2. Core Ideas and the Framework

© 2017 Ingrid Robeyns, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0130.02

2.1 Introduction

The previous chapter listed a range of fields in which the capability approach has been taken up, and in chapters 3 and 4 we focus in more detail on how the capability approach can (or cannot) make a difference for thinking about wellbeing, social and distributive justice, human rights, welfare economics and other topics. This broad uptake of the capability approach across disciplines and across different types of knowledge production (from theoretical and abstract to applied or policy oriented) is testimony to its success. But how is the capability approach understood in these different fields, and is it possible to give a coherent and clarifying account of how we can understand the capability approach across those fields?1 In other words, how should we understand the capability approach as an overarching framework, that unites its more specific uses in different fields and disciplines?

This chapter gives an account of that general framework. It provides explanations and insights into what the capability approach is, what its core claims are, and what additional claims we should pay attention to. This chapter will also answer the question: what do we mean exactly when we say that the capability approach is a framework or an approach?

In other words, in this chapter, I will give an account (or a description) of the capability approach at the most general level. I will bracket additional details and questions about which disagreement or confusion exists; chapter 3 will offer more detailed clarifications and chapter 4 will discuss issues of debate and dispute. Taken together, these three chapters provide my understanding of the capability approach.

Chapter 2 is structured as follows. In the next section, we look at a preliminary definition of the capability approach. Section 2.3 proposes to make a distinction between ‘the capability approach’ and ‘a capability theory’. This distinction is crucial — it will help us to clarify various issues that we will look at in this book, and it also provides some answers to the sceptics of the capability approach whom we encountered in the previous chapter. Section 2.4 describes, from a bottom-up perspective, the many ways in which the capability approach has been developed within particular theories, and argues why it is important to acknowledge the great diversity within capabilitarian scholarship. Sections 2.5 to 2.11 present an analytic account of the capability approach, and show what is needed to develop a particular capability theory, application or analysis. In 2.5, I propose the modular view of the capability approach, which allows us to distinguish between three different types of modules that make up a capability theory. The first, the A-module, consists of those properties that each capability theory must have (section 2.6). This is the non-optional core of each capability theory. The B-modules are a set of modules in which the module itself is non-optional, but there are different possible choices regarding the content of the module (section 2.7). For example, we cannot have a capability theory or application without having chosen a purpose for that theory or application — yet there are many different purposes among which we can choose. The third group of modules, the C-modules, are either non-optional but dependent on a choice made in the B-modules, or else are completely optional. For example, if the purpose you choose is to measure poverty, then you need to decide on some empirical methods in the C-modules; but if your aim is to make a theory of justice, you don’t need to choose empirical methods and hence the C-module for empirical methods (module C3) is not relevant for your capability application (section 2.8).2 In the next section, 2.9, I discuss the possibility of hybrid theories — theories that give a central role to functionings and capabilities yet violate some other core proposition(s). Section 2.11 rounds up the discussion of the modular view by discussing the relevance and advantages of seeing the capability approach from this perspective.

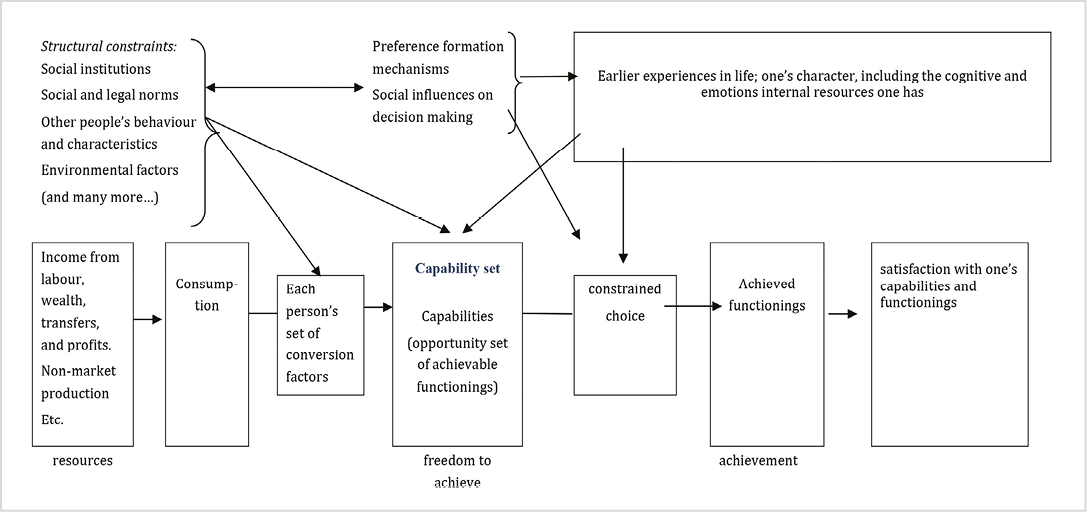

Section 2.12 summarises the conceptual aspects that have been explained by presenting a visualisation of the conceptual framework of the capability approach. Section 2.13 uses the modular view to illuminate the observation, which has been made by several capability scholars, that the capability approach has been used in a narrow and in a broad sense, and explains what difference lies behind this distinction. In the broader use of the capability approach, supporting or complementary theories or additional normative principles are added to the core of the approach — yet none of them is itself essential to the capability approach. These are choices made in B-modules or the C-modules. The modular view of the capability approach that will be central to this chapter can thus help to formulate in a sharper manner some observations that have already been made in the capability literature. The chapter closes by looking ahead to the next chapter.

2.2 A preliminary definition of the capability approach

The capability approach has in recent decades emerged as a new theoretical framework about wellbeing, freedom to achieve wellbeing, and all the public values in which either of these can play a role, such as development and social justice. Although there is some scholarly disagreement on the best description of the capability approach (which will be addressed in this chapter), it is generally understood as a conceptual framework for a range of evaluative exercises, including most prominently the following: (1) the assessment of individual levels of achieved wellbeing and wellbeing freedom; (2) the evaluation and assessment of social arrangements or institutions;3 and (3) the design of policies and other forms of social change in society.

We can trace some aspects of the capability approach back to, among others, Aristotle, Adam Smith, Karl Marx and John Stuart Mill,4 yet it is Sen who pioneered the approach and a growing number of other scholars across the humanities and the social sciences who have significantly developed it — most significantly Martha Nussbaum, who has developed the capability approach into a partial theory of social justice.5 Nussbaum also understands her own capabilities account as a version of a theory of human rights.6 The capability approach purports that freedom to achieve wellbeing is a matter of what people are able to do and to be, and thus the kind of life they are effectively able to lead. The capability approach is generally conceived as a flexible and multipurpose framework, rather than a precise theory (Sen 1992a, 48; Alkire 2005; Robeyns 2005b, 2016b; Qizilbash 2012; Hick and Burchardt 2016, 78). The open-ended and underspecified nature of the capability approach is crucial, but it has not made it easier for its students to understand what kind of theoretical endeavour the capability approach exactly is. How should we understand it? Isn’t there a better account possible than the somewhat limited description of the capability approach as ‘an open, flexible and multi-purpose framework’? Answering these questions will be the task of this chapter.7

The open and underspecified nature of the capability approach also explains why the term ‘capability approach’ was adopted and is now widely used rather than ‘capability theory’. Yet as I will argue in section 2.3, we could use the terms ‘capability theory’ and ‘capability approach’ in a more illuminating way to signify a more substantive difference, which will help us to get a better grip on the capability literature.

It may be helpful to introduce the term ‘advantage’ here, which is a technical term used in academic debates about interpersonal comparisons and in debates about distributive justice.8 A person’s advantage is those aspects of that person’s interests that matter (generally, or in a specific context). Hence ‘advantage’ could refer to a person’s achieved wellbeing, or it could refer to her opportunity to achieve wellbeing, or it could refer to her negative freedoms, or to her positive freedoms, or to some other aspect of her interests. By using the very general term ‘advantage’, we allow ourselves to remain agnostic between the more particular specifications of that term;9 our analysis will apply to all the different ways in which ‘advantage’ could be used. This technical term ‘advantage’ thus allows us to move the arguments to a higher level of generality or abstraction, since we can focus, for example, on which conditions interpersonal comparisons of advantage need to meet, without having to decide on the exact content of ‘advantage’.

Within the capability approach, there are two different specifications of ‘advantage’: achieved wellbeing, and the freedom to achieve wellbeing. The notions of ‘functionings’ and ‘capabilities’ — which will be explained in detail in section 2.6.1 — are used to flesh out the account of achieved wellbeing and the freedom to achieve wellbeing.10 Whether the capability approach is used to analyse distributive injustice, or measure poverty, or develop curriculum design — in all these projects the capability approach prioritises certain people’s beings and doings and their opportunities to realize those beings and doings (such as their genuine opportunities to be educated, their ability to move around or to enjoy supportive social relationships). This stands in contrast to other accounts of advantage, which focus exclusively on mental categories (such as happiness) or on the material means to wellbeing (such as resources like income or wealth).11

Thus, the capability approach is a conceptual framework, which is in most cases used as a normative framework for the evaluation and assessment of individual wellbeing and that of institutions, in addition to its much more infrequent use for non-normative purposes.12 It can be used to evaluate a range of values that draw on an assessment of people’s wellbeing, such as inequality, poverty, changes in the wellbeing of persons or the average wellbeing of the members of a group. It can also be used as an evaluative tool providing an alternative for social cost-benefit analysis, or as a framework within which to design and evaluate policies and institutions, such as welfare state design in affluent societies, or poverty reduction strategies by governments and non-governmental organisations in developing countries.

What does it mean, exactly, if we say that something is a normative analysis? Unfortunately, social scientists and philosophers use these terms slightly differently. My estimate is that, given their numerical dominance, the terminology that social scientists use is dominant within the capability literature. Yet the terminology of philosophers is more refined and hence I will start by explaining the philosophers’ use of those terms, and then lay out how social scientists use them.

What might a rough typology of research in this area look like? By drawing on some discussions on methods in ethics and political philosophy (O. O’Neill 2009; List and Valentini 2016), I would like to propose the following typology for use within the capability literature. There are (at least) five types of research that are relevant for the capability approach. The first type of scholarship is conceptual research, which conducts conceptual analysis — the investigation of how we should use and understand certain concepts such as ‘freedom’, ‘democracy’, ‘wellbeing’, and so forth. An example of such conceptual analysis is provided in section 3.3, where I offer a (relatively simple) conceptual analysis of the question of what kind of freedoms (if any) capabilities could be. The second strand of research is descriptive. Here, research and analyses provide us with an empirical understanding of a phenomenon by describing it. This could be done with different methods, from the thick descriptions provided by ethnographic methods to the quantitative methods that are widely used in mainstream social sciences. The third type of research is explanatory analysis. This research provides an explanation of a phenomenon — what the mechanisms are that cause a phenomenon, or what the determinants of a phenomenon are. For example, the social determinants of health: the parameters or factors that determine the distribution of health outcomes over the population. A fourth type of research is evaluative, and consists of analyses in which values are used to evaluate a state of affairs. A claim is evaluative if it relies on evaluative terms, such as good or bad, better or worse, or desirable or undesirable. Finally, an analysis is normative if it is prescriptive — it entails a moral norm that tells us what we ought to do.13 Evaluative analyses and prescriptive analyses are closely intertwined, and often we first conduct an evaluative analysis, which is followed by a prescriptive analysis, e.g. by policy recommendations, as is done, for example, in the evaluative analysis of India’s development conducted by Jean Drèze and Amartya Sen (2013). However, one could also make an evaluative analysis while leaving the prescriptive analysis for someone else to make, perhaps leaving it to the agents who need to make the change themselves. For example, one can use the capability approach to make an evaluation or assessment of inequalities between men and women, without drawing prescriptive conclusions (Robeyns 2003, 2006a). Or one can make a prescriptive analysis that is not based on an evaluation, because it is based on universal moral rules. Examples are the capability theories of justice by Nussbaum (2000; 2006b) and Claassen (2016).

The difference with the dominant terminology used by economists (and other social scientists) is that they only distinguish between two types of analysis: ‘positive’ versus ‘normative’ economics, whereby ‘positive’ economics is seen as relying only on ‘facts’, whereas ‘normative economics’ also relies on values (e.g. Reiss 2013, 3). Hence economists do not distinguish between what philosophers call ‘evaluative analysis’ and ‘normative analysis’ but rather lump them both together under the heading ‘normative analysis’. The main take-home message is that the capability approach is used predominantly in the field of ethical analysis (philosophers’ terminology) or normative analysis (economists’ terminology), somewhat less often in the fields of descriptive analysis and conceptual analysis, and least in the field of explanatory analysis. We will revisit this in section 3.10, where we address whether the capability approach can be an explanatory theory.

2.3 The capability approach versus capability theories

The above preliminary definition highlights that the capability approach is an open-ended and underspecified framework, which can be used for multiple purposes. It is open-ended because the general capability approach can be developed in a range of different directions, with different purposes, and it is underspecified because additional specifications are needed before the capability approach can become effective for a particular purpose — especially if we want it to be normative (whether evaluative or prescriptive). As a consequence, ‘the capability approach’ itself is an open, general idea, but there are many different ways to ‘close’ or ‘specify’ this notion. What is needed for this specifying or closing of the capability approach will depend on the aim of using the approach, e.g. whether we want to develop it into a (partial) theory of justice, or use it to assess inequality, or conceptualise development, or use it for some other purpose.

This distinction between the general, open, underspecified capability approach, and its particular use for specific purposes is absolutely crucial if we want to understand it properly. In order to highlight that distinction, but also to make it easier for us to be clear when we are talking about the general, open, underspecified capability approach, and when we are talking about a particular use for specific purposes, I propose that we use two different terms (Robeyns 2016b, 398). Let us use the term ‘the capability approach’ for the general, open, underspecified approach, and let us employ the term ‘a capability theory’ or ‘a capability analysis, capability account or capability application’ for a specific use of the capability approach, that is, for a use that has a specific goal, such as measuring poverty and deriving some policy prescriptions, or developing a capabilitarian cost-benefit analysis, or theorising about human rights, or developing a theory of social justice. In order to improve readability, I will speak in what follows of ‘a capability theory’ as a short-hand for ‘a capability account, or capability application, or capability theory’.14

One reason why this distinction between ‘capability approach’ and ‘capability theory’ is so important, is that many theories with which the capability approach has been compared over time are specific theories, not general open frameworks. For example, John Rawls’s famous theory of justice is not a general approach but rather a specific theory of institutional justice (Rawls 2009), and this has made the comparison with the capability approach at best difficult (Robeyns 2008b). The appropriate comparison would be Rawls’s theory of justice with a properly developed capability theory of justice, such as Nussbaum’s Frontiers of Justice (Nussbaum 2006b), but not Rawls’s theory of justice with the (general) capability approach.

Another reason why the distinction between ‘capability approach’ and ‘capability theory’ is important, is that it can help provide an answer to the “number of authors [who] ‘complain’ that the capability approach does not address questions they put to it” (Alkire 2005, 123). That complaint is misguided, since the capability approach cannot, by its very nature, answer all the questions that should instead be put to particular capability theories. For example, it is a mistake to criticise Amartya Sen because he has not drawn up a specific list of relevant functionings in his capability approach; that critique would only have bite if Sen were to develop a particular capability theory or capability application where the selection of functionings is a requirement.15

In short, there is one capability approach and there are many capability theories, and keeping that distinction sharply in mind should clear up many misunderstandings in the literature.

However, if we accept the distinction between capability theories and the capability approach, it raises the question of what these different capability theories have in common. Before addressing that issue, I first want to present a bottom-up description of the many modes in which capability analyses have been conducted. This will give us a better sense of what the capability approach has been used for, and what it can do for us.

2.4 The many modes of capability analysis

If the capability approach is an open framework, then what are the ways in which it has been closed to form more specific and powerful analyses? Scholars use the capability approach for different types of analysis, with different goals, relying on different methodologies, with different corresponding roles for functionings and capabilities. Not all of these are capability theories; some are capability applications, both empirical as well as theoretical. We can observe that there is a rich diversity of ways in which the capability approach has been used. Table 2.1 gives an overview of these different usages, by listing the different types of capability analyses.

Normative theorising within the capability approach is often done by moral and political philosophers. The capability approach is then used as one element of a normative theory, such as a theory of justice or a theory of disadvantage. For example, Elizabeth Anderson (1999) has proposed the outlines of a theory of social justice (which she calls “democratic equality”) in which certain basic levels of capabilities that are needed to function as equal citizens should be guaranteed to all. Martha Nussbaum (2006b) has developed a minimal theory of social justice in which she defends a list of basic capabilities that everyone should be entitled to, as a matter of human dignity.

While most normative theorising within the capability approach has related to justice, other values have also been developed and analysed using the capability approach. Some theorists of freedom have developed accounts of freedom or rights using the capability approach (van Hees 2013). Another important value that has been studied from the perspective of the capability approach is ecological sustainability (e.g. Anand and Sen 1994, 2000; Robeyns and Van der Veen 2007; Lessmann and Rauschmayer 2013; Crabtree 2013; Sen 2013). Efficiency is a value about which very limited conceptual work is done, but which nevertheless is inescapably normative, and it can be theorised in many different ways (Le Grand 1990; Heath 2006). If we ask what efficiency is, we could answer by referring to Pareto optimality or x-efficiency, but we could also develop a notion of efficiency from a capability perspective (Sen 1993b). Such a notion would answer the question ‘efficiency of what?’ with ‘efficiency in the space of capabilities (or functionings, or a mixture)’.

Table 2.1 The main modes of capability analysis

|

Epistemic goal |

Methodology/discipline |

Role of functionings and capabilities |

Examples |

|

Normative theories (of particular values), e.g. theories of justice, human rights, wellbeing, sustainability, efficiency, etc. |

Philosophy, in particular ethics and normative political philosophy. |

The metric/currency in the interpersonal comparisons of advantage that are entailed in the value that is being analysed. |

Sen 1993b; Anand and Sen 1994; Crabtree 2012, 2013; Lessmann and Rauschmayer 2013; Robeyns 2016c; Nussbaum 1992, 1997; Nussbaum 2000; Nussbaum 2006b; Wolff and De-Shalit 2007. |

|

Normative applied analysis, including policy design. |

Applied ethics (e.g. medical ethics, bio-ethics, economic ethics, development ethics etc.) and normative strands in the social sciences. |

A metric of individual advantage that is part of the applied normative analysis. |

Alkire 2002; Robeyns 2003; Canoy, Lerais and Schokkaert 2010; Holland 2014; Ibrahim 2017. |

|

Welfare/quality of life measurement. |

Quantitative empirical strands within various social sciences. |

Social indicators. |

Kynch and Sen 1983; Sen 1985a; Kuklys 2005; Alkire and Foster 2011; Alkire et al. 2015; Chiappero-Martinetti 2000. |

|

Thick description/descriptive analysis. |

Qualitative empirical strands within various humanities and social sciences. |

Elements of a narrative. |

Unterhalter 2003b; Conradie 2013. |

|

Understanding the nature of certain ideas, practices, notions (other than the values in the normative theories). |

Conceptual analysis. |

Used as part of the conceptualisation of the idea or notion. |

Sen 1993b; Robeyns 2006c; Wigley and Akkoyunlu-Wigley 2006; van Hees 2013. |

|

[Other goals?] |

[Other methods?] |

[Other roles?] |

[Other studies may be available/are needed.] |

Source: Robeyns (2005a), expanded and updated.

Quantitative social scientists, especially economists, are mostly interested in measurement. This quantitative work could serve different purposes, e.g. the measurement of multidimensional poverty analysis (Alkire and Foster 2011; Alkire et al. 2015), or the measurement of the disadvantages faced by disabled people (Kuklys 2005; Zaidi and Burchardt 2005). Moreover, some quantitative social scientists, mathematicians, and econometricians have been working on investigating the methods that could be used for quantitative capability analyses (Kuklys 2005; Di Tommaso 2007; Krishnakumar 2007; Krishnakumar and Ballon 2008; Krishnakumar and Nagar 2008).

Thick description or descriptive analysis is another mode of capability analysis. For example, it can be used to describe the realities of schoolgirls in countries that may have formal access to school for both girls and boys, but where other hurdles (such as high risk of rape on the way to school, or the lack of sanitary provisions at school) mean that this formal right is not enough to guarantee these girls the corresponding capability (Unterhalter 2003b).

Finally, the capability approach can be used for conceptual work beyond the conceptualisation of values, as is done within normative philosophy. Sometimes the capability approach lends itself well to providing a better understanding of a certain phenomenon. For example, we could understand education as a legal right or as an investment in human capital, but we could also conceptualise it as the expansion of a capability, or develop an account of education that draws on both the capability approach and human rights theory. This would not only help us to look differently at what education is; a different conceptualisation would also have normative implications, for example related to the curriculum design, or to answer the question of what is needed to ensure that capability, or of how much education should be guaranteed to children with low potential market-related human capital (McCowan 2011; Nussbaum 2012; Robeyns 2006c; Walker 2012a; Walker and Unterhalter 2007; Wigley and Akkoyunlu-Wigley 2006).

Of course, texts and research projects often have multiple goals, and therefore particular studies often mix these different goals and methods. Jean Drèze and Amartya Sen’s (1996, 2002, 2013) comprehensive analyses of India’s human development achievements are in part an evaluative analysis based on various social indicators, but also in part a prescriptive analysis. Similarly, Nussbaum’s (2000) book Women and Human Development is primarily normative and philosophical, but also includes thick descriptions of how institutions enable or hamper people’s capabilities, by focussing on the lives of particular women.

What is the value of distinguishing between different uses of the capability approach? It is important because functionings and capabilities — the core concepts in the capability approach — play different roles in each type of analysis. In quality of life measurement, the functionings and capabilities are the social indicators that reflect a person’s quality of life. In thick descriptions and descriptive analysis, the functionings and capabilities form part of the narrative. This narrative can aim to reflect the quality of life, but it can also aim to understand some other aspect of people’s lives, such as by explaining behaviour that might appear irrational according to traditional economic analysis, or revealing layers of complexities that a quantitative analysis can rarely capture. In philosophical reasoning, the functionings and capabilities play yet another role, as they are often part of the foundations of a utopian account of a just society or of the goals that morally sound policies should pursue.

The flexibility of functionings and capabilities, which can be applied in different ways within different types of capability analysis, means that there are no hard and fast rules that govern how to select the relevant capabilities. Each type of analysis, with its particular goals, will require its own answer to this question. The different roles that functionings and capabilities can play in different types of capability analyses have important implications for the question of how to select the relevant capabilities: each type of analysis, with its particular goals, will require its own answer to this question. The selection of capabilities as social indicators of the quality of life is a very different undertaking from the selection of capabilities for a utopian theory of justice: the quality standards for research and scholarship are different, the epistemic constraints of the research are different, the best available practices in the field are different. Moral philosophers, quantitative social scientists, and qualitative social scientists have each signed up to a different set of meta-theoretical assumptions, and find different academic practices acceptable and unacceptable. For example, many ethnographers tend to reject normative theorising and also often object to what they consider the reductionist nature of quantitative empirical analysis, whereas many economists tend to discard the thick descriptions by ethnographers, claiming they are merely anecdotal and hence not scientific.

Two remarks before closing this section. First, providing a typology of the work on the capability approach, as this section attempts to do, remains work in progress. In 2004, I could only discern three main modes of capability analysis: quality of life analysis; thick description/descriptive analysis; and normative theories — though I left open the possibility that the capability approach could be used for other goals too (Robeyns 2005a). In her book Creating Capabilities, Nussbaum (2011) writes that the capability approach comes in only two modes: comparative qualify of life assessment, and as a theory of justice. I don’t think that is correct: not all modes of capability analysis can be reduced to these two modes, as I have argued elsewhere in detail (Robeyns 2011, 2016b). The different modes of capability analysis described in table 2.1 provide a more comprehensive overview, but we should not assume that this overview is complete. It is quite likely that table 2.1 will, in due course, have to be updated to reflect new types of work that uses the capability approach. Moreover, one may also prefer another way to categorise the different types of work done within the capability literature, and hence other typologies are possible and may be more illuminating.

Second, it is important that we fully acknowledge the diversity of disciplines, the diversity of goals we have for the creation of knowledge, and the diversity of methods used within the capability approach. At the same time, we need not forget that some aspects of its development might need to be discipline-specific, or specific for one’s goals. As a result, the capability approach is at the same time multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, but also forms part of developments within disciplines and methods. These different ‘faces’ of the capability approach all need to be fully acknowledged if we want to understand it in a nuanced and complete way.

2.5 The modular view of the capability approach

It is time to take stock. What do we already know about the capability approach, and what questions are raised by the analysis so far? The capability approach is an open approach, and depending on its purpose can be developed into a range of capability theories or capabilitarian applications. It is focused on what people can do and be (their capabilities) and on what they are actually achieving in terms of beings and doings (their functionings). However, this still does not answer the question of what kind of framework the capability approach is. Can we give an account of a capability theory that is more enlightening regarding what exactly makes a theory a capabilitarian theory, and what doesn’t?

In this book, I present an account of the capability approach that, on the one hand, makes clear what all capability theories share, yet on the other hand allows us to better understand the many forms that a capability theory or capability account can take — hence to appreciate the diversity within the capability approach more fully. The modular view that I present here is a modified (and, I hope, improved) version of the cartwheel model that I have developed elsewhere (Robeyns 2016b). The modular view shifts the focus a little bit from the question of how to understand the capability approach in general, to the question of how the various capability accounts, applications and theories should be understood and how they should be constructed. After all, students, scholars, policy makers and activists are often not concerned with the capability approach in general, but rather want to know whether it would be a smart idea to use the capability approach to construct a particular capability theory, application or account for the problem or question they are trying to analyse. In order to answer the question of whether, for their purposes, the capability approach is a helpful framework to consider, they need to know what is needed for a capability theory, application or account. The modular view that will follow will give those who want to develop a capability theory, application or analysis a list of properties their theory has to meet, a list of choices that need to be made but in which several options regarding content are possible, and a list of modules that they could take into account, but which will not always be necessary.

Recall that in order to improve readability, I use the term ‘a capability theory’ as a short-hand for ‘a capability account, or capability analysis, or capability application, or capability theory’. A capability theory is constructed based on three different types of module, which (in order to facilitate discussion) will be called the A-module, B-modules and C-modules. The A-module is a single module which is compulsory for all capability theories. The A-module consists of a number of propositions (definitions and claims) which a capability theory should not violate. This is the core of the capability approach, and hence entails those properties that all capability theories share. The B-modules consist of a range of non-optional modules with optional content. That is, if we construct a capability theory, we have to consider the issue that the module addresses, but there are several different options to choose from in considering that particular issue. For example, module B1 concerns the ‘purpose’ of the theory: do we want to make a theory of justice, or a more comprehensive evaluative framework for societal institutions, or do we want to measure poverty or inequality, or design a curriculum, or do we want to use the capability approach to conceptualise ‘social progress’ or ‘efficiency’ or to rethink the role of universities in the twenty-first century? All these purposes are possible within the capability approach. The point of seeing these as B-modules is that one has to be clear about one’s purpose, but there are many different purposes possible. The C-modules are either contingent on a particular choice made in a B-module, or they can be fully optional. For example, one can offer a comprehensive evaluation of a country’s development path, and decide that as part of this evaluation, one wants to include particular accounts of the history and culture of that country, since this may make more comprehensible the reasons why that country has taken this particular development path rather than another. The particular historical account that would be part of one’s capability theory would then be optional.16

Given this three-fold structure of the modular view of capability theories, let us now investigate what the content of the compulsory module A is, as well as what the options are within the B-modules and C-modules.

2.6 The A-module: the non-optional core of all capability theories

What, then, is the content of the A-module, which all capability theories should share? Table 2.2 presents the keywords for the eight elements of the A-module.

Table 2.2 The content of the compulsory module A

|

A1: Functionings and capabilities as core concepts A2: Functionings and capabilities are value-neutral categories A3: Conversion factors A4: The distinction between means and ends A5: Functionings and/or capabilities form the evaluative space A6: Other dimensions of ultimate value A7: Value pluralism A8: Valuing each person as an end |

2.6.1 A1: Functionings and capabilities

Functionings and capabilities are the core concepts in the capability approach. They are also the dimensions in which interpersonal comparisons of ‘advantage’ are made (this is what property A5 entails).17 They are the most important distinctive features of all capabilitarian theories. There are some differences in the usage of these notions between different capability theorists,18 but these differences do not affect the essence of these notions: capabilities are what people are able to be and to do, and functionings point to the corresponding achievements.

Capabilities are real freedoms or real opportunities, which do not refer to access to resources or opportunities for certain levels of satisfaction. Examples of ‘beings’ are being well-nourished, being undernourished, being sheltered and housed in a decent house, being educated, being illiterate, being part of a supportive social network; these also include very different beings such as being part of a criminal network and being depressed. Examples of the ‘doings’ are travelling, caring for a child, voting in an election, taking part in a debate, taking drugs, killing animals, eating animals, consuming great amounts of fuel in order to heat one’s house, and donating money to charity.

Capabilities are a person’s real freedoms or opportunities to achieve functionings.19 Thus, while travelling is a functioning, the real opportunity to travel is the corresponding capability. A person who does not travel may or may not be free and able to travel; the notion of capability seeks to capture precisely the fact of whether the person could travel if she wanted to. The distinction between functionings and capabilities is between the realized and the effectively possible, in other words, between achievements, on the one hand, and freedoms or opportunities from which one can choose, on the other.

Functionings are constitutive of human life. At least, this is a widespread view, certainly in the social sciences, policy studies, and in a significant part of philosophy — and I think it is a view that is helpful for the interdisciplinary, practical orientation that the vast majority of capability research has.20 That means one cannot be a human being without having at least a range of functionings; they make the lives of human beings both lives (as opposed to the existence of innate objects) and human (in contrast to the lives of trees or animals). Human functionings are those beings and doings that constitute human life and that are central to our understandings of ourselves as human beings. It is hard to think of any phenomenological account of the lives of humans — either an account given by a human being herself, or an account from a third-person perspective — which does not include a description of a range of human functionings. Yet, not all beings and doings are functionings; for example, flying like a bird or living for two hundred years like an oak tree are not human functionings.

In addition, some human beings or doings may not be constitutive but rather contingent upon our social institutions; these, arguably, should not qualify as ‘universal functionings’ — that is, functionings no matter the social circumstances in which one lives — but are rather ‘context-dependent functionings’, functionings that are to a significant extent dependent on the existing social structures. For example, ‘owning a house’ is not a universal functioning, yet ‘being sheltered in a safe way and protected from the elements’ is a universal functioning. One can also include the capability of being sheltered in government-funded housing or by a rental market for family houses, which is regulated in such a way that it does not endanger important aspects of that capability.

Note that many features of a person could be described either as a being or as a doing: we can say that a person is housed in a pleasantly warm dwelling, or that this person does consume lots of energy to keep her house warm. Yet other functionings are much more straightforwardly described as either a being or a doing, for example ‘being healthy’ (a being) or ‘killing animals’ (a doing).

A final remark. Acknowledging that functionings and capabilities are the core concepts of the capability approach generates some further conceptual questions, which have not all been sufficiently addressed in the literature. An important question is whether additional structural requirements that apply to the relations between various capabilities should be imposed on the capability approach in general (not merely as a particular choice for a specific capability theory). Relatively little work has been done on the question of the conceptual properties of capabilities understood as freedoms or opportunities and on the question of the minimum requirements of the opportunity set that make up these various capabilities. But it is clear that more needs to be said about which properties we want functionings, capabilities, and capability sets to meet. One important property has been pointed out by Kaushik Basu (1987), who argued that the moral relevance lies not in the various capabilities each taken by themselves and only considering the choices made by one person. Rather, the moral relevance lies in whether capabilities are truly available to us given the choices made by others, since that is the real freedom to live our lives in various ways, as it is truly open to us. For example, if a teenager lives in a family in which there are only enough resources for one of the children to pursue higher education, then he only truly has the capability to pursue higher education if none of his older siblings has made that choice before him.21

2.6.2 A2: Functionings and capabilities are value-neutral categories

Functionings and capabilities are defined in a value-neutral way. Many functionings are valuable, but not all functionings necessarily have a positive value. Instead, some functionings have no value or even have a negative value, e.g. the functioning of being affected by a painful, debilitating and ultimately incurable illness, suffering from excessive levels of stress, or engaging in acts of unjustifiable violence. In those latter cases, we are better off without that functionings outcome, and the functionings outcome has a negative value. Functionings are constitutive elements of human life, which consist of both wellbeing and ill-being. The notion of functionings should, therefore, be value-neutral in the sense that we should conceptually allow for the idea of ‘bad functionings’ or functionings with a negative value (Deneulin and Stewart 2002, 67; Nussbaum 2003a, 45; Stewart 2005, 190; Carter 2014, 79–81).

There are many beings and doings that have negative value, but they are still ‘a being’ or ‘a doing’ and, hence, a functioning. Nussbaum made that point forcefully when she argued that the capability to rape should not be a capability that we have reason to protect (Nussbaum 2003: 44–45). A country could effectively enable people to rape, for example, either when rape is not illegal (as it is not between husband and wife in many countries), or when rape is illegal, but de facto never leads to any punishment of the aggressor. If there is a set of social norms justifying rape, and would-be rapists help each other to be able to rape, then would-be rapists in that country effectively enjoy the capability to rape. But clearly, rape is a moral bad, and a huge harm to its victims; it is thus not a capability that a country should want to protect. This example illustrates that functionings as well as capabilities can be harmful or have a negative value, as well as be positive or valuable. At an abstract and general level, ‘functionings’ and ‘capabilities’ are thus in themselves neutral concepts, and hence we cannot escape the imperative to decide which ones we want to support and enable, and which ones we want to fight or eliminate. Frances Stewart and Séverine Deneulin (2002, 67) put it as follows:

[…] some capabilities have negative values (e.g. committing murder), while others may be trivial (riding a one-wheeled bicycle). Hence there is a need to differentiate between ‘valuable’ and non-valuable capabilities, and indeed, within the latter, between those that are positive but of lesser importance and those that actually have negative value.

The above examples show that some functionings can be unequivocally good (e.g. being in good health) or unequivocally bad (e.g. being raped or being murdered). In those cases, there will be unanimity on whether the functionings outcome is bad or good. But now we need to add a layer of complexity. Sometimes, it will be a matter of doubt, or of dispute, whether a functioning will be good or bad — or the goodness or badness may depend on the context and/or the normative theory we endorse. An interesting example is giving care, or ‘care work’.22 Clearly being able to care for someone could be considered a valuable capability. For example, in the case of child care, there is much joy to be gained, and many parents would like to work less so as to spend more time with their children. But care work has a very ambiguous character if we try to answer whether it should be considered to be a valuable functioning from the perspective of the person who does the care. Lots of care is performed primarily because there is familial or social pressure put on someone (generally women) to do so, or because no-one else is doing it (Lewis and Giullari 2005). There is also the hypothesis that care work can be a positive functioning if done for a limited amount of time, but becomes a negative functioning if it is done for many hours. Hence, from the functionings outcome in itself, we cannot conclude whether this is a positive element of that person’s quality of life, or rather a negative element; in fact, sometimes it will be an ambiguous situation, which cannot easily be judged (Robeyns 2003).

One could wonder, though, whether this ambiguity cannot simply be resolved by reformulating the corresponding capability slightly differently. In theory, this may be true. If there are no empirical constraints related to the observations we can make, then one could in many cases rephrase such functionings that are ambiguously valued into another capability where its valuation is clearly positive. For example, one could say that the functioning of providing care in itself can be ambiguous (since some people do too much, thereby harming their own longer-term wellbeing, or do it because no-one else is providing the care and social norms require them to do it). Yet there is a closely related capability that is clearly valuable: the capability to provide hands-on care, which takes into account that one has a robust choice not to care if one does not want to, and that one does not find oneself in a situation in which the care is of insufficient quantity and/or quality if one does not deliver the care oneself. If such a robust capability to care is available, it would be genuinely valuable, since one would have a real option not to choose the functioning without paying an unacceptable price (e.g. that the person in need of care is not properly cared for). However, the problem with this solution, of reformulating functionings that are ambiguously valuable into capabilities that are unequivocally valuable, is the constraints it places on empirical information. We may be able to use these layers of filters and conditions in first-person analyses, or in ethnographic analyses, but in most cases not in large-scale empirical analyses.

Many specific capability theories make the mistake of defining functionings as those beings and doings that one has reason to value. But the problem with this value-laden definition is that it collapses two aspects of the development of a capability theory into one: the definition of the relevant space (e.g. income, or happiness, or functionings) and, once we have chosen our functionings and capabilities, the normative decision regarding which of those capabilities will be the focus of our theory. We may agree on the first issue and not on the second and still both rightly believe that we endorse a capability theory — yet this is only possible if we analytically separate the normative choice for functionings and capabilities from the additional normative decision of which functionings we will regard as valuable and which we will not regard as valuable. Collapsing these two normative moments into one is not a good idea; instead, we need to acknowledge that there are two normative moves being made when we use functionings and capabilities as our evaluative space, and we need to justify each of those two normative moves separately.

Note that the value-laden definition of functionings and capabilities, which defines them as always good and valuable, may be less problematic when one develops a capability theory of severe poverty or destitution. We all agree that poor health, poor housing, poor sanitation, poor nutrition and social exclusion are dimensions of destitution. So, for example, the dimensions chosen for the Multidimensional Poverty Index developed by Sabina Alkire and her colleagues — health, education and living standard — may not elicit much disagreement.23 But for many other capability theories, it is disputed whether a particular functionings outcome is valuable or not. The entire field of applied ethics is filled with questions and cases in which these disputes are debated. Is sex work bad for adult sex workers, or should it be seen as a valuable capability? Is the capability of parents not to vaccinate their children against polio or measles a valuable freedom? If employees in highly competitive organisations are not allowed to read their emails after working hours, is that then a valuable capability that is taken away from them, or are we protecting them from becoming workaholics and protecting them from the pressure to work all the time, including at evenings and weekends? As these examples show, we need to allow for the conceptual possibility that there are functionings that are always valuable, never valuable, valuable or non-valuable in some contexts but not in others, or where we simply are not sure. This requires that functionings and capabilities are conceptualised in a value-neutral way, and hence this should be a core requirement of the capability approach.

2.6.3 A3: Conversion factors

A third core idea of the capability approach is that persons have different abilities to convert resources into functionings. These are called conversion factors: the factors which determine the degree to which a person can transform a resource into a functioning. This has been an important idea in Amartya Sen’s version of the capability approach (Sen 1992a, 19–21, 26–30, 37–38) and for those scholars influenced by his writings. Resources, such as marketable goods and services, but also goods and services emerging from the non-market economy (including household production) have certain characteristics that make them of interest to people. In Sen’s work in welfare economics, the notion of ‘resources’ was limited to material and/or measurable resources (in particular: money or consumer goods) but one could also apply the notion of conversion factors to a broader understanding of resources, including, for example, the educational degrees that one has.

The example of a bike is often used to illustrate the idea of conversion factors. We are interested in a bike not primarily because it is an object made from certain materials with a specific shape and colour, but because it can take us to places where we want to go, and in a faster way than if we were walking. These characteristics of a good or commodity enable or contribute to a functioning. A bike enables the functioning of mobility, to be able to move oneself freely and more rapidly than walking. But a person might be able to turn that resource into a valuable functioning to a different degree than other persons, depending on the relevant conversion factors. For example, an able-bodied person who was taught to ride a bicycle when he was a child has a high conversion factor enabling him to turn the bicycle into the ability to move around efficiently, whereas a person with a physical impairment or someone who never learnt to ride a bike has a very low conversion factor. The conversion factors thus represent how much functioning one can get out of a resource; in our example, how much mobility the person can get out of a bicycle.

There are several different types of conversion factors, and the conversion factors discussed are often categorized into three groups (Robeyns 2005b, 99; Crocker and Robeyns 2009, 68). All conversion factors influence how a person can be or is free to convert the characteristics of the resources into a functioning, yet the sources of these factors may differ. Personal conversion factors are internal to the person, such as metabolism, physical condition, sex, reading skills, or intelligence. If a person is disabled, or if she is in a bad physical condition, or has never learned to cycle, then the bike will be of limited help in enabling the functioning of mobility. Social conversion factors are factors stemming from the society in which one lives, such as public policies, social norms, practices that unfairly discriminate, societal hierarchies, or power relations related to class, gender, race, or caste. Environmental conversion factors emerge from the physical or built environment in which a person lives. Among aspects of one’s geographical location are climate, pollution, the likelihood of earthquakes, and the presence or absence of seas and oceans. Among aspects of the built environment are the stability of buildings, roads, and bridges, and the means of transportation and communication. Take again the example of the bicycle. How much a bicycle contributes to a person’s mobility depends on that person’s physical condition (a personal conversion factor), the social mores including whether women are generally allowed to ride a bicycle (a social conversion factor), and the availability of decent roads or bike paths (an environmental conversion factor). Once we start to be aware of the existence of conversion factors, it becomes clear that they are a very pervasive phenomenon. For example, a pregnant or lactating woman needs more of the same food than another woman in order to be well-nourished. Or people living in delta regions need protection from flooding if they want to enjoy the same capability of being safely sheltered as people living in the mountains. There are an infinite number of other examples illustrating the importance of conversion factors. The three types of conversion factor all push us to acknowledge that it is not sufficient to know the resources a person owns or can use in order to be able to assess the wellbeing that he or she has achieved or could achieve; rather, we need to know much more about the person and the circumstances in which he or she is living. Differences in conversion factors are one important source of human diversity, which is a central concern in the capability approach, and will be discussed in more detail in section 3.5.

Note that many conversion factors are not fixed or given, but can be altered by policies and choices that we make. And the effects of a particular conversion factor can also depend on the social and personal resources that a person has, as well as on the other conversion factors. For example, having a physical impairment that doesn’t allow one to walk severely restricts one’s capability to be mobile if one finds oneself in a situation in which one doesn’t have access to a wheelchair, and in which the state of the roads is bad and vehicles used for public transport are not wheelchair-accessible. But suppose now the built environment is different: all walking-impaired people have a right to a wheelchair, roads are wheelchair-friendly, public transport is wheelchair-accessible and society is characterised by a set of social norms whereby people consider it nothing but self-evident to provide help to fellow travellers who can’t walk. In such an alternative social state, with a different set of resources and social and environmental conversion factors, the same personal conversion factor (not being able to walk) plays out very differently. In sum, in order to know what people are able to do and be, we need to analyse the full picture of their resources, and the various conversion factors, or else analyse the functionings and capabilities directly. The advantage of having a clear picture of the resources needed, and the particular conversion factors needed, is that it also gives those aiming to expand capability sets information on where interventions can be made.

2.6.4 A4: The means-ends distinction

The fourth core characteristic of the capability approach is the means-ends distinction. The approach stresses that we should always be clear, when valuing something, whether we value it as an end in itself, or as a means to a valuable end. For the capability approach, when considering interpersonal comparisons of advantage, the ultimate ends are people’s valuable capabilities (there could be other ends as well; see 2.6.6). This implies that the capability approach requires us to evaluate policies and other changes according to their impact on people’s capabilities as well as their actual functionings; yet at the same time we need to ask whether the preconditions — the means and the enabling circumstances — for those capabilities are in place. We must ask whether people are able to be healthy, and whether the means or resources necessary for this capability, such as clean water, adequate sanitation, access to doctors, protection from infections and diseases and basic knowledge on health issues are present. We must ask whether people are well-nourished, and whether the means or conditions for the realization of this capability, such as having sufficient food supplies and food entitlements, are being met. We must ask whether people have access to a high-quality education system, to real political participation, and to community activities that support them, that enable them to cope with struggles in daily life, and that foster caring friendships. Hence we do need to take the means into account, but we can only do so if we first know what the ends are.

Many of the arguments that capability theorists have advanced against alternative normative frameworks can be traced back to the objection that alternative approaches focus on particular means to wellbeing rather than the ends.24 There are two important reasons why the capability approach dictates that we have to start our analysis from the ends rather than the means. Firstly, people differ in their ability to convert means into valuable opportunities (capabilities) or outcomes (functionings) (Sen 1992a, 26–28, 36–38). Since ends are what ultimately matter when thinking about wellbeing and the quality of life, means can only work as fully reliable proxies of people’s opportunities to achieve those ends if all people have the same capacities or powers to convert those means into equal capability sets. This is an assumption that goes against a core characteristic of the capability approach, namely claim A3 — the inter-individual differences in the conversion of resources into functionings and capabilities. Capability scholars believe that these inter-individual differences are far-reaching and significant, and hence this also explains why the idea of conversion factors is a compulsory option in the capability approach (see 2.6.3). Theories that focus on means run the risk of downplaying the normative relevance of not only these conversion factors, but also the differences in structural constraints that people face (see 2.7.5).

The second reason why the capability approach requires us to start from ends rather than means is that there are some vitally important ends that do not depend very much on material means, and hence would not be picked up in our analysis if we were to focus on means only. For example, self-respect, supportive relationships in school or in the workplace, or friendship are all very important ends that people may want; yet there are no crucial means to those ends that one could use as a readily measurable proxy. We need to focus on ends directly if we want to capture what is important.

One could argue, however, that the capability approach does not focus entirely on ends, but rather on the question of whether a person is being put in the conditions in which she can pursue her ultimate ends. For example, being able to read could be seen as a means rather than an end in itself, since people’s ultimate ends will be more specific, such as reading street signs, the newspaper, or the Bible or Koran. It is therefore somewhat more precise to say that the capability approach focuses on people’s ends in terms of beings and doings expressed in general terms: being literate, being mobile, being able to hold a decent job. Whether a particular person then decides to translate these general capabilities into the more specific capabilities A, B or C (e.g. reading street signs, reading the newspaper or reading the Bible) is up to them. Whether that person decides to stay put, travel to the US or rather to China, is in principle not important for a capability analysis: the question is rather whether a person has these capabilities in more general terms.25 Another way of framing this is to say that the end of policy making and institutional design is to provide people with general capabilities, whereas the ends of persons are more specific capabilities.26

Of course, the normative focus on ends does not imply that the capability approach does not at all value means such as material or financial resources. Instead, a capability analysis will typically focus on resources and other means. For example, in their evaluation of development in India, Jean Drèze and Amartya Sen (2002, 3) have stressed that working within the capability approach in no way excludes the integration of an analysis of resources such as food. In sum, all the means of wellbeing, like the availability of commodities, legal entitlements to them, other social institutions, and so forth, are important, but the capability approach presses the point that they are not the ends of wellbeing, only their means. Food may be abundant in the village, but a starving person may have nothing to exchange for it, no legal claim on it, or no way of preventing intestinal parasites from consuming it before he or she does. In all these cases, at least some resources will be available, but that person will remain hungry and, after a while, undernourished.27

Nevertheless, one could wonder: wouldn’t it be better to focus on means only, rather than making the normative analysis more complicated and more informationally demanding by also focusing on functionings and capabilities? Capability scholars would respond that starting a normative analysis from the ends rather than means has at least two advantages, in addition to the fundamental reason mentioned earlier that a focus on ends is needed to appropriately capture inter-individual differences.

First, if we start from being explicit about our ends, the valuation of means will retain the status of an instrumental valuation rather than risk taking on the nature of a valuation of ends. For example, money or economic growth will not be valued for their own sake, but only in so far as they contribute to an expansion of people’s capabilities. For those who have been working within the capability framework, this has become a deeply ingrained practice — but one only needs to read the newspapers for a few days to see how often policies are justified or discussed without a clear distinction being made between means and ends.

Second, by starting from ends, we do not a priori assume that there is only one overriding important means to those ends (such as income), but rather explicitly ask the question: which types of means are important for the fostering and nurturing of a particular capability, or set of capabilities? For some capabilities, the most important means will indeed be financial resources and economic production, but for others it may be a change in political practices and institutions, such as effective guarantees and protections of freedom of thought, political participation, social or cultural practices, social structures, social institutions, public goods, social norms, and traditions and habits. As a consequence, an effective capability-enhancing policy may not be increasing disposable income, but rather fighting a homophobic, ethnophobic, racist or sexist social climate.

2.6.5 A5: Functionings and capabilities as the evaluative space

If a capability theory is a normative theory (as is often the case), then functionings and capabilities form the entire evaluative space, or are part of the evaluative space.28 A normative theory is a theory that entails a value judgement: something is better than or worse than something else. This value judgement can be used to compare the position of different persons or states of affairs (as in inequality analysis) or it can be used to judge one course of action as ‘better’ than another course of action (as in policy design). For all these types of normative theories, we need normative claims, since concepts alone cannot ground normativity.

The first normative claim which each capability theory should respect is thus that functionings and capabilities form the ‘evaluative space’. According to the capability approach, the ends of wellbeing freedom, justice, and development should be conceptualized in terms of people’s functionings and/or capabilities. This claim is not contested among scholars of the capability approach; for example, Sabina Alkire (2005, 122) described the capability approach as the proposition “that social arrangements should be evaluated according to the extent of freedom people have to promote or achieve functionings they value”. However, if we fully take into account that functionings can be positive but also negative (see 2.6.2), we should also acknowledge that our lives are better if they contain fewer of the functionings that are negative, such as physical violence or stress. Alkire’s proposition should therefore minimally be extended by adding “and to promote the weakening of those functionings that have a negative value”.29

However, what is relevant is not only which opportunities are open to us individually, hence in a piecemeal way, but rather which combinations or sets of potential functionings are open to us. For example, suppose you are a low-skilled poor single parent who lives in a society without decent social provisions. Take the following functionings: (1) to hold a job, which will require you to spend many hours on working and commuting, but will generate the income needed to properly feed yourself and your family; (2) to care for your children at home and give them all the attention, care and supervision they need. In a piecemeal analysis, both (1) and (2) are opportunities open to that parent, but they are not both together open to her. The point about the capability approach is precisely that it is comprehensive; we must ask which sets of capabilities are open to us, that is: can you simultaneously provide for your family and properly care for and supervise your children? Or are you rather forced to make some hard, perhaps even tragic choices between two functionings which are both central and valuable?

Note that while most types of capability analysis require interpersonal comparisons, one could also use the capability approach to evaluate the wellbeing or wellbeing freedom of one person at one point in time (e.g. evaluate her situation against a capability yardstick) or to evaluate the changes in her wellbeing or wellbeing freedom over time. The capability approach could thus also be used by a single person in her deliberate decision-making or evaluation processes, but these uses of the capability approach are much less prevalent in the scholarly literature. Yet all these normative exercises share the property that they use functionings and capabilities as the evaluative space — the space in which personal evaluations or interpersonal comparisons are made.

2.6.6 A6: Other dimensions of ultimate value

However, this brings us straight to another core property of module A, namely that functionings and/or capabilities are not necessarily the only elements of ultimate value. Capabilitarian theories might endorse functionings and/or capabilities as their account of ultimate value but may add other elements of ultimate value, such as procedural fairness. Other factors may also matter normatively, and in most capability theories these other principles or objects of evaluation will play a role. This implies that the capability approach is, in itself, incomplete as an account of the good since it may have to be supplemented with other values or principles.30 Sen has been a strong defender of this claim, for example, in his argument that capabilities capture the opportunity aspect of freedom but not the process aspect of freedom, which is also important (e.g. Sen 2002a, 583–622).31

At this point, it may be useful to reflect on a suggestion made by Henry Richardson (2015) to drop the use of the word ‘intrinsic’ when describing the value of functionings and capabilities — as is often done in the capability literature. For non-philosophers, saying that something has ‘intrinsic value’ is a way to say that something is much more important than something else, or it is used to say that we don’t need to investigate what the effects of this object are on another object. If we think that something doesn’t have intrinsic value, we would hold that it is desirable if it expands functionings and capabilities; economic growth is a prominent example in both the capability literature and in the human development literature. Yet in philosophy, there is a long-standing debate about what it means to say of something that it has intrinsic value, and it has increasingly been contested that it is helpful to speak of ‘intrinsic values’ given what philosophers generally would like to say when they use that word (Kagan 1998; Rabinowicz and Rønnow-Rasmussen 2000).

In philosophy, the term ‘intrinsic’ refers to a metaphysical claim; something we claim to be intrinsically valuable only derives its value from some internal properties. Yet in the capability approach, this is not really what we want to say about functionings (or capabilities). Rather, as Richardson rightly argues, we should be thinking about what we take to be worth seeking for its own sake. Richardson prefers to call this ‘thinking in terms of final ends’; in addition, one could also use the terminology ‘that which has ultimate value’ (see also Rabinowicz and Rønnow-Rasmussen 2000, 48).32 This has the advantage that we do not need to drop the widely used, and in my view very useful, distinction between instrumental value and ultimate value. Those things that have ultimate value are the things we seek because they are an end (of policy making, decision making, evaluations); those things that do not have ultimate value, hence that are not ends, will be valued to the extent that they have instrumental value for those ends.

Of course, non-philosophers may object and argue they are using ‘intrinsic value’ and ‘ultimate value’ as synonyms. But if we want to develop the capability approach in a way that draws on the insights from all disciplines, we should try to accommodate this insight from philosophy into the interdisciplinary language of the capability approach, especially if there is a very easy-to-use alternative available to us. We can either, as Richardson proposes, speak of the selected functionings and capabilities as final ends, or we can say that the selected functionings and capabilities have ultimate value — that is, they have value as ends in themselves and not because they are useful for some further end. It is of course possible for a capability to have ultimate value and for the corresponding functioning to have instrumental value. For example, being knowledgeable and educated can very plausibly be seen as of ultimate value, but is also of instrumental value for various other capabilities, such as the capability of being healthy, being able to pursue projects, being able to hold a job, and so forth.

However, the question is whether it is possible to change the use of a term that is so widespread in some disciplines yet regarded as wrong from the point of view of another discipline. It may be that the best we can hope for is to become aware of the different usages of the term ‘intrinsic value’, which in the social sciences is used in a much looser way than in philosophy, and doesn’t have the metaphysical implications that philosophers attribute to it.

2.6.7 A7: Value pluralism

There are at least two types of value pluralism within the capability approach. One type is the other objects of ultimate value, which was briefly addressed in the previous section. This is what Sen called in his Dewey lectures principle pluralism (Sen 1985c, 176). Expanding capabilities and functionings is not all that matters; there are other moral principles and goals with ultimate value that are also important when evaluating social states, or when deciding what we ought to do (whether as individuals or policy makers). Examples are deontic norms and principles that apply to the processes that lead to the expansion of capability sets. This value pluralism plays a very important role in understanding the need to have the C-module C4, which will be discussed in section 2.8.4.

It is interesting to note that at some stage in Sen’s development of the capability approach, his readers lost this principle-pluralism and thought that the capability approach could stand on its own. But a reading of Sen’s earlier work on the capability approach shows that all along, Sen felt that capabilities can and need to be supplemented with other principles and values. For example, in his 1982 article ‘Rights and Agency’, Sen argues that “goal rights, including capability rights, and other goals, can be combined with deontological values […], along with other agent-relative considerations, in an integrated system” (Sen 1982, 4). Luckily, the more recent publications in the secondary literature on the capability approach increasingly acknowledge this principle pluralism; the modules A7 and C4 of the modular view presented in this book suggest that it is no longer possible not to acknowledge this possibility.

The second type of value-pluralism relates to what is often called the multidimensional nature of the capability approach. Functionings and capabilities are not ‘values’ in the sense of ‘public values’ (justice, efficiency, solidarity, ecological sustainability, etc.) but they are objects of ultimate value — things that we value as ends in themselves. Given some very minimal assumptions about human nature, it is obvious that these dimensions are multiple: human beings value the opportunity to be in good health, to engage in social interactions, to have meaningful activities, to be sheltered and safe, not be subjected to excessive levels of stress, and so forth. Of course, it is logically conceivable to say that for a particular normative exercise, we only look at one dimension. But while it may be consistent and logical, it nevertheless makes no sense — for at least two reasons.

First, the very reason why the capability approach has been offered as an alternative to other normative approaches is to add informational riches — to show which dimensions have been left out of the other types of analysis, and why adding them matters. It also makes many evaluations much more nuanced, allowing them to reflect the complexities of life as it is. For example, an African-American lawyer may be successful in her professional life in terms of her professional achievements and the material rewards she receives for her work, but she may also encounter disrespect and humiliation in a society that is sexist and racist. Being materially well-off doesn’t mean that one is living a life with all the capabilities to which one should be entitled in a just society. Only multi-dimensional metrics of evaluation can capture those ambiguities and informational riches.

Second, without value pluralism, it would follow that the happiness approach is a special case of the capability approach — namely a capability theory in which only one functioning matters, namely being happy. Again, while this is strictly speaking a consistent and logical possibility, it makes no sense given that the capability approach was conceived to form an alternative to both the income metric and other resourcist approaches on the one hand, and the happiness approach and other mental metric approaches on the other. Thus, in order to make the capability approach a genuine alternative to other approaches, we need to acknowledge several functionings and capabilities, rather than just one.

2.6.8 A8: The principle of each person as an end

A final core property of each capability theory or application is that each person counts as a moral equal. Martha Nussbaum calls this principle “the principle of each person as an end”. Throughout her work she has offered strong arguments in defence of this principle (Nussbaum 2000, 56):

The account we strive for [i.e. the capability approach] should preserve liberties and opportunities for each and every person, taken one by one, respecting each of them as an end, rather than simply as the agent or supporter of the ends of others. […] We need only notice that there is a type of focus on the individual person as such that requires no particular metaphysical position, and no bias against love or care. It arises naturally from the recognition that each person has just one life to live, not more than one. […] If we combine this observation with the thought […] that each person is valuable and worthy of respect as an end, we must conclude that we should look not just to the total or the average, but to the functioning of each and every person.

Nussbaum’s principle of each person as an end is the same as what is also known as ethical or normative individualism in debates in philosophy of science. Ethical individualism, or normative individualism, makes a claim about who or what should count in our evaluative exercises and decisions. It postulates that individual persons, and only individual persons are the units of ultimate moral concern. In other words, when evaluating different social arrangements, we are only interested in the (direct and indirect) effects of those arrangements on individuals.