12. Experiencing Information: An Early Nineteenth-Century Stroll Along Nevskii Prospekt

© 2017 Katherine Bowers, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0122.12

Nevskii Prospekt has long been St Petersburg’s famous boulevard; it was where Imperial Russian high society went to see and be seen, as well as home to all the best shops: confectionaries, vintners, haberdashers, bootmakers, swordmakers, modistes, milliners. Thanks to the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century mania for urban depiction, in artists’ renderings and writers’ sketches we have “snapshots”—in a sense—of the street’s life, giving insight into its appearance before the development of photography. In the 1820s work of artist Vasilii Sadovnikov, for example, Nevskii Prospekt is celebrated; its stately buildings, grand monuments, and bridges depicted elegantly under an idyllic pale blue sky. His remarkable watercolours painstakingly reproduce every building along each side of the famous street, from the Admiralty to the Anichkov Bridge.2 In 1830 and 1835, respectively, publisher and art patron Andrei Prévost commissioned two masters who shared a common surname, Ivan and Petr, both Ivanov, to lithograph Sadovnikov’s watercolours. The monochromatic lithographs were then coloured by hand with watercolour paint and published in a collection called Panorama of Nevskii Prospekt (Panorama Nevskogo Prospekta).3

Panorama is made up of two continuous lithographed scrolls mounted on bands of linen: “The Left, Sunny Side of Nevskii Prospekt” (P. Ivanov, 1835), and “The Right, Shady Side of Nevskii Prospekt” (I. Ivanov, 1830). Beginning at Palace Square, the scroll records buildings along the “sunny” side of the street, crosses the thoroughfare at the Anichkov Bridge, and records buildings along the “shady” side back to the Square. By rolling the scroll, nineteenth-century viewers could “walk along” the street, pausing as often as they liked to study each individual building and monument. The quality of the images is high, given Sadovnikov’s noted precision and Panorama’s immense dimensions of approximately 7.1 metres by 26.4 centimetres per street side.4

Writing in the 1830s, one reviewer called it a “masterly lithographic scroll” and another commented, “This is, so far, the best likeness of our beautiful Nevsky Prospekt”.5 St Petersburg’s noted architects Carlo Rossi and Auguste de Montferrand praised Panorama, and many residents bought copies of the scroll, despite its ungainly length, to use as decorations or gifts.6 The work caused a stir both because of its precision and the unique visual look at the city it provided. Early nineteenth-century feuilletons and physiological sketches enabled readers to “experience” urban space, taking them on verbal “strolls”.7 The scroll’s depiction of the famous street was based on a similar concept; it allowed viewers in St Petersburg and elsewhere in the Russian Empire to “visit” and “take in” its notable perspectives, fashionable façades, and famous monuments, as well as its service class, consumer culture, and popular storefronts, from their homes in a uniquely visual way which omits many of the aspects of urban experience including smells, sounds, and bustle.

The word Panorama in the title, deliberately chosen by Prévost, is a commercial gimmick, meant to evoke the popular entertainment of the panorama, a handheld device that enabled viewers to traverse a rendered landscape.8 Contemporary scholars have connected the material experience of viewing the Panorama with a kind of virtual reality, an imagined journey along the fashionable thoroughfare. Art historian Tatiana Senkevitch suggests that Sadovnikov’s Panorama could also “be pushed simultaneously through two special boxes with glass windows—the viewer was situated between them… [giving] an impression of simulating an imaginary carriage ride through the city”.9 Julie Buckler observes that the inclusion of objects like shop signs and the “chance encounters and particulars of dress and posture” of recognisable members of St Petersburg society “rendered the Prospect very much of its moment”.10 Buckler views the material form of the scroll as instrumental in creating “a more ‘local’ sense of street life”.11 In this sense, Panorama provides an intriguing case study of the nineteenth-century public graphosphere as it was visualised contemporaneously. In this chapter—and in the spirit of Panorama’s original use—I will embark upon a visual “stroll” down Nevskii Prospekt, but I will focus not on imperial monuments or elegant palaces, but on commercial enterprise and, in particular, on shop signs.

In the previous chapter, Simon Franklin introduced the graphosphere and gave a broad overview of its formation and many functions. In this chapter, I will use Sadovnikov’s Panorama as a case study that enables close observation of the minutiae of shop signs, their placement, arrangement, contents, and aesthetic. Shop signs had been regulated by a series of imperial decrees throughout the eighteenth century, as Franklin describes. Initially, official regulations were restrictive, but eventually urban zoning laws were relaxed, which allowed for mixed commercial and residential spaces and, as a result, flourishing small enterprise. As trade grew, so too did the proliferation of shop signs. Eventually, by the 1820s, as can be seen in Panorama, signs were a regular feature of urban space. Franklin draws the distinction between signs generated by state institutions and those generated by commercial activity; as he notes, this proliferation was “not ‘top down’ but ‘bottom up’”.12

Scholars typically date the decline of St Petersburg’s “purity” in architecture to the moment when Nicholas I broke with convention and allowed the rapid construction of plain buildings to house the growing imperial bureaucracy.13 However, even before the proliferation of “bureaucratic classicism” in the 1830s and its destabilisation of the ideological power inherent in imperial structures, growing commercial enterprise encroached on the neoclassical purity of the seat of power. Buckler observes that Sadovnikov’s work, in its representation of “high and low, distanced and near”, is able to provide “a sense of urban space as a whole”.14 The tension between trade and authority comes to the fore in Sadovnikov’s watercolours precisely because Nevskii Prospekt is so grand—it is a space that reflects imperial vision with its monuments and palaces—but, at the same time, is host to intense commercial enterprise, which necessarily aims mainly to communicate with potential customers.

The urban public graphosphere present along Nevskii Prospekt, as seen in Sadovnikov’s watercolours, sheds light on the complicated, often conflicting relationship between commercial enterprise and imperial authority in the first half of the nineteenth century. While the graphosphere portrayed is limited to a single notable street and, therefore, by no means gives a comprehensive overview of urban space, it nonetheless proves productive. This captured graphosphere demonstrates how commercial enterprise and imperial authority are juxtaposed through their representation in information technologies.

Sadovnikov’s Perspective

V. S. Sadovnikov was a serf born on the estate of Princess Natalia Golitsyna in 1800; both he and his older brother Petr were educated from childhood through the Golitsyn family’s patronage. Vasilii became a landscape painter known for his attention to detail while Petr became a celebrated architect. While studying as a child in the studio of architect Andrei Voronikhin, Sadovnikov met landscape painters Maksim Vorob′ev and Aleksei Venetsianov, who exerted influence on his development as an artist. In the 1820s he had a series of popular successes with his watercolours, Views of St Petersburg and Surrounding Areas (Vidy Peterburga i okrestnostei) (1823–27) and the series of late 1820s watercolours that became Panorama (1830–35); these works emerged with the help of the Imperial Society for the Encouragement of Artists (Obshchestvo pooshchreniia khudozhnikov), which supported the work of talented serfs. Notably, the society’s salon is visible on our “stroll”, and we will see it when we come to figure 12 of the present chapter; the salon sign prominently features the year of its founding, 1826, and its name in both French and Russian. In the 1830s, the Panorama scroll could be purchased in this building!

In 1838 Sadovnikov received the title “svobodnyi neklassnyi khudozhnik” (free unclassed artist) from the Academy of Arts and also his freedom from bondage.15 At the time, he was already a well-known artist thanks to his two watercolour series, Views and Panorama. In the announcement of the publication of Panorama in 1830, he is referred to as “g Sadovnikov” (Mr Sadovnikov), a title atypical for a serf. At his death in 1879, Sadovnikov was widely considered a master of both landscape and genre painting.16

Sadovnikov’s training as an artist comes through in the spatial composition of Panorama. The central element of the scroll is the line of buildings; these draw the viewer’s attention first. Above them is the limpid blue sky, below, the street, populated by small figures. In comparison to the figures, however, the architecture dominates. In this sense, the scroll demonstrates the result of the imperial project that began in the first half of the eighteenth century, the transformation of Nevskii Prospekt into “an unbroken chain of related ensembles”.17 Yet, these watercolours do not just depict imperial pomp; they also show glimpses into the life of the street.

Sadovnikov’s experience of aristocratic society as an outsider may inform Panorama in that its population includes passers-by from all classes. From high-ranking noblemen wearing dress uniforms and fashionable society ladies to members of the lower classes such as tradesmen, peddlers, servants, and labourers, all can be seen along Sadovnikov’s Nevskii. Even some specific, recognisable individuals (including Pushkin) stroll along Sadovnikov’s boulevard. Similarly, Sadovnikov focusses on the commercial aspects of the street, particularly its residents’ gastronomic and sartorial pursuits. Fashionable artists of the time such as T. A. Vasiliev, A. Martynov, K. P. Beggrov, and many others depicted St Petersburg’s neoclassical façades, grand squares, and elegant bridges as grand architectural studies; in comparison, Sadovnikov’s St Petersburg has a striking energy. His scenes invite the viewer to experience urban space, to “feel the spirit of the age”.18

Shop Signs Along the Sunny Side

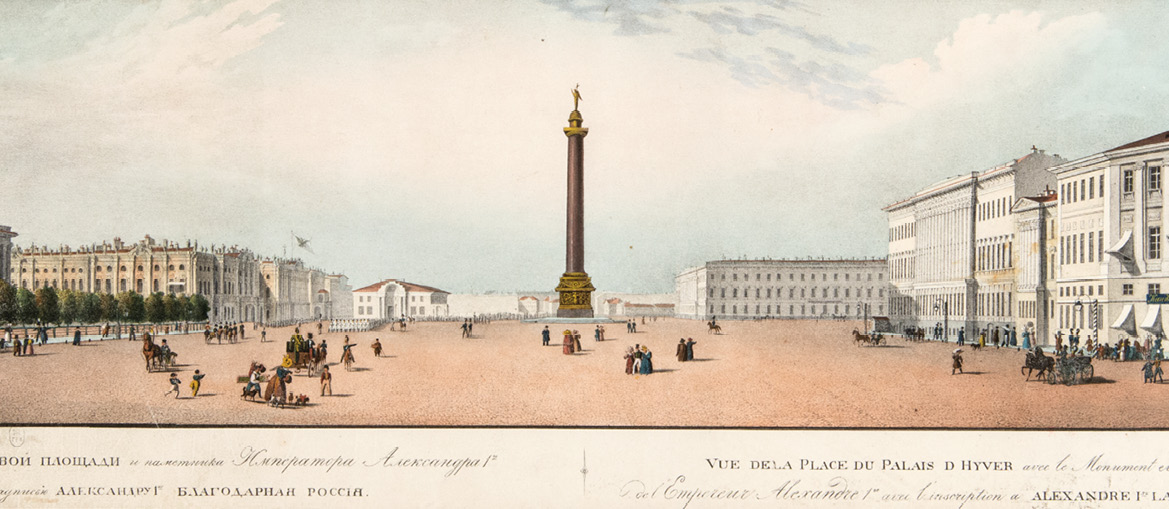

Our stroll begins with a view of Palace Square; Rastrelli’s grand Winter Palace is visible behind the immense Alexander Column. The Column, a monument to the victory over Napoleon in 1812, was designed by architect Auguste Montferrand and does not appear in Sadovnikov’s original watercolours; it was raised between 1830 and 1834. Throughout the scroll, there are some chronological discrepancies as the lithographers updated the original rendering of the street to reflect new noteworthy sights and businesses. Notable, too, is the sense of movement given by populating the street scene with individual figures going about their business. Here, a company of soldiers marches across the square while passers-by look on, ladies stroll, boys chase each other at play, and a group of dogs frolicks. This vibrancy sets the Panorama apart from the static engraved images of urban space that had become popular in the eighteenth century.

This initial introduction to Nevskii Prospekt is saturated with the emblems of empire: grand displays of wealth, power, and glory, as well as attention to the square’s ensemble of palace and monument. St Petersburg itself represents a grand imperial building project, an exercise in authority in the sense of the moderation and control of public space. Here, in the home of the tsar and the headquarters of the military forces, the empire’s might is apparent not only in the company of soldiers marching past, but also in the neoclassical façades and spatial composition of the square. As historian William Craft Brumfield has succinctly articulated, “The architecture of St Petersburg—grandiose, overpowering at times, obsessed with rational design—remains the clearest statement of purpose that Imperial Russia ever made: to measure, to build, to impose order at any cost”.19

Figure 1: View of Palace Square.

As we move down Nevskii Prospekt away from Palace Square along the left, sunny side of the street in the perpetual afternoon of Sadovnikov’s watercolours, commercial displays such as shop signs and storefronts begin to appear. Senkevitch argues that moving along Nevskii activates “the kinesthetic command of the observer by imposing on him/her a certain hegemony of visual order enforced by the rhetoric of architectural spaces”.20 However, the commercial spaces that confront us sharply contrast with the stately ensemble of the Square, and interrupt the “hegemony of visual order” that the imperial architecture imposes. While still neoclassical and grand, the façades here host a proliferation of shop signs mixing languages, scripts, and images. Signs spell out names in both Cyrillic and Latin scripts—for example: “Formann/Форманъ” or “Elers/Елерсъ”. Images, too, begin to appear in addition to the words.

In his 1858 travel account, Théophile Gautier remarks on the wonders of the multilingual and image-rich signage on Nevskii Prospekt:

But perhaps you don’t know Russian, and the form of the characters means nothing more for you than an ornamental design or a piece of embroidery? Here to the side is the French or German translation. You still haven’t understood? The obliging sign pardons you for not recognising any of these three languages; it even assumes that you might be completely illiterate, and presents a lifelike depiction of the goods for sale in the shop it is advertising. Sculpted or painted bunches of golden grapes indicate a wine merchant; further along glazed hams, sausages, tongues, tins of caviar designate a food shop; high boots, ankle boots, naïvely presented galoshes, say to feet that don’t know how to read: ‘Enter here and you will be shod’; crossed gloves speak an idiom intelligible to all.21

The mix of Russian, French, German, Italian and even English and Dutch is not surprising, given Nevskii’s typically elite and cosmopolitan clientele.22 Nearly all the signs are at least bilingual.

The images that appear in addition to the words lend decoration, but also have a utilitarian purpose. The literate minority of St Petersburg could frequently read all three languages, and lower-level monolingual literacy existed at this time as well, but, as Gautier observes, shopkeepers took no chances of missing out on potential customers, and therefore often included visual depictions.23 These could be aimed at illiterate servants, for example, sent to pick up or purchase goods.

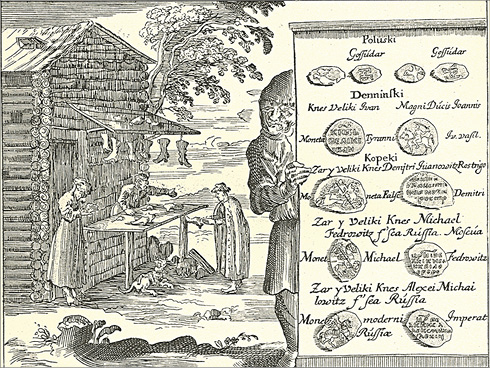

Along Nevskii, shop signs are typically mounted flush to the buildings, and include images as well as text as in, for example, a storefront with images of scissors denoting a tailor or a craftsman’s shop sign showing an array of canes and umbrellas or mathematical instruments. This style of signage was the result of mingling and exchange between eighteenth-century Western European merchants and Russian merchants in the capital. In antiquity, shop signs had been emblematic (as we know from those found in Pompeii, for example).24 In medieval Western Europe, signs in the form of frescoes and murals gave way to painted shop signs as secular art developed.25 In Jean Fouquet’s 1458 illuminations, for example, painted shop signs can already be seen (fig. 3). However, scholars have not found literary or pictorial evidence of signboards in fifteenth-century Russia, even as late as the seventeenth century. One of the earliest known examples of Russian advertising appears in a late seventeenth-century wood cut print depicting Moscow that shows goods were hung outside the shop so customers would see them (fig. 4).26 Commercial signs in Russia continued to develop visually rather than textually until the influx of German, Dutch, French and English merchants in the eighteenth century, and the Western European commercial traditions they brought with them.

Figure 3: Jean Fouquet, Boccace écrivant le De Casibus (1458).

Figure 4: A bootmaker’s stall, from Adam Olearius’s Vermehrte Newe Beschreibung Der Muscowitischen vnd Persischen Reyse (1656).

The signs on Nevskii Prospekt appeal to a clientele with a taste for the fashionable and elegant, and are a far cry from what you would see on a typical Russian urban street at this time. The Nevskii signs project information about the quality or exclusivity of the businesses they advertise. Reassuring to consumers, signs featuring a single glove or boot in profile are common, and modelled after guilds’ Western European-style heraldic banner signs.27 Introduced into Russia during the reign of Peter the Great, but based on the medieval Western European model, merchant and craft guilds stood for quality and consistency of goods.28 During Catherine II’s reign, guilds began using their signs as advertising. Consumers would have recognised the form of guild signs in these shop signs, meant to assure them of good service. One of the most famous of these banner signs is that of the guild of German bakers, symbolised by a golden pretzel held aloft by two lions (fig. 5). We see its echo in the shop signs along Nevskii, a golden-coloured pretzel appears several times over the course of our stroll, but without its lions; the guild’s heraldic image has come to represent a bakery, generally (fig. 6). These images visibly demonstrate that the importation of Western culture was not confined to the neoclassical architecture that lined St Petersburg’s streets, but also played a significant role in the development of commerce.

Figure 5: Symbol of the Bakers’ Guild, East Frisian Island of Juist (Lower Saxony, Germany).

Figure 6: A pretzel on a bakers’ sign from the Panorama.

Figure 7: Cakes, mathematical instruments, and wigs.

Figure 8: Coats, frocks, and musical instruments.

Storefronts with signs featuring only images tend to represent goods that speak for themselves. A dry goods merchant has no sign, only enormous gleaming sugar loaves in his windows. Similarly, a vintner has hung a bunch of grapes above his door and includes no other decoration. These examples are much more reminiscent of earlier signs, which tend towards universal emblems. Similarly, some specialty shops include signs that describe the variety of goods for sale in one store. A musical instrument dealer features a wide array of musical instruments on his shop sign (fig. 8), while a scientific instruments dealer includes images of his specialised stock: abacuses, rulers, compasses and protractors, and other instruments (fig. 7). These enormous signboards seem merely decorative at first glance, but have a utilitarian function. Art historians Alla Povelikhina and Yevgeny Kovtun suppose that, “For a Russian, a detailed and evocative depiction of the complete choice of merchandise, instruments, or goods for sale in a shop was especially understandable, for he preferred seeing the actual product to hearing about it or, even more, to reading about it, since he may have been illiterate or unwilling to take the trouble”.29 Whether or not their claim that these pictorial lists are a particularly Russian tendency is accurate, there can be no doubt about their efficacy as information technology. These image-only signs convey information to a broad audience, seeking to advertise and sell to as many passers-by as possible.

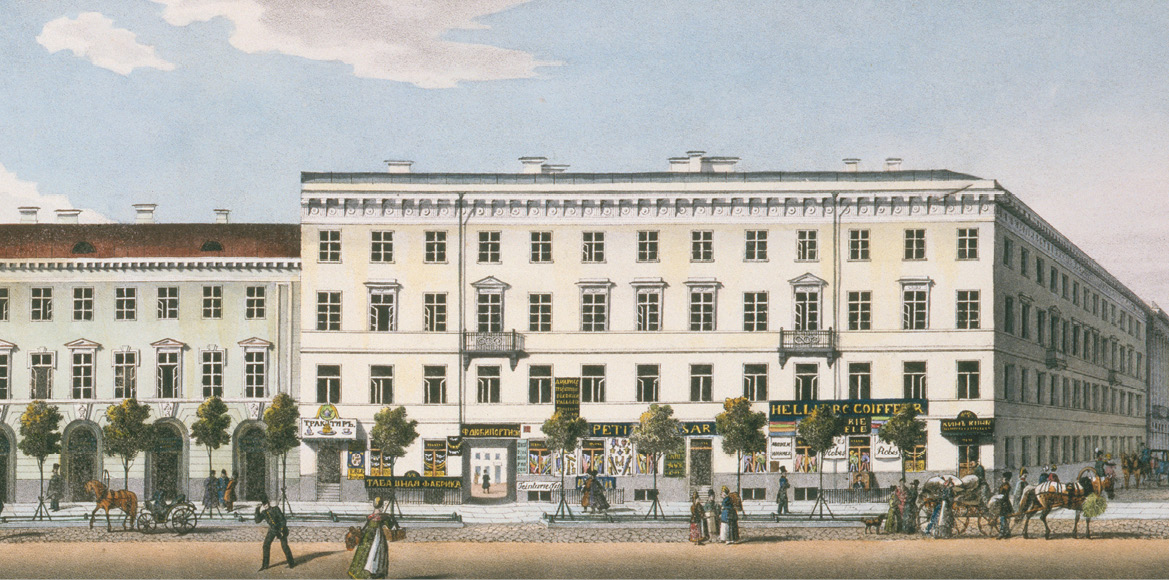

A dedicated advertising campaign can be seen in the decoration of Rode’s large store (fig. 9), located at the corner of Nevskii Prospekt and Malaia Millionnaia (a name used to refer to the top of Bolshaia Morskaia until the middle of the nineteenth century). Whereas other buildings we have passed feature a proliferation of signs placed with little system to proclaim and advertise the many businesses housed within and tucked away in their courtyards, this storefront features a uniform façade with large windows with lamps between each, multiple entrances, and signs neatly spaced, symmetrically arranged, and placed with some view to neoclassical aesthetics. Rode’s signs are a variety of shapes: diamonds, rectangles, and some half-circle, half-square. Some are in French, some in Russian, and some feature images of the goods within: gentlemen’s frock coats, hats, and dress swords. A large, ornate sign above the main entrance on the corner of Nevskii and Malaia Millionnaia proudly displays RODE/РОДЕ in enormous capital letters. The careful placement of signs here echoes the “grand spatial composition” of the building’s location on the corner of two major avenues, while no one can be in doubt of either what goods are for sale or their quality.

Advertising using images was common, but signs featuring only text tended to be for more exclusive locales along Nevskii, those where representative images would either be superfluous or considered vulgar. Continuing our “stroll”, just before Police Bridge,30 the first cast iron bridge in the city, an elegant confectioner’s shop has wide windows and broad steps, and presents a good prospect of the canal (fig. 10). Its signs wrap around, proclaiming, on the Nevskii Prospekt side, “С. Волфъ и Т. Беранже”, then over the door at the corner “Café Chinois”, and on the far side “S. Wolf et T. Béranger”. This particular confectionary was famous at the time as a favourite café of Petersburg literary society; Pushkin would eat his last meal at Wolf and Béranger before setting off to his fatal duel in January 1837, and the premises would become part of the legend surrounding the famous poet. Notably, for passers-by unable to read, this building offers no picture to show what it contained. Its façade features elegant iron railings and stonework; its signs display the name prominently in multiple languages, but only the “Café Chinois” sign on the building’s corner offers a clue, and, to get it, one must understand French, that tea comes from China, and that one has cakes with tea. In their signage, Wolf and Béranger make a statement about their elite premises, further demonstrated by their use of only “tasteful” advertising—no gauche signs picturing food here! For the same reason, the elite hotels we have passed—the Hotel London and Hotel Demuth—feature little to no signage, and that with text only, when present.

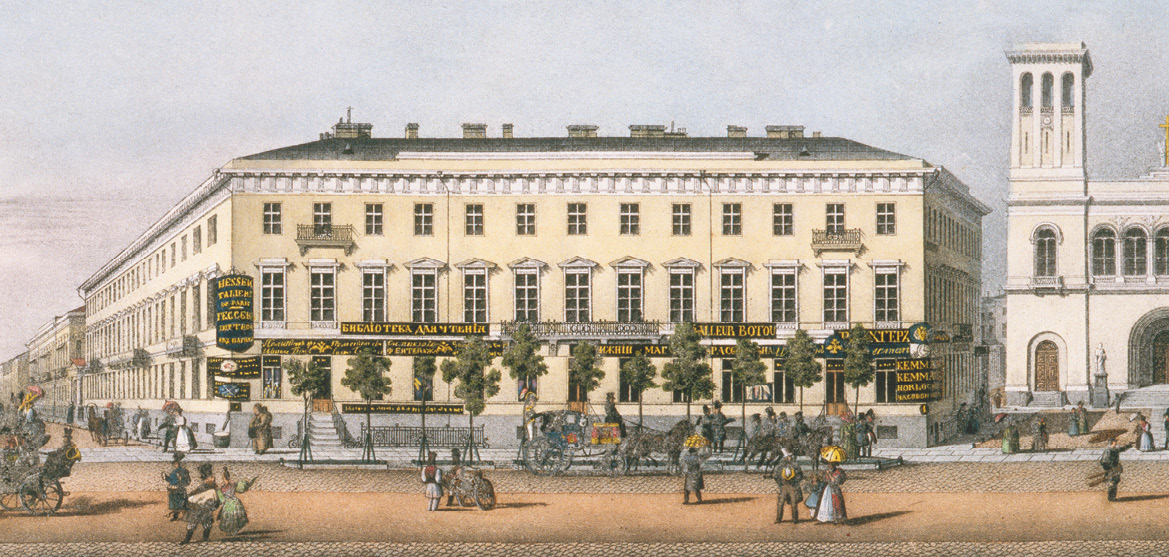

Bookshops, presumably presupposing literacy in their clients, tend to feature text-only signs. Across the Moika, on the corner of Nevskii and Bolshaia Koniushennaia, there is another large commercial operation: that of early nineteenth-century publishing mogul Aleksandr Smirdin (fig. 11). The lithographs depict Smirdin’s thriving business, with large signs declaring the offices of the innovative Library for Reading (Biblioteka dlia chteniia).

Figure 11: Smirdin’s The Library for Reading.

Sadovnikov’s watercolours could not have depicted Smirdin’s shop and printing house in the 1820s as it did not yet exist, but by 1835, as P. Ivanov was creating the lithographed scroll, the business’s omission would have been a glaring one, and the scroll has been updated accordingly. I. Kotelnikova suggests that the 1820s watercolours from the “sunny” side of the street were updated to reflect notable sights, but the “shady” side watercolours—closer in time to Sadovnikov’s original watercolours—were not.31

The first mass-circulation journal, The Library for Reading had a subscription base of 5000 by its second year, 1835. The journal was a monthly publication aimed at a broad middle-class readership, not just at the elite. Similarly, Smirdin’s bookshop on Nevskii Prospekt catered to a broad clientele, reflecting his business model.32 Large placards wrap around the building’s corner, with text in French and Russian. On the structure’s façade, most signs only give information in Russian. Signs wrap the building just under its balcony, and also appear in a second row, on either side of the central balcony. Below, a basement shop also has its own sign. On the other side of the building, just before the church, signs again wrap around the corner.

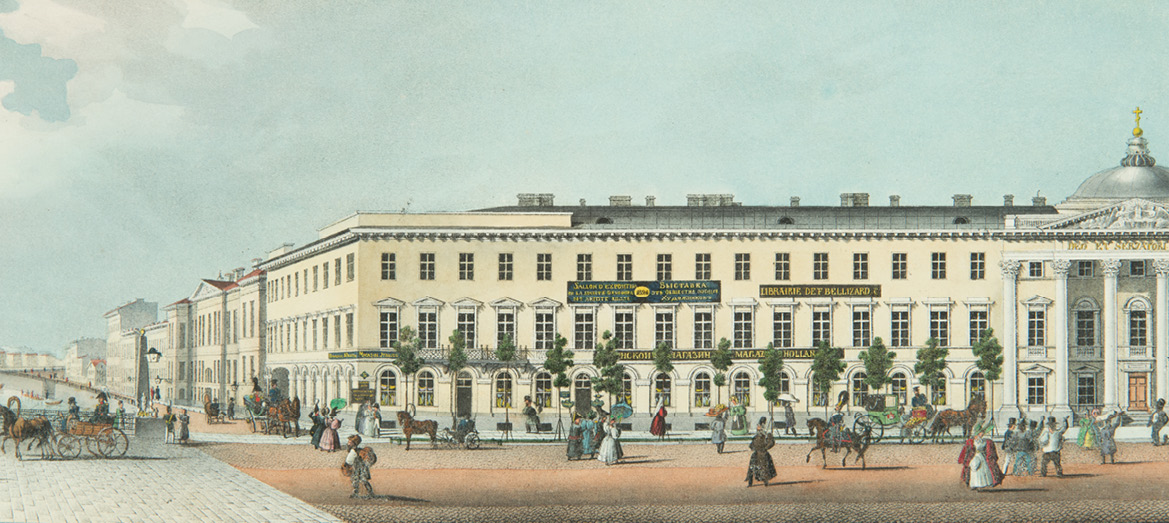

The contrast with Bellizard’s bookshop, passed earlier, is obvious. Smirdin’s operation occupies the majority of the building and includes multiple imprints of his business; their various signs mark and advertise the bookshop and the journal, but, also, as an ensemble give off a united sense of activity and industry. Bellizard’s sign simply labels his bookshop, showing its location to passers-by,33 but we must consider that Bellizard operates a relatively small bookshop and does a limited amount of publishing. Smirdin, on the other hand, is one of the most successful and influential of the St Petersburg publishers.

Figure 12: Bellizard’s bookshop.

His premises’ use of signage, like Rode’s, tells a great deal about his business. Smirdin’s profusion of signs renders his operation unmissable and unmistakable. His large building, its prominent location, and the fact that multiple businesses operate under its auspices (publishing, book selling, editing, journalism, etc.) all promote a sense of confidence and durability, something that many other publishers operating in Petersburg at the time did not have.

Shopping Arcades from the Shady Side

As we complete the stroll to the Anichkov Bridge and cross Nevskii to head back towards Palace Square, let us pause for a moment to reflect on the avenue’s history. The stroll along Nevskii so far has been characterised by a profusion of signs and goods, however, this informational deluge was not always characteristic of the street. In the city’s original plan, Nevskii Prospekt was not designated as a main shopping thoroughfare; rather, it was planned as a route for travellers entering the city by land, a main artery linking the wooden Admiralty—the heart of the city—with the Aleksandr Nevskii Monastery. However, it remained largely unbuilt into the eighteenth century. A plan in 1739 to construct a central market—the unrealised Mytnyi dvor—in the area shows the neighbourhood’s shift to a more commercial and utilitarian design. However, Nevskii’s prospects changed in the 1740s when a period of building activity transformed the street.

Empress Elizabeth chose the avenue for two building projects. Right now, from our position at the Anichkov Bridge, we stand before the first, the Anichkov Palace, built to commemorate her ascension to the throne, constructed between 1741 and 1754. The second was her own timbered Winter Palace, a temporary residence located back towards the present-day Palace Square that the empress inhabited while the now-famous stone Winter Palace designed by Rastrelli was constructed. Similarly, along the Fontanka in the neighbourhood near Nevskii, Elizabeth constructed her splendid summer palace.34 While neither Elizabeth’s winter nor summer palace survived even to the end of her successor’s reign, their location, as well as that of the Anichkov Palace, resulted in an increase in the street’s value for both residents and those seeking commercial enterprise.

Figure 13: Elizabeth’s summer palace, 1756.

Anxious to preserve the baroque complex she had become so fond of, in the 1740s and 50s Elizabeth passed several decrees affecting businesses and their shop signs in St Petersburg.35 Franklin goes into detail about decrees in his chapter in this volume, so I mention them only briefly here. In December 1742, she decreed that taverns and unsightly fruit and vegetable stands should be removed from the city’s main streets.36 In October 1752, she went on to order that no shop signs of any kind should remain on main streets,37 complaining, “There are a multitude of them for various trades, visible right opposite Her Majesty’s very courtyard”.38 These decrees had a significant impact on the appearance of St Petersburg’s streets. The result was the opulent look the empress desired on the capital’s grand boulevards (in decrees made later in October 1752, for example, she includes detailed descriptions of neoclassical monuments and canals she desires to construct). At the same time, however, these decrees reduced revenue for the many businesses along them. Shop signs seemed distasteful, markers of commerce and trade, which Elizabeth saw as vulgar.

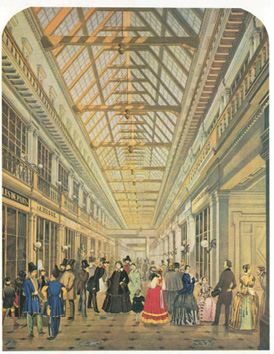

Possibly as a result of this, Elizabeth spearheaded the planning and construction of Gostinyi dvor, one of the earliest closed shopping arcades in the world (fig. 14). While closed shopping structures had existed in the Roman Empire, and the sixteenth-century Grand Bazaar in Constantinople provides a good example of them, Gostinyi dvor set out to enclose “avenues” lined with shops and stalls within a single façade, thus isolating commercial enterprise to certain areas and controlling the graphic display along Nevskii Prospekt. Gostinyi dvor—the “merchants’ yard”, which literally includes the word “gost”, meaning “guest” or, then, “foreign merchant”, in its name—was intended for foreign merchants, as were the so-called Nuremberg Stalls, one of the original shopping arcades along Nevskii, a row of stalls within the architectural arches of St Catherine’s Church dating from the 1780s (although designed from the 1760s onward), which we passed on our way to the Anichkov Bridge and can spy looking North and across the street from where we stand. From the words “guest” and “Nuremberg” we infer they host non-Russian merchants, although in practice both Russian and non-Russian tradesmen sold goods in them. Walking back up Nevskii, this time on the shady side of the street, we pass another planned commercial arcade, the Privy Cabinet Building. Dating from the early nineteenth century, it was planned with commercial space below and residential space above. Compared to the earlier façades we passed along Nevskii Prospekt, these are strangely empty of commercial signs, more closely tied into the neoclassical aesthetic vision.

While Elizabeth’s distaste for public signs and obstructed façades no doubt shaped the cityscape and helped spearhead the grand shopping arcade in Russia before many Western European countries adopted the model (the Gostinyi dvor predates even most Parisian arcades!), her decrees regulating commercial space did not stay in effect for long. Possibly recognising the difficulty of convenient trade if shops could not advertise their wares on their storefronts and artisans were consigned to the alleys and courtyards, Catherine II revoked Elizabeth’s decrees in March 1770. She added the stipulation, however, that the text and images on the signs meet the standards of “pristoinost′” (decency).39 Signs that suggested topics that polite conversation did not allow were forbidden: for example, depictions of men’s undergarments or funeral accoutrements. Catherine’s reversal of Elizabeth’s decrees resulted in the increased proliferation of shop signs on the capital’s main boulevards in the last decades of the eighteenth century. In this narrative we see a good example of the tension between the neoclassical aesthetics that represent authority in Elizabeth’s eyes and the need for information technology for trade.

Figure 15: Passazh exterior, 1848.

Looking back across the street from the Privy Cabinet Building, a fairly typical Nevskii view of neoclassical palace façades can be seen. In fact, these were demolished in 1848 to make way for another commercial building project. In their place, the Passazh shopping arcade was constructed. Whereas, in the Nuremberg Stalls, or the shopping arcades across the street, goods would have been largely lined up for view and sold that way, a more traditional model dating back to bartering, in the Passazh elite stores advertised their wares with signs, just as they did along Nevskii Prospekt itself. However, by the middle of the nineteenth century, the shopping arcade had become popular not because of imperial decree, but because of its benefits for merchants and consumers. Intriguingly, while some of the earliest shopping arcades feature on Nevskii Prospekt, the structures are much more closely associated with London and Paris, where they had their heyday in the 1820s and quickly passed out of fashion with the rise of the new department stores.40 In Russia, where department stores did not appear until the second half of the nineteenth century, the shopping arcade continued to thrive. While the old Gostinyi dvor was cramped, dark, and packed with crowds of people, the new Passazh allowed for a more pleasant shopping experience.

Figure 16: Passazh interior, 1850s.

Here, passing the many public buildings along the right, shadowed side of Nevskii Prospekt—for example the Public Library or the Grand Theatre—there is little in the way of signage, aside from images representing imperial power or simply a chiselled name. A statue of Minerva, Roman goddess of wisdom, adorns the library roof, overlooking the theatre square, a referential nod to the activity within the building. These institutions do not need to advertise; they all assume knowledge on the part of those seeking them out. Similarly, the construction of Gostinyi dvor, which we are just approaching now, also represents imperial authority: the attempted regulation of both commercial enterprise and its attendant array of signs and advertising. Those using the shopping complex would expect and need signs to understand what is for sale, but these are confined entirely within. The side facing Nevskii was known as the “Cloth Line” for the types of goods sold there, but only two small signs around the building’s corner suggest this activity. The sole sign that appears on the outer façade is the imperial eagle.

All along Nevskii Prospekt, the imperial double-headed eagle adorns pharmacies and notary public offices. In these examples we see the manifestation of authority as information technology, in the form of the imperial crest. This symbol of empire above a business marks that these premises are part of a state monopoly and carry the weight of legal authority behind them. However, they also underscore the proliferation of imperial power throughout the city, visibly demonstrating authority while asserting control over some commercial enterprises.

While the lack of shop signs in some areas exposes the tension between authority and the development of the commercial graphosphere, authority vis-à-vis information technologies is most clearly seen just beyond Gostinyi dvor, in the tower built onto the arcade housing silver traders, Silver Row. In Panorama, the tower looks like mere architectural embellishment, but it too had its function. On the next block, in the distance, the outline of the optical telegraph can be seen atop a building. The Silver Row tower was also part of this semaphore line, which represented cutting edge information transfer in the early nineteenth century. Brought into regular use by Napoleon, the optical telegraph was operated by manipulating the two antennae into a series of signs. An operator used a telescope to observe the signs, reproduced them at his own station, and thus passed the message on to the next station. The system worked well, enabling message transmission over hundreds of kilometres in minutes. By 1839, the network stretched from St Petersburg to Warsaw, and a message could be sent along the entire route and decoded in under an hour.41 The silhouette of the optical telegraph spied from Nevskii Prospekt is as telling as the imperial eagles over the notary public and apothecaries’ doors; it enforces authority and imperial omnipotence on a grand scale. Designed purely for official, bureaucratic use, the optical telegraph represents information technology as authority controlling the most efficient means of communication.

As we complete the stroll, we end on the steps of the Hotel London, overlooking Palace Square once more, the gold spire of the Admiralty shining above a troop of marching soldiers and several perambulating ladies wearing colourful hats and cloaks. The optical telegraph has taken us far afield from the public graphosphere, but it emphasises the importance of Nevskii Prospekt not just as a grand boulevard featuring imperial façades, fashionable shops and cafes, and public monuments, but as an information conduit, an encapsulated graphosphere. As the optical telegraph’s presence emphasises Nevskii’s role as a grand boulevard, so too does it emphasise the limitations of Sadovnikov’s watercolours as a source for capturing urban experience.

Looking Beyond Nevskii Prospekt

While Panorama projects a precise view of the street’s buildings populated with lively and whimsical characters, as a piece of urban representation it also has its limitations. Common aspects of St Petersburg life are omitted: chilly and inclement weather, the gloomy darkness of winter, the dirt of the streets, the noise of urban bustle, and the strong smells. Some omissions would be difficult to convey in two-dimensional printed format, of course, particularly those of an auditory or olfactory nature. Sadovnikov’s additions of carriages, animals, goods, and people do suggest motion, noise, and smells, and invite the viewer to imagine these omnipresent elements of urban life. However, the experience of Nevskii Prospekt without the rattle of carriages, the noise of the crowds, the sound of horse hoofs on the street, or the pungent and intense smells of urban space is already an incomplete, partially imagined one.

More important than the limitations of medium, however, is Panorama’s inherent limitation: its scope. On our stroll, we turned back at the Fontanka, and for good reason: even just across the river, still in view of the Anichkov Palace, the street’s grandeur deteriorates. Astolphe de Custine observes in his 1839 Letters from Russia,

A little below the bridge of Aniskoff […] The superb city created by Peter the Great, and beautified by Catherine II and other sovereigns, is lost at last in an unsightly mass of stalls and workshops, confused heaps of edifices without name, large squares without design.42

Custine’s view of the city is one that serves as a counterpoint to Sadovnikov’s. Custine’s travel memoir praises some aspects of St Petersburg, but his overall impression is unfavourable. Sadovnikov’s watercolours, on the other hand, deliberately omit less than pleasing urban scenes; an “unsightly mass” would not be in keeping with the scroll’s aesthetic. And, indeed, Sadovnikov’s gaze turns back at the Anichkov Bridge. While Nevskii Prospekt—or at any rate its fashionable section—is meticulously documented by artists like Sadovnikov, the little we know about street signs elsewhere paints a very different image of the experience of the public graphosphere.

Most of the information scholars have about off-boulevard street signs from this period comes from physiological writing. One anonymous author, writing in Literaturnaia gazeta in 1845, notes: “I would go out to see other signs beyond the gate […] where […] they just say ‘En trence to eatery’ or ‘To restrunt’, while above it the painter had, with a free hand, shown a ham with a paper frill, a suckling pig, a plate full of meat pies, fresh eggs, huge cutlets, tea with a Chinese figurine, i.e. whatever you might want”.43 These misspellings and the freedom of the signmakers off the grand boulevards shows both the potential of the public graphosphere—the sign’s message is more important than its grammar or language—and its relative freedom. Intriguingly, there are misspelled signs apparent in Sadovnikov’s Panorama as well—in some cases French is misspelled, and in some cases Russian is—but the artist documents them by rote. The Literary Gazette writer, on the other hand, revels in them as a unique expression of free spirit.

It is within this atmosphere that the tradition of wordplay and folk painting in shop signs developed, sidestepping the grand boulevards and augmenting the previously largely graphic examples. In his Tales of Belkin, in “The Undertaker” (Grobovshchik, 1830), Pushkin, for example, gives an example of a street sign:

Over the gate hung a sign depicting a plump cupid with a downturned torch in his hand and bearing the inscription: ‘Plain and painted coffins sold and upholstered here. Coffins also let out for hire and old ones repaired’.44

Pushkin’s imagined sign is nothing like the signs on Nevskii. Its image is not utilitarian, but more suggestive. The language of the sign is playful, and intended to be so—Pushkin ironises it in his story, but this kind of playful language was prized on street signs off the grand boulevards at this time.

One of the best records of street signs from this period appears in the journal Illustration (Illustratsiia) in 1848, in the article “Petersburg Shop Signs” by an anonymous contributor known only by the initial “T”.45 This admirer of street signs from the non-affluent areas of the capital extols their “primitive character”, and points out the humour and folk traditions that frequently crop up among them. In one example, the anonymous author relates:

The sign of Smekayev’s tobacco shop depicted the following scene: on one side a gentleman was sitting at a small round table holding a glass in his hand, on the other a lady was handing the man a pipe and trying to take his glass away. Underneath was the quatrain clearly showing a knowledge of folk ways:

Have a smoke instead of wine,

A pipe will make you feel so fine,

I guarantee you’ll get so stewed,

You’ll swear you’d drunk a pint or two.

In the windows of hairdressers and barbershops, ladies and men’s busts were displayed with a sign saying: ‘We cut hair, and comb and shave—have yourself bled according to the latest journal’.46

The irony of these snippets—“you’ll swear you’d drunk a pint or two” or “have yourself bled according to the latest journal”—recalls Pushkin’s fictional shop signs, which play on fashion and good-natured humour. This inventive language evokes the tradition of lubok, woodcuts which predate the influx of Western European models of shop signs found on the grand boulevards.47 It is these so-called “eccentric” signs that fascinate this anonymous physiological voyager-author, and they provide a different set of information about urban life and experience than the neoclassical façades and fashionable, elegant signs we see in Sadovnikov’s watercolours.

“T” gives a short history of shop signs in Russia, which aligns with the graphosphere observed along Nevskii in Panorama. According to “T”, signs originally captured the act of trading in addition to images of the goods for sale themselves. He observes:

Thus, over a fabric shop there would be a picture of a merchant standing in front of a pretty purchaser. Inn signs often show Russian men sitting in orderly fashion at a table laid with a tea set or with zakuski (savoury snacks) and decanters; painters paid particular attention to the figure, making them pour out and drink tea in very grand poses which were not, of course, usual to the habitués of such places.48

For a physiological writer, the history of signs is of interest as it is a history of urban communication. “T” stresses the central role of information transfer, commenting:

Now the figures were replaced simply by objects which speak for themselves—the tea set, snacks and decanters; fabric shops have signs which depict various kinds of material, and others give only the merchants name.49

These “speaking” signs sound very similar to those found along Nevskii.

“T”, however, is less interested in these standard signs. His passion is for the “eccentric” signs—not just the misspelled ones, or those featuring folk humour. Some of those collected in the article show his bonhomie: he takes pleasure in the small details of signs, treating them as artworks (“Beer-stalls had signs with bottles of beer, foaming as the cork pops”50), while emphasising their communicative meaning (“We also find the inscription ‘Sale for consumption on the premises’, indicating that beer, porter, and honey could be drunk in the shop itself”.51). Depicted through “T”’s marvelling eyes, the signs come whimsically to life: a coachman in a blue kaftan doffs his cap to passers-by; grocery shops have exotic views of China taken from tea chests, evoking distant lands; and, perhaps most amazing of all, “Meat shops showed not only bulls, rams, and chickens eating lush grass, but also the slaughter itself. On one sign of this type (in Spassky Lane) the artist painted all the letters of the inscription from different cuts of meat”.52 These signs clearly demonstrate the creative liberty that emerged in advertising as merchants worked to discover ways to outstrip competition and communicate their message to customers in the most attractive way possible—even if that way involves spelling out your business name with different meat cuts.

The signs we have seen on Nevskii in Sadovnikov’s watercolours seem to show a definite progress along Western European models, but these off-boulevard signs seem derived from folk traditions or pre-eighteenth-century depictions of goods for sale. From these descriptions, we can see the limitations of using a resource such as Sadovnikov’s scroll exclusively to gain an understanding of the scope of the public graphosphere, which sprawled well beyond Panorama’s bounds. While Sadovnikov’s watercolours do provide some insight, one must go off-boulevard like the anonymous physiological author to sketch in additional details and strands, and, even then, the experience remains incomplete.

In 1835, a reviewer was inspired by the scroll to proclaim, “Nevsky Prospekt is without a doubt the finest street in the world, for its regularity and its remarkable length and breadth, as well as for the beauty and majesty of its buildings […] a poet could confidently proclaim Nevsky Prospekt the soul of St Petersburg”.53 This reading of Panorama emerges from the work’s inherent aristocratic point of view. The “regularity, remarkable length and breadth, beauty and majesty of buildings” all toe the imperial line. Furthermore, these remarks resemble Custine’s comment on St Petersburg architecture, “The line and rule figure well the manner in which the absolute sovereigns view things”.54 The public graphosphere, however, resists categorisation and containment, and, similarly, complicates the imperial perspectives and rectilinear prospects typically associated with St Petersburg’s planned design.

Refractions and Reflections

For those who viewed Panorama of Nevskii Prospekt in 1835, the scroll provided a new way of sharing urban life with others, of capturing a slice of the elegant street, featuring neoclassical façades, modish shops and even a glimpse of cutting edge technology such as the optical telegraph or celebrities like Pushkin. An anonymous visitor to St Petersburg in the 1840s called Nevskii Prospekt “a kind of picture gallery”,55 conflating city with artistic object, just as the scroll creates art out of urban experience. Viewers at the time would have been conscious of this way of seeing the city; just before the optical telegraph, the scroll itself includes the “Rotunda”, the home of Madame la Tour’s Panorama (recognisable by its distinctive lantern). This popular attraction on Bolshaia Morskaia Street was one of the first panoramas, on display here in the 1820s. Madame La Tour’s allowed visitors to experience cutting-edge nineteenth-century optical entertainment such as panoramas, cosmoramas, and an attraction called the “theatre of light”—early forerunners of the cinematograph.56

Figure 17: Madame La Tour’s Panorama and the Optical Telegraph.

In another account of Nevskii Prospekt from 1835, Nikolai Gogol writes of the street as a “great mixer” in his story that bears the street’s name. His subject matter is grittier than Sadovnikov’s idealised cityscapes, dealing as it does with prostitution, poverty, suicide, and crime; he begins his story with an ironic exclamation that echoes that of the anonymous Panorama reviewer: “Nothing could be finer than Nevsky Prospect, at least not in St Petersburg; it is the be-all and end-all. It positively gleams and sparkles—the jewel of our capital!”57 Gogol’s characters’ urban experience differs from that of the figures in Sadovnikov’s watercolours: Gogol’s “Nevskii Prospekt” features a grotesque ultimate scene in which the devil lights the lamps along the avenue, surrounded by darkness, with occasional dim lights illuminating the dull yellow fog. Gogol knew of Panorama, and even sent a copy to his mother, although his representation of the city differs greatly from Sadovnikov’s limpid blue skies. Still, in giving his mother the scroll, Gogol not only sent home a souvenir of his life in the capital, but also passed along one experience of Nevskii Prospekt, enabling his mother, too, take a “stroll”.

For us, viewing the scroll nearly two hundred years later, Panorama provides a rare visual account of Russian urban space in the 1820s. However, for our discussion of Sadovnikov, Nevskii Prospekt, and the public graphosphere, it is prudent to mention the limitations of using works like Panorama to draw conclusions about early nineteenth-century shop signs. The information we glean from our “stroll”, is constrained by the fact that, typically, only beautiful, grand, or historical urban spaces were subjects of artworks during this period. Sadovnikov does illustrate a deeper perspective at cross streets, allowing the viewer to look beyond the famous boulevard, which suggests the city beyond Nevskii Prospekt, but the street remains the central focus. Some works existed that depicted street life if not street signs, like, for example, the monthly anthology “Magic Lantern”, which came out at the same time as Panorama. The full title is “Magic Lantern, or a Spectacle of St Petersburg’s Travelling Sellers, Masters, and Other Folk Craftsmen, Depicted with a True Brush in their Real Clothes and Presented Conversing with One Another, Commensurate With Each Person and Title”.58 This detailed description’s emphasis on veracity (“a True Brush”, “their Real Clothes”) and the lower classes going about their daily business anticipate the trend of physiological depictions of slums and lower class areas, demonstrating the relatively new notion that representations of the lower classes were necessary for a complete and authentic picture of urban life. In the next decades, as the technology of photography developed alongside physiological writing, a much broader and more intricate picture of the public graphosphere becomes possible.

1 This research was made possible through support from the University of Cambridge and the Hampton Fund at the University of British Columbia. An earlier version of this chapter was presented at the Humanities and Social Sciences seminar at Darwin College, Cambridge, in October 2014 and I am grateful to those present for their helpful feedback. I am indebted to Connor Doak, Tatiana Filimonova, Simon Franklin, and Alexander M. Martin for their constructive comments on earlier drafts of this chapter. Additionally, I wish to thank Viktoria Ivleva, with whom I consulted on several research queries about nineteenth-century Russian trade cards and shopping arcades. The images from Panorama that illustrate this chapter appear with permission from the State Russian Museum, St Petersburg, and I thank Yulia Khodko for her assistance in obtaining them.

2 Only two fragments of the original watercolour scrolls exist, one in the National Library of Russia, St Petersburg, and the other in the National Pushkin Museum, St Petersburg. Together they comprise only about a fifth of the complete Panorama. Additionally, Sadovnikov’s preparatory sketches in ink have been preserved in the State Russian Museum, St Petersburg, and in the State Museum of the History of St Petersburg.

3 When describing Sadovnikov’s work here and throughout, I refer to V. S. Sadovnikov, Panorama of Nevsky Prospect: From the Collection of the Russian Museum, ed. by Nataliia Shtrimer (Leningrad: Aurora Art Publishers, 1993). This edition consists of a good quality reproduction of the scroll broken up into coloured plates. The 1974 edition, also published by Aurora Art Publishers, is a smaller scale black and white reproduction of the original lithographs and some of the image details are difficult to make out.

4 In the original announcement, in Literaturnaia gazeta, no. 15 (1830), the dimensions are noted: “around ten arshins long and six vershoks wide” (okolo 10 arshin dlinoiu i 6 vershkov shirinoiu).

5 I. Kotel′nikova, ‘Introduction’, in Panorama of Nevsky Prospekt (Leningrad: Aurora Art Publishers, 1974), p. 8.

6 Kotel′nikova, ‘Introduction’, p. 32.

7 Julie A. Buckler describes several of these works in the context of the Nevskii Prospekt literary tradition in Mapping St. Petersburg: Imperial Text and Cityshape (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), pp. 83–88.

8 For more information about the development of both the panorama and Sadovnikov’s Panorama, see Tatiana Senkevitch, ‘The Phantasmagoria of the City: Gogol’s and Sadovnikov’s Nevsky Prospect, St Petersburg’, in The Flâneur Abroad: Historical and International Perspectives, ed. by Richard Wrigley (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014), pp. 171–74. Senkevitch’s study uses Sadovnikov’s Panorama of Nevskii Prospekt and Gogol’s story ‘Nevskii Prospekt’ to explore notions of vision, perception, spatial dynamics, architectural and urban planning history, and the imagined city.

9 Senkevitch, ‘The Phantasmagoria of the City’, p. 176.

10 Buckler, Mapping St. Petersburg, p. 84.

11 Ibid.

13 Buckler, Mapping St Petersburg, p. 29.

14 Ibid., p. 84.

15 The designation of “free unclassed artist” was granted with a small silver medal from the Imperial Academy of Arts and could be given to artists unaffiliated with the Academy. In Sadovnikov’s case, his medal was granted for being self-taught and practicing perspective landscape painting independently. The designation of “classed”, “unclassed”, or “free unclassed” artist from the Academy was required at that time to work professionally as an artist. For more information on serf artists’ classifications during this period, see Richard Stites, Serfdom, Society, and the Arts in Imperial Russia: The Pleasure and the Power (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), pp. 325–27.

16 For more on Sadovnikov’s life and works, see O. Kaparulina, Vasilii Semonovich Sadovnikov (St Petersburg: Palace Editions, 2000).

17 Yuri Egorov, The Architectural Planning of St Petersburg, trans. by Eric Dluhosch (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 1969), pp. 204–05.

18 Kotel′nikova, ‘Introduction’, p. 32.

19 William Craft Brumfield, ‘St Petersburg and the Art of Survival’, in Preserving Petersburg: History, Memory, Nostalgia, ed. by Helena Goscilo and Stephen M. Norris (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008), p. 1.

20 Senkevitch, ‘The Phantasmagoria of the City’, p. 169.

21 Théophile Gautier, Voyage en Russie, Vol 1 (Paris: 1867), pp. 124–25. The translation I use appears in Alla Povelikhina and Yevgeny Kovtun, Russian Painted Shop Signs and Avant-Garde Artists, trans. by Thomas Crane and Margarita Latsinova (Leningrad: Aurora Art Publishers, 1991), p. 23.

22 On Russian elites, luxury, and Western European connections, see Alexander M. Martin, Enlightened Metropolis: Constructing Imperial Moscow, 1762–1855 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 161–67.

23 On advertising and the development of guild and shop signs in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Russia, see Eleonora Glinternik, Reklama v Rossii XVIII–pervoi poloviny XX veka (St Petersburg: Avrora, 2007), pp. 12–51. On advertising in Imperial Russia, see Sally West, I Shop in Moscow: Advertising and the Creation of Consumer Culture in Late Tsarist Russia (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2011).

24 On advertising in antiquity, see V. V. Uchenova and N. V. Starykh, Istoriia reklamy: detstvo i otrochestvo reklamy (Moscow: Smysl, 1994), pp. 9–20.

25 On the development of signs in Western Europe, the classic study is Jacob Larwood and John Camden Hotten, The History of Signboards from the Earliest Times to the Present Day (London: John Camden Hotten, 1867), especially pp. 1–44. See also Uchenova and Starykh, Istoriia reklamy, pp. 21–37 for a history of advertising in medieval Western Europe more broadly.

26 Adam Olearius, Vermehrte Newe Beschreibung Der Muscowitischen vnd Persischen Reyse, So durch gelegenheit einer Holsteinischen Gesandschafft an den Russischen Zaar vnd König in Persien geschehen (Schleswig: Johan Holwein, 1656), p. 224. Olearius describes merchant culture and trade in seventeenth-century Moscow.

27 Povelikhina and Kovtun, Painted Shop Signs and Avant-Garde Artists, pp. 16–17. Povelikhina and Kovtun’s work is not a history of shop signs, but a study of the ways nineteenth-century and earlier painted shop signs influenced Russian avant-garde artists. Their introduction to the volume gives a history of the development of the shop sign in Russia.

28 For more information about the introduction and development of guilds in Russia, see Roger P. Bartlett, Human Capital: The Settlement of Foreigners into Russia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979), pp. 147–49. For information about St Petersburg guilds, specifically, see George E. Munro, The Most Intentional City: St Petersburg in the Reign of Catherine the Great (Cranbury: Rosemont Publishing, 2008), pp. 215–24.

29 Povelikhina and Kovtun, Russian Painted Shop Signs and Avant-Garde Artists, p. 17.

30 Now called Green Bridge, the bridge held the name Police Bridge from 1768–1918.

31 Kotel′nikova, ‘Introduction’, p. 65.

32 For more about The Library for Reading and Smirdin’s publishing model, see V. G. Berezina et al., Istoriia russkoi zhurnalistiki XVIII–XIX vekov (Moscow: Vysshaia shkola, 1963), pp. 169–74, p. 295. Melissa Frazier has analysed the journal’s impact on readers and writers of its era with a focus on its editor, Osip Senkovskii; see Frazier, Romantic Encounters: Writers, Readers, and the ‘Library for Reading’ (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2007). For a literature review of sources on various aspects of Smirdin’s business, see George Gutsche, ‘Dinner at Smirdin’s: Forces in Russian Print Culture in the Early Reign of Nicholas I’, in The Space of the Book: Print Culture in the Russian Social Imagination, ed. by Miranda Remnek (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010), pp. 74–75.

33 As I mentioned earlier, the Panorama’s most famous passer-by is Pushkin, who can be seen walking past Bellizard’s shop in Figure 12.

34 Buckler, Mapping St Petersburg, p. 82.

35 For a somewhat subjective version of this narrative, see P. Antonov, ‘Vyveski’, Neva, 4 (1986), 183–88 (p. 186).

36 Polnoe sobranie zakonov Rossiiskii imperii, Series 1 (1649–1825) (hereafter PSZ 1), no. 8674. For more details about these decrees, see Franklin’s discussion in Chapter 11 of the present volume.

37 PSZ 1, no. 10032.

38 Antonov, ‘Vyveski’, p. 186; the translation of this quotation is from West, I Shop in Moscow, p. 22.

39 PSZ 1, no. 13421.

40 Anneleen Arnout, ‘Something Old, Something Borrowed, Something New: The Brussels Shopping Townscape, 1830–1914’, in The Landscape of Consumption: Shopping Streets and Cultures in Western Europe, 1600–1900, ed. by Jan Hein Furnée and Clé Lesger (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), p. 172.

41 On the optical telegraph in Russia, see D. I. Kargin, ‘Opticheskii telegraf Kulibina’, Arkhiv istorii nauki i tekhniki. Trudy instituta istorii nauki i tekhniki. Seriia 1. Vypusk 3 (Leningrad: Izdatel′stvo Akademii nauk SSSR, 1934), pp. 77–103.

42 Astolphe de Custine, Letters from Russia, the 1843 translation edited and introduced by Anka Muhlstein (New York: New York Review Books Classics, 2002), p. 215.

43 Anonymous, Аppendix to ‘Zapiski dlia khoziaev’, Literaturnaia gazeta (1845), quoted in Povelikhina and Kovtun, Russian Painted Shop Signs and Avant-Garde Artists, p. 23.

44 Alexander Pushkin, ‘The Undertaker’, Tales of Belkin and Other Prose Writings, trans. by Ronald Wilks (London: Penguin Classics, 1998), p. 33.

45 ‘T’, ‘Peterburgskie vyveski’, Illiustratsiia, 30. 4–7 (28 August 1848), 81–82.

46 ‘T’, ‘Peterburgskie vyveski’, p. 81. Translation adapted from that in Povelikhina and Kovtun, Russian Painted Shop Signs and Avant-Garde Artists, p. 28.

47 For an overview of lubok as advertising material, see Uchenova and Starykh, Istoriia reklamy, pp. 52–53. Iurii Lotman also provides insight on the folk tradition of the lubok within the commercial realm in ‘Khudozhestvennaia priroda russkikh narodnykh kartinok’, in Narodnaia graviura i fol′klor v Rossii XVII–XIX vv., ed. I. E. Danilova (Moscow: Sovetskii Khudozhnik, 1975), pp. 257–58.

48 ‘T’, ‘Peterburgskie vyveski’, 81.

49 Ibid.

50 Ibid.

51 Ibid.

52 Ibid.

53 A review of Panorama of Nevksii Prospekt that appeared in Severnaia pchela. Quoted in Kotel′nikova, ‘Introduction’, p. 8.

54 Custine, Letters from Russia, p. 213.

55 Quoted in West, I Shop in Moscow, p. 23, who cites Povelikhina and Kovtun, Russian Painted Shop Signs and Avant-Garde Artists, p. 23, who provide no citation.

56 See Nataliia Shtrimer’s annotations to Panorama of Nevsky Prospekt (1993), ‘The Left, Sunny Side’ Card 11 for more information on the Panorama of Madame la Tour.

57 Nikolai Gogol, ‘Nevsky Prospect’, Plays and Petersburg Tales, trans. by Christopher English (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), p. 3.

58 For more information about ‘Magic Lantern’, see Solomon Volkov, St Petersburg: A Cultural History (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997), pp. 60–61.