17. The Secret

© 2022 William St Clair, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0136.17

How could it have happened that, among all the deaths, injuries, and miseries of the people, the severe damage to the churches, and the almost total destruction of the houses of the town, that every one of the twelve main ancient monuments of Athens still stood? How had the Ottoman army, in a siege of ten months, during which they fired tens of thousands of mortar bombs and artillery shells into the Acropolis, caused only superficial injury to the Parthenon? How could it have happened, as one surprised visitor wondered, that all the monuments of Athens were ‘defying the crumbling sand of time, or the more destructive hands of the barbarians’.1 Or, as an immigrant who intended to settle posed the question, why, despite six years of war followed by six years of Ottoman military occupation, had there been no damage to the Parthenon since Elgin’s day?2 It is easy to understand why observers turned to the language of miracles, providentialism, or destiny. At the time, no other explanation could be imagined. And even the real explanation might have seemed almost as hard to believe.

It was while Reschid’s army was already on the march from Missolonghi towards Athens in the spring of 1826 that Stratford Canning received a copy of an intercepted letter, in which Reschid told his government that he intended to obtain experienced mine-workers from Albania and destroy the ancient monuments on the Acropolis by ‘overturning the whole mountain’. The exact status of the letter is not clear, but there is no reason to doubt that, as a report of what Reschid intended, it was true.3 And, in terms of Ottoman aims, the policy described in the letter is understandable, rational, and even predictable. If, at the beginning of the Revolution, the Ottoman authorities had been puzzled by the reappearance of the ancient Greeks and their stories, by 1826 that was no longer the case. On the contrary, since 1821, there had been scarcely a book, a pamphlet, a picture, or a conversation with westerners from which the ancients were absent. To the Ottoman leadership, the Acropolis of Athens was a prime candidate for heritage cleansing, offering the opportunity for a more contemporary, and perhaps more effective, display and performance of Ottoman power than the destruction of yet more churches, the desecration of yet more Christian graveyards, sending yet more bags of ears to Constantinople, or building yet more pyramids of skulls. If the Greek Revolutionaries were asserting a neo-Hellenic nationalism, what better way to combat that idea than by destroying what was, by far, the most visible reminder of ancient Hellenism in all the revolted provinces?

It was after reading the intercepted letter that Canning decided to make a direct appeal to Reschid. More than most, he understood that the Greek Revolution was a clash of ideologies and traditions, and that the standard western political rhetorics (‘oriental barbarism’; ‘national liberation’; ‘atrocities on both sides’) were inadequate as explanations, let alone as guides to policy. Nor could the war be understood solely in tactical or strategic military terms without giving weight to the need of both sides, but especially the Ottoman, to perform for multiple audiences, including the foreign powers and their publics.

Although in his dealings with foreign governments he did more than his share of urging, Canning seldom scolded. And he was scrupulous in adhering to the external niceties and formalities, including paying compliments, that enabled representatives of countries with widely different views and traditions to separate their personal from their official selves, and so to maintain professional relationships. Unlike most of the opinion formers and policy makers in Constantinople and in the European capitals, Canning not only had shelves of reports by eyewitnesses piling up in the embassy, enabling him to be among the best informed of all the principal actors, but he had seen for himself the effects of what he was to call ‘the antipathies of ‘race and creed’.4

And he was about to see more. On 1 December 1826, when Reschid’s army was already in Athens besieging the Acropolis, the ship in which Canning was travelling put in to the small island of Psara, whose insurgency had been forcibly put down. The port town was empty and in ruins, and along the coast he saw the bodies of those who had thrown themselves from the cliffs, including women who had first killed their children. When his party ventured inland they met two survivors whom he described as ‘worn nearly to skeletons by fear and anguish and famine, the very types of hopeless misery, with haggard eyes and loathsome beards and tattered rags by way of clothing, they told without language the history of their sufferings’.5 On his arrival at the British Embassy, Canning may have read the Yafta dated 14 July 1824 that declared that it was a sacred duty, with the help of Allah, to punish the rebels. The island had been purified, and a booty of ten captains, five hundred prisoners, ten ships, and a hundred pieces of cannon divided among the Muslims. The heads of the five hundred prisoners had been displayed along with around twelve hundred ears.6 It was about the same time that Robert Walsh, the British Embassy chaplain, on his way back to England by land, met a party of Ottoman soldiers who had taken part in the destruction, with large baskets strapped on the sides of their horses containing boys and girls aged from three or four to nine or ten, on their way to be sold in the slave market at Constantinople.7

Canning’s letter to Reschid, which he sent in his official capacity after hearing of Reschid’s intention to destroy the Parthenon, made no criticism of Ottoman codes and customs.8 On the contrary, he congratulated Reschid on his military success at Missolonghi, in effect publicly accepting that, under both European and Ottoman norms, suppressing rebellion was an internal matter. Instead, as has been noted by Professor Eldem, who discovered documents from the Ottoman side of the correspondence in the archives in Istanbul, the letter goes on to offer a ‘rhetoric of anticipated satisfaction’.9 Canning writes as if ‘European’ attitudes were already shared by the Ottoman leadership, and that he and Reschid shared the condescending, almost contemptuous, attitude that, in private at least, European elites took towards the rank and file of their armies. By making a remark in a letter that he could not have said in a public forum, Canning’s language tried to co-opt Reschid into a shared intimacy, inviting him to join an imagined community of men who know what power is and how the world actually works. The Ottoman Government is certain to have known that, when the Concert of Europe was established at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Britain and Austria had wanted to include the Ottoman Empire but had been unable to persuade the other powers.10 They knew that Canning had spent much of 1825 and 1826 rumbling across Europe’s bad roads in a carriage, visiting the courts of Europe in order to discuss the future of Greece with their highest officials, including the emperors of Austria and Russia and the kings of Prussia and of the Two Sicilies.11 Canning’s letter was a scarcely disguised offer to revisit the 1815 decision, with the prospects for the future that such a change in relationship would offer.

By invoking the ‘beauty’ of the ancient monuments, Canning sought to move the negotiation away from the political (‘though of small importance in the eye of Reason or of Religion, and wholly unconnected with affairs of State’), and from the age-old Muslim discourses of idolatry (‘viewed by Turks even of the higher class with contempt or at best with indifference’). While acknowledging, with a touch of disdain, the emerging new status of the monuments as neo-Hellenic symbols sustaining a nationalist rebellion (‘under a fixed persuasion that those enduring records of the former glory of that Country contribute in a great degree to render the present generation of Greeks discontented with the Turkish Government’), he urged Reschid to think of the longer-term political interests of the Ottoman Empire.12

Canning’s letter implied that the decision of whether or not to destroy the ancient monuments was one to be taken by Reschid as military commander. He did not suggest that Reschid was bound by the 1821 vizieral letter (firman), but as part of his letter he sent him a copy, a document that Reschid may not previously have known about.13 And we know from Canning’s letter to London that he also told the Ottoman Government of his request to Reschid, so opening up the thought that if someone at court wanted, in modern terms, to throw the book at him, Reschid’s plan might be regarded as disobeying a vizieral order made in 1821 that had been implemented in that year and never been countermanded or withdrawn.14

Canning entrusted the responsibility for delivering his letter to Captain Hamilton, the commander of the British naval squadron in the region, guaranteeing the funds to employ messengers so that Reschid would receive the letter before his army reached Athens.15 And, almost simultaneously, before he had received Reschid’s answer, Canning had been able to demonstrate the practical value of his goodwill. On 8 July 1826, with funds advanced by Canning, Captain Hamilton redeemed and took on board his ship twenty-five named Ottoman individuals whom the Greeks of Athens had held captive. Some may have been among the prisoners whom Edward Blaquiere saw on the Acropolis on 24 July 1824 then employed making cannon balls from the marble.16 According to Colonel Stanhope, whose access to international funds gave him influence, it was he who, a few months before, had suggested the idea to Odysseus, a claim there is no reason to doubt. Turning the mosque within the Parthenon, hitherto used as a granary, into a museum of antiquities displayed the romantic philhellenism that linked the moderns to the ancients. Using Muslims to do the work was a performance of the transformation of free Greece into a modern European state that did not put captured enemies to death.17

On the list of persons who were offered as part ransom in exchange for not destroying the Parthenon, some are noted as having been captured at various localities including Cyprus and from vessels at sea, but the three named imams who are noted as ‘captured in Athens’ and who appear to have been accompanied by ‘1 woman and 2 children’ may have been survivors of the massacres of 1822.18 The total price is not recorded, but when one individual is reported as having cost three hundred Spanish dollars, we can estimate a total of several hundred pounds sterling equivalent. Since, as Canning had recognized, his chances of reclaiming the money from the Ottoman Government were not high, Canning’s action was humanitarian, but it can also be regarded as an upfront payment.

Canning appreciated that, as part of Reschid’s ambition that the Ottoman Empire should be accepted as a reliable and European-style partner. He therefore could not be bribed with money. And, if so, he was right. When the French Admiral de Rigny, who was also involved in separate negotiations, offered money directly, his offer was refused with contempt (‘The ruler of the world has no need of money’), a fact only known at present from the Ottoman records.19

At the time Canning wrote his letter to Reschid, it seemed inevitable that the monuments of Athens could not survive the forthcoming attack. If they were not destroyed by the artillery of attacking Ottomans, they would be destroyed by the gunpowder charges of the defending Greeks as they immolated themselves. And it was against this contingency that Canning invited Captain Hamilton, on his way to Athens to deal with the ransoming of the Muslims, to use the same channel to sound out the possibility of making another offer to Reschid.20 If Reschid insisted on destroying the monuments, Canning indicated, he would be in the market to buy some of the pieces either in advance or after the buildings had been knocked down. Canning knew that, if he were to buy pieces of the monuments, he risked being classed with Elgin (‘the danger of being despised with the Goths and the Elgins of other times would not deter me from offering to become a purchaser of the Caryatides and of the reliefs which still remain on the Parthenon’ [so underlined]), although, if the circumstances had arisen, that would have been unfair. If Canning’s letter to Captain Hamilton made any difference to Ottoman policy, no record has yet been found.

In the event, the fall-back was not needed. Reschid and the Ottoman Government evidently understood that a bargain was being offered, one that Canning did not need to spell out in writing in his initial letter, but that he was to do soon afterwards when a wider bargain came to be discussed.21 By including a range of face-saving devices, Canning enabled Reschid, who had received instructions from his government, to send a reply to Canning in which, without admitting that he had changed his mind or that he had been overruled, he promised to do his best to save the monuments from being destroyed in the battle for Athens that could not be long delayed22

In telling London about the intercepted letter and the Ottoman army plan to ‘overturn the mountain’, Canning, who had never visited the Acropolis, had wondered whether such a plan was feasible.23 He, unlike Reschid, may not have known that the Acropolis is permeated with caves, some very deep, and that explosives set off within the caves could cause such vibrations that the walls would be liable to crumble as in an earthquake. In particular, for any military commander intent on destroying the Parthenon, the Panaghia Speliotissa under the monument of Thrassylos would have been a perfect place to start. The deepest of the Acropolis caves are on the south slope. The monument that was built above the entrance, which was then being restored to its ancient appearance, is shown as Figure 17.1.

Figure 17.1. The Monument of Thrassylos under restoration 2013.24

As it stood during the Revolution, the Cave, situated high on the open slopes but outside the walled and fortified Serpenji, was potentially a strongpoint both for defenders and attackers. With its bricked up entrance, slit-holes for muskets, and plentiful storage room behind, it was an advance post from which a large area of the approaches to the Acropolis rock could be commanded.25 Indeed, the fact that the Ottoman authorities chose to close the ancient church a few years before the outbreak of the Revolution, and oblige the Christians to relocate to another cave church set into another hill, may indicate that they were aware that the pre-Revolutionary sentiment in Athens was more than a literary movement.26 That it would be possible to bring down the walls of the Acropolis by putting explosives in this cave was not a secret, being noted even in the printed compilation from local reports by published by Guillet in 1675.27

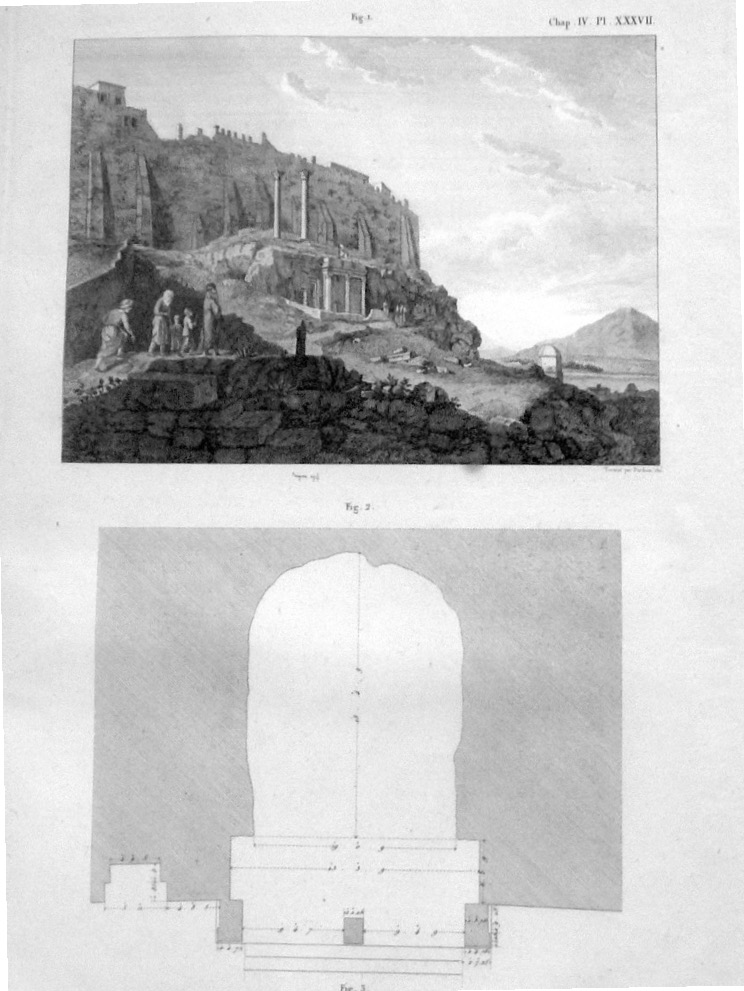

Figure 17.2. ‘The Choragic Monument of Thrassylus etc’. Copper engraving.28

The Cave had been artificially enlarged at some unknown time so that stretched deep into the Acropolis rock.29 Until shortly before the Revolution, as a Christian site, it appears to have been second in importance only to the Christianized Theseion. When the young architect Charles Robert Cockerell fell ill in Athens in 1810, his recovery was attributed to the power of the ‘Panagia Castriotissa.’ ‘Our Lady of the Castle’, with whose cult the Cave was associated.30 As can be seen from the image shown as Figure 17.5, it lay outside the walls of the Serpenji, and could be approached directly by any hostile force that had breached the town walls.

The Cave appears to have been continuously in use back to the remotest antiquity. The picture, reproduced as Figure 17.3, made in 1805 before the Revolution, is one of the few that are known of the inside of any of the Acropolis caves when they were in active use as holy places.

Figure 17.3. ‘Athens, Panaghia Speliotissa’ [‘All-holy lady of the Cave’]. Copper engraving of an image composed on the spot in 1805.31

The Cave was so brightly painted and gilded with Christian images inside that it was known as the Chryssospeliotissa, the ‘golden cave’.32 The three Caves are shown, along with the Theatre of Dionysos, but not the Thrassylos monument or the two columns that were erected later, which can be seen on a Roman imperial low-denomination bronze coin of the first century CE or later—one of only two visual presentations of the Acropolis that survive from the ancient world, and the last to be made locally until 1835, a millennium and a half later.33 At least two variations have been found, both from an implied bird’s-eye or god’s-eye viewing station, and each with artistic features that select what is recommended as important to the implied viewer. Since photographs of coins are hard to read, even if they are easy to find, I show instead an engraving from what was then a unique example in Figure 17.4.

Figure 17.4. The Theatre and Caves on the Acropolis south slope. Engraving of a low denomination Roman imperial copper coin.34

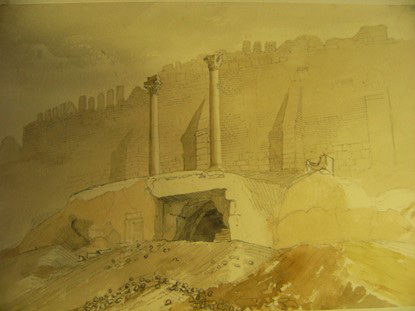

In the event, when the Greek forces retreated into the Acropolis on 3 August 1826 and Makriyannis, with others, attempted to use the Cave for military purposes, it proved to be of little value. Since it lay within range of the Ottoman artillery batteries on both Philopappos and Lycabettos, it was targeted and most of the defenders were killed or wounded.35 Later the Ottomans appear to have brought up a piece of ordnance and fired it directly into the mouth of the Cave.36 It was sketched on the spot by James Hore in 1835 in its immediate postwar state soon after the Ottoman army left, as shown in Figure 17.5.

Figure 17.5. The Cave and remains of the Thrassylos monument, 1835. Pen and wash drawing by James Hore.37

How far what was left of the Thrassylos monument after Elgin’s removals was further damaged in the years before the Greek Revolution cannot be easily established, but the two ancient columns remained undisturbed, and there was no attempt to bring down the Acropolis walls by destroying the buttresses. Reschid, in promising Canning that he would do his best to preserve the monuments during the military operations to retake Athens, had left himself a way out: ‘in the present war carried on against obstinate and frantic Rebels, they may take refuge in some of the aforesaid Monuments and there fortify themselves; in which case I shall be under the necessity of employing violence against them, but even in this case I will endeavour to preserve the aforesaid Monuments’.38 With the Monument to Thrassylos, Reschid had carried out his promise to Canning to the letter.

So here we have one answer to the question posed in the title of this book. The reason why the Parthenon and the other ancient monuments of Athens were not damaged during the Greek Revolution, we can confidently conclude, is that the Ottoman army ensured that they were not. The Parthenon was saved by carefully targeted and well-executed shooting, carried out in accordance with explicit orders from the Ottoman military high command, acting under instructions from the sultan, to kill and terrorize those whom they regarded as rebels and infidels while causing minimum damage to the monuments. Nor is this my personal judgement with hindsight prompted by the revelations in the documents, nor is it the result of building a Venn diagram that shows the overlap of the different sets of evidence, documentary, visual, and material/archaeological, although both of these approaches would lead to the same conclusion. It was the professional military judgement of Adolphus Slade, a senior British naval officer, later an admiral in the Ottoman navy, who travelled extensively in the Ottoman Empire tasked with observing the capabilities of its armed forces. Knowing nothing of the firmans, nor of what had gone on behind the scenes, nor of the bargain made by Canning with Reschid, Slade volunteered the opinion from what he saw in Athens in the spring of 1834, that the Ottoman army had not only directed their artillery with skill, but had done better than a European army would have done. As he wrote: ‘It must have required great care to preserve its ruins, more than would be shewn in modern civilized warfare’.39

1 Torrey, F.P., Journal of the cruise of the United States ship Ohio, Commodore Isaac Hull, commander, in the Mediterranean, in the years 1839, ‘40, ‘41 (Boston: Printed by S.N. Dickinson, 1841), 33.

2 ‘Notwithstanding the events of 1827, the monuments of Athens were left much in the same condition to which they had been reduced by the pillagings of the notorious Elgin’. Perdicaris, G.A., The Greece of the Greeks (Boston: Paine and Burgess, 1845), 39.

3 Transcribed from a translation in Appendix C. In the correspondence we have, Reschid never denied or disowned it.

4 Lane-Poole, Canning, i, 389, from Canning’s manuscript memoirs to which he had access but have not subsequently been found.

5 Lane-Poole, Canning, i, 398–90 from Canning’s manuscript memoirs.

6 Reported by Ambassador Strangford in Kew 78/123.

7 Walsh, Rev. R., LL.D, M.R.I.A., Narrative of a journey from Constantinople to England (London: Westley, second edition, 1828), 126. The case of a boy taken from Chios who remembered the baskets was noted in Chapter 14.

8 Full text of the English version in Appendix D. This letter and some internal Ottoman documents on the considerations that caused the Ottoman Government to agree to the request, found in the Ottoman archives, were also discussed by Professor Edhem Eldem at the conference ‘The Topography of Ottoman Athens’ held in Athens on 23–24 April 2015. Videocast at http://www.ascsa.edu.gr/index.php/News/newsDetails/videocast-the-topography-of-ottoman-athens.-archaeology-travel-symposium

9 In Appendix C, I include a summary of discussions on the Ottoman side, that were published by Professor Eldem from official Ottoman Government documents.

10 Noted by Siemann, Wolfram, Daniel Steuer (translator), Metternich (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard UP, 2019), 628.

11 Lane-Poole, Canning, i, 314–516, mainly from Canning’s own reminiscences and non-diplomatic correspondence.

12 Canning to Foreign Secretary, 6 June 1826, full transcription in Appendix D.

13 For the 1821 firman see Appendix C.

14 The documents from Ottoman archives discovered by H. Sükrü Ilicak are summarized in Appendix C.

15 Correspondence in Kew FO 352/15A/3.

16 ‘Near the door of this miserable edifice [the mosque in the Parthenon], I found a party of Turkish prisoners hewing shot out of the fragments of pentelic marble and granite columns that were strewed about in such abundance’. Blaquiere, Second Visit, 95.

17 Stanhope, the Honourable Colonel Leicester, Greece, in 1823 and 1824: being a series of letters and other documents on the Greek revolution, written during a visit to that country. A New Edition containing numerous supplementary papers, illustrative of the State of Greece in 1825, Illustrated with several curious fac-similes, to which are added Reminiscences of Lord Byron (London: Printed for Sherwood, Gilbert, and Piper, 1825), 130, 136.

18 ‘List of Turkish prisoners delivered by the Governor of Athens to Captain Hamilton CB of His Majesty’s Ship Cambrian 8th July 1826.’ Kew FO 352/15A/3, 450.

19 Reschid to the Ottoman Government, 23 August 1826 in Appendix D.

20 Full text in Appendix D.

21 Discussed in Chapter 18.

22 Transcribed in Appendix D.

23 ‘notwithstanding some difficulties in its execution’. From Stratford Canning’s letter to the Foreign Secretary, 30 September 1826, transcribed in Appendix C.

24 Author’s photograph. The conservation was completed in January 2018.

25 An account of how the Cave appeared from a distance by Lord Bute is quoted in The Classical Parthenon, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0279.

26 ‘About 1818 the cave became a stronghold, and the greater part of the buildings of the church were then demolished; the altar, however, according to Pittaces [Pittakis], was taken to the subterranean church of St. Marina, near the Observatory, probably from an idea of keeping it still in a cave. Thither the devotion has followed it’. Bute, Essays, 122.

27 ‘ ... it was admired by some of us (more verst in Warlike Affairs than the rest) that the Christian Corsaires, among their many Designs and Enterprizes upon the Turks, never thought of making use of that hole as of a Mine half made to their hands for blowing up the Castle, which in their judgment ten or twelve Barrels of Powder would easily and effectually have done’ ... ‘and for the Castle, he would have taken that by the hole I mentioned before; to effect this, the Candiot desired only eight hundred Men, and three or four Field-Pieces (more for terrour than execution) with ten barrels of Powder for springing the Mine.’ Guillet in English, An Account of a late Voyage to Athens, containing the estate both ancient and modern of that famous City, and of the present Empire of the Turks: the Life of the now Sultan Mahomet the IV. With the Ministry of the Grand Vizier, Coprogli Achmet Pacha. Also the most remarkable passages in the Turkish Camp at the Siege of Candia. And divers other particularities, etc. By Monsieur de la Guillatiere [sic] ... Now Englished (London: Printed for J[ohn] M[acock], Herringman, 1676), 172. The story by Guillet was reported by Clarke, Travels, part the second, section the second, 1814, 481, a book of which a copy was probably available in Athens in the Philomuse Society collection of books, but after hundreds of years of military occupation, they probably did not need a westerner to tell them.

28 Stuart and Revett, new edition, The Antiquities of Athens. Measured and delineated by James Stuart FRS and FSA and Nichols Revett, painters and architects. A New edition (London: Priestley and Weale, 4 volumes, 1825), ii, opposite 90.

29 ‘natural formation enlarged by art’. Stuart and Revett, The Antiquities of Athens, ii, 86.

30 Noted by Hughes, Thomas Smart, Travels in Sicily, Greece and Albania (London: Mawman, 1820), i, 252. Garnered from drips inside, the water may have occasionally produced beneficial placebo effects, but if consumed in other than small quantities, it would have gradually have acted as a poison. I was told a few years ago that holy water from the Cave was still on sale in Athens if you knew where to ask.

31 S. Pomardi del., Engraved by Chas Heath, published June 1, 1819, by Rodwell & Martin, New Bond Street, in Dodwell, Classical Tour, i, facing 300. A full description of the interior of the church as it was reclaimed for Christian use after the damage done during the Revolution is given by Bute, Essays, 121–25.

32 So called by, for example, Makriyannis, Memoirs, ed. H.A. Lidderdale, 100.

33 Discussed, with an explanation of why the making of images ceased in Chapter 14.

34 Stuart and Revett, The Antiquities of Athens, ii, 86. Frequently photographed, for example, in Kraay, C.M., The Coins of Ancient Athens (Newcastle: Minerva Numismatic Handbooks, 1968), Plate VIII, 12.

35 Makriyannis, 100.

36 Fauvel, Clairmont, 95.

37 Private collection. Rights reserved.

38 From Reschid’s letter to Canning, received c. 25 September 1826, transcribed in full in Appendix D.

39 Slade, Adolphus, Records of Travels in Turkey, Greece, &c: and of a cruise in the Black Sea, with the capitan pasha, in the years 1829, 1830, and 1831 (London: Saunders and Otley, 1833), ii, 228. In the same passage he noted that ‘the Osmanleys are not such indiscriminate destroyers [of ancient buildings] as is usually believed’. His visit to Athens is dateable from a work published later, Slade, Adolphus, Turkey, Greece And Malta (London: Sauders and Otley, 1837), 253.