Notes

© 2018 Jan M. Ziolkowski, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0147.08

Dr. Urbino’s most contagious initiative. Love in the Time of Cholera, trans. Edith Grossman (New York: Vintage International, 2003), 44.

Notes to Chapter 1

Opera, next to Gothic architecture. Kenneth Clark, Civilisation: A Personal View (London: BBC, 1969), 241.

The Jongleur in the Circle of Richard Wagner

Minnesingers. This word anglicizes partially the German Minnesänger. A related term is Meistersänger, “master singer.”

the troubadour had become entrenched. Elizabeth Fay, Romantic Medievalism: History and the Romantic Literary Ideal (Houndmills, UK: Palgrave, 2002), 3–8; Clare A. Simmons, Popular Medievalism in Romantic-Era Britain (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 59–62, 89–91.

Giuseppe Verdi’s Il trovatore. The Italian means simply “the troubadour.” The opera had an Italian libretto written mainly by Salvadore Cammarano, which was based on the 1836 Castilian play El trovador by Antonio García Gutiérrez. The premiere took place in Rome on January 19.

a memorial in Parma. The monument, inaugurated in 1920, was constructed by the Italian sculptor Ettore Ximenes, beginning in 1913. A central altar survives, but not the far larger triumphal arch, flanked by semicircular colonnades, that contained statues representing key figures from all of Verdi’s operas. In later mass culture, the troubadour puts in an appearance in the snatches from the musical drama that are incorporated into A Night at the Opera, the 1935 American comedy film starring the Marx Brothers.

This opera. The German title is Tannhäuser und der Sängerkrieg auf Wartburg. Wagner’s familiarity with Minnesinger melodies from the Middle Ages has been considered by Larry Bomback, “Wagner’s Access to Minnesinger Melodies prior to Completing Tannhäuser,” Musical Times 147.1896 (Autumn 2006): 19–31; Michael Scott Richardson, “Evoking an Ancient Sound: Richard Wagner’s Musical Medievalism” (Master’s thesis, Rice University, 2009).

Germanic Middle Ages. Volker Mertens, “Wagner’s Middle Ages,” trans. Stewart Spencer, in Wagner Handbook, ed. John Deathridge et al. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992), 236–68, at 237.

provided a complete picture of the Middle Ages. Mertens, “Wagner’s Middle Ages,” 236.

pilgrimages. Thus, Mark Twain in a travel letter from 1891 (“Mark Twain at Bayreuth,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 6, 1891): “. . . this biennial pilgrimage. For a pilgrimage is what it is”; an anonymous article on Bernard Shaw’s “The Perfect Wagnerite” entitled “The Bayreuth Pilgrim,” Literature (February 17, 1899): 126; Charles Henry Meltzer, “The Coming of Parsifal,” Pearson’s 11.1 (January 1904): 94–104, at 94; Max Simon Nordau, Degeneration (New York: D. Appleton, 1895), 213.

a friend read it aloud to her. Her letter (Munich, March 20, 1890) can be found in Cosima Wagner und Houston Stewart Chamberlain im Briefwechsel, 1888–1908, ed. Paul Pretzsch (Leipzig, Germany: Philipp Reclam jun., 1934), 144–45, at 145 (“Yesterday Dr. [Konrad] Fiedler [1841–1895, art historian] read aloud to us something that I would like to recommend very much to you: Old French Tales, adapted by Wilhelm Hertz. Pick up and read the Dancer of Our Dear Lady; I believe that it will speak to you as to us, and that would please me”); for Houston Stewart Chamberlain’s reply, which mentions the story only in a brief postscript, see 145–48, at 148 (“The Old French book of Hertz is a dear old friend of mine. Tonight, I will read again the story of The Dancer of Our Dear Lady”). Nearly two decades later, in 1908, Chamberlain married Eva von Bülow-Wagner, Cosima’s daughter and Wagner’s step-daughter.

Our Lady’s Dancer. In German, Der Tänzer unserer lieben Frau: see Franz Trenner, ed., Cosima Wagner, Richard Strauss: Ein Briefwechsel, Veröffentlichungen der Richard-Strauss-Gesellschaft, München, vol. 2 (Tutzing, Germany: H. Schneider, 1978), 39 (her initial proposal, in a letter of March 26, 1890: “Recently I thought of you, when I became acquainted with a very beautiful poem, ‘Our Lady’s Tumbler,’ from Wilhelm Hertz’s ‘minstrel book’ [German Spielmannsbuch]. I believe that it would be a beautiful theme for a symphonic poem”), 45 (her follow-up, in a letter of April 15, 1890: “I am eager to know how you like the minstrel book and whether ‘Our Lady’s Tumbler’ gives some inspiration or not. The dance as a basis for the symphony seems to me artistically justified as a conscious theme for it. But only the one who must create it can decide that”), 49 (his reactions, in a letter of May 17, 1890: “Hearty thanks for your recommendation of the charming ‘minstrel book.’ ‘Our Lady’s Tumbler’ is certainly a charming thing; I have already taken it up into myself and must now just patiently wait and see if it dances back out of my heart as a symphonic poem”). See Willi Schuh, Richard Strauss: A Chronicle of the Early Years (1864–1898), trans. Mary Whittall (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982), 217n12.

Wilhelm Hertz. Wilhelm Hertz, ed. and trans., Spielmannsbuch: Novellen in Versen aus dem zwölften und dreizehnten Jahrhundert (Stuttgart, Germany: G. Kröner, 1886), 210–17. In the first half of the twentieth century, the collection was reprinted in 1900, 1905, 1912, and 1931.

The dance as a basis for the symphony seems to me artistically justified. “Der Tanz als Basis der Sinfonie erscheint mir als bewußter Vorwurf derselben künstlerisch berechtigt.”

cadre of Jews. Eric Werner, “Jews around Richard and Cosima Wagner,” Musical Quarterly 71 (1985): 172–99; Milton E. Brener, Richard Wagner and the Jews (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2006).

interpreters have skirmished. Among the most influential and harshest constructions of Levi would be Peter Gay, “Hermann Levi: A Study in Service and Self-Hatred,” in idem, ed., Freud, Jews, and Other Germans: Masters and Victims in Modernist Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978), 189–230. For less condemnatory views, see Brener, Richard Wagner and the Jews; Laurence Dreyfus, “Hermann Levi’s Shame and Parsifal’s Guilt: A Critique of Essentialism in Biography and Criticism,” Cambridge Opera Journal 6 (1994): 125–45; Frithjof Haas, Hermann Levi: From Brahms to Wagner, trans. Cynthia Klohr (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2012).

returned to Germany in 1859. Haas, Hermann Levi, 22–25.

retire from leading an orchestra. Haas, Hermann Levi, 236–38.

came out in 1896. Under the title “Der Gaukler unserer lieben Frau,” Jugend: Münchner illustrierte Wochenschrift für Kunst und Leben 1.8 (February 22, 1896): 127–29. Levi’s authorship is not indicated in the pages where the tale is printed or in the index to the journal, but it is flagged (to cite only one example) by Haas, Hermann Levi, 263. The first authorized translation followed five years later, notably as the title story in a volume containing ten of France’s short stories: Der Gaukler unserer Lieben Frau und anderes, trans. Franziska Reventlow (Munich, Germany: Albert Langen, 1901), 1–13.

The main title of the periodical. The subtitle, translated into English, was Munich Illustrated Weekly for Art and Life. See Heinz Spielmann, Jugend 1896–1940: Zeitschrift einer Epoche. Aspekte einer Wochenschrift “Für Kunst und Leben” (Dortmund, Germany: Harenberg, 1988).

whom the conductor knew personally. Haas, Hermann Levi, 143.

The Mastersingers of Nuremberg. In the original German, the title is Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg.

mark corrections as she saw fit. Haas, Hermann Levi, 189, 191n10, citing Leviana, letter dated November 28, 1895, with a quotation from Mastersingers, Act 2.

Dancer of Our Blessed Lady. The German title is Der Tänzer uns’rer lieben Frau.

around the turn of the century. Hertz, Spielmannsbuch, 420. Hermann Hutter, Der Tänzer uns’rer lieben Frau: Nach dem gleichnamigen Gedicht von Wilhelm Hertz. Op. 17 (Leipzig, Germany: Luckhardt’s Musik-Verlag, 1899). On Hutter, see Jürgen Kraus, ed., Geborgen ruht die Stadt im Zauber des Erinnerns: Der Kaufbeurer Komponist Herman Hutter 1848-1926 und sein autobiographisches Vermächtnis, Schriftenreihe von Stadtarchiv und Stadtmuseum Kaufbeuren, vol. 3 (Kempten, Germany: Tobias Dannheimer, 1996).

Lancelot. “Lanzelot,” Opus 13 (1898). But note that the comparisons in a contemporary review are to Mendelssohn’s Loreley and Schumann’s Paradis und Peri: see Kraus, Geborgen ruht die Stadt, 18–19.

Reveille for the Nibelungen. “Nibelungen-Weckruf,” Opus 60 (verschollen): see Kraus, Geborgen ruht die Stadt, 23.

as it was understood by the nineteenth century. Danielle Buschinger, Das Mittelalter Richard Wagners, trans. Renate Ullrich and Danielle Buschinger (Würzburg, Germany: Königshausen & Neumann, 2007).

French songwriters. Steven Huebner, French Opera at the Fin de Siècle: Wagnerism, Nationalism, and Style (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 25–167 on Massenet (but without inclusion of Le jongleur de Notre Dame, because of its date early in the twentieth century).

Tristan and Isolde. 1856–59, premiere 1865.

Parsifal. 1865–82, premiere 1882.

cast an undeniably daunting shadow. On Wagner’s influence in France, see Léon Guichard, La musique et les lettres en France au temps du wagnérisme (Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1963); Paul du Quenoy, Wagner and the French Muse: Music, Society, and Nation in Modern France (Bethesda, MD: Academica Press, 2011).

polemical articles. Carlo Caballero, review of Huebner, French Opera at the Fin de Siècle, Cambridge Opera Journal 12 (2000): 81–89, at 87.

satirically anti-Gallic tirade. Richard Wagner, “Eine Kapitulation,” trans. W. Ashton Ellis, “A Capitulation,” in Richard Wagner, Prose Works, vol. 5, Actors and Singers (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1896), 5–33.

eyewitness account. Steven Huebner, “Massenet and Wagner: Bridling the Influence,” Cambridge Opera Journal 5.3 (1993): 223–38.

Who can render us that pure love. Claude Debussy, “M. Claude Debussy et Le martyre de saint Sébastien (Interview par Henry Malherbe),” in idem, Monsieur Croche et autres écrits (Paris: Gallimard, 1926), 302; 2nd ed. (Paris: Gallimard, 1987), 323–25, at 324, repr. in idem, Debussy on Music: The Critical Writings of the Great French Composer Claude Debussy, ed. and trans. Richard Langham Smith (New York: A. A. Knopf, 1977), 247–49, at 247: “Qui nous rendra le pur amour des musiciens pieux des anciennes époques? . . . Qui recommencera le pauvre et suave sacrifice du petit jongleur, dont l’histoire attendrissante nous est demeurée?”

defending the cathedrals of his homeland. Marcel Proust, “La mort des cathédrales,” Le Figaro, August 16, 1904, repr. in idem, Pastiches et mélanges (1919). The best edition is in Marcel Proust, Contre Sainte-Beuve (Paris: Gallimard, 1971), 146–47, with notes at 770–72.

Twilight of the Gods. In the original German, Die Götterdämmerung.

Tannhäuser

In The Education of Henry Adams. Henry Adams, The Education of Henry Adams (henceforth EHA), chap. 23, “Silence (1894–1898),” in idem, Novels, Mont Saint Michel, The Education, ed. Ernest Samuels and Jayne N. Samuels (New York: Library of America, 1983), 1049: “This amusement could not be prolonged, for one found oneself the oldest Englishman in England, much too familiar with family jars better forgotten, and old traditions better unknown. No wrinkled Tannhäuser, returning to the Wartburg, needed a wrinkled Venus to show him that he was no longer at home, and that even penitence was a sort of impertinence. . . . From time to time Hay wrote humorous laments, but nothing occurred to break the summer-peace of the stranded Tannhäuser, who slowly began to feel at home in France as in other countries he had thought more homelike.” In letters, he mentions hearing in Bayreuth Das Rheingold (The Rhinegold), Die Walküre (The Valkyrie), and Die Götterdämmerung (Twilight of the Gods), the first, second, and fourth, respectively, in Wagner’s cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelungen). For references to these and other Wagnerian operas, see Henry Adams, The Letters of Henry Adams (henceforth LHA), ed. J. C. Levenson et al., 6 vols. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982–1988), 5: 267–72.

a study on the legend of Tannhäuser. Gaston Paris, “La légende du Tannhäuser,” Revue de Paris 5.2 (1898): 307–25, repr. in idem, Légendes du Moyen Âge (Paris: Hachette, 1903), 111–45. In the meantime between the debut and the Parisian revival, the story was not allowed to languish. In 1866, a lyrical and dramatic poem by the English writer Algernon Charles Swinburne was published on the theme. In translation, its Latin title of “Laus Veneris” means “Praise of Venus,” referring to the Roman goddess of love. Later, the same theme became the object of Aubrey Beardsley’s attention. He worked ceaselessly but ineffectually on a novel that was originally to have been entitled The Story of Venus and Tannhäuser, but that began to appear in print only in 1896, in expurgated form, under the title Under the Hill. Beardsley’s version increases the sexual charge of the story.

a nobleman. Specifically, a landgrave.

Henry Adams became well acquainted with the Wartburg. Letter to Charles Francis Adams Jr., April 22, 1859, in LHA, 1: 34–39, at 36: “The old Wartburg above it is covered with romance and with history until it’s as rich as a wedding-cake.”

the Sleeping Beauty castle in Disneyland. Martha Bayless, “Disney’s Castles and the Work of the Medieval in the Magic Kingdom,” in The Disney Middle Ages: A Fairy Tale and Fantasy Past, ed. Tison Pugh and Susan Aronstein (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 39–56.

Pierrefonds. On the relationship between the two castles, see Jürgen Strasser, Wenn Monarchen Mittelalter spielen: Die Schlösser Pierrefonds und Neuschwanstein im Spiegel ihrer Zeit, Stuttgarter Arbeiten zur Germanistik, vol. 289 (Stuttgart, Germany: Hans-Dieter Heinz, 1994).

Viollet-le-Duc and his successors. For the restorer’s own words, see Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, Description et histoire du Château de Pierrefonds, 11th ed. (Paris: A. Morel, 1883). For comparative analysis of the French chateau and the German construction, see Strasser, Wenn Monarchen Mittelalter spielen.

The Medievalesque Oeuvre of Jules Massenet

The composer has captured. “Le jongleur de Notre Dame,” The Musical Standard (June 30, 1906): 400–1, at 400.

Massenet achieved a similar status. The most recent general appreciation of his career would be Christophe Ghristi and Mathias Auclair, La belle époque de Massenet (Montreuil, France: Gourcuff Gradenigo, 2011).

Academy of Fine Arts. In French, Académie des Beaux-Arts, founded in 1795.

medievalizing revival. For a capsule view of Massenet’s medievalism, see Didier Van Moere, “Massenet,” in La fabrique du Moyen Âge au XIXe siècle: Représentations du Moyen Âge dans la culture et la littérature françaises du XIXe siècle, ed. Simone Bernard-Griffiths et al., Romantisme et modernités, vol. 94 (Paris: Honoré Champion, 2006), 1077–84.

In the Midst of the Middle Ages. Chap. 23, “En plein Moyen Âge.”

The Virgin. The légende sacrée, La Vierge.

French libretto. The libretto is by Charles Grandmougin.

a libretto in French. The libretto is by Louis Gallet, Édouard Blau, and Adolphe d’Ennery. The opera premiered at the Paris Opera on November 30, 1885.

five-act tragicomedy. First performed and published in 1637.

librettists. Alfred Blau and Louis de Gramont.

Huon de Bordeaux. For a review by an author who was himself caught up in the medievalizing trend of this decade, see Marcel Schwob, “Esclarmonde,” Phare de la Loire, May 18, 1889, repr. in idem, Chroniques, ed. John Alden Green, Histoire des idées et critique littéraire, vol. 195 (Geneva: Droz, 1981), 52–55.

one of the writers. The librettist in question was Édouard Blau.

its composer was singled out officially. On its place within the overall presentation of music at the Exposition Universelle, see Annegret Fauser, Musical Encounters at the 1889 Paris World’s Fair, Eastman Studies in Music, vol. 32 (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2005). On its reception in general, see Annegret Fauser, ed., Jules Massenet, Esclarmonde: Dossier de presse parisienne (1889), Critiques de l’opéra français du XIXème siècle, vol. 12 (Weinsberg, Germany: L. Galland, 2001); she discusses the opening at p. v.

comprising a prologue and three acts. The libretto was based on a play by Paul-Armand Silvestre and Eugène Morand that had been performed first in 1891.

as related in the Italian prose of Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron. See the tenth, and final, novella of the tenth day.

Massenet’s version. Grisélidis premiered on November 21, 1901, at the Opéra Comique in Paris.

various images. Especially the watercolor Love Among the Ruins, which was first exhibited in 1873 and was recreated as an oil painting in 1894 after the destruction of the earlier work.

a triptych of medievalesque operas. Stefan Schmidl, Jules Massenet: Sein Leben, sein Werk, seine Zeit, Serie Musik Atlantis-Schott, vol. 8310 (Mainz, Germany: Schott, 2012), 90–95 presents the three operas explicitly as such.

Amadis. Written by the man of letters, Jules Claretie, who was elected to the French Academy in 1888.

Spanish chivalric romance. It is entitled Amadís de Gaul.

as Grisélidis had been. The parallels between the two operas as musical miracle plays were not lost on Massenet’s near-contemporaries. For example, see the review in Nation 90.2326 (January 27, 1910): 95–96.

even before the musical drama was accepted for performance. Ronald Crichton, “Massenet and After,” Musical Times 112 (February 1971): 132.

the ruler of the principality had been an enterprising benefactor. Jules Massenet, Mes souvenirs: À mes petits-enfants, ed. Gérard Condé (Paris: Plume, 1992), 243; T. J. Walsh, Monte Carlo Opera 1879–1909 (Dublin, Ireland: Gill and Macmillan, 1975), 148.

a tidy sum. The precise amount was 20,000 francs: see Walsh, Monte Carlo Opera 1879–1909, 151.

going back to 1842. In this year, Henri Heugel’s father and partner moved into quarters on Rue Vivienne occupied by Le Ménestrel, a periodical devoted to music that they had acquired.

The Tall Tale of the Libretto

In his autobiography. See Jules Massenet, My Recollections, trans. H. Villiers Barnett (Boston: Small, Maynard, 1919), 231–35 (in the chapter headed “In the Midst of the Middle Ages”). Compare Raymond de Rigné, Le disciple de Massenet, 5 vols. (Paris: La renaissance universelle, 1921), 1: 12. For analysis of the flaws in Massenet’s account, see Demar Irvine, Massenet: A Chronicle of His Life and Times (Portland, OR: Amadeus, 1994), 229–30.

frets over taking nourishment within the community. Le jongleur de Notre-Dame, lines 108–10, 125–28, ed. Paul Bretel, Traductions des classiques du Moyen Âge, vol. 64 (Paris: Honoré Champion, 2003), 82.

he is described. Le jongleur de Notre-Dame, lines 234–36, ed. Bretel, 86.

one Maurice Léna. For Léna’s recollections, see “Massenet (1842–1912),” Le Ménestrel 4422, 83.4 (January 28, 1921): 33–34. For recollections by another contemporary, see Raymond de Rigné, “Souvenirs sur Massenet,” Le Mercure de France 32.545 (March 1, 1921): 351, 362–63, 369–70.

professor of rhetoric. He taught first at the University of Lyon and later in Paris.

librettos for various composers. Léna also composed texts for such stage works as Émile Jaques-Dalcroze’s 1908 Les jumeaux de Bergame (The twins of Bergamo), based on an eighteenth-century play; Charles-Marie Widor’s 1924 Nerto; and Philippe Gaubert’s 1927 Nalïa.

The Farce of the Vat. In French, La farce du cuvier, by Gabriel Dupont.

The Damnation of Blanchefleur. In French, La damnation de Blanchefleur: Miracle en deux actes, by Henry Février.

In the Shadow of the Cathedral. In French, Dans l’ombre de la cathédrale, by Georges Hüe.

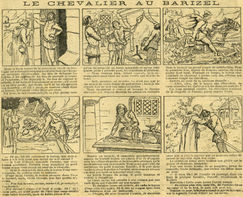

Knight of the Barrel. In French, Le chevalier au Barizel: légende dramatique en trois parties, music by Charles Pons ([no place]: Imprimerie E. Desfossés, [no date]). Other versions of a story with the same title are attested in French in the second decade of the twentieth century. The free German adaptation from the same period is entitled Der Ritter mit dem Fäßchen. The story was adopted as a modest cartoon strip in the anonymous “Le chevalier au Barizel,” Les trois couleurs 6.230 (May 1, 1919), 3 (see Fig. n.1).

Fig. n.1 Comic strip of “Le Chevalier au Barizel.” Published in Les Trois Couleurs: épisodes, contes et romans de la grande guerre 6.230 (May 1, 1919), 3.

An obituary. Le Ménestrel (April 6, 1928), quoted and translated by Terence Noel Needham in “‘Le Jongleur est ma foi’: Massenet and Religion as Seen through the Jongleur de Notre Dame” (PhD dissertation, Queen’s University Belfast, 2009), 90–91, at n64.

Elsewhere. Henry T. Finck, Massenet and His Operas (New York: John Lane, 1910), 91.

portrays the writer. Massenet, Mes souvenirs, 240.

During the visit. Léna, “Massenet (1842–1912),” 34.

Massenet pretends. Massenet, My Recollections, 234–35.

Three manuscripts. Jean-Christophe Branger, “Massenet et ses livrets: Du choix de sujet à la mise en scène,” in Le livret d’opéra au temps de Massenet: Actes du colloque des 9–10 novembre 2001, Festival Massenet, ed. Alban Ramaut and Jean-Christophe Branger, Centre interdisciplinaire d’études et de recherches sur l’expression contemporaine: Travaux, vol. 108/Musicologie, cahiers de l’Esplanade, vol. 1 (Saint-Étienne, France: Publications de l’Université de Saint-Étienne, 2002), 251–81, at 269–70.

The Middle Ages of the Opera

Did you ever hear of this juggler. “Fascinating Legend Revived in Massenet’s Coming Opera,” New York Times, August 16, 1908.

delightful vignette in the primitive manner. Léna, “Massenet (1842–1912),” 33–34: “délicieux tableau de primitif.”

his thought. Rigné, “Souvenirs sur Massenet,” 348.

The Red and the Black. In French, Le Rouge et le Noir: Chronique du XIXe siècle.

between the Saône and the Loire rivers. Near Mâcon.

the monastery most emblematic of Cistercianism. Adriaan Hendrik Bredero, Cluny et Cîteaux au douzième siècle: L’histoire d’une controverse monastique (Amsterdam: APA-Holland University Press, 1985).

the institution acquired melancholy fame. Janet Marquardt, From Martyr to Monument: The Abbey of Cluny as Cultural Patrimony (Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars, 2007).

became an object of fascination. Elizabeth Emery, “Le visible et l’invisible: Cluny dans la littérature française du XIXe siècle,” in Cluny après Cluny: Constructions, reconstructions et commémorations, 1720–2010. Actes du colloque de Cluny, 13–15 mai 2010, ed. Didier Méhu (Rennes, France: Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2013), 339–52.

All Souls’ Day. On November 2.

National Museum of the Middle Ages. In French, Musée national du Moyen Âge.

American architectural historian. Kenneth John Conant conducted the archaeological investigations at Cluny from 1928 to 1950, under the auspices of the Mediaeval Academy of America.

Even the sounds. Jean-Pierre Bartoli, “Le langage musical du Jongleur de Notre-Dame de Massenet: Historicisme, expression religieuse et système musico-dramatique,” in Opéra et religion sous la IIIe République, ed. Jean-Christophe Branger and Alban Ramaut, Centre interdisciplinaire d’études et de recherches sur l’expression contemporaine: Travaux, vol. 129/Musicologie, cahiers de l’Esplanade, vol. 4 (Saint-Étienne, France: Publications de l’Université de Saint-Étienne, 2006), 305–33.

the score has the exquisite colors of stained glass. Ghristi and Auclair, La belle époque de Massenet, 160 (“La partition a d’exquises couleurs de vitrail”).

Léna reported. Massenet, Mes souvenirs, 240n3 (with reference to Léna in Le Ménestrel of February 4, 1921).

other French composers. See Schmidl, Jules Massenet, 94, on Vincent d’Indy’s opera Fervaal and Gabriel Pierné’s symphonic poem L’an mil (The year 1000), both written in 1897.

the artist told the poor fellow. Massenet, Mes souvenirs, 248; idem, My Recollections, 282.

is said to have satisfied the medievalist. Massenet, My Recollections, 241.

music of the theater. Jean-Christophe Branger, “Introduction,” in idem and Ramaut, Opéra et religion sous la IIIe République, 9–36, at 10, with reference to Camile Bellaigue, “La musique d’Église au théâtre,” La Tribune de Saint-Gervais 11.1 (January 1905): 4–13.

Solesmes. In the département of Sarthe near Sable.

school of singers. Known formally in Latin as the schola cantorum.

rhapsody in brew. Katherine Bergeron, Decadent Enchantments: The Revival of Gregorian Chant at Solesmes (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1998).

The first perspective he isolated. G. K. Chesterton, “History Versus the Historians” (1908), in idem, Lunacy and Letters, ed. Dorothy Collins (New York: Sheed & Ward, 1958), 128–33, at 130.

The historical music movement. Siegmund Levarie, “Henry Adams, Avant-Gardist in Early Music,” American Music 15 (1997): 429–45.

melismas. In reference to Gregorian chant, this technical term denotes a group of different notes sung to one syllable (such as the final letter a in the word alleluia). The contrast is coloratura, in which each syllable has its own note in a melody.

characteristically medieval. Arthur Pougin, quoted in Esther Singleton, A Guide to Modern Opera (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1909), 233.

chalumeau. A woodwind instrument that looks like a recorder but has a mouthpiece like a clarinet.

as the viol was viewed. Harry Danks, “The Viola d’Amore,” Music & Letters 38.1 (1957): 14–20.

Bertha of the Big Foot. Sometimes called Bertha Broadfoot, she is known in modern French as Berte aux grands pieds. For a translation, see Adenet le Roi, Bertha of the Big Foot (Berte as grans pié): A Thirteenth-Century Epic, trans. Anna Moore Morton, Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, vol. 417 (Tempe, AZ: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2013).

at least by mentioning them. Thus, we hear about the “toper’s creed.” This would be an oenophile’s deformation of the profession of faith known as the Nicene Creed, which begins “We believe in one God, the Father Almighty.” We also learn about the Te Deum of hippocras, a sweetened and spiced wine. This pseudoliturgy plays upon the early Christian hymn of praise often called the Ambrosian hymn, with the incipit “We praise thee, O God.” Another is the Gloria of the red-faced, alluding, of course, to the flushed complexion caused by hard drinking. The Latin refers to the so-called angelic hymn that opens with the Latin words “Glory to God in the highest” (Gloria in excelsis Deo).

One would search in vain. The foundational repositories of such medieval parodic material remain, for the Latin, Paul Lehmann, Die Parodie im Mittelalter, 2nd ed. (Stuttgart, Germany: A. Hiersemann, 1963), and for the French, Eero Ilmari Ilvonen, Parodies de thèmes pieux dans la poésie française du Moyen Âge: Pater–Credo–Ave Maria–Laetabundus (Paris: Honoré Champion, 1914).

their medieval antecedents. The French had no direct equivalent of Wine, Women, and Song: Medieval Latin Students’ Songs by John Addington Symonds. The 1884 bestseller etched at least its title phrase upon the consciousness of the English-speaking world. All the same, France had its own oft-reprinted 1843 anthology of Popular Latin Poetry from before the Twelfth Century. See Édélestand Du Méril, Poésies populaires latines antérieures au douzième siècle (Paris: Brockhaus et Avenarius, 1843). The songs that are inevitably absorbed into such collections have had an abiding impact on high culture in the Anglophone world. For confirmation we need look no further than the 1949 book entitled The Goliard Poets: Medieval Latin Songs and Satires, by George F. Whicher, a friend of the American poet Robert Frost. In another branch of European literary and musical tradition, the Carmina Burana cantata of the German composer Carl Orff (based on the extensive medieval anthology conventionally known by the same name) includes tavern poems that reach a mass audience.

Play of Robin and Marion. In French, Jeu de Robin et Marion.

Adam de la Halle. Known also as Adam le Bossu.

at least twice. First, in 1872 it was put on in Paris in its entirety, adapted by Jean-Baptiste Weckerlin and performed at the Comédie française by a company from the Opéra Comique: see Julien Tiersot, Sur le jeu de Robin et Marion d’Adam de la Halle (XIIIe siècle) (Paris: Fischbacher, 1897), 5–6. Then, in 1896 it was performed in Arras, this time produced as modernized by Tiersot, a student of Massenet’s, and Emile Blémont. In the same year, a philologist published a popularization of the play in modernized form. See Adam le Bossu, Le Jeu de Robin et Marion, ed. Ernest Langlois (Paris: A. Fontemoing, 1896). His translations retained their appeal into the twentieth century, with reprintings, for example, in 1923 and 1933.

Instead, he moves on. Pierre Jonin, “Ancienneté d’une chanson de toile? La Chanson d’Erembourg ou la Chanson de Renaud?,” Cahiers de civilisation médiévale 28.112 (octobre-décembre 1985): 345–59.

Sage Wisdom

Legend of the Sage. In English translation, the herb has also been called Sage-Plant and Sage-Bush. In Mark Schweizer, words and music, The Clown of God: A Christmas Chancel Drama for Children’s Choir (Hopkinsville, KY: St. James Music Press, 1996), 10–11, Massenet’s sage plant is Americanized into the sagebrush familiar from cowboy westerns, which in actuality belongs to a separate genus.

It is sung. “Légende de la sauge,” act 2, scene 4.

Legendary Feasts. For the quotation, see Musical Standard (June 30, 1906): 401. The book is Amédée de Ponthieu, Les fêtes légendaires (Paris: Maillet, 1866).

illustrated French-language weeklies. First was La semaine de Suzette 37.13 (October 24, 1946), cover (for illustration). This “Suzie’s Weekly,” to put its title into English, appeared from 1905 (the year in which Church and State were legally separated in France) through 1960. On it, see Jacques Tramson, “Presse enfantine française,” in Dictionnaire du livre de jeunesse: La littérature d’enfance et de jeunesse en France (henceforth DLJ), ed. Isabelle Nières-Chevrel and Jean Perrot (Paris: Éditions du Cercle de la Librairie, 2013), 764–73, at 769; Marie-Anne Couderc, “Semaine de Suzette, La,” in DLJ, 883–84. Then came Bernadette: Illustré catholique des fillettes, n.s. 8 (January 26, 1947), cover (for illustration) and 124 (for text). The latter publication was thus titled after the Marian visionary of Lourdes by this name. On it, see Catherine d’Humières, “Bernadette,” in DLJ, 82–83. On such religious publications, see Michel Manson, “Religion et littérature de jeunesse,” in DLJ, 793–96, at 795.

Applied to this narrative. The original Latin legendum was used first as a verbal adjective, and later as a noun meaning “that which is to be read” in the liturgical office.

Such narratives were read aloud. Hippolyte Delehaye, The Legends of the Saints, trans. Donald Attwater (New York: Fordham University Press, 1962), 8.

composers, too. Thus, in 1864–1865, Gabriel Fauré set to music as a work for mixed chorus and piano (or organ) a French translation of a Medieval Latin hymn, though under the somewhat misleading title Cantique de Jean Racine (Canticle of Jean Racine). The text by the seventeenth-century poet paraphrases a pseudo-Ambrosian hymn with the incipit “Consors paterni luminis.” To take another example, in 1910 Claude Debussy composed voice-and-piano music for three “ballades” by the French poet and vagabond François Villon.

contemporary critics. Richard Alexander Streatfeild, The Opera: A Sketch of the Development of Opera, 3rd ed. (Philadelphia, PA: J. B. Lippincott, 1907), 248: “Rarely has Massenet written anything more delightful than this exquisite song, so fresh in its artful simplicity, so fragrant with the charm of mediaeval monasticism.” Another raved: “In the legend related by Boniface to Jean the composer is at his best.” See “Massenet’s ‘Le Jongleur de Notre-Dame,’” The Athenaeum 4034 (February 18, 1905): 218.

Juggling Secular and Ecclesiastical

A surprising thing. Jean d’Arvil, on reviews of Massenet’s Jongleur in the popular press, June, 1904. Quoted in Rigné, Le disciple de Massenet, 1: 49.

went so far as to observe. He made the remark in reference to passages in his oratorio-like choral “sacred drama” on Mary Magdalene, Marie-Magdeleine, with a text in verse by Louis Gallet.

I don’t believe in all this. Léon Vallas, Vincent d’Indy (Paris: Albin Michel, 1946), 195: “Oh! Vous pensez bien que toutes ces bondieuseries, moi, je n’y crois pas. . . . Mais le public aime ça, et nous devons toujours être de l’avis du public.” For translations, see James Harding, Massenet (London: Dent, 1970), 49; Michael White and Elaine Henderson, Opera and Operetta (London: HarperCollins, 1997), 208.

the writer assured his readers. Fernand de La Tombelle, “Massenet, musician religieux?,” La Tribune de Saint-Gervais: Bulletin mensuel de la Schola Cantorum 18 (1912): 285–88, at 288: “You will recognize that he loved religion, honored the Church, adored the Virgin as much as he respected the priest. His faith—and I affirm that he had it—was sensitive, poetic, naïve, but real, and when he had the jongleur dance in the silence of the abbatial church, rest assured that more than once he believed that he was putting himself on stage in offering the Holy Virgin ‘an opera,’ since it is that that he knew to make!”

could have been slighted either way. For revealing glimpses into the tensions at the time, see Proust, “La mort des cathédrales,” 3–4.

goes by the name of verismo. Translated into English, verismo would be literally “true-ism.”

The Girl from Navarre. In French, La Navarraise.

nurtured a genuine predilection. Rigné, “Souvenirs sur Massenet,” 355–56: “‘Est-il vrai que Massenet affectionait particulièrement Le Jongleur?’ Demanda Yvonne. ‘Massenet préférait toujours sa dernière pièce. Cependant, il eut une réelle predilection pour celle-là. Il a lancé un jour cette boutade: “Le Jongleur, amis, ce n’est qu’une carte de visite dans la vie d’un musicien!”’”

because he had given the most of himself to it. Combat, April 7, 1954: “Le Jongleur est mon oeuvre préférée parce que c’est ici que je me suis le plus donné.” Also quoted by Needham, “Le Jongleur est ma foi,” 1–2.

Thérèse is my heart. Charles Bouvet, Massenet: Biographie critique, illustré de douze planches hors texte (Paris: Henri Laurens, 1929), 108. Quoted in the original French (and taken as the title of his dissertation) by Needham, “Le Jongleur est ma foi,” 1. The source is a document reproduced in Rigné, Le disciple de Massenet, 1: 60.

a wooden image of Mary. Massenet, My Reflections, 52.

Raphael’s Sistine Madonna. The same painting by the Italian artist had made a strong impression on Clover Adams, but probably not for the same reasons. Raphael was received much differently in the United States than in France. See Martin Rosenberg, Raphael and France: The Artist as Paradigm and Symbol (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995).

the photograph “remained lighted all night.” Irvine, Massenet, 183; cited by Needham “Le Jongleur est ma foi,” 81.

gaining the support of the Virgin. Massenet, My Recollections, 232: “The most sublime of women, the Virgin was bound to sustain me in my work, even as she showed herself charitable to the repentant jongleur.”

the marvelous cathedrals arose. Letter to the composer and pianist Paul Lacombe, Venice, May 23, 1873, Carcassonne, Bibliothèque municipale, cited by Branger, “Introduction,” 21n33.

blue Madonnas, pink Sacred Hearts. Madeleine Ochsé, Un art sacré pour notre temps, Je sais, je crois, vol. 132 (Paris: Fayard, 1959), 14; quoted by Claude Savart, “A la recherche de l’art dit de Saint-Sulpice,” Revue d’histoire de la spiritualité 52 (1976): 263–82, at 282: “Blue Virgins, pink Sacred Hearts, chocolate-brown Saint Josephs belonged for me to this enchanted world of Catholic childhood in which the heavens visit the earth without ado.”

it will emit a note. William R. Lethaby, Architecture: An Introduction to the History and Theory of the Art of the Building, Home University Library of Modern Knowledge, vol. 39 (London: Williams and Norgate, 1912), 201: “The ideals of the time of energy and order produced a manner of building of high intensity, all waste tissue was thrown off, and the stonework was gathered up into energetic functional members. These ribs and bars and shafts are all at bowstring tension. A mason will tap a pillar to make its stress audible; we may think of a cathedral as so ‘high strung’ that if struck it would give a musical note.”

The food is good in the monastery. “La cuisine est bonne au couvent / Moi qui ne dînais pas souvent / Je bois bon vin, je mange viandes grasses. / Jour glorieux!”

glory may be wrapped up in religion. “La Vierge aujourd’hui monte aux cieux, / Et pour elle on répète un cantique de grâces. / Avec tristesse / Un cantique en latin!” (“The Virgin today ascends to heaven, and for her her people say over and over a canticle of thanksgiving. [Sorrowfully.] A canticle in Latin!”)

clerical in social station. The classic study is Herbert Grundmann, “Litteratus-illitteratus,” Archiv für Kulturgeschichte 40 (1958): 1–65.

verses from the hymn to the Virgin. The passage appears at the opening of the second act. The Latin of the hymn goes back ultimately to an acrostic on the “Ave Maria”: see Guido Maria Dreves, ed., Analecta hymnica medii aevi, 55 vols. (Leipzig, Germany: Fues’s Verlag, R. Reisland, 1886–1922), 15: 115–23, at 115 (no. 94, strophe 1).

a tag from Virgil. Georgics 2.496, “agitans discordia fratres.”

Massenet’s measured mockery. Louis Bethléem et al., Les opéras, les opéras-comiques et les opérettes (Paris: Revue des lectures, 1926), 334, discussed by Branger, “Introduction,” 16–17.

a brief text. René Brancour, Massenet (Paris: Félix Alcan, 1922), 56: “Souvenez-vous devant Dieu de MASSENET / Compositeur de musique, Né à Saint-Etienne le 12 mai 1842, Mort à Paris le 14 août 1912. / Le Jongleur est ma foi / Requiescat in pace.”

served in the National Guard. “Autobiographical Notes by the Composer Massenet,” Century Magazine 45 (November 1892): 122–26, at 124.

romantic opera. In French, the terms are respectively “opéra romanesque,” “comédie lyrique,” “opéra légendaire,” “opéra féerique,” and “conte lyrique.”

Eve: Mystery Play. In French, Éve: mystère, to a libretto by the prolific librettist Louis Gallet.

In the Middle Ages. L’Echo de Paris, February 19, 1902, quoted by Needham, “Le Jongleur est ma foi,” 105 (my translation).

up to the middle of the sixteenth century. Among scholars, the philologist Gaston Paris had earned himself everlasting association with the miracle, thanks to the forty specimens of the genre he coedited in the Miracles of Our Lady, by Characters. See Gaston Paris, ed., Miracles de Nostre Dame par personnages, 8 vols. (Paris: Firmin Didot, 1876–1893), in collaboration with Ulysse Robert.

the hood does not make the monk. Twelfth Night; or, What You Will, 1.5.56, “Cucullus non facit monachum,” in The Riverside Shakespeare (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1974), 412.

the mere outward trappings of monkishness. Thesaurus proverbiorum medii aevi: Lexikon der Sprichwörter des romanisch-germanischen Mittelalters, 13 vols. (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1995–2002), 7: 70–72 (Kleid 2.3.2.2 Kleider machen keinen zum Mönch, Geistlichen, Einsiedler oder Heiligen).

a statue served the purpose instead. See Needham, “Le Jongleur est ma foi,” 2.

Blessed are the humble. Compare Matthew 5:5–15.

a French reader. Caecilia Pieri, Il était une fois, Contes merveilleux, vol. 1 (Paris: Flammarion, 2004), 89 (introduction), 101 (supporting instructional material).

Affected simplicity. The passage as a whole is quoted from Brancour, Massenet, 79 (my translation). It incorporates La Rochefoucauld, Moral Maxims and Reflections (1665–1678), no. 289, “La simplicité affectée est une imposture delicate.”

deliberately for sake of the Virgin. “But to please Mary, I remain simple.”

another quality that has been discerned. Brancour, Massenet, 78 (“Jean le jongleur, un peu plus naïf tout de même que nature”).

A reviewer commented. Le Figaro, February 19, 1902: quoted and cited by Needham, “Le Jongleur est ma foi,” 98.

Thanks be to God! In the original, “Deo gratias! / Feliciter! / Amen.” A review of the Parisian premiere of Le jongleur de Notre Dame quotes the composer as having said: “The Benedictines had a practice of concluding their works in this way; it was their cry of thanks to God and expression of their submission to a higher will. I am like them: Go to God!” See Le Temps, May 10, 1904.

James Bond novels. For example, in Casino Royale, Never Say Never Again, and GoldenEye.

its first night. The role of Jean was created by Adolphe (Alphonse) Maréchal, a tenor of Belgian nationality (see Fig. n.2). The role was originally meant for Albert Vaguet. Boniface was performed by Maurice Renaud (see Fig. n.3), the prior by Gabriel-Valentin Soulacroix, both French baritones. The monks were played by Berquier, Juste Nivette, Grimaud, and Cuperninck, and the angels by Marguerite de Buck and Mary Girard. The settings were designed by Lucien Jusseaume. See Walsh, Monte Carlo Opera 1879–1909, 152.

Fig. n.2 Adolphe Maréchal as Jean in Massenet’s Le jongleur de Notre-Dame. Photograph, 1904. Photographer unknown. Published in Musica (June 1904).

Fig. n.3 Maurice Renaud. Photograph by Herman Mishkin, 1912.

amid the spectators’ deafening whoops. Walsh, Monte Carlo Opera 1879–1909, 156.

Salle Garnier. Designed by the architect Charles Garnier, the theater named after him was built in a half year to open in 1879. It stands on the former site of entertainment rooms of the casino. Its interior is an impressive square, twenty meters on a side, with a ceiling nineteen meters high.

the campaign to peddle Monaco. A color lithograph from 1897, in the full splendor of art nouveau, constitutes a stunning benchmark of this promotional effort. It was the doing of Alphonse Mucha. A highly versatile artist, he worked across many media but merited greatest acclaim for his advertising posters. Ethnically Czech, he gained stature as the father of Parisian art nouveau.

memorialized for philatelists. On the centenary of the Salle Garnier opera in 1979, the principality issued five commemorative postage stamps to honor operas that had premiered there, together with one to celebrate the building itself and its architect. Two were by Massenet: Le jongleur de Notre Dame (1.00 franc) and Don Quichotte (1.50 franc). The others were Louis Ganne’s Hans, le joueur de flûte (1906, 1.20 franc), Maurice Ravel’s L’Enfant et les sortilèges (1925, 2.10 franc), and Arthur Honegger and Jacques Ibert’s L’Aiglon (1937, 1.70 franc). The opera house stamp had the highest denomination (3.00 franc). The stamps are designated as Yvert 1175–80, referring to item numbers in the annual Catalogue de timbres-poste (Amiens, France: Yvert, commencing in the 1930s).

he himself epitomized the era. Consider the title of José Bruyr, Massenet: Musicien de la belle époque (Lyon, France: Éditions et imprimeries du Sud-Est, 1964).

I heard then Le jongleur! Rigné, Le disciple de Massenet, 1: 1, 2, and (here) 4.

a few other European cities. Other first nights included Hamburg, Germany, September 24, 1902; Brussels, Belgium, November 25, 1904; and Geneva, Switzerland, November 29, 1904. A description of the first night in Monte Carlo can be read in Irvine, Massenet, 240.

we can hear later ones. Malibran Music, CDRG 156 (compact disc).

more than other such famous musical dramas of the period. Irvine, Massenet, 254.

the year was an especially good one. In the same year it opened in Brussels and Geneva.

staged on four continents. In 1905, Le jongleur de Notre Dame was performed in (to use present-day names) Algiers, The Hague, Milan, and Berlin; in 1906 in Lisbon and London; in 1908 in New York; in 1911 in Buenos Aires, and both Graz and Vienna in Austria; in 1912 in Montreal, Zagreb, and Limberg, Austria; in 1914 in Prague; in 1915 in Rio de Janeiro; in 1919 in Barcelona; and in 1920 in Ljubljana, Slovenia. For the fullest information on places and dates of premieres, see Alfred Loewenberg, Annals of Opera, 1597–1940, 3d ed. (Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield, 1978), columns 1239–40. At first, the libretto was controlled jealously by the publisher. After the original French, translations appeared in German, Italian, and other languages. See, for example, Jules Massenet and Maurice Léna, Der Gaukler unserer lieben Frau: Mirakel in drei Akten, trans. Henriette Marion (Paris: Au Ménestrel, Heugel, 1902), and Le jongleur de Notre-Dame (Il giullare di Nostra Signora): Miracolo in tre atti, trans. Biante Montelioï (Paris: Au Ménestrel, Heugel, 1905).

Jean, Bénédictine, and Selling Gothic

Bénédictine. Among bartenders and mixologists, the beverage may be known best today with its name reduced to a mere initial, in the pairing of Bénédictine and brandy called “B & B.”

public limited company. In French, société anonyme.

facilities designed to fulfill a dual function as tourist attractions. Lynn F. Pearson, Built to Brew: The History and Heritage of the Brewery (Swindon, UK: English Heritage, 2014).

enchantment of technology. See Alfred Gell, “The Technology of Enchantment and the Enchantment of Technology,” in Anthropology, Art and Aesthetics, ed. Jeremy Coote and Anthony Shelton (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992), 40–63.

The distillery served. On the museum and collection as constituted in the late nineteenth century, see Distillerie de la liqueur Bénédictine de l’abbaye de Fécamp: Musée, catalogue illustré de nombreux dessins de H. Scott gravés par Bellanger avec préface et notice historique sur l’abbaye de Fécamp (Fécamp, France: L. Durand, 1888).

Palais Bénédictine. The French name implies simultaneously what in English would require both “Benedictine Palace” (for the monastic order) and “Bénédictine Palace” (for the liqueur brand). Although the original building was destroyed in a fire in 1892, the rebuilding of an expanded replacement was undertaken in the following year and completed in 1900.

his experiments with one of these elixirs. Jean-Pierre Lantaz, Bénédictine, d’un alambic à cinq continents (Luneray, France: Bertout, 1991), 251.

endorsements of the cordial’s potability. The results were ten lithographs of “Contemporary Celebrities and Bénédictine.” The set was printed in color on stiff cards and distributed unbound but in a book-like case, with a string to keep the contents secure. The newsmakers ranged from the aviator Alberto Santos-Dumont through the actor Albert Brasseur to Sem himself.

I am sure that the Benedictines. Sem (Georges Goursat), Célébrités contemporaines et la Bénédictine (Paris: Devambez, 1909), 16 x 24 cm: “Je suis certain que les Bénédictins au temps du ‘Jongleur de Notre Dame’ buvaient de l’exquise Bénédictine comme nous en avons heureusement encore aujourd’hui.”

everything seemed to taste better. We have seen the brew promoted already: an engraving of Raoul Gunsbourg with a few bars of his 1909 opera Le vieil aigle (The old eagle) bears at the bottom, above his autograph, the caption “Dream of it and drink some Mariani” (see Fig. 1.73).

cutting-edge photomechanical processes. Willa Z. Silverman, The New Bibliopolis: French Book Collectors and the Culture of Print, 1880–1914 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008), 27.

The painter. The artist was Guillaume Dubufe.

Salettine. This liqueur was peddled by Maximin, one of the children who had claimed to experience the vision at La Salette. He put his name and a picture of himself on the label. See Ruth Harris, Lourdes: Body and Spirit in the Secular Age (London: Penguin, 1999), 252; Lisa J. Schwebel, Apparitions, Healings, and Weeping Madonnas: Christianity and the Paranormal (New York: Paulist Press, 2004), 122; Victor Witter Turner and Edith L. B. Turner, Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture, Lectures on the History of Religions, New Series, vol. 11 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1978), 223.

If you have never heard of these things. “Fascinating Legend Revived in Massenet’s Coming Opera,” New York Times, August 16, 1908.

The Musician of Women

he grasped the need to maximize their appeal. Finck, Massenet and His Operas, 64.

a woman’s composer. The French phrases are “compositeur de la femme” and “musicien de la femme.” Fairly or not, he has been considered a “musician of femininity.” See Ghristi and Auclair, La belle époque de Massenet, 160. A contemporary referred to him as “the musician of woman and of love”; see Louis Schneider, Massenet: L’homme–le musicien (Paris: L. Carteret, 1908), 2 (“le musicien de la femme et de l’amour”); compare 382–83, where Schneider points to Massenet’s allegedly universal appeal to women as the basis for his current and future fame. Compare Finck, Massenet and His Operas, 64: “That he has been a great admirer of women it is needless to say to anyone familiar with his operas, for women and love are the themes of most of them. And the women reciprocated.”

The sneering latent in such observations. George Cecil, “Impressions of Opera in France,” Musical Quarterly 7 (1921): 314–30, at 320: “The ‘high brows’ jeer at him as a feminist composer of sugary ditties intended for the delectation of sentimental men and women incapable of appreciating really well thought-out music.”

an effeminate voluptuary. Charles Lecocq (see Fig. n.4), who came in for a goodly share of high-handed criticism himself, curled his lip about Massenet in this regard to his fellow composer Saint-Saëns. Examining Le jongleur de Notre Dame and Massenet’s reactions to Mary Garden’s insistence on singing the part of Jean in this context could lead to interesting results: see Huebner, French Opera, 160–66 (“Massenet Emasculated”); for this quotation, 162: “It is well known Massenet is a sensualist and that he always takes care to make declarations of love to the public with his music.”

the French musician could not write a successful opera. “Angry at an American Prima Donna: Mary Garden Rouses the Ire of Paris because She Profanes a Sacred Opera by Assuming the Role of a Man in a Work Where Women Are Barred,” Morning Oregonian (Portland, OR), January 10, 1909, 8.

According to one critic. Carl Van Vechten, Interpreters, 2nd ed. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1920), 85.

an unsparing caricature. “Charvic,” La Silhouette, March 25, 1894. On caricatures of Massenet, see Clair Rowden, “Mémorialisation, commémoration et commercialisation: Massenet et la caricature,” in Massenet aujourd’hui: Héritage et postérité. Actes du colloque de la XIe biennale Massenet des 25 et 26 octobre 2012, ed. Jean-Christophe Branger and Vincent Giroud, Centre interdisciplinaire d’études et de recherches sur l’expression contemporaine: Travaux, vol. 166/Collection musique et musicology: Les cahiers de l’Opéra théâtre, vol. 1 (Saint-Étienne, France: Publications de l’université de Saint-Étienne, 2014), 39–63.

he reminded himself. Massenet, My Recollections, 232.

Feminist theology. Elizabeth A. Johnson, “The Marian Tradition and the Reality of Women,” Horizons 12 (1985): 116–35.

The All-Male Cast

What, I exclaimed to myself. Massenet, Mes souvenirs, 240 (and see Condé’s n. 2, on La Terre promise).

a cast made up entirely of men. On this phenomenon generally, see Vincent Giroud, “Couvents et monastères dans le théâtre lyrique français sous la Troisième République,” in Branger and Ramaut, Opéra et religion sous la IIIe République, 37–64, at 59–64.

the Belgian symbolist poet Émile Verhaeren. With a libretto by Verhaeren and music by a French Jewish composer named Michel-Maurice Lévy. Written in 1899, the piece of theater was staged and published in 1900, first in Brussels and slightly later in Paris. After a delay of a decade and a half, the work was also made into an opera that was performed in the 1914–1915 season.

the English translation. The translation is The Cloister: A Play in Four Acts, trans. Osman Edwards (London: Constable, 1915). The review, by Arthur Davison Ficke, is in a piece entitled “Two Belgian Poets,” Poetry 8 (1916): 96–103, at 102.

the list of characters. It includes the jongleur Jean, singing tenor; Brother Boniface, bass; the prior, bass; the monk-poet, tenor; the monk-painter, baritone; the monk-musician, baritone; the monk-sculptor, bass; and, to move from the soloists, a crowd, merchants, and monks.

the dearth of space for sopranos. Edward Lockspeiser, “Broadcast Music,” Musical Times 100.1396 (June 1959): 330 (“there is a sameness of tone-color in the voices which soon begins to pall”).

As a journalist posed the question. L’Illustration, no. 3194, May 14, 1904, 336.

An etching. Done by Charles Baude, after a canvas by Albert Aublet. The original painting, entitled Autour d’une partition (Gathering around a score), was shown at the 1888 Salon.

a sumptuous drawing room. The house belonged to Pierre Loti (see Fig. n.5). Coincidentally, this French novelist and naval officer was, at least sporadically, a medievalizer. He once hosted a costumed dinner party that was staged in a notional 1470: see Elizabeth Emery, “Pierre Loti’s ‘Memories’ of the Middle Ages: Feasting on the Gothic in 1888,” in Memory and Commemoration in Medieval Culture, ed. Elma Brenner et al. (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2013), 279–97.

Sibyl Sanderson. On Sanderson, the best starting point is Jack Winsor Hansen, The Sibyl Sanderson Story: Requiem for a Diva, Opera Biography Series, vol. 16 (Pompton Plains, NJ: Amadeus Press, 2005).

its anachronism. On the anachronism, see Claudio Galderisi, “Le jongleur dans l’étui: Horizon chrétien et réécritures romanesques,” Cahiers de civilisation médiévale 54 (2011): 73–82.

Fig. n.4 Caricature of Charles Lecocq. Illustration by Aroun-al-Rascid [Umberto Brunelleschi], 1902. Published in L’Assiette au beurre (September 1902).

Fig. n.5 Pierre Loti. Photograph by George Grantham Bain, late nineteenth century. Washington, DC, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, George Grantham Bain Collection.

Notes to Chapter 2

I don’t want realism. Blanche DuBois, in Tennessee Williams, A Streetcar Named Desire, scene 9 (New York: Signet, 1951), 117.

Mary Garden Takes America

It is hardly too much to say. Musical America, January 25, 1908.

Later the soprano came to be known in America. See Charles Ludwig Wagner, Seeing Stars (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1940), 203; John Pennino, “Mary Garden and the American Press,” The Opera Quarterly 6.4 (1989): 61–75, at 61 and 62.

in the right spirit of picturesque feeling and romance. Hermann Klein, “The London Opera House,” Musical Times, 53.828 (February 1, 1912): 95–96, at 96: “What if the part of the Boy-Juggler was originally written for a tenor? By afterwards giving it to Mary Garden and altering it to suit her, the composer not only exercised a discretion to which he was entitled, but imparted to his opera, as I can personally testify, a measure of variety and interest that helped largely to enhance its popularity. The Chicago singer achieved what was required, because she approached her task in the right spirit of picturesque feeling and romance.”

His article. Morning Oregonian (Portland, OR) 28.2, January 10, 1909, 8.

her “Eiffel Tower.” Along the same lines, music critics of the day referred to the vocal height Sanderson achieved in this opera as the “Eiffel note of the Opéra Comique”: see Fauser, Jules Massenet, Esclarmonde, vi.

established singer. Marthe Rioton.

constructed his opera obsessively. The playwright had been assured, wrongly, that the opera would star his mistress and not Mary Garden.

redolent of medieval legends and romances. Michael T. R. B. Turnbull, Mary Garden (Portland, OR: Amadeus Press, 1997), 58. For broader context, see Paul Gorceix, “Maurice Maeterlinck, la mystique médiévale et le symbole,” La Licorne 6.1 (1982): 51–64; Carole J. Lambert, The Empty Cross: Medieval Hopes, Modern Futility in the Theater of Maurice Maeterlinck, Paul Claudel, August Strindberg, and George Kaiser (New York: Garland, 1990), 20–101; Arnaud Rykner, “Le drame symboliste,” in La fabrique du Moyen Âge au XIXe siècle: Représentations du Moyen Âge dans la culture et la littérature françaises du XIXe siècle, ed. Simone Bernard-Griffiths et al., Romantisme et modernités, vol. 94 (Paris: Honoré Champion, 2006), 1061–68.

as in a painting by Hans Memling. Gösta Mauritz Bergman, Lighting in the Theatre (Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1977), 315. The early Netherlandish artist, German by birth, was on many minds. Later, the singer Yvette Guilbert, in the phase of her career when she performed a medieval repertoire, was compared with him. See Bettina Liebowitz Knapp and Myra Chipman, That Was Yvette: The Biography of Yvette Guilbert, the Great Diseuse (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1964), 263: “She inherits the grace of the ‘Primitive’ painters, she sings as Van Eyck and Memling painted, with the careful and experienced preoccupation for drawing and construction that every great work and every great artist must possess.”

my Mélisande. Vincent Sheean, The Amazing Oscar Hammerstein: The Life and Exploits of an Impresario (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1956), 203.

Oscar Hammerstein I

In the annals of music in America. Finck, Massenet and His Operas, 13.

The delivery that these singers cultivated. They combined the agile leaps of coloratura singing, in which the soprano ornamented the vocal melody elaborately, with nearly glaciated stances of body. See Turnbull, Mary Garden, 59.

proliferation of performances. To take Christmas Day of 1909 as an example, Hammerstein’s Manhattan Opera presented in New York Tales of Hoffmann and Tosca, in Philadelphia Aïda and Faust, in Montreal Le Caïd and Mignon, and in Pittsburgh Cavalleria Rusticana, Pagliacci, and, last but not least, Le jongleur de Notre Dame.

the critical acclaim they achieved. Finck, Massenet and His Operas, 15.

as a singing actor. Susan Rutherford, The Prima Donna and Opera (1815–1930) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 231–76.

made her vulnerable to quibbling. See Evening Tribune, San Diego, California, July 15, 1922, 14, and San Diego Weekly Union, July 20, 1922, 8.

Making a Travesti of Massenet’s Tenor

women remained attached to them. Stéphane Michaud, Muse et madone: Visages de la femme de la Révolution française aux apparitions de Lourdes (Paris: Seuil, 1985), 23.

costumed as a male. This stratagem, in which a soprano sings the tenor part, goes in English by the name of a “trousers-role” or “breeches-part.” In demanding this major adjustment, the impresario reportedly acted on the advice of Maurice Renaud, the French baritone who had played Boniface in Monte Carlo. His approach to performing opera aligned well with Mary Garden’s: he was famed as much for his dramatic panache as for his vocal prowess.

the actor in question would be disguised. Mary Garden and Louis Biancolli, Mary Garden’s Story (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1951), 131, 139. This autobiography, not quite ghostwritten but often ghastly in its writing, exceeds Massenet’s in its unreliability. Elsewhere, she claimed to be the only woman singer to have secured Massenet’s permission to sing as the jongleur: see Turnbull, Mary Garden, 86. It is not known whether or not another French baritone, Lucien Fugère, with whom she had studied in Paris and who had scored a great success as Brother Boniface, had any role in the negotiations.

the boyish figure she prided herself on maintaining. Garden and Biancolli, Mary Garden’s Story, 132; Gillian Opstad, Debussy’s Mélisande: The Lives of Georgette Leblanc, Mary Garden, and Maggie Teyte (Woodbridge, UK: Boydell & Brewer, 2009), 248.

Garden had won great kudos. Opstad, Debussy’s Mélisande, 122.

putting her histrionic talent to a new test. This sentence paraphrases William S. Niederkorn, “Massenet’s ‘Jongleur’ Has Its U.S. Premiere,” New York Times, November 28, 1908.

A substantial article appeared. “Fascinating Legend Revived in Massenet’s Coming Opera,” New York Times, August 16, 1908: “When performed in Europe, the role has always been entrusted to a tenor, which makes the American production a novelty, even from the Continental standpoint.”

their own mixed feelings. Gary Waller, The Virgin Mary in Late Medieval and Early Modern English Literature and Popular Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 11 and passim.

Tongue-dragging. Michael P. Carroll, Madonnas That Maim: Popular Catholicism in Italy since the Fifteenth Century (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), 129–37 and 155–61 on masochism, 133–35 on tongue-dragging. The description in this book lacks either photographic or documentary support, and even the Italian term or terms used for the activity are not provided. Yet the practice is attested here and there, most notably in the dialect dictionary of Manlio Cortelazzo and Carla Marcato, I dialetti italiani: Dizionario etimologico (Turin, Italy: UTET, 1998), 419 (on the noun strascìnë which is attested amply in the Lucano dialect of Basilicata); Andrea Mancusi, La matréia (la matrigna): Saggio sul dialetto di Avigliano (Avigliano, Italy: Galasso, 1982), 116 (on the noun strascíne).

Freudian explanations. Michael P. Carroll, The Cult of the Virgin Mary: Psychological Origins (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986).

The supremely famous Sarah Bernhardt. Sheean, Amazing Oscar Hammerstein, 208. For the general topic, see Corinne E. Blackmer and Patricia Juliana Smith, eds., En Travesti: Women, Gender Subversion, Opera (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995).

the Sarah Bernhardt of opera. Turnbull, Mary Garden, 89.

Napoleon II of France. The play by Edmond Rostand was entitled L’aiglon, a nickname of the young emperor. “The Eaglet” had its London premiere in 1901. See Peter G. Davis, “An American Singer,” Yale Review 85.4 (1997): 1–19, at 14.

in a scrapbook. Opstad, Debussy’s Mélisande, 78.

Garden also claimed to have traveled with Debussy. Opstad, Debussy’s Mélisande, 119–20.

it was staged at the Odéon. Elizabeth Silverthorne, Sarah Bernhardt (Philadelphia, PA: Chelsea House, 2003), 49–50.

Zanetto’s Serenade. In French, Serénade de Zanetto. Another French composer, Émile Paladilhe, who had won the prestigious French Rome prize three years before Massenet, failed miserably with an opera that hewed to Coppée’s text.

made subsequently into operas. The first was The Lady of the Camelias (La dame aux camélias), originally an 1848 novel by Alexandre Dumas fils, adapted for the stage in 1852 and put to music by Giuseppe Verdi in La Traviata in 1853. The second was La Tosca, meaning “the Tuscan woman,” first an 1867 play by the French playwright Victorien Sardou and later an opera by the Italian composer Giacomo Puccini. See Opstad, Debussy’s Mélisande, 31.

the French actor had thought twice about playing the role. Sheean, Amazing Oscar Hammerstein, 268. On the scandal, see Theodore Ziolkowski, Scandal on Stage: European Theater as Moral Trial (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 59–73.

The theatrical work was published. Wilde came to hold a place of reverence within Garden’s pantheon of artistic influences. According to the American Margaret Caroline Anderson, she and her partner Jane Heap (see Fig. n.6) were struck when meeting the singer to discover that she had a large photograph of the Irish writer on display on her piano. See Margaret C. Anderson, My Thirty Years’ War: An Autobiography (New York: Covici, Friede, 1930), 137–38. Anderson founded, edited, and published the cultural magazine The Little Review (1914–1929). On The Little Review: Literature, Drama, Music, Art, see David Miller and Richard Price, British Poetry Magazines, 1914–2000: A History and Bibliography of “Little Magazines” (London: British Library, 2006), 29, item A 112.

London Opera House. The house was renamed the Stoll Theatre after being bought by the theater manager Oswald Stoll in 1916.

showcased Le jongleur de Notre Dame. For this season, Hammerstein had produced a libretto, Jules Massenet, Our Lady’s Juggler: Miracle in Three Acts, libretto by Maurice Léna, trans. Louise Baum (Paris: Au Ménestrel, Heugel, 1911). The principal role was sung by Victoria Fer. The French soprano had been dubbed by Massenet “the goddess of Nice,” after the city in southern France. She also substituted for Mary Garden in this capacity at the Manhattan Opera House. See Klein, “London Opera House,” 96.

the gross receipts had been eye-popping. Musical Times 53.829 (March 1, 1912): 192: “The season lasted ten weeks, and was the most successful ever given in Chicago. The gross receipts amounted to $463,000, or $63,000 more than last year. Among the operas performed, the following have obtained the most conspicuous success: ‘The Juggler of Nôtre [sic] Dame’ (Massenet), ‘The Jewels of the Madonna,’ ‘The Secret of Susanne’ (Wolf-Ferrari), and ‘Natoma,’ the new American-Indian opera by Victor Herbert.”

starting up. The company was built to no small extent on the set, costumes, copyrights, scores, and artists that the Metropolitan Opera had acquired by buying out Oscar Hammerstein’s Manhattan Opera House.

The Jewels of the Madonna. The original Italian was I gioielli della Madonna, known also in German as Der Schmuck der Madonna (not to be translated as “the Madonna’s schmuck”), a tragic opera in three acts by the Italian composer Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari, by the librettists Carlo Zangarini and Enrico Golisciani. The opera premiered in 1911 at the Kurfürstenoper (Electoral Opera House) in Berlin.

the dazzling artist. Massenet, My Recollections, 237.

clothing from the Rue de la Paix. See Massenet, My Recollections, 237; for the second quotation, 237–38: “My feelings are somewhat bewildered, I confess, at seeing the monk discard his frock after the performance and resume an elegant costume from the Rue de la Paix. However, in the face of the artist’s triumph I bow and applaud.”

famous for women’s jewelry and haute couture. For instance, the American novelist Edith Wharton referred to it in The Age of Innocence as allowing for “artistic” choices of merchandise, and she mentioned well-to-do New Yorkers to whom “Fifth Avenue is Heaven with the rue de la Paix thrown in.” The Age of Innocence, book 1, chap. 10, and book 2, chap. 33, in Edith Wharton, Novels, Library of America, vol. 30 (New York: Library of America, 1985), 1082, 1279.

the diva would endorse cosmetic products. The upper left of an advertisement from 1920 displays her in stylish dress as she applies either rouge or face powder; the upper right has large lettering that proclaims “Rigaud, 16 Rue de la Paix, Paris.”

a journalist reviewing her performance. “‘The Juggler,’ with Novelty,” New York Times, Thursday, January 11, 1912.

At least one other music critic. Henry Edward Krehbiel, More Chapters of Opera, Being Historical and Critical Observations and Records concerning the Lyric Drama in New York from 1908 to 1918 (New York: H. Holt, 1919), 99.

there is no such thing as bad publicity. The aphorisms provide an English correlative to the French concept of succès de scandale, literally “success from scandal” or “scandal success.”

We must wonder. Sheean, Amazing Oscar Hammerstein, 288.

one of those passive musicians. Quoted in Edward Wagenknecht, Seven Daughters of the Theater: Jenny Lind, Sarah Bernhardt, Ellen Terry, Julia Marlowe, Isadora Duncan, Mary Garden, Marilyn Monroe (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1964), 165. See also Garden and Biancolli, Mary Garden’s Story, 138.

helping to establish and propagate a new music. Quoted in Wagenknecht, Seven Daughters, 165: “Today we see the beginning of the great modern school, the music which deals with and carries to the hearts of its audiences great human truths. This modern music aims not wholly at the senses, but also at the mind. It does not aim merely at producing a vehicle for the production of glorious tones. It goes deeper than tone. It strives for a musical interpretation of the impulses and motives of the human mind and heart and soul. It represents not persons, but passions.”

the American première of Massenet’s Thaïs. On November 25, 1907. It had been performed first in 1894 and revised in 1898, with a libretto by Louis Gallet.

The dress stuck to my flesh. Garden and Biancolli, Mary Garden’s Story, 113; Turnbull, Mary Garden, 57.

James Gibbons Huneker. Arnold T. Schwab, James Gibbons Huneker: Critic of the Seven Arts (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1963), 257.

she had studied ballet daily. Musical America, Special Fall Issue (October 10, 1908): 28: “I take a dancing lesson each day, and think it will be very amusing to become a ballerine!” Garden here uses the French word for ballerina.

nearly transparent flesh-colored silk. Turnbull, Mary Garden, 57.

New York may insist on a few more clothes. On both the transparent silk and the different mores of New York, see “MARY GARDEN MAKES A THRILLING SALOME; Her Costume for Dance of Seven Veils—It Is Impossible to Describe It Even in Paris. RINGS ON LITTLE FINGERS A Red Wig, Too—Times Correspondent Sees Rehearsal Before She Sails—Comes on the Adriatic,” New York Times, October 25, 1908.

The resulting tempest in a teapot. June Sawyers, “The Night that ‘Salomé’ Shocked the Whole Town,” Chicago Tribune, “Lifestyles,” and The Milwaukee Journal, October 26, 1944. For the night itself, see New York Times, November 30, 1910.

Clothes are only shams. Turnbull, Mary Garden, 67.

Salomania. Udo Kultermann, “The ‘Dance of the Seven Veils’: Salome and Erotic Culture around 1900,” Artibus et Historiae 27.53 (2006): 187–215.

They bruited abroad. Ronald L. Davis, Opera in Chicago (New York: Appleton-Century, Affiliate of Meredith Press, 1966), 98.

Selling the Jongleur

Garden would grow irate. “Miss Garden Muses on Woman’s Perils,” New York Times, January 16, 1910, 16.

her manipulation of the media circus. On her handling of the media, see Pennino, “Mary Garden and the American Press.”

never was an active publicity hound. Wagner, Seeing Stars, 208–9, 211.

a scent that was marketed under her name. John Dos Passos, Manhattan Transfer 2.2, “Longlegged Jack of the Isthmus,” in idem, Novels, 1920–1925, Library of America, vol. 142 (New York: Library of America, 2003), 608. The perfume was produced by the parfumier Rigaud. An advertisement in the December 1917 issue of Ladies’ Home Journal spotlights her face and hair, while to the right is a partially draped French flag. Underneath are arrayed more than a dozen different cosmetics in the line.

miracle perfume. In French, a parfum miracle.

one exquisite odour. Thankfully, the copywriter resisted referring to the odor of sanctity. That would have stunk.

would open soon in America. The libretto followed was Le jongleur de Notre Dame (The Juggler of Notre Dame): Miracle Play in Three Acts, trans. Byrne, published in 1907.

the same issue of the daily. New York Times, August 16, 1908, p. SM8 (for Le jongleur de Notre Dame) and 7 (for “Isadora Duncan Arrives”).

New Woman. Viv Gardner and Susan Rutherford, eds., The New Woman and Her Sisters: Feminism and the Theatre (1850–1914) (London: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1992).

where are the snows of yesteryear?. This topos is often designated ubi sunt, to convey concisely the question “Where are… today?”

Duncan Grant. A British artist, he was a member of the Bloomsbury Group of artists, writers, and intellectuals.

and me too? Hugh McDiarmid, “A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle,” lines 30–32, in idem, Complete Poems, 2 vols. (Manchester, UK: Carcanet, 1993–1994), 1: 83–168, at 84.

Yvette Guilbert. Elizabeth Emery and Laura Morowitz, Consuming the Past: The Medieval Revival in fin-de-siècle France (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2003), 214–15. For a study of Guilbert’s life, see Knapp and Chipman, That Was Yvette.

Garden knew and studied her. James Huneker, Bedouins: Mary Garden, Debussy, Chopin or the Circus, Botticelli, Poe, Brahmsody, Anatole France, Mirbeau, Caruso on Wheels, Calico Cats, The Artistic Temperament; Idols and Ambergris; with The Supreme Sin, Grindstones, A Masque of Music, and The Vision Malefic (New York: Scribner, 1920), 10, 17; Garden and Biancolli, Mary Garden’s Story, 105, 145, 268.

diseuse. The technical term for a female monologuist.

café-concert singer. During this phase, she was a favorite subject in the art of the French artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Society for the Oldest French Texts. In French, Société des Anciens Textes Français.

founded in Paris in 1875. Knapp and Chipman, That Was Yvette, introduction (unnumbered page).

cathedral of Reims. Knapp and Chipman, That Was Yvette, 258.

sensational concerts. Knapp and Chipman, That Was Yvette, 279.

miracle of the Virgin. Knapp and Chipman, That Was Yvette, 280.

tours in Europe and America. See Elizabeth Emery, “From Cabaret to Lecture Hall: Medieval Song as Cultural Memory in the Performances of Yvette Guilbert,” in Memory and Medievalism, ed. Karl Fugelso, Studies in Medievalism, vol. 15 (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2007), 3–25; Elizabeth Emery, “‘Resuscitating’ Medieval Literature in New York and Paris: La Femme que Nostre-Dame garda d’estre arse at Yvette Guilbert’s School of Theatre, 1919–1924,” in Cultural Performances in Medieval France, ed. Eglal Doss-Quinby et al. (Rochester, NY: Boydell and Brewer, 2007), 265–78.

the jongleur also had another Mary to thank. We have recordings of this Mary’s voice as she sang the role of Jean on March 21, 1911 in New York: Columbia, 30699, 12-inch. Other cylinders and disks conserve the sounds as she crooned in 1903 in London and, to the accompaniment of Debussy’s piano playing, in 1904 in Paris. From far past her prime we have a record made in Camden, New Jersey in 1926. On 1912, see Opstad, Debussy’s Mélisande, 243; on 1903 and 1904, 118n34; on 1926, 259. In 1912, Mary Garden also sang at a dinner in Paris before a bevy of nobility and diplomats, including Mr. and Mrs. Robert Bliss—the eventual donors of the Harvard-owned institute in Washington that I presently direct: see “Entertainments in Paris: Kittens and Doves as Favors at Cotillion Given by Mrs. Moore” (special cable), New York Times, June 30, 1912, C5.

Mary Garden Dances the Role

Mary Garden’s time in Chicago. Although Chicago movie studios were important in the nascent film industry from 1907 through 1913, Garden’s involvement came after the rise of Hollywood. Without reference to her, see Michael Glover Smith and Adam Selzer, Flickering Empire: How Chicago Invented the U.S. Film Industry (New York: Wallflower Press, 2015).

gave her pride of place. In the Saturday Evening Post magazine of October 27, 1917.

one of the most colossal flops in movie history. Roger Butterfield, “Sam Goldwyn,” Life, October 27, 1947, 133.

To the majority of the audiences. In the April 5, 1918 issue of Variety magazine, quoted and cited by first Anne Morey, “Geraldine Farrar,” in Flickers of Desire: Movie Stars of the 1910s, ed. Jennifer M. Bean (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2011), 137–54, at 142, and then Mary Simonson, “Screening the Diva,” in The Arts of the Prima Donna in the Long Nineteenth Century, ed. Rachel Cowgill and Hilary Poriss (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 83–100, at 86.

remain legendary. In the standard biography of Mary Garden, the chapter on the year in which she premiered in Le jongleur de Notre Dame in New York at the end of November and later in Philadelphia is entitled “The Creation of a Legend: 1907–1908”: see Turnbull, Mary Garden, 55–65. For comments by those who saw her performances in the role of the jongleur, see pp. 88, 160, 171, 197.

to toy with taking the veil. On her dalliance with conversion, see Garden, Mary Garden’s Story, 133–34; Opstad, Debussy’s Mélisande, 198.

Mary Garden Avenue. In French, Rue Mary-Garden.

Place Mary-Garden. In English, Mary Garden Square. See Garden, Mary Garden’s Story, 135–37. Mary Garden’s contribution to the monument in Peille was honored in a small exposition that opened on Armistice Day, 2012.

January 24, 1931. For the date of Garden’s retirement, see Turnbull, Mary Garden, 173.

In her memoirs. Garden, Mary Garden’s Story, 247.

More than two decades passed. For her performances, see Davis, Opera in Chicago, 275–342.

the journalist described. Fred D. Pasley, Al Capone: Biography of a Self-Made Man (New York: Ives Washburn, 1930), 45: “This [a peculiar lurch in his walk, from a childhood injury] and his trick of canting his head as he talked produced on most visitors an impression of infinite slyness, reminiscent of Le Jongleur de Notre Dame.” The gangster compared with the juggler was Dion O’Banion.

The Role of Dance

a collector and historian of art and literature. Carola Giedion-Welcker, “Meetings with Joyce,” in Portraits of the Artist in Exile: Recollections of James Joyce by Europeans, ed. Willard Potts (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1979), 256–80. Giedion-Welcker also produced an In memoriam James Joyce (Zurich: Fretz & Wasmuth, 1941).

a professor of English literature. His name was Bernhard Fehr.

wild jumps and kicks. Giedion-Welcker, “Meetings with Joyce,” at 273–74. “These rhythmical and astonishingly acrobatic exercises” reduced his stiff straw hat to nothing more than a wreath.

part juggling clown. Giedion-Welcker, “Meetings with Joyce,” at 273–74: “The grotesque flexibility of his long legs, which seemed to fill the room, and the bizarre grace with which he executed all movements of this strange dance, made him appear part juggling clown and part mystical reincarnation of Our Lady’s Tumbler, who would like to have continued the performance endlessly, urged on by the constantly changing musical variations of the tireless piano player.” Nothing suggests that the Irishman had the comparison with the entertainer on his mind, and the raconteur makes the literary allusion decades after the evening in question.