Notes

© 2018 Jan M. Ziolkowski, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0146.07

Day by day America drifts farther & farther away from Europe. Charles Eliot Norton, Letter to Henry James, December 5, 1873, Harvard Library, bMS Am 1094 (379).

Notes to Chapter 1

Adams Family

Who we are is who we were. The line is spoken by John Quincy Adams in the film Amistad, directed by Steven Spielberg and released in 1997. It does not appear in the published transcript of the trial. An inference might be that who we are as well as who we were is contingent upon who later people say we are and were.

wealthy and prestigious. One of his brothers, Charles Francis Adams Jr., headed the Union Pacific Railway from 1884 to 1890.

waning. For example, his father fell out of favor during the administration of Ulysses S. Grant, and his brother was ousted (railroaded out?) from the top position at Union Pacific.

the Athens of America. Thomas H. O’Connor, The Athens of America: Boston, 1825–1845 (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2006).

serving as an envoy. More precisely, Minister Plenipotentiary.

I must study Politicks and War. Letter to Abigail (“Portia”) Adams, without date, 1780, in L. H. Butterfield and Marc Friedlaender, eds., Adams Family Correspondence, 12 vols. (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1973–2013), vol. 3. Online at Adams Family Papers: An Electronic Archive (Massachusetts Historical Society), http://www.masshist.org/digitaladams

Jean-Baptiste de La Curne de Sainte-Palaye. Lionel Gossman, Medievalism and the Ideologies of the Enlightenment: The World and Work of La Curne de Sainte-Palaye (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press, 1968).

a mire of failings. Essai sur les mœurs et l’esprit des nations et sur les principaux faits de l’histoire depuis Charlemagne jusqu’à Louis XIII, 2 vols. (Paris: Garnier frères, 1963), 2: 10: “Les mœurs ne furent pas meilleurs ni en France, ni en Angleterre, ni en Allemagne, ni dans le Nord. La barbarie, la superstition, l’ignorance couvraient la face du monde, excepté en Italie” (“Morals were not better in France, England, Germany, or in the North. Barbarism, superstition, and ignorance covered the face of the world, except in Italy”).

last and greatest deity of all. Henry Adams, Mont Saint Michel and Chartres (henceforth MSMC), chap. 11 “The Three Queens,” in idem, Novels, Mont Saint Michel, The Education, ed. Ernest Samuels and Jayne N. Samuels (New York: Library of America, 1983), 523.

desacralized. Adams, MSMC, 523.

Great Scott! Sir Walter

Will our posterity understand. Hours in a Library (London: Smith, Elder, 1907), 1: 186–229, at 187, originally published as “Hours in a Library, No. 3: Some Words about Sir Walter Scott,” The Cornhill Magazine 24 (September 1871): 278–93, cited by John Henry Raleigh, “What Scott Meant to the Victorians,” Victorian Studies 7.1 (1963): 7–34, at 7.

peaches and pears. In what is likelier coincidence than literary allusion, Adams specifies pears, which a millennium and a half earlier in the Confessions, Augustine had professed guiltily to having stolen in his own youth. Henry Adams, The Education of Henry Adams (henceforth EHA), chap. 2, “Boston (1848–1854),” 755. Here Adams lists in reverse chronological order Scott’s first and second medieval-themed novels, respectively, the 1820 Ivanhoe and the 1823 Quentin Durward. The Talisman, from 1825, also set in the Middle Ages, is the second of the Scottish author’s “Tales of the Crusaders” subseries from within the Waverley Novels.

Gothic generation. Walter Scott, The Antiquary, ed. Nicola Watson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 150.

tilt at a ring. Leon Howard, Victorian Knight-Errant: A Study of the Early Literary Career of James Russell Lowell (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1952), 5. On Lowell’s early and thorough exposure to Scott, see pp. 4, 5, 6, 25, 28, 40.

carousel. Barbara Bell, “The Performance of Victorian Medievalism,” in Beyond Arthurian Romances: The Reach of Victorian Medievalism, ed. Lorretta M. Holloway and Jennifer A. Palmgren (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), 191–216, at 210–11. For the time being the definitive treatment remains Frederick Fried, A Pictorial History of the Carousel (New York: A. S. Barnes, 1978).

knights astraddle steeds. The Italian term for carousel is overtly the word for jousting: giostra, cognate with joust. These words derive ultimately from a Latin verb meaning to bring near or together, from iuxta “near.”

no one escaped Scott-free. On the contribution of Scott to the medieval revival, see Alice Chandler, A Dream of Order: The Medieval Ideal in Nineteenth-Century English Literature (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1970), 12–51 (“Origins of Medievalism: Scott”). On the obsolescence of his oeuvre since the twentieth century, see Ann Rigney, The Afterlives of Walter Scott: Memory on the Move (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012). On his influence in Europe, see Murray Pittock, ed., The Reception of Sir Walter Scott in Europe, Athlone Critical Traditions Series: The Reception of British Authors in Europe, vol. 13 (London: Continuum, 2006).

Scott-ish. Although Scott’s novels have plummeted from sight like a large rock to the bottom of a lake, ripples of his medievalese continue to radiate from the dropping point. In my view we owe partly, although ever more obliquely, to Scott the frequency of some odd vocabulary, morphology, and syntax in historical fiction today. On such language (but without consideration of Scott), see Miriam Youngerman Miller, “‘Thy Speech Is Strange and Uncouth’: Language in the Children’s Historical Novel of the Middle Ages,” Children’s Literature 23 (1995): 71–90.

impressions of the Middle Ages. The English adjective medieval is first attested in 1817. Although the attestation does not appear in a text composed by Scott, it owes indirectly to the vogue for the period that more than anyone else of his day he helped to instigate in the English-speaking world.

The first documented use (spelled mediæval) is by an antiquarian, Thomas Dudley Fosbroke (1770–1842), in British Monachism; or, Manners and Customs of the Monks and Nuns of England: To Which Are Added I. Peregrinatorium Religiosum: or, Manners and Customs of Ancient Pilgrims. II. The Consuetudinal of Anchorets and Hermits. III. Some Account of the Continentes, or Persons Who Had Made Vows of Chastity. IV. Four Select Poems in Various Styles, 2nd ed. (London: J. Nichols, 1817), vi: “he professes to illustrate mediæval customs upon mediæval principles, from a persuasion, that contemporary ideas are requisite to the accurate elucidation of history.” On this usage, see David Matthews, Medievalism: A Critical History (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2015), 52, and especially David Matthews, “From Mediaeval to Mediaevalism: A New Semantic History,” The Review of English Studies, n.s. 62 (2011): 695–715. Without reference to this specific passage, see Clare A. Simmons, “Medievalism: Its Linguistic History in Nineteenth-Century Britain,” Studies in Medievalism 17 (2009): 28–35.

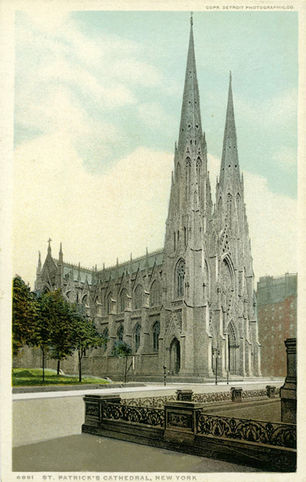

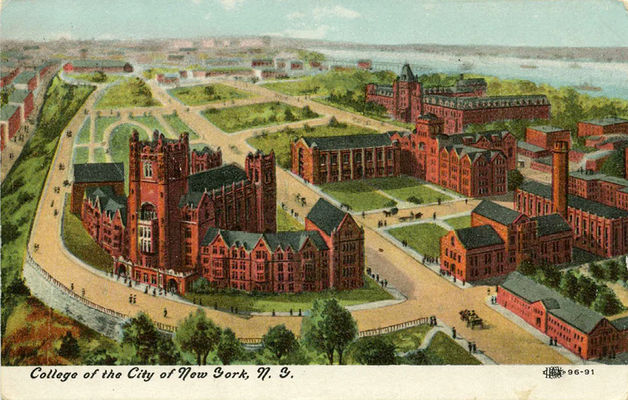

throughout the United States. William H. Pierson Jr., American Buildings and Their Architects: Technology and the Picturesque, The Corporate and the Early Gothic Styles, American Buildings and Their Architects, vol. 2.1 (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1978), 290–91.

the romances of courts and castles. Quoted by Mark Zwonitzer, The Statesman and the Storyteller: John Hay, Mark Twain, and the Rise of American Imperialism (Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books, 2016), 178–79 (with coverage also of Mark Twain’s views on Scott).

taste for medievalesque horror. In turn, their outpourings initiated a tradition of literary criticism upon this undertow of the Gothic revival that remains alive to this day. See Peter Sabor, “Medieval Revival and the Gothic,” in The Cambridge History of Literary Criticism, vol. 4, The Eighteenth Century, ed. H. B. Nisbet and Claude Rawson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 470–88.

historicizing realism. Elizabeth Fay, Romantic Medievalism: History and the Romantic Literary Ideal (Houndmills, UK: Palgrave, 2002), 71–78.

Eglinton Tournament. The competition was staged in Eglinton in Ayrshire, in the west of Scotland.

This mass spectacle. The literature on this event is substantial. For a contemporary account, see James Aikman, An Account of the Tournament at Eglinton, Revised and Corrected by Several of the Knights, illus. W. Gordon (Edinburgh, UK: H. Paton, Carver and Gilder, 1839), https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100234865. For a twentieth-century analysis, see Ian Anstruther, The Knight and the Umbrella: An Account of the Eglinton Tournament, 1839 (London: Geoffrey Bles, 1963). More recently, see Bell, “Performance of Victorian Medievalism,” 200–204; Albert D. Pionke, “A Ritual Failure: The Eglinton Tournament, the Victorian Medieval Revival, and Victorian Ritual Culture,” Studies in Medievalism 16 (2008): 25–45; Paul Pickering, “‘Hark ye back to the age of valour’: Re-Enacting Chivalry from the Eglinton Tournament to Kill Streak,” in Chivalry and the Medieval Past, ed. Katie Stevenson and Barbara Gribling (Woodbridge, UK: Boydell, 2016), 198–214. Historical pageants had been held earlier elsewhere, notably from 1826 on in Bavaria: see Stephen Brockmann, Nuremberg: The Imaginary Capital (Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2006), 52.

Scott’s fictions. R. Aaron Rottner, “The Lay of the Last Minstrel,” in Medieval Art in America: Patterns of Collecting, 1800–1940, ed. Elizabeth Bradford Smith (University Park: Palmer Museum of Art, Pennsylvania State University, 1996), 66–69, at 69.

Mark Twain. For the broadest comparison of the two, see Kim Moreland, The Medievalist Impulse in American Literature: Twain, Adams, Fitzgerald, and Hemingway (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1996), 77–117, especially 77–80.

The Sir Walter Disease. Mark Twain, Life on the Mississippi, in idem, Mississippi Writings (New York: Library of America, 1982), 217–616, at 501. On medievalism in another of Twain’s works, see David L. Vanderwerken, “The Triumph of Medievalism in ‘Pudd’nhead Wilson,’” Mark Twain Journal 18.4 (1977): 7–11.

The South has not yet recovered. Twain, Life on the Mississippi, 468.

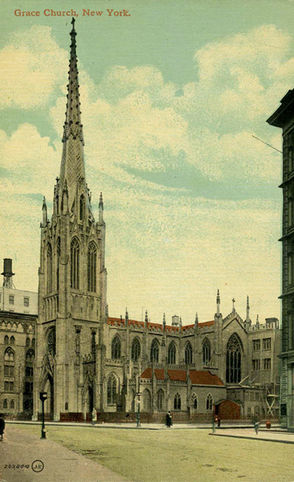

Richard M. Upjohn. The son of the similarly named Gothic revivalist Richard Upjohn, without the middle initial M. On the father, see Stephen McNair, “Richard Upjohn and the Gothic Revival in Antebellum Alabama,” in A. W. N. Pugin’s Global Influence: Gothic Revival Worldwide, ed. Timothy Brittain-Catlin, Jan De Maeyer, and Martin Bressani, KADOC-Artes, vol. 16 (Leuven, Belgium: Leuven University Press, 2016), 106–17.

the novelist had built. The architect was Edward Tuckerman Potter.

Keeping school in a castle. Twain, Life on the Mississippi, 469.

instinctive comprehension and genius. Letter to Ward Thoron, February 20, 1911, in LHA, 6: 416.

I wish Walter Scott were alive. Letter to Charles Milnes Gaskell, August 7, 1913, in Letters of Henry Adams, 1858–1918, ed. Worthington Chauncey Ford, 2 vols. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1930–1938), https://archive.org/details/lettersofhenryad028297mbp, 2: 615.

Gothic Harvard

In my sublimated fancy. Letter to Elizabeth Cameron, August 3, 1896, in LHA, 4: 410–13, at 412.

Gilded Age. Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner, The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (Hartford, CT: American Publishing Company, 1873).

concurrence rather than coincidence. The phrase is drawn from Tony Tanner, “The Lost America—The Despair of Henry Adams and Mark Twain,” in idem, Scenes of Nature, Signs of Men, Cambridge Studies in American Literature and Culture, vol. 31 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 79–93, at 79. Tanner makes no reference to their views on the Middle Ages. For contrasts, see Moreland, Medievalist Impulse, 77–78, 87–88, 101–2.

academic pursuit of the Middle Ages. William Courtenay, “The Virgin and the Dynamo: The Growth of Medieval Studies in America (1870–1930),” in Medieval Studies in North America: Past, Present and Future, ed. Francis G. Gentry and Christopher Kleinhenz (Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 1982), 5–22.

purpose-built of granite. From a design by Richard Bond.

copy of the chapel of King’s College. The Bostonians (1886), chap. 2. The lapidary likeness has long since disappeared, along with the card catalogue that James describes.

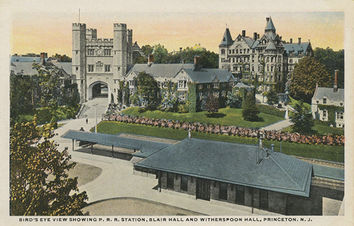

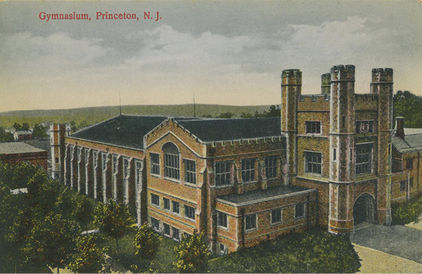

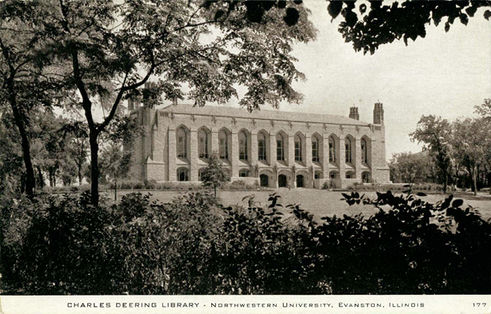

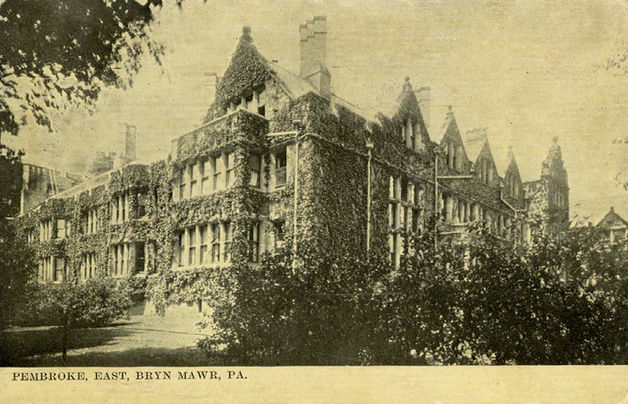

deep impression. Gore Hall must have been if not an inspiration, then at least a Gothic gadfly to Yale College. In New Haven, Connecticut, the loosely comparable Dwight Hall and Chapel preserve what was once the library, built between 1842 and 1847, designed by Henry Austin and Andrew Jackson Davis, in association with Ithiel Town (see Fig. n.1). See James F. O’Gorman, Henry Austin: In Every Variety of Architectural Style (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2008), 122–30.

Fig. n.1 Dwight Hall, Yale University, New Haven, CT. Photograph by Ned Goode, 1964. Washington, DC, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

wedding of the picturesque and the Gothic. Michael Charlesworth, “The Ruined Abbey: Picturesque and Gothic Values,” in The Politics of the Picturesque: Literature, Landscape, and Aesthetics since 1770, ed. Stephen Copley and Peter Garside (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 62–80.

president of Harvard. He held office from that year until 1849.

the Yard. The connotations of the noun as it has become frozen in the expression Harvard Yard, deserve close examination. A yard is often but not always enclosed. It is cognate with “garden.” How a “yard” in the Harvardian sense overlaps with “campus” elsewhere in the terminology applied to American colleges and universities should be teased out.

First Parish Church. Then called the Meeting House, across Massachusetts Avenue from Johnson Gate. This iteration of the Unitarian Meeting House was the fifth, built in 1833.

Carpenter Gothic. The wooden structure featured a façade turreted and punctuated by lancets. In other decoration, the exterior boasted intricate hook-shaped ornaments known as crockets, distinctive finials to adorn elements that projected upward, and the elaborately carved boards known as bargeboards or vergeboards that hang from the projecting ends of roofs.

Appleton Chapel. Its name alone lives on, appropriated for the chancel of today’s Memorial Church, the utterly dissimilar building that replaced the original.

high-wheeled bicycle. This type of two-wheeler is also known as a penny-farthing.

His father. The Reverend Dr. Charles Lowell.

altering his name. Howard, Victorian Knight-Errant, vii.

The Vision of Sir Launfal. Howard, Victorian Knight-Errant, 272.

the Middle Ages was an age of faith. Chandler, Dream of Order, 235. On Lowell’s medievalism, see Howard, Victorian Knight-Errant.

satirized a craftsman. James Russell Lowell, “The Unhappy Lot of Mr. Knott,” Graham’s Magazine 38 (April 1851): 281–87, quoted in part by Loth and Sandler, Only Proper Style, 99.

preindustrial Germany. Adams, EHA, chap. 6, “Rome (1859–1860),” 976.

The Cathedral. The original is preserved as James Russell Lowell, Holograph, The Cathedral, Special Collections, Concord Free Public Library, Concord, MA.

published conjointly. In the “Vest-Pocket Series of Standard and Popular Authors.”

the composition. The full title of the ode is “The Ode Recited at the Commemoration of the Living and Dead Soldiers of Harvard University, July 21, 1865.” The Cathedral; and the Harvard Commemoration Ode (Boston: James R. Osgood, 1877).

School of Fine Arts. In French, École des Beaux-Arts.

pilgrimage. The anecdote is recounted in Charles Moore, Daniel H. Burnham; Architect, Planner of Cities, 2 vols. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1921), 2: 67.

no age to get cathedrals built. Lowell, “The Cathedral,” line 524.

the individual was a facet of Boston. Letter to Henry James, November 18, 1903, in LHA, 5: 524.

hub of the solar system. He used the phrase in an article, which appeared in Atlantic Monthly 1.6 (April 1858): 734–44, at 734. The article was one of a series, “The Autocrat of the Breakfast Table.” The columns were reprinted later as The Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table (Boston: Phillips, Sampson, 1861), chap. 6.

Mont Saint Michel and Chartres. Henry Adams, Mont Saint Michel and Chartres (Washington, DC: Privately printed, 1904). The first place name is often rendered as Mont-Saint-Michel. The Library of America edition holds that the title should be without the hyphens, as it was in both the original printing of 1904 and the reedition of 1911 that Adams oversaw directly: see Adams, MSMC, 1219. The hyphens appeared first in the trade edition by Ralph Adams Cram.

education the schools could not give. Ralph Adams Cram, My Life in Architecture (Boston: Little, Brown, 1936), 145.

a historical romance of the year 1200. Letter to Elizabeth Cameron, April 27, 1902, in LHA, 5: 378–81, at 378.

fertility idols. See also Kim Moreland, “Henry Adams, the Medieval Lady, and the ‘New Woman,’” Clio 18 (1989): 291–305, at 294–95.

Madonna and Child with Saints. Purchased from Artaud de Montor. See Elizabeth Bradford Smith, “The Earliest Private Collectors: False Dawn Multiplied,” in idem, Medieval Art in America, 23–33, at 26–28.

collections of Italian primitives. Smith, “Earliest Private Collectors,” 29.

The Medieval Mind. Reissued at least once a decade until the 1980s.

French. Henry Adams, Mont-Saint-Michel et Chartres, trans. Georges Fradier and Jacques Brosse (Paris: Laffont, 1955).

Photographic Memory

mention of a Kodak. Adams, MSMC, Preface, in Novels, 341.

predecessors. Anthony Hamber, “The Use of Photography by Nineteenth Century Art Historians,” Visual Resources 7.2–3 (1990): 135–61.

image-based analysis. The Seven Lamps of Architecture, vol. 8 of The Works of John Ruskin, ed. E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn, 39 vols. (London: George Allen, 1903–1912), “Preface to the Second Edition [1855],” 7–14, at 13: “The Gothic of Verona is far nobler than that of Venice; and that of Florence nobler than that of Verona. For our own immediate purposes that of Notre-Dame of Paris is noblest of all; and the greatest service which can at present be rendered to architecture, is the careful delineation of details of the cathedrals above named, by means of photography.”

daguerreotypes. Karen Burns, “Topographies of Tourism: ‘Documentary’ Photography and The Stones of Venice,” Assemblage 32 (1997): 22–44. See also Michael Harvey, “Ruskin and Photography,” Oxford Art Journal 7 (1985): 25–33.

Amiens cathedral. Mark B. Pohlad, “William Morris, Photography, and Frederick H. Evans,” History of Photography 22.1 (1998): 52–59.

diagrams. These drawings are on pp. 107–13 (1904) and 108–14 (1912).

1913 reprint. This reprint was for the American Institute of Architects. It contains twelve illustrations in addition to a colored frontispiece.

photo-phobia. Letter to Elizabeth Cameron, September 8, 1891, in LHA, 3: 540–49, at 547.

plaster casts. James K. McNutt, “Plaster Casts after Antique Sculpture: Their Role in the Elevation of Public Taste and in American Art Instruction,” Studies in Art Education 31 (1990): 158–67.

niece. For the avuncular relationship in a literal sense, see Abigail Adams Homans, Education by Uncles (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1966).

carry a camera. Kim Moreland, “The Photo Killeth: Henry Adams on Photography and Painting,” Papers on Language and Literature 27 (1991): 356–70, at 370.

as a generic term. The name of this all-American product related to the Dakota Territory—later admitted into the Union as North and South Dakota—where the device was invented by a Scottish immigrant: see Mina Fisher Hammer, History of the Kodak and Its Continuations: The First Folding and Panoramic Cameras. Magic Lantern—Kodak—Movie (New York: Pioneer Publications, 1940), 17, 46.

In that final decade of the nineteenth century, snapshot and Kodak become documented words for “photograph,” as were snapshottist and Kodaker for “photographer.” See Christian Kay et al., Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary, 2 vols. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 1: 1731, 03.11.03.02.10.02 (n.) photograph (with snap alongside snapshot and Kodak) and 03.11.03.02.10.01 (n.) photographer (with snapshooter, snapshotter, and Kodakist among the additional forms attested).

medium of scholarly record. “The third figure is a queen, charming as a woman, but particularly well-dressed, and with details of ornament and person elaborately wrought; worth drawing, if one could only draw; worth photographing with utmost care to include the strange support on which she stands: a monkey, two dragons, a dog, a basilisk with a dog’s head” (chap. 5, “Towers and Portals,” in Adams, MSMC, 410).

Monuments Historiques. National Historical Sites of France.

having in hand photos. For example, “If you have any doubts about this, you have only to compare the photograph of Coutances with the photograph of Chartres” (chap. 4, “Normandy and the Île de France,” in Adams, MSMC, 387); also, “One can hardly call it a device; it is so simple and evident a piece of construction that it does not need to be explained; yet you will have to carry a photograph of this flèche to Chartres, and from there to Vendome [sic], for there is to be a great battle of flèches about this point of junction, and the Norman scheme is a sort of standing reproach to the French” (ibid., 389); and finally, “This long panegyric, by Viollet-le-Duc, on French taste at the expense of Norman temper, ought to be read, book in hand, before the Cathedral of Rouen, with photographs of Bayeux to compare” (ibid., 392).

systematic archives. Cases in point would be: “The central clocher will begin a photographic collection of square towers, to replace that which was lost on the Mount” (ibid., 388); “Your photographs of Bayeux or Boscherville or Secqueville will show you at a glance whether the term ‘adresse’ applies to them” (chap. 5, “Towers and Portals,” in ibid., 400); “Any photograph shows that the Auxerre spire is also simple” (ibid., 401).

his intimate friend Elizabeth Cameron. Adams, Letter to Elizabeth Cameron, October 23, 1899, in LHA, 5: 49–52, at 51.

a few quick verbal brushstrokes. Homans, Education by Uncles, 142.

armchair travel. Bernd Stiegler, Traveling in Place: A History of Armchair Travel, trans. Peter Filkins (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013).

its first documented use. The first attestation of the saying has been ascribed to Alphonse Karr (1808–1890), in an epigram in Les Guêpes (January 1849), a monthly he edited.

Reluctant Professor

History of the United States. Henry Adams, History of the United States during the First Administration of Thomas Jefferson to the Second Administration of James Madison (New York: Charles Scribner, 1889–1891), https://archive.org/details/cu31924092892631

as he had been in 1870. He confessed to Elizabeth Cameron: “It belongs to the me of 1870; a strangely different being from the me of 1890.” See Adams, Letter to Elizabeth Cameron, February 6, 1891, in LHA, 3: 402–10, at 408.

Another of the author’s motivations. The best introduction to this massive and complex work is Garry Wills, Henry Adams and the Making of America (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2005). On Adams’s historical consciousness specifically regarding the Middle Ages, see Hans Rudolf Guggisberg, Das europäische Mittelalter im amerikanischen Geschichtsdenken des 19. und des frühen 20. Jahrhunderts, Basler Beiträge zur Geschichtswissenschaft, vol. 92 (Basel, Switzerland: Helbing und Lichtenhahn, 1964), 65–76 (on his involvement with Anglo-Saxon law), 113–36 (on both him and his brother Brooks).

I will appoint him. Adams, EHA, chap. 19, “Chaos (1870),” 988.

utterly and grossly ignorant. Adams, Letter to Charles Milnes Gaskell, September 29, 1870, in LHA, 2: 81–82, at 81.

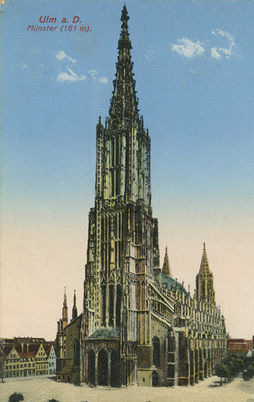

Antwerp. Adams, EHA, chap. 5, “Berlin (1858–1859),” 787–88: “The thirteenth-century cathedral towered above a sixteenth-century mass of tiled roofs, ending abruptly in walls and a landscape that had not changed. The taste of the town was thick, rich, ripe, like a sweet wine; it was mediaeval, so that Rubens seemed modern; it was one of the strongest and fullest flavors that ever touched the young man’s palate; but he might as well have drunk out his excitement in old Malmsey, for all the education he got from it. Even in art, one can hardly begin with Antwerp Cathedral and the Descent from the Cross. He merely got drunk on his emotions, and had then to get sober as he best could. He was terribly sober when he saw Antwerp half a century afterwards.”

Failure. Adams, EHA, chap. 20, “Failure (1871),” 993–1006.

Five of Hearts

Marian Hooper Adams. Taking her published letters as a representative indicator of her name use, we find that in instances when she signed any name at all, she called herself Marian or “M.A.” sixty-eight percent of the time, with an increase over her life. But the surge could signify more correspondence outside her circle of intimates. See Marian Hooper Adams, The Letters of Mrs. Henry Adams, 1865–1883, ed. Ward Thoron (Boston: Little, Brown, 1936), part 1 (total 0/0); part 2 (total 0/3—July–November 1872 = 0/14, November 1872–March 1873 = 0/8, March–July 1873 = 0/9); part 3 (total 20/30—June–August 1879 = 10/12, August–October 1879 = 4/7, October–December 1879 = 6/11); part 4 (total 101/116—October 1880–May 1881 = 30/38, October 1881–June 1882 = 38/44, October 1882–May 1883 = 33/34).

first in each other’s company. Otto Friedrich, Clover (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1979), 73.

her Grand Tour. Natalie Dykstra, Clover Adams: A Gilded and Heartbreaking Life (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012), 48.

they married. Dykstra, Clover Adams, 55 (on the proposal), 59 (on the wedding and honeymoon).

return voyage to America. Dykstra, Clover Adams, 74.

a touch of genius. Henry James, Letter to Henry James Sr., October 11, 1879, in idem, The Letters, ed. Leon Edel, 4 vols. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1974–1984), 2: 257–60, at 258. The context of the phrase is worth quoting more fully for its Jamesian flavor: “Henry is very sensible, though a trifle dry, and Clover has a touch of genius (I mean as compared with the usual British Female).”

The larger part. It fronted on Sixteenth Street, across from Saint John’s Episcopal Church.

five-year stint as a journalist. Hay was with the New-York Tribune from 1870 to 1875. He also achieved modest fame as an author of ballads and a novel.

he fathered five children by her. Martha A. Sandweiss, Passing Strange: A Gilded Age Tale of Love and Deception across the Color Line (New York: Penguin, 2009). All of this he kept secret from others in his life, most particularly his mother in Newport. Of the four offspring who survived to become adults, the two daughters married white men and were regarded as white themselves. The two sons were subsumed into the racial category then called Negro.

Self-Made Medievalist

The American mind might go back to Puritanism. Ernst Robert Curtius, European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages, trans. Willard R. Trask, Bollingen Series, vol. 36 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990), 587 (appendix, “The Medieval Bases of Western Thought,” a lecture delivered on July 3, 1949).

Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory. Donald M. Goodfellow, “The First Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory,” New England Quarterly 19.3 (1946): 372–89.

brush up on his medieval history. Adams, EHA, chap. 24, “Indian Summer (1898–1899),” 1057: “Solitude did what the society did not;—it forced and drove him into the study of his ignorance in silence. Here at last he entered the practice of his final profession. Hunted by ennui, he could no longer escape, and, by way of a summer school, he began a methodical survey,—a triangulation,—of the twelfth century.”

rejection of institutionalized instruction. Adams, Letter to Cecil Arthur Spring Rice, February 1, 1900, in LHA, 5: 80–83, at 83: “Twelfth-centurian that I am, I detest a university under all circumstances, and loathe science more than knowledge. Let us abolish Congress!”

collective stagnation. Adams, EHA, chap. 22, “Chicago (1893),” 1023: “Drifting in the dead-water of the fin-de-siècle,—and during this last decade everyone talked, and seemed to feel fin-de-siècle,—where not a breath stirred the idle air of education or fretted the mental torpor of self-content, one lived alone.”

spalling and splintering. Walter Laqueur, “Fin-de-Siècle: Once More with Feeling,” Journal of Contemporary History 31.1 (1996): 5–47, at 15: “The wholesome harmony of past ages could not be restored.”

enthusiastic nostalgia. Elizabeth Emery and Laura Morowitz, Consuming the Past: The Medieval Revival in fin-de-siècle France (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2003), 4.

religion and art. Adams, Letter to Albert Stanburrough Cook, August 6, 1910, in LHA, 6: 356–57: “I wanted to show the intensity of the vital energy of a given time, and of course that intensity had to be stated in its two highest terms,—religion and art.” In Mont Saint Michel and Chartres itself, Adams avowed: “Religious art is the measure of human depth and sincerity” (chap. 16, “Saint Michiel de la Mer del Peril,” in Adams, MSMC, 346).

had the half-title. In its first and second private printings.

North American Review. The literary journal was edited by the art historian Charles Eliot Norton from 1864 to 1868.

interplay. To a considerable degree, his second and last novel, Esther, already deals with these interchanges. It was published under the pseudonym of Frances Snow Compton, in 1884, and identified only posthumously as Adams’s creation.

The Law of Civilization and Decay. Brooks Adams, The Law of Civilization and Decay: An Essay on History (New York: Macmillan & Co., 1895), https://archive.org/details/lawofcivilizatio00adam, and America’s Economic Supremacy (New York: Macmillan, 1900).

alienated patrician. Van Wyck Brooks, The Wine of the Puritans: A Study of Present-Day America (London: Sisley’s, 1908), https://archive.org/details/cu31924028739443, 135–36, describes the phenomenon as a close contemporary, which is analyzed decades later by Michael D. Clark, “Ralph Adams Cram and the Americanization of the Middle Ages,” Journal of American Studies 23 (1989): 195–213, at 196.

the new church of St. John’s. Samuels and Samuels, Novels, 187–91 (the opening scene), 1217 (on the textual history of the publication and authorship).

real-life Trinity Church. On the relationship between Saint John’s in Manhattan in the novel and Trinity in Boston in reality, see Charles Vandersee, “User: Henry Adams and Esther,” in The Makers of Trinity Church in the City of Boston, ed. James F. O’Gorman (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2004), 139–51, at 139–42.

four-story brownstone. At 91 Marlborough Street, at the corner of Marlborough and Clarendon Streets: see Dykstra, Clover Adams, 73.

presumptions of familiarity. Herbert L. Creek, “The Mediaevalism of Henry Adams,” South Atlantic Quarterly 24 (1925): 86–97.

failed to open his senses. Adams, Letter to Mabel Hooper, September 1, 1895, in LHA, 4: 313–16, at 314. See also Adams, EHA, chap. 23, “Silence (1894–1898),” 1043: “If history had a chapter with which he thought himself familiar, it was the twelfth and thirteenth centuries; yet so little has labor to do with knowledge that these bare playgrounds of the lecture system turned into green and verdurous virgin forests merely through the medium of younger eyes and fresher minds.” He does not restrain himself from referring to virgin forests.

droll analogy. Adams, Letter to Mabel Hooper, September 1, 1895, in LHA, 4: 313–316, at 315: “The squirming devils under the feet of the stone Apostles looked uncommonly like me and my generation.”

his character was rooted. Adams, Letter to John Hay, September 7, 1895, in LHA, 4: 319–21, at 319–20: “I was a vassal of the Church; I held farms—for I was many—in the Cotentin and around Caen, but the thing I did by a great majority of ancestors was to help in building the cathedral of Coutances, and my soul is still built into it. I can almost remember the faith that gave me energy, and the scared boldness that made my towers seem to me so daring, with the bits of gracefulness that I hazarded with some doubts whether the divine grace could properly be shown outside. Within I had no doubts. There the contrite sinner was welcomed with such tenderness as makes me still wish I were one. There is not a stone in the whole interior which I did not treat as though it were my own child. I was not clever, and I made some mistakes which the great men of Amiens corrected. I was simple-minded, somewhat stiff and cold, almost repellant to the warmer natures of the south, and I had lived always where one fought handily and needed to defend one’s wives and children; but I was at my best. Nearly eight hundred years have passed since I made the fatal mistake of going to England, and since then I have never done anything in the world that can begin to compare in the perfection of its spirit and art with my cathedral of Coutances. I am as sure of it all as I am of death.”

The Goths in New England. George Perkins Marsh, The Goths in New-England: A Discourse Delivered at the Anniversary of the Philomathesian Society of Middlebury College, August 15, 1843 (Middlebury, VT: Printed by J. Cobb, 1843), 14.

Anglo-Saxons. Reginald Horsman, Race and Manifest Destiny: The Origins of American Racial Anglo-Saxonism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981). For a different and more recent approach to some of the same issues, see Laura Kendrick, “The American Middle Ages: Eighteenth-Century Saxonist Myth-Making,” in The Middle Ages after the Middle Ages in the English-Speaking World, ed. Marie-Françoise Alamichel (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1997), 121–36.

Across the Atlantic. Chris Waters, “Marxism, Medievalism, and Popular Culture,” in History and Community: Essays in Victorian Medievalism, ed. Florence Boos (New York: Garland, 1992), 137–68.

Henry Adams was led to northern France. Curtius, European Literature, 587.

The Normans. Charles Homer Haskins, The Normans in European History (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1915), 12. On Adams’s views on the Normans as a race, see William Dusinbere, Henry Adams: The Myth of Failure (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1980), 203.

John La Farge. James L. Yarnall, John La Farge: A Biographical and Critical Study (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2012).

Already as an undergraduate. La Farge studied at what would later become Fordham University.

beauty of the medieval ideal. Royal Cortissoz, John La Farge: A Memoir and a Study (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1911), https://archive.org/details/johnlafargememoi00cortrich, 68.

rival of Louis Comfort Tiffany. Julie L. Sloan, “The Rivalry between Louis Comfort Tiffany and John La Farge,” Nineteenth Century 17 (1997): 27–34.

printing it privately. One hundred and fifty copies were printed in 1904, five hundred in 1912.

an act of homage. Adams, Letter to Elizabeth Cameron, February 8, 1903, in LHA, 5: 452–55, at 453: “My only hope of Heaven is the Virgin. If I tried to vulgarise her, and made her as cheap as cow-boy literature, I should ask for eternal punishment as a favor.”

my great work on the Virgin. Cited by Ernest Samuels, Henry Adams (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1989), 354 (by mid-March of 1903 or 1904).

The peril of the heavy tower. Henry Adams, MSMC, 695 (chap. 16, “Saint Thomas Aquinas”).

stayed in print. A recent printed edition is the paperback Mont Saint Michel and Chartres (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989). The text is also available electronically. The standard edition is Adams, MSMC, 337–714. Adams adhered to the same, somewhat coy practice with his self-study, The Education of Henry Adams. He circulated the book privately from a limited print run that he brought out at his own expense in 1907, first in forty copies but later ratcheted up to one hundred. Only after his death in 1918 was the autobiography published commercially. In 1919, the book—considered to this day “one major work of enduring importance”—topped the list of nonfiction bestsellers. See Michael Korda, Making the List: A Cultural History of the American Bestseller, 1900–1999 (New York: Barnes and Noble, 2001), 18, 32. Education was also posthumously awarded the Pulitzer Prize.

Notes to Chapter 2

The Nature of the Book

literature of France in the Middle Ages. Robert Mane, Henry Adams on the Road to Chartres (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971), 153 (following Max Baym).

earliest piece of French secular theater. It was composed in 1282 or 1283.

It was translated. Aucassin et Nicolette: Chantefable du douzième siècle, trans. Alexandre Bida, ed. Gaston Paris (Paris: Hachette, 1878).

lack of human passion. Philip Henry Wicksteed, trans., Our Lady’s Tumbler (Portland, ME: Thomas. B. Mosher, 1900), viii–ix.

the majesty of Chartres. These are the last words of the chapter in MSMC, 604 (chap. 13, “Les Miracles de Notre Dame”): “If you can feel it, you can feel, without more assistance, the majesty of Chartres.”

witnessed an evolution. Ernst Scheyer, The Circle of Henry Adams: Art and Artists (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 1970), 111–13.

antimodern modernist. T. J. Jackson Lears, No Place of Grace: Antimodernism and the Transformation of American Culture, 1880–1920 (New York: Pantheon, 1981), 262–97, at 297 for “antimodern modernist.”

the last word. MSMC, 604 (chap. 13, “Les Miracles de Notre Dame”): “If you cannot feel the color and quality,—the union of naïveté and art,—the refinement,—the infinite delicacy and tenderness—of this little poem, then nothing will matter much to you.” This sentence leads directly into the closing statement about “the majesty of Chartres” quoted in the earlier note.

toy house. MSMC, 424 (chap. 6, “The Virgin of Chartres”): “To us, it is a child’s fancy; a toy-house to please the Queen of Heaven,—to please her so much that she would be happy in it,—to charm her till she smiled.”

issued repeatedly. Notably, there were printings in 1898, 1899, 1900, and 1904.

the English came into print. The English is Gaston Paris, Mediaeval French Literature, trans. Hannah Lynch (London: J. M. Dent, 1903); pp. 84–85 deal with Our Lady’s Tumbler. The circumstances of the publication are recounted in the “Avertissement des éditeurs” with which the French edition opens: Gaston Paris, Esquisse historique de la littérature française au Moyen Âge (depuis les origines jusqu’à la fin du XVe siècle) (Paris: Armand Colin, 1907), https://archive.org/details/esquissehistoriq00pari, vii.

the greatest academic authority in the world. Max I. Baym, The French Education of Henry Adams (New York: Columbia University Press, 1951), 108.

in his correspondence. Letter to Ward Thoron, January 2, 1911, in LHA, 6: 401. On Paris without reference to the book specifically, see the letters to Raymond Weeks, February 16, 1912, and to Frederick Bliss Luquiens, April 8, 1912, in ibid., 6: 508–11, at 508, and 529–31, at 530, respectively.

his personal library. Adams’s own copy of the French La littérature française au Moyen Âge is held in the Massachusetts Historical Society, located in Boston. On the scoring, see Mane, Henry Adams, 157.

philological items. In an appendix, Baym, French Education, 291–301, catalogues other “philological items” known to have been in Adams’s collection of French books; many are still extant.

We can’t grapple it. Letter to Elizabeth Cameron, April 16, 1912, in LHA, 6: 534–35, at 535.

attuned early. Clover Adams, letter to Dr. Hooper, December 18, 1881, in idem, Letters of Mrs. Henry Adams, 310–14, at 313, cited by Dykstra, Clover Adams, 271.

betrays an easy familiarity. Letters to Sir Robert Cunliffe, October 19, 1897, to Mary Cadwalader Jones, August 15, 1912, and to Charles Milnes Gaskell, August 30, 1912, in LHA, 4: 490–91, at 491; 6: 550–51, at 550, and 6: 553–54, at 553, respectively.

Adams’s observation. Adams would have heard through newspapers and word of mouth about Massenet’s opera not long after its opening night in Monaco, but because Adams first published his book in 1904, he is highly unlikely to have seen a performance before he finished the writing. If he had read the libretto, he did not mention it in his correspondence.

Madonna of Medieval France, La Dona of Washington

hopes of enjoying intimacies. Dykstra, Clover Adams, 215–19.

his interactions with her. In the meantime, she had other paramours. At least one of them was a much younger man known to him. Another, probably without his knowledge, was his close friend John Hay. John Taliaferro, All the Great Prizes: The Life of John Hay, from Lincoln to Roosevelt (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013), passim.

decades. Their correspondence ran from 1883 until his death in 1918.

he read aloud to her. Arline Boucher Tehan, Henry Adams in Love: The Pursuit of Elizabeth Sherman Cameron (New York: Universe, 1983), 206.

wordplay. On the relationship between Adams and Cameron, see Tehan, Henry Adams in Love, esp. p. 11 on the nickname. It punned affectionately on the Spanish title doña, the Italian donna, or both.

would hardly have felt surprised. Henry Adams, Esther, in idem, Novels, 222 (chap. 4). On the modeling, see Friedrich, Clover, 305. The place of Adams’s wife in the same novel differed starkly, since the title character with whom she has been identified is described as having “nothing medieval about her.” See Adams, Esther, in idem, Novels, 200 (chap. 1).

superimposed his mental image. Tehan, Henry Adams in Love, 208.

an 1891 letter. Letter to Elizabeth Cameron, November 5, 1891, in LHA, 3: 556–61, at 561: “As I grow older I see that all the human interest and power that religion ever had, was in the mother and child, and I would have nothing to do with a church that did not offer both. There you are again! you see how the thought always turns back to you.”

Madonna del Prato. Known also as Madonna del Belvedere. The canvas depicts the Virgin with the Christ Child and John the Baptist. The depiction is commonly seen as reflecting the influence of Michelangelo. Alternatively, and not necessarily exclusively, the reference could point to Giovanni Bellini’s work (1505) by the same title (see Fig. n.2).

Fig. n.2 Giovanni Bellini, Madonna del Prato, 1505. Oil on canvas, 67 × 86 cm. London, National Gallery, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Giovanni_bellini,_madonna_del_prato_01.jpg

His Madonnas were prized. David Alan Brown, Raphael and America (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1983).

born to paint Madonnas. Eugène Müntz, Raphael: His Life, Works and Times, trans. Walter Armstrong, 2nd ed. (London, 1888), 70.

Madonna of the Chair. In Italian, Madonna della seggiola or Madonna della sedia.

people stand in worshipful silence. Transatlantic Sketches (Boston: James R. Osgood, 1875), 293, quoted by Brown, Raphael and America, 25, who on p. 98n53 provides this and other citations on the high standing of Raphael’s Madonnas in American culture at the time.

Sistine Madonna. Dykstra, Clover Adams, 63.

buying craze. Manfred J. Holler and Barbara Klose-Ullmann, “Art Goes America,” Journal of Economic Issues 44.1 (2010): 89–112.

depictions of the Virgin Mary. Such as the Madonna and Child Enthroned donated by John Pierpont Morgan Jr. to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, or the Small Cowper Madonna given by Joseph E. Widener to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, in memory of his father P. A. B. Widener.

craving to own a Raphael Madonna. James Fenton, “Don’t Take Our Raphael! (The ‘Madonna of the Pinks’),” New York Review of Books 49.20 (2002): 50–52.

Giovanni Battista Salvi da Sassoferrato. Known to his contemporaries as “painter of Virgins,” he is now often called simply by his place of origin, Sassoferrato. See Cecilia Prete, ed., Sassoferrato, Pictor Virginum: Nuovi studi e documenti per Giovan Battista Salvi (Ancona, Italy: Il lavoro editoriale, 2010). The painting, acquired by Hay in Europe in 1890, has been in the Saint Louis Art Museum since 1961.

round in format. Such a circular painting is technically called tondo.

religious rest. Letter to John Hay, August 20, 1899, in LHA, 5: 14–16, at 14.

returned repeatedly. In the summer of 1900, he crowed to his brother Brooks about leading “a hermit’s life, intellectually in the twelfth century, and corporeally in no recognized division of time.” Letter to Brooks Adams, July 29, 1900, in LHA, 5: 142–44, at 143. In the autumn, he reported in a letter to Hay that he fancied himself “a twelfth-century monk in a nineteenth-century attic, in Paris” and “a monk of St Dominic, absorbed in the Beatitudes of the Virgin Mary.” Letter to John Hay, November 7, 1900, in ibid., 5: 167–69, at 167, 169. This passage and a few others to follow from Mont Saint Michel and Chartres are quoted by Marilu Putnam McGregor, “Henry Adams’ Mont Saint Michel and Chartres: The Chanson de Geste of a Nineteenth-Century Jongleur” (PhD diss., University of Houston, 2001), 1, to whom I am indebted. The mention of an attic is captivating, since it fuses the idea of a cloistered medieval brother with the romantic stereotype of the indigent artist in a garret.

The cloister still occupied Adams’s mind a year later in the spring of 1901. When acknowledging receipt of a book by Henry Osborn Taylor, he presented himself as suffering from lassitude and needing cloistered tranquility. Thinking himself alone in this condition, he professed surprise to discover from reading his former colleague’s volume that Taylor too was even more deeply versed in the same Middle Ages that obsessed him. Letter to Henry Osborn Taylor, May 4, 1901, in LHA, 5: 247–48, at 247: “[I] only returned [to the Middle Ages], at last, because I was tired, and wanted quiet and solitude and absorption. I thought myself alone, and suddenly I find you in possession of the whole cloister. Are there others?” Conjuring up an image of what the writer envisaged is painless (see Fig. n.3).

Fig. n.3 “Fra Beato.” Engraving by R. Lehmann, 1874. Published in

The Illustrated London News, November 28, 1874, 509.

More than once. Let us not forget that Adams presented the memoir and Mont Saint Michel and Chartres as companion pieces, a sort of diptych.

English monastery. As it more commonly called today; it is also known as St. Milburga’s Priory. The abbey is located in Much Wenlock, Shropshire.

to feel at home in a thirteenth-century Abbey. Adams, EHA, chap. 15, “Darwinism (1867–1868),” 929.

once more took refuge. Adams, EHA, chap. 19, “Chaos (1870),” 985.

If we lived a thousand years ago. Letter to Charles Francis Adams Jr., December 18, 1863, in LHA, 1: 415–17, at 416.

other Boston Goths. For instance, it was the topic of a lead essay in the first issue of the Architectural Review in the fall of 1891. See H. Langford Warren, “Notes on Wenlock Priory,” Architectural Review 1.1 (November 1891): 1–4.

bustle nowhere. Dykstra, Clover Adams, 61. The reader must make the call on whether the key noun refers to business in general or to the type of framework that in nineteenth-century women’s fashion puffed out skirts behind.

books on medieval architecture. Dykstra, Clover Adams, 61. The primary source is LHA, 2: 137.

Trappist monks. Friedrich, Clover, 237. These brothers are a subset of Cistercians.

agnostic Mariolater. On his images of the Virgin and their fit within others held by American intellectuals before and after him, see John Gatta, American Madonna: Images of the Divine Woman in Literary Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 95–115; Daniel L. Manheim, “Motives of His Own: Henry Adams and the Genealogy of the Virgin,” New England Quarterly 63.4 (1990): 601–23; Moreland, “Henry Adams,” 291–305.

lay not far from an actual slab. Clover was also present symbolically within the façade of Romanesque revival home that Henry Hobson Richardson built for them. Not long before her suicide at the age of forty-two, she appears to have sided with the architect and against her spouse by having installed in the front of the house a stone carving of a lion that had above it a cross. For reasons we can only guess, Adams was harrowed by something about the notion of this symbolism. See Friedrich, Clover, 316–17. Part of the stone ensemble can be seen at 2618 31st Street NW, where it was incorporated when the Hay-Adams houses were razed in 1927.

Tintern Abbey. The poem was composed on July 13, 1798. Alternatively, Wenlock could be said to have acquired for Adams the valences that Caspar David Friedrich had portrayed in oil paintings when he showed the dilapidation of both imagined and actual abbeys. Examples by the German romantic painter would be The Abbey in the Oakwood (1809–1810) and Ruins of Eldena near Greifswald (1824–1825).

part of the Gothic revival. To take only one of countless examples, the architect, designer, and critic Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin had studied Dunbrody Abbey in County Wexford, Ireland as a model to uphold in the designs for the churches he built new in the same town (see Fig. n.4).

Fig. n.4 Dunbrody Abbey, Wexford, Ireland. Photograph by Kevin McNamee, 2017,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dunbrody_Abbey,_view_from_South-east.jpg,

CC BY-SA 4.0.

Georgian period. Terence Davis, The Gothick Taste (Rutherford, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1975).

destination for escapists. On such escapism in the nineteenth century, see Kevin L. Morris, The Images of the Middle Ages in Romantic and Victorian Literature (Dover, NH: Croom Helm, 1984); in the early twentieth century (Weimar Republic), Bettina Bildhauer, Filming the Middle Ages (London: Reaktion Books, 2011), 26–29; and, more recently, Thomas A. Prendergast and Stephanie Trigg, “What is Happening to the Middle Ages?” New Medieval Literatures 9 (2007): 215–29.

the eternal child of Wordsworth. Adams, MSMC, 423 (chap. 6, “The Virgin of Chartres”).

postcard. The card is by the fin-de-siècle artist Jack Abeillé.

a broken arch. Adams, MSMC, 349 (chap. 1, “Saint Michiel de la Mer del Peril”): “No doubt, they are right, since they are young: but men and women who have lived long and are tired,—who want rest,—who have done with aspirations and ambition,—whose life has been a broken arch—feel this repose and self-restraint as they feel nothing else. The quiet strength of these curved lines, the solid support of the heavy columns, the moderate proportions, even the modified lights, the absence of display, of effort, of self-consciousness, satisfy them as no other art does.”

with these real and honorary relatives. His election of such nieces as the putative audience for his long meditation belonged to the endpoint in his strange development as a ladies’ man, if indeed he warrants being called that at all. However oddly, he may have been in fact a tombeur (lady-slayer) besides being a tombeor (tumbler). For all that he relished being ringed about by admiring young women, he succumbed now and then to a longing for escape from what he regarded as their garrulity. At those moments he sought out relief from what he identified as avunculitis.

His Marian passion. Adams, EHA, chap. 25, “The Dynamo and the Virgin (1900),” 1075.

Miracles of the Virgin. In French, Miracles de la Vierge. Letter to Charles Milnes Gaskell, December 20, 1904, in LHA, 5: 618–19, at 618.

Our Lady underpins the entire thirteenth century. Adams, MSMC, 576 (chap. 13, “Les Miracles de Notre Dame”): “It had invested in her nearly its whole capital, spiritual, artistic, intellectual and economical, even to the bulk of its real and personal estate.”

considerable resources. He estimated once in writing to Elizabeth Cameron that his dollar expenditures on fieldwork and library work on Mary reached into six figures, an extraordinary sum for the time.

spiritual barrenness. Adams, MSMC, 522 (chap. 10, “The Court of the Queen of Heaven”): “We… can safely leave the Virgin in her Majesty… looking down from a deserted heaven, into an empty church, on a dead faith.”

abides even to his day. Adams, MSMC, 578 (chap. 13, “Les Miracles de Notre Dame”): “The Virgin still remained and remains the most intensely and the most widely and the most personally felt, of all characters, divine or human or imaginary, that ever existed among men.”

I adore the Virgin. Letter to Henry Osborn Taylor, May 4, 1901, in LHA, 5: 247.

Virgin Portal. Adams, EHA, chap. 25, “The Dynamo and the Virgin,” 1072–1073.

Universal Exposition of 1900

the medieval period could hold its own. Ruskin, Seven Lamps of Architecture, 8: 264 (chap. 7, “The Lamp of Obedience”); to Adams, the “mechanical ingenuity… required to build a cathedral” matched or even overmatched what was needed “to cut a tunnel or contrive a locomotive.”

Gallery of Machines. In French, galerie des machines. In his memoir, Adams rang a change upon an earlier simile of his. Whereas before he had likened himself to a broken arch, now he wrote of “his historical neck broken by the sudden irruption of forces totally new.” See Adams, EHA, chap. 25, “The Dynamo and the Virgin,” 1069.

replaced the great churches. Adams, MSMC, 439 (chap. 7, “Roses and Apses”): “All that the centuries can do is to express the idea differently:— a miracle or a dynamo; a dome or a coal-pit; a cathedral or a world’s fair; and sometimes to confuse the two expressions together. The world’s fair tends more and more vigorously to express the thought of infinite energy; the great cathedrals of the Middle Ages always reflected the industries and interests of a world’s fair.”

a Chicago Exposition for God’s Profit. Adams, Letter to Elizabeth Cameron, September 18, 1895, in LHA, 4: 325–27, at 326–27: “The ultimate cathedral of the 13th century was deliberately intended to unite all the arts and sciences in the direct service of God. It was a Chicago Exposition for God’s profit. It showed an Architectural exhibit, a Museum of Painting, Glass-staining, Wood and Stone Carving, Music, vocal and instrumental, Embroidering, Jewelry and Gem-setting, Tapestry-weaving, and I know not what other arts, all in one building.”

visits he paid to the exhibition. See T. J. Jackson Lears, “1900: An Artist of Ideas Ponders the Dynamo at the Paris Exposition,” in A New Literary History of America, ed. Greil Marcus and Werner Sollors (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009), 450–55, at 450–51. An engrossing book could be written on the place of the Middle Ages in nineteenth-century exhibitions. Highly stimulating pages are to be found in John M. Ganim, Medievalism and Orientalism: Three Essays on Literature, Architecture and Cultural Identity (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), 83–107. A sequel would deal with their subsequent repositioning in the twentieth-century successors to those earlier fairs.

medieval was grouped with the oriental. Hubert Howe Bancroft, The Book of the Fair: An Historical and Descriptive Presentation of the Columbian Exposition at Chicago, 1893, 5 vols. (Chicago: Bancroft, 1893), 5: 835: “Entering the avenue a little to the west of the Woman’s building, they would pass between the walls of mediæval villages, between mosques and pagodas, Turkish and Chinese theatres…”

symbolism of the dynamo and the Virgin. Paul J. Hamill Jr., “The Future as Virgin: A Latter-Day Look at the Dynamo and the Virgin of Henry Adams,” Modern Language Studies 3.1 (1973): 8–12.

Palace of Electricity. In French, Palais de l’électricité.

second law of thermodynamics. His sustained effort to make the case is a short book, printed in 1910, entitled A Letter to American Teachers. See Keith R. Burich, “Henry Adams, the Second Law of Thermodynamics, and the Course of History,” Journal of the History of Ideas 48.3 (1987): 467–82.

Adams had no foreknowledge. On how close Adams came to prophesying the atomic bomb, see Lewis Mumford, “Apology to Henry Adams,” The Virginia Quarterly Review 38.2 (1962): 196–217.

cut off its own existence. Letter to Charles Francis Adams Jr., April 11, 1862, in LHA, 1: 289–92, at 290: “Man has mounted science, and is now run away with… Some day science may have the existence of mankind in its power, and the human race commit suicide, by blowing up the world.”

similarly alarmist view. Letter to Brooks Adams, August 10, 1902, in LHA, 5: 399–401, at 400: “I apprehend for the next hundred years an ultimate, colossal, cosmic collapse; but not on any of our old lines. My belief is that science is to wreck us, and that we are like monkeys monkeying with a loaded shell; we don’t in the least know or care where our practically infinite energies come from or will bring us to.”

fathom the rough-and-tumble of politics. Democracy: An American Novel, in Adams, MSMC, 7 (chap. 1): “Here, then, was the explanation of her restlessness, discontent, ambition,—call it what you will. It was the feeling of a passenger on an ocean steamer whose mind will not give him rest until he has been in the engine-room and talked with the engineer. She wanted to see with her own eyes the action of primary forces; to touch with her own hand the massive machinery of society; to measure with her own mind the capacity of the motive power. She was bent upon getting to the heart of the great American mystery of democracy and government.”

unearthed through archaeology. Bonnie Effros, “Selling Archaeology and Anthropology: Early Medieval Artefacts at the Expositions universelles and the Wiener Weltausstellung, 1867–1900,” Early Medieval Europe 16.1 (2008): 23–48; Sally Foster, “Embodied Energies, Embedded Stories: Releasing the Potential of Casts of Early Medieval Sculptures,” in Making Histories: The Sixth International Insular Art Conference 2011, ed. Jane Hawkes (Donington, UK: Shaun Tyas, 2013), 339–57.

Old Paris

savage from the banks of the Orinoco. Gautier, Works, trans. Sumichrast, 11: 272. The Orinoco is a river in South America that flows from Colombia through Venezuela to the Atlantic Ocean.

Paris in 1400. In French, Paris en 1400.

Court of Miracles. In French, Cour des miracles. See, above all, Emery and Morowitz, Consuming the Past, 171–208.

One of three quarters. “Quartier Moyen Âge.” The other two were sixteenth- and eighteenth-century.

half-timbered edifices. These buildings correspond to the style known in German architecture as Fachwerk.

from colonies in Africa and the orient. John M. Ganim, “Medievalism and Orientalism at the World’s Fairs,” Studia Anglica Posnaniensia: International Review of English Studies 38 (2002): 179–91.

In Old Paris. Albert Robida, Le vieux Paris: Guide historique, pittoresque et anecdotique (Paris: s.n., 1900). See Elizabeth Emery, “Protecting the Past: Albert Robida and the Vieux Paris Exhibit at the 1900 World’s Fair,” Journal of European History 35 (2005): 65–85; Laurent Antoine, “Le vieux Paris d’Albert Robida à l’exposition universelle de 1900: Restitution en 3D, patrimoine éphémère et expositions universelles,” in Les expositions universelles en France au XIXe siècle: Techniques publics patrimoines, ed. Anne-Laure Carré et al. (Paris: CNRS Éditions, 2012), 447–59.

parade and street fair. The festival took place on May 29–30, 1898. On it in general, see Elizabeth Emery, “Staging La Fête des fous et de l’âne in 1898: A Commemoration of the Literary Middle Ages,” in Mapping Memory in Nineteenth-Century French Literature and Culture, ed. Susan Harrow and Andrew Watts, Faux titre, vol. 369 (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2012), 59–79. The festivities involved the Place de la Sorbonne in the Latin Quarter and the Place du Panthéon.

hawked their wares. Frederick Brown, For the Soul of France: Culture Wars in the Age of Dreyfus (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010), 231.

Albert Robida. For a biography and bibliography, see Philippe Brun, Albert Robida, 1848–1926: Sa vie, son oeuvre. Suivi d’une bibliographie complète de ses écrits et dessins (Paris: Promodis, 1984).

erase painful memories of damage. Not everyone welcomed the renovation program. The art critic Jules-Antoine Castagnary implied that the simultaneous effacement of the past and rebuilding of it as it had never been would compel the inhabitants of the capital to write afresh their personal, municipal, and national histories. See Kevin D. Murphy, “The Historic Building in the Modernized City: The Cathedrals of Paris and Rouen in the Nineteenth Century,” Journal of Urban History 37.2 (2011): 278–96, at 278.

French predecessor to Walt Disney. For example, consider Martha Bayless, “Disney’s Castles and the Work of the Medieval in the Magic Kingdom,” in The Disney Middle Ages: A Fairy Tale and Fantasy Past, ed. Tison Pugh and Susan Aronstein (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 39–56.

three dimensions. The three-dimensionality has led to the interesting recent project of Antoine, “Le vieux Paris,” 447–59.

cutout mock-ups. Particularly useful (and widely available) is Robida, Le vieux Paris. For the cutout, see L’imagerie d’Épinal et le Vieux Paris, no. 136 (Pellerin et Cie): Église Saint-Julien des Ménétriers-Vieux Paris.

living-history museums. Sten Rentzhog, Open Air Museums: The History and Future of a Visionary Idea, trans. Skans Victoria Airey (Stockholm: Carlsson; [Östersund, Sweden]: Jamtli, 2007). For a strongly America-centric focus, see Scott Magelssen, Living History Museums: Undoing History through Performance (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2007).

Norwegian Museum of Cultural History. The Norsk Folkemuseum at Bygdøy.

Skansen. Founded by the Swede Artur Hazelius. The name, meaning the Sconce, has become a common noun to designate such living museums: skansen. They involved large staffs enacting features of vanished or vanishing folklife, including music and dance.

Saint Julian of the Minstrels. In French, Saint-Julien-des-Ménestriers.

commissioned to be built. For information on the church, see Kay Brainerd Slocum, “Confrérie, Bruderschaft and Guild: The Formation of Musicians’ Fraternal Organisations in Thirteenth- and Fourteenth-Century Europe,” Early Music History 14 (1995): 257–74, at 266.

bell-ringer. Carillon, much in vogue then, is an arrangement that allows twenty-three or more bells in the belfry of a church to be sounded from a keyboard. Also popular was the earlier practice of change-ringing, in which different individuals yanked on ropes or otherwise acted to peal the instruments. Other early music concerts were offered as well by vocal groups. The groups included such as the Schola Cantorum and Chanteurs de Saint-Gervais. See Elizabeth Emery, “Albert Robida, Medieval Publicist,” in Makers of the Middle Ages: Essays in Honor of William Calin, ed. Richard Utz and idem (Kalamazoo, MI: Studies in Medievalism, Western Michigan University, 2011), 71–76, at 74, and Emery, “Protecting the Past,” 69.

Peter Abelard. The medieval French logician and theologian was popularly known best for his affair with Heloise.

The event left many disconcerted. Although the medieval aspects are not discussed, see Richard D. Mandell, Paris 1900: The Great World’s Fair (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1967), 104–21. For the context of the exposition in the experiences of American visitors (particularly Henry Adams) to the French capital, see David McCullough, The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011), 446–49.

Dynamo and Virgin Suicide

wide-mouthed wryness. Letter to Mabel Hooper La Farge, June 17, 1902, in LHA, 5: 386–87, at 387: “My idea of Paradise is a perfect automobile going 30 miles an hour on a smooth road to a twelfth-century cathedral.”

hard put to maintain his aplomb. Letter to Elizabeth Cameron, February 26, 1900, in LHA, 5: 97–99, at 98: “Every day opens a new horizon, and the rate we are going gets faster and faster till my twelfth-century head spins, and I hang on to the straps and shut my poor old eyes.”

such a locomotive. Jonathan Glancey, Architecture (New York: DK Publications, 2006), 374.

Virgin-driven strength of the medieval West. “Never has the Western world shown anything like the energy and unity with which she then flung herself on the East, and for the moment made the East recoil.”

school of Romanesque literature. Letter to Elizabeth Cameron, September 18, 1899, in LHA, 5: 31–34, at 32.

collection of Marian miracles. The edition was of the Gracial, in Anglo-Norman French octosyllables, by one Adgar.

Thomas Aquinas. Ernest Samuels, Henry Adams: The Major Phase (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1964), 220.

Submerging himself in scholastic philosophy. Chandler, Dream of Order, 242.

Prayer to the Virgin of Chartres. The poem was published posthumously in 1920, in Henry Adams, Letters to a Niece and Prayer to the Virgin of Chartres, ed. Mabel La Farge (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1920), https://archive.org/details/letterstoneice00adamrich, 125–34. On Adam of St. Victor’s prayer, see Adams, MSMC, 429–30 (chap. 6, “The Virgin of Chartres”), 643–44 (chap. 15, “The Mystics”).

the last two syllables. On the pun, see Moreland, Medievalist Impulse, 90.

first fair copy. Tehan, Henry Adams in Love, 172–74, 249.

Catholic Renaissance. Samuels, Henry Adams: The Major Phase, 221.

Our Lady of Lafayette Square. John Hay, Letter to Henry Adams, January 3, 1884, quoted and cited by Dykstra, Clover Adams, 162, 282. On her, see Friedrich, Clover; Dykstra, Clover Adams; Eugenia Kaledin, The Education of Mrs. Henry Adams (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1981).

staple of the photographic profession. Adams, Letters of Mrs. Henry Adams, 451. On the relative frequency of such poisonings, see Bill Jay, “Death in the Darkroom,” Phoebus 3 (Tempe: Arizona State University, 1982): 85–98, repr. in Fields of Writing: Readings across the Disciplines, ed. Nancy Comley et al. (New York: St. Martin’s, 1984), 178–92.

at least the first dozen of them. Adams was pointed in emphasizing twelve of the thirteen years in his marriage: see Letter to Edwin L. Godkin, December 16, 1885, in LHA, 2: 643.

sustained and rigorous silence about her. As he observed in a letter in 1891: “Everyone knows that the mark of real despair and deepest sense of abandonment is silence.” Letter to Lucy Baxter, December 22, 1891, in LHA, 3: 592–93, at 592.

Adams Memorial. Fullest information on the monument is available in Lincoln Kirstein, Memorial to a Marriage: An Album on the Saint-Gaudens Memorial in Rock Creek Cemetery Commissioned by Henry Adams in Honor of His Wife, Marian Hooper Adams, with photographs by Jerry L. Thompson and Marian Adams (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989); Cynthia J. Mills, “The Adams Memorial and American Funerary Sculpture (1891–1927)” (PhD diss., University of Maryland, 1996).

designed by Stanford White. James M. Goode, Washington Sculpture: A Cultural History of Outdoor Sculpture in the Nation’s Capital (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), 420–21.

The Peace of God That Passeth Understanding. After the Epistle of Paul to the Philippians 4:7.

Brahma with Buddha. In 1891, Adams wrote a poem that has been entitled “Buddha and Brahma”: Adams, Novels, ed. Samuels and Samuels, 1195–201. In 1895, he copied the lines and sent them to John Hay, with the request that his friend not circulate them. For interpretation, see Vern Wagner, “The Lotus of Henry Adams,” The New England Quarterly 27 (1954): 75–94.

discussions of nirvana. Henry Adams, John La Farge: Essays (New York: Abbeville Press, 1987), 51–54.

Morgan Madonna. “Gothic Art Shown at Metropolitan,” New York Times, July 8, 1908, 6.

all these things at once. Neither Saint-Gaudens nor Adams left any reference to “The Sacrifice of Iphigeneia at Aulis” from Pompeii that survives from the first half of the first century CE. The ancient Roman fresco may be based in turn, at least in part, on a lost original by the Greek painter Timanthes of Cythnos from the fourth century BCE (see Fig. n.5). The wall painting depicts a scene from the body of myths that relate to the Trojan War. To the right the princess of Argos is being dragged off for sacrifice to Artemis, with to the far right either the seer Calchas or her father, King Agamemnon. To the far left stands a mantled shape, either her grieving mother Clytemnestra or her father. For the idea that it was Agamemnon represented in the painting by Timanthes, see Pliny, Historia naturalis 35.73, in Pliny, Natural History, ed. and trans. H. Rackham, 10 vols. (London: William Heinemann, 1952), 9: 314–15. Even in the inconclusive gender of the person hidden within the cowl, the shrouded figure in the fresco very suggestively resembles the statue. Still, the resemblance could be mere coincidence. No evidence exists for supposing that either the patron or the sculptor knew the piece of art, let alone that either had it in mind. From the peristyle of the House of the Tragic Poet, Pompeii, the ancient work (123 × 126 cm) is now in Naples, Italy, Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli.

Fig. n.5 The Sacrifice of Iphigenia, from the House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii. Fresco, first century CE. Naples, Museo archeologico nazionale di Napoli. Photograph by Carole Raddato, 2014. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Sistine Madonna. With all due respect to Patricia O’Toole, The Five of Hearts: An Intimate Portrait of Henry Adams and His Friends (1880–1918) (New York: C. N. Potter, 1990), 165, who mistakes it for a fresco.

universality and anonymity. He wrote, “The whole meaning and feeling of the figure is in its universality and anonymity.” Letter to Richard Watson Gilder, October 14, 1896, in LHA, 4: 430.

not much later. In February of 1892.

explicated devotion to the Mother of God. Adams, MSMC, 582–83 (chap. 13, “Les Miracles de Notre Dame”): “No one has ventured to explain why the Virgin wielded exclusive power over poor and rich, sinners and saints, alike… Why was the Woman struck out of the Church and ignored in the State? These questions are not antiquarian or trifling in historical value; they tug at the very heart-strings of all that makes whatever order is in the cosmos. If a Unity exists, in which and toward which all energies centre, it must explain and include Duality, Diversity, Infinity—Sex!”

psychoanalytic readings of his personal life. On the first issue, see Alfred Kazin, “Religion as Culture: Henry Adams’s Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres,” in Henry Adams and His World, ed. David R. Contosta and Robert Muccigrosso, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, n.s., vol. 83,4 (Philadelphia, PA: American Philosophical Society, 1993), 48–56. On Adams’s attachment to Mary, see Joseph F. Byrnes, The Virgin of Chartres: An Intellectual and Psychological History of the Work of Henry Adams (Rutherford, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1981); Moreland, Medievalist Impulse, 77–117, with notes at 213–19. Adams’s fascination with the Virgin in the Middle Ages is also stressed by Siegmund Levarie, “Henry Adams, Avant-Gardist in Early Music,” American Music 15 (1997): 429–45.

consolation-gift. Byrnes, Virgin of Chartres, 165.

channel his passions. Tehan, Henry Adams in Love, 129 describes in Freudian terms as sublimation his response to Cameron’s distancing of herself from him.

much explored. For an early exposition, see Jonathan Daniels, The End of Innocence (Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, 1954). For the most recent assessment of the issue, see Dykstra, Clover Adams.

spluttered once tactlessly. Still more inconsiderately, all the more so for being unmistaken, he predicted that Henry’s wife would follow in the footsteps of her aunt by taking her own life. Charles Francis Adams Jr., Memorabilia, in Woodrow Wilson Papers, ed. John E. Little (Princeton) unpublished, cited by Kaledin, Education of Mrs. Henry Adams, 264.

recently losing her father. He died on April 13, 1885.

called the baby girl. Dusinbere, Henry Adams, 189.

ratify her passion for photography. On this painful episode in their marriage, see Laura Saltz, “Clover Adams’s Dark Room: Photography and Writing, Exposure and Erasure,” Prospects: An Annual of American Cultural Studies 24 (1999): 458–62.

high-circulation magazine. The periodical in question was The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine.

Henry Adams as Jongleur

exposed before the image. Louis Zukofsky, Prepositions: The Collected Critical Essays of Louis Zukofsky, 2nd ed. (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1981), 86–130, at 116–17.

better cards. Adams, EHA, chap. 1, “Quincy (1838–1848),” 724.

neurasthenia. George M. Beard, “Neurasthenia, or Nervous Exhaustion,” The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal n.s. 3.13 (1869): 217–21; Lears, No Place of Grace, 47–58.

expelled as a useless member. Adams, MSMC, 601 (chap. 13, “Les Miracles de Notre Dame”).

the plight of the writer. See Laurence B. Holland, “A Grammar of Assent,” The Sewanee Review 88.2 (1980): 260–66, at 266.

the bleak modernity of the early twentieth century. For some context, see Keith R. Burich, “Henry Adams’ Annis [sic] Mirabilis: 1900 and the Making of a Modernist,” American Studies 32 (1991): 103–16.

another inducement. Adams, MSMC, 356–57 (chap. 2, “La Chanson de Roland”): “To feel the art of Mont Saint Michel and Chartres we have got to become pilgrims again: but, just now, the point of most interest is not the pilgrim so much as the minstrel who sang to amuse him,—the jugleor or jongleur,—who was at home in every abbey, castle or cottage, as well as at every shrine.”

postured himself as a minstrel. Although it pays little heed to Le Tumbeor Nostre Dame, Marilu McGregor’s “Henry Adams’ Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres” investigates closely Adams’s self-conception as a jongleur.

contrasted his own mission. Henry Adams, Letter to Henry Osborn Taylor, January 17, 1905, in LHA, 5: 627–28, at 628: “Our two paths run in a manner parallel in reverse directions, but I can run and jump along mine, while you must employ a powerful engine to drag your load.”

John La Farge. Letter to Henry Osborn Taylor, May 4, 1901, in LHA, 5: 247–48, at 248: “Between Bishop Stubbs and John La Farge the chasm has required lively gymnastics. The text of Edward the Confessor was uncommonly remote from a twelfth-century window. To clamber across the gap has needed many years of La Farge’s closest instruction.”

juggler. Adams refers to an evolution from jugleor to jongleur.

Taillefer. The name is rendered in Latin as incisor ferri “hewer of iron.” In Latin, the only eleventh-century mention of this juggler was in the Carmen de Hastingae proelio (Poem on the Battle of Hastings). In the twelfth century we have William of Malmesbury’s Gesta regum (Deeds of the Kings) and Henry of Huntingdon’s Historia Anglorum (History of the English). In Old French he appears in Wace’s Roman de Rou and Geoffrey Gaimar’s Estoire des Engleis (History of the English). See William Sayers, “The Jongleur Taillefer at Hastings: Antecedents and Literary Fate,” Viator 14 (1983): 77–88.

drew special attention. Later he was the subject of a 1903 composition by Richard Strauss, who declined suggestions to compose a similar piece based on Our Lady’s Tumbler. The German composer’s opera set to music a ballad composed in 1816 by the German poet Ludwig Uhland.

letter written to Elizabeth Cameron. Letter to Elizabeth Cameron, December 28, 1891, in LHA, 3: 593–98, at 594.

Richard Coeur-de-lion. By the Belgian composer André Grétry, with a text by Michel-Jean Sedaine.

O Richard, O my king. “Oh Richard! oh, mon roi, l’univers t’abandonne.”

camped out in Washington. He lived in two homes, first at 1607 H Street NW with Clover in a house leased from the financier, William Wilson Corcoran, and later in one of his own at 1603 H Street NW, at the corner of H and Sixteenth Streets.

Angelic Doctor. On Adams and Aquinas, see Michael Colacurcio, “The Dynamo and the Angelic Doctor: The Bias of Henry Adams’ Medievalism,” American Quarterly 17 (1965): 696–712.

Unity and Multiplicity

conceived of the two projects. Adams, EHA, chap. 29, “The Abyss of Ignorance (1902),” 1117: “Eight or ten years of study had led Adams to think he might use the century 1150–1250, expressed in Amiens Cathedral and the Works of Thomas Aquinas, as the unit from which he might measure motion down to his own time, without assuming anything as true or untrue except relation. The movement might be studied at once in philosophy and mechanics. Setting himself to the task, he began a volume which he mentally knew as ‘Mont Saint Michel and Chartres: a study of thirteenth-century unity.’ From that point he proposed to fix a position for himself, which he could label: ‘The Education of Henry Adams: a study of twentieth-century multiplicity.’ With the help of these two points of relation, he hoped to project his lines forward and backward indefinitely, subject to correction from anyone who should know better.” The passage gains additional force from being quoted in the opening “Editor’s Preface” in the Library of America edition, p. 719.

recoil from an ‘over civilized’ modern existence. Lears, No Place of Grace, xv.

On German Architecture. In German, Von deutscher Baukunst.

authentic Germanness. Translation and discussion in W. D. Robson-Scott, The Literary Background of the Gothic Revival in Germany: A Chapter in the History of Taste (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1965), 82. For the original text, see Von deutscher Baukunst: Goethes Hymnus auf Erwin von Steinbach, seine Entstehung und Wirkung, ed. Ernst Beutler, Reihe der Vorträge und Schriften, vol. 4 (Munich, Germany: Bruckmann, 1943), 12–13. For a full and detailed consideration, see Harald Keller, “Goethes Hymnus auf das Strassburger Münster und die Wiedererweckung der Gotik im 18. Jahrhundert: 1772–1972,” Sitzungsberichte–Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Philosophisch-Historische Klasse, 1974, vol. 4 (Munich, Germany: Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1974).

in much the same spirit. Adams, EHA, chap. 4, “Harvard College (1854–1858),” 776–77.

later in life. Kaledin, Education of Mrs. Henry Adams, xvi.

anarchical skepticism. Kaledin, Education of Mrs. Henry Adams, 8.