3. Cistercian Monks and Lay Brothers

© 2018 Jan M. Ziolkowski, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0132.03

He who labors as he prays lifts his heart to God with his hands.

The Order of Cîteaux

Our Lady’s Tumbler manifests vividly both strains and rapprochements that recurred between laity and clergy within medieval Christianity. It offers a mostly laudatory close-up of life among the white monks in the twelfth century. Its protagonist stands in deep awe of Cistercian monasticism. Despite all this, it demonstrates that at least this once, the layman goes the monks one better in devotion. The amateur prayer outwits (or outdoes) the unpaid professionals at their own game. The stresses heightened during the late Middle Ages, before finally scoring their most drastic effects in the temblor and aftershock known as the Protestant Reformation and Catholic Counter-Reformation. Our story, from roughly three centuries earlier, has at its hub issues that anticipate the shock waves to come in the later period. To be specific, it points out cognitive dissonances between the faith that was professed in Christ and apostolic life, and the attitudes encoded in daily life within leading religious institutions. Let us look closely at how the tale of the tumbler fits within Cistercianism.

The medieval French poem that forms the cornerstone of this book tells of a prosperous minstrel who wearies of his secular lifestyle and its turpitudes. In response, he redistributes his worldly possessions, such as money, horse, and clothes, and joins the Cistercian monastery of Clairvaux as a convert. He is not said to enter a novitiate. The untested brother has the objective of devoting himself to God, or rather to his more approachable mediator, the Virgin Mary. The initial dilemma, if not tragedy, for the former performer is that he takes the step of committing to a new walk of life within a monastery without grasping what it entails. At the time of his conversion, he does not know that he should be concerned about his preparedness to be a brother, nor can he gauge realistically whether he has the wherewithal in cultural literacy and the psychological temperament for the monastic mode of life. Soon after his induction, he discovers to his consternation that he is out of his depth. He lacks the savoir faire and savoir dire to fulfill the services required of a monk.

The value of the entertainer’s donations to the abbey could have been substantial. In the economy of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, jongleurs were often remunerated in kind rather than in cash. The objects that the minstrel conveys to the abbey are interesting, but when all is said and done, what he leaves behind matters less than what he takes on by embracing the specific brand of monkish life that the Cistercians represent. He goes from being at least modestly successful in the medieval entertainment world to being an underachiever and a nonentity as a monk in this order.

Cistercianism was a new branch of monasticism that had been inaugurated in France at the very end of the eleventh century, around 1098. Although not a Crusade movement, it was established in sync with the first of those expeditions. Indeed, it absorbed many young men of the same sorts who were drawn to the movement across Latin Christendom to recoup the Holy Land for Christianity. From its inception, the order was tied closely to the Virgin, and it grew apace with the rise of Marianism in the twelfth century. It soon diffused throughout Europe. By 1200, the Cistercians tallied five hundred abbeys for monks and probably, grosso modo, the same number of convents for nuns. By the end of the thirteenth century, the white monks, as they were often styled, occupied approximately seven hundred houses. The explosive enlargement was not without growing pains. Eventually, envy over their ease in accumulating immense tracts of land and the resources that issued from them meant that the order incurred plenty of vilification, alongside praise. Even the monks themselves sometimes gave voice to fretfulness about what would be defined today as mission creep.

For the site of their seminal “New Monastery,” the founder chose Cîteaux, south of Dijon in France. Cistercianism promoted a radical reformation of Benedictine monasticism by emphasizing a literal, even fundamentalist interpretation of the celebrated sixth-century Rule of Saint Benedict of Nursia. The movement was formulated for frugality, in conscious reaction against the perceived immoderation of Benedictinism. Its aesthetic, in architecture, manuscript production, and all else, was deliberately humble. In fact, humility may well have been the most prominent of the values that the Cistercians professed. All branches of Christian coenobitism have had their own forms of law and order at their core, but the Cistercians were especially strict. Sundry dos and don’ts set these brethren apart from their confrères in longer-established orders. In contradistinction to the major older ones, the white monks did not acquiesce in child oblation (the practice of giving children to monasteries or convents), ran no schools, and expected postulants to have been educated before seeking entry. The last factor is intriguingly relevant to Our Lady’s Tumbler.

Fig. 3.1 Postcard depicting l’Abbaye de Cîteaux, Saint-Nicolas-lès-Cîteaux (early twentieth century).

The original medieval buildings of Cîteaux have all but disappeared, beyond rack and ruin. The place took its name ultimately from the Latin for “cistern,” a holding pen for runoff precipitation. Calling their venue after a catchment for rainwater acknowledges nicely its location amid the effluvia of low-lying swamps and swales. Benedictines—or, to use a name for the order after its tenth-century reform, Cluniacs—were montane: they tended to inhabit mountainous heights. They liked to be between a rock and a hard place. Whereas they sought out the highlands, Cistercians gravitated toward the lowlands (see Fig. 3.1). They were paludal and fluvial. Initially, they took as theirs the rural marshes and riverbanks, wetlands and boglands, basins and springs of France. Soon, they fanned out to similar environs elsewhere with high water tables, inhabiting neither terra firma nor open sea, making fens far and wide their own. The contrast between the two orders was embedded in an old aphorism that encapsulates the locations that their respective initiators purportedly favored: “Bernard loved the valleys, Benedict the hills.” Put differently, the white monks situated their monasteries with the goal of being siloed and freestanding. As their wasteland, the desert fathers of late antiquity had had windswept and sand-covered barrenness, especially in Egypt. For the Cistercians, Cîteaux constituted their equivalent: drainage trumped dryness. Even so, they saw their home as harking back to the glory days of asceticism: one of their foundational texts from the early 1120s refers to the site in France as a desert. There they emulated the way of life that they believed the original inhabitants of such spaces had practiced in the third and fourth centuries, and aspired, like the earlier Christian hermits and monks, to simplicity, poverty, and chastity.

Monasticism has at its heart an antinomy that is latent in the very noun monk. In fact, the etymological meaning of the word flatly contradicts the communal nature of the organization it customarily assumes. It derives from a Late Greek substantive for “single” or “solitary,” itself from the earlier “alone.” Ordinarily, however, the people dwelling in monasteries are anything but alone. On the contrary, as the rank and file of tightly organized religious communities, they have no choice but to be gregarious. In performing the liturgy and especially in chant, they act in synchrony as a team. They should share an esprit de corps. In hardheaded terms, monastic brothers are not alone at all. Rather, they live shoulder to shoulder. Even referring to them as brethren indicates that they are bound together in something larger, an elective extended family. In acknowledgment of this reality, they are known as cenobites, from a Greek word composed of elements that mean “common” and “life.” They form complex societies, with a social contract. Within these groups, specific liturgical duties are shared by individuals who also execute a varied range of specialized functions. They imprison themselves voluntarily in cells, perpetually in a self-imposed lockdown. Still more paradoxical than monks generally are the Cistercians particularly. Their order encompasses both withdrawal and engagement—both the wilderness and the world.

All the paradox accords well with the situation of the tumbler. He barters away a life in which he is a loosely regulated, venturesome individualist. In place of such freedom, he takes on the millstone of rule-bound conformity to set hours and practices. When the swap proves to be untenable for him, he devises or improvises a fix that fuses individualism with communitarianism. Small wonder that his story would regain appeal in the modern world, which has displayed inconsistencies as keen as any ever before about the mutual rights and responsibilities of individuals and communities.

Cistercian communes were meant to be secluded from the secular world. Architecturally, they achieved this objective through claustration—that is, they confined their members within cloisters. To the same end, the abbeys were situated in unpopulous regions so that the monks could worship God apart from the distractions and irritants of worldly activity, by conducting a celibate life of devotion and work. Thanks to their location in wildernesses, the brothers of this order often turn out to bear at least some sketchy likenesses to solitaries. Despite their sometimes cohering in communities, they can be antisocial or even (to push the point) downright misanthropic. After all, the noun “hermit” denoted originally a person who inhabited a desolate place in isolation. Heremum is Latin for “desert” or “wasteland,” a place in the middle of nowhere. Yet a fundamental difference remains between the two classes of religious. Whereas a hermit runs a one-man operation, a monk does anything but that.

A monastery has a complex ecology. The hermitage stands in opposition to the abbey, where the foodchain is topped by the official who gives the institution its very name. The term abbot goes back ultimately to Aramaic. In the New Testament abba is a form for “father” that Jesus and Paul use in addressing God intimately. Whereas the nature of eremitic life is solitude, the word for the leader of a monastery presumes the collectivity of a family. It also presupposes patriarchy and paternalism (the question posed in the slang expression “Who’s your daddy?” has never required more than a split second for monks to answer).

Within a Cistercian context, the heads of a handful of the oldest communities, such as Cîteaux and Clairvaux, have additional special status as proto-abbots. That is, they could be considered “abbots plus” or superfathers (better than superdad). At the top of the paternalistic pecking order, they figure out how to administer love, including tough love, toward the end of helping individuals grow and communities cohere. The chief job requirement might be called prior knowledge, especially in the form of Menschenkenntnis or (to translate the German) people knowledge. These monastic managers are owed obedience. In the story of Our Lady’s Tumbler, the monk who sees the tumbler’s performance finds it both ridiculous and unnerving; he hastens to deprecate the incongruity that arises when the lay brother unclothes himself to show submission through dance to the pious solemnity of the Virgin (and presumably Child). Yet the head of the abbey refrains from joining a rush to judgment about the unconventional behavior of the erstwhile entertainer. In the end, the abbot models multiple lessons for the brethren under his charge. The most important may be a deeply Christian message of tolerance. In his wisdom, the superior of the monastery takes his time to watch and listen: he is all ears. He conveys that it is not right to devalue or condemn any form of worship based upon sincerity. Sincere devotion to God deserves understanding and even praise.

The minstrel in the medieval French poem takes very seriously the final say of his superior. A little while after the principal of the monastery has sighted the display of miraculous favor by God’s mother in the crypt, he summons the tumbler to his office. The abject entertainer, who has bizarrely performed his lack of stature through a ritual of his own making, expects that he has committed a trespass and that he will be expelled from the abbey. Instead of making him an outcast, the kindhearted abbot bids him to recount his life story, from beginning to end. After hearing it, he assures the minstrel that he will be in good odor in their order—and they in his.

What does this distinction between two communities mean? The tumbler is designated a convers, a word that could be translated loosely as “convert.” As such, he held a status not necessarily identical with a full conversion to monastic life. In some ways, the functions of a laic convert, and the position of the jongleur as such, speak to the abiding tension between the two views of monasticism, hermitic and cenobitic. Even more broadly, the lay brother carves out a no-man’s- or no-monk’s-land in two tripartite schemas that are often invoked to describe the warp and weft of medieval society.

One framework comprises the three orders of the faithful, namely clerics, monks, and laymen. The other threesome comprehends those who pray (meaning clerics and monks), those who fight (the nobility), and those who work (peasants). Within this second triad, toil signifies above all agricultural labor in the production of food. The lay brother fits frictionlessly into none of the above slots. He embodies a radically new construct, as a layman, usually from the rural poor, who can shed the scarlet letter of being illiterate and lead a life that virtually guarantees salvation. The jongleur is an individualist, in leaving society outside as well as in striking out on his own within the monastery. First, he abandons the world. Then, after getting off to a halting start as a cenobite, he makes himself into a do-it-yourself recluse.

With the intent of earning redemption or at least of showing penance, the former entertainer goes off to be at one with God, or rather with the Virgin. He breaks away from the communal liturgical offices to perform in camera his personal rituals of penance and devotion. In doing so, he enacts a solitude for which the white monks were known. Yet he achieves this end in a manner that would almost not have been permitted within the realities of Cistercian regulations governing both monks and lay brothers. In effect, he invents his own form of contemplative spirituality. He becomes a contradiction in terms. A recluse within a cenobitic community, he lives solitarily within a well-run organization that is structured around communal life. Such a paradox may have been lauded in eulogies on Clairvaux, but it is dubious that such nonconformity would have been countenanced in the actual day-to-day business of the monastery.

Cistercianism could not have survived long, and could not have burgeoned with as much vim and vigor as it did, without the involvement of “converts” or lay brethren like the tumbler. The order specialized in first acquiring land that had hitherto been agriculturally unproductive and then fructifying those same fallow swamps, valleys, and springs. This was the turf war in which they engaged with the Benedictines and other religious societies. The monks dammed waterways with weirs to create fish ponds, channeled running water in millraces and flumes to power mills and presses, planted crops on new tillage, established vineyards, and herded sheep and made wool. For their establishments to be self-contained, managing all the temporalities and carrying out all the many agrarian tasks required a sizable work force. The so-called converts were the best solution to the chronic problems of being overstretched and understaffed. By enlisting extra help from such operatives, the full monks could have many hands available for manual labor without altogether sacrificing the proposition of uncompromising disengagement from the secular world. That said, the lay monks never outnumbered the so-called choir monks. The plus side to the care shown in keeping down their tally is that the order did not lose its founding focuses or values. A not-so-good drawback is that, if we allow ourselves anachronism by imposing present-day business administration upon the distant past, the organizational chart of a typical Cistercian foundation could have been regarded in present-day terms as top-heavy, with a preponderance of staff in administrative positions. Especially at times when the monasteries were undermanned, friction between the two groups was inevitable. To invoke a twentieth-century synecdoche, the tensions between lay and choir monks would have sometimes resembled the oppositions between blue-collar and white-collar workers.

The categories of the convert monk and the lay brother were not always synonymous. At times, the Latin conversus was applied to any adult entrant into monastic existence. Such a full-grown joiner stood in contradistinction to the child oblate. In the learned language, the word for a convert implied a phrase that denoted “to the monastic way of life.” Within Cistercianism, the term evolved to signify a lay brother, usually of humble peasant stock. The monasteries did not hold to an open-door policy of accepting all would-be entrants, but they needed strong hands, sturdy backs, and stout shoulders, and the lay brethren contributed to monastic life first and foremost through heavy toil. The hardest work took place on the abbatial estates. These operations usually served agricultural purposes, as may be surmised from the usual name for such an estate, grange, which derives from a Latin adjective that relates to (and is cognate with) “grain.” Most often, lay brothers lent a hand with the grueling drudgery of food production. As farmhands, they provided the animal husbandry connected with sheep, grew vegetables and herbs, cleared land, and managed irrigation. In addition, they commonly ran the kitchens, infirmary, and guest-house. Their living conditions could not hold a candle to those of the full monks. Yet under the best of circumstances the two monastic sorts coexisted in mutual respect and interdependence. In a metaphor that drew upon specific personages in the Bible, the lay brother played the active role of Martha in executing physical labor, while the choir monk acted out the contemplative one of Mary. At least ideally, both types of brethren aspired to spiritual redemption, and both had equal claim to salvation.

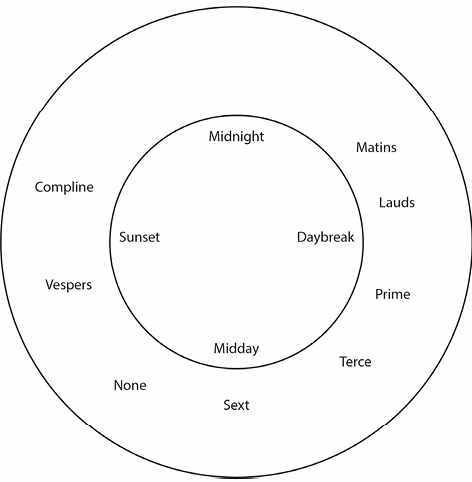

Choir monks were bound to perform the divine office in choir, to pray and study, and to do manual work. The first chore required, among other things, knowing by heart in Latin the hundred-and-fifty Psalms. As much as anything, the occupation of Psalm-singing marked these monks apart from the rest of society. It positioned them to be quasi-angelic. In contrast, lay brothers were exempted from liturgical practices that, nearly without exception, their counterparts in the choir were obliged to fulfill. Mostly illiterate, perhaps proud possessors of experiential knowledge but almost invariably intellectual vacuums where formal education entered the picture, these laymen were not called upon to engage in the so-called divine reading. Lectio divina, to use the customary Latin phrase, was a practice of unhurried scriptural reading, contemplation, and prayer that was cultivated by Benedictine monks and others. And thus, questions arise about whether the very existence of lay members implies that the equilibrium between the office and work, or between contemplative study and corporeal slog, had been lost unrectifiably.

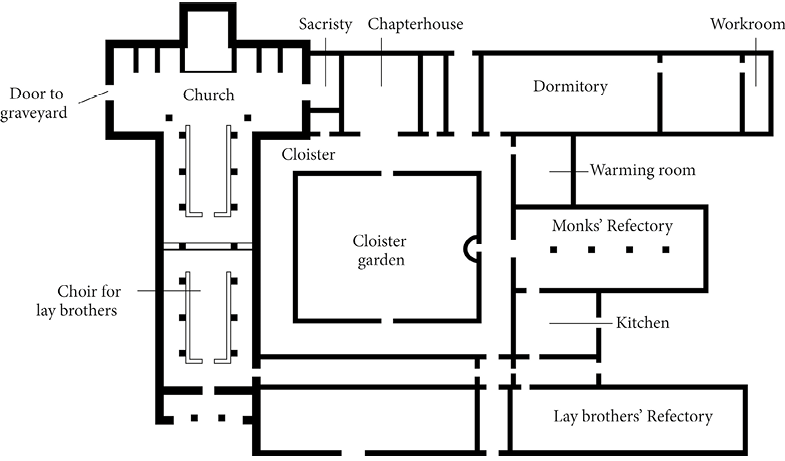

Even under the most auspicious circumstances, lay brothers would generally have been segregated physically from choir monks in worship as well as in the remainder of life. The monastery was a house with many rooms, and a large number of the most prestigious ones lay off limits to the conversi. Within the honeycomb of the monastery, lay monks had their own separate spaces in the church, the meeting place known as the chapter room, the dining hall called the refectory, and the dormitory (see Fig. 3.2). Typically, the domain of the lay brethren was situated in the west range of the cloister. Inside the church, they were not allowed access to the choir, where the regular monks performed the office. Instead, they were quarantined in stalls outside and to the rear of it. The separateness was enforced by a partition, such as a roodscreen. The balance between the dueling duties of the lay brothers to do manual labor and to participate in the liturgy was disputed. They were expected to execute only a shortened form of the office, since often at the set hours for prayer they were far from the monastic churches and carrying out the tasks that had to be done in the fields. The lay members also would not have been included in most all-hand meetings in the chapter house, where abbots delivered homilies: the monasteries were places where preaching was nearly always directed at the choir monks.

Fig. 3.2 Floor plan of a typical Cistercian monastery. Vector art by Melissa Tandysh, 2014. Image courtesy of Melissa Tandysh. All rights reserved.

The reasons why monks of this higher class could have justifiably missed the office are few, but their lay counterparts had many more sound excuses. Bernard of Clairvaux, the great Latin preacher of Cistercianism and much else, reportedly uttered a sermon in praise of one such conversus. A busy farmworker, the poor soul in question failed to take part in the worship of Mary at the monastery in order to discharge other obligations on his to-do list, of which some necessitated his presence at a grange that was far off the beaten path. When lay brethren happened to be present at the main institution, they were to perform their version of the office silently. In the meantime, choir monks chanted theirs on the other side of the partition that ran between the two groups. Lay brothers differed, because they specialized in physical labor as contrasted with the opus Dei, or “work of God,” that took place in the choir. All the same, they were not meant to be second-best citizens.

The Cistercians’ empathy for badlands and solitude remained strong across the centuries, but the breakout success of the order meant that very soon the marches of Cîteaux were not the only place with which these monks were identified. Before long they became known equally, or even more, for Clairvaux. The “bright valley,” to put its name into English, was a beacon toward which Christians flocked from throughout the West. The abbot of the monastery there was Bernard, the most prominent exponent of Cistercianism. This saint in the making sought to place his foundation under the tutelary spirit of Mary. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the abbey acquired massive power from the trifecta of its associations with the white monks, Bernard, and the Virgin.

Cistercians and the Virgin

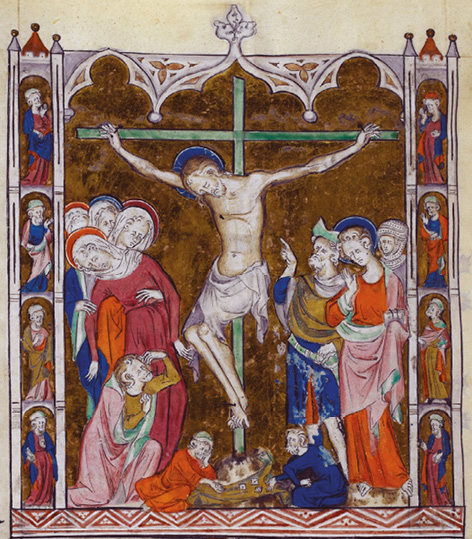

The theological term hyperdulia combines two Greek words meaning “more than” and “servitude.” It signifies service to the nth degree—super-service, as it were. It denotes the special veneration, next to the worship due to the Lord, to be paid to the Virgin in acknowledgment of her unique status as the Mother of God. Such ministrations to Mary sprang up in the Middle Ages. Among the many groups and individuals who aspired to render tribute of this kind, the Cistercians stood out for the intensity of their deference. The Virgin occupied the center of their universe (see Fig. 3.3). They consecrated themselves to her, and in return she acted as their hidden advantage. If the search for salvation had been a card game, she would have been their ace in the hole.

In all their locations, the Cistercians were marked by their aspirations toward simplicity, asceticism, and holiness, and they strove toward all three goals at least partly in the name of Mary. We can be confident that the Madonna was the sole female presence in the otherwise all-male environment of most monasteries. What was she doing there? She exemplified monastic virtues, since she practiced asceticism and study. Like at least some of the monks, she remained a lifelong virgin. As all of them had taken a vow to be, she was chaste. Mary also specialized in intercession. This was likewise the remit of monks, especially white ones. In this capacity, she was the sovereign mediator, the special patron and point person for their whole order. Christianity is, by its very definition, Christocentric. Yet Jesus can be forbidding and fearful, even terrorizing, to the skittish. Here the intercessory role of the Virgin enters the picture or even (since images are at stake) becomes it. (In emergencies, she is the hotline to call. Better still, she is the switchboard operator.) She can be asked to approach Christ for any help that is needed. Jesus remains at the top in the hierarchy of the holy, but the Mother of God comes next, well before saints and incalculably far before ordinary people on earth.

Fig. 3.3 Jehan Bellegambe, The Virgin Sheltering the Order of Cîteaux, 1507. Oil on panel, 91 x 74 cm. Douai, Musée de la Chartreuse. Image courtesy of Musée de la Chartreuse, Douai.

In this world, self-help or how-to guidance played no role, except in figuring out how best to beseech Mary for her intercession. She was the genie whose response to prayer would be “Your wish is my command.”Among the highest and rarest forms of devotion that faithful followers could promise was to consecrate themselves to the service of the Virgin. In a way the tumbler manifests this type of observance. Merely by joining the Cistercian order, he takes upon himself an institution-wide obligation to practice devotion to the Mother of God. Beyond any official responsibility, he undertakes a personal commitment by descending into the crypt to perform his routine in honor of her.

In return for his dedication the tumbler seeks no specific recompense, least of all a miracle. Although the Virgin wipes or fans his sweat-beaded brow, we are not given to understand that he has any awareness of the gesture. He apparently has no idea that she has taken upon herself to be his guardian angel. From what we can judge, whatever she does is impalpable and immaterial to him. We learn only that others witness the boon he garners from Mary herself for the attentiveness he has displayed toward her Madonna. Such care in the fulfillment of obligations toward the Mother of God is a hallmark of lay brothers as they are portrayed by their advocates in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. When the soul of the lay brother is wrested from the devil, thanks to Mary, the performer is already dead. Consequently, he does not know while still a mortal the premium he has earned. He has not received breast milk from the Mother of God, as legend would hold that Bernard of Clairvaux did, but he has been saved. In the process, the very nature of Christian worship has been demystified. The hocus-pocus of the liturgy has been set aside.

The entertainer’s constancy is distinctive in its specific form of expression, but parallels the solitary worship of the Virgin by this Doctor of the Church. The saint’s trueheartedness to the Mother of God is well attested from sermons and prayers, and his voice, amplified by successors who only heightened the intensity of his Marianism, became a dominant one in the Mariology of his day. Both before and after him, Cistercian writers were passionate proponents of Mary. After championing the Blessed Virgin in his lifetime, Bernard was laid to rest before her altar. In his own afterlife, he achieved recognition for his dedication to the Mother of God from Dante, who chose the sainted white monk as his final lodestar in the Divine Comedy. Eight hundred years after his death, Bernard was memorialized for his inspirational relationship with the Virgin by being pictured with her on a commemorative stamp from the Vatican.

Across the various orders, and across time, Christian monks and nuns have viewed Mary as embodying monastic virtues. Among the qualities in the Mother of God that Cistercians would have found resonant with their own values, humility and chastity are salient. Bernard, among others, admired the characteristic of humbleness in her above (or below) everyone else. Another trait of the Virgin that could have exercised special appeal to white monks is her uncommunicativeness. In the Gospels, she is nearly wordless, and in scenes and sermons of the Passion she is frequently sketched as expressing an unvoiced grief. Humility, chastity, and silence are all qualities associated in Cistercianism with lay brothers too.

Without saying so, Our Lady’s Tumbler peels back the overlayer from the self-contradictions of the entire Western monastic tradition, especially as the Cistercians adapted and articulated it. It sets the stage for its audience, whether readers or listeners, to examine many major imponderables of monkish life. To single out four examples, it explores how much conformity to collective liturgy, as opposed to individual worship, life in a monastery requires, how individual seclusion relates to group living and praying, how much asceticism and physical expression of devotion the order calls for or allows, and how much the imperative to obedience within the priorities of such religious societies may be upstaged by allegiance to God and his intermediaries.

Among its other distinguishing features, the Cistercian order has been marked since its very commencement by its fealty to the Virgin. Cîteaux arose in a century that was stamped on all sides by confident dedication to the worship of Mary and unwavering trust in her. Even in a prevailing climate of fevered Marianism, even against a backdrop of such generally intense commitment to the Mother of God, the white monks were second to none. In a letter censorious of their liturgical innovations, the theologian Peter Abelard (d. 1142) commented upon the custom that these brothers maintained in consecrating all their churches to the Virgin. In the same spirit, the seals of most of their abbeys bore her image, first as their mediator with God and later as their special protector (see Fig. 3.4). These emblems, mostly of wax, featured within an architectural canopy in Gothic style an image of the Virgin, usually with Child.

Fig. 3.4 Cistercian seal depicting the Virgin surrounded by devotees. Seal (modern cast from original), ca. 1300–1500. Paris, Archives nationales. © Genevra Kornbluth, 2011. All rights reserved.

Mary was not decreed a queen by the pope until 1954, but the Middle Ages greeted her routinely in that capacity—and that reginal reverence held particularly true for the white monks. An early statute stipulated officially that every Cistercian church and cloister should be founded in honor of the “Queen of Heaven and Earth.” Not the faintest doubt exists that by this formulation the Mother of God is meant. The designation of the Virgin as Queen of Heaven and Earth had been conventional for a long time already. This status positioned her to operate as a unique conduit between the two realms. In an extension of this power, relics of her and of physical contact with her earthly self could also provide petitioners with a pipeline to God and all the holiness surrounding him on high. Madonnas, as images of her, could fulfill the same funneling function.

The Virgin, along with these tokens of her, arbitrated between the simplicity of humble believers in the sublunary realm and the loftiness of God above. She was not unapproachable and unresponsive in her queenliness. On the contrary, she thrust herself forward as mediator. In medieval and theological terms, she came not as an accessory to the crime but as an intercessor for the sinner. The movements involved in Marian intercession were perceived to take place in both directions. Petitions from votaries on earth were relayed to Christ in heaven. Rebounding in the opposite course, expressions of divine grief, joy, and other emotions were transmitted from heaven through visions or animated images. Those celestial feelings could take palpable terrestrial form, with tears, milk, blood, and oil being four of the most common drippings that exuded from the Virgin, especially as represented in Madonnas. In the Middle Ages, virgin olive oil was not at all the same as today.

Veneration of the Mother of God belonged among the paramount manifestations of Christian practice. To go further, it reigned supreme in that same class. Consequently, nothing is strange about the fact that the liturgies of the Cistercians were heavily Marian. Each of the daily offices features a special reflection on her vocation. Since the thirteenth century, each day in a monastery of white monks has been capped by the singing of “Hail, Holy Queen” as the final antiphon. This hymn praises the Virgin in her guise as Mother of Mercy who intercedes with the Lord. It can be difficult to know which personage is meant when a Mary is mentioned within a Cistercian context. A reference to a woman by this name could allude to the historical person, the Jewish woman who was the mother of Christ; to the patroness of the order, ever to be trusted to champion the life- and soul-saving of contrite sinners; to the buildings dedicated to her, especially in this case all Cistercian churches and most cathedrals; or to the mother Church as an institution.

Since 1109, Cistercian monks have not worn the black vestments of the Benedictine order from which they branched off. Rather, they dress in ones of natural, unwhitened, and uncolored wool. The resultant hue is off-white, effectively a beige. For all that, the brethren have tended to be called white monks. In the Middle Ages, they were also known sometimes as gray monks. In either case, they were dyed in the wool for being undyed. Wherever we place the color of the Cistercians’ unbleached woolen habits on the chromatic spectrum, the most common explanation for the adoption of this lightness in preference to black was a specific of Marian symbolism. The color honors Mary’s purity and spotlessness. A hue unblemished by blackness is what immaculate conveys etymologically in the original Latin: unstained and ultraclean.

The Cistercians wore clothing as white as a sheet—a modern and not a medieval one, since bed linens would not have had the incandescence often prized today for its connotation of cleanness. The whiteness betokened not ghostliness or fear, but virginal purity. More than once, they explained the color as bespeaking their service to the bright splendor of the Mother of God. In legend, the change from black to its opposite resulted directly from an apparition of the Virgin. One August morning, Mary made herself visible among the monks as they chanted matins. Not stopping at merely appearing, she went up to the second abbot of Cîteaux and later Saint Alberic, and threw a white cowl over his shoulders (see Fig. 3.5). At this moment, the habits of all the other monks present also turned the same color. The bright cleanliness of Mary makes even more vivid her gesture of having a towel supplied to suck up the saline solution that sluices from the tumbler.

Fig. 3.5 St. Alberic receives the Cistercian habit from the Virgin. Fresco, 1732–1752. Zirc, Zirc Abbey Church. Image from Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Alberic_receives_habit.jpg

Bernard of Clairvaux, who championed the growing cult of the Virgin, has himself been described as Mary’s greatest devotee. Since the eight hundredth anniversary of his death, he has been called the Marian Doctor. By extension, the Cistercians have been styled collectively as missionaries of Marianism. The saint’s principal work of Mariology would be four homilies on the verse in Luke “The angel Gabriel was sent.” These circulated together under the title On the Praises of the Virgin Mother. Other homilies of his deal with Mary too. Bernard’s famous sermons on the Song of Songs identify the betrothed in that book of the Bible as the Mother of God. He articulates his commitment to her in a way analogous to the dynamics of courtly love. He came honestly by his cloisterly courtliness, since before becoming a monk he had been the son of a knightly family. By breeding and upbringing, he was destined to be versed in the culture and ethos of chivalry and chivalric love, with their distinctive ideology and poetry. Perhaps to buff Bernard’s Marian credentials, he was misassigned authorship of texts about the Blessed Virgin in the composition of which he had no hand. Thus, he was often wrongly credited with authorship of a beloved Latin liturgical hymn, “Hail, Star of the Sea,” which honors her. In a further miscue, he is sometimes still supposed to have composed the prayer to her known as the Memorare, while in fact it is apparently from the fifteenth century.

By all accounts, Mary was as favorably disposed toward Bernard as he was toward her. According to many legends, she had a stand-by-her-man loyalty to the holy man. Sometimes statues of Our Lady pumped the affection of the Virgin toward him. Take, for instance, a Madonna in the Benedictine abbey of Affligem, a Belgian municipality. The image reputedly leaned down to receive the “Hail, Mary” of the saint-to-be as he prostrated himself at her feet one day in 1146. In return, she said “Greetings, Bernard.” The legendary episode allegedly prompted him to give the monastery his staff and chalice. This was far from the strangest case in which the Virgin and a Madonna bestowed their favor upon a devotee.

Mother’s Milk

The international advocacy group La Leche League, which took its name from the Spanish word for milk, claims on its website to have been inspired by a statue and shrine to “Our Lady of Happy Delivery and Plentiful Milk.” But Mary’s association with such health and bounty stretches back at least to the Middle Ages. The Virgin is often depicted in medieval images, particularly in paintings, with one breast exposed to feed the infant Jesus. The pose is known in iconography as the nursing Madonna. To judge by the reactions of twenty-first-century students, the most bizarre expression of attachment to the Mother of God may be a story that builds on the motif of nursing. Called the lactation of Bernard, this exchange between Mary and her preeminent Cistercian enthusiast takes filial devotion and recognition to the highest and most heart-to-heart degree. The saint asks to be placed, and is indeed put, on the level of a son sucking milk from the breasts of the Virgin as mother.

Fig. 3.6 Master I. A. M. of Zwolle, Saint Bernard Kneeling before the Virgin, ca. 1480–1485. Engraving, 32 × 24.1 cm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam. Image from Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:StBernardFS.jpg

The accounts, none of them dating from before Bernard’s death, vary in the behavior that they identify as preceding the miracle. In some, the saint prays before a Madonna. This is possible, of course, although he and the early white monks issued pronouncements against images. Furthermore, no statue exists that can be demonstrated to have come from a Cistercian abbey before the thirteenth century. In other versions, the mellifluous doctor sees Mary in a vision. Regardless of what happens first, the aftermath is the same in all the accounts. The saint-to-be requests the Virgin to show herself as a mother. In response, she obliges by projecting a jet of milk from her breast through his open lips (see Fig. 3.6). The jet or droplets endow him with his wisdom and eloquence. Similar motifs surface repeatedly, not only in the twelfth century but even earlier and predictably later. They do not always pertain to Saint Bernard alone. Thus, the Virgin infuses her breast milk into the mouth of her aficionado Bishop Fulbert of Chartres, who promoted in that city the cult of Mary’s tunic. He collects in a vase and treasures three drops that cling to his face afterward. This element in the legend of Fulbert likely became the ultimate inspiration for most subsequent variations on the theme of Marian lactation. Such stories go back to the exemplum known as Roman charity, a very real demonstration that the milk of human kindness exists. In this legendary episode, a woman keeps more than her cards close to her chest: on the sly, she breastfeeds her father to spare him from a sentence to death by starvation.

Later, the feature of Mary’s suckling a devotee spreads. In assorted miracle tales, she comes on scene with her best bedside manner to heal ailing people of one sort or another miraculously, by inviting them to feed at her breast. For instance, one cleric is taken by an angel to the other world, where the Virgin gives him her nipple. Another is saved from a throat tumor after she atomizes his face by spraying it with her breast milk. In a third case, a worshipper of hers is cured of his writer’s block by lactation. By the fourteenth century, the notion that the Mother of God formed this most special union with Bernard in her guise as nursing mother is solidly established among the traditional stories and iconography of the saint.

Mary’s Head-Coverings

The time has come for full disclosure of veiled references. Likewise, the moment is upon us for picking up for the first of many times the thread of an argument about textiles. Bernard was hardly the last Cistercian to do obeisance to the Virgin. To take just one example, Helinand of Froidmont (d. after 1229), himself a former jongleur or troubadour, composed sermons for Marian feasts. In his writings, he declared that his brethren in the Cistercian order “do homage to this great lady and avow everlasting service to her.” If Venn diagrams had existed in the Middle Ages, the categories of Cistercian and Marian would often have come close to total eclipse. The white monks were bound in a privileged rapport with Mary in myriad ways. To rehearse only one more instance, they are often presented in exempla as receiving special guardianship from the Virgin. Her intervention in the tale of the tumbler speaks to the willingness of the white monks to show ordinary monastic authority tempered or even subverted by her maternal power. The Mother of God was permitted to be the exception to the Rule.

In art, Cistercian iconography gives graphic form to the notion of the special favor that the order enjoyed from the Virgin. One type of representation depicts the Mother of God as Our Lady of Mercy. In this capacity, she provided asylum to her faithful beneath her mantle. Before and beyond its strictly Cistercian lineage, the portrayal of “Mary of the Protective Cloak” was due ultimately to Byzantine literature and art. In the tenth century, Saint Andrew the Blessed witnessed a miraculous apparition in the Blachernae church in Constantinople. In this episode, the Virgin cloaked the congregants with her maphorion. A still of her stretching out this veil or robe came to signify the unfailing tutelage that she extended to her devotees. The sanctuary that the Mother of God afforded through her intercessions was celebrated in the liturgical feast of the Veil of Our Lady.

Depictions of Mary’s protection in Cistercian art give the motif a special torque. The diminutive figures who take refuge beneath the Virgin’s garment are all white-hooded monks (see Fig. 3.7). Like a posse of tots clinging to their mother’s shins, they are medieval mothers’ boys who have not the faintest desire to do whatever would have been the medieval equivalent of cutting the apron strings. The motif can be traced back to an episode in the Dialogue on Miracles by the Cistercian monk Caesarius of Heisterbach, eventually repeated by many others. In this incident, a brother had an eschatological vision in which he encountered Our Lady in the afterlife. In heaven, he could not find his fellows. In due course, the visionary queried the Mother of God. In response, she hiked her cloak to reveal the monks, lay brothers, and nuns of the order who were protected beneath it.

Fig. 3.7 Master of the Life of the Virgin, The Virgin of Mercy, ca. 1463–1480. Tempera on oak panel, 129.5 × 65.5 cm. Budapest, Szépmüvészeti Múzeum. Image from Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Master_of_the_Life_of_the_Virgin_-_The_Virgin_of_Mercy_-_WGA14594.jpg

In Our Lady’s Tumbler, the Virgin comes to assuage a lay brother whose sole mode of veneration is his body. In general, the tumbler clings fast to Cistercianism by making purgation and purification of his anatomy a means of penance. That said, his choice of bodily self-mortification is atypical. Yet however much outside the norm the performer’s conduct may fall, for Mary to weigh in and signal her approval is altogether appropriate. Her cult made a priority of the ways in which the very humanness of her physique brought salvation, through pregnancy, childbirth, and nursing. She constituted living proof that the corporeal frame need not be detested as solely sinful. On the contrary, the body could be a vehicle for the expression of goodness and virtue.

The fanning or mopping of the tumbler with a textile belonging to the Virgin may ring a humbler change upon this popular motif. Two exempla, only crudely datable, constitute cases in point. To the best of our present knowledge, they are preserved first in the early 1600s in a book produced by a Jesuit. This volume is itself based on an anonymous collection that was printed first at the end of the fifteenth century, and compiled materials from earlier assemblages of exempla. In one exemplum, Mary appears to the dying in their final throes. With her little kerchief or handkerchief, she dries the sweat of mortality from them. In the other, she ventilates them.

The text of Our Lady’s Tumbler leaves unspecified what the Virgin used to cool her devotee. She is said, with no further explanation, to be holding a cloth. In the French text, the textile is called a white towel. Both the etymology and meaning of the medieval vernacular noun used here are fraught. Touaille could denote a piece of fabric to be carried in the hand or worn on the head, including what we would call a napkin, hand towel, handkerchief, kerchief, veil, scarf, or rag. In Romance languages, the most vigorous living relatives are the Italian for tablecloth and table napkin. As the last two words suggest, the cloth could be meant for household use as well as for personal cleanliness. In English usage worldwide, the noun napkin has bifurcated. The split fossilizes the two potentials within it. It can denote either a sanitary napkin in feminine hygiene, or a table napkin or serviette. But let us not allow lexical semantics to distract us from the physical reality of the object in question. In the bas-de-page with the sole medieval illustration of the tale (see Fig. 1.17), the item in question looks very much like white terrycloth. No one is throwing in the towel, but it is being projected downward from a heavenly thunderhead by a haloed figure, perhaps an angel. The cloth has not come directly from the crowned Madonna and Child nearby, but instead presumably indirectly through their mediation.

Could the fabric be of her own making? Like many women in premodern literature, Mary had an up-close-and-personal connection with textile production in her own life. As a girl, she reputedly dedicated six hours daily to weaving, with a regularity reminiscent of monasticism. More to the point, what is the material? The stuff could be a corner of her veil, the velvety sleeve of her dress, or soft goods of some other sort that would have been on or near her person. A modern viewer not grounded in Christian art may be surprised to realize that the Mother of God is customarily portrayed, particularly in Byzantine and Italian art, wearing a head-covering that resembles the hijab worn nowadays by some Muslim women as an expression of modesty. Often blue, brown, red, or purple, the cloth overspreads the head and chest. While not so extreme as the type of veil called the niqab that covers all the face apart from the eyes of its Muslim wearer, it can still be so extensive as to function effectively as a one-way window. The opposite of a blindfold, it wards off the gaze of others while allowing the wearer to see out.

We may forget that in much medieval art the Virgin typically wore a multipurpose kerchief. Taken by itself, the last word derives from the French phrase meaning “head cover.” As the elements of the compound presuppose, such a fabric wraps around the skull and encircles the face as a scarf. In the kit of textiles and paper goods available to us today, the covering is largely restricted in its use to fulfilling the tasks that the original sense of the term conveys. The many purposes to which headgear could be put are fossilized etymologically in the near oxymoron of “handkerchief.” Parsed element by element, the noun would mean a head covering kept in hand. This item is then a cloth of a size, texture, color, and general appearance that could function as a headscarf or veil. In a pinch, or a sneeze, it could also meet other needs. Along similar lines, a cowboy’s bandana could serve as sweatband or neck-cloth, facemask or dust mask, tourniquet, or all-round handkerchief. It was a one-item ragbag. Nowadays, people will most likely use cloth towels for blotting or wicking away dampness, and disposable plies for facial hygiene. Whatever we call Mary’s fabric, she uses its edge to comfort the man who has danced madly in her honor: it is the lunatic fringe.

In Marian iconography, the jumbo-sized veil is known as a maphorion (see Fig. 3.8). This Greek term designates a head-covering in which noblewomen in Greece customarily enveloped themselves. These ladies were tradition-bound both literally and figuratively. The Virgin’s textile has been equated at different times also to a shawl, mantle, and outer robe. Often represented as a long length of cloth, it not only draped her head but beyond that fell in deep swags down her arms and chest to her knees or even ankles. One color renders the fabric Virginal: if blue is present, the dye is cast. In representations of the oversized veil, the garment is decorated at Mary’s forehead and shoulders with four pellets, positioned to suggest a cross. Later in the Middle Ages, the points were sometimes made stellar. Such foursomes of dots around stylized crosses may be discerned in the background of the miniature to illustrate the miracle in the story of the tumbler. The Mother of God was often associated with stars, but usually singly or in threes, to represent the threefold nature of her inviolate virginity. The unstated message of the four-star iconography in all cases may be that the Nativity led continuously to the Crucifixion, which brought salvation to humankind.

Fig. 3.8 Virgin and Child enthroned between angels. Mosaic, sixth century. Ravenna, Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, north wall. Image from Wikimedia, © José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro (2016), CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Madonna_and_Child_-_Madonna_and_Child_between_Angels_mosaic_-_Sant'Apollinare_Nuovo_-_Ravenn.jpg

The maphorion serves multiple uses. Veneration of relics was deeply ingrained in medieval Christianity. After the Virgin’s death, the length of material doubled as her shroud. As Mary’s body was never found on earth, her grave-clothes became powerful for the immediacy that they granted to the purity and incorruptibility of her last corporeal presence before her Assumption into heaven. Such contact relics enjoyed lofty prestige and occupied a place of special privilege in the cult of Mary, since they granted the closest possible approach to an otherwise altogether absent body: they gave it a common thread. By a very easy to use and apply principle of transference, the fabric embodied her materiality. At the same time, the lack of bodily remains helped to make the Virgin the most universal among saints. She became present everywhere, capable of performing miracles anywhere.

However we translate the Greek term, the textile in question was believed to have been found in the Holy Land at the latest in the fifth century. Initially, it was transferred, along with Mary’s girdle, to a church in Jerusalem; later, the cloth was moved to Constantinople, where it belonged to the glitz and glamour of the many major Marian relics possessed by the great capital city. The fabric was showcased in a chapel close by the seacoast that the Byzantine emperor and empress Leo I and his wife Verina added to the Church of the Blachernae. Together with the icon known as the Great Panagia, or “All-Holy,” the maphorion perished in a fire that destroyed the church in 1434, not even two decades before the fall of Constantinople in 1453. The waistband, ostensibly dropped as a token by the Virgin as she ascended from earth, survived the conflagration. It was preserved in a church in the Chalkoprateia quarter of the Byzantine metropolis, near Hagia Sophia.

A tidal wave of Byzantine influence struck Latin Christendom in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Roman Catholics were immensely indebted to Eastern Marianism in things plundered, purchased, and imitated, as well as (to a degree) in practices emulated and replicated. Byzantium contributed substantially to the fascination with cloths and clothing connected with the Virgin in the cult of Mary in the medieval West. During the Crusades, ever more travelers had opportunities to see and hear of such relics. After the looting of Constantinople in 1204, many such valuables were carried to the West, or at least the claim was made that they had been taken there. In ways that warrant much further inquiry, the treasure trove of Marian textiles was greatly expanded by contact between the crusaders and the Byzantines. But the Fourth Crusade was not the very beginning. The acquisition of fabrics pertaining to the Mother of God had begun even earlier.

The Church developed a vested interest in textiles of the Virgin. Mary was associated with many types of cloth, such as girdles, corsets, sashes, and veils. No pains were spared in procuring them, through diplomacy, trade, despoliation, theft, or manufacture. The most famous, the object of a flourishing relic cult, was undoubtedly the chemise, camisole, or “interior tunic” of the Mother of God at Chartres. Charlemagne acquired this trophy in the Holy Land. After he brought the precious item back to France, four armed sentinels guarded it twenty-four hours a day. The actual garment, by all accounts worn by the Virgin on the night she gave birth to Christ, was seldom seen directly but was depicted nonstop on locally produced leaden badges. These little images of the chemise were known by the diminutive “chemisettes.” The tokens were purchased and taken away by pilgrims to Chartres as travel trinkets, as proof and reminder of their visits. Another major item, sometimes identical and often confused with the chemise, was Mary’s veil.

One of these cherished fabrics occasioned a brouhaha at Chartres after a blaze in 1194. When the old cathedral was destroyed in the raging fire, this famous former possession of the Virgin’s was thought to be lost. Days after the all-clear was sounded, the prize was found by a rescue team and unearthed from the crypt. Along with a few monks, it had been interred there beneath rubble. Thanks to Mary, both the treasured thing and the pious people had been kept safe and sound. The poet of Our Lady’s Tumbler may have lived near a site with a relic of such a fabric. In that event, the poem may have helped to promote a cult associated with the cloth. The place need not have been Chartres, or for that matter anywhere else named in this book.

Mary’s intimate apparel was often the focus of intense devotion from women who hoped to have a healthy childbirth at the end of uninterrupted pregnancies. Somewhat contrarily, a spotless towel, symbolizing purity, is also a Marian attribute. At times, the Mother of God is portrayed cuddling her divine infant in her lap with a linen blanket or handkerchief. The most influential image of her along these lines is the Virgin and Child from around 867 in the mosaic apse of Hagia Sophia (see Fig. 3.9). This representation belongs to the Byzantine genre known by the Greek epithet Theotokos, or “God-Bearer.” Because of Mary’s immaculateness, an undyed towel made an ideal symbol for her. Many textiles connected with her were reputedly without seams, in keeping with the seamlessness of her body. Her very physical structure as a living human being was a garment in which Jesus had been clothed. As his mother bore him during her pregnancy, so he wore her as a covering.

Fig. 3.9 Virgin and Child enthroned. Mosaic, ninth century. Istanbul, Hagia Sophia, apse semidome. Image from Wikimedia Commons, © SBarnes (2007), CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hagia_Sophia_Interior_Virgin_2007.JPG

If the trading in objects relating to Mary was heavy, ideas and stories flowed even more abundantly. The Virgin was an unica, but she came in almost as many forms as there were believers. The same observation holds true today as well. Both laymen and churchmen cherished her, but often very differently. The tumbler’s simple and unlearned attachment typifies what might have been encountered within a parish church, or even in the fields among country cousins. His determination to express his love through a solitary and purely physical ritual of his own making runs counter to monastic norms and rituals in all ways except frequency. Remarkably, his teeth-gritting mode of devotion outperforms all that the brethren do in the choir above him. The uneducated but passionately sincere lay brother smuggles his own peculiarly efficacious reverence for the Mother of God into the theologically more rarefied ambience of a Cistercian abbey. Now let us scrutinize the relationship between choir monks and lay brothers.

Cistercian Lay Brothers

No good deed goes unpunished.

While Cistercians sported white habits, as distinct from the black ones worn by Benedictines, the two orders differed from each other in much more than the mere tint of their attire. Rather, they were distinguished by their attitudes toward the elemental injunction in the Rule of Saint Benedict to pray and work. The twofold imperative raised a very real challenge that put monks in jeopardy of being neither fish nor fowl in the fauna of faith. On the one hand, the obligation to prayer could be construed as service to God; on the other, the injunction to toil could be regarded as furnishing ministrations to the world. The disharmony between the two activities is self-evident. Christ, to quote a law unto himself, said clearly, “No one can serve two masters.” As a category, then, the lay brothers within the Cistercian order rendered perfect service to neither God nor the world. How imperfectly they fulfilled their duties could be a cause for sarcasm. The German Benedictine nun Hildegard of Bingen (d. 1179) was only one of many in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries who engaged in wordplay by positing that Cistercian converts were intrinsically perverts.

By the time Our Lady’s Tumbler was composed, lay brethren were probably no longer at their high-water mark in numbers. Even so, the poem could have served not so much to proselytize for fresh-faced recruits to join their ranks as to remind the choir brothers of better days. In earlier times, newcomers from the laity had endued the monastic society with a devout simplicity. Later, the white monks may have worried that the same quality was being eroded by the twinned processes of clericalization and secular learning. The unlearned piety of lay brothers in the heroic age of the Cistercians would be preferable any day! At that point, the order was engaged in a boundary-pushing experiment in social engineering by bringing in laity to the extent that they did. The monasteries were not classless, but they tried at least to be egalitarian.

From the abbacy of Alberic around 1120 on, the Cistercian order, as also later the Carthusians and Grandmontanes, relied extensively upon lay brothers. These members of the institution furnished a creatively drastic solution to the tension between prayer and work that had pervaded cenobitic monasticism since its establishment. They took vows of chastity, poverty, and obedience, yet rather than concentrating upon chanting the hours, they funneled their energies toward manual, and usually agricultural, labor. In fact, they were strictly forbidden from becoming choir monks. At the same time, lay brethren were not altogether devoid of monklike obligations. For example, they were bound to the punishing Cistercian custom of silence, the white noise of the white monks. Most notably, they followed a simplified version of the office that they could enact while at work. Under the circumstances, their reputed proclivity to sleepiness is understandable. Run-down from physical toil and unable to parse the language and semantic code of the liturgy, they would have had good reason to grow heavy-lidded and to doze when they were constrained to sit in wordless stillness and attend the office in the monastery’s chapel.

Fig. 3.10 Cistercian monks and conversi before the Virgin. Miniature. Wrocław, Biblioteka Uniwersytecka, MS IF 413, fol. 145r. Image courtesy of Biblioteka Uniwersytecka, Wrocław. All rights reserved.

In physical appearance, lay brothers were differentiated from choir monks by a few distinct features. The main item in their clothing was a cloak or mantle, which in all likelihood lacked the cowl that betokened monastic status. The tumbler bore such a garment. In addition, lay brethren had no tonsure, a glabrous patch on the scalp where the hair was clipped or shorn. This characteristic haircut was a token of belonging for those men with clerical or monastic status. It signified imitation of the apostles. Much like a passport today, it entitled its bearers to a specific legal and civic status within society. Finally, lay members wore facial hair of not more than two fingers in length (see Fig. 3.10). The last characteristic led often to their being called “bearded brothers.” Not exactly groomed for success by not being close-shaven, they were clean-cut only in a metaphorical sense.

As mentioned, lay brothers took vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. Paradoxically, they were described as the equals, in everything except monkhood, of those who sang beyond the rood screen. The proviso of not possessing this status meant that the laity had no hope of being admitted to the ranks of the choir monks, who towered above them in the monastic hierarchy. They were not required, either before or after entry into monastic life, to be conversant in Latin, song, or the liturgy. Accordingly, it is altogether consonant with actual practice and reality that the lay brother in Our Lady’s Tumbler cannot chant, read, or understand Latin. He is excluded from the sociolect of the full brethren; rather than being simply a different dialect with its own jargon, the tongue they speak is a distinct language from the vernacular that he employs. In many respects, he makes himself incommunicado. This illiteracy means that most, if not all, Latin exempla about lay brothers reflect the viewpoint of the choir monks, who presumably had many preconceptions about them, not all complimentary. Thus a distinction between elite and nonelite, choir monks and lay brothers, was baked into Cistercian monasticism.

Like education and culture, ignorance and stupidity are all too often conflated. Thus the mostly analphabetic lay brothers were wrongly assumed also to be simpleminded morons. In the Latin Middle Ages, not knowing Latin, being unlettered, and lacking formal education were regarded as intimately related and often interchangeable weak points. In modern European languages, the consequences of the interrelations among these categories remain enshrined in etymology to the present day. On the one hand, idiots are conversant only in their own idiom or speech. By their very nature, they are bereft of access to the schooling available in the learned tongue. On the other, even the unintelligent deserve acknowledgment for belonging within the Christian community—despite suffering intellectual deficiencies, the cretin, as its etymology indicates, is a Christian and not a non-Christian human being or even a beast.

The simplicity of lay brothers could cut two ways, leading in one direction to sanctity and in the other to sheer folly. At times their simultaneous paucity of secular learning and plenitude of unpretentiousness could call to mind lay heroes of early monasticism, such as the desert fathers. Simplicity in this sense was a good thing, the opposite of duplicity and double-dealing not merely etymologically, but also semantically. A simple person was undivided, whole, and integral—everything but two-sided or two-faced. At other junctures, the undevious nature of lay brethren elicited snobbery from Cistercian abbots, and instead of administering care and oversight, they sneered. The order made its eagerness for recruits, including those who became lay brothers, a point of pride. Accordingly, the superiors of the monasteries were obliged to be evenhanded in dealing with new entrants incoming from lower social classes. They accepted the recruits, warts and all. The obligation went beyond mere administrative responsibility. In fact, it rose to a matter of spiritual life and death, since on the Day of Reckoning the monastic head was expected to render account for the monks in his charge.

What is meant when the protagonist is called a convert, in this case using the French singular? The term does not imply just that he has converted to monasticism and is on course to being accepted eventually as a fully developed choir monk. Rather, it signifies that he has been permitted to join as a lay brother. The innovation of this special subset among the white monks raises a host of issues. The word’s horizon was far more spacious than even the spread between the two preceding usages would suggest. Complicating matters, the Latin equivalent (and original) enveloped its own partly distinct semantic sweep. Furthermore, the reputation of the “convert” covered an even more imposing span, from a presupposition of humble holiness through suspicions of unseemliness.

To oversimplify, let us pose four questions, without seeking to answer them right now. First, was a conversus, a lay convert in Latin, or convers, to use the corresponding but not exactly congruent French singular, a second-class citizen within the Cistercian context? That is to say, was he generally a Latin-less rustic of innately inferior status who was exploited for physical labor by monks who were his social superiors? Second, was he typically a bread-convert? That is, did he take up the burdens of his lot within (or without, as the case may be) the cloister mainly as a precondition to receiving a daily dole? (By becoming a lay brother, the typical twelfth-century peasant would have left behind the bottom of the hardscrabble feudal world and the elusiveness of a regular per diem of food. It is imaginable that the destitute would have been drawn by the magnetism of board and lodging in return for work, according to the same terms offered centuries later in workhouses.) Third, was he of markedly higher social and economic class than his blinkered education and culture might lead us to believe? In other words, could he have been unliterate, un-Latinate, and therefore more surely rooted in popular religion than in the Latin-based liturgy and theology, while possessing enough wealth to have been stung by the price of admission? (The Cistercians required lay brothers to forswear property.) And, fourth, if the manual labor of lay brethren in the agrarian work of the granges and fields was sanctified, what of other physical expressions of devotion? How much of a thorn in the side was it, during the salad days of what might be called lay Cistercianism, to winnow permissible from impermissible physicality in worship? Could Our Lady’s Tumbler speak to the crosscurrents of a dispute within the order over the very nature of piety?

One feature lay brothers shared with full-fledged (or full-habited) choir monks was the fervor of their fidelity to Mary (see Fig. 3.11). Their adoration stands to reason, since in countless miracle stories the Mother of God was touted for her charity toward unchaste nuns and priests, light-fingered thieves and scoundrels, and other sundry reprobates. The tales showed her again and again in her guise as Lady of Mercy, rescuing from eternal fire and brimstone, perhaps especially at their deathbeds, individuals who had little or even nothing in their favor apart from their allegiance to her. Even that faithfulness might have been shown to her only fleetingly, perhaps just lately. Yet in the ultimate crisis of salvation or damnation, the Virgin intervened to ensure that in the weighing of souls, the balance tipped toward those faithful to her. This motif appears in Our Lady’s Tumbler, following upon the description of how after his death, when his body is laid out in the church for last rites and he lies in repose, the lay brother is treated as a choir brother would be.

Fig. 3.11 The adoration of Mary. Stained glass window, ca. 1280. Wettingen, Kloster Wettingen, cloister, north walk. Image courtesy of Swiss National Library. All rights reserved.

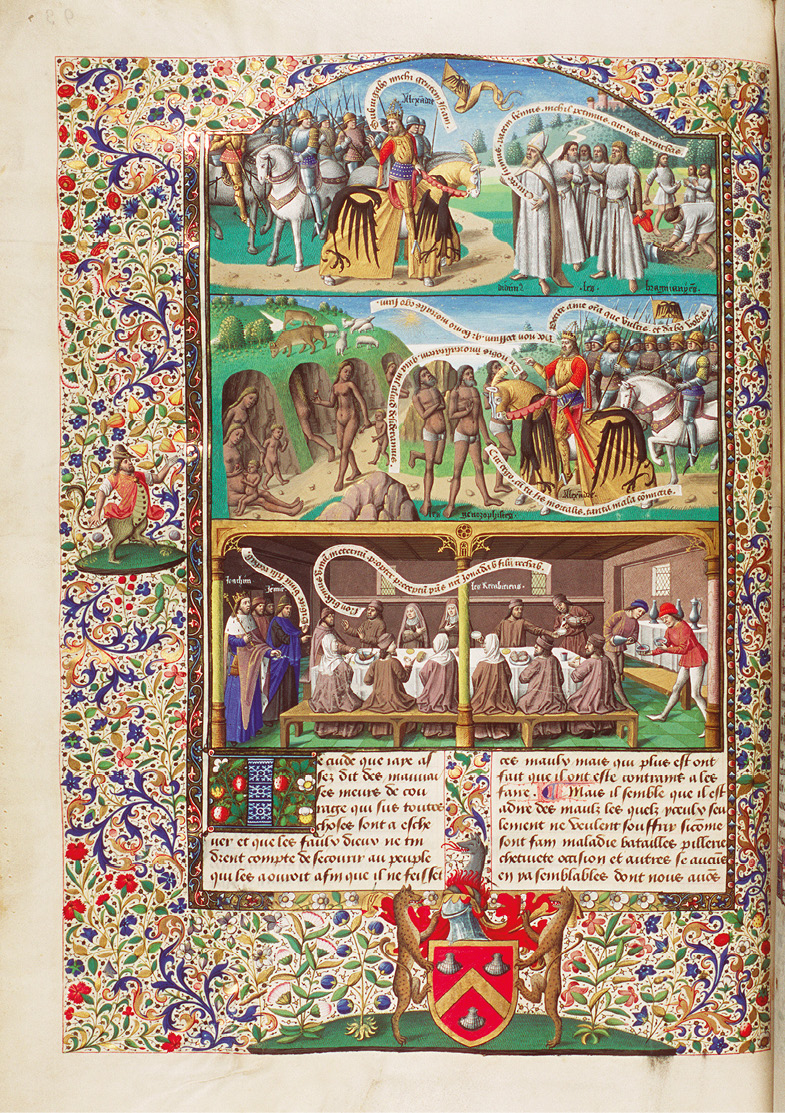

The largest and most ambitious omnium-gatherum of Cistercian stories is Conrad of Eberbach’s The Great Beginning of Cîteaux. In the 1180s and 1190s, when the great monastery was evidently a hotbed of creation and exchange for exempla that pertained to the genesis of the order, its author spent time at Clairvaux. Conrad’s compendium is notable for arranging its illustrative anecdotes in a logical structure, and for making their morals easily identifiable to readers. The fourth book offers numerous narratives that recount the divine favor shown specifically to lay brothers. Miracle tales about brethren of that sort were ideal for the genre, since the stories graph intersections between learned and lay, clerical and secular, and literate and illiterate. The centrality of liturgy in the miracle of Our Lady’s Tumbler suggests that the tale took shape when the nature of veneration within the cult of Mary was developing and being negotiated, perhaps in novel directions. Such creative haggling was under way throughout Europe, but early Cistercian foundations such as Cîteaux and Clairvaux saw as much of it as anywhere. They lived through what was tantamount to a heroic epoch in Marianism.

One anecdote in Conrad’s text tells of a devoted lay brother who was obliged to tend a flock of sheep and therefore to miss the services for the vigil of the Assumption of the Virgin. In place of the formal liturgy, he recited the few prayers to Mary known to him. At least through the mid-twelfth century, converts were expected to know by heart only the Our Father, Apostles’ Creed, and Psalm 51. These three texts were their spiritual survival kit. By the time of Our Lady’s Tumbler, circumstances had not altered radically. “Hail, Mary,” the hymn in the learned tongue based on the angel Gabriel’s salutation to Mary, might have been added, but throughout their existence, most lay brothers remained innocent of Latinity. To the tumbler, even the paternoster—the Lord’s Prayer in Latin—seems the esoteric stuff of higher learning. Lacking the ancient language does not dishonor a conversus within the monastery or order. In the exemplum that Conrad relates, Bernard of Clairvaux himself was so impressed by the fervor of the lay brother who privileged his shepherding over the office that the saint incorporated the incident into a sermon as a lesson in obedience.

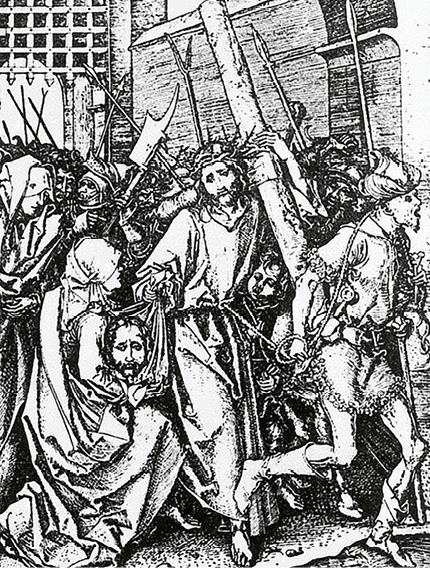

In 1223, Caesarius of Heisterbach completed his Dialogue on Miracles (see Fig. 3.12). In format, the text pairs a tyro who poses questions with a veteran monk who responds. The situation was well known to the author, who served as novice-master for some years in the monastery. The fictitious exchange purported to purvey actual spoken interactions recorded by Caesarius, as rapporteur. As such, the work was well positioned to draw upon both written and oral sources. The 746 medieval miracle stories were assembled a half century after the magnificent flowering of Cistercian exemplum literature began at Clairvaux.

Caesarius’s extended conversation contains scores of tales in which lay brothers come on the scene. In most, these brethren elicit favor from God. The seventh book of this major collection is given over to miracles of the Virgin and relates more than five dozen visions of her. It includes an account of a conversus named Henry, from the cloister of Himmerod in Germany, who experienced a number of sightings of Mary. In one, he saw her enter the infirmary and bless invalids as they languished on their sickbeds. In another, he looked on as she materialized in the separate choir of lay monks, where she lingered before the devout but passed by the sluggish or drowsing. In every case, the visionary, whether a priest or cleric, lay brother, knight, or woman, is alone in discerning the Mother of God at the time of the apparition. Although the status of lay brethren varied from period to period, it was never automatically or intrinsically second-rate. The converts were not so much marginal as medial, going back and forth between clergy and laity.

Fig. 3.12 Benedict of Nursia (left) and Caesarius von Heisterbach (right). Miniature, early fourteenth century. Düsseldorf, Universitätsbibliothek Düsseldorf, MS C-27, fol. 2r.

Conversion Therapy

In the Middle Ages the Latin noun conversio designated simultaneously retreat from the secular world and consecration of a spiritual life to God, within either the isolation of a hermitage or the community of a monastery. Consequently, it is not at all preposterous that a man such as the tumbler would be attracted to the notion of becoming a lay brother. Medieval historical sources and literature bristle with portrayals of jongleurs who convert, particularly late in life, to become hermits or monks. In the twelfth century, converts who elected to spend their last-chance final years among the Cistercians hailed from many slices of society. Rulers, noted laymen from various professions, and ecclesiastics from priests through abbots to primates—individuals from all these ranks and callings took on the habit of white monks.

In the Latin Lives of the Fathers, the Egyptian desert father Paphnutius, who had been a disciple of Saint Anthony, is said to have converted a jongleur who had already become esteemed for his good deeds. A tradition attested from the early twelfth century held that such an entertainer built a hermitage dedicated to the patron of his native town. In turn, the site on a hill known as Publémont became the center of an abbey in Liège, in what is today Belgium. The late twelfth and thirteenth centuries provide numerous cases in which a performer saw the light and converted. Quasi-legendary would be the short life entitled The Monk of Montaudon (see Fig. 3.13). The man in question enters (no surprise here) a religious foundation at Montaudon. He subsequently becomes head, first of this otherwise unidentified priory and later of another near Villafranca in northern Spain, in the province of Navarre. Reportedly, he composes poetry but gives what he earns to his monasteries. Eventually, the monk is released from his vocation to join the court of King Alfonso II of Aragon, where he is appointed lord over the poetic society of Puy-Saint-Mary at Le-Puy-en-Velay. Sadly for our purposes, Saint-Mary has no relation to the Virgin: no tangible Marian connection is to be found. In other well-documented instances, poets and other entertainers converted to monasticism, including Cistercianism. A shining example would be the famed troubadour and later fanatic in the anti-Cathar Crusade, Folquet of Marseille. He disavowed his profession, repudiated his poems, torched the texts of them in his personal possession, and became a Cistercian. Eventually, he was elevated bishop of Toulouse (see Fig. 3.14). His songs included a dawn song in praise of the Virgin that Pope Clement IV, himself a former troubadour, certified. Folquet’s conversion was itself made the stuff of an exemplum.

Fig. 3.13 The Monk of Montaudon. Miniature, thirteenth century. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS Fr. 854, fol. 135r. Image courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

Fig. 3.14 Folquet de Marseille. Miniature, thirteenth century. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS Fr. 854, fol. 61r. Image courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

A robust list can be constructed of other troubadours who became Cistercians. To take another instance, a man known as Guiot de Provins lived at the turn of the twelfth to the thirteenth century. While young, he studied in Arles and elsewhere in Provence. After serving as a court poet and composing love lyrics, he became a white monk at Clairvaux, but he was not there to stay. He left his life as a trouvère definitively four months later to enter Cluny. At the beginning of 1206, twelve years after taking up the habit, he completed the social satire known as Bible Guiot, or “Guiot’s Bible.” The roll call does not end with Guiot. Far from it! Helinand of Froidmont also put his career as a minstrel behind him to become a Cistercian at the monastery from which he takes his name. Jean Renart, the thirteenth-century author of the Old French romance Guillaume de Dole, may also have finished his days in an abbey. Perhaps the most pertinent of the many virtuosi among lyricists who converted to Cistercianism is the thirteenth-century Adam of Lexington, from Melrose in Scotland. To honor the Virgin, he passed his winter nights in playing the lute and singing before her altar in the abbey church. The Scot was an antibusker who would hand out provisions to others rather than solicit alms for himself. To give the gritty (or at least grainy) details, he would take a seat near the church doors and pore over the psalter with a basket of bread at the ready to allot to the helpless and needy.