4. How Was Western Europe Informed about Muscovy? The Razin Rebellion in Focus

© 2017 Ingrid Maier, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0122.04

The Cossack peasant rebellion under the leadership of Stepan Razin, with its culmination in the year 1670, was not only a major event in Muscovy; it was also an exceptional media sensation. West European newspapers printed the latest reports from the battlefront with great regularity, as well as rumours about the leader, Razin, and his plans and military alliances. When no news had arrived at the publisher’s desk, this very lack of information was considered to be worth mentioning, for instance with the remark “About Razin there is no news, beyond that he is neither dead nor captured”, found in a Dutch newspaper printed in Haarlem.2 One of the reasons for the unparalleled interest in all matters concerning the Razin uprising is the fact that the rebellion had a negative influence on trade, not only within Russia (or between Muscovy proper and the region of the Don Cossacks, beyond the “Don steppe frontier”3), but also between Muscovy and Western Europe. Merchants from Holland, England and Hamburg were discouraged from trading with Russia during the peak of the uprising, and thus there was a risk that trade between Russia and Western Europe would come to a standstill. The real culmination of the Razin rebellion, however, was reached several months earlier than the peak of the corresponding media hype in West European newspapers and pamphlets.

The reporting on the Razin rebellion is an excellent example to illustrate how news was collected in Moscow and transmitted to the West. The important research questions include: how did the publishers get the reports from Muscovy that ended up in their newspapers? Who were the authors, and how was the news transmitted to the West? The hypothesis is that there is some kind of connection between diplomatic correspondence and printed (or handwritten4) newspapers—a connection that has actually been demonstrated for a slightly earlier time period, viz. the early 1650s, when the Swedish resident in Moscow, Johan de Rodes, was sending regular reports to Queen Christina of Sweden, and the content of some of these letters could also be traced in printed Hamburg newspapers.5 Granted, we still do not know whether de Rodes himself had the necessary contacts with traders of news; possibly the letters to the Swedish heartland were copied somewhere en route (for instance, in Narva).

While my main focus here is on Swedish diplomatic correspondence, I will first review how Razin’s rebellion was mirrored in the periodical press of the time, focussing above all on German-language newspapers from Hamburg, with only occasional examples from papers issued in other languages or from other countries. The German newspapers, especially the ones from Hamburg, are of particular interest, since they contain more—and also more detailed—articles about the uprising than other papers (including the Latin newspaper from Cologne).

The Razin Rebellion as a Media Sensation

According to the German press historian Martin Welke, the Razin rebellion was one of the most frequently reported subjects in the German-language press of the years 1670–71: between September 1670 and August 1671, on average, there was news about this rebellion in every third or fourth newspaper issue available to him. He found a total of 180 items in that timespan that contained news about Razin. Another 40 items, dealing with the Muscovite government’s—usually successful—attempts to defeat the rebellion, after the execution of its leader had become known in the Western press, were found in papers printed between September 1671 and February 1672.6 The “media peak” thus started around the time when the actual uprising was more or less over: Razin had won his last military victories—at Saratov and Samara—in August 1670; in a decisive battle near Simbirsk the rebel was wounded and “disappeared from the scene until his final capture”, which took place on 14 April 1671.7 As noted already, the “culmination” of the rebellion in West European newspapers was “delayed”, in comparison with the historical facts. The earliest item published in A. G. Mankov’s chapter about “Reports from newspapers and chronicles” is datelined Moscow, 14 August [1670],8 an exceptionally long article about Razin’s seizure of Astrakhan and a discussion of the consequences for Moscow’s supply of fish, salt and horses from that region.9 The reason for this paradox cannot be explained exclusively by the transmission time; that is, it would normally take only about five to six weeks for news from Moscow to arrive at the newspaper publishers in Hamburg10 or Amsterdam (and some additional time for it to have reached the Russian capital in the first place), not several months. Another part of the explanation may lie in the fact that the “disappearance” of Razin from the battlefield constituted fertile ground for speculations, rumour and hearsay, much of which was published in Western news media. These news items often had very little in common with the actual events.

According to Welke, as many as twenty-one newspaper items had as their subject Razin’s execution;11 moreover, two German-language “execution pamphlets” are known (see below, especially note 40). A number of pamphlets about the rebellion (and, above all, about Razin’s execution in Moscow on 6 June 1671) also appeared in other countries: in Holland, in the Holy Roman Empire, in England, and finally in France.12 All known contemporary Razin-related pamphlets, and also a small portion of contemporary newspaper items, were republished during the Soviet era.13 Prior to these publications of printed sources from other countries, a multi-volume edition of Russian-language archival documents about the rebellion had been published by the Historical Institute of the Soviet Academy of Sciences, under the generic title “The peasant war under the leadership of Stepan Razin”.14

How Reliable was the Printed Razin News?

The newspaper publishers and printers (in the first century of the printed newspaper this was often the same person) faced a rather difficult task in choosing the news items that they found most interesting for their readership, and most trustworthy, from among the incoming commercial newsletters, or from previously printed papers.15 To determine the reliability of news was a constant challenge, and not only with regard to news from Russia: how could a publisher decide which of the reported stories might later prove to be true, and which would turn out to have been mere gossip and hearsay? One option was, of course, to wait for independent congruent information from other sources. However, in this case the scrupulous publisher would risk being scooped by another paper whose editor was not so careful about verification. News from Muscovy sometimes had to pass through many mouths (and pens) before ending up in a printed newspaper. If one person in this information chain, which stretched between a far-away eyewitness and the publisher (or, for that matter, the copyist of a manuscript paper), invented a few spicy details in order to make the news more interesting and therefore more “saleable”, the person at the end of the chain had no means whatsoever to detect this. The truth could be determined only in retrospect. The people who traded in news were very much aware of this problem, as can be shown on the basis of the following examples from printed newspaper articles, in which these difficulties are mentioned explicitly either by the author or by the editor.

In a news item from Hamburg, 17 February 1671, published in the Berlin-based newspaper Mittwochischer Mercurius and dealing mainly with the uncertainty of incoming information about a conflict in nearby Braunschweig (also situated in the Northern part of the German Empire), the Hamburg correspondent makes a most telling comparison: “To sum up: nobody knows what is the truth in this question. How could we ever, in such circumstances, have any trustworthy information from Moscow, situated some 400 miles away?”16 This journalist was clearly addressing the permanent uncertainty concerning news about the Razin rebellion, when numerous contradictory reports could be read in the press. The problem that no one could guarantee the truth of any specific news item describing the current state of affairs in far-away Muscovy was regularly addressed in the articles. According to Welke, thirty-nine of the news items studied by him (from the period up to the first reliable reports about Razin’s execution) explicitly talked about the fact that there was contradictory news, that a previously printed news item had proven to be wrong, or that the latest news had not yet been confirmed.17 In the example quoted above the problem had been addressed by the author of the news item, but we have evidence for the same kind of awareness among some newspaper publishers. Without any doubt the editor and publisher of the Hamburg-based paper Nordischer Mercurius, Georg Greflinger, took the lead in this race, constantly emphasising the uncertainty of all incoming news from Muscovy. Browsing the complete collections of the years 1670–7118 gives plenty of examples, such as the following news item, datelined “Nider-Elbe vom 9. May” (“Lower Elbe, 9 May” [1671]): “Letters from Moscow itself of 31 March Old Style do not mention any particular disturbances in connection with the rebels. They confirm that a leading member of Razin’s party was captured, his hands and feet were severed, and finally he was hanged. Other [letters] report something different. Time will be witness to everything”.19 All news items containing the place name “Nider-Elbe” were apparently put together in Hamburg, and we can make a qualified guess that the “Lower-Elbe” items printed in the Nordischer Mercurius were composed by Greflinger himself, generally using material from several incoming newsletters sent from different places.

News Directly from Moscow, and from “Passionate Places”

Comments by Greflinger in his Nordischer Mercurius suggest he considered news that was communicated in letters directly from Moscow to be more trustworthy than news composed in other places. The reason for this might be previous experience, for instance, that fewer post-factum corrections were needed for news that came directly from Moscow, compared with newsletters composed—less frequently—in Pskov or Novgorod, or beyond the Muscovite borders.

News items about the Razin rebellion composed in Moscow during the first six months of 1671 report, as a rule, that the situation was under control (which is more or less according to the historical facts), whereas ones that had been written in Riga, Stockholm, Vilna, Warsaw, Lemberg (today Lviv, Ukraine), Danzig etc.—that is, by authors from Sweden and Poland-Lithuania, Russia’s potential enemies—tended to present the Russian state as weakened by the rebellion and to exaggerate Razin’s successes up to the very day of his execution20 and even beyond that date. So, for instance, we have a Russian translation of a news item from Hamburg, 6 June 1671, stating that “Couriers report from Livonia and from Moscow that the traitor Razin is again gathering his forces and seizing cities”.21 Ironically, 6 June was actually the day of Razin’s execution in Moscow. Almost two months prior to this he had been captured near Kagalnik (a village situated eight kilometres from Azov) by Kornei Iakovlev, the ataman (Cossack leader) of the Don Host (who was loyal to the tsar).22 Another item, datelined Warsaw 31 January [1671] and also translated for the Muscovite government, is in a printed Dutch newspaper from The Hague: “The news from Muscovy reports that the rebellion there is still going on and that the colonel [i.e., Razin] and his followers have conquered not only Astrakhan and Kazan, but also about 50 other important places. Their troops are said to consist of about 200,000 men. An envoy from the Swedish crown is said to have arrived there with letters, in which he [Razin] calls himself the Tsar of Astrakhan, to treat with him. Allegedly the Persian [shah] also is interfering in this rebellion on account of differences [with Russia] over the Caspian Sea”.23 The numbers in this news item are heavily exaggerated, and it is exactly the kind of report about which the publisher of Nordischer Mercurius, Greflinger, would have commented with the explanation that it had come from a “passionate place” (that is, the news is biased). Why such patently ridiculous articles were translated for the kuranty when the tsar, of course, had much better, more up-to-date, and more reliable sources about the current situation, has already been discussed in another article.24 It is well known that the Muscovite government was interested in foreign reporting about Muscovy, especially if it was false and could be protested. The tsar’s colonel, Nicolaus von Staden, wrote from Novgorod on 24 September (probably 1672) to a representative of the Swedish crown:25 “[…] Regarding the protest, which his Tsarish majesty has directed to the Swedish crown in connection with printed newspapers: it can be answered truly—as Count Tott also said in his answer to me—that neither in Sweden, nor in Riga, nor in any other territory belonging to his Royal Majesty [of Sweden] are any newspapers in German being printed. It is impossible to protect oneself from such deceitful people [falsche leute], who write down such lies and hardly control them, God forgive them. The old Marselis,26 who receives the newspapers, and always immediately makes translations of news from Sweden directed against Moscow, has only caused problems because of that”.

We find the very first authentic (post-factum) information about Razin’s capture in a news item from Hamburg (“Nider-Elbe”) dated 20 June, in which the editor (Greflinger) refers to newsletters directly from Moscow: “Letters of 16 May Old Style from Moscow itself confirm that the rebel Razin has been captured, and that he is being brought to the tsar very slowly. However, there are still no details about the manner in which he was captured and taken from his army. Some [letters] add that all lost cities, except Astrakhan, are again in the possession of the tsar”.27 The first sentence may well be based upon a dispatch from Moscow sent to governor Simon Grundel-Helmfelt in Narva from the same date, quoted below (see p. 138).

The newspapers occasionally referred explicitly to the fact that a news item’s reliability might depend on its place of origin. Several authors, as well as the publisher Greflinger, speak about “passionate places” (“passionierte Orte”), which should be understood as “partial, biased, one-sided” in this context. Examples are an item from Danzig, dated 7 April 1671: “Some [authors] talk again about the rebel Razin’s big successes, although this news for the most parts originates from ‘passionate’ places”,28 or another, datelined “Nider-Elbe vom 9. April” (that is, most certainly containing Greflinger’s own voice): “There is news via Danzig saying that [those of] the Don Cossacks, whom Moscow is trying to win for money, are now on the side of the main rebel, Stepan Razin. However, some [people] think this is biased news” [“vor eine passionierte Zeitung gehalten wird”].29

Many strongly biased news reports from “passionate places” can be found in the Cologne-based Latin newspaper Ordinariæ Relationes. For example, the following item from Lemberg (Lviv):

Lemberg, 27 March. […] From Muscovy we have learned that the rebellion is growing stronger and uglier from day to day, and that the rebels threaten to kill the Muscovite Grand Prince. Peasants and [people] belonging to the lowest layer of men flee in growing numbers to the army of the rebel Stepan Razin [Stephani Raninii] because they see that the Muscovite Prince is inferior in the defensive struggle, and that they will be living more safely under Stepan’s leadership than under the rule of the [Grand] Prince.30

Most suspicious of all, at least in Greflinger’s opinion, seemed to be those newsletters about the rebellion which were sent from Riga. International mail from Moscow was usually sent via the Riga postal line, which had been established in 1665; Riga was thus an important transfer point for news out of Moscow. When the Moscow news arrived in Riga, it was usually “completed” with information from other places—and probably with a great deal of hearsay. Greflinger summarises the difference between Moscow news and Riga news in an item from “Nider-Elbe” (Hamburg), dated 3 February: “Letters from Muscovy dated 24 December report that everything is calm, whereas Livonian letters say it is all bad”.31 That much faked news was sent out from Riga can be explained in part by a conscious disinformation campaign carried out by the tsar’s Riga-born colonel, Nicolaus von Staden, in the spring of 1671. A news item from Riga, dated 6 March 1671, reports his arrival and then continues: “Moreover we hear from this envoy’s people that the well-known rebel Stepan Razin has been completely defeated. 20,000 of his former followers were hanged, the same amount captured and killed by sword, and about 50,000 have been drowned”.32 This news was biased, and the numbers of people killed are heavily exaggerated. This can be compared with earlier information from “passionate places”, according to which Razin had assembled an army of 100,000 men. It may well be that Nicolaus von Staden’s “disinformation campaign”, conducted while he was in Riga in the spring of 1671 (undoubtedly on the tsar’s orders), was one of the reasons why Moscow news “made in Riga” was not very trustworthy. Ironically, von Staden was also on the payroll of the Swedish state, although probably this began some months later.33

Greflinger usually published corrections and modifications of news printed during the previous month on the verso of the title page at the beginning of the new month. During January 1671, in his “Correctio Nicht erfolgender Sachen im Decembri 1670” (“Correction of News from December 1670 that Could Not be Confirmed”), he writes: “The Muscovite news items are still very uncertain, therefore their correction will have to wait until the next month”. Most telling is a news item from the Hamburg region, “Nider-Elbe vom 17. Febr”., two thirds of which deals with the situation in Russia:

The news about the events in Muscovy varies so much that one is almost afraid of reporting anything […] Letters of 11 January Old Style from the city of Moscow itself report that nothing was known there about any rebellion, and the tsar is planning to marry again, within six weeks. Other [letters] of 5 January from the same city, that have arrived in Danzig, say that a lot of news is coming from the Muscovite army, but there is no reliable information. Older letters of the last of December 1670 inform that the rebel has been repulsed to such a degree that a hundred miles are paved with poor killed people, former soldiers of the rebel’s army. Letters from Riga of 31 January New Style mention that no news had come in from Moscow these last days, and they therefore still do not presume anything positive. Everybody is invited to believe whatever he wants about all this […].34

Contradictory news from Muscovy arrived throughout the whole first half of the year 1671 and was published, very often with a comment by Greflinger saying that the reader could not be certain of anything. The situation changed only in the second half of 1671, from mid-July, when the first reliable news about the execution had arrived in Hamburg. However, at first the publisher of the Nordischer Mercurius remains somewhat cautious, as we read in a news item datelined “Nider-Elbe vom 11. Juli”: “We now have so many newsletters from Moscow [stating] that the rebel Razin has been seized, that one can no longer have any doubts about it, although the letters are still controversial. See some of them here [below]”.35 This announcement is followed by three news items, the first one from Pleskau (today Pskov) dated 20 May: “The Don Cossacks who have remained on the side of Moscow have captured the rebel with a special trick. He is being brought to the emperor [Käyser] to get his reward”. The second is datelined “Novigrodt” (Novgorod), 29 May. It describes a great fire in Moscow and another in Tver. About Razin we read: “The rebel has been brought to Moscow as a captive. This, however, does not mean that the uprising has come to an end: they believe that there will be more disturbances”. Finally, the most recent—and therefore most updated—news item (from Moscow, dated 8 June) reads: “On the third of this month the rebel was brought here, and on the sixth he was thrown to the dogs, very mutilated. More details will follow as soon as possible”.36 The only minor mistake in this Moscow news item, when it comes to historical facts, is the date when Razin was brought to the capital: this happened on 2 June, not on the 3rd.37 But generally the information is correct—for instance, the date of the execution was indeed 6 June. The news item from Pskov is also absolutely correct, and the one from Novgorod contains only one minor mistake: on 29 May, Razin had not yet been brought to Moscow, for on that date he was still on his way. The newsletter from Moscow dated 8 June had made its way to Hamburg very quickly, within around thirty-four days, since Greflinger could publish it around 12 July,38 and 10–11 July was apparently the time when the first information about Razin’s execution had reached Hamburg (both Moscow and Hamburg used the Julian calendar). Incidentally, in this specific case we can be quite sure that the printing date was 12 July, because the obligatory weather observations at the end of the issue cover the period between 8 and 11 July,39 and generally we can presume that the printing day would have been one day after the issue’s “Lower-Elbe” item. On the basis of Greflinger’s “More details will follow as soon as possible”, we can extrapolate that he already had these details on 11 July. However, he could not insert a detailed description of what had happened in Moscow on 6 June into the current issue, which was already filled with all kinds of other news, the major portion of which most probably had already been typeset when the Moscow news came in. All he could do was insert that very short “post-execution” message. Immediately after the weather observations is another notification, an advertisement: “Hierbey wird etwas sonderliches verkaufft” (“In connection with this, an additional separate [publication] is being sold”). Although this phrase does not say explicitly that this “additional separate publication” was to cover Razin’s execution, it seems likely that this was the intent.

A Printed German-Language Report About the Execution

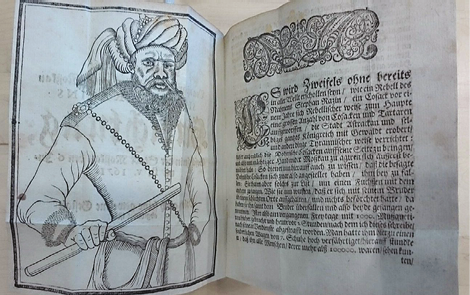

Two anonymous German-language quarto pamphlets about Razin’s execution are known, one of them containing a (very unrealistic) “portrait” of the rebel.40

Figure 1. An (invented) portrait of a turbaned Razin with a marshal’s baton in his right hand from a German-language pamphlet.41

According to Mankov, this pamphlet probably was an appendix (prilozhenie) to the Nordischer Mercurius,42 whereas Welke thinks that the “Razin issue” belongs to another Hamburg-based paper, Wöchentliche Zeitung auß mehrerley örther.43 In my estimation, it was not an appendix at all, but just a separate pamphlet. One additional textually identical version was published in an ordinary number of Europæische Montags Zeitung (issued in Hanover44), under the headline “Moßkau den 20. Junij/ styl. nov.” There are minor differences in spelling and punctuation between all three versions. Mankov reprints the text.45 Partially different versions (although some fragments always overlap with the “original” version, from 1671) were reprinted in later years, in chronicle books and historical encyclopedias such as Diarium Europæum (in German) or Hollandtsche Mercurius (in Dutch).46 Could it be that both scholars are right, and two Hamburg publishers issued one supplement each? In this case one might presume that the edition with the portrait was issued by Greflinger, the publisher of Nordischer Mercurius, because there is an advertisement on the last page of a February issue reading “In connection with this [hierbey] the portrait of Stepan Razin, the main rebel against Moscow, is being sold”47—which means that Greflinger actually was in possession of the “portrait” (an invented portrait, imitating a copper engraving from the workshop of the late Paulus Fürst, Nuremberg; see note 41).

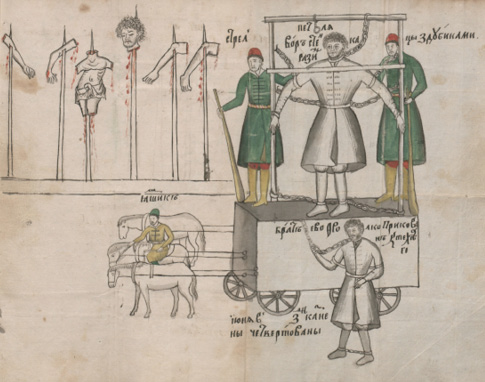

Although it seems impossible to prove whether one of the pamphlets was connected to Nordischer Mercurius in some way, at least one more note about the execution was printed in an ordinary issue of that newspaper. Under the headline “Nider-Elbe vom 1. Augusti” we read: “How the rebel Razin was executed has been drawn by hand in Moscow, and the description about it is in Greek letters. Arms and legs are on poles, and the head and the trunk, too, whereas the intestines have been thrown to the dogs”.48 This note apparently describes the colour drawing from Moscow (see Figure 2); either the author of this note (probably Greflinger himself) or somebody else must have seen a version of the drawing, not only heard about its existence, since the body parts that had been set up on poles correspond to the drawing, not to the actual facts: in all eyewitness reports about the execution only five body parts (arms, legs, and head) had been set up, whereas the trunk had been left on the ground for the dogs. We will return to this question below.

Razin’s Rebellion in Swedish Diplomatic Correspondence

Let us now return to the research question formulated in the introduction to this chapter: who were the authors of the Muscovite items in the West European newspapers, and how was the news transmitted to the West? It has already been mentioned that Johan de Rodes, the Swedish commercial agent in Moscow in the first half of the 1650s, may have been the purveyor of news that ended up in printed German newspapers, so one hypothesis is that the situation was still just about the same in the early 1670s. During the period in which many Western newspapers quite regularly printed news about the Razin rebellion, another Swedish citizen, Christoff Koch—actually Johan de Rodes’s brother-in-law—was sending regular reports to the governor general of Swedish Ingria in Narva, Simon Grundel-Helmfelt (1617–77).49 Although I have not yet found any longer verbatim passages in that “Swedish correspondent’s” letters and in German-language newspapers, it seems very likely that some of the printed information about Razin had originally been assembled by Koch. He was born in Reval in 1637 to German-speaking parents50 and there are no indications that he knew much Swedish; all his letters, which have been preserved primarily in the Swedish State Archives in Stockholm, are written in German. Koch came to Moscow in 1655 aged eighteen, together with his brother-in-law Johan de Rodes, and stayed there for most of his life. He must have earned his living in Moscow first and foremost as a merchant, but he also received both money and recognition in Sweden for sending regular reports to Swedish court officials. His early letters sent to Helmfelt, from the 1670s, are always anonymous, but since a lot of later letters have also been preserved, signed by him personally (although usually not written by his own hand), we can be fairly sure that the earlier, unsigned communications were also written by him. A strong argument for this assumption is Koch’s particular use of German (for instance, the frequent appearance of Low German words, and Low German influences on his grammar and spelling); another is that no other regular “correspondent” from Moscow at the time is known. Moreover, the governor, Helmfelt, to whom the letters were sent, often mentions “my correspondent” or “the usual correspondent in Moscow”, and sometimes he even mentions Koch by name (in the Swedish form, Kock).

One of Helmfelt’s tasks was to send regular reports to the Swedish government about everything that was happening in Muscovy. His reports were officially addressed to King Charles XI, who had not yet attained his majority. Together with his own letters Helmfelt would also send attachments. Most of the attachments preserved in the archives are reports written by Koch, but Koch would also send other materials to Narva—for instance, official Muscovite documents, such as a peace treaty. He seems to have written to Helmfelt once a week, and apparently Helmfelt also wrote one letter every week to the king. Of course, many of these letters, and possibly even more of the attachments, are now lost.

Helmfelt received such correspondence not only from Moscow, but also from Novgorod and Pskov, although more rarely. If nothing had been received from any of these places he would mention this too, for instance with the words “no news has come in from the neighbourhood”51—Narva was very close to the Muscovite border—and he would still report about the state of affairs in Muscovy in a sentence or two. The governor’s letters are usually very short, in some cases because he had not received any reports. On other occasions he would offer a brief summary and mention that more details could be read in the attachment(s). Presumably Helmfelt normally did not forward the originals received from Moscow (written by Koch’s secretary), but had his own secretary make copies. However, some of the communications that were forwarded to Stockholm from Narva may well have been the originals from Moscow.

The Moscow correspondence from the relevant timespan can be found in three modern archival files at the Swedish State Archives in Stockholm: Livonica II, vol. 179, containing Helmfelt’s letters (usually with attachments) to his king from the years 1668–70; vol. 180, comprising the years 1671–73; and the Bengt Horn collection, E4304, with letters—and attachments—from Helmfelt to Bengt Horn, the governor of Estonia from 1656. Interestingly enough (although not very surprisingly), several “Moscow attachments” in the “Livonica files” and in the Horn collection not only contain exactly the same reports, but are also written by the same hand; in these cases we can be sure that both copies were made by Helmfelt’s secretary, because the Moscow correspondent would not have sent two copies of the same letter to Narva.

The first letter to the Swedish king in which Helmfelt mentions the rebellion of Stepan Razin is dated Narva, 14 July 1670.52 In addition, the attachments from Novgorod and Moscow also contain “Razin news”.53 In the following archival file, vol. 180, probably all the Moscow attachments had been sent to Narva by Christoff Koch. The oldest report from Moscow in this file is the “Extract schreiben auß Muscou d. 13. Xbris 670” (“Summary letter from Moscow, 13 December 1670”).54 It was sent from Narva to Stockholm together with an accompanying letter of 5 January 1671 addressed to the king and signed by Helmfelt. About two-thirds of the “Extract” deal with Razin: “From Astrakhan we do not have any other news, beyond that it is still occupied by Razin’s army. He has sent the harvest of this year, such as wine, melons, and other fruit, to his majesty [the tsar], that is, he has sent everything to Simbirsk, and the voevoda [military commander] has dispatched [a courier] to his majesty, asking whether he would like him to forward the merchandise to Moscow. Thereupon they consulted the patriarch, whose recommendation was to pour the wine into the Volga river, because Stenka could have poisoned it […]”. The letter is quite typical for Koch’s correspondence: many details are given, not only about Razin, but also—towards the end—about the new customs system which the Muscovite government was about to introduce. First and foremost, Koch was a merchant who would have been attentive to such details. The report also contains some typical examples of “Koch syntax”, such as “von Stenca Raisins seinem Volcke […] besetzet”.55 Also included is a report from Novgorod (thus not written by Koch; we can only make a qualified guess that the Novgorod item was composed by the Swedish commercial representative to Novgorod), which is dated 25 December. Presumably, the Novgorod author also had other sources, since he underlines the uncertainty of the situation: “[…] About Razin different news has been received, so that nothing certain can be communicated. Some think that he is in Astrakhan, others that he is in Simbirsk, and although a letter which arrived here on 21 December tries to make the common populace believe that he has been wounded, this was only a rumour, because we were informed for sure by a secretary from the Chancery [auß der Pricase] that he is still healthy and is encamped near Simbirsk […]”. As we see, this Novgorod item contains exactly the same type of contradictory news as we could read in the newspaper items presented above.

In the next letter to the Swedish king, dated 12 January 1671, Helmfelt mentions an attachment, “which is a letter sent by the tsar to the voivods in Novgorod [Naugorodt] and Pskov [Plesco], in which the tsar himself reports in great detail what has happened since 1668, when this unrest started, until 6 December 1670, the date of the letter”. A letter to the military commander of Novgorod, M. Morozov, is published in Krest′ianskaia voina.56 It does not have an exact date on it, as only the month is indicated (November). The ending of this letter to Morozov gives some insight into how its contents might have become known to the Swedes and other foreigners: “When you have received our great ruler’s letter [gramota], you should order it to be read aloud more than once to the inhabitants of Great Novgorod, whatever rank they might be, in the administrative office [office of the provincial voevoda-prikaznaia izba], so that they will get word about the victory, won by our great ruler’s soldiers, over the rebel, apostate and traitor Stenka Razin and his allies”.57 This is a very interesting example of the way the government wanted to get its version of the news out, presumably in the first instance for internal Muscovite consumption, but possibly also with foreign merchants and others in mind as a second target group.

Helmfelt continues his short summary of the tsar’s gramota with the words “At the end he [the tsar] mentions that their Razin [Raisin] is wounded and had to retreat.58 The tsar orders that this letter be publicly read in the pricasse, or Chancery [Cantzleystube] […]”. There cannot be any doubt that both the commander of Novgorod and Helmfelt received essentially the same document. What we do not know is who sent or handed over the document to Helmfelt. Presumably the tsar’s letter was first sent (or given) to Helmfelt in Russian, and most probably Helmfelt forwarded the original Russian text to Stockholm, although we cannot exclude the possibility that the translation was made in Novgorod or in Narva, and Helmfelt received a Swedish translation. Since the handwriting of the Swedish version is the same as in many other translations from Russian that are preserved in the Swedish archives, it is more logical to presume that it was made by one of the translators for the Swedish crown in Stockholm. In the archival box there is no Russian version, only a Swedish one. Another attachment forwarded to the king by Helmfelt on the same occasion is the full twenty-eight-page text of the 1667 treaty of Andrusovo between Muscovy and Poland. The letter and the attachments were apparently sewn together in Stockholm; today, some folios have become loosened from the rest. In this way the official view of the Muscovite government might have found its way into a printed newspaper, via people like Koch and Helmfelt.

An example for which we only have the Russian translation in the kuranty is a Moscow item of 26 January 1671 from a Dutch newspaper: “Here there are letters from the regiments of his Majesty the Tsar which write how the bandit Stenka Razin has arrived at the city of Simbirsk with 20,000 men. And from 4 September through 3 October they launched 15 terrible assaults on the city. […]”.59 The reader is told about the boldness of General Ivan Miloslavskii and about the joining of forces with Prince Iurii Bariatinskii, who had arrived from Kazan. The newspaper article also tells us that the tsar promoted Miloslavskii to a high rank for this victory. We read about Razin being wounded and that he “barely escaped in a boat, and only a few people escaped with him.60 Five hundred people were taken alive and executed on the spot […] And this disorder has now completely ended, and the merchants can once again set out for this state”.61 The last sentence confirms that it was very important for the tsar to communicate to merchants in Western Europe that it was now safe again to take up trade with Muscovy. On 26 January 1671, three to four months had passed since the deciding battles, and such a “news” item would only make sense in the context of a summarising official statement, of the same type as the communiqué dated 6 December discussed above. I could not find such a summary in the published Russian documents, although there are plenty of reports about military action, which were sent separately as events were occurring. My hypothesis is that the government had made a compilation at the beginning of December 1670, and this compilation was either handed over to some foreigner or it leaked out. Eventually a version of this compilation was published in The Hague, and it came back to Moscow in a news summary, as a news item in the kuranty.

In his letter of 3 March 1671 Helmfelt informs the king that the tsar’s colonel, Nicolaus von Staden, is on his way to Riga, via Novgorod, and he also mentions two attachments about Razin, which were marked with the letters “A” and “B” respectively. About attachment “B” Helmfelt writes: “I am sending to Your Majesty, under letter B, what has been made public by the Russian side in the form of a report about the recent course of events concerning Stenka Razin [Stencka Raisin]”. Unfortunately, only the missive marked with the letter “A” is in the document box; the other attachment might have been filed somewhere else in the archive, or it might be lost altogether. But it is very clear from Helmfelt’s letter that the tsar actively spread his communications to the foreigner Koch in Moscow, who forwarded them to Helmfelt in Narva. The most likely person to have contacted Koch was Artamon Sergeevich Matveev, the man who was to become the new head of the Ambassadorial Chancery, after Afanasii Ordin-Nashchokin had been removed in 1671.62 There are several letters from Moscow, mostly from the following year, 1672, in which Koch writes that he had been invited to take a meal with A. S. Matveev.63 Yet as early as 21 March 1671 Koch sent Helmfelt a very positive assessment of Matveev, and it is also clear from this and several other letters that Koch visited the Chancery quite regularly: “He [Matveev] is intelligent [gutes Verstandes], he makes quick decisions, and he helps the rich and the poor to obtain justice. […] Yesterday I saw him making more than thirty decisions [Urteil] within five hours. I have never experienced anything similar before. Probably he will climb high here”.

In a letter from Narva of 15 March, Helmfelt reports that “the news, according to which Stenka Razin had been brought to Moscow in chains, has not been confirmed”—the Russian side had spread this rumour prematurely, when it was already quite clear that the rebel would soon be seized.64 In the same letter Helmfelt also informs the king that “Artaman Sergeevich [Sergeiewitz] has been installed at the Ambassadorial Chancery [Posolski pricas] instead of Nashchokin, because the latter has to go to Poland as an envoy”. Incidentally, the news about Nashchokin going to Poland was also premature, because, in his correspondence of 21 March, Koch writes that Ivan Ivanovich Chaadaev, Dementii Minich Bashmakov, and a secretary are going to Poland as envoys, instead of Nashchokin.

In his letter of 19 April to the king Helmfelt gives a short summary of the included attachment, a report from Moscow dated 4 April, in which Koch writes: “They say, concerning the rebel Razin [Raisin], that he has been in Saratov not long ago and that he has substantial forces. They also say secretly [auch wird heimlich geredet] that he is planning to hand over Astrakhan to the Turks”. Helmfelt’s next letter to the king, dated 8 May, contains an attachment from Moscow with Razin news (as usual, among many other subjects), dated 11 April: “The rebel is said to have united his forces with the Calmucks, the Bashkirians, and the cossacks from Zaporozh′e, and he is on his way to Simbirsk with powerful forces. Borotinskoi has been sent to Simbirsk with his forces, and Petr Vasilevich Sheremetev [Peter Wasilowitz Scheremetoff] has received orders to go to the Don with his army”. The confusing information is probably based on the equally confused state of the Russian authorities (cf. note 64). Koch makes it quite clear that this news has not been confirmed; he is reporting the rumours that were circulating in Moscow.

After Helmfelt’s letter of 8 May there is a gap in the archival file. His next letter to the Swedish king is from 1 June. In the archive, this letter is filed together with attachments from Moscow of 16, 23, and 30 May.65 Helmfelt comments on his long silence by observing that there were several posts that did not contain any news about Muscovy, or, if they did, the news they contained was not worth mentioning. However, in another archival file,66 containing Helmfelt’s reports to the governor of Estonia in Reval, Bengt Horn, there is a letter from the following day, 2 June, with a Moscow attachment of 9 May. This is the earliest “Koch report”, in which we read about the seizure of Razin by the Cossack Kornei Iakovlev. However, Koch is still a bit skeptical: “Last Thursday a messenger arrived from the Don Cossacks, reporting that the rebel Razin was captured by a Don ataman, called Corneli Jacoblef, and he is said to be brought here as soon as possible. On the following Friday this news was confirmed by two written communications [2. posten] and spread among the most noble as well as the common people. Time will show, whether the same thing as happened lately will be repeated again”. The recent event was undoubtedly the occasion on which a previous report about Razin’s capture had to be disclaimed later on.

In his letter of 16 May67 Koch confirms once more that Razin had been seized; among other things, he writes: “Not only several letters [etzliche Posten], but also fourteen Don Cossacks, who had been sent to Moscow five days ago especially for this reason, confirmed that an old ataman of the Don Host, whose name is Corneli Jacofloff, has actually captured the rebel, and he will soon be brought here [i.e., to Moscow]”.68 The next Koch report, of 23 May, confirms this fact once more: “It was confirmed that Razin really has been seized. Count Grigori Grigoriewitz Romodannofskoj has sent some troops to meet up with them, so that those [Cossacks], who are with him, can advance safely”. In his letter of 30 May Koch communicates that the rebel and his brother will be delivered to Moscow “this coming Friday”, which also would prove to be correct: Koch usually wrote his letters on Tuesdays; the next Friday after Tuesday, 30 May, was in fact 2 June, the day on which Stepan and Frol Razin were brought publicly to Moscow, a scene very well known from several descriptions.

Stepan Razin’s execution: a previously unknown illustrated description

Towards the end of June, Helmfelt sent two letters to the king, this time from Nyen (not from Narva, as usual), one on 24 and one on 30 June. The latter is very important for our purpose. Here Helmfelt mentions that the rebel Razin is dead, and that all details can be read and seen in the attached “relations and drawing”. Indeed, there are two “relations” in the Stockholm archives, in other words, two of Koch’s reports, written 6 and 13 June respectively, both with the headline “Extract Schreibens auß Musco” and the date, and one coloured drawing. The drawing must have been made in Moscow, probably at the initiative of A. S. Matveev, the head of the tsar’s Ambassadorial Chancery, as proof that the rebellion was over. In the archive, the three attachments are sewn together with Helmfelt’s letter.69

Figure 2. Coloured drawing of Razin’s execution (originally from Moscow), 1671.

The drawing shows two separate scenes: in the right half we see Stepan Razin on a cart and his brother Frol chained to the cart, four days before the execution, when the two brothers were brought to Moscow. (On the day of the execution the same cart was apparently used again.) In the left half, above the horses with the carter (iamshchik), Stepan’s body parts are shown, set up on poles: arms, legs, trunk, and head. The first scene (on the right) is apparently presented in a realistic way and must have been produced by someone who had seen how the two Razin brothers were delivered to Moscow on 2 June. Many people had seen this event, and an artist from a Muscovite chancery must have produced an illustration (or rather several copies, since they seem to have ended up in at least three countries; see below).

The drawing was made by an artist who was not familiar with Western perspective: the perspective of the cart is not shown correctly, and all persons are shown from the front. Of course, it is also possible that the drawing was consciously done with iconographic inverted perspective, and we cannot exclude the scenario that it was produced in the first instance for a Muscovite, not a Western, audience, even if copies were then sent to the West. Moreover, the manner in which the cart is attached to the horses is technically impossible. Nonetheless, this is an extremely interesting piece of evidence, since not a single other portrait of Razin drawn from life exists.70 We had supposed that portraits printed in other countries were all based on pure imagination. However, it now appears that the portrait on the folding plate printed in London in 167271 was modelled on this eyewitness drawing, so the London portrait, too, is based on reality, albeit at second hand.

Figure 3. Folding plate, printed in London (1672).72

The engraving is a mirror image of the prototype from Moscow, the logical result of an engraving copied from an original and then reversed when printed. The engraver of the folding plate apparently tried to adjust the Muscovite original so that it was presented in something closer to Western artistic language. Although the perspective of the cart is quite odd even here, the human figures are shown from different angles (front, profile, back), and the horses—or rather donkeys, or mules—are attached to the cart in a realistic way. The artist’s intention was certainly not to make an exact copy of the Moscow drawing, indeed there are additional differences between the images. For instance, on the engraving Razin’s brother wears a cap; the carter is not sitting on one of the horses, but standing next to them, and the musketeers hold halberds, not clubs, in their hands. The “post-execution scene”, with the skewered body parts, is missing altogether on the London folding plate. But all in all there are so many similarities between the two pictures that we can safely exclude the possibility that the engraving could have been made without access to a copy of the drawing from Moscow. Of course, the drawing that was sent to England would not necessarily have been identical to the one kept in the Swedish archives; it is possible that some of the differences in the London image, relative to that in the Swedish archives, might have resulted from the production of multiple copies (for instance, perhaps the version used for the London illustration did not include the impaled body parts at all).

In any event, the London engraving is proof that drawings—as “hard-copy evidence” for Razin’s execution—were given to several persons in Moscow: beyond the original drawing preserved in Sweden we have indirect indications that a version ended up in England (the London engraving), and one copy must also have been delivered to Hamburg, since what was described in the small article in Nordischer Mercurius—“drawn by hand in Moscow”, with a description in Greek letters (actually Cyrillic), is nothing other than the colour drawing made in Moscow (see the full quotation above, p. 129).

The scene with the cart and the two brothers corresponds very well to the eyewitness reports about how the rebels were brought to the city. In several descriptions the construction to which Stepan is fastened with chains is called “a gallows”.73 This is shown by the (tiny) loop on the upper horizontal wooden beam and the word “petlia” (“loop”). The musketeers are shown with clubs in their hands—not with halberds, as they are shown on other Muscovite pictures and on the London engraving. The Russian text also says explicitly “strel′tsy z dubinami” (“musketeers with clubs”). Under the loop we can see the words “vor Stenka Razin” (“the rebel S. R.”), and on the left side of the cart, next to the portrait of Frol Razin, “brat evo Frolko prikovan k telege” (“his brother Frolko, attached to the cart”). At the bottom we are informed—erroneously—that both persons were executed and quartered on 7 June (“kazneny chetvertovany iiunia v 7 den′”).

A striking detail about this unique historical document is that it must have been produced before the execution had actually taken place. There is no absolute proof, but we have three indications for this statement. First, the date of the execution is not correct: the text on the drawing says 7 June, instead of 6 June. (There seems to have been some confusion regarding the exact day and manner of the execution; see below.) Moreover, the text wrongly states that both rebels had been executed and quartered, although Frol’s life was to be spared for another five years,74 and finally, Razin’s trunk is among the impaled body parts, whereas all our descriptions agree upon the fact that the trunk had been left on the ground.

Koch’s “relation” dated 6 June is a very detailed—and hitherto unknown—description of Razin’s execution. It comprises five pages, of which I will provide but a summary here. First Koch describes how the two rebels were “taken in miserably last Friday, that is, on the 2nd of this month, here into Moscow, through the Tver Gates, and brought to the Land Court75 in the Red Wall. The cart had four tall wheels, and it had a platform on top”. The description corresponds so well to the drawing that one may wonder whether Koch was describing the scene from his own memory, or, instead, from the drawing he had in front of him. He also mentions the “gallows”:

In the middle on that cart there was a gallows, about one span taller than himself; in this the poor hero Razin [Raisin] was fastened with iron chains. He was hanging in it like a fly in a spiderweb. First of all, his head was fastened on that same gallows with a chain; he was also fastened at both shoulders, at his arms, and on both posts of the gallows, with handcuffs on both hands that were forged to the posts of the gallows. The middle part of his body was also fastened with chains, and last but not least, below, both his legs were fastened on both sides of the posts, with chains. In front of his chest there was a horizontal wooden pole, onto which he could sometimes lean forward. Thus he had to make his entrance on such a Triumphal Chariot, standing, fastened to a gallows, as described above. His brother was fastened on the left side of the cart with a long chain. His legs were also bound together quite closely.

So far everything is exactly as in the drawing. According to the written text, four musketeers were standing on the cart, one in each corner, whereas the drawing shows only two of them; similarly, on the three horses “three unhandsome boys were sitting in torn clothes”, whereas there is only one horseman in the drawing. The written text mentions that musketeers were riding on horses in front of the cart, as well as the Cossack ataman Kornei Iakovlev with five of his closest men, followed by another eighty Cossacks. Koch characterizes Razin as quite a tall person with large shoulders, light brown curly dense hair, covering half of his ears, and a “short, roundish dense beard”. His face looks strong and bold (frech); he appears to be in his mid to late thirties. His brother’s appearance is quite similar, his age about 26 years. Koch also describes the first torture session of 2 June; since he cannot have been an eyewitness to the torture, his report does not contain anything new on this subject. Then, however, we get some interesting and hitherto partially unknown information: on Saturday 3 June, two blocks—one each for the execution of the two brothers—were set up on Red Square, as well as five sharpened poles for each of them, for their heads, legs, and arms. At ten o’clock the execution was to take place, and the foreigners had been assigned a special spot from which they could see everything. However, the execution was delayed, because the two brothers were to be tortured once more. Apparently, no new date for the execution was given immediately, which might explain why the author of the drawing indicated the wrong date. Finally, “today” (6 June), at twelve o’clock, the Razin brothers were brought to Red Square, where Razin’s “wicked deed” and the verdict were read aloud; the public reading took about half an hour.76 “I will try to get this [text] and send it over”, Koch writes further down in this same report. Upon the command given by the “Chancellor Larrivan Ivanofvitz” (Larion Ivanov, who became a dumnyi d′iak, or state secretary, in 1669)77 to quarter the rebel, Stepan walked courageously towards the blocks, prayed, made the sign of the cross, and lay down on his belly. His right arm was axed off to the elbow, his left leg to the knee, then his left arm and his right leg, and finally his head. All five severed body parts were set up on poles; the remainder, the trunk, however, was left on the ground. Upon this, Stepan’s brother said that he had something more to tell. He was conducted to the Land Court for a new session of torture, during which he lost consciousness. Like other eyewitnesses, Koch underlines that Stepan did not show any emotions during the torture, whereas his brother cried and was reproached by Stepan: “You son of a bitch, why do you cry? Remember, that you won much honour together with me, and that we had ruled over not only all of the Don, but also over the whole Volga”. The last twelve or thirteen lines of Koch’s correspondence contain other information: a courier is said to have arrived from Count Romodanovskii78—one of the field commanders fighting against the rebelling Cossacks—with word that “Astrakhan and all places that had been won by Razin were now brought back to his Majesty the tsar, and they are asking for mercy”.79 The last two sentences of the letter are dedicated to other issues.

The second “relation” mentioned by Helmfelt and also attached to his own letter of 30 June was written one week later, on 13 June. It contains the well-known story (a rumour?) about the treasure trove of gold, silver, and other precious things hidden near Tsaritsyn, reported by Frol Razin, a story that is also known from a Russian document.80 The men who had dug the hole had all been killed, and now Frol was the only remaining person who knew where it was. We learn that the five poles with Razin’s body parts were brought to the “swamp” (Bollota) on the other side of the Moscow River, and set up again, whereas the trunk was put on the ground, as before. Koch highlights the fact that he had seen all this “three days ago” (which would have been 10 June). We also get some background information about how Razin was taken prisoner by Kornei Iakovlev and his 2000 Don Cossacks, and that the ataman was richly rewarded by the tsar.81 The final—fourth—page is about other issues (for instance, a Polish embassy is expected). All in all, both attachments are typical examples of Koch’s detailed reports from Moscow.

Conclusion

Let us now return to the question of how the newspaper publishers in Western Europe were informed about Muscovy, through the prism of this specific case of the Razin rebellion. We have been able to document some overlap between Koch’s correspondence to Helmfelt, and articles in printed newspapers, but so far, we have found no longer fragments or whole news reports that are virtually identical in the two types of source. As was mentioned above, for another time period—the early 1650s—it has been shown that certain parts of reports to Queen Christina of Sweden, written by Johan de Rodes while he was a Swedish resident in Moscow, also ended up in printed German newspapers, sometimes verbatim, although we still do not know how: did Rodes have contacts with any news agencies, or did the news “leak out” somewhere during the transmission, for instance, in Narva? My hypothesis is that not much had changed when Koch, Rodes’s brother-in-law, was sending his correspondence to Narva in the early 1670s; that is, I think that parts of Koch’s dispatches also ended up in the European news market. It is very difficult to prove this unequivocally as so many numbers of printed seventeenth-century newspapers are lost forever.

A major difference between the 1650s and the 1670s is, of course, the fact that in the meantime an international postal line between Muscovy and Western Europe had been established. For Koch this meant, on the one hand, that he could send his reports to governor Helmfelt in Narva—from which point they were forwarded both to other Swedish-Baltic provinces and to the Swedish government in Stockholm—in a very timely fashion, once a week, every Tuesday; Koch did not have to wait for the next merchant or diplomat to cross the Russian borders, as would have been the case in the 1650s. Since Koch’s correspondence was conveyed by Muscovite officials, this also meant that his dispatches could be opened, read and translated into Russian. He could therefore have written—or rather dictated—slightly different versions to Helmfelt, on the one side, and to a news agent, on the other side, to make certain he would not be blamed personally for any “inconvenient” news about Muscovy that had made its way into the international European press.82 However, in this case modern scholars, too, might never be able to really prove any direct or indirect connections between Koch and the news market. Even if we do not have, at this moment, any strong evidence that Koch’s reports in one way or another ended up in European newspapers, we can be fairly sure that the news market was being fed with Moscow news by men like Koch—well-informed merchants and diplomats with good relations to the tsar’s entourage, who were gathering news, in the first place, for the governments in their respective home countries. Koch, with his superb knowledge of Russian politics and culture, with his knowledge of the Russian language, and his (at that time) excellent relationship with the Russian political elite (especially Matveev), would have been an ideal person to gather news about Muscovy.83

Koch’s newsletters—at least the ones we have found in the Swedish archives—were sent to Narva, and we know that copies were made in Narva: not only the Swedish government in Stockholm, but also Governor Horn in Reval, and quite certainly the governors in the other Swedish provinces on the Baltic littoral, were provided with copies of the reports that Helmfelt received from Moscow, Novgorod, and Pskov. Both the Narva copyist and those who received the new copies might have handed over “Koch news” to a news agent, so even if we eventually find overlapping verbatim passages in Koch’s newsletters and in the press, we still will not know the exact connection: was it Koch personally who fed the “Moscow news market” with his information, or was it somebody who had seen, or copied, his reports?

An important result of this study is that we know the Russian authorities, during the reign of Tsar Aleksei Mikhailovich, were more actively engaged in spreading their viewpoints (or their talking points) to foreigners living in Muscovy than we used to think, and, as a result, we might have to reconsider Muscovy’s “information policy” during this period. It has long been known that the Ambassadorial Chancery collected news from abroad (for instance, among other sources, via translations of handwritten and printed newspapers from Germany and the Netherlands; see the chapters by Waugh, and Waugh and Maier, in this volume). However, very little has been known about the manner and the degree to which the Kremlin actively manipulated Muscovy’s image in Western Europe. We have read about the tsar’s attempts to create a better image of Russia in the world by soliciting foreign governments to reprimand their gazetteers, or even punish them, if those writers had printed any “lies” about the tsar or his country.84 These attempts never worked out well, because, among other reasons, the Russian government’s ability to influence the press in countries like the Dutch Republic and the German Empire was very limited. Perhaps people like Matveev, the great “Westerniser”, had already grasped that there was a more influential way to manipulate public opinion about Russia abroad, that is, by making use of the foreign correspondents living in Muscovy itself. This chapter has shown that Muscovite authorities handed over official statements to Koch at several instances, and we can be sure that Koch was not the only foreigner who was given such “favour”. In his report of 6 June 1671, written immediately after Razin’s execution, Koch mentions the communication—Razin’s “wicked deed” and the verdict—that was publicly read aloud on Red Square, and we should recall his comment “I will try to get this [text] and send it over”. Apparently, he knew that it would not be difficult to acquire this document. Although I have not yet seen it in the Swedish archives, it might well be there,85 and in any event we have evidence that this “verdict” was handed over to foreigners, since it appeared in print, for instance, in Kort waerachtigh verhael, van de bloedige rebellye in Moscovien […]86 and in similar German, English, and French printed versions of the years 1671–72.87 It also appears that the Kremlin was disseminating other documents: in one case a coloured drawing—undoubtedly produced in a Muscovite chancery—ended up in at least three countries (Sweden, England, and Germany); I do not doubt that even more copies were produced, although it seems that only one is preserved today (and two have left indirect traces behind them). Spreading “pictorial proof” of the executed Razin’s body parts was a means of fighting against rumours of his successes. In another case, as we have seen, the tsar’s official declaration about Razin’s rebellion, sent to Novgorod to be read aloud to the crowds, also ended up in Helmfelt’s hands and was eventually forwarded to the Swedish government in Stockholm. While that statement probably had as its target first and foremost a Muscovite public, it is likely that the tsar would not have protested if such information had been handed over to foreigners in Novgorod; in this case there was always a chance that a specific report would end up in a newspaper. Undoubtedly, the Kremlin tried actively to squelch rumours it did not like and to portray events with a positive spin. The correspondence sent by Governor Helmfelt in Narva to the Swedish king contains many official Russian documents, which may have come into Helmfelt’s hands in the first place through Koch,88 and in the second place through Swedish merchants in Novgorod and Pskov. Of course, not all “official” Russian news that ended up in Koch’s correspondence or in a printed newspaper was spread deliberately by the Kremlin; in some cases—for instance, when we talk about instructions given to Russian ambassadors—we have to suppose that the news had leaked out.

The Swedish diplomatic correspondence from Moscow and Novgorod also shows us something about the Muscovite postal system. Koch usually wrote one newsletter every week (every Tuesday89), and Helmfelt also would send one letter every week to his king. The Muscovite “international” postal line went through Riga (at certain periods there was also another line, through Vilna, today’s Vilnius), but no official Russian postal line connected Novgorod with Narva. However, as Philipp Kilburger writes in his report from 1674, although there is no ordinary postal line between Novgorod and Narva, “almost every week during the whole year there are opportunities to send letters from one place to the other”.90 The mailbag for Narva seems to have left Moscow with the Riga post, which was running once a week; it would be taken out in Novgorod to be put into the Narva post from there.91 So usually Helmfelt would receive weekly reports from Moscow and/or Novgorod, but sometimes the connection in Novgorod missed its departure, which explains the fact that occasionally Helmfelt included Koch’s dispatches from two subsequent weeks into his own report to the Swedish government.92 An interesting example in this connection is Helmfelt’s letter of 30 June 1671, which was sewn together with the two “relations” and the drawing about Razin’s execution: apparently both relations, dated 6 June and 13 June, arrived at Narva on the same day, since Helmfelt mentions both reports in his own communication (and includes copies of both).

This chapter has also shown that the German newspapers—especially the Hamburg Nordischer Mercurius, on which I have focussed in the first place (mostly due to the fact that the complete run for the year 1671 has been preserved)—were not, after all, so bad. During the Razin uprising not even the tsar and his closest advisers were always well-informed about, for instance, the numbers of people killed on each side in a battle, or about Razin’s whereabouts, and when the Muscovite government itself created confusion by stating that the rebel had been captured, long before he was actually seized, we cannot really blame the newspapers for publishing information that later on would prove to be false. As we can still see today, confusing political situations lead to confusing reports in the press; this was all the more true during the seventeenth century, the first century of the printed newspaper. Both Christoff Koch and the publisher of the Nordischer Mercurius constantly stressed the fact that the latest news had not yet been confirmed. Only when it had been verified, from two or more independent sources, did they make it clear to their readers that the news now could be trusted.

1 The research for this chapter was provided primarily by The Swedish Foundation for Humanities and Social Sciences (Riksbankens jubileumsfond, ‘Cross-Cultural Exchange in Early Modern Europe’, RFP12–0055:1). Moreover, the author is most grateful to the National Endowment for the Humanities (RZ-51635–13) who helped to fund several research trips to London, Stockholm, and Bremen. Any views, findings, or conclusions expressed in this chapter do not necessarily represent those of the funding organisations. Holger Böning and Michael Nagel at the research institute Deutsche Presseforschung have made my extended stays in Bremen both productive and enjoyable, providing help in both scholarly and practical issues. My frequent co-author, Daniel Waugh (Seattle), has read two draft versions of this chapter and made numerous very helpful comments; he also pointed out many relevant documents. I also offer my warm thanks to Claudia Jensen, for her editorial help, and to Gleb Kazakov for the discussions, particularly relating to Fig. 2 in the present chapter.

2 Oprechte Haerlemse Dingsdaegse Courant 1671, no. 18 (National Archives London, SP 119/53, fol. 53v), in a news item datelined Moscow, 26 March 1671. Most of the surviving historical Dutch newspapers are now available online at http://kranten.delpher.nl/

3 The term is borrowed from Brian J. Boeck’s monograph Imperial Boundaries. Cossack Communities and Empire-Building in the Age of Peter the Great (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

4 I am focussing on printed newspapers because I have not studied manuscript newspapers—which also played an important role at the time—in any systematic way.

5 See Martin Welke, ‘Rußland in der deutschen Publizistik des 17. Jahrhunderts (1613–1689)’, Forschungen zur osteuropäischen Geschichte, 23 (1976), 105–276 (pp. 151–53 and 255–64).

6 Ibid., p. 203. Welke studied all the issues of printed newspapers in German for the relevant period that were available in the research institute Deutsche Presseforschung in Bremen, which houses copies of more than 60,000 different newspaper issues. When Welke’s dissertation appeared in print, in 1976, the huge collection of German newspapers kept at the Rossiiskii gosudarstvennyi arkhiv drevnikh aktov (RGADA) in Moscow was not yet known in Germany; copies were received in Bremen only at the very end of the 1970s. See V. I. Simonov, ‘Deutsche Zeitungen des 17. Jahrhunderts im Zentralen Staatsarchiv für alte Akten (CGADA), Moskau’, Gutenberg-Jahrbuch, 54 (1979), 210–20. Simonov lists all German-language newspaper issues that have survived in RGADA. To the 640 issues from the period September 1670 until August 1671 which Welke studied we can now add several dozen unique copies printed during the relevant time period in the Eastern part of the German-language territory, above all in Königsberg and in Berlin (ibid., pp. 215, 217).

7 The date 14 April is mentioned in the verdict, read aloud publicly on the day of Stepan Razin’s execution; see the publication of this text in Krest′ianskaia voina pod predvoditel′stvom Stepana Razina, vols 1–4 (Moscow: Izdatel′stvo Akademii nauk, 1954–1976), here vol. 3, no. 81, p. 87. See also André Berelowitch, ‘Stenka Razin’s Rebellion: The Eyewitnesses and their Blind Spot’, in From Mutual Observation to Propaganda War: Premodern Revolts in their Transnational Representations, ed. by Malte Griesse (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2014), pp. 93–124 (p. 105).

8 Inostrannye izvestiia o vosstanii Stepana Razina. Materialy i issledovaniia, ed. by A. G. Man′kov (Leningrad: Nauka, 1975), pp. 92–93.

9 “[…] and trade with Prussia and Russia will probably come to a sudden standstill, and Moscow will be in great disorder because all salted fish—which is so important for this nation, because of a high number of fasting-days—and also the salt used to come here [from that place], and every year 40 000 horses from that region were brought to the tsar […]” (Man′kov, Inostrannye izvestiia, p. 93). The number of horses seems very high, and generally numbers (e.g., of Razin’s followers, or of those killed) given in newspaper articles are far too high. On the other hand, the information about the consequences for trade within Muscovy makes it clear that the author of that correspondence from Moscow must have had a very good knowledge of Muscovite trade. Cf. also the partially overlapping information in Nordischer Mercurius, pp. 587–88 (quoted Man′kov, p. 95).

10 Cf. Daniel C. Waugh and Ingrid Maier, ‘How Well Was Muscovy Connected with the World?’, in Imperienvergleich. Beispiele und Ansätze aus osteuropäischer Perspektive. Festschrift für Andreas Kappeler, ed. by Guido Hausmann and Angela Rustemeyer, Forschungen zur osteuropäischen Geschichte, vol. 75 (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2009), pp. 17–38 (pp. 31, 33). The timespan of twenty or, at most, twenty-one days for mail from Moscow to reach Hamburg, mentioned in a news item in Nordischer Mercurius, datelined Moscow, 17 August 1668, is quite optimistic; only under optimal conditions could a letter from Moscow to Hamburg reach its addressee so fast. Some years later, in 1674, Philipp Kilburger gives the same optimistic view regarding the transmission time from Moscow to Hamburg: twenty-one days via Vilna and twenty-three days via Riga; see B. G. Kurts, Sochinenie Kil′burgera o russkoi torgovle v tsarstvovanie Alekseia Mikhailovicha (Kiev: Tip. I. I. Chokolova, 1915), p. 160.

11 Welke, ‘Rußland’, p. 204, no. 444.

12 See A. L. Gol′dberg, ‘K istorii soobshcheniia o vosstanii Stepana Razina’, in Zapiski inostrantsev o vosstanii Stepana Razina, ed. by A. G. Man′kov (Leningrad: Nauka, 1968), pp. 157–65; Berelowitch, ‘Stenka Razin’s Rebellion’, p. 97.

13 Man′kov, Zapiski inostrantsev and Inostrannye izvestiia.

14 Krest′ianskaia voina.

15 A very insightful treatment of the development of the news market is in the recent book by Andrew Pettegree, The Invention of News. How the World Came to Know about Itself (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2014). About the problem of “establishing the veracity of news reports” (regarding commercial manuscript newsletters), see especially pp. 2–3 and 115–16.

16 Mittwochischer Mercurius, zur 8. Woche 1671 gehörig, news item “Ein anders/ vom vorigen” (= Hamburg, 17 Feb.) on p. [2]. The only surviving original is in Moscow (RGADA, coll. 155, descr. 1, 1671, no. 3, fol. 22v). There is a cross mark in the margins exactly next to this sentence—apparently, this is a translator’s mark.

17 Welke, ‘Rußland’, p. 203.

18 The regular newspaper issues have a continuous pagination for the whole year, and title pages only for every new month and new year; other issues indicate only the year and the current month in the same line (for instance, “Anno 1671. Majus”.). This “yearbook character” might have been the reason for the fact that some complete year collections of the Nordischer Mercurius have survived: the newspaper was not always used to wrap sandwiches, but at least some subscribers kept all their issues and took them to the book binder at the end of the year. For the year 1671 two complete collections are known, one in Deichmanske bibliotek in Oslo, the other in the Royal Library of Copenhagen (signature: 147.15); there are copies, as always, in Bremen (Deutsche Presseforschung). The entire Bremen collection has been digitised over the past few years and is now available at http://brema.suub.uni-bremen.de/zeitungen17/

19 Nordischer Mercurius, May 1671, p. 288. The source here alludes to the fact that Muscovy, in common with many parts of Western Europe, still used the Julian calendar (the ‘old style’), in contrast with the Gregorian calendar (the ‘new style’) that had been introduced for most Catholic countries in 1582.

20 Cf. also Welke, ‘Rußland’, p. 203f.

21 The Russian translation is in RGADA, coll. 155, descr. 1, 1671, no. 7, fol. 158. The kuranty (compilations of foreign news that were produced regularly at the Ambassadorial Chancery) for the years 1671–72 are being prepared for publication under the title Vesti-Kuranty 1671–1672 gg. and will be printed in 2017. I have not been able to locate the original news item in German, which presumably was in a printed newspaper from Berlin or Königsberg that has not survived, so my translation is from the Russian version. The relevant printed papers had arrived in Moscow via the Vilna postal line on 6 July 1671; see RGADA, ibid., fol. 155.

22 Krest′ianskaia voina, vol. 3, no. 56, p. 62 and no. 58, p. 64.

23 The slightly abbreviated Russian translation is in RGADA, coll. 155, descr. 1, 1671, no. 7, fol. 6v-7, the Dutch original in Haegse Dynsdaeghse Post-tydinge no. 14, preserved in RGADA, coll. 155, descr. 1, 1671, file 5, fol. 8. My translation is made from the Dutch original, not from the Russian version. Cf. also Ingrid Maier and Stepan Shamin, ‘“Revolts” in the Kuranty of March-July 1671’, in From Mutual Observation to Propaganda War, ed. by Griesse, pp. 181–203 (p. 193, with an English translation of the kuranty version).

24 Maier and Shamin, ‘“Revolts” in the Kuranty’.

25 Swedish State Archives in Stockholm (SSAS), Diplomatica Muscovitica, vol. 83 (not paginated). Since the letter to the (anonymous) “Hochgeehrter H. Bruder” (‘highly honoured brother’) was preserved among Adolf Eberschildt’s letters to the Swedish king, it is most likely that the diplomat Eberschildt was the addressee.

26 Peter Marselis, who had administrated the Russian post for a couple of years.

27 Nordischer Mercurius (June 1671), p. 380.

28 Nordischer Mercurius (April 1671), p. 217.

29 Ibid., p. 253.

30 Ordinariæ Relationes 1671, no. 36 (printing date: 5 May 1671). The complete year collection is in private possession, at the Castle of Herdringen in Arnsberg, Westphalia (shelf number: Fü 3301a). The original Latin text reads: “Lembergo, 27. Martii. […] Ex Moscovia resciimus rebellionem indies turpiorem accrescere, & mortem Magno Moscorum Principi rebelles minari: agricolæ & ex infima hominum fœce quamplurimi ad castra rebellantis Stephani Raninii confugiunt, vident enim Moscorum Principem resistendo imparem, seseque sub moderamine Stephani quam Principis imperio tutius victuros”. My thanks to the owner, Baron Wennemar von Fürstenberg, for letting me work with his unique collection on several occasions, and to Winfried Schumacher (Cologne) for his help with the translation from the Latin.

31 Nordischer Mercurius (February 1671), p. 74.

32 Nordischer Mercurius (March 1671), p. 188.

33 At a meeting of the Swedish Council of the Realm on Saturday, 29 July 1671, the councillor of the realm and governor general of Swedish Livonia, Count Clas Åkesson Tott Junior (1630–74), informed his colleagues that he, at the order of the king, had awarded von Staden a pension of 1000 dalers. The payment was for von Staden’s successful attempts in making “Artemon” favourably disposed towards Sweden. This refers to Artamon Sergeevich Matveev, head of the Ambassadorial Chancery since spring 1671. The council decided that a bill of exchange of 500 dalers should be sent to Inspector Möller in Riga, apparently to hand the money over to von Staden at his next visit to his home town. See SSAS, Odelade kansli, Riksrådsprotokoll, vol. 58. My thanks to Heiko Droste for a transcription of the quoted protocol. See also von Staden’s letter sent from Novgorod and dated 24 September (no year; probably 1672), signed by him personally, which was quoted on p. 121. Count Tott—with whom von Staden had been in contact—and “Stenca Raisin” are mentioned. See SSAS, Diplomatica Muscovitica, vol. 83 (not foliated; among letters from autumn 1672).

34 Nordischer Mercurius (February 1671), p. 104.

35 Nordischer Mercurius (July 1671), p. 417 [recte: 427].

36 Ibid., p. 428.

37 The date 2 June is mentioned in Krest′ianskaia voina, vol. 3, no. 99, p. 106 and no. 104, p. 114. We have the same date in Christoff Koch’s eyewitness report of 6 June 1671, sent to the Swedish governor general in Narva, Simon Grundel-Helmfelt (SSAS, Livonica II, vol. 180, Moscow attachment of 6 June 1671).