5. A Troupe of Sources and Analogues

© 2018 Jan M. Ziolkowski, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0132.05

It would be interesting, from the point of view of the folklorist, to try to find parallels to the chief motif on which this legend is founded—namely, the notion that Heaven regards with favour the most trivial and lowly offerings, nay, even such as may appear abject and sinful to men on earth.

The poet of the original Our Lady’s Tumbler may have encountered the quiddity of the tale and recycled it from stories in oral circulation, including exempla. We will never pin down to everyone’s liking even roughly how many such narratives he had heard or read. Yet we would be guilty of a serious infelicity if we refrained from speculating about what the author may have owed to literary traditions behind and around him. We would do well to consider Christian and especially Cistercian accounts that could have inspired him. At the same time, it would be idiocy to undervalue the possible contribution of the writer’s own imagination. After all, he drew on not only oral and written literature, but also on life experiences and informed perspectives that he had gained in the school of hard knocks. Thus, we have a dilemma in evaluating the degree of originality in the anonymous poet. The human capacity to imagine is boundless. Nonetheless, many themes that at first appear unique to a specific individual or culture turn out upon close examination to have occurred independently to others.

For a periscope that grants views into what the poet could have felt or seen, we could do far worse than to look at other reports, both fictitious and not, of comparable behavior from other cultures. We would serve our interests well by seeking out accounts of episodes in which individuals act in ways that cry out to be compared with the tumbler. Such records can help us with the challenge of such questions as: Did a tumbler ever actually exist who performed before a Madonna? Did the poet hear a story of a real man like the acrobat? Did he invent him? Or did he tap into a true-seeming fiction created by an earlier author about a performer like the gymnast?

The scrapbook of possible sources and analogues to follow makes no claim to be encyclopedic. The clippings in it, gathered in from the Hebrew scripture, New Testament, and medieval legends and miracles, constitute only part of the panorama. They supplement the real-life histories that have already been provided of actual individuals, from antiquity to the present day, who have elected to express through their performance arts their devotion to God. They anticipate tales to come that are tied to Christmas in Christian tradition as well as to the high holy days in Jewish tradition. Indubitably, the basis of comparison could be multiplied by thorough trolling for oral and written literature from other parts of the world, such as South and East Asia. Whatever the omissions, the comparative scaffolding established here represents at least a start.

King David’s Dancing

She liked the story of David, who danced before the Lord, and uncovered himself exultingly. Why should he uncover himself to Michal, a common woman? He uncovered himself to the Lord.

David, of slingshot fame, was second king over Israel and Judah, thanks in part to his having proved his mettle in hand-to-hand combat and his moral fiber in other capacities. He was also a poet, singer, and musician of the first order (see Fig. 5.1). Almost half of the Psalms in the Bible have been transmitted with an ascription to him. His attainments as a performer were familiar in the Middle Ages and were associated with the figure of the jongleur. At the same time, he was recognized also as a dancer. The medieval tumbler’s gymnastics before the image of the Virgin show parallels to the prancing of King David in his linens before the ark of the covenant in Holy Writ. Features of the single extant miniature that accompanies the text of Our Lady’s Tumbler in one manuscript have helped to bring home the resemblances: in both cases, men in possibly inappropriate clothing behave before altars in surprising ways, not fully accepted by close members of their communities. Both the posture and dress or undress of the gymnast in the illustration call to mind David.

The ark was a chest that contained the two stone tablets inscribed with the Ten Commandments. It had been taken from a battlefield by the Philistines, and its return to Jerusalem delighted David. In the vignette before the ark, three verses pertain suggestively to the story of the tumbler, and bottle the kinetic energy of the king’s performance. They bring home his near-nakedness as well as his athleticism and sheer joy in whirling. The context makes crystal clear that although he is among others, his ecstatic dance is solo. The passage also records how David’s wife, Michal, turns up her nose at his exhibition. She is the female onlooker. When she scolds him for his dancing, the king replies: “I will both play and make myself meaner than I have done, and I will be little in my own eyes, and with the handmaids of whom thou speakest, I shall appear more glorious.” In punishment for her chiding about his sacred dance, she is rendered sterile.

All the physical features in David’s dance were sometimes conjured up in medieval visual images of the scene, particularly in manuscript art. In one representation from the first half of the twelfth century, the sovereign is presented arched backward in a circle. This stance is designated technically as a bridge, and jongleurs were commonly depicted in such a pose. A moralized Bible emphasizes the contrast between the prophet, whose kingliness is signified by his crown, and his spouse, who averts her gaze and makes a sweepingly dismissive gesture with her left arm (see Fig. 5.2).

Fig. 5.1 King David the harpist. Miniature, fourteenth century. Dublin, Trinity College, MS 53, fol. 151r. Image courtesy of Trinity College, Dublin. All rights reserved.

Fig. 5.2 King David dancing. Miniature. Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. Vindobonensis 2554, fol. 44r.

The whole episode of David’s dancing is too thorny to be reduced to a dichotomy between a regal king (and what else could one be?) and his derisive consort. On the contrary, it acquired various kinds of charge. In the first half of the eleventh century, one monk overlaid the actual performances of real-life entertainers in his day upon the biblical ruler. He describes how the seer “sounds the lyre before the ark of the Lord, dances naked, plays, and walks about upside-down.” A century later, the Cistercian preacher Bernard of Clairvaux calls upon the auditors of a sermon to heed the spirit of joy and wisdom in which the monarch performs his two actions of dancing and rebuking. In one tercet in the Divine Comedy, Dante singles out David’s humility for emphasis. The leader’s humbling of himself would have seemed all the more extraordinary to medieval readers or viewers, since by frisking around in scanty clothing he put himself on a level with jongleurs and other socially marginal performers.

Politically, the transportation of the ark to Jerusalem signaled the union of the northern and southern tribes under the single kingship or monarchy of David. This circumstance explains why the potentate is customarily represented wearing his crown prominently, no matter how hyperkinetic he is depicted as being. On the Christological plane, the regal status was particularly relevant to medieval Christians. Allegorically, the taking of the ark can be likened to the capture of Jesus by the Jews. Most frequently, the special chest was aligned with the Virgin. Its triumphal entry into David’s earthly city came to be regarded as prefiguring Mary’s entrance into the heavenly Jerusalem or as foretelling the advent of Christ into the earthly one before the Passion. A retelling of The Juggler of Our Lady on a little more than a single page in a heavily illustrated and highly religious weekly for Catholic children from 1949 follows loosely the story as it was spun in an early twentieth-century opera. It describes the jongleur as being primarily a fiddle player (see Fig. 5.3) but as dancing in the crucial scene, “like David before the ark of the covenant—do we not so call the Virgin Mary?”

Fig. 5.3 “Le jongleur de Notre Dame.” Printed in Le Croisé: Organe belge de la croisade eucharistique 23.5 (October 1949): 76.

In the Middle Ages the episode of David’s dancing was assimilated fast and furious to the motif of the jongleur of God. In a Spanish text written or at least overseen by King Sancho IV the Brave of Castile, who ruled from 1284 to 1295, an exemplum draws on the Bible to recount how the prophet bounded around the ark like an entertainer, with a cithara in hand. When his wife inveighs against him for comporting himself in this manner before his servants, he responds that he feels no stigma. As a jongleur of God, he depreciates himself in the presence of his creator. A metrical paraphrase of Psalm 44, known after the first word in the Latin as Eructavit, exists in medieval French. This poem presents the biblical ruler not merely as a jongleur but even as a wise one. When we consider attitudes in the Middle Ages, attaching that epithet to such a professional almost risked being an oxymoron.

Translating Greek that means more precisely “he uncovers himself like one of the naked dance performers,” the Latin of the Vulgate for the final phrase of 2 Kings (2 Samuel) 20 could be translated into English as “one of the buffoons” or even “one of the jongleurs.” Was David then taken to be a prototype of Saint Francis as a jongleur of God? Later expositors had to decide whether by virtue of being Davidic the dancing constituted legitimate spiritual jubilation, or whether it deviated wildly and distracted from genuine godliness. Religious dance is so widespread as to seem almost universal, and yet dancing, especially within or in proximity to churches, has often been demeaned within Christianity as being inherently immodest, overly sexual, and unsuited to worship.

In the very beginning of the twentieth century, Maurice Léna, who devised the libretto for Massenet’s opera Le jongleur de Notre Dame, drew an immediate connection between the biblical prophet David and the medieval jongleur Jean. When the entertainer dances, the Prior quotes from scripture the verse “Unto his vomit, the dog has turned again.” We have transitioned from eructation to emesis. In other words, he accuses the erstwhile performer of backsliding to his old ways—a gag reflex, in multiple senses. The other monks rant at the newcomer’s impiety and sacrilege for dancing, and call out for him to be anathematized, expelled, or executed. Only Brother Boniface, the bon-vivant chef at the monastery who befriends and protects Jean, leaps to the defense of his fellow lay brother. The potbellied cook, salt of the earth as befits his profession, does so in part by invoking none other than King David.

More than a half century later, and probably independently of Massenet, Duke Ellington revealed similar intuitions in the program note for the Concert of Sacred Music. This was the first of three full-evening jazz suites that he composed for a big band, complemented by a full choir, vocal soloists, and dancers. His cogitation in this First Sacred Concert pertains directly to his own creativity and devotion. As nearly the last of its parts, it contains a piece for full band, choir, and solo tap dancer entitled “David Danced before the Lord with All His Might.” In his comments, the jazz musician connected first the juggler of our story with the biblical prophet, and then the act of juggling with drumming, instrumentalism, dancing, and other nonverbal expressions of a person’s temperament during worship. The performance of this song featured dancing by a tap master, visible in the film. The distinctive rat-a-tat of tap dance, like a solo of scat singing performed by feet shod with metal-plated soles, is plainly audible in the sound track. The Third Sacred Concert contains the track “Every Man Prays in His Own Language.” Ellington once expanded upon these words by adding, “and there is no language that God does not understand.” Close associates of the composer have reported that he was inspired by the Juggler of Notre Dame in both the overall series of sacred concerts and in this particular piece.

The dance of King David before the ark may underlie a motif concerning the girlhood of Mary in the late fourth-century Protevangelium of James. This “first Gospel,” to break down the first word of the title into its two Greek elements, is an extraordinarily influential apocryphon. Among other things, the Protogospel helps considerably to flesh out the extremely sparse treatment of the Mother of God in the New Testament. In turn, the text was expanded in later accretions to these books of the Christian Bible. Its most notable successor would be the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, probably datable to the first quarter of the seventh century. This Latin paraphrase tells of the Virgin’s parents, birth, and life. Such accounts developed to plug many gaps in the canonical Bible and thus to satisfy the otherwise unfulfilled curiosity of believers. The Protevangelium is devoted in the main to Mary’s biography, including her infancy, and family relations before the Nativity. The apocryphal account is ascribed to a certain James, who was probably meant to be Jesus’s half-brother, the son of his father Joseph by a former marriage. Despite this ascription, the composition probably took shape—or at least began to do so—in the second half of the second century. The earliest manuscript is of the early fourth century, but it was not rediscovered and made accessible in the West until long afterward.

The seventh chapter of Pseudo-Matthew describes how at the age of three Mary was taken by her parents Joachim and Anna to be presented in the temple in Jerusalem. By devoting her to God, her father and mother rendered thanks for the blessing of parenthood. Upon being placed on the third step of the altar, the little girl felt impelled by the same sort of sacred ecstasy or holy high spirits that had overcome David before the ark. Like a sacralized Shirley Temple, she performed a little shimmy. Then (the jig was up) she scampered up the rest of the fifteen steps on her own without any unusual behavior. The future Mother of God remained as a temple virgin until she was twelve. Both the dance on the staircase and the service in the sanctuary corroborate the inference that she descended directly from the lineage of David. Whereas Michal greeted David’s prancing with derision, all those present to witness Mary’s fancy footwork take delight and show wonder in it. Although a relatively low-stakes element in the story, the little dance would have been mentioned occasionally when commemorating the Presentation of the Virgin in the temple. But evidence that the girl’s jaunty hopping had any broad impact is elusive. The scene was represented seldom in art, if at all. Among the few images that depict the Mother of God’s ascent of the steps, only a fresco in the Duomo at Prato may make even a faint gesture at alluding to the episode—and not even by showing her dancing but by showing her at the point in the ascent where she could have stopped to do so (see Fig. 5.4). In this composition, her back foot is about to leave the third step as she races up the stairway toward the priest.

Fig. 5.4 Paolo Uccello, Presentazione di Maria al Tempio, ca. 1435. Fresco. Prato, Duomo di Prato. Image from Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Paolo_uccello,_presentazione_di_maria_al_tempio.jpg

The situational parallels between King David’s nimble-footed exultation before the ark and the agile performance of the humble tumbler before the statue of the Virgin have struck various readers independently over the centuries. Despite any similarities, Our Lady’s Tumbler is by no stretch of the imagination merely a calque upon one scene in the Bible. Even the specific moment when the tumbler enacts his routine is not necessarily modeled upon the prophet’s wild prancing. Rather, it has about it an archetypal quality that ties it to stories from cultures elsewhere in the world and time. In fact, the stark chasm in social stature between a lofty biblical king and a lowly medieval performer argues against a cozy association between them.

The Widow’s Mites

Underlying all these stories, a common spirit affirms that God will receive with appreciation even the humblest gift from the humblest person. The only codicil is that the pittance be proffered with sincerity. The distillate of this idea can be found in the New Testament account of the widow’s mites. Jesus witnesses the incident when it happens in the Temple in Jerusalem, and expounds upon it (see Fig. 5.5). Mites are little coins of the least valuable denomination, minted of a base metal such as bronze or copper. The woman’s pair of two such coppers, although minute in comparison with the presents of others, gains scope when measured against her net wealth: they are all she possesses. By tendering just two pieces of small change, the exceedingly poor widow utterly bankrupts herself. As a consequence, the proportionate value of her donation to God tops by far the large amounts of money contributed by richer folk.

Fig. 5.5 Alexandre Bida, The Widow’s Mite, 1874. Etching. Published in Edward Eggleston, Christ in Art; or, The Gospel Life of Jesus: With the Bida Illustrations (New York: Fords, Howard, & Hulbert, 1874), 293.

Our Lady’s Tumbler sets within the framework of dance, gymnastics, and juggling the same issues that are embedded in both biblical episodes, first of David’s dance and later of the widow’s mites. The resemblance between the medieval tale and the incident in the Gospels, although limited to their shared spirit rather than extending to the motif of dancing, appears to have struck at least one later interpreter. In 1918, the Irish writer Bernard Duffy published a coming-of-age novel entitled Oriel. Among other things, the book describes a priest, Dean James Joseph MacMahon. The fourth chapter, set in the novelist’s hometown, is narrated by an altar boy. References to Our Lady’s Tumbler neatly frame this section. Near the beginning of the chapter, the Dean subjects the youth to sweet-natured raillery about his dreams for the future. In the process, MacMahon admits that in his own adolescent days he had cherished an ambition to be a traveling entertainer who specialized in gymnastics. Somewhat earlier the good cleric had asked what the boy intended to be when he grew up. The young man had given two answers that in their antitheticality had made the priest double up in gales of laughter: “I think I’ll be a bishop” and “I think—I think a clown in a circus.” In the incident that caps the chapter, Oriel, who has been tasked with manning the collection box, feels shamefaced at having no coins to drop in. Instead of pocket money, he thinks himself virtuous for contributing an enameled button. The Dean, not knowing who made this deposit, admonishes the congregation sternly. After the boy confesses, the ecclesiastic responds by telling the story of Our Lady’s Tumbler, which he finds apt for both of them because of their youthful aspirations. As the chapter closes, the older churchman concludes that “the value of an offering is to be gauged only by the spirit in which it is offered.”

Such expressions of devotion may well up from many different drives within individuals, including dancers. Not all acts of dancing as performances of faith need to have had a text or ritual as provocation or inspiration. After all, they can arise from nearly universal human impulses. Thus, in a work of scholarship printed in 1923, an academic author on dance vouched for “the literal truth” of two related anecdotes, in which small children performed rhythmic steps or simple gymnastics before God or Jesus. Many physical performances have the aim of showing off, not solely for the Virgin. With complex anachronism, a volume of literary history brought out in 1948 referenced the jongleur of Notre Dame in describing an escaped French prisoner of war during the Napoleonic Wars. With his companions, the fugitive staged a performance of athletic feats, including jumping hurdles: “It’s the story of the jongleur of Notre Dame. The episode is one of the prettiest. The war then had these oases, or these pauses.”

Beyond reflexes that may occur to this or that type of person almost irrespective of the century or culture, we cannot rule out the specificity of local traditions. Christian qualms about dance were severe. Despite them, regional folklore and folkways retained their resilience. For all the gnawing doubts, this form of expression may have been accorded a place in quasi-religious rituals outside formal worship or even in the liturgy itself. Such customs can be onerous to recover from ancient and medieval times, since the literate who could set them down in writing were often either condescendingly uninterested in or actively antipathetic to them. On the whole, the ecclesiastical authorities managed to keep the practice out of churches and liturgical contexts, or to squelch it if it had somehow insinuated itself there anyway. Yet the suppression was never complete, especially outside houses of worship. Spain and Spanish-speaking America have a celebration called the Festival of the Crosses or May Cross in which dance often plays a role. A Spanish print from around 1875 captures a couple dancing in a courtyard before seated onlookers (see Fig. 5.6). In 1920, a researcher made an aside that referred to many Spanish children disporting themselves before the May altars in their own homes, in a ritual loosely comparable to a Maypole dance. How far back such rituals reach is at this point, and will abide forevermore, a matter of wide-open guesswork rather than absolute historical certainty.

Fig. 5.6 Dancers celebrate Cruz de Mayo in Spain. Albumen print. Illustration by J. Turina, 1875.

The medieval tale demonstrates dash and daring in depicting dance positively, as the object of reward from the Virgin herself. In contrast, in the Middle Ages, dancing was often presented by churchmen as a profane pastime, and was condemned for its deleterious character. Stephen of Bourbon, French Dominican of the thirteenth century, declared, “The devil is the inventor of carolers and dancers.” The best-known and longest-lived of anti-balletic exempla tells of the cursed dancers of Kölbigk. On Christmas Eve of 1017 or thereabouts, these women and men allegedly violated an interdiction against dance within church space during a service. To be specific, they made a racket as they danced in the round and sang in the churchyard. In so doing, they disturbed the Mass in their small town. When the parish priest shushed them, they turned a deaf ear (see Fig. 5.7). Ignored by the merrymakers, the minister eventually called upon God, pronounced a malediction, and execrated them. Through the pox he put on them, the miscreants were given a kind of homeopathic punishment for their profanity. For transgressing the sanctity of the space and ignoring the good father, they were prevented for an entire year from leaving the yard and from ceasing to sing and dance. After this living purgatory, the legend maintained that they were permitted to return to normal life. The tale is sometimes held to relate to ecclesiastical anxiety as ballads and carols spread at full bore. Christian ambivalence about dance appears nowhere more remarkably than in a short story by the Swiss author of poetry and fiction, Gottfried Keller (see Figs. 5.8 and 5.9). Entitled “The Little Legend of Dance,” the tale is the last of his Seven Legends from 1872. All of these accounts have settings in early Christianity. This narrative, based on one preserved in Gregory the Great’s Dialogues, recounts an episode in the life of Saint Musa. As a young lady, the future holy woman was reputed to have had only one fallibility: she suffered from an intractable mania for dance (see Figs. 5.10 and 5.11). She indulged her passion everywhere, even when walking to the altar or before the church door. Keller reports that once “when she found herself alone in the church, she could not refrain from executing some balletic moves before the altar, and, so to speak, dancing a pretty prayer to the Virgin Mary.”

At this juncture an elderly gentleman appeared, and she took a long and elaborate whirl with him. At the end, he introduced himself as King David himself, and he pledged her eternal bliss in cavorting (see Fig. 5.12). His only rider to the agreement was that for the rest of her life in the material world she renounce her hedonism, including dancing, and that she give herself over instead to penance and devotion. Musa consented to this stipulation, returned home, and took up an anchoritic existence in which she forwent all pleasures, most especially the balletic ones. Before too long, the girl fell ill and died, whereupon she enjoyed the delights of gamboling that the prophet had promised her (see Fig. 5.13).

Fig. 5.7 The cursed dancers of Kölbigk. Etching, 1674. Artist unknown. Published in Johann Ludwig Gottfried, Historische Chronick oder Beschreibung der Merckwürdigsten Geschichte, vol. 1 (Frankfurt, Germany: Merian, 1674), 505. Image courtesy of Universitätsbibliothek Düsseldorf.

Fig. 5.8 Gottfried Keller, age 54. Photograph by Jean Gut, 1873.

Fig. 5.9 Gottfried Keller. Photograph, before 1929. Photographer unknown.

Fig. 5.10 Title page of Gottfried Keller, Das Tanzlegendchen (Berlin-Charlottenburg, Germany: Axel Juncker, 1919).

Fig. 5.11 Musa dancing. Drawing by Hannes M. Avenarius, 1919. Published in G. Keller, Das Tanzlegendchen, 9.

Fig. 5.12 Musa speaks with King David. Drawing by Hannes M. Avenarius, 1919. Published in Gottfried Keller, Das Tanzlegendchen (Berlin-Charlottenburg, Germany: Axel Juncker, 1919), 13.

Fig. 5.13 Musa dances in heaven. Drawing by G. Traub, 1921. Published in Gottfried Keller, Sieben Legenden (Munich, Germany: Franz Hanfstaengl, 1921), 139.

The Virgin’s Miraculous Images and Apparitions

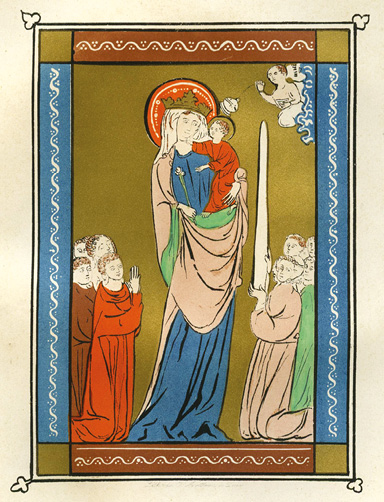

The Gospels do not brim with details of Mary’s life history, beyond the facts that she was a maiden who married Joseph, accompanied him to Bethlehem, and bore Jesus after conceiving miraculously. For her role in this procreation, the Virgin was hailed at the Council of Ephesus in 431 CE by the Greek epithet Theotokos, meaning literally “God-Bearer” but interpreted often as “Mother of God.” This edict helped to ramp up Marian devotion. In addition, it led eventually to recognition of Constantinople as the Theotokoupolis, or “City of the God-Bearer.” Legends and miracles gradually arose that documented subsequent interventions of the Virgin in the lives of human beings. The Mother of God steps on stage as the mediator of God’s mercifulness and as the surest advocate for uneasy souls. She proves able and willing to work miracles to spare almost any sinner who resorts to her. Narratives of miracles wrought by Mary are not unknown in the earlier Middle Ages in Western Europe, and in fact the contribution of what is now France to the stockpile of Marian miracle tales began early, in the writings of Gregory of Tours. But they metamorphosed into a major literary phenomenon only in the twelfth century and later, extant first in Latin prose and later in Latin verse and vernacular verse. Once again, the French-speaking region contributed in an outsized fashion.

The making of a miracle literature required extensive efforts. Monks, clerics, and performers gathered stories. In the process, they sometimes conducted the medieval equivalents of oral history or news interviews. Occasionally they may have spun the tales largely out of their own fancies. In any case, they were not aided in their work by recording devices beyond stylus and wax tablet, pen and parchment, or other such tools for note-taking. Since the wonders were often preserved and transmitted at first separately, others later bundled them into more or less coherent groupings. Later still, vernacular poets translated or adapted written collections from Latin or from unwritten intermediaries. In Marian miracles, both the quality and quantity of the prose and verse generated in the late twelfth and thirteenth centuries rate as nothing short of astounding. This holds true of texts in both the learned language and the vernaculars.

The wonders of most saints, set down posthumously, were attached to specific, physical shrines. The written accounts were customarily presented as historical documents, serving primarily to shore up the case for officially canonizing the martyr or virgin responsible for them. In contrast, the miracles of the Virgin were unhampered by the cumbersome dictates of papal canonization, since her sainthood was already unequivocal. Instead, they were generally literary compositions not tied to a single place. As the genre surpassed most other forms of hagiography, the Marian collection soaked up miracles that had been associated previously not with the Mother of God but with other saints.

Suppliants sometimes sought to be healed through the intercession of Mary—they could read and hear of many therapeutic miracles. All the same, her wonders tend much less to emphasize remission and recovery from physical ailments than salvation from what could be styled spiritual dilemmas. Finally, considerably fewer relics of the Virgin existed than of many other major saints, since her body had been taken into heaven at the Assumption. Although nail trimmings and hair ringlets are to be found, remains of direct contact with her generally came through relatively paltry pieces of clothing and drops of milk. Counteracting that scantiness, the Mother of God barged into the real world long after death through frequent apparitions. Many sightings took place thanks to images, either icon-like paintings on panels or representations in the round—that is, statuary standing free with all sides shown.

The assemblages of miracles that are known best today are in the spoken languages. To list only three examples, our thoughts turn first to the Miracles of Our Lady in medieval French verse, from about 1220, by the Benedictine monk Gautier de Coinci. A second would be the Miracles of Our Lady in Castilian verse, from about 1230, by Gonzalo de Berceo, secular priest of Rioja. He has just title to being the first Spanish poet known by name. His poem was based on a Latin text that may have been of Cistercian origin. A third would be Songs of Saint Mary in Galician-Portuguese, from about 1250, by King Alfonso X the Wise of Castile and León. This is to say nothing of various anonymous collections. These compendia amass hundreds upon hundreds of legends—for instance, King Alfonso the Wise’s anthology alone comprehends 360.

Compounding the impressive bulk of narrative is the effort invested sometimes in making the manuscripts vehicles for all the media that were capable of being recorded at the time. Thus, the most luxurious of the extant codices of the Songs has folio sides that are segmented into six panels, each of which exhibits a snippet of text accompanied by an illustration. A substantial proportion of the total word count, and number of the illuminations in the manuscript, is devoted to miracles that revolve around living images of the Virgin. The representations were icons and statues that somehow or other become animate. Further supplementing and enhancing wordcraft and artwork is musical notation. Yet even this kind of accounting evokes only a small corner of the picture. To cite the old aphorism, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts in these collections. Beyond being encyclopedias of the miraculous, the texts express passionate love for Mary. Furthermore, none of them merely translates a Latin source word for word. Rather, they interject commentary, both explicit and implicit, that delves into social issues that would not have occurred to or been relevant to the churchmen who wrote in the learned language. They reached audiences across the societal spectrum. Thus, the Songs may well have been intended for a courtly audience, whereas the Miracles may have been designed for performance before pilgrims as they partook of the hospitality of a monastery.

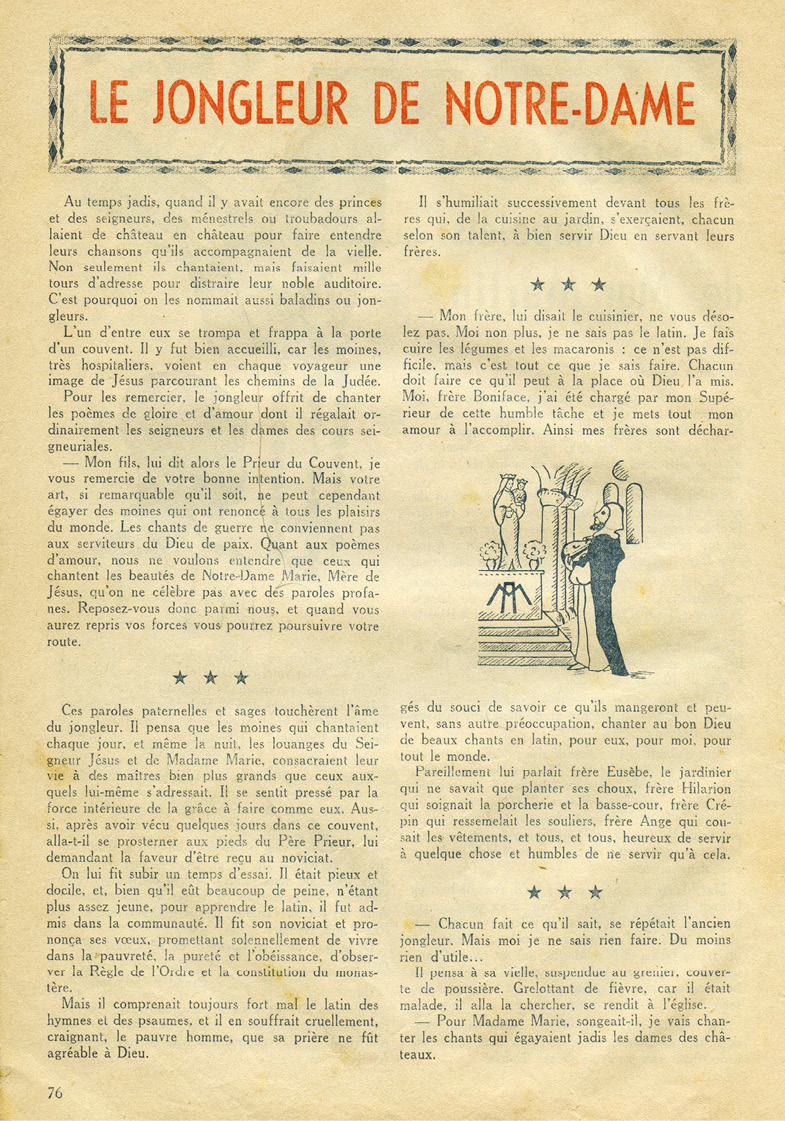

The Jongleur of Rocamadour

Analogues that manifest a near kinship, both chronologically and culturally, with Our Lady’s Tumbler can be detected in other Marian exempla and miracles. The earliest is probably a twelfth-century occurrence recorded first in the anonymous Latin prose Miracles of Saint Mary of Rocamadour. This narrative offers evidence for the importance of literature in writing down miracles and thereby promoting pilgrimage to specific locales. Later this specific shrine wonder relating to the Virgin received treatment in Old French verse by Gautier de Coinci. At the outset of his own version, the vernacular poet acknowledged his intimate familiarity with the prose in the learned language. Last but not least, the account was rendered into Galician-Portuguese by (or under) King Alfonso the Wise (see Fig. 5.14). The tale recounts an episode that is alleged to have befallen a jongleur from the German Rhineland community of Sieglar. According to the story, this Peter Iverni made music on his vielle in praise of the Virgin before the miracle-working statue of her in the sanctuary at the basilica of Saint Mary in Rocamadour in France. The element roc- in the place name, akin to English “rock,” refers to a crag. Considerable speculation has been made about the exact identity of the Amadour or Madour whose cognomen completes the toponym. He is often taken to have been an early Christian hermit who was ostensibly a retainer in the household of the Virgin, and was dispatched later across the seas from the Holy Land to the Alzou gorge, as a missionary to Gaul.

Fig. 5.14 Musical performers before the Virgin, as depicted in the Cantigas de Santa Maria (Codice Rico). Madrid, Real Biblioteca del Escorial, MS T.I.1., fol. 14v. Image courtesy of Real Biblioteca del Escorial, Madrid.

On this occasion Peter prayed to the Mother of God that, if gratified by his production of songs and melodies, she should reward him with either a consecrated taper from among those that combusted around her statue, or a piece of wax from it. That is to say, he petitioned for the turnaround of the usual pattern in which a devotee of the Virgin would bestow a votive candle upon her. In a trice, the petitioner’s wish came true. In repayment for the service done her, Mary prompted a taper to levitate and descend upon his musical instrument. In wonderment, an overflow crowd of pilgrims witnessed the airborne wax with its lighted wick. The episode filled them with hope. Like Peter, the worshipers performed pilgrimage and veneration. In him, they had a role model for the success of such performances in eliciting miracles.

At this point the story is still far from over. The official in control of caring for the church was a monk. Upon noticing the marvelous event, this Gerard grew irritated. Taking the fiddler unjustly to be a sorcerer, the testy sexton flounced over to the musician, seized the taper, and replaced it near the statue. Both the levitation and the confiscation were repeated, which made the official only more fed up: he had a meltdown. When the Mother of God caused the burning wick with its wax to boomerang and to alight on the musical instrument a third time, the miracle was proven definitively to be legitimate and celebration ensued. The bystanders who witnessed the wonder exclaimed in a lovefest for God (see Fig. 5.15). The jongleur, crying for joy, restored the votive. Every year thereafter, so long as Peter lived, he returned to the site of the original miracle to offer the Virgin a candle weight of more than a pound. The moralization that follows the narrative emphasizes that the monks and clerics tasked with singing would do well to emulate the red-blooded devotion of the jongleur in praying to God and his mother, in thanking them, and in extolling them.

Fig. 5.15 A taper miraculously alights upon a jongleur’s vielle, prompting wonder from bystanders. Illustration by Pio Santini, 1946. Published in Jérôme and Jean Tharaud, Les contes de la Vierge (Paris: Société d’éditions littéraires françaises, 1946), between pp. 130 and 131.

Reports of miracles entailing candles were not uncommon. The chapels and images that drew pilgrims, petitioners, and performers would have often been illuminated by the light of tapers. The flickering could readily have produced the impression of movement, and witnesses could easily have included individuals capable of singing, narrating, miming, or writing what was supposed to have happened. Sometimes it takes little imagination to guess how a press of wonder-hungry onlookers could have construed a normal occurrence as being miraculous. Take, for example, the monastery of Jesse, where a carpenter saw a statue of the Virgin and Child come to life. One night, the votive placed before the image relit itself twice and did not cease to burn after the beadle had doused it.

The location of the miracle at Rocamadour is apropos, since in the second half of the twelfth century and the early thirteenth century this site became a famed pilgrimage destination. If their health permitted, pilgrims were meant to proceed on their knees during the homestretch, the final steep ascent from the thoroughfare up to the shrine. In 1170, King Henry II of England made the trek there in search of cures for physical maladies and political misfortunes. Of relevance for our literary purposes, Caesarius of Heisterbach, the Cistercian author of exempla, was moved to enter his cloister as part of a conversion process that involved a pilgrimage to this sanctuary in 1199. At the same time, it bears note that the jongleur in this miracle manifests no desire to enter the monastery in the locale. Rather, he remains from beginning to end a layman. In a further difference from Our Lady’s Tumbler, he is not a dancer or gymnast but an instrumentalist and singer. Additionally, he both requests and observes the miracle that takes place.

The Virgin herself is not reputed to have made any appearances at Rocamadour, although the shrine possessed a sample of her treasured milk. All the same, her image in the house of worship there elicited particularly strong attachment and (as we have seen) was ascribed miraculous powers (see Fig. 5.16). The Madonna at Sainte-Marie of Rocamadour is a wooden image of the Virgin and Child. The composition is not unusual for the period, since it depicts Mary supporting the infant Jesus on her left knee. This type of statue, with its very formal posture, is known as a maiestas, or “majesty.” An alternative name for the Mother of God in the same pose is “throne of wisdom.”

Fig. 5.16 Postcard depicting Rocamadour’s “Chapelle miraculeuse” (Saint-Céré, France: J. Vertuel, 1977).

If the Rocamadour Madonna’s austere composition conforms to the compositional norms of its day, it displays a relatively rare feature in its coloration. As the statue now exists, Mary is portrayed as having swarthy skin (see Fig. 5.17). For obvious reasons, a representation of this sort is known as a Black Virgin or Madonna. Such dark-hued images in the round are customarily treated as distinct phenomena from ones that are not black. Although paintings in which the Mother of God has a blackened hue may also be designated likewise as Black Madonnas, it makes sense to examine the pictural and sculptural media separately. The best known of such paintings would be an icon, that is, a depiction on wood. The original was supposedly made of wax mingled with the ashes of martyred Christians. This artwork was preserved in a Marian shrine located in the section of Constantinople, modern Istanbul, that was called Blachernae. From its location the depiction became known technically as the Blachernitissa. In Byzantine coins issued between 1055 and 1057, a representation of the Virgin has an inscription identifying her by this designation. The difficulty lies in ascertaining whether the numismatic type corresponds with the famous image or with another icon or some other sort of decoration in the church of Blachernae (see Fig. 5.18).

Fig. 5.17 The Black Madonna of Rocamadour. Photograph by Martin Irvine, no date. Image courtesy of Martin Irvine. All rights reserved.

Fig. 5.18 Mary as Blachernitissa on Byzantine coinage. Coin (obverse), two-thirds miliaresion of Constantine IX Monomachos, 1075–1077. Washington, D.C., Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. Image courtesy of Joe Mills. All rights reserved.

Mysterious in their misty origins and murky meanings, the Black Virgins have exercised a special fascination since the Middle Ages. The color coding that Western societies have often imposed upon their citizens has been extended to their statuary. Among the caveats in order, one is that the demographics of such Madonnas have changed. Not all representations categorized as having this color today were dark at all or as black when they were first created or earlier mentioned. The chromatic change has taken place in the opposite direction as well: the Church has sometimes replaced, without ado, older Black Virgins with newer white ones. Then again, older does not mean original: what has darkened may have once been lighter. Candle soot and other grime, natural and unnatural aging of paint and other materials, additional layers of varnish, and replacement of lighter with darker images have all produced modifications. In any event, for a millennium the most important of these dusky Madonnas as a pilgrimage destination has been the Black Virgin at Santa Maria de Montserrat. Located less than fifty miles from Barcelona as the crow flies, the Benedictine abbey was founded there in 1025. The site’s jagged-edged topography gave rise to the name “sawed mountain” of both mount and monastery in the language of the region, Catalan. Various hypotheses have been advanced to explain the coloration of these Madonnas. For example, what could be called the “holy smoke” theory holds that these images could have grown discolored inadvertently. They could have been fumigated by the acrid fumes of candles and lamps in ordinary worship, or by pungent fire when churches burned. (If so, the carvings have become hidden behind a permanent smoke screen.) Since many legends surrounding them claim that they were unearthed mysteriously by animals or shepherds in the wild, their color could have resulted from exposure to the elements or burial. Alternatively, they could have been intended to be black from their creation, to acknowledge the swarthiness of women who were familiar where they were originally carved. In some cases, they could have been fabricated from material that was naturally dusky from the beginning, while in others, they could have been made of wood that darkened as it aged. Whatever the reason for the blackness, the Black Virgin of Rocamadour was made the totem of the site. The figure was recorded first in the seal of the Benedictine priory and later in the special lead token that pilgrims sewed as a badge onto clothing and hats (see Fig. 5.19).

Fig. 5.19 A pilgrim’s badge depicting the Black Madonna and child. Metal badge, late twelfth to early thirteenth century.

Although the parallelism is inexact, the miracle of Rocamadour shows many parallels to Our Lady’s Tumbler. In both stories a lay entertainer merits the special favor of the Virgin by putting on a show before a Madonna within a famous institution dedicated to her, the Mother of God accepts the service, and an insentient object moves miraculously to signal her amiable disposition toward him. Also, in both narratives the professional has an antagonist from the religious establishment where he delivers his performance, in one case a sacristan and in the other a monk. In the last stage, the performer is vindicated. Both tales signal that ecclesiastics have no monopoly on the quality of veneration. With her discernment, Mary may grant her favor to the sincerity of a layman over the soul-destroying professionalism of a monk or cleric. Iconographically, representations of the jongleur can form eye-catching tableaux. The fiddler cradling his instrument can echo the Madonna dandling the Child.

Small wonder that in one of the five manuscripts of the medieval French Our Lady’s Tumbler, our poem follows immediately upon a version of this Rocamadour miracle tale by an anonymous poet. The analogies between the tales of Peter Iverni and the nameless tumbler are strong. In fact, during the early twentieth-century heyday of Our Lady’s Tumbler—when literary, operatic, and even cinematic re-creations of the story were ubiquitous—a French daily cultural newspaper ran an account of the Rocamadour miracle on its front page, under the headline “The Jongleur of Our Lady: The True Legend.” In the English-speaking world, an early volume of translations from medieval French contains Our Lady’s Tumbler as well as Gautier de Coinci’s version of the Rocamadour tale. But why stop dead with just this one parallel? Another close analogue is to be found. Set within an even larger framework, Gautier’s miracle and Our Lady’s Tumbler can be seen to flank another spellbinding narrative that belongs very much in the same company, the miracle of the Holy Candle of Arras. If nothing until now has kindled your interest, this scintillating version should make the sparks fly.

The Holy Candle of Arras

It is better to light a candle than curse the darkness.

Fig. 5.20 Holy card depicting the miracle at Arras (Bruges, Belgium, ca. 1890).

Above all, in the motif of the taper and in the character of the jongleur, the story about the miracle of the performer before the Madonna of Rocamadour relates loosely but intriguingly to the Marian miracle of the Holy Candle of Arras (see Fig. 5.20). This other wonder set up a ménage à trois that triangulated the Virgin and two entertainers. The events recounted in the legend reputedly took place in the opening years of the twelfth century, but they are not documented in extant texts until more than a half century later. The action in the story centers upon the northern French city within the bosom of a region called the Artois. In both the municipality and the region, the Picard dialect prevailed. The general backdrop is a citizenry beleaguered by a plague of ergotism. This poisoning, with cramps, spasms, and gangrene as its chief symptoms, is recognized now to result from consumption of rye and other cereals contaminated by ergot. In the Middle Ages, what caused this fungal disease stayed in doubt. The populace felt even more at a loss about workable medical treatments than it did about the causes. As a result, many concluded that the pestilence inflicted divine retribution for sin: sweet justice. They believed that one of the best remedies lay in appealing to Mary for mercy through her intercession with Christ.

The chief characters in the miraculous tale are two jongleurs. They became implacable enemies after the one, Pierre (but often called by the stage name Norman), slew the brother of the other, Itier (see Fig. 5.21). The Virgin, a beauty dressed in white, manifested herself to them in separate but simultaneous visions, instructing them to betake themselves to Arras, which was ravaged by ergotism (see Figs. 5.22 and 5.23). They were to find Bishop Lambert in her church there, iron out their differences before him, and keep vigil on Saturday. At midnight, a woman was to appear and give them a taper, which became known as the Holy Candle. The cylinder, alight with heavenly fire, would drool wax. In a kind of homeopathic medicine, when diluted in water the drippings could be drunk or drizzled to heal those burning from ergot poisoning.

Fig. 5.21 “Normand kills Itier’s brother in a quarrel.” Illustration, 1853. Published in Auguste Terninck, Notre-Dame du Joyel, ou Histoire légendaire et numismatique de la chandelle d’Arras… (Arras, France: A. Brissy, 1853), 111.

Fig. 5.22 “In a vision, Itier receives the order to go to Arras.” Illustration, 1853. Published in A. Terninck, Notre-Dame du Joyel, ou Histoire légendaire et numismatique de la chandelle d’Arras…, 111.

Fig. 5.23 “Normand receives the same order.” Illustration, 1853. Published in A. Terninck, Notre-Dame du Joyel, ou Histoire légendaire et numismatique de la chandelle d’Arras…, 111.

Fig. 5.24 “Normand makes his prayer at the door of the cathedral.” Illustration, 1853. Published in A. Terninck, Notre-Dame du Joyel, ou Histoire légendaire et numismatique de la chandelle d’Arras…, 111.

Fig. 5.25 “The Bishop Lambert reconciles Itier with Normand.” Illustration, 1853. Published in A. Terninck, Notre-Dame du Joyel, ou Histoire légendaire et numismatique de la chandelle d’Arras…, 113.

Fig. 5.26 Mary appears to the bishop and jugglers. Illustration, 1876. Published in Le Monde illustré (1876), 356.

On the following day, both men made a beeline as bidden to the Artesian cathedral of Notre-Dame. Norman arrived first (see Fig. 5.24). Upon hearing his claim, the prelate believed that the fellow was being true to his trade. Since jongleur is cognate with joker, Norman must have been jesting. Then Itier showed up and explained his identical experience and mission. Even so, Lambert remained leery. In his view, the two entertainers were colluding in a prank. Itier, who had not known that Norman had undergone the same vision, made clear that he would not be in the least inclined to pair up with his colleague. In fact, he exclaimed acrimoniously that he would like to run Norman through with a sword for having killed his sibling. At this juncture, the two foes were poised to settle their differences of opinion through physical violence. Happily, Lambert soon had them holding out olive branches: what threatened to become mano a mano became instead a handshake (see Fig. 5.25).

What happens next flies in the face of the old adage “The lights are on, but no one is at home.” As all three men prayed in the church, Mary wafted down from the heights of the choir, cradling in her hand a candle flaming with heavenly fire (see Figs. 5.26 and 5.27). She gave the cylinder to them. With water in which they had dripped drops from the taper (see Fig. 5.28), the three began at once zealously to cure the infirm (see Figs. 5.29 and 5.30). The legend of this thriller held that on the first night, with excitement truly at a fever pitch, 144 of the afflicted were healed. In this account, the jongleurs do not play or perform to achieve the miracle, and the Virgin’s intercession comes about in a vision rather than by moving through the go-between of an image.

Fig. 5.27 “The Holy Virgin brings the miraculous candle.” Illustration, 1853. A. Terninck, Notre-Dame du Joyel, ou Histoire légendaire et numismatique de la chandelle d’Arras…, 113.

Fig. 5.28 “The bishop blesses the water where the drops of the candle fall.” Illustration, 1853. A. Terninck, Notre-Dame du Joyel, ou Histoire légendaire et numismatique de la chandelle d’Arras…, 113.

Fig. 5.29 “Healing the sick.” Illustration, 1853. Published in A. Terninck, Notre-Dame du Joyel, ou Histoire légendaire et numismatique de la chandelle d’Arras…, 113.

Fig. 5.30 Interior view of the Cathédrale d’Arras. Drawing, 1853. Published in A. Terninck, Essai historique et monographique sur l’ancienne Cathédrale d’Arras (Paris and Arras, France: La Société de Saint-Victor, à Plancy [Aube], 1853), between pp. 42 and 43.

After the curative miracle, Itier and Norman allegedly started a society. Called the Brotherhood of the Holy Candle, this lay religious guild was instituted so that its members could serve as watchmen for the waxy relic. They also commemorated the miracle, which of necessity entailed honoring the Virgin (see Fig. 5.31). The confraternity of jongleurs existed from around 1175 until 1792. Without going into the particulars of this group, it is worth pointing out that guilds for minstrels took firm shape only long after the twelfth century. Gradually, such performers became more settled through attachment to royal courts and to the households of other notables. As they became less transient, they gained regular incomes and took to wearing distinctive livery. Such costumes remain with us in popular images of clowns and jesters. To house the candle, the members of this fraternal organization eventually constructed the chapel of Notre Dame des Ardents. In the Latin form of her name, this Mary is likewise Our Lady of the Fevered. She is customarily portrayed with a taper. The Latin designation of the group is written out so as to emphasize in its final two letters VM, the initials of Virgin Mary (see Fig. 5.32). Alongside the chapel stood a distinctive stone tower, which became popular as a pilgrimage site (see Fig. 5.33). The medieval structure was built to have the aptly tapered cylindrical form of a candle. The construction survived until pulled down by a mob during the iconoclastic upheaval of the French Revolution.

Fig. 5.31 The Holy Candle. Miniature, fourteenth century. Private collection. Reproduced in Auguste Terninck, Notre-Dame du Joyel, ou Histoire légendaire et numismatique de la chandelle d’Arras (Arras, France: A. Brissy, 1853), 99.

Fig. 5.32 “Domina Nostra Ardentium.” Illustration, 1910. Published in Cavrois de Saternault, Histoire du Saint-Cierge d’Arras et de la Confrérie de Notre-Dame des Ardents, 3rd ed. (Arras, France: La Société du Pas-de-Calais, 1910), frontispiece.

Fig. 5.33 “Vue perspective d’une partie de la petite place d’Arras, vis à vis l’hôtel-de-ville.” Drawing by Joseph Victor David, 1773. Reproduced in Cavrois de Saternault, Histoire du Saint-Cierge d’Arras et de la Confrérie de Notre-Dame des Ardents, 3rd ed. (Arras, France: La Société du Pas-de-Calais, 1910), 41.

For what it is worth, there would not be much challenge in formulating a Freudian interpretation here. The large actual candles, the reliquary, and the lapidary tower from the Middle Ages are all phalliform. Furthermore, the language of Marian miracles and Marian devotion is hardly destitute of amatory elements to connect male devotees with a highly feminine Mary. But sometimes, to ring a change upon the famous saying ascribed again and again to Sigmund Freud, a candle is just a candle. Or, to take the thought as formulated by the American horror novelist Stephen King, “Sometimes a cigar is just a smoke and a story’s just a story.”

The confraternity has a neatly twofold nexus with Our Lady’s Tumbler. Both the professional occupation of the performers who made up the guild and the Marian nature of the miracle at the root of their foundation legend make unsurprising that the Festival of Our Lady of the Fevered is conflated to this day with the “jongleurs de Notre Dame.” What further relevance does the foundation legend for the confraternity of jongleurs at Arras have for Our Lady’s Tumbler? When the poem was composed, such entertainers still lacked any formal organization or institution to support them collectively—they were cats waiting to be herded. In early medieval society they had been marginalized and often cast out. They belonged to a seamy underbelly that encompassed beggars, ladies of the night, and petty criminals. In the fullness of time, jongleurs turned sedentary, professionalized, and concentrated on skills that qualified them as minstrels—a term that they would have had good reason to prefer when describing themselves. Simultaneously, they moved by degrees toward being able to establish group identities along the lines of other craftsmen. In so doing, they naturally modeled their new professional unions on those found in existing crafts. In other words, they formed guilds. In their case, they were devoted to the shared pursuit of waxing poetic. In the transitional period between peripheralization and institutionalization, the jongleurs still had no mechanism for achieving individual stability within a collective. This lacking may explain why so many performers of this type entered monasteries, first especially Cistercian ones and later Franciscan friaries. Such groups afforded them a field day, their only means of belonging to a fixed collectivity. The tale of Norman and Itier may be untangled not only as a Marian miracle, but equally as a social parable that urges overcoming individual differences for the common good. The explication could even be stretched to produce a reading of the story as a foundation myth for what would be considered today unionization.

The jongleurs in the tale of Arras are musicians, who could find overlapping interests and bond together to protect them. By comparison, the physical performers remained poor pariahs. Within the monasteries too, former entertainers faced condemnation if they could not segue from bodily movement to voice and instruments in their performances. One lesson latent in Our Lady’s Tumbler is the mistrust of physical self-expression and entertainment. The Virgin showed herself far more understanding than did the monks about the antics of the converted tumbler. Medieval churches, especially cathedrals, witnessed many forms of conduct that would appear decidedly incongruous and indecorous today. Particularly where pilgrims congregated, much behavior that nowadays would be permissible only on the streets played out instead within places of worship. But the dividing line between the acceptable and unacceptable may have run between music—even instrumental music—and dance.

The Pious Sweat of Monks and Lay Brothers

Genius is one percent inspiration, ninety-nine percent perspiration.

Beyond the miracle of Peter Iverni or that of the holy legend of Arras, other exempla and legends relate to Our Lady’s Tumbler not by having as the central character a professional entertainer but by involving a specific narrative motif. For instance, an exemplum attested in no fewer than five different versions shows Mary as she comforts those who are sweating. We have seen how the legendary Veronica sought to take the edge off the suffering of Jesus when he was en route to the crucifixion and came away with a miraculous memento that became the main motif of the episode. Here, the wonder is the Virgin’s activity in succoring monastic devotees as they ooze sweat or sniffle tears from the relevant glands. Where miracles induced by perspiration enter the picture, medieval authors and audiences imposed no compulsion to take the proverbial grain of salt.

One form tells of a twelfth-century brother of Clairvaux. This Rainald would watch admiringly as his fellow Cistercians toiled in the fields. Even brethren of noble birth pitched themselves into the task. Once he had a vision in which the Virgin, her cousin Elizabeth, and the follower of Jesus named Mary Magdalene paid a visit to the brothers as they labored in the meadows. Another version of the same story relates that the miracle took place while the white monks of Clairvaux were reaping in the valley. The Virgin, her mother Anne, and Mary Magdalene swooped down in a great flood of light (here the meaning of the toponym Clairvaux in French merits mention: “Bright Valley” or “Valley of Light”). After making their free-fall, the three women wiped the sweat from the brows of the harvesting brethren and fanned them with the arms of their garments. In a much later telling, a long-in-the-tooth knight who had become a brother at Clairvaux saw one of the three, a beautiful young woman, greet each brother, give him a kiss and hug, and sopped the sweat from his sautéed brow with a linen cloth. In the thirteenth century, a monk of Villers in Brabant witnessed the Virgin, in the company of Mary Magdalene, fan the toiling brethren and pat away their perspiration with her sleeve.

At the Cistercian abbey of Heisterbach near Cologne in the Rhineland, Caesarius claims to have been so deeply moved upon first hearing this exemplum that in response he entered the monastery. In his account, the Virgin Mary visited with Anne as the monks of the abbey worked in the fields. The two saintly women daubed the men’s brows and dispatched a breeze to cool them. Between 1219 and 1223 Caesarius served as master of novices. During this stretch he composed his own collection of miracles, chock-full of exempla (746 of them). The twelve books, entitled “Great Dialogue of Visions and Miracles,” are presented as a dialogue between a probationer and the author himself, in his magisterial capacity (see Fig. 3.12). Through the illustrative stories, the writer aimed ultimately to contribute to the training and formation of monks, with all due attention to the special circumstances of lay brothers too. He devoted the seventh book to tales relating to Mary. Ample room existed for strong overlap between the exempla incorporated into such collections and records of apparitions of the Virgin to Cistercians. Eight such apparitions are known to have befallen the brethren of Clairvaux alone in the second half of the twelfth century. The Mother of God visited the “bright valley” continually.

Beyond the five interrelated exempla, in other cases the Virgin also undertakes an antiperspirant role. One appears in the medieval French verse of Gautier de Coinci. His voluminous Miracles of the Virgin extends over roughly 30,000 verses. In this poem he tells of one miracle involving a Carthusian brother which exhibits many striking similarities to Our Lady’s Tumbler. The poet relates this tale very briefly. With the omission of the moralizing coda, it totals a mere sixty-five verses. To date, the exact relationship between the two miracles has not been unsnarled, although Gautier seems likely to have known and been inspired by some form of Our Lady’s Tumbler. Probably he read or heard a version along the lines of what has survived. Then again, he may have encountered an iteration of it that was never written down. In this case, the meager synopsis in the Latin exemplum could well be only the tip of an iceberg of tellings and retellings, and writings and rewritings, that has melted out of our grasp. The author himself claims at the outset to have read a version of the miracle about the Carthusian, but if a text existed, it too has evaporated.

In Gautier’s miracle, a monk of the order in question remains in church after all the daily and nightly offices. There he devotes himself with intensity and persistence to mortifications of prayer and devotion. In each session he prostrates himself on bared knees fifty to a hundred times as he prays before an image of the Virgin. Despite having peeled off the leggings that would have shielded his joints, he exerts himself so much that runnels of sweat stream from him. One of the brethren spies on him one night to see what he does in the chapel after the office. At the end of the ritual, his fellow monk sees Mary dismount from heaven to stroke with a snow-white veil the perspiring face of the devout Carthusian. After revealing to the prior and to his devout comrade the miracle that he witnessed, the brother dies. A second episode is recorded in the Song of the Knight and the Squire, by Jehan de Saint-Quentin. The poet, a self-described clerk, composed songs in Picard that deal with many topics, but especially frequently with Marian miracles. He seems often to have followed oral or at least otherwise unattested sources. In the poem under consideration, a castellan, the commander of the castle, looks on unperceived at a poignant scene. The Virgin dries with her kerchief the teardrops welling from the eyes of a repentant knight while he gets down on his knees before her. A related third form of the legend is transmitted by Gautier de Coinci. This one pertains to the icon of Our Lady of Saydnaya, a city in the mountains near Damascus in Syria. The convent to which the icon belonged supported a cult that was a going concern in the late twelfth century. The miracle tells of a Carthusian whose extreme devotion elicits a similar display of compassion from the Virgin. In this case, the monk kneels so long in prayer on bare knees before the Madonna that wetness courses down from his brow. At this, Mary comes down from heaven to dry his face with her soft, snow-white hand towel.

These many other miracles of the Virgin add both inevitability and mystery to the successful formula of Our Lady’s Tumbler. Probably loosely under the influence of the Veronica legend, the idea arose that the Mother of God might concern herself with assuaging the toils—or, more particularly, the sweat and tears—of mere mortal monks as they executed either fieldwork or choir devotions. Her governing principle appears to have been “no sweat.” On a higher plane, another component in the story was sheer love. The sheerness refers partly to fabric, while the affection derives its exceptionality from being directed to a statue.

The Love of Statuesque Beauty

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

In Our Lady’s Tumbler the protagonist conducts the strangest of charm offensives. He strips down to the lowest and most intimate layer of clothing as he exerts himself to the utmost to be obsequious to the woman he adores. The proverbial saying “worse for wear” seems here to find its inverse in the concept of being “better for not wearing.” The scene, when described in this bare-bones way, brings to mind other acts between lovers.

The incident is also curiously reminiscent of another famous Marian miracle, recounted by Gautier de Coinci and others. In it a youth, seeking a secure place for his engagement ring before engaging in an athletic event, deposits it on the finger of a statue of the Virgin. He finds the image “so fresh and beautiful… a thousand times more beautiful than she who gave this ring” that he plights his troth of lifelong service. He is soon set to renege upon his pledge. On the night after he has uttered his official “till death do us part,” the Virgin intervenes as an animate anti-aphrodisiac and interposes herself between him and his bride. The double-cross does not aim for Mary to consummate the wedding in place of the newlywed woman—in other words, the substitution is not the motif known as the bed trick. Rather, it amounts to a means of preserving chastity. The story ends with the young man joining the monastery, as he had pledged. In this tale, an adolescent takes the habit after an encounter with a Madonna, who turns out to be both seducing and sedating. The sequence of events conforms to a narrative line used much earlier by similar accounts in which fabric and sweat are not always key components. Ultimately, the Marian tale appropriates elements from these other accounts, which have the boy becoming affianced to a sculpture of Venus. Many versions of the Venereal tale, including some that transmogrify earlier ones, have been told over the centuries. The most famous may be the 1837 short story “The Venus of Ille” by Prosper Mérimée (see Fig. 5.34). Eventually, the miracle has loose analogues in reality. In some cases, a young man would make an oath of celibacy by donning a ring and putting an identical one on a carving of the Virgin.

The still bigger picture is stories, such as the legend of Pygmalion, in which a man falls in love with a sculpture. Loosely related too are equal and opposite tales, in which to beguile her beloved a woman assumes the guise of an effigy. The archetype here would be the myth of Pasiphaë, a daughter of the sun god Helios, who is hexed to fall in love with a bull. To copulate with the beast, she enters a wooden cow that her beloved bovine mounts. The cross-species coupling and very real insemination achieved by the ploy of this decoy leads to the birthing of a monstrous hybrid, the Minotaur.

Fig. 5.34 Front cover of Prosper Mérimée, La Vénus d’Ille / La double méprise / Les âmes du purgatoire, illus. Mario Labocetta (Paris: Nilsson, 1930).

Fig. 5.35 Postcard depicting the Volto Santo in the church of St. Martin, Lucca (Milan, Italy: Cesare Capello, early twentieth century).

Love of manmade representations remains with us. The ability of individual sculptors to hew marble into lifelike form may have dwindled from the glory days of ancient Greece and Rome, but machines enable the mass manufacture of ever more realistic and even hyperreal three-dimensional replicas. Stories of inflatable dolls, mannequins, and robots proliferate, to say nothing of narratives in which disembodied simulations of human characters play leading roles. Yet these other tales of images evidence only superficial overlap with medieval Western ones. Our investigations need to turn elsewhere for further analogues to Our Lady’s Tumbler.

The Holy Face of Christ and Virgin Saints

If we venture beyond miracles attributed specifically to the Virgin Mary, or rather to thaumaturgic images of her, the most relevant parallel emerges in a wonder ascribed to the Holy Face. This statue hangs upon a crucifix at the church of Saint Martin in Lucca (see Fig. 5.35). It became the object of the first cult devoted to a carving of Jesus on the rood. This wooden pictorialization shows the crucified Christ triumphant, wearing an ankle-length tunic, This specific representation of him standing against the cross became popularly renowned, being mentioned already as the habitual oath (“by the Face at Lucca”) of King William Rufus in the late eleventh century. Three hundred years later it is still assumed to be common knowledge. At one point in Dante’s Commedia, demons cry out to a sinner from the sculpture’s adoptive hometown: “This is no place for the Holy Face!” Piers Plowman, the eponymous pilgrim in William Langland’s late fourteenth-century alliterative poem, vows by it that at least metaphorically his pilgrimage consists in plowing. As such mentions certify, the image was widely revered throughout Western Europe. Among other things, the Lucchese artifact is attested over a large area on pilgrims’ badges of lead.

Medieval legend maintained that the statue’s countenance was crafted by an angel, whereas all the rest was sculpted by Nicodemus. The story merits being put into an easily assimilated recapitulation. According to the Gospel of John, this Pharisee became a disciple of Jesus. After the crucifixion, he assisted Joseph of Arimathea in deposing Christ from the cross and laying him in the tomb. Thereafter he set out, at the urging of God, to shape an image of the Christian savior on the crucifix. While the would-be sculptor slept, a divine emissary completed the face. Nicodemus hid the precious sculpture in a cave, where it remained closeted for centuries. The larger than life-size effigy of cedar was miraculous not merely in its creation but also in its subsequent transportation. It reputedly arrived in Lucca in the eighth century thanks to the enterprise of two Italian bishops (see Fig. 5.36). A procession known as the Illumination of the Holy Cross still takes place annually. In it, participants carry lighted candles through the streets to the church.

The rich dossier of miracles about the Holy Face contains one highly relevant to Our Lady’s Tumbler. This legend originated in the twelfth century, to judge by its style and content. In the key Latin form, a poor young man from Gaul stops on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem to see the carving in Lucca. Praying and weeping amid the great huddle of pilgrims as they make offerings, he thinks that he will confer on her his only good in a no-charge performance: he will sing hymns to the Holy Rood while accompanying himself on the musical instrument, a fiddle, he has on his arm. As a sign of favor to the suppliant, God demonstrates his appreciation by causing the figure of the Holy Face to look down at the musician and to let fall a silver slipper from its right foot into his lap. After leaving the chapel with the footwear, the unnamed young man returns with it, but the miracle is confirmed by the circumstance that it will no longer fit on the foot of the image. The plight is a near opposite of the pivotal episode in Cinderella.

Fig. 5.36 Postcard reproduction of Vincenzo Barsotti’s L’arrivo a Lucca del Volto Santo (Lucca, Italy: Archivio di Stato, early twentieth century).

Fig. 5.37 Jenois before the Holy Face. Miniature, fifteenth century. Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Palatinus Latinus 1988, fol. 1r.

The unique medieval French telling of this miracle appears in a large mishmash of verse texts that was probably compiled by a monk of the Benedictine monastery of Saint Bertin in France. The date of composition has been disputed. The crucial personage in the account is a minstrel often named Jenois, who plays in vain to earn his sustenance. Although seven hundred people pass by him, no one treats him to even one coin. Then, he enters the church where the Holy Face had only recently arrived. After finding out that the image represents Jesus Christ, he begins to sing to the accompaniment of his string instrument, the vielle (see Fig. 5.37). The poem remains reticent about the controversy over the playing of musical instruments of any sort within the church. Whether fiddles or organs, everything beyond the human voice (and even at times it too) has been suspect. In any case, the performance sets in motion a miracle. First, the sculpture, inspired by the Holy Ghost, becomes animate. Then, it loosens one of its feet from the nails holding it to the cross, stretches it out, and kicks the shoe, encased in silver and gold and encrusted in precious stones, to the jongleur. When the young man goes off to eat, the bishop enjoins him to return, but tells him that he may keep the trove if the miracle is repeated. At this point, the image fills with spite, loses its temper, takes back the foot covering, and orders that it not be taken from the jongleur unless with substantial reparation, which is provided. Jenois is now able to dine and offers a repast to the poor of the city, to whom he also allocates the wealth he has acquired. Afterward follows what qualifies as a celebratory outcome only in the unusual confines of medieval hagiography. The performer resumes his pilgrimage, but is captured by pagans, tortured, and decapitated. His body is subsequently venerated in Rome.

In all its forms, the story has encoded within it an argument to validate largesse to entertainers in recompense for their performances, at least when they sing on pious topics. This dimension of the tale is discussed unreservedly in the medieval French Aliscans. This long “song of heroic deeds” from the second half of the twelfth century tells of the pitched battle and bloodletting from which it takes its name. At one point in the narrative, an itinerant jongleur endeavors to elicit generosity from his audience by singing an editorial. He exhorts noblemen not to listen to entertainers of his sort unless they stand ready to open their wallets. To prove his point, he cites the beneficence of the Holy Face of Lucca. All ought to cherish performers for the joy they seek and their love of singing. A wayfaring professional could also take the episode to heart as betokening the miracles that God could deign to perform for even the humblest spectators.

Not everyone was willing to take the miracle tale on faith and deem it plausible. Overt incredulity is recorded at the latest by the beginning of the thirteenth century. The nagging doubts are likely only to have been magnified when the story underwent a still stranger transmogrification at a later stage. However improbable the sex change may seem, the person crucified was alleged to have been a king’s daughter. To avoid a forced marriage that would necessitate her violating the vow of chastity she had taken, the nubile girl prayed for help from heaven. Whether she was dysphoric at her physiological sex or not, we cannot know. Yet she was horrified by the prospect of married life. She spared herself from a wedding by undergoing extemporaneously a partial transgender transformation. In what is known clinically as hirsutism, the damsel suddenly sprouted such scruffy and unkempt facial hair that she became unmarriageable. Her condition made her the medieval anticipation of the later standard in two-bit sideshows, the bearded lady. At this point the would-be suitor soured on the idea of monogamy (at least with her) and withdrew his proposal. The father flew into a rage and put his own daughter to the cross. The account goes on to merge with that of the Holy Face, with a further miracle involving a jongleur and the shoe from the image of the martyred (and bearded) virgin. The jury is still out on the reasons for which these disparate motifs would have originated and amalgamated. Face up to it: if ever a case called for a close shave by Occam’s razor, this would be the one. Of the many accounts, the most representative one may be the most famous. In 1812 the Brothers Grimm incorporated a version into the first edition of their so-called fairy tales, drawing upon a collection of exempla from 1700. In this version, the woman in question is called Saint Kummernis, meaning “care” or “anxiety” (see Fig. 5.38). Among sundry other names that have been attached to the mostly female leading character, Wilgefortis supposedly derives from the Latin signifying “strong maiden.” The tale is widely attested between the mid-fourteenth and mid-nineteenth centuries: approximately one thousand records of it survive in texts and images. The best-known representation may be a 1507 woodcut produced in Augsburg by Hans Burgkmair the Elder. The artwork juxtaposes a narrative in text and an image that shows the fiddler kneeling before the Holy Face, identified as “The Image at Lucca” (see Fig. 5.39). The legend continued to be illustrated for centuries in art, even folk art. A last major expression of the tale was literary, in an 1816 ballad. Here, the poet assigned to Saint Cecilia the place formerly spoken for by Kummernis. In the poem, an impecunious violinist moves an image of Cecilia so deeply that the saint tosses him her golden shoe. Although this gesture leads to his being sentenced to death, he is saved from execution when she also bestows upon him the matching item of footwear (see Fig. 5.40).

Fig. 5.38 Unknown artist, St. Kümmernis, 1678. Oil on panel. Museum im Prediger, Schwäbisch Gmünd. Image from Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kuemmernis_museum_schwaebischgmuend.JPG

Fig. 5.39 St. Kümmernis. Woodcut by Hans Burgkmair, 1507. Augsburg. Image from Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Burgkmair_Kuemmernis.JPG

Fig. 5.40 A fiddler plays before the Virgin, with a crowd assembled. Drawing by Herman Kanckfuss, 1871.