6. On the ground

© Butterworth, Pearson, Sutherland and Farquhar, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0138.06

Where the preceding chapters have dealt with technical standards and processes, this chapter is concerned with on-the-ground practicalities. An alternative title might simply be ‘getting it done’. What is offered here cannot ever be comprehensive, as each project will operate within a unique set of circumstances. Indeed, the best advice is to understand as much as possible about your own project before launch, and if you are travelling to deliver your project then be prepared to improvise when you get there! Nevertheless, knowledge is power, and in compiling this chapter we have drawn on the experience of numerous EAP grant holders, and hope to pull out some of the common themes. If nothing else, we hope it provides some food for thought.

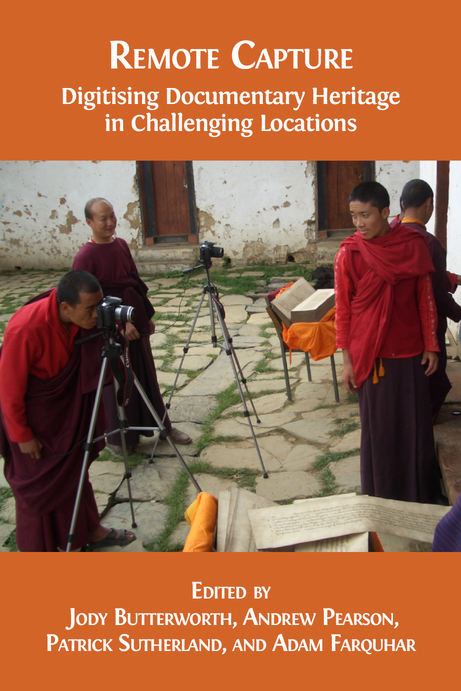

Figure 39. EAP526, Theory meets practical realities in Ethiopia. Photo © Michael Gervers, CC BY 4.0.

Figure 40. EAP688, Fragile subjects. It is not only the local circumstances that will complicate your project; often the physical state of the materials themselves will pose significant challenges, as here in St Vincent. Photo © Kenneth Morgan, CC BY 4.0.

On nearly every expedition, one or more of the team members (including local participants) has been seriously ill, but usually for no more than three days. It is best to have the recommended inoculations before departure, and to take a supply of medications.

Michael Gervers, EAP 254, EAP340, EAP526, EAP704, Ethiopia

The project team

Before departing for the project, you and your staff may require:

- visas;

- work permits;

- travel insurance (it is crucial that this includes cover for work-related activities);

- professional insurance (if required);

- immunisations.

Also consider the actual travel arrangements. Everything should be booked (flights, accommodation, airport transfers etc.). Any local partners should also be informed of the date and time of your arrival!

This is paramount. We all tolerate ‘risk’ in our everyday lives, but when undertaking a work-based project you have an additional responsibility to protect yourself and your staff. Failure to do so is simply unacceptable: it potentially exposes project personnel to danger, and yourself and your employer to prosecution for negligence.

If you are working for an academic institution or commercial company, these will have rules that require a formal risk assessment to be carried out. If not, undertake one anyway. This is not a box-ticking exercise, another burden of a bureaucratic age. Rather, it is an absolutely essential means of ensuring that you give due consideration to the theoretical dangers that you or your team may be exposed to. Risk assessments usually comprise four basic stages:

- an identification and quantification of risk (i.e. what potential dangers can you foresee, what is the worst-case outcome, and how likely are these to actually happen);

- formulation of control measures or ‘mitigation’ (i.e. the means by which you will avoid the dangers, reduce the likelihood of their occurrence, or lessen their potential impact);

- an assessment of ‘residual risk’ (i.e. those that remain after you have implemented control measures);

- an overall assessment of the acceptability of the project (i.e. while dangers will always remain, and accidents can always occur, are the risks now within acceptable parameters, both in terms of likelihood and severity of outcome?)

For those without experience of undertaking risk assessments, this process may seem abstract. However, it is little more than common sense: identifying a problem and finding a solution. Below are three examples:

- Lone working and travelling. Risk: if travelling somewhere remote, perhaps on poor roads, what would happen if you crashed your vehicle? How long would it be until you were missed? Control measures: adopt a Travel Safe Plan of Action (TSPA). This will set out the route you will follow and the time you expect to arrive. It should be lodged with somebody with whom you can confirm your safe arrival, or who can raise the alarm if you become badly overdue. Ensure your vehicle is roadworthy. Carry a mobile or satellite phone. Consider hiring a local driver who is experienced on these roads.

- Poor/unhealthy water supplies. Risk: contracting a waterborne disease. Control measures: buy bottled water; carry a water purification kit; carry anti-microbial drugs (making sure they are suitable for the disease environment you are working in: not every antibiotic is effective in every situation).

- Political instability/civil disturbance. Risk: danger of violence to project team. Here, no control measures are likely to be practical, since the situation is not within your control. Seek advice from your own government about whether it is advisable to travel. Seek advice from local people about the nature of the problem, how and where it is manifesting itself, and what could be done to stay out of trouble. A judgement can then be made about whether to proceed.

Working in semi-urban and rural areas of West Bengal itself is a painstaking task, purely due to bad roads and poor public transport networks. Added to that was the question of safety, while frequent power-cuts and road disruptions for political agitation or some other issue were part of daily life for our researchers.

Abhijit Bhattacharya, EAP643, Bengal

Check your insurance. If your employer is insuring you, make sure they are aware of what you are doing. Check if you have to submit a risk assessment. Alternatively, make sure that your personal insurance provides complete cover.

Tim Procter, EAP626, Sierra Leone

We have always found that to be successful when working in churches locally it is essential to travel with an ecclesiastic who is well known to, and respected by the community where one would like to work. In one case the bishop appointed the paymaster to accompany us. He was highly respected by the monks and remained with us nearly for the entire duration of the time we spent at the site. We were surprised one day to find that he carried a pistol in a shoulder holster under his smock.

Michael Gervers, EAP 254, EAP340, EAP526, EAP704, Ethiopia

Violence during electoral campaigns can seriously affect the viability of planned projects. Even with the help of the partner institution on the ground, tensions of this kind make it difficult to carry out an Endangered Archives project, especially if the documents are kept by public administration offices. Election dates can be changed unexpectedly.

In my case, I had to postpone the activity on two occasions. I was delighted about the British Library’s realistic approach; there are no pressures to proceed with planned schedules; the project is not lost. This is very positive.

Your equipment

- Assemble all the kit and test it!

- Make sure you are totally familiar with how everything works, both in terms of hardware and software. Practice assembly, disassembly and cleaning.

- Undertake a trial digitisation. Try to make this trial sufficiently long and as ‘real’ as possible, to uncover any problems that could occur. The less learning and troubleshooting you have to do on site, the better.

- Consider insuring the equipment. This may or may not be feasible, as many insurers’ requirements (for example about security) are too stringent for a remote or unusual project to be able to comply. Give yourself time to shop around, and if your project is in an unusual location expect your application to be referred to a broker. Read the insurer’s small print and, when making the application, be totally transparent about what you will be doing. If your circumstances change at any stage (for example, moving your ‘studio’ from a specified place of work to a new location), it is essential that you inform the insurer to confirm the policy still applies.

- Related to the above, find out as much as you can about where you will be working. How secure (or otherwise) is it? What locks does it have? Are there window bars?

- In parallel, think about equipment redundancy. In other words, how will you deal with loss, damage, theft or confiscation? Do you have a backup plan, either by carrying a spare of every essential item, or are you confident that there are places locally where you could buy a compatible replacement?

Much of our equipment was stolen from one of the archives on two separate occasions. Fortunately, we never kept all of the equipment in the same place at the same time. The first burglary left us with half the equipment and we only had one archive left, so that was fine. The final burglary left us with one set of equipment, but we were almost done.

Courtney Campbell, EAP627 and EAP853, Brazil

Figure 41. EAP061, A custom-made copy stand, Indonesia. An ingenious solution to the lack of a copy stand. During this early EAP project, as in many since, grant holders have had to depart from the ‘textbook’ in order to get things done. Photo © Amiq Ahyad, CC BY 4.0.

Logistics

Working in distant, and possibly remote, locations requires thought to be given to logistics. In terms of equipment, this should be considered at an early stage because it may dictate what purchases you make, and where you make them.

- Place of purchase. As discussed above, it is advisable to buy, assemble and test the core digitising equipment prior to it being taken to its point of use. However, some items may be heavy or bulky, while it may not be permissible to transport others — for example, anything containing chemicals or solvents.1 If such items are available for purchase locally, consider whether they are best bought on arrival.

- Means of carriage. How do you plan to transport the equipment to the point of use? Will you carry it as luggage, or box and ship it separately? Both methods have benefits and risks. Carrying the equipment means that (lost luggage aside) you can be confident that both you and it will arrive at the same time. However, as all travellers know, aircraft baggage can be subject to rough handling or careless inspection by customs officers, and thus possible breakages. It also has to conform to airline size and weight limits — and to what you can physically carry! Freight shipping allows for the transport of larger consignments, but shipment needs to be made well in advance of your own arrival.

- Be aware of local import laws. If you are bringing equipment into a country, do you have the relevant paperwork? If the equipment is to remain in the country, have you obtained a customs waiver, or will there be duties payable? Follow correct procedure. Failure to do so can lead to difficulties at the point of arrival, and plausibly to the confiscation of equipment. In states where there is a problem with corruption, make sure you do not give customs officials any pretext to extract payments or to make a confiscation.

Figure 42. EAP698, On the road in Vietnam. Photo © Hao Phan, CC BY 4.0.

If you are shipping equipment by sea, try to find an experienced shipping agent with strong in-country connections, and make sure you know what the procedures are supposed to be at the receiving end.

Tim Procter, EAP626, Sierra Leone

Do not take the delivery times advertised by freight couriers on trust. For more unusual destinations, where a particular courier doesn’t have its own supply network, ‘guaranteed six-day delivery’ may be closer to six weeks. This was my experience — despite using a very well-known company. Ask somebody at the destination which courier has a local office and a reputation for reliability.

I am regularly searched when entering the country and have to justify each piece of equipment. I have always been able to negotiate and have not, to date, had anything confiscated. This was particularly trying when I brought a laptop to donate to a state organisation: I was accused of subverting the rules even with the representative of that organisation waiting at the airport with all the necessary importation papers.

Your data

The primary aim of your project will usually be to generate digital data. You therefore need to have clear plans for how it will be stored, transferred and protected. Consider the following:

- Where will your primary dataset be held (e.g. on your computer hard drive, camera memory cards or an external hard drive)?

- What is your strategy for backing up your data? Will you make copies to other hard drives or transmit it electronically? If you plan to do the latter, are you absolutely sure that a reliable and sufficiently fast internet link will be available to you?

- Where will you carry out each part of the digitising process? Will everything be done on site, or will you be undertaking processing/export and cataloguing at a later stage? If the latter, how (and when) do you intend to check the product, and what opportunities will you have to reshoot any mistakes?

Politics may or may not intrude into your project, depending on its subject, scale and its involvement with local government and bureaucracy. The project may be viewed as harmless, eccentric, or could simply slip under the political radar. On the other hand, it may (as many EAP projects have in the past) become enmeshed in local politics. In such cases the actual digitisation has often been the easy part: EAP project directors commonly need to become diplomats and negotiators in order to achieve what is essentially an academic objective.

A few projects have operated in seriously unstable political environments, where work has been severely disrupted, or had to be entirely abandoned. Here, once again, we return to the issue of safety, and circumstances when personal safety outweighs the requirements of the project.

On the other hand, and especially in small polities, the project may bring you into contact with important individuals. Enjoy the experience, and treat this as an opportunity to talk about what you are hoping to achieve, and emphasise how this might be of benefit locally.

- Be aware of local politics, and the dynamic of political or bureaucratic relationships (for example, personal and inter-departmental rivalries; self-interest; corruption).

- Understand how the local bureaucracy works — and the speed at which it may do so.

- Archives (particularly but not exclusively anything modern) could have political currency for both the regime in power and any opposition.

- Try to be aware that you and your project may be being used for external agendas.

- Information (and its control) may be seen as power. Those who hold that mindset may be suspicious of your agenda and resistant to the idea of open access data.

- Expect problems above and beyond the technical. These could well be your greatest challenge, and consume much time.

Archives are not repositories of fond memories. It is likely that the materials you are archiving hold political currency. The materials may be sensitive to the government, or to its opponents, as they have the potential to reveal and remind the world of unwelcome and unsavoury chapters that can tarnish a nation’s image. Be sure to have a good understanding of the political climate that you are entering into.

Graeme Counsel, EAP187, EAP327, EAP608, Guinea

Avoid timing your project with a general election, when safety can become an issue. An election also brings the prospect of having to establish relations with a new government administration, its ministers, bureaucracy and ideology, after having gone through this process with the previous administration.

Our place of study was effectively a non-democratic country where the government keeps a close watch on ethnic communities. Projects conducted in ethnic communities therefore must keep a low profile and be sensitive to local politics.

I was dealing with several government departments. In most cases they were only too happy to help, but in a couple there was a concern that this was an attempt to take the section of national archives they manage away from their control, or to make money from other people’s archives.

My project digitised court records that were the property of the Registry but which were held in the National Archive. There was no love lost between these different branches of the government or the personnel in charge of them. The project became entangled in these rivalries, and it took a good deal of patient negotiation to obtain access to the records.

In the course of my EAP projects I have met one head of state and several island governors. All have been friendly, down-to-earth and genuinely interested in our work.

Andrew Pearson, EAP524, EAP596, EAP688 and EAP794, St Helena and the Caribbean

Don’t be overwhelmed. In small communities it is likely you will be introduced to very senior people. I had meetings with the Chief Minister and the British Governor. Have at least one good set of clothes for these formal meetings!

Nigel Sadler, EAP769, Montserrat

The relevant local permissions to digitise a collection are a prerequisite of any EAP project, and where possible, should be obtained before a grant application is submitted.

Permission to digitise is also bound up with the question of open access. But, while this concept of accessibility is very much in vogue in academic circles, it is less commonly accepted elsewhere and indeed is a stumbling block that has been regularly encountered during EAP projects.

One of the requirements for EAP funding is that the digitised material is made available online, and for this to be possible, the Endangered Archives Programme needs to receive appropriate documentation. This means the Grant of Permission forms that are on the EAP website will need to be completed and signed. There are two types of form dependent on whether the material is in or out of copyright. Whichever the case may be, EAP only asks for permissions to share the material for non-commercial purposes.

Copyright exists in most countries, and it is the responsibility of the grant holder to know the intellectual property law for the country where the digitisation is taking place. The World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) has a useful website and lists the countries that have copyright law; it includes regional contact details if you need to get in touch with someone.

If the material is in copyright, the grant holder must obtain permissions from the rights holder. EAP requires that this is in the form of a non-exclusive Creative Commons licence for non-commercial purposes (CC BY NC); the form is available on the EAP website. This is the preferred document as it is a simple and flexible licence and allows researchers to understand what they can do with EAP digital material. The ‘Grant of Permission Form — CC BY NC’ uses clear and straightforward English, but it might still be slightly daunting for a rights holder to be asked to sign a document in a foreign language. It is therefore sensible to translate the relevant forms and explanations that are on the EAP website so that the rights holder understands what they are signing and why.

When copyright has expired, the material becomes Public Domain. With this type of material, there is no longer a rights holder, but EAP still wishes to have an agreement with the owner of the physical material and again seeks a licence so that they can share the material for non-commercial purposes (CC BY NC). This makes it clear that EAP knows that the owner is happy for the material to go online, but it also gives the British Library and other researchers clear guidance as to the copyright status of the material. On this occasion, the ‘Grant of Permission form — Public Domain’ would need to be signed. Again, it would be wise to translate the form and any explanation so that the owner fully understands what they are agreeing to.

Where permission and access are concerned:

- When dealing locally, be absolutely clear and up-front about the fact that the images will be made openly and freely accessible. Explain clearly what this means.

- Get as many permissions as possible prior to your departure.

- Top-down permissions may not be enough (or even relevant). Very local permissions may be needed.

- Get permissions in writing. Verbal assent may be valueless.

- Carry multiple copies of all your permission letters, as many local collaborators may wish to keep a copy.

In Ethiopia, to do anything beyond pure tourism, one must have official permissions and authorisations. Because we are dealing with ecclesiastical manuscripts we need written approval from both Church and State. Usually, the higher the office (Federal and the Patriarchate), the less effective the authorisation. The final decision is made by the villagers in the local community. One negative voice is enough to halt all proceedings. Even more difficult to accept is that even when an agreement has been made, it can be rescinded after a few hours, or the next day.

Michael Gervers, EAP 254, EAP340, EAP526, EAP704, Ethiopia

Dealing with particular stakeholders can be difficult. The issues that typify workplaces in your home town will also be apparent in your project space, so becoming familiar with Human Resource strategies with regards to dealing with issues in the workplace is recommended. It might sound rather odd, but successfully negotiating your project through an array of bureaucrats with vested interests is a scenario worth considering.

Graeme Counsel, EAP187, EAP327, EAP608, Guinea

Some of the manuscript owners did not fully understand the preservation and scholarly purposes of the project. In such cases, the project team needed to spend time convincing the manuscript owners to allow them to photograph the manuscripts.

Hao Phan, EAP698, Vietnam

My issues with particular individuals were dealt with by seeking advice from trusted stakeholders. I discussed the problems, the lies, the obfuscations, the pretexts to get money. ‘Local’ solutions were thus offered, and often these were appropriate.

We faced unforeseeable delays and obstacles at almost every step of the way, waiting for months to even get permission from the Central Library to serve as our local host institution. In the case of one participating institution, even after receiving written permission to access and digitise a collection, they did not give us physical access to the collection till almost a whole year after we received the permission.

The biggest disappointment was the en masse withdrawal of a family archive we initially persuaded to work with us. It is difficult to see how we can overcome the basic fear these families seem to share of the political repercussions to themselves of making their private holdings publicly available. However, we also faced a lot of resistance from institutions who were afraid that digitising their collections and making them available at the Central Library would make their own collections redundant and reduce the incentive for potential visitors to come to their institutions. These kinds of attitudes are a real obstacle to digitising and disseminating endangered materials in our country of work.

Obtaining permission from the Government to document the paintings was very difficult and even with the permission, a lot of restrictions were placed upon us. The Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Department of Tamil Nadu Government (HR&CE) and the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) are the controlling authorities of the Hindu temples and monuments of Tamil Nadu. Even though we obtained permission from them, in the case of a particular temple it was very difficult to enter with our equipment because the temple is under the control of local police; we had to wait to get the permission from the official in charge on a daily basis by writing fresh letters and attaching ID proofs.

N Murugesan EAP692, India

Local liaison and partnerships

Figure 43. EAP334, Digital preservation of Wolof Ajami manuscripts of Senegal. Photo © Fallou Ngom, CC BY 4.0.

Local liaison is a core element of EAP projects and is an absolute essential on many levels. At its most basic, this simply involves dialogue with the owners of the materials to be digitised. More commonly, contacts are much more substantive and many projects have been enriched by engagement with local organisations and people. Some points of consideration are listed below, and the subject is also integral to some of the other themes that follow in this chapter, concerning communication, staff and outreach.

- Choose who you trust. Try to do this by obtaining several local perspectives.

- You are an incomer, maybe a ‘guest’. Behave tactfully and respectfully, and watch what you say!

- Keep a sense of perspective: the project may be central to you, but you are not the centre of other people’s worlds. They have everyday concerns, against which the digitisation of manuscripts may seem unimportant and completely abstract.

- Local problems have local solutions.

There may be many obstacles, unclear processes and ‘ways of doing things’ that will be very unfamiliar. These can take up a good deal of your energy, and while reflecting on how to address them is very important, it is also of benefit to discuss the issues with trusted local friends […] Local solutions to local issues can be revealing and appropriate, and sharing problems also helps to limit the stress.

Graeme Counsel, EAP187, EAP327, EAP608, Guinea

Keep your opinions to yourself. This is especially true in small communities. Be aware that if you make a critical comment about somebody, there is a good chance they are a relative or friend of the person to whom you are talking!

Availability of the people was another issue. Most of the people were farmers so it was difficult to meet with them when they had to go for cultivation or harvesting. In such times we had to go to meet with them very early in the morning to at least get the permission to photograph the manuscripts.

Stephen Morey and Poppy Gogoi, EAP373, Assam

From the outset, and throughout the project, it is important that the scope of your project is clearly understood — both in your own mind, and in communication with others. Managing expectations has to be done from the start and is key to building and maintaining trust.

- Be clear about the aims of your project and how you will achieve them.

- Be equally clear about the limits of your remit — in other words, what you won’t be doing.

- Do not make promises you cannot fulfil.

- Where applicable, emphasise local responsibility for the care and curation of the materials. Some projects arrive to find the expectation that they will solve all problems of storage and long-term conservation. Equally, in some former colonial possessions, there is a belief that the old imperial powers have an obligation to fund the protection of records that they generated. This is a particular issue for projects in former British possessions, due to the connection of EAP to the British Library.

- You may ‘inherit’ the legacy of past failures, including promises deemed to have been broken by other incomers.

- Equally, you may be met by complete mystification! What may be obvious to you can be quite novel to others. In such instances, be prepared to explain your work from first principles, including why it has any value.

In forming contracts with the international partners, we tried to be specific about the outcome of each project. In most cases, we specified the quantity of digital objects that the project partners were expected to submit. We also included a timeline for each project.

Hao Phan, EAP698, Vietnam

It is good to have an overview of the expectations of the people from the project and to know if they are happy with what is being done.

We showed them the metadata that we were preparing to convince them that proper record of the manuscripts will be maintained. This was to assure them that their names and family details are being recorded as owners of the manuscripts and that we are not engaged in any kind of business using the manuscripts.

Stephen Morey and Poppy Gogoi, EAP373, Assam

The project’s most tragic find was several earlier instances of chiefly families loaning their historical documents to historical researchers, only to never have these documents returned. This malpractice at times made our own project difficult, as from the start we entered a toxic situation where our team of genuine and honest researchers, following a strict code of research ethics, were immediately suspected, thanks to the misdeeds of earlier ‘researchers’. Families were put at ease not only by the EAP’s policies of not removing materials from custodians but also by the very name of the British Library.

Kyle Jackson, EAP454, India

There was a sense that ‘this had all been done before without success’. I was regularly told that every project with the archives had either failed or eventually lost momentum. This meant there was already doom and gloom about this project’s potential for success.

There also seemed to be a belief that ‘someone else would fund the archive development’ and not the local government. It was difficult to convince the local departments who managed the archives that this was not going to happen, as was trying to get them to understand that the archives needed better care and greater public access.

Be sure also to teach the abstract and historical reasons why preserving this data is so important. Once your partners understand this, they will be more likely to be consistent and to persevere through longer projects.

David LaFevor, EAP843, Cuba

Good communication is critical, but achieving it is far from straightforward. There is no ‘one size fits all’ method of dialogue, and different cultures operate differently. And, while modern technology is the default in the Western world, it may be neither practical nor effective in other places.

- Establish a clear structure within the project team. Who is in charge? Who should be issuing instructions? And, for the people on the ground, who is their line manager or first point of contact?

- Email is the common medium for business communication in the Western world, but this is not always the case elsewhere. Face-to-face meetings are often preferred or, failing that, conversations on the phone. Problems that are seemingly intractable often evaporate when you deal with somebody in person.

- If you do not speak the local language(s), make sure that the project engages somebody who does. Such people will not only help with the practical issue of dialogue, but will also understand the cultural dynamics of communication in that society.

- When dealing with local stakeholders, hold as many face-to-face conversations as you can. Dialogue often becomes much harder and less efficient once you are at a distance.

- If managing staff remotely, set up an effective method for long-term communication.

The lack of face-to-face interaction might create misunderstandings or delay the project. It is thus important to include a travel budget in an international collaborative project to fund meetings in person between the project directors, preferably at an early phase of the project. Communication between the project partners becomes much more effective after such a meeting.

Hao Phan, EAP698, Vietnam

With email having become the main mode of communication at workplaces in the Western world today, it is easy for us to forget that many people in other parts of the world still prefer to communicate by phone or in person.

Hao Phan, EAP698, Vietnam

Some of the locations have been very remote; Quibdo, Chocó (Colombia) was one of the most difficult to reach […] Working in Cuba is always a challenge given the rudimentary communication infrastructure and political difficulties for foreigners who wish to conduct this type of work. The Brazil projects have also presented a number of difficulties stemming from remoteness.

David LaFevor, EAP843, Cuba

After training staff and volunteers I was then available via email, Skype and other internet forums during the three month Pilot Project to help and advise when necessary.

Nigel Sadler, EAP769, Montserrat

All of the problems mentioned were effectively solved by the project team who were patient, persistent, and flexible. The key in dealing with these problems was the fact that the project team included two scholars of Cham ethnicity who are highly respectable people in Cham communities. Other members of the team are also Cham who speak the Cham language and understand Cham culture.

Hao Phan, EAP698, Vietnam

Although it seems obvious, sometimes we tend to forget that people of different cultures communicate in different styles. A straightforward message from the perspective of an American may be perceived as insensitive by a person from Southeast Asia. We indeed came across a misunderstanding situation with a project partner when trying to urge them to meet the project deadline. When we sent the project partner an email informing them what might have happened with the funding if the project deadline was missed, it seemed that the partner interpreted the message as a threat to eliminate the funding and reacted quite negatively.

Hao Phan, EAP698, Vietnam

Many EAP projects work with local staff, who often become crucial to their success. The post-project legacy of knowledge and skills is a long-term outcome of great value. However, staff management can be complex, and problems can be exacerbated if you are attempting to run the project remotely through local operatives.

- Think very carefully about the wages you are paying. Local wage rates can often be extremely low and a minor part of your overall budget. As you train somebody they may become more employable in other walks of life. Do not lose talented staff over the matter of paying a few extra pounds per day.

- Despite your best efforts you may still lose staff. Design your training to ‘cascade’ (i.e. local-to-local) after your departure.

- Delegation of tasks has to be based on your view of staff competence. In terms of skills legacy, and also because it reduces your own burden, one should ideally delegate as much as possible. However, repairing mistakes or shoddy work takes a disproportionate effort. Regularly review the division of labour over the course of the project.

- Create strong line-management arrangements, through which you retain authority, and in which everybody knows who is answerable to whom. Have a single person responsible for training and providing subsequent advice: avoid the opposite situation, where multiple people give contradictory advice.

- If managing staff remotely, set up a system of regular progress reports, and keep lines of communication open. In this way you can stay on top of the project, while the staff won’t feel isolated and cut adrift.

- Keep a close eye on the digitised product that is being generated. Do so regularly, so that any technical mistakes are not replicated over multiple documents and any laxness is seen quickly.

- Consider a means of ‘leverage’ for local staff. How can you avoid a situation in which you become totally reliant on them, but without any control over when they work or the quality of the product? This might be through control of money — for example by paying retrospectively on submission of satisfactory work. Alternatively, consider seconding staff who are employed by local government: these will have a line manager who is ‘on the spot’. At the end of the day, it is a balancing act. You must trust your staff, whereas a lack of faith, financial ransom or overbearing management will be potentially toxic to the working relationship.

Figure 44. EAP627, Staff training in Paraíba, Brazil. Photo © Courtney Campbell, CC BY 4.0.

Having a local team that can carry out the work effectively is essential for the success of an EAP project. Members of the project team should include people who belong to the communities that possess the target materials. These team members know best how to work with people in their communities and can overcome many challenges that might be very difficult for an outsider to solve.

Hao Phan, EAP698, Vietnam

The team must include at least one person who is highly proficient in the use of technology. This person will ensure the work carried out meets the standards of EAP and help the team deal with emerging technical problems while working in the field.

Hao Phan, EAP698, Vietnam

I trained several people on how to use the equipment, how to digitise archives in the most effective way and how to handle the archive material to safeguard it. Some of these people have now trained further people to help in the continuing digitisation work post-project.

Nigel Sadler, EAP769, Montserrat

We wrote detailed ‘process notes’ as part of the training programme. These notes allowed the local staff to have material that reinforced their training, and which acted as a point of reference for anything about which they were unclear. It also allowed them to train others in a correct, structured fashion after our departure.

Andrew Pearson and Ben Jeffs, EAP596, Anguilla

Recently we have had to redo several family collections because the images were too small. Such mistakes are frequent because the locally trained staff are still not totally computer literate and sometimes do not know the difference. Despite repeated training sessions such mistakes occur and the digitisation needs to be extremely closely monitored.

Do not trust entirely that people are doing their job: check and recheck!

I was amazed at the high level of technical understanding of digital systems that some of the quite young employees had. We learned from this ‘digital youth’.

Martin Jürgens, EAP086, EAP177, EAP326, Laos

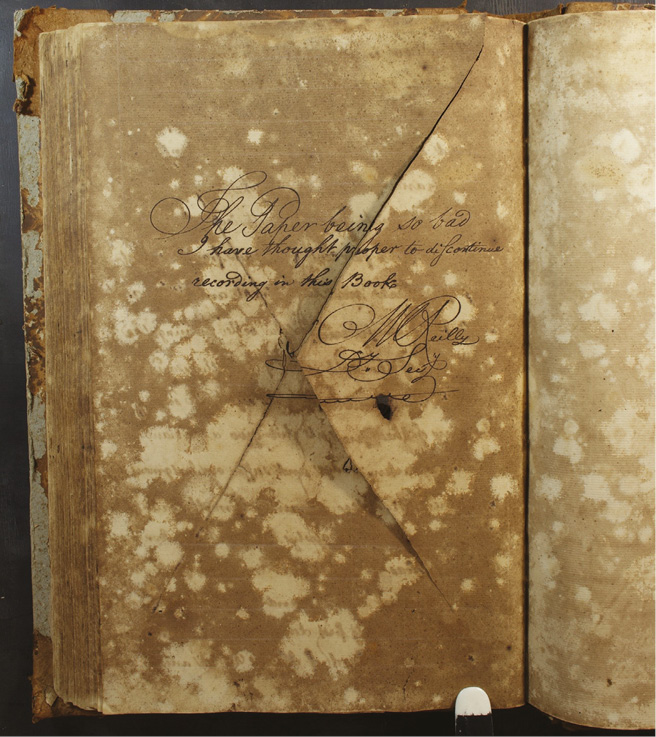

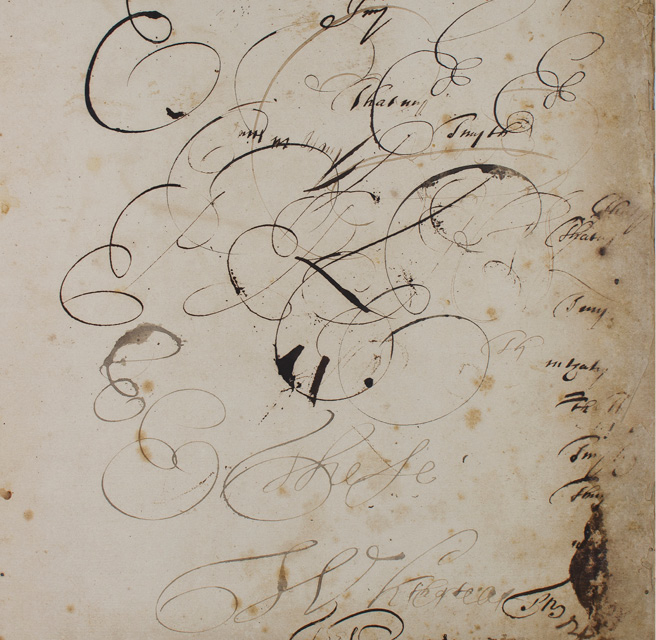

Figure 45. EAP524, Historic doodles.It is not only modern staff who have the potential to become bored and distracted, as evidenced by this seventeenth-century East India Company document from St Helena. Photo © Andrew Pearson, CC BY 4.0.

Money — and financial management — lies at the heart of the project. As many grant holders have found, however, it is often one of the most difficult issues to deal with. It is also potentially one of the most stressful, particularly when parting with substantial sums of money to third parties.

- Keep detailed records of all spending, no matter how trivial. If you do not record them, small unreceipted expenses may ultimately add up to sizeable ‘gaps’ in your accounts.

- Update your accounts regularly. Do not return home with a huge bag of receipts and expect to remember every detail of the amounts spent, and on what!

- Obtain receipts for as much as possible. If necessary, carry your own receipt book and ask vendors to fill it out.

- Be aware of the accounting requirements of your host institution. If you do not conform to these, you may find you cannot claim for everything you’ve spent and could end up personally out-of-pocket. This is particularly true in respect of small unreceipted outlays while travelling.

- When transferring large sums to third parties, make sure that there is a clear audit trail. Write or email to inform them that the funds have been transferred; ask that they confirm receipt.

- The vast majority of people with whom you deal will be honest and scrupulous. However, be aware that corruption does exist and in some places is endemic. Where this is a concern, make sure you understand as much as possible about the situation you are dealing with. Again, having an audit trail is critical.

- Foreign money transfers might well be new to you and parting with large sums by ‘Forex’ may be stressful. At the most basic level, you may not be confident about the transfer process: am I doing this right? have I been given the correct account details? More fundamentally, as noted above, you may be worried about losing the money to a potentially corrupt individual or system. In both these scenarios, consider an initial ‘test’ transfer. Make sure the funds arrive safely and are correctly assigned. Similarly, rather than sending a single lump sum (e.g. for staff wages), send a series of incremental payments, thus minimising your risk.

- As in so many other aspects, seek local advice and where possible draw on the experience of others who have worked in the same region or country.

While there were many who were enthusiastic about the project, there were some key individuals who were set on frustrating its progress at every opportunity. On more than one occasion I was lied to; there were pretences such as equipment not working or the necessary permission to archive particular materials had not been given, an auxiliary room with project materials was said to ‘not exist’, and the huge archival task I had in front of me was often dismissed as being impossible to complete. I could not fathom this recalcitrance and obstructiveness (and often, rudeness), until I came to the conclusion that my project did not offer certain individuals sufficient financial incentives. I surmised that the archival collection had remained unarchived for so long, even though specific equipment and personnel had been assigned to the tasks, due to key managers waiting for the ‘big project’ to come along, with a lucrative budget to match.

A major cause of disagreement often concerns money. In order to avoid any misunderstanding, a written contract should precede any exchange. Any financial agreement should be written down and signed by all parties concerned, including witnesses.

Michael Gervers, EAP 254, EAP340, EAP526, EAP704, Ethiopia

The manuscript owners proved extremely hesitant in letting us photograph the documents in the beginning, while the local administration saw the project as a form of theft. There is still a belief in town amongst some that when the EAP are digitising they are selling the images for a lot of money and that hardly anything trickles back to the manuscript owners.

If you are anything other than an Ethiopian, you will be considered wealthy, hence be prepared for constant demands on your pocket. At the same time, you will be warmly appreciated if you leave tips for the chamber maid, the bell boy and the many other workers with whom you come in contact who subsist on meagre earnings. Your long-term driver should also be recognised for keeping you alive. On the other hand, there is no need to tip at the petrol/gas station, or in taxis. In restaurants, 5% is enough.

Michael Gervers, EAP 254, EAP340, EAP526, EAP704, Ethiopia

Our project’s hardest lesson came from financial stewardship. The transfer of large sums of money into official accounts does not mean that officials will act honestly, and this is particularly dangerous in regions where such large transfers are common, and in which the disparity between wages and the bulk transfer is large. Certain politicians and several local corporations are notoriously corrupt. An easy-money ethos seems, tragically, to have somewhat crept into state-run universities as well.

The mistrust of our intentions is still something we have to deal with daily. The fact that we offer a small payment per day for the manuscript owners while we are working on their documents does help.

Do not equate a business relationship with friendship. If you entrust property of any kind to a local, be sure to have the agreement about its return in writing and signed by all parties, including witnesses.

This section concerns peripheral activities that may occur: local liaison, outreach, and publicity. These are practically useful to the project, but are also highly rewarding. Indeed, many grant holders have found this to be the highlight of the project. Grant holders have engaged with schools and local societies, while others have reached out into the broader community. When carrying out this outreach, it is important to be even-handed with competing media outlets.

Figure 46. EAP051, BBC World Service radio programme on the importance of Bamum manuscripts, Cameroon. Photo © Konrad Tuchscherer, CC BY 4.0.

Publicise, publicise, publicise. The mission of the EAP is inherently attractive, and even more so amongst more localised people who are intensely interested in their historical identity or identities. Local universities and colleges jumped on every offer we made to teach their undergraduates about our digitisation project and the ‘future of history’.

Kyle Jackson, EAP454, India

Get involved with local events if possible, even if they don’t relate to your project. They will provide a great chance to not only promote your project but also to meet people who might be able to help. I was taken to a lunch on my first Sunday but on the way back the driver took a detour to a friend’s house where there was an informal drinks party going on. I ended up talking with the committee members of a local organisation who were happy to recount their experiences of growing up in Montserrat. These same people then kept turning up at formal meetings so we were able to talk about lots of things.

Nigel Sadler, EAP769, Montserrat

The most surprising achievement was that following a presentation to the town council, we received donations of numerous boxes of materials from private collections. These included the entire collection of Mariano Sendoya, author, historian, and former mayor of Caloto. This collection has not yet been inventoried, but contains both original archival documents as well as unpublished manuscripts by Sendoya. The other donations were mostly by members of a now defunct historical society. Some of these were from private collections, while others were materials that were taken from the Caloto archive in 2004 after a town employee intentionally set fire to the archival collection, which was in complete disuse.

Thomas Desch Obi, EAP650, Colombia

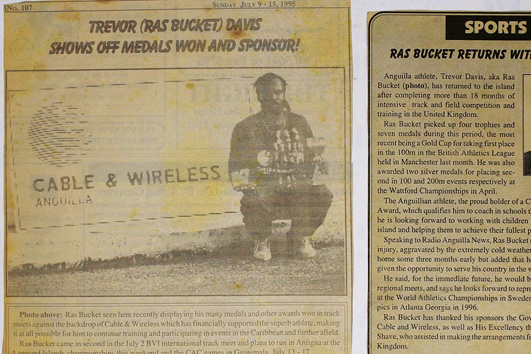

As a part of our search for privately-held documents we held a ‘digitisation day’, hosted by the National Library. The event was publicised on radio and in the newspapers, inviting local people to bring in any family documents or photographs that they would like to share. There was an excellent response and, amongst much ephemera, there was some interesting and unusual material. The collection that sticks in my mind belonged to Trevor Davis (alias ‘Ras Bucket’) an athlete who had competed for his nation at regional and world championships. He brought in photographs and newspaper clippings that spanned his whole career. We photographed these, and the images are now part of the island’s archive. Practically none of our digitisation day related to our core project scope, but as means of engaging public interest and showing what we were doing, it was invaluable.

Andrew Pearson and Ben Jeffs, EAP596, Anguilla

The project should also focus on the benefit of the community. The support of the community is very necessary in the smooth running of the project and this is possible only when they realise that they are also going to benefit from project work.

Stephen Morey and Poppy Gogoi, EAP373, Assam

Make as much use of local media as you can. The EAP project in Montserrat was covered in the local newspapers before and after my visit to Montserrat and I also took part in a radio interview to outline the work and answered queries from listeners. I also got invited onto another radio show to talk about the First World War research I had done on Montserrat which allowed me again to promote the EAP and the possible uses of archives.

Nigel Sadler, EAP769, Montserrat

Figure 47. EAP596, Newspaper cuttings photographed as part of the Anguilla EAP’s ‘Digitisation Day’. Photo © Andrew Pearson, CC BY 4.0.

1 Check, for example, whether a freight shipment can contain spare batteries. Often, batteries for cameras and computers are allowed to be transported within those pieces of equipment, but extra batteries (i.e. loose within the shipment) are prohibited.