1. The Tumbling Worlds of

Henry Adams

© 2018 Jan M. Ziolkowski, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0146.01

Adams Family

—ascribed, by cinematic license, to

John Quincy Adams

From the 1890s on, the ground for the reception of the medieval tale Our Lady’s Tumbler in the United States was readied among the elite. Yet the individuals and media involved in the projection of the story in the New World before the cultured public are only loosely comparable to those who from the 1870s on motivated the success of the medieval poem and the fin-de-siècle short story in France. Among the authors who ensured that cultivated readers would be acquainted with the narrative, one stands out: Henry Brooks Adams. He contributed in major ways to the hearty American response. Not a translator in the strict sense, but not a short story writer either, he managed through an amalgam of philosophizing and historical musing to promote the medieval minstrel. More broadly, he propelled the equally zestful Americanizing of the Middle Ages in universities, museums, and other cultural institutions in the early twentieth century. He stood out as far and away the best-known panjandrum among those of his times who helped to transmit the French poem to a large and enthusiastic readership of his countrymen.

Neither a philologist like Gaston Paris nor a recognized author of fiction like Anatole France, Adams defies easy pigeonholing, professionally and personally. As a onetime historian and an on-again, off-again medievalist, he may seem an odd man to have taken up in his later years the role of Prometheus. In this guise, he rolled back the centuries to explore the Middle Ages so that he could bring forth to America what he chose to understand as their luminosity. He carried the torch of his distinctive medievalism to a world only lately afire with incandescent lighting. By just a few decades, he anticipated mushroom clouds from atomic bombs. Because his seeming clairvoyance rendered him an object of fascination to many throughout the twentieth century, he deserves our close attention. His life has much to disclose about the medievalism of the nineteenth century that prepared the way for the success of medievalesque literature and architecture in the decades to follow. Although much about him is sui generis, his conception of the Middle Ages and of the Virgin Mary as unifying counterweights to the threatening multiplicity of modernity can tell us much about why many of his countrymen embraced Our Lady’s Tumbler and why his nation rode surges of Gothicizing construction long after the vogue had ended in the Old World. To come to terms with any of these developments, we need to fathom his cultural and intellectual formation.

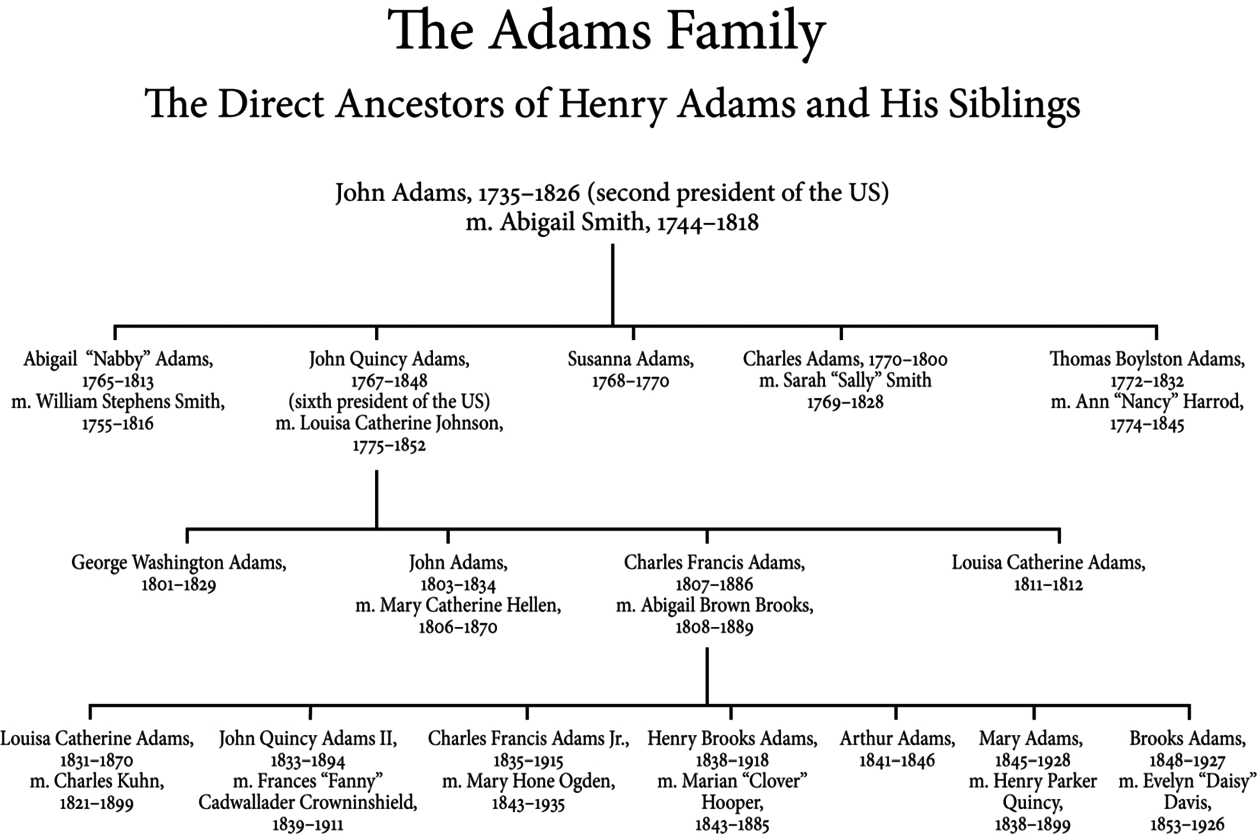

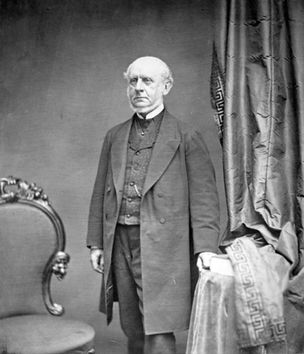

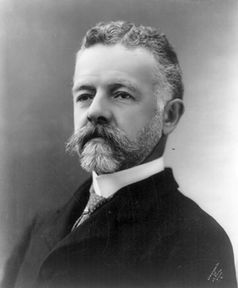

As his family name hints, Henry Adams issued from an illustrious lineage (see Fig. 1.1) of Yankee blue bloods, if that last accumulation of words is allowable and not intrinsically incompatible. Across the generations, the purebred genealogy of Adamses propagated men who were distinguished in national politics, talented in writing, and hard to handle in personality. His bloodline was closely conterminous with the nineteenth-century history of his nation. To look only at the ancestors of whom he was a direct descendant, and to start at the beginning, he was the great-grandson of a Founding Father, John Adams. The second president of the United States of America, this Adams was the first one to occupy the White House. Henry was also the grandson of John Quincy Adams, the sixth chief executive of the nation and congressman for two decades after he held the highest office; and he was the son of Charles Francis Adams Sr., by turns politician and diplomat. In the latter capacity, Charles served during the Civil War as minister to Great Britain, the equivalent in those days to an ambassador (see Fig. 1.2). All these preceding Adamses became imagoes that informed the reactions of Henry to the present and past alike. Whatever else he made himself, this scion of the distinguished family was an Adams, bred to bear the burden of illustrious predecessors.

None of Henry Adams’s living relatives wielded sociopolitical influence on a par with that of their presidential predecessors. Even so, the gentry to which he belonged stayed wealthy and prestigious. He knew that he had been to the manner born, with a silver spoon in his mouth. In today’s nomenclature, he possessed a bushel basket of unearned privilege. Even so, by his generation, the power of the great Adams kinship group was indisputably waning. Having special perquisites and being groomed for success could take his three brothers and him only so far. Of the four, Henry alone neither earned a law degree nor held public office. In fact, he never received a call to any sort of nonacademic position that seemed to fit the bill. He had the background and skills to be on the fast track to somewhere, but the question was to where.

Yet not all might is political—or military. Although a spent force among politicians, Henry Adams belonged without doubt to the cultural flowerings first in Massachusetts, and later in the District of Columbia. Since colonial times, Boston, “the City on a Hill,” had been regarded, or at least had postured itself, as “the Athens of America.” Cambridge, its neighbor across the Charles River, was, as still today, the home of Harvard University, where Adams was first an undergraduate and later a faculty member. Washington was and remains the governmental heart of the country. In Boston, Cambridge, the nation’s capital, and wherever else in the world he traveled in body or mind, Adams was fascinated by might in all its iterations, such as political, psychological, physical, and sexual. As his life sped by, he recognized that there was no point in angling for such strength. He could not wield power himself. Later, he accepted that he could in only the most marginal ways guide the movers and shakers who exerted it. He was never to be a puppetmaster. What was the solace, if any, for what may have initially been a deflating realization for him and his family? He understood that as a man of letters he was uniquely positioned and proficient in farsighted analysis and description of power and its operations. While his wife lived, their home attracted the chattering classes. After her death, even more than before, he staked most of his energies on the bet that he could make a mark through his writing.

Fig. 1.1 The Adams family tree, beginning with President John Adams (1735–1826).

Vector art by Melissa Tandysh, 2016. Image courtesy of Melissa Tandysh. All rights reserved.

On May 12, 1780, John Adams, who established the family franchise, posted a letter to his wife from Paris, where he found himself saddled with the responsibilities of both serving as an envoy and negotiating a peace treaty with Britain. In penning his missive to Abigail, her husband revealed that he had limited leisure to enjoy the beauty of France. Then, in oft-cited words, he displayed equal perspicacity about the present he inhabited and prescience about the future that lay before his progeny:

I must study Politicks and War that my sons may have liberty to study Mathematicks and Philosophy. My sons ought to study Mathematicks and Philosophy, Geography, natural History, Naval Architecture, navigation, Commerce and Agriculture, in order to give their Children a right to study Painting, Poetry, Musick, Architecture, Statuary, Tapestry and Porcelaine.

Fig. 1.2 Charles Francis Adams. Photograph by Matthew Brady, ca. 1860.

Washington, DC, National Portrait Gallery.

With a moratorium of one generation, John Adams’s descendants followed the blueprint that their forebear had drafted. They upheld his transgenerational curriculum.

For his great-grandson, study was indeed the most navigable route to success. As the proverb says, the pen is mightier than the sword. By putting into writing the results of his research and rumination, Henry Adams crowned the achievements of the dynasty. Beyond any other in his age cohort, he guaranteed through prolific publications in American history and journalism that his celebrated clan would exercise continued preeminence in the twentieth century. His profile grows only more daunting when we add to the picture two novels, his authorship of which he kept tightly under wraps during his lifetime. The final factor is autobiography: this label, despite being a blunderbuss, is still serviceable to affix to The Education of Henry Adams, published in 1907.

One component in the oeuvre of this man of letters, Mont Saint Michel and Chartres (1904), relates to Our Lady’s Tumbler. To be more precise, it recapitulates and quotes extensively in translation from the medieval French poem. Written late in Henry Adams’s life, the volume was unique. Likely to be considered cultural history nowadays, the investigation is peppered with meditations of heterogeneous sorts. His book, whatever name is used to categorize it generically, develops a far-reaching contrast that the author hypothesizes between the Middle Ages and his own times. By some measures, the comparison worked much to the advantage of the medieval period. In the argument, he effectively disowned the Founding Fathers, or at least he disclaimed the viability of their Enlightenment-driven outlook in his contemporary milieu of the dawning twentieth century. The friction between reasoned individualism and opposing intellectual movements remains unresolved, as we experience daily even today.

The Enlighteners had not been uniformly averse or antagonistic to the Middle Ages. Still, the United States had had in its earliest days no great exponent of relative openness to the period along the lines of, for instance, Jean-Baptiste de La Curne de Sainte-Palaye. The French historian, literary historian, and lexicographer nurtured no deep sympathy with medieval civilization and culture. All the same, he was less confrontational in voicing his reservations about the era than many of his compatriots were. The outlook that prevailed among these others would have verged closer to that of Voltaire, who ventured the viewpoint that even by the late fifteenth century, the Europe of the Middle Ages lolled irrecuperably in a mire of failings.

Through the successive steps of his family, Henry Adams had been acclimatized to an outlook that regarded faith itself as inherently naïve. In its place, he raised up something challengingly new and inconsistent: “the last and greatest deity of all, the Virgin.” As he envisaged Mary, she embodied the ideal or fantasy of eternal womanhood. By calling her what he did, he gave her autonomy equivalent to any person of the Trinity. She subsumed the spirituality of the Middle Ages as he chose to understand it, in his idiosyncratic adaptation of medieval Christianity. Yet at the same time, he desacralized her, and in the process, he managed to put his finger upon shortcomings in the modernity that was unsettling as it quickened around him.

Great Scott! Sir Walter

Will our posterity understand at least why he was once a luminary of the first magnitude, or wonder at their ancestors’ hallucination about a mere will-o’-the-wisp?

—Leslie Stephen,

“Sir Walter Scott” (1871)

The nineteenth century constituted a golden age for historical novels, especially ones grounded in the history of the Middle Ages, with Sir Walter Scott in Great Britain and Victor Hugo in France. Henry Adams’s private education as a youth imparted to him a command of Greek, Latin, and French, and an exposure to German. Less formally, his recreation enabled him to steep himself in the medieval period as evoked by the Scottish author’s historical novels. According to his report, the happiest and most educational stage in his childhood consisted in summertime hours that he passed “lying on a musty heap of Congressional Documents in the old farmhouse at Quincy, reading Quentin Durward, Ivanhoe, and The Talisman, and raiding the garden at intervals for peaches and pears.” The apposition is remarkable. The pile of records from the government in Washington mounted high enough to form a de facto sofa. What did the boy in the youngest generation of the political dynasty choose for pleasure reading as he stretched out atop the minutes of American democracy? Tales of the British Isles in the Middle Ages.

Adams says nothing at all about narrative poems by the Scottish writer, but the “Lay of the Last Minstrel” (1805) was also hugely influential (see Fig. 1.3). Gothicism was already deep-rooted by the time Scott laid down his pen. In his novel The Antiquary from 1816, the title character tags the people of the 1790s as a “Gothic generation.” Yet by the end of Scott’s life, Gothicism was rampant beyond the wildest fevered dreams of those men. The oeuvre of the antiquarian author forms the substructure of the historical or historicist novel in English literature, and the foundation is medieval. The tremendous popularity of his writings, taken together, can be overlooked easily. Today, his prose and, even more, his poems are scarcely read. Even the early twentieth-century films based on his fictions are largely unknown. But throughout most of the nineteenth century, his corpus was devoured indiscriminately by cultured Americans. This circumstance held especially true for those from Henry Adams’s respectable thoroughbred social set. Scott’s influence, it has been written, was so pervasive that in consequence of it, “at the Harvard commencement a boy might mount a mechanical horse and tilt at a ring.” In other words, the Scottish writer may have had a share in the nineteenth-century fairground phenomenon of the carousel, which in those days enabled passengers to take a joyride on carved horses while clutching a miniature lance with which to spear a brass ring. The chivalric origins of this contraption remain only vestigially today, in the equestrianism of riding in wooden circles. The soldierly aspect has been repressed through the disappearance of weapons and targets: the circular course has been demilitarized. Yet the jousting that once took place there lingers on, encoded in language. The historical sense of this word for a merry-go-round denotes a tournament in which knights astraddle steeds compete in demonstrating their skills.

In the nineteenth century, no one escaped Scott-free. The writer published only one work explicitly for children: Tales of a Grandfather, in 1827–1830. Even so, his books were consumed equally by the younger set and adults. The picture of the Middle Ages presented by the novelist contributed in no small part to the entrenchment of the period in the worldview of English speakers. The idiosyncratic, pseudomedieval language that he concocted for his historical fiction was the form of Scott-ish most widely known in the nineteenth century. It could even be argued that during the Victorian age more people formed their impressions of the Middle Ages from perusing his fiction than from immersing themselves in actual medieval texts, let alone in architectural or archaeological evidence.

Fig. 1.3 Front cover of Walter Scott, The Lay of the Last Minstrel, illus. Birket Foster and

John Gilbert (Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black, 1854).

Adams gives us a glimpse of America being medievalized. Thus, he shows us himself as a boy, on a bucolic farm in Massachusetts. The mind of this younger self is stocked with medieval personages and places as transmitted through the imaginings of an early nineteenth-century British novelist. The influence of Scott’s books penetrated throughout the United States, infiltrating not only literature but also architecture and more, just as it did throughout Great Britain and the British Commonwealth. Consequently, Adams was far from the only American to have been influenced by the novels. His close friend John Hay, in an address delivered in 1897 to mark the unveiling of Scott’s bust in Westminster Abbey, pointed out that “the romances of courts and castles were specially appreciated in the woods and prairies of the frontier.”

The Scot’s Gothicist predecessors, notably Horace Walpole and William Beckford, disseminated in their writings and architecture a taste for medievalesque horror and fantasy that reached back to Matthew “Monk” Lewis. Though Scott took the medievalesque novel away from such associations with stomach-turning fright, his output only annealed the links between Gothic literature and architecture, including landscape architecture. In no genre have the two arts interacted more robustly than in Gothic. The English nobleman Walpole (see Fig. 1.4) was known for having propelled this style of literature through his medievalesque The Castle of Otranto and for having achieved a similar effect in architecture and landscape architecture through Strawberry Hill (see Fig. 1.5). From within this remarkable pseudo-Gothic mansion, the author and architect published most of his writings.

Fig. 1.4 John Giles Eccardt, Portrait of Horace Walpole, 1754. Oil on canvas, 39.4 × 31.8 cm. London, National Portrait Gallery, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Horace_Walpole_by_John_Giles_Eccardt.jpg

Fig. 1.5 Strawberry Hill, Horace Walpole’s Gothic Revival villa in Twickenham, London. Photograph, 2012, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Strawberry_Hill_House_from_garden_in_2012_after_restoration.jpg, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Beckford composed the Gothic novel Vathek and built as his Gothic revival country house the now-lost Fonthill Abbey (see Fig. 1.6), just as out of the ordinary as Walpole’s estate. Then there is Scott himself. In addition to all he wrote, he rebuilt his residence at Abbotsford (see Fig. 1.7) in medievalesque style. His idea was that the antiquarianism of its solid castellation could affirm his place in the still largely feudal society of Scotland. By the same token, he expected his guests there also to visit the nearby Melrose Abbey (see Fig. 1.8).

Taking matters in a very different direction, Scott nudged Gothic instead toward historicizing realism or romance in depicting what purported to be medieval people, deeds, and life. In Abbotsford, the novelist nestled among objects and artifacts that made the Middle Ages present to him in material reality, just as ballads brought the period home to him literarily. Such pseudorealism, in an embryonic form, is the thrust of the preface that Walpole attached to the second edition of The Castle of Otranto, which became foundational to Gothic literature. Still, much of that genre is devoid of the nostalgia for that time that Walpole evidenced.

Such was the perceived realism of the fictions that Ivanhoe contributed to the inspiration for the famously high-budget Eglinton Tournament of 1839. This mass spectacle was the primogenitor, especially in the English-speaking world, from which originated many large-scale reenactments of medieval events down to the present day. The granddaddy of “Medieval Times”™ and the Society for Creative Anachronism, it pioneered re-creational medievalism, long before such activities had been devised or such a name had been coined to designate them. Organized and underwritten by the Earl of Eglinton, the happening drew an audience of 100,000 that counted many peers. Inclement weather rained out the first two days. The conjunction of heavyweight armor and flash-flood downpours caused serious attrition, as the phalanx of reenactors playing knights dwindled. Despite such adversities, the extravagant costumes and pageantry stamped a lasting mark on popular imagination. So too did the cost overruns.

The excesses of the tournament were far from the first manifestation of Scott-inspired dress-up. In 1823, a ball that stipulated that guests come outfitted à la Ivanhoe had been held already in Brussels. Outside the subculture of staunch historical re-creators, even in the first half of the twentieth century the novels still projected an afterglow of influence upon the mega donors of the day in the United States. Propelled in part by exposure to Scott’s fictions, the masters of the universe J. P. Morgan and John D. Rockefeller Jr. bequeathed their medieval collections to museums and footed the bill for authenticating colleges as colleges by building them in Gothic.

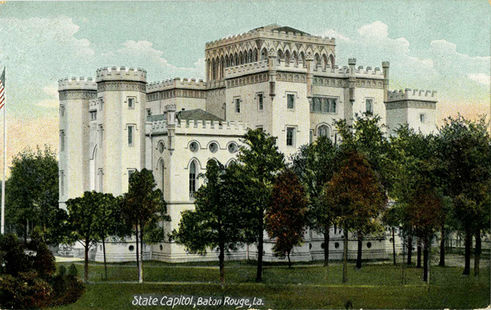

For the most part, the man who plied his pen under the pseudonym Mark Twain was as un-Adamsian in his background and outlook as a fellow American could have been. All the same, in an essay entitled “Castles and Culture,” Samuel Langhorne Clemens recognized as clearly as had Adams the all-pervasiveness of Scott’s reach. The Missourian author first excoriated and then shrugged off the obsession of his countrymen with the Middle Ages as “The Sir Walter Disease.” Not immune to the ailment himself, Twain would later produce two entire novels in which he explored the medieval period, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court in 1889 and Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc, by the Sieur Louis de Conte in 1896. The microbe of the medievalizing affliction infected not just literature, but architecture too. As we have seen and will continue to see, the two arts, far from strange bedfellows, have often been allied in Gothic revivals. When discussing the Old Louisiana State Capitol in Baton Rouge (see Fig. 1.9), Twain seized the occasion to dismember and deride cleverly and critically the permeation, retardation, and deformation of southern culture by the historical novels. He pronounced: “It is not conceivable that this little sham castle would have been built if he had not run the people mad, a couple of generations ago, with his mediæval romances,” concluding: “The South has not yet recovered from the debilitating effects of his books.”

Fig. 1.6 Fonthill Abbey, the massive Gothic Revival country house built for William Thomas Beckford, dismantled in 1845. View of the west and north fronts. Illustration by John Rutter, 1823. Published in John Rutter, Delineations of Fonthill and its Abbey (London: Shaftesbury, 1823), plate 11, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fonthill_-_plate_11.jpg

Fig. 1.7 Abbotsford House, Sir Walter Scott’s medievalizing manor in the Scottish Borders. Photograph, 2008, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Abbotsford_Aug2009_01.jpg,

CC BY-SA 3.0.

Fig. 1.8 Melrose Abbey, a ruined Cistercian monastery in Roxburghshire.

Engraving by Thomas Allom and Robert Wallis, 1836.

The quip of the matchless American humorist calls out for modification mainly in that second sentence. As it turns out, the former Confederate states were far from alone in succumbing to the impulse to Gothicize such buildings. To take a particularly germane example, the Connecticut State Capitol was built between 1871 and 1878 in Hartford (see Fig. 1.10). Its hallmarks are its style, Victorian Gothic, and material, coolly (and monotonously?) glistening white marble. The architect Richard M. Upjohn won the commission over competitors who included the great Henry Hobson Richardson. Twain himself lived in the same city for two decades from 1871. Still closer to home, in fact all the way there, is the twenty-five-room house the novelist had built for his family. The structure was constructed in an idiosyncratic reflex of the High Victorian articulation of Gothic revival architecture, with vibrant colors (see Fig. 1.11). In the same chapter of his memoir Life on the Mississippi, Twain pays particular attention to what he calls the “Female Institute” in Columbia, Tennessee (see Fig. 1.12). He first cites a hard sell that touts the castle-like appearance of the ivy-covered towers and turreted walls, and then launches into editorializing about the drawbacks of the intramural community that is fostered within:

Keeping school in a castle is a romantic thing; as romantic as keeping hotel in a castle. By itself the imitation castle is doubtless harmless, and well enough; but as a symbol and breeder and sustainer of maudlin Middle-Age romanticism here in the greatest and worthiest of all the centuries the world has seen, it is necessarily a hurtful thing and a mistake.

The writer from Missouri implies that the medieval period may seem to be a mere placebo, when it is instead moldering and mildewed. Yet his perspective is only part of the picture. A broader lesson to be drawn may be that in the nineteenth century, even in the flinty newness of the New World and the United States of America, there was no escaping the Middle Ages—or at least not medievalism.

For all his customarily calm, cool, and collected sanity, Adams was struck as forcibly by encounters with the medieval past, both directly and indirectly, as were many of his contemporaries in both England and America. Walter Scott stayed with him indelibly in his imagination. In a letter from 1911, the historian drew a comparison between Shakespeare and the novelist that inclined much to the favor of the second. Adams declared categorically “Ivanhoe is an enormous work of instinctive comprehension and genius.” In another letter from 1913, he described his immersion in twelfth-century songs, and uttered the longing “I wish Walter Scott were alive to share them with me.”

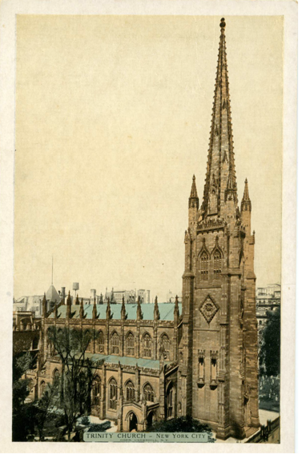

Thanks to Romanesque and Gothic revival buildings, a stunning number of Adam’s engagements with the Middle Ages took place in the United States itself. Many pseudomedieval architectural remains that stood proudly during his lifetime have since been effaced in favor of a colonial vision in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and a classicizing one in the nation’s capital. It can be dumbfounding to discover what has been utterly erased or partially palimpsested in the recurrent destruction and re-creation of spaces, structures, and styles that take place routinely in American urbanism.

Fig. 1.9 Postcard depicting the Louisana State Capitol, Baton Rouge, LA

(Portland, ME: Hugh C. Leighton Co., early twentieth century).

Fig. 1.10 Postcard depicting the Connecticut State Capitol, Hartford, CT

(New York: Union News Company, early twentieth century).

Fig. 1.11 The Mark Twain House, Hartford, CT. Photograph by Wikimedia user Makemake, 2005, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:House_of_Mark_Twain.jpg, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Fig. 1.12 Postcard depicting the Columbia Institute, Columbia, TN

(Chicago: Curt Teich & Company, 1919).

Gothic Harvard

In my sublimated fancy the combination of the glass and the Gothic is the highest ideal ever yet reached by men.

The stretch between Adams’s college years and his resignation from the Harvard professorship corresponded to the second height of public palaver about the Gothic mania after romanticism. The heart of his tenure at the university saw the publication in 1873 of a novel entitled The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today. In it, Mark Twain, who was co-author along with his friend Charles Dudley Warner (Fig. 1.13), labeled his times the “Gilded Age.” Adams, the not-so-public intellectual and outward-looking introvert, was fully aware of the rapier-witted Twain. Likewise, he was hypersensitive to all the fatal flaws of the historical period in which both he and his fellow wordsmith lived. The two took nostalgic turns toward the Middle Ages, away from what they regarded as the specious shimmer of affluence and glamor, the tenuous gilding, that masked the tempestuous and tumultuous world in which they dwelled. This is not to imply that Adams may have fallen in any sense under Twain’s sway. What they share suggests “concurrence rather than coincidence,” and their outlooks diverge forcefully in many regards. In fact, the two men differed starkly. Rudyard Kipling’s oft-quoted observation that “East is East and West is West” applies in full to the relationship between the two Americans: “never the twain shall meet.” (See Fig. 11.14.)

The same phase in the 1870s that got the Gilded Age underway also saw architecture in the Gothic style crest as an idiom within Harvard Yard and in its immediate vicinity. During this period, the university attained worldwide prominence in the academic pursuit of the Middle Ages, with leading appointments in history, English, Romance languages, and Latin, to identify only a few key disciplines. Medievalesque architecture came hand in hand with medieval studies and a commensurate appreciation for the intellectual importance of the Middle Ages in the formation of Western languages and cultures.

Fig. 1.13 Mark Twain (left) and Charles Dudley Warner (right) during their collaboration on The Gilded Age in their studio in Elmira, NY. Engraving by William Harry Warren Bicknell, ca. 1899. Published in Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner, The Gilded Age, Mark Twain Complete Works Uniform Edition, ed. Francis Bliss, vol. 10 (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1899), frontispiece.

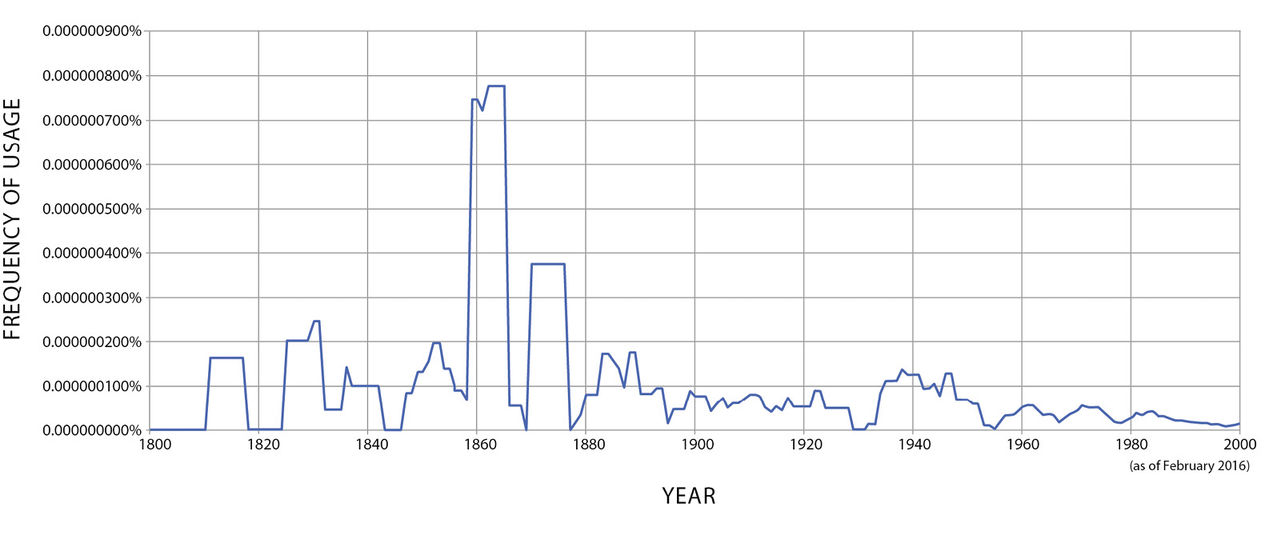

Fig. 1.14 Google Books Ngram data for “Gothic mania,” showing a pronounced spike in the 1860s. Vector art by Melissa Tandysh, 2016. Image courtesy of Melissa Tandysh. All rights reserved.

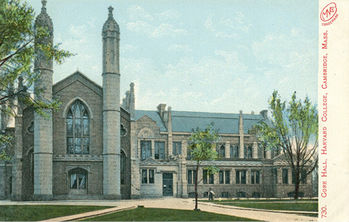

Those of us who are not degree-bearing architectural historians have remained justifiably ignorant of what could be called “Gothic Harvard” for the simple reason that from the second decade of the twentieth century, the university was systematically de-Gothicized. Abbott Lawrence Lowell, who headed the institution from 1909 to 1933, purged the institution of Gothic in favor of Georgian revival architecture. During his undergraduate studies, Adams would have logged many hours in the university library—at that time, Gore Hall, purpose-built of granite between 1837 and 1841, expanded in 1876, and demolished in 1913 to make way for the present hulking edifice (see Figs. 1.15 and 1.16). Gore Hall was termed by the novelist Henry James “a diminished copy of the chapel of King’s College, at the greater Cambridge.” While still standing, it made a deep impression on many viewers. The stone simulacrum belonged to a process of drawing analogies to Old Europe. Such constructions helped to familiarize the unfamiliar—to Europeanize the United States. In the process, they gave an American expression to the wedding of the picturesque and the Gothic that has featured in such revivals since the eighteenth century.

Fig. 1.15 Gore Hall, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. Photograph, ca. 1905. Photographer unknown. Washington, DC, Library of Congress, Prints and

Photographs Division.

Fig. 1.16 Postcard depicting Gore Hall, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (New York: Metropolitan News Co., early twentieth century).

In 1846, Edward Everett, president of Harvard, designed for Cambridge, Massachusetts, the city seal and its accompanying Latin motto. Although the emblem has been overhauled slightly since its adoption, it has not been superseded despite the disappearance of the library and the tree pictured to the left of it. That growth, formerly located at the northern end of the public park known as Cambridge Common, is the so-called Washington Elm. Legend held that under this woody overhang the future head of state by this name took command of the army during the American Revolution (see Fig. 1.17). Thus, the design juxtaposes tokens of both the founding days of the United States and what was (however strange it may sound) the height of modernity, the Gothic revival.

The relevance of Gore to civic as opposed to college identity would have been unimaginably greater than now; the Yard was not yet walled off from the circumambient community. The process that led to the demolition of Gothic structures within the heart of the campus coincided with a palpably physical assertion of a town-gown divide and a radical transformation of the relationship between buildings and landscape. The college precincts most affected became truly gated communities. Many such changes took place after the undergraduate career of Henry Adams.

Fig. 1.17 The seal of Cambridge, Massachusetts, featuring both the Washington Elm and Gore Hall. The top half of the Latin motto translates to “Distinguished for Classical Learning and

New Institutions” or “for Classical Learning, Newly Undertaken.”

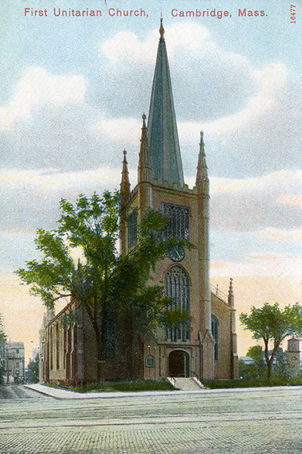

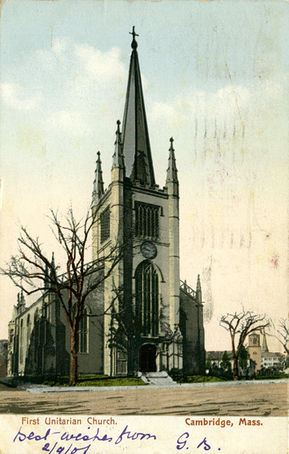

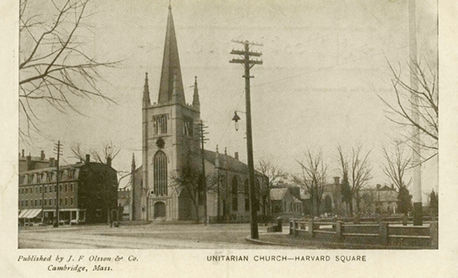

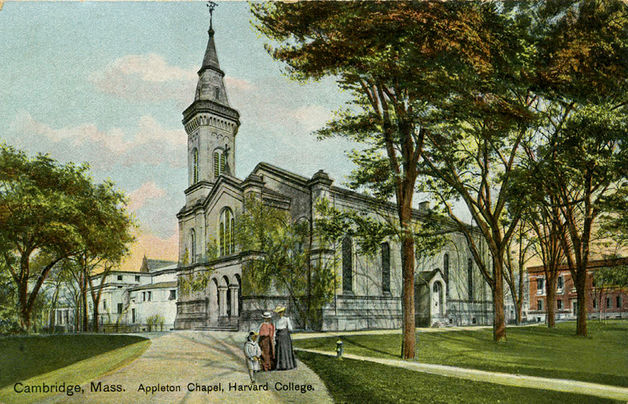

When his senior year concluded in 1858 (see Fig. 1.18), Adams would have been awarded his bachelor of arts degree in a house of worship now called the First Parish Church (see Fig. 1.19). Harvard College presidents were inaugurated within it, and commencement ceremonies were held there until the 1870s. Despite the several lancet windows, the plainness today may cozen a casual viewer into assuming, quite wrongly, that the structure is in the Colonial style (see Figs. 1.20 and 1.21). On the contrary, it was then in an elaborately bedizened Carpenter Gothic (see Fig. 1.22). Only after being buffeted savagely by a thunderstorm in the early twentieth century was the building cropped of its curlicues and simplified (see Fig. 1.23). In the year of Adams’s graduation, the university built to replace it on Harvard property a monstrosity that amalgamated classical and Romanesque elements. The bizarrely eclectic Appleton Chapel stood on its own grounds for seventy-five years, until 1932 (see Fig. 1.24).

Fig. 1.18 Henry Brooks Adams. Photograph by George Kendall Warren, 1858. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University, Fogg Museum, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Henry_Brooks_Adams,_Harvard_graduation_photo.jpg

Fig. 1.19 First Parish Church, Cambridge, MA, as seen through Harvard’s Johnston Gate. Photograph, 1900–1920. Detroit, MI, Detroit Publishing Company. Washington, DC,

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Fig. 1.20 First Parish Church, Cambridge, MA. Photograph by Peter Alfred Hess, 2011, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:First_Parish_in_Cambridge_(2011).jpg, CC BY 2.0.

Fig. 1.21 Postcard depicting First

Unitarian Church, Cambridge, MA

(Boston: Reichner Bros., ca. 1906).

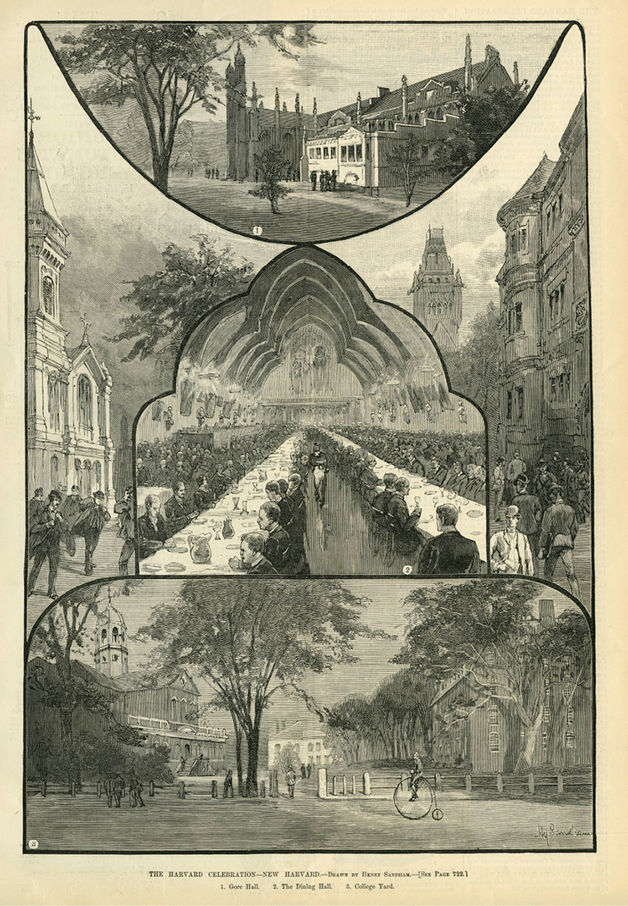

In 1886 the university marked its 250th anniversary. In that year, an engraving in Harper’s Weekly feted “The Harvard Celebration: New Harvard.” (See Fig. 1.25.) The top semicircle features Gore Hall. Below, a curvy box accommodates the Gothic rafters of the dining space in Memorial Hall. It is flanked on the left by the Classical-Romanesque fusion of Appleton Chapel, and on the right by the Victorian Gothic tower of Memorial Hall. To complement the supposed modernity—a largely medievalesque one—three key old buildings are represented, in the form of Harvard Hall, University Hall, and Massachusetts Hall. The foreground depicts a pacemaker of the day as he pedals a high-wheeled bicycle.

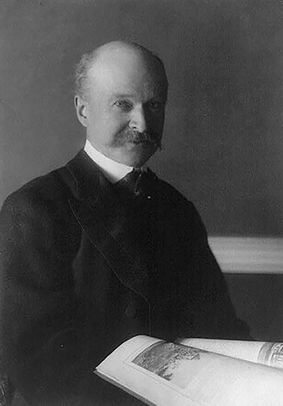

Medieval was modern. Young Goths at Harvard University had encouragement for their medievalism not only from architecture but also from teachers. As a student, Adams attended lectures on Dante by James Russell Lowell (see Fig. 1.26), a poet who had succeeded none other than Henry Wadsworth Longfellow as Smith Professor of Modern Languages in 1856. Lowell stepped down from his named chair in 1874, by which point he was firmly established as a standard-bearer in American culture (see Fig. 1.27). After giving up his tenure, he continued to teach until 1877—the same year in which Adams himself resigned.

Fig. 1.22 Postcard depicting First Unitarian Church with original Gothic spires, Cambridge, MA (Boston: The New England News Company, ca. 1906).

Fig. 1.23 Postcard depicting First Unitarian Church with original Gothic spires, Cambridge, MA (Cambridge, MA: J. F. Olsson, early twentieth century).

Fig. 1.24 Postcard depicting Appleton Chapel, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA

(Portland, ME: Hugh C. Leighton Co., ca. 1910).

Lowell came by his medievalism naturally. His father had thought of christening his youngest son Perceval, and the professor-to-be himself later considered altering his name to this same chivalric one. In Arthurian legend, this knight belonged to the paladins of the Round Table. In early versions of the quest for the Grail, he was the hero, later displaced by Galahad. Not coincidentally, Lowell’s first poem to achieve modest popular success was The Vision of Sir Launfal, a tale about the court of King Arthur that was first printed in 1848. The poet emphasized that the Middle Ages was an age of faith, and that the Gothic arch expressed faith and aspiration for heaven. Whether instruction of this sort would have predisposed students such as Adams to favor Gore Hall and the First Parish Church is not at all certain. After all, Lowell also satirized a craftsman who fabricated a humble residence in Carpenter Gothic. But in lecturing, the professor prevailed in promoting among his students a predilection for the original Gothic style. In The Education of Henry Adams, the author credits his former teacher with having inspired him to treasure the medieval character of preindustrial Germany.

Fig. 1.25 “The Harvard Celebration – New Harvard.” Gore Hall, Annenberg Dining Hall, and Harvard Yard. Engravings by Henry Sandham, 1886. Published in Harper’s Weekly (November 6, 1886), 721.

Fig. 1.26 James Russell Lowell. Head-and-shoulders portrait. Engraving by J. A. J. Wilcox, from original crayon in possession of Charles Eliot Norton, drawn by S. W. Rowse in 1855. Washington, DC, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Fig. 1.27 Postcard depicting “Elmwood,” the home of James Russell Lowell in Cambridge, MA (Cambridge, MA: Tichnor Bros., ca. 1930s).

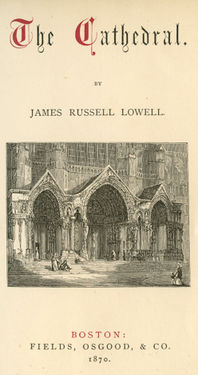

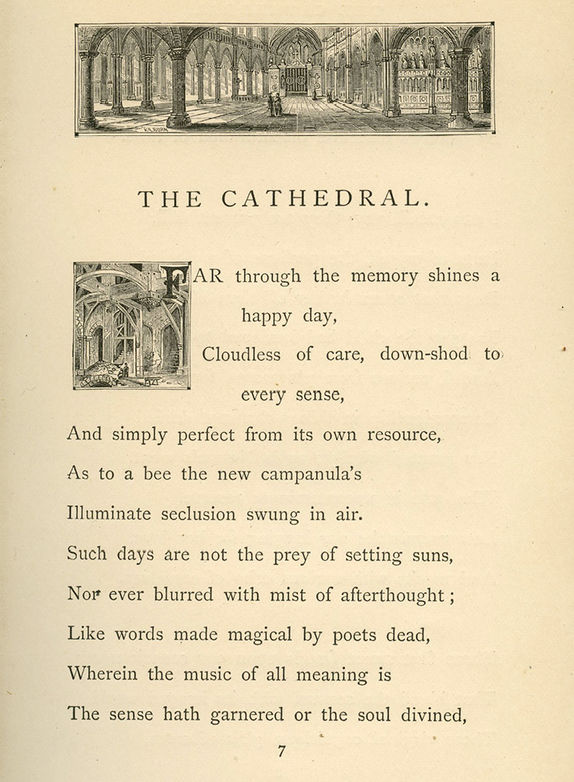

During one stretch in the fall of 1869, Lowell directed his energies to composing a long poem, having been foiled in his expectation to be appointed minister to Spain. “The Cathedral,” which the poet may have intended originally to entitle “A Day at Chartres,” was inspired by an excursion he had made to the French town fourteen years earlier. This soaring Gothic work was published in 1870 (see Fig. 1.28). That year, in which Adams first returned to Harvard to join the faculty, coincided with the Franco-Prussian War. The freshly minted professor does not mention the literary masterpiece but would unquestionably have known it. However odd and unlooked-for the pairing of the French church and the Ivy League university may appear today, at the time the two made a natural couple. “The Cathedral” was published conjointly with the so-called Harvard Commemoration Ode in 1877 (see Fig. 1.29). Counted among Lowell’s finest pieces of public poetry, the composition was written within a few months after the end of the Civil War and the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. From our vantage, the diptych of poems may seem implausible candidates for popularity on a scale that would warrant mass production in a petite pocketbook format, but the two pieces captured the spirit of the United States at this juncture. The country looked eastward to Europe and backward to the Middle Ages, as imagined points of solidity and solace. At the same time, the nation could not help but survey the melancholy madness of the self-inflicted internecine butchery from which it had only just emerged.

The impact of “The Cathedral” on Adams’s contemporaries can be judged from an episode in the life of Charles F. McKim (see Fig. 1.30). Most arrestingly in his contributions to the Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, this architect epitomized neoclassicism as a stark alternative to Gothic revival. Yet he too had his moments as a Goth. Younger than Adams by roughly a decade, the building designer had matriculated at Harvard University in 1866, but left it for the School of Fine Arts in France. While studying in Paris, he and fellow students once sallied forth on a pilgrimage of sorts to Chartres. After climbing one tower of the great church, they recited Lowell’s recently published “The Cathedral,” which was deemed sufficiently powerful and original to warrant such homage. It gave influential voice to a contrast between the Middle Ages and modernity that awarded the clear edge to the medieval period: “This is no age to get cathedrals built.”

The title page of Lowell’s flight of Gothic fancy bears the name of the poem in pseudomedieval lettering. The initial and the publication place of Boston are rubricated. The side of paper also features a representation of the three portals of a Gothic place of worship. The engravings to accompany the opening lines of the poem proper blandish the reader to tiptoe further within the house of worship, into a phantasmagoria of arches (see Fig. 1.31). The poet characterized himself as “a happy Goth,” and the cathedral of Chartres itself as “imagination’s very self in stone.” Adams was more of a saturnine Goth, for reasons related to his temperament, the ups and downs of his life, and his take on his times, but he may well have shared various of Lowell’s perspectives on the magnificence of the French architectural gem, including the one just quoted. Both make this great church their Rosetta Stone for decoding medieval culture.

Fig. 1.28 Title page of James Russell Lowell,

The Cathedral (Boston: Fields, Osgood, 1870).

Fig. 1.29 Front cover of James Russell Lowell, The Cathedral and the Harvard Commemoration Ode, Vest-Pocket Series of Standard and Popular Classics (Boston: James R. Osgood, 1877).

Fig. 1.30 Charles Follen McKim. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston, ca. 1880–1909. Washington, DC, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

In a letter to Henry James sent from Paris in 1903, Adams unburdens himself. He expresses the belief that the entire clubby cadre of New Englanders, or rather of Bostonians of which he formed part, “were in actual fact only one mind and nature: the individual was a facet of Boston.” To bring home his point about the tribalism of his group, rare and dying breed that it was, he gives a list, in which he includes Lowell and Longfellow. His clannish segment of the Boston upper class was known traditionally as Brahmins. Whatever inbred gentility he had in common with these aristocrats, the Middle Ages were not writ large in his background. Besides, the historical era differed from the one that took shape in his own fertile mind. While in college, the historian-to-be would have had some contact with medieval literature and history, but nothing indicates that his exposure did more than scratch the surface or that it had much impact on him. He sensed all too well that his set of New England political and cultural leaders was losing, if it had not already relinquished, the predominance it had exercised until his time. For all their clubbability, they underwent retrenchment that reduced them to figureheads. The Yankee crucible in which he had been fashioned was imperiled.

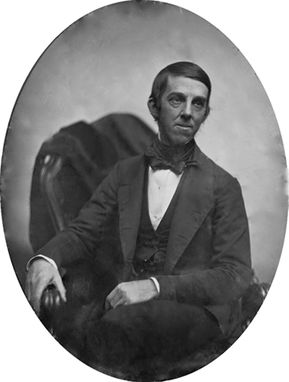

In 1858, Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. (see Fig. 1.32) coined “hub of the solar system” to describe the Massachusetts State House. The last two words in the phrase were soon reformulated more brashly and boastfully by others as “the universe.” The revised phrase became a byword for Boston as an entirety. Yet within a decade, the circumstances that enabled the city to posture itself as central inside the nation, world, and cosmos changed. Civil War and slavery ended, industrialization boomed, finance took steadily deeper root in New York City, expansion accelerated outward into the West, immigration looped in a helix upward, and measureless economic growth began, along with equally immense inequality. All these trends prevailed as Henry Adams came of age—not that he was present in the United States to witness the drama firsthand.

After graduating in the year in which Boston became the hub, Adams traveled in Europe until 1860. There he spent most of his time in Berlin and elsewhere in Germany. Intellectually, he was affected by German education and learning just as powerfully as Gaston Paris was, who studied there shortly before him. The American historian acquired no degree during his sojourn there, but like the French philologist, skills aplenty in textual criticism, exposure to the seminar system (which he helped to introduce into graduate studies at Harvard), and, perhaps most importantly, a faith in historical scholarship as a science based on documents and archives.

Mont Saint Michel and Chartres was first printed in 1904, when Adams was sixty-six years old—one year after the death of Gaston Paris. The rigor apparent in the book is not the exhaustiveness of scholarship that had been imported into American intellectual life from Germany. The pages in Adams’s volume contain nothing scientific in the sense of the German Wissenschaft, which translates literally as “science” but denotes more broadly “systematic research and knowledge.” On the contrary, while searchingly intellectual and meticulously organized, the work qualifies as deeply personal and even idiosyncratic. As such, it forms an eloquent testimonial to a man whose life has been described aptly as “a search for that education the schools could not give.”

Adams may have mischaracterized Mont Saint Michel and Chartres with more than a grain of exaggeration when he called it “a historical romance of the year 1200,” rightly dissociating it from conventional narrative history. The book meditates upon the past. Yet it is simultaneously marinated in its own present day. In addition, it does not shy from far-seeing forecasts about the future. Beyond the Middle Ages, Adams theorizes that in all realms, but especially in art and religion, creative energy dissipates and civilization decays. He allows for no breezy best-case scenario.

If in his texts on American history Adams wrestles with an anxiety of influence, his greatest preoccupation may well be the model embedded in The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by Edward Gibbon. In Mont Saint Michel and Chartres, Adams at once extends and alters the English historian’s argument about an erosion of civic virtue. He argues for continuity between the fertility idols of prehistoric and primitive peoples on the one hand and the art of the Middle Ages on the other. Once again, primitivism and medievalism are equated. The same equation was being drawn in art in the United States, thanks to collectors and connoisseurs such as Thomas Jefferson Bryan, whose collection included a Madonna and Child with Saints. In a novelette based in part on him, the writer Edith Wharton extols his assemblage as “one of the most beautiful collections of Italian primitives in the world.”

The paradoxical qualities of Mont Saint Michel and Chartres may help us appreciate why Adams treated this creation of his like a beloved bastard child. They may be the reason why this book has been read far more than his other writings (excepting his autobiography). These features may also clarify why it has been spared the cakes of grime that dusty disuse has since deposited upon measureless masses of other less successful old tomes about the Middle Ages from Adams’s day, such as the once-esteemed The Medieval Mind (1911) by his medievalist colleague and former student at Harvard, the historian and legal scholar Henry Osborn Taylor (see Fig. 1.33).

The great compass and the exceptional (or exceptionalist?) character of Mont Saint Michel and Chartres are intrinsically and perhaps exclusively American. The study has never been translated into any other language than French. If from one vantage point the author deserves to be certified as a citizen of the world, from another he is archetypally and patriotically a national of the United States. Henry James wrote the novels and talked the talk, but the other Henry—Adams—lived the life and walked the walk. He remained at his core a Bostonian and an American, no matter how far afield he roved, and no matter how widely his mind ranged.

Fig. 1.31 James Russell Lowell, The Cathedral (Boston: Fields, Osgood, 1870), 7.

Fig. 1.32 Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. Photograph by Josiah Johnson Hawes, ca. 1850–1856. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Library, Weissman Preservation Center, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Oliver_Wendell_Holmes_Sr_daguerreotype.jpeg

Fig. 1.33 Henry Osborn Taylor. Photograph, before 1941. Photographer unknown. New York, Columbia University Archives, Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Image courtesy of Columbia University Archives, New York. All rights reserved.

Photographic Memory

Henry Adams did not have to be dragged kicking and screaming into the 1900s. On the contrary, he showed himself open to many innovations that the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries brought. Photography was one of them. The cathedrals, in their picturesqueness, have been camera-ready since long before the devices were invented, yet once available, the manners changed in which these churches were seen, studied, and understood. The study of the Middle Ages has never obligated professionals devoted to them to forswear the most modern gadgets or approaches. In fact, the opposite has held true from the beginning of medieval studies as a formal area of learned investigation. In the late nineteenth century, medievalists, like classicists, embraced cutting-edge research techniques. Editorial principles were only one of the newest widgets at their disposal. Beyond words, Adams’s book pivots decisively into the age of durable images on light-sensitive materials. In what is now the standard edition, the first page of the preface makes mention of a Kodak. Mont Saint Michel and Chartres methodically exploited the potential for the comparison of buildings in hard-to-reach locations that pictures made with photographic equipment accorded. By the same token, it gives signs that its author was transformed by the innovative ways of looking that arrived with the new technology.

In swiveling intellectually in this direction, Adams had the advantage of acclaimed predecessors among the originators of art history as a formal discipline. John Ruskin gave a definitive mission statement for the incorporation of photography within scholarship. To do him justice, he issued repeated, often mutually contradictory pronouncements on the topic. In one passage that began by establishing a generic hierarchy of Gothic, he ended up elevating Notre-Dame of Paris above all other expressions of the style—and promptly called for image-based analysis to hone such observations. Consistent with this proclamation, he relied upon daguerreotypes in his research. Similarly, William Morris progressed in his own interests in photos by way of lantern slides and facsimiles. In due course, the great man wrote glowingly of the architecture in Amiens cathedral, in an article composed with the aid of snapshots.

Henry Adams had learned to take photographs already in the spring of 1872, in preparation for the journeys he and his wife would make on their extended honeymoon. But it took a while, for reasons of both expense and convention, for the practice to percolate into his scholarship. For example, Lowell’s 1870 poem was accompanied by engravings and not photos. The two original private printings of Mont Saint Michel and Chartres are devoid of illustrations, apart from diagrams. In contrast, the 1913 reprint of the book that was overseen by Ralph Adams Cram exhibits mostly pictures cherry-picked for their utility in bringing home aspects of Gothic architecture. These images fulfill a documentary function. They are supposed to be direct records, without any intervention—no airbrushing.

Even in the private printings, many pages are studded with references that manifest the degree to which photos had displaced freehand drawings as a means of establishing a supposedly cold-eyed, firsthand, and experiential record of sights seen. Because of intimate circumstances in his life, Adams had good basis to be gruff about the art. Beyond the personal, he had intellectual objections. In fact, he developed what he called “photo-phobia” in reaction to what he regarded as inherent limitations and distortions in the medium, particularly as opposed to painting. Yet this stance of resistance did not keep him from exploiting the form for his own purposes, and even less to hamstringing others from doing so. For all his protestations, he was uniquely photocentric when compared with investigators from preceding generations.

In the nineteenth century, the discipline of historiography was fine-tuned as the numbers and stature of its practitioners burgeoned. In the refinement, archival research played an outsized role. As much as anyone, Adams perceived that personal archives of photographs had a one-of-a-kind value for facilitating recollection and evaluation as well as for helping in the hide-and-seek of historical investigation. Earlier in the nineteenth century, the spreading use of plaster casts had begun to familiarize historians of art and architecture with the utility of working from copies, initially for the needs of instruction. Similarly, the proliferation of cameras and their products accustomed scholars to the advantages of such surrogates for the purposes of comparison and the study of evolution. These inquirers developed and perfected their own kind of photosynthesis.

Adams casts Mont Saint Michel and Chartres guilefully as the travelogue of an imagined itinerary to Gothic sites. He makes his trip in the company of an unnamed “niece.” This is his term for one of the companionable younger women who frequented him. Although many were in fact blood relations, others were not. To draw upon an old expression, they were kith and kin. In his pseudoavuncular stance, he assumes that such a purported relative will accompany him on his tour. Apart from a female escort, what is the womanly equivalent to a man who squires around a woman? Without fail, the niece is meant to carry a camera “and take interest in it, since she has nothing else, except her uncle, to interest her, and instances occur when she takes interest neither in the uncle nor in the journey.” In this gentle barb about the preference of his female companion for photographic hardware over all else, Adams may even intend a subtle contrast between women in the Middle Ages and in modernity. Photography supplies the acid test, by opposing the Virgin Mary and her resplendent stained glass to the supposed daughter of his sibling and the lens of her picture-taking rig.

In Mont Saint Michel and Chartres, the author takes portable machines with roll-film so much for granted that he twice employs “kodak” uncapitalized as a generic term. The germ of this device was patented in 1881. Already by the 1890s, its convenience had changed the world every bit as much as cellphone cameras have in this century. Adams also brings home how photos have supplanted engravings as a medium of scholarly record. Personal accumulations and formal archives of photographs, including printed books with reproductions that individuals and libraries could acquire, in turn became essential tools for pursuing certain avenues of investigation, such as art and architectural history. Assembling holdings of pictures was immeasurably more practical for individuals, since collections of original objects were costly even for wealthy institutions. Researchers could readily secure all the facts, not just verbal but visual too.

In his work, Adams pushed ahead with his own amassing of images. He was driven by the belief that “photographs such as those of the Monuments Historiques answer all the just purposes of underground travel.” Furthermore, comparison of such pictures had won recognition as a discovery process. Potential readers of Adams’s Mont Saint Michel and Chartres, in their guise as tourists who would visit the actual cathedrals he discusses, were expected to make the juxtaposition of images and realities a heuristic technique. By the end, he recommends having in hand photos and books of architectural history when touring Gothic cathedrals. Ultimately, systematic archives gained, in Adams’s eyes as well as in others’, a special cachet for the cognition and remembrance that they enabled.

In writing to his intimate friend Elizabeth Cameron, Adams commented on the quantity of photographs and on the eye-watering price tag for acquiring them that his personal collecting entailed. These efforts came above and beyond those called for to consult pictures compiled in conjunction with specific projects of other scholars and institutions. Over the past half century, hitherto-untapped resources made widely available through computing have shaken up the process of research and the provision of access to its results. So too in the corresponding decades of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a similar revolution caused radical transformations in the workings of scholarship as photography and other novel media for recording sights and sounds came into being.

On one level, Adams’s book masks its earnestness and bluffs at being a kind of light guidebook for his “nieces.” He assumes the posture of a convivially, albeit sometimes condescendingly, uncle-like cicerone, leading his young fellow Protestant Americans on a grand tour of the Catholic Middle Ages. One of his true nieces depicts, in a few quick verbal brushstrokes, a day at Chartres when he shares his prophet-like wisdom, knowledge, and enthusiasm. On another plane, and outside the privileged eddies of those nearest and dearest to him, Mont Saint Michel and Chartres could fulfill the principle of noblesse oblige—it could serve as an edification, enhancement, and enticement to the ever-larger bands of less wealthy readers whose peregrinations would take place mainly through print. They might not have the means to board transatlantic steamships and sail in staterooms or even the most modest berths to Europe, but they had access to visual glories such as Chartres through expanding media of communication. These other channels ranged from the humble postcard (see Fig. 1.34) through more sophisticated products such as the stereoscopic slide.

Photographs of sights were major constituents of armchair travel. Yet books were no less present than they had been in the first half of the century, when Henry Adams’s boyhood perusal of Sir Walter Scott’s novels molded his earliest images and impressions of the Middle Ages. In fact, economic and industrial advances assured that printed resources were available to a larger readership than ever before. For want of functional time machines, diachronic journeys have tended to necessitate immersion in texts. When primary works exist from the earlier culture under investigation, they make an unmatched starting point. Secondarily, writings from other cultures confer the benefits of comparison. The literature of scholarship constitutes a third textual corpus that can expand understanding of the past. Supplementing all three sorts of reading, Adams possessed knowledge and experience that he had earned outside the library, from travels abroad and from engagement with hosts of interlocutors and correspondents. The book of experience can be the most useful one on the shelf of life.

To some of Adams’s contemporaries, the hell-for-leather pace of development in their world was disheartening, even baleful. To others, it meant the opening of opportunities. To the wisest, it signified both. Yet does apparent change correspond to the real thing? The French have a saying that has become a bromide since its first documented use in 1849: “Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose,” which in English has become, “The more things change, the more they stay the same.” The thought corresponds, but something still gets lost in translation.

Fig. 1.34 Postcard depicting Chartres Cathedral

(Versailles: A. Bourdier, ca. 1896–1912).

Reluctant Professor

Eventually Adams’s self-identity as a historian in the strictest sense (see Fig. 1.35) rested upon his History of the United States during the First Administration of Thomas Jefferson to the Second Administration of James Madison. But when the mammoth work was completed, its author realized that the nine volumes were out of tune with the times—and with his own self. The masterpiece reflected him as he had been in 1870, rather than as he was in 1890.

The thousands of pages of his huge book, despite the many insights they afforded, failed to deconstruct the past and reconstruct it in ways opportune to foreseeing or fashioning the future of the country. After all, the nation was undergoing wrenching changes even as Henry Adams wrote. Larger ambitions may have kindled in him the desire to explicate America as it had been in 1800. Family history played a role, since that year had witnessed the trouncing of John Adams by Jefferson in the presidential election—but inflating the importance of that turning point in the Adamsian dynasty would be a misjudgment. Another of the author’s motivations may have been to make sense of 1800 while it could still be discerned in the rearview mirror as he took a spin in one of many recent inventions that were transforming the world, the automobile.

Adams accepted an appointment at Harvard University at the ripe age of thirty-two, still primed to be a wunderkind, in the very year of 1870 that he singled out in corresponding with Elizabeth Cameron. The professorship offered him was not in early American but rather in medieval history. Fortuitously, but still not irrelevantly, the future incumbent was lodging at the ruins of a medieval monastery, Wenlock Abbey, when the letter arrived that invited him to take the post. At the time, Adams was not a presumptive shoo-in for the chair in terms of his intellectual profile or past track record. He had not penned a single word on any topic bearing on the Middle Ages, and his only degree was his Harvard BA. He was recruited by Charles W. Eliot (see Fig. 1.36), who had become president of the university after Henry’s father, Charles Francis Adams, had declined that post. In his autobiography, the has-been academic recounts ironically his final discussion as professor-to-be with Eliot. The tête-à-tête took place in September of 1870, after Adams had returned from Europe in the face of the Franco-Prussian war. He averred that the history of the Middle Ages was a closed book to him, but Eliot parried with a pledge: “If you will point out to me anyone who knows more, Mr. Adams, I will appoint him.” Outplayed, the prospective appointee tendered his acceptance.

The whole of France was soon to whirl downward in a prolonged tailspin. In contrast, Harvard benefited from the overall prosperity and confidence that distinguished the United States at that time. No better barometer can be established for the balmy breezes prevailing within American culture than to observe that in 1869 and 1870 three major art museums were founded: the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, DC, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. All three brought the art of the Middle Ages in at the ground floor. More generally, all three reflected a collective, national commitment to cultural advancement and education, an enterprise that had no more prominent and affluent expression, then or now, than at the great university in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

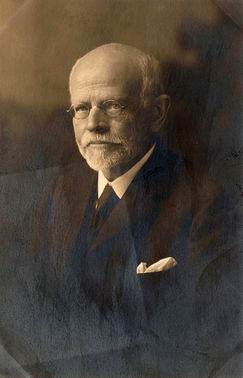

Fig. 1.35 Henry Adams. Photograph by Marian Hooper Adams, 1883. Boston, Massachusetts Historical Society, Marian Hooper Adams Photographs, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Henry_Adams_seated_at_desk_in_study,_writing,_in_light_coat,_photograph_by_Marian_Hooper_Adams,_1883.jpg

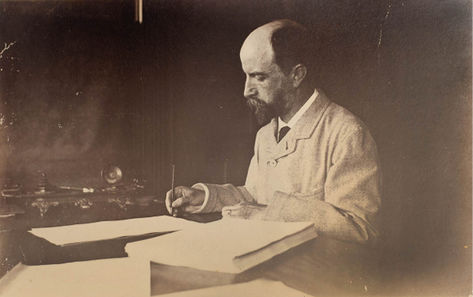

When Adams assumed the position as a medievalist at the university, he proclaimed to a friend that he was completely unknowledgeable, indeed “utterly and grossly ignorant” of medieval history, but nonetheless undeterred. This profession of ignorance was overplayed. At least in the honeyed hindsight of the memoirs he wrote almost exactly a half century later, he had had in 1858 a warmly positive and lyrical reaction to his very first unmediated exposure to the Middle Ages. In that year, he experienced his first European town, in the form of Antwerp (see Fig. 1.37). Although Adams overstated his dearth of knowledge, the move to the professorship at Harvard did dragoon him into embarking upon a sustained mission of self-education. In many regards, he was an amateur antiquarian where the Middle Ages were concerned. Soon he was held accountable for a thousand years of history, and taught a general survey of Europe from the tenth to sixteenth centuries.

In The Education of Henry Adams, Adams felt impelled to label “Failure” the chapter on his years as a Harvard faculty member. His own worst critic, and yet never lacking confidence, he could not give himself a passing mark. Not a decade after taking his professorship as if it had been potluck, he left the university to seek further education in an unexpected place, outside any institution, as a gentleman and a scholar. Initially, he remained at least in aspiration a historian, but his identity allowed and even compelled him to have other ambitions, for both power and creation.

Fig. 1.36 Charles William Eliot. Photograph by E. Chickering & Co., 1904. Washington, DC, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Fig. 1.37 Antwerp Cathedral. Engraving, 1855. Artist unknown. Charles A. Dana, ed.,

Meyer’s Universum: Views of the Most Remarkable Places and Objects of All Countries

(New York: H. J. Meyer, 1855), 6390.

Five of Hearts

From 1870 onward, Henry Adams’s career was shot through with paradoxes. Despite ostensibly shunning the public eye, he became as near to a public intellectual as the America of his times allowed—but not through cultivating ties with the media. His days of personal involvement in journalism were tapering to an end. On the contrary, he entered social bonds and correspondence with the leading lights in the politics and culture of his era. Some of these ties were spasmodic and sometimes skin-deep, but others could not have been more intimate.

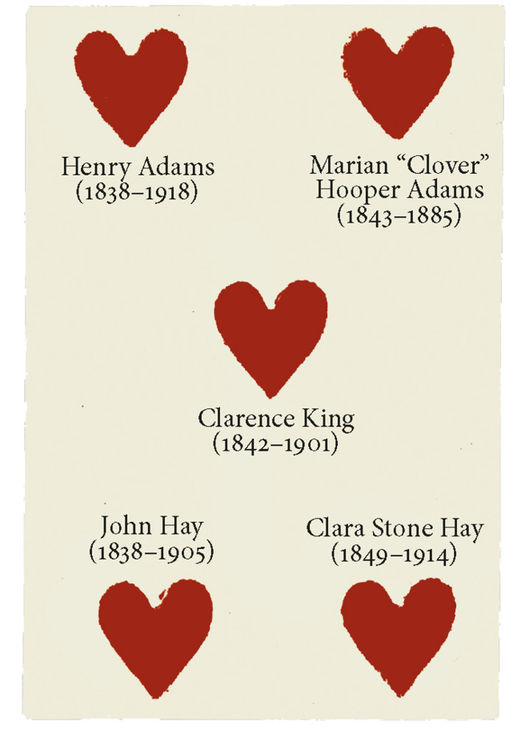

In 1877, Adams moved to Washington with his spouse after resigning from Harvard. As he wiped the slate clean and made a fresh start in his life, he became one in a small clique of tight-knit friends. The so-called Five of Hearts (see Fig. 1.38) took shape in 1879. The handful counted as its members Henry Adams and his wife Marian Hooper Adams (known to familiars as Clover), the later Secretary of State John Hay and his life partner Clara Stone Hay, and the geologist Clarence King. This circle constituted the coterie of implicit readers for which he drafted letters, fiction, and history. At too rushed a glance, the fivesome could seem even more restricted than his associates among the best and the brightest at university. After all, they were all white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant, and, to boot, preponderantly New Englanders. Yet the reality was not entirely so socially and culturally monochromatic.

Fig. 1.38 The “Five of Hearts,” comprising Henry Adams, photographer Marian Hooper Adams, geologist Clarence King, Secretary of State John Hay, and his wife Clara Stone Hay. Vector Art by Melissa Tandysh, 2016. Image courtesy of Melissa Tandysh. All rights reserved.

Henry Adams’s engagement book notes that Clover and he were first in each other’s company on May 16, 1866, at a dinner party in London, when he was serving as his father’s amanuensis at the American Legation. She was on her Grand Tour with her father. Five and a half years later, the couple-to-be met more meaningfully in Cambridge at the home of Clover’s sister Ellen and her brother-in-law Ephraim Whitman Gurney. The encounter occurred not long after Henry Adams had accepted his Harvard appointment. On February 27, 1872, he proposed to his future wife, and on June 27, they married, before leaving on a honeymoon down the river Nile. They made their return voyage to America in mid-August of 1873.

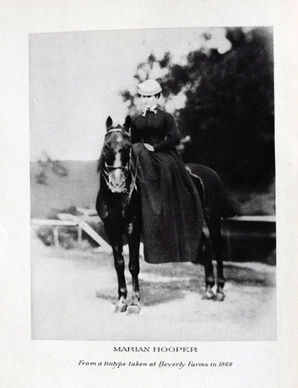

Coming to grips with Clover individually, with Henry and her as a twosome, and with the modulations in their relationship in the final year before her suicide is challenging. Late in her all-too-short life she became an avid photographer. Yet she left of herself exceedingly few images, either visual or verbal, that allow us much insight into her inner self. Relatively few of her many letters have survived. Her own portrait must be pieced together almost entirely from those she made of others (see Fig. 1.39). A person of no small brainpower, she was esteemed by Henry James as possessing “a touch of genius.” She was widely read. Conversant in French, German, and Spanish, she had been well schooled also in Latin and Greek. At times, she served her husband as an unpaid and unacknowledged research assistant. At least while they were abroad, she pitched in to lend a hand in the drudgework of his scholarly endeavors. More important was her social contribution. At home in Washington, she had as a hostess a flair for badinage that helped to make their home a hub of the beau monde in the city.

Fig. 1.39 Marian Hooper. Photograph, 1869. Photographer unknown. Published in Ward Thoron, ed., The Letters of Mrs. Henry Adams, 1865–1883 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1936), frontispiece.

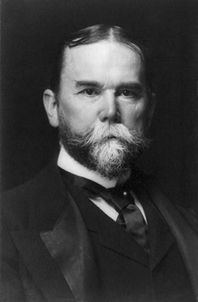

Of the other couple in the Five of Hearts, Clara Stone Hay, born into an exceedingly wealthy family in Ohio, looks to have been as stolid in character as embonpoint in physique. Tight-laced, without the flair as a writer that the other four possessed, she seems the odd person out. In contrast, her husband John had shown from an early age a way with words that in time he matched with a worldly wisdom. The two qualities go a long way in explaining why he had a close rapport with another American who had come of age along the Mississippi, Mark Twain. John figured among Adam’s closest friends and became his next-door neighbor. Heeding the realtors’ mantra “Location, location, location,” the two families could not have deposited themselves any nearer the seat of power without filling it themselves: they resided in Lafayette Square, directly across from the White House. The original edifice was a double house that Hay and Adams commissioned together (see Fig. 1.40). The smaller portion of the structure belonged to Adams. It was the western home that faced Lafayette Park. The larger part was occupied by the statesman Hay and his family. Today, the Hay-Adams luxury hotel, built in 1928, covers the lot where their homes once stood.

In keeping with an Adamsian tradition of filial service, Henry had assisted as right-hand man to his father in England during the Civil War. Yet that employment was private: he never held public office or served the government. Still, thanks both to his illustrious name and even more to his relationship with John Hay, he enjoyed extraordinary access to the inner workings and levers of American power (see Fig. 1.41). It might be tempting to view Adams as basking in the reflected glory of these wheelings and dealings. After all, his friend was adjacent to a heady succession of chief executives. As a very young man, Hay (who had been raised in Indiana and Illinois) was appointed a secretary to Abraham Lincoln. Later, he was one of the longest-serving Secretaries of State. His service under both Presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt enabled or even obliged him to make an imprint on US diplomacy that remains unparalleled. Since his forte was foreign policy rather than domestic public affairs, it would be going too far to call Hay a kingmaker. The politics of the times was as much a free-for-all as ever, but the statesmanly Hay managed to stay largely unmarked and untainted. Such was his intimacy with national chieftains that he kept watch by the bedsides of both Lincoln and McKinley when they died after being wounded by assassins. Coincidentally, but not irrelevantly, Hay’s only break from lifelong public service came in a five-year stint as a journalist in New York, which overlapped roughly with Adams’s appointment at Harvard University.

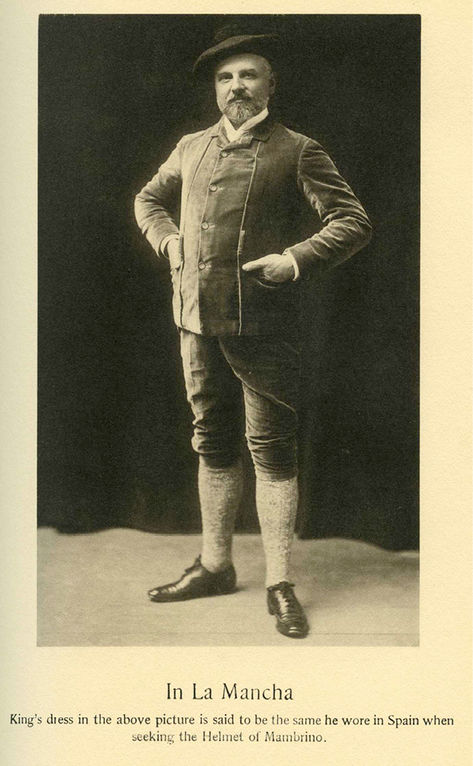

The last of the five was the swaggering and swashbuckling Clarence King (see Fig. 1.42), a Yale graduate raised in Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Massachusetts. His panache made a deep impact upon Hay and Adams—the former even named a son Clarence after this friend. Beyond being intelligent and inventive, King had a vitality and derring-do that they admired. He earned admiration as a frontiersman of formidable energy, a mountaineer of proven mettle, and a raconteur of the first rank. Especially in view of his expertise as a prospector, he can be read metaphorically in hindsight as a high-carat diamond in the rough. However, when we put the loupe to our eyeball and peer closely, the quality cut of the precious stone stands out less than do the unpolished edges.

Fig. 1.40 Hay-Adams residences, N.W. corner of 16th and H. Streets, Washington, D.C.

Unknown photographer, 1885. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Fig. 1.41 John Hay. Photograph by Hollinger & Rockey, ca. 1897. Washington, DC,

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

King’s triumphs as a prospector and surveyor culminated in his appointment as the first head of the United States Geological Survey. In 1881, he resigned from that post and never returned to government employment. Most memorably, he grabbed headlines by exposing an attempted flimflam. The swindle involved gemstones that had been planted to deceive potential investors. Yet after the early éclat from the great diamond hoax of 1872, his promise flatlined. Over the long run, he drew a blank and failed to deliver in all his own ventures.

When King died, the insolvency of his estate made clear how far short of the mark he had fallen in business. Compounding the downward whorl of financial collapse, the conduct of his personal affairs would have shocked the Five of Hearts, had all his intimates known even a little of the double life he led. Hay and Adams (although to a much lesser extent and capacity) felt obliged as men of honor to cover their friend’s debts. The money was the least of the posthumous scandal that they paid to hush.

Under the false name of James Todd, King had conducted a sham marriage and shadow existence. Although white and blue-eyed, he passed himself off as a railroad worker of African-American ancestry. In this guise, he entered common-law marriage with a woman in Brooklyn who in the parlance of the times was a Negress. The two had a public wedding of sorts. Todd hoodwinked his partner into thinking that he was of her race but light-skinned, and he fathered five children by her. All the while, King concealed this side of his world from all his Caucasian acquaintances. Could he have done more? Should he have been braver? Anti-miscegenation legislation had criminalized interracial marriage in many states. Even absent such laws, social views ran strongly against unions between the races. King had every reason to keep quiet about his liaison, and after his death his friends paid dearly to keep what was then dirty laundry from being aired.

Fig. 1.42 Clarence King. Photograph, ca. 1882–1884. Photographer unknown.

Published in Clarence King, Memoirs: The Helmet of Mambrino

(New York, London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904), 37.

Self-Made Medievalist

The American mind might go back to Puritanism or to William Penn, but it lacked that which preceded them; it lacked the Middle Ages. It was in the position of a man who has never known his mother. The American conquest of the Middle Ages has something of that romantic glamor and of that deep sentimental urge which we might expect in a man who should set out to find his lost mother.

—Ernst Robert Curtius

Henry Adams followed his paternal grandfather, John Quincy Adams, to a teaching post at Harvard. The latter served a spell as the first Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory, while the former held a professorship in medieval history. Henry lasted at the university for only seven years, however, retiring early, in 1877, not a long way into his forties. His next step was to return to the District of Columbia, in a hunt for greater personal freedom. Initially, he chose to pursue without encumbrance his investigation of early nineteenth-century America. The move was a gamble, staked partly on personal ambition and partly on faith in the future of Washington, DC. In a trice, the capital grew from a dream into a reality (see Fig. 1.43). Adams may well have wagered that the city would become the center of mass within the United States of America not only for affairs of state and politics, but also for culture and what we might call “soft power.” In this case his bet would have paid off only modestly. Metropolises such as New York and Chicago, in the first stages of becoming the megalopolises they are today, won out at the expense of Boston and Washington.

Fully two decades later, vicissitudes propelled Henry Adams to steep himself in the twelfth century as he had never done before. Despite being surrounded by friends and so-called nieces, he felt cut off from society. An emotional solitude born of his own unique personal circumstances was compounded by an intellectual malaise shared by many others at the fin de siècle over the political and technological transformation of the country and world in which he had grown up. His reaction to feeling out of touch and isolated was to look back more than one half millennium earlier and to brush up on his medieval history. He closed a letter at the time by relating his immersion in the Middle Ages only half-jokingly to his rejection of institutionalized instruction and even political institutions in his own day.

In The Education of Henry Adams, its author described the years at the turn of the century as collective stagnation. In his eyes, the world and its social structure appeared to be spalling and splintering. Yet if concord could not be reinstated, it was not for want of seeking out in the past a golden age, and endeavoring to renew or imitate it. Politics of personal identity, sexual gender, and social class tore at the very seams of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These relations were apparently thought to have been less fraught in the Middle Ages; as a result, the medieval period stirred enthusiastic nostalgia. But nostalgia is too facile a word and escapism too simple a concept to capture Adams’s multifactorial attitudes toward the Middle Ages as he envisaged them.