2. Dancing for God

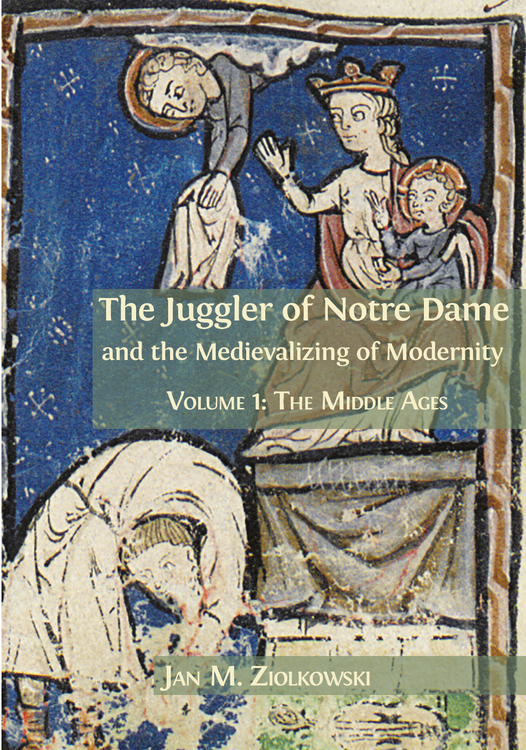

© 2018 Jan M. Ziolkowski, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0132.02

I would only believe in a God that knew how to dance. […] Now a God dances in me.

To make sense of Our Lady’s Tumbler, we must transport ourselves to the Middle Ages. We have delved into the manuscripts, and we have begun to come to terms with the texts and the single image that they transmit. For all that, we have not advanced very far in decoding what the narrative portends. The words are never mere words. They constitute our best guides to the meanings that individual writers, their communities, and, even more broadly, their societies hoped to relay across the chasms of time and space to others—including, now, us. All the same, the verbalism is, at the risk of appearing flippant, only part of the story. To wrest the richest and deepest significance from the tale, we will be obligated to go beyond the strictly and solely lexical level. Through the lexicon and subject matter, we may identify and reconstruct discourses. In the poem and exemplum, we need to uncouple the conceptual framework of the entertainer from that of the monk. The two are overlaid, like electrochemical cells in a battery or conductors in a capacitor, to create the extraordinary electricity that the lay brother and jongleur in this tale discharges.

The Tumbler

Scribes in the Middle Ages manifested nearly the same indifference to transmitting exact titles as they did to pinning down exact authorship. The names of medieval texts were often not authorial, but concocted by scribes or readers. Thus, the manuscripts of Our Lady’s Tumbler divulge no consensus as to the original title, if one even existed. To the contrary, they identify the poem in five different ways. Each codex, to judge by the captions for our poem, tells a different story:

This Is about the Tumbler of Our Lady

The Tale of the Jongleur

Of a Minstrel Who Became a Monk to Whom Our Lady Showed Grace

Of a Minstrel Who Served Our Lady by His Own Craft.

The common element in all these combinations is a term for a professional entertainer, whether tumbler, jongleur, or minstrel. But exactly what sort of performer? Even more to the point, what manner of tale should we have in mind? Finally, what type of association with the Virgin should we envisage the protagonist having? After all, she is mentioned in four of the titles. Research is detective work. Let us become gumshoes ourselves, on a manhunt to understand the character who dies at the end of our story. In our medieval film noir, the blackness is the ink on folios of parchment.

Various factors would have made advantageous a shift from a tumbler into a jongleur. The latter is usually lowlier in social status than the troubadour, but the two nonetheless share resemblances. One is that both could be instrumental musicians, singers, or both. Another is that both have an interesting connection with passion for women. The troubadour belongs to the system of courtly love, in which the beloved and unattainable lady is idolized. The jongleur here, at his most pious, is presented as a humble but sincere worshiper of the Virgin, who is embodied in a Madonna. He does everything, and gives his all, for the love of Mary alone. In the titles that four of the five manuscripts offer, this character is associated with the Mother of God. In other words, he too is a fool for love, but his inamorata is Mary. He dances attendance upon her and upon no one else.

The most literal-minded transposition of the prevailing medieval title into present-day French would be Le tombeur de Notre Dame, word-for-word “The Tumbler of Our Lady.” The hitch with retaining this wording unmodified in the modern tongue lies in the element tombeur. While the verb tomber means “to fall,” for more than a century the derivative noun has come to connote in French not a tumbler, in the sense of acrobat, dancer, or acrobatic dancer, but rather a lady’s man, ladykiller, womanizer, cad, or bounder, for whom incautious women may fall, sometimes much to their subsequent remorse. Although the term is by no means an obscenity, and no one would be foulmouthed in using it, it carries a charge of moral disapproval and condemnation. Imagine if every time English speakers employed the word tumble, their thoughts turned to sexual intercourse, because of the euphemistic “a tumble in the hay.” Under such circumstances, they might shun the noun tumbler, which is the predicament that tombeur thrusts upon French-speakers today. The medieval verb is another matter, since it carried no such associations.

The discomfort about transposing the original term from medieval French into the modern language can be inferred from a heading in a 1912 volume of French literary history. The caption leading into discussion of the medieval poem reads “Le Tombeur (Jongleur) de Notre-Dame,” and the following sentence glosses the word in question as “a tumbler or performer of tumbles.” To bat away objectionable associations of tombeur that ill befit a spiritual tale, the closest and otherwise most natural modern rendering of the thirteenth-century French has been unloaded in favor of Le jongleur de Notre Dame. The present-day title can be and has been rendered into English as The Jongleur of Notre Dame in the hybrid of the two languages that has been styled Frenglish. In this case, key noun is a loanword that can mean generally minstrel or particularly juggler.

The situation in French hastened conflation of the medieval story with its fin-de-siècle adaptations by the Nobel Prize-winning author Anatole France and the once supremely successful songwriter Jules Massenet. We need not bid them au revoir, since we will encounter them again repeatedly. Their short story and opera, respectively, carry the title Le jongleur de Notre Dame. Thus, in French both sides of the narrative equation, medieval and medievalized, are known unvaryingly as Le jongleur de Notre Dame. In contrast, in English, despite occasional contamination across the divide, the medieval tale tends to be called Our Lady’s Tumbler, whereas the texts by the above short-story writer and musician are designated by the half-Anglicized title of Jongleur of Notre Dame. Modern authors have contrived myriad ways of ringing changes, mostly slight but some radical, upon each of these captions.

Notre Dame versus Saint Mary

At first blush, the other panel in the diptych-like title looks problem-free. No troubleshooting would appear to be called for. When used as a possessive, the medieval French Nostre Dame morphed into the modern de Notre Dame. Yet this other phrase too requires at least a little examination. Notre Dame designates the Virgin in her capacity as “Our Lady.” Even more often, it serves as shorthand for a religious foundation dedicated to her, with the cathedral of Paris being by far the best known. The more relevant matter is what led to the formulation Notre Dame in the first place. Despite its familiarity, it should not be taken for granted. French is unusual in calling Mary what it does, in having as many dedications of places, buildings, and institutions to her as it does, and in vaunting a cathedral named after her that has become emblematic of both Gothic architecture overall and particularly the city of Paris. Let us take a gander at all these aspects of the one seemingly simple phrase.

The designation of the Virgin as “Our Lady,” from the Latin domina nostra, has hardly been universal in the Romance languages. Calling her Saint Mary was, and perhaps still is, more common (see Fig. 2.1). To take one well-known nautical example, Christopher Columbus’s largest ship was not christened Nuestra Señora, Spanish for Our Lady. On the contrary, it was the Santa Maria—Saint Mary if translated into English. In French, usage has differed markedly—and the divergence from most other languages began early. Notre Dame may well have become current already in the eleventh century. To all appearances, the phraseology took strong hold first at Chartres in the second half of the twelfth century. From there, it seeped by linguistic drip-drip into other forms of Romance speech, such as Occitan and Catalan, at the expense of the formulations for “Saint Mary” in these tongues.

Fig. 2.1 Edward Maran, The “Santa Maria,” 1492, 1892. Painting, reproduced on color print from original The Santa Maria, Niña and Pinta (Evening of October 11, 1492).

No one knows what bright soul coined the locution Notre Dame. (Nobody filed for exclusive rights to it.) The turn of phrase may have arisen among the laity rather than among ecclesiastics, as a means of marking the Virgin apart from other saints, including virgins, to accord her special credit for her uniqueness. By not being labeled “saint” she is elevated, not to the point of heading a matriarchy, but still head and shoulders above all others. The discrimination makes perfect sense, since she occupies a degree below that of Jesus Christ but above ordinary saints. At the same time, Mary was the most popular, in the fullest sense of the word, of holy women. Yet Notre Dame differs interestingly from, for instance, the Italian Madonna, which could be equated to “my lady” or “milady.” We may not stop to puzzle over why we say “your Majesty” as opposed to “my Lord,” but the possessive adjectives have been driven by specific forces. The plural in the French first-person possessive for “Our Lady” brought home that she belonged to everyone. The form “Our” may well reflect liturgical practices, in which the members of a church collectively invoke the Mother of God. The noun Dame had the simultaneous effect of coordinating the Virgin with feudalism. In French, Jesus Christ is Notre Seigneur, or “Our Lord.” By being called “Our Lady,” Mary is recognized in rank for being what she was, that is, the most powerful female in Christianity. In medieval society, women were ringed around by constraints, but the Mother of God knew no limitations: she had to shatter no stained-glass ceiling. Making her into a lady had the self-contradictory, but understandable effects of simultaneously ennobling, familiarizing, and humanizing her. As obligatory within the feudal system, the Virgin would indemnify her devotee as a lady would shield a vassal against all threats and arm-twisting.

The upswing in the wording Notre Dame took place within a much larger swing, namely, the cult of Mary. This veneration began to proliferate in the eleventh century, and in the twelfth century reached in both lay and clerical piety a pinnacle from which it would not be dislodged for the rest of the Middle Ages. The high point turned out to be a mesa-like plateau. Devotion to the Virgin must be reckoned among the most instrumental forces in spiritual life and creative achievement from the twelfth through the fifteenth centuries. There is no hyperbolizing the number of sculptures, paintings, stained-glass windows, and other artworks created in honor of Mary, and no overstating the volume of hymns and stories composed on her behalf. This literary flowering coincided with the efflorescence of courtly love literature, in which the lady occupied an exalted place. The two developments would have supported each other, and would have initiated many-sided interplay.

The Mother of God as elevated through mass devotion was manifold. At first the Virgin won favor through her relation to Christ. She enabled the Word to become flesh when she accepted her role in the Incarnation, as the human mother from whom the Son of God took his humanity. In her own humanness, she was later the grieving Mary. In this guise, she would become formalized as the Mater Dolorosa, or “Sorrowful Mother.” Even more particularly, her griefs would be numbered seven. In this connection, we should not overlook the parallels between the maternal Virgin as she keens over the deposed Christ, and the Mary who assuages the jongleur after he collapses before the Madonna. Eventually, the Mother of God won a clean sweep through her Assumption into heaven, which positioned her first for coronation and then for being seated on the right side of Jesus as the Virgin and Child in majesty.

On a civic plane, Mary constituted a favored last-line defense for municipalities, in the first instance Constantinople. She earned this reputation after the siege of the Byzantine capital by Persians and Avars in 626. A progression becomes clear: she acquired status as the invincible defender and invulnerable protector of, first, the city, then the whole Eastern Roman Empire, and ultimately all Christendom. Despite having a power quotient that bordered on omnipotence, the Mother of God was not preempted from transitioning to being a merciful mediator. In her maternal capacity, she acted as a vigilant lookout for the best interests of humanity. As the Virgin of Mercy, she went from merely being Mother Confessor to playing an active role in motivating her son to absolve repentant sinners. Beyond the Marys in all these capacities burgeoned a multiplicity of other Virgins, including Madonnas that triggered local affection and devotion while generating miracles. In popular devotion, such images served as the focal points for personal and affective language that invoked the Mother of God as intercessor. In exchange for the worship, the Virgin traveled to and fro between heaven and earth with a facility disallowed to Jesus himself. She was especially approachable, and uniquely capable of working miracles. All these Marys traveled with a long train of miracle stories, sermons, popular literature, art works, and shrines.

In modern French, Notre Dame has come to denote without distinction the Virgin Mary herself and a cathedral, since almost all such foundations in France are dedicated to her. After the bombing of Reims in World War I, an author spouted about the synecdoche with patriotic wholeheartedness:

When we speak indifferently of “the Cathedral” or of “Notre-Dame” we do not confound the Palace with the Queen; we affirm that the Palace is the Queen’s, and that she is at home there; we mean to say that the Cathedral is her domain, her sanctuary, that one cannot separate the one from the other, that to touch the Cathedral is to touch Our Lady, and to violate the Cathedral is to violate Our Lady.

What rendered Mary exceptional, and why was she worshiped so warm-bloodedly by so many? The special saving grace of Christianity was that the religion made monotheism approachable by incorporating a man within its divinity. For all that, in time the godhead became regarded as aloof and forbidding to the rank and file. At the top of the social hierarchy, emperors and kings were God’s anointed. In that capacity, they had a privileged relation to Jesus. In Christian iconography of the East, we find Christ Pantokrator. In Greek, the epithet means “almighty.” In the corresponding imagery of the West, we encounter Christ in Majesty, enthroned as ruler of the world. In contrast to God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit, the Mother of God seemed within reach to everyone, no matter how humble. The reforms of the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 suggest that by then she was sought after more than ever to intercede with her offspring. One explanation was that the Church was not equipped to deliver the level of pastoral care demanded for the swelling numbers of needy Christians. Filling the gap, the Blessed Virgin could be counted upon to sway Jesus through her maternal influence. The underlying guideline was the common reality of life that a solicitous son can be prevailed upon to do anything for his mother. Thus, Mary assumed an unexcelled place within personal piety from which she shows no signs of being budged even today.

The Equivocal Status of Jongleurs

Not all those who wander are lost.

It is high time to read beyond the title and to think about the protean character to whom it refers in its first part. In French as in English, jongleur can now designate performers of innumerable different complexions. It behooved the practitioners of this profession to wear many hats. In their versatility, they diverted their audiences, both lay and ecclesiastical, with displays of verbal, musical, and physical skill. Even a very approximate taxonomy of these entertainers ramifies into a many-branched family tree. As artists of the word, they composed, ad-libbed, or rattled off verses and told tales. To detail these activities in composition and delivery more specifically, a jongleur could be a singer or composer of love songs, comic narratives, heroic lays, or other narratives such as histories and saints’ lives. In the fullest sense of the expression, they would sing for their supper.

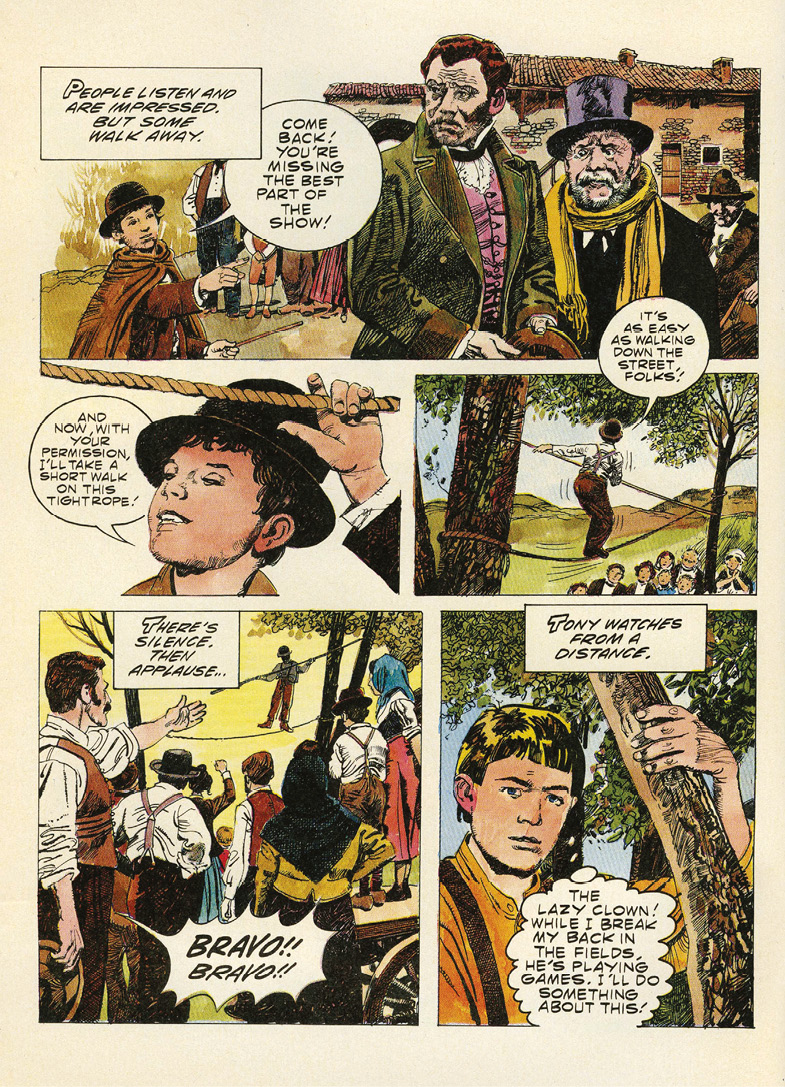

What is more, jongleurs were actors. At the humblest level, they mimed and mummed in dumb shows. Likewise, they tried their hands (truly) as puppeteers. Then too, they served as buffoons, clowns, fools, and jesters. Beyond acting, they ventured before their audiences as musicians, singers and instrumentalists alike. In another direction, they could perform physically as acrobats, contortionists, dancers and dance masters, fire-eaters, gymnasts, jugglers, ropewalkers, stiltwalkers, and sword-dancers, -jugglers, and -swallowers. Among other things, they were conjurors and magicians. To go beyond the purely human, they tamed, trained, and exhibited animals, such as bears, dogs, and snakes, and they entered the fray as equestrians too. All told, it may sometimes seem harder to determine what they were not than what they were. They acted as the archetypal and ultimate crossover artists, prepared to do whatever would attract medieval thrill-seekers.

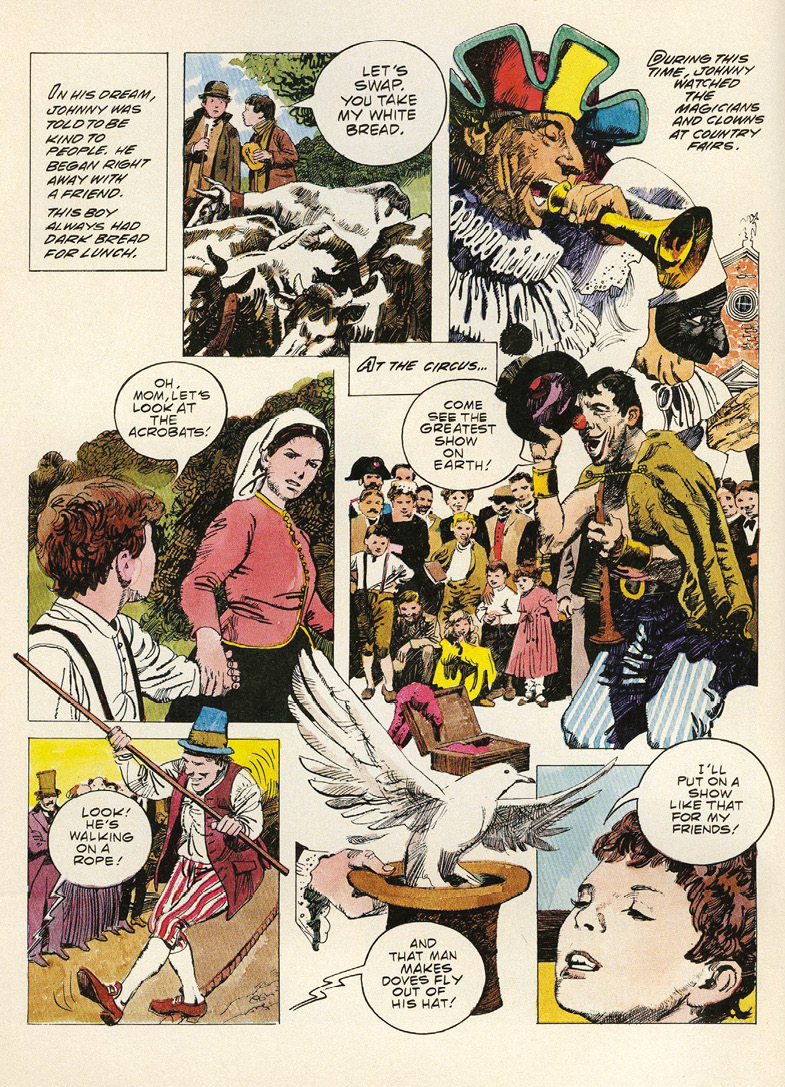

The repertoires of such entertainers were not restricted merely to acts of physical adroitness such as acrobatics, prestidigitation, and juggling. Their stock-in-trade also had a verbal (and voluble) dimension. Indeed, these performers drew upon all the sorts of words and music associated with the wandering minstrels and court jesters who long ago became embedded in modern conceptions of medieval life (see Fig. 2.2). Although sometimes courtly, such figures were often related to discreditable places and activities, such as taverns and throwing dice. A jongleur could be a professional gambler, instrumentalist, or contortionist—or all of the above. Likewise, he could be a mountebank, an individual who would hop onto a long seat to do his act. The last designation, originating in the Italian imperative “climb on (the) bench!,” is a metonymy that tends to imply an inn or alehouse, where the bare minimum of furniture would have been trestles, tabletops, and benches. We are not talking about fancy marquetry. In worlds without theaters, the altitude of such seating was often as close as actors and audiences could get to stages or circus rings. In time, the mountebank became as we know him today, a nomadic charlatan who stands atop an elevation, maybe even a plank on two sawhorses, not so much to enact an entertainment routine as to peddle a nostrum or some other overpriced product of quackery.

Fig. 2.2 Postcard depicting court jesters (L. Vandamme et Cie, 1905).

Guiraut de Calanson, often termed (with only flimsy support) a Gascon troubadour, frequented the courts of northern Spain. In the first two decades of the thirteenth century, he composed a dozen poems in Occitan that are extant today. In one of these compositions, he lays out the talent that a performer worthy of being called a jongleur should have. In enumerating an ideal repertoire, he touches upon the abilities to speak and rhyme wittily, be steeped in the Trojan legend, balance apples on the tips of knives, juggle, jump through hoops, and play multiple musical instruments.

What can the etymology of jongleur tell us? The English is scrounged from the French, which in its turn is a direct blood relative of the Latin ioculator. By whatever name, the term denoted then a joker or jokester, usually professional. At its broadest, the word meant any kind of entertainer. The primary sense of the original noun in the learned language derived from iocus, meaning “game, play, or jest.” The English word “joke” comes from the same noun. In the Middle Ages, both the Latin and vernacular nouns became contaminated by association with a similar-sounding term of Germanic origin, jangler (babbler, chatterbox, gossip, liar, scandal-monger, calumniator). Yet the early medieval labor market did not allow many entertainers to specialize in the arts of speech alone. They learned to move among verbal, musical, and physical skills. Therefore the Latin noun gave rise in English not only to “joker” but also to “juggler.”

Ioculator was but one item in the sprawling Medieval Latin nomenclature to indicate this ilk. In the ferocious Darwinian battleground that language can constitute, this noun rode roughshod over its closest predecessors and eventually displaced them. The results can be cross-checked in many European tongues, including English. Throughout Europe, the Latin word has progeny that go back to the Middle Ages. In contradistinction, the root of histrio survives mainly as a later and learned reintroduction from Greek, whence the adjective histrionic. Likewise, the stem of the other derivative from the same language, mimus, has become largely restricted to the ambit of mime-player. Finally, the Latin scurra has persisted solely as embedded in scurrilous and scurrility. As performers became more professionalized, stark shifts took place in the old meanings of words. In English, the most common derivative of the Latin ioculator became not a “joker” in general, but much more narrowly a “juggler.” In medieval French, it denoted above all entertainers who specialized in song. Similarly, the jester turned into a clown-like figure, even though the name originally implied an artist or teller of tales or stories. A gestour was a teller of gestes, or “stories.” From him descended the jester as we know him. Another Latin noun of the Middle Ages has been largely omitted so far.

The ioculator had a major competitor in the ministerialis. The two, jongleurs and minstrels, were sometimes conflated. The medieval Latin ministerialis, better known now as minstrel, signified literally “of a little minister, servant,” but more commonly “minor court official.” In turn, the term in the learned language came from the noun ministerium for “service, office,” itself derived from minister. It signified the hireling of a lord, either secular or ecclesiastical, or prince. The French for “minstrel” derived from this Latin. The vernacular word soon referred to a person who had mastered a craft. The word to describe what a minister does is ministerium “ministry.” Mestier, the medieval French derivative of that noun, gives us métier.

To slip from conflation to its opposite, a primary distinction has been predicated between jongleurs and trouvères. Cognates of these two terms exist in the language of southern France and other neighboring Mediterranean regions. In presentations of poetics in this other Romance tongue, the two groups are sometimes differentiated by stressing that the joglar performs, whereas the trobador invents or composes. By this standard, the two types of professionals were as distinct or indistinct as artisans from artists. The underlying premise is that the jongleur or joglar is a professional musician and singer, whereas the trouvère or trobador is a songwriter and lyricist—not quite gentlemen scholars, but much closer to them than the jongleurs. The last-mentioned were marginal beings whose social standing and reputation could be deemed equivocal, at best. They were edgy in every sense of the word: they specialized in brinkmanship, by operating at the margins. In contrast, trouvères could have achieved exalted status through their affiliation with noble courts.

The dichotomy can apply as well to Latin. Cognates for trouvères and troubadours are not used there, but substantially the same line is drawn between functions. Clerics could concoct texts in Latin or even in vernacular languages, such as medieval French. Often, they relied upon lay entertainers to deliver them. In this schema, jongleurs perform orally in the vulgar tongue before lay audiences. All the same, we should not suppose that the writers in the Middle Ages who used these words upheld the nuance regularly. We should be even less disposed to credit that composers and performers themselves had fixed terminology to describe themselves. The relevance, or even existence, of such glib sociocultural distinctions between trouvères and jongleurs has been rightly challenged. The differences in meaning between the two are not nearly so straightforward and schematic as some would wish us to believe. Take the courts, for example, where minstrels and jongleurs are often discussed as if they were transposable. As the associations of their name suggest, minstrel is the diminutive of the noun minister. A minstrel can be then a minor official attached to a set retinue. To warrant being named what they were, they may have largely abandoned the rootless itinerancy that put wandering players into friction with the sedentariness and stability esteemed within much of medieval society.

Another factor to weigh is a reshuffling that may have occurred over time. Troubadours who became impoverished may have cascaded many rungs to become jongleurs, while jongleurs who succeeded may have scaled the social ladder. Whatever the causes, over time the neat differentiation between troubadours and jongleurs seems to have become muddied. In 1274, a late troubadour penned a lengthy poem of supplication to King Alfonso X of Castile. In it, he asked that the inhabitants of his kingdom maintain bright-line distinctions between the two groups. This poet approved that the Castilians still discriminated among instrumentalists, imitators, troubadours, and even more reprehensible performers. In contrast, in Provence at the time, the troubadours had become déclassé and lost the cachet of their name, the supremacy that originated in their ability to compose. They were all called jongleurs without differentiation.

Certain proclivities of jongleurs stand beyond dispute. For a start, these performers tended to be transients who subsisted and worked on peripheries. With their special privilege of laissez-aller, they existed at the fringes of princely and ecclesiastical courts, villages, and everywhere else they circulated. The marginality in which the entertainers were enveloped because of their profession meant that they were often considered disreputable—personae non gratae. Yet their rakishness was not an undiluted negative. For instance, they could venture into places where, and at times when, others could not. The protagonist of Our Lady’s Tumbler may have benefited from the carte blanche accorded jongleurs, at least when they appeared as characters in fiction. He seems to have enjoyed license to roam the monastery at will.

When considering the medieval French poem, we must take note that the hero is not a street performer in straitened circumstances, however often grinding poverty and professional failure are assumed to be the case in post-medieval adaptations of the tale. On the contrary, the tumbler has proven himself to be a successful entrepreneur in entertainment. Unlike the visionaries who experienced many of the most important apparitions of Mary in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the dancer betrays no sign of enduring economic deprivation, political upheaval, or brewing war. What he does let drop is that he lives in a time of high religiosity, particularly when devotion to the Virgin enters consideration.

Traditionally, jongleurs were expected to be multitalented. Yet no one individual could be a true jack-of-all-trades, thoroughly competent in all the arts that were ascribed to this class of entertainers. A little before 1215, Thomas of Chobham produced a vade mecum of practical theology on penance and confession for priests, which accrued wide favor. In it, the English-born but Paris-educated ecclesiastic distinguished among three classes of performers, referring to all of them generically as histriones. Thinking of ‘histrionic’ gives a clue. The first category in his taxonomy comprises those who specialize in what we might call physical comedy or burlesque. Part of their disgrace consists in their habit of disrobing to a level of attire (or should we say non-attire?) that common folk found shocking, even horrid. These entertainers rate the lowest in Thomas’s hierarchy. The second of his groupings encompasses gossips, while the third comprises singers. The last two have in common that their tongues wag. He subdivided the vocalists in turn into two clusters, one praiseworthy and the other not worth a tinker’s damn.

The ethical framework of this manual tags as bad those jongleurs who do not direct the body to spiritual goals. These lowlifes do not shrink from unabashed buffoonery in either words or deeds. In effect, they submit the spirit to the flesh. Still worse, they engage as agents provocateurs to sin. By engaging in obscene movements of the anatomy, they incite concupiscence in other people. From Genesis 1:27 on, we know that a person’s frame is made in God’s image. As such, the human body is not to be deformed. Neglectful of this divine analogue, acrobats writhe their limbs out of shape. By employing their physique to despicable ends, they have the look of streetwalkers. If the tumbler were truly like such gymnasts, he would resemble at best a harlot saint like Mary Magdalene or Thaïs before conversion. That is, he would earn his living by selling his body through enactment of base acts. Yet his solution differs, since he does not so much turn away from his profession by leaving it as redeem it by inventing a means of making the performance private and transcendent.

As a caste, physical jongleurs deserve their comeuppance. They not only indulge in frivolity themselves, but even worsen matters by implicating others. Through their sensuality, they stimulate lustfulness and turpitude among their audience. But what can be said of good jongleurs? On the positive side, Thomas excepts from condemnation jongleurs who “sing the lofty deeds of princes and lives of saints, furnish solace when a person is sick or unsettled, and do not commit the disgraceful acts that male and female acrobats perform, as well as those who put on shameful shows.” This laudable type of trouper serves the aims of the Church and elicits wary approval above all for helping to propagate the cults of saints and pilgrimage. The approved kind restricts physicality to a sober-minded bearing and to the playing of musical instruments. To this top-flight echelon in his classificatory system the ecclesiastical writer grants careful but ungrudging approbation. In concluding his consideration, he relates an anecdote about a jongleur. This individual addresses himself to Pope Alexander III to test the waters about his fate in the afterlife. He wants to find out if he can win salvation. His holiness asks him if he knows another trade. Despite receiving a negative answer, the supreme pontiff assures his jumpy inquirer that he can live without fear so long as he avoids suggestive conduct or obscenity.

In the Romance of Flamenca we again encounter three genera of jongleurs, but the taxonomy is not at all the same as in Thomas of Chobham. First come those who sing songs, lyric and narrative; then instrumentalists; and finally, physical performers. Before entering a monastery, the artist in Our Lady’s Tumbler would have been completely at home in this third cadre. By the same token, the acrobat in the medieval French poem belongs to the final one in Thomas’s three ranks of entertainers. His flair, like theirs, lies in the body. So far as we are given to know, our tumbler is an old hand solely in acrobatics, including what we would regard as dance. Indeed, we are told explicitly that he knew only to make his leaps and that he was incapable of anything else. He is not an odd-job man in the entertainment field.

What accounts for the permafrost distrust and disregard in which performers, especially of the physical sort, were held? One pat answer would be that Christians in the Middle Ages were meant to leave the body behind, and not to dwell upon it. The anxieties of people across the centuries about the human plight of having an immortal spirit caged within a mortal frame were captured starkly in medieval debates. In the culture of the Middle Ages, body and soul were often presented as antithetical. Debate poems abound in which the two are pitted against each other. This makes sense, considering that the tension between them is a common and perhaps even a fundamental human dilemma. How do we reconcile two such different pulls upon us?

In such exchanges, the soul often occupied a position of superiority over the body. It held the moral high ground. In other cases, the two were equally inculpated. Within the asceticism and body-denying spirit of medieval Christianity, it was questionable enough for the entertainer to have a sharpened sensitivity to his own body. How could the joy of dance qualify as asceticism? Even worse, spectators would have been inspired too by the tumbler to pay closer heed to their corporeality as human beings. Yet we must also remember that the acrobat kills himself through the mortification of his devotion. He makes his physicality the means to an end: his body serves as the instrument for the expression of his soul in worship. He makes the prison of the spirit into an escape hatch.

Physicality thrusts the tumbler to the bottom of the scale for jongleurs and minstrels. It took a long time for the shame of his corporeality to be destigmatized. Generally, both kinds of artists are portrayed in vernacular literature as being able to sing and play the fiddle-like vielle or harp, as well as perhaps to tumble and perform acrobatics. A manuscript of the Old Spanish Canticles of Saint Mary portrays King Alfonso X the Wise on bended knee before Mary as he calls upon a gaggle of jongleurs, both instrumentalists and dancers, to join him in performing in her honor (see Fig. 2.3). The fragmentary Old Occitan epic Daurel and Beton depicts a professional jongleur named Daurel who possesses both skill sets, musical and athletic. Yet he refrains from imparting his gymnastic arts to his king’s son Beton, and instead gives him a boot camp in music and song alone. Implied is that the physical stunts would ill besuit the station of a nobleman. Whatever their menu of professional skills, jongleurs tended to be regarded with suspicion but not with universal condemnation. A more benevolent outlook upon them can be detected in a thirteenth-century poem by the troubadour Cerveri de Girona, which gives utterance to nail-biting about the spiritual salvation of jongleurs. After initially exhorting them to renounce their wrongful and debasing profession, the poet comes around to urging them instead to put their gifts at the disposal of the Virgin Mary.

Fig. 2.3 Musicians before the Virgin and Child, as depicted in the Cantigas de Santa Maria (Codice Rico). Madrid, Real Biblioteca del Escorial, MS T.I.1., fol. 170v.

The tumbler has in common with the jongleur a mobility that was shared in medieval times almost uniquely by pilgrims and merchants. They could go it alone, or travel in troupes. When plural, they swarmed in a kind of proto-circus. For self-protection, they organized themselves ever more tightly by forming guilds and wearing a distinctive livery. The clothing remains with us in popular stereotypes of clowns and court jesters.

Jongleurs could move from the crossroads, central squares, and street corners of yokel villages to the halls of lordly castles, from the parvises of the saintliest cathedrals to the interiors of the seamiest brothels and bathhouses, and from everyman’s pilgrimage route to the choosiest cloisters. The itinerancy of the jongleurs could border on vagrancy. In a monastic context, steadfastness of place is often designated by the Latin expression stabilitas loci, by which the Rule of Saint Benedict stipulated staying put as one of its most sacrosanct principles. The vows of a Benedictine underlined stability of residence in a single monastery as one of a monk’s paramount duties. Brothers were supposed to abstract themselves from the world at large. By remaining stably in place, they would show the constancy that could elide the otherwise immeasurable space between divinity and humanity. Like the entertainers, the act of wandering elicited praise in some cases and uneasiness in others. The Latin expression homo viator, concretizing the conception of man as nomad, captures the article of faith that the human condition is to range between two worlds. The meandering has logically as its pendants the notions of pilgrim and pilgrimage. But not all drifters were created equal. Those brethren who moved about were condemned for their rambling and roving. Consequently, the monk who was remiss and failed to stay put in one place risked being degraded as a gyrovague. This term for a monastic defector melded a Greek root for a round plane figure and a Latin one for wandering. It has never been thought good to go in circles. The scholar who wheeled about from one venue to another held the shady status of being a wanderer or vagrant. The pilgrim might be righteous or not. The minstrel who accompanied the pilgrim also might be upstanding or not.

When in the world, the jongleur in Our Lady’s Tumbler was a boundary-crosser. No container could hold him: he stretched limits, pushed the envelope, and expanded horizons. In contrast to a pious monk, he could epitomize instability. In some ways, he would have resembled a knight. He strayed about sometimes by himself as a knight errant would do, sometimes among troupes of peers. Yet his errancy was not construed as a redemptive quest. He led a vagabond life. He alternately straddled and transgressed, embodying the concept of liminality by crossing thresholds as he went from town to town on a hunt for income from performances. The society around him almost instinctively conflated physical waywardness with moral or spiritual error. Since to be errant and arrant are closely related not merely in etymology, he was more like an arrant knave than an errant knight. He incurred suspicion for being a desperado, a truant, or even a felon.

At the end of the day, the jongleur was regarded as a weak prospect for experiencing an enduring conversion. He issued from a class seen as being especially prone to recidivism. When he first entered the monastery, the inveterate rambler would become by force of circumstances a stay-at-home—or this story’s medieval equivalent, a stay-in-monastery. In our story, the tumbler remained just as much of a wanderer, as he shuttled between the ground level or slightly elevated plane of the church where the monks carried out their devotions and the crypt below where he executed his performances. For all that, the entertainers had their good sides and strong suits. For instance, they could serve as cultural vectors across geographic boundaries and social barriers. In this function as intermediaries, they could carry culture from high to low and vice versa, ecclesiastical to secular and vice versa, region to region, language to language, and ethnic group to ethnic group. The performers transported stories and techniques across the lines that ran between such steely oppositions as lay and clerical, oral and written, Germanic and Romance, and worldly and religious. In a year-round open season, they lifted material and methods liberally from others, just as others drew at liberty from them. This unrestricted aspect of jongleur life is evident in the many dance steps with which the tumbler of Our Lady demonstrated familiarity. To judge by their names, he was exposed in his earthbound life to a rainbow of different regional styles in gymnastics. In mobility, the jongleurs bore a likeness to the wandering scholars who are often lumped together and called goliards. Yet our tumbler was no free-and-easy student. Whereas the prerequisite for academic status was Latin, he was unscathed by exposure to the learned tongue. If he had a universal language, it took the form of nonverbal communication in the use of body movements and gestures.

Contrary to what many later variants of the story intimate, the protagonist of Our Lady’s Tumbler in its original medieval French verse reflex flourished in his career before entering the abbey. Prior to becoming involved in a miracle tale, he was not a failure but a success story. The geographic diffusion of the balletic steps or acrobatic moves enumerated in his practice suggests that he interacted with entertainers from far and wide. His routinized dance shows the cosmopolitanism of his trade as well as the breadth of his travels and the many ethnicities of his audiences. He was anything but a one-trick pony. Through whatever channels, he familiarized himself with movements indigenous to regions all over Western Europe. Relatively nearby, he was conversant with dance steps or gymnastic moves characteristic of Metz, Lorraine, and Champagne. Further afield, he alluded to Brittany, Spain, and Rome. The distribution may even imply that he traveled in person to these places.

Yet since all the steps or moves named are otherwise unknown and unknowable, the real nature of the drill cannot be reconstructed. Though the play-by-play names names without inhibition, we have no frame of reference for them. We cannot discern how one national or regional style of sport or dance differed from another. To complicate matters further, we must even consider that the complex acrobatic or balletic cycle corresponds to no performance that a tumbler or dancer ever put on show. At the remove of many hundred years, we cannot analogize with confidence to any event in our experience. At one extreme would be calypso or cancan moves in freestyle dance competitions; at another, calisthenics before floor exercises in gymnastics. In any case, the supposed routine could be entirely the fancy of the poet, as a way of almost parodying the overwrought psalmody that goes on in monastic churches. Finally, we have no idea how much the dance varies from one performance to the next. Is it mechanical and even robotic, or it is improvised anew in each instance—does the jongleur rejig his jig each time he does it? The “vault of Metz” is the first and last named regional move that he performs. Does he save for last the best leap or handspring of his imagination? How does his routine relate to the ritualism of the liturgical offices enacted by the monks above?

Our Lady’s Tumbler has sundry associations with Picardy: its dialect contains features typical of the region; it has common ground with the miracles of Gautier de Coinci, who hailed from the heart of the area; it shares motifs with stories from such places as Arras; and so forth. In view of these factors, it is intriguing that in later centuries tumblers and jongleurs from Chauny earned special renown. The Picard town had its own Confraternity of Trumpet-Jongleurs. The guild staged its own festival and went on the road as well. But just as we may not discover much that is meaningful about the supposedly local dance moves that the tumbler made, we are unlikely ever to make great inroads in coming to grips with the particularities of Picard performers. No matter how fine-toothed the comb with which we check the ledgers, relevant information may well never emerge: however great the information explosion may be, not all facts will be at the tips of our fingers.

A stock view in Western Europe held that jongleurs were damned automatically, for the very fact of being jongleurs. A systematic exposition of the Christian faith presents a snatch of dialogue to this effect between its author Honorius Augustodunensis and one of his students. The pupil asks if these entertainers have any glimmer of hope for salvation. His master with the catchy Latin name replies with a stiff negative. The outlook of the churchman meshed with a perspective in which these performers were social outcasts. Often others of this type are mentioned pejoratively, with disapproving terms in French that became modern English lecher and ribald.

Although the relationship of the jongleurs with the clergy was fraught, their standing shot up from the early Middle Ages to the late twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Subsequently, the entertainers who earned their keep in urban or at least curial settings attained a noticeably higher socioeconomic status. Though some remained squalid and marginal, an appreciable number came to have property and wealth. One of them was the tumbler in the original medieval poem, who was far from a penniless failure. The modern image of the jester relates to this intensifying fixity of place or, to be more accurate, milieu. One element in the evolution was the engagement of entertainers with courts and palaces, of both noblemen and ecclesiastical magnates, such as bishops. Jongleur and jester are nearly substitutable terms. An entertainer of this ilk was also attached to a set circle, in this case the entourage of a noble or king. After him, the professional buffoon arrived. Jongleurs and the Church had abundant reason to make common cause when they could. On the clerical side, monks and friars composed legends, increasingly in the vernacular, that they wanted delivered before the widest audience. Sometimes they would have profited from witnessing and appropriating the performance techniques of the jongleurs, to make their own preaching more appetizing. On the other side, professionals had every reason to ingratiate themselves with the clerics who policed many of the common spaces where the largest publics awaited them.

By describing in loving detail the virtuosity of a resourceful entertainer, the preacher who resorted to the exemplum of the tumbler would have coopted some of what his competitors in entertainment had to offer. In effect, the stimulation of hearing an eloquent exemplum about a high-quality performance could have rivaled the experience of watching an actual performer in action: score one for the pulpiteer versus the puppeteer. The equivalence would have held especially strong if the sermon-giver employed gestures or movements to convey mimetically how the acrobat’s tumbling might have appeared. Along these lines, a parish priest is reported to have later called himself a “mime of Christ” in the inscription at his burial place. If true, this allegation would transmute the mimetic art into being an “imitation of Christ.” In this case, the jongleur would have mimed the elation of creation upon being saved. In an added Marian wrinkle, he achieved salvation through the grace of the Virgin. At the same time, one main thrust of the exemplum is to burnish the reputation of a professional entertainer who repudiated his profession and converted. By drawing upon the narrative, a sermonizer would have exalted religious devotion over more earthly pursuits. When a speaker related the story at the pulpit, he could claim for his narrative the full weight of institutional authority. Such church-sanctioned use is what the poet of Our Lady’s Tumbler assumes by referring to the tale as a “little exemplum.”

Many valuations of jongleurs and their colleagues have come to light from the medieval period. Ambivalence about them percolates into plain sight in Gautier de Coinci. The poet of the Virgin takes pains to establish the veracity of the legends he relates. By doing so, he differentiates his narrative repertoire from the fallacious and fraudulent miracles retailed by footloose and fancy-free goliards and itinerant sermonizers. Gautier, nobleman turned Benedictine, monk promoted to abbot, was no jongleur himself. Nor, the odds would imply vigorously, was the author of Our Lady’s Tumbler. But both poets, alongside preachers who drew upon the exemplum for their sermons, had incentive to assert control over the sometimes reviled and sometimes dreaded members of their guild. They could do so by promulgating a view of what a proper entertainer—one who merited the approbation of no less than the Mother of God herself—should be and do.

During the Reformation, all entertainers, both jongleurs generally and jugglers specifically, fell into even deeper disrepute than in the Middle Ages. Furthermore, jugglers and their skill became anti-Catholic slurs in England. Priests who officiated at Mass were likened to entertainers of this sort, as the Mass and transubstantiation were to their characteristic craft. The theologian John Wycliffe went so far as to smear such fathers with being “the devil’s jugglers.” In many parts of Europe a story with a jongleur as protagonist would have stood an even slimmer chance of eliciting favor during the sixteenth-century reform movement than in most earlier times.

Trance Dance

Dance and spiritual practice sometimes relate strongly to each other. No one how-to or do-it-yourself manual can tell everyone how to achieve transcendence through an altered state. For some, the best means of attaining an out-of-body experience comes through the body itself, through the ecstatic ritual of dance. The liturgy of Christian worship may seem excessively verbal and slow-moving, even stalled, but in every single one of its expressions it involves motions as well as words. We would not go too far to say that the prayer books of many denominations seek to formulate for worshipers a coherent message from both a choreography of ritualized steps and a content based on set texts. Analyzed against this backdrop, the juggler had landed in a quandary. As an illiterate lay brother, he was not permitted to participate in the sequence of motions, and he could not understand the foundational texts. The scriptures and formal ceremonies were unintelligible to him. Although not anti-intellectual, he was inalterably unintellectual. What was to be done? His achievement came in dreaming up a silver bullet all his own. His leggy liturgy was a worship with movements and language of his own creation. A clash and crisis follow, since his veneration through dance is initially indecipherable to the other monks. We have competing, mutually uncomprehending, and uninterpretable illiteracies, the one of texts and the other of dance.

Despite the distinctly detail-oriented description that the poet of Our Lady’s Tumbler furnishes, we cannot reconstruct the tumbler’s jumps in their entirety. We are unable to state with assurance how a single move in it would look, or even to establish for sure whether the act was properly a dance, a gymnastic routine, a fusion of the two, or something different again. We do know that a multitude of religious systems, distributed widely across time and space, have allowed for the physical expression of ritual adoration—for sacred performance. In ancient Greece, the athletic competitions of the Olympic Games were tied so tightly to religious festivals in honor of Zeus that they ceased only when the Christian emperor Theodosius banned such pagan cults. In pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, ballgames constituted symbolic and ritual actions while they also served the purposes of politics and entertainment. In Buddhism, monks still dance to offer their bodies to the Buddha.

This is obviously not to say that all dances have been accepted in any religion, and even less that any type of such rhythmic stepping has been rubber-stamped across the full religious spectrum. From the Fathers of the Church through the Middle Ages, Christianity showed itself highly disposed to condemn dancing. Many ecclesiastical councils and synods, as well as texts concerned with penance, leave the distinct impression that priests wished to extirpate dance. The taboos held with remarkable hardiness against any movement remotely resembling it during divine service, especially in sermons and sacred processions. By the same token, dancing elicited frowns and furrowed brows when it took place in hallowed sites, such as churches, churchyards, and cemeteries. By both timing and place, the conduct of the lay brother in Our Lady’s Tumbler was glaringly provocative to orthodox views within Christianity. In almost every way imaginable, but particularly in this one regard, he challenges the inelasticity of the dissociation that the Church sought to impose between lay and clerical culture.

During the same span of a millennium and a half, Christians never stopped gyrating for long. Despite hostility to the medium, some of the recurrent denunciations themselves confirm that dancing took place. In fact, even priests engage in ritual dances sometimes. In special cases, the physical activity could lead to mystical experiences. Through balletic performance the tumbler could have attained a state of altered consciousness that is achieved through the manner of movement known as trance dance. This type of effortful motion facilitates entry into ecstasy. Such a condition of heightened being is achieved, above all, in religious rituals. A particularly ancient manifestation is the leaping for which the followers of the Greek god Dionysus were known in Greece. It was associated with the choral song or chant known as the dithyramb, which to this day is associated with wildness and irregularity. In dances associated with possession, the participants may undergo visitations from spirits that take hold of them. Incidentally, they may do spectacular feats beyond their normal abilities.

The line between religious ritual and entertainment is often porous, especially in the case of fire-walking (see Fig. 2.4). As captured in an image of Fijian men from the 1960s, this sort of religious ritual features barefooted people who lope unharmed over white-hot stones or coals. The tumbler’s performance resembles the custom of the Pacific islanders mainly in his ability to locomote through what a person in a normal state might have experienced as extreme discomfort. The joys of his movement and his worship are analgesic in the same way as religious ecstasy protects pyro-peripateticists.

Medieval asceticism and mysticism abound in manifestations of devotion that originate in self-inflicted suffering. The order of white monks is devoted in large part to the expression of piety through penance. Their goal is to merit intercession, not merely for themselves but also for others. Cistercianism included its fair share of devotees who inflicted penitential pain upon themselves. Alongside exaltation and exultation, the lay brother would have braved with gritted teeth the pain of penitential prayer and worship. The tumbler’s self-imposed physical torment, although whipless, faintly resembles that of radicals in the late medieval movement known as flagellantism who lashed themselves with scourges or cat-o’-nine-tails (see Fig. 2.5). In turn, the European flagellants bring to mind the pious in the yearly ʿAshūrāʾ ritual in Twelver Shiʿism, who march through the streets flogging themselves in remembrance of al-Ḥusayn, the Prophet’s martyred grandson. Loosely similar to both groups, the gymnast puts himself on a treadmill of self-annihilation through physical expression of devotion. By continuing despite exhaustion, he kills himself through the enactment of his love for Mary, working or worshiping himself to death. In the story of Our Lady’s Tumbler, the acrobat suffers the reality suggested by the etymology of contrition, which derives ultimately from a Latin participle for “broken” or “ground down.” He is stomped down through the stamping of his own feet.

Fig. 2.4 Postcard depicting Fijian fire-walking (Suva, Fiji: Stinsons, 1967).

Fig. 2.5 Trade card depicting a flagellant procession in Avignon, 1574 (London: Liebig’s Extract of Meat Company, 1903).

Fig. 2.6 Pieter Brueghel the Younger (attributed), The Pilgrimage of the Epileptics to Molenbeek, late sixteenth to early seventeenth century. Oil on panel, 29.2 × 62.2 cm. Image from Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dance_at_Molenbeek.jpg

The late Middle Ages and early modern era witnessed their own distinctive manifestations of dances in dazes. These phenomena peaked in number and intensity from the late fourteenth down through the seventeenth century. In these events, packs of people would go berserk and engage in a frenzied mass hysteria of dancing in the streets. Such manic episodes hinged upon collective dance that was associated with music, sometimes allegedly either precipitated or palliated by the playing of instruments (see Fig. 2.6). The causes of the flare-ups remain disputable. One explanation that has gained traction lays the blame on poisoning, the culprit being either toxins from infected foodstuffs or bites from spiders or scorpions. Another line of reasoning sees the illness as having no real physiological etiology. Instead, the impulse would be psychogenic or psychosomatic. Supposedly this balletic “monkey see, monkey do” on a grand scale resulted from shared stress.

In contrast to the group dances of the laity, the tumbler’s performance is the solo act of an individual. So far as he is aware, his audience has just one member. His disporting is neither competitive nor spectator sport. Only the Virgin Mary watches him, through the proxy of the Madonna. He does not join others in ad hoc line dancing, but instead remains in solitude. What he does by himself is pray, but for his soliloquy he resorts not to verbose utterances, but to physical maneuvers. He apostrophizes the Virgin through his steps, without realizing that she sees and esteems what he accomplishes. Although not lonesome, the tumbler dances alone. The aloneness of his dance sets it far apart from collective dances, whether in rings or not. If such a thing as penitential dancing existed, it would be his atonement in this way. His dancing is also distinctive in not entailing possession by a spirit. On the contrary, it turns upon performance before an image that leads to the appearance of a presence. But the balletic routine of the individual performer does set the stage for a death that makes him loosely comparable to the victims of the mass dance frenzies. He dances himself into oblivion. Before the tumbler dies, his practice results in a loss of self. Whether his state amounts to mania in any way equivalent to the madness of the maenads or bacchantes in Greek mythology remains open to debate. Likewise requiring further discussion is whether the leaping and falling match up with spiritual exaltation and depression. Is the leaper subject to mood swings in tandem with his physical undulation? One surety is that late in the game he suffers, both physical and psychological, prostration as he buckles before the Madonna.

Christianity is the religion that enters the equation in Our Lady’s Tumbler and its diverse progeny. The tumbler coordinates his personal expression of devotion with the liturgical song of the monks who chant in the church above the crypt. Similarly, he aligns dance from the lay realm with monastic ritual. Both the liturgy and the performance of the tumbler prescribe movements that function as a language of signs. Even so, we must not assume that the jongleur’s routine could correspond reductively, step by step, to an utterance or a text. In part, dancers dance to express what cannot be conveyed verbally, rather than to translate verbal pronouncements into physical actions. In this case, the tumbler makes into motion the emotion that moves more learned monks to transact the set words and gestures of worship.

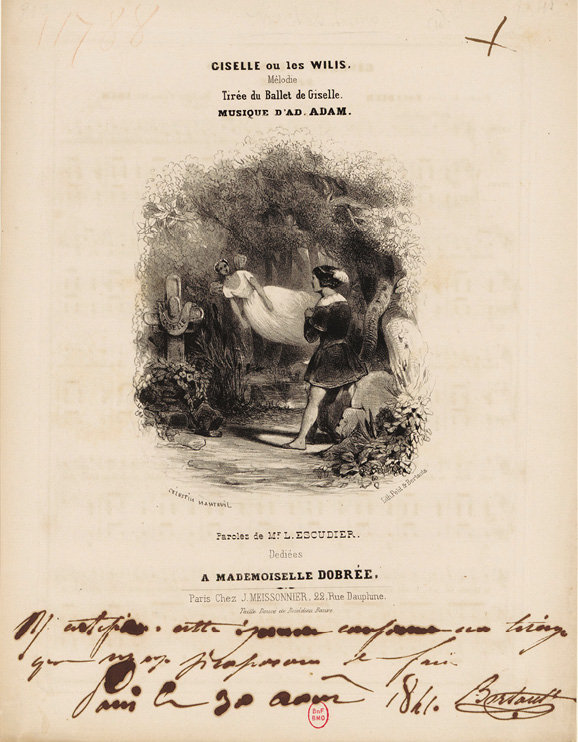

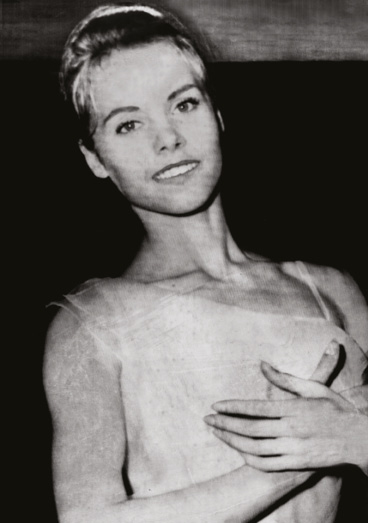

The tumbler shares with the victims of dancing mania a compulsion to dance until he is emptied of all his cyclonic energy and crumples. Indeed, he could be said fairly to have danced himself into his grave. The outcome of self-immolation through this activity reappears in the nineteenth-century French ballet Giselle, or The Wilis, set in the Rhineland during the Middle Ages (see Fig. 2.7). Its star-crossed title character dies of a broken heart after catching wind that her lover is betrothed to another. The Wilis, who summon the peasant girl from her grave, target her beloved for execution, but her love extricates him from their grasp. In legend, these nightwalkers are the ghosts of young ladies who, having died before their wedding days, cannot remain at peace in their tombs. To fulfill the unbridled passion for dance that they could not sate during their lives, they dance in troupes at midnight. Woe betide the young man who meets these seductive spirits, since he must dance with them until he drops dead.

To look beyond the motif of death through nonstop dancing, the routine of the jongleur anticipates approximately the enthusiastic vocalization and bodily movement that have been incorporated into the worship of various religions. For example, adherents of the American religious sect known as the Shakers sang and danced. Similarly, worshipers in some churches in the Southern United States engage in “praise dance” as a channel for sacred expression. Outside Christianity, the fevered steps of the tumbler bear comparison with the corkscrewing moves of dervishes. Such Muslim Sufi mystics wandered from place to place; stood apart from normal people in their dress, behavior, and language; and expressed their piety through a vigorously athletic mélange of music and motion. Like them, the jongleur loses himself in a physicality of bodily movements and touch (by Mary), but, alone when he does his routine, it constitutes at once a private ritual and a one-person festival. More especially, the apparition of the Virgin herself from heaven relates to the collective delusions in medieval dancing mania. Are the collapses of the tumbler merely the unintended outcome of overexertion, or are they the purposeful results of performances designed to achieve ecstasy through whirling? We would do well to recall the etymology in Old English of giddy, which referred literally to scatterbrained possession by a God, and dizzy, which meant “foolish” or “witless.” Older still is the Greek enthusiasm, from a word meaning “possessed by a god.” Thus, our God-filled character was not a madcap innovator in doing his vertiginous dance before the Madonna.

Fig. 2.7 Front cover of Jules-Henri Vernoy de Saint-Georges and Théophile Gautier, Giselle, ou les Wilis, illus. Célestin Nanteuil (Paris: J. Meissonnier, 1841). Image courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. All rights reserved.

The tale does not advocate the abandonment of conventional worship. Rather, it reminds us that traditional veneration exists as a conduit for a spirit of reverence, devotion, love, joy, and hope. All of us must decide for ourselves where soul or mind begins, and where body stops. Likewise, we must determine, for both ourselves and the tumbler, what constitutes thought and feeling, reason and faith. Finally, we should cogitate about song and instrumentation. If music of any sort is set aside, the performance is a form of acrobatics; if the rhythm and melody are internalized, dance results. (Break dancing, which is often held to have originated in the mid-1970s, is only the latest and best-known style of acrobatic dancing, with its spinning headstands, fancy footwork, tumbling, and pantomime.) Laying down a boundary between the two can be ticklish, even impossible.

Jongleurs of God

The jongleur captured the theologians’ attention because he was an antitype of themselves.

The pleasure principles in which jongleurs were ensnared brought them inevitably into tension with Christianity, at least in fits and starts. Were they divine or diabolic forces? Was their artistry licit or illicit? The position of these performers was ambiguous. Often it was judged to be very negative, but sometimes more positive. For hundreds of years, churchmen, almost unanimously, voiced stentorian disapproval of such entertainers. Yet in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, dissenting murmurs of approval can be heard at the fringes of the loudly condemnatory chorus. Indeed, Church luminaries spoke of their own missions in life as resembling those of entertainers. As the jongleur relates to his earthly patrons, so too does the inspired devotee to his divine ones.

Cistercian monks had a complicated self-image as God’s jesters. The foremost exponent of Cistercianism, Bernard of Clairvaux, was accused of having in his misspent youth devised minstrel-like ditties and suave melodies. He referred to himself, no doubt with a measure of irony, as an “acrobat of God.” In a letter dated around 1140, the celebrated saint-to-be presented monastic life as a kind of humbling game that pleases the Almighty even as it elicits stares and sniggers from men. Continuing, he contrasted the transcendence of spiritual exercise to the deformity of physical entertainment. The gymnasts are yogis who practice yoga in ashrams; the others are contortionists who bend themselves into pretzels to divert the public. In a world where values are upended, monks may appear to the worldly to cavort. Elsewhere they will seem to angels to enact a wonderful spectacle.

Understandably, Bernard does not himself refer to spectacle here in describing the behavior of monks. The large-scale, public display that is implied by the concept of the spectacular is attested first in English in a 1340 psalter by Richard Rolle. Interestingly, the mystic writes of such showiness specifically when referring to the “hopping and dancing of tumblers.” The context he evokes is one familiar from present-day reenactments of medieval and Renaissance fairs, in which colorful gatherings of many people include such performers as jugglers, jesters, and other entertainers often popularly associated with the Middle Ages.

To return to the passage by Bernard from two centuries earlier, the gist of his point-by-point description is that professionals, such as actual jongleurs and dancers, turn themselves wrong side up to provide pleasure to their terrestrial audiences. In contrast, monastic brothers exemplify humility and serve heaven. They engage in apparent frolic as sacred play. The Cistercian’s audacious simile is in no way inconsistent with the vitriolic verdicts against jongleurs and other traveling entertainers pronounced by him (even in this very snippet), as well as by other monks and clerics. Yet he opens a pathway to redemption for the professional performers that others who follow him see reason to maintain. After him, his fellow white monk Caesarius of Heisterbach speaks of unassuming souls whom he esteems to be “jongleurs of God and of the holy angels.” He describes folk without airs and graces, who upend worldly values. By the same token, they make what is reasonable seem nonsensical, and vice versa. To him, they are like gymnasts who twist themselves to ambulate with their heads down and their feet aloft. If we let our imaginations run wild, we can make out the gentle sound of their handfall (let us give footfall a sibling). In characterizing the simple man, Caesarius treads carefully among the many connotations of simplicity. He does not correlate the noun and concept completely with simplemindedness or vacuity. Similarly, he leaves implicit the notions of humility, ordinariness, and inexperience.

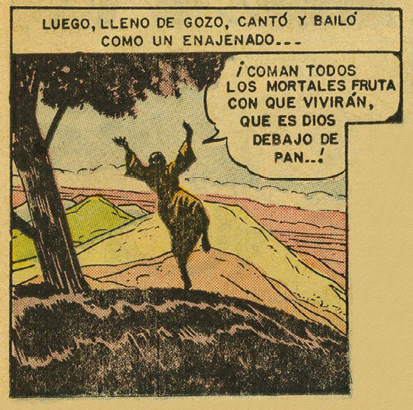

Later, Saint Francis of Assisi transcended simile. He counseled his companions to eschew Latin books when preaching. Instead of putting on any airs of learnedness, he disguised himself as a beggar or busker, performed the medieval equivalent of air guitar by miming a jongleur fiddling, and trilled songs in French. This was one way of saying, “It’s showtime, folks!” All these behaviors had the goal, or at least the effect, of making the public titter at his expense. By extension from their founding father, the Franciscans collectively remain famed even today for having styled themselves provocatively jongleurs or minstrels of the Lord, of Christ, and of God. These pairings were oxymora that bordered on being blasphemous. Despite his miming, the Poor Man of Assisi made apparent that he was a God’s troubadour who juggled with words rather than physical acts (see Fig. 2.8). He took a bold roll of the dice by equating the words of songs such as lyrics and ballads with the Word of God, and vernacular entertainment with Latin preaching. In all cases Francis and the friars minor served as jesters of the divinity, not of the Church. They claimed divine rather than ecclesiastical sanction for their conduct. The ruler for whom they tumbled was God; the court, heaven.

The first generation of the saint’s original stalwarts supposedly included Brother Juniper, who joined the friars in 1210. Known in time as “the jester of the Lord,” this legendary figure was renowned for simplicity and humility. At the same time, his radical humbleness caused him to be bracketed as a fool. Through pranks and practical jokes, hoaxes and hilarity, Brother Juniper defied social norms and sought to subvert them. In contrast, our tumbler abstracted himself from the conventions of the closed society that he entered within the abbey, and charted and piloted a course uniquely his own, without making the slightest effort to prescribe it to anyone else.

Fig. 2.8 Film poster for Francesco, guillare di Dio, dir. Roberto Rossellini (Minerva Film, 1950). © Minerva Pictures. All rights reserved.

The example of Francis, building upon that of Bernard of Clairvaux, had a strong bearing upon the standing of jongleurs, at least in similes and metaphors. The Castilian poet Gonzalo de Berceo differentiated between two classes of artists in societal rank, presenting himself as a troubadour when singing to the Virgin, a jongleur when dealing with Saint Dominic of Silos. Nicolas de Biard was a mendicant preacher of the late thirteenth century in Paris who assembled two much-esteemed sermon collections. In one of them he likened confessors to jongleurs, or vice versa.

Francis was not the only jongleur-like solitary who attracted enough champions to warrant founding a religious congregation in the early thirteenth century. Blessed John Buoni was another. He lived licentiously as a professional entertainer until suffering a near-fatal illness at around the age of forty. After that moment of truth, he saw the light in 1209. He turned into a true troglodyte, a bona fide hermit in an equally real grotto (see Fig. 2.9). Through his stringent asceticism he attracted hermitic acolytes. In 1217, he formally established a following. His admirers became known as Boniti, after his cognomen.

Jongleurs of God stand not too far from jongleurs of Notre Dame. What is Our Lady’s tumbler, if not such a minstrel of Mary? Like others of this kind, he consolidates two qualities that would seem mutually exclusive. Though humble to the core, he is still so self-assured that he rashly breaches the conformity and obedience required by monasticism and even by Catholicism. He throws caution to the wind and improvises an entire liturgy for himself, determined not by readings, chant, and hallowed movements and objects, but rather by a physical performance that he has devised from scratch. Contrary to the very basis of monasticism, he serves as his own drillmaster and taskmaster. Such pluck might seem dim-witted, but the apparent empty-headedness is holy.

Fig. 2.9 John Buoni. Engraving by Adriaen Collaert after Maerten de Vos, 1585–1586. Published in Jan Sadeler, Solitudo, sive vitae Patrum Eremicolarum (Antwerp: Jan Sadeler, ca. 1590s).

Holy Fools

We are fools for Christ’s sake, but you are wise in Christ.

The distinction between faith and folly can be cut very finely. If truth be told, the dividing line may be invisible to the naked eye. The fool of God, also known as the holy fool, is an even more multifaceted and omnipresent conception from medieval Christianity down to the present day than is the acrobat of God. The two concepts are interrelated, and the figure of the jongleur has sometimes been superimposed upon that of the holy fool.

From one end to the other in both time and space, the Middle Ages were anything but foolproof. That said, the notion of the fool of God or the fool for Christ became disseminated far more widely outside than inside Western Europe. The cultural importance of this type has loomed large, first in the Greek East and later in Russia. One of the first attested examples of such a character is the sixth-century Symeon of Emesa. Two other cases, both fools who happen to be nuns, are found in the Lausiac History, a major compendium of traditions about the desert fathers that enjoyed popularity through the East. Such figures often make idiots of themselves in public through (un)intentional absurdism. They engage in seemingly weak-minded behavior from which a clear-headed person would refrain. They dispose of all their possessions, sometimes even down to much or all their clothing. They express themselves in babbling or blustering twaddle that others may find inexplicable, meaningless, or even unhinged. Yet there is method to the madness. From one perspective, these religious fools may appear to profane the sacred. From another lookout point, they take to an extreme what is called in Latin imitatio Christi. That is, they humiliate themselves to imitate the humility and humiliation of Jesus.

Within Western Europe, Saint Francis of Assisi stands out as the paragon of the holy fool, just as of the jongleur. His clowning had the collateral effect of illuminating the degree of his simplicity. The jongleur of God reportedly presented himself likewise as a slow-minded fool or jester of God. He and the first generations of Franciscans paralleled the tumbler in rejecting the finery and splendor of the conventional Church for lowness and abasement. For their stance, they earned regard as what Erasmus called “fools to the world.”

Beyond the general homogeneity of the protagonist in Our Lady’s Tumbler and of holy fools, it bears noting that the exemplum resembles accounts of so-called hidden saints. These secret servants of God are typically retiring in their comportment. They slave at a humble vocation, their sanctity unrecognized by others. An archetype would be Saint Joseph, the carpenter. Such holy men are numerous in Byzantine hagiography. There we encounter individuals whose holiness goes undetected or is even mistaken for negative qualities, such as derangement. A lesson could be drawn from all these stories that communities are not always capable of the discernment required to tell apart a mere jongleur from one of God, or a fool from one of God. For instance, Daniel of Scetis, an Egyptian monk and abbot, tells the tale of Mark the Fool. This saint pretends to be demented and passes himself off as a raving lunatic. For eight years, he plays the role of a Robin Hood among fools by distributing to others what he begs and steals. It emerges that earlier he had lived fifteen years in a monastic community, before his eight years as a solitary. On the morning after the facts of his life have become known to the pope, Mark dies and subsequently his body emanates the odor of sanctity—a mystical scent of incorruption that was construed as a sign of saintliness. Another example is a narrative recounted in the vita of Daniel himself. While visiting a convent, he allegedly witnessed a sister there who to all appearances was sprawled intoxicated. That night the future saint and his disciple observed how the same nun would stand in prayer until a passerby appeared, at which point she would sag to the ground. They brought this behavior to the attention of the abbess, who realized rapidly that the alleged falling-down drunk was a hidden saint. When the report of the sister’s piety spread, she fled the nunnery. Still other tales in the genre have principals who are entertainers, apparently leading unseemly lives but in fact recognized by God as being on the side of the angels.

The type of behavior that these individuals display is attested in Byzantine hagiography throughout the Middle Ages. A memorable case of such holy and high-functioning folly from the fourteenth century is Maximos. This man, a soon-to-be saint, acclaimed from childhood for his devotion to the Virgin, became a monk rather than enter into a marriage arranged for him by his parents. In Constantinople, he dwelled for a time in the gateway of the church of Saint Mary of Blachernae in the guise of a fool for Christ’s sake. Later, on Mount Athos, Maximos earned his colorful cognomen, the Hut-Burner, as a kind of auto-arsonist. Whenever he moved to a new dwelling for greater seclusion, he would torch his old hovel.

Likewise worth mentioning are the later Russian descendants of the Byzantine hidden saints—the holy fools or fools in Christ—who are stock characters in first Muscovy and later Imperial Russia. In Western Europe, fools of God are far from unknown in French literature from the early thirteenth century. To cite only two examples, Life of the Fathers contains a story that goes simply by the short title “Fool,” and Gautier de Coinci wrote a miracle on the topic.

Distinct from a saint who poses as a fool would be a court jester who has occasion to display miraculous piety. In 1878, the German author Gottfried Keller composed a poem based on a purportedly actual event of 1528. Entitled “The Fool of Count von Zimmern,” the piece describes how an entertainer of this sort was called upon to assist in the office when the chaplain was shorthanded. At the point when a bell was to be tolled, none was to be had, and so the joker improvised by shaking with all his might to jingle his fool’s cap, whereupon a golden glow shone out from the large lidded flagon that held the host for the Eucharist.