4. Reformation Endings: A Temporary Vanishing Act

© 2018 Jan M. Ziolkowski, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0132.04

What Makes a Story Popular?

Mind the gap.

—Warning phrase on the London Underground (1969–)

Our Lady’s Tumbler has been described in ways that make its narrative seem anything but time-bound. Yet the timelessness has hardly been unqualified and unobstructed. As it turns out, the narrative has not been immune to the repercussions of cultural change. For as much as one half millennium, it apparently went unrepeated in any form—untold, unsung, unpainted, and unwritten. In all candor, the tale underwent a death and long interment, before the investigators of literary history exhumed it and reactivated it inside the Frankensteinian operating theater of philology. From there, artists, especially an author, a composer, and a diva, wheeled it out on its gurney for recuperation and rehabilitation so that it could reenter the world triumphantly once again, as a kind of medieval revenant. Never count this story out: each time the jongleur has pulled a vanishing act, he has popped up again—a humanized bolt from the blue, a loose cannon in the literary canon.

What makes a tale gain or lose popularity? Many storytellers, whether oral poets, dramatists, or screenplay writers, have wrestled with this question, and laid bets on the answer. Some have elected, or at least professed, not to care. In the case of Our Lady’s Tumbler, we must wonder why a narrative would enjoy modest success for a couple of centuries from around 1200 before vanishing from sight for roughly five hundred years. Despite being anything but a hollow man, the gymnast went out not with a bang but with a whimper. In the late Middle Ages, he performed a centuries-long disappearing act.

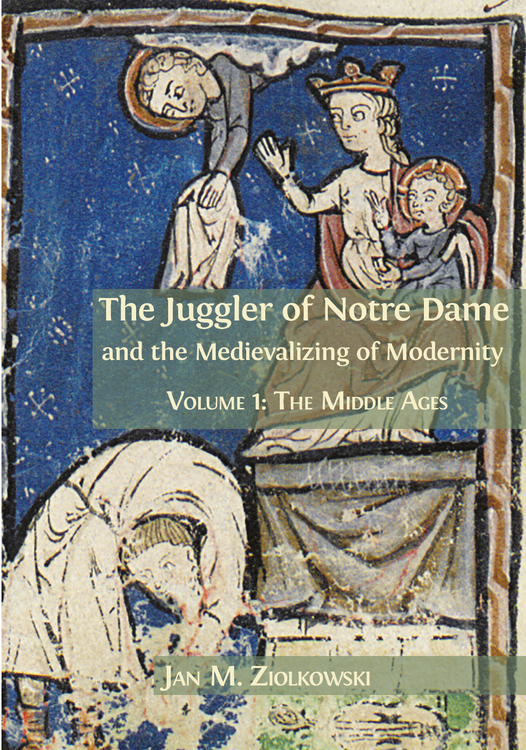

Terms and phrases such as “Our Lady’s Tumbler” and “Jongleur de Notre Dame” may now be keyboarded into search engines. Algorithms enable nearly instantaneous trawls through corpora of digitized texts that encompass a restricted but still meaningful fraction of all writings published in English over the past two centuries. The quantity suffices for generating line graphs that track the relative frequency of both titles across time (see Figs. 4.1 and 4.2). The results show visually the diachronically rising and falling cultural impact of individual translations, literary and musical compositions, performers, and more. With the help of such graphic aids, we can correlate upward and downward spikes. We can map the increasing and decreasing effects of translations into modern languages and other artistic developments, such as Anatole France’s adaptation, Jules Massenet’s opera, and Mary Garden’s arrogation of the leading role in the opera to herself. When comparable tools become available for data mining in earlier bodies of literary resources, what patterns will the ripple effects reveal to us? So far as is now known, only two versions of our story survive from the Middle Ages. The French one bears a different title in each of the five manuscripts. Our textual repository could swell slightly with the discovery of a new version or two, and I would not be surprised if someday a hitherto-unknown exemplum came to light. In the much-quoted words of Alexander Pope, hope springs eternal. Yet even in the most felicitous circumstances, we will never possess enough medieval evidence of Our Lady’s Tumbler to permit credible statistical analysis. The margin of error is too high. Literature from long ago does not always even allow the geometric certainty that two points determine a line. Words may be made into big data, but in the end, poetry and story—like all art—defy datification.

Fig. 4.1 Google Books Ngram data for “Jongleur de Notre-Dame,” showing a sharp rise in the first decades of the twentieth century and then a steady decline. Vector art by Melissa Tandysh, 2014. Image courtesy of Melissa Tandysh. All rights reserved.

Fig. 4.2 Google Books Ngram data for “Our Lady’s Tumbler.” As with “Jongleur de Notre-Dame,” the phrase peaks before 1920; unlike “Jongleur,” the decline is more fitful, dropping deepest only after 1980. Vector art by Melissa Tandysh, 2014. Image courtesy of Melissa Tandysh.All rights reserved.

The thin dribble of the narrative into written culture before the Reformation indicates much in its own right. Even before the first millennium, Marian miracles were established in Byzantium. These tales became archetypes on which subsequent adaptations were based in the West. The more different the versions in circulation, the less likely a story was to ebb away altogether, either permanently or temporarily, without being retrieved and reanimated. In contrast to the French poem, we have only two versions of our Latin narrative, the one in a very cursory exemplum. The exiguity of transmission made the survival of the story insecure.

Rather than seek vainly for information that pertains specifically to Our Lady’s Tumbler, we would do better to probe by comparison and analogy what we can learn from the sizable medieval literature of Marian miracles. The distribution of this trove across regions, languages, and literary traditions may procure at least some enlightenment. We discover speedily that the impetus toward collecting miracles ran particularly strong in England in the twelfth century. Yet it did not evidence itself commensurately in the mother tongues. In fact, the meager residue of miracles of Our Lady in medieval English and Anglo-Norman pales alongside the multitude in Anglo-Latin versions and even alongside ones in other Western European vernaculars.

The outpouring of literature, at its most intense from the late twelfth through the thirteenth century, matched a devotion to Mary that cut across geographical, linguistic, and social boundaries. Around the time Our Lady’s Tumbler was set down in writing, Louis IX ruled as king of France. His piety was legendary, and he was canonized in 1297. With good reason, he is commonly designated merely as Saint Louis. Every day he heard the offices of Our Lady. On Tuesdays and Saturdays, the Mass was dedicated to her. On the vigils of the four principal feasts of the Virgin, the king would mortify his flesh. Two of the six times a year on which he took communion were feasts of Mary. Finally, he made pilgrimages to Marian shrines such as Chartres and Rocamadour.

The Middle Ages and early modernity overlap in multiple ways. The periodization that differentiates between them deserves to be tested and refined. In fact, it has been so sharply faulted that some would favor scrapping any hope of a meaningful division. All the same, the two periods still constitute distinct time zones in the evolution of European culture. Many systems rest on gradations that can be at variance, but even so we rely upon them. In this case, the separateness of the medieval and early modern worlds appears strongly in religion, not only in those regions where Protestantism threw down the gauntlet to Catholicism.

During the Reformation, the whole world of faith implied in Our Lady’s Tumbler was desecrated and deserted, deteriorated passively from dereliction, endured active destruction, or underwent some composite of such sea changes. In England, one important aspect of the dismantling has become known formally as the dissolution of the monasteries. In the late 1530s, close to one thousand Catholic religious houses were disbanded at the instigation of King Henry VIII. Among the manifold consequences, much of medieval material and textual culture hung by a thread or was even lost. In many places, the iconoclasm of the switch in religions obliterated imagery that had accumulated for centuries. In architecture, the outcome was what Ralph Adams Cram, an early twentieth-century American apologist for the preceding medieval culture (and pre-Reformation Catholic religion), could describe as “the eviscerated, barren, and protestantized cathedrals.” Thus, a reality wrought by Reformation and civil war prompted William Shakespeare to allude to “bare ruin’d choirs where late the sweet birds sang.” Throughout England, the churches of monasteries and abbeys were dispossessed and devastated in rapid-fire succession, with the disappearance of both the physical trappings of Catholic Christianity and the human presence of chanting monks.

True, the changes took hold to varying degrees in different locales. The baring and the ruining were not ubiquitous. In fact, the spectrum could be large within a country such as Germany where a geographical division emerged between Catholics and Protestants. For all that, in general Protestantism of the time acquired an anti-Marian accent. Concomitantly, the Reformation had the effect of diminishing the prominence of the Virgin in Christianity. Even in what remained a mainly Catholic region such as France, medieval culture came under a cloud. More than buildings were affected. In confronting the cult of the saints, the reformers felt bound to reshape or eradicate shrines, relics, images, and miracle tales. Protestants were anti-pilgrimage. A logical extension of the same compulsion was to obliterate the narratives underpinning them. Those who disavowed Catholicism had to confront and calumniate all these interrelated phenomena without granting a special dispensation for the worship of Mary. The Mother of God was not given a free pass in the sectarian violence—on the contrary.

Protestant zones, and Catholic hot spots located close to the battle lines between the factions, came to the boil. It became increasingly dangerous there to claim to have witnessed a Marian apparition. The wrath of the Inquisition could be threatened, and supposed visionaries were executed. At the same time, the cultures that came to be bracketed within the catchall designation of the Middle Ages became suspect too. Afterward, it took a long time to overcome the lingering reserve and even disdain for the period. By the seventeenth century, French highbrows could be found who expressed admiration for medieval times and affinity for its literature. But their attraction skewed toward knights and the major protagonists of heroic poetry, not toward monks and monasteries.

The most intemperate reformers in England, Germany, and elsewhere, such as Calvinists, were intent on extirpating from popular culture and discourse all saints, but foremost among them the Virgin. They challenged the extremely slender scriptural, and in fact primarily apocryphal, evidence undergirding some of the beliefs and worship that had burgeoned around Mary. They paid the mother of Jesus her due as the Mother of God, and recognized that she conceived as a virgin, but they emphasized more vehemently than the Catholics the preeminence of Christ, and they denied that the Virgin had escaped from original sin. To accord Mary more attention was Romanism, papism, and idolatry.

The Mother of God had been associated especially with lilies, but now the flower show was over. After being in full bloom in the late Middle Ages, the plants were fading fast. The second of the Ten Commandments enjoins the faithful from worshiping graven images. Out of antipathy to idols, the reformers systematically uprooted, tore asunder, and even incinerated the traditional cult and images of Mary like so many overgrown weeds.

This recrudescence of iconoclasm within Christianity deprived the faithful of the direct engagement that Madonnas facilitated with the characters and events of the New Testament. At the same time, it ruled out the danger of ignorant believers becoming confounded and regarding the objects themselves as inherently divine, rather than as stepping-stones toward the divine. Along with the Virgin, the rabble-rousing reformers got rid of monastic orders, many of which had cherished a special devotion to her. Where monasticism was outlawed, monasteries fell into abeyance and monks disappeared. Additionally, the reform movement contributed to the demise of jongleurs, not because of Mary but because the leaders of the Reformation harbored general reservations about entertainment and art of all sorts. The reformers were antitheatrical and therefore perforce antijongleur.

English Protestants, whose religion acquired the backing of the state, achieved success in their full-force and head-on assaults on the cult of the Virgin. England had bestowed upon the Mother of God a favor second only to that for Christ himself; in fact, the entire country had earned recognition as “Mary’s dowry” in acknowledgment of its especial devotion to her. Two and a half centuries earlier, a bishop of Exeter had mandated that every church in his diocese should contain an image of the Virgin, but now Madonnas incurred acute risk. Depictions of her and of other saints caused consternation because of their anthropomorphism. The importation of the Italian madonna, or “my lady,” to designate a picture or statue of Mary is attested in England first in 1644, well after Protestantism had asserted a firm grasp there. By then such images were alien and foreign. They were talismanic, objects possessing extraordinary powers, whose veneration was dissonant with the anti-idolatrous and antisuperstitious tenets of Christianity.

In the fundamentalist process of editing the Virgin back to the rather faint contours she had in scripture, the iconoclast reformers felt obliged to wipe out the images of Mary around which para- and postbiblical traditions had ramified into a primordial jungle. Wooden figures of the Mother and Child, enclosed often in tabernacles, were a fixture of most English parish churches, as medieval inventories confirm. Of all these numberless Madonnas, only one from the early thirteenth century has survived. A particularly painful episode to contemplate is the iconophobic (or miso-iconic) vandalization of the Lady Chapel attached to Ely Cathedral (Fig. 4.3). Today the space is strikingly austere, its niches bald of statuary. The sole representation only accentuates both the neat-as-a-pin beauty and the unrelieved bareness. In 1541, reformers beheaded nearly all the dozens of brightly colored statues and smashed almost every single stained glass window that illustrated the biblical typology of the Mother of God and her life story. In 1643, William Dowsing, as commissioner with the charge of destroying “monuments of idolatry and superstition,” carried out a further round of iconoclasm, with close attention to image of the Virgin Mary.

Fig. 4.3 Lady Chapel, Ely Cathedral. Photograph by Max Gilead, 2010. Image from Wikimedia Commons, © Maxgilead (2010), CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:DSCF0563,_UK,_Ely,_Cathedral,_Lady_Chapel.jpg

Another notorious episode took place in England in 1538, when zealots effectively imprisoned cult statues of the Virgin in a large storage closet known as Thomas Cromwell’s wardrobe of beds. Eventually, they put these images on trial. The reformers were not swayed by the defense mounted on behalf of the admittedly tight-lipped sculptures. Instead, they publicly executed them by burning. The punishment approached state-sanctioned murder. The objects of wood and stone themselves were almost living heretics. By having their statuesque feet put to the fire, they were treated with no more and perhaps even less respect than what was due to common criminals. The point was iconoclastic, to demolish the worship of idols. In that context, the effigies were lightning rods that took a hit for the whole Catholic Church.

Yet inadvertently this treatment of the images by the firebug fanatics perpetuated the very assumptions that it sought to end. In the process, it conceded to them the status of living beings: they were old flames in more than one sense. To the executioners, the broiling of the representations was retributive justice. To their impassioned devotees, the mass cremation must have seemed tantamount to martyrdom. Cult statues of the Virgin were hauled in from such sites as Cardigan, Caversham, Coventry, Doncaster, Ipswich, Lynn, Penrhys, Southwark, Willesden, and Worcester. Then this rogues’ gallery was raked over the coals so that Mary could go out in a blaze. To take one out of alphabetical order, a final Madonna hailed from the most hallowed late medieval English shrine of Our Lady, Walsingham in north Norfolk. Along with her sanctuary, she deserves further discussion.

Walsingham, England’s Nazareth

The demolition of the shrine and the dispersal of its contents at Walsingham was a singularly earth-shattering act of ruination. The Holy House and church surrounding it have been reconstructed from their image as transmitted in the wax seals of the medieval abbey. Despite all the care, in the replication the originals have been reduced to the merest façade of what they once were (see Fig. 4.4). Reappearances can be deceiving.

The chapel had an elaborate foundation legend. In the account as recorded much later, a Saxon noblewoman and widow experienced three times in 1061 a vision in which the Virgin first transported her mystically in a true flight of fancy to the Holy House of the Annunciation in Nazareth. Then, the Mother of God bade her to honor the announcement of the Incarnation by erecting in Walsingham an exact replica of the home. It would not be easy for her to determine the building site and achieve the construction. For her pains, the visionary was assured that when built, the shrine would enable all those who sought succor there from Mary to receive it. The prediction came true. Between the mid-twelfth century and 1538, Walsingham became one of the most heavily frequented sanctuaries to the Blessed Virgin in England and even in the Christian world. The connection with the unveiling of the birth of Jesus meant that the Latin prayer known as the Hail Mary was held in special reverence at the chapel and later at the priory on the spot. Among many relics, the holy place was particularly renowned for a phial that allegedly contained milk from the Mother of God.

Fig. 4.4 The remains of Walsingham Priory, Norfolk. Photograph by John Armagh, 2011. Image from Wikimedia Commons, © JohnArmagh (2011), CC BY-SA 3.0, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WalsinghamPriory.jpg

Fig. 4.5 The Walsingham Virgin and Child. Seal (obverse), late twelfth to early thirteenth century. Cambridge, Archives of King’s College. Image courtesy of King’s College, Cambridge.

Most germane to the story of Our Lady’s Tumbler is that the Holy House in Walsingham contained a wooden majesty, with Mary on a throne with the infant Jesus seated on her lap. The effigy may have been a Black Virgin or Black Madonna, so called because of its dark hue, an artistic application to the Mother of God of the “I am black but comely” image of the Bride in the biblical Song of Solomon—the closest that the Middle Ages came to the late twentieth-century trope of “black is beautiful.” In any event, the carving was annihilated close to a half millennium ago. Yet despite its disappearance hundreds of years before now, we can still form a picture of the Walsingham statue thanks to a representation of it on a seal from the late twelfth or early thirteenth century (see Fig. 4.5). Other portrayals are found on the badges of lead or pewter that were retailed as souvenirs to pilgrims. Such tokens could prove that a person had completed a pilgrimage to a given destination. In addition, they could convey the grace of the Virgin to those who encountered them. Other similar keepsakes included pewter flasks. These vessels contained water from the holy wells that were located not far from the shrine. In many regards, these objects functioned as amulets.

The foot traffic of pilgrims to what became the Augustinian priory grew extremely heavy in the late Middle Ages. Walsingham developed into the principal Marian destination in England. The growth in movement gave rise to a rat-a-tat drumbeat of criticism even before the Reformation. In 1356, the Archbishop of Armagh delivered a sermon in which he denounced worship by those who failed to distinguish between a Madonna and the Virgin Mary in heaven herself. By his lights, images of this sort included the representations of Saint Mary at Lincoln, Newarke in Leicester, and Walsingham. Further, he charged the custodians of such holy places with fomenting miracles so as to pad their own coffers. A chronicler described how the Lollard iconomachs slurred the Virgin of Walsingham by calling her in vernacular English “the Witch of Walsingham.” These followers of John Wycliffe protested against the custom of referring to the cult image as “our dear Lady of Walsingham” rather than as “our dear lady of heaven.” Likewise, they condemned it as “vain waste and idle to trot to Walsingham rather than to each other place where an image of Mary is.” To such dissenters, an image is an image is an image: local images and relic cults have no point.

The Renaissance humanist Erasmus gives a detailed picture of Walsingham and his observations when he made a pilgrimage to the site in the summer of 1512, in appreciation of the success that the Church scored against the schismatic King Louis XII of France. The Dutchman’s portrayal of his experience is far from altogether positive. He characterizes the community as depending wholly on revenue from pilgrims. His account of their moneymaking machine is acerbic and sharp-tongued, with flashes of hilarious comedy. His hard-edged description of the shrine gives vent to his distaste for the popular devotion of the late Middle Ages. In his finickiness, he shrank back from the physicality of the practices that the canaille pursued. Thus he conjures up vividly, and mostly not flatteringly, the lighting, smells, and even tactile qualities of the objects and spaces involved in the expression of lay piety. In other words, he executes the mental process of sensory integration, by which he makes meaning from information collected by his senses. This is what common sense is all about. He describes the windowless chamber where the image was domiciled, probably with curtains or a canopy billowing around it. This separate space was the original Holy House, which by Erasmus’s time had been encased in a far larger chapel. In it, the light of shimmery candles reflected from scores of gold and jewel objects, alongside masses of humbler oblations. Erasmus gives us to believe that despite all the blazing tapers, the inner sanctum offered to the spirit more heat than light.

As a pilgrimage site, Walsingham may be usefully compared with Loreto. The Italian town is by many accounts home to the Holy House. This structure purports to be the home in Nazareth in which Mary was born and raised, received the Annunciation, and lived during the childhood and after the ascension of Jesus. The little building has drawn pilgrims since at the latest the fourteenth century. It was transported, so the story goes, from the Virgin’s hometown on the wings of angels to rescue it from infidels. The timing may not be purposeless. The movement began only three years after 1291. That date saw the toppling of Acre, the tail end of the crusader kingdoms in the Holy Land. The retreating campaigners could have transported with them from Nazareth stones from the edifice where the angel Gabriel broke the news to Mary that she would conceive and become the Mother of God. Alternatively, they could have brought back the trauma of having abandoned the house and other important sites to the Muslims. They could have assuaged at least partially the hurt of loss through wish-fulfillment, in the fantasy of the angelic levitation.

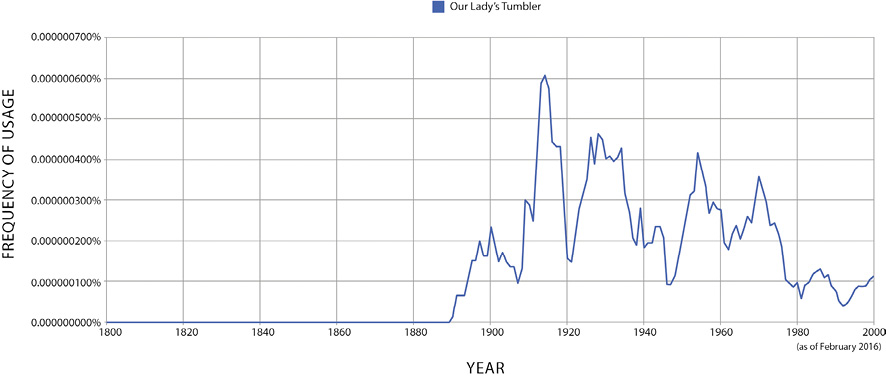

Whatever the historical realities of the building and its move, the Holy House offered within the bounds of the European landmass a destination for Christian pilgrims who could no longer venture safely into the Holy Land after the collapse of the crusader states. It became notable in the late fifteenth century. After the destruction of Walsingham, it had every basis on which to surge in popularity. At first, the Holy House was a simple edifice. The chief adornments were a statue of the Virgin beside an altar and a blue-painted ceiling spangled with golden stars. Eventually, the domicile was enclosed within a larger building, and the image of Mary shifted to a plush, jewel-lined niche. This Madonna is held to have been a Black Virgin. A holy card from 1899 illustrates the scene in tacky pastel colors, with a German legend, “Miraculous Transportation of the Holy House to Loreto” (see Fig. 4.6).

Despite undeniable parallels between Walsingham and Loreto, the two shrines diverged in major ways. For one, the scale of the Holy House of Nazareth in the Italian hilltown differed substantially from the one in England. In contrast, the dimensions of the Santa Casa (to use the Italian name for the stone building in Loreto) corresponded reasonably closely to those of the fourteenth-century Slipper Chapel in Walsingham (see Fig. 4.7). This other church, so called because it marked the point at which pilgrims removed their shoes to trudge in their stocking feet to the Holy House itself, was located about a mile south of Walsingham proper.

Fig. 4.6 Postcard depicting the miraculous transfer of the Holy House of Loreto (Milan, Italy: Tipografia Santa Lega Eucaristica, 1899).

Fig. 4.7 Postcard depicting Slipper Chapel, Walsingham (Norwich, UK: Jarrold & Sons, early twentieth century). © Jarrold & Sons. All rights reserved.

The pilgrims to the settlement in Norfolk included royalty, who made sumptuous gifts for the maintenance of the staff as well as for the adornment of the sanctuary. As elsewhere, candle devotion was central to the cult of the Virgin at Walsingham. By no mere coincidence, the statue of Our Lady there was taken away to be consumed by fire in the aftermath of a royal injunction in 1538, “Forbidding the Placing of Candles before Images and Other Superstitious Practices.” Tapers figured largely in the monarchs’ generosity to the shrine. King Henry III, the first royal to come, paid at least thirteen visits, with the initial one in 1226. In 1240, for the feast of the Virgin’s Conception, he ordered two thousand votives to be burned there and at Bury St. Edmunds. In 1246, he commissioned a golden crown to be placed upon the head of the Madonna at Walsingham. In 1251, he spent the feast of the Annunciation on pilgrimage there, and made the gift of both two silver candlesticks and a valuable chasuble of red samite. King Edward I betook himself to the shrine twice, the second time on Candlemas Day in 1296. The candlelight can be pictured easily that would have coruscated when the feast of this holiday was celebrated. King Henry VII came no fewer than four times. King Henry VIII of England, who was responsible for the demise of the statue and much else in the community, paced barefoot two miles to reach the site in 1511, made lavish donations there, and kindled a candle before the Madonna in March 1538.

The character Avarice in William Langland’s late fourteenth-century personification allegory Piers Plowman takes a pledge that reflects the author’s reprobation of the motivations that propelled pilgrims to make the trek to Walsingham. The mention of a peregrination there had a special cachet. Of course, worshipers also journeyed to other sites relating to the Virgin in England as well as on the continent. For example, rich documentation survives on Marian pilgrimage in late medieval and early modern Germany. Such voyages eventuated in an unalterable syllogism: pilgrimages led to shrines, and such holy places (above all, ones connected with Mary) centered upon images. For the reformers, the counter-syllogism was patent: to end such veneration, desacralize its objectives. The corollary was equally unmissable: to desecrate sanctuaries, destroy Madonnas. In the Reformation, modernizing meant de-Madonna-izing.

Toward the end of 1538, the reformist bishop of Worcester Hugh Latimer (see Fig. 4.8) notoriously decreed that the image of the Virgin in his diocese—and others, including the one at Walsingham—should be charred. Latimer addressed the letter in question to none other than to Thomas Cromwell, chief minister of King Henry VIII. The bishop’s aspiration was soon fulfilled. The incineration of the carvings, and the shutting down of all shrines in England, were concomitants to the suppression and dissolution of the monasteries. Henry VIII ordered these draconian acts in 1536 and 1539, and Cromwell oversaw them as agitator-in-chief. The aftereffects included the abandonment and devastation of many abbeys. The figure of Our Lady of Walsingham was abducted to be put to the torch; the swank sanctuary was first despoiled of its gold and silver ornaments and then dismantled; and the priory and its dependencies were largely razed and abandoned. The sites and image of Our Lady that can be seen today are anything but original. Rather, they have resulted from a Marian revival in Britain that has been supported by the papacy since the late nineteenth century.

Fig. 4.8 Unknown artist, Hugh Latimer, late sixteenth century. Oil on panel, 55.9 × 41.9 cm. London, National Portrait Gallery. Image courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London. All rights reserved.

The Madonnas that have been enumerated were neither the first nor the only ones to suffer the fate of destruction. When the impetus to remake the fabric of the Church was taken very literally, many others were denuded of their garments, irreparably mangled, or even summarily destroyed in expressions of iconoclasm by the riffraff. In England, a hard-edged campaign was waged against what was regarded as Mariolatry, the according to Mary of worship due to God and God alone.

The first bout of statue-tory abuse extended to the removal in 1535 of an Our Lady’s girdle, worn by expectant mothers to help them in their pregnancies and especially in childbirth. Often effigies suffered radical mastectomies in which their breasts were stabbed or hacked off. Their arms were severed and their faces defaced. The representations of the infant Jesus that they held were cut away. In 1581, for instance, the Virgin and Child along with other figures were subjected to what might be called holy (or unholy) vandalism wrought upon the Cheapside Cross in London. In a renovation, the Madonna was replaced by a semi-nude image of the Roman goddess Diana. Later, the Mary was reinstalled but after twelve nights she was de-crowned, beheaded, and shorn of her offspring. Another relatively late manifestation of the iconoclasm came in 1578, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, nearly two decades after she succeeded her Catholic half sister Mary to the throne in 1559. While touring Norfolk near Thetford, the ruler made what was presented as being a chance discovery. In a hay house, she happened upon an image of Our Lady that she considered an idol, and she had it carbonized.

The sixteenth century lacked most of the devices that are for the taking today to record and document such barbarism visually. Yet around 1570, an unknown artist captured a scene of iconoclasm within a picture painted with oil paints. The panel depicts the young King Edward VI receiving the blessing of a bedridden Henry VIII and the Pope, who along with the monks to his right is being crushed by the Bible (see Fig. 4.9). Through a window, reformers are visible outside. The two nearest tug on ropes to tip and overthrow a statue of the Virgin and Child. Not only in England did what could be called Mariaphobia express itself in anti-Marian iconoclasm. In Germany, one excruciating act of such Madonna mayhem put in the crosshairs not a statue but a painting. An artwork of the Virgin and Child by the artist Hans Holbein the Elder suffered destruction in the cathedral in Augsburg in 1537. In some locations, images of Mary became the objects of literal tugs-of-war between opposing factions of Protestant reformers and Roman Catholics.

What have been nicknamed “cults of battered Marys” arose. All over Europe, Protestant hooligans would subject to misuse and mutilation Madonnas that would be rescued and sometimes repaired by Catholic handymen of holiness. Thus, specific representations of Our Lady endured abuse in Paris repeatedly, in Geneva, and in the English College Chapter of Valladolid (see Fig. 4.10). Mistreatment of a similar sort was supposedly meted out to depictions of the Virgin during conflicts between Catholics and Protestants in the nineteenth century in England. By the mid-seventeenth century, a census of images would have found their number and distribution pared back sharply because of iconoclastic reformers.

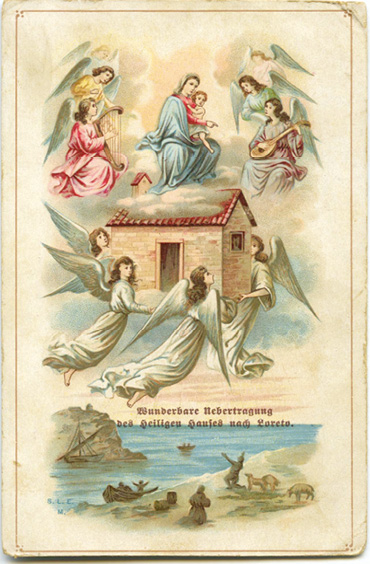

In the 1650s, a Jesuit tallied over one thousand Marian shrines, providing for each a brief history and an engraving of its Madonna (see Figs. 4.11 and 4.12). The four-digit headcount is remarkable. As a sequel, the author drew up a discrete index containing a subsection listing wounded Virgins, as well as taxonomies of weapons wielded against them, portions of the likenesses that suffered thuggery, types of damage, and kinds of action taken by Mary in response to the contusions. A roll call taken in the early nineteenth century in France would have tabulated another sharp drop, since the French Revolution brought about the destruction of the effigies and relics that had outlasted the Reformation. Across the ages, Madonnas that have demonstrated a special capacity to withstand persecution have become the objects of popular devotion, legends, and superstitions. We will see medieval images that demonstrated impressive skills as proto-survivalists, but for the present let us focus on the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Fig. 4.9 Unknown artist, King Edward VI and the Pope, ca. 1575. Oil on panel, 62.2 × 90.8 cm. London, National Portrait Gallery. Image courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London. All rights reserved.

Fig. 4.10 Nuestra Señora de la Vulnerata. Statue, sixteenth century. Valladolid, Real Colegio de San Albano. Photograph by Rubén Ojeda, 2010. Image from Wikimedia Commons, © Rodelar (2010), CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nuestra_Señora_de_la_Vulnerata.jpg

Figs. 4.11 and 4.12 Title page and title illustration of Wilhelm Gumppenberg, Atlas Marianus sive de imaginibus Deiparae per orbem christianum miraculosis, vol. 1 (Ingolstadt, Germany: Haenlin, 1657), with Virgin and Child on the Holy House, and beams showing its westward movements.

Madonnas of the World Wars

A man is ready to leap to his death from a tall building. An Irish policeman barrels up and yells, “Don’t do it! Think of your mother!” The man answers, “My mother’s dead; I am going to do it.” The cop says, “What about your father?” “He left when I was a baby.” The cop goes down the list with no success until finally he shouts, “Don’t jump! Remember the Blessed Virgin!” The would-be suicide asks, “Who is that?” The officer answers, “Jump, Protestant! You’re blocking traffic!”

Mary is an obvious dividing line between Protestants and Catholics. After the Reformation, the disparity between the two branches of Christianity sharpened. Among other changes, different regions became distinguished by the absence or presence of the Virgin on street corners, in statues or paintings. To Protestants, the sight of such images grew to be unfamiliar in every respect, whereas to Catholics in many places, these representations were unexceptional and even humdrum in daily life. In 1859, Henry Adams commented upon the “old road-side saints, crucifixes and Madonnas” that he encountered in the German region of Franconia, which he would never have seen in New England. During World War I, such sculptures and pictures belonged to the religious paraphernalia of Catholicism that took doughboys from the United States and their equivalents from other predominantly Protestant countries by surprise. Those soldiers who had been born and bred Catholic were more accustomed to the trappings of Marianism.

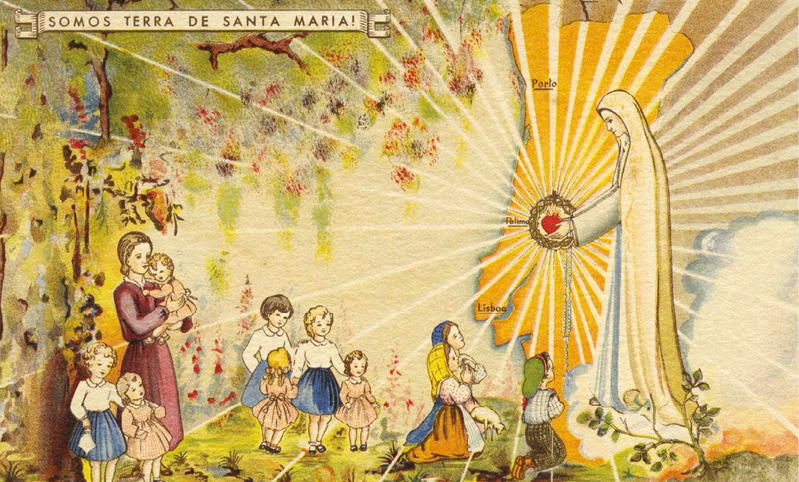

On both the front lines and the home front in France, Catholic Germany, and elsewhere, people were likelier in wartime to turn for comfort to the Mother of God than at any time since the years surrounding the Franco-Prussian war. Military conflict, political tension, and economic desperation have often furnished a powerful recipe for sightings of the Virgin and for miracles associated with her and with her representation in Madonnas. Our Lady of Fátima in Portugal was the foremost case in point. A cult arose there from appearances of Mary to three shepherd children that took place once a month over one half year in 1917. This manifestation of the Virgin was later made the basis for what became effectively a Marian Cold Warrior, since for the first few decades in the second half of the twentieth century the message of Fátima was construed as a denunciation of Communism and the Soviet Union.

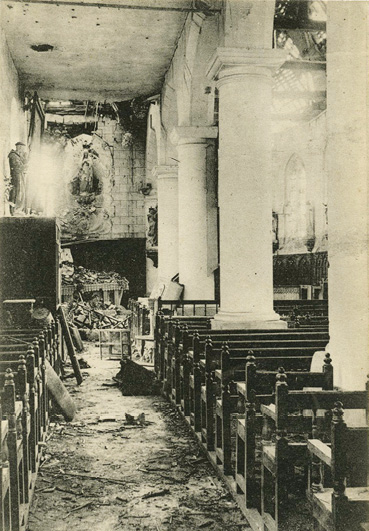

Particularly awesome in the apocalyptic land- and cityscapes of World War I were postbellum representations of images that appeared to have been spared divinely from mangling or burning after bombardment. For instance, a statue miraculously unaffected by the fracas of warfare was the Mary of Igny, a thirteenth-century jewel in the crown, which came through without a scratch despite all the harm inflicted upon Reims cathedral by bombs and fire in September 1914 (see Fig. 4.13). Another such representation was a carving of Notre Dame of Lourdes that stood on the altar of the Holy Virgin in the church of Bouchoir in Picardy, which was shelled in the Battle of the Somme (see Fig. 4.14). On a postcard the caption explains: “The shrapnel exploded in the war and destroyed everything in front of the statue. The Virgin was touched by neither the shrapnel nor the stones that came loose all around her head.”

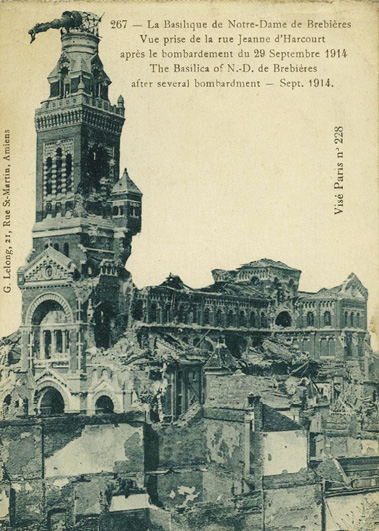

A third survivor was a gilded Madonna, sometimes called the “Divine Shepherdess,” that crowned the basilica of Notre-Dame de Brebières. This sizable house of God was built in the modest town of Albert in Picardy at the end of the nineteenth century to replace the parish church that had grown too cramped to accommodate pilgrims. The worshipers who descended upon the basilica were caught up in the Marian fervor connected with the sites of apparitions of the Mother of God at La Salette and Lourdes. This sanctuary became an objective because it housed the Black Virgin after which it was named. The Madonna in question is so called after the small community of Brebières. The noun, meaning “pastures,” derives from the French brebis, or “sheep.” The onomastic lore is not beside the point. After all, legend held that this representation of Notre Dame was unearthed in a field near the town by a shepherd whose flock kept returning to the same patch of tufts of verdant grass. When the herdsman clawed at the sod with a hoe, the tool banged upon a statue of the Virgin and Child that had been buried there.

Fig. 4.13 Postcard depicting a damaged thirteenth-century statue of the Virgin after the bombardment of Reims (Paris: H. George, 1914).

Fig. 4.14 Postcard depicting a ruined chapel of the church of Bouchoir, with the miraculously unharmed Virgin in the background (ca. 1915).

Fig. 4.15 Postcard depicting the “Golden Virgin of Albert” dangling atop the Basilique de Notre-Dame de Brebières (Amiens, France: G. Lelong, ca. 1914).

Fig. 4.16 Postcard depicting the “suspended Virgin of Albert Cathedral” (London: Pictorial Newspaper Co., ca. 1914).

The sculpture atop the basilica was different and unusual, since it depicted Mary holding the infant Jesus aloft to God. The dome supporting it was struck in howitzer and mortar shelling by German artillery in 1914, during the Battle of the Somme (see Fig. 4.15). Despite being hit, the artwork was not destroyed. Nor did it plummet to the earth, but dropped more than ninety degrees to dangle slightly below parallel to the ground. From its posture it become world-famous as the Leaning or Golden Virgin of Albert (see Fig. 4.16). To many members of the military, the representation was part and parcel of their first exposure to Catholicism, whose beliefs, practices, and expressions seemed exotic and alien. The combatants developed many interpretations of the Madonna’s circumstance. Apparently her stance could mean almost anything, except nothing. To one, she looked to be leaning down to snag the Child, like a fallen infantryman. To others, she was presenting him as a sacrifice or as a peace offering to expedite the close of the war. To saltier wits, the destabilized statue looked like a flunking phallus as it flopped flaccidly at less than half mast. Not accepting that sometimes a statue lolling below the horizontal is just a statue lolling below the horizontal, she was dubbed the “Lady of the Limp.”

Soldiers on both sides subscribed widely to two related conventions, too recent and too male to be termed old wives’ tales. One was that the battle royale would end when the statue finally fell. The other held that the side to bring her down would lose in the conflict. Neither superstition was borne out. What was the upshot, so to speak? To begin with ballistics, the Virgin remained attached to the dome until annihilated by British heavy guns in 1918. The war stretched out for a little while, and the Allies carried the day. In the meantime, the mangled Madonna had not fifteen minutes of fame but four years of it. During that stretch, it became known worldwide through postcards dispatched from the battlefront to the home front. Many belligerents saw the statue in its partly unglued condition and shared the experience with far-off friends and family in their own countries by mailing images. Eventually a replica, no longer drooping, was put back in place when the basilica was reconstructed from 1927 to 1931.

World War I did not mark the end of miraculously preserved Marian images. In World War II, a thirteenth-century wooden Madonna in the nave of the parish church at La Gleize in Belgium was the only item in the war-scarred building to stay unscathed when the town was leveled in 1944 during the bruising Battle of the Bulge (see Fig. 4.17). Nearly seventy years later, in October 2012, Hurricane Sandy struck the spit of land in Queens, New York, known as Breezy Point. Its gusting wind and storm surge left tremendous havoc in their wake. Torrential rains gave way to even worse. The windblown and waterborne disrepair was compounded by the conflagration that burned uncontrolled afterward. One house at the corner of Oceanside Avenue and Gotham Walk was among the more than one hundred homes fried to ashes. Even so, the site became a cause for hope. Amid all the rubbish from the destruction, a statue of the Virgin that had been placed in a niche in the garden was somehow left upright and intact (see Fig. 4.18). Whether by fluke or by miracle, the future will no doubt also have its share of Marys uninjured after catastrophes, and those images too will be made rallying points for survivors.

Fig. 4.17 Statue of the Virgin in the ruins of Le Gleize Church, Belgium, after the Battle of the Bulge. Photograph, 1945. Washington, D.C., Archives of American Art, Thomas Carr Howe papers, 1932–1984. Image courtesy of the Archives of American Art, Washington, D.C. All rights reserved.

Fig. 4.18 A Madonna statue among the wreckage of Hurricane Sandy in Breezy Point, New York. Photograph by Mark Lennihan, 2012. Image courtesy of the Associated Press. All rights reserved.

Literary Iconoclasm

To return to the Reformation: in those regions where effigies of the Virgin were destroyed, a commensurate effacement of stories about her would have taken place. Sometimes the clampdown probably took place through the handling or mishandling of manuscripts by the reformers. A 1535 letter to Thomas Cromwell from a royal commissioner lists among items seized from a monastic library during a visitation “a book of Our Lady’s miracles, well able to match the Canterbury Tales; such a book of dreams as you never saw, which I found in the library.” The only record of a Marian miracle text to be so confiscated, this missive to the Vicar General—despite its reference to Chaucer—leaves unclarified whether the volume is long or short, Latin or vernacular, prose or verse; nor do we come to know what fate it endured. The invocation of the Canterbury Tales, along with the categorization of the miracles as a dreambook, signal the letter writer’s belief that legends of Mary are nothing more than vaporous fiction.

The disappearance of the tales may not be described as bonfires of virginities or even just of images. Unwritten or seldom written narratives are erased not by torches or sledgehammers, but through suppression and silence. All the same, tales that center on devotion to images will fare poorly in times of image-breaking. Theologians may draw fine distinctions between veneration rendered to images, known technically as iconodulia, and outright worship of images, or iconolatry, but others would not necessarily find much relevance in such casuistry. To them, the two practices look very similar, if not even synonymous. Furthermore, the goal of iconoclasm was not merely to rid churches of physical representations, but to rewire the devotional system within which they functioned. Nor did the assault on iconodulia and iconolatry stop there. The likenesses might be turned to cold cinders and smoldering embers; the liturgies associated with them might be discarded and outlawed—for all that, it took much longer and more sustained efforts to sear recollection and to scour mental images of them from minds.

An Elizabethan ballad concluded with two lugubrious stanzas of valediction to the Walsingham Madonna. The lines decried the satanic sin that moved in to occupy the spiritual space vacated by the destruction of the image. Still greater impact came from a ballad that recorded the story of the disappearance. The song places special emphasis on miracles of healing and revivification that the carving enabled. One of Cromwell’s agents, Sir Roger Townsend, wrote to him about a woman whose chattiness about the sculpture brought unpleasant consequences down on her. She gossiped about what he regarded as a “false tale of a miracle done by the Image after it had been carried away.” For this jabbering, she received the penalty of being placed in the stocks and then drawn around the marketplace in a cart with a paper hat on her head to identify her as a “reporter of false tales.” Even so, the Lord Protector’s henchman remained of two minds. Had he extirpated the memory of the Walsingham Madonna or not? “I cannot help but perceive that the aforesaid image is not yet out of some of their heads.” One of the crania at issue belonged to another local lady who also was convinced, even after the statue had been taken down and transported to London, that it had wrought a miracle. Like the above-mentioned teller of falsities, this poor Mariophile got more than a mere rap on the knuckles: she was put in the pillory on market day at Walsingham and then carted around to be pelted with snowballs.

Language was affected as well by the ruthless about-face. Obviously, the learned language of Latin would have been laundered of many features associated with the Catholic Church, but the vernacular did not escape untouched either. Any major alteration of a society requires modifications of speech and writing, both high and low. Reformers wished to scotch the invocation of saints, including the Mother of God, so as to train the sights of the faithful upon God and Christ. The commoners of the late Middle Ages prayed most often to the Virgin. To exemplify how improper and unbecoming such invocations could be, Erasmus derided the prayers of a mercenary who had impudently called upon Mary, “Blessed Virgin, give me rich spoils.” In fact, the Dutch scholar went so far as to quote putative direct appeals from the Mother of God herself in a letter against the shameless and unprincipled entreaties lodged with her. Folks who invoked Mary aloud in prayer were reproved, and subtle changes were wrought in the psalter to constrict the powers ascribed to the Virgin. The eradication of saints from language would find its most telling confirmation in an exception to the rule. According to a widely accepted etymology, the slang expletive bloody is a minced oath that originated in the phrase “by Our Lady.” From the measureless sea of saints’ invocations, only this one dysphemism survived. It remained in existence only because its very meaning and provenance became unrecognizable, its vestiges of religiosity trumped by its coincidental blot of vulgarism.

On a narrative level, a similar bowdlerization may have played out in some stories by replacing Mary and other saints either with nothing at all or with figures sanitized to be presentable within a Protestant context. Mainly what happened was the expunction that results from censorship, both self-imposed and otherwise. The sorts of narratives that would once have commanded respect and awe came to be derided. The atmosphere would have brought Marian miracle tales at full tilt to oblivion. For example, the Protestant bishop John Bale heaps mockery upon a vision that was reputedly experienced in 1470 by the Dominican theologian Alanus de Rupe. Female virgin saints are often supposed to undergo mystical marriages, in which Christ appears to them and places a ring upon their fingers as a sign that he is taking them as mystical brides. That is all very well, but in this case Blessed Alanus claimed in writing to have received a house call from the Virgin, who placed a ring on his finger, encircled his neck with a necklace braided of her hair, and presented him with a rosary (see Fig. 4.19). Bale’s restatement of the events puts a different, salacious, even tawdry spin on the symbiosis between the Roman Catholic theologian and a touchy-feely Mary. In the English churchman’s interpretation of Alanus’s account of the episode, the Mother of God came to the friar’s cell and made her gifts to him so that they might plight their troth. Then the proceedings take a decidedly deviant turn. Alanus first fondles his visitor’s breasts, then engages in sexualized breast-feeding, and finally progresses to actual coitus, all somehow without de-virginating the Virgin.

Fig. 4.19 Guido Reni, Madonna col Bambino in gloria e i santi Petronio, Francesco, Ignazio, Francesco Saverio, Procolo e Floriano, 1631–1632. Oil on silk, 390 × 220 cm. Bologna, Pinacoteca nazionale di Bologna. Image from Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Guido_Reni_057.jpg

In Protestant theology, saints, among whom Mary was foremost, lost their stature as mediators between God and people. Since Christ alone fulfilled that function, the Mother of God was decentered as the object of special devotion. In the Middle Ages, the Virgin stood supreme as mediator above all others. By the thirteenth century, her ascendancy made her almost a fourth person of the Trinity. For centuries afterward, she retained this lofty status, to the abiding scandal of non-Catholics. Even in the mid-nineteenth century, a Protestant magazine in England reported on an Irish immigrant who allegedly considered Mary to be a member of the Trinity.

This same elevated status was reflected in the reverence the Mother of God received throughout the later Middle Ages in her images, Madonnas. Protestant reformers condemned the cult of the Blessed Virgin as a form of respect gone too far—as adoration that verged on adulation and idolatry. In Catholic theology, the Ecumenical Council of Trent, which extended from 1545 to 1563, brought reform. Most relevantly, it reaffirmed the importance of the veneration of saints, particularly the cult of Mary. At the same time, the Council laid great emphasis on the legitimate use of images, including those of the Virgin. It emphasized that honor shown to the representations is referred to the prototypes represented by them. The faithful do not worship, petition, or trust the Madonna itself, but rather the Mother of God represented by it. Even in northern Europe Mary was never altogether ousted among Catholics as happened to a great degree in Protestantism. Yet despite the Trentine reform, she was nonetheless sometimes shunted aside in favor of a Christocentric viewpoint.

Some jongleurs would have suffered the same diminishment, if not demise, as befell the Virgin, Madonnas, and texts about her. The reason is not far to see. The performers would have been linked with the pilgrims and preachers who teamed up to spread her cult. In effect, the entertainers belonged to the whole, vast pilgrimage industry that reformers were keen to exterminate. This is why around 1546, the English clerk William Thomas fawns upon King Henry VIII for having investigated the many malfeasances of the friars, whom Thomas calls jugglers. The tumbler and his like had been popular at certain times because the Virgin and he had been believed in tandem. Now the equal and opposite came true. He became unpopular as Marian miracles fell into disbelief and as Mary herself faded from the ubiquity she had achieved between the twelfth century and the late Middle Ages.

Among Protestants, Mary held an ambiguous position. Her cult was roundly castigated. As an object of study and devotion, English writers strikingly avoided her for hundreds of years after the Reformation. The publication in 1827 of John Keble’s Christian Year marks the commencement of the Marian revival in nineteenth-century England. To look at the situation somewhat differently, in many places the Virgin was largely excluded from the transition that led from manuscript to print culture. Miracle tales dropped out of vogue just as the presses began to bring forth torrents of books. Yet even within Protestantism, the Mother of God was not universally thrust aside as almost all other saints were cast away. A cleavage is perceptible between Lutheranism, in its defense of Mary, and Calvinism, in its assaults on her. Martin Luther, who himself owned an image of the Virgin and Child, argued that iconoclasts should spare Madonnas, since they could serve as devotional aids. At the same time, the German reformer commented with disapproval on images that depicted the lactation of Bernard of Clairvaux, in which the so-called Marian Doctor is represented receiving a spurt of milk from the Virgin’s breast. Thanks to Luther’s generally supportive outlook, Marian images continued to be fabricated and displayed in some places. Even so, they came with the caveat, explicit in inscriptions or implicit in doctrine, that the Mother of God was to be honored but not worshiped. The emphasis on reverencing her was codified in Luther’s writing. In a commentary he opined at length about the type of veneration and lauds to be given to the Virgin. She is cherished most truly by honoring the Almighty. If esteem and praise are accorded to her, the objective is to attain God through it.

For all the support that the reformer offered, Lutherans have retained their discomfort with freestanding statues of Mary as potentially idolatrous. The lingering worry about the verisimilitude of this three-dimensional form of Madonna may help to explain why in the one recent retelling of our tumbler’s story for children by a Swedish artist and author, the carving is replaced by a painting. For that matter, in its title the book makes no mention of the Mother of God, the Virgin, or a Madonna, and the illustrations on its dust jacket avoid representing any of them as well. These omissions need not be driven explicitly by religion, but by general cultural context. Sweden has been predominantly Lutheran since the sixteenth century. Outside a denominational context, the self-serving inconsistency of Christian views on idolatry has long attracted remark within the framework of world religions: “We sneer when we read of some Indian spinning tops before his child god Krishna, but we weep over the story of the jongleur de Notre Dame and await with sympathy the Madonna’s approval of his pathetic juggling.”

Marian Apparitions

The tale of Our Lady’s Tumbler belongs to a vast complex of medieval narratives and images connected with the intervention of heaven upon earth through appearances of Mary. In fact, it falls within the far larger category of Marian apparitions. At the latest tally, counted down to the present day, more than 2,500 have been reported. Visions, shrines, relics, and images of the Virgin interact with each other in constantly varying but often intersecting ways. If Mary and Madonnas have been shrouded in clouds of misgivings within a large part of Christianity since the Reformation, so too have been attitudes toward phantasms of the Virgin. Direct physical experiences of her, such as seeing her, hearing her, and being touched by her, were everywhere in the medieval period, as for example at Loreto and Walsingham, but they have been primarily a Catholic phenomenon since then. The basics of an official policy emerged only long after the Middle Ages in the writings of the future Pope Benedict XIV (see Fig. 4.20).

Fig. 4.20 Pierre Subleyras, Benedictus XIV, eighteenth century. Oil on canvas. Palace of Versailles. Image from Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Benoit_XIV.jpg

Marian apparitions remain objects of fascination and perplexity, as much within the Catholic Church as without. What passes muster as an apparition? A definition, probably unhelpfully short, would be that it is a private revelation. A longer version would hold it to be a type of vision in which someone claims to see a person, being, or object that would not normally be apprehensible to the visionary. The degree to which such sightings are corporeal or incorporeal can be hard to gauge. When manifestations of this kind are not documentably physical and leave no material traces, they may be differentiated from statues that move or crybaby paintings that shed a monsoon of tears or blood.

Many iterations of the story of the jongleur are unusually elliptical about the relationship between the Madonna, which is an image, and the Virgin herself. The ambiguity only increases because we are left in limbo as to whether the performer himself or just the onlooking monks witnesses the apparition, whether either the animation of the image or the appearance of Mary has happened before, or whether the miracle (or is it two?) has been performed to teach a lesson to the monk-voyeurs.

The overwhelming majority of Marian apparitions have become unwanted stepchildren of the Church. Even so, the most successful ones resulted in the foundation of sanctuaries that are magnets for pilgrimage. An early instance would be the showing of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico (see Figs. 4.21 and 4.22). (The location in the New World has significance, since it places the miracles far from the friction between Catholics and Protestants in Europe. The natives who were converted because of it knew nothing of iconoclasm within Christianity, only of Christian militancy against the idols of pre-Christian religions—heathenism.) According to official accounts, a maiden appeared on the morning of December 9, 1531 to Juan Diego. The Virgin directed this native American convert to Christianity to collect blossoms from the top of the nearby eminence. Despite the wintry season, he found Castilian roses flowering there. At least since the Middle Ages these beauties have been associated with Mary, as have lilies. Both blooms have insinuated themselves, sometimes with sub rosa stealth, into many versions of the narrative about the juggler of Our Lady.

Fig. 4.21 Juan Diego’s image of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, 1531. Mexico City, Nueva Basílica de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe. Image from Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Virgen_de_guadalupe1.jpg

Fig. 4.22 Postcard depicting Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (Zurich: Kunzli Hermanos y Cias, early twentieth century).

The Mother of God arranged the colorful harvest in Juan Diego’s tilma, or “cloak.” When he opened the mantle before the archbishop, the petals fell out. What is more, the fabric of the garment was discovered to bear the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe. The miraculous pictorial representation on the cloth has been revered ever since in the Chapel of the Virgin Mary in Tepeyac, which was constructed for mounting and displaying it. The depiction relates intriguingly to the so-called Black Virgins of earlier centuries, since the complexion of this Madonna is dark, often brought home in mass-produced images through the addition of black eyelashes. The Virgin of Guadalupe is sometimes designated affectionately among Spanish speakers as La Morenita, literally “the Little Moor,” to suggest by extension “the Little Dark One.”

After the Virgin of Guadalupe, a gap of a few centuries ensues in high-profile Marian apparitions. A later example is Our Lady of Lourdes in France, connected especially with the showing of Mary on February 11, 1858 to Bernadette Soubirous. A third case is that of Our Lady of Fátima in Portugal, as noted above, based on appearances of the Mother of God to three shepherd children, with the central visionary being a ten-year-old shepherdess. Their sightings took place on the thirteenth day of six sequential months, beginning on May 13 and ending on October 13, 1917 (see Figs. 4.23, 4.24 and 4.25). This vision exhorted the young ones who saw her to be conscientious in reciting their rosaries, and even called herself Our Lady of the Rosary. Each of these pilgrimage sites attracts millions of visitors per annum. A tale containing the germ of this pattern, with a Madonna and an apparition, as does Our Lady’s Tumbler, would have been by its very nature out of bounds within Evangelical denominations.

Fig. 4.23 Postcard depicting Our Lady of Fátima appearing before shepherd children (Porto, Portugal: V. Matos Trigo, 1960s).

Fig. 4.24 Postcard depicting Our Lady of Fátima (Porto, Portugal, 1967).

Fig. 4.25 Postcard depicting Our Lady of Fátima (Zurich: Hermanos S. A., early twentieth century).

If it is painless to see why Our Lady’s Tumbler could not survive in Protestant regions, the explanation for why the story dropped out of vogue in Catholic regions may seem harder to fathom. Then again, consider a paradox that makes the tale profoundly unsettling. Our Lady’s Tumbler could not be more deeply imbued with organized religion. After all, the events take place within a monastery and all its chief characters save one are monks. At the same time, that one exceptional individual, not just a mere layman but even the humblest sort of one, attains direct contact with the sacred. Furthermore, his interaction is unmediated by a priest or any other representative of the Church—apart, of course, from the mediation of the mediator par excellence, the Virgin Mary herself. If we make the improbable leap of drawing an analogy based on present-day corporations, we could put the dilemma into the tracery of an organizational chart. By the vow of obedience, a monk, even a lay brother, in a matrix structure would report formally to the abbot as manager, but also to God and through God to others such as Mary. The tumbler’s relationship with Mary would be a solid line, that with the man who heads his abbey dotted. The ecclesiastical hierarchy stipulated the reverse.

Our Lady’s Tumbler is about prayer, devotion, and worship. Simultaneously, it illustrates how those acts do not require learning, Latin, or priests. In contradistinction, it implies that praying has the objective of transcending mere linguistic signification and verbal pronouncement so as to achieve silent communion. In rallying words to conjure up the movements of an acrobatic dancer, the poem has enormous graphic power. Yet in its content and outcome, it subverts its own potential as a text by flatly denying or at least depreciating the very importance of writing and even language more broadly. Ultimately, the narrative’s message is that to be saved, the only necessity is to curry favor with the Mother of God, whose intercession can accomplish anything. As a rule, the Virgin never forsakes a votary. Obeisance done to her is done at the same time to the Child, through whom grace and salvation come, since Mary’s prayers to her son carry a special weight. The infant Jesus is not mentioned in the medieval French poem, nor even Mary’s status as mother. All the same, they are both singularly important. They are left unsaid only because they are givens.

The tumbler does not know his catechism, or at least not his monastery’s Latin one. What is more, he has the insouciance to reach out directly in worship to the Virgin, by performing a trifling act, the only form of devotion feasible for him. Yet his personalized trivial pursuit turns out to succeed far better than all the elaborate liturgy of his fellow monks. He undergoes a deeply personal conversion, and he expresses his reverence through a faith based on experience. His sincerity is deemed meet and proper by Mary, who bestows her renowned clemency on him. The lesson is a typically Protestant one: when everything is taken into account, what matters is inner spirit rather than outer formalism. In the words of an American historian who studied life in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, “the story implies that the interior spiritual disposition of the believer, more even than his external behavior, defined the character of true holiness.” Thus, Our Lady’s Tumbler anticipates later pietist movements within Christianity that focus on the efforts of lay people to achieve individual sanctity by leading a consistent Christian life. So far, so good, except for two provisos. The first is that we are accorded almost no insight into the tumbler’s innermost thoughts and feelings; the second is that the validation of this ground rule comes after a supremely un-Protestant miracle involving an image. For these reasons and others, the story may have been superficially too Catholic for a Reformation era but too latently Protestant, or at a minimum too popular in its underlying religious presuppositions, for a Counter-Reformation. It ran the risk of serving neither the reformers nor the counter-reformers. To round off the problems that the narrative posed, both groups would have clucked their tongues over the salience within it of such a questionable activity as dance.

Such inferences would clarify not only why this of all tales wilted away but also why, in general, apparitions of the Virgin would have failed to win backing from the Church in the centuries immediately following the Reformation. The showings that have become entrenched in Catholicism came much later, such as those at Lourdes in 1858, Fátima in 1917. By the same token, sites that had been suppressed were revived during the same period: Walsingham has been rebuilt only since the Catholic revival of the nineteenth century. To remain in Britain, it has been observed that in the nineteenth century, just a few Catholic churches there possessed a Madonna before Victoria became queen. Representations of Mary returned only under the influence of the Gothic revival, spearheaded by the English architect and tastemaker Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (often confused or conflated with his similarly named pro-Pugin-ators).

One other point merits mention. Our Lady’s Tumbler is deeply preoccupied with the nature of offering. In other words, the tale is concerned with the type of gift that can win acceptance. It transmits at least two messages about giving. First, an offer is a private matter between individual Christians and their God. Second, it has nothing to do with physical property or financial instruments. The story makes sense for use by churchmen to incentivize prayer, to encourage conversion to lay monasticism, and to achieve various other ends. If, on the other hand, eliciting donations is a priority, this exemplum is not necessarily the logical first choice.

In the short run (although we are discussing a centuries-long stretch) Mary, Madonnas, and exempla about apparitions of her were displaced or suppressed. No facile invocation of the aphorism “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence” can explain away the few hundred years that present neither a text nor even a citation, reference, or allusion to fan hope that Our Lady’s Tumbler was known to anyone at all. In literature, unpopularity in its most hard-baked form can lead to ostracism so complete that the exclusion is tantamount to extinction. But a door remained open at least a crack for the prospective later return of Mary, Marian images, and masterpieces about her apparitions and miracles. Gothic as an architectural style and tales from the original Gothic era (not that they were yet “Gothic tales”) did not die out altogether in the early sixteenth century. Rather, they hid in open view, awaiting archaeological rediscovery and excavation. The story may have all but died. Then again, no text preserved in manuscripts ever is eliminated entirely. Works of literature seldom vanish into thin air.

In 1873, the tumbler was discovered in the cryogenic vat of a manuscript, a one-man iceblock but still capable of being brought back to life. Since that time the big names on the medical team that took charge of his case have been, with surprising frequency, unbelievers, Catholics lapsed into libertinism, Protestants without a solid background in Marianism, and even Jews. Yet at the same time, many others who helped to keep the tumbler in good trim and the juggler on his way were practicing adherents of Roman Catholicism, who sometimes had the special zeal that comes from recent conversion. Thus, the tumbler was revitalized in the late nineteenth century and later benefited in equal measure from the faithful and the faithless. To understand, we will need to observe microscopically those who raised him from the dead (or unliving, to be more precise) and how they accomplished it.