forces from which they sprang. The creative goal of ‘Sketch of the Past’ is not imaginative fiction, nor the analytic mode of the essay. Generically, the writing is autobiography. Characteristic of the ‘Sketch of the Past’ materials is the way in which they move in modulations of composition and revision. This enables us analytically and critically to discern aspects of the autobiographical ‘I’ behind the writing process and the written word. It is an ‘I’ discerned in the past in a life lived, and also a present ‘I’ that, while looking back, thoughtfully reflects on this other ‘I’ and that past life, even as a third ‘I’, the persona of the writer and author, assumes artistic control, shaping and reshaping both the language and content of the autobiographical account.

The dating of the segments contributes to establishing the self-reflective perspective of this account. It provides a protocol of actual situations as a backdrop to the memories recalled. The real-life spans of writing stood under threat of war in the spring and summer of 1939, when the Second World War was felt to be imminent. By the following summer and autumn of 1940, the war had broken out, there was no let-up in the bombing of London, and there was general fear of a German invasion, particularly among the professional and social circles of Virginia and Leonard Woolf. It is of great significance for the present essay that Virginia Woolf, while reflecting on the general situation and on her situation as a writer at this time, successively sketches out what may be regarded as her own poetics of autobiographical writing.

II

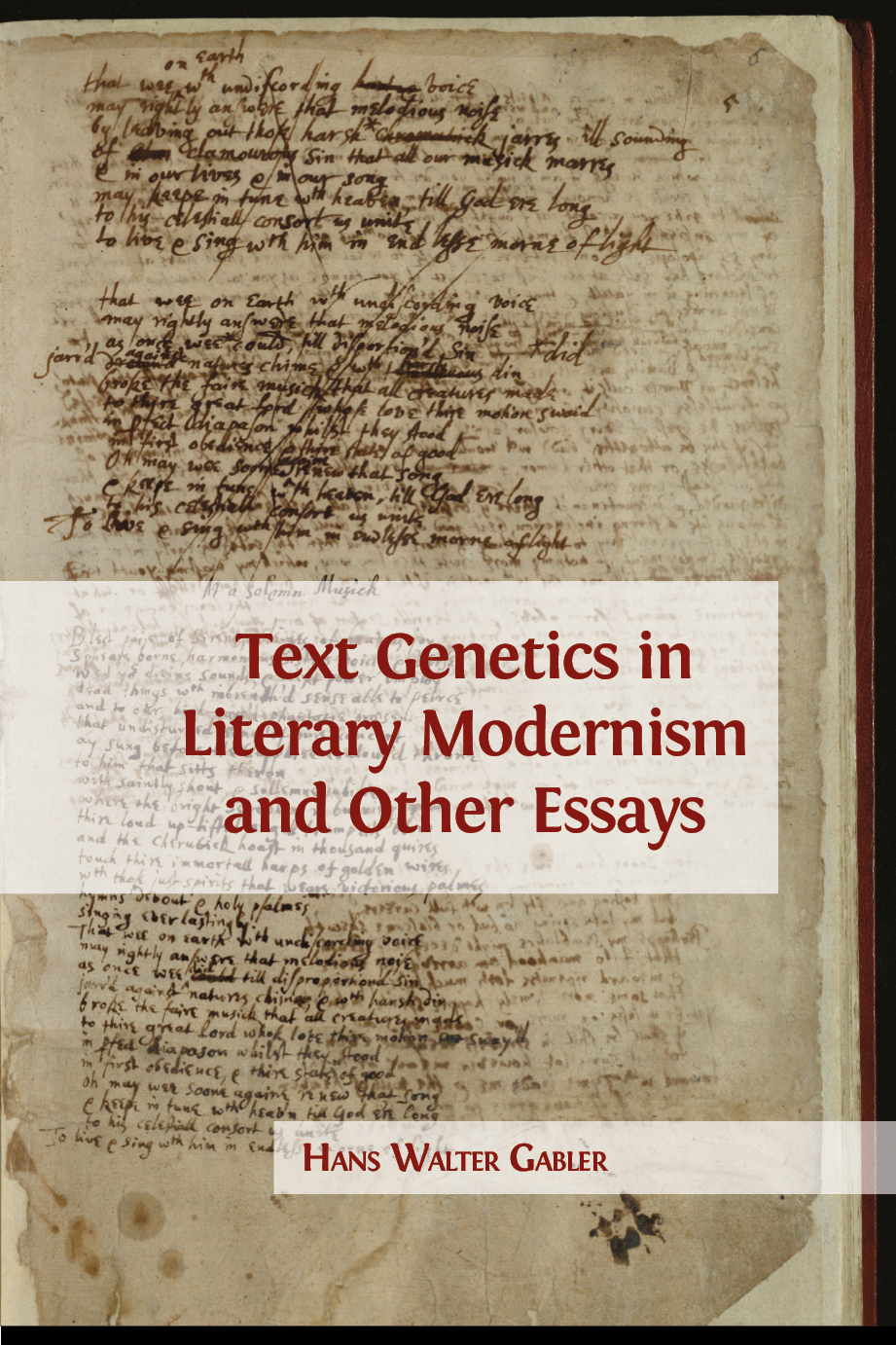

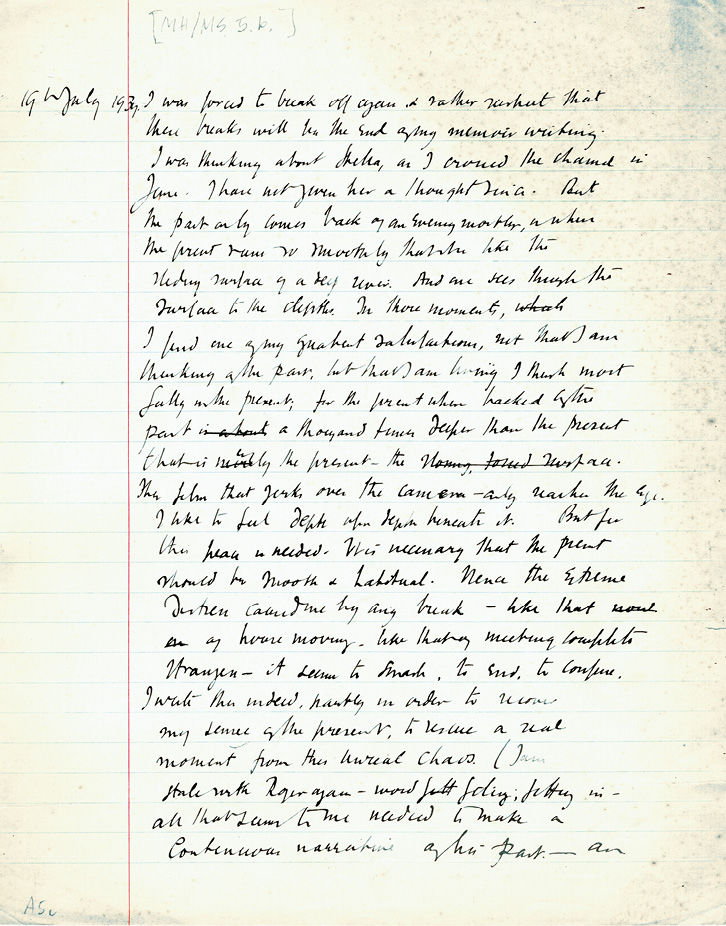

This is made very clear by the two versions of the beginning of the segment dated 19 July 1939, the second of the eight segments—out of the total of fourteen—that survive in two versions. It is the sixth segment in the overall sequence. (See Figs. 12.1 and 12.2.)1 In content, the segment preliminaries focus intently on the writer’s situation. With regard to external circumstances, reference is made to the Woolfs’ move within London, from what had been their home in Tavistock Square for many years to Mecklenburgh Square. Within the space of a year both homes were destroyed by German bombs. In the chaos of moving the author loses all sense of connecting to the real present, just as she does, as she says in the first version, when ‘meeting complete strangers.’ The loss of connection to her present life, causing her ‘extreme distress’, she attributes to a loss of ‘peace’. The present needs to be ‘smooth and habitual’ in order to open onto the depths of the past, which only with this transparency can become fully present. Writing must make it possible to regain such peace, so as to allow her to plumb the depths of memory and call up moments of past reality to the surface of the present. At this point in time Virginia Woolf ‘feels stale with Roger again’ (MS) and sets out to cope with her writer’s block through other writing, ‘taking a morning off from the word filing and fitting that my life of Roger means’ (TS). The predominant image in this opening passage is that of flowing water, of the stream of memory gliding beneath the water’s smooth surface, transparent down to the depths of the past, and symbolic of the challenge and, not least, also the chilling effect, of seeking to connect the past and the present. ‘Let me then like a child advancing with bare feet into a cold river descend again into that stream.’ (End of preliminaries on 19 July 1939, typescript version)

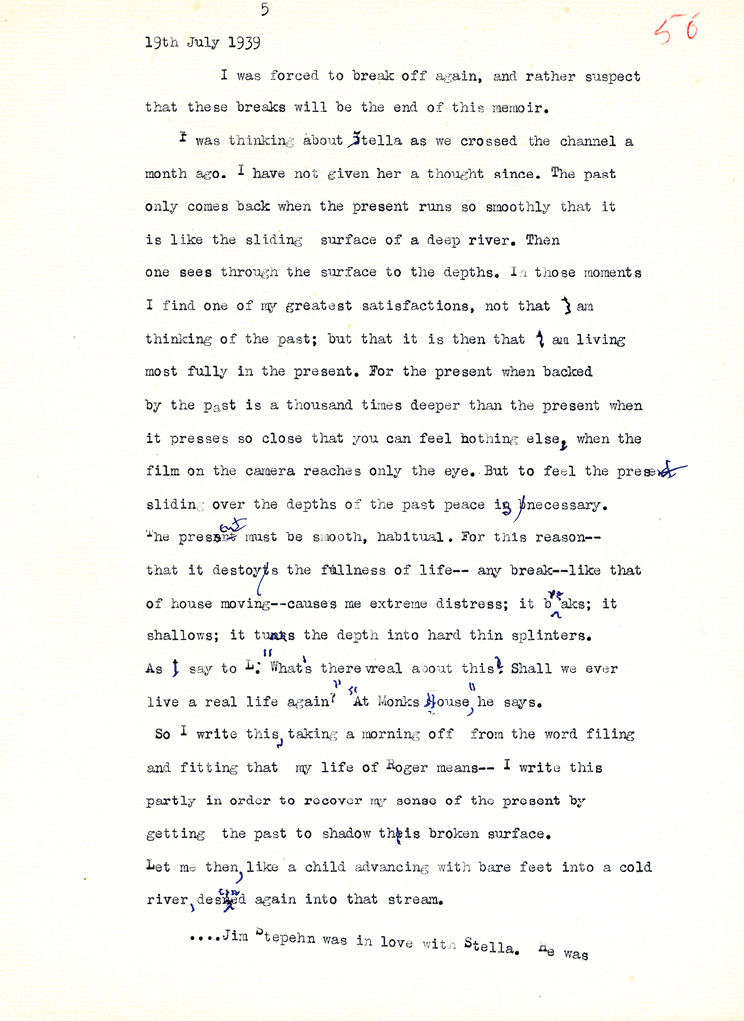

The texts of the preliminaries in manuscript and typescript may be juxtaposed for comparison. (see Fig. 12.3—Text in black is identical; text in blue on the left is first version manuscript text; text in red on the right is text revised in the typescript.)

Fig. 12.1 ‘A Sketch of the Past’, manuscript, 19 July 1939, fols. 1-2. University of Sussex Library, The Keep, SxMs-18/2/A/5/C. © The Society of Authors, all rights reserved.

Fig. 12.2 ‘A Sketch of the Past’, typescript, 19 July 1939, fol. ‘56’. University of Sussex Library, The Keep, SxMs-18/2/A/5/A. © The Society of Authors, all rights reserved.

Fig. 12.3 19 July 1939 preliminaries: a Juxta collation mock-up

of manuscript versus typescript

As she types up her manuscript Woolf does not confine herself to reproducing the draft text. She rewrites copiously, and her deletions, changes and additions pervasively enhance the precision of her thoughts, especially through greater depth and more sharply etched imagery. The topos that she is attempting an ‘impossible task, no doubt’ falls by the wayside in the typescript rewriting. The nub of the revisions introduced throughout the preamble is the desire ‘to recover my sense of the present’ by means of ‘getting the past to shadow’ it. This is to be achieved by putting together again (and anew) the splinters into which the disturbance on the flowing surface of the present had seemed to fragment the past.

Taken together, the revisions in their genetic progression add up to a readjustment of the writer’s perspective of herself. Schooled in narrative analysis, we might regard this merely as a variant on the orthodox differentiation between an experiencing and a narrating ‘I’. However, this would be misleading, or at least too simple, since ‘Sketch of the Past’ is not fiction; it records memories of a life. However clearly one may see and hear the text as shaped by a literary narrator’s skill, neither the figures it presents nor the space it creates are situated in an imaginary realm of fiction. The narrating ‘I’ in particular is not a fictional ‘I’, invented to pilot the narrative through its pasts and presents. The narrating ‘I’ is instead, pure and simple, Virginia Woolf, recording what she remembers as notable from the past of her childhood and youth.

Woolf herself makes it very clear that ‘Sketch of the Past’ was not written, and should not be read, according to the accustomed modalities of fiction. In bringing to mind her memories of the past, she says, ‘I am living most fully in the present’. This self-awareness she affirms by dating in real time the segments as she successively writes them. Through insistently emphasizing the present, Woolf seeks clarity in her self-perception as past (Virginia Stephen) and present (Virginia Woolf). What she writes and therefore conveys of the ‘I’ of the past as autobiographically remembered has a medial function leading towards the ‘I’ of the present. It is on this ‘I’ of the present, perceived and perceiving, critically observing, that the creative awareness is pivoted. To this pivot the ‘I’ Virginia Woolf, the writer, attaches in language of the present her biographical and autobiographical memories, grounded in the past of her own existence.

So to distinguish from a past and a present ‘I’ also the ‘I’ of Virginia Woolf, the writer, allows us to observe the autobiographical writing as intensely dynamic labour sustained over two documents. Active already in the coming-into-being of the manuscript text, it explodes in the creative revisions undertaken in the course of the typing. Comparison of the typescript version against the draft gives rich evidence of this. The writing ‘I’ joins the ‘I’ of the past autobiographically remembered and the ‘I’ of the real present perceiving itself more deeply in that present through the medium of its remembered alter ego from the past. As creative agent and force, the writing ‘I’ is distinguishable specifically from the present real-life ‘I’ through its dual function in and for the writing. It brings artistic skill to bear on language, style and overall disposition of the text-in-progress. It also structures content, decides on inclusions and exclusions, and is prepared on occasion to act as censor. It is through the writing ‘I’s exercise of these functions that a dynamically diachronic text rich in variation is progressively laid out on paper. This reveals not only the valid text achieved, but also what potentials of articulation in language and of meaning were considered and then rejected. Where, in ‘Sketch of the Past’, the writing ‘I’s labour manifests itself in its material traces in such a way, an accumulation of text over time, multidimensional in its meaning potential, offers scope for critical evaluation. In what follows, the genetic progression of ‘Sketch of the Past’ will be explored under one particular aspect. Through the creatively critical (and self-critical) energies set free by her writing ‘I’, Virginia Woolf, from composition to revision, develops a tendency even to overwrite ‘herself’—to create auto-palimpsests within the progression of the text over the time of its writing.

III

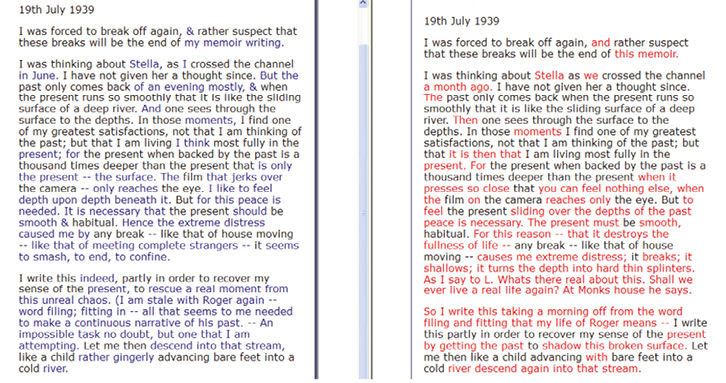

Traces of authorial reflection can be seen from the very earliest revisions (see Fig. 12.4). To begin with, these are not always auto-palimpsests in a narrow sense. As might be expected, they often seem to result from close consideration of coherence of thought and structure, and quality of language and style. Yet at times they also include comments that reveal a momentary refusal to stay within a broad plan, or to sacrifice forward momentum to a compulsive desire for perfection: ‘without stopping to choose my way, in the sure and certain knowledge that it will find itself—or if not it will not matter—I begin’.

Virginia Woolf’s differentiated awareness of the complexity of the task before her is evident from the moment she sets out to write her autobiography. The enterprise is intellectually complex, and complex also because it is conditioned by memory, by the ability or inability to remember. Furthermore, it is complex in its narrative perspective. It is hard to imagine a more succinct indication of the acute self-perception at work in this writing than the insertion into the typescript of a highly significant word signalling the writing ‘I’—added on a last rereading of what had already been written and typed. This happens as follows.

Virginia Woolf starts her recollections with what she defines as her earliest memory, the flower patterns on her mother’s dress: ‘the first memory. | This was of red and purple flowers on a black ground—my mothers dress.’ Yet the visual perception recalled is initially given no specific location; rather, the writer is drawn to frame it within a generalised act of remembering:

Fig. 12.4 ‘A Sketch of the Past’, typescript, 18 April 1939, fol. 1. University of Sussex Library, The Keep, SxMs-18/2/A/5/A. © The Society of Authors, all rights reserved.

[my mother] was sitting either in a train or in an omnibus, and I was on her lap. I therefore saw the flowers she was wearing very close; and can still see purple and red and blue, I think, against the black; they must have been anemones, I suppose. Perhaps we were going to St Ives; more probably, for from the light it must have been evening, we were coming back to London.

The framework given to this visual perception is an iterative construct. The writer recognises this, and spells it out herself, in the process of re-vision—looking and reading again. And she is prompted to conclude that this consciously literary operation can and must contribute to continuing and further shaping the text:

it is more convenient |+artistically+| to suppose that we were going to St Ives, for that will lead to my other memory, which also seems to be my first memory,

The adverb ‘artistically’, added at the re-vision stage, occurs at the interface between autobiographical writing and its artistic control. It is the craft of writing that gives the text its particular quality. The writing ‘I’ shapes with care the narrative of memory as it evolves. She subjects to its control, too, traces of memory of language. Variants in the material writing reveal that Woolf recognises words and phrases as constituents of the memories she draws on. A striking example occurs on this same typescript page, in the arrow-marked line (Fig. 12.4, below mid-page). In the run of typing, ‘hope’ is xxx-ed out and instantly substituted by ‘knowledge’. What we see happening is that a formula that had spontaneously asserted itself from Woolf’s memory store of phrases undergoes immediate revision. The phrase as first typed comes from the service for the Burial of the Dead in The Book of Common Prayer: ‘Forasmuch as it hath pleased Almighty God of his great mercy to take unto himself the soul of our dear brother here departed: we therefore commit his body to the ground; earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust; in sure and certain hope of the Resurrection to eternal life […]’.2 While by the instant retake in the run of her typing Woolf renounces the transcendental hope held by the ‘we’ of the Christian community and embraces in its stead her, the individual writer’s, secular knowledge, the revised wording still retains the formulaic strength of the original utterance and draws from it courageous affirmation of the self. With the grounds laid for her autobiographical writing on this first page of the typescript, Virginia Woolf is well under way to asking the question on the second page: ‘Who was I then?’ (see Fig. 12.5, bottom), and later, firmly setting off the ‘I’ between quotation marks, reshaping it into: ‘But who was “I”?’ (see Fig. 12.7, end of first paragraph)

IV

It is a challenge to achieve insights into oneself, one’s own biography, one’s memories, one’s ability to remember and to process memories, by means of writing. Yet challenging as it may be, we know it can be achieved, not only in biographical but also in fictional mode. Virginia Woolf wrote in both modes, and when she began in 1939 to sharpen her view of herself in ‘Sketch of the Past’, and to call to mind memories of her mother and father, she was well aware that fifteen years earlier she had fictionalised the key constellations and significance of these memories in her novel To the Lighthouse. For our purposes, a key point of interest in the memoir is that the material record of autobiographical notes reveals a discernible process, signalling a twofold self-perception: the self-perception of the text and that of the author in the course of writing. The self-perception of the writer is diachronic: it has a past and a present dimension. Plunging retrospectively into the past—real past and therefore objective, but dependent on memory and therefore subjective—has consequences for the progress of the text, enriching and adjusting self-perception often in equal measure, while generating textual revisions and additions, and carrying the text forward.

Thus, with the text as starting-point, the preconditions for analytical genetic criticism of every sort may seem to be fulfilled. However, autobiographical writing creates its own conditions, adding new dimensions to any analysis. In the writing process, and emerging from it, autobiographical writing reveals shifts of consciousness and new perspectives on the levels of the remembered and the narrated ‘I’, which the writing ‘I’ seeks to articulate in fluctuating identification with memory and narrative. Remembered, narrated and writing ‘I’ are interwoven in the complexities of the text’s autobiographical ‘I’. This autobiographical ‘I’ may be narrated, yet it is not invented. However many layers of shaping and reshaping there may be, it represents an individual with a life history, a historically real social being.

In the process of revision, the memory of the flower patterns on the mother’s dress is relocated on the journey to, rather than from, St Ives. The next memory, mentioned in second place but of equally early date, reads (see Fig. 12.5):

It is of lying half asleep, half awake in bed in the nursery at St Ives. It is of hearing the waves breaking, one, two, one, two, and sending a splash of water over the beach; and then breaking one two one two behind a yellow blind.

This recalls the sounds the child heard every evening as she was falling asleep in the house in St Ives, where the Stephen family spent their summers in the late 1880s and early 1890s with the entire household (including the London servants) and household effects.

The extent to which the writing ‘I’ controls the bringing-to-life in the narrative is clear also in the metaphorical significance of memory assigned by self-reflection during the course of writing, before any concrete perception of the breaking of the waves at evening is reached. The momentum of the writing is approaching this memory, complete with its associated emotion, but its arrival is deferred for a whole sentence. Before it reaches the paper, it is preceded by an image foreshadowing the profundity of its meaning:

→ If life has a |-stem-| |+base+| that it stands upon, if it is a bowl that one fills and fills and fills—then my bowl without a doubt stands upon this memory.

Fig. 12.5 ‘A Sketch of the Past’, typescript, 18 April 1939, fol. 2. University of Sussex Library, The Keep, SxMs-18/2/A/5/A. © The Society of Authors, all rights reserved.

The potency of memory, specifically also in generating text, as recalled by the sound of the waves breaking on the shore every evening in ‘Sketch of the Past’, is open to analysis in many places in Virginia Woolf’s oeuvre, and it takes many forms. As a distant pulse it beats through, and indeed structures, The Waves, the pinnacle of Woolf’s modernist novel-writing. In ‘Sketch of the Past’, however, the writer does not embark on autobiographical recall of sense perceptions in analytical mode, but rather by way of the emotions. The bowl of memory is filled with sense perceptions recalled with vivid immediacy, which yields feelings of pure bliss. The writing ‘I’ puts this into words: ‘I could spend hours trying to write that as it should be written, in order to give the feeling which is even at this moment very strong in me.’—whereupon the flow of recorded memories stalls for a moment, because it is necessary before proceeding to locate the remembered, the present and the writing ‘I’ as coordinates on the graph of the autobiographical ‘I’ generated by writing. This gives pause for consideration of further conditions imposed by (auto)biographical writing, culminating in inquiry into the writing ‘I’:

But I should fail […] I should only succeed […] if I had begun by describing Virginia herself.

Here I come to one of the memoir writer’s difficulties—one of the reasons why […] so many are failures. They leave out the person to whom things happened. The reason is that it is so difficult to describe any human being. So they say: “This is what happened”; but they do not say what the person was like to whom it happened. And the events mean very little unless we know first to whom they happened. Who was I then?

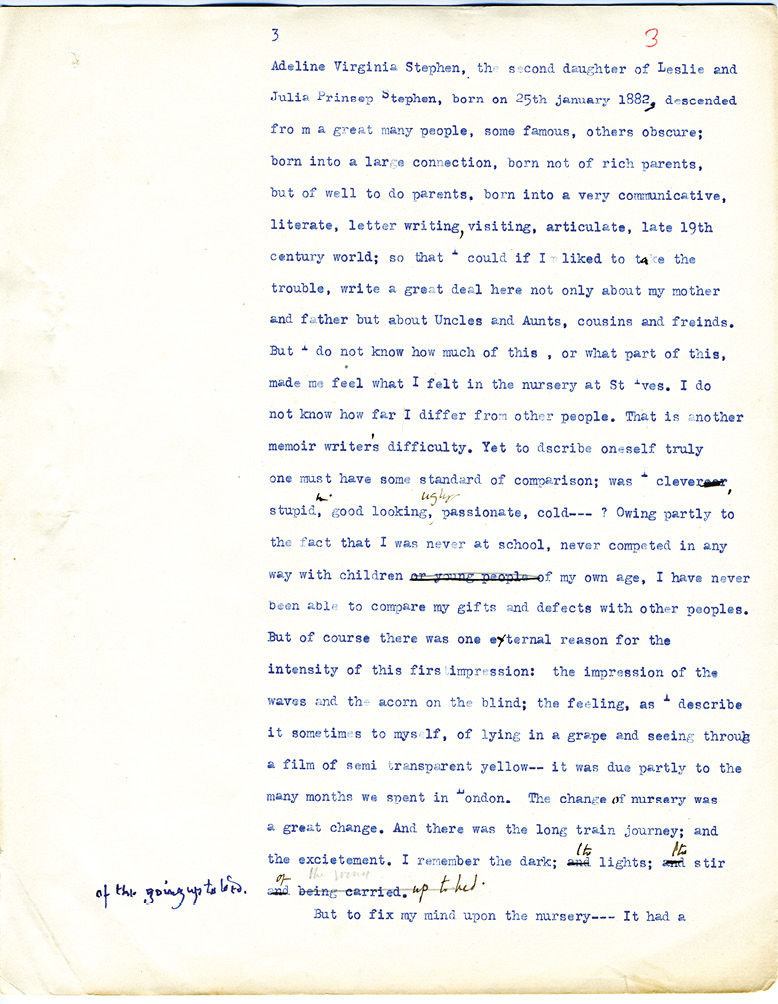

This is followed by a passage that begins with the factual identification of given names, parents’ names and birthday, then outlines their descent, their social standing in the late nineteenth century, and their level of education, and gives some indication of the potential usefulness of relations and friends as material for biographical narrative (see Fig. 12.6).

Fig. 12.6 ‘A Sketch of the Past’, typescript, 18 April 1939, fol. 3. University of Sussex Library, The Keep, SxMs-18/2/A/5/A. © The Society of Authors, all rights reserved.

The items of information offer heterogeneous starting-points for the transfer of the remembered and narrated ‘I’ into an autobiographical ‘I’. Hovering between the points represents a first tentative move towards answering the rhetorical question ‘Who was I then?’. The prosaic beginning may sound like preparatory notes for an entry in a volume such as the Dictionary of National Biography (the massive reference work edited by Virginia Woolf’s father, Sir Leslie Stephen). Yet this impression does not last long, since the ostensible entry soon puts in question the validity of such assertions, and their relevance to the childhood remembered. It succumbs once more to memories of evening in the nursery in St Ives. In the movement of the writing we see an early indication of the overwriting, often repeated, of one ‘I’-perspective by another:

But I do not know how much of this, or what part of this, made me feel what I felt in the nursery at St Ives. I do not know how far I differ from other people. […] Yet to describe oneself truly one must have some standard of comparison; was I clever, stupid, good looking, |+ugly,+| passionate, cold—?

As we look at the first three pages of the typescript of ‘Sketch of the Past’ we see the pendulum go back and forth between memory and reflection, yet neither of the key questions raised by this opening receives a full answer. It does not provide a consistent ‘objective’ answer to the question ‘Who was I then?’, nor does it enter more deeply into the complexities required of autobiographical writing if it is to do justice to Virginia Woolf as woman and writer.

It is of some interest that this opening passage has also survived in another version, a single machine-written page also typed by Virginia Woolf herself. Whereas up to now we have been dealing mostly with implicit overwriting of the self, the relationship of these two typescript versions to one another allows us to grasp for the first time the material reality of the ‘auto-palimpsest’. The question arises: which of the two typescripts represents the first version, which the second (or, within the framework of the whole genetic spectrum as we see it: which is the second, which the third version; the handwritten version presumed to have preceded both has not survived for this passage).

The single typed page is so ‘untidily’ written and peppered with typing errors, as compared with the complete typescript, that one might be inclined to see it as a precursor of the continuous whole. However, the experienced reader of typescripts written by Woolf herself will know that the evidence points in the opposite direction—towards intensive thought while rewriting an exemplar. It is likely that the shorter text on the single page derives from the longer text in the complete typescript and hence represents a later genetic stage. A succinct piece of evidence for this assumption occurs in the variant readings of one phrase cited above, from the passage comparing the narrative of life with a bowl that one fills and fills and fills. In the complete typescript, ‘it has a stem that it stands upon’ is corrected to ‘has a base that it stands upon’. The single-leaf text begins with this image, and the bowl has a ‘base’; it thus incorporates the revision inserted into the complete typescript. This establishes that the single-leaf text represents a further revision of the text in the complete typescript, and consequently that the single leaf is the later document. The passage is given here in full (with Virginia Woolf’s typing errors corrected), since it has not been reproduced elsewhere for the original typing (see Fig. 12.8):

Sketch of the Past.

If life is a bowl which stands upon a base, it must stand

for me upon two memories; the purple red and blue flowers

on my mothers black frock; the sound of waves breaking.

These two memories are connected with travelling;

and the end of the journey was Talland House, St Ives.

But who was “I”?

Adeleina Virginia Stephen, born on the 25th January

1882. To that I can add that I was descended from

a great many people; some famous, others obscure. I was born

not of rich parents, but of well to do parents. I was born

into a very articulate, letter writing, book writing,

articulate world; so that if I liked, I could write here

a great deal, not only about my father and mother,

but about Uncles and Aunts, cousins, and friends.

The influence of heredity has presumably told upon me

and will make itself apparent, to the reader, without

much direction from me. I am met at the outset however,

by a difficulty which is not always present. Owing to the

fact that I was never at school, and thus never competed with

children of my own age, I find it difficult to compare myself

with other people. Was I clever, stupid, good looking,

passionate or cold? Here however I can evade those

difficult problems: for there was an external reason

for the vividness of these two impressions. We

lived in London; the journey to St Ives was a great event.

So naturally my mothers dress, and the breaking wave

penetrated the envelope of unconsciousness.

Establishing the direction of change makes it possible to see that the first paragraph of the later version constitutes a radical intertwining and compression of two entire pages in the first typescript’s gradual unfolding of memory. The long second paragraph of the new version incorporates material from the paragraph that sounded like the beginning of an entry from a reference work. (Fig. 12.7 juxtaposes the two versions:)

Fig. 12.7 A Juxta collation of the Virginia Stephen biography

outline in two succeeding typescripts

The text in he first typescript stems from a dialogic intimacy, which arises from seeking and feeling memories, and also from experimenting with different modes of writing in order to bring the memories to life. Characteristic of the new version is a coolness of tone and increased distance, brought about by rigorous compression. In the revision, too, the register for an ‘entry in a biographical dictionary’ is more decisively selected. The single-page text reads like the beginning of a public autobiography, a clear instance of overwriting the earlier text contained in the complete typescript. It transforms the private record into a public document, whereby the latter not only replaces the former; the private person Virginia Woolf is also overlaid by the persona Virginia Woolf, the focus of an autobiography intended for the public. Typical of the writer’s aloof control of her writing is the manner in which the overwriting is explicitly signalled as rewriting with a view to being read: ‘The influence of heredity has presumably told upon me and will make itself apparent, to the reader, without much direction from me.’

Fig. 12.8 ‘Sjetch of the Past’, typescript, n.d., fol. 1. University of Sussex Library, The Keep, SxMs-18/2/A/5/E. © The Society of Authors, all rights reserved.

The perspective adopted for the present investigation makes it possible to identify the relationship between the two versions even more specifically. We can assess the textual distance between one text and the other, and we can also identify the revisions as ‘auto-palimpsest’ overwriting. The differentiation between one ‘I’ and another enables us to say that within the space shared by the remembered, the narrated and the writing ‘I’, it is the writing ‘I’ that has resumed control, with consummate skill, of the single-page text.

Virginia Woolf did not develop her autobiography as ‘public text’ any further along the lines of this initial experiment. She ended her life only four months after her dating of the last surviving segment of ‘Sketch of the Past’. It is impossible to say whether she would have chosen to apply this register to the entire text, but it is appropriate to view all the surviving materials in the light of this single preparatory page, which is a rich source of discernible processes of writing, rewriting and overwriting. A later passage provides further instances of such processes.

V

In the first stint on ‘Sketch of the Past’ in the summer of 1939, Virginia Woolf accomplished the recording of her childhood and early youth. This stretch of writing, segments 1 to 6, is dominated by the figures of her mother and her half-sister Stella, and ends with their deaths, only two years apart, in 1895 and 1897. When she picks up the record in the summer of 1940, Woolf concedes that she now faces a new and psychologically very difficult challenge:

My father now falls to be described, because it was during the seven years

between Stella’s death in 1897 and his death in 1904 that Nessa and I were

fully exposed without protection to the full blast of that strange character.

……… he … obsessed me for years. …… I would find my lips moving;

I would be arguing with

him; raging against him; saying to myself all that I never said to him. How

deep they drove themselves into me, the things it was impossible to say

aloud. They are still some of them sayable [sic]; when Nessa for instance revives

the memory of Wednesday and its weekly books, I still feel come over me

that old frustrated fury.

But in me, though not in her, rage alternated with love. It was only the

other day when I read Freud for the first time, that I discovered that this

violently disturbing conflict of love and hate is a common feeling; and is

called ambivalence.

We may find it astonishing that Virginia Woolf should say she read Freud for the first time in 1940, given that she was co-founder of The Hogarth Press and, in the early days, even its typesetter, and the press had published Freud’s works volume by volume in English translation from 1924 onwards—and it may suggest to us that the common intellectual stock of an era comes to be shared more through contemporaries thinking similar thoughts with regard to similar questions, than through systematic study of one another. Freud, for his part, may have read Virginia Woolf at some point, and constructed a psychogram of her—or did he perhaps (too?) know her only by hearsay? Be that as it may, it is said that on the one occasion when they met he handed her:—a narcissus. It must remain an open question, whether Woolf really needed to read Freud in order to take up the challenge of describing her father. At all events, she describes the horrors of Wednesday, the day when the weekly household accounts had to be submitted—and because it was such a painful burden to remember this day, to recount what she remembers, and to weigh and find words for its diverse and divergent details, it comes as no surprise that for this section there are several layers of notation, allowing us to observe the process of putting into words what surfaced in memory.

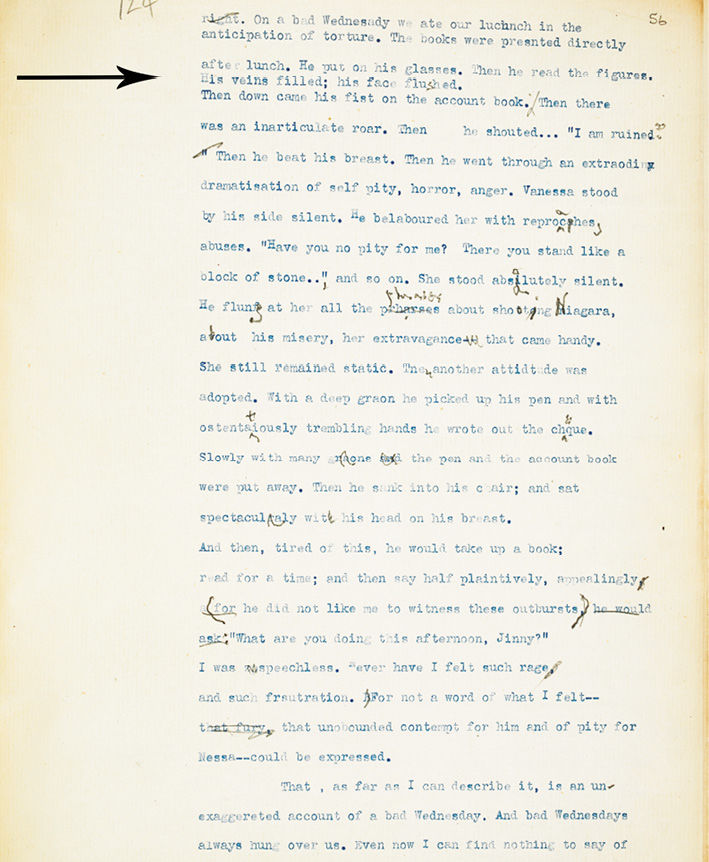

Let us move backwards this time, starting from the final stage of revision. It provides the best overview of what needed to be said—or rather, what Woolf in the end could bear to say. The end result of the turbulence of the overwriting stage, where the manuscript notes were transmitted to typescript, may be displayed as follows (with light editorial trimming):3

And over the whole week brooded the horror, the recurring

terror of Wednesday. On that day the weekly books were

given him. Early that morning we knew whether they were

under or over the danger mark - eleven pounds if I remember

right. On a bad Wednesday lunch was torture. The books

were presented directly afterwards. There was silence. He put on his glasses. Then he read the figure. Eleven pounds

eighteen and six… There was a roar. Down came his fist on

the account book. Then he shouted: You are ruining me…

Broken words came through what seemed a continuous roar of

fury. He beat his breast. He dropped his pen. He indulged

[p. 124]

right. On a bad Wednesday we ate our lunch in the

anticipation of torture. The books were presented directly

after lunch. He put on his glasses. Then he read the figures.

|+His veins filled; his face flushed.+|

Then down came his fist on the account book.↑ Then there

was an inarticulate roar. Then he shouted… “I am ruined.”

Then he beat his breast. Then he went through an extraordinary

dramatisation of self pity, horror, anger. Vanessa stood

by his side silent. He belaboured her with reproaches,

abuses. “Have you no pity for me? There you stand like a

block of stone..,” and so on. She stood absolutely silent.

He flung at her all the phrases about shooting Niagara,

about his misery, her extravagance - that came handy.

She still remained static. Then another attitude was

adopted. With a deep groan he picked up his pen and with

ostentatiously trembling hands he wrote out the cheque.

Slowly with many groans the pen and the account book

were put away. Then he sank into his chair; and sat

spectacularly with his head on his breast.

And then, tired of this, he would take up a book;

read for a time; and then say half plaintively, appealingly

(for he did not like me to witness these outbursts) he would

ask: “What are you doing this afternoon, Jinny?”

I was speechless. Never have I felt such rage,

and such frustration. For not a word of what I felt -

that unbounded contempt for him and of pity for

Nessa - could be expressed.

That, as far as I can describe it, is an un-

exaggerated account of a bad Wednesday. And bad Wednesdays

always hung over us. Even now I can find nothing to say of

his behaviour save that it was brutal. If instead of

words he had used a whip, the brutality could have been

no greater. How can one explain it? His life explains

something.

Figs. 12.9 ‘A Sketch of the Past’, typescript, November 1940, fols. ‘123’–‘124’. The British Library, MS 61973, fols. 55–56. © The Society of Authors, all rights reserved.

The figures reproduce the passage from the typescript. The lengthy crossing-out at the end of p. 123 is moved to the top of p. 124, with modifications, and two additional phrases (‘His veins filled; his face flushed.’) are typed between the lines; the scene ends at the top of p. 125 (here not reproduced in an image). The typing has more errors than usual, betraying the turmoil aroused by the conjuring up of these memories.

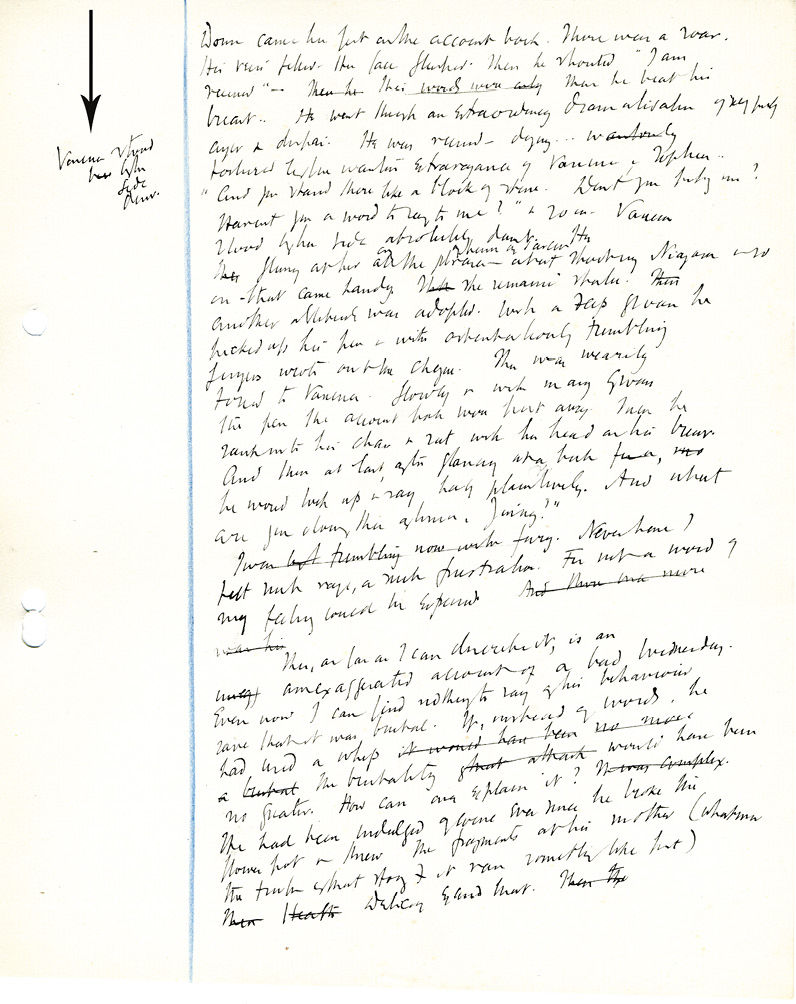

However, when we examine the manuscript sheets, we see that the emotions had already become relatively calm by the time the typing stage was reached. Moving backwards through the layers of composition, we look first at the last manuscript sheet that served as exemplar for the typescript (see Fig. 12.10).

It ends with the beginning of the attempt to explain her father’s way of behaving, but breaks off (through exhaustion?) before getting far. Most of the page is devoted to giving a fairly disciplined and complete account of the Wednesday scene. Yet it is evident that disciplining the gaze back into memory, and simultaneously giving shape to what memory conjures up, cost considerable effort. Signs of strain can be found in the marginal comment at lines 5 to 7, which repeats the content and almost the exact wording of what occurs in the continuous text at this point; and equally, in the description of her own reaction at the end of the page (‘This, as far as I can describe it, <etc>’; [my emphasis]).

Yet this is already mild, and makes relatively light demands on the reader’s empathy, compared with the previous stage, as concluded on the manuscript sheet to which we turn next (see Fig. 12.11).

Here too the flow of writing ends with an attempt at explanation, which this time comes to an abrupt halt almost at once, after one short sentence. Indeed, on this page the ‘flow’ of writing repeatedly breaks off and begins again. Nor has the scene as yet been formed coherently throughout. Phrases and sentences are repeatedly crossed out, and the margin is replete with comments and additions yet to find their place in the narrative flow of actions and feelings in the three-person scene between father, sister Vanessa and the observing, experiencing Virginia.

Fig. 12.10 ‘A Sketch of the Past’, manuscript, November 1940, fol. 38. University of Sussex Library, The Keep, SxMs-18/2/A/5/D. © The Society of Authors, all rights reserved.

Fig. 12.11 ‘A Sketch of the Past’, manuscript, November 1940, fol. 37. University of Sussex Library, The Keep, SxMs-18/2/A/5/D. © The Society of Authors, all rights reserved.

“And you stand there like a block of stone …”

|m+He wd shake all over+m|

So to a wild cry that he was deserted, that he was

done … that we had no sympathy for him. That was

of rage against her; of denunciation of her; which

made my blood boil with rage : my fingers tremble.

A little later comes the parenthetical comment regarding the father’s self-dramatisation, which, as we saw above, is positioned to greater effect in the later version, where it is not the fingers of the past observer, and present writer, that tremble, but those of the father signing the cheque—this, too, being ‘more convenient artistically’.4

The greatest surprise on this sheet comes at the end, at the moment familiar to us from the later versions when the father quits the tyrant’s role and asks Giny, that is to say, Virginia, what she intends to do that afternoon, and suggests a walk. Or does he? Who actually suggests the walk? The sheet reads:

And

then with a profound groan look up, at me, at last, &

say plaintively, yet with some regret remorse.

<what follows is not syntactically connected: it seems like overwriting from the perspective of the recollecting “I”:>

?Then I

for whom he had some pity, I so like him in

excitability,

<only then is “say” taken up again and apportioned to the father, as what he said is spelt out:>

& say “Well Giny. What about a

wa are you doing this afternoon? What about a

walk?

The asyntactical admission of kinship and similarity that overtakes the writer at this point: ‘Then I | for whom he had some pity, I so like him in | excitability,’ is no longer found in the subsequent version—a striking example of auto-palimpsest by means of deletion as the text progresses.

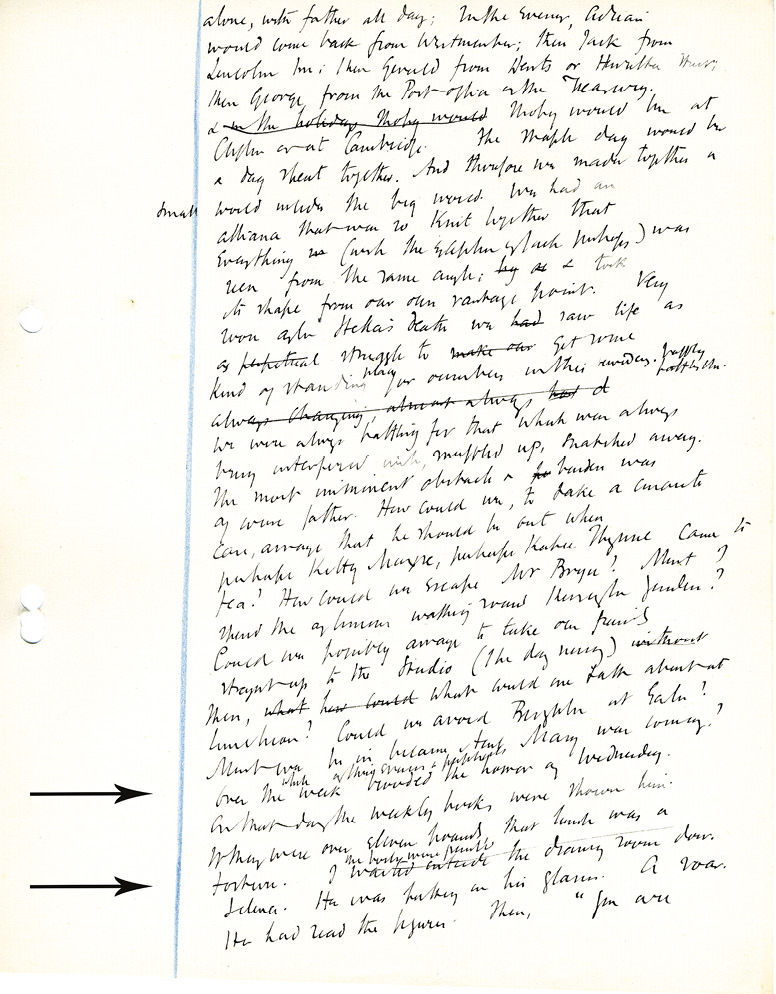

Another remarkable example of auto-palimpsest occurs on the preceding sheet, where a first attempt is made to conjure up the scene from memory. The description of the traumatic Wednesdays begins, most astonishingly, with one sentence which, even though instantly deleted, is there before us beneath the crossing-out: ‘I waited outside the drawing room door.’ (see Fig. 12.13).

How would the Wednesday scene have been handled if narrated from outside the door? To us as viewers of its progress of composition, the sentence both is, and is not, in the text—and, if nothing else, this demonstrates the value of our initial differentiation between remembered, remembering and writing ‘I’. As told, the Wednesday scene is not an unmediated, let alone a one-time, real memory. The Wednesdays were a constantly relived trauma. In narration, recall is shaped into types of memory. In reality, there was probably variation as well as iteration: there may well have been Wednesdays when Virginia did stay outside the door and let her sister face their father alone. This variant is the one that first occurred to her during the act of writing, but once written down it was immediately retracted. The successive stages of writing and deleting demonstrate that it is ‘more convenient artistically’ to have the ‘I’ in the room as experiencer. Not the remembered and remembering, but rather the writing ‘I’ has the last word in controlling perception, has cognitive control over what, through biographical narration, becomes the autobiographical text.5

Fig. 12.12 ‘A Sketch of the Past’, manuscript, November 1940, fol. 36. University of Sussex Library, The Keep, SxMs-18/2/A/5/D. © The Society of Authors, all rights reserved.

1 Holograph and typescript images in this essay are throughout digital reproductions from the originals at the University of Sussex: SxMs18/2/A/5/. University of Sussex Special Collections at The Keep; and at The British Library: MS 61973. Reproduced by permission of The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Virginia Woolf.

2 It takes our memory, as readers, to discern such intertextualities. I am deeply grateful to Warwick Gould for having alerted me, in private correspondence, to this overwriting in the typescript, and its significance. I will mention in passing that years ago, when I was transcribing early pages of ‘Time Passes’ from the To the Lighthouse holograph manuscript, Woolf’s text, in fragments of its phrasing as first put to paper, repeatedly rang of John Milton to my responding ear and memory.

3 See Figs. 12.9 and 12.10; Typescript p. 123, from mid-page.

4 Working in her native mode of transubstantiating memory into fiction, Virginia Woolf thirteen years earlier enacted a cognate displacement of deep emotional turmoil, expressed in gesture, from daughter (the writer) to father figure (Mr Ramsay). Throughout ‘Time Passes’, the middle section of To the Lighthouse, she intercalated paragraphs in brackets that signal the dissolution of the Ramsay family in counterpoint to the progressive decay of the deserted house. The death of Mrs Ramsay is marked by the insert that in the novel’s first Hogarth Press edition of 1927 reads:

[Mr. Ramsay stumbling along a passage

stretched his arms out one dark morning, but

Mrs. Ramsay having died rather suddenly the

night before he stretched his arms out. They

remained empty.]

The passage grates somewhat syntactically. The diverse subsequent editions show various half-measures to solve the crux. In ‘Sketch of the Past’, the underlying experience remembered is rendered in these words: ‘George took us down to say good bye. My father staggered from the bedroom as we came. I stretched out my arms to stop him, but he brushed past me, crying out something I could not catch, distraught. And George led me in to kiss my mother, who had just died.’ (End of the segment dated 15 May 1939.)

5 The essay was originally written in German. I owe this version in English to the translation and advice of Dr Charity Scott-Stokes.