Conclusion

© Jody Butterworth, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0138.07

The Endangered Archives Programme has had projects around the world from Armenia to Zanzibar. News of the Programme has even made it to the most remote inhabited island of Tristan da Cunha, which has had exceptional issues all of its own with only nine shipments to the island a year and low broadband speeds, making it impossible to send sample images to the EAP office for approval. However, despite the various difficulties that each project has had, the fact that we now have over six million images online is a testament to the successful outcomes of the projects which have been supported so far. The sorts of locations where digitisation has taken place have included desert oasis cities, remote mountainous villages and faraway islands; some of the EAP teams’ experiences have been unique, while others have shared common elements.

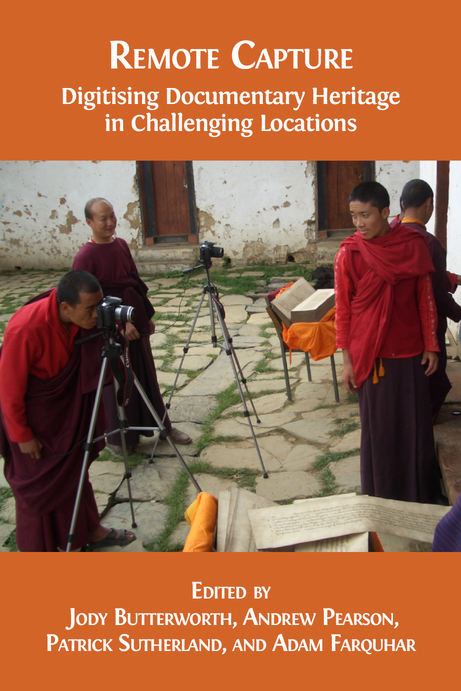

We hope you will have found the information in these pages useful. You now have all the tools at your fingertips to embark on a digitisation project of your own. You will realise that to plan and undertake a project is no easy task; the preparation, scheduling and organisation must be done a long time in advance. No matter how well prepared you may be, you may face unexpected setbacks, but hopefully the advisory quotations and vivid images from past project holders (who we fondly refer to as the ‘EAP Alumni’) will inform and inspire you. With any luck, they will help you realise that even in unconventional situations and with sometimes seemingly insurmountable problems, ingenious solutions can be found.

You may have already come to the conclusion that a digitisation project is feasible and achievable and is no longer the daunting prospect it might have been. Perhaps, however, it is important for us to stress the personal rewards you might receive if you choose to go on such an exhilarating journey and it seems fitting that the last words of this publication should be written by an EAP grant holder.

Figure 48. EAP177, Delivering the goods: hard drives ready for postage from Laos. Photo © Martin Jürgens, CC BY 4.0.

EAP051 changed my life — forever. Today I am a different man and scholar than I was only a few years ago. As a result of my time on the ground and work in our EAP project a window has opened to a whole new world of knowledge that was previously impenetrable to me. The world I speak of is a long-forgotten world in the Cameroon Grassfields, a world far away in time from its same location today. It is the Bamum Kingdom, as it once was, long ago, its voice coming alive to me through marks on crumbling paper 100 years old. Imagine a religious epiphany combined with the eureka moment of discovery, for that can only describe the feeling I had when I read a private letter from King Njoya to his closest friend, Nji Mama, as Njoya lies on his deathbed, far away from home, in exile. I collected that letter and I am the first person to read it apart from its original recipient some 76 years ago. It made a difference that I deciphered the characters of the Bamum script myself, written in the dying king’s hand. It made a difference to me that I read and understood its message in its original language, Bamum (Shupamom). It made a difference to me that I was the one who unscrambled Njoya’s dating cipher to identify when it was written. I experienced that sense of illumination 500 times during our project work. My time collecting, organising, copying, and exploring Bamum documents has armed me with an ability I never dreamt possible. I know every inch of the literate legacy left behind by the Bamum people — not that I have read and understood it all (far from it), but that I know where to find it. Today I am fluent in both the Bamum script (and functional in many of its archaic variants) and the Bamum language. The stage is set for the remainder of my career, which entails probing the documents as a historian, using them to write a Bamum history, which includes an insider perspective based on the written records left behind. For the historiography of Africa, this is a rarity; the possibility of utilising first-hand written records of Africans in the form of an original script, to reconstruct history.

All of the men and women who have been involved in the EAP work feel they have been involved in something truly monumental (and all have been publicly recognised by the Bamum King for this work). But the Archives Du Palais Des Rois Bamoun is more than a monument to me; it represents a lifetime of work ahead, tapping into evidence never before consulted by scholars.

Reflecting on my EAP experience, it was never easy going. We worked long hours around the clock, which had a physical and mental toll. There were the long periods of separation from my wife and children while I was in the field, which were lonely for all of us. I suffered from bouts of sickness ranging from dysentery to malaria, lost significant weight, and was arrested on two occasions by corrupt military police (both times the Bamum King coming to my rescue). Looking back, though, I would never airbrush these experiences from my memory, as they made me a stronger person.

I have only good memories. We worked together as a team, behaving like brothers to one another, all working toward a common goal that we all believed in (and continue to believe in). We worked under the patronage of a king who supported our work. The king came to my aid when I needed it, welcomed me into his home, and at the end of my time in Foumban awarded me with one of the highest ranks in the kingdom for my work on the EAP project (the title of ‘Nji’). My relationship with the Bamum Kingdom will only grow stronger…

Konrad Tuchscherer, EAP051, Cameroon