1. Planning the project

© Andrew Pearson, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0138.01

While perhaps not the most glamorous aspects of a project, its scope, budget and practical planning are critical. All these matters need to be considered at the very outset and the following sections consider the ways that, through detailed advance planning, it is possible to create the circumstances for a successful project.

- Establish the scope of the project. While it is important to have a clear sense of the overall objectives, it is also critical that there be a precise understanding of the detail. In other words, it is not enough to aspire to digitise a particular collection: you must also be able to quantify the size of the task.

- Do your research. Try to learn as much as possible about the collection you wish to digitise, as well as the local circumstances in which you will be working. Although there will doubtless be unknown factors and undecided detail, the better informed you are, the more likely it is that your approach will be appropriate to the task.

- Build partnerships in the host country. Having local links will be invaluable throughout the project, providing — amongst other things — a source of knowledge, a conduit for communication, and immediate help when practical problems emerge. Local interest in what you are doing will also make the whole experience more enjoyable and rewarding.

- Manage your own and others’ expectations. Be realistic about what you think you can achieve within the scope and budget of your project. In the first instance, this is necessary to convince grant-awarding bodies that yours is a viable project: applications that are over-ambitious or under-costed may be perceived as naïve and are likely to be rejected. In the mid-term, it is you who will be responsible for delivering the project on time and within budget. Avoid setting yourself a stressful, unachievable task. Finally, at the close of the project, it is important that you deliver what is promised. The funding body has awarded money on the basis of your scope and will expect you to meet it. In short, do not promise what you cannot achieve. It is better to offer less but deliver more, rather than the other way around.

- Think also about outcomes. Local partners may have their own expectations of what you will do for them. Meeting these expectations is critical, not only for your own professional standards, but in case future funding is going to be sought or long-term local partnerships developed.

- There are also specific issues to be thought through when considering the project’s conclusion. For example, who will have access to the data? Ideally, how will you ensure it is widely accessible, and sufficiently well-publicised for people to know it exists? What hardware might be needed in order for access to be possible or practical? How many hard drives will you be distributing locally, and to which institutions? Do you need an agreement to migrate data to a local government server?

- Seek advice. While this book provides guidance, it can be neither comprehensive nor project-specific. There is no substitute for conversations with people who have undertaken projects of a similar scope, and with those either living in, or with experience of, the place where you will work.

- Obtain permission. This is absolutely critical, as all efforts will be wasted if agreement is not obtained locally for permission to access the materials, digitise them and disseminate the product. Ensure that this permission is formally set down, in a letter or email, by a person with the authority to give it. Make sure that person fully understands what they are agreeing, to avoid the risk of permission being rescinded at a later stage. (For further discussion of permissions and open access see page 150.)

Endangered Archives Programme grants

The Endangered Archives Programme offers two types of grant: a Pilot project or a Major award. The first type allows for a preliminary investigation or audit of archival collections on a particular subject, in a discrete region, or in a specific format. Pilot projects are also an opportunity to determine the feasibility of digitisation, and in many cases involve the trialling of photography or scanning. They are also a means of judging the technical competence of the grant holder, the likelihood of them succeeding with a full-scale project, and whether external specialists might need to be added to the team.

Some archival collections are sufficiently small to be captured within a Pilot project. Major grants are generally larger and the projects more protracted. Depending on circumstances, some follow immediately from the pilot phase, while others have resumed after an interval of several years.

Grant awards for both Pilot and Major projects are made annually and are assessed by an International Advisory Panel. The Panel often likes to see initial applications for a Pilot project before progressing to a Major grant.

Figure 4. EAP329, A peripatetic project digitising Acehnese manuscripts in rudimentary circumstances, Indonesia. Photo © Fakhriati Thahir, CC BY 4.0.

Once I had identified a funding agency, I requested the support of my advisor to co-direct the projects with me and sought the advice of others who had carried out digitisation projects. By consulting sample grant applications, I was able to create a realistic list of equipment […] Writing the final grant application cannot be done at the last minute or overnight. It is important to start planning these projects about a year before you plan to begin digitisation.

Courtney Campbell, EAP627 and EAP853, Brazil

I had no experience of digitising records, but I did know the island and its historical resources. Either get some training in digitisation to archival standard, or team up with an experienced person from the start.

David Small, EAP093 and EAP794, Nevis

I would recommend that anyone intending to undertake an EAP project reads other final reports, especially in the region of the world they are working, and talk with former grant recipients. This saved me a lot of time and meant a successful process for digitisation that had worked in Anguilla could be modified to work in Montserrat.

Nigel Sadler, EAP769, Montserrat

Our formal point of liaison was with the national government, but when trying to set up the project its officials were often woefully slow to communicate. Fortunately, we were also in contact with the director of the heritage society who, when progress came to a halt, would visit the relevant officials and cajole them into taking action!

Project budgets can broadly be divided into two basic headings: salaries, and non-salary costs. The first of these comprises the wages of those being paid directly by the project, as well as replacement costs for staff who are being seconded to the project. Non-salary costs incorporate all other elements of the budget, from purchases of equipment and supplies to travel, accommodation, subsistence and items such as freight shipping, and personal and equipment insurance.

Equipment specifications are discussed in the following section, while most other non-salary costs will be specific to an individual project. This section therefore focuses on how the human inputs of a digitisation exercise can be quantified. In most mid- to larger-sized projects that address significant volumes of material, staff costs will be the dominant part of the budget.

Choosing your equipment

Appropriate equipment for digitisation is discussed separately within this book. However, every project is different and there is no ‘one size fits all’ solution. When specifying equipment, therefore, consider the following:

- Subject. What means of digitisation is most appropriate to your documents? Should you be purchasing a camera, scanner, or a combination of these items?

- Location. Where will the digitisation take place? Will you be working in multiple places, requiring you to have a compact, portable set of equipment? Alternatively, will you be based in a single location where you could set up a basic studio? In the latter case, you could consider less portable items, such as a copy stand and studio lamps, as well as desktop computers and a larger monitor, instead of a laptop.

- Compatibility. Do your purchases need to integrate with, or complement, existing equipment? For example, does your local partner already own a particular brand of camera and lenses? Simple issues also require thought: for example, whether the plugs on your electrical leads are compatible with the local supply. If you are working with a local government, it is also possible that its IT department will only maintain or support computers from certain manufacturers.

- Legacy. The end-use of your equipment is also a factor if it is to be donated locally at the end of the project. (N.B. This is a stipulation of all EAP grants.) Consider what would be most useful: for example, would the library or archive benefit from owning a copy stand? Equally, consider if certain items might simply be consigned to a cupboard and never used. Taking the same example, an expensive tripod — though useful to your project — is probably not an appropriate item for long-term public use in a reading room. The question of compatibility is also relevant.

As the preceding points illustrate, subject, location and various other factors will influence the choice of equipment for a digitisation project. However, for any project there are absolute essentials, while for a less minimalistic project there are additional items that can potentially improve the product, speed up productivity, or both.

We also had the challenge of photographing large leaves of books that did not fit into a scanner, and which would not fit into the image frame of the camera, even at the tallest setting of the copy stand (which was the biggest available to buy). Instead, we devised a way of putting the texts on a wooden board, placed parallel to the camera on a tripod.

Karma Phuntsho, EAP039, Bhutan

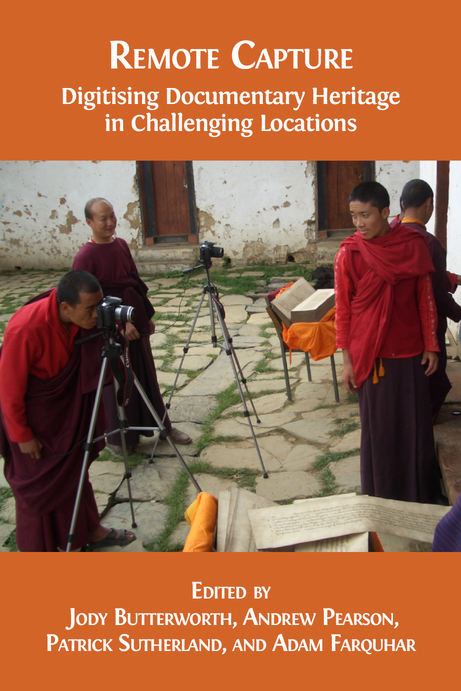

Figure 5. EAP039, Photographing Buddhist manuscripts in Bhutan. These manuscripts were too large to be photographed beneath a tripod or camera stand, so instead were attached to a board, allowing them to be photographed from a greater distance. (N.B. The securing pins were immediately above and below the manuscripts, rather than pierced through them.) Photo © Karma Phuntsho, CC BY 4.0.

Consider local travel and the time it takes — will getting from your accommodation to the institution eat into the working day? Is it feasible to use local public transport or will you need to arrange cars and drivers?

If running an itinerant project, plan your travel itinerary carefully with a view to efficiency. Make sure that you do not have to retrace your steps. Equally, factor in some flexibility to your time and budget, in case your plans have to change.

Quantifying the collection

The time and labour required to undertake a project will principally depend on the size of the collection and the rate at which material of this type can be digitised. The more precisely these factors can be quantified, the more confidence can be placed in the resultant cost estimates and timescale.

There are various ways that the size of a collection may be quantified, depending on the extent (if any) of access to the collection during the planning stage.1

- Individual page count. This enables the most precise quantification but is only feasible for relatively small collections, or for document groups where the pages of each volume are numbered. It is clearly not practical to count the unnumbered pages of every book in a large collection.

- Sample page count/number of volumes. This is a reduced page-counting exercise, in which a sample of representative material is quantified, and the result extrapolated to the collection as a whole (i.e. number of pages per ‘average’ volume, multiplied by the total number of volumes).

- Sample page count/shelf width. In this method, page counts are made for a sample of the collection — again, these being representative examples of the whole. The width of each volume is also measured, allowing for a calculation of pages per millimetre. Total shelf length is then measured. The two figures can then be multiplied to estimate the total number of pages.

For the two latter methods, it is self-evident that the larger the sample, the greater the precision of the overall estimate. Both produce only approximate results and, as Table 1 shows, applying the two methods to the same collection produces different figures — in this case varying by 5%. The higher figure needs to be taken forward for the calculation of time inputs and data storage requirements.

Of course, if you have very little information about a collection, your ‘estimate’ will be little more than a guess. This is an understandable scenario, given that you may be dealing with a collection to which you do not yet have access, or are contemplating a project where the material is scattered across numerous locations — perhaps held by multiple private individuals. In such instances, the only recourse is to estimate the time requirements very conservatively — or, in fact, consider whether the first stage of your project is simply dedicated to reconnaissance and quantification.

In quantifying the collection, it also becomes possible to reach precise figures for the amount of data that will be generated. This, in turn, informs you about the volume of digital storage that will be needed — once again feeding back into your equipment list and budget calculations. Table 2 (see p. 33), based on a real-world example, shows both of these steps. In this instance, the size of the collection was well understood, a pilot project having allowed for most of the books to be individually page-counted.

Table 1. Example quantifications, estimated by page counting and shelf length. Example taken from EAP524 St Helena. Sample method: the volumes were taken from all shelves. The choice of volumes from a given shelf was essentially random, though if different types of binding or styles of book were present an attempt was made to take a representative sample.

|

Sample size Number of volumes page-counted = 104 Total number of volumes in the collection = 1007 Percentage of volumes page-counted = 10.3% |

|

Estimate by page count per volume Average number of pages per volume = 305 (based on 104 volumes, comprising a total of 31688 pages) Total number of pages = 305 pages x 1007 volumes = 307,135 pages |

|

Estimate by page count per mm Average thickness per volume = 47mm (based on 104 volumes, occupying 4847mm of shelf width) Average no. pages per mm = 6.54 (based on 31688 pages occupying 4847mm of shelf width) Total shelf width = 44,800mm Total number of pages = 44,800mm of shelf x 6.54 pages/mm = 292,992 pages |

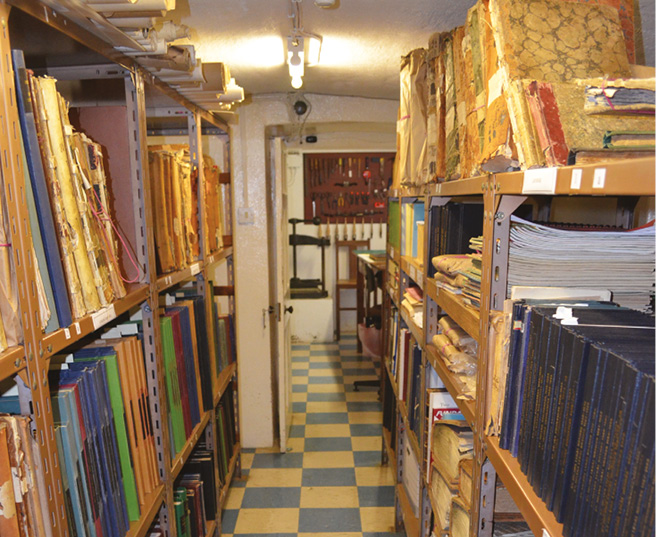

Figure 6. EAP524, The St Helena Government Archives, Jamestown. EAP524 centred on a survey of this collection, including the quantification exercise shown in Table 1. Photo © Andrew Pearson, CC BY 4.0.

It would have been helpful to know in advance just how much data the project would produce. With hindsight we would have put more money into the budget for portable hard drives if we had realised the size of the data required, and for the time required to convert the RAW files to TIFF.

Stephen Morey and Poppy Gogoi, EAP373, Assam

Factor in enough time for cataloguing the collection [i.e. Listing], because it might be very difficult and time-consuming to decide the names and contents, especially when those materials are in an endangered language.

Jian Xu, EAP012, EAP081, EAP143, EAP217, EAP460 and EAP550, China

Timescale and labour requirements

Having established the size of the task, the second step is to calculate the rate of digitisation. If you do not have prior experience of digitisation, seek the advice of others — ideally those who have worked with similar materials. Alternatively, if you have the luxury of a two-stage project, the initial phase can be used to trial the equipment and establish a realistic work rate, using the actual collection.

When making an estimate, it is useful to break the calculation down into small increments. In other words, start by thinking about how long it will take to lay out and photograph a single page, and then factor up from there. This is likely to be more realistic than basing your estimate on broader and possibly rather vague assumptions: for example, ‘it should be possible to digitise one volume per day’.

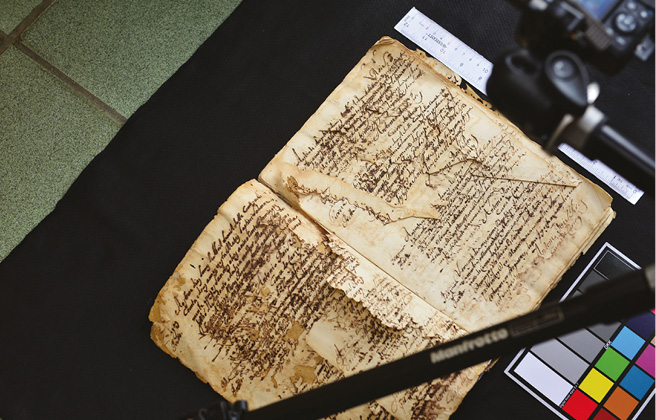

Figure 7. EAP627, A fragile manuscript from Paraíba, Brazil. Consider how the physical condition of your documents might affect the speed of your digitisation. Photo © Courtney Campbell, CC BY 4.0.

Finally, before arriving at your definitive estimate for time inputs, consider how theory will meet practice in the real world. For example:

- Slow beginnings. At the outset of a project, despite your own enthusiasm, events may (and probably will) progress slowly. It takes time to get set up, as you hold meetings with the relevant people in authority, finalise your permissions for access and copying, and cross the myriad minor hurdles which inevitably attend a new enterprise. It is not unusual to lose days or even a few weeks at the outset, particularly if you are working in a place with a complex local bureaucracy. Factor this extra time into your budget.

- Non-productive time will persist throughout the project. Remember that the slick, efficient workflow you envisage at the planning stage is unlikely to manifest itself in the real world. Consider, for example, how much time will be needed to move documents from their place of storage to where they will be digitised and back again. Alternatively, you may have to travel between venues to carry out on-site digitisation. Other crucial activities also take time, such as the backing up of data. Productivity also has the potential to fall because of IT problems or equipment failure.

- Document sizes and condition. The physical size and condition of a document may well influence the time it will take to lay out and digitise. Large format items may be more difficult to lay out, while the necessary delicate handling of damaged or brittle materials will be slower than for robust items in good condition.

- Productivity. Your own work rate may not be an accurate reflection of your staff work rate. During project planning you may have trialled the digitisation process yourself, or simply have a sense of how quickly it should proceed. Be cautious, however. While you might keep up a certain pace for a few days or weeks, ask whether this is sustainable for a staff member over the long term. Additionally, if you are delivering a project in an area with different cultural expectations, you may find that attitudes to work may be more relaxed than your own — perhaps markedly so.

- Size of workforce. Two staff members may be better than one… but not necessarily as productive. Digitisation is a precise, demanding, but repetitive exercise. A single staff member, working in isolation over a long period, has the potential to become disillusioned and demotivated. Having two or more staff tends to head off this problem, and also has the benefit that they can cross-check each other’s work. Arguably, this leads to a higher-quality product. On the other hand, two members of staff, working side-by-side with a single camera, will not be digitising at twice the rate of a single person. Consider this possibility in your ‘person-day’ calculations.

- Don’t underestimate your own inputs. As project manager, the amount of time you will need at the beginning of a project is deceptively large, with tasks ranging from local liaison to travel bookings and the ordering, testing and shipping of equipment. The same is true of the tasks at the end, such as report-writing and the archiving of data. In between, keeping the project running smoothly can often consume much more time than you ever expected, particularly if problems arise that require you to solve them.

The final part of Table 2 shows how the figures for page count and work rate combine to produce an estimate of the total number of person-days for the entire project. The calculations produce an exact figure but, as discussed above, this has to be treated as an unrealistic minimum. The last rows of the table therefore depart from the calculations to offer a more subjective, but ultimately more realistic, ‘real-world’ figure. In this case, there was good reason to downgrade the work rate very considerably. The documents in question were held in a different building to the place where digitisation was carried out, a situation that added considerable time to proceedings. Moreover, the local staff were also delegated the tasks of exporting their original RAW images to TIFF format, as well as being responsible for data backup and cataloguing. For all of these reasons, their real-world progress would necessarily be much slower than the theoretical rate — in this case roughly half. And, although not shown on the table, additional time was added to the budget because two staff members were working with a single camera set-up: as noted in the bullet-points above, this creates a good work environment but, in terms of person-days, one that is less productive in absolute terms.

Finally, be philosophical! Accept that difficulties and delays will be an integral part of your project. Be patient, addressing problems in as relaxed a way as you can. Seek to control the controllables, but do not become agitated about matters that you cannot influence.

Table 2. Sample data and labour quantification. Original quantification submitted in the grant application for EAP794 Nevis. In the event, the project proceeded with two staff members. The scope was slightly reduced, as one group of documents was not accessible for digitisation, with the project achieved in approximately 450 person-days.

|

1) Original documents |

|

|

Common Deed Record Books — 52 volumes x 566 pp. |

29432 |

|

Wills and Indexes of Deeds — 9 volumes x 500 pp. |

4500 |

|

Land Title Register Books — 6 volumes x 395 pp. |

2370 |

|

Estate plans, loose, plus 1 roll — 50 individual sheets |

50 |

|

Court of Commissioners, Encumbered Estates — 2 volumes x 700 pp. |

1400 |

|

Misc. Court Records — 9 volumes |

3000 |

|

Court of Kings Bench/Queens Bench and Common Pleas — 42 volumes x 317 pp. |

13314 |

|

Historic registers of Births Deaths and Marriages — 16 volumes and 5 boxes |

5000 |

|

Miscellaneous other volumes — 34 volumes x 303 pp. |

10303 |

|

Total pages to be photographed (= total images to be produced) |

69369 |

|

Each RAW file (original photographs) |

25mb |

|

Each TIFF file (export format) |

31mb |

|

Total size of RAW files = 69369 x 25mb |

1734225 mb |

|

Total size of TIFF files = 69369 x 31mb |

2150439 mb |

|

Total all files (mb) |

3884664 mb |

|

Total all files (TB) |

3.70 TB |

|

Theoretical rate: 1 page/minute = 60 pages/hour = 420 pages/seven-hour day 69369 images (total)/420 (no. images/day) = 165 person-days |

|

|

Real-world rate: Likely to be half the theoretical figure, therefore: 330 person-days (1 x staff member) Equivalent to 66 five-day weeks or 495 person-days (2 x staff using a single camera setup — assume 50% less productive than one person) Equivalent to 49.5 five day weeks per staff member |

|

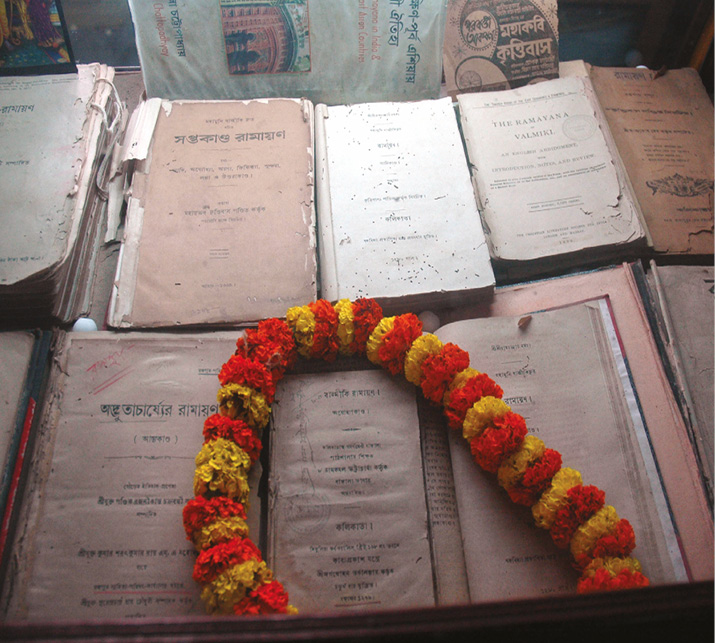

Figure 8. EAP643, Manuscripts prepared for digitisation, Bengal. During this project, religious manuscripts required blessing before digitisation could take place. Photo © Abhijit Bhattacharya, CC BY 4.0.

I hadn’t realised the extent to which the work ethics (attendance, punctuality, loyalty to the project) would differ so much from those encountered at home.

Different parts of the world have different ideas about what is correct behaviour. Local culture and attitudes need to be incorporated into the project plan. In my case, the attitude was very ‘laid back’ and ‘local time’ did not align precisely with the calendar or clock.

Another point, specific to our research field, was the necessity to ‘hand something back’ in exchange for the trust and the time given to us by the document holders. It was not conceivable to ‘waltz in and waltz out’, but these extra activities were inevitably time-consuming.

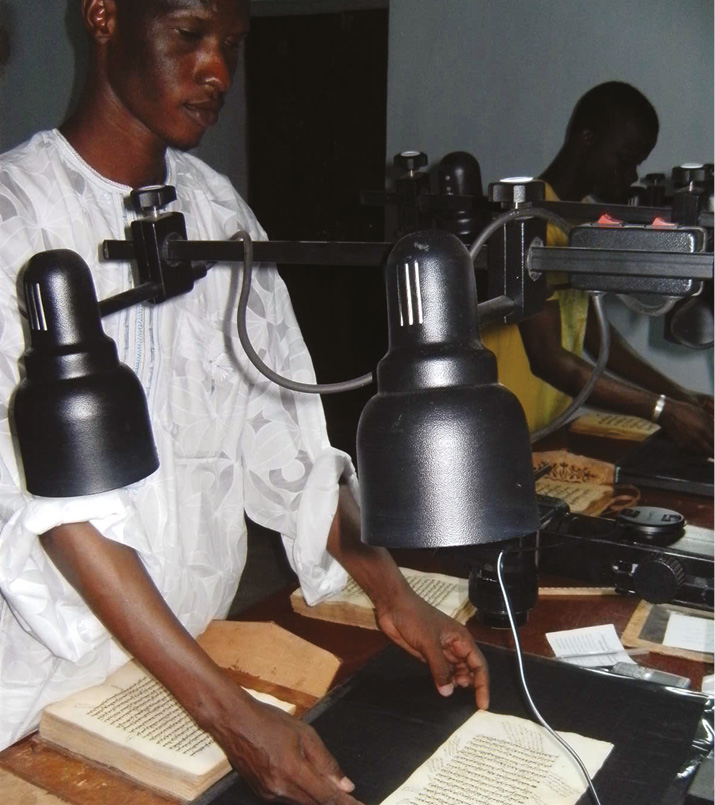

Figure 9. EAP488, An EAP team in action, Mali. A pair of local staff members work simultaneously to digitise manuscripts from Djenné and surrounding villages. Photo © Sophie Sarin, CC BY 4.0.

The local research staff established a rapport with the document holders, returning upon invitation for their special family occasion (ear-boring ceremony, puberty ritual, etc.) when possible. We also organised a visit to the host institution for one of the caste headmen, which helped a great deal to establish a relationship of respect and confidence. We have systematically handed over DVD copies of the documents digitised along with photos of the team and the document holder.

Zoé Headley, EAP458, India

The working conditions in the archive were far from ideal. The archival material is exposed to dust and to the harsh environments. The archival rooms are sometimes visited by rodents but the main threat comes from the termites. At my arrival they had attacked most of the wooden shelves. The new metal shelving, purchased thanks to EAP funding, allowed us to replace the worst of the wooden shelves, while other ones have been repaired by a carpenter in the city. Restoring the shelving and making the archive accessible again were priorities needed to start working and digitising.

Fabrizio Magnani, EAP764, Mali

We mostly dealt with public institutions and had to work within them. These public spaces have their own problems and each of them is unique in nature, for example in terms of working hours: some operated from 2pm till 8pm while others had very short working hours and more than once in a day, such as 9am to 10am and again from 5pm to 7pm in the evening. The team accordingly had to adjust to all of these different timings as well as to holiday schedules.

Abhijit Bhattacharya, EAP643, Bengal

Significant amounts of time were taken in travelling across Freetown from the hotel to the museum and back, meaning working days were severely truncated. For the 2016 visit to reshoot, we moved the camera equipment and archive items to a bedroom in our hotel; this overcame the issues of heat, dust and vibration, and also allowed work to commence without a two-hour journey across Freetown!

Tim Procter, EAP626, Sierra Leone

Financial contingencies and other considerations

Finally, having arrived at estimates for labour, and also having calculated the equipment costs, it is necessary to consider the risk of overspending and the means of protecting the project against this eventuality. This is achieved through a budget contingency.

Every budget, however confident you are about its accuracy, should contain a contingency. This is necessary for reasons such as:

- Price inflation. The cost of budgeted items may change, whether this be equipment, flight costs or accommodation.

- Additional purchases. Despite meticulous planning, not all costs can be anticipated. There will always be peripheral purchases that have not been thought of.

- Currency fluctuations. For overseas projects, when the grant is paid in one currency but spent in another, a changing exchange rate may make locally-incurred costs and staff wages more expensive. The volatility of the currency markets at the time of writing emphasises this risk.

- Risk management. Broken, lost or stolen equipment may need to be replaced, wasted field visits may have to be repeated, while costs that are either unlikely or totally unexpected (damage to a hire car, for example) may be incurred. It is important that, within reason, the project is insulated from such eventualities.

In some cases, the financial contingency for a project may be allowed as a lump-sum under its own budget heading. However, this is relatively unusual, as grant-awarding bodies are generally unwilling to allocate money to non-itemised costs, or to cover ‘what if’ scenarios. It is more common (although less transparent) for a project contingency to be built in across the entire budget. This can be achieved by means of one, or a combination, of the following:

- Get accurate current costs for budget items, but do not use the lowest possible costs for budgeting. Remember that the actual costs at the time of purchase, which could be six to twelve months later, may be higher.

- Giving conservative (i.e. worst-case) costs for budget items about which you are least certain, or those which have the greatest potential to push your budget into overspend if your estimate is too low.

The overall size of the contingency needs to be determined on a project-by-project basis. Again, this is based on the perception of financial risk. How confident are you in your cost estimates? How much control will you exercise over the project, or will a great deal rest with other people, or hinge on capricious local circumstances? For whatever reason, what is the potential for matters to go wrong, with expensive consequences? In all cases a minimum of 10–15% of total budget is advisable.

10% of EAP grants are held back until their successful completion. This means that, if you spend up to the grant limit, you will be temporarily out of pocket. You will therefore have to consider how this temporary shortfall will be covered.

When bringing equipment into a country where it will subsequently remain, it typically has to be declared and will be subject to import tax. This sum must either be factored into your budget, or avoided by obtaining a customs waiver.

A very short drop can destroy one’s equipment, especially laptops and external hard drives […] Take one more camera and one more laptop than you think you’ll need.

Michael Gervers, EAP 254, EAP340, EAP526, EAP704, Ethiopia

There was a change in government following the sudden death of the President […] Then came 49% currency devaluation which pushed all prices of commodities above the approved budget. There was a scarcity of fuel which, when available and only on the black market, was twice the recommended pump price.

Joel Thaulo, EAP797, Malawi

At the time of submitting the detailed pilot project, the exchange rate was 1 GBP to 700 but at the time of the funds transfer, the local currency had appreciated and was trading at 645 to a Pound. However, prices of goods remained unchanged, meaning that we spent more than we had budgeted for.

Hastings Zidana, EAP714, Malawi

Mid-way through the project there was a substantial drop in the value of the Pound against the US Dollar and the other local currencies that I had to deal with. This substantially reduced the real-life value of our grant by several thousand pounds. Fortunately, economies made elsewhere in the project, combined with the built-in contingency, allowed us to achieve the project scope within the original budget.

Andrew Pearson, EAP794, Nevis

1 A more detailed discussion of collection preparation and survey is given by Anna Bülow and Jess Ahmon, in Preparing Collections for Digitisation (London: Facet Publishing in association with the UK National Archives, 2011).