1. Early Mapping: The Tsardom in Manuscript

© 2017 Valerie Kivelson, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0122.01

In some ways, the maps produced in Russia from the mid-fourteenth to the early eighteenth centuries fit uncomfortably in a volume devoted to the study of information and mechanisms of communication. To a modern viewer, or even to an educated European of the early modern period, the expected cartographic formulae are distinctly lacking, replaced by colourful drawings of little houses, churches, and trees. The maps’ visual vocabulary is more pictorial than graphic, their content more fanciful than informative. Not anchored by unified perspective or scale, often without a fixed point of orientation, they show a topsy-turvy landscape of villages and forests pointing up, down, and sidewise. On first impression, these maps strike the eye as childish and naïve, a far cry from the cool abstractions that we tend to associate with cartography today. The information they contain would seem, therefore, to be minimal. As a mode of communication, early modern Russian maps were even more severely limited. Appropriately called “sketches” (chertezhi) rather than “maps” in Russian, these hand-made drawings were never printed and were not created with any view toward wide dissemination. For example, only one map of the city of Moscow was printed in Russia prior to 1741, and that was a small map included in the frontispiece to a 1663 Bible. This experiment in publication inspired no imitators.1 Rather than print and circulate maps, Russian authorities understood maps as potentially dangerous and militantly controlled their production and distribution.

Isaac Massa, a Dutch merchant who lived in Moscow in the early seventeenth century, reported that although he was eager to obtain a map of the city, he would never have dared ask for one, “because they would have quickly seized me and delivered me over for torture, thinking that in making such a request I must be contemplating treason. This people is so suspicious in this regard that nobody would have been so bold as to undertake the task”. A Russian friend explained the risk involved in sharing cartographic information, telling Massa: “I would be in danger of my life if anyone knew that I had made a drawing of the town of Moscow, and that I had given it to a foreigner. I would be killed as a traitor”.2 With this story of punitive state censorship, Massa reinforces one of the most persistent ideas about Russia, enduring powerfully until today; that is, rather than encourage the collection and circulation of information, the Russian state preferred to monopolise both of these spheres of activity and to quash communication.

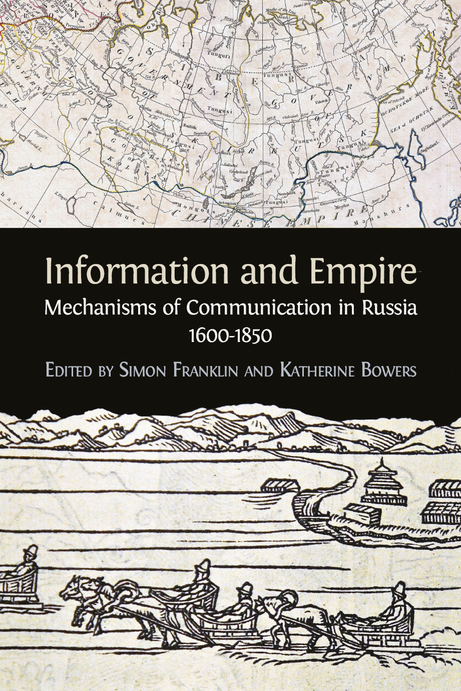

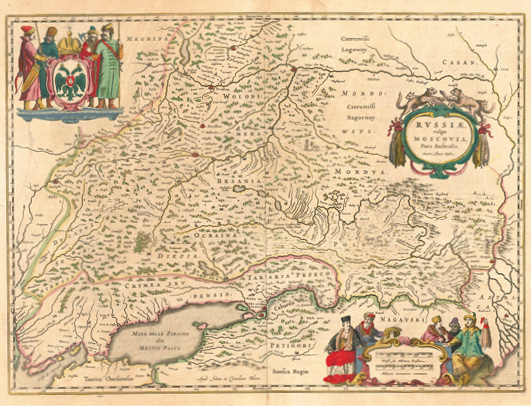

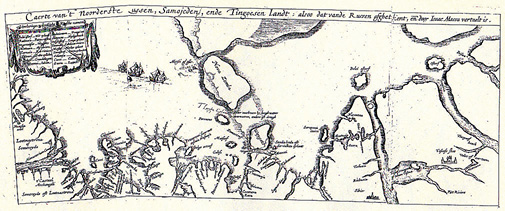

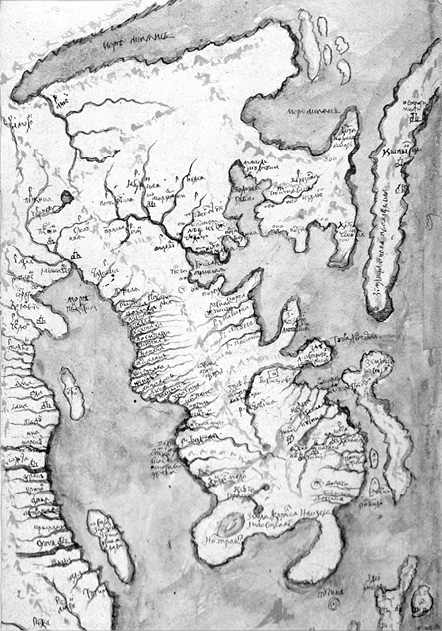

At the same time, however, Massa’s saga exposes the limits to this picture of state censorship: in spite of the obvious risks involved, Massa ultimately succeeded in gathering a good deal of cartographic information from his Russian contacts and his fellow expatriates. He even prevailed on the same fearful Russian friend to draw a map for him, though on condition of utter secrecy. The Dutchman is associated with four splendid maps of Russia: the one of the city of Moscow that his friend entrusted to him; one of the Southern regions of Muscovy reaching down to the Crimea and the Northern coast of the Black Sea; a general map of all of European Russia; and a particularly valuable one of the Northern coast of Russia and Siberia, which retained its value as a reference to this little known region into the eighteenth century.

Figure 1: Willem Janszoon Blaeu, Tabula Russiae (1635). Map and inset of the city of Moscow based on Isaac Massa’s maps.

Figure 2: Isaac Massa, Russiæ, vulgo Moscovia, Pars Australis [The Southern part of Russia, called Muscovy] (1645).

Figure 3: Isaac Massa, Caerte van′t Noorderste Russen, Samojeden, ende Tingoesen Landt: alsoo dat vand Russen afghetekent [Map of the northern-most Russian, Samoyed, and Tungusic land, as copied from the Russians] (1610).

Two of the maps of Russia most frequently reprinted in European atlases of the early modern era bear his name. Novissima Rvssiae Tabula and Rvssia vulgo Moscoviae Pars Avstralis are both clearly attributed to him: “Auctore Isaaco Massa”.3 Richly populated with Russian toponyms, the maps confirm Massa’s acknowledgement of the generous contributions of Russian informants to his sense of the local geography.

Massa was not alone in suggesting that, regardless of the fearful punishments they might incur, Muscovites and foreigners exchanged geographic information at a considerable rate. The Habsburg envoy Sigmund von Herberstein reported a parallel experience during his two visits nearly a century earlier. Unlike Massa, he was unable to convince his friends to provide him with actual maps—none would dare—but with the assistance of knowledgeable Russian and European informants, he accumulated the geographic information that made possible the publication of his map of Muscovy in copper engravings accompanying his Notes upon Russia in Vienna in 1549. In subsequent decades, the work appeared in multiple editions and translations, and adaptations of the map were included in various world atlases.4

Figure 4: Map of Moscovia, Sigismund von Herberstein (1549).

These foreigners’ travails, just two of many tales of cartographic adventure, illuminate the complexities involved in tracking the flows of cartographic information and communication in early modern Russia. Their reports demonstrate that, already by the time of Herberstein’s visits in the early sixteenth century, Muscovites had developed a strong and effective cartographic sensibility and had collected a cache of geographic information sufficient to support the production of maps. Further, foreigners recognised the value of Muscovite geographic knowledge and of the maps themselves. Russia’s pictorial sketches followed different models than the scientific survey mapping beginning to characterise European cartography in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, but nonetheless they conveyed valuable spatial information much sought after by both the tsarist state and the foreigners interested in it.5 Far from dismissing the funny little drawings, foreigners scrambled to get their hands on them, with some success. Although maps were a controlled substance and publication remained out of the question, this information circulated widely and built cumulatively on the pooled knowledge of diverse contributors.

This chapter draws on my previous work on Muscovite maps but with a quite different analytical focus.6 Where my earlier cartographic research primarily explores Muscovite political and religious culture, this chapter pursues the themes of this volume: information and communication. In this context, the following pages investigate the kinds of information conveyed in Muscovite maps, the ways the maps communicated meaning, the interplay of Muscovite and foreign cartographers and informants, and the ways these precious documents circulated in the politically charged climate of the seventeenth century, when publication was not an option.

Muscovite Sketch Maps and How to Read Them

Maps as physical artefacts, schematic representations of the world in two dimensions, are not inevitable or natural correlates of a geographic sensibility or awareness of one’s place in the world relative to other locations. Maps remained exceptional in most parts of Europe, for instance, until the fifteenth century, when they began to catch on, although the Chinese already could boast an established mapping tradition perhaps as early as the second century BCE. In Russia, researchers have discovered a single rough sketch of the layout of the compound of the Kirill-Belozerskii Monastery from the 1360s and rare mentions of maps surface in texts from the fifteenth century,7 but they do not appear to have been made with any regularity until the late sixteenth century, and they do not survive in significant numbers until the seventeenth century. When they show up, they fall into two general categories: sketches of very local terrain, drawn up to establish property lines or chart the state of military defences; and depictions of great swaths of the tsardom drafted for diplomatic, military, and strategic use. Since the local maps appeared earlier, we will begin with those and then move to the more comprehensive maps of the realm.8

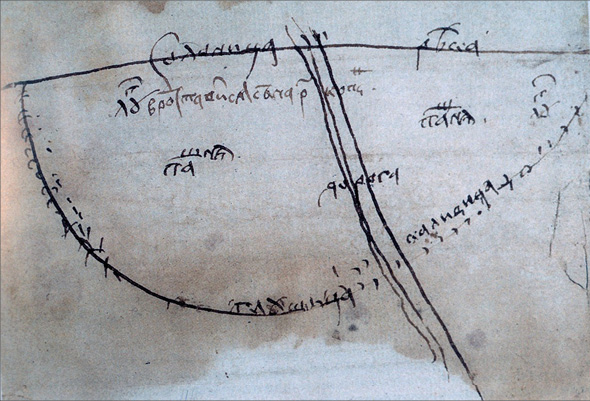

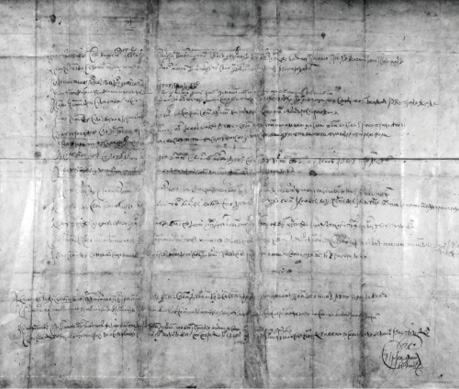

One of the very earliest surviving maps illustrates the nature of the local property maps. A few lines scratched in ink on paper documents a sale of land transacted in 1533.

Figure 5: Drawing of the Lands of the River Solonitsa.

A double line indicates a road transecting a semi-circular arable field that abuts a river. Text on the obverse side describes the purchase of the field in question by the Trinity St Sergius Monastery. Unimpressive in its degree of cartographic expertise, the sketch nonetheless conveys all the information relevant to the exchange. The drawing situates the field in question along the appropriate river (the Solonitsa) and relative to the road; it notes the positioning of fields and meadows; and it records the value of the land with a terse reference to “a crop of 100 haystacks”.9 Efficient and unpretentious, the sketch demonstrates a command of relative positioning and cartographic vision fully adequate to the needs of the moment.

Written sources record little about the early development of visual mapping, but the few early surviving mentions in official documents suggest that officials of the grand prince initiated the gradual incorporation of maps as an administrative and juridical tool and as a supplement to their abundant textual records. Fleeting references in administrative records demonstrate that the initiative came from above in pursuit of entirely practical ends. For instance, orders were sent from Moscow to provincial officials in 1534 and 1535 instructing them to study the conflicting claims of rival litigants and to send maps of the properties in question back to the authorities in the Kremlin. In the 1534 case, an order issued in the name of the grand prince (the four-year-old Ivan IV) required a local official in Beloozero Province to examine the lay of the land in connection with a suit between the same Kirillov Monastery, mentioned earlier, and two peasant brothers. He was to “sketch a map of the disputed land, and having written up his judgment and the results of his investigation truthfully and having sketched the map, report to me, the grand prince, and bring before me both of the litigants for a face-to-face [literally, eye-to-eye] confrontation”.10 Although the officials’ handiwork does not survive, they presumably produced sketch maps similar to the surviving 1533 map, the precursor of the more elaborate and numerous property litigation maps of the seventeenth century.

In the seventeenth century, and particularly the final third of that century, the production and use of maps proliferated, along with a generalised expansion of administrative record-keeping and increasingly dense webs of interaction between state officials and society. As the tsars extended their military lines to the South and East, the Chancery of Military Affairs ordered maps prepared to identify the most effective placement of fortresses. Maps were used for the extensive projects of town planning undertaken in the seventeenth century by the Muscovite state.11 Sketch maps became fairly standard elements in the lawsuits over real estate that filled the tsars’ courts. Sometimes the litigants would take the initiative and produce their own rival maps in support of their opposing claims, leaving the officers of the court to sort out the contradictions. More commonly, the courts would commission a city clerk or retired soldier, any passably literate man of good reputation, to go out to the land in question and make a map.

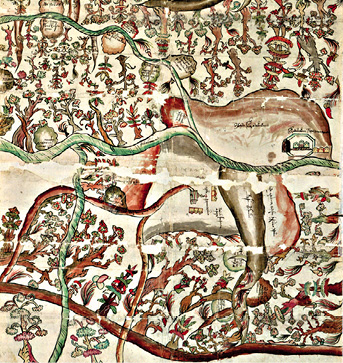

The men entrusted with the job were not formally trained in cartography, and the fruits of their labour display a variety of approaches, but they all share a pictorial vision rather than a geometric one, and a sense of orientation rooted in the embodied presence of a human passing through the landscape rather than an abstract, homogeneous, planimetric or “god’s eye” view from above. A few examples will give a sense of this embedded vision and picture-book aesthetic. A vivid map from Aleksin Province, in the far South, dated 1671, situates the viewer in space by sketching out a rough framework of rivers (in green) and roads (in brick red).

Figure 6: Map of Aleksin (1671).

Two little villages are indicated by tiny houses. One village is surrounded by a walled enclosure; a colourfully striped church distinguishes the other. Uninhabited arable fields (pustoshi) are drawn in as rounded blobs distributed unevenly along the rivers and roads, and each landmark is labelled with clarifying text. The bulk of the artist’s work, however, was devoted to filling the page with a forest of fantastic trees, painted in riotous colours.12 The trees point this way and that, most angling woozily to one side, but others radiating out from roads and rivers, following along a navigable itinerary and reflecting the vantage point of a human traveller. It places human incursions as insignificant traces within an exuberantly wooded landscape.

This lavishly decorated cartographic painting was made by or on the order of Lazar Lavrov, Governor of Iaroslav-Maloi, for the practical purpose of determining ownership of some uninhabited fields claimed by two local landholders, and yet its visual composition seems engaged with an altogether different, perhaps more fantastical or metaphysical plane. It is hard to recognise in this work of art a pragmatic piece of legal-bureaucratic documentation. Nonetheless, it is a map, and a fully serviceable one at that. Through the distracting exuberance of irrelevant and eye-catching embellishment, the mapmaker conveyed enough information about relative locations to allow the courts to decide who should rightfully control which plot of land.

Like all the sketch maps, this one lacks geographic precision and the structuring geometry that European maps of the same era would likely contain: latitude or longitude markers, grid layouts, wind roses (although it should be noted that through the sixteenth century, European map makers still oriented their maps in a variety of directions, not only with the North at the top).

Among historians of cartography, the question of orientation of Muscovite maps is disputed, with each scholar asserting his or her position with great certainty. Leo Bagrow declared authoritatively that seventeenth century Russian maps were “always” oriented to the South; V. S. Kusov noted significant variation, with the majority oriented to the East, followed by a significant minority oriented to the South, and only a few oriented to the North. S. I. Sotnikova also allowed for a degree of arbitrariness in orientation, although from a small sample she identified a preference for a Northern orientation, with a minority oriented to the South.13 As this cacophony indicates, no consensus has been achieved. That fine scholars could reach such disparate conclusions suggests that perhaps they are asking the wrong question. As medieval historian Carol Symes points out, documents can coach us in how they want to be read. Sometimes, she says, they scream out their instructions. The maps themselves tell us that they care very little about orientation. In this case, the sketch maps urge us to set aside our presumption that documents necessarily have a clear up and down, a right and wrong way of viewing them.14 They invite us instead to delight in their pictured landscape in any direction we choose, and in multiple directions at once.

This invitation is underscored by the fact that cardinal directions usually (though not always) go unmarked in the maps. More frequently, Muscovite chertezhi took their structure from the landscape itself and from the human itineraries that passed through it, orienting more to the courses of major rivers or paths of important roads than to abstract compass points. This is not to suggest that Muscovites had no understanding of the cardinal directions, quite the contrary, but rather to note that they chose not to indicate them in any way on their maps. The makers and viewers would have had no difficulty knowing which way was North.15 Still, many of the maps would have presented them with the same conundrum we face in trying to resolve how they were meant to hold the map, in other words, which way was up.

The polyphonic impulses of the mapmakers come through when one attends to the visual evidence of the maps themselves, with their jumble of orientations of images and textual annotations. The point of view of the traveller along the road is signalled by the trees bristling outward; the horizontal span of the paper accommodates the flow of a river; the layout of a village around a nodal focus such as a church or a path determines the splayed depiction of houses with their roofs pointing out from the centre. Mixed perspective presents architectural complexes from multiple viewpoints simultaneously, suggesting the movement of the human viewer around the walls of a building or compound.16 The visual impact of mixed perspective is augmented in large maps, where the artists or scribes faced the purely logistical problem of the limited reach of the human arm. Oversized maps composed of multiple sheets glued together required the mapmaker to circle around and work from different sides of the paper.

It is true that sometimes the artefacts themselves provide clues to their intended orientation. Occasionally, maps make some effort to indicate direction themselves by the placement of the rising or setting sun, as in a lively map of Borovsk, where a summer sunrise to the right and a summer sunset to the left indicate a Northern orientation.17 Some sketch maps, particularly the small ones contained on a single piece of paper, declare an unambiguous directionality by showing all the trees pointing in a single direction consistent with all the text. Others show a preponderant orientation, with most of the trees and text pointing in a single direction. Signatures collected from local witnesses, or from the mapmaker himself, may appear on the back of a map to add to its veracity and documentary power, and Leonid Chekin stresses that they march along the back of the page in horizontal lines, obeying a disciplined sense of up and down.18

Figure 7: Signatures on obverse of a map of lands along the Kamenka and the Urshma rivers in Suzdal Province. The signatures are aligned horizontally across the page, indicating a clear orientation for viewing. The document dates to 1688 or 1689.19

This is sometimes the case (in other cases signatures run every which way), but did that regulated linearity on the back determine how Muscovites read the looser structures of the pictorial front?

These highly localised sketch maps were not concerned with situating their position in a broader world, relative to an abstract pole, an international border, or a metropolitan centre; that was not their purpose. They were created to illustrate the location of a great double-headed pine with a state agent’s official boundary mark or blaze, a dark X, burned into it, or the place where a church used to stand or a graveyard lay in ruins, in order to clarify particular property lines.20

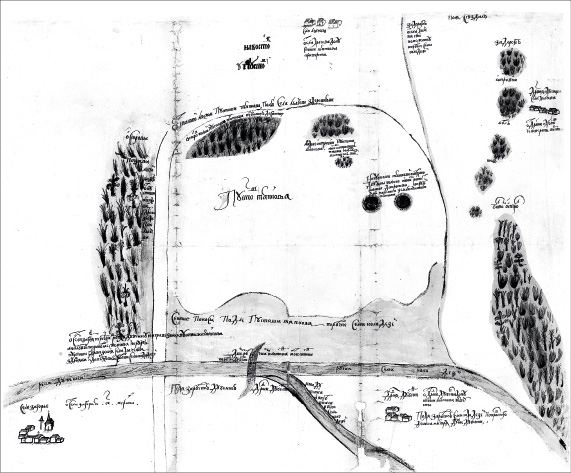

Figure 8: Map of the lands along the river Lakhost near the village of Tolstikova in Suzdal Province. The sketch documents the mapmaker’s concern with the details of the local landscape and the official markers that register property lines. It demonstrates little concern with orientation or with situating the local in a broader world.21

The particularity of their focus is evident in the plethora of minuscule details that they record. On a map from Iurev Polskoi from 1672, a textual label above the two dark circles just right of centre notes: “In the uninhabited arable field Tiapkova are two pits, and raspberries and nettles are growing in them, and around them is the ploughed land of the uninhabited arable field Tiapkova”.22

Figure 9: Map of the land along the river Sem Kolodezei in Iurev Polskoi Province, 1670-72. “The ploughed land of the uninhabited arable field Tiapkova”. Like the previous map, this one focuses exclusively on local landmarks.23

These were the facts that would determine the outcome of a case and would allow the tsar’s officials to resolve questions of boundary lines and ownership claims. The idiosyncrasies of the local landscape served the purpose far more usefully than did any abstract, generalised orientation. Modern scholars may be convinced they know the “right” way to orient these maps, but in their handiwork, seventeenth-century mapmakers show themselves to have been supremely uninterested in the question.

The sketches may have served their purpose in helping judges to issue their rulings, but that does not necessarily mean that the information they provided was accurate. A colourful sketch map drawn up in connection with a dispute over property in the neighbourhood of Borovsk, a town to the Southwest of Moscow, provides surprising evidence in support of the claim that these amusing little pictograms conveyed locations quite reliably.

Figure 10: Borovsk.24

The map shows a network of implausibly sinuous rivers snaking through the region. Oversized vegetation edges the rivers. Little houses line the roads and nestle in small settlements. All in all, it looks again like an illustration from a book of folk motifs rather than a document capable of conveying practical information.

Yet, as Chekin points out, a close comparison with a satellite photo available through Google Earth proves that our man in Borovsk knew his business.

Figure 11: Borovsk, satellite view from Google Maps (2017).

The topography of the region and the location of identifiable landmarks line up with an impressive degree of accuracy. Chekin deduces that the mapmaker began with the town of Borovsk as his main point of reference and then worked his way through the region, dividing the territory into “manageable segments”, and then using the intricate grid of rivers and roads to “further subdivide the area”. He placed landmarks close to Borovsk quite accurately, while places farther afield, presumably less immediately relevant to the task at hand, were placed in the general vicinity of their actual location.25 Untrained in Western scientific cartographic practices, unacquainted with the techniques of mathematical surveying, the Muscovite men who were haphazardly rounded into service as mapmakers nonetheless succeeded remarkably well in putting on paper usable guides to the natural and built landscape they inhabited.

State Mapping Projects: The Great Sketch Map and Atlases of Siberia

If Muscovite mapmakers could capture the fine-grained topography of small areas, how did those working on a larger canvas fare? For maps of the tsardom writ large, two major sets of sources survive: a set of documents related to the Book of the Great Sketch Map (Kniga Bol′shomu chertezhu); and a sizable collection of maps of Siberia composed from the 1660s through to the early 1700s.26

At the very end of the sixteenth or beginning of the seventeenth century, Tsar Boris Godunov ordered the production of a great map, the Bol′shoi chertezh, of the lands of the tsardom to the West of the Urals. In preparation, reports were sent to Moscow from the localities, drawing on local informants with knowledge of the major landmarks, rivers and roads, forts, lookouts, wells and supply-points. The welter of strategic information was collated into a single book, the Book of the Great Sketch Map. From the reports, regional maps were drawn up and then pasted together into a single huge wall map. By 1627 Kremlin scribes reported the original map was “dilapidated, it was no longer possible to see landmarks on it, it was all worn out and falling apart”.27 To address the problem, in that same year Tsar Mikhail Romanov commanded his scribes to make a copy of the book and to recreate the map itself on the basis of the information it preserved. He added that a supplemental map should be made showing the territories to the South, the Ukrainian borderlands and the dangerous routes that the Tatars followed to and from the Crimea. The new Great Sketch Map seems to have followed its predecessor to oblivion, but the map of the Ukrainian lands survives in multiple later copies made by foreigners and circulated abroad.

This brief history of the fate of the Great Sketch Map further supports the notion that neither Moscow’s protective monopoly on cartographic information nor its preference for manuscript over printed formats precluded active use or even dissemination. The map had been consulted frequently in the Kremlin chanceries, becoming dog-eared and faded through constant use. It had passed through many hands in the decades since it was compiled.28 Further, we know the sketch map of the Ukrainian lands from copies made and circulated outside of the tsardom by Germans and Swedes. Their ability to find and copy such a strategic and closely held asset demonstrates beyond a doubt that, however much the Kremlin wished to hoard its cartographic information, the pressures of dissemination were greater. Classified information leaked out, then as now, and the forces of communication overrode the pressure for secrecy.29

Similar dynamics emerge in the arc of Siberian mapping. Muscovites first crossed the Ural Mountains and clashed with the Tatars of Western Siberia in the early 1580s, under Ivan IV. Half a century later, they had reached the Pacific Ocean. As they explored, conquered, and attempted to exploit and rule the populations and resources of their vast new holdings, they recognised the importance of mapping the terrain. They had little cartographic tradition to build on in Siberia.

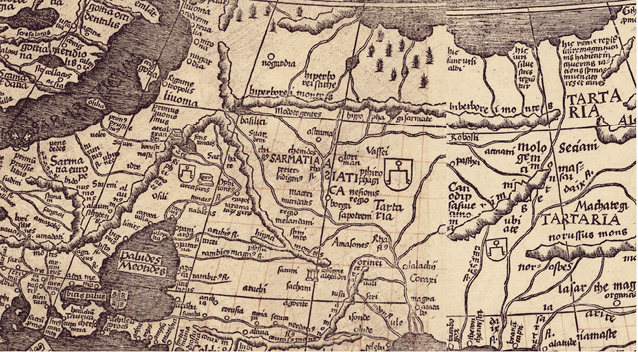

The Eastern reaches of Eurasia had appeared on European world maps since the revival of Ptolemaic geography in the early fifteenth century.30 Martin Waldseemüller’s famous wall map, Universalis Cosmographia of 1507, for instance, labels both “Tartaria” and “Sarmatia Asiatica”, though not Muscovy, in its largely fanciful sweep across the continent to the Pacific. A Ptolemaic framework and a set of classical toponyms still shaped Waldseemüller’s vision of Eurasia, even though he knew they were outdated and despite his pioneering revision of the world with his inclusion of America, the land of Amerigo Vespucci, as a new and separate continent.

Figure 12: Martin Waldseemüller, Universalis Cosmographia (1507), detail. The Hyperborean Mountains run horizontally across this section of the map. “Paludes Meotides,” at the bottom left, is an oversized Sea of Azov.

As Katharina N. Piechocki points out, the classical misconception about the Riphean and Hyperborean mountain ranges that purportedly ran East-West across the narrow belt of land imagined as the limit of the earth to the North of the Black Sea remained in place until dispelled by the Polish scholar Maciej Miechowita in his 1517 Tractatus de duabus Sarmatiis Asiana et Europiana, “the first European treatise to overtly challenge the existence of the Riphean mountains”. Countering ancient mythology with up-to-date reports, Miechowita declared, “We know for certain and have seen that the Hyperborean, Riphean, and Alan mountains do not exist”.31

Miechowita stresses the corrective power of first-hand, eyewitness accounts, and the maps produced by Europeans in the following centuries benefited from precisely this kind of information, drawn together from the travel reports of foreign merchants and envoys and from conversations with geographically savvy Russians. In the geographic descriptions in his Notes Upon Russia, Herberstein acknowledged the crucial information divulged by Russian contacts. For instance, under the rubric “The Navigation of the Frozen Ocean”, he noted that when he was at the court in Moscow, “there happened to be there Gregory Istoma, the interpreter of that prince, an industrious man, […] and as he had been sent by his prince in the year 1496 to the King of Denmark, [….] he gave me a short account of his journey”.32 On the basis of many such reports, once back at home, Herberstein commissioned a map of Muscovy. A form cutter named Augustin Hirsvogel produced an early version in 1546. It was reprinted in 1549 in a smaller format to accompany the first edition of Notes Upon Russia, and from there it “went viral”, enjoying an active afterlife in subsequent editions and reprintings in atlas compilations.33

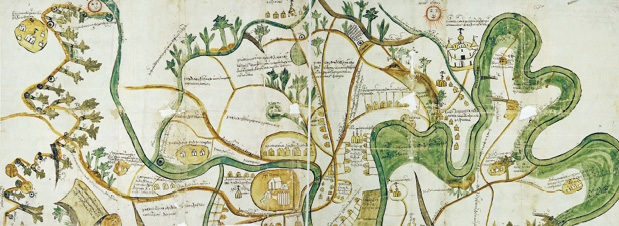

Herberstein was one of the early contributors to a sixteenth-century boom in European mapping of Muscovy and Western Siberia, generally designated Tartaria or Asian Scythia.34 Muscovites contributed to this boom by sharing geographic information with their Western acquaintances, but in their own cartographic work, they adopted a distinctive approach. As Alexey Postnikov and Marvin Falk write, “the early charts of the territories of Siberia and the Northeastern regions of Eurasia produced cartography outside the Western European scientific framework of the time. Even in their appearance the Siberian charts of the seventeenth to early eighteenth century sharply differed from contemporary maps created within Ptolemy’s paradigm that was then dominant in European geography”. Visually distinctive in style, often oriented to the South rather than the North, and sometimes composed with the help of compass readings and chain measurements of distance, but without the benefit of a “geographic net and consistent scale and projection for all parts of the cartographic image”, these Russian maps were nonetheless packed with valuable information and accompanied by textual descriptions that filled in additional context.35

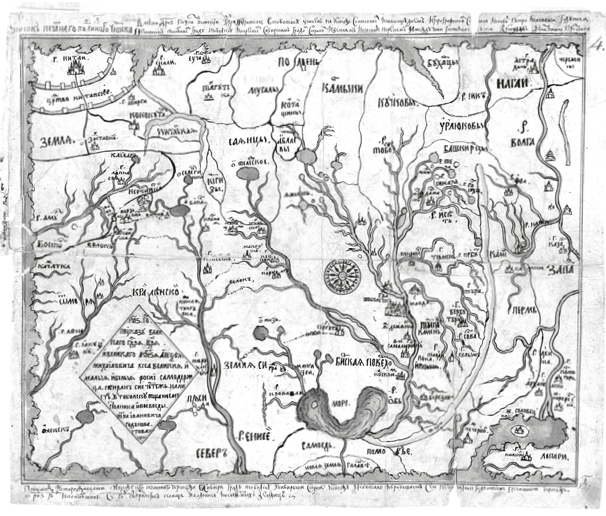

The first map of all Siberia known to have been made within the tsardom by Russians is known as the Godunov map of 1666–67. As with the maps produced in conjunction with the Book of the Great Sketch Map, the Godunov map itself does not survive or has not yet been found, but its imprint is detectable in later renditions, drawn by Russians following in Godunov’s tradition and by foreigners who copied it in secret. A textual lozenge appears on later copies informing the viewer that the map was made “In the year 1666–67 by order of Great Sovereign, Tsar, and Grand Prince Aleksei Mikhailovich, Autocrat of all Great, Small, and White Russia” and composed “with great care” by Governor Petr Ivanovich Godunov from information collected in Tobolsk, the capital city of Western Siberia.

Figure 13: S. U. Remezov’s copy of the Godunov map of 1666–67, from his Chorographic Sketch Book. The map is oriented to the south: China is indicated by concentric curves of the Great Wall in the top left corner and the Pacific Ocean frames the map at the left margin. The Arctic Ocean runs along the bottom.

Along with the textual cartouche, the surviving copies include a compass rose, underscoring the use of this directional technology in the map’s composition. Named for this Siberian administrator (and not the more famous Tsar Boris Godunov), the map reflects the governor’s on-going work with maps. In 1661 Godunov oversaw the construction of fortifications along the River Tobol, following “a map and description provided by well-informed people”.36 The input of “well-informed people” contributed to this first map of all of Siberia as it had for the mapmakers back in central Russia as they laboured to sketch the bounds of landholders’ estates by drawing on the expertise of “long-time residents”.37

Given the crudeness, in terms of scientific measurement, of Godunov’s sketch, one might wonder why foreigners would take the risks involved in attempting to purloin copies. The answer points precisely to the nature of the information it conveyed and the value that contemporaries put upon it. Knowledge of river routes and linkages offered the key to travel and transportation. Henry R. Huttenbach explains the simplicity of the map’s content and the emphasis on rivers to the exclusion of other features of the landscape: “For the most part these chertezhi resemble road maps that show points of interest on or near the road. What lies off the highway is not shown; similarly the chertezhi of Siberia virtually ignore the interior other than in terms of the course of the river”.38

The same hydrographic grid characterised the work of the extraordinary Siberian cartographer of the end of the seventeenth and beginning of the eighteenth century, Semen Ulianovich Remezov.39 In creating his three atlases and many maps of Siberia, Remezov drew on the same kind of pooled knowledge that had allowed his predecessors to chart the territory. He was responsible for drawing the earliest surviving Russian copies of the 1666–67 Godunov map, and he laboured to update and enrich it. A mid-level servitor, icon-painter, and administrator in Tobolsk, Remezov fulfilled increasingly ambitious orders from Moscow to map first the region around Tobolsk, then a broader swath of the surrounding steppe, and finally, in 1698, to create a new map of all of Siberia. In order to do so, he was to explore and map on his own, and he did so extensively, noting “directional measurements from a compass”,40 but he was also instructed to gather reports and maps from anyone who might have useful knowledge. His own explanation of his work acknowledges that maps and reports came to him from all over, from Russian and Cossack trappers and traders, explorers and adventurers, from military men, and from native peoples. He questioned travellers about their journeys to determine “the dimensions of lands, the route distances of towns and their villages and districts, about rivers, streams, lakes, bays, islands, and fishing, about mountains and forests, and about all landmarks that have not been plotted on previous maps”.41

As his preface to the Working Sketch-book (Sluzhebnaia chertezhnaia kniga Sibiri), one of his three atlases of Siberia, explains, he and his sons were ordered by the head of the Siberian Chancery to compile their atlas from “pictures of twenty-three Siberian towns brought to the Siberian Chancery in Moscow”. In the Chorographic Sketch-book (Khorograficheskaia chertezhnaia kniga) he explains that he used “many town maps, whatever had been sent over the years to Moscow”.42 Remezov, thus, did not work in isolation, and the resulting atlases are as much cobbled together from earlier Muscovite efforts as representative of his own, individual inspiration.43 Notably, all of these varied people had sufficient geographic interest and cartographic understanding to make important contributions to the Siberian mapping project, and the state and its delegates recognised the value of their knowledge. Some of Remezov’s maps acknowledge his sources by name; others simply draw on the reports that flowed into Moscow and Tobolsk. The first map of Kamchatka, commissioned by the governor of Iakutsk, Dorofei Traurnicht, and brought back by the intrepid explorer and vicious conqueror Vladimir Atlasov, made its way into one of Remezov’s atlases, with full attribution.44

Figure 14: Kamchatka. Map of Kamchatka included in S. U. Remezov’s Working Sketch Book. Remezov attributes the map to Dorofei Traurnich.

In his depiction of the hydrographic features of the Far East, Remezov drew on information provided by Nicolae Milescu Spathary (or Spafarii), who described and mapped the Sino-Siberian frontier in the course of a diplomatic mission to China in 1675–76 on behalf of the Muscovites.45 Spafarii’s work in turn relied heavily on the work of Jesuits, from whom he freely plagiarised, as well as on Chinese, Kazakh and Manchu informants. As Gregory Afinogenov writes, “These texts were the product of networks ensnaring Junghars, Kazakhs, Mongols, Manchus, Chinese, and even the Jesuits themselves, and as such reveal the delicate interdependencies and striking human stories that characterized Russia’s presence in this borderland”.46

With all of these streams of information flowing into his workshop in Tobolsk, Remezov and his assistants were able to create a far more densely annotated version of the Godunov map that identified hundreds more Siberian locales and refined his sense of geography, culminating in his large, stand-alone Map of All Siberia.

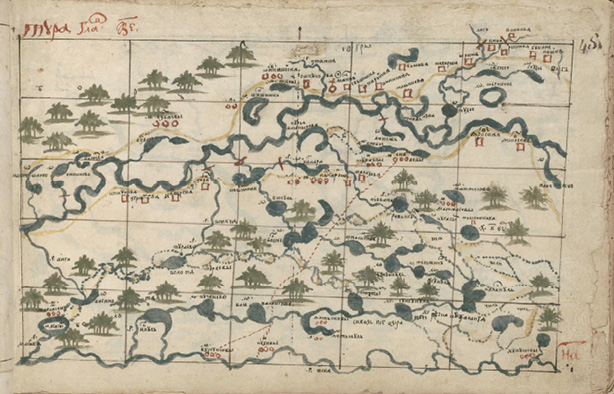

Figure 15: Remezov, Map of All Siberia.

In the bulk of his work, he followed the same general template as that used in the local real estate maps. He employed the branching network of rivers and mountains to provide the basic scaffolding, and then introduced pictorial elements to indicate Russian cities, fortified outposts, native settlements, and natural features of the landscape. Remezov abjured use of scale or precise direction, providing instead a functional itinerary, indicating which river to follow and which branch to take to a specific endpoint. Annotations on the maps augmented their practical application. Distances between set points might be indicated in versts47 or days and nights. Travel between one outpost and another would take three days by ship or ten days on land. Travel to another destination would take a week by river and would be impossible by land. Although Remezov’s atlases were not published until centuries later and survived as unique exemplars, he created them with the idea that they could be of practical use to travellers crossing Siberia’s endless landscape. In the terms of this volume, although it is difficult to trace direct avenues of communication and dissemination, his hand-drawn atlases nonetheless both drew on and influenced a lively Eurasian exchange of critical geographic information.

Circuitous Borrowing: Information Flows and Communication in the Clandestine World of Early Modern Cartography

The familiar themes of cartographic secrecy and clandestine exchange that we have encountered before run through the story of Siberian mapping as well. The Godunov map, for instance, survives not only in the multiple copies by Remezov but also in at least three separate copies smuggled out by foreign diplomats. A recent book by Postnikov and Falk catalogues the circulation of the Godunov map through unlawful back channels. Lieutenant Colonel Fritz Cronman, Swedish ambassador to Muscovy, purloined a copy when he was in Moscow in February 1667. Cronman wrote to his monarch, Charles XI, “The map of all these Siberian lands up to China, which recently was sent here on His Majesty’s orders by Tobolsk commander Godunov, was shown me and having received permission to keep it over night, I copied it”. Cronman’s countryman Claes Johanssen Prytz made another copy. In his report on his mission, Prytz wrote, “The appended land map of Siberia and adjacent lands I copied 8 January 1669 from a poorly preserved original which was loaned to me for a few hours by Prince Ivan Alekseevich Vorotynskii on the condition that I may examine it but under no circumstances copy it”.48 The report makes one wonder if the prince issued his warning with a knowing wink, creating for himself a cover of plausible deniability.

The Swedes were particularly assiduous and particularly successful in their efforts to obtain secret cartographic documents, but they were not the only ones who reported access to the Godunov map. Nicholas Witsen, a Dutchman with extensive experience in Moscow and with highly placed contacts at court, also obtained a copy of the Godunov map, together with a map of Novaia Zemblia, from one of those Kremlin insiders. Witsen with some pride wrote that he had “assembled volumes of diaries and notes in which are the names of mountains, rivers, cities and towns, together with a magnitude of drawings executed by my order”.49 In 1991 Postnikov identified the Carte générale de la Sibierie et la Grande Tartaria, a French map in the collection of the Newberry Library in Chicago, as a copy of a Russian original drawn in the mode of the Godunov map, dating to the late 1670s or early 1680s.50

The spiral of creation and copying, the back and forth between Russians and foreigners, continued apace throughout the century. An updated version of the Godunov map enjoyed a similar international transmission. Postnikov and Falk say this map was composed under the auspices of Metropolitan Kornelii in Tobolsk in 1673. It bears a close resemblance to Remezov’s Map of All Siberia, although the dynamics of the relationship remain unclear. It survives in at least three copies. The sole extant Russian version has annotations in both Russian and Latin, suggesting the cooperation of locals and foreigners. The Swedish representative Eric Palmquist managed to make a copy in that same year, as did his countryman Johann Gabriel Sparwenfeld, another Swedish chargé d’affaires who spent time in Moscow as part of a later mission. Palmquist collected a valuable set of documents pertaining to Russia, “among them sixteen geographic maps and plans of cities, including the general Siberian charts of 1667 and 1673”. He echoed the earlier reports of the covert nature of his work, stressing the “effort and difficulties” involved, and he wrote that “I personally observed and drew maps in various places, risking my life, and also received information from Russian subjects in return for money”.51 The foreigners’ reports confirm both the obstacles and the possibilities of obtaining maps and geographic information from Russia, and incorporating that knowledge into their own pictures of the world.

Adding more evidence of covert borrowings and circulation, Bagrow identified a German manuscript map entitled Abzeichnung der gantzen Nord- und Ost- gegend von den Moschovischen grentzen durch Sibirien biss zu dem grossen Reich Kitai sonst China at the Westdeutsche Bibliothek, Marburg/Lahn, as a copy of Remezov’s Map of All Siberia, indicating another mysterious incident of copying and transportation, perhaps smuggling, of this hand-drawn translation.52 All of these cloak-and-dagger escapades show that the highly classified Godunov map and its later derivatives were hotly sought after in Europe. In spite of the close guard kept on the manuscript exemplars, maps of Siberia escaped the confines of Muscovite control and circulated in a broader world of cartographic information.

Information flowed in multiple directions. At the same time that Europeans obtained classified maps through subterfuge, bribery, and friendship and set them loose in manuscript and in print abroad, Muscovites followed developments in Western cartography with considerable interest. The tsars’ libraries and those of the Diplomatic and Siberian Chanceries acquired editions of the first world atlases published by Abraham Ortelius and Gerhard Mercator in the late sixteenth century and the somewhat later (first edition 1635) atlas produced by the father-son team Willem and Joan Blaeu, along with editions of Miechowita and other works imported from Poland. Appetite for geographic compendia was apparently not confined to the court. From the 1630s on, atlases became among the most popular and widely copied translated texts in Russia. Partial translations into Russian of several European “cosmographies”, geographic histories of the world, demonstrate significant interest in keeping up with Western scholarship and technology, although most were left incomplete and none were published in the seventeenth century.53 Omissions and amendments, particularly in the sections devoted to Muscovy itself, demonstrate active engagement with these imported sources. The first four volumes of the Blaeu atlas were translated from various editions into Russian between 1655 and 1657. According to N. A. Kazakova, the section on Muscovy is left as blank pages in Russian translations of Blaeu, suggesting that the treatment of the motherland required special consideration and was perhaps a bit too hot to handle.54

The path of borrowing zigzags between Russia and Europe, with each iteration informing subsequent productions. Herberstein’s story epitomises the dizzying geographic and cartographic exchanges that characterised this period. Herberstein, the Habsburg envoy, drew on information provided by a Russian court translator (Gregory Istoma), a Russian diplomat (by the name of Dmitrii Gerasimov), and a defector from Muscovy to Lithuania (Ivan Liatskoi) among others. Their reports informed Herberstein’s geographic account and dictated the contours of the map cut by Augustin Hirsvogel in Vienna. Mercator’s atlas, which incorporated Herberstein’s description of Russia along with his map, brought the Habsburg envoy’s impressions back to Muscovy, where they would resonate in Russians’ self-descriptions and serve as a source of information about their own religion and practice for centuries to come.55

The case, I hope, has been made here that, despite the apparent paucity of cartographic information of any scientific or utilitarian value, the inherent limits on communication in a manuscript culture, and the deliberate obstruction of knowledge transfer, actual practices of mapping and flow of information overturn those initial assumptions. From the sixteenth century onward, Russians and Europeans participated jointly in an energetic exercise in collecting, recording and circulating practical geographic knowledge and maps.

Remezov’s Maps: Information, Exchange, and the Strategic Value of Russian Chertezhi

As a closing example, I return to Semen Remezov, the Siberian cartographer who worked in Tobolsk in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century. He has been described as the last great representative of a purely Muscovite cartographic tradition, the “swan-song” of an uncontaminated indigenous Russian cartography.56

Yet Remezov exemplifies the very pattern of ecumenical collection and dissemination of information that we have traced to this point. Enjoying one of the very first state-funded research leaves in Russian history, Remezov benefited from exposure to Western publications during the three months he spent in Moscow studying imported European maps and cosmographical atlases, mostly of Dutch provenance, in the archives and libraries of the Kremlin. He appreciated all that he learned, and once back in Tobolsk, he penned enthusiastic descriptions of the wonders of the magnetic compass, of the linear scale, and of the all the “clever sciences” on offer in Europe.57 He tested his skill in reproducing foreign maps, creating splendid copies by hand. In one atlas he included a copy of Blaeu’s 1635 “Tataria sive magni Chami imperium”, complete with longitude and latitude lines, camels and turbaned Muslims in the cartouches, and devils and dragons populating the “Lop Desert” just outside the Great Wall of China. He also copied a Polish map, probably a version of Anthony Jenkinson’s 1562 map, complete with its Polish title and an image of the mythological Zlata Baba, Golden Woman, in the far Northeast corner.58 Marina Tolmacheva notes wryly that Remezov’s goal in copying these European maps of Siberia was “to present the state of knowledge prevailing elsewhere, which is frankly estimated at nemnogo (‘not much’)”.59

In spite of his familiarity with the latest cartographic works from Amsterdam and elsewhere, Remezov maintained many of the techniques familiar from the Russian mapping traditions examined here. Although Remezov’s small scale maps of large territories were usually oriented to the South with cardinal directions noted in the Western style, Daniel C. Waugh observes that his “large scale, detailed [maps]… most often were oriented to take full advantage of the largest (horizontal) dimension of a rectangular sheet of paper. This enabled him to follow rivers along their entire length, for indeed, as with the Book of the Great Map, the basic structure for what we might term Remezov’s practical or functional maps and atlases was river routes”.60 Almost any page from his Khorograficheskaia chertezhnaia kniga, an atlas of sketches of small sections of Siberia, exemplifies this observation nicely. A map of a segment of the Tura River, for instance, accommodates the rivers to fit to the horizontal width of the page.61

Figure 16: Map of a segment of the Tura River, from S. U. Remezov’s Working Sketch Book.

The paper is marked with a grid, but one used to guide the artist rather than to indicate scientifically measured position.

“Even though Remezov’s maps were not composed according to the rules of Western-European cartography”, Kees Boterbloem writes, “their exquisite rendering of Siberia made it undoubtedly much more feasible to traverse its vastness for travellers and to asses the extent of their domination for Russian administrators”.62 Remezov’s approach was pragmatic and suited to communicating important information about relative location.

The state agencies in Moscow understood the value of the maps of Siberia that Remezov produced, and they hounded him to send them the products of his work. Foreigners also tried to secure copies for publication in the West. The manuscript original of his Sketch-book of Siberia (Chertezhnaia kniga) testifies to this shared interest. All the labels appear in both Russian and Dutch. Most scholars agree that Dutch was added under the auspices of Andrei Vinius, the Russian-born son of a Dutch merchant, who served the tsarist state in various important capacities: as a diplomat, as postmaster, as head of the Apothecary Chancery, and, most relevant, as head of the Siberian Chancery. Vinius likely worked with Remezov to prepare the Sketch-book for publication abroad, but the plan never reached fruition. Various scenarios have been proposed: Vinius intended to smuggle the atlas out of the country but was caught, or, alternatively, he had a licence to publish it abroad.

In a study of Vinius, Botterbloem suggests a different reading: “one wonders whether Vinius was annotating the maps to dispatch a Dutch copy to [his second cousin, the Dutch statesman, merchant, and scholar Nicholaes] Witsen, in order to help his cousin fine-tune the second edition of his Noord- en Ost-Tatarien”.63 Witsen had published his own treatise on Muscovy and Tataria, this same Noord- en Ost-Tatarien, in 1690, including a map, probably modelled on originals by Remezov, Vinius, or both. As presented by Witsen, the map maintains a Muscovite Southern orientation but adds for the first time a geographic grid, though still one that is purely symbolic rather than carrying geodesic meaning.64

If we follow the path of borrowing and circulation further, it grows even more tortuous. Bagrow describes a head-spinning circuit of exchange and transmission, syncopated with blockages and censorship, around the publication of these late-seventeenth-century Siberian maps. In 1698, Bagrow tells us, Vinius befriended the Austrian ambassador to Moscow, Gvarienti, and in September of the following year, Vinius sent Gvarienti a map of Siberia, presumably his own or one of Remezov’s, with the proposition that his friend should publish it. The plan came to naught, and a few years later, Vinius was convicted of accepting bribes and fell from grace. Bagrow intimates (on the basis of nothing more than coincidental timing) that his disgrace may have had something to do with the Remezov atlas that he had so assiduously patronised and then annotated.65

The whirl of names and whiff of scandal that cling to Bagrow’s description confirm the central findings of this survey of early Russian maps. Neither the restrictive regime of secrecy nor the fact that Muscovite maps existed only in manuscript form prevented the circulation of geographic knowledge. Moreover, despite the absence of advanced scientific measurement techniques, Muscovites commanded significant knowledge of their tsardom’s terrain. However naïve in rendition, Muscovite chertezhi, on both local and grand scale, were rich in valuable geographic information, and, as such, became tactical assets, objects of forbidden desire. They were sought after, bought, smuggled, adapted, and published abroad, while Muscovite mapmakers in turn incorporated foreign geographic ideas into their own work, participating in a vibrant web of information exchange.

The history of mapping in early modern Russia shows a state “more rather than less open to foreign infiltration, more rather than less tolerant of cultural hybridity and textual circulation”.66 Intensely interested in geographic and ethnographic knowledge, Muscovites gathered, recorded, sorted, and mapped information cobbled together from multifarious sources, ranging from their own active observations and measurements, to reports from an international cast of interlocutors, to published treatises. Their communication network ranged from China to England, and swept in any potential informants in between. Communication, as is its wont, went in all directions. The secretive Muscovite regime, despite its efforts at controlling the message, participated in a world of lively exchange of information. As Afinogenov aptly observes, “Muscovy still has the ability to surprise us, both with the unexpected inventiveness of its intelligence-gathering practices and with the unintentional—and eagerly-exploited—porosity of the apparatus that was meant to keep them secret”.67

1 Simon Franklin, ‘Printing Moscow: Significances of the Frontispiece to the 1663 Bible’, Slavonic and East European Review, 88. 1/2 (2010), 73–95, esp. pp. 93–94.

2 The map drawn by Massa’s friend survives and is reproduced from the manuscript in G. Edward Orchard’s English translation of Massa. Isaac Massa, A Short History of the Beginnings and Origins of These Present Wars in Moscow under the Reign of Various Sovereigns down to the Year 1610, trans. and intro. by G. Edward Orchard (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1982), p. 130.

3 Although Leo Bagrow suggests that none of the maps were actually Massa’s work: A History of Russian Cartography up to 1800, ed. by Henry W. Castner (Wolfe Island, ON: The Walker Press, 1975), pp. 51–58.

4 Leo Bagrow, ‘The First Russian Maps of Siberia and Their Influence on West-European Cartography of North East Asia’, Imago Mundi, 9 (1952), 83–95; A. V. Efimov, Atlas geograficheskikh otkrytii v Sibiri i v severo-zapadnoi Amerike XVII–XVIII vv. (Moscow: Nauka, 1964), pp. vii–viii; Carl Moreland and David Bannister, Antique Maps: A Collector’s Guide, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Phaidon Christie’s, 1989), p. 238; A. V. Postnikov, Karty zemel′ rossiiskikh: ocherk istorii geograficheskogo izucheniia i kartografirovaniia nashego otechestva [also in English as Russia in Maps: A History of the Geographical Study and Cartography of the Country] (Moscow: Nash dom and L’Âge d’Homme, 1996); A. I. Andreev, ‘Chertezhi i karty Rossii XVII v., naidennye v poslevoennye gody’, Trudy Leningradskogo otdeleniia Instituta istorii AN SSSR, no. 2 (Leningrad: AN SSSR, 1960), 88–90; W. E. D. Allen, ‘The Caspian’, in The Hakluyt Handbook, vol. I, ed. by David B. Quinn, issue 144 (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 1974), pp. 168–175.

5 Of course, pictorial mapping was never eradicated in Western Europe or elsewhere, but in the context of official, state mapping or publication, scaled survey mapping became the norm in most places by the seventeenth century. See for instance, discussions and illustrations in Roger J. P. Kain and Elizabeth Baigent, The Cadastral Map in the Service of the State: A History of Property Mapping (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992); Peter Sahlins, Boundaries: The Making of France and Spain in the Pyrenees (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1989).

6 Valerie Kivelson, Cartographies of Tsardom: Maps and their Meanings in Seventeenth Century Russia (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007).

7 Entsiklopediia russkogo igumena XIV–XV vv. Sbornik prepodobnogo Kirilla Belozerskogo. Rossiiskaia Natsional′naia Biblioteka, Kirillo-Belozerskoe sobranie, no. XII, ed. by G. M. Prokhorov (St Petersburg: Izd. Olega Abyshko, 2003), pp. 19–26; map on p. 19.

8 Maps on icons form a subset of local maps beginning in the late sixteenth century. I will not address these fascinating maps here, but they are discussed in V. S. Kusov, Kartograficheskoe iskusstvo Russkogo gosudarstva (Moscow: Nedra, 1989), pp. 43–56. On the history of early mapping in Russia, see Leonid A. Gol′denberg, ‘Russian Cartography to ca. 1700’, in The History of Cartography, vol. 3, pt. 2, Cartography in the European Renaissance (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), pp. 1852–1903. For a valuable catalogue of Russian maps with important commentary, see: V. S. Kusov, Chertezhi zemli russkoi XVI–XVII vv. (Moscow: Russkii mir, 1993).

9 First reported by S. M. Kashtanov, ‘Chertezh zemel′nogo uchastka 16 v.’, Trudy Moskovskogo gosudarstvennogo istoriko-arkhivnogo instituta, vol. 17 (1963), 429–36; reproduced in high quality colour in Postnikov, Russia in Maps, pp. 11–12.

10 Sanktpeterburgskii filial Instituta rossiiskoi istorii RAN, coll. 41 [Collection of N. Golovin], no. 56. A second order to draw up a map was sent to the same official the following year. Ibid., coll. 41, no. 57. A copy of the same document is preserved in the Russian National Library, in a Kirillov copybook: Rossiiskaia Natsional′naia Biblioteka, St Petersburg, Manuscript Division, the Collection of St Petersburg Spiritual Academy [Dukhovnaia Akademiia], A. I/16, fol. 495–495v. I am grateful to M. M. Krom for these citations.

11 A. P. Gudzinskaia and N. G. Mikhailova, ‘Novye materialy po istorii drevnerusskikh gorodov’, Istoriia SSSR, 1970, no. 4, pp. 199–202; G. V. Alferova, Russkie goroda XVI–XVII vekov (Moscow: Stroiizdat, 1989); Bagrow, History of the Cartography of Russia up to 1800, pp. 1–17; N. F. Gulianitskii, ed., Gradostroitel′sto Moskovskogo gosudarstva XVI–XVII vekov (Moscow: Stroiizdat, 1994), passim; A. V. Postnikov, Razvitie krupnomasshtabnoi kartografii v Rossii (Moscow: Nauka, 1989), pp. 5–10; B. A. Rybakov, Russkie karty Moskovii XV-nachala XVI veka (Moscow: Nauka, 1974), pp. 7–20; Leonid A. Gol′denberg, Russian Maps and Atlases as Historical Sources, trans. by James R. Gibson (Toronto: B. V. Gutsell, Dept. of Geography, York University, 1971).

12 RGADA, coll. 1209, Aleksin stlb. 31 494, fol. 115.

13 Bagrow, History of Russian Cartography up to 1800, p. 34; V. S. Kusov, Kartograficheskoe iskusstvo Russkogo gosudarstva, p. 27; S. I. Sotnikova, ‘Pamiatniki otechestvennoi kartografii XVII v.’, Pamiatniki nauki i tekhniki, 1987–1988, 1989, no. 6, pp. 176–201 (pp. 181, 186, 196, 198). Also, Franklin, ‘Printing Moscow’, p. 87. On chertezhi, see also Lutz Häfner, ‘Europa ohne Grenzen? Zu Wandel und Funktion der russlandbezogenen Kartographie vom Moskauer Reich bis zur Mitte des 18. Jahrhunderts’, in Osteuropa kartiert—Mapping Eastern Europe, ed. Jörn Happel (Münster: LIT, 2010), pp. 87–112.

14 Carol Symes, ‘The “Desire of Deeds”: Sensuality, Nostalgia, and the Affective Effects of Medieval Documentation’, talk presented at the Eisenberg Institute for Historical Studies, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, 1 October 2015. The talk comes from her current project, The Mediated Text: Documentary Initiatives and Their Agents in Medieval Europe.

15 It is worth noting that magical spells, an illicit but popular genre, invoked the cardinal directions as part of their ritual, evidence that the points of the compass were part of common knowledge, even if the compass was not.

16 Gottfried Hagen identifies similar practices in seventeenth-century Ottoman cartography, which assumes “an observer in motion along the surface of the earth, and renders his dynamic and contextual perspective”. Like Muscovite chertezhi, Ottoman maps are easily “derided as an ‘abyss of cartographic barbarity’”, but, Hagen shows, they should be read in their own terms. ‘Kātip Çelabi’s Maps and the Visualization of Space in Ottoman Culture’, Journal of Ottoman Studies, 40 (2012), 283–93 (289; 285); quoting Hans von Mžik, ‘Ptolemaeus und die Karten der arabischen Geographen’, Mitteilungen der geographischen Gesellschaft Wien, 58 (1915), 152–76 (p. 168).

17 RGADA, coll. 192, descr. 1, Kaluzhskaia guberniia, no. 1. Leonid S. Chekin corrects my discussion of the orientation of this map, which he dates to 1675, in ‘Russian Maps and Spatial Thinking in the Seventeenth Century’, The Portolan, 68 (Spring 2007), 51–58 (p. 56). This is an interesting though uncharitable review of my book, Cartographies of Tsardom.

18 Chekin ‘Russian Maps and Spatial Thinking in the Seventeenth Century’, p. 56.

19 RGADA, coll. 1209, Suzdal′ stlb. 27955, ch. 1, l. 73b.

20 RGADA, coll. 1209, Murom, stlb. 36032, fol. 182; 183; 184; RGADA, coll. 1209, Uglich, stlb. 35730, Ch. 1, fol. 57.

21 RGADA, coll. 1209, Suzdal′ stlb. 28043, ch. 1, fol. 142.

22 RGADA, coll. 1209, Iur′ev Pol′skoi, stlb. 34253, Ch. 1, fol. 132.

23 RGADA, coll. 1209, Iur′ev Pol′skoi, stlb. 34253, Ch. 1, l. 132.

24 RGADA, coll. 192, descr. 1, Kaluzhskaia guberniia, no. 1.

25 Chekin, ‘Russian Maps and Spatial Thinking in the Seventeenth Century’, 56–57. The map in question is RGADA, coll. 192, Kaluzhskaia guberniia, no. 1. A. P. Gudzinskaia and N. G. Mikhailova make an equally compelling argument for the precision and accuracy of architectural representations on chertezhi. See their ‘Graficheskie materialy, kak istochnik po istorii arkhitektury pomeshchich′ei i krest′ianskoi usadeb v Rossii XVII v.’, Istoriia SSSR, 5 (1971), pp. 214–27.

26 I will not address here B. A. Rybakov’s not entirely convincing argument for the creation of a map of Muscovy in the fifteenth century. See his Russkie karty Moskovii XV-nachala XVI veka and his ‘Russian Maps of the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries’, trans. by James A. Gibson, The Canadian Cartographer, 14 (1977), 10–23.

27 Kniga Bol′shomu chertezhu, ed. K. N. Serbina (Moscow: AN SSSR, 1950), p. 49 (fol. lv of reproduced text). Some scholars date the original map to the reign of Ivan IV.

28 Simon Franklin provides a model of how to read manuscripts for material traces of reading practices. See his “Dirty Old Books”, in Picturing Russia: Explorations in Visual Culture, ed. by Valerie A. Kivelson and Joan Neuberger (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), pp. 12–16.

29 On the Bol′shoi chertezh, and for reproductions of some late copies of the Ukrainian maps, see Bagrow, History of the Cartography of Russia up to 1800, pp. 4–12; Serbina, Kniga Bol′shomu chertezhu; Postnikov, Razvitie krupnomasshtabnoi kartografii v Rossii, pp. 20–22; Kusov, Kartograficheskoe iskusstvo Russkogo gosudarstva, pp. 75–77.

30 The rediscovery of the work of the ancient geographer, astronomer, and mathematician, Claudius Ptolemy (100–160 CE), revolutionised European understandings of cartography. His Geography set out principles of measurement of latitude and longitude and methods for calculating the diameter of the globe.

31 Katharina N. Piechocki, ‘Erroneous Mappings: Ptolemy and the Visualization of Europe’s East’, in Early Modern Cultures of Translation, ed. by Karen Newman and Jane Tylus (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), p. 86. Piechocki notes that Miechowita never travelled to the lands he described but drew on interviews with people who had been there. On Waldseemüller and the Ptolemaic model, see also John W. Hessler, The Naming of America (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 2008), pp. 18–25.

32 Sigmund Freiherr von Herberstein, Notes Upon Russia, 2 vols, Elibron Classics Reprint of the 1852 publication by the London’s Hakluyt Society (Adamant Media, 2005), vol. 2, p. 105, https://archive.org/details/notesuponrussiab02herbuoft

33 Leo Bagrow, History of Cartography up to 1600, ed. by Henry W. Castner (Wolfe Island, ON: The Walker Press, 1975), p. 60, pp. 70–72.

34 Among the earliest in this boom was a map made by Battista Agnese on the basis of information provided by the Russian ambassador to Rome, Dmitrii Gerasimov, in 1525. Gerasimov was a source for Herberstein as well. Another early map was made by Ivan Liatskoi in 1542. See for instance, discussions in Bagrow, History of Cartography up to 1600, pp. 61–135; Krystyna Szykuła, ‘Anthony Jenkinson’s Unique Wall Map of Russia (1562) and its Influence on European Cartography’, Belgeo (2008), pp. 3–4, http://belgeo.revues.org/8827; Samuel H. Baron, ‘The Lost Jenkinson Map of Russia (1562) Recovered, Redated and Retitled’, Terrae Incognitae: The Journal of the Society for the History of Discoveries, 25. 1 (1993), 53–66.

35 Alexey Postnikov and Marvin Falk, Exploring and Mapping Alaska: The Russian America Era, 1741–1867, trans. by Lydia Black (Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 2015), pp. 17–18. See also Leonid A. Gol′denberg and A. V. Postnikov, ‘The Development of Mapping Methods in Russia’, Imago Mundi, 37 (1985), 63–80.

36 Leo Bagrow, ‘Semyon Remezov: A Siberian Cartographer’, Imago Mundi, 11 (1954), 111–25 (p. 112); cites N. N. Ogloblin, comp., Obozrenie stolbtsov i knig Sibirskogo prikaza, 1592-1768, book 2, in Chteniia v Obshchestve istorii i drevnostei rossiiskikh pri Moskovskom universitete (Moscow, 1895), vol. 173, p. 249; and S. V. Bakhrushin, Ocherki po istorii kolonizatsii Sibiri v 16-om i 17-om vv. (Moscow: Izd. M. and S. Sabashnikovykh, 1927), 17–19 ff. Bagrow notes that Godunov supervised another ambitious mapping project in 1668, ‘Information on the Land of China and on the Depths of India Provided by Petr Ivanovich Godunov’.

37 Khorograficheskaia kniga Sibiri [Chorographic Sketch-book of Siberia], MS Russ 72 (6). Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, ff. 5v-6, https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:18273155$10i. On Petr Godunov’s cartographic work and on this map, see Gregory Afinogenov, ‘The Eye of the Tsar: Intelligence-Gathering and Geopolitics in Eighteenth-Century Eurasia’ (Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, 2016), pp. 40–45.

38 Henry Huttenbach, ‘Hydrography and the Origins of Russian Cartography’, Five Hundred Years of Nautical Science, 1400–1900, Proceedings of the Third International Reunion for the History of Nautical Science and Hydrography held at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, 24–28 September 1979, ed. by Derek House (Greenwich: National Maritime Museum, 1981), pp. 142–52 (p. 148).

39 On Remezov, see L. A. Gol′denberg, Izograf zemli sibirskoi (Magadan: Magadanskoe knizhnoe Izd., 1991); and his Semen Ul′ianovich Remezov, sibirskii kartograf i geograf, 1642-posle 1720 gg. (Moscow: Nauka, 1965); Kivelson, Cartographies of Tsardom; A. V. Postnikov, ‘Kartografirovanie Sibiri v XVII–nachale XVIII veka. Semen Ul′ianovich Remezov i ego rukopisnye atlasy’, in Chertezhnaia kniga Sibiri, sostavlennaia tobol′skim synom boiarskim Semenom Remezovym v 1701 godu, ed. by A. A. Drazhniuk, et al., 2 vols, vol. 2: Issledovaniia (Moscow: PKO ‘Kartografiia’, 2003), pp. 7–19.

40 Rossiiskaia gosudarstvennaia biblioteka, Moscow, Rukopisnyi otdel, coll. 256, Rumiantsev Collection, no. 346; published in a facsimile edition as Chertezhnaia kniga Sibiri, sostavlennaia tobol′skim synom boiarskim S. Remezovym v 1701 godu, 2 vols (Moscow: FGUP, PKO Kartografiia, 2003), p. 10.

41 Chertezhnaia kniga Sibiri, 4; discussed in V. N. Fedchina, ‘Central Asia on Russian Maps of the Seventeenth Century’, The Canadian Cartographer, 10. 2 (1973), 95–105 (102).

42 Rossiiskaia natsional′naia biblioteka, St Petersburg, Ermitazhnoe sobranie, no. 237, Sluzhebnaia chertezhnaia kniga Remezova, fol. 1; Remezov, Semen Ul′ianovich, 1642-ca. 1720. Khorograficheskaia kniga, f. 1v.

43 On the gathering of maps from many mapmakers, see, for instance, Chertezhnaia kniga, fol. 3, which explains that the tsar ordered the mapping of Siberia in 7177 (1668–69), and maps were collected between that year and 7209 (1700–01). Some maps in the atlas acknowledge their original authors, as, for example, Khorograficheskaia kniga, f. 147, which credits Lieutenant of the Daur Regiment Afonasii Ivanov syn Baikov with a sketch of the Amur River, China, Nerchinsk, and Irkutsk.

44 Sluzhebnaia chertezhnaia kniga Remezova, fol. 102v.

45 Marina Tolmacheva, ‘The Early Russian Exploration and Mapping of the Chinese Frontier’, Cahiers du Monde russe, 41. 1 (2000), 41–56 (pp. 44–46).

46 Afinogenov, ‘Eye of the Tsar’, pp. 47–51 (on Spafarii); p. 8 (quotation). Afinogenov reconstructs the Eastern contributions to the communications networks through which information on Siberia and China circulated and explores the world of intelligence gathering in which Russia played a part.

48 Postnikov and Falk, Exploring and Mapping Alaska, p. 19.

49 Ibid. Witsen’s source was Stanislav Loputskii, described by Postnikov and Falk as “an artist at the court of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich”. Witsen created his own quite extraordinary map of Siberia. See Johannes Keuning, ‘Nicolaas Witsen as a Cartographer’, Imago Mundi, 11 (1954), 95–110.

50 Newberry Library, Chicago, ‘Carte générale de la Siberie et de la Grande Tatarie’, in Cartes Marines, Edward Everett Ayer Collection; discussed in A. V. Postnikov, ‘Russian Cartographic Treasures of the Newberry Library’, Mapline, 61–62 (1991), 6–8.

51 Postnikov and Falk, Exploring and Mapping Alaska, 19. See also Leo Bagrow, ‘Sparwenfeld’s Map of Siberia’, Imago Mundi, 4 (1947), foldout plate following p. 68; J. G. Sparwenfeld’s Diary of a Journey to Russia 1684–1687, ed. by U. Birgegard (Stockholm: Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien, 2002); and Erich Palmquist, Zametki o Rossii, sdelannye Ėrikom Pal′mkvistom v 1674 godu, ed. by Anatolii Sekerin and Gennadii Kovalenko, English trans. by Martin Naylor (Moscow: Lomonosov, 2012).

52 The German version is reproduced in Bagrow, ‘Remezov’, pp. 124–25.

53 S. M. Gluskina, ‘“Kosmografiia” 1637 goda kak russkaia pererabotka “Atlasa” Merkatora’, in Geograficheskii sbornik, 3 (Moscow-Leningrad, 1954), pp. 79–99; N. A. Kazakova, ‘Russkii perevod XVII v. truda Blau “Theatrum Orbis Terrarum sive Atlas Novus”’, Vospomogatel′nye istoricheskie distsipliny, 17 (1986), pp. 161–78; idem., ‘Russkii perevod XVII v. “Theatrum Orbis Terrarum” A. Orteliia’, Vospomogatel′nye istoricheskie distsipliny, 18 (1987), 121–31; B. E. Raikov, Ocherki po istorii geliotsentricheskogo mirovozzreniia v Rossii (Moscow-Leningrad, 1947), pp. 79–90.

54 Kazakova, ‘Russkii perevod XVII v. truda Blau’, p. 169. On the translations, see also Francis J. Thomson, ‘Slavonic Translations Available in Muscovy: The Cause of Old Russia’s Intellectual Silence and a Contributing Factor to Muscovite Cultural Autarky’, in Christianity and the Eastern Slavs, vol. I: Slavic Cultures in the Middle Ages, ed. by B. Gasparov, Olga Raevsky-Hughes, California Slavic Studies 16 (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1993), pp. 193–94; p. 212, n. 211. For an account of the sources of early European cosmographic treatments of Russia, see Marshall T. Poe, ‘Muscovy in European Cosmographies, 1517–1544’, Russian History/Histoire Russe, 25. 1–2 (1998), 89–106.

55 Irena Gross, ‘The Tangled Tradition: Custine, Herberstein, Karamzin and the Critique of Russia’, Slavic Review, 50 (1991), 989–98.

56 Postnikov, Russia in Maps, p. 24.

57 Remezov, Sluzhebnaia chertezhnaia kniga, fol. 12 (‘Do laskovago chitatelia’); Remezov, Khorograficheskaia kniga, ff. 8v-9.

58 Remezov, Sluzhebnaia chertezhnaia kniga, fols. 22v-23 (includes Zlata Baba); fol. 107, ‘Chertezh zemli khanskago velichestva’, with cartouches, vignettes, and Latin labels. See also Remezov, Khorograficheskaia kniga, f.v., two-hemisphere map.

59 Tolmacheva, ‘Early Russian Exploration and Mapping of the Chinese Frontier’, p. 50.

60 Daniel C. Waugh, ‘The View from the North: Muscovite Cartography of Inner Asia’, Journal of Asian History, 49 (2015), 69–96, quote on p. 82.

61 Remezov, Khorograficheskaia kniga, f. 48.

62 Kees Boterbloem, Modernizer of Russia: Andrei Vinius, 1641–1716 (Houndsmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), p. 166. Some scholars note a similarity with Chinese mapping. See Fedchina, ‘Central Asia on Russian Maps of the Seventeenth Century’, 104; Waugh, ‘View from the North’, p. 82; Tolmacheva, ‘Early Russian Exploration and Mapping of the Chinese Frontier’, pp. 41–56. For a pair of maps by Kalmyk cartographers of the eighteenth century, displaying yet another cartographic imaginary, see Nicholas Poppe, ‘Renat’s Kalmuck Maps’, Imago Mundi, 12 (1955), 155–59. The maps are viewable online at http://goran.baarnhielm.net/Renat/index.html

63 Boterbloem, Modernizer of Russia, p. 166.

64 Postnikov and Falk, Exploring and Mapping Alaska, p. 9; Bagrow, ‘Remezov’, p. 125.

65 Bagrow, ‘Remezov’, pp. 124–25.

66 Afinogenov, ‘Eye of the Tsar’, p. 32.

67 Ibid., p. 34.