2. New Technology and the Mapping of Empire: The Adoption of the Astrolabe

© 2017 Aleksei Golubinskii, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0122.02

In the eighteenth century, interest in and the intensification of support for science became a part of everyday life in the courts of Europe. Russia, too, was caught up in a fascination with science from the Petrine era onwards. Besides scientific exchange, signs of scientific interest were apparent in a variety of areas of Russian life, from the introduction of new ideas, books, and instruments, to the systematic invitation of foreign scientists and academics to act as consultants, advisors, and teachers.2 As a result, Russia’s role in international affairs became more pronounced, and the representation of Russian territories became increasingly important for geographers both in Russia and abroad.3 To a notable extent the achievements of the St Petersburg Academy of Sciences in the interrelated fields of geography and astronomy contributed to this. The links between the scientific communities in the Russian Empire and abroad stabilised, but, at the same time, were shaped by external political affairs.4

As this chapter will discuss, the purchase of British astrolabes5 by the Russian Empire demonstrates non-commercial international cooperation during the period when the signing of the Westminster Treaty in 1756 had significantly complicated relations between Russia and Great Britain. While the details of Russia’s procurement of complex technology during this period have not as yet attracted the sustained attention of historians, this case study is a key episode in the “scientific” turn in Russian cartography, which follows on from Valerie Kivelson’s study of pre-modern mapping techniques in the previous chapter of this volume. As this chapter demonstrates, the introduction of geodesic astrolabes, first from abroad, then through local manufacture, enabled the modern mapping of empire in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Astrolabes were essential to determine directions (angles) accurately and to calculate areas. They enabled Russian and European cartographers to produce relatively precise maps. Accurate mapping was of interest not only to geographers but also to astronomers, physicists, biologists and ethnographers, indeed to all who espoused the encyclopedic approach to scholarship that was typical of the eighteenth century. Precise representation of territory helped to enhance the orderliness of territorial administration and provided better information for use at the state level.

The production of astrolabes was quite knowledge-intensive. It required high-quality raw materials (metal and wood), a well developed manufacturing culture, precise measuring instruments, and well trained staff. In order for astrolabes to be produced in Russia in large quantities, improvements were needed in all these areas. The processes through which astrolabes were in the first instance acquired from abroad, and then manufactured in Russia, stand as an example of international exchange and of the adoption of technical expertise in an important area of information technology.

The Russian Imperial procurement of astrolabes from abroad made possible the creation of the largest government project to describe the territories of the Russian Empire, the Russian General Land Survey, which commenced from the middle of the eighteenth century. Over the course of the survey, six hundred thousand maps were produced in the scale 1:8400, as well as a total of more than 1.3 million documents. Generalised maps of Russia created on the basis of these maps began to filter into the West, and became the first relatively sound evidence for the actual configuration of land in Northeast Eurasia.

Attempts to carry out a universal survey of Russia’s territories had also taken place in the first quarter of the eighteenth century. However, this survey still depended on mapping instruments inherited from the seventeenth century, which were not up to the standard required in the new era. Thus, during the Petrine period, the Academy of Sciences in St Petersburg began to attract foreign scholars who could help to introduce a modern culture of science.6 Among them was the French astronomer and geographer Joseph-Nicolas Delisle. His name and that of Senate Ober-Secretary I. K. Kirilov are linked with the first attempts to create generalised (that is small-scale, general) maps of Russia. Among Delisle’s proposals was the greater use of astronomical observations in order to increase the accuracy in defining geographical coordinates, and a wider distribution of instrumental land surveys. His work also included the creation of new instruments, for which the French master of instruments Pierre Vignon was brought to Russia along with Delisle.

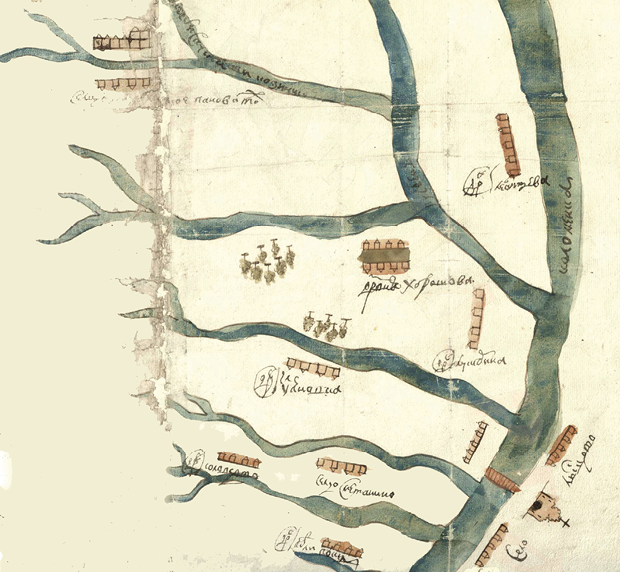

Figure 1: Plan of 1699 of the environs of Kolomna. Fragment.7

Towards the middle of the century, the demand for maps of Russia was so great that there was international competition for the rights to astronomical and geographical data on the Russian Empire. The publication of material about Delisle’s new geographic data precipitated a scandal since publication had been expressly forbidden by the Senate. In 1752 Delisle prepared a new map of Russian exploration that included the results of his first and second Kamchatka expeditions.8 G. F. Müller, one of the academicians of the Academy of Science in St Petersburg, was ordered, under threat of dismissal, to compose a “thorough refutation” for foreign journals and to concentrate on publishing new maps as soon as possible—both a general map and various specialised maps—taking into account the latest discoveries, of which Delisle could not know. Leonhard Euler, also a distinguished member of the Academy, was forced to distribute this letter to various scientific journals under threat of being deprived of his pension.9 Another example of such competitiveness occurred in relation to a discussion of the fourth volume of Novi Commentarii Academiae Scientiarum Imperialis Petropolitanae, the official periodical publication of the St Petersburg Academy of Sciences. A. N. Grishov, the director of the Astronomical Observatory, requested the early publication of his research into the parallax of the moon according to observations from St Petersburg in 1752 and the coinciding observations at the Cape of Good Hope, so that French scholars could not beat Russian scientists to it.10

In view of this situation, the Russian government began to turn its own attention to surveying. However, in addition to knowledge of how to make accurate measurements of the land, instruments themselves were required. Among these, the most important was the astrolabe, the device required for measuring angles and hence for producing calculations which are crucial for defining boundaries between pieces of land.11 Astrolabes may have appeared in Russia long before the era of Peter the Great, but they achieved comparatively widespread use during his reign. The first specimens of seventeenth-century astrolabes that appeared in Russia most likely resembled that illustrated in Figure 2:

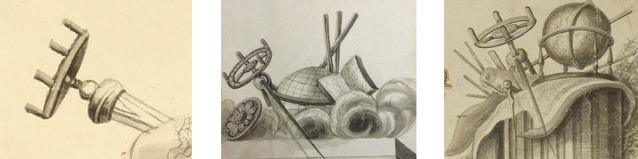

Figure 2: A universal astrolabe (semicircumferentor) with compass. Manufactured in the middle of the seventeenth century.12

The type and precise specification of astrolabes used for carrying out the General Land Survey is unknown. No examples of surveying equipment from the first half of the eighteenth century have been preserved either in the collections of the Moscow State University of Geodesy and Cartography, or in the Military-Historical Museum of Artillery, Engineer and Signal Corps in St Petersburg. The impression of what astrolabes of the period looked like is based on drawings found on the decorative borders of maps of Russian districts (uezdy) and towns.

Figure 3: Depiction of astrolabes (circumferentors) on the maps of the General Land Survey.13

In the first instance the astrolabe is depicted in profile, and the two other examples show that the astrolabe with compass was used, i.e. the type that could produce a measurement not only of angles between two lines, but also in relation to the position of the earth.14

Before the beginning of the General Land Survey, there was not enough equipment to carry out the project. For the creation of a full equipage of astrolabes and to assist the studies of future surveyors, four astrolabes and measuring chains were purchased by the Admiralty College (Admiralteistv-Kollegiia) in 1754.15 At first astrolabes were bought to Moscow to the Provincial Office of Surveying, and afterwards were placed at the Admiralty school.16

Figure 4: The Surveying Process. Two surveyors, armed with an astrolabe, apparently corresponding to those imported from England, measure the boundaries between plots of land. The head of the surveying party (with a sword) looks at the astrolabe and his assistant with a field notebook adjusts it. On their left is a man with a cane (the attorney of the landowner) and in the left corner of the picture is a peasant with a measuring chain ten fathoms in length. Fragment of a map of Iaroslavl Province.17

At the same time, the question arose of Russian and foreign involvement in the production of astrolabes. Initially, in May 1754, the Senate sent the Academy of Sciences and the Admiralty College an order to manufacture two hundred astrolabes.18 It was clear that the Russian makers of astrolabes could not keep up with demand, so the only solution was to turn to makers abroad. The Russian ambassador in London, Count P. G. Chernyshev, received an order (ukaz): “we must get a hundred astrolabes without spirit levels from England […] with geodesic instruments”, and “having bought the requested geodesic instruments, send them here at once at the Crown’s expense”.19 The reference to geodesic instruments in the first message refers to both astrolabes and measuring chains, but, as became apparent later, with regard to chains, the Russian makers could achieve the required volume manufacture on their own. Emphasising the urgency of the work, the Senate added: “And if the one hundred astrolabes required cannot be bought at once, then buy as many as you can now, and the rest later, but buy them as soon as possible, because they are extremely necessary and their absence from this summer’s delivery has meant that in Moscow Province the surveyors have had to halt work”.20

Were the astrolabes that had been ordered up to standard with the current level of technological development? In answering this question, it is necessary to say that in France at roughly the same time, the same type of instruments were in general use. These were distinguished by their simplicity, and the absence of additional elements such as a spyglass or telescope, for example. The most necessary accessory to the astrolabe was a compass, which had been requested in order to increase the accuracy of measurements.21

In the Academy of Sciences, three astrolabes were already nearly finished. Immediately after their completion at the Academy, the Senate paid two hundred rubles to increase production.22 Metal for the astrolabes was ordered from the director of the Schlisselburg copper factory, Franz Ludwig Popp. Having agreed to make the astrolabes in the rough, i.e. without wooden parts (oak or palm wood) and without detailed finishing touches, he asked that for every pood (approx. 16.3 kilograms), he be given eleven rubles and ninety kopeks for all large-scale detail and sixteen rubles each for fine finishing detail.

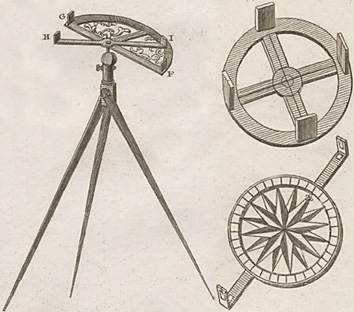

Figure 5: Engraving from Recueil de planches sur les sciences, les arts libéraux et les arts méchaniques (1765–72).23

Further work on the astrolabes, including the addition of wooden parts, occurred at the Academy of Sciences. The government’s perception of the order’s importance can be seen in the speed of payment: the instruments were paid for from the Treasury (the College of State Expenses—Shtats-Kontor-Kollegiia) almost at once.24 As a result of such urgency, the manufacturers had to make the simplest instruments with dioptras [a surveying tool originating in the ancient world], omitting any telescopic elements.25

Almost immediately the problem of a lack of skilled personnel became apparent. The Academy did not have sufficient engineers with the necessary qualifications. An order from this period reads, “Due to the lack in the Academy of the type of craftsmen skilled in making scientific instruments, send Filip Tiriutin to other institutions so he can seek out those capable of this type of work, and investigate those he finds with a level of skill and availability; moreover, he should seek out free craftsmen, and reach an agreement with them at the chancery about the price per item and set them to work”.26 The team of workers was gathered from many government institutions, “Tiriutin’s apprentices made a report to the office of the Academy of Sciences declaring that they found qualified workers in state positions to help make astrolabes, specifically: in the main artillery, the instrument-maker Aleksei Dmitriev; the two coppersmiths, the Spiridon Kukin brothers; in the Naval Academy, the instrument maker Grigorii Mogilev, and the turner Petr Spalskoi”.27 Those working on the astrolabes were not permitted days off, and by January 1755 twenty-four astrolabes had been completed.28

Meanwhile the Russian Ambassador to London, Chernyshev, wrote that “…although I have continuously visited a large quantity of London mathematical experts famous for the quality of their work, […] I have not found a corresponding number of finished astrolabes and additional instruments”.29 It became clear that sending the pieces from London that year as ordered would not work. The distribution of orders between different craftsmen did not help. The timely dispatch of the astrolabes was also an important issue in light of the late thawing of ice in the port of St Petersburg. Delays for this and other logistical reasons were entirely possible, so Chernyshev suggested that they be sent “to Hamburg, Lübeck or Danzig by water, and shipped from there to St Petersburg over dry land, since by this method they may arrive by the beginning of the following spring”.30 Another reason to hasten the delivery was the absence of customs duties, which occurred with other government deliveries and even sometimes in cases of private procurement in which the state was particularly interested.31 Insufficient financial means was also an obstacle to the speedy fulfilment of the order: the initial deposit “of a thousand rubles from the College of Foreign Affairs for the transfer still require[d] a bit less than twice that sum”.32

In July 1755 a discussion took place in the Senate about which method of delivery to choose. The State Surveyor General-in-Chief and Cavalryman Count Petr Ivanovich Shuvalov said that importing one hundred astrolabes from England together with the Øresund customs duty (for passage across the Strait of Øresund) would cost twenty-one rubles and sixty-seven and a quarter kopeks for each, while the astrolabes made in the Academy of Sciences cost around forty rubles apiece. In connection with this, he suggested the Academy of Sciences should not make any more astrolabes, apart from finishing those on which work had already begun.33 As a result, the idea of ordering another nine hundred astrolabes from England came about, but “to send as many as can be found in parts and prepared without making known the full number required… so that they will not increase the price”.34

The new Ambassador to England, A. M. Golitsyn, wrote that “the craftsmen there do not at present have the finished astrolabes, and they cannot complete even a small proportion of them for dispatch by the maritime route. The contracts signed with them stipulate that all the astrolabes should be made with the appropriate protractors; that they be of the same quality and in the same working order as those that were previously sent from there; and that they should not cost more than the previous price, that is, four pounds and ten shillings sterling each; that these craftsmen should produce a total of one hundred and thirty astrolabes per month; thus it is expected that all nine hundred should be ready by April of 1756”.35 The total cost of the contract stood at 20,773 rubles and forty kopeks and was paid by the Treasury from a sum which had been designated for “emergency expenditure”.36

In order to imagine the magnitude of this sum, we can turn to a contemporary example. Jean Armand de L’Estocq, director of the Medical Chancery during Elizabeth’s reign, asked to be provided with an assistant doctor “experienced in administrative matters, for the administration of the office of medical affairs under my direction”, and also to confirm the new budget, “an overall sum for salaries and for the maintenance of that chancery and of the pharmacies” (medicine was for the most part obtained from abroad). To cover the cost of sixty employees in St Petersburg and Moscow and other expenses, 7,431 rubles was required.37 In another example, on 16 March 1755, the rector of Moscow University, A. M. Argamakov, said that the empress was bestowing four thousand rubles on the university library and asked the professors for advice on obtaining books. The sum of one thousand rubles was additionally to be spent on the acquisition of equipment.38 However, despite its magnitude, the cost of the contract for the astrolabes was no more than 0.5% of English imports to Russia, so scholars who analyse export and import, dividing it into up to twenty categories, do not separate out the import of goods connected with knowledge-based technology.39

The precise date of the delivery of the instruments is unknown, but the report on the execution of the order, presented on 27 August 1756, includes information that “recently these astrolabes arrived”.40 The government had in vain tried to hurry Chernyshev and Golitsyn following the January 1756 signing of the Westminster Treaty by Great Britain and Prussia. Great Britain, which had been an ally of Russia for more than twenty years, thereby became its rival. Even in the period of armed conflict during the Napoleonic Wars, trade between Russia and Great Britain was maintained via so-called “licences”,41 but the threat of deliveries ceasing was very real.42 In 1791, in connection with the Ochakov Crisis during the Russo-Turkish War, the English side laid an embargo on the sale of equipment, and problems occurred putting into operation a machine for pumping water, for which the necessary parts were lacking.43

At the same time, of the two hundred astrolabes being made in the Academy of Sciences, only fifty were completed, while the remainder had only been started. The original resolution of the Senate meant the cessation of work on the unfinished devices, but in the Academy it was declared, that “the palm wood and oak, leather for the cases and other things have been bought and are already in a state of manufacture, and so it is impossible to leave the astrolabes unfinished, because otherwise the Treasury’s funds will have been spent in vain…”44 These manufacturers therefore denied the government the choice, insisting on the continuation of the work. Moreover, by this point, the price of one astrolabe had sunk by nearly a quarter: “the astrolabes being made at present at the Academy now cost thirty rubles and twenty-five kopeks apiece, including materials and labour, but that price is not final, rather it is only approximate or estimated by the manufacturers themselves, and the actual cost will become known only when all two hundred astrolabes have been completed […]”.45

When work on the General Land Survey began in 1765,46 the Main Surveying Chancery had about twelve hundred astrolabes in its toolroom. This was more than enough for carrying out surveying work and training future surveyors. Moreover, this supply played an important role in the development of their own manufacturing capability. Apart from the manufacture of astrolabes in the Academy of Sciences, active training of personnel for manufacture of high technology had begun and skilled foreign craftsmen had already arrived as teachers. Discussing the conditions for a new contract with the Academy of Arts in 1776, the Englishman Francis Morgan spoke of his six students, who, with varying degrees of skill, might make astrolabes, electrical machines, telescopes, microscopes, or other instruments.47 There was a growing preference for a native skills base. Among the responsibilities of the Chief Surveying Chancery was the recruitment of personnel for future surveys. As opposed to other areas of life, where fashion was dictated by foreigners (for example, medicine),48 the odds were at once in favour of Russian surveyors being chosen. By the end of the eighteenth century orders were being supplied by the workshop of the Academy of Sciences, headed by Ivan Petrovich Kulibin, and at the beginning of the nineteenth century the manufacture of geodesic equipment began in the Mechanical Institute of the General Staff under the direction of Kornelius Khristianovich Reissig.49 From the middle of the nineteenth century, orders for surveying equipment were placed exclusively with Russian producers.50 The reason was not protectionism, but that Russian firms were by then among the most advanced manufactures of surveying equipment. The leading producer was the Russian company Boelau (Gustav Boelau was a second generation Russian craftsman).51

As “the sole scale by which to create general maps from specialised maps”,52 a Russian-English hybrid was devised: one sazhen (seven feet) to an inch. It was invented by General Lieutenant William Fermor,53 the Russian-born son of an immigrant from England, together with Ober-Secretary Glebov in the role of senate advisor. Officially the sazhen was introduced in 1797 as the principal unit for measuring distances, on the insistence of Charles Gascoigne, the director of the state iron foundries in Petrozavodsk, in a statute about weights and measures, and it remained the main scale in use until the survey office ceased to function as a result of the Revolution of October 1917.54

Figure 6: Fragment of map of the town of Klin.55 An astrolabe with compass is visible, a measuring chain and also a scale rule in yards per inch of the type adopted by the General Land Survey.

The fates of the astrolabes that were imported to Russia were varied. The majority of them were kept in working order until 1765, the beginning of the survey under Catherine II. Until that time, the main reserve of instruments in the Senate consisted of 611 astrolabes, a quantity of measuring chains (in Moscow alone 500 were made), plus tools for technical drawing. Moreover, in the College of Estates (Votchinnaia kollegiia) there were 206 Russian and British astrolabes. The total of British and Russian tools in the Chief Surveying Chancery came to 1,087 items.56 A considerable number of these were perfectly serviceable until the end of the eighteenth century, when, on the one hand because of their age,57 and on the other, because of obsolescence (astrolabes with spyglasses had begun to appear), they went out of use. Most of the astrolabes perished during the occupation of Moscow by Napoleon’s troops. A barge, loaded with the possessions of the Survey Expedition, tried and failed to escape the city. Its cargo included 183 astrolabes, which were burnt and dispatched to the depths of the Moscow River.58

The results of boundary surveys carried out with the aid of Russian and British instruments transferred across to maps of state land allocations, which in their turn became the basis for maps of districts and provinces. The results of the surveying project were brought together for the first time in the Atlas of the Russian Empire in 1792. This atlas, while not free of inaccuracies and errors (especially in the Eastern part of the country, where there had not yet been a survey) became the basis for the much more complete atlas by V. P. Piadyshev that was issued from 1821. Piadyshev’s atlas, in turn, became a source for the ways in which, for much of the nineteenth century, the territory of Russia was conceptualised. Thus, the import and eventual domestic manufacture of the astrolabe led the Russian Empire to collect and process geographic information in a modern, scientific manner. This new-found knowledge both aligned the empire more closely with Europe and its cartographic technologies, and enabled Russia to see its own territory more clearly and accurately.

1 Translated by Elizabeth Harrison.

2 See, Anthony Cross, By the Banks of the Neva. Chapters from the Lives and Careers of the British in Eighteenth-Century Russia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997); Frantsuzy v nauchnoi i intellektual′noi zhizni Rossii XVIII–XX vv., ed. A. O. Chubarian, F.-D. Lishtenan (Moscow: OLMA Media Group, 2010).

3 See Leo Bagrow, History of Cartography, 2 vols, ed. by Henry W. Castner (Wolfe Island, ON: The Walker Press, 1975); V. F. Gnucheva, Geograficheskii departament Akademii nauk XVIII veka (Moscow: Izd-vo AN SSSR, 1946).

4 M. Iu. Anisimov, ‘Rossiia v sisteme mezhdunarodnykh otnoshenii v 1749–56 gg.’ (Kand. dissertation, Institut rossiiskoi istorii RAN, 2005); L. M. Grankov, ‘Morskoi torgovyi flot i vneshnetorgovaia politika Rossii, XVIII–pervaia polovina XX vv: istoricheskii aspekt issledovaniia’ (Kand. dissertation, Rossiiskaia ekonomicheskaia akademiia, 2009). With Great Britain: M. Iu. Rodzinskaia, ‘Russko-angliiskie otnosheniia v shestidesiatykh godakh XVIII v.’, in Trudy Moskovskogo gosudarstvennogo istoriko-arkhivnogo instituta, 21 (1965), pp. 241-69; Iu. S. Medvedev, ‘Russko-angliiskie otnosheniia v seredine XVIII veka (1748–63)’ (Kand. dissertation, Rossiiskii universitet druzhby narodov, 2004). With France: E. E. El′ts, ‘Franko-russkie kul′turnye sviazi vo vtoroi polovine XVIII v.’ (Kand. dissertation, Sankt-Peterburgskii gosudarstvennyi universitet, 2007). With the Netherlands: I. V. Kolosova, ‘Formirovanie i razvitie otnoshenii mezhdu Rossiiskoi imperiei i Niderlandami: XVIII–I polovina XIX v.’ (Kand. dissertation, Diplomaticheskaia akademiia MID Rossii, 2007).

5 The “astrolabes” in this chapter are surveying instruments, not planispheric astrolabes. This is consistent with Russian terminology (astroliabiia) from the eighteenth century onwards. We retain the terminology, although the relevant instruments might also be designated in English as circumferentors, or semi-circumferentors, or graphometers. See W. F. Ryan, ‘Some Observations on the History of the Astrolabe and of Two Russian Words: astroljabija and matka’, in Studies in Slavic Linguistics and Poetics in Honor of Boris O. Unbegaun (New York and London: New York University Press and University of London Press Ltd., 1968), pp. 155–61. The editors are grateful to Professor Ryan for his advice on the term.

6 See G. N. Teterin, Istoriia goedezii v Rossii (do 1917 g.) (Novosibirsk: NIIGAiK, 1992).

7 RGADA, coll. 1209, descr. 77, file 25186. For more detail about maps in the seventeenth century, see Valerie Kivelson, Cartographies of Tsardom. The Land and its Meanings in Seventeenth-Century Russia (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2006).

8 J.-N. Delisle, Explication de la carte des nouvelles découvertes au Nord de la Mer du Sud (Paris, 1752).

9 Letopis′ rossiiskoi Akademii Nauk (St Petersburg: Nauka, 2001), p. 406.

10 Ibid., p. 421.

11 T. V. Il′iushina, ‘Ot bussoli do astroliabii’, in Nauka v Rossii, 3 (2007), 97–101; V. S. Kusov, Izmerenie zemli: Istoriia geodezicheskikh instrumentov (Moscow: Dizain. Informatsiia. Kartographiia, 2009).

12 Rossiia i Gollandiia: Prostranstvo vzaimodeistviia, XVI–pervaia tret′ XIX veka (Moscow: Kuchkovo pole, 2013), p. 311.

13 Plan of the city of Tver with its villages, RGADA, coll. 1356, descr. 1, file 6057; Plan of the city of Vesegonsk with its villages, RGADA, coll. 1356, descr. 1, file 6027; Plan of Tver province, RGADA, coll. 1356, descr. 1, file 5949.

14 This is confirmed by the fact that on the plans and field notes, angles between two lines are fixed, as is the direction of the line in relation to the points of the compass.

15 Twenty-two rubles and forty-eight kopeks per astrolabe. RGADA, coll. 248, descr. 82, file 6740, fol. 1258 and 1258a; file 5949.

16 RGADA, coll. 248, descr. 82, file 6740, fol. 1264.

17 Map of Iaroslavl Province, RGADA, coll. 1356, descr. 1, file 6735.

18 RGADA, coll. 248, descr. 82, file 6740, fol. 1231.

19 RGADA, coll. 248, descr. 82, file 6740, fol. 1306.

20 RGADA, coll. 248, descr. 82, file 6740, fol. 1305.

21 Il′iushina, ‘Ot bussoli do astroliabii’, p. 101.

22 RGADA, coll. 248, descr. 82, file 6740, fol. 1268. See also: P. P. Papkovskii, Iz istorii geodezii, topografii i kartografii v Rossii (Moscow: Nauka, 1983); Kusov, Izmerenie zemli.

23 Artistes de la carte de la Renaissance au XXIe siècle (Paris: Autrement, 2012), p. 85.

24 RGADA, coll. 248, descr. 82, file 6740, fol. 1278. On July 20, 2,120 rubles were paid.

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 RGADA, coll. 248, descr. 82, file 6740, fol. 1278v.

28 RGADA, coll. 248, descr. 82, file 6741, fol. 22.

29 RGADA, coll. 248, descr. 82, file 6740, fol. 1308.

30 RGADA, coll. 248, descr. 82, file 6740, fol. 1308v.

31 The same policy was carried out from the reign of Peter I in relation to private apothecaries (in the beginning of the Petrine era medicines were without customs duties, then duties began to be paid through the Apothecary Chancery). See M. B. Mirskii, Ocherki istorii meditsiny v Rossii XVI–XVIII vv. (Vladikavkaz: Goskomizdat RSD-A, 1995), pp. 42, 64.

32 RGADA, coll. 248, descr. 82, file 6740, fol. 1306.

33 RGADA, coll. 248, descr. 82, file 6741, fol. 974.

34 RGADA, coll. 248, descr. 82, file 6741, fol. 974v.

35 RGADA, coll. 248, descr. 82, file 6741, fol. 1194v.

36 RGADA, coll. 248, descr. 82, file 6742, fol. 167.

37 Mirskii, Ocherki istorii meditsiny XVI–XVIII vv, p. 94.

38 Letopis′, p. 426.

39 In particular, N. N. Repin, ‘Vneshniaia torgovlia Rossii cherez Arkhangel′sk i Peterburg v 1700-nachale 60-kh gg XVIII v.’ (Dokt. dissertation, Institut istorii SSSR (Leningradskoe otdelenie), 1986), pp. 20–21.

40 RGADA, coll. 248, descr. 82, file 6742, fol. 167–8v. This report discusses a return of 642 rubles and 6 kopeks.

41 V. G. Sirotkin, ‘Kontinental′naia blokada i russkaia ekonomika (Obzor frantsuzskoi i sovetskoi literatury)’, in Voprosy voennoi istorii Rossii (Moscow: Nauka, 1969), pp. 54–77 (p. 65).

42 On the other hand, on 29 July 1756, in the company of the president, the English envoy W. Henbury visited the Academy (See Letopis′, p. 440.)

43 Cross, By the Banks of the Neva, p. 245.

44 RGADA, coll. 248, descr. 82, file 6741, fol. 1236v.

45 Ibid.

46 The General Land Survey was renewed by Catherine II in 1765 after re-thinking.

47 Cross, By the Banks of the Neva, p. 234

48 A. A. Golubinskii, ‘Stepan Khrulev: Sud′ba zemlemera’, in Rus′, Rossiia, Srednevekov′e i Novoe vremia, vypusk III, Tret′i chteniia pamiati akademika RAN L. V. Milova (Moscow: Orgkomitet Chtenii pamiati akademika RAN L. V. Milova, 2013), pp. 404–10.

49 P. P. Papkovskii, Iz istorii geodezii, topografii i kartografii v Rossii (Moscow: Nauka, 1983), pp. 11–12.

50 RGADA, coll. 1294, file 40218.

51 RGIA, coll. 1350, descr. 88, file 362, fol. 1–21.

52 RGADA, coll. 248, descr. 82, file 6741, fol. 80.

53 In the very beginning of its existence, during the reign of Elizaveta Petrovna, the Chief Surveying Chancery was headed by William Fermor. See Russkii Biographicheskii Slovar′, vol. 21 (St Petersburg: Tip. S. N. Skorokhodova, 1901), p. 53. In 1743–44 Fermor was appointed to conduct an audit and a census, and also to survey peasant lands in St Petersburg and Ingria.

54 Cross, By the Banks of the Neva, p. 237.

55 Plan of the city of Klin with its villages, RGADA, coll. 1356, descr. 1, file 2463.

56 G. N. Teterin, Istoriia geodezii v Rossii (do 1917 g.) (Novosibirsk: SGGA, 1992).

57 RGADA, coll. 1294, file 15335.

58 RGADA, coll. 1294, descr. 2. According to the index the file number is 27015, but the file itself has been destroyed.